1 Department of Cardiology, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, 200032 Shanghai, China

2 National Clinical Research Center for Interventional Medicine, 200032 Shanghai, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Background: In recent years, transcatheter aortic valve replacement

(TAVR) has emerged as a pivotal treatment for pure native aortic regurgitation

(PNAR). Given patients with severe aortic regurgitation (AR) are prone to suffer

from pulmonary hypertension (PH), understanding TAVR’s efficacy in this context

is crucial. This study aims to explore the short-term prognosis of TAVR in PNAR

patients with concurrent PH. Methods: Patients with PNAR undergoing TAVR

at Zhongshan Hospital, Affiliated with Fudan University, were enrolled between

June 2018 to June 2023. They were categorized based on pulmonary artery systolic

pressure (PASP) into groups with or without PH. The baseline characteristics,

imaging records, and follow-up data were collected. Results: Among the

103 patients recruited, 48 were afflicted with PH. In comparison to PNAR patients

without PH, the PH group exhibited higher rates of renal dysfunction (10.4% vs.

0.0%, p = 0.014), increased Society of Thoracic Surgeons scores (6.4

Keywords

- pure native aortic regurgitation

- transcatheter aortic valve replacement

- pulmonary artery hypertension

- retrospective

Pure native aortic regurgitation (PNAR) arises from intrinsic valve leaflet abnormalities, aortic root dilation, or geometric distortion, or a combination thereof, resulting in retrograde blood flow into the left ventricle during diastole. The prevalence of aortic regurgitation (AR) is positively correlated with age, as individuals over the age of 70 have a diagnosis rate exceeding 2% and face a poorer prognosis [1, 2, 3, 4]. While surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) is the preferred treatment for AR, the one-year mortality rate varies from 10% to 20% [5]. Additionally, SAVR may not be an option for patients of advanced age or those with compromised heart function.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is an important treatment option for severe aortic valve stenosis (AS) in individuals at high surgical risk, offering advantages including faster recovery and reduced trauma [5, 6]. Advances in TAVR have broadened its application to include lower-risk patients, thereby expanding the eligible patient base. However, its application to PNAR treatment remains limited, as the absence of valvular calcium presents significant challenges, including increased risks of valve embolization, migration, and para-valvular leak.

Nearly 20% of individuals with PNAR also experience pulmonary hypertension (PH), with 10%–16% facing severe conditions [7, 8], a prevalence surpassing that observed in individuals experiencing severe stenosis or aortic valve disease. This disparity arises from blood regurgitation into the left ventricle during diastole in cases of AR, increasing the pressure load to the left ventricle, eventually resulting in PH. While TAVR has proven effective for AS patients with PH [9, 10], its performance in PNAR patients with concomitant PH remains unknown. This gap in knowledge prompted our study, aiming to evaluate the safety and efficacy of TAVR for PNAR patients with PH.

For this study, we recruited patients diagnosed with PNAR and implanted with

VenusA-Valve (Venus Medtech, Hangzhou, China) or VitaFlow valve (Microport,

Shanghai, China) at Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, from June 2018 to June

2023. All patients were considered unsuitable for surgical valve replacement

after a comprehensive evaluation. In addition, all patients had a follow-up

duration of

The PH classification was as follows. Based on the pulmonary artery pressure

grading criteria from previous studies [11], patients were divided by the

presence of PH (pulmonary artery systolic pressure, PASP

All patients underwent TAVR via intravenous anesthesia by the structural heart disease surgery team in the Department of Cardiology, Zhongshan Hospital. Patients had a post operative follow-up visit at the outpatient department after 30 days and 6 months, with transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and electrocardiography (ECG) examinations performed, and perioperative endpoint events recorded. The definition of clinical outcomes followed the Valve Academic Research Consortium-3 (VARC-3) criteria [12]. The primary endpoints included all-cause death and cardiovascular death. The secondary endpoints included TAVR-related complications, such as myocardial infarction, major bleeding events, major vascular complications, acute kidney injury, stroke, endocarditis, new-onset atrial fibrillation, implantation of a new pacemaker, coronary artery obstruction, mild paravalvular leak, and rehospitalization.

Statistical analysis of the data was conducted using STATA (version 15.1;

Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean

In this study, 103 patients were enrolled, including 62 males and 41 females

with a mean age of (72.1

| Patient characteristics | Without PH Group (n = 55) | PH Group (n = 48) | p value | |

| Age, yrs | 72.9 |

71.2 |

0.28 | |

| Male | 31 (56.4%) | 31 (64.6%) | 0.40 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.1 |

22.6 |

0.33 | |

| Hyperlipidemia, % | 21 (38.2%) | 14 (29.2%) | 0.34 | |

| Hypertension, % | 40 (72.7%) | 33 (68.8%) | 0.66 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 3 (5.5%) | 4 (8.3%) | 0.56 | |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 11 (20.0%) | 13 (27.1%) | 0.40 | |

| Coronary artery disease, % | 10 (18.2%) | 10 (20.8%) | 0.73 | |

| Previous PCI, % | 8 (14.5%) | 6 (12.5%) | 0.79 | |

| COPD, % | 8 (14.5%) | 5 (10.4%) | 0.53 | |

| PPM, % | 2 (3.6%) | 4 (8.3%) | 0.31 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease, % | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.28 | |

| Renal insufficiency, % | 0 (0%) | 5 (10.4%) | 0.014 | |

| Symptom, % | 21 (38.2%) | 26 (54.2%) | 0.10 | |

| Left bundle branch block, % | 4 (7.3%) | 2 (4.2%) | 0.50 | |

| Right bundle branch block, % | 3 (5.5%) | 2 (4.2%) | 0.76 | |

| Atrioventricular block, % | 12 (21.8%) | 5 (10.4%) | 0.12 | |

| NYHA functional class III or IV, % | 42 (76.4%) | 45 (93.8%) | 0.015 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 82.4 |

122.2 |

0.012 | |

| NT-proBNP (ng/pL) | 1050.4 |

2542.1 |

||

| STS risk score | 4.7 |

6.4 |

||

Abbreviations: PNAR, pure native aortic regurgitation; PH, pulmonary hypertension; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPM, permanent pacemaker; NYHA, New York Heart Association; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeon; NT-proBNP, N-terminal fragment of pro–brain natriuretic peptide.

TTE examination further differentiated the two

groups. Patients with PH group exhibited significantly higher PASP (44.3

| Without PH Group (n = 55) | PH Group (n = 48) | p value | ||

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 56.7 |

51.9 |

0.030 | |

| LVEDd (mm) | 55.2 |

61.3 |

||

| LVEDs (mm) | 38.4 |

45.7 |

||

| LVPWd (mm) | 10.0 |

10.8 |

0.005 | |

| IVS (mm) | 10.9 |

11.0 |

0.71 | |

| Severe aortic regurgitation, % | 55 (100%) | 48 (100.0%) | - | |

| Aortic valve peak velocity (m/s) | 1.9 |

2.0 |

0.69 | |

| Mean valve gradient (mmHg) | 9.0 |

9.0 |

0.99 | |

| Effective orifice area (cm2) | 2.8 |

2.7 |

0.59 | |

| Moderate to severe MR | 13 (23.6%) | 16 (33.3%) | 0.28 | |

| Moderate to severe TR | 11 (20.0%) | 18 (37.5%) | 0.049 | |

| PASP, mmHg | 30.7 |

44.3 |

||

| Computed tomography | ||||

| Aortic annulus area (mm2) | 505.7 |

533.1 |

0.064 | |

| Aortic annulus perimeter (mm) | 83.3 |

84.2 |

0.46 | |

| Largest diameter of ascending aorta (mm) | 34.6 |

36.3 |

0.050 | |

Abbreviations: LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVEDd, left ventricle end-dimension diastole; LVEDs, left ventricle end-dimension systole; LVPWd, left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-diastole; IVS, interventricular septal thickness; MR, mitral regurgitation; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; PNAR, pure native aortic regurgitation; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure.

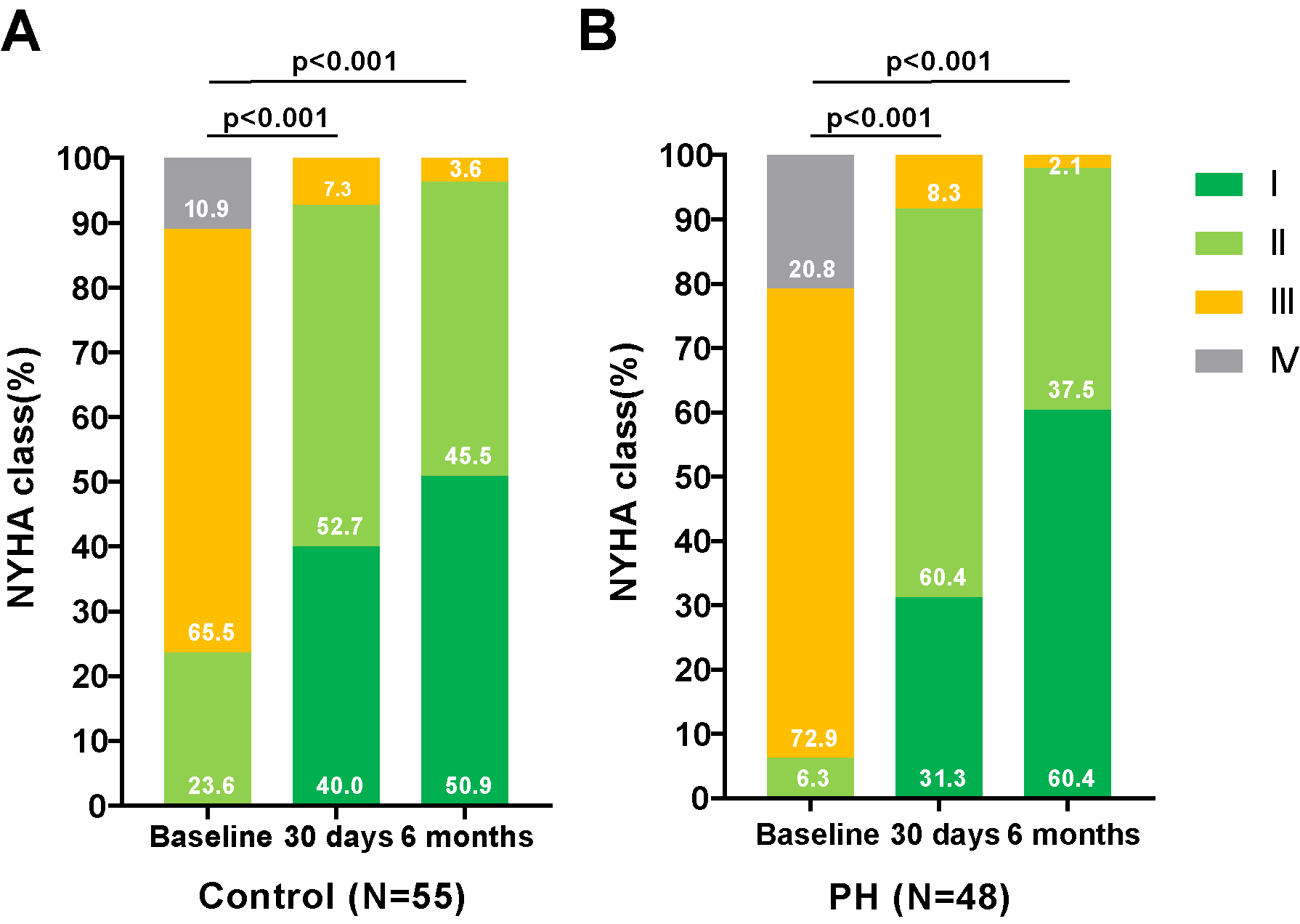

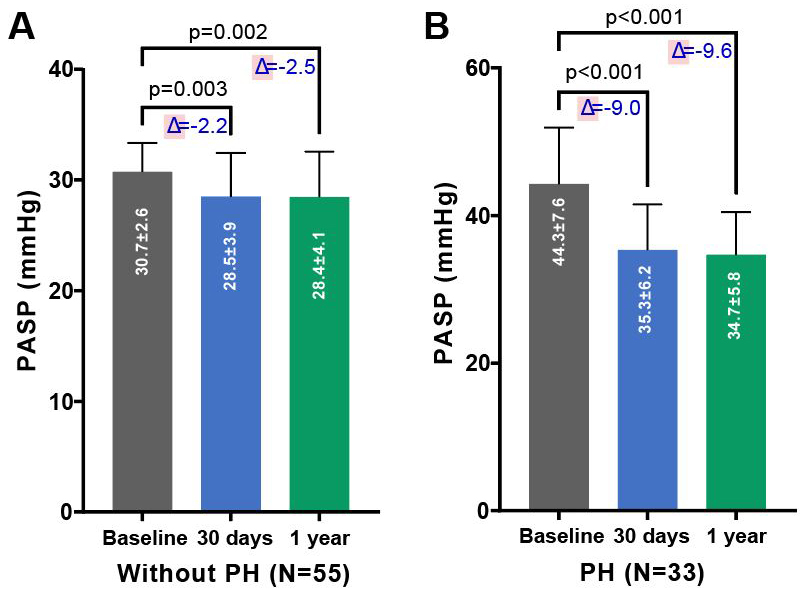

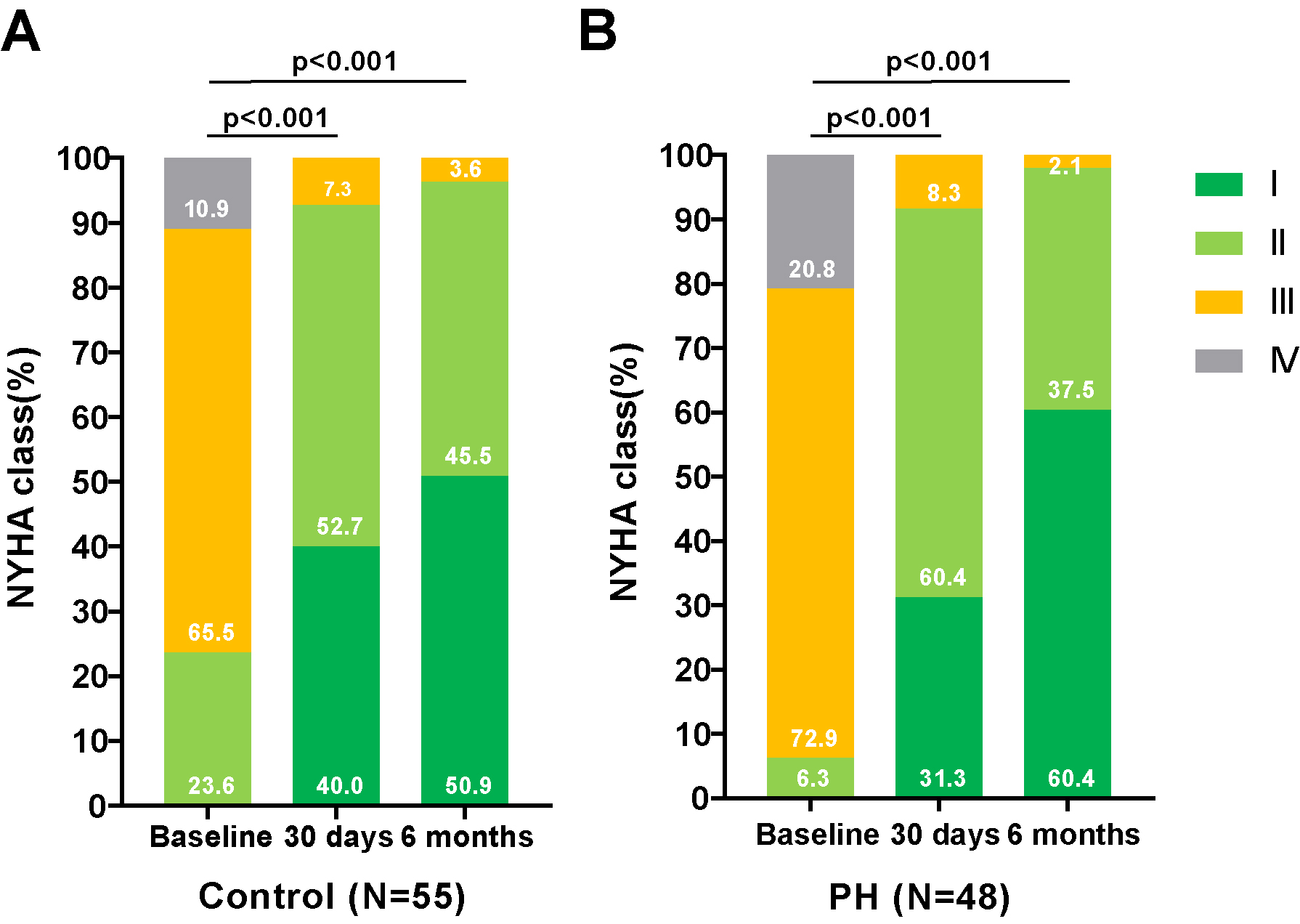

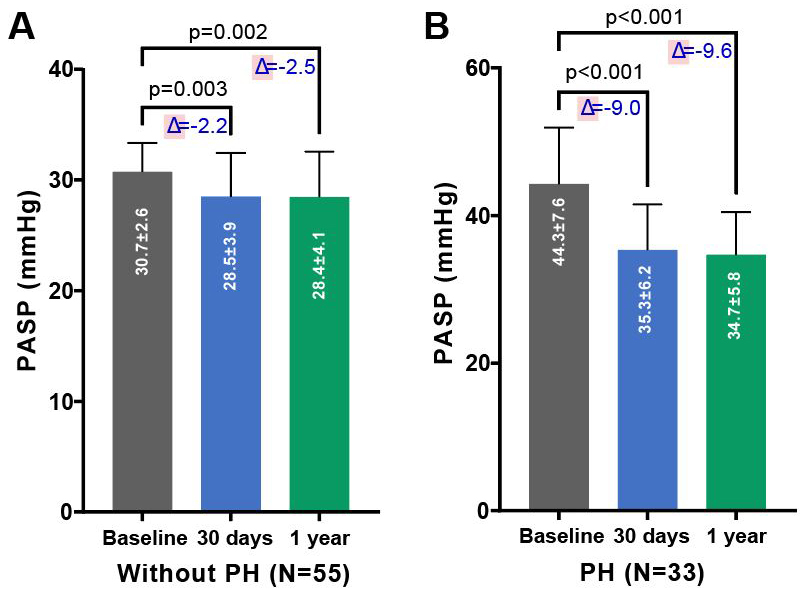

As depicted in Figs. 1,2, there was a significant improvement in

cardiac function observed in both groups—those with and without PH—at 30 days

and 6 months post-TAVR, compared to baseline measurements. This improvement was

accompanied by a notable reduction in PASP. As shown in Table 3, compared to

baseline, patients with PH demonstrated a significant decrease in PASP (35.3

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Changes in the NYHA functional classification in PNAR patients Pre- and Post-TAVR, with and without PH. Assessment of the NYHA functional class changes in patients with PNAR undergoing TAVR, categorized by the presence or absence of PH. (A) illustrates the progression in patients without PH, while (B) details those with PH. These comparisons highlight the procedural impact on cardiac functional status over the follow-up period. Abbreviations: PH, pulmonary artery hypertension; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PNAR, pure native aortic regurgitation.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Changes in PASP pre- and post-TAVR in PNAR patients, segregated by PH status. Comparison of PASP before and after TAVR in patients with PNAR, differentiated by the absence (A) or presence (B) of PH. The figure underscores the procedural impact on PASP across both patient categories over the follow-up period, demonstrating the effectiveness of TAVR in modifying hemodynamic parameters. Abbreviations: PH, pulmonary artery hypertension; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; PASP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure; PNAR, pure native aortic regurgitation.

| Echocardiography | Without PH Group (n = 55) | ||||

| Baseline | 30 days | p1 value | 6 months | p2 value | |

| LVEF (%) | 56.7 |

55.2 |

0.42 | 56.4 |

0.94 |

| PASP, mmHg | 30.7 |

28.5 |

28.4 |

0.002 | |

| Moderate to severe MR, % | 13 (23.6%) | 3 (5.5%) | 3 (5.5%) | ||

| Average grade of MR | 1.7 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

||

| Moderate to severe TR, % | 11 (20.0%) | 6 (10.9%) | 0.11 | 2 (3.6%) | 0.014 |

| Average grade of TR | 1.4 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

||

| Moderate to severe AR, % | 55 (100.0%) | 2 (3.6%) | 1 (1.8%) | ||

| Echocardiography | PH Group (n = 48) | ||||

| Baseline | 30 days | p1 value | 6 months | p2 value | |

| LVEF (%) | 51.9 |

50.8 |

0.65 | 52.5 |

0.78 |

| PASP, mmHg | 44.3 |

35.3 |

34.7 |

||

| Moderate to severe MR, % | 16 (33.3%) | 6 (12.5%) | 0.015 | 4 (8.3%) | 0.003 |

| Average grade of MR | 1.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

||

| Moderate to severe TR, % | 18 (37.5%) | 7 (14.6%) | 0.011 | 4 (8.3%) | 0.003 |

| Average grade of TR | 2.02 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

||

| Moderate to severe AR, % | 48 (100.0%) | 1 (2.1%) | 1 (2.1%) | ||

p1: the significance of characteristics in 30 days comparing to those in baseline. p2: the significance of characteristics in 6 months comparing to those in baseline. Abbreviations: PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MR, mitral regurgitation; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; AR, aortic regurgitation; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; PH, pulmonary hypertension.

There was no significant difference in primary and secondary endpoints in PNAR patients with or without PH who underwent TAVR. Notably, there were no instances of all-cause or cardiac death in either group. The incidence of major in-hospital adverse events was as follows: major bleeding, major vascular complications, stroke, and new-onset atrial fibrillation, new-onset left bundle branch block, new-onset atrioventricular block, permanent pacemaker implants, and mild paravalvular leaks were 2.1%, 0%, 2.1%, 2.1%, 12.5%, 27.1%, 29.2%, and 14.6% in the group with PH and 0%, 0%, 0%, 7.3%, 21.8%, 20.0%, 16.4%, and 5.5% in the group without PH.

During the 6 months follow-up period, hospital admissions were slightly higher in the PH group (3 patients) compared to the control group (1 patient). Additionally, the group with PH exhibited a prevalence of 2.1% for major bleeding events, 4.2% for strokes, 6.3% for permanent pacemaker implants and new-onset atrioventricular block, and 12.5% for mild paravalvular leaks. The group without PH demonstrated a prevalence of 1.8% for new-onset left bundle branch block, 10.9% for new-onset atrioventricular block, 3.6% for new permanent pacemaker implants and 9.1% for mild para-valvular leaks. This data is summarized in Table 4.

| Clinical end-points | In hospital | 6 months | |||||

| Without PH group (n = 55) | PH group (n = 48) | p | Without PH group (n = 55) | PH group (n = 48) | p | ||

| Primary endpoints | |||||||

| All-cause mortality, % | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | |

| Cardiovascular mortality, % | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | |

| Secondary endpoints | |||||||

| Bleeding event, % | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.29 | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.92 | |

| Major Vascular complication, % | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | |

| Acute renal failure, % | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | |

| Stroke, % | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.29 | 1 (1.8%) | 2 (4.2%) | 0.48 | |

| Myocardial infarction, % | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | |

| New AF, % | 4 (7.3%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.21 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | |

| New LBBB, % | 12 (21.8%) | 6 (12.5%) | 0.20 | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.35 | |

| New AVB, % | 11 (20.0%) | 13 (27.1%) | 0.42 | 6 (10.9%) | 3 (6.3%) | 0.40 | |

| New PPM, % | 9 (16.4%) | 14 (29.2%) | 0.13 | 2 (3.6%) | 3 (6.3%) | 0.54 | |

| Endocarditis, % | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | |

| Mild PVL, % | 3 (5.5%) | 7 (14.6%) | 0.12 | 5 (9.1%) | 6 (12.5%) | 0.58 | |

| Re-hospitalization, % | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | 1 (1.8%) | 3 (6.3%) | 0.25 | |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; LBBB, left bundle branch block; AVB, atrioventricular block; PPM, permanent pacemaker; PVL, perivalvular leakage; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; PH, pulmonary hypertension.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report the outcomes of TAVR in patients diagnosed with PNAR and PH. The findings indicate that TAVR is a safe option for this patient group, as evidenced by the absence of any significant disparities in all-cause mortality and cardiac mortality between the two groups during hospitalization and throughout a 6-month follow-up period. Moreover, TAVR proves to be an effective intervention for these patients, as it leads to a substantial reduction in AR severity and PASP, while significantly improving cardiac function.

Our study demonstrated a notable decrease in the incidence of AR and PASP in both groups following TAVR. In 6 months post-TAVR, a significant alleviation of AR was observed in 97.9% of the PNAR patients with PH, and in 98.2% of those without PH, indicating the effectiveness of TAVR in both cohorts. Additionally, patients diagnosed with PNAR exhibited a tendency towards higher PASP levels. Previous research has documented that approximately 20% of patients experience PH, with 10–16% classified as severe [7, 8]. This phenomenon is primarily due to increased left ventricular afterload induced by AR, which produces backward spread to left atrium and pulmonary veins. Initially, pulmonary vascular resistance is at normal stage, however chronically elevated left atrial pressure can lead to pulmonary vascular remodeling—a combination of precapillary and postcapillary PH [13, 14].

Furthermore, we found that the increasing PASP in PNAR can be down-regulated

after TAVR, meaning that pulmonary vascular remodeling is reversible to some

degree. We found a significant decline in the value of PASP in both groups after

TAVR, a reduction that was maintained through the 6-month follow-up period.

Notably, there was no significant difference in PASP levels between the 6-month

and 30-day follow-up. This supports the hypothesis that elevated PASP is a

contributing factor to AR severity. A related study by Naidoo DP, et al.

[14] involving 13 patients undergoing SAVR found that pulmonary vascular

resistance decreased from 4.7

Our study demonstrated that patients with PNAR and PH exhibit compromised cardiac function, characterized by reduced ejection fraction and larger ventricular volume compared to patients without PH. In patients with aortic and/or mitral valve disease, the diagnosis of PH suggests the exhaustion of the compensatory mechanism in the left heart. Additionally, our study noted a higher occurrence of moderate to severe TR among PNAR patients with PH, highlighting the detrimental effect of PH on right heart dynamics.

Encouragingly, following TAVR, the incidence of TR and MR decreased during the initial and 1-month follow-up periods. This outcome indicates that the cardiac remodeling caused by AR and PH can be reversed. Consequently, TAVR appears to be a viable option for patients with AR and also offers potential amelioration for associated MR/TR, providing a comprehensive treatment approach for patients suffering from these complex cardiac conditions.

Our findings affirm the safety of TAVR for patients with PNAR and PH. There were

no instances of all-cause death or cardiac mortality in either patient group

during hospitalization or within 6-months following the operation. Additionally,

through the follow-up, there were no significant differences between groups in

the incidence of stroke, permanent pacemaker implantation, mild perivalvular

leakage, bleeding events, vascular complications, and new atrial fibrillation

events. This contrasts with a large retrospective study in the United States of

915 patients with severe AR after TAVR, which reported a hospital mortality rate

of 2.7% and a 1-month post-operative mortality rate of 3.3% [15]. The

valve-related complications in this study were 18–19%, with perivalvular

leakage (4–7%) and complete atrioventricular block and/or require permanent

pacemaker implantation (about 11%) being most common [15]. While the long-term

prognosis of patients with severe AR and PH undergoing TAVR has yet to be

reported, a study conduct on SAVR in AR patients with PH suggests a higher

10-year survival rate than that in patients without valve replacement (p

Our study is subject to certain limitations that merit consideration. Firstly, it is a retrospective analysis conducted at a single-center, it features a relatively small cohort, and the follow-up period was limited to 6 months. Such constraints may affect the generalizability of the results and underscore the need for larger, multi-center, prospective studies with extended follow-up durations to validate our findings. Secondly, the assessment of PASP was performed using echocardiography, as opposed to right heart catheterization, which is regarded as the gold standard for this measurement. Consequently, the estimated PASP values may lack the precision achievable through catheterization, potentially affecting the accuracy of our PH evaluations. Additionally, patients with extremely severe PH were excluded from this study due to their ineligibility for TAVR based on our selection criteria. This exclusion limits our insights into the outcomes of TAVR in this particularly high-risk patient subgroup, indicating a gap in current research that future studies could aim to address.

This study demonstrated that TAVR is both safe and effective in treating PNAR complicated by PH. We observed significant improvements in AR and reductions in PASP following TAVR, with no significant differences in the rate of postoperative adverse events between the two groups. Consequently, TAVR has emerged as a viable treatment option for this patient population. Looking ahead, the establishment of multi-center randomized controlled trials and long-term follow-up studies are needed to comprehensively evaluate the long-term efficacy and benefits of TAVR in patients with severe AR and PH. Such research efforts will be vital in solidifying the role of TAVR within this therapeutic domain.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

WZP, DXZ and JBG were responsible for conception and design of the study. DWL, JNF and ZLW contributed substantially to data acquisition and data analysis. DWL, JNF, ZLW, LHG and YLL contributed to the writing, editing, formatting of the main manuscript, and production of the fgures. WZP, DXZ, LHG and YLL contributed to the supervision of the study and revising of the manuscript. All authors contributed substantially to critical revising of the manuscript, to the final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (number: B2020-039), and all patients were informed and signed a consent form.

Not applicable.

Shanghai Clinical Research Center for Interventional Medicine (No.19MC1910300).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.