1 School of Medicine, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. 20007, USA

2 School of Medicine and Health Sciences, George Washington University, Washington, D.C. 20037, USA

3 Department of Electrophysiology, MedStar Heart and Vascular Institute, Washington, D.C. 20010, USA

Abstract

The expanding field of cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) in individuals with and without atrial fibrillation (AF) presents a complex landscape, demanding careful interpretation of the existing research. AF, characterized by significant mortality and morbidity, prompts the exploration of strategies to mitigate its impact. Increasing physical activity (PA) levels emerges as a promising avenue to address AF risk factors, such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, through mechanisms of reduced vasoconstriction, endothelin-1 modulation, and improved insulin sensitivity. However, caution is warranted, as recent investigations suggest a heightened incidence of AF, particularly in athletes engaged in high-intensity exercise, due to the formation of ectopic foci and changes in cardiac anatomy. Accordingly, patients should adhere to guideline-recommended amounts of low-to-moderate PA to balance benefits and minimize adverse effects. When looking closer at the current evidence, gender-specific differences have been observed and challenged conventional understanding, with women demonstrating decreased AF risk even at extreme exercise levels. This phenomenon may be rooted in divergent hemodynamic and structural responses to exercise between men and women. Existing research is predominantly observational and limited to racially homogenous populations, which underscores the need for comprehensive studies encompassing diverse, non-White ethnic groups in athlete and non-athlete populations. These individuals exhibit a disproportionately high burden of AF risk factors that could be addressed through improved CRF. Despite the limitations, randomized control trials offer promising evidence for the efficacy of CRF interventions in patients with preexisting AF, showcasing improvements in clinically significant AF outcomes and patient quality of life. The potential of CRF as a countermeasure to the consequences of AF remains an area of great promise, urging future research to delve deeper to explore its role within specific racial and gender contexts. This comprehensive understanding will contribute to the development of tailored strategies for optimizing cardiovascular health and AF prevention in all those who are affected.

Keywords

- atrial fibrillation

- cardiorespiratory fitness

- race

- gender

- exercise

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, and its prevalence is increasing in the United States (US) and worldwide. In 2010, the US prevalence of AF was 5.2 million; by 2030, that number is expected to rise to 12.1 million [1]. AF is a condition with significant mortality and morbidity [2], and importantly, AF is often seen in conjunction with other known cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension (HTN), obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), and dyslipidemia. As such, modification of risk factors is one of the principal pillars of preexisting AF management in the most recently published 2023 American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) guidelines, which also highlights risk factor reduction as an important method for primary AF prevention [3]. In fact, mitigating these determinants can be especially effective in certain populations that face higher burden and increased severity of AF due to other underlying conditions [4]. One way to address this issue is by promoting lifestyle changes, one of the most powerful tools being exercise.

Improving cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) and physical activity (PA) are highly effective strategies in preventing AF [5]. AF is related to and often worsened by existing comorbidities, such as HTN, coronary artery disease (CAD), heart failure (HF), obesity, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [6]. As a result, the most effective treatments involve addressing and managing underlying disease. Early data suggests that implementation of this strategy shows AF symptom severity and mortality have decreased while quality of life has increased [7]. The CRF-AF association is an area that currently lacks randomized control trials (RCTs) and instead relies mostly on observational data. However, the limited research available is obscured by multivariate influences of exercise intensity, gender, race, and—in many cases—lack of objective data. Nevertheless, investigators have developed several hypotheses about these results to isolate and disentangle this multifactorial relationship between exercise and AF [8].

In this review, we provide an update on the impact of exercise on AF with a special focus on how these differences are stratified by race and gender. We will cover potential mechanisms behind these findings yet also comment on the available research’s limitations. Lastly, we will offer a brief overview of the role of modifying PA in the treatment of patients with preexisting AF.

We performed a narrative review investigating the role of CRF in AF, especially as it relates to race and gender. We conducted our search using the PubMed online database using relevant articles published after the year 1998 using keywords “cardiorespiratory fitness”, “atrial fibrillation”, “exercise”, “physical activity”, “race”, “gender”, and “pathophysiology”. A combination of these respective keywords with Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” was utilized, along with medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and their respective synonyms. Only articles written in English were included. The articles’ merit, limitations, applicability, and conclusions were evaluated by the authors for inclusion into this review.

The epidemiology of CRF and AF involves a complex interplay between various

factors, some of which being age, race, and gender. Current estimations show that

1 in 4 people are at risk of developing AF at some point in their life [8]. The

strongest risk factor for developing AF is increasing age. Increased AF incidence

with age is believed to result from cumulative exposure to longstanding,

subclinical inflammation from other diseases or environmental influences [9].

Similar to older populations, diagnosis of AF in individuals younger than 65

years is becoming more prevalent [3]. In these age groups, the most effective

method in combating AF incidence is through reducing common AF risk factors. One

approach to do so is performing regular mild to moderate PA of

Indeed, exercise has been shown to be a suitable intervention to improve AF clinical outcomes by reducing incident risk of related cardiovascular conditions in patients with AF [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. According to the latest Center for Disease Control estimates, over 38.4 million Americans suffer from DM, and 34.3% of Americans diagnosed with DM are considered physically inactive [17]. In their analysis of over 20 cohort studies, Warburton et al. [18] (2010) determined that 84% of participants exhibited a dose-response relationship with even minor positive changes in PA leading to significant reductions in DM incidence [19]. The prevalence of AF is over twice as likely in individuals with DM compared to those without DM [20]. Similarly, roughly 120 million Americans live with HTN [21] and, consequently, face a 1.8-fold higher likelihood of developing AF [22]. Individuals who partake in exercise training experience decreased systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and in some cases, a HTN diagnosis can even become reversible [23, 24]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the effect of decreased blood pressure following exercise is transient, thus emphasizing the importance for PA to be a regular practice [23]. Sedentary individuals with chronic HTN develop cardiovascular disease at a rate that is 2-fold greater than those without HTN [25]. Lastly, obesity follows a similar trajectory to the other mentioned AF risk factors. Over 140 million Americans are considered clinically obese [26], and with every additional point on the body mass index scale, the incidence of AF accordingly increases by 17% [27]. The Norwegian HUNT3 study reported that the relative risk of obese inactive individuals for developing AF was 1.96, whereas this ratio decreased to 1.53 for obese individuals who engaged in regular PA [28]. Each of these three comorbidities exhibit interconnected relationships and propagate each other’s progression, thus causing unfavorable outcomes in individuals with or at-risk for cardiovascular diseases such as AF [29]. Addressing one comorbidity with exercise may positively impact others and reduce future incidence of AF, especially in select groups who are most at risk for these risk factors and thus AF.

Evidence indicates that AF does not affect every population equally [8]. The lifetime risk is greater than 30% in White individuals, 20% in Black individuals, and 15% in Chinese individuals [30]. Despite White groups having the highest risk for AF, disease severity is far worse in diverse racial populations [31]. For example, while the prevalence of AF is significantly higher among White individuals, the mortality rate is higher in Black patients [32, 33]. One study cites a more accurate clinical process for diagnosing AF in the White populations as a potential explanation for this finding, as Black patients received diagnoses later in the course of AF progression as exacerbations led to severe symptoms [34]. In contrast, White patients were diagnosed at earlier stages, enabling them to be better prepared to mitigate the risk of experiencing severe symptoms. Interestingly, the disparity in early diagnosis was corrected with an ambulatory electrocardiogram device in this cohort, which potentially indicates a true prevalence for Black groups closer to their White counterparts [34]. Moreover, in those who have been successfully diagnosed with AF, Black patients also suffer stroke at a higher rate [34]. This elevated stroke risk holds true in Hispanic populations as well, as Hispanics to have a 2.46 times increased likelihood of stroke recurrence compared to non-Hispanic White patients [35]. Ultimately, the increased rates of stroke occurrence in the non-White populations can be combatted through a more homogenous system for diagnosing AF across all races.

Given the high prevalence of AF in the population, it is imperative to create solutions to prevent deaths and other complications. Certain racial groups may be at higher risk for greater disease burden and thus require increased attention for diagnosis and management. Patients with obesity, HTN, and DM are at elevated risk and particularly susceptible, and enhancing CRF may be an apt way to decrease AF incidence. Evidence in the last few decades has corroborated the utility of this lifestyle change of increasing physical activity, yet more questions arise when discussing the safest possible way of doing so.

Despite the obvious benefits of exercise on mortality and morbidity from

cardiovascular disease, recent evidence has provided mixed results for the

previously well-defined phenomenon that associates high-intensity PA and AF. This

‘exercise paradox’ was first reported over two decades ago with the observation

that found increased risk for AF in middle and older-aged veteran runners

compared to non-athlete controls [36]. Since this initial finding, large cohort

studies have established this interesting dynamic between high fitness levels and

the development of AF, especially in endurance-based exercise. Andersen

et al. [37] (2013) showed those athletes who completed the most

cross-country skiing races and had the fastest finishing times were more

susceptible to AF in the future, albeit only in younger cohorts. A follow-up

study in 208,654 Swedish skiers demonstrated a similarly powerful association of

exercise with AF incidence, yet these results were stratified by gender [38]. In

cyclists, increased AF diagnosis was observed in those athletes who had greater

heart structure remodeling; both endpoints were witnessed more frequently in

individuals with increasing cycling years compared to age-matched controls [39].

This suggests the effect of cumulative exercise years at older ages may increase

arrythmia risk, which was replicated in a later study [40]. Interestingly, former

strength-trained athletes in the National Football League (NFL) exhibited higher

rates of AF than age and race-matched controls [41], which together asserts that

AF is linked to extreme, sustained levels of exercise irrespective of the sport

type [42]. Dose-dependent relationships with exercise and AF incidence are also

depicted in the general population, with every 1000 steps being associated with

small, incremental increases in risk [43]. Overall, the connection between

high-intensity training and increased AF occurrence has been upheld across the

years by cohort studies of younger and mostly middle-aged athletes, and other

investigations into older athletic populations have echoed similar sentiments

[44, 45]. This latter point however may be confounded by an increased prevalence

of the aforementioned cardiovascular risk factors [46]. Nevertheless,

meta-analyses of this association show less certainty. Using many of the same

studies in their meta-analyses, Mishima et al. [47] (2021) and Kunutsor

et al. [48] (2021) revealed no increased AF risk with high-intensity

exercise; however, the latter study’s findings were segregated by gender—with

more pronounced AF risk at higher PA for men but less for women—and were

limited by a lack of studies in elderly populations. Even still, analysis of 13

athlete cohort studies with 70,478 participants illustrated markedly elevated

risk for AF compared to controls (Odds ratio: 2.46; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.73

to 3.51; p

In contrast to the exercise paradox, the most recent large-population studies

affirm that incorporating mild-to-moderate exercise helps reduce the incidence of

AF. In previously healthy patients, observational studies from a large cohort of

over 500,000 middle to older aged-individuals in the United Kingdom (UK) have shown

reduced incidence of AF in patients with metabolic equivalent (MET)-minutes per

week greater than 1500, high net oxygen consumption (VO

Overall, the newest research on exercise and incident AF utilizing wide-spanning cohorts maintain the assertion that those younger to middle-aged individuals achieving high levels of PA are at increased risk of acquiring AF, especially in populations comprised of athletes, but in the general and elderly athlete population, the results are unclear. Patients who adhere to guideline-recommended exercise standards, however, are more likely to confer protective benefits from AF. These data should be cautiously interpreted due to their liberal use of subjective data, being largely retrospective, and observational nature. More definitive statements about the relationship between CRF and incident AF will require more stringent study designs, with hope to the future in the Master@Heart (NCT03711539) [64] and Prospective Athlete’s Heart Study (NCT05164328) [65] prospective cohorts. Moreover, the international NEXAF Detraining study (NCT04991337) will investigate how reduced exercise levels impact management in endurance athletes with preexisting AF, thus elucidating further any possible connection between exercise levels and subsequent AF burden [66]. Despite the great work that has been accomplished in observing this relationship, the current research landscape often reports the effect of varying levels of PA on AF incidence without commenting on known socioeconomic risk factors that affect the development of AF, including gender and race.

Incorporating regular exercise for the prevention and management of AF is important for both men and women, but the differential impact of gender should be considered before making recommendations. Both at rest and in response to exercise, notable differences exist in the structure and function of a female versus male hearts [67, 68, 69, 70]. Accordingly, the guidelines that utilize CRF in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of AF should ideally be developed with this sex-specific intention [71]. However, the available evidence from the most impactful cohorts involving the effect of exercise on AF in the general population predominantly consist of most—if not all—male participants or reports no gender-mediated distinctions [13, 15, 27, 56]. Even with this limitation in mind, recent data examining clinically-relevant differences in AF incidence according to sex with varying levels of exercise suggests increased benefit in women compared to men [72]. Using the large UK Biobank cohort, Elliott et al. [50] (2020) found that performing above guideline-recommended exercise levels up to 5000 MET-min/week exhibited increasing risk reduction in AF incidence in women, but not in men. In this sample, vigorous exercise in men led to a 12% increased risk of developing AF (hazard ratio: 1.12, 95% CI 1.01–1.25), which starkly contrasts with the observed 8–16% decreased risk of AF incidence in women (hazard ratio: 0.80, 95% CI 0.66–0.97). Similar results were found in a well-represented Korean population [54] and the Women’s Health Initiative Observation Study [73]; however, no differences were noted in the smaller Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study cohort [74]. Furthermore, multiple meta-analyses have supported the hypothesis that women have increased exercise tolerance compared to men when stratifying AF risk [48, 62, 75], although the newest data acknowledges potential confounding biases given the observational nature of the available evidence [76]. While men seem to have a greater prevalence of AF risk factors than women, women who are ultimately diagnosed with AF are more likely to have HTN, a positive smoking history, and hyperlipidemia than their male counterparts [77]. Therefore, investigators have explored this relationship and cited improved mitigation of risk factors such as blood pressure and body-mass index using exercise as the key drivers of decreased AF incidence in women versus men [78, 79]. Taken together, the available evidence cautiously suggests that women can safely pursue PA at higher levels than men without increasing risk of developing AF, which has important clinical implications when counseling female patients on how best to prevent future disease by improving their CRF.

In exercising athletes, AF risk differs between men and women. Consistent with previous observations in the general population, AF studies in athletes are primarily performed in predominantly male populations [36, 37, 39, 41] which has been acknowledged in subsequent meta-analyses [49]. Many factors have been implicated in the lack of studies in women athletes, such as historically low participation in sporting events, lack of overall AF events, shorter race distances, and decreased cumulative sports exposure [80, 81]. As summarized previously in those research efforts, well-conditioned men seem to suffer an increased risk of developing AF [36, 37, 38, 39, 41]. At this point in the literature devoted to female athletes, however, therein remains insufficient data to make the same conclusions with certainty. As a follow-up to the first report of increased AF risk in female athletes [81], Svedberg et al. [38] (2019) followed a cohort of competitive skiers (126,342 men and 82,312 women) and demonstrated decreased AF incidence in women at all levels of activity and athletic performance, but increased AF incidence in men who participated in more races and performed better compared to non-skier-matched controls. Contrarily, a recent research letter from Myrstad et al. [82] (2024) prospectively examined skiers from the Tromsø Study cohort and showed similar risk from cumulative exercise exposure, echoing previous findings seen before in only men. Another study in Sweden followed women athletes who had previously completed marathons and cycling at elite levels was the first of its kind to capture an increased risk of acquiring AF in the high-endurance athlete cohort (hazard ratio: 2.56; 95% CI 1.22 to 5.37) [83]. However, this latter investigation only had 228 individuals in the female athlete group, echoing previous challenges of surveying women athlete populations [80, 81]. Overall, more studies with greater inclusion of women athletes are needed to more appropriately guide AF consideration, and the upcoming Prospective Athlete’s Heart Study is actively recruiting men and women athletes and will help address this gap [65].

In summary, disparate levels of AF incidence are not only visualized across varying CRF and PA levels, but also through the influences of gender (Table 1, Ref. [13, 15, 27, 36, 37, 38, 39, 41, 44, 50, 51, 53, 54, 56, 57, 58, 72, 73, 74, 79, 81, 82, 83]). The current literature implicates high-intensity exercise in men with increased AF risk, yet the same does not hold true for women, although with more limited evidence. In both athlete and non-athlete populations, women are generally able to tolerate even extreme levels of PA without incurring the same potential of developing AF. Mechanistically, this could be due to simply a lack of available data or from differences in anatomy and responses to exercise, the latter of which will be explored in detail later in this review. Moving forward, special efforts should be made to include well-represented populations to better elucidate gender’s part in the relationship between AF and CRF.

| Men | Women | |

| Low-to-moderate intensity exercise | Decreased AF incidence | Decreased AF incidence |

| High-intensity exercise | Increased AF incidence | Decreased AF incidence* |

| Potential mechanisms | Differences in cardiac anatomy, risk factor reduction, and responses to exercise by sex | |

| Landmark studies in non-athletes by predominant gender representation | Kokkinos et al. (2008) [13] | Mozaffarian et al. (2008) [58] |

| Kokkinos et al. (2017) [15] | Azarbal et al. (2014) [73] | |

| Khan et al. (2015) [56] | Tikkanen et al. (2018) [51] ‡ | |

| Morseth et al. (2016) [57] ‡ | Garnvik et al. (2019) [72] | |

| Kamil-Rosenberg et al. (2020) [27] ‡ | Jin et al. (2019) [54] ‡ | |

| Elliott et al. (2020) [50] ‡ | ||

| Fletcher et al. (2022) [74] ‡ | ||

| Khurshid et al. (2023) [53] | ||

| Sharashova (2023) [79] ‡ | ||

| Landmark studies in athletes by predominant gender representation | Karjalainen et al. (1998) [36] | Myrstad et al. (2015) [81] |

| Baldesberger et al. (2008) [39] | Myrstad et al. (2015) [81] | |

| Andersen et al. (2013) [37] ‡ | Drca et al. (2023) [83] | |

| Myrstad et al. (2014) [44] | Myrstad et al. (2024) [82] ‡ | |

| Aagaard et al. (2019) [41] | ||

| Svedberg et al. (2019) [38] ‡ | ||

| Recommendation | In healthy men: | In healthy women: |

| Perform low-to-moderate PA, uncertain benefit for high-intensity exercise and potential for harm | Exercise without intensity restrictions,* but more studies are needed in athletic populations | |

AF, atrial fibrillation; PA, physical activity. *Based on the limited data available in the general population. ‡Includes both men and women.

Importantly, the impact of PA on AF risk can be observed through the sociocultural lens of race. Despite an increased prevalence of known AF risk factors and subsequently worse outcomes in Hispanic and Black populations [84], AF has a higher incidence in White individuals [85, 86]. Many causes of this association have been hypothesized, including genetic predisposition due key susceptibility loci present in individuals of European descent but absent in other ethnicities [87]. While the true driver behind this observation is likely multifactorial, some believe this may be due to increased diagnosis, awareness, and other lifestyle factors in White patients compared to non-Whites [34, 88, 89]. Even still, the role of exercise in reducing incident AF in different racial communities remains unclear. Many of the aforementioned large observational studies are performed on mostly non-diverse populations, and they control for race in their findings using statistical predictive models or fail to comment on any potential influence [50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56]. Of the recent major studies that have included race, exercise affects incident AF risk in all ethnic groups in similar fashions [74, 90]. This is consistent with the previous reports comparing all racial populations. Nevertheless, therein remains a great need for more work that explores racial differences, as the current evidence of PA’s influence on AF is largely based on populations that are homogenous, thus limiting comparison to other non-represented persons. In particular with athletes, the hallmark studies in the field have been examined in majorly White participants [36, 37, 38, 39, 41]. We located one single study with sufficient representation of non-White subjects. This study was performed in former NFL players and showed that Black race was independently associated with decreased AF risk in high-strength training athletes, a finding that warrants further investigation in diverse athletes in different sport types [41].

Even with an apparent lack of studies specifically analyzing this relationship,

others have investigated ethnicity’s role on the several established measures of

CRF that factor into the larger, more pertinent studies with AF. Some articles

have reported racial differences in VO

Indeed, while race has not yet been shown to definitively stratify incident AF risk in exercising individuals, non-White populations remain more susceptible to predisposing, known predictors of AF. In all areas of cardiovascular health, efforts to reduce development of and death from cardiovascular disease have been disproportionately unsuccessful in specific racial demographics, especially African Americans [101]. The cause of this inequality is complicated, with evidence emerging that reveals exercise as a varied effect modifier on known AF risk factors in diverse ethnic groups [102]. Therefore, integrating CRF-improving programs must consider the needs of different racial communities to prevent AF incidence and other cardiovascular comorbidity. To this point, no prospective studies have been specifically designed to capture race-sensitive interventions to prevent incident AF. However, future studies can look towards previously successful, cardiovascular-focused interventions to decrease abundant AF risk factors common to these vulnerable groups. Most population-based clinical trials have focused on Black individuals and encouraged exercise through exercise sessions, educational classes, social cohesion, and smart-phone applications to favorably improve short and long-term exercise adherence [103, 104, 105, 106]. Studies in Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and South Asian American groups integrated culturally-specific teaching and community sessions to promote PA and improve AF risk factors of high blood pressure, DM, and obesity [107, 108, 109]. Given the lack of statistically significant efficacy of such programs in adult Latino populations, additional investigations are ongoing to identify successful PA-improving strategies in this community [110].

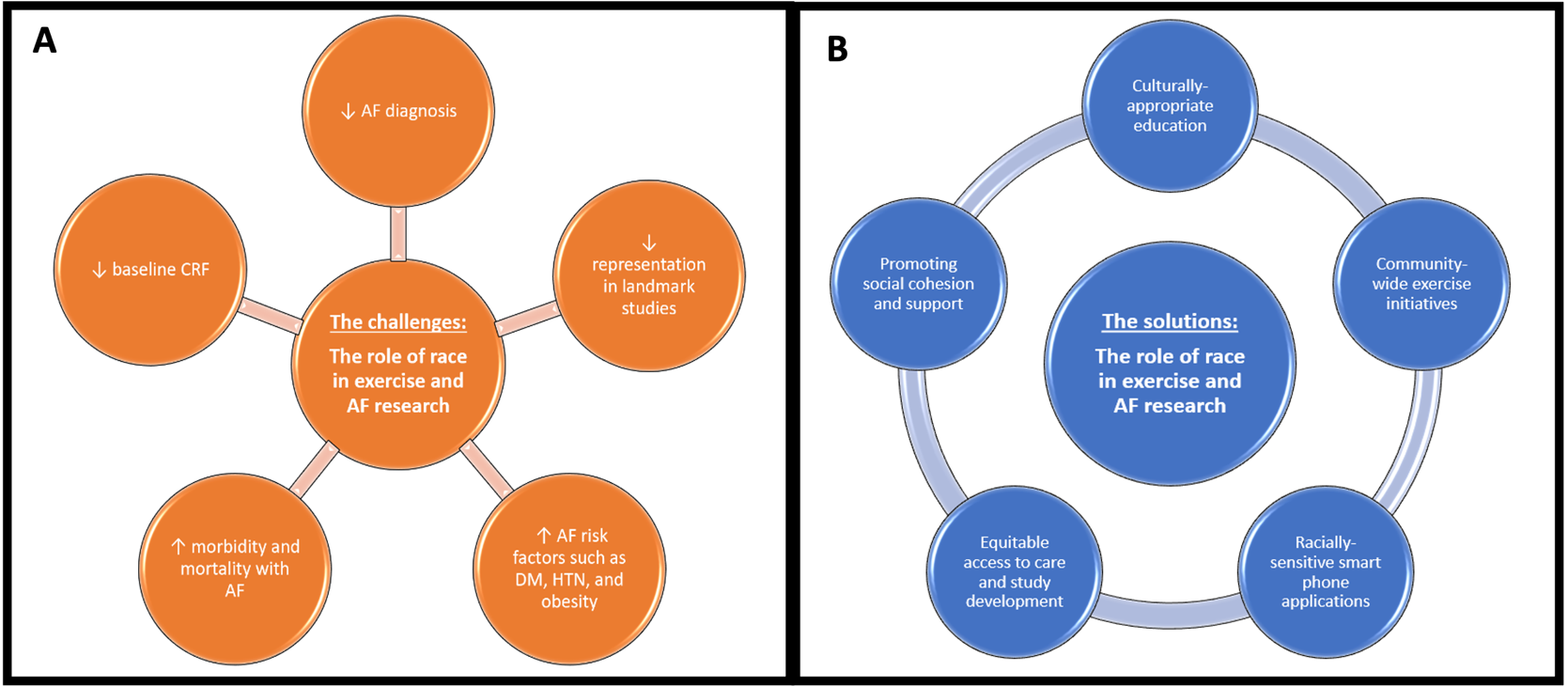

Overall, the evidence surrounding CRF differences and interventions for AF in diverse populations is sparse at best. For the translational advancement of the field, it is vital for future research to include and consciously stratify individuals from various ethnic backgrounds during study design and data collection. An understanding of these unique challenges (Fig. 1A) has preceded creative solutions to target these vulnerable groups and permitted subsequent research on the effect PA on AF (Fig. 1B). Therefore, developing culturally specific interventions should be considered when hoping for the best success in preventing incident AF with exercise.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.The obstacles and solutions observed in the investigations examining atrial fibrillation (AF) and exercise. (A) Issues related to performing research in minority groups and the unique challenges they face. (B) Successful initiatives in vulnerable racial populations. CRF, cardiorespiratory fitness; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension.

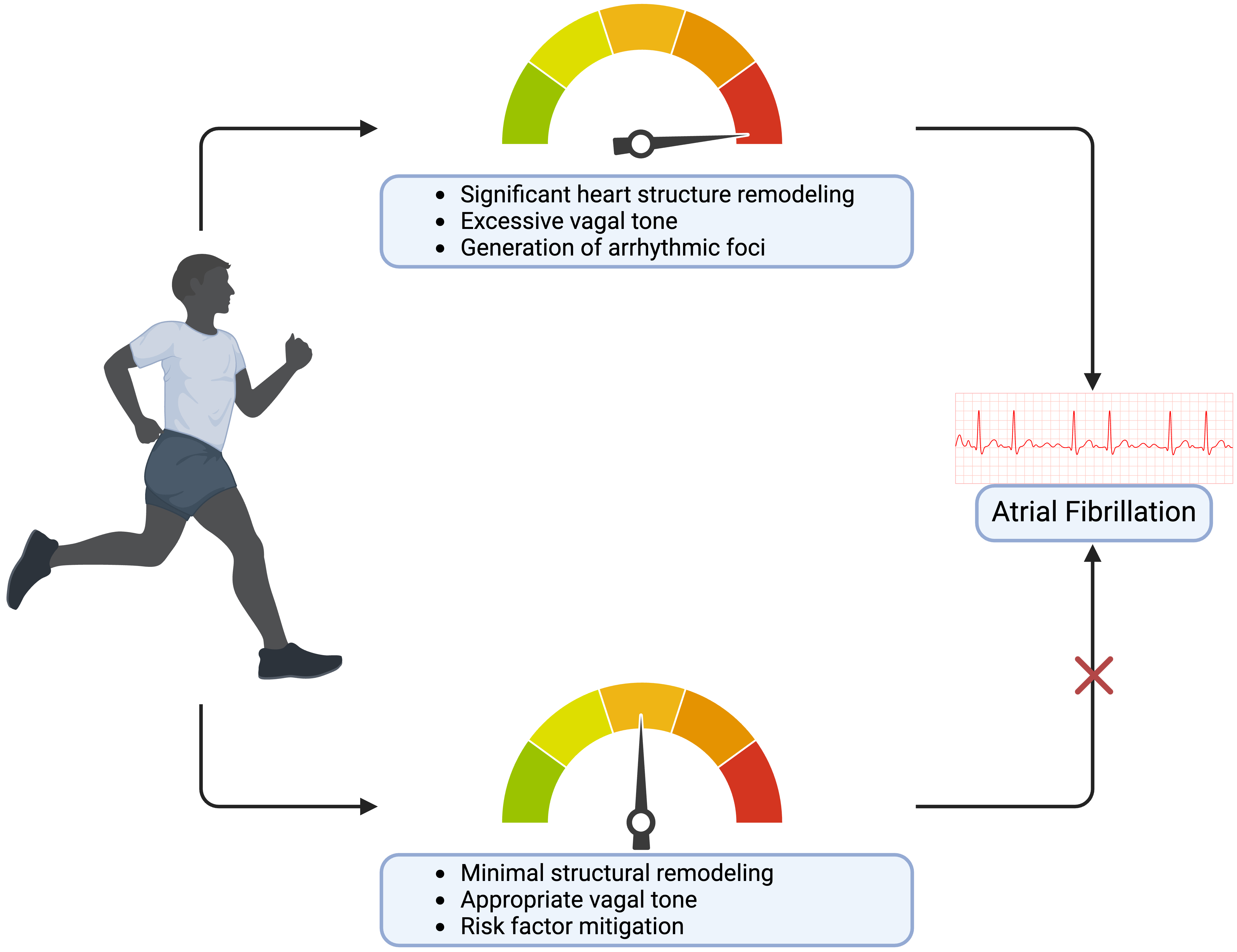

Exercise is often prescribed by providers to patients at high-risk for AF, but before doing so, it is important to recognize how the effects of PA on heart structure and function can become deleterious. Clinical data suggests that high-intensity endurance athletes are more prone to developing AF than others who limit exercise to moderate levels [111, 112, 113]. The pathogenesis behind this paradox can first be explained by examining the root causes of AF—the formation of ectopic foci in the heart by arrhythmic triggers. This unsynchronized firing leads to AF and begets structural changes. Specifically, increased vagal tone, atrial inflammation, fibrosis, cardiac remodeling, and left atrium enlargement are known causes of AF and may trigger these ectopic foci in high-performance athletes [114]. Subsequently, these compounding structural and electrical adaptations from exercise result in the development of AF. Furthermore, a training athlete’s heart adapts to high-intensity exercise by increasing left ventricular diameter and volume, which is believed to subsequently increase vagal tone [115]. Trivedi et al. [116] (2020) examined athletes with AF and observed preserved left ventricular diastolic parameters with enlarged right atria compared to control. Instead, structural changes in nonathletes with AF had diastolic dysfunction and reduced left atrial strain, indicating a difference in pathophysiological mechanism as a result of exercise [116]. Differences in left and right heart structure and function were also observed according to athletic status and presence or absence of AF in older patients [117, 118, 119]. In a state of profound dominance of vagal tone, the parasympathetic nervous system is heightened, and sympathetic activity is diminished. This represents a sharp departure from the extreme sympathetic surge at the height of PA, with the increased vagal tone at rest disrupting the balance between the two systems. For this reason, autonomic imbalance has been hypothesized to play a significant role in the onset of AF, yet more studies are needed to confirm this belief [120]. Additionally, evidence suggests that intensity and duration of exercise is proportional to heart structure remodeling, which in turn increases one’s susceptibility to AF [121]. This pathogenesis has been hypothesized mainly for aerobic exercise, with little data available to explain one finding of increased AF risk in primarily resistance-trained athletes [41]. Taken together, this could explain how the exercise paradox in highly active populations results in increased AF incidence (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.The risks and benefits of varying exercise levels on atrial fibrillation. Created on https://www.biorender.com/.

Current investigations implicate high-intensity training in the development of AF in men, but not in women, and variances in heart anatomy may be able to partially clarify gender’s differential effect of AF incidence stratified by exercise. Early research discovered that female endurance athletes have lower cardiac output, diastolic filling rate, left ventricular ejection rate, and a higher maximum arteriovenous global oxygen delivery compared to their male endurance athlete counterparts [68]. This suggests that under high-intensity exercise, the female heart experiences less sympathetic escalation and thereby less compensatory parasympathetic innervation, which together functions to prevent increased vagal tone and overall decreases the likelihood of incident AF [112, 122]. Conversely, male endurance athletes have significantly larger left atrial volumes, which create the anatomical substrates that propagate the re-entry mechanisms at the heart of AF [69]. Accordingly, male endurance athletes undergo more severe cardiac remodeling that exacerbates AF incidence when compared to females. Left ventricular characteristics is another commonly used metric for diagnosing AF, and one study comparing the left ventricle geometry of male and female athletes across various sports found that female athletes undergo restructuring less frequently than male athletes [70]. This supports the long-standing theory that higher activity levels lead to more heart remodeling.

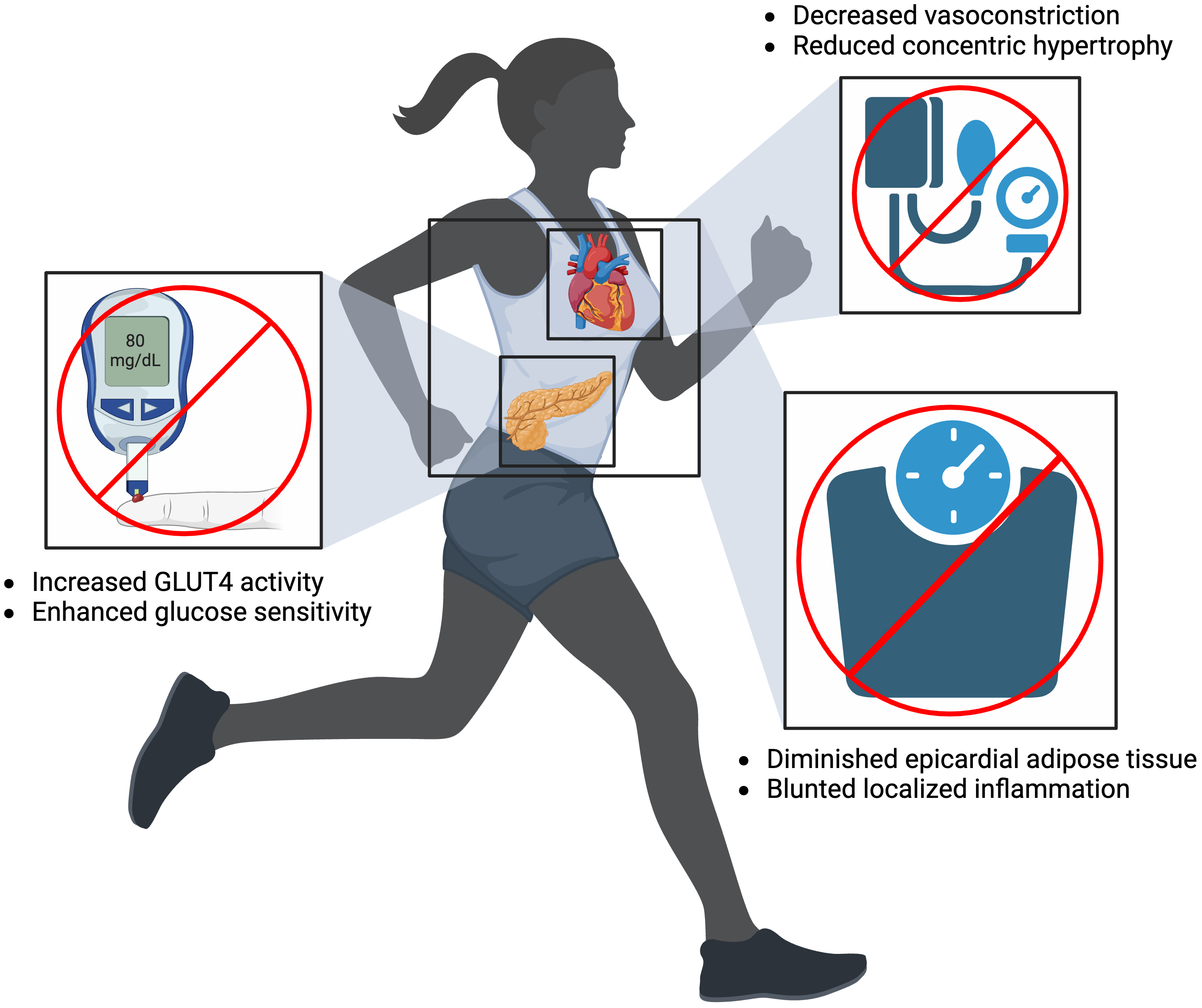

Improving PA is a particularly effective method of mitigating AF risk factor

development. Common risk factors for AF have been shown to induce structural and

electrophysiological abnormalities by creating conditions for aberrant reentry

and focal ectopic activity [4]. For example, physical inactivity is a common

cause of HTN and a known risk factor of AF. Sedentary lifestyles relegate the

body to a state of decreased metabolic demands. This leads to the closure of

precapillary sphincters and vascular beds to then decrease nitrous oxide

production in endothelial cells, which promotes vasoconstriction and subsequent

HTN [123]. Over time, HTN promotes concentric hypertrophy, which eventually leads

to AF due to maladaptive heart anatomy. Encouraging exercise reverses this

cascade of events and thus prevents the development of HTN. Increasing PA also

prevents AF by combating obesity. Similar to HTN, obesity is associated with poor

CRF. Low metabolic demands equate to decreased glucose usage and increased fat

storage everywhere in the body, including the heart. Epicardial adipose tissue

(EAT) specifically acts as a direct trigger for AF by increasing local

inflammation via inflammatory cytokines (interleukin (IL)-1

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Mitigating atrial fibrillation risk factors of diabetes mellitus (left), hypertension (top right), and obesity (bottom right) by increasing physical activity. Created on https://www.biorender.com/. GLUT4, glucose transporter type 4.

In conclusion, those who participate in regular, moderate PA have displayed the greatest outcomes in AF prevention and management by reaping the most benefit from exercise without experiencing its pitfalls. Moderate PA promotes strengthening of the heart and mitigation of AF risk factors without skewing the autonomic nervous system balance. High-intensity exercise, however, leads to increased vagal tone and changes in heart anatomy that serve as a nidus for AF. Hence, increasing CRF with exercise to the extent that maintains heart health and autonomic nervous system balance will promote normal heart rhythm.

Contrary to the debate circulating exercise and AF primary prevention, the

evidence supporting CRF enhancement in patients with AF is much more concrete.

The majority of studies involving exercise in patients with AF are observational

and associate increased PA with decreased major adverse cardiovascular events,

improved mortality, increased tolerance of damaging comorbidities, better

ablation outcomes, and reduced symptoms [131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137]. While these populations

provide important relationship data to the field, the RCTs that explore this

dynamic permit even stronger conclusions to be made: Exercise remains a

cornerstone for treatment of preexisting AF patients. Some research in the area

have targeted CRF and quality of life parameters as clinical outcomes, as

patients with AF who perform aerobic exercise demonstrate better symptom control,

physical functioning, exercise capacity, handgrip strength, 6-minute walk tests,

and peak VO

As previously discussed, patients without AF may face increased risk at higher exercise levels, yet this contrasts with the noted benefits from high-intensity training in patients with preexisting AF. This may be due to short average follow-up times of 12–16 weeks, the high-reward PA benefits in sedentary individuals, increased risk factor burden and subsequent modification, and/or a lack of continuous exposure over cumulative exercise years. Therefore, given the evidence surrounding the exercise paradox, concern is warranted in prescribing the appropriate amount of exercise in AF. Just the same, Skielboe et al. (2017) [146] asserted no difference in AF burden or hospitalizations due to AF in patients randomized to high or low-intensity with a 1-year follow-up. However, this lies contradictory to the dose-dependent decreased AF risk seen in rising exercise levels depicted in the CARDIO-FIT prospective cohort, which creates further uncertainty [147]. The upcoming NEXAF Detraining study should help to clarify some of these observations [66]. Increasingly, many of the previous and upcoming investigative trials choose exercise programs and risk factor modification strategies to accomplish weight reduction endpoints and treat AF, one of the most notable being the LEGACY cohort [148]. In combination with diet modification and lifestyle counseling, the LEGACY trial examined the long-term effect of low-to-moderate intensity exercise on patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF and found decreasing AF burden and arrhythmia-free survival in the group with the most weight loss, which was maintained over the course of several years [148]. The RACE 3 trial similarly targeted known AF risk factors through a combination of pharmacological and exercise interventions and showed improved restoration of sinus rhythm after 1-year [149]. While the results of these RCTs are promising, the most impactful trials cited by the 2023 guidelines on the diagnosis and management of AF [3] feature key limitations within the makeup of study participants. Many trials examining AF treatment with PA have very limited representation of women [138, 140, 141, 142, 144, 148, 149, 150]. Similarly problematic, the racial demographic of those people included is almost universally underreported or, as seen in the one trial, compromised of strictly White individuals (approximately 97% in all groups) [146].

While further details are outside the scope of this review, it is important for cardiologists to encourage regular, guideline-recommended PA in patients with all forms of AF. Multiple RCTs demonstrate favorable short and long-term outcomes and significant improvements in symptomology. There is still a great need for improved representation of diverse racial groups and female patients in current investigations to help understand the unique characteristics of each population. Special considerations should also be made for patients with differing comorbidity burden [151], which modulates the degree a patient should exercise for maximum benefit. The results and makeups of the most significant RCTs studying CRF and AF are depicted in Table 2 (Ref. [138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 146, 149, 150]).

| Trial | Population | Intervention | Notable results | Gender demographic (male) | Racial makeup |

| Hegbom et al. (2007) [138] | Chronic AF (n = 28) | Aerobic and muscle strengthening exercise program compared to no training | - Improved SF-36 and SSCL in EG | Treatment: 100% | Not reported |

| - Improved exercise capacity and perceived exertion in both groups | Control: 87% | ||||

| Osbak et al. (2011) [139] | Permanent AF (n = 51) | Aerobic exercise program compared to no training | - Improved 6MWT, exercise capacity, MLHF-Q, and SF-36 in EG | Treatment: 43% | Not reported |

| Control: 43% | |||||

| CopenHeart |

Paroxysmal or persistent AF undergoing ablation (n = 210) | Cardiac rehabilitation with exercise training compared to usual care | - Improved peak VO |

Treatment: 74% | Not reported |

| - No difference in SF-36 between both | Control: 77% | ||||

| - Increased non-serious adverse events in EG (16 versus 7, p = 0.047) | |||||

| Malmo et al. (2016) [141] | Symptomatic, non-persistent AF (n = 51) | Aerobic interval training compared to usual exercise habits | - Improved mean time in AF, SF-36, SSCL, peak VO |

Treatment: 77% | Not reported |

| Control: 88% | |||||

| Skielboe et al. (2017) [146] | Paroxysmal or persistent AF | High-intensity or low-intensity aerobic exercise | - No difference in AF burden and hospitalization | High-intensity: 59% | 97% White in both groups |

| (n = 70) | - Both groups improved peak VO |

Low-intensity: 58% | |||

| Rienstra et al. (2018) [149] | Early persistent AF and mild-to-moderate HF (n = 245) | Aggressive risk factor modification with pharmacology, lifestyle counseling, and cardiac rehabilitation | - Increased percentage of restored sinus rhythm in EG | Targeted therapy: 79% | Not reported |

| - Improved risk factor control* in EG | Conventional therapy: 79% | ||||

| - Similar LVEF improvements and hospitalizations due to AF in both groups | |||||

| Kato et al. (2019) [142] | Persistent AF undergoing ablation (n = 6) | Cardiac rehabilitation with exercise training compared to usual care | - Improved 6MWT, handgrip and leg strength, and LVEF in EG | Treatment: 71% | Not reported |

| - No difference in AF recurrence | Control: 90% | ||||

| ACTIVE-AF [143] | Symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent AF (n = 120) | Patient-tailored exercise program compared to usual care | - Improved freedom from AF after 12 months and AFSS after 6 and 12 moths in EG | Treatment: 58% | Not reported |

| - Both groups increased peak VO |

Control: 57% | ||||

| Alves et al. (2022) [144] | HFrEF with permanent AF (n = 26) | Aerobic and muscle strengthening exercise program compared to no training | - Improved peak VO |

Treatment: 100% | Not reported |

| - Decreased resting HR, recovery HR in EG | Control: 100% | ||||

| - Increased LVEF and structural morphology in EG | |||||

| Reed et al. (2022) [150] | Persistent or permanent AF (n = 86) | High-intensity interval training compared to moderate-to-high intensity continuous training | - No difference 6MWT, SF-35, AFSS, and time in AF between high-intensity interval training and moderate-to-high intensity continuous training | Treatment: 67% | Not reported |

| Control: 65% |

AF, atrial fibrillation; EG, experimental group; SF-36, short-form 36; SSCL,

Symptom and Severity Checklist; 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; MLHF-Q, Minnesota

Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire; LA, left atrial; LVEF, left ventricular ejection

fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection raction; HR, heart rate;

AFSS, Atrial Fibrillation Symptom Severity Questionnaire; VO

In conclusion, the field of CRF in patients with and without AF is rapidly growing but requires some nuance in interpretation of the current evidence. AF is an exacting disease with significant mortality and morbidity. To combat this condition, increasing PA levels can improve several AF risk factors—such as obesity, HTN, and DM—by decreasing vasoconstriction, reducing ETA, and modulating insulin sensitivity. However, recent evidence continues to support the longstanding theory that high-intensity exercise leads to elevated AF incidence, especially in athletes. Extreme levels of physical activity can potentially lead to the formation of harmful triggers, which in turn may cause increased vagal tone resulting in imbalanced sympathetic and parasympathetic activity and subsequent changes in cardiac anatomy. Providers may safely counsel patients of all ages to perform guideline-recommended amounts of low-to-moderate PA; however, prescribing high-intensity exercise remains controversial with unclear benefit at this point. Even still, analysis stratified by sex has revealed decreased AF risk in women following exercise even at extreme levels. This can potentially be explained by differences in hemodynamics and structural responses to exercise by men and women. Nevertheless, most of the research investigating this association between CRF and AF is observational and is therefore inherently limited. For this reason, the optimal level of exercise intensity remains unknown. Similarly, the vast majority of studies include racially homogenous individuals, and as such, forthcoming research should address this need for representation in diverse ethnic groups, specifically Black, Latino, and Asian athlete and non-athlete populations. These groups face inordinately high burden of AF risk factors that can be addressed by enhancing exercise levels, which necessitates follow-up studies to determine the best strategy in doing so. Finally, superior evidence in RCTs in patients with preexisting AF has demonstrated marked improvements in clinically significant AF outcomes and patient quality of life. Despite the current limitations, using CRF to counter the consequences of AF has great promise, and future investigation should expand the discipline by learning more about its place in select racial and gender groups.

AT designed the research study. EC and SAS performed the background literature review. EC and SAS wrote the manuscript. AT provided comments and edits to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The authors would like to thank the MedStar Health Department of Electrophysiology for their continued support of this manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.