1 Fundación Neumológica Colombiana, 110131 Bogotá, Colombia

2 Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de la Sabana, 250001 Chía, Colombia

3 Postgraduate Program in Sports Medicine, Universidad El Bosque, 110121 Bogotá, Colombia

Abstract

Background: Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) assesses exercise

capacity and causes of exercise limitation in patients with pulmonary

hypertension (PH). At altitude, changes occur in the ventilatory pattern and a

decrease in arterial oxygen pressure in healthy; these changes are increased in

patients with cardiopulmonary disease. Our objective was to compare the response

to exercise and gas exchange between patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and chronic

thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) residing at the altitude of

Bogotá (2640 m). Methods: All patients performed an incremental CPET

with measurement of oxygen consumption (VO

Keywords

- pulmonary arterial hypertension

- chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

- altitude

- exercise tolerance

- cardiopulmonary exercise test

- blood gas analysis

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a chronic and progressive disease that increases pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), ultimately leading to right ventricular failure. Regardless of the underlying disease, PH is almost always associated with progressive exercise intolerance, dyspnea, and increased mortality [1, 2, 3].

In clinical settings, the cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) is very useful for pulmonologists and cardiologists in the follow-up of patients with PH. It is used to evaluate exercise tolerance, exertional dyspnea, and related underlying pathophysiological mechanisms; it can suggest the diagnosis of PH and differentiate between possible causes. Moreover, some of the exercise variables are used as prognostic factors, mainly in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) [4, 5]. In CTEPH, CPET is useful in detecting the disease, establishing severity, and identifying causes of exercise intolerance [6, 7]. Likewise, it has been described that patients with CTEPH have greater dead space, ventilatory inefficiency, and more severe alterations in gas exchange during exercise than patients with PAH [8].

High altitude is an elevation over 2500 m (~8200 feet) [9].

Although the physiological responses to hypobaric hypoxia start at lower

elevations, they are more pronounced above this altitude, and the risk of

developing altitude illness also increases substantially [10]. At altitude, the

barometric pressure (BP) decreases, meaning the inspired oxygen pressure

(PIO

In patients with PH who live at high altitude, in addition to the

pathophysiological alterations related to pulmonary vascular compromise, changes

related to the decrease in PIO

A retrospective study was performed using 53 consecutive patients with PH referred from the institution’s pulmonary vascular disease program between 2015 and 2020 to the Pulmonary Function Tests Laboratory of the Fundacion Neumologica Colombiana in Bogotá, Colombia (2640 m) for a CPET. The Institution’s Research Ethics Committee approved the conduct of the study and the anonymous use of the data (authorization number: 202111-26803). A control group of 102 subjects of similar age and with normal spirometry was used to reference the normal response during exercise at altitude. The control subjects were required to have no history of cardiopulmonary disease, obesity, or smoking.

To exclude secondary changes to the ascent to altitude, all patients and controls were to have been born and currently reside in Bogotá. Patients with PH should have been clinically stable for at least 6 weeks and without changes in targeted treatment for PH in the last 2 months. New York Health Association (NYHA) functional classification data and medications were recorded at the time of CPET. Hemodynamic variables were obtained from resting right heart catheterization (RHC) performed in the last three months.

PAH was defined as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (PAPm)

Spirometry and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) were performed on a V-MAX Encore (CareFusion, Yorba Linda, CA, USA) according to the standards of the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society and Crapo reference equations were used [16, 17, 18]. A certified 3 L syringe was used for calibration. Flows and volumes were reported according to BTPS conditions (body temperature, ambient pressure, saturated with water vapor).

All patients performed a symptom-limited incremental test on a cycle ergometer

that began with a 3-minute rest period, followed by 3 minutes of unloaded

pedaling, and a subsequent increase in workload every minute until the maximum

tolerated level was reached [19]. The increment (10–25 watts) was selected

depending on the reported exercise tolerance and resting functional impairment.

The work rate (WR), oxygen uptake (VO

The arterial blood gases (ABG) sample was taken at rest and peak exercise. The alveolar–arterial

oxygen tension gradient (PA-aO

Continuous variables are presented as the mean and standard deviation or median

and interquartile range according to their distribution following evaluation by

the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Qualitative variables are presented as proportions.

To compare the variables at rest and peak exercise between the 3 groups (PAH,

CTEPH, and controls), the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test or the one-way ANOVA

test was used, with the Bonferroni post hoc test applied for multiple

comparisons. The X

A total of 53 patients with PH were analyzed: 73.6% women, 29 in the PAH group,

and 24 in the CTEPH group. The 102 controls included were the same age, sex, and

body mass index (BMI) as the PH patients. Patients with PAH were younger

(p

| Variable | Controls | PAH | CTEPH | p | |

| N = 102 | N = 29 | N = 24 | |||

| Age, years | 50.0 |

45.2 |

55.5 |

0.034 | |

| Women | 71 (69.6) | 22 (75.9) | 17 (70.8) | 0.807 | |

| BMI, kg/m |

26.0 |

25.3 |

27.4 |

0.099 | |

| Smoking history | - | 4 (13.8) | 5 (20.8) | 0.715 | |

| Hb, gr/dL | 15.2 |

14.9 |

15.4 |

0.597 | |

| FVC, % predicted | 104.9 |

98.2 |

92.8 |

||

| FEV |

103.2 |

92.6 |

83.7 |

||

| FEV |

80.6 |

78.4 |

73.4 |

||

| DLCO, % predicted | - | 86.6 |

77.2 |

0.146 | |

| NYHA |

- | 18 (62.1) | 21 (87.5) | 0.037 | |

| Hemodynamics | - | ||||

| 36.0 (28.5–62.0) | 45.0 (35.0–56.0) | 0.454 | |||

| 6.2 (3.6–15.0) | 6.9 (5.5–10.9) | 0.628 | |||

| 12.0 (11.0–14.0) | 13.0 (11.0–17.0) | 0.055 | |||

| 10.0 (7.5–13.0) | 12.5 (10.0–14.0) | 0.054 | |||

| 2.9 (2.5–3.5) | 2.7 (2.4–3.3) | 0.685 | |||

| 67.0 (65.0–71.0) | 66.0 (62.5–72.0) | 0.415 | |||

Values as a mean

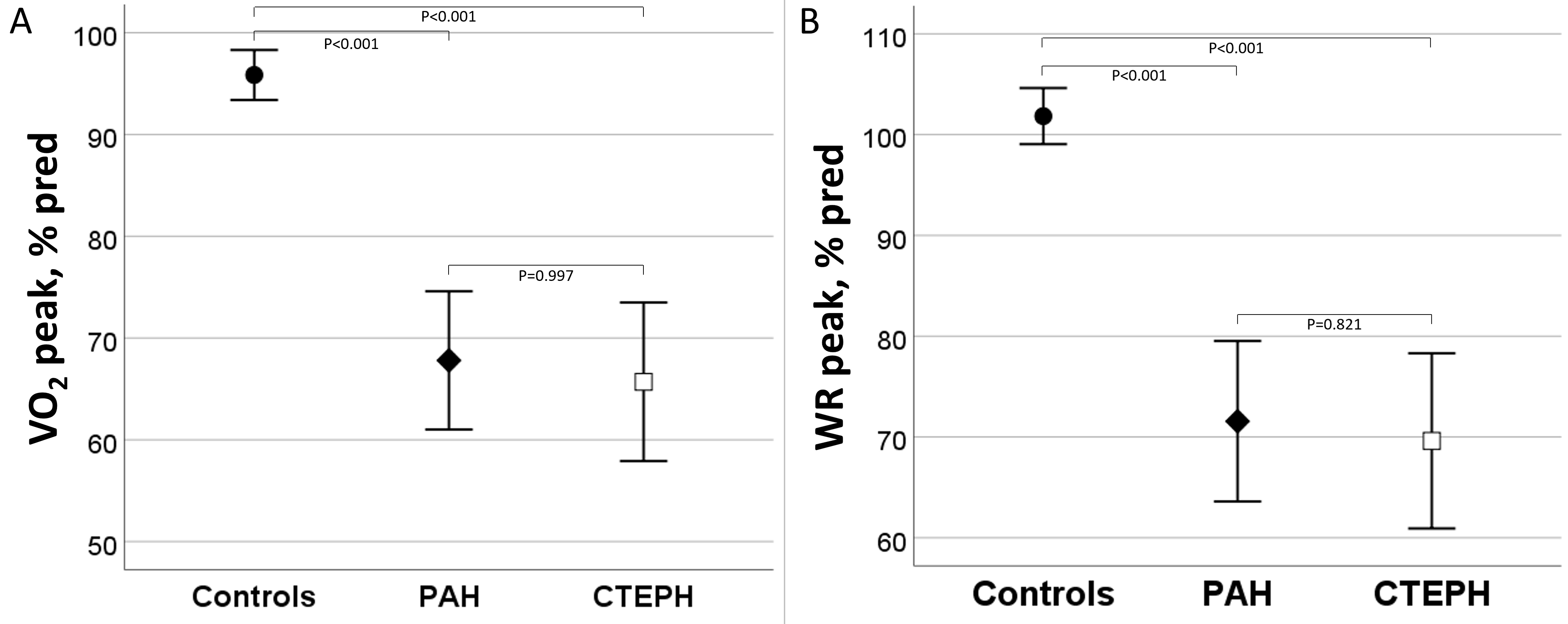

At peak exercise, patients with PH had a lower VO

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Oxygen consumption and work rate at peak exercise in controls,

PAH and CTEPH. (A) Oxygen consumption (VO

| Variable | Controls | PAH | CTEPH | p |

| N = 102 | N = 29 | N = 24 | ||

| WR, % predicted | 101.8 |

71.9 |

69.8 |

|

| Peak VO |

95.8 |

67.8 |

66.0 |

|

| VO |

25.4 |

18.1 |

15.7 |

|

| VO |

57.6 |

46.5 |

48.3 |

|

| ∆VO |

10.8 |

8.3 |

8.3 |

|

| RER | 1.18 |

1.16 |

1.09 |

|

| HR, % predicted | 88.5 |

76.6 |

78.7 |

|

| VO |

108.7 |

88.0 |

86.8 |

|

| VE, L/min | 73.2 |

54.2 |

56.3 |

|

| VT, mL/min | 1842.9 |

1431.9 |

1465.4 |

|

| fR, rpm | 39.8 |

37.7 |

40.5 |

0.340 |

| VE/MVV, % | 59.3 |

48.3 |

57.5 |

|

| VE/VCO |

34.2 |

39.3 |

45.8 |

|

| Leg discomfort, Borg | 5.8 |

6.2 |

5.4 |

0.558 |

| Dyspnea, Borg | 5.1 |

4.3 |

6.1 |

0.020 |

| Dyspnea/VE peak | 0.08 |

0.09 |

0.13 |

Values as a mean

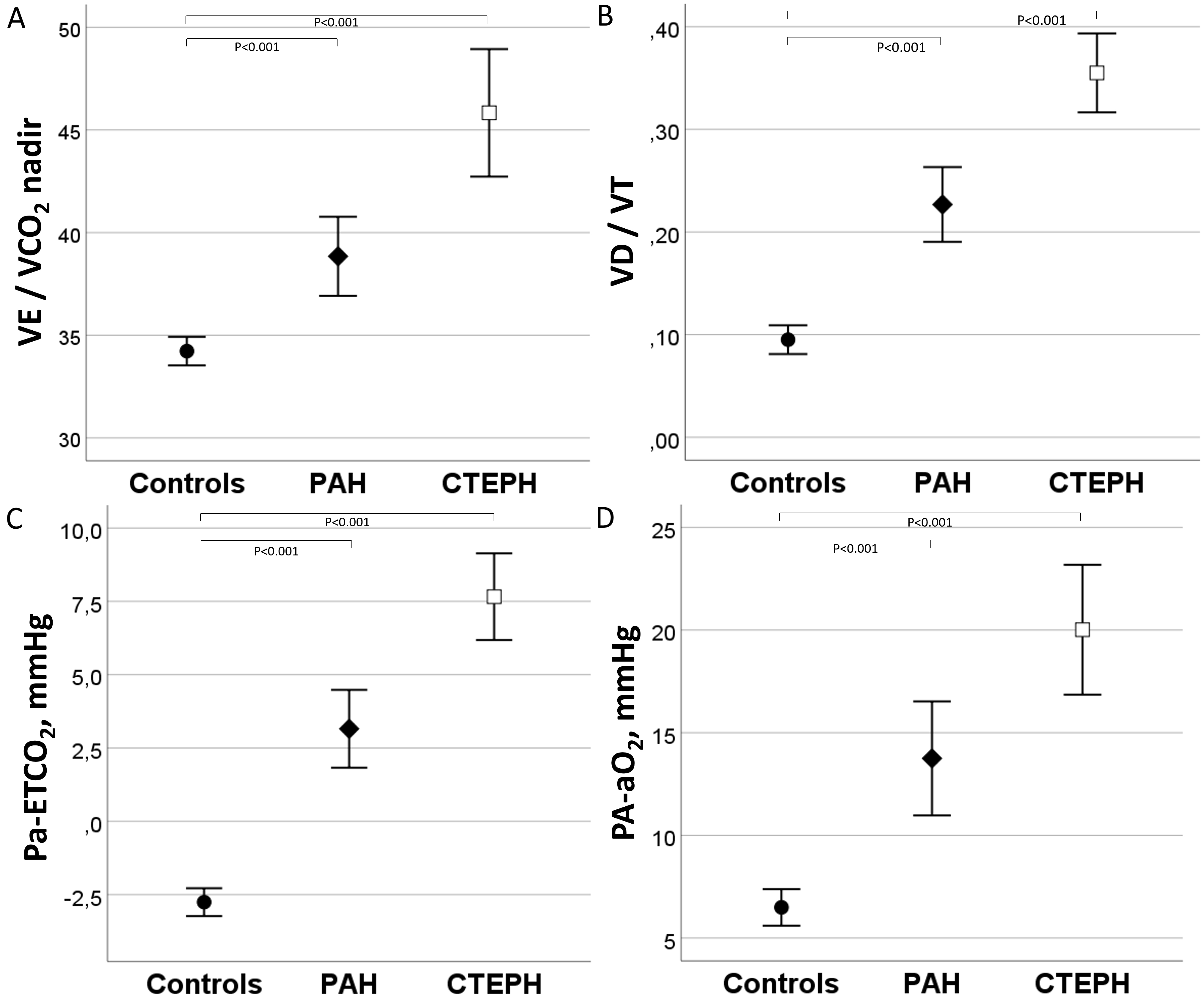

During exercise, control subjects achieved a higher VE and VT and lower

VE/VCO

There were no differences in VE, VT, and fR at peak exercise between the PAH and

CTEPH groups. The VE/MVV was higher in CTEPH than PAH (Table 2). At rest, the

CTEPH patients had a higher VD/VT and PA-aO

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.VE/VCO

| Variable | Rest | Peak exercise | ||||||

| Control | PAH | CTEPH | p | Control | PAH | CTEPH | p | |

| Subjects | 102 | 29 | 24 | 102 | 29 | 24 | ||

| PaCO |

31.0 |

32.0 |

31.8 |

0.107 | 28.1 |

31.0 |

32.2 |

|

| PaO |

66.6 |

62.7 |

57.7 |

77.8 |

67.4 |

58.3 |

||

| SaO |

93.6 |

91.9 |

90.0 |

94.5 |

91.2 |

87.8 |

||

| PA-aO |

6.4 |

9.1 |

14.4 |

6.5 |

13.5 |

19.9 |

||

| PETCO |

29.7 |

29.2 |

25.8 |

30.9 |

28.2 |

24.7 |

||

| VD/VT | 0.29 |

0.32 |

0.41 |

0.10 |

0.23 |

0.36 |

||

| Pa-ETCO |

1.2 |

2.7 |

6.0 |

–2.8 |

2.9 |

7.4 |

||

Values as a mean

At peak exercise, there was no difference in the fatigue of the lower limbs

between PAH, CTEPH patients, and controls (p = 0.558). Analysis using

the Borg scale revealed dyspnea (6.1

The main findings of this study, which assessed a significant number of PH

patients residing at high altitude were the following: (1) In comparison to the

controls, PH patients had lower exercise capacity (peak VO

In this study, in subjects living at high altitude, as expected, there was lower

exercise capacity (peak VO

Although there were no differences between PAH and CTEPH in hemodynamics, peak

VO

Consistent with our results, a previous study described significantly lower

PETCO

Several potential mechanisms could explain the differences in gas exchange and ventilatory efficiency during exercise between PAH and CTEPH. In CTEPH, there is anatomical compromise and heterogeneity in pulmonary blood flow. In addition to intravascular obstruction of the pulmonary arteries by unresolved organized fibrotic clots, pulmonary vascular remodeling can lead to severe pulmonary microvasculopathy, which affects the small muscular pulmonary arteries, pulmonary capillaries, and veins. Enlargement and proliferation of systemic bronchial arteries also occur, as well as anastomoses between the systemic and pulmonary circulations that promote the development of microvasculopathy [27, 28].

Although most patients with PH were non-smokers and those who had smoked had a

low pack-year index, the FEV

The decrease in FEV

Dyspnea also was more severe in CTEPH patients. Although the exact mechanisms related to dyspnea in PH patients are not completely understood [4], the increased dyspnea in the CTEPH group was probably explained by the higher VD/VT [8, 26] and ventilatory inefficiency and more severe gas exchange alterations than in PAH patients. Although we did not perform inspiratory capacity measurements through exercise, another possible mechanism that could be related to the increased exertional dyspnea intensity in these patients is dynamic hyperinflation (DH) [4, 35].

It is estimated that over 500 million humans live at

In control subjects, PaCO

In a recent study in patients with PAH and CTEPH, acute altitude exposure after ascending from 470 m to 2500 m caused a significant decrease in exercise capacity, ventilatory efficiency, and oxygenation [53]. It is striking that, despite these being patients at a slightly lower altitude than in our study, who also were in a better functional class and had lower pulmonary vascular resistance than the patients in our study, the level of hypoxemia at rest and during exercise was significantly higher. This indicates the presence of adaptive mechanisms in high-altitude resident subjects who are chronically exposed to hypoxia, which has been previously described in healthy subjects and in patients with other diseases, such as COPD [11, 12, 54].

This is the first study to evaluate exercise capacity and gas exchange

alterations in patients with PH living at high altitude. Moreover, including

patients with PAH, CTEPH, and control subjects allowed us to compare groups;

meanwhile, measuring the ABG and ventilatory variables comprehensively assessed

the limiting mechanisms of exercise in these patients with PH. Consistent with

several studies at sea level, conducting this study at high altitude we also show

a greater compromise in ventilatory efficiency and oxygenation in CTEPH than in

PAH patients, with no differences in VO

We consider that the clinical utility of CPET is to evaluate exercise capacity in individual patients and identify alterations in gas exchange related to the pathophysiology of PAH and CTEPH that could explain the functional class and dyspnea of these patients. Considering that adaptive mechanisms are performed when living at different altitudes above sea level, we think these research data mainly apply to patients with PH who reside at high altitudes.

This study had several limitations, such as the retrospective design and the small sample size. Despite this, the patients in each group had a full evaluation and confirmation of the diagnosis at the institution’s pulmonary vascular disease group board using accepted diagnostic criteria. Even though DH has been linked to exertional dyspnea in some patients with PH [4, 35], we did not have inspiratory capacity and dyspnea measurements throughout the exercise to assess these dynamic changes.

Although at sea level, it has been established that there is a relationship

between mortality in PH and some variables measured in CPET, such as peak

VO

At high altitude, patients with PH present severe gas exchange alterations during exercise. Although there were no differences in hemodynamics at rest or in exercise capacity between patients with PAH and CTEPH, those with CTEPH had greater dyspnea, ventilatory inefficiency, and alterations in gas exchange during exercise. The CPET allowed the identification of these alterations related to the pathophysiology of the CTEPH that could explain the lower functional class and dyspnea in these patients.

AT, anaerobic threshold; BP, barometric pressure; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise

test; CTEPH, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; FEV

The data set used for our analysis is available upon request from the corresponding author.

MGG, RCC, CRC, and ERA designed the research study. MGG analyzed the data. MGG, RCC, CRC, KD and ERA participated in the interpretation of data. MGG and ERA wrote the manuscript and all authors contributed to editorial changes. All authors participated sufficiently in the work and have agreed to be responsible for all aspects of it.

The Research Ethics Committee of the Fundación Neumológica Colombiana approved the study and the use of the anonymous data sets (approval number 202111-26803).

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.