1 Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University: First Hospital of Jiaxing, 314000 Jiaxing, Zhejiang, China

2 Department of Cardiology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University, 710061 Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is a clinical syndrome characterizing by typical physical signs and symptomatology resulting from reduced cardiac output and/or intracardiac pressure at rest or under stress due to structural and/or functional abnormalities of the heart. HF is often the final stage of all cardiovascular diseases and a significant risk factor for sudden cardiac arrest, death, and liver or kidney failure. Current pharmacological treatments can only slow the progression and recurrence of HF. With advancing research into the gut microbiome and its metabolites, one such trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO)—has been implicated in the advancement of HF and is correlated with poor prognosis in patients with HF. However, the precise role of TMAO in HF has not yet been clarified. This review highlights and concludes the available evidence and potential mechanisms associated with HF, with the hope of contributing new insights into the diagnosis and prevention of HF.

Keywords

- heart failure

- gut microbiota

- TMAO

- inflammatory response

- mitochondrial dysfunction

- fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)

Heart failure (HF) has persistently high incidence rates. Epidemiological data show that up to 64 million individuals globally are affected by HF, with the incidence in adults being 1% to 2%, and rising to over 10% in those aged over 70 [1]. HF is caused by a range of factors including myocardial damage, excessive cardiac load, and inadequate ventricular preload. It also has various precipitants, such as respiratory infections, arrhythmias, overloading of volume, and exacerbation of underlying diseases. Presently, HF treatment mainly involves the use of inotropic agents, diuretics, and vasodilators, as well as mitigating precipitating factors to manage the progression and recurrence of HF. Nevertheless, Current treatment methods address only a fraction of the assumed pathophysiological route, and the overall prognosis for HF is poor, with high rates of readmission and mortality. Notably, even in the PARADIGM study, the trial group’s 2-year mortality rate was a significant 20% [2]. Thus, there is an imperative to seek new therapeutic directions by finding novel pathophysiological mechanisms.

The gut microbiota is a sophisticated microbial complexity that lives in the human digestive tract and plays a crucial role in all physiological and immune processes of the human body [3]. Gut microbiota is composed of bacteria, virus, archaea, fungi and protozoa. Importantly, there are three main bacterial systems of intestinal microorganisms: Firmicutes (including Clostridia and Bacilli), Bacteroidota (including Bacteroides), and Actinobacteriota (including Bifidobacteria), with smaller amounts of Lactobacilli, Streptococci, and Escherichia coli [4]. Under normal physiological conditions, the gut microbiota is in a state of equilibrium. Imbalances in gut flora can lead to gut-related diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, allergic diseases, diabetes, autism, colorectal cancer and cardiovascular disease. In patients with HF, specific changes in the gut microbiota have been observed [5, 6]. Hayashi et al. [7] studied the gut microbiota composition of HF patients compared to a control group matched for age, gender, and comorbidities, to assess differences between the two groups. By sequencing the 16s rRNA gene amplicon, they found that the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium spp. was significantly increased, while that of Megamonas, was decreased in hyperlipidemic patients compared to controls [7]. However, Modrego et al. [8] showed an increase in Bifidobacterial abundance 12 months after a HF episode. Therefore to clarify the role of Bifidobacterium in heart failure, further samples of more in-depth fever studies are needed.

The metabolic products of the gut microbiota play a significant role in the body. For instance, Short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) have anti-inflammatory effects and chemopreventive properties, making them considered as tumor suppressors [9, 10]. One such metabolite, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), has been closely linked to cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and many other illnesses [11, 12, 13, 14]. Multiple studies have identified plasma TMAO as a predictive factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in various cohorts [15, 16, 17]. A meta-analysis showed that for every 10 µmol/L increase in TMAO, the risk of cardiovascular death rises by 7.6% [18], suggesting that elevated plasma TMAO levels signify a higher risk of long-term mortality [19]. Cui et al. [20] observed an upregulation of microbial genes regulating TMAO production in patients with HF. A possible mechanism is the impairment of the intestinal mucosal barrier in HF patients, leading to increased permeability and enabling easier translocation of TMAO into the bloodstream, which results in elevated plasma TMAO levels [17]. Other evidence also indicates that higher levels of TMAO in the blood are associated with increased mortality rates in patients with HF [21].

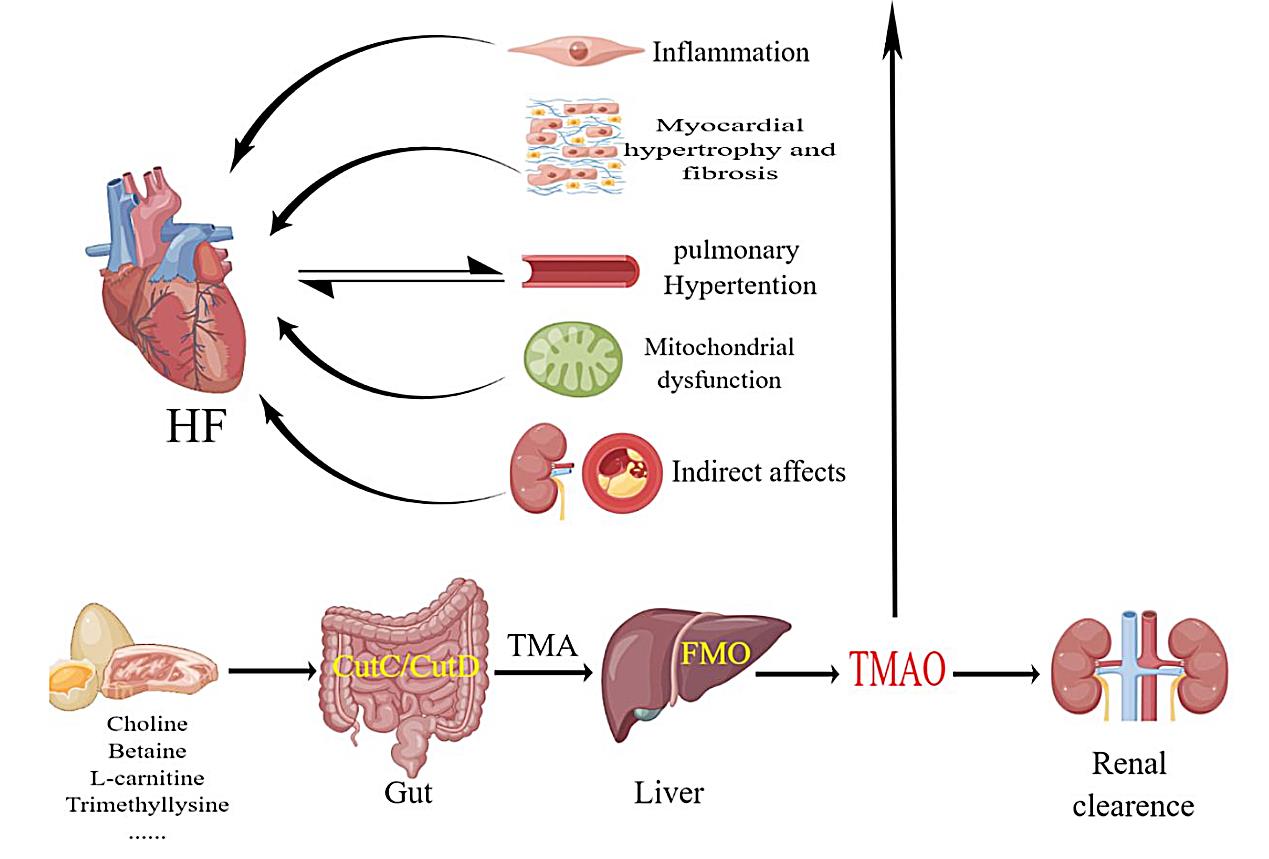

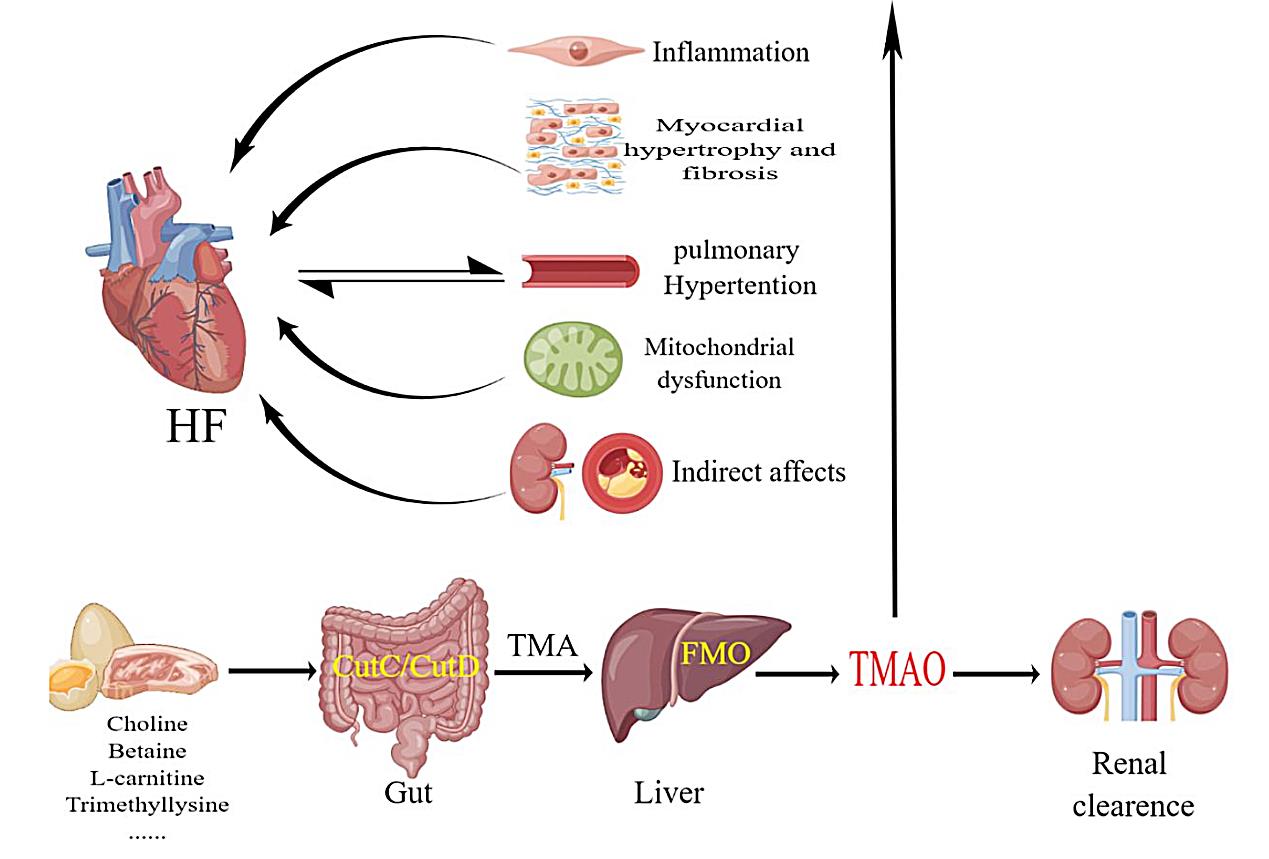

Red meat, eggs, fish, and dairy products are rich in choline, betaine,

L-carnitine, phosphatidylcholine, and glycerophosphocholine [22, 23]. These

substances are transformed into TMAO through the action of specific gut microbial

enzyme systems present in the human intestine. For instance, enzymes like choline

TMA lyase (CutC/D), carnitine monooxygenase (CntA/B), betaine reductase, and TMAO

reduction enzymes can convert phosphatidylcholine and L-carnitine into TMA [24, 25]. TMA enters the bloodstream through the portal vein and is oxidized in the

liver by flavin-containing monooxygenases (FMOs) to form TMAO. In particular,

humans convert TMA to TMAO primarily through flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3). Studies have found that

omnivores, those who consume both meat and plant foods, have higher plasma TMAO

levels than vegans or vegetarians [13]. Another study showed that people with a

long-term intake of high-fat red meat had higher plasma TMAO levels compared to

those on a low-fat or Mediterranean diet [23]. Interestingly, fish flesh, which

contains TMAO, has the most significant impact on circulating TMAO levels

[26, 27]. Consumption of fish results in a notable increase in TMAO concentrations

in both blood and urine. It is important to note that the increase in circulating

TMAO after choline supplementation through eggs shows considerable individual

variation, suggesting strong interactions between diet and host. A high-fat diet

is another factor affecting TMAO concentrations. In healthy men, four consecutive

weeks of excessive intake of calories with a high fat content (55%) (

The dietary-gut microbiota-liver axis forms the biosynthetic pathway for TMAO.

Compounds containing a trimethylamine group such as choline, phosphatidylcholine,

carnitine,

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Humans consume foods rich in choline and carnitine, which are broken down in the intestines by CutC/CutD to produce TMA. FMO in the liver decomposes TMA into TMAO, which acts on various systems of the body and is eventually excreted by the kidneys. TMAO induces inflammation, fibrosis of cardiomyocytes, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and mitochondrial dysfunction, which can lead to heart failure. FMOs, flavin-containing monooxygenases; CutC/CutD, choline trimethylamine-lyase system; TMA, trimethylamine; TMAO, trimethylamine-N-oxide; FMO, flavinemon-ooxygenase; HF, heart failure.

TMAO was first isolated by researchers in 2013, and since then a growing body of evidence has found that TMAO plays an important role in diseases such as diabetes, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, and neurological disorders [32, 33, 34]. TMAO was found to induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in HEK293 cell lines through activation of protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) and forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1), which may lead to insulin resistance, thereby increasing the risk of hyperglycemia, metabolic dysfunction, and type 2 diabetes in individuals with higher levels of TMAO [35]. The effects of TMAO on glucose metabolism have been demonstrated in an animal study. TMAO affects the insulin signaling pathway in the liver, which in turn affects glucose tolerance and increases the synthesis of pro-inflammatory mediators in adipose tissue [36]. There is also evidence that TMAO participates in multiple inflammatory pathways, including Accumulation of lipid deposits in blood vessels and tissues, leading to fatty liver, visceral obesity, and atherosclerosis, and subsequently causing metabolic syndrome [37]. Changes induced by TMAO have also been detected in neurons. In vitro models, TMAO generated endoplasmic reticulum stress in hippocampal neurons by activating the PERK pathway, causing alterations in synapse and neuronal plasticity [38]. Animal studies have also shown that TMAO increases clopidogrel resistance to platelets, demonstrating that TMAO can function as a platelet activator [39].

Furthermore, although 95% of TMAO is normally excreted by the kidneys, chronic

kidney disease impairs renal filtration. A prospective study evaluating

parameters such as glomerular filtration rate, C-reactive protein, and cystatin C

found that TMAO was an indicator of survival in patients with chronic kidney

disease [40]. TMAO has been reported to accelerate the progression of diabetic

nephropathy by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome and promoting the release of

IL-1

Recent studies have shown that the gut microbiota and its metabolites, particularly TMAO, play a significant role in the pathophysiology of HF. TMAO has been implicated in the progression of HF and is associated with poor prognosis in patients with this condition. Current research mainly involves the following mechanisms.

Intramucosal acidosis, reduced ejection fraction, bowel wall thickening and

edema have been reported in about 50% of heart failure patients. It is well

known that activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in patients with heart failure is a

compensatory response to the reduction in cardiac output and the increase in

filling pressures, but ultimately leads to multiorgan underperfusion and

circulatory stagnation. In this regard, right heart failure induces intestinal

edema, leading to intestinal barrier dysfunction with intestinal leakage of

microorganisms and/or their products into the circulation (the “leaky gut”

hypothesis of hypertension), as well as low-grade inflammation and associated

immune responses [45, 46, 47]. A variety of inflammatory mediators have been found to

be elevated in hypertensive patients, including transforming growth

factor-

By activating the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-

NLRP3 inflammasome is a multiprotein complex that plays a central role in

inflammatory and autoimmune responses in the body. NLRP3 inflammasome is one of

the potential intracellular inflammatory mediators activated during HF. NLRP3

inflammasome promotes the disruption of endothelial tight junctions, leading to

endothelial dysfunction and may induce ventricular arrhythmias in patients with

atrial fibrillation with a preserved ejection fraction [55, 56]. Conversely,

inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome can reduce cellular inflammation, hypertrophy,

fibrosis, and reverse pathological cardiac remodeling induced by pressure

overload [57]. TMAO activates NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles via the

SIRT3-SOD2-mtROS (sirtuin-3-superoxide dismutase 2-mitochondrial reactive oxygen

species) pathway and induces vascular inflammation [58]. TMAO-induced activation

of NLRP3 inflammasomes was found to be associated with redox regulation and

lysosomal dysfunction. In animal experiments, direct injection of TMAO into mice

with partially ligated carotid arteries resulted in the formation of NLRP3

inflammasomes and increased IL-1

TMAO also exacerbates HF by directly binding to and activating the PERK, which leads to an apoptotic inflammatory response and the production of reactive oxygen species, resulting in vascular damage and cardiac remodeling, which indirectly leads to hypertension [59]. Animal experiments and clinical studies suggest that the activation of TMAO and PERK is closely related to the onset and progression of cardiovascular diseases. Understanding the interaction between TMAO and PERK may provide clues for the development of new drugs for the treatment of HF.

Makrecka-Kuka et al. [60] found that feeding mice 120 mg/kg of TMAO for

eight weeks can affect the oxidation of pyruvate and fatty acids, leading to

mitochondrial dysfunction and eventually to ventricular remodeling and the

development of HF. Additionally, Savi et al. [61] consider that TMAO

might impact myocardial contractile function through mitochondrial dysfunction.

Recent studies involving 200 participants with extreme dietary habits, healthy

and unhealthy, showed that the metabolism of the TMAO precursor substance TMA is

potentially linked to mitochondrial dynamics and mitochondrial DNA. It promotes

the accumulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS) by inhibiting

sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) expression and superoxide dismutase 2 activity and activates

NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles to produce IL-1

Another mechanism by which TMAO leads to HF is by inducing aortic stiffness, increasing systolic pressure, and causing a hypercoagulable state [63, 64]. Besides affecting coagulation mechanisms, TMAO can also promote the formation of foam cells, induce inflammatory responses, and reduce reverse cholesterol transport, thus promoting atherosclerosis. Although TMAO does not directly cause HF, its impact on blood coagulation states and processes like atherosclerosis indirectly increases the risk of HF, highlighting its significant role in cardiovascular diseases.

Upon evaluating several studies [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21], TMAO has been considered helpful in predicting HF or adverse cardiovascular events. As suggested by the Heianza research group in a paper, TMAO has been identified as a predictor of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease [65]. Moreover, several cohort studies in Europe and the United States have indicated that plasma TMAO concentrations can predict death due to acute myocardial infarction, stroke, or other causes. Independent research has also found that TMAO can be an important predictive factor for HF.

The BIOSTAT-CHF study [44] first explored the reaction of TMAO levels to treatment and discovered that guideline-based CHF drugs may not impact the circulating levels of TMAO. Additionally, patients with lower levels of TMAO had higher survival rates at follow-up. However, patients with persistently rising TMAO levels before and after treatment had a higher mortality rate. Elevated TMAO levels have been shown to correlate with adverse diastolic indices, such as an increased left atrial volume index. A clinical trial examining the effects of TMAO on HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) found that TMAO levels could predict adverse cardiovascular events in patients with HFrEF [66]. Moreover, in a study focusing on HFpEF, TMAO levels proved useful for risk stratification, suggesting that combining BNP with TMAO could provide additional prognostic value for patients with HFpEF [67]. In the future, TMAO may serve as a tool for prognostic prediction and early intervention in HF patients, potentially enhancing patient survival rates.

Diets rich in choline, carnitine, saturated fatty acids, and animal protein have been shown to cause poor development of gut microbiota and elevated plasma levels of TMAO [68]. Levitan et al. [69] conducted a retrospective cohort study of 3215 postmenopausal women and showed that patients adhering to the Mediterranean diet had lower urinary TMAO level. Kerley and Nguyen et al. [70, 71] found that a plant-based diet rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains may be beneficial for HF patients. Other studies have indicated that reducing the intake of red meat and fats and increasing dietary fiber can decrease plasma TMAO levels and mitigate cardiac remodeling [72, 73, 74]. An analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) has shown that the Mediterranean diet reduces the incidence of HF by up to 70%, suggesting that dietary modifications may reduce plasma TMAO levels [75]. In conclusion, dietary control is an economical and convenient way to prevent and treat HF by positively influencing the gut microbiota.

Antibiotics can influence diseases caused by microbes by altering the abundance

or composition of gut microbiota. Research has shown that antibiotics can

suppress the production of TMAO by gut microbiota, thereby reducing the risk of

HF progression. Conraads and colleagues found that polymyxin B and tobramycin can

reduce the levels of IL-1

Probiotics play a crucial role in altering the composition of the gut

microbiome, maintaining gut homeostasis in the host, and improving human health.

Increasing evidence suggests that probiotics may participate in modulating

cardiac remodeling in patients with HF. Awoyemi A et al. [78] found that

Saccharomyces boulardii led to an improvement in gut microbiota

composition, as well as an improvement in the left ventricular ejection fraction

[79]. A 3-month randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Costanza and

colleagues revealed that chronic HF patients treated with probiotics exhibited

significant reductions in inflammatory markers and improvements in cardiac

contractility compared to the control group [80]. Recent studies have indicated

that probiotics can decrease TMAO levels, suggesting that their cardioprotective

effects might be achieved in part by reducing circulating TMAO [81, 82].

Clinically, the intake of prebiotics has also been proven to be beneficial for

patients with cardiovascular diseases. For example, one study showed that oat

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) involves the transfer of functional microbiota from healthy human feces into the gastrointestinal tract of a patient to re-establish a normally functioning gut microbiota for the treatment of intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. FMT has been shown to alleviate myocarditis in a mouse model of experimental autoimmune myocarditis [85]. Transplantation of gut microbiota from healthy rats to hypertensive rats reduced blood pressure [86]. A study tested the FMT strategy by transplanting feces from healthy blood donors to patients with metabolic syndrome affecting the heart. The results found that patients with higher bacterial diversity improved peripheral insulin sensitivity [87]. Du et al. [87] performed 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing on rat fecal samples and showed that TMA levels in feces as well as TMAO levels in the ipsilateral brain and serum were elevated after traumatic brain injury, whereas FMT reduced TMA levels in feces as well as TMAO levels in the ipsilateral brain and serum [88].

Recent studies have shown that more species of pathogenic microorganisms, such as Candida, Campylobacter, Shigella, and Yersinia, can be detected in the feces of patients with HF, and that these microorganisms are associated with the severity of HF [89]. In a randomized double-blind controlled trial involving 20 patients with metabolic syndrome, a single fecal transplant from a vegetarian donor was found to alter the structure of the gut microbiome in some of the patients, but did not affect parameters associated with vasculitis [90]. However, it is currently unclear whether FMT can improve symptoms by reducing TMAO, and further clinical research is needed to answer this question.

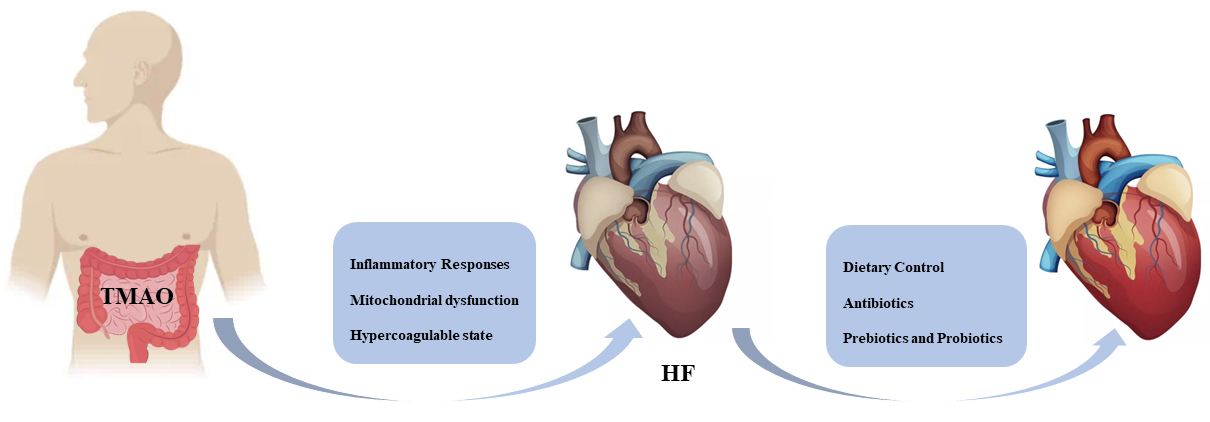

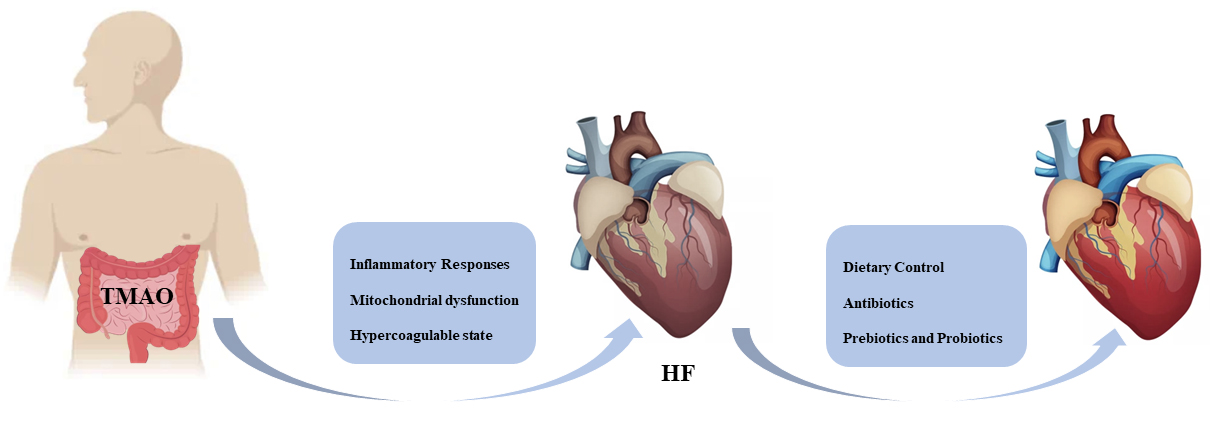

In recent years, multiple studies have confirmed the correlation between cardiovascular diseases and gut microbiota as well as the metabolic products of gut microbiota. TMAO, as one of these metabolites, has garnered considerable attention from scholars. Several studies have indicated that TMAO primarily triggers HF through promoting inflammatory responses and mitochondrial dysfunction. However, these studies are fundamentally correlational, and it remains challenging to discern whether changes in TMAO levels are a consequence or cause of the disease. Therapeutically, since TMAO is a metabolite derived from gut microbiota, levels can potentially be reduced through interventions such as diet, fecal transplantation, prebiotics, probiotics, and antibiotics (Fig. 2). Yet, clear empirical evidence is still lacking on whether lowering TMAO levels is effective for the treatment and prognosis of HF. Hence, further prospective studies are necessary to link TMAO to disease onset, progression, and therapeutic measures. Additionally, the role of TMAO in diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, and diabetes should not be overlooked. Meanwhile, beyond TMAO, other gut microbiota metabolites may also possess potential research value. In the future, the modulation of gut microbiota and its metabolic processes may profoundly affect patient survival and prognosis.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.TMAO precipitates HF by promoting an inflammatory response, mitochondrial dysfunction, and hypercoagulability state. People can expect to improve heart function through dietary control, judicious use of antibiotics, and taking prebiotics and probiotics. HF, heart failure; TMAO, trimethylamine N-oxide.

TMAO promotes the progression of HF through inflammatory response, mitochondrial dysfunction and other mechanisms. It may become a new target for HF treatment in the future.

LJ provided manuscript ideas, HZ and QX were involved in writing the manuscript, HH and CZ revised the manuscript, HZ, QX, HH and CZ were involved in conceptualizing the structure of the manuscript, and SX and HT were involved in drawing the figures and submitting the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Figures were created with the aid of Figdraw (https://www.figdraw.com/#/).

This review was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (Grant no. LGF21H020006), Pioneer innovation team of Jiaxing Institute of atherosclerotic diseases (Grant no. XFCX–DMYH), The Key Medicine Disciplines Co- construction Project of Jiaxing Municipal (Grant no. 2019- ss- xxgbx), Program of the First Hospital of Jiaxing (Grant No. 2021-YA-011), Jiaxing Key Laboratory of arteriosclerotic diseases (Grant no. 2020-dmzdsys), Science and Technology Program of Jiaxing (Grant No.2022AD30058).

No conflict of interest in author contributions, acknowledgements, funding sources.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.