1 Department of Cardiology, Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust, WR5 1DD Worcester, UK

2 Department of Cardiology, Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, WV10 0QP Wolverhampton, UK

3 Department of Cardiology, University Hospital Birmingham NHS Trust, B15 2GW Birmingham, UK

Abstract

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) epitomises a genetic anomaly hallmarked by a relentless fibro-fatty transmogrification of cardiac myocytes. Initially typified as a right ventricular-centric disease, contemporary observations elucidate a frequent occurrence of biventricular and left-dominant presentations. The diagnostic labyrinth of ACM emerges from its clinical and imaging properties, often indistinguishable from other cardiomyopathies. Precision in diagnosis, however, is paramount and unlocks the potential for early therapeutic interventions and vital cascade screening for at-risk individuals. Adherence to the criteria established by the 2010 task force remains the cornerstone of ACM diagnosis, demanding a multifaceted assessment incorporating electrophysiological, imaging, genetic, and histological data. Reflecting the evolution of our understanding, these criteria have undergone several revisions to encapsulate the expanding spectrum of ACM phenotypes. This review seeks to crystallise the genetic foundation of ACM, delineate its clinical and radiographic manifestations, and offer an analytical perspective on the current diagnostic criteria. By synthesising these elements, we aim to furnish practitioners with a strategic, evidence-based algorithm to accurately diagnose ACM, thereby optimising patient management and mitigating the intricate challenges of this multifaceted disorder.

Keywords

- arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy

- desmosomal genes

- cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

- electrophysiology

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) is a genetic disorder affecting the myocardium. Initially, it was termed arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) as it was thought to predominantly affect the right ventricle (RV) with predisposition to fatal arrythmias. This is characterised histologically by progressive replacement of myocytes by fibrous tissue, with preponderance in the RV free wall in a region known as the triangle of dysplasia (between anterior part of pulmonary infundibulum, the infero-posterior wall and RV apex) [1]. These lesions typically extend from epicardium to endocardium. In light of developments in imaging, genotyping and our overall understanding of the disease, there is emerging recognition that this disease process is not exclusive to RV with left ventricular (LV) and biventricular ACM being recognised as phenotypic variants. The change in nomenclature from ARVC to ACM is a reflection of our improved understanding of this disease.

Estimated prevalence of ACM is between 1:2500 to 1:5000 but this is likely to be an underestimate as it does not include biventricular or LV dominant variants [2]. As sudden cardiac death (SCD) can be an initial manifestation of ACM, the true prevalence is likely to be higher than reported. The variation in the presentation frequently means that alternate differentials of myocarditis or dilated cardiomyopathy are initially considered before ACM is identified, often at the point of detailed imaging acquired through the use of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).

In this review, we aim to provide a succinct overview of genetics and presentation with respect to electrophysiological characteristics. In recent years, there have been several changes and updates to the diagnostic criteria for ACM which we will summarise along with pertinent updates in imaging and management.

ACM is a hereditary cardiovascular disorder with complex genetic underpinning. Understanding the genetic basis of ACM is crucial for accurate diagnosis, risk stratification and management of these patients.

In 2000, a study by McKoy et al. [3] in patients with Naxos disease revealed genetic mutations in a gene (Junctional Plakoglobin (JUP)) that encodes for plakoglobin (a protein that is a component of desmosomes). Desmosomes are specialised structures that facilitate cell-to-cell adhesion and are crucial for maintaining the structural integrity of cardiac tissue. Mutations in desmosomal genes disrupt these adhesion complexes, compromising the mechanical strength of myocardial cells which eventually leads to cell death and fibrofatty replacement [3]. This discovery led to focused efforts to identify other genes that code for desmosomal proteins and this identified mutations in the desmoplakin (DSP) gene, plakophilin-2 (PKP2), desmoglein-2 (DSG2) and desmocollin (DSC2) genes [4, 5, 6]. Non-desmosomal proteins have also been implicated in ACM, including those encoding for adherens junction proteins, ion channels and their modulators and cytoskeleton structures [7].

To date, there are 15 genes that have been implicated in pathogenesis and include both desmosomal genes (PKP2, DSP, DSC2, DSG2 and JUP) and nondesmosomal genes (transmembrane protein 43 (TMEM43), desmin (DES), titin (TTN), phospholamban (PLN), and ryanodine receptor-2 (RYR2)) [7, 8]. Of these 15 genes, 8 genes (PKP2, DSP, DSG2, DSC2, JUP, TMEM43, PLN, and DES) have at least moderate evidence to be considered ACM causative [9]. It is important to note that many have no detectable pathological variants; these patients may reflect unknown pathological variants, or may harbour mutations in genes not currently associated with ACM [10].

Up to 50% of ACM cases are thought to be caused by mutations affecting desmosomal proteins [8], and of these mutations, the PKP2, encoding Plakophilin-2, is implicated in up to 20–46% of cases [7]. Plakophilin-2 plays a critical role in stabilizing desmosomes, and its mutations contribute to the breakdown of these structures initiating the pathological changes observed in ACM. Mutations in DSP and DSG2 genes are thought to account for 10% of cases of ACM whilst mutations in DSC2 account for approximately 5% of cases. Mutations in JUP gene are thought to account for less than 1% of cases [7]. Desmosomal mutations tend to have an autosomal dominant (AD) inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance leading to an isolated cardiac phenotype with PKP2 mutations being mostly AD in inheritance and most likely to lead to conventional phenotype than other desmosomal mutations [1, 11]. In a study performed by Biernacka et al. [12], ACM patients with PKP2 mutations were less likely to present with LV involvement and heart failure symptoms and overall had a favourable prognosis compared to other mutations. Patients with DSP mutations present with variable phenotypes such as biventricular cardiomyopathy, or isolated LV arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy with Rigato et al. [13] presenting higher degree of LV involvement in patients with DSP mutations. DSP mutation phenotypes of ACM have also been associated with higher risk of ventricular arrythmias and SCD [14]. Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in JUP, DSP and DSC2 can lead to cardio-cutaneous syndromes such as Naxos and Carvajal syndromes [11].

Non-desmosomal genes contribute to development of ACM in several ways; TMEM43 gene encodes for a nuclear envelope protein and mutations in this gene have been associated with high penetrance and risk of SCD especially in young men [15]. DES genes encode for intermediate filament desmin and have been identified in patients with ACM (with right predominant or biventricular involvement). DES mutations have also been linked to dilated cardiomyopathies (DCM), suggesting an overlap syndrome [16]. TTN genes encode for sarcomeric protein titin and have been found in high proportion of patients with ACM (18%) [11].

Filamin C, an actin binding protein (encoded by FLNC gene) plays a vital role in anchoring membrane proteins to cytoskeleton, thereby contributing to sarcomere maintenance. Truncating mutations in FLNC have been linked with phenotypically left dominant ACM with high risk for sudden cardiac death [17]

Finally, given the hereditary component to the disease, family screening and genetic counselling forms an integral part of diagnosis. Indeed, family screening has been a component of the diagnostic criteria in all its iterations [18, 19, 20]. Current guidelines recommend that first-degree relatives undergo clinical evaluation every 1–3 years with 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), ambulatory ECG and imaging [21]. However, disease expression of ACM is variable even in the same family or those carrying the same pathogenic mutation, therefore, Muller et al. [22] recently undertook a study to determine if there are predictors of disease development among at-risk relatives. In this study, symptomatic relatives, those 20 to 30 years of age and those with one minor task force criteria had higher hazard for developing ACM. This may help clinicians risk stratify patients that may benefit from more frequent follow-up.

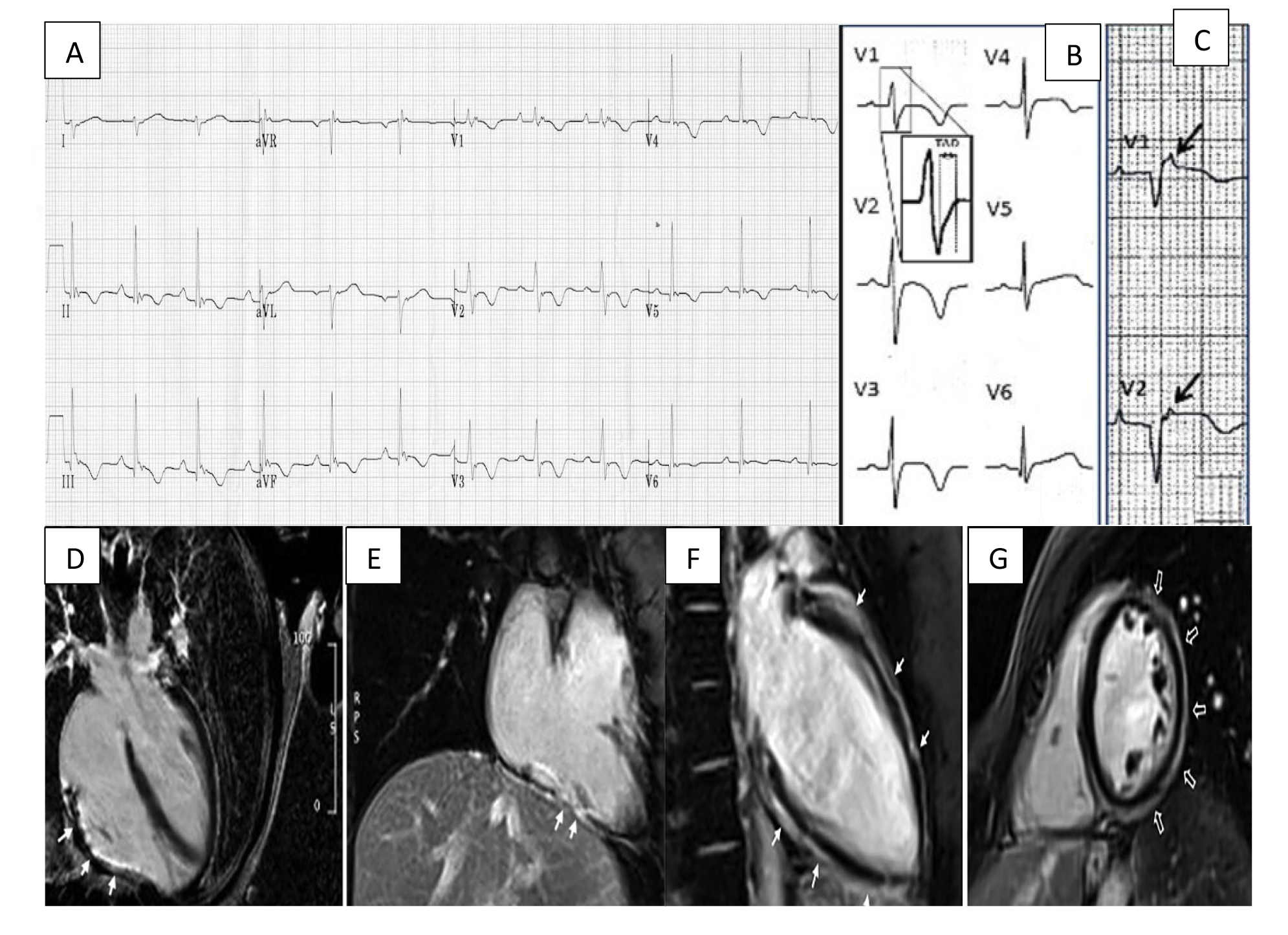

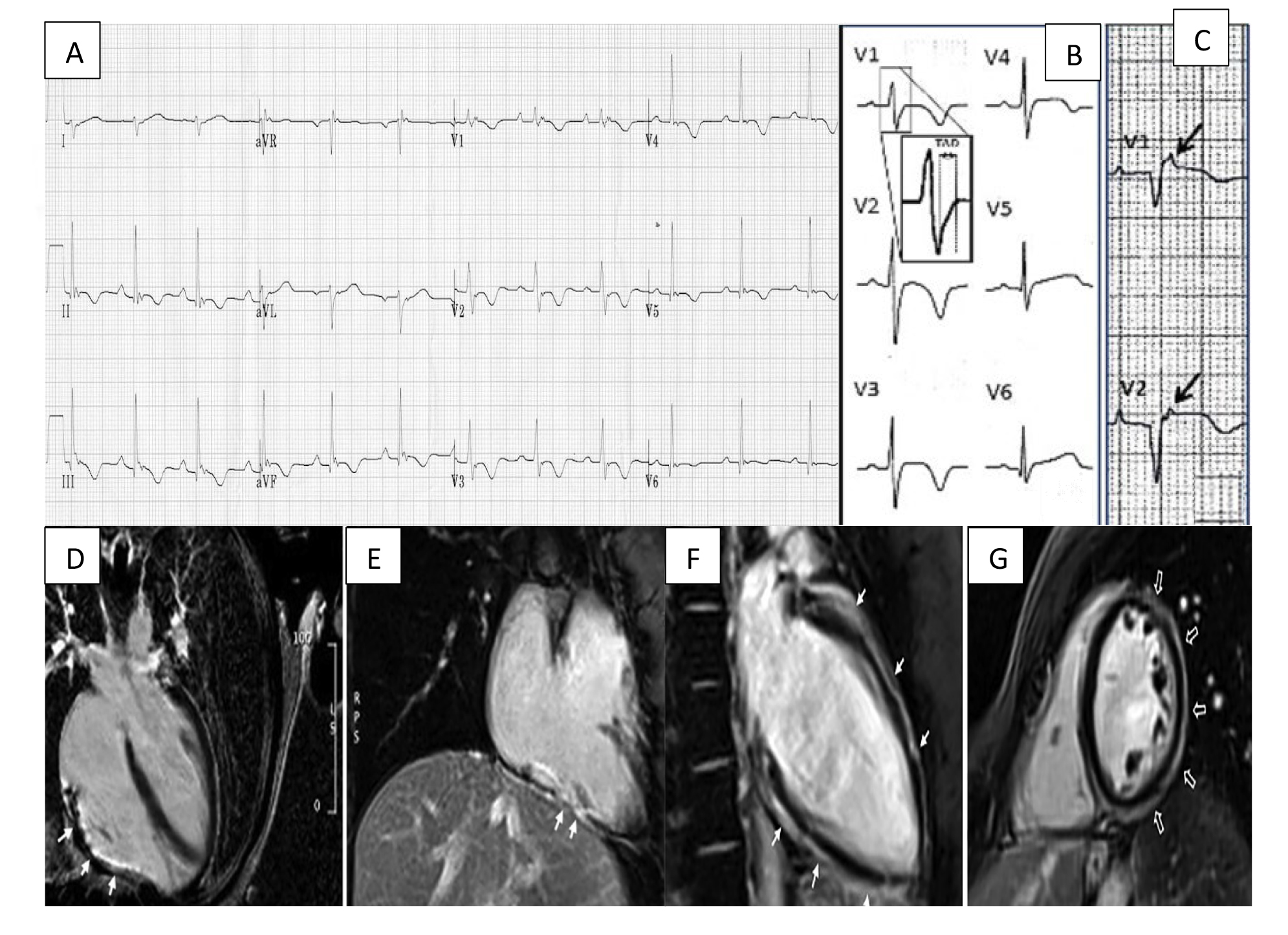

Understanding the electrophysiological perturbations implicated in ACM is essential for screening, diagnosis, risk stratification and guiding therapeutic interventions. The nature of structural changes within the myocardium modulates transmission of electrical signals and can result in conduction defects that may be visible on a standard 12-lead ECG (Fig. 1, Ref. [20]).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy findings electrocardiogram (ECG) and CMR. (A) ECG focusing on the precordial leads with characteristic T wave inversion in leads V2–V5 and an epsilon wave in V1. (B) Widening of the QRS with classical T wave inversion in leads V2–V4. A close-up view of the delayed S upstroke within the QRS is also indicated. (C) Arrows highlighting epsilon wave in V1–V2. (D) A long axis 4 chamber view CMR showing LGE/fibrous replacement of RV diaphragmatic free wall (indicated by the arrows). (E) Sagittal view CMR emphasising the fibrous replacement of the RV anterolateral wall. (F) CMR depicting subepicardial LGE of the LV extending from the base to apex segment in the sagittal view. (G) CMR image showing a post-contrast ‘ringlike’ pattern in the short axis view. CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle. Figure adapted with permission from (1) ECG Library. Life in the Fast Lane. https://litfl.com/ecg-library/. Accessed March 26, 2023. (2) Corrado et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: European Task Force consensus report. International Journal of Cardiology. 2024 Jan; 395: 131447. [20]

The most common ECG changes include:

Often, subtle ECG changes may not be visible on 12-lead surface ECG; therefore, this requires more sophisticated techniques for identification. Signal-averaged electrocardiogram (SAECG) is a non-invasive signal-processing technique to detect subtle abnormalities in the surface ECG. It can identify low-amplitude signals at the terminus of the QRS complex, referred to as ‘ventricular late potentials’. These represent delayed activation and predispose to re-entrant arrythmias. SAECG uses computerised averaging of ECG complexes during sinus rhythm to detect small amplitude signals which occur later than rapid ventricular activation. In the 2010 International Task Force (ITF) diagnostic criteria, the presence of late potentials on SAECG was considered a minor criterion for diagnosis based on studies supporting their increased sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of ACM [18, 23]. Interestingly, in the newer 2020 ‘Padua Criteria’, SAECG are not considered part of the diagnostic work up with the authors reporting low diagnostic accuracy [19].

Additionally, invasive electrophysiological studies (EPS) can detect and provide direct visualisation and assessment of arrhythmogenic substrate. It is noted that identifying the genotype can help confer the phenotype relating to the expected location of fibrosis, e.g., variants of the lamin A/C genotype manifest substrate foci within subaortic, mid and basalseptal regions [24].

Changes that can be observed on EPS include:

Mapping the heart’s electrical activity in three dimensions allows identification of fixed lines of conduction block associated with reentrant circuits. This approach allows construction of a 3D map that can help plan catheter ablation approaches [26]. Further work mediated through simultaneous endocardial and epicardial delineation allowed for construction of 3D structures derived from both small and large substrate areas [27].

Diagnosis of ACM can be challenging as it mimics other cardiomyopathies in presentation and imaging. However, accurate diagnosis is vital as it allows early treatment initiation and cascade screening. The 2010 revised International Task Force (ITF) criteria provided an update to the Original Task Force guidelines in the diagnosis of ACM [18]. It is a scoring system containing six disease characteristics: structural alterations on imaging, tissue characterisation, repolarisation abnormalities, depolarisation abnormalities, arrhythmia and family history. In each category, there is major, minor or no criteria that can be fulfilled. A diagnosis is confirmed if 2 major, or 1 major and 2 minor, or 4 minor criteria are fulfilled from different disease categories. A criticism of the 2010 ITF criteria has been that it focused on RV phenotypic manifestations without recognising cohorts with biventricular or LV dominant variants. For instance, the major criteria for structural alteration exclusively describes RV regional abnormalities with no reference to LV structural abnormalities. Although the 2010 ITF criteria increased diagnostic yield of ACM, it cannot be applied to ACM with LV involvement [28].

In 2020, the International Expert consensus document (‘the Padua Criteria’) provided an update to diagnostic criteria to address some of the limitations in the 2010 ITF criteria [19]. This newer classification categorises ACM into three phenotypic variants: the dominant-right, biventricular and dominant-left. Although differences between these criteria have been described well elsewhere in the literature, it is important to note some key differences [29]. As endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) is invasive with potentially serious sequelae, there is less emphasis on EMB for tissue characterisation. In the 2020 ITF criteria, this is reserved for probands with negative genotyping where histology can exclude phenocopies such as cardiac sarcoidosis. Recent advancements in use of electroanatomic voltage mapping (EMV) guided EMB has been proven to be a promising tool for targeted EMB, thereby improving diagnostic yield and reducing complication rates and should be considered when EMB is being explored [30]. There is also more emphasis on the use of contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CE-CMR) for morphological assessment and tissue characterisation. With respect to LV involvement, there is addition of new repolarisation, depolarisation and ventricular arrythmia criteria for this subgroup. Family history and genetics remain unchanged between the two criteria.

The implementation of ‘Padua criteria’ improved diagnostic yield of ACM

particularly in relation to LV involvement [29]. A refinement to the 2020

criteria was recently published this year (2024 European Task Force consensus

report) with changes to major criteria for diagnosis of arrhythmogenic left

ventricular cardiomyopathy (ALVC) based on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

(CMR), late-gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and ECG features (Table 1, Ref. [20]). A

‘ring-like’ pattern of LGE (subepicardial or midmyocardial involvement in

| Category | RV phenotype | LV phenotype |

| Morpho-functional ventricular abnormalities | Major | Minor |

| plus one of the following: | ||

| or | ||

| Minor | ||

| Structural alterations | Major | Major |

| Minor | Minor | |

| Repolarization abnormalities | Major | Minor |

| Minor | ||

| Depolarization and conduction abnormalities | Minor | Major |

| Arrhythmias | Major | Minor |

| Minor | ||

| Family history | Major | |

| Minor | ||

ACM, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy; LBBB, left bundle-branch block; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricle; RBBB, right bundle-branch block; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract.

Table adapted from Corrado et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: European Task Force consensus report. Int J Cardiol. 2024 Jan doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.131447. [20] Permission obtained via Creative Commons CC-BY license.

Non-invasive imaging plays a key role in diagnosis. Both transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and CMR feature in the 2010 ITF criteria and the 2020 ‘Padua Criteria’ for the diagnosis of ACM. Recently, computed tomography (CT) has also emerged as a robust tool in RV assessment [32].

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) remains the most widely available modality to evaluate patients with suspected ACM. Despite this, RV assessment can be challenging given its complex geometry and position as well as the fact that wall motion assessment can be subtle and subjective [11]. The RV has a crescentic shape and three distinct anatomical components, the inlet, body and outlet, which cannot be simultaneously imaged in a single 2D plane [33]. Furthermore, the shape of RV means it cannot be characterised using geometric assumptions unlike the LV. The RV is also preload dependent which can lead to dynamic variations in shape and size and limit reproducibility. Finally, RV is heavily trabeculated which can impede image analysis.

As per 2010 ITF criteria, the presence of wall motion abnormalities, RV dilatation and RV dysfunction is required for a diagnosis of ACM, with the degree of RVOT dilatation and RV fractional area change (FAC) determining distinction between major and minor criteria [18]. Developments in 3D echocardiography, strain imaging as well as tissue deformation imaging (TDI) can in theory improve evaluation especially in early stages. TDI is a doppler-based imaging technique that measures velocity of myocardial tissue motion thereby allowing quantitative assessment of ventricular function. TDI can be readily performed, is relatively independent of preload and has been shown to have good reproducibility in quantification of RV function [34]. Strain imaging measures deformation or strain of myocardial fibres during the cardiac cycle. Strain imaging offers insights into myocardial mechanics, allowing assessment of regional and global contractile function. In a study by Aneq et al. [35], the use of longitudinal strain by speckle tracking was shown to be useful in assessment of regional and global myocardial function of both RV and LV.

CMR has become the gold standard for adjunct imaging evaluation of patients suspected with ACM and has an additional role in serial follow-up. CMR has the ability to provide detailed tissue characterisation including wall thickness, mass, volumes, as well as regional motion, myocardial adipose content and oedema with high temporal and spatial resolution [11]. As per 2010 ITF criteria, regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia or dyssynchronous RV contraction are required to fulfil either major or minor diagnostic criteria [18]. In the updated 2020 ‘Padua Criteria’, LV regional wall abnormalities and systolic dysfunction form part of the morpho-functional diagnostic assessment [19].

CMR can detect fibrofatty infiltration of the RV; however, this has also been described in obese patients without ACM (typically in a subepicardial distribution) and therefore is a non-specific finding [36]. As per 2010 ITF criteria, fat infiltration of the myocardium counts as a diagnostic criterion if found on EMB [37]. As discussed earlier, tissue characterisation via LGE in CMR can highlight areas of myocardial scarring and fibrosis and is well described in cases of ACM (in both RV and LV phenotypes) [38]. However, LGE in itself is a non-specific finding and may not differentiate ACM from other non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies (such as myocarditis, sarcoidosis and neuromuscular dystrophies) [36]. However the extent and distribution of LGE can help differentiate between LV phenotypes of ACM and DCM, with DCM patients typically showing subepicardial or mid-myocardial LGE pattern [39]. Interestingly in the original 2010 ITF criteria, LGE was not included in the diagnostic criterion, but has been included in the 2020 ‘Padua criteria’. The 2020 ‘Padua criteria’ acknowledged that at least one morpho-functional or structural RV or LV criterion (either major or minor) must be demonstrated for a diagnosis of an ACM phenotype variant. This change has augmented the importance of cardiac imaging, and specifically of CMR given its capability of detailed morpho-functional and tissue characterisation of both RV and LV [40].

While CMR is a valuable tool in diagnosis of ACM, it is important to be aware of some limitations of the modality. Inter-observer variability in the evaluation of RV regional wall motion remains a limitation. Along with this, misinterpretation of normal variants of RV wall motion remains common. Finally, the lack of standardised protocols also limits reproducibility.

Cardiac CT with its excellent spatial resolution (0.5–0.625 mm) allows for delineation of myocardium from fat, with a high degree of intramyocardial fat being demonstrated in patients with ACM [41]. The use of multidetector CT (MDCT) has previously been validated in measurements of ventricular volumes in patients with congenital heart disease when compared to CMR [42]. This indicates potential capability in measurement of RV volumes. A recent study by Venlet et al. [43] showed that tissue heterogeneity on CT enabled differentiation between ACM and control individuals (sensitivity: 100%; specificity: 82%). Interestingly, this study also showed utility in identifying pro-arrhythmic substrate. Though not part of the typical diagnostic imaging work-up for ACM, it has been suggested to be of particular use for accurate measurement of ventricular volumes and identification of myocardial fat infiltration. CT may also be relevant in diagnosis of ACM when CMR is contraindicated (such as claustrophobia, or non CMR conditional cardiac device) or when results are inconclusive [44].

At present there is no cure for ACM; instead, management is focused on risk

stratification and minimising disease sequelae. Both 2017 American College of

Cardiology (ACC) and 2022 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines

recognise the importance of avoiding high-intensity exercise to limit disease

progression and risk of ventricular arrhythmias [45, 46]. This recommendation

extends to genetic carriers even in the absence of overt disease phenotype [47].

However, one of the challenges has been defining exercise intensity and

translating this into clinical practice. Metabolic equivalents (METs) are a

standardised way to quantify exercise intensity and high-intensity exercise is

considered to require

Medical therapy can be categorised into management of (a) ventricular dysfunction and (b) ventricular dysrhythmias. There is a lack of robust evidence to guide management of ACM related right ventricular impairment. ACE-inhibitors, beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists and diuretic therapy have a class IIa recommendation in 2019 Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) guidelines for symptomatic RV dysfunction [21]. In animal studies, preload reducing therapy (via furosemide and nitrates) abrogated development of RV enlargement and induction of ventricular tachycardia [54]. Therefore, 2019 HRS guidelines have a class IIb recommendation to consider using isosorbide dinitrate in symptomatic individuals [21]. Beta-blockers are mainstay of treatment for arrythmia management as they can suppress pro-arrhythmic tendency and promote ventricular remodelling. As patients with ACM tend to be younger, sotalol is favoured instead of amiodarone as it has fewer extracardiac side effects. Ventricular arrythmias or recurrent implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shocks can be challenging for both the patient and clinician. A case series of eight patients demonstrated that flecainide, in combination with a beta-blocker, could be feasible in refractory ventricular arrhythmia [55]. A more recent observational study of 100 patients confirmed that flecainide, in combination with a beta-blocker, decreased premature ventricular contraction (PVC) and VT inducibility during programmed ventricular stimulation [56]. Flecainide use can be limited by LV ejection fraction and other agents such as mexiletine, a class 1b agent, have been used, but currently, there is absence of high quality data in this area. Catheter ablation is an alternative option for recurrent ventricular arrythmia but success is limited by multifocal substrate and potential need for epicardial approach [57]. However, a recent series by Santangeli et al. [58] showed that catheter ablation, in the absence of ICD, may have some promise. In this study 32 patients who declined ICD underwent endocardial and/or epicardial catheter ablation. After median follow up at 46 months there were no deaths and 26/32 (81%) were free from documented or symptomatic VT. Although this does not provide sufficient evidence to change routine practice it does highlight that catheter ablation may have feasibility as stand-alone therapy in select patients.

SCD is a fatal disease sequelae that is preventable through ICD. Although the device procedure has associated risks (such as infection, inappropriate shocks, repeat procedures and psychological trauma from shocks) the alternative is malignant arrhythmia and potential SCD. In patients who have suffered a cardiac arrest (due to malignant arrythmia) or have hemodynamic instability with VT, this is a straightforward decision as all major guidelines have a class 1 indication for ICD [21, 45, 46]. Selection of optimal candidates for primary prevention ICD, however, has proven difficult with no universally agreed risk stratification tool. Recently, Cadrin-Tourigny et al. [59] was able to develop a risk stratification score (https://arvcrisk.com/) using multinational registries comprising of 528 patients with confirmed ARVC. This model was able to predict the incidence of ventricular arrythmia with optimism-corrected C-index of 0.77 (95% CI 0.73–0.81). When compared to the 2015 International Task Force Consensus (ITFC) statement for treatment of ACM, this new model was able to provide the same level of protection with 20.3% fewer ICD implants [60]. It is noteworthy that in the prediction tool by Cadrin-Tourigny et al. [59] nearly half of the patients had PKP2 pathogenic mutation and more than 90% of the participants were of Caucasian ethnicity, which is not entirely reflective of the prevalence of this disease. In patients suitable for ICD therapy, the efficacy and safety of transvenous versus subcutaneous ICD has not been fully explored. In a recent analysis of matched subcutaneous versus transvenous ICD recipients, the subcutaneous group had more inappropriate shocks whilst the transvenous group had higher procedural complications [61]. Another important consideration around subcutaneous ICD is their inability to perform anti-tachycardia pacing (ATP) which can often terminate arrhythmias painlessly and avoid need for subsequent shocks.

As LV predominant ACM constitutes a smaller cohort of patients, the management

of this subtype is less well defined. It can commonly be misdiagnosed as other

cardiac muscle disorders leading to delay in treatment initiation. Management of

LV impairment in ALVC is with guideline-directed medical therapy based on

ejection fraction [62]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, beta-blocker,

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist and SGLT2 inhibitors are referred to as the

‘four pillars’ of medical management for heart failure with reduced ejection

fraction (ejection fraction

The recent scrutiny and updates to diagnostic parameters meant that our inclusion criteria has changed redefining the nature of ACM. This improved phenotypic understanding of ACM provides several avenues that require future consideration including risk stratification (for the biventricular and LV phenotypes), earlier detection and pharmacological therapies to target underlying disease mechanism.

Earlier detection and diagnosis is a challenge as most patients are identified

as part of a cascade screening process or after life threatening arrythmia.

Although CMR provides excellent tissue characterisation and aids diagnosis, it is

challenging to decide who should undergo this investigation as it is not

universally accessible and can be expensive. One option to navigate the latter

issue would be the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning into

CMR analysis to enhance speed and accuracy of image interpretation and risk

assessment [64]. Another benefit of CMR is the ability to detect myocardial scar.

LV scar burden has been noted to be a predictor of arrhythmogenesis and ICD

therapy in observational studies [65]. In a recent study by Gutman et

al. [66], 452 patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy and LV ejection

fraction

Given the genetic basis for ACM, there is an appreciation that gene therapy may serve as a potential option for treatment. A mouse model was generated with the PKP2 mutation to replicate the ACM features [67]. Adeno-associated viral therapy containing the corrected gene variant AAV-PKP2 was found to prevent desmosomal pathological deficits. Other successful endpoints including resolution of CMR changes and length of survival were associated with AAV-PKP2 gene therapy.

The role of cytokines, particularly TGF

In relation to symptom management, bilateral cardiac sympathetic denervation (BCSD) has been used in the context of refractory ventricular arrythmia for its antiarrhythmic effect [71]. There is emerging evidence from small studies that this approach can be used in the context of ACM to reduce ICD shocks or sustained VT [72]. At present, this is a treatment option only for refractory cases with failed conventional therapy and is available in a few select centres with unclear long-term benefit.

ACM is a hereditary cardiomyopathy that has deleterious consequences as it may present with life threatening arrythmias and sudden cardiac death. Over the last few years, our improved understanding of the disease process has enabled refinement of the diagnostic process, allowing categorisation based on phenotypic manifestations (RV, LV or bi-ventricular predominance). There have been several updates to the diagnostic criteria for ACM which we have summarised in this review, including discussion on imaging techniques and risk stratification. We have explored current therapeutic options including pharmacological management and device therapy. Although gene therapy and immune modulation show early promise, it is still in its infancy and formal trial data is lacking.

ZZ, NS and ND were involved in methodology, data synthesis, write up and review of the manuscript. PAP contributed to conceptualisation, review, and overall supervision as senior author. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.