1 Department of Vascular Surgery, Beijing Hospital, National Center of Gerontology, Institute of Geriatric Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 100010 Beijing, China

2 Graduate School of Peking Union Medical College, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 100010 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Background: Clinically useful predictors for risk stratification of

long-term survival may assist in selecting patients for endovascular abdominal

aortic aneurysm (EVAR) procedures. This study aimed to analyze the prognostic

significance of peroperative novel systemic inflammatory markers (SIMs), including the

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR),

hemoglobin-to-red cell distribution width ratio (HRR), systemic

immune-inflammatory index (SIII), and systemic inflammatory response index

(SIRI), for long-term mortality in EVAR. Methods: A

retrospective analysis was performed on 147 consecutive patients who underwent

their first EVAR procedure at the Department of Vascular Surgery, Beijing

Hospital. The patients were divided into the mortality group (n = 37) and the

survival group (n = 110). The receiver operating characteristic curves were used

to ascertain the threshold value demonstrating the most robust connection with

mortality. The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed between each SIM and

mortality. The relationship between SIMs and survival was investigated using

restricted cubic splines and multivariate Cox regression analysis.

Results: The study included 147 patients, with an average follow-up

duration of 34.28

Keywords

- novel systemic inflammatory markers

- hemoglobin-to-red-cell distribution width ratio

- abdominal aortic aneurysm

- all-cause mortality

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is characterized by an irreversible and progressive dilation of the abdominal aorta and often presents an 80% mortality rate after rupturing occurs [1, 2, 3]. Currently, the main surgical methods for treating an AAA are open surgical repair (OSR) and endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) [4]. Strong evidence from large randomized controlled trials has confirmed that EVAR is associated with reduced short-term mortality rates similar to mid- and long-term survival rates, although with higher reintervention rates during follow-up [5, 6, 7, 8]. Choosing a suitable surgical strategy is important to evaluate carefully the additional risk factors influencing prognosis, the patient’s anatomical characteristics, and preferences regarding follow-up [9, 10]. In this context, it is necessary to discover new, easily accessible, and generally applicable indicators for risk stratification in long-term survival conditions, thus, guiding treatment decisions [11].

Systemic chronic inflammation status is evaluated using novel systemic inflammatory markers (SIMs) derived from the whole blood cell count ratio. These markers include the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), hemoglobin-to-red cell distribution width ratio (HRR), systemic immune-inflammatory index (SIII), and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) [12, 13, 14]. These markers can more accurately indicate systemic inflammation for prognostic assessment [13]. Multiple studies have demonstrated a correlation between the novel SIMs and cardiovascular disease [15, 16], cancer prognosis [14, 17, 18, 19], and all-cause mortality [20]. The formation and development of the abdominal aorta are also closely related to the systemic inflammatory response [21, 22], and a cohort study has demonstrated a strong correlation between higher neutrophil count and abdominal aortic dissection [23]. Therefore, novel SIMs, which can serve as potential prognostic markers that are easy to obtain and widely used, are expected to be useful tools for identifying patients with poor survival outcomes after EVAR.

NLR has been proven to be associated with the perioperative morbidity of ruptured AAA and mortality after selective EVAR [24, 25]. However, the correlation between novel SIMs and the long-term survival rates after EVAR remains uncertain. Therefore, this study aimed to ascertain the accuracy of novel SIMs as prognostic indicators for predicting all-cause mortality in patients following EVAR.

A retrospective review of medical records showed 147 sequential individuals who underwent their first EVAR procedure at Beijing Hospital’s Vascular Surgery department between August 2016 and April 2023. The patients were mainly treated according to the criteria set by the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) [26, 27]. The surgeon made the final decision, considering the patient’s health characteristics and economic conditions.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients diagnosed with AAA by computed tomography angiography (CTA), digital subtraction angiography (DSA), or ultrasound; (2) patients undergoing EVAR for the first time; (3) patients with complete perioperative and follow-up data; (4) patients who have provided informed consent and agreed to the intervention, including being told about other choices. The exclusion criteria include the following patients: (1) those who received conservative treatment, open surgical repair, or have presented as emergency cases; (2) those who have primary or secondary infectious AAA, abdominal aortic stent infection; (3) those who had symptomatic or ruptured AAA; (4) those who had congenital diseases: Marfan syndrome, etc.; (5) those who had an endoleak after endovascular treatment. This study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board.

After a detailed assessment and personalized treatment strategy, all patients underwent endovascular repair for AAA under either general or local anesthesia. Perioperative information, including demographic information, comorbidities (including the history of smoking, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and related surgery, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal insufficiency), a preoperative complete blood count, serum creatinine and serum albumin levels, maximum diameter, interventional data, postoperative complications, and follow-up information were collected and recorded.

Novel SIMs, including NLR, PLR, SII, SIRI, and HRR, were calculated by preoperative whole blood count. The calculation formula for each is shown in Table 1. The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was used to evaluate the diagnostic potential of each novel SIM, and the patients were divided into subgroups for subsequent analysis based on the cut-off value calculated by the Youden index.

| Novel SIMs | Computing method |

| NLR | Neutrophil count (N)/lymphocyte count (L) |

| PLR | Platelet cell count (P)/lymphocyte count (L) |

| SII | Neutrophil count (N) |

| SIRI | Neutrophil count (N) |

| HRR | Hemoglobin (Hb)/red cell distribution width (RDW) |

SIMs, systemic inflammatory markers; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index; HRR, hemoglobin-to-red cell distribution width.

After discharge, patients were regularly monitored by ultrasound, contrast-enhanced ultrasound, or CTA. The survival status was mainly obtained by telephone or outpatient follow-up. Death was considered as the endpoint event, and patients were monitored until either the event occurred or censorship took place. Patients who did not have an endpoint event were considered until their last follow-up (April 2023), and the average duration of each follow-up was calculated.

Categorical variables are shown as counts and percentages and were compared

using either Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests, depending on the circumstances.

Continuous variables were presented as mean

The study included a cohort of 147 patients who underwent elective EVAR for AAA.

Table 2 displays the clinical demographics and baseline characteristics of the

participants in this investigation. The average age was 72.24

| Variable | Overall (N = 147) | ||

| 30-day mortality | 4 (2.70%) | ||

| Coronary artery syndrome | 3 (2.04%) | ||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1 (0.68%) | ||

| 30-day complications | 17 (11.5%) | ||

| Hemorrhage | 4 (2.70%) | ||

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 2 (1.35%) | ||

| Puncture site hematoma | 2 (1.35%) | ||

| Pseudoaneurysm | 1 (0.68%) | ||

| Radiographic contrast nephropathy | 2 (1.35%) | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 5 (3.38%) | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 4 (2.70%) | ||

| Respiratory failure | 2 (1.35%) | ||

| Gastrointestinal ischemia | 4 (2.70%) | ||

AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm.

The incidence of perioperative complications was 11.5% (17/147). Four patients died during the perioperative period; three of them died of acute coronary syndrome, and one died of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to postoperative stress, as shown in Table 2.

The median duration of follow-up was 34.28

The results of the preoperative whole blood examination indicated that the

mortality group had significantly lower preoperative hemoglobin levels

(p

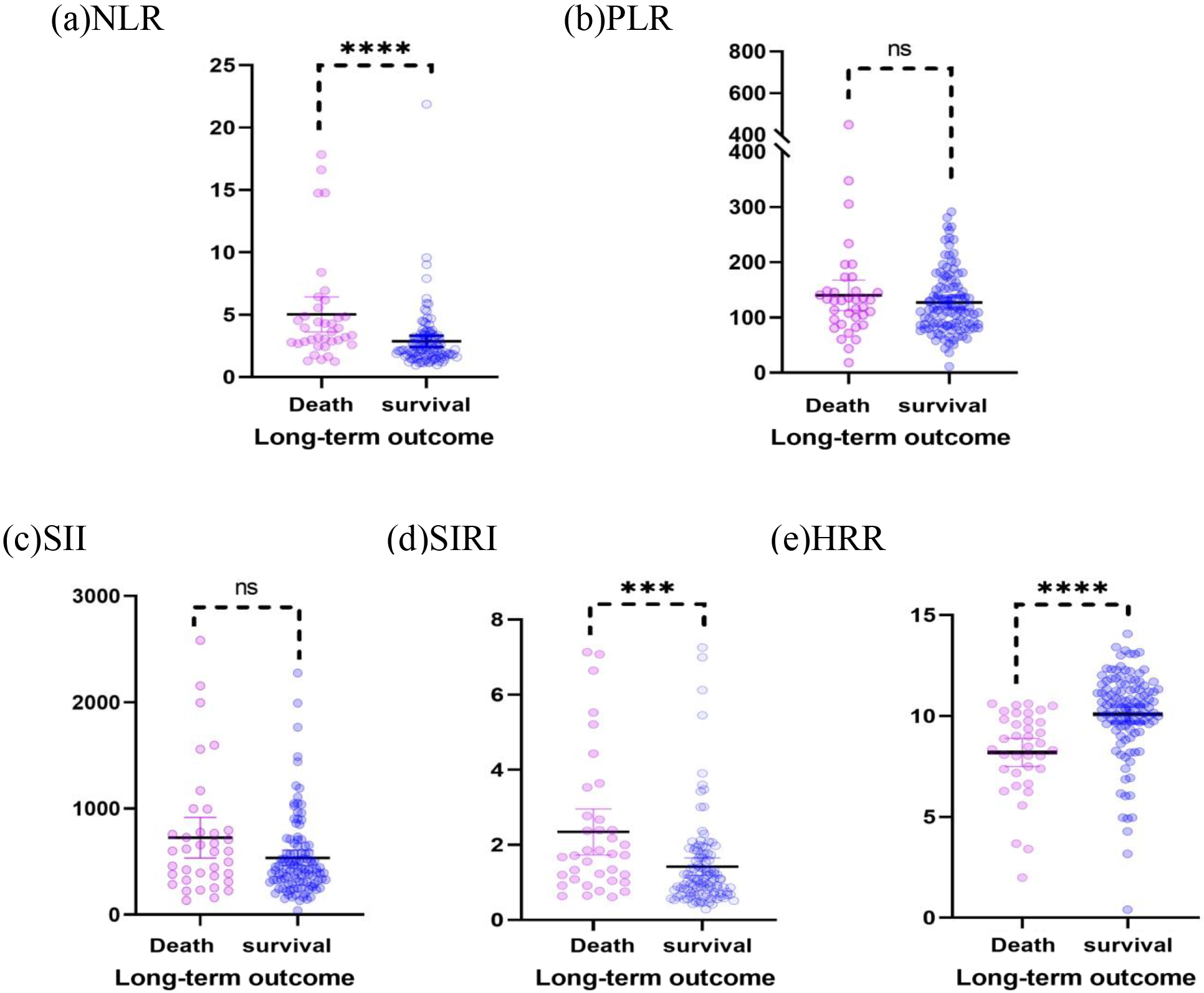

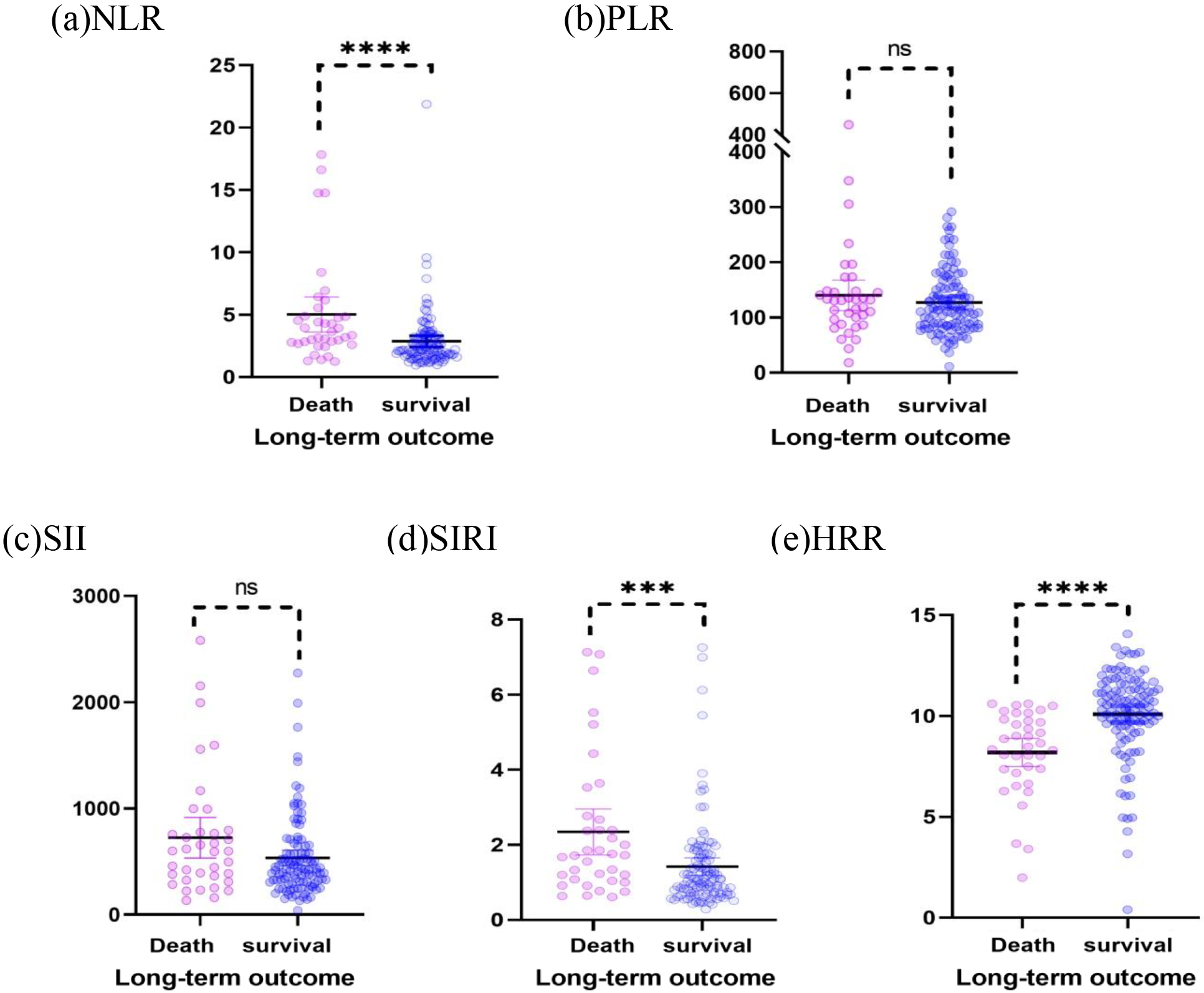

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Scatter plots of the NLR, PLR, SII, SIRI, and HRR show the

distribution in the survival group (n = 110) and mortality group (n = 37). (a)

The NLR of the death group was higher than that of the survival group (p

| Variable | All (N = 147) | Survival (N = 110) | Death (N = 37) | p-value |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | 72.24 |

70.52 |

77.38 |

0.000* |

| Sex, male | 128 (83.07%) | 97 (88.18%) | 31 (83.78%) | 0.490 |

| BMI, kg/m |

24.34 |

24.83 |

22.87 |

0.007* |

| Medical history and comorbidities | ||||

| Smoking history | 67 (44.26%) | 50 (45.45%) | 17 (45.95%) | 0.959 |

| Hypertension | 107 (72.79%) | 78 (70.91%) | 29 (78.39%) | 0.377 |

| Diabetes | 26 (17.69%) | 18 (16.36%) | 8 (21.62%) | 0.468 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 43 (29.25%) | 32 (29.09%) | 11 (29.73%) | 0.941 |

| COPD | 11 (7.48%) | 5 (4.55%) | 6 (16.21) | 0.020* |

| Coronary artery disease | 70 (47.62%) | 50 (45.45%) | 20 (54.05%) | 0.365 |

| Myocardial infarction | 33 (22.45%) | 26 (23.64%) | 7 (18.92%) | 0.552 |

| Prior CABG | 7 (4.76%) | 6 (5.45%) | 1 (2.70) | 0.497 |

| Prior PCI | 25 (17.01%) | 21 (19.09%) | 4 (10.81%) | 0.246 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 25 (17.01%) | 16 (14.55%) | 9 (24.32) | 0.171 |

| Chronic renal impairment | 16 (10.88%) | 8 (7.27%) | 8 (21.62) | 0.015* |

| Clinical features | ||||

| WBCs ( |

6.18 (5.35–7.74) | 6.09 (5.26–7.55) | 6.56 (5.66–8.06) | 0.252 |

| Neutrophil count ( |

3.84 (3.11–5.03) | 3.69 (3.08–4.55) | 4.78 (3.49–6.15) | 0.006* |

| Lymphocyte count ( |

1.50 (1.14–2.02) | 1.66 (1.19–2.13) | 1.22 (1.03–1.62) | 0.001* |

| Monocyte count ( |

0.49 (0.39–0.57) | 0.49 (0.38–0.57) | 0.48 (0.40–0.56) | 0.975 |

| Red cell distribution width | 12.9 (12.5–13.5) | 12.8 (12.4–13.4) | 13.2 (12.65–14.45) | 0.054 |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 129.0 (115.25–141.0) | 136.0 (120.0–144.0) | 116.0 (98.50–124.50) | 0.000* |

| Platelets (n/µL) | 181.0 (146.0–220.0) | 186.0 (158.0–231.5) | 161.0 (106.5–191.5) | 0.003* |

| NLR | 2.58 (1.79–3.70) | 2.18 (1.70–3.31) | 3.63 (2.72–5.21) | 0.000* |

| PLR | 116.07 (85.95–155.45) | 113.84 (84.54–157.52) | 130.68 (92.33–147.8) | 0.444 |

| SII | 445.33 (311.03–708.63) | 426.21 (305.83–646.41) | 597.73 (345.26–786.11) | 0.072 |

| SIRI | 1.20 (0.77–1.94) | 1.06 (0.70–1.74) | 1.72 (1.06–2.72) | 0.001 |

| HRR | 10.08 (8.35–11.20) | 10.48 (9.44–11.52) | 8.49 (7.28–9.80) | 0.000* |

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | 83.0 (77.50–104.0) | 80.0 (70.0–99.0) | 99.5 (78.0–130.5) | 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 39.0 (36.0–41.0) | 39.0 (37.0–41.0) | 36.0 (34.5–38.5) | 0.000* |

| Aneurysm diameter (mm) | 55.0 (50.0–65.0) | 55.0 (48.0–60.0) | 64.0 (54.0–75.0) | 0.001* |

* indicates the p-value is less than 0.05.

Data are presented as n (%), mean

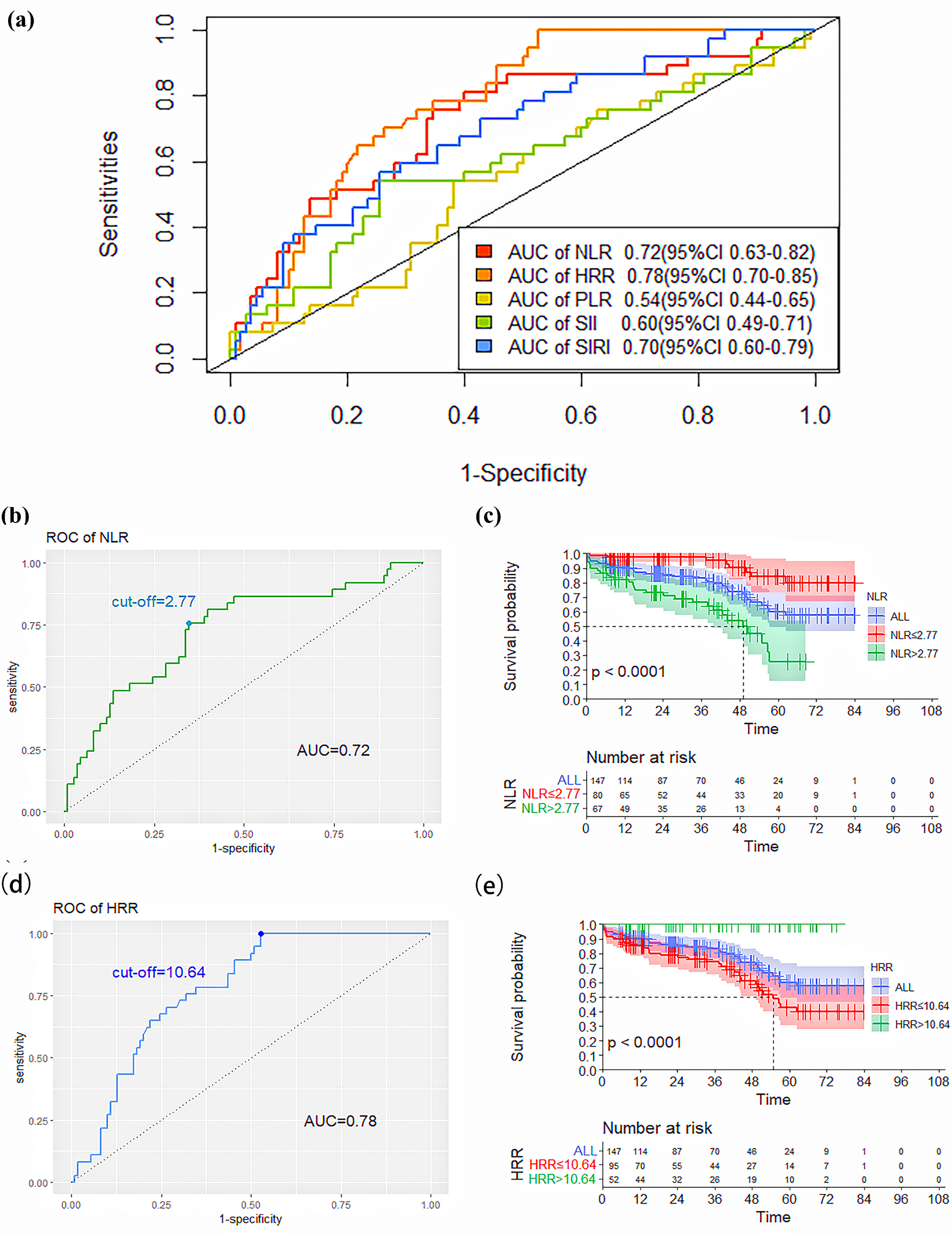

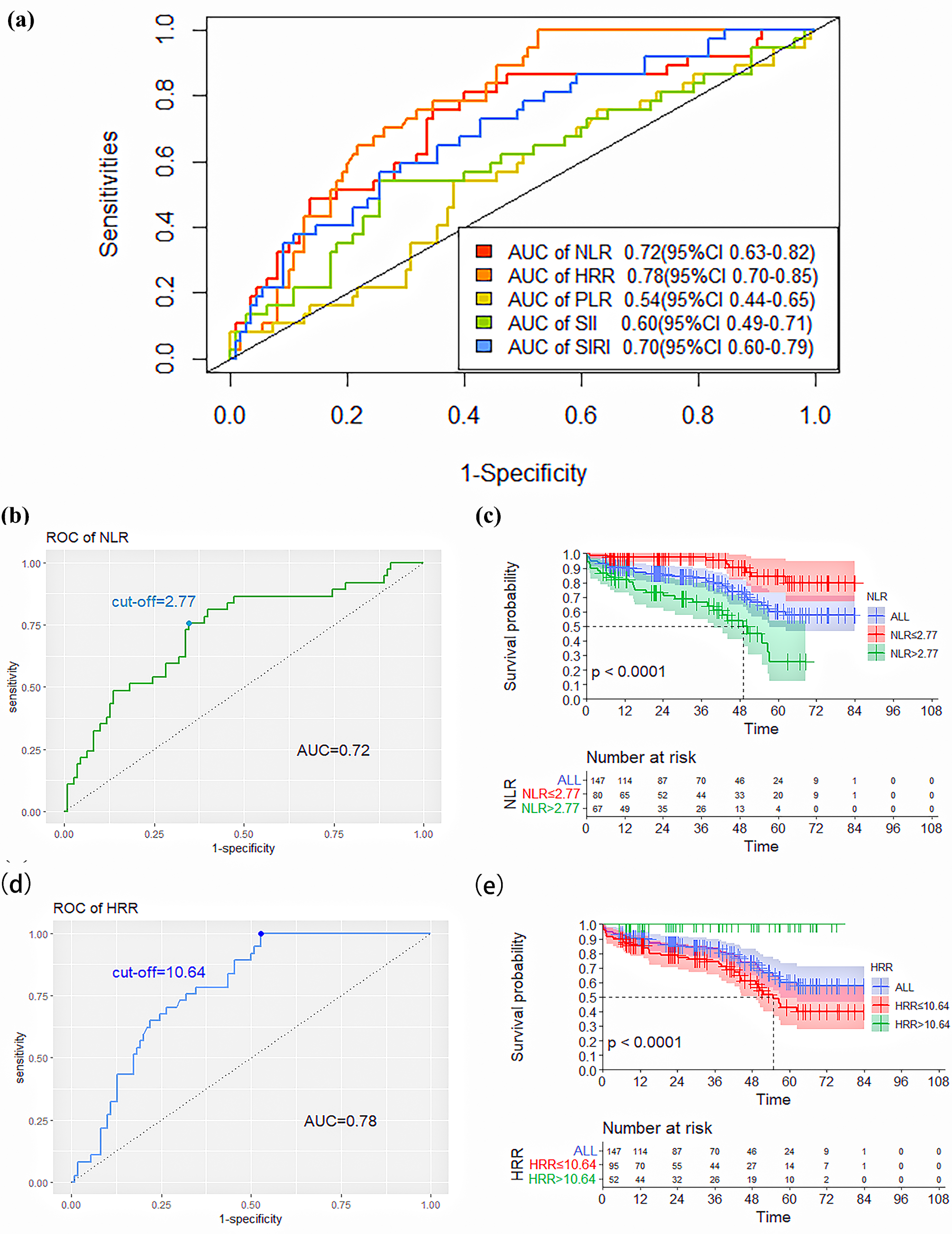

The ROC curve was used to analyze the predictive ability of novel SIMs for death after elective EVAR. Based on the AUC value, we found that NLR (AUC: 0.72, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 0.63–0.82) and HRR (AUC: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.70–0.85) had significantly higher abilities to predict patient death compared to PLR (AUC: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.44–0.65), SII (AUC: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.49–0.71) and SIRI (AUC: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.60–0.79), as shown in Table 4 and Fig. 2a. The NLR and HRR values corresponding to the greatest value of the Youden index were calculated as the ideal cut-off points on the ROC curve of death.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.ROC curves of the NLR, PLR, SII, SIRI, and HRR for predicting

death. (a) ROC curves of the NLR, PLR, SII, SIRI, and HRR for predicting

mortality. (b) ROC curves and the cut-off value of the NLR for predicting

mortality. (c) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of the lower-NLR and higher-NLR

groups (p

| Variable | AUC (95% CI) | Cut-off point | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| NLR | 0.72 (0.63–0.82) | 2.77 | 0.76 | 0.65 |

| HRR | 0.78 (0.70–0.85) | 10.64 | 1.00 | 0.47 |

| PLR | 0.54 (0.44–0.65) | 130.30 | 0.54 | 0.62 |

| SII | 0.60 (0.49–0.71) | 589.12 | 0.54 | 0.75 |

| SIRI | 0.70 (0.60–0.79) | 1.67 | 0.58 | 0.75 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; AUC, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

The ROC curve analysis showed that an NLR value of 2.77 was the calculated

cut-off point for predicting death, with a sensitivity of 76% and a specificity

of 65%. According to the cut-off value, patients were divided into the lower-NLR

(

Moreover, the determined threshold for HRR was 10.64. Further, HRR

| Variable | Overall (N = 147) | NLR |

NLR |

p-value | |

| All cause death | 37 (25.17%) | 9 (11.11%) | 28 (42.42%) | 0.000* | |

| Aneurysm-related death | 2 (1.36%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.03%) | 0.115 | |

| MACE | 15 (10.2%) | 3 (3.7%) | 12 (18.18%) | 0.004* | |

| Renal failure | 2 (1.36%) | 1 (1.23%) | 1 (1.52%) | 0.884 | |

| Multiple organ failure | 5 (3.4%) | 1 (1.23%) | 4 (6.06%) | 0.108 | |

| Cancer | 3 (2.04%) | 1 (1.23%) | 2 (3.03%) | 0.444 | |

| COVID-19 | 6 (4.08%) | 2 (2.47%) | 4 (6.06%) | 0.247 | |

| Others | 4 (2.72%) | 1 (1.23%) | 3 (4.55%) | 0.220 | |

| Variable | Overall (N = 147) | HRR |

HRR |

p-value | |

| All cause death | 37 (25.17%) | 33 (37.5%) | 4 (6.78%) | 0.000* | |

| Aneurysm-related death | 2 (1.36%) | 2 (2.27%) | 0 (0%) | 0.224 | |

| MACE | 15 (10.2%) | 15 (17.05%) | 0 (0%) | 0.001* | |

| Renal failure | 2 (1.36%) | 2 (2.27%) | 0 (0%) | 0.224 | |

| Multiple organ failure | 5 (3.4%) | 5 (5.68%) | 0 (0%) | 0.062 | |

| Cancer | 3 (2.04%) | 2 (2.27%) | 1 (1.69%) | 0.808 | |

| COVID-19 | 6 (4.08%) | 3 (3.41%) | 3 (5.08%) | 0.615 | |

| Others | 4 (2.72%) | 4 (4.55%) | 0 (0%) | 0.097 | |

* indicates the p-value is less than 0.05.

Data are presented as n (%). MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

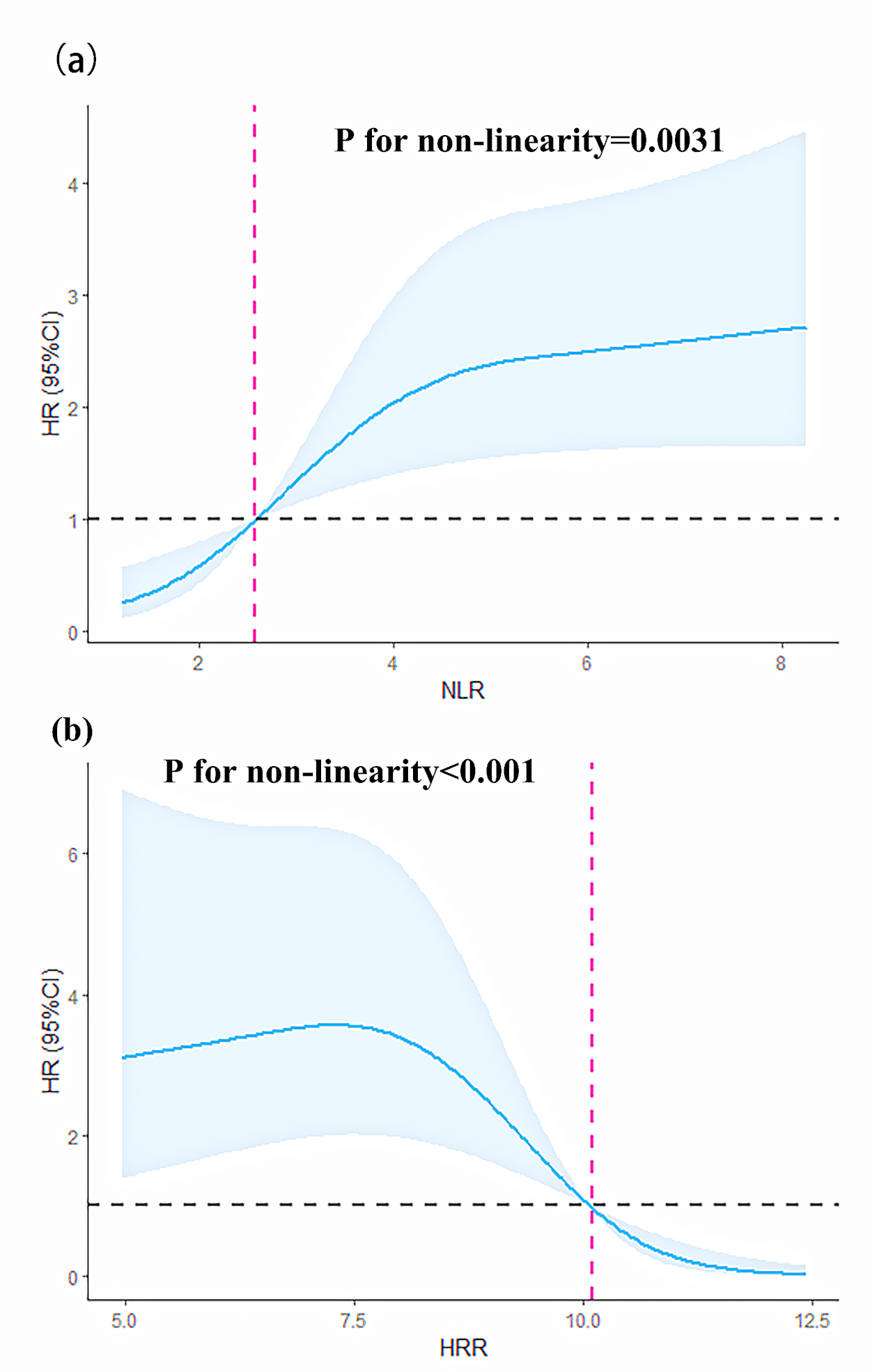

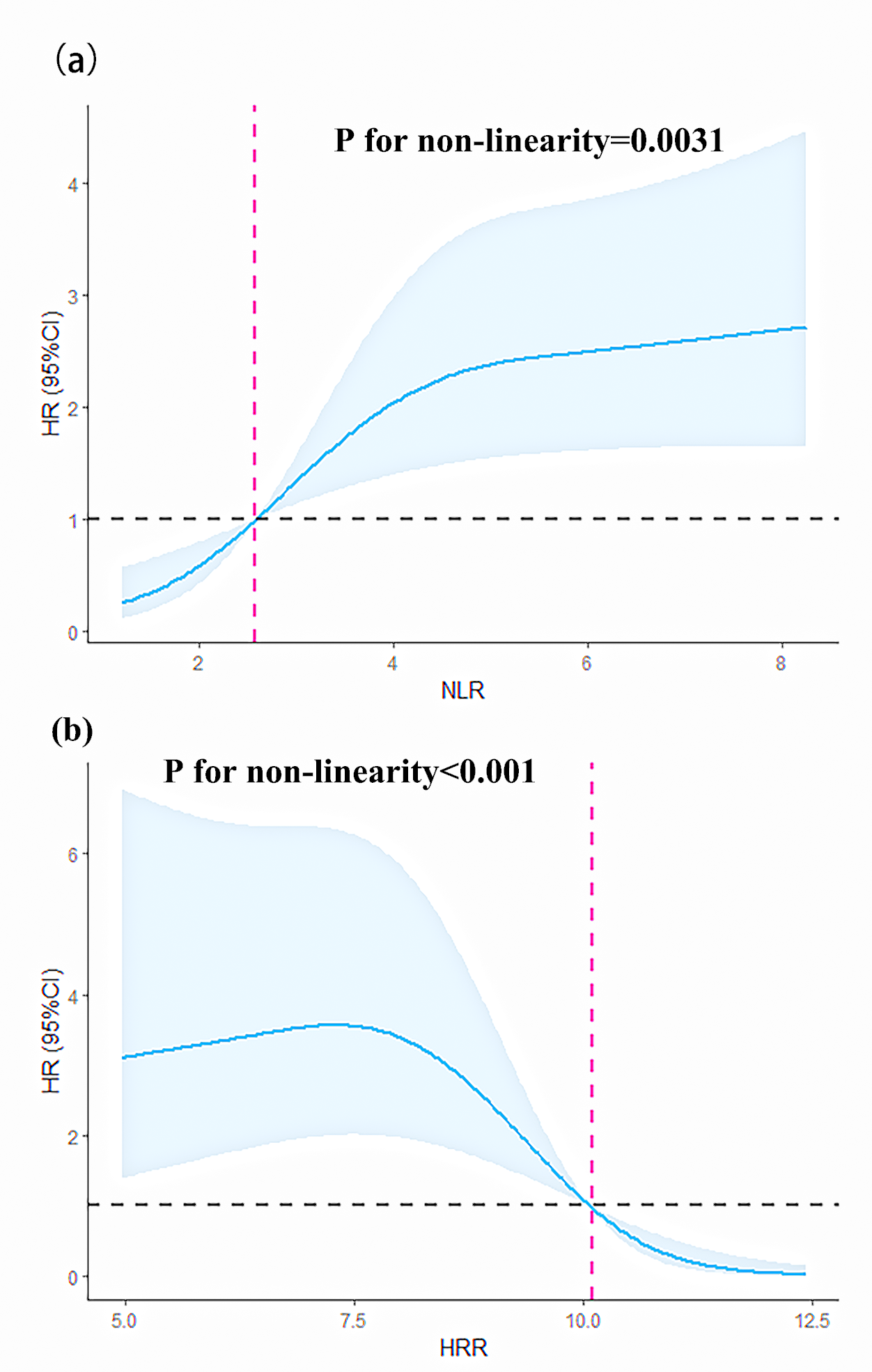

We modeled and visualized the relationships of NLR/HRR and all-cause mortality

using restricted cubic splines. The results showed that when the NLR

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Restricted cubic splines of the NLR and HRR for predicting HR. (a) Restricted cubic splines of the nonlinear relationship between NLR and HR. (b) Restricted cubic splines of the nonlinear relationship between HRR and HR. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

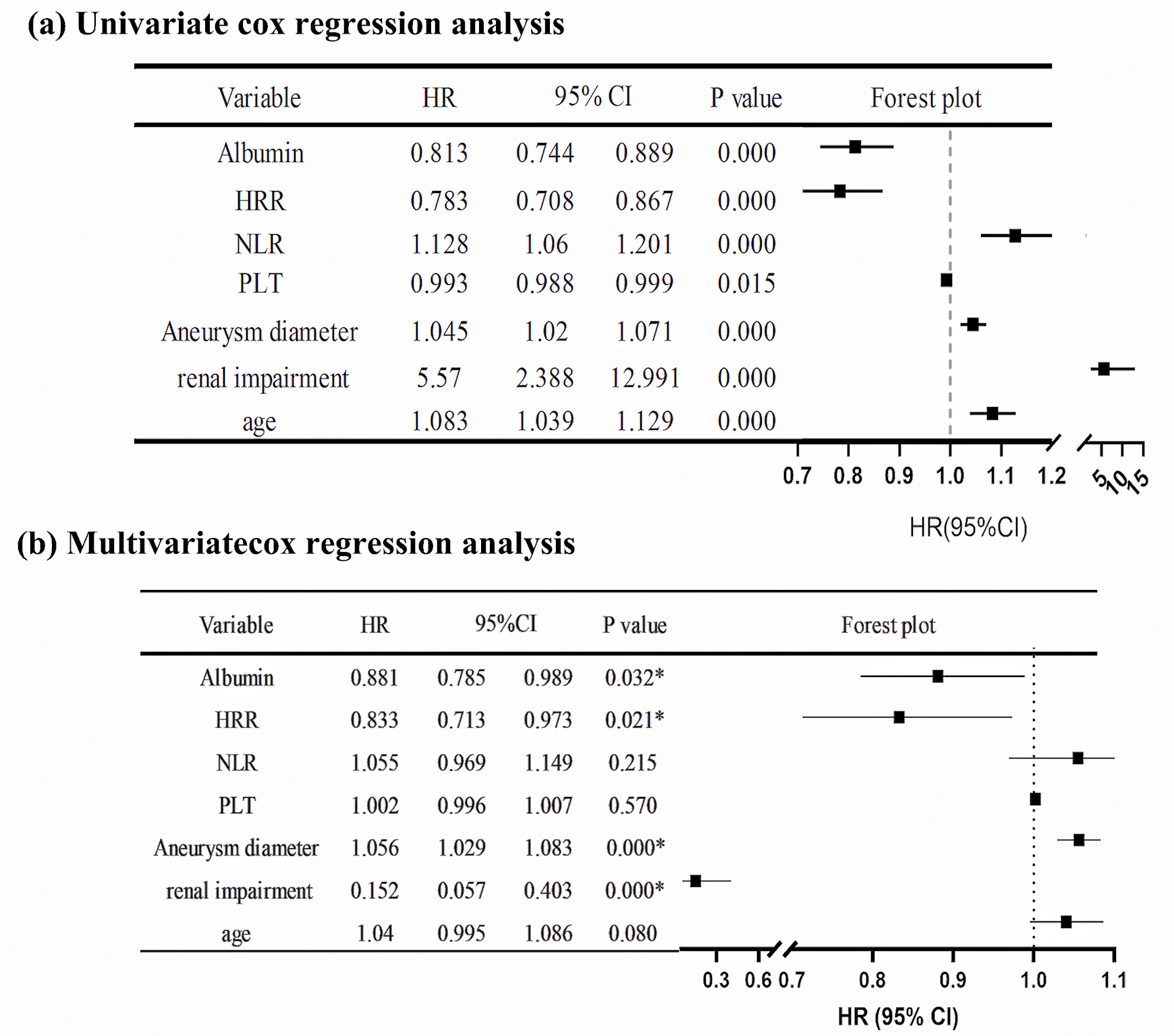

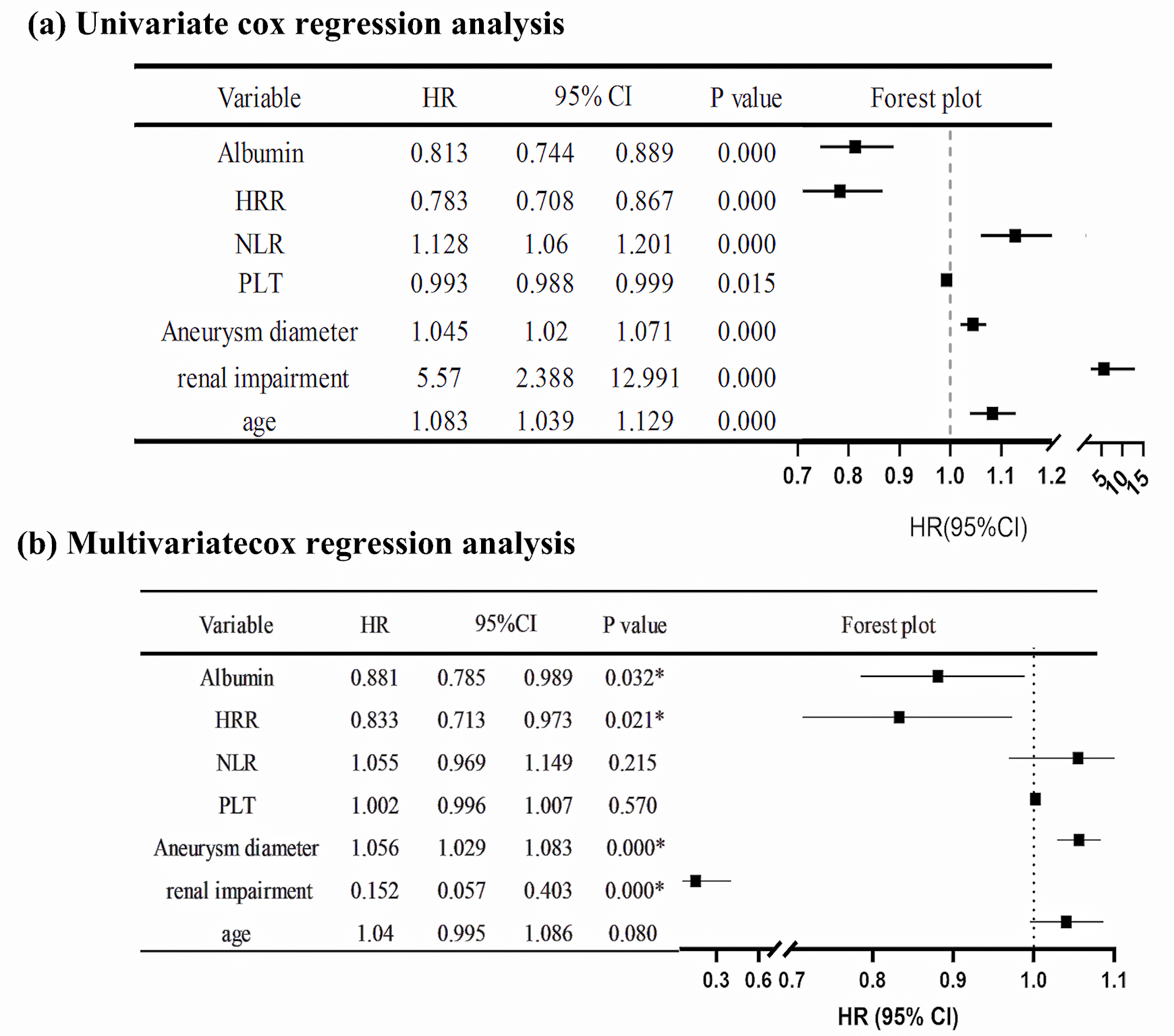

The variables included in the Cox regression analysis were age, gender, smoking

history, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, COPD, coronary heart disease,

myocardial infarction, previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), previous

percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), cerebrovascular accident, chronic renal

insufficiency, hemoglobin, platelet count, NLR, HRR, albumin, and aneurysm

diameter. The results of the univariate Cox regression analysis showed that age

(HR = 1.083, p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Cox regression analysis of the hazard ratio for death after EVAR in AAA patients. (a) Univariate Cox regression analysis of HR after EVAR in AAA patients. (b) Multivariate Cox regression analysis of HR after EVAR in AAA patients. * indicates the p-value is less than 0.05. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; PLT, platelets.

We presented a detailed analysis of clinical factors and hematologic markers

that have predictive significance for death in AAA patients undergoing EVAR,

particularly the relationship between SIMs and long-term death. The results

suggested that an increased preoperative NLR and a decreased HRR were associated

with increased death after EVAR. AAA patients with an NLR

Recently, SIMs have received considerable attention as independent prognostic

indicators for mortality and morbidity in several diseases, such as cancers,

cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and inflammatory conditions [28, 29, 30, 31].

Thus, using SIMs as inexpensive and easily accessible prognostic indicators for

follow-up is steadily increasing in clinical and academic settings. The

application of NLR in the prognosis of mortality and morbidity in coronary artery

disease [32], atherosclerosis [15], and peripheral artery disease [33] has been

widely studied. In terms of coronary artery disease, higher NLR values can

predict not only the progression of coronary atherosclerosis [34] but also the

risk of death after CABG and PCI [35, 36]. In

addition, in five randomized trials involving 600,875 participants, NLR has been

a proven predictor of incident major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and

all-cause mortality [15]. However, SII and SIRI use three blood cell subtypes and

might provide a more accurate representation of the balance between inflammatory

and immunological responses. Several studies have shown that elevated SII is

associated with an increased incidence and severity of coronary heart disease

[37, 38] and with a higher risk of MACEs (HR: 1.65) and total major events (HR:

1.53) in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients [39]. Similarly, SIRI was an

independent predictor of MACEs in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients

undergoing PCI [40]. However, there are relatively limited studies on HRR. In a

retrospective study of 6046 hospitalized coronary atherosclerotic heart disease

patients undergoing PCI, decreased levels of HRR (HRR

The predictive significance of SIMs in aortic-related surgery has also received

increasing attention. Several studies have proposed the predictive value of SIMs

for long-term survival after EVAR. King et al. [24] found that

preoperative NLR (NLR

NLR represents a chronic, mild systemic inflammatory response, often accompanied by elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines. This reaction enables the body to respond to inflammatory stimuli, activating inflammatory cells within the plaque and leading to a catastrophic cascade. Conversely, chronic inflammation appears to be significantly involved in the development of AAA [43]. Inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, can generate oxygen-derived free radicals that can trigger apoptosis and induce phenotypic alterations in vascular smooth muscle cells. This process eventually results in a partial decline in the production and repair capability of the vascular matrix [44]. In addition, proteases secreted by inflammatory cells such as neutrophils might result in the fragmentation of microfibrils inside the matrix, ultimately causing a reduction in the elasticity of the cell wall [45]. When the extracellular matrix (ECM) structure is destroyed and the media loses its elasticity, soluble blood components, including various inflammatory cells, can move and build up in the media through the highly vascularized adventitia. This, combined with platelet aggregation and coagulation system activation, encourages the development of luminal thrombosis. As a result, the aorta dilates and becomes more susceptible to rupturing in cases of AAA [46]. On the other hand, the development of atherothrombosis relies on the systemic chronic inflammatory response. The high neutrophil count is positively associated with the risk of plaque rupturing [47, 48] and increases the risk of microcirculation thrombosis [49]. Monocytes also play a role in initiating and promoting atherosclerosis, and their counts have been described as predictors of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) mortality, independent of other classical risk factors [50, 51]. Lymphopenia is an immunosuppressive and adverse physiologically stressful state that is associated with poor outcomes [52, 53]. Therefore, a rise in NLR may be linked to a high incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, as supported by our subgroup analysis findings, which indicate that patients with a high NLR value had more cardiovascular and cerebrovascular deaths. Moreover, while NLR does not independently predict the postoperative prognosis of AAA, its predictive performance is relatively better than that of novel SIMs, such as PLR, SII, and SIRI. This may be attributed to the stability of NLR levels over time, as reported by Wang et al. [54]. In five contemporary randomized trials, Adamstein et al. [15] found that NLR levels remained stable over time among patients assigned to the placebo, and this consistency over time provides a clinical rationale for their use as a simple and reliable measure for follow-up. The study has also shown that medication interventions such as aspirin and statins may regulate NLR by reducing the inflammatory response through pleiotropic effects [15]. Patients with high preoperative NLR should be closely monitored for the development of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events during the perioperative period and in the long term. Additionally, assessing the need for prolonged administration of lipid-lowering and antiplatelet medications for preventive purposes is important.

Lower hemoglobin is a crucial marker of potential inflammatory states and is associated with poor prognosis in several diseases [55]. In studies of AAAs, lower hemoglobin concentration is independently associated with higher probabilities of 30-day death, more in-hospital adverse outcomes, and reduced long-term survival after EVAR [56, 57]. Meanwhile, red cell distribution width (RDW) can reflect the underlying inflammatory state and is associated with adverse cardiovascular disease outcomes [58, 59]. Förhécz et al. [60] conducted a retrospective cohort study involving 195 patients diagnosed with chronic heart failure. The findings revealed a significant correlation between RDW and inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein and other soluble cytokines [60]. A higher preoperative RDW level is linearly and high-risk associated with 5-year survival after EVAR [23]. The reason may be that inflammatory factors promote the formation of lysophosphatidylcholine in systemic inflammation, and increased phosphatidylserine exposure leads to lipid remodeling of the erythrocyte membrane, thereby impacting the function and longevity of erythrocytes. Inflammation accelerates the clearance of red blood cells (RBCs) by activating macrophages, reducing the life span of RBCs, and decreasing hemoglobin levels. An increase in RDW may reflect an elevation in the number of nonfunctional RBCs or the destruction of healthy cells [61, 62, 63]. The decrease in hemoglobin (Hb) represents the impaired oxygen-carrying function, while the rise in RDW reflects the negative effect of inflammation and other causes on the erythroid function of the bone marrow [41]. The HRR, calculated by Hb/RDW, reflects the superposition of these phenomena and has a broader range of applications. A meta-analysis reported the advantage of combining RDW with Hb for cardiovascular disease prognostic ratios, indicating that HRR is a highly effective strategy for predicting cardiovascular disease outcomes [64]. In addition, Qu et al. [65] analyzed 233 elderly patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) and found that HRR was a stronger predictor of frailty compared to hemoglobin or RDW; moreover, frailty was identified as a significant indication of prognostic factors for AAA. However, this measure has only been studied in a particular fraction of cancer and cardiovascular disease instances [66, 67, 68]. There is a lack of data on HRR in patients undergoing endovascular repair of AAAs. This is the first study to include HRR in the prognosis analysis of AAA, and it shows that decreased HRR indicates increased death after AAA surgery and can be used as an independent risk factor for long-term death. Subgroup analysis showed that cardiovascular and cerebrovascular mortality was more obviously increased in the lower-HRR group. Thus, the Hb/RDW ratio is a simple and practical prediction tool that can help clinicians estimate the risk stratification of EVAR patients.

Caution should still be exercised when considering using novel SIMs as a surgical consideration for AAA, as our studies have several limitations. First, as a single-center retrospective observational study, this study is limited by its relatively small sample size, leaving certain confounding factors unmeasured. Secondly, only preoperative whole blood cell counts were collected and used to calculate the SIMs, and there were no relevant data regarding the follow-up. Therefore, it is hard to study the impact of the variation in these SIMs, while their stability may also be uncertain. In previous studies, the cut-off values of inflammatory indicators in each system exhibited significant variation. There is a lack of consensus on the best threshold and the degree of association with various outcomes. Thirdly, the relevant pathophysiological mechanisms remain uncertain. Lastly, it should be emphasized that these SIMs have been reported to be associated with other types of cardiovascular diseases. Moreover, the use of SIMs as predictive markers for AAA patients has potential overlap and can make it be complicated by the fact that they can also be present in other types of aortic disease, such as thoracic aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection-renal aneurysm, and splenic aneurysm. These issues may hinder the clinical application of SIMs. Therefore, SIMs require additional comprehensive and carefully designed multicenter investigations with large sample sizes to validate these findings since they have the potential to serve as a valuable clinical tool for categorizing the risk of EVAR patients.

High preoperative NLR and low preoperative HRR indicate a decreased long-term survival rate of patients with an AAA after elective EVAR. HRR was identified as an independent risk factor for postoperative prognosis following elective EVAR via multivariate Cox regression. Patients whose HRR is below 10.64 should have perioperative and long-term cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events closely monitored, and the extension of anti-lipid and anti-platelet drug therapies should be considered necessary. However, further comprehensive and meticulously planned multicenter investigations are required to confirm these findings due to the existing limitations.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

YL, YJL designed the research study and provided help and advice all the time. WXZ, NZ collected the data. ZYW, YPD analyzed the data. WXZ, ZYW wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Hospital. The ethical approval opinion number was 2023BJYEC-128-01. The clinical trial poses little risk to the subjects and has been reviewed and approved by the ethics committee after being exempt from informed consent of the subjects.

We would like to thank the Department of Vascular Surgery, Beijing Hospital, National Center for Geriatrics for the great support of successful collection of relevant materials. We would like to express our sincere appreciation to all the doctors and nurses in the vascular surgery department of Beijing Hospital for their efforts in the treatment process.

This research was funded by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (No. BJ-2021-205); the National Key Research and Development Project of China (No. 2020YFC2008003); the Beijing Hospital Clinical Research 121 Project (No. BJ-2018-089); CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS. 2021-I2M-1-050); PUMC Discipline Construction Project (No. 201920102101).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.