1 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Guangdong Cardiovascular Institute, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital, Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences, 510080 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

2 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of South China Structural Heart Disease, 510080 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

3 Shantou University Medical College, 515041 Shantou, Guangdong, China

4 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery Center, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing Institute of Heart, Lung and Blood Vascular Diseases, 100029 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Background: The impact of dominant ventricular morphology on Fontan

patient outcomes remain controversial. This study evaluates long-term results of

right ventricle (RV) dominance versus left ventricle (LV) dominance in Fontan

circulation without hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). Methods: We

retrospectively examined 323 Fontan operations from our center. To minimize pre-

and intra-Fontan heterogeneity, 42 dominant RV patients were matched with 42

dominant LV patients using propensity score matching, allowing for a comparative

analysis of outcomes between groups. Results: The mean follow-up was 8.0

Keywords

- Fontan

- single ventricle

- ventricular morphology

- right ventricle

- death or transplantation

- Fontan failure

Single ventricle (SV) deficits are rare congenital heart defects characterized by either one severely underdeveloped ventricle, or the absence of the ventricular septum, resulting in a broad range of cardiac structural abnormalities [1, 2]. This life-threatening congenital heart defect necessitates prompt intervention, commonly through the Fontan operation [2, 3, 4]. This Fontan procedure, which may be executed in either one or multiple stages as a total cavopulmonary connection, provides palliation and treatment, achieving satisfactory long-term survival for SV patients [3, 4]. However, it carries risks of both cardiac and non-cardiac complications that could lead to Fontan failure, primarily due to decreased cardiac output and persistent elevated systemic venous pressure from the absence of a sub-pulmonary ventricle [5, 6]. Consequently, extensive research is underway to identify risk factors and improve Fontan techniques, aiming to enhance patient outcomes.

Morphological variations SV deficits can be categorized as left, right, or indeterminate. It is hypothesized that Fontan patients with a dominant right ventricle (RV) experience worse outcomes compared to those with a dominant left ventricle (LV), potentially due to differences in anatomy, embryological origin, and affiliated atrioventricular valves [7, 8]. Nevertheless, the impact of RV dominance on Fontan procedure outcomes continues to be a controversial issue [9, 10, 11], likely influenced by the significant heterogeneity observed in Fontan patients.

Despite evidence from previous studies suggesting that RV dominance in Fontan circulation, particularly among patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), leads to poorer outcomes compared to those with LV-dominance [12, 13], the reasons for this discrepancy are multifaceted. It’s speculated that the theoretical disadvantages of RV dominance are compounded by factors such as increased aortic stiffness and higher systemic afterload, outcomes often associated with Norwood surgery, further disadvantaging RV dominant systems [14, 15]. The connection between ventricular dominance and patient outcomes in non-HLHS Fontan circulation, however, remains unclear and contentious.

This ambiguity highlights the need for a nuanced understanding of how ventricular dominance influences long-term health and recovery in Fontan patients. Considering this complexity, we developed a propensity score matching (PSM) system aimed at reducing patient heterogeneity. This method enabled us to conduct a direct comparison of long-term outcomes between RV and LV dominance in Fontan patients, specifically excluding those with HLHS.

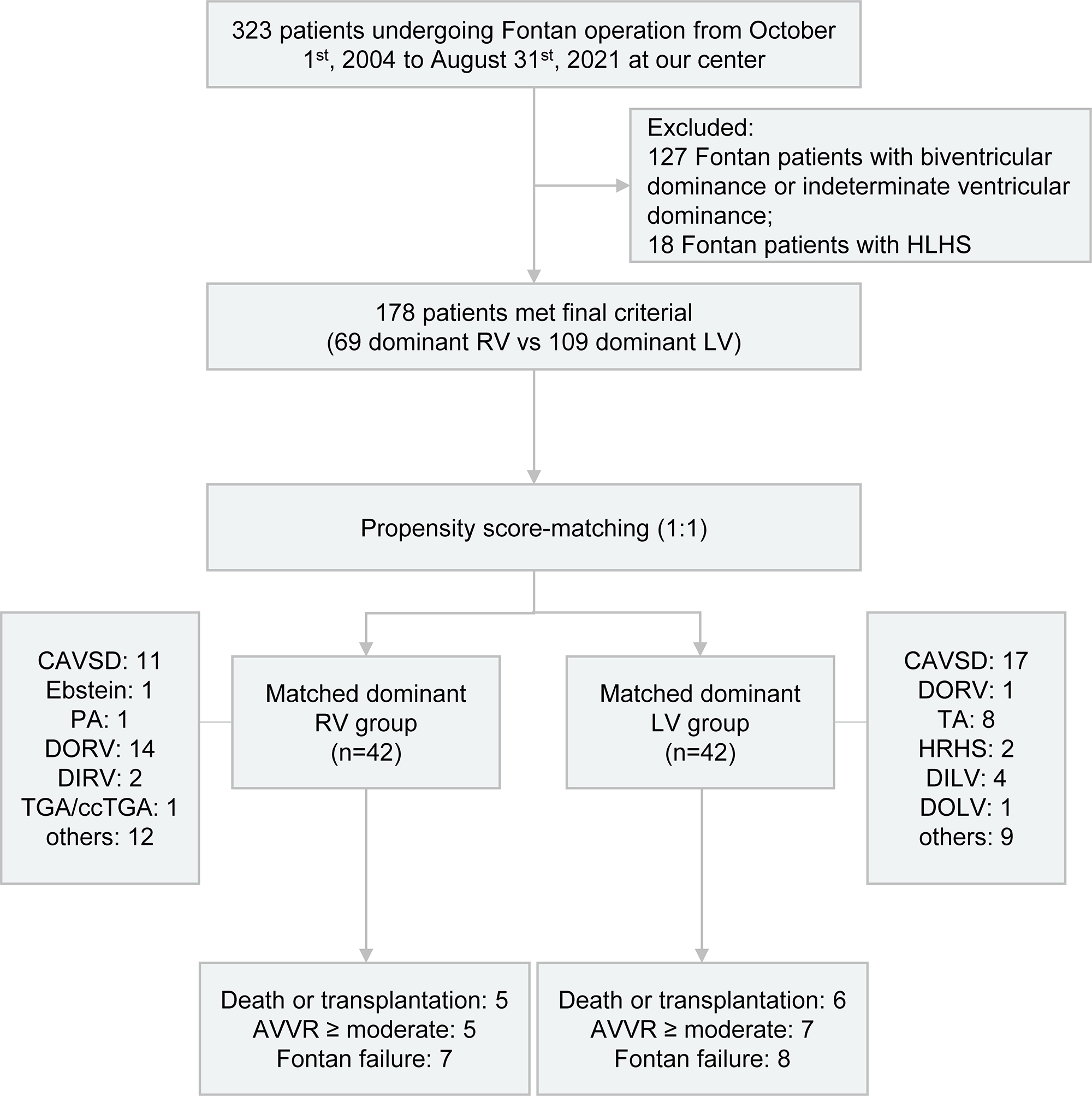

This was a single-center retrospective study of 323 patients who underwent Fontan operation from October 1st, 2004 to August 31st, 2021 at our center, and was performed as illustrated in Fig. 1. 127 Fontan patients with biventricular dominance or indeterminate ventricular dominance and 18 Fontan patients with HLHS were excluded. Eventually, a total of 178 patients with RV or LV dominance were enrolled in this study.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Flowchart depicting the study design and outcomes for Fontan patients categorized by either dominant RV or LV. HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; CAVSD, complete atrioventricular septal defect; PA, pulmonary atresia; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; DIRV, double inlet right ventricle; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; ccTGA, congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries; TA, tricuspid atresia; HRHS, hypoplastic right heart syndrome; DILV, double inlet left ventricle; DOLV, double outlet left ventricle; AVVR, atrioventricular valve regurgitation.

Ventricular morphological information and other baseline characteristics as well as perioperative and postoperative data were all reviewed and collected from the medical records of each patient. All medical records of enrolled patients were collected and extracted. The outpatient follow-up appointments were scheduled to be performed at 3, 6, and 12 months following the Fontan operation and annually thereafter. The follow-up echocardiograms were available in 190 of 196 patients (96.9%). Atrioventricular valve regurgitation (AVVR) assessed by echocardiogram was recorded as Grade 0 (none or trivial), Grade 1 (mild), Grade 2 (moderate), and Grade 3 (severe).

The primary outcomes were death or transplantation and Fontan failure during the

follow-up. The secondary outcome was AVVR

All data analysis were performed using SPSS software (version 26, IBM SPSS

statistics, Chicago, IL, USA) and R software (version 4.1.3, R Foundation for

Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Categorical variables were reported as

numbers with percentages and compared between the two groups using the chi-square

test. Continuous variables were reported as mean with standard deviation if

normally distributed or median with interquartile range if not normally

distributed. The student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were utilized

for comparisons between groups. Given the large heterogeneity in Fontan patients,

PSM was used to minimize the potential selection. Propensity scores were

calculated by logistic regression with variables (male sex, age at Fontan

operation, weight at Fontan operation, Fontan type, Fontan fenestration,

atrioventricular valve [AVV] morphology, atrial isomerism, dextrocardia,

anomalous pulmonary vein connection, AVVR

The baseline characteristics are shown in the Table 1. Before PSM matching, the

cohort comprised 69 patients in the RV-dominant group and 109 patients in the

LV-dominant group. There was a significant difference in AVV morphology between

the two groups (p

| Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||||

| Dominant RV | Dominant LV | SMD | p | Dominant RV | Dominant LV | SMD | p | ||

| n = 69 | n = 109 | n = 42 | n = 42 | ||||||

| Male | 47 (68.1%) | 70 (71.6%) | –0.081 | 0.594 | 27 (64.3%) | 27 (64.3%) | |||

| Age at Fontan operation, y | 5.0 (4.0–10.0) | 5.0 (4.0–11.0) | –0.039 | 0.987 | 6.0 (3.0–12.3) | 7.0 (4.0–13.0) | 0.164 | 0.507 | |

| Weight at Fontan operation, kg | 18.0 (14.5–24.5) | 16.5 (14.0–28.0) | –0.080 | 0.494 | 18.0 (14.5–33.4) | 18.3 (13.9–33.3) | –0.040 | 0.488 | |

| Fontan type | 0.247 | 0.659 | |||||||

| LT | 6 (8.7%) | 4 (3.7%) | –0.267 | 5 (11.9%) | 3 (7.1%) | –0.253 | |||

| ECC | 58 (84.1%) | 92 (84.4%) | 0.010 | 34 (81.0%) | 37 (88.1%) | 0.197 | |||

| Others | 5 (7.0%) | 13 (11.0%) | 0.144 | 3 (7.1%) | 2 (4.8%) | –0.074 | |||

| Fontan fenestration | 34 (49.3%) | 36 (33.0%) | –0.346 | 0.031 | 18 (42.9%) | 18 (42.9%) | |||

| AVV morphology | 0.931 | ||||||||

| Mitral valve | 6 (8.7%) | 59 (54.1%) | 0.912 | 6 (14.3%) | 7 (16.7%) | 0.048 | |||

| Tricuspid valve | 8 (11.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | –1.120 | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (2.4%) | ||||

| 2 AVV | 21 (30.4%) | 31 (28.4%) | –0.044 | 20 (47.6%) | 17 (40.5%) | –0.158 | |||

| Common AVV | 34 (49.3%) | 18 (16.5%) | –0.882 | 15 (35.7%) | 17 (40.5%) | 0.128 | |||

| Atrial isomerism | 23 (33.3%) | 12 (11.0%) | –0.713 | 9 (21.4%) | 10 (23.8%) | 0.076 | 0.794 | ||

| Dextrocardia | 6 (8.7%) | 6 (5.5%) | –0.140 | 0.603 | 4 (9.5%) | 5 (11.9%) | 0.104 | ||

| Anomalous pulmonary vein connection | 11 (15.9%) | 7 (6.4%) | –0.388 | 0.040 | 5 (11.9%) | 6 (14.3%) | 0.097 | 0.746 | |

| AVVR |

15 (21.7%) | 16 (14.7%) | –0.200 | 0.226 | 9 (21.4%) | 9 (21.4%) | |||

| AVV operation before or at Fontan | 18 (26.1%) | 12 (11.0%) | –0.482 | 0.009 | 10 (23.8%) | 6 (14.3%) | –0.204 | 0.266 | |

PSM, propensity score matching; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; SMD, standardized mean difference; LT, lateral tunnel; ECC, extracardiac conduit; AVV, atrioventricular valve; AVVR, atrioventricular valve regurgitation.

Before matching, chest drainage duration and length of postoperative

hospitalization were significantly longer in the RV-dominant group than those in

the LV-dominant group (p

| Before PSM | After PSM | |||||

| Dominant RV | Dominant LV | p | Dominant RV | Dominant LV | p | |

| n = 69 | n = 109 | n = 42 | n = 42 | |||

| CPB time, min | 142.0 (93.0–184.5) | 118.0 (88.0–154.0) | 0.084 | 125.0 (88.5–182.8) | 126.0 (98.5–156.0) | 0.989 |

| ACC time, min | 59.0 (0–90.5) | 35.0 (0–78.0) | 0.054 | 58.0 (0–89.3) | 55.0 (0–83.0) | 0.761 |

| Mechanical ventilation time, h | 8.7 (5.6–24.5) | 8.7 (4.8–18.6) | 0.532 | 8.2 (5.8–17.7) | 11.2 (7.4–32.0) | 0.207 |

| Length of ICU stay, d | 3.6 (1.7–5.9) | 3.3 (1.6–5.8) | 0.522 | 3.6 (1.7–6.1) | 3.7 (1.6–6.7) | 0.704 |

| Chest drainage duration, d | 13.0 (8.0–23.7) | 10.0 (6.2–19.0) | 0.049 | 14.5 (9.8–30.8) | 13.3 (6.2–21.5) | 0.248 |

| Length of postoperative hospitalization | 22.0 (15.0–34.0) | 18.0 (12.0–25.0) | 0.011 | 24.5 (15.0–37.0) | 22.0 (14.0–28.0) | 0.248 |

| In-hospital reintervention | 6 (8.7%) | 11 (10.1%) | 0.758 | 3 (7.1%) | 5 (11.9%) | 0.710 |

| In-hospital mortality | 3 (4.3%) | 6 (5.5%) | 1 (2.4%) | 3 (7.1%) | 0.608 | |

| Period of follow-up, y | 7.9 |

7.4 |

0.451 | 8.0 |

6.5 |

0.163 |

PSM, propensity score matching; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; ACC, aortic cross-clamping; ICU, intensive care unit.

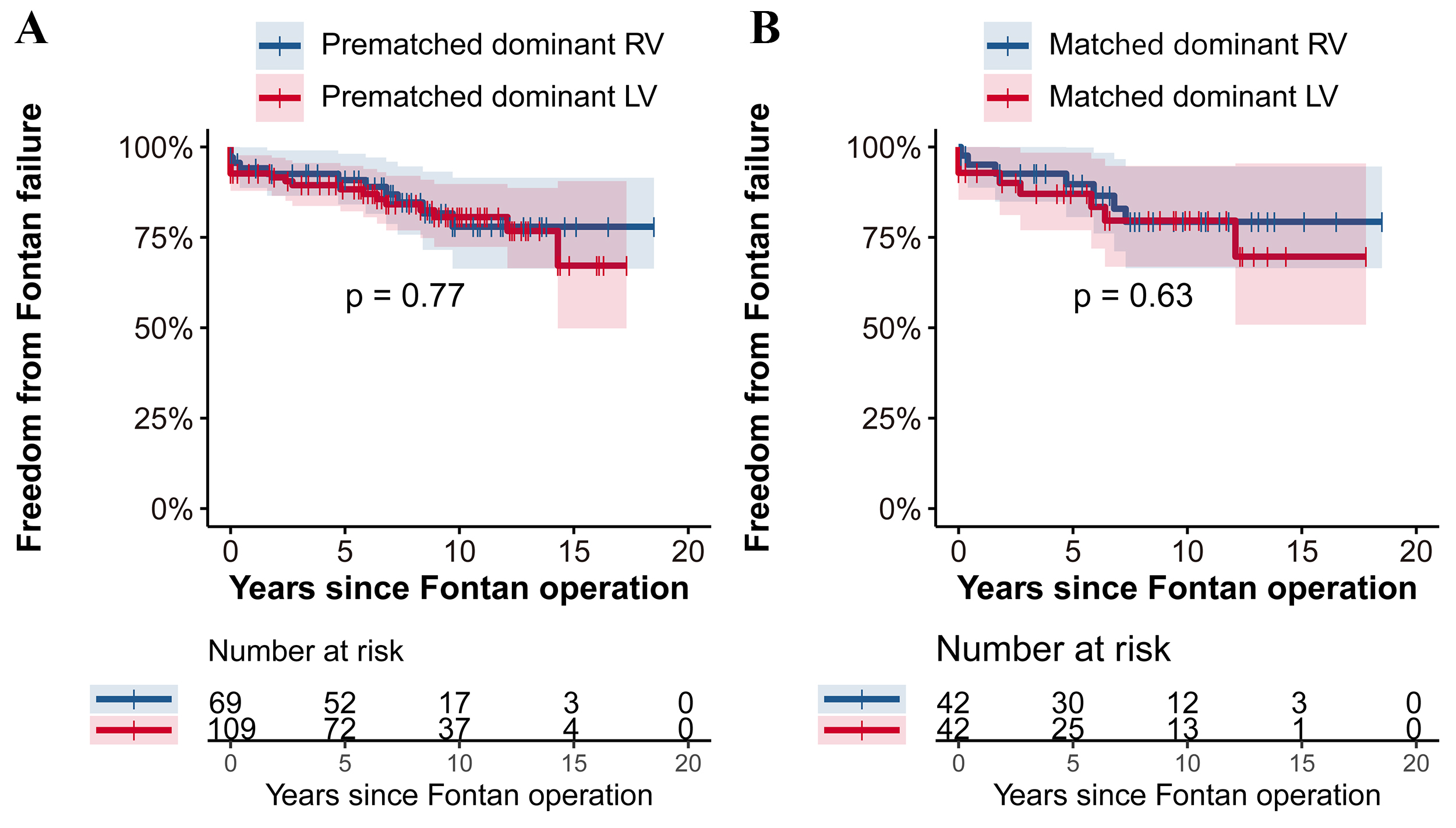

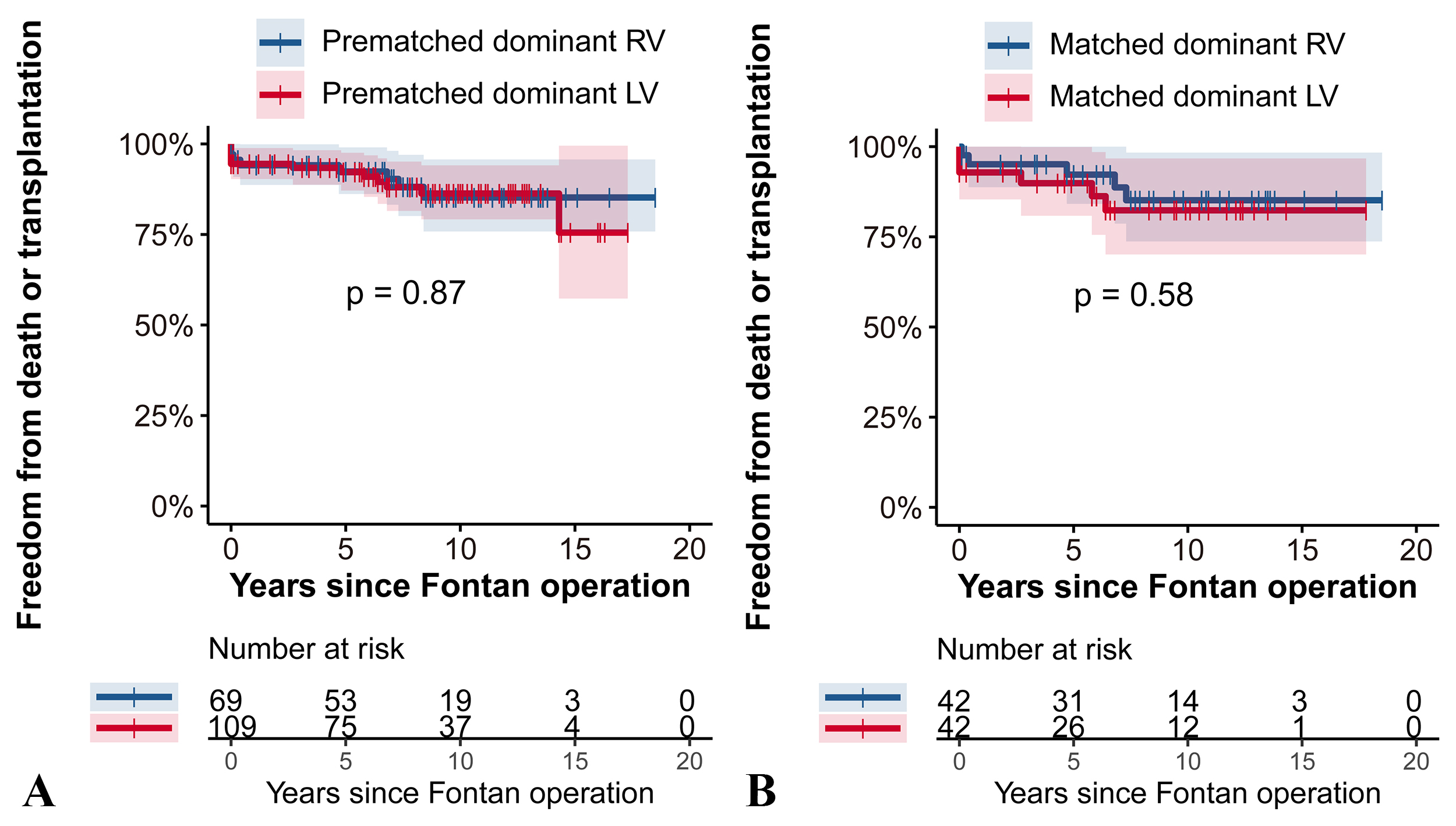

As shown in the Fig. 2, there were no significant differences in freedom from

death or transplantation between the two groups in either the prematched or

matched cohorts (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Freedom from death or transplantation RV vs. LV dominance analyzed with the Log-rank test in the prematched cohort (A) and the matched cohort (B). This figure illustrates the comparison of survival without death or transplantation between patients with dominant RV and LV before and after propensity score matching. (A) In the prematched cohort there were no significant differences in freedom from death or transplantation between the RV and LV groups (p = 0.87). (B) Similarly, in the matched cohort (B), survival rates remained comparable with no significant difference detected (p = 0.58). RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle.

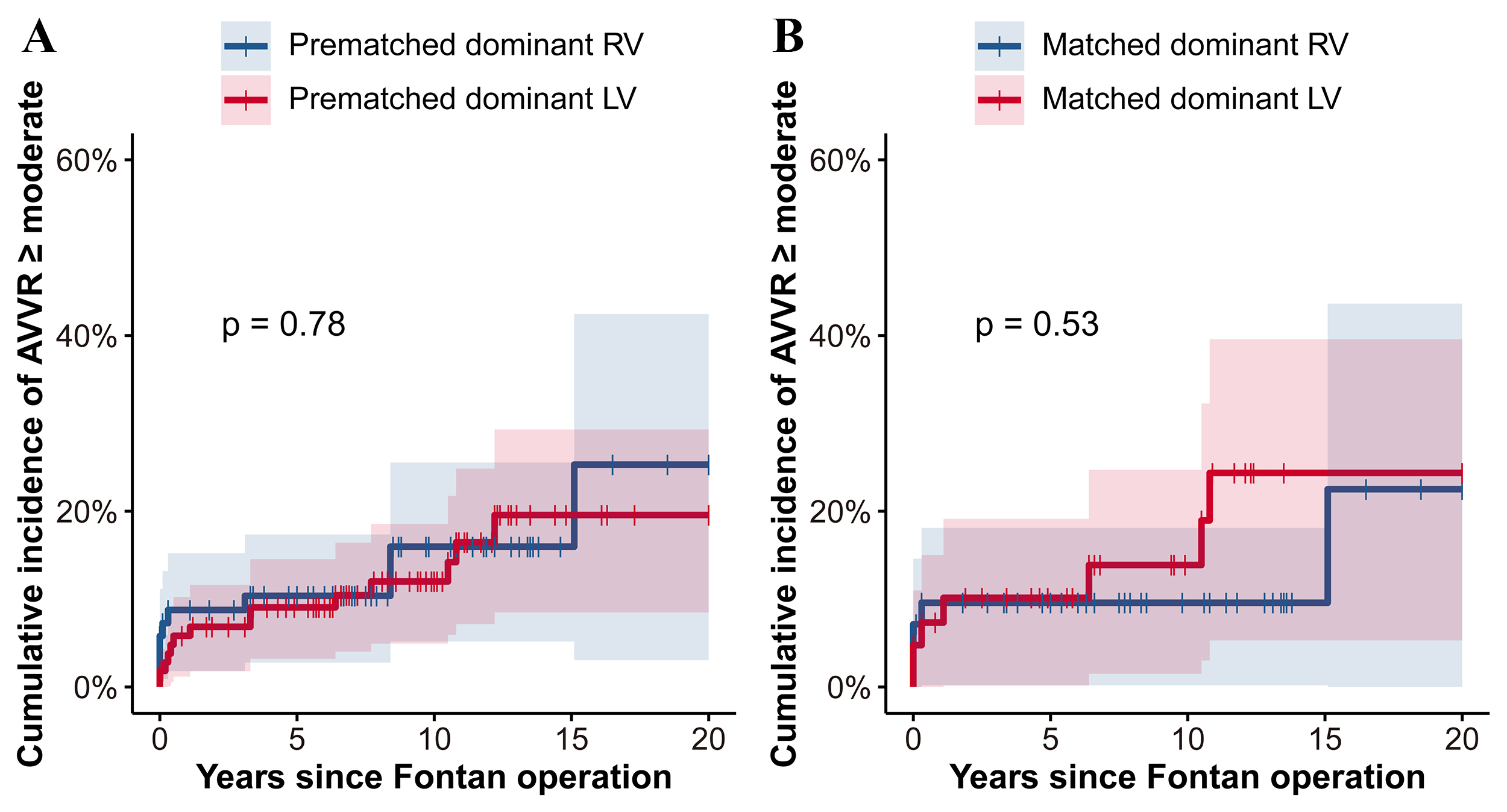

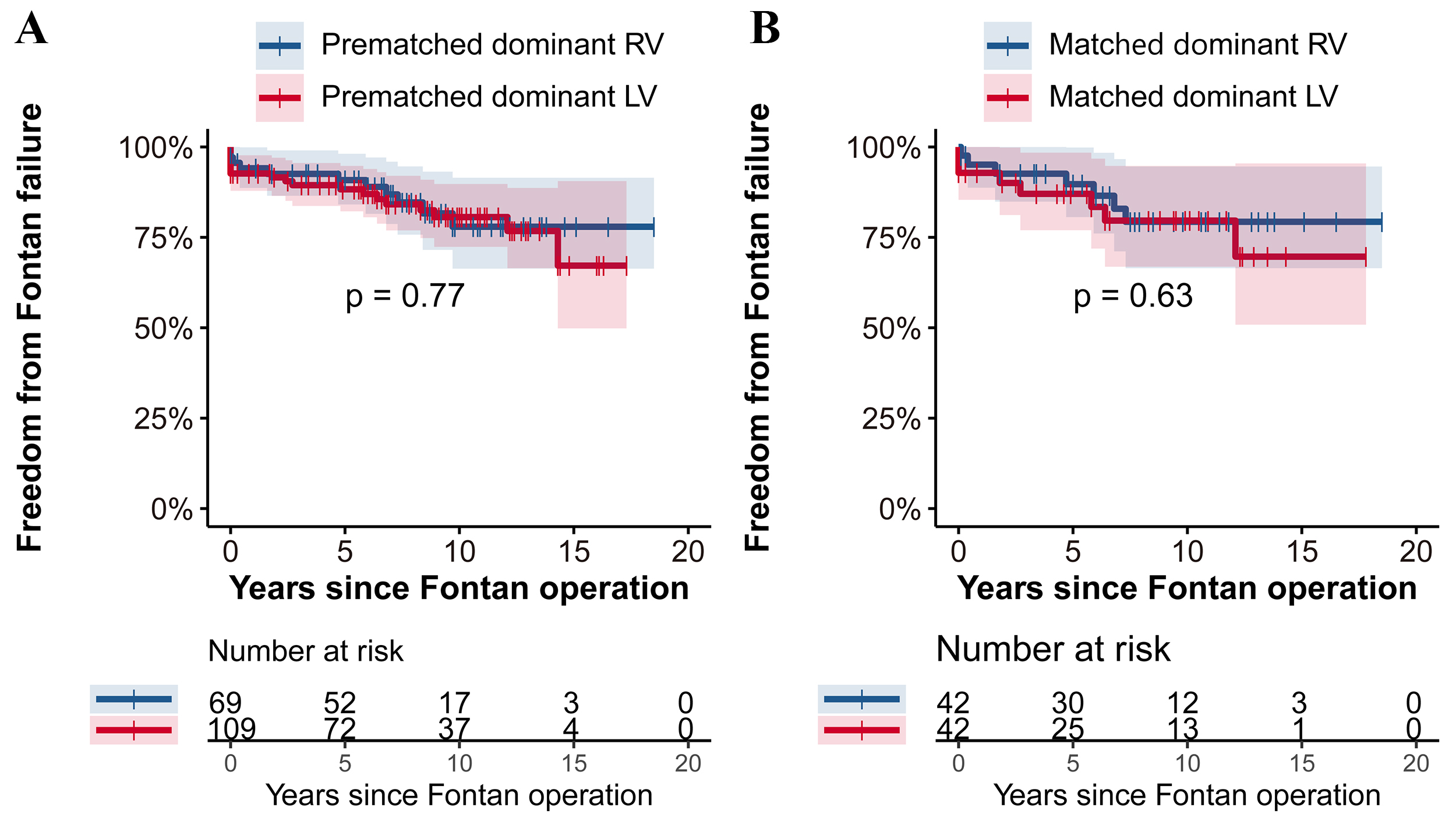

Fig. 3 further illustrates the similarity in outcomes concerning freedom from

Fontan failure between the groups. Pre- and post-matching analyses revealed no

significant differences (p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Freedom from Fontan failure: RV vs. LV group with Log-rank test in the prematched cohort (A) and the matched cohort (B). This figure presents the comparison of freedom from Fontan failure between patients with dominant RV and LV before and after propensity score matching. (A) In the prematched cohort, the freedom from Fontan failure was comparably similar between the RV and LV groups (p = 0.77). (B) The trend continued in the matched cohort (B), where no significant difference in freedom from Fontan failure was observed between the two groups (p = 0.63). RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle.

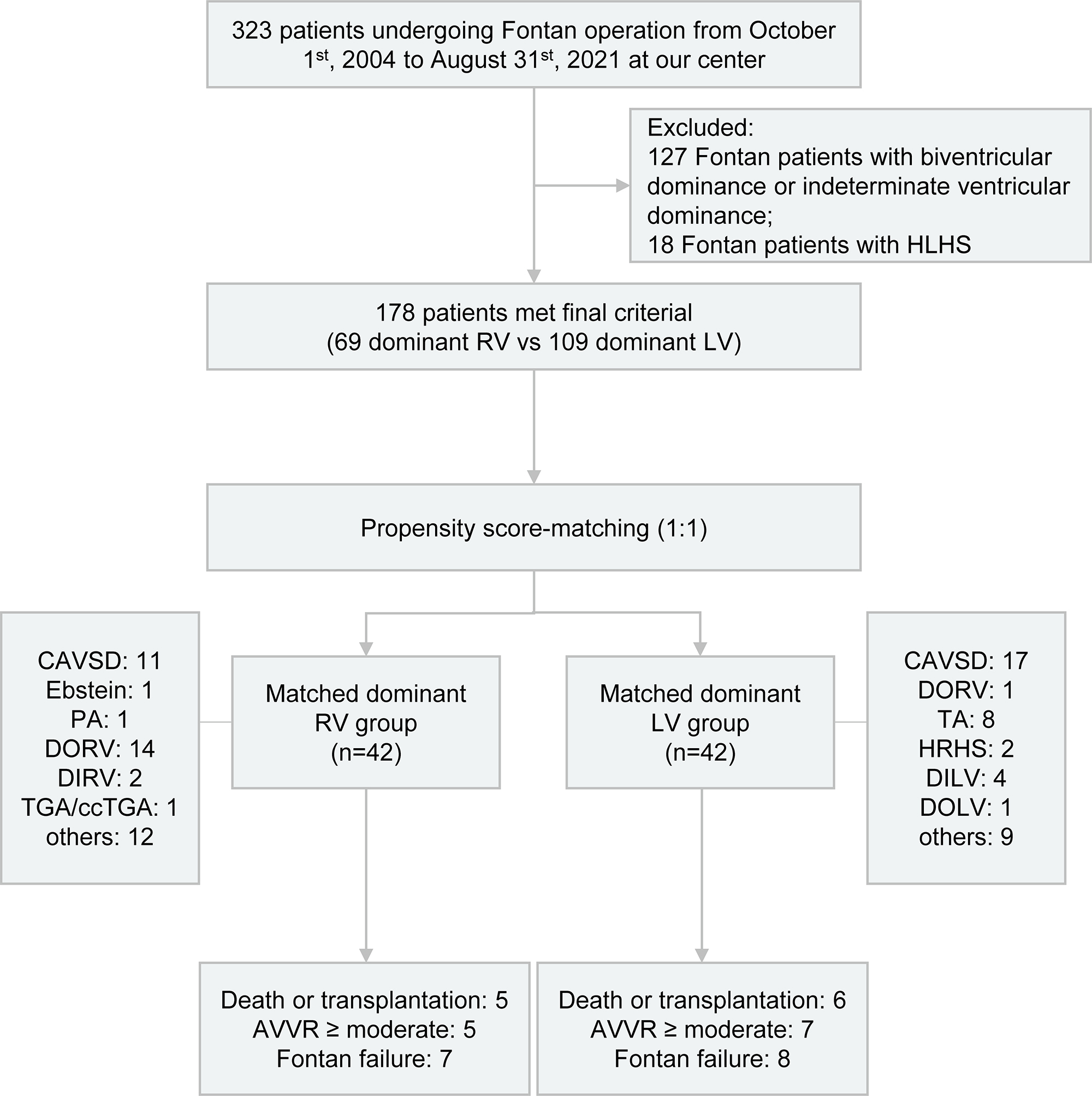

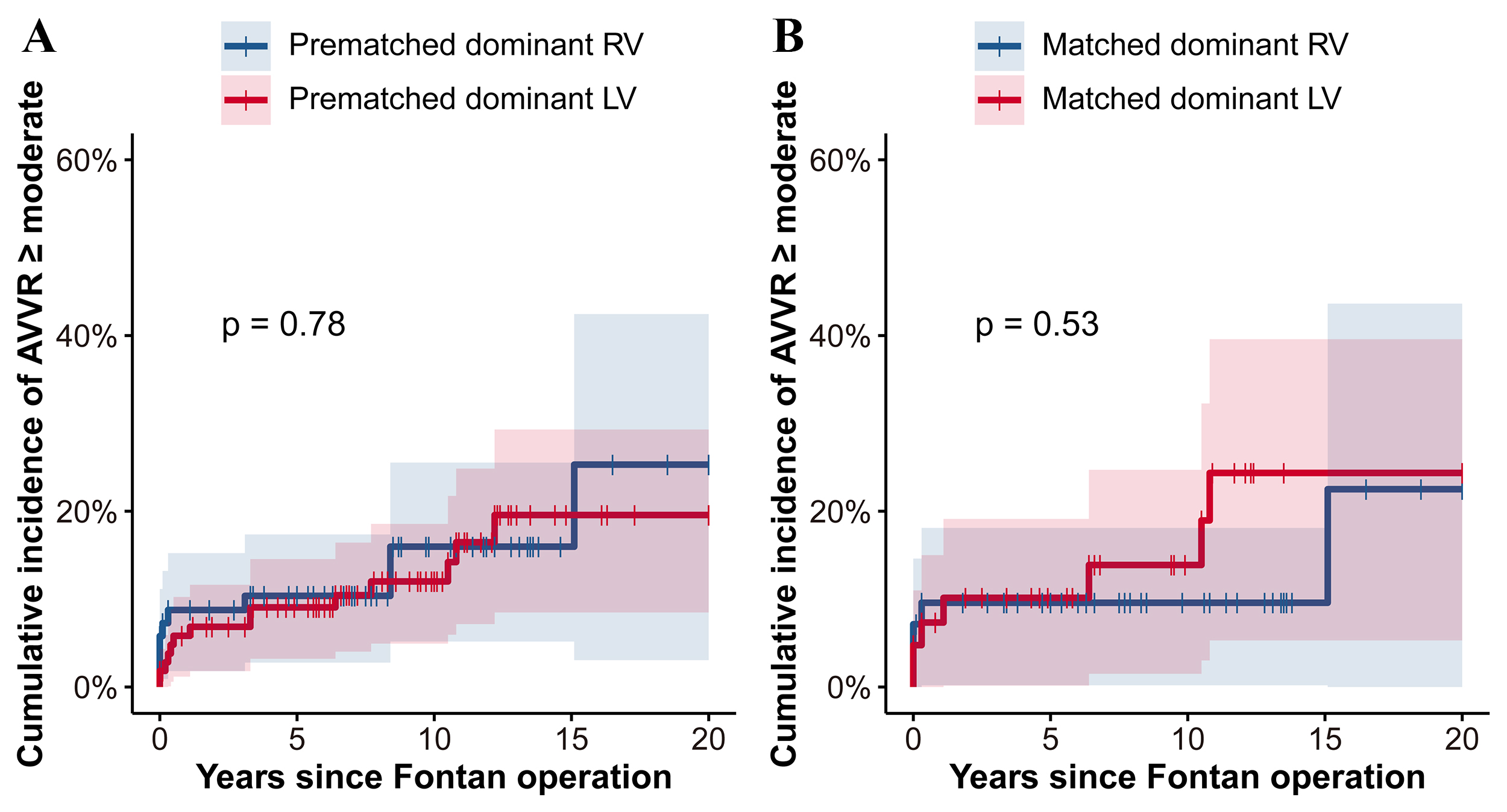

Fig. 4 illustrates the cumulative incidence of of moderate or greater

AVVR

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Cumulative incidence of AVVR

Table 3 outlines the results from univariate and multivariate Cox proportional

hazard analyses identifying predictors of Fontan failure. Significant factors

associated with an increased risk of Fontan failure in the univariate analysis

included atrial isomerism, anomalous pulmonary vein connection, CPB time,

mechanical ventilation time, and length of ICU stay (p

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Dominant RV | 0.894 (0.425–1.881) | 0.768 | 0.559 (0.249–1.257) | 0.159 |

| Atrial isomerism | 3.677 (1.779–7.597) | 2.909 (1.176–7.196) | 0.021 | |

| Dextrocardia | 1.362 (0.413–4.491) | 0.612 | 1.373 (0.385–4.896) | 0.625 |

| Anomalous pulmonary vein connection | 2.693 (1.096–6.621) | 0.031 | 1.432 (0.413–4.962) | 0.571 |

| AVV operation before or at Fontan | 1.650 (0.703–3.872) | 0.250 | 1.070 (0.402–2.852) | 0.892 |

| CPB time, min | 1.006 (1.002–1.010) | 0.001 | 1.001 (0.997–1.005) | 0.490 |

| Mechanical ventilation time, h | 1.004 (1.002–1.006) | 1.010 (1.003–1.018) | 0.007 | |

| Length of ICU stay, d | 1.049 (1.008–1.091) | 0.018 | 0.860 (0.729–1.016) | 0.075 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; RV, right ventricle; AVV, atrioventricular valve; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; ICU, intensive care unit.

The association between RV-dominance and poorer long-term outcomes in Fontan circulation is a subject of ongoing debate. Our study employed PSM to balance patient characteristics between pre- and intra-Fontan status, focusing on those with non-HLHS, to compare outcomes between RV and LV dominance. Our findings revealed that: (1) The cumulative incidence of AVVR was similar between the two groups in both the prematched cohort and the matched cohort. (2) Dominant ventricular morphology did not significantly impact the likelihood of long-term freedom from death or transplantation and Fontan failure in either the prematched or matched cohorts. These results suggest that the ventricular morphology, whether RV or LV dominance, does not decisively influence the long-term success of Fontan circulation in the non-HLHS patient population.

Anatomical and embryological distinctions between the RV and LV, along with differences in AVV, suggest the RV might be more susceptible to pressure-overload when it assumes responsibility for systemic circulation, potentially, leading to or accelerating the occurrence and progression of AVVR [16]. Indeed, previous studies [17] revealed a higher rate of AAVR deterioration and progression AVVR in patients with RV dominance compared to those with LV dominance in Fontan circulation. Of note, instances of moderate or greater AVVR at the time of Fontan operations and subsequent AVV repair or replacement were more common in the dominant RV group. However, specific details regarding AVV morphology in these comparisons remained unclear.

Contrary to these observations, our study found no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of moderate or greater AVVR between the prematched RV and LV dominant groups. Further, after matching patients for similar clinical AVV status, we observed equivalent rates of AVVR across RV and LV dominant Fontan patients. This echoes findings from a recent retrospective study of 174 Fontan patients with atrioventricular septal defect, showing no significant difference of moderate or greater AVVR between the two groups [18]. This suggests that AVV morphology and anatomy may play a more critical role in AVVR development than ventricular dominance itself.

Moreover, in our matched cohorts, the 10-year cumulative incidence of moderate

or greater AVVR was closely matched between the RV and LV dominant groups, at

11%

Our study demonstrates that the long-term outcomes following Fontan operation,

specifically freedom from death or transplantation and freedom from Fontan

failure, do not significantly differ between patients who are RV-dominant and

LV-dominant. In the matched groups, the 10-year freedom from death or

transplantation was 84%

This finding aligns with previous studies that presents varied and often contradictory evidence on the impact of dominant ventricular morphology on long-term outcomes in Fontan circulation [11, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]. For example, Hosein et al. [26] retrospectively analyzed 406 Fontan patients (60% HLHS in the RV-dominant group) during the mean follow-up of 6.1 years, showing that ventricular morphology did not adversely influence short-term or long-term outcomes of Fontan patients. The freedom from death or transplantation at 5 years and 10 years after the Fontan operation was 90% and 86%, respectively, which was consistent with our findings [26]. These consistencies across studies suggest that despite the theoretical implications of ventricular morphology on post-Fontan prognosis, the actual influence may be minimal, underscoring the need for a nuanced understanding of individual patient characteristics and the multifactorial nature of outcomes following Fontan surgery.

In contrast, Moon et al. [11] conducted a retrospective study of 1162

patients with a direct focus on ventricular morphology, with 71% of these

patients classified as RV-dominant with HLHS. With a mean follow-up of 8.3 years,

they concluded that RV dominance impaired long-term outcomes when compared to the

LV-dominant group, potentially due to AVVR deterioration and impaired ventricle

function [11]. Notably, they reported a 10-year transplantation-free survival

rate of 90% in the RV-dominant group, significantly lower than 92% in the

LV-dominant group (p

Several factors may account for these contrasting results. First, the inherent heterogeneity among Fontan patients, who present with a wide variety of congenital cardiac structural abnormalities, may contribute to these discrepancies. Indeed, many previous studies showed an imbalance in baseline anatomic characteristics between the two groups [11, 18]. Our application of PSM aimed to reduce the selection bias, resulting in outcomes that were similar between groups. This suggests the possibility that inherent cardiac structural abnormalities, rather than RV-dominant morphology influence long-term outcomes. Secondly, the incidence of moderate or greater AVVR, a factor known to affect outcomes due to its contribution to volume overloading, ventricular dilation, and increased central venous pressure, was maintained between groups in our study [5]. This similarity in AVVR progression supports the idea that ventricular dominance may not be the primary determinant of outcomes. Thirdly, follow-up durations in our study were slightly shorter than in Moon’s study, with 8.0 years for RV dominance and 6.5 years for LV dominance in our study vs. 8.3 years in Moon’s study [11]. It’s possible that the systemic circulation supported by the dominant RV could remain in a compensatory state within this timeframe, leading to outcomes that did not significantly differ from those of the LV-dominant group. Lastly, our exclusion of HLHS patients, who are generally at higher risk for adverse outcomes, may have minimized the perceived disadvantages of the RV-dominant group, contributing to our findings of similar outcomes [12]. The exclusion criteria perhaps weakened the disadvantage of the RV-dominant group, partially contributing to the finial similar results. Regardless, despite differing perspectives in the literature, our research suggests that the long-term prognosis for dominant RV and LV in non-HLHS Fontan patients may be similar, at least within the duration of our follow-up period.

There were several limitations in our study. First, this is a single-center study with a retrospective design, which may limit the applicability of the findings to broader populations. Secondly, the relatively small sample size of Fontan patients both before and after PSM could diminish the statistical power of our results. Finally, although cardiac magnetic resonance imaging remains the gold standard for determining functional ventricular dominance through quantification of cardiac output and stroke volume, it was not typically utilized before Fontan operations in our hospital due to the high cost and long waiting periods for appointments. Consequently, ventricular dominance was assessed using echocardiography, a method that may not provide an ideal assessment for all patients. This potentially led to the exclusion of some patients categorized as having indeterminate or biventricular morphology from this analysis.

The RV dominance does not seem to adversely influence the long-term outcomes in non-HLHS Fontan circulation. The likelihood of experiencing moderate or greater AVVR, transplantation-free survival, and avoiding Fontan failure were similar between RV and LV dominant groups within in the same pre- and intra-Fontan conditions.

SV, single ventricle; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; PSM, propensity score matching; AVVR, atrioventricular valve regurgitation; AVV, atrioventricular valve.

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

HYY and JMC designed the research. HW, JRM, and LJH performed the research. TT, WX, MT, ZCT, and YL were in charge of data collection. XL, XBL, HYY, and JMC provided help and advice on research. HW and JRM analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital Ethics Committee on 17th September 2019 (No. GDREC2019338H(R2)). The individual informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design of the study.

We appreciated the helpful comments of each member from Zhuang’s and Chen’s group.

This study was supported by the project of National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFC2407406), Stability Support for Innovation Capacity Building of Research institutions in Guangdong Province in 2022 (KD022022015) and Science and Technology Fundation of Guangzhou Health (No. 2023A031004).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.