1 Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 1A8, Canada

2 Departments of Medicine and Biochemistry, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, ON N6A 5C1, Canada

3 Department of Family and Community Medicine, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5G 1V7, Canada

4 Departments of Laboratory Medicine and Medicine, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec, Université Laval, Québec, QC G1V 4G2, Canada

5 Amgen Canada Inc., ON L5N 0A4, Canada

6 Centre for Cardiovascular Innovation, Division of Cardiology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V5Z 1M9, Canada

Abstract

Elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is a major causal factor

for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), the leading cause of

mortality worldwide. Statins are the recommended first-line lipid-lowering

therapy (LLT) for patients with primary hypercholesterolemia and established

ASCVD, with LLT intensification recommended in the substantial proportion of

patients who do not achieve levels below guideline-recommended LDL-C thresholds

with statin treatment alone. The proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

inhibitor monoclonal antibody evolocumab has demonstrated significant LDL-C

reductions of

Keywords

- evolocumab

- proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor

- lipid-lowering therapy

- low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)

- atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)

- cardiovascular outcomes

Chronically elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) drives the

development and manifestation of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD),

the leading cause of mortality worldwide, responsible for approximately one-third

of all deaths [1]. For secondary ASCVD prevention, international guidelines

recommend lipid-lowering therapy (LLT) to reduce LDL-C below target thresholds,

generally either

Statins are the recommended first-line LLT in patients who require lipid lowering [2, 3, 4, 5], yet real-world evidence (RWE) consistently reveals a substantial proportion of patients at high risk of or with established ASCVD do not achieve levels below guideline-recommended LDL-C thresholds despite maximally tolerated statin therapy [8, 9, 10]. In these patients, LLT intensification with non-statin therapies as recommended by international guidelines may include ezetimibe and/or proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor (PCSK9i) [2, 3, 4, 5], among other effective pharmacological options with varying mechanisms of action and efficacy now available (Table 1, Ref. [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]).

| LLT | Target | CV outcomes trial and treatment arms | Patient population | Mean LDL-C reduction shown in CV outcomes trial | Relative and absolute reduction in CV death, MI or stroke in the ASCVD population |

| Statins [11, 12, 13] | HMG-CoA reductase | TNT | N = 10,001 stable ASCVD (LDL-C |

•High intensity: |

RRR: 20.1% at 5 years |

| •Moderate intensity: 30% to 50% | ARR: 2.2% at 5 years | ||||

| •Intensive therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg | •Low intensity: |

||||

| •Moderate regimen of atorvastatin 10 mg | |||||

| Ezetimibe [14] | NPC1L1 | IMPROVE-IT | N = 18,144 patients hospitalized for ACS within past 10 days (LDL-C |

24% | RRR: 5.7% at 7 years |

| •Simvastatin 40 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg | ARR: 2.0% at 7 years | ||||

| •Placebo (simvastatin 40 mg) | |||||

| Bempedoic acid [15] | ATP-citrate lyase | CLEAR OUTCOMES | N = 13,970 statin-intolerant with or at high-risk of ASCVD | 21.1% | RRR: 13.6% at 5 years |

| •Bempedoic acid 180 mg | ARR: 1.3% at 5 years | ||||

| •Placebo | |||||

| Evolocumab [16] | Plasma PCSK9 | FOURIER | N = 27,564 ASCVD and receiving statin therapy (LDL-C |

59% | RRR: 20.3% at 2.2 years |

| •Evolocumab (either 140 mg Q2W or 420 mg QM) |

ARR: 1.5 % at 2.2 years | ||||

| •Placebo (maximum tolerated statin) | |||||

| Alirocumab [17] | Plasma PCSK9 | ODYSSEY | N = 18,924 patients with ACS 1–12 months earlier receiving high-intensity statin therapy (LDL-C |

54.7% | RRR: 14.4% at 4 years |

| •Alirocumab 75 mg | ARR:1.6% at 4 years | ||||

| •Placebo (maximum tolerated statin) | |||||

| Inclisiran [18, 19] | PCSK9 mRNA | ORION-4 | N = |

44.2% |

Not yet reported |

| •Inclisiran 300 mg | |||||

| •Placebo |

ApoB, apolipoprotein B; ARR, absolute risk reduction; ACS, acute coronary

syndrome; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; ATP, adenosine

triphosphate; CV, cardiovascular; FOURIER, Further Cardiovascular

Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects

With Elevated Risk; IMPROVE-IT, IMProved

Reduction of Outcomes, Vytorin Efficacy

International Trial; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; HMG-CoA,

The two available PCSK9i monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), alirocumab and evolocumab, have been

approved globally for 8 years at the time of this review. Both have demonstrated

remarkable LDL-C reductions of ~60% in adult patients with

hyperlipidemia on background statin therapy (

PCSK9 is a serine protease that is predominantly synthesized and secreted by hepatocytes [24]. The only known human function of PCSK9 is to regulate the cell membrane low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor (LDLR) in the liver [24]. Following free PCSK9 binding, the LDLR is degraded instead of being recycled, leading to higher circulating LDL-C levels [24]. The potential role of PCSK9 in LDL-C metabolism was first recognized in 2003 via genetic mapping in patients with autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia [25]. Subsequent case reports of healthy patients homozygous for loss-of-function variants and LDL-C levels of ~0.4 mmol/L (15 mg/dL) demonstrated the crucial role of PCSK9 in LDL metabolism [26]. Indeed, in an analysis of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study in 2006, patients carrying a nonsense, or loss-of-function, variant (specifically either PCSK9 p.Tyr142Ter or p.Cys679Ter) had 28% lower LDL-C as well as significantly lower total cholesterol and triglycerides compared with non-carriers [27]. During the 15-year follow-up period, only ~1% of carriers experienced a coronary event compared with ~10% of non-carriers [27].

Several clinical trials studying the safety and efficacy of evolocumab were

launched in 2010 (Table 2, Ref. [11, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32]; Table 3, Ref. [11, 33]; Table 4,

Ref. [11, 34, 35]; Table 5, Ref. [11, 16, 36]; Table 6, Ref. [11, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43]; Table 7, Ref. [11, 44, 45, 46]) [47], taking evolocumab from bench to bedside in

~7 years. Over the years, the program of evolocumab data

generation, known as the Program to Reduce LDL-C and Cardiovascular Outcomes

Following Inhibition of PCSK9 In Different Populations (PROFICIO), has grown to

include 50 clinical trials and RWE studies to date, enrolling

| Study name, publication year | Study rationale | N (n on evolocumab) | Trial population | Baseline LDL-C | Background LLT |

Endpoint (Weeks) | Statistically significant (p |

| MENDEL-2, 2014 [28] | Evaluate 2 evolocumab dosing regimens as monotherapies | 614 (306) | Adult patients with hypercholesterolemia (LDL-C |

140 mg Q2W: 3.67 mmol/L (142 mg/dL) | None | 12 | 140 mg Q2W: 57.0% 420 mg QM: 56.1% |

| 420 mg QM: 3.72 mmol/L (144 mg/dL) | |||||||

| DESCARTES, 2014 [29] | Evaluate longer-term use of evolocumab | 901 (599) | Adult patients with hypercholesterolemia (LDL-C |

2.69 mmol/L (104.2 mg/dL) | •None: 74 | 52 | 50.1% |

| •Atorvastatin 10 mg: 254 | |||||||

| •Atorvastatin 80 mg: 145 | |||||||

| •Atorvastatin 80 mg + ezetimibe: 126 | |||||||

| LAPLACE-2, 2014 [30] | Evaluate 2 evolocumab dosing regimens in combination with different statin intensities | 2067 (1117) | Adult patients with hypercholesterolemia and mixed dyslipidemia (LDL-C |

2.97 mmol/L (114.9 mg/dL) | High-intensity statin: 442 | 12 | High-intensity statin patients: |

| Atorvastatin 80 mg: 61.8% | |||||||

| Rosuvastatin 40 mg: 58.9% | |||||||

| Moderate-intensity statin: 675 | Moderate-intensity statin patients: | ||||||

| Rosuvastatin 5 mg: 60.1% | |||||||

| Atorvastatin 10 mg: 61.6% | |||||||

| Simvastatin 40 mg: 65.9% | |||||||

| YUKAWA-2, 2016 [31] | Evaluate 2 evolocumab dosing regimens in combination with atorvastatin in Japanese patients | 404 (202) | Adult Japanese patients with hypercholesterolemia/mixed dyslipidemia and high cardiovascular risk (LDL-C |

2.82 mmol/L (109 mg/dL) | Atorvastatin: 202 (all patients) | 12 | 140 mg Q2W: 75.9% |

| 420 mg QM: 66.9% | |||||||

| Phase II pooled analysis (time-averaged), 2022 [32] | Conduct a time-averaged analysis of cumulative LDL-C lowering with evolocumab | 372 (189) | Adult patients with hypercholesterolemia | 140 mg Q2W: 3.43 mmol/L (132.7 mg/dL) | Statin and/or ezetimibe | 9–12 | 140 mg Q2W: 67.6% |

| •Non-intensive statin: 93 | |||||||

| •Intensive statin: 34 | |||||||

| 420 mg QM: 3.65 mmol/L (141.4 mg/dL) | •Ezetimibe: 14 | 420 mg QM: 65.0% |

DESCARTES, Durable Effect of PCSK9 Antibody CompARed WiTh PlacEbo Study; LAPLACE-2, LDL-C Assessment With PCSK9 MonoclonaL Antibody Inhibition Combined With StatinThErapy-2; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; MENDEL-2, Monoclonal Antibody Against PCSK9 to Reduce Elevated LDL-C in Subjects Currently Not Receiving Drug Therapy for Easing Lipid Levels-2; Q2W, every 2 weeks; QM, every month; YUKAWA-2, StudY of LDL-Cholesterol Reduction Using a Monoclonal PCSK9 Antibody in Japanese Patients With Advanced Cardiovascular Risk; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

| Study name, publication year | Study rationale | N (n on evolocumab) | Trial population | Baseline LDL-C | Background LLT |

Endpoint (Weeks) | Statistically significant (p |

| THOMAS-1, 2016 [33] | Evaluate users’ ability to self-administer evolocumab in a home-use setting | 149 (149) | Adult patients with hypercholesterolemia or mixed dyslipidemia (LDL-C |

3.02–3.05 mmol/L (116.9–118.1 mg/dL) | Statin |

6 | 63.4% |

| •Statin: 149 (all patients) | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe: 9 | |||||||

| THOMAS-2, 2016 [33] | Evaluate users’ ability to self-administer evolocumab in a home-use setting | 164 (164) | Adult patients with hypercholesterolemia or mixed dyslipidemia (LDL-C |

2.98–3.03 mmol/L (115.3–117.3 mg/dL) | Statin |

Mean of weeks 10 and 12 | 67.9% |

| •Statin: 164 (all patients) | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe: 14 |

LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

| Study name, publication year | Study rationale | N (n on evolocumab) | Trial population | Baseline LDL-C | Background LLT |

Endpoint (Weeks) | Statistically significant (p |

| GLAGOV, 2016 [34] | Evaluate whether LDL-C lowering with evolocumab results in greater change from baseline in PAV | 968 (484) | Adult patients with coronary angiography (LDL-C |

2.39 mmol/L (92.5 mg/dL) | •High-intensity statin: 280 | 78 | 60.8% |

| •Moderate-intensity statin: 196 | |||||||

| •Low-intensity statin: 2 | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe: 9 | |||||||

| HUYGENS, 2022 [35] | Evaluate whether evolocumab inhibition in addition to high-intensity statin therapy favorably modifies coronary plaque phenotype | 164 (80) | Adult patients with non-ST segment elevation MI (LDL-C |

3.62 mmol/L (140.0 mg/dL) | Statin and/or ezetimibe | 50 | 81.4% |

| •High-intensity statin: 63 | |||||||

| •Moderate-intensity statin: 11 | |||||||

| •Low-intensity statin: 1 | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe: 1 |

GLAGOV, GLobal Assessment of Plaque ReGression with a PCSK9 AntibOdy as Measured by IntraVascular Ultrasound; HUYGENS, High-ResolUtion Assessment of CoronarY Plaques in a Global Evolocumab RaNdomized Study; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; MI, myocardial infarction; PAV, percent atheroma volume; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9.

| Study name, publication year | Study rationale | N (n on evolocumab) | Trial population | Baseline LDL-C | Background LLT |

Endpoint (Weeks) | Statistically significant (p |

| FOURIER, 2017 [16] | Evaluate the effect of evolocumab on the risk of CV death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization | 27,564 (13,784) | Adult patients with ASCVD and LDL-C |

2.4 mmol/L (92 mg/dL) | Statin and/or ezetimibe | 48 | 59% |

| •High-intensity statin: 9585 | |||||||

| •Moderate-intensity statin: 4161 | |||||||

| •Low- or unknown intensity statin: 38 | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe: 726 | |||||||

| FOURIER-OLE, 2022 [36] | Evaluate long-term safety, tolerability, lipids levels, and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events with continued evolocumab exposure | 6635 (3355) | Adult patients with ASCVD and LDL-C |

2.35 mmol/L (91 mg/dL) in parent FOURIER | Statin and/or ezetimibe | 12 | 58.4% |

| •High-intensity statin: 2584 | |||||||

| •Moderate-intensity statin: 758 | |||||||

| •Low- or unknown statin intensity: 13 | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe: 200 |

ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CV, cardiovascular; FOURIER, Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; MI, myocardial infarction; OLE, open label extension; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9.

| Study name, publication year | Study rationale | N (n on evolocumab) | Trial population | Baseline LDL-C | Background LLT |

Endpoint (Weeks) | Statistically significant (p |

| RUTHERFORD-2, 2015 [37] | Evaluate 2 dosing regimens of evolocumab in subjects with HeFH | 331 (221) | Adult patients with HeFH (LDL-C |

140 mg Q2W: | Statin and/or ezetimibe: 221 (all patients) | 12 | 140 mg Q2W: 61.3% |

| 4.2 mmol/L (162.4 mg/dL) | |||||||

| 420 mg QM: | 420 mg QM: 55.7% | ||||||

| 4.0 mmol/L (154.68 mg/dL) | |||||||

| GAUSS-3, 2016 [38] | Compare effectiveness and tolerability of evolocumab and ezetimibe in patients with statin-induced muscle symptoms | 491 (145) | Adult patients with a history of statin intolerance and not at LDL-C goal (LDL-C |

5.66 mmol/L (218.8 mg/dL) | None | 24 | 52.8% |

| BANTING, 2019 [39] | Evaluate the effect of evolocumab in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus and high cholesterol | 421 (281) | Adult patients with type 2 diabetes and hypercholesterolemia/mixed dyslipidemia (variable LDL-C criteria) | 2.81 mmol/L (108.7 mg/dL) | •High-intensity statin: 146 | 12 | 54.3% |

| •Moderate-intensity statin: 133 | |||||||

| EVOPACS, 2019 [40] | Evaluate evolocumab administered in-hospital in patients presenting with ACS | 308 (155) | Adult patients hospitalized for acute coronary syndromes with elevated LDL-C beyond guideline-recommended target | 3.61 mmol/L (139.6 mg/dL) | Statin and/or ezetimibe | 8 | 77.1% |

| •High-intensity statin: 18 | |||||||

| •Low- or moderate-intensity statin: 13 | |||||||

| •No statin: 124 | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe: 6 | |||||||

| HAUSER, 2020 [41] | Evaluate safety and efficacy of evolocumab in pediatric subjects aged 10–17 years diagnosed with HeFH | 157 (104) | Pediatric patients (10–17 years) with HeFH (LDL-C |

4.78 mmol/L (185.0 mg/dL) | Statin and/or ezetimibe | 24 | 44.5% |

| •High-intensity statin: 19 | |||||||

| •Moderate-intensity statin: 63 | |||||||

| •Low- or unknown intensity statin: 22 | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe: 13 | |||||||

| EVACS, 2020 [42] | Evaluate impact of evolocumab on early postinfarct atherogenic lipoprotein trajectories in patients with ACS | 57 (30) | Adult patients with non-ST segment elevation MI and troponin I |

2.37 mmol/L (91.5 mg/dL) | •All patients received high-intensity statin unless contraindicated | 4 (day 30) | 31% |

| BEIJERINCK, 2020 [43] | Evaluate evolocumab efficacy and tolerability in HIV-positive patients | 464 (310) | Adult patients with HIV with hypercholesterolemia/mixed dyslipidemia (LDL-C |

3.45 mmol/L (133.3 mg/dL) | None, or statin and/or ezetimibe | 24 | 56.9% |

| •High-intensity statin: 95 | |||||||

| •Moderate-intensity statin: 137 | |||||||

| •No statin: 61 | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe: 53 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; EVACS, EVolocumab in Acute Coronary Syndrome; EVOPACS, EVOlocumab for Early Reduction of LDL-Cholesterol Levels in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes; GAUSS-3, Goal Achievement After Utilizing an Anti-PCSK9 Antibody in Statin Intolerant; HAUSER, Trial Assessing Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of PCSK9 InHibition in PediAtric SUbjectS With GenEtic LDL DisordeRs; HeFH, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; MI, myocardial infarction; Q2W, every 2 weeks; QM, every month; RUTHERFORD-2, RedUction of LDL-C With PCSK9 InhibiTion in HEteRozygous Familial HyperchOlesteRolemia Disorder Study-2; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9; BANTING, EvolocumaB EfficAcy aNd SafeTy IN Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on BackGround Statin Therapy; BEIJERINCK, EvolocumaB Effect on LDL-C Lowering in SubJEcts with Human Immunodeficiency VirRus and INcreased Cardiovascular RisK.

| Study name, publication year | Study rationale | N (n on evolocumab) | Trial population | Baseline LDL-C | Background LLT |

Endpoint (Weeks) | Statistically significant (p |

| HEYMANS, 2022 [44] & 2023 [45] | Review evolocumab effectiveness and safety in European patients in a real-world setting | 1951 (all patients) | Adult hyperlipidemic patients receiving evolocumab (LDL-C criteria varied based on region) | 3.98 mmol/L (153.9 mg/dL) | •Neither statin, nor ezetimibe: 799 | 12 (3 months) | 58% |

| •Any statin: 840 | |||||||

| •Statin without ezetimibe: 234 | |||||||

| •Statin with ezetimibe: 605 | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe without statin: 312 | |||||||

| ZERBINI, 2023 [46] | Review evolocumab effectiveness and safety in patients across Canada, Mexico, Colombia, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in a real-world setting | 578 (all patients) | Adult hyperlipidemic patients receiving evolocumab (LDL-C |

3.4 mmol/L (131.5 mg/dL) | •Statin: 437 | Up to 52 (12 months) | 70.2% |

| •Ezetimibe without statin: 39 | |||||||

| •Ezetimibe + statin: 168 | |||||||

| •Bile acid sequestrant: 16 | |||||||

| •Other LLT (EPACOR, fibrates, niacin): 25 |

HEYMANS, CHaractEristics of HYperlipidaeMic PAtieNts at Initiation of Evolocumab and Treatment PatternS; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; ZERBINI, MultiZonal ObsERvational Study Conducted By ClinIcal Practitioners on Evolocumab Use iN Subjects With HyperlipIdemia; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Evolocumab is administered subcutaneously, with a recommended dose of either 140 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) or 420 mg once monthly (QM) [20]. It can be administered using a prefilled syringe or prefilled autoinjector, and is intended for patient self-administration or administration by a caregiver [20]. In the phase III Trial for HOMe-use of prefilled Auto-injector pen and 3.5 mL Personal Injector in AMG 145 administrationS (THOMAS)-I and THOMAS-II studies (Table 3), patients were confirmed to be successful at self-administering evolocumab in both the clinic and at-home settings, regardless of the dosing schedule or injection device [33].

Following a single subcutaneous dose of evolocumab (140 mg or 420 mg)

administered to healthy adults, peak circulating drug concentrations are reached

in 3–4 days, with an estimated absolute bioavailability of 72% and half-life of

11–17 days [20, 50]. Evolocumab exerts even more rapid pharmacodynamic effects,

with 100% PCSK9 suppression within 4 hours of administration and reductions in

LDL-C observed as early as day 1 in clinical trials [20, 42, 50]. Following a

single 420 mg intravenous (IV) dose of evolocumab, the mean systemic (

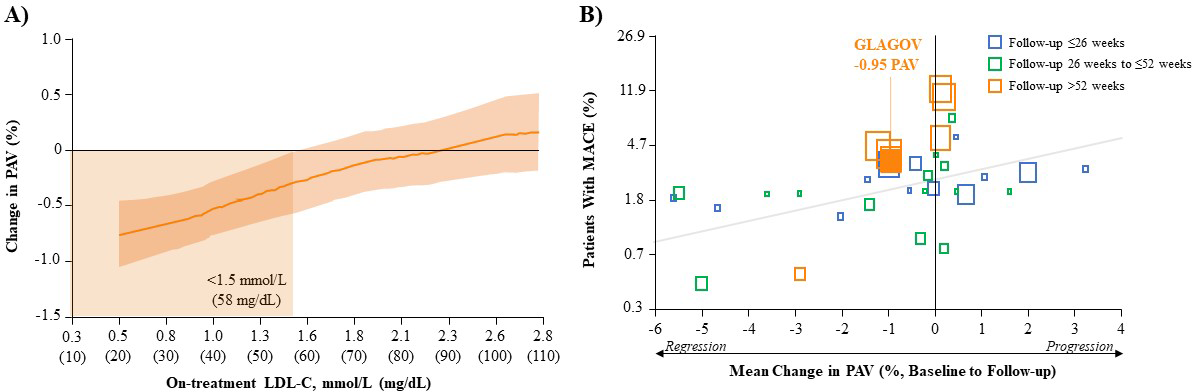

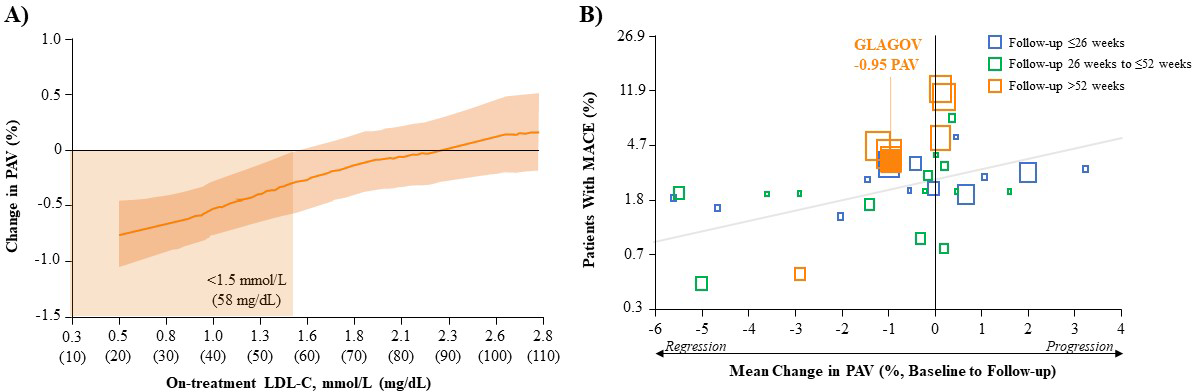

In addition to marked reductions in LDL-C, imaging studies have demonstrated the

efficacy of evolocumab at the level of coronary plaque [34, 35, 52]. In the phase

III GLobal Assessment of Plaque ReGression with a

PCSK9 AntibOdy as Measured by IntraVascular Ultrasound (GLAGOV) (Table 4) study in patients with angiographic

CAD, LDL-C reductions from baseline after 78 weeks of evolocumab (+statin) were

linearly associated with reductions in the percent atheroma (atherosclerotic

plaque) volume (PAV) (Fig. 1A, Ref. [34]). The clinical significance of this is clear

from a comprehensive systematic review and meta-regression analysis of LLT trials

representing data from over 6000 patients, including some on evolocumab, which

showed that for every 1% reduction in mean PAV, there is a ~20%

reduction in the risk of major CV events (Fig. 1B) [53]. In the GLAGOV study,

evolocumab (+statin) reduced PAV by an absolute 0.95% from baseline and resulted

in a greater proportion of patients with plaque regression compared with placebo

(+statin; 64.3% vs. 47.3%, respectively) [34]. Interestingly, further analysis

showed that achieving LDL-C

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Correlation of LDL-C reduction, change in PAV and MACE outcomes. (A) Post-hoc Analysis of the Relationship Between Achieved LDL-C and Change in PAV After Evolocumab (+Statin) Treatment in GLAGOV. Local regression (LOESS) curve illustrating post-hoc analysis of the association (with 95% confidence intervals) between the achieved LDL-C levels and change in PAV in all patients undergoing serial IVUS evaluation. Curve truncated at 0.5 mmol/L and 2.8 mmol/L (20 and 110 mg/dL) owing to the small numbers of values outside that range. (Figure permission obtained from [34]). (B) Association Between Mean Change in PAV and MACE in Various LLT Trials. Each square represents a single study arm. The size of the square is proportional to the sample size of that study arm. The MACE proportion was converted to log odds and a constant 0.5 was added to zero counts to allow the conversion of log odds. The regression line is based on the adjusted mixed-effects logistic regression model. (Figure permission obtained from [53]). GLAGOV, GLobal Assessment of Plaque ReGression with a PCSK9 AntibOdy as Measured by IntraVascular Ultrasound; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event (myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, unstable angina or all-cause mortality); PAV, percent atheroma volume.

Plaque stability can be characterized by the thickness of the thin-cap

fibroatheroma, with an inverse relationship between the thickness of the fibrous

cap covering the lipid plaque and risk of plaque rupture [55]. Plaques at high

risk of rupture have a fibrous cap thickness

The potential for the effects of evolocumab on LDL-C to translate into CV

benefits was explored in the phase III FOURIER trial (Table 5), the largest

dedicated CV outcomes trial with a LLT to date (N = 27,564) [16]. FOURIER was an

event driven trial that investigated the efficacy and safety of evolocumab vs.

placebo added to high- or moderate-intensity statin therapy in patients with

clinically evident ASCVD with an LDL-C

| Lipid parameter | Mean change from baseline, % | Evolocumab vs. Placebo, % | p-value | |

| Placebo | Evolocumab | |||

| LDL-C | NR | NR | –59.0 | |

| Non-HDL-C | 0.4 | –51.2 | –51.6 | |

| Triglycerides | –0.7 | –16.2 | –15.5 | |

| ApoB | 2.7 | –46.0 | –48.7 | |

| Lp(a) | 0.0 | –26.9 | –26.9 | |

ApoB, apolipoprotein B; FOURIER, Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); NR, not reported; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9.

Findings from the FOURIER trial highlighted the benefit of reducing LDL-C to

levels lower than those shown in previous LLT trials, with a median achieved

LDL-C of 0.78 mmol/L (30.2 mg/dL) [16]. Importantly, this significant LDL-C

reduction with evolocumab resulted in reduced CV events which can be visualized

in the Kaplan-Meier curved from the FOURIER, which showcase a 15% reduction in

the risk of the prespecified primary composite endpoint of CV death, MI, stroke,

hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization (Fig. 2A, Ref.

[16]), and a 20% reduction in the risk of the key secondary composite endpoint

of major adverse CV events (MACE; i.e., CV death, MI, or stroke; Fig. 2B, Ref. [16]).

Differences in CV risk between the evolocumab and placebo groups were observed

early, at approximately 6 months, and increased over time. The Kaplan-Meier

curves from the FOURIER analysis demonstrate the magnitude of MACE risk reduction

was 16% during the first year that increased to 25% beyond the first year

post-evolocumab initiation, collectively highlighting a rapid onset of MACE risk

reduction that grew over time, considering the relatively short duration of

follow-up (Supplementary Fig. 4 in [16]). Further, MACE risk reductions were

consistent across levels of background statin intensity and ezetimibe use and

regardless of baseline LDL-C. Among patients in the top quartile for baseline

LDL-C (n = 6829), evolocumab reduced median LDL-C from 3.3 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) to

1.1 mmol/L (43 mg/dL) and the risk of MACE by 17%. Among patients in the lowest

quartile for baseline LDL-C (n = 6961), evolocumab reduced median LDL-C from 1.9

mmol/L (73 mg/dL) to 0.57 mmol/L (22 mg/dL) and the risk of MACE by 22%.

Further, in a subset of patients who had baseline LDL-C

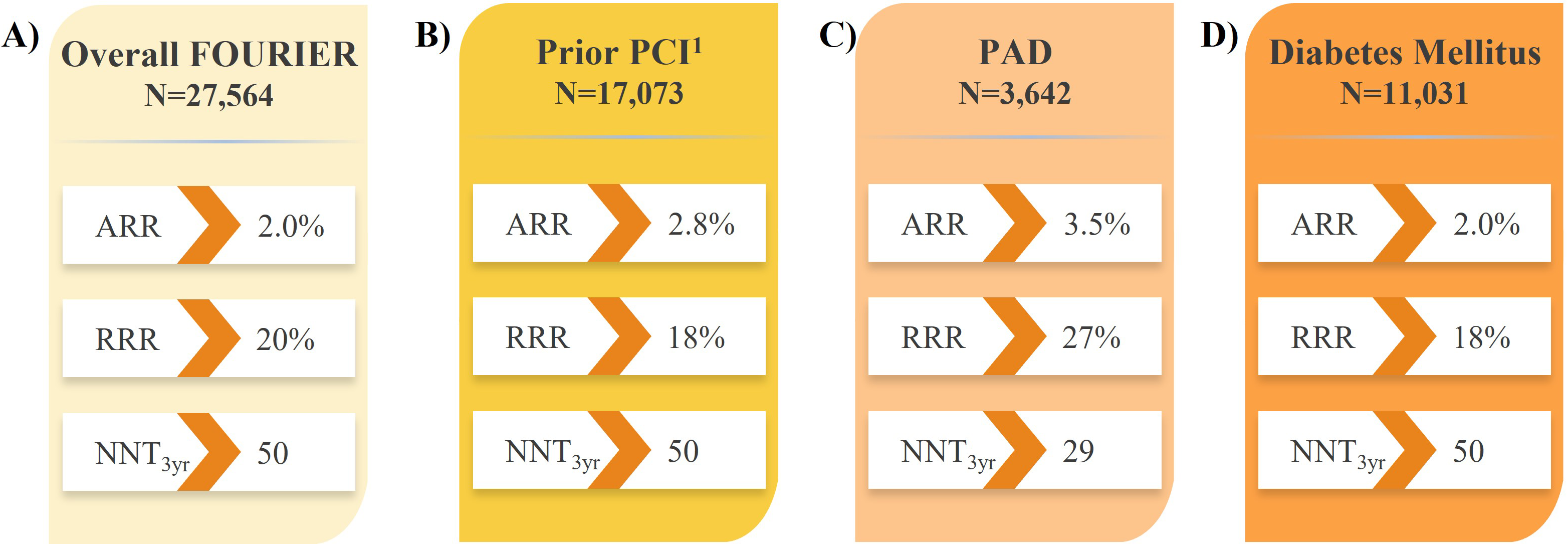

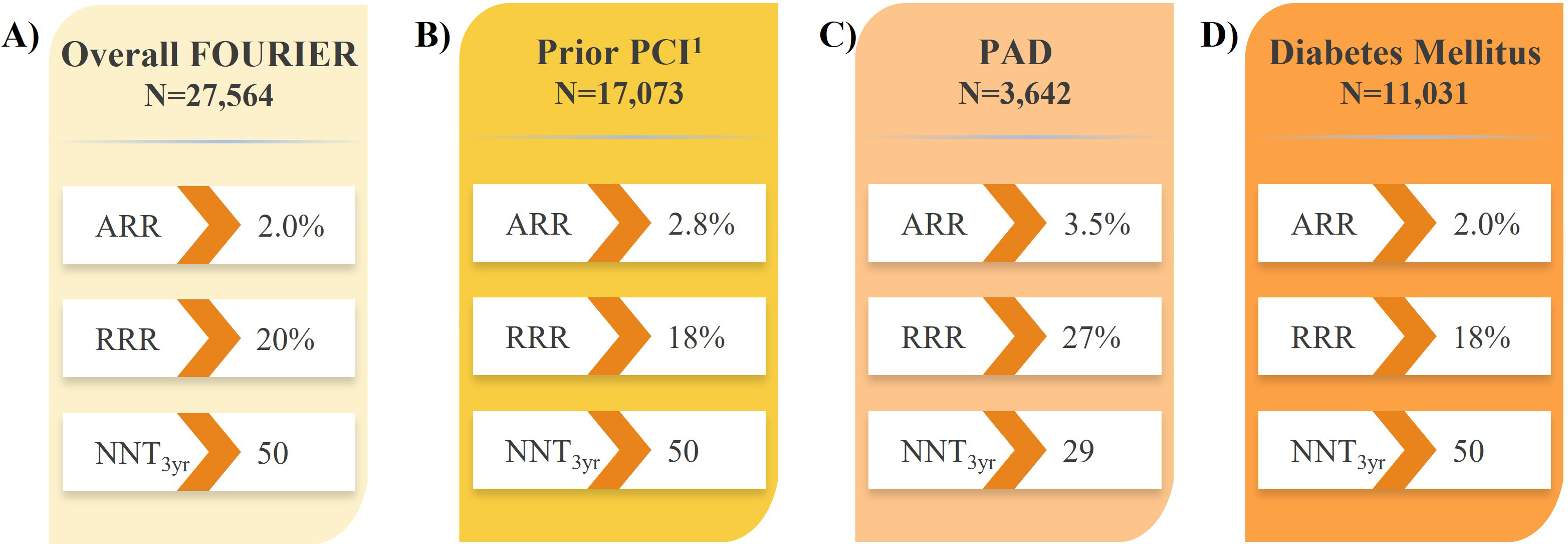

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Impact of evolocumab vs. placebo on CV death, MI, or stroke in

high- and very high-risk patients in the FOURIER trial. (A) Overall FOURIER

[16]. (B) Prior PCI [63]. (C) PAD [64]. (D) Diabetes Mellitus [65].

An open-label extension of the FOURIER trial (FOURIER-OLE; Table 5) was

conducted to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of evolocumab [36].

Patients (N = 6635) who completed FOURIER continued or transitioned to open-label

evolocumab (140 mg Q2W or 420 mg QM), with an additional median follow-up of 5.0

years. Maximum exposure to evolocumab in the parent trial plus FOURIER-OLE was

8.4 years, and patients were advised to continue other background LLT whenever

appropriate during follow-up. Consistent with the parent FOURIER trial, at 12

weeks after the start of FOURIER-OLE, LDL-C was reduced by 58.4% to a median of

0.75 mmol/L (30 mg/dL), which was consistent between patients irrespective of

their original treatment in the parent trial (i.e., evolocumab or placebo). An

LDL-C

| Trial | N | CV death, MI, or stroke, % | HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Placebo | Placebo |

Evolocumab | ||||

| Parent FOURIER (Median 2.2 years) [16] | 27,564 | 9.9 | - | 7.9 | 0.80 (0.73–0.88) | |

| FOURIER OLE (Median 5 years) [36] | 6635 | - | 19.26 | 16.82 | 0.80 (0.68–0.93) | 0.003 |

| CV death, % | ||||||

| Parent FOURIER (Median 2.2 years) [16] | 27,564 | 1.7 | - | 1.8 | 1.05 (0.88–1.25) | 0.62 |

| FOURIER OLE (Median 5 years) [36] | 6635 | - | 6.87 | 6.35 | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) | 0.04 |

CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; FOURIER, Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction; N, total number of patients included in the trial; OLE, open label extension; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9.

In another recent analysis of the FOURIER-OLE with a maximum follow-up of 8.6

years, there was a monotonic relationship between achieved LDL-C levels and CV

risk, with every 1 mmol/L (40 mg/dL) reduction in LDL-C conferring

~20% reduction in the risk of major CV events [60]. While this

finding is consistent with reports of agents from other LLT trials [7], the

FOURIER-OLE uniquely confirmed these CV benefits in patients with LDL-C

reductions to lower levels than previously studied, down to

Altogether, the FOURIER and FOURIER-OLE provide the largest and longest follow-up data available to date for a PCSK9i in patients with ASCVD. The results demonstrate rapid, clinically significant, and sustained efficacy with long-term evolocumab (+statin) treatment, with compounding CV benefits at lower achieved LDL-C levels and over time. Hence, the results emphasize the importance of early and significant LDL-C reduction to achieve the greatest clinical outcomes.

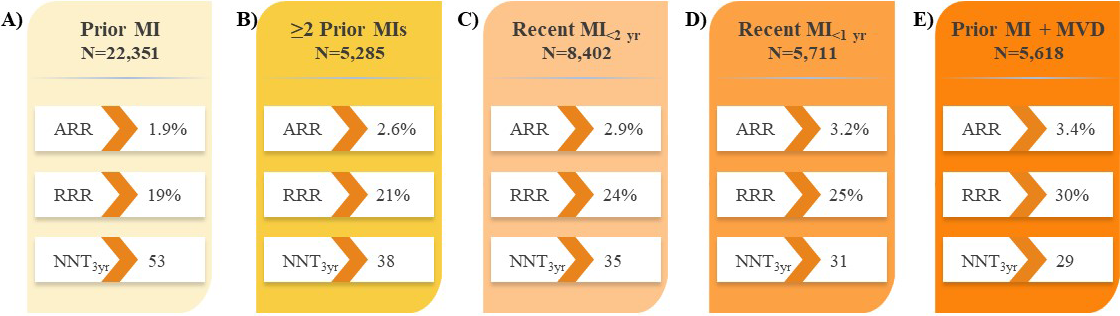

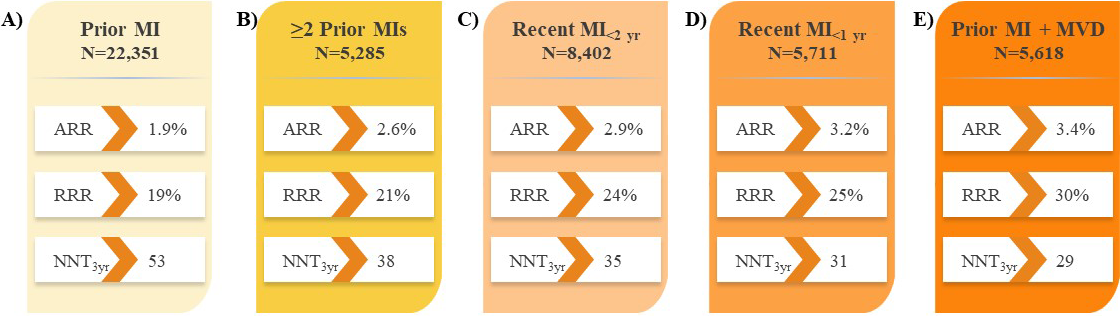

Recent analyses of large PCSK9i trials have identified subsets of patients with established ASCVD who are at increased risk of CV events and would derive the largest absolute benefit from LLT intensification with PCSK9i therapy [16, 17]. Further to the results in all patients with ASCVD in the FOURIER trial (Fig. 2A) [16], analyses revealed evolocumab treatment reduced the risk of major CV outcomes by 18–30% compared with placebo in subgroups of patients with prior MI with or without residual multivessel disease (Fig. 3) [61, 62], prior percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI; Fig. 2B) [63], and PAD (Fig. 2C) [64], suggesting the absolute benefits of evolocumab are enhanced in these vulnerable patients considering their higher absolute risk of CV events. Likewise, evolocumab was shown to reduce the risk of major CV outcomes compared with placebo in patients with diabetes mellitus (Fig. 2D) [65]. These results correspond to a number needed to treat (NNT) of just 29–50 patients with evolocumab over approximately 3 years, depending on the patient type, in addition to statin therapy and in line with the aforementioned study populations. This and other data on vulnerable patients with ASCVD are described in section 9 on evolocumab safety.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Impact of evolocumab on CV death, MI, or stroke in patients with

prior MI in the FOURIER trial. (A) Prior MI [61]. (B)

Elevated LDL-C is associated with an increased risk of recurrent or adverse CV

events in patients with ACS [66]. The impact of evolocumab on patients with ACS

was investigated in both the EVOlocumab for Early

Reduction of LDL-Cholesterol Levels in Patients With Acute

Coronary Syndromes (EVOPACS) and EVolocumab in Acute

Coronary Syndrome (EVACS) studies (Table 6) [40, 42].

EVOPACS investigated the 8-week feasibility, safety, and LDL-C effects of

evolocumab added to statin therapy during the in-hospital phase of ACS, compared

with placebo, which also included statin therapy. Most patients (62%) were

screened for study participation within

The EVACS study included patients with NSTEMI and troponin I

Altogether, the results from EVOPACS and EVACS demonstrate prompt addition of evolocumab in the hospital after ACS rapidly and significantly reduces LDL-C, compared with statin alone, in patients who most require LDLC reductions to reduce the risk of further CV events. Importantly, most patients were capable of achieving LDL-C levels below guideline-recommended thresholds for patients at increased CV risk prior to hospital discharge.

Patients with acute MI have higher rates of subsequent major CV events and

mortality relative to patients with ASCVD in general [6]. In patients in the

FOURIER trial who experienced prior MI, evolocumab demonstrated consistent LDL-C

reductions of 59–61% at 48 weeks from baseline, regardless of the time since

most recent MI, number of prior MIs, or the presence of residual multivessel CAD,

with a median achieved LDL-C of 0.75–0.78 mmol/L (29–30 mg/dL) [61]. Indeed,

the proportion of patients who achieved the LDL-C target threshold of

A blinded, post-hoc analysis of the FOURIER trial revealed evolocumab reduced the risk of any coronary revascularization by 22%, simple PCI by 22%, complex PCI by 33%, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery by 24%, and complex revascularization (the composite of complex PCI or CABG) by 29% [67]. Hence, these results suggest evolocumab may shift the risk from more complex revascularization procedures towards simple PCI or no revascularization at all. Interestingly, the magnitude of complex revascularization risk reduction with evolocumab tended to increase over time, from 20% in the first year post-evolocumab initiation to 41% beyond the second year. Patients who have undergone PCI are at high residual risk for CV events, including subsequent MI and coronary revascularization [68]. In a prespecified analysis of patients with prior PCI in the FOURIER trial, evolocumab treatment reduced LDL-C by 60.8% at 48 weeks compared with placebo [63]. Furthermore, evolocumab reduced the risk of the composite of CV death, MI, or coronary revascularization by 18% compared with placebo, over a median follow-up of 2.2 years (Fig. 2B), which did not significantly differ based on time since last PCI. Interestingly, CV risk reduction was observed almost immediately after evolocumab initiation, before growing over time, emphasizing the importance of early LDL-C lowering, especially in vulnerable patients, for the opportunity to derive the greatest benefit in the long term.

Patients with PAD have an increased risk of major CV events, including CV death, MI, and stroke, compared with patients with stable ASCVD [69, 70]. In patients with PAD in the FOURIER trial, treatment with evolocumab reduced LDL-C by 59% after 48 weeks compared with placebo, with LDL-C levels maintained over time [64]. Furthermore, evolocumab-treated patients had a 27% reduced risk of the composite of CV death, MI, or stroke compared with placebo, over a median follow-up of 2.2 years (Fig. 2C). Additionally, this was the first study to demonstrate a benefit of intensive LDL-C lowering for major adverse limb events (MALE) risk, including the composite of acute limb ischemia, major amputation, or urgent revascularization, with evolocumab treatment in all patients (with or without PAD) conferring a 42% reduced risk compared with placebo. There was a roughly linear relationship between reductions in LDL-C and the risk of MALE, down to an LDL-C of 0.26 mmol/L (10 mg/dL), highlighting the benefits of significant LDL-C lowering in patients with PAD. Further, evolocumab reduced the risk of the combination of MACE and MALE by 49%, yielding an NNT of 16 over 2.5 years for patients with PAD. Finally, there was no impact of evolocumab on any additional treatment emergent adverse events in patients with PAD.

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus has gradually increased globally over the

past decades [5], and given the association of diabetes mellitus with increased

risk for CV disease morbidity and mortality, there is a need for effective

strategies to lower LDL-C in this population [71]. The BANTING study investigated

the impact of evolocumab in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and

hypercholesterolemia or mixed dyslipidemia and on background statin therapy

(Table 6) [39]. Evolocumab significantly reduced LDL-C by 54.3% from baseline,

compared with 1.1% for placebo at week 12 [39]. Furthermore, 84.5% of patients

on evolocumab achieved LDL-C

Metabolic syndrome, comprising three or more of abdominal obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and/or low levels of HDL-C, is recognized as a risk factor for major CV events [2, 3, 4, 5]. In patients with metabolic syndrome in the FOURIER trial, compared with placebo, evolocumab reduced LDL-C by 57.7% at 48 weeks as well as the risk of the composite of CV death, MI, or stroke by 24% over a median follow-up of 2.2 years [72]. Hence, these results demonstrate the benefit of evolocumab in reducing CV risk in patients with several risk factors.

The reported incidence of statin-associated muscle symptoms in observational

studies ranges from 5 to 29% of treated patients, varying by statin and dose

[73, 74, 75, 76]; hence, studies have investigated the use of alternative treatments to

reduce LDL-C levels and improve CV outcomes in patients with statin intolerance

[15, 77]. The impact of evolocumab vs. ezetimibe in patients with statin

intolerance due to muscle-related adverse events was investigated in the GAUSS-3

study (Table 6) [38]. For the co-primary end point of mean change in LDL-C for

the mean of weeks 22 and 24 (which approximates mean treatment effect), a 54.5%

reduction was observed with evolocumab and a 16.7% reduction with ezetimibe. For

the other co-primary end point of mean change in LDL-C at week 24 (which reflects

effects at the end of the dosing interval), a 52.8% reduction was observed with

evolocumab and a 16.7% reduction with ezetimibe. Additionally, the proportion of

patients who achieved mean LDL-C

FH is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder characterized by chronically

elevated circulating LDL-C, which can accelerate the development of ASCVD, with

an estimated 10- to 20-fold increased risk compared with normolipidemic

individuals [79, 80, 81]. Patients with HeFH commonly experience LDL-C levels

Evolocumab efficacy in HeFH was also investigated in pediatric patients (aged

10–17 years) in the phase III Trial Assessing Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of PCSK9

InHibition in PediAtric SUbjectS With

GenEtic LDL DisordeRs (HAUSER) study (Table 6) [41]. Evolocumab reduced

LDL-C by 38.3% compared with placebo at week 24 [41]. Furthermore, 74% of

pediatric patients achieved LDL-C

In the open-label, single-arm TAUSSIG study (Table 6), evolocumab reduced LDL-C

by 1.94

In summary, FH is a serious incurable disease that substantially increases the risk of primary as well as secondary ASCVD, even in pediatric patients. These results demonstrate the addition of evolocumab to background statin therapy confers clinically significant LDL-C reductions to achieve levels below guideline-recommended thresholds, in a population wherein statins alone are often insufficient. Further, no additional evolocumab safety issues were identified in these studies, as described in section 9 on evolocumab safety. Hence, evolocumab is globally indicated in patients with HeFH and HoFH and is guideline-recommended to ultimately reduce the substantial CV risk associated with lifelong exposure to elevated LDL-C [2, 3, 4, 5].

Patients with HIV are considered to be at high risk for ASCVD because of

traditional risk factors such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, tobacco, and

hypertension, and also due to the immune-mediated changes associated with HIV

[86, 87, 88]. Moreover, evidence suggests certain antiretroviral therapies (ARTs) may

increase the risk of ASCVD, especially first-generation protease inhibitors that

can result in endothelial dysfunction or metabolic imbalances [86, 88, 89, 90].

Considering the minimal LLT studies in this high-risk patient population, the

impact of LLT is not well-understood. In the phase III BEIJERINCK study (Table 6), evolocumab treatment reduced LDL-C by 56.9% at week 24 compared with placebo

in patients with HIV receiving maximally tolerated statin therapy [43].

Additionally, 73.3% and 72.5% of patients on evolocumab achieved LDL-C

Real-world studies have assured the safety and benefits of LLT intensification

with PSCK9i to reduce LDL-C as observed in clinical trials are reproducible in

routine practice. In the U.S. Getting to an ImprOved Understanding of Low-Density

Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Dyslipidemia Management: A Registry of High Cardiovascular

Risk Subjects in the United States (GOULD) study (N = 5006) in patients with established

ASCVD and LDL-C above goal, 52.4% of patients on a PCSK9i for 2 years achieved

LDL-C

In the HEYMANS study (Table 7) of patients initiated on evolocumab as part of

routine clinical care across 12 European countries (N = 1951), 41% of patients

were not on background statin and/or ezetimibe therapy at evolocumab initiation

and 60% had reported statin intolerance [44]. Consistent with the FOURIER trial

and OLE [16, 36], evolocumab therapy was associated with a 58% reduction in

LDL-C from baseline after 3 months, which was maintained over 30 months of

follow-up, all despite the heterogenous patient population on varying background

LLT. Approximately 60% of patients achieved

In the ZERBINI study of patients initiated on evolocumab as part of routine

clinical care in three continents and five countries (Table 7), including Canada,

Mexico, Colombia, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait (N = 578), 15% of patients were not

on background statin and/or ezetimibe therapy at evolocumab initiation and 36%

had reported statin intolerance (ranging 7.7–61.8% across the different

countries) [46]. In the full heterogeneous cohort on varying background LLT,

evolocumab therapy was associated with a 70% reduction in LDL-C from baseline,

which was maintained over a 12-month period. Further, 76.0% of patients achieved

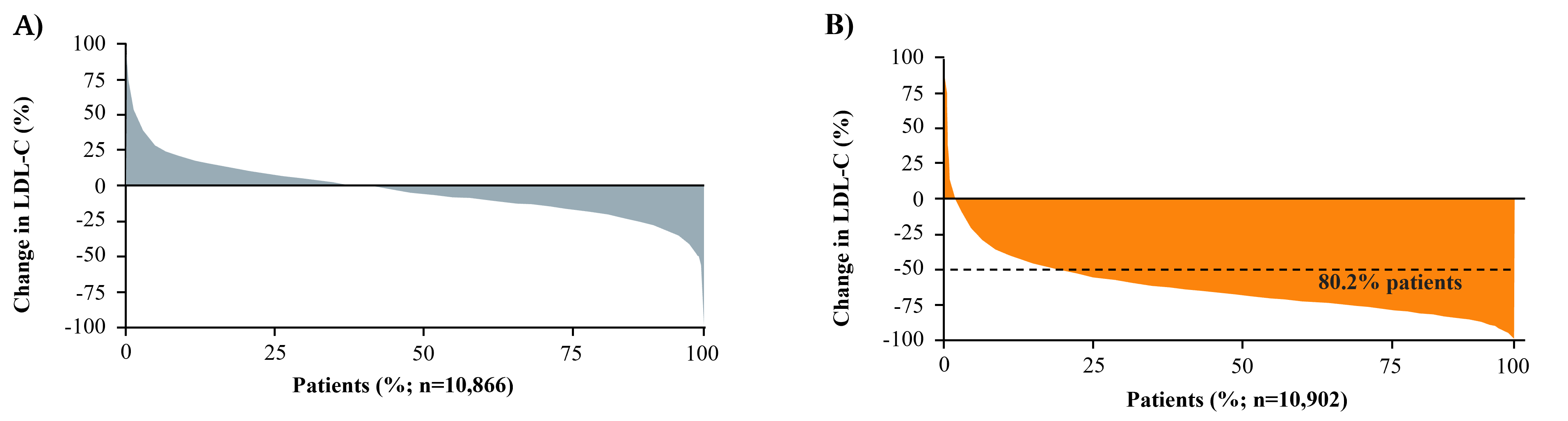

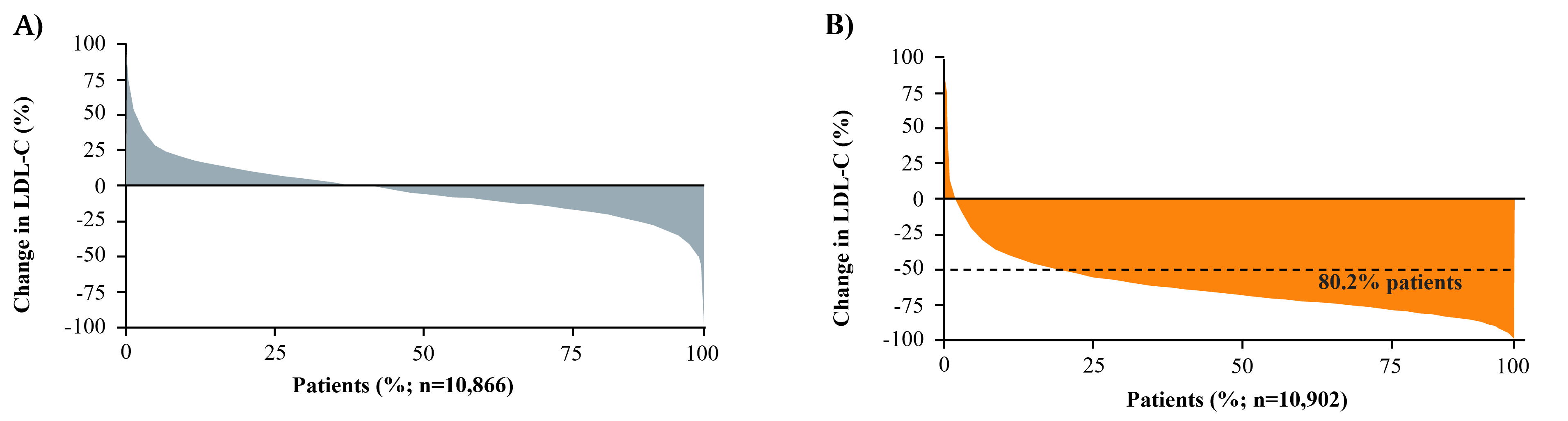

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Waterfall plots of the distribution of percentage change in

LDL-C from baseline. (A) Week 4 in Placebo Group of FOURIER. (B) Week 4 in

Evolocumab Group of FOURIER

Evolocumab has consistently been shown to have a favourable safety profile

across the PROFICIO program of clinical trials and RWE studies in patients at

high and very high CV risk [16, 36]. In the FOURIER trial, there were no

differences between the evolocumab and placebo groups in the rates of adverse

events, serious adverse events, or treatment emergent adverse events that lead to

study discontinuation, with the exception of injection site reactions, which were

more common with evolocumab compared with placebo (2.1% vs. 1.6%, respectively)

[16]. Likewise, there was no increase in any additional adverse events during the

8.4 years of follow-up in the FOURIER-OLE, the longest study of PCSK9 inhibition

in ASCVD to date [36]. Importantly, long-term evolocumab safety was consistent

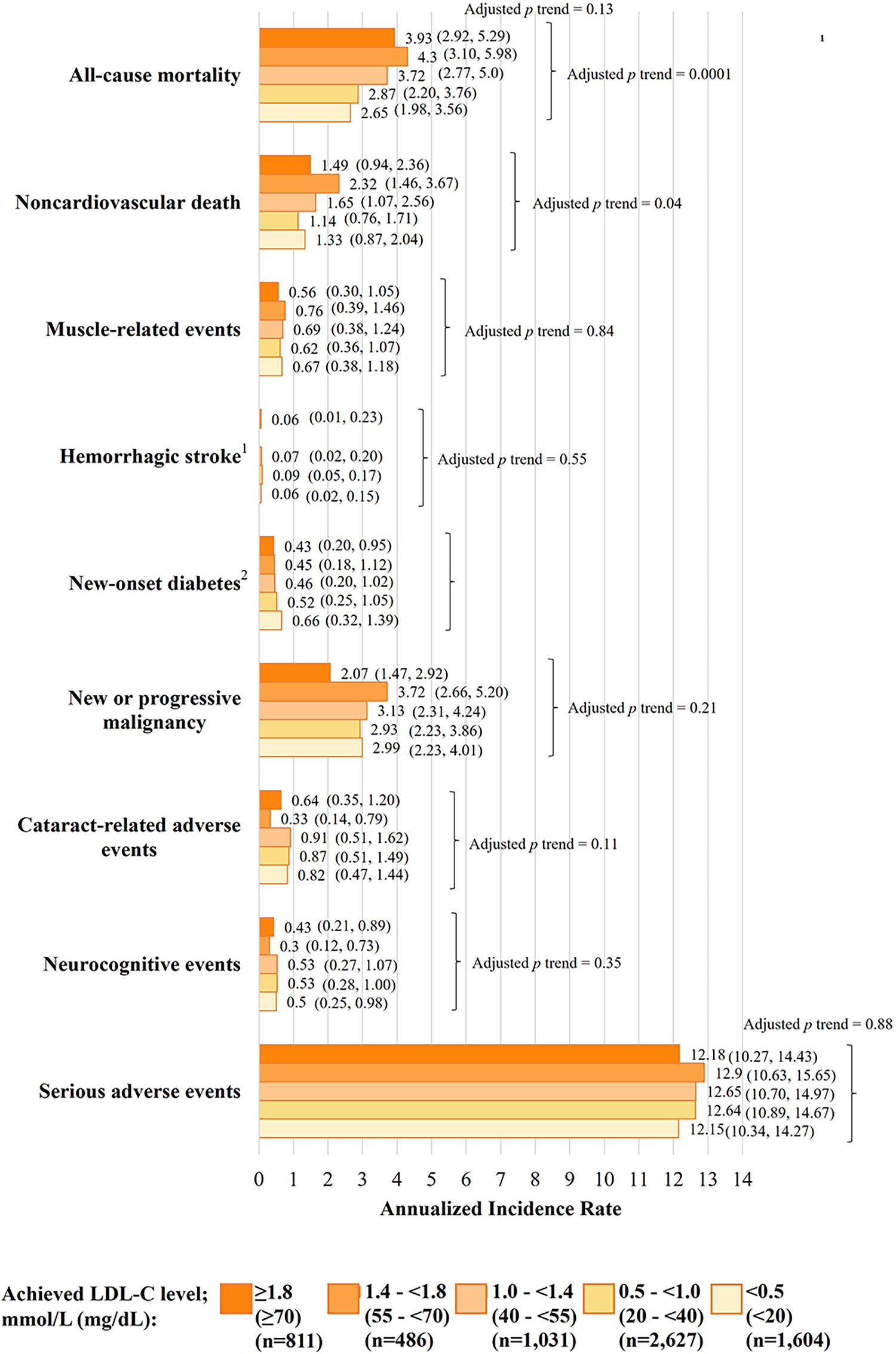

across all levels of achieved LDL-C, down to

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.Safety outcomes according to achieved LDL-C in the FOURIER-OLE

over a median evolocumab exposure of 5.0 years. Data are annualized incidence

rates (95% CIs) and have been adjusted for age, body mass index, sex, race

(White vs. other), previous myocardial infarction, nonhemorrhagic stroke, history

of PAD, history of diabetes, current smoking, high statin use, ezetimibe use, and

lipoprotein(a) at 12 weeks.

Evolocumab safety has also been shown to be consistent in clinical trials of special populations of patients at risk of or with established ASCVD. As mentioned, in the FOURIER trial, evolocumab did not increase the risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus or worsen glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus [65], and in the BEIJERINCK study, evolocumab safety was confirmed in immunocompromised patients with HIV [43]. Further, in the EBBINGHAUS trial in a subset of 1204 patients from the FOURIER trial, there was no significant difference in cognitive function between patients who received evolocumab or placebo over a median of 19.4 months in the context of the very low levels of achieved LDL-C [95]. Moreover, in pediatric patients with HeFH aged 10–17 years in the HAUSER study, evolocumab safety was consistent with that reported in trials of adult patients, and did not affect measures of pubertal development, growth variables, or carotid intima-media thickness after 24 weeks [41]. Likewise, after 80 weeks in the HAUSER-OLE, adverse event rates were consistent with the trial phase and none led to evolocumab discontinuation [96]. Ultimately, these evolocumab safety data met the rigorous criteria for international approval for use in pediatric patients (with HeFH and HoFH) [20]. Importantly, evolocumab has been confirmed to have no negative impact on cognition in both pediatric and adult patients. In fact, in the HAUSER study in pediatric patients with HeFH, abnormal and clinically important cognitive decline occurred less frequently in the evolocumab vs. placebo group [97].

The ZERBINI RWE study and sub-analyses by country confirmed these clinical data, with only 3.3% of patients reporting an adverse event, yet none of a serious nature [46, 92, 93, 94]. Notably, only 1 puncture site ecchymosis was reported in the ZERBINI study (0.2% of patients), which may be reflective of improved patient counselling on self-injection and administration skills over time. Further, the low incidence of myalgia (0.5%) in the ZERBINI study is also reassuring, especially considering 35.6% of patients had reported statin intolerance, suggesting evolocumab does not exacerbate muscle symptoms in susceptible patients [46]. Altogether, these results suggest a favourable safety profile for evolocumab, with the only reported contraindication being patients who are hypersensitive to evolocumab [20].

Consistent with robust evolocumab effectiveness and tolerability, there is a

growing body of RWE demonstrating a high persistence rate (

Evolocumab evidence generation continues to advance, with an ongoing commitment to understand the potential efficacy benefits and safety of evolocumab in unstudied patient populations with increased CV risk. A summary of select major ongoing studies at the time of this review is presented here:

Effect of EVolocumab in PatiEntS at High CArdiovascuLar RIsk WithoUt Prior Myocardial Infarction or Stroke (VESALIUS)-CV is a phase III multinational trial assessing the effect of optimized LLT intensification with evolocumab in reducing first major CV events in adults with established ASCVD or diabetes mellitus, without prior MI or stroke, compared with placebo (+optimized LLT) [104]. Inclusion criteria require elevated LDL-C and presence of at least one of the following high-risk conditions at screening: significant CAD, atherosclerotic cerebrovascular disease, PAD, and/or diabetes mellitus. Primary outcomes are time to coronary heart disease death, MI, or ischemic stroke or any ischemia-driven arterial stroke over a minimum of 4.5 years of follow-up. This study will be the first CV outcome study with a PCSK9i to include a large cohort of primary prevention patients.

The phase IV A Pragmatic, Randomized, Multicenter Trial of EVOLocumab Administered Very Early to Reduce the Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Patients Hospitalized With Acute Myocardial Infarction (EVOLVE-MI) open-label trial is evaluating the effect of early treatment with evolocumab plus routine LLT vs. routine LLT alone to reduce MI, ischemic stroke, arterial revascularization, and all-cause mortality in adult patients hospitalized for an acute MI (NSTEMI and STEMI) [105]. This is a pragmatic study to assess the impact of evolocumab initiated within 10 days of the index MI in the acute setting compared with standard of care. The primary outcome is the total (first and subsequent) composite of MI, ischemic stroke, any arterial revascularization procedure, and all-cause mortality over approximately 3.5 years of follow-up.

NEWTON-CABG is a phase IV trial evaluating the effect of evolocumab added to

routine statin therapy on vein graft patency after CABG surgery compared with

placebo (+statin) [106]. The primary outcome is saphenous vein graft disease rate

(VGDR) 24 months post-CABG, with VGDR defined as the proportion of vein grafts

with significant stenosis or total occlusion (

Taken together, the results of these novel studies will advance the current understanding of the impact of LLT intensification with evolocumab on major CV outcomes in vulnerable patients. Further, these studies will address a data gap and may help shape clinical practice for certain patient types for whom current guidelines are unclear, such as those with diabetes mellitus without established ASCVD.

This review provides evidence for the significant clinical and real-world CV

benefits of PCSK9 inhibition with the mAb evolocumab in patients with and without

established ASCVD. The various evolocumab data summarized from the 50 clinical

trials and RWE studies in

All authors (LAL, RAH, VB, JB, ESM and GBJM) participated sufficiently in the work according to the ICMJE guidelines and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors contributed to the design of the review, interpretation of included studies, and revisions to the manuscript drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

The authors express gratitude to the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

Editorial assistance was provided by Danyelle Liddle, PhD, MSc and Karamjeet Singh, PhD of MEDUCOM Health Inc., and funding was provided by Amgen Canada Inc.

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest for grants, contracts, consulting fees, honoraria, support for attending meetings, and/or participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board. LAL: Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Esperion, HLS Therapeutics, Kowa, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi; RAH: Acasti, Akcea/Ionis, Amgen, Amryt, Arrowhead, HLS Therapeutics, Medison, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Ultragenyx; VB: AbbVie, Amgen, BioSyent, Eisai, GSK, Merck, Moderna, Pfizer, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Seqirus, Sunovion; JB: Amarin, Amgen, Amryt, Arrowhead, Eli Lilly, HLS Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals Inc., Kowa, LIB Therapeutics, Medison, New Amsterdam Pharma, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Regeneron, Sanofi, Ultragenyx; ESM is an employee of and owns stock in Amgen Canada Inc.; GBJM: Amgen, Esperion, HLS Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.