1 Department of Gastroenterology, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100029 Beijing, China

Abstract

Background: Limited studies have explored the association between blood

urea nitrogen (BUN) levels and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute

myocardial infarction (AMI) and subsequent gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB). Our

objective was to explore this correlation. Methods: 276 individuals with

AMI and subsequent GIB were retrospectively included between January 2012 and

April 2023. The predictive value of BUN for in-hospital mortality was assessed

through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Logistic regression models

were constructed to assess the relationship between BUN and in-hospital

mortality. Propensity score weighting (PSW), sensitivity and subgroup analyses

were used to further explore the association. Results: Fifty-three

(19.2%) patients died in the hospital. BUN levels were higher in non-survivors

compared with the survivors [(11.17

Keywords

- gastrointestinal bleeding

- blood urea nitrogen

- risk stratification

- acute myocardial infarction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a critical medical emergency related to substantial morbidity, mortality, and the utilization of healthcare resources [1]. Aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor are the default antithrombotic strategy after AMI [2]. Although this approach reduces the occurrence of ischemic events, it concurrently elevates the risk of bleeding [3]. Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) frequently contributes to hemorrhage in patients with AMI [4]. Research findings indicate GIB rates in the range of 0.87% to 1.5% among patients with AMI, correlating with elevated risks of both early and late adverse clinical outcomes [5, 6, 7, 8]. Giving the unfavorable prognosis of patients with GIB after AMI, identifying predictors for early risk stratification is critical.

Some studies have discussed potential risk factors in this setting [6, 9, 10]. In a retrospective study conducted at a single center, participants diagnosed with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and upper GIB showed that several factors may independently influence in-hospital mortality, including age, peak white blood cell count, minimum platelet count, and peak brain natriuretic peptide levels [10]. Another retrospective study, which included 51 patients with AMI who developed GIB, suggested that a decreased hemoglobin level and a high Killip classification may be the risk factors for in-hospital mortality [6]. However, these studies either involved small sample sizes or were limited to patients with NSTEMI, indicating the necessity of more studies to comprehensively evaluate the predictive value of their findings. Moreover, we speculated whether there are additional risk factors correlate with the early prognosis in patients experiencing AMI and subsequent GIB that have not been explored.

Mounting evidence has linked increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels with poor outcomes in patients with AMI [11, 12, 13, 14]. In this context, BUN is susceptible to the influence of various factors, including renal function, cardiac output, systemic perfusion, and neurohumoral regulation. During an AMI, these factors typically change [13]. Furthermore, considering the breakdown and digestion of blood proteins through the gastrointestinal tract, elevated BUN levels are common in patients with acute GIB, especially upper GIB [15]. The Glasgow-Blatchford scale (GBS) is a fully validated score utilizing BUN as a predictive marker to assess the necessity of clinical intervention in patients with upper GIB [16]. However, the value of BUN in predicting in-hospital mortality among individuals experiencing GIB after AMI remains unclear, especially when considered alongside other established risk factors for clinical outcomes.

Thus, our objective was to explore the correlation between BUN levels and in-hospital mortality in patients with AMI and subsequent GIB.

The present investigation was a single-center retrospective study. Patients diagnosed with AMI and subsequently GIB during the same hospitalization between January 2012 and April 2023 at the Beijing Anzhen Hospital of Capital Medical University (Beijing, China) were retrospectively enrolled. AMI was diagnosed based on the Fourth Universal Definition [17]. GIB was defined as the presence of symptoms of gastrointestinal tract bleeding, including coffee ground emesis, hematemesis, melena, or evidence of bleeding observed during endoscopic examination in the gastrointestinal tract [4]. The inclusion criteria involved the confirmation of AMI complicated by GIB. Patients diagnosed with GIB who developed AMI, individuals only presented with positive fecal occult blood tests, and individuals lacking baseline data were excluded from the research. The study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University (approval number: 2023132X). As this study was retrospective, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Data collected included demographic characteristics, medical history, admission features, laboratory data, and medical treatments. We obtained laboratory data including BUN from the first test conducted upon admission before any acute intervention [such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)] and assayed at the central core laboratory. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated by the currently recommended Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [18]. The primary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality. All participants were followed up for death or discharge using complete inpatient medical records.

Continuous variables are presented as mean

Furthermore, we employed multivariate logistic regression models to assess the

relationship between BUN and in-hospital mortality. Model 1 adjusted for age and

sex. Model 2 adjusted for: age, sex, STEMI, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP),

Killip classification, chronic kidney disease (CKD), extracorporeal membrane

oxygenation (ECMO), cardiogenic shock, heart rate, systolic blood pressure,

albumin, eGFR, thrombolysis, PCI, CABG, continuous renal replacement therapy

(CRRT), transfusion, and diuretics. Considering significant differences in

certain population characteristics among subjects with different BUN levels using

inverse probability of weight (IPW) to calculate propensity score weighting

(PSW), PSW-weighted multivariate logistic regression analyses were subsequently

developed to further control for confounding variables. Moreover, sensitivity and

subgroup analyses were performed using multivariable logistic regression Model 2.

The interaction effect between BUN and eGFR was evaluated using the

log–likelihood ratio test. Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing SPSS

26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for

Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria); differences with a p

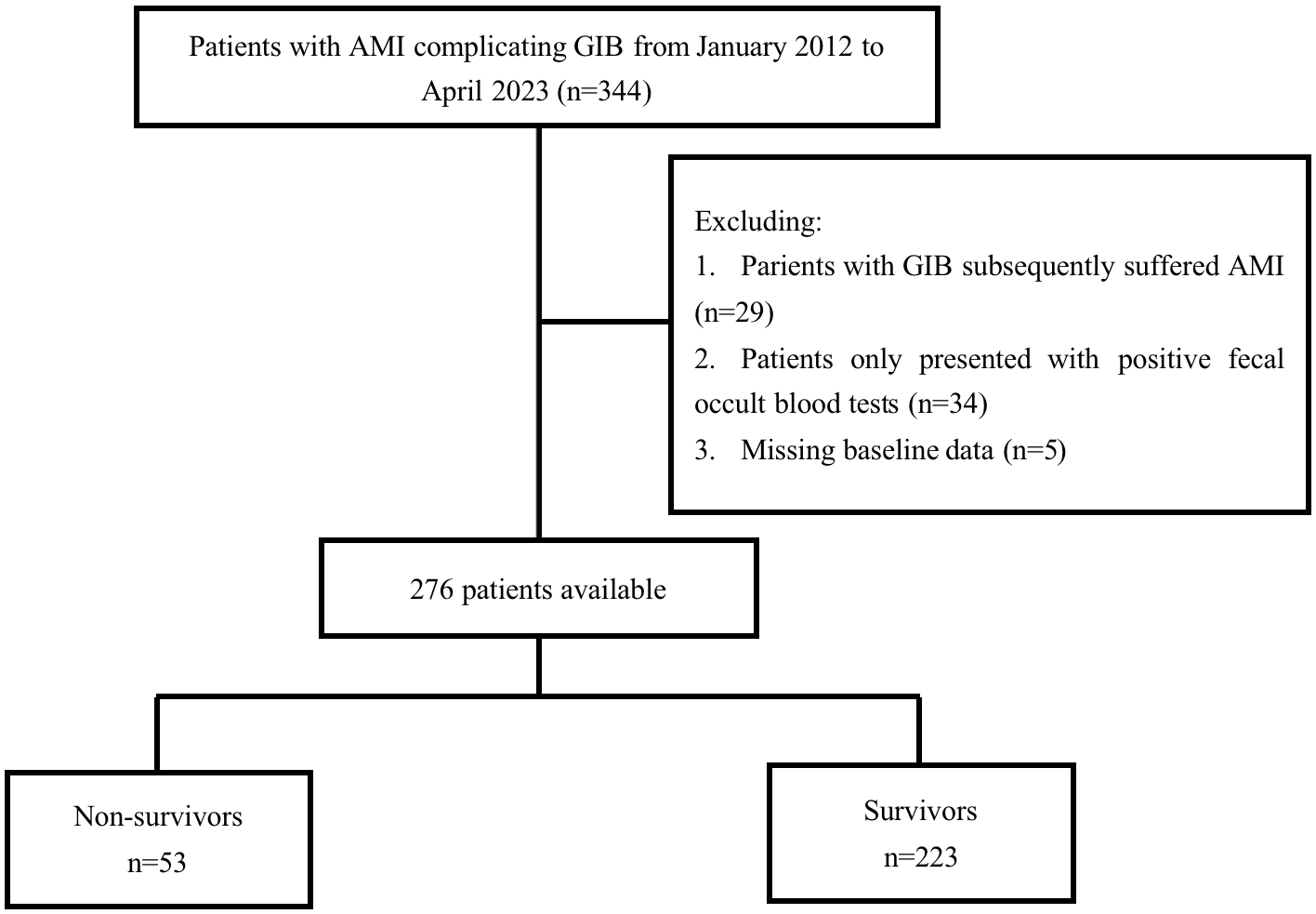

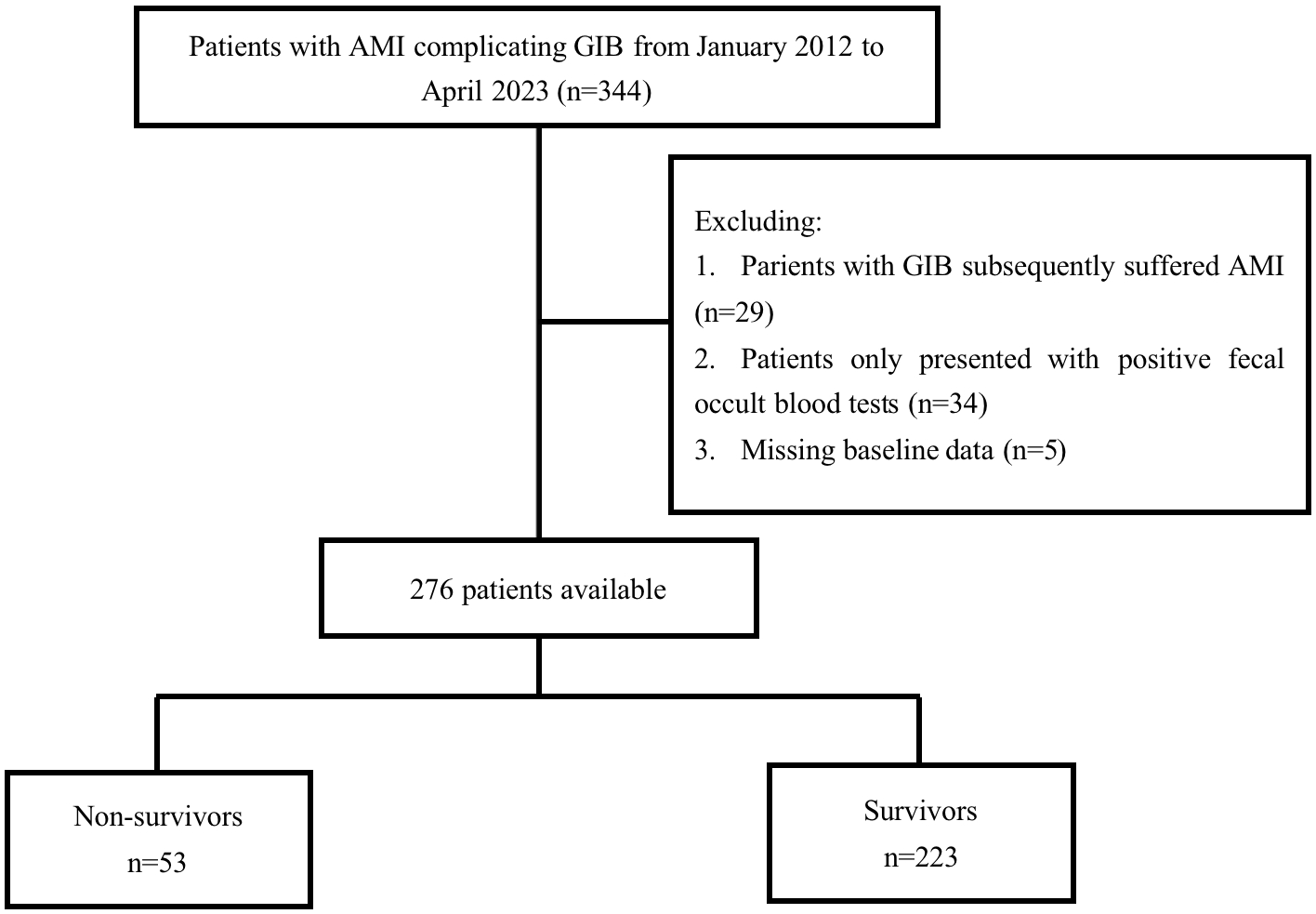

Between January 2012 and April 2023, 344 patients were

diagnosed with AMI complicated by GIB at the authors’ center. After excluding 29

individuals diagnosed with GIB who developed AMI, 34 individuals with only

positive fecal occult blood tests, and 5 patients with missing data (Fig. 1), our

study included 276 participants. Among the 276 participants enrolled, 184

(66.7%) were male, and the cohort had a mean age of 67.15

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Flow chart of patient’s selection. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding.

| Variables | Non-survivors | Survivors | p-value | |

| (n = 53) | (n = 223) | |||

| Age, years | 69.49 |

66.59 |

0.112 | |

| Male, n (%) | 34 (64.2) | 150 (67.3) | 0.666 | |

| Smoking, n (%) | 13 (24.5) | 74 (33.2) | 0.223 | |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 39 (73.6) | 148 (66.4) | 0.312 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 25 (47.2) | 86 (38.6) | 0.251 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11 (20.8) | 27 (12.1) | 0.101 | |

| History of AMI | 10 (18.9) | 28 (12.6) | 0.231 | |

| History of PCI | 12 (22.6) | 36 (16.1) | 0.262 | |

| History of CAGB | 1 (1.9) | 10 (4.5) | 0.632 | |

| History of GIB | 1 (1.9) | 14 (6.3) | 0.352 | |

| Admission features | ||||

| STEMI | 37 (69.8) | 140 (62.8) | 0.337 | |

| Killip classification |

45 (84.9) | 112 (50.2) | ||

| Cardiogenic shock | 19 (35.8) | 32 (14.3) | ||

| Heart rate |

15 (28.3) | 14 (6.3) | ||

| Systolic BP |

12 (22.6) | 32 (14.3) | 0.138 | |

| Hemoglobin |

11 (20.8) | 40 (17.9) | 0.635 | |

| Albumin |

9 (17.0) | 17 (7.6) | 0.067 | |

| eGFR |

32 (60.4) | 60 (26.9) | ||

| BUN, mmol/L | 11.17 |

8.09 |

0.001 | |

| PT prolongation |

5 (9.4) | 15 (6.7) | 0.698 | |

| Medical treatments, n (%) | ||||

| Thrombolysis | 1 (1.9) | 13 (5.8) | 0.408 | |

| PCI | 12 (22.6) | 97 (43.5) | 0.005 | |

| CAGB | 9 (17.0) | 8 (3.6) | 0.001 | |

| IABP | 15 (28.3) | 21 (9.4) | ||

| ECMO | 6 (11.3) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| CRRT | 17 (32.1) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Endoscopy | 3 (5.7) | 16 (7.2) | 0.929 | |

| Transfusion | 25 (47.2) | 51 (22.9) | ||

| Aspirin | 36 (67.9) | 187 (83.9) | 0.008 | |

| Clopidogrel or ticagrelor | 41 (77.4) | 208 (93.3) | ||

| Anticoagulants | 43 (81.1) | 159 (71.3) | 0.146 | |

| PPIs | 52 (98.1) | 223 (100) | 0.433 | |

| Diuretics | 47 (88.7) | 133 (59.6) | ||

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 32 (60.4) | 141 (63.2) | 0.700 | |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 12.77 |

13.29 |

0.736 | |

GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PT, prothrombin time; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; BP, blood pressure; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ARB, angiotensin-II receptor blocker; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors.

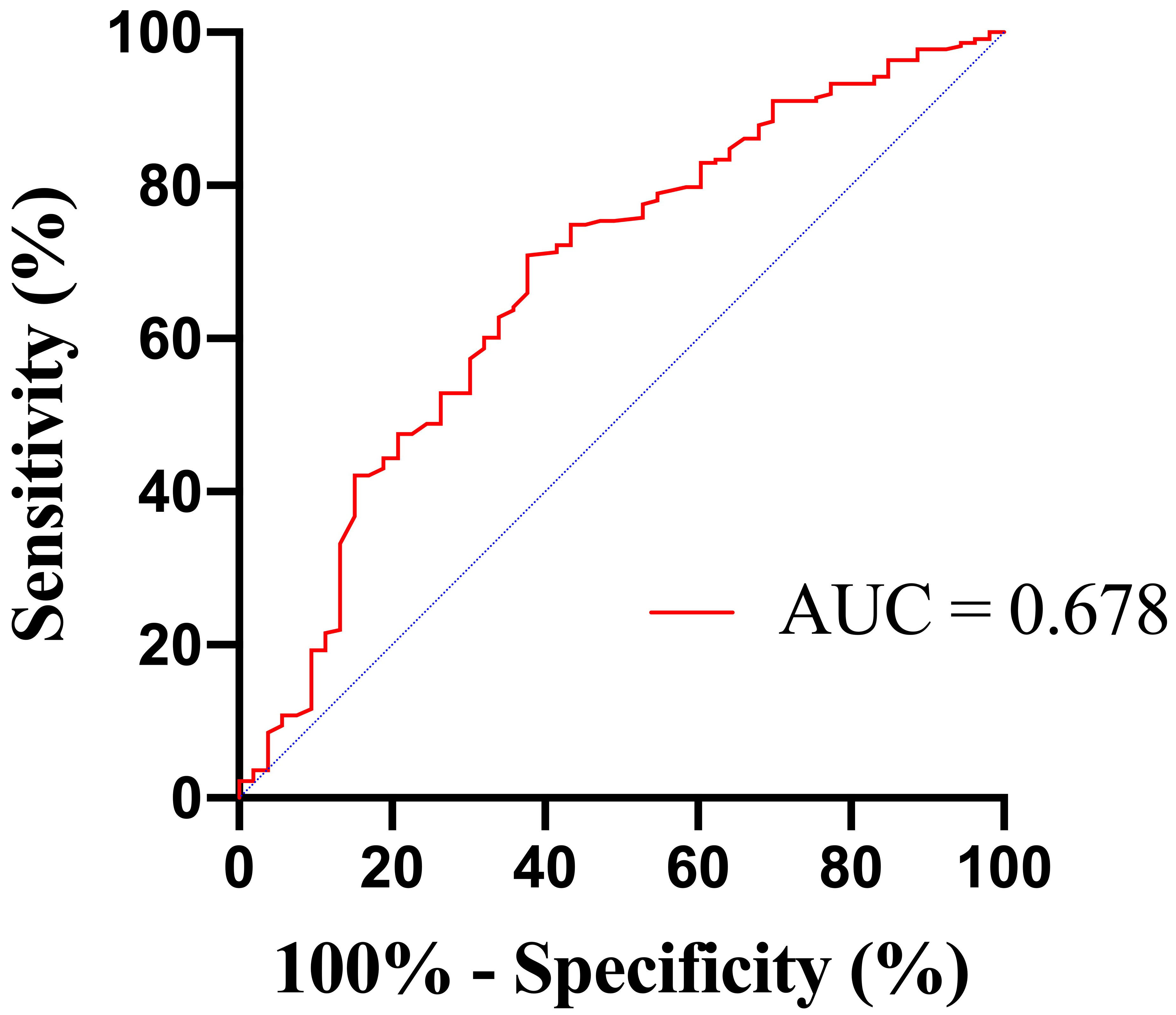

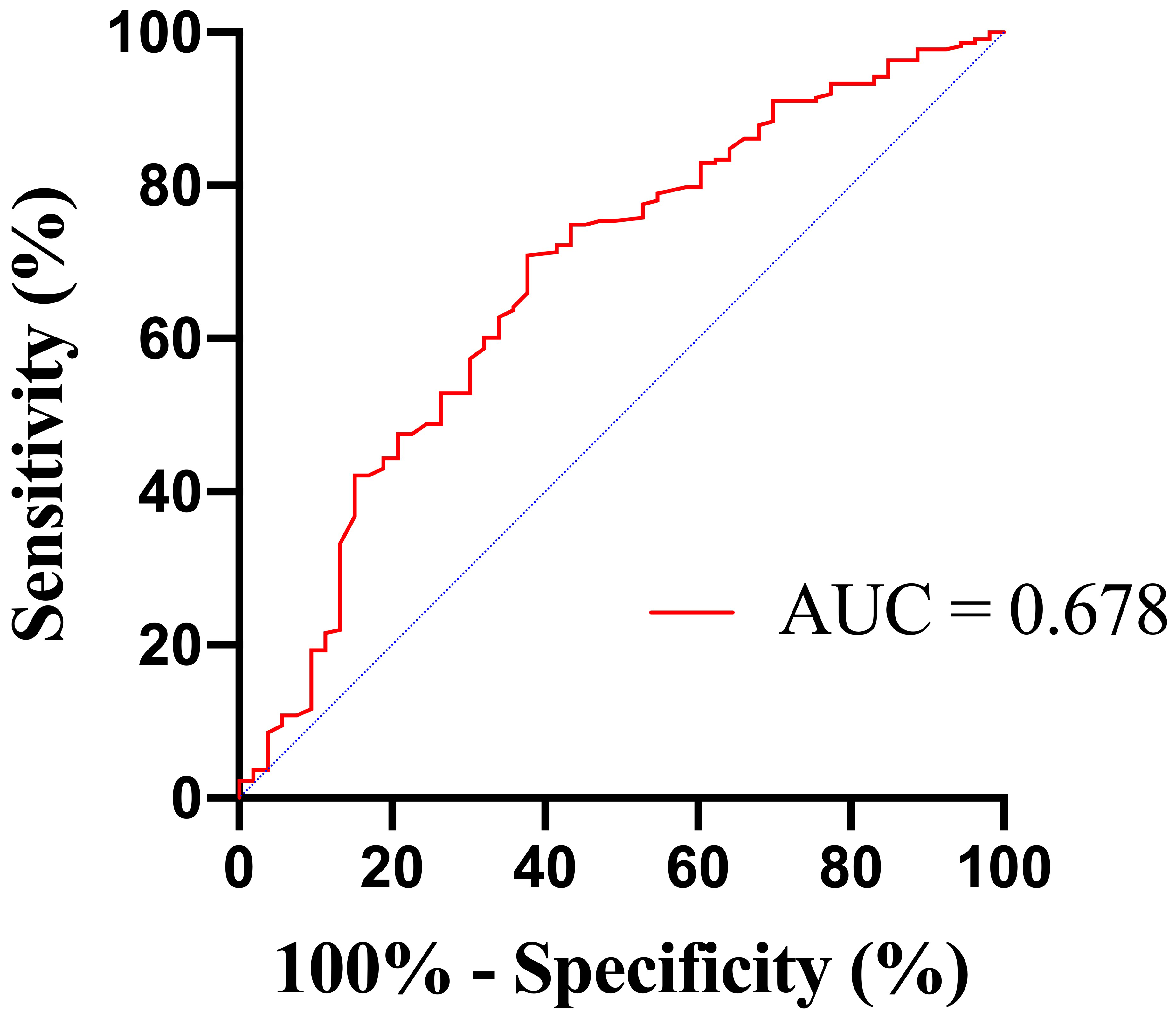

The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for BUN in predicting in-hospital mortality

was 0.678 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.595–0.761; p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of BUN to predict in-hospital mortality. BUN, blood urea nitrogen; AUC, area under the ROC curve.

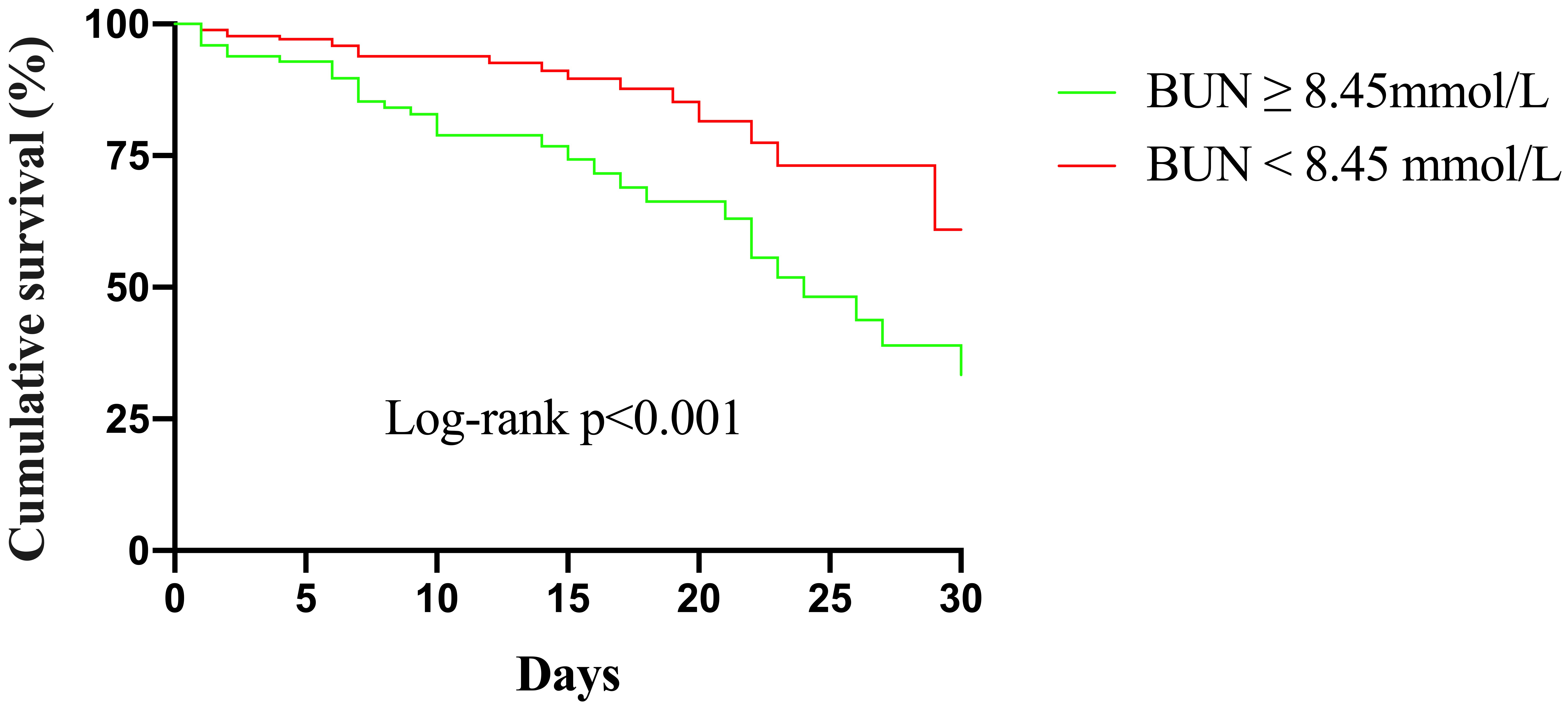

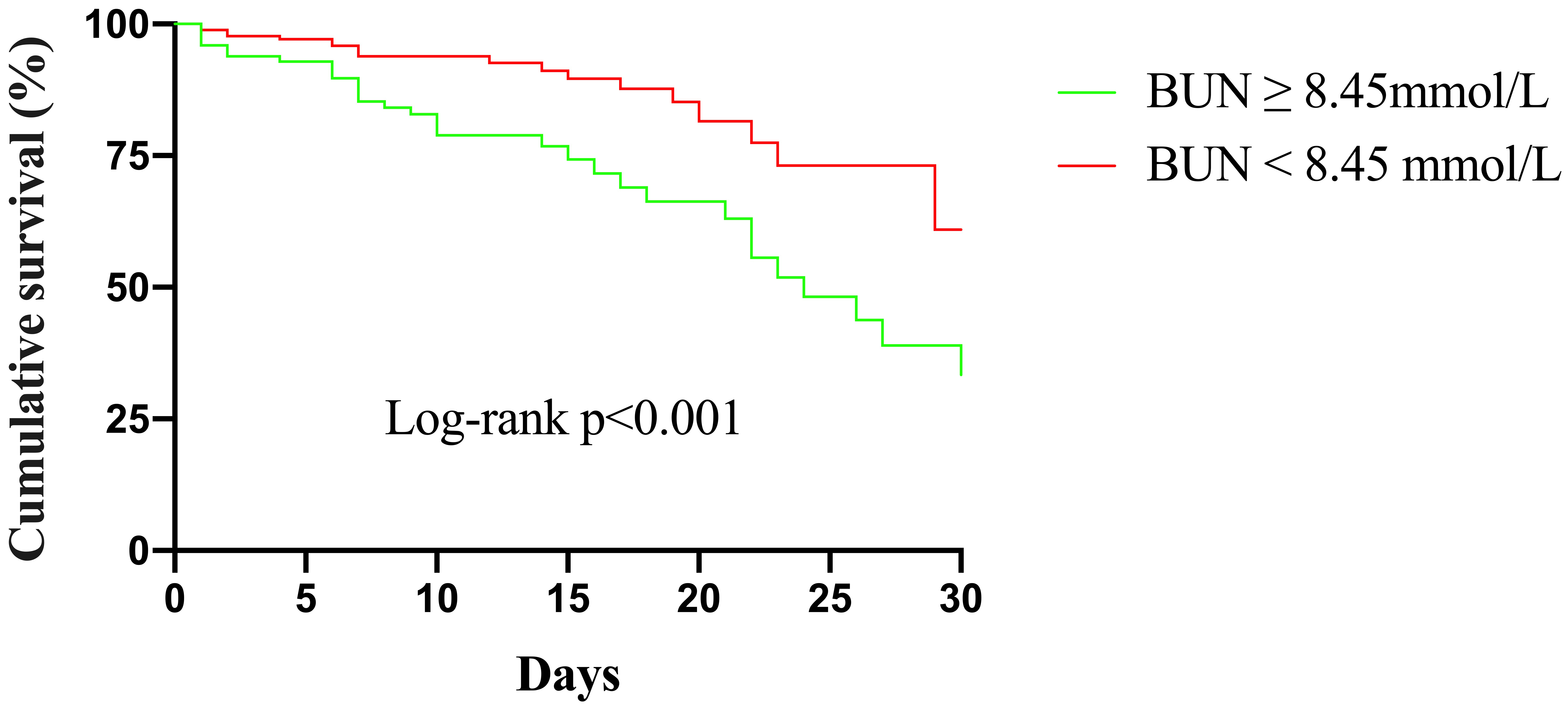

Kaplan–Meier curves for different BUN levels are presented in Fig. 3.

The cumulative in-hospital mortality for patients with BUN

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Kaplan–Meier survival from in-hospital mortality for patients according to different BUN levels. BUN, blood urea nitrogen.

The logistic regression models and the results are shown in Table 2. Elevated

BUN levels showed a positive correlation with in-hospital mortality in the

unadjusted model, and this association persisted in the adjusted models. Upon

incorporating age and sex information in Model 1, increased BUN levels were

positively correlated with in-hospital mortality both as a continuous variable

(odds ratio [OR] 1.11, 95% CI 1.05–1.18, p

| Unadjusted | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| Crude OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| BUN | 1.12 (1.06–1.18) | 1.11 (1.05–1.18) | 1.06 (0.96–1.17) | 0.226 | ||

| BUN |

4.01 (2.15–7.50) | 3.84 (2.03–7.27) | 4.01 (1.55–10.42) | 0.004 | ||

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex; Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, CKD, STEMI, Killip classification, cardiogenic shock, heart rate, systolic BP, albumin, eGFR, thrombolysis, PCI, CABG, IABP, ECMO, CRRT, transfusion, and diuretics. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CKD, chronic kidney disease; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy.

There were significant differences in population characteristics among patients

with different BUN levels in Supplementary Table 1. To further control

for confounding variables, we also carried out PSW in the study cohort. The

comparison of patient characteristics after weighting is available in

Supplementary Table 2. Baseline characteristics were well balanced.

PSW-weighted regression models and the results are presented in Table 3. BUN as a

continuous variable showed independently correlation with in-hospital mortality

in the unadjusted model (OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.06–1.18, p

| Unadjusted | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| Crude OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| BUN | 1.12 (1.06–1.18) | 1.12 (1.06–1.18) | 1.11 (1.02–1.19) | 0.012 | ||

| BUN |

2.28 (1.44–3.61) | 2.25 (1.42–3.56) | 0.001 | 4.73 (2.41–9.29) | ||

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex; Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, CKD, STEMI, Killip classification, cardiogenic shock, heart rate, systolic BP, albumin, eGFR, thrombolysis, PCI, CABG, IABP, ECMO, CRRT, transfusion, and diuretics. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CKD, chronic kidney disease; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy.

We performed sensitivity and subgroup analyses to evaluate the persistence of

correlation between BUN levels and in-hospital mortality in patients without

severe renal insufficiency. After excluding 38 patients with a history of chronic

renal insufficiency, elevated BUN levels remain positive association with

in-hospital mortality, both as a continuous variable (OR 1.18, 95% CI

1.03–1.36, p = 0.018) and as a categorical variable (OR 4.22, 95% CI

1.55–11.49, p = 0.005). When patients undergoing regular hemodialysis

and those receiving CRRT during hospitalization were excluded (n = 24), BUN

Our study revealed an association between BUN levels and the risk for in-hospital mortality in patients with AMI and subsequent GIB, irrespective of established clinical characteristics. Elevated BUN levels may serve as a convenient marker of adverse outcomes in patients experiencing GIB after AMI.

GIB is a serious condition linked to an increased risk for early poor clinical prognosis in patients with AMI [5]. Therefore, one of the most critical challenges for healthcare professionals is to identify patients at high risk of mortality after AMI complicated by GIB. However, there are still many unknown factors that affect in-hospital outcomes in these patients. Some single-center retrospective studies have discussed potential risk factors for this situation; however, BUN has not been found to have a significant impact on in-hospital mortality in individuals with AMI complicated by GIB [6, 9, 10]. To our knowledge, the present study is one of the largest investigations involving AMI patients who developed GIB and reports a higher degree of certainty than previous studies. Moreover, it is the first study to focus on the prognostic effect of BUN in this patient population.

BUN is a metabolic protein product, the concentration of which depends on the balance between renal reabsorption and excretion. For decades, BUN has been considered as an indicator of renal function and prognostic factor in many clinical conditions. The GBS is a commonly used clinical score that incorporates BUN on admission as one of its risk factors. It is designed to predict the necessity for clinical intervention of acute upper GIB [16]. In addition to the GBS, several novel scoring systems using BUN as a predictor have been developed to assist physicians in dealing with upper GIB or lower GIB [19, 20]. In patients with AMI, BUN has demonstrated promising potential as a more important indicator for adverse prognosis rather than creatinine [14]. Furthermore, BUN has been reported to be superior to other renal markers in evaluating the risk for heart failure or even cardiogenic shock [11, 21].

In the present study, after adjusting for other relevant clinical covariates

using PSW-weighted multivariate logistic regression models, BUN exhibited a

significant association with in-hospital mortality, both as a continuous variable

and a categorical variable. We additionally conducted sensitivity and subgroup

analyses to evaluate the robustness of this correlation. Sensitivity and subgroup

analyses revealed that BUN

The reasons for the correlation between BUN and early prognosis in individuals who develop GIB after AMI can be explained as followed. During the acute stage of myocardial infarction, systemic and renal hypoperfusion are common. These conditions lead to the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which enhance the reabsorption of urea in the proximal tubules [11, 12, 22, 23], resulting in an elevation in BUN levels. This provides additional prognostic information beyond eGFR. Our study observed elevated BUN levels in patients with a higher Killip classification. This may indirectly reflect more severe hemodynamic alterations and neurohormonal activation in conditions of low cardiac output and decompensated heart failure, ultimately leading to an increase in BUN levels.

When patients with AMI experience severe GIB, unstable hemodynamics pose a significant threat. Hypovolemia and dehydration may aggravate renal hypoperfusion [24], leading to neurohormonal activation, which in turn enhances urea reabsorption. High BUN levels have been found to be potentially associated with more severe GIB [25]. Our study also indicated that BUN levels were inversely correlated with hemoglobin levels, suggesting that BUN may indirectly reflect the severity of bleeding. Unfavorable hemodynamic conditions may also result in myocardial ischemia and reinfarction. Even mild GIB can induce systemic inflammation in a prothrombotic state, potentially resulting in recurrent ischemic events [6]. Myocardial reinfarction is usually accompanied by severe hemodynamic alterations and renal hypoperfusion with sequential BUN elevation. Therefore, BUN may serve as a simple marker of renal perfusion and neurohormonal activation in patients with rapid hemodynamic alterations, which is valuable in determining the outcomes of patients with GIB post-AMI. In such patients, alterations in eGFR calculated based on creatinine may not be evident or may lag behind the actual changes. Thus, early identification of patients with elevated BUN levels, proactive treatment of GIB, and enhancement of cardiac function and systemic perfusion are crucial for improving the outcomes of patients experiencing GIB after AMI.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, it was a single-center retrospective design with the inherent shortcomings associated with the analysis of pre-recorded data. Second, the patient cohort was relatively small, primarily due to the low incidence of GIB. As such, further studies with larger cohorts are needed. Despite these limitations, this study identifies the significance of BUN as a simple marker for early prognosis in patients with AMI and subsequent GIB.

Our study demonstrates that BUN levels were associated with in-hospital mortality in patients with AMI and subsequent GIB. This information will be valuable for early risk stratification of individuals experiencing GIB after AMI.

The data are obtainable on request from the corresponding author in this study. They are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

FL and JZ designed the research study. FL and XC performed the research and collected the data. FL and YS analyzed the data. FL drafted the manuscript. FL, XC, YS, and JZ reviewed and modified the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University (approval number: 2023132X). Patient consent was waived due to retrospective study and no informed consent can be obtained from the patients.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. We would like to thank the patients for their participation and all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.