1 Department of Anesthesiology, Fuwai Yunnan Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Affiliated Cardiovascular Hospital of Kunming Medical University, 650000 Kunming, Yunnan, China

2 Department of Anesthesiology, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 100037 Beijing, China

3 Department of Anesthesiology, Harrison International Peace Hospital, 053000 Hengshui, Hebei, China

Abstract

Background: Pulmonary artery catheters (PAC) are widely used in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) grafting surgery. However, primary data suggested that the benefits of PAC in surgical settings were limited. Therefore, the present study sought to estimate the effects of PAC on the short-term outcomes of patients undergoing OPCAB surgery. Methods: The characteristics, intraoperative data, and postoperative outcomes of consecutive patients undergoing primary, isolated OPCAB surgery from November 2020 to December 2021 were retrospectively extracted. Patients were divided into two groups (PAC and no-PAC) based on PAC insertion status. Data were analyzed with a 1:1 nearest-neighbor propensity score matched-pair in PAC and no-PAC groups. Results: Of the 1004 Chinese patients who underwent primary, isolated OPCAB surgery, 506 (50.39%) had PAC. Propensity score matching yielded 397 evenly balanced pairs. Compared with the no-PAC group (only implanted a central venous catheter), PAC utilization was not associated with improved in-hospital mortality in the entire or matched cohort. Still, the matched cohort showed that PAC utilization increased epinephrine usage and hospital costs. Conclusions: The current study demonstrated no apparent benefit or harm for PAC utilization in OPCAB surgical patients. In addition, PAC utilization was more expensive.

Keywords

- off-pump coronary artery bypass

- outcomes

- pulmonary artery catheter

Pulmonary artery catheters (PAC) were introduced in the 1970s by professors Jeremy Swan and William Ganz [1]. Nowadays, the classical PAC has a nearly 50-year history of clinical applications for hemodynamic monitoring. In recent years, PAC have evolved from a device capable of combining static pressure measurements of intermittent cardiac output to a monitoring tool that could continuously measure cardiac output, oxygen supply, demand balance, and right ventricular function [2]. PAC utilization was valuable in guiding treatment in critically ill and complex surgical patients [3, 4, 5, 6], especially for patients undergoing cardiac surgery [7, 8, 9, 10]. Shaw et al. [7] reported that PAC utilization was associated with decreased length of stay (LOS), reduced cardiopulmonary morbidity, and increased infectious morbidity but no increase in 30-day in-hospital mortality during adult cardiac surgery. This suggested a potential benefit of PAC utilization in cardiac surgical patients [7].

PAC provided hemodynamic data, which were used to determine treatment measures. The decisive question was whether these treatment measures improve outcomes. For patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, PAC remains the most commonly used monitoring method among cardiovascular anesthesiologists [8]. For the studies that evaluated the effect of PAC utilization on the outcomes of CABG surgical patients, very few studies reported that the benefits of PAC outweigh the risks [9, 10]; two studies reported a neutral effect of PAC on clinical outcomes [11, 12]; several studies reported the harm of PAC [13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. Given the current use of PAC in off-pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) grafting surgery, the present study analyzed records of patients undergoing OPCAB surgery with or without PAC to estimate the impact of PAC use on short-term clinical outcomes.

The Ethical Committee approved the single-center study (2019-1301). Because of the retrospective nature of this study, patient consent was waived. Patients who underwent primary and isolated OPCAB surgery from November 2020 to December 2021 were enrolled in this retrospective cohort study. Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients undergoing OPCAB combined with other valve surgery; (2) endocarditis status; (3) patients with emergent status, preoperative intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), or cardiogenic shock (as defined by the European Society of Cardiology-Heart Failure guidelines [18]); (4) previous cardiac surgery.

The patients were divided into two groups (PAC and no-PAC) based on PAC insertion status. Only patients who had PAC inserted before or during surgery were assigned to the PAC group, while all other patients were assigned to the no-PAC group. The preoperative use of PAC was not random but at the discretion of the anesthesiologist. All anesthesiologists involved in the present study were experienced cardiac anesthesiologists. For OPCAB surgical patients, the anesthesiologist decides on PAC use or not depending on various factors, considering each potential combination of patients, surgical procedures, and practice settings in low-, moderate-, and high-risk categories [19]. For the patient aspect, the anesthesiologist’s main concern is the left ventricular function (left ventricular eject fraction, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, left ventricular aneurysm), myocardial infarction (MI) within a month, severe pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH), if IABP was required before surgery, etc. With these factors, anesthesiologists will combine their experience to guide the application of PAC.

Data for the present study was obtained from the Hospital Information System and the Anesthesia Information Management System, which included detailed preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data on all hospitalized patients who underwent primary and isolated OPCAB surgery. Baseline characteristics (e.g., age, gender, height, weight, comorbidities, medications, serum creatine, and left ventricular ejection fraction), intraoperative data (e.g., the operative time, inotropic and vasoactive medication administrations, fluid infusion), and postoperative outcomes (e.g., death, complications, transfusion, mechanical ventilation duration (MVD), LOS in intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital, chest drainage duration, inotropic and vasoactive medication administrations, re-admission to ICU, reoperation, hospitalization costs) were extracted.

The primary outcome was the composite incidence of hospitalized death and

complications (e.g., cardiac arrest, new-onset atrial fibrillation, pacemaker,

myocardial infarction, low cardiac output, use of IABP and extracorporeal

membrane oxygenation (ECMO), stroke, any other neurological events, renal

replacement therapy, and pulmonary infection), which were widely used for

evaluating the quality of CABG procedures [20, 21, 22]. The composite incidence of

hospitalized complications was expressed as the number of adverse events during

the index hospitalization. The analysis was at the individual patient level, with

each type of complication counted only once [23]. Non-fatal myocardial infarction

was classed as those newly occurring postoperatively. It was defined as any of

the following in the medical record or electrocardiograph-documented Q waves that

were 0.03 seconds in width and one-third or greater of the total QRS complex in 2

or more continuous leads [20]. Low cardiac output was defined as a cardiac index

of 2.2 L/min/m

The secondary outcomes were postoperative recovery parameters (MVD, LOS in ICU and hospital, re-admission to ICU, and reoperation) and total hospitalization costs. Other comparison outcomes were intraoperative and postoperative fluid infusion, vasoactive drug, chest drainage duration, and blood product transfusion (red blood cells, plasma, platelets) between the two groups.

Blood products were transfused based on the hospital transfusion protocol. For

example, the transfusion trigger for red blood cells (RBC) was hemoglobin (HB)

Patient characteristics before and after matching were compared using p

values; p

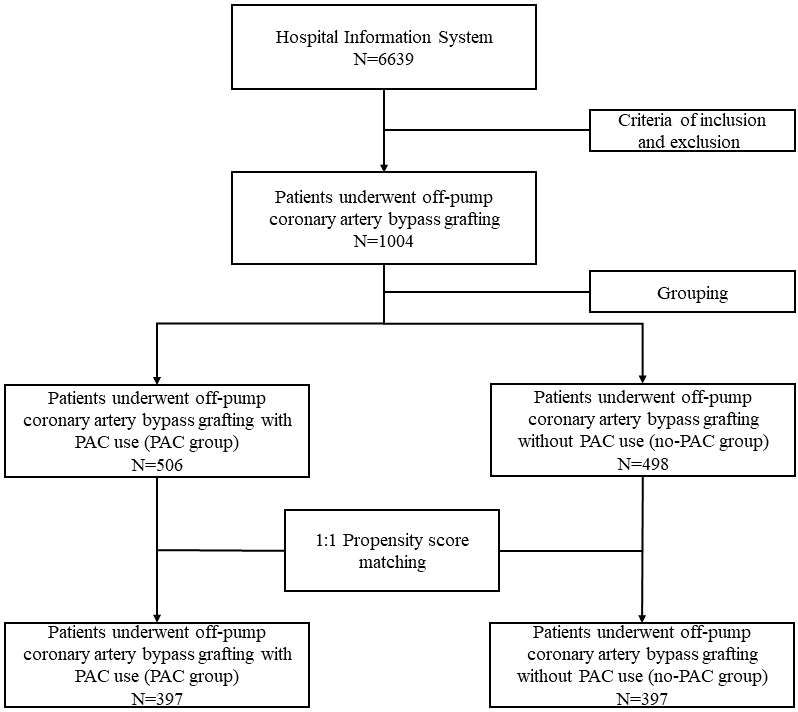

The patient enrollment is shown in Fig. 1. 1004 patients who underwent OPCAB

surgery were identified, 700 patients (69.7%) had a three-vessel disease, 196

patients (19.5%) had left main trunk disease, and 506 patients (50.4%) had PAC

use. Table 1 lists the demographic and clinical variables for the entire

unmatched and matched cohorts, analyzed by PAC insertion status. In the entire

cohort, the 1004 eligible patients showed no significant differences between the

two groups concerning age, smoking, drinking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension,

and other comorbidities. However, the patients in the PAC group had higher BMI

(25.2

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Patient enrollment. PAC, pulmonary artery catheter.

| Entire cohort | Matched cohort | ||||||

| no-PAC (n = 498) | PAC (n = 506) | p | no-PAC (n = 397) | PAC (n = 397) | p | ||

| Demographic | |||||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 63.0 (56.0, 68.0) | 63.0 (55.0, 68.0) | 0.632 | 62.00 (55.0, 68.0) | 62.00 (55.0, 68.0) | 0.890 | |

| Female, n (%) | 119 (23.9) | 107 (21.1) | 0.333 | 315 (79.3) | 310 (78.1) | 0.729 | |

| Risk factors | |||||||

| BMI, mean (SD)* | 25.2 (3.2) | 26.5 (3.2) | 25.8 (2.9) | 25.8 (2.9) | 0.993 | ||

| Smoking, n (%) | 251 (50.4) | 255 (50.4) | 1.000 | 212 (53.4) | 206 (51.9) | 0.722 | |

| Drinking, n (%) | 242 (48.6) | 235 (46.4) | 0.536 | 203 (51.1) | 195 (49.1) | 0.619 | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 330 (66.3) | 345 (68.2) | 0.562 | 268 (67.5) | 261 (65.7) | 0.652 | |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 420 (84.3) | 415 (82.0) | 0.369 | 330 (83.1) | 323 (81.4) | 0.577 | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 201 (40.4) | 198 (39.1) | 0.738 | 153 (38.5) | 161 (40.6) | 0.611 | |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 4 (0.8) | 9 (1.8) | 0.277 | 3 (0.8) | 4 (1.0) | 1.000 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| COPD, n (%) | 5 (1.0) | 6 (1.2) | 1.000 | 4 (1.0) | 5 (1.3) | 1.000 | |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 16 (3.2) | 17 (3.4) | 1.000 | 13 (3.3) | 10 (2.5) | 0.672 | |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 186 (37.3) | 183 (36.2) | 0.746 | 153 (38.5) | 150 (37.8) | 0.884 | |

| PCI, n (%) | 49 (9.8) | 35 (6.9) | 0.119 | 28 (7.1) | 30 (7.6) | 0.892 | |

| Peripheral vascular diseases, n (%) | 80 (16.1) | 74 (14.6) | 0.585 | 65 (16.4) | 64 (16.1) | 1.000 | |

| Cerebral events, n (%) | 45 (9.0) | 35 (6.9) | 0.261 | 31 (7.8) | 33 (8.3) | 0.896 | |

| Clinical profiles | |||||||

| LVEF, median (IQR) | 60.0 (55.0, 64.0) | 60.0 (55.0, 64.0) | 0.791 | 60.0 (55.0, 64.0) | 60.0 (55.0, 64.0) | 0.977 | |

| Serum creatine, median (IQR) | 84.9 (75.0, 96.0) | 84.1 (74.7, 97.0) | 0.584 | 86.1 (77.0, 98.3) | 84.1 (74.0, 97.7) | 0.186 | |

| Medications | |||||||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 85 (17.1) | 102 (20.2) | 0.239 | 72 (18.1) | 82 (20.7) | 0.419 | |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 92 (18.5) | 94 (18.6) | 1.000 | 78 (19.6) | 81 (20.4) | 0.859 | |

| 279 (56.0) | 294 (58.1) | 0.547 | 224 (56.4) | 226 (56.9) | 0.943 | ||

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 259 (52.0) | 272 (53.8) | 0.623 | 211 (53.1) | 201 (50.6) | 0.523 | |

| ACEI/ARB, n (%) | 52 (10.4) | 51 (10.1) | 0.932 | 41 (10.3) | 45 (11.3) | 0.732 | |

| Nitrates, n (%) | 330 (66.3) | 345 (68.2) | 0.562 | 268 (67.5) | 261 (65.7) | 0.652 | |

| Anti-diabetics, n (%) | 201 (40.4) | 198 (39.1) | 0.738 | 153 (38.5) | 161 (40.6) | 0.611 | |

| Statins, n (%) | 420 (84.3) | 415 (82.0) | 0.369 | 330 (83.1) | 323 (81.4) | 0.577 | |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor

blockers; BMI, body mass index; *BMI = weight (kg)/(height [m])

Table 2 presents intraoperative data for the entire and matched cohorts. The PAC

group had a more intraoperative crystalloid volume and total fluid infusion

volume (p

| Entire cohort | Matched cohort | ||||||

| no-PAC (n = 498) | PAC (n = 506) | p | no-PAC (n = 397) | PAC (n = 397) | p | ||

| Operative time, median (IQR) | 204.5 (176.0, 235.8) | 206.0 (178.0, 238.0) | 0.546 | 204.0 (175.0, 235.0) | 202.0 (176.0, 235.0) | 0.799 | |

| Anesthesia time, median (IQR) | 253.5 (217.0, 286.0) | 253.0 (220.0, 290.0) | 0.585 | 255.0 (220.0, 285.0) | 247.0 (218.0, 280.0) | 0.275 | |

| Intraoperative fluid infusion | |||||||

| Crystalloid volume, median (IQR) | 1000.0 (575.0, 1400.0) | 1000.0 (700.0, 1500.0) | 1000.0 (500.0, 1400.0) | 1000.0 (600.0, 1500.0) | 0.066 | ||

| Colloidal volume, median (IQR) | 500.0 (100.0, 500.0) | 500.0 (300.0, 500.0) | 0.061 | 500.0 (100.0, 500.0) | 500.0 (200.0, 500.0) | 0.317 | |

| Total infusion volume, median (IQR) | 1500.0 (1000.0, 1825.0) | 1500.0 (1025.0, 2000.0) | 1500.0 (1000.0, 1900.0) | 1500.0 (1000.0, 2000.0) | 0.066 | ||

| Inotropic/vasoactive agents | |||||||

| Epinephrine, n (%) | 44 (8.8) | 64 (12.6) | 0.065 | 33 (8.3) | 51 (12.8) | 0.050 | |

| Milrinone, n (%) | 38 (7.6) | 35 (6.9) | 0.754 | 29 (7.3) | 28 (7.1) | 1.000 | |

| Dopamine, n (%) | 253 (50.8) | 271 (53.6) | 0.418 | 199 (50.1) | 214 (53.9) | 0.320 | |

| Norepinephrine, n (%) | 94 (18.9) | 90 (17.8) | 0.716 | 73 (18.4) | 70 (17.6) | 0.853 | |

| Nitroglycerin, n (%) | 328 (65.9) | 335 (66.2) | 0.962 | 276 (69.5) | 262 (66.0) | 0.324 | |

IQR, interquartile range; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter. *indicates that p is statistically significant.

Table 3 presents postoperative data for entire and matched cohorts. In the entire cohort, the composite rate of mortality and mortalities occurred in 21.7% of the PAC group and 16.3 in the no-PAC group (p = 0.003). In the matched cohort, the composite rate of mortality and mortalities occurred in 22.4% of the PAC group and 16.9 in the no-PAC group (p = 0.061). Among the outcomes included in the primary composite endpoint, there was no difference in most observations between the two groups for the entire and matched cohort. Only the composite morbidity (p = 0.04) and new-onset atrial fibrillation (p = 0.008) were significantly different in the PAC group of the entire cohort but had no significant difference in the matched cohort.

| Entire cohort | Matched cohort | ||||||

| no-PAC (n = 498) | PAC (n = 506) | p | no-PAC (n = 397) | PAC (n = 397) | p | ||

| Mortality and morbidities, n (%) | 81 (16.3) | 110 (21.7) | 0.033 |

67 (16.9) | 89 (22.4) | 0.061 | |

| Mortality, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1.000 | |

| Any morbidity, n (%) | 81 (16.3) | 109 (21.5) | 0.040 |

67 (16.9) | 88 (22.2) | 0.073 | |

| New-onset atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (1.8) | 0.008 |

0 (0.0) | 5 (1.3) | 0.073 | |

| Cardiac arrest, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 1.000 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 1.000 | |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 29 (5.8) | 35 (6.9) | 0.562 | 22 (5.5) | 28 (7.1) | 0.465 | |

| Low cardiac output, n (%) | 7 (1.4) | 7 (1.4) | 1.000 | 6 (1.5) | 6 (1.5) | 1.000 | |

| Pulmonary infection, n (%) | 61 (12.2) | 67 (13.2) | 0.706 | 48 (12.1) | 56 (14.1) | 0.462 | |

| Stroke, n (%) | 9 (1.8) | 15 (3.0) | 0.320 | 8 (2.0) | 13 (3.3) | 0.376 | |

| Any neurological events, n (%) | 14 (2.8) | 17 (3.4) | 0.749 | 10 (2.5) | 14 (3.5) | 0.534 | |

| Renal replacement therapy, n (%) | 11 (2.2) | 17 (3.4) | 0.360 | 11 (2.8) | 15 (3.8) | 0.550 | |

| Pacemaker, n (%) | 4 (0.8) | 3 (0.6) | 0.983 | 4 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) | 1.000 | |

| IABP, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.8) | 0.379 | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.8) | 0.616 | |

| ECMO, n (%) | 7 (1.4) | 9 (1.8) | 0.826 | 6 (1.5) | 9 (2.3) | 0.602 | |

| MVD (h), median (IQR) | 16.00 (13.00, 18.00) | 15.00 (13.00, 18.00) | 0.257 | 16.00 (13.00, 17.00) | 15.00 (13.00, 18.00) | 0.541 | |

| LOS in ICU (h), median (IQR) | 61.00 (26.38, 93.25) | 63.00 (28.00, 93.50) | 0.634 | 62.00 (26.75, 93.00) | 51.25 (23.00, 93.00) | 0.805 | |

| LOS in hospital (d), median (IQR) | 7.00 (7.00, 9.00) | 7.00 (7.00, 9.00) | 0.345 | 7.00 (7.00, 9.00) | 7.00 (7.00, 9.00) | 0.500 | |

| Hospitalization costs (RMB), median (IQR) | 111823.48 (102965.84, 124892.44) | 118884.51 (107370.11, 133418.28) | 112071.52 (102192.40, 125116.20) | 119559.34 (107504.62, 133432.17) | |||

| Re-admission to ICU, n (%) | 6 (1.2) | 9 (1.8) | 0.625 | 5 (1.3) | 7 (1.8) | 0.771 | |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 4 (0.8) | 7 (1.4) | 0.562 | 2 (0.5) | 6 (1.5) | 0.286 | |

| Chest drainage time | 4.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 4.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 0.383 | 4.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 4.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 0.426 | |

| RBC transfusion, n (%) | 9 (1.8) | 10 (2.0) | 1 | 6 (1.5) | 8 (2.0) | 0.787 | |

| FFP transfusion, n (%) | 11 (2.2) | 13 (2.6) | 0.867 | 11 (2.8) | 9 (2.3) | 0.821 | |

| Epinephrine, n (%) | 44 (8.8) | 64 (12.6) | 0.065 | 33 (8.3) | 51 (12.8) | 0.050 | |

| Milrinone, n (%) | 38 (7.6) | 35 (6.9) | 0.754 | 29 (7.3) | 28 (7.1) | 1.000 | |

| Dopamine, n (%) | 253 (50.8) | 271 (53.6) | 0.418 | 199 (50.1) | 214 (53.9) | 0.320 | |

| Norepinephrine, n (%) | 94 (18.9) | 90 (17.8) | 0.716 | 73 (18.4) | 70 (17.6) | 0.853 | |

| Nitroglycerin, n (%) | 328 (65.9) | 335 (66.2) | 0.962 | 276 (69.5) | 262 (66.0) | 0.324 | |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; LOS, length of stay; MVD, mechanical ventilation duration; RBC, red blood cell; RMB, ren min bi; PAC, pulmonary artery catheterization. *indicates that p is statistically significant.

1 RMB = 0.1401 USD.

In the entire and matched cohorts, there was no significant difference in the

postoperative MVD, LOS in ICU and in hospital, the re-admission rate to ICU,

reoperation, RBC transfusion, and FFP transfusion between the PAC and no-PAC

groups. However, the hospitalization costs were higher (p

Since its introduction in 1970 by Professor Jeremy Swan and William Ganz [1], PAC inserted at the bedside has been used in perioperative settings as a diagnostic tool and continuously monitors various physiological and hemodynamic parameters of critically ill surgical patients [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. However, the effect of PAC-guided goal-directed treatment on morbidity and mortality has not been clearly proven, and PAC utilization has been shown to increase healthcare service and hospitalization costs [4, 9, 13, 14, 17]. The SUPPORT study involved medical and surgical patients and showed PAC utilization had increased mortality, LOS in ICU, and hospitalization costs [4]. This study raised benefit-risk concerns over PAC utilization and generated intense interest in social medicals and professional circles. The PAC-man study enrolled 1041 ICU patients from the United Kingdom (UK) and showed no difference in hospital mortality between patients managed with or without PAC [6]. Subsequent consensus statements recommended redoubled efforts at education regarding the use of pulmonary-artery catheters. Thus, PAC use has declined in ICU and non-cardiac surgery settings. For example, one study reported that PAC use decreased by 65% from 5.66 per 1000 medical admissions in 1993 to 1.99 per 1000 in 2004 in surgical and critically ill patients [27]. Another survey reported PAC utilization in heart failure (HF) patients decreased by 67.8% from 6.28 per 1000 admissions in 1999 to 2.02 per 1000 admissions in 2013 [28]. However, other studies indicated that PAC was still highly used in cardiovascular surgery. For example, Judge and colleagues surveyed 6000 members of the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (SCA) and showed that most respondents preferred using PAC for most cardiac patients [8]. Similarly, Brovman and colleagues reported that PAC utilization increased from 2010 to 2014 in cardiac surgical patients [29].

The present study analyzed records of patients undergoing OPCAB surgery with or without PAC to estimate the impact of PAC use on short-term clinical outcomes and found PAC utilization was associated with a higher likelihood of using epinephrine during intra- and postoperative settings and higher hospitalization costs. Still, it did not affect hospitalization mortality, and no significant intergroup differences in numerous adverse outcomes were noted, including stroke, neurological events, and renal replacement therapy. The effect of PAC utilization on long-term prognosis has also been reported. Xu and colleagues [17] reported that PAC use in CABG patients was neither associated with perioperative mortality and major complications, nor with long-term mortality and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Particularly for renal replacement therapy, acute kidney injury was a strong predictor of clinical outcome after cardiac surgery [30]. Besides, PAC utilization also has limited benefits for patients undergoing coronary or valvular surgery. Brovman and colleagues reported that PAC utilization was not associated with improved operative mortality in the entire cohort of (n = 11,820), matched cohort (n = 7038), and in the recent heart failure, mitral valve disease, or tricuspid insufficiency subgroups. LOS in the ICU was longer, and there were more packed RBC transfusions in the PAC group; however, postoperative outcomes were similar, including stroke, sepsis, and new renal failure [29]. Thus, PAC should only be used when it is indicated.

It is worth noting that PAC is a user-dependent diagnostic and surveillance technique and not a treatment per se. Patients who underwent OPCAB surgery may benefit from timely-targeted and effective interventions guided by the comprehensive and real-time parameters provided by PAC. The anesthesiologists’ proficiency and experience with PAC were essential. Professor Jeremy Swan [31], the inventor of PAC, suggested that physicians place at least 50 PACs annually to maintain proficiency. Schwann and colleagues reported that PAC utilization during CABG was associated with increased end-organ failure rate and hospitalization death, possibly due to overtreatment with positive inotropic drugs and intravenous fluids in the PAC cohort [16]. This study also showed increased fluid infusion and epinephrine use in the PAC group. Tuman et al. [11] hypothesized that the PAC group was more likely to use drugs, partly reflecting how monitoring and unnecessary information influenced treatment without significantly altering outcomes. These results highlighted the risk of overtreating abnormal physiological parameters.

In 2003, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) updated the practice

guidelines for PAC utilization, advising that the appropriate use of PAC should

be based on three aspects, namely patient factors, surgery factors, and practice

factors [19]. In 2021, the Chinese Society of Anesthesiology (CSA) recommended

the indications of PAC utilization for cardiac surgical patients, including left

ventricular systolic dysfunction (eject fraction

Although the ideal evaluation of PAC in clinical practice is a randomized controlled trial (RCT), this effort is time-consuming, expensive, and has limited generalization [33].

We found that during the retrieval process, there was only one RCT study on PAC in CABG surgery, and it was published in 1989, with a small sample size (226) and selection bias [34]. In fact, most were observational cohort studies. This is the first and the largest survey to evaluate the relationships between PAC in OPCAB surgery and clinical outcomes in China. The results showed no differences in hospitalization outcomes between the OPCAB patients who used PAC and those who did not, except for significantly greater intra- and post-operative epinephrine use among the PAC group.

The current study demonstrated no apparent benefit or harm for PAC use during OPCAB surgery. However, PAC utilization in OPCAB surgery was more expensive.

The limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, it is a retrospective study performed at a single center and using existing databases. The cohort could have been affected by selection bias. However, propensity score matching is used to overcome this discrepancy in the hopes of making each group more comparable regarding baseline risk. Fortunately, there are no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the PAC and no-PAC groups before propensity score-matching. Second, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and critical care physicians may have different levels of familiarity and expertise with PAC utilization, which may introduce some heterogeneity in the perioperative management of this population. Currently, there is no institutional protocol for managing hemodynamic and physiological parameters measured by PAC, which may lead to heterogeneity in perioperative care in this population. Furthermore, the effective use of PAC is an elusive variable that cannot be captured in this study. Moreover, as a single institution’s experience, all the subjects enrolled in the trial were from the same hospital in the same region, and the implications of these findings may not be fully generalizable.

The article’s data will be shared on reasonable request with the corresponding author.

CX: conceptualization, software, methodology, data collection/ curation, data analysis/interpretation, statistics, and writing-original draft. WQ, MS, LH: data collection, formal analysis, software, and critical article revision. YY: conceptualization, data collection, data analysis/interpretation, statistics, formal analysis, supervision, and critical article revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The Ethical Committee approved the single-center study (2019-1301). Because of the retrospective nature of this study, patient consent was waived.

The authors would like to thank the colleagues and statisticians at Fuwai Hospital and Fuwai Yunnan Hospital for their indispensable help with data collection and data analysis. We are also grateful to the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) 2021-I2M-C&T-B-038.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.