1 Department of Anesthesiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, 230022 Hefei, Anhui, China

2 Department of Anesthesiology, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 100037 Beijing, China

3 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Quanzhou First Hospital Affiliated to Fujian Medical University, 362000 Quanzhou, Fujian, China

Abstract

The impact of seasonal patterns on the mortality and morbidity of surgical patients with cardiovascular diseases has gained increasing attention in recent years. However, whether this seasonal variation extends to cardiovascular surgery outcomes remains unknown. This study sought to evaluate the effects of seasonal variation on the short-term outcomes of patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCABG).

This study identified all patients undergoing elective OPCABG at a single cardiovascular center between January 2020 and December 2020. Patients were divided into four groups according to the season of their surgery. The primary outcome was the composite incidence of mortality and morbidity during hospitalization. Secondary outcomes included chest tube drainage (CTD) within 24 h, total CTD, chest drainage duration, mechanical ventilation duration, and postoperative length of stay (LOS) in the intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital.

Winter and spring surgeries were associated with higher composite incidence of mortality and morbidities (26.8% and 18.0%) compared to summer (15.7%) and autumn (11.1%) surgeries (p < 0.05). Spring surgery had the highest median CTD within 24 hours after surgery (640 mL), whereas it also exhibited the lowest total CTD (730 mL) (p < 0.05). Chest drainage duration was longer in spring and summer than in autumn and winter (p < 0.05). While no significant differences were observed in mechanical ventilation duration and hospital stay among the four seasons, the LOS in the ICU was longer in summer than in autumn (88 h vs. 51 h, p < 0.05).

The OPCABG outcomes might exhibit seasonal patterns in patients with coronary heart disease.

Keywords

- seasonal variation

- off-pump

- coronary artery bypass grafting

- complications

- outcomes

The impact of seasonal patterns on the mortality and morbidity of surgical patients with cardiovascular diseases has gained increasing attention in recent years, shedding light on the complex interplay between external environmental factors and cardiovascular health [1, 2, 3]. Several contributing factors, including low temperature, respiratory infections [4], and seasonal mood changes [5], have been implicated in influencing the incidence rate and mortality of coronary heart disease. Notably, there is a discernible peak in winter and a trough in summer, suggesting a potential connection between seasonal variations and cardiovascular outcomes.

Whether seasonal variation extends to coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery outcomes has been a subject of ongoing debate. While some studies have identified seasonal fluctuations, a significant degree of inconsistency persists among these findings. For instance, a comprehensive study in the United Kingdom analyzed data from 12,221 patients who underwent cardiac surgery over ten years, revealing higher risk-adjusted hospital mortality and prolonged length of stay (LOS) during the winter months [6]. Similarly, a study by Torabipour et al. [7] in Oman found that the surgery season significantly affected the length of hospital stay after CABG, with winter showing the longest duration and summer the shortest.

Contrastingly, other research has failed to establish significant seasonal differences in surgical outcomes for CABG patients. A retrospective cohort study conducted in Turkey, comparing winter and summer surgical outcomes, concluded that despite the increased frequency of cardiovascular events in winter, early surgical outcomes of CABG remained unaffected by seasonal patterns [8]. Another study in Iran by Nemati [9] found no significant differences in postoperative mortality, morbidity, or LOS among the four seasons.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential geographical variability of these findings, preventing the derivation of generalized conclusions. Consequently, the current study aims to contribute to this discourse by assessing the correlation between seasonal variations and the outcomes of off-pump coronary artery bypass graft (OPCABG) surgery.

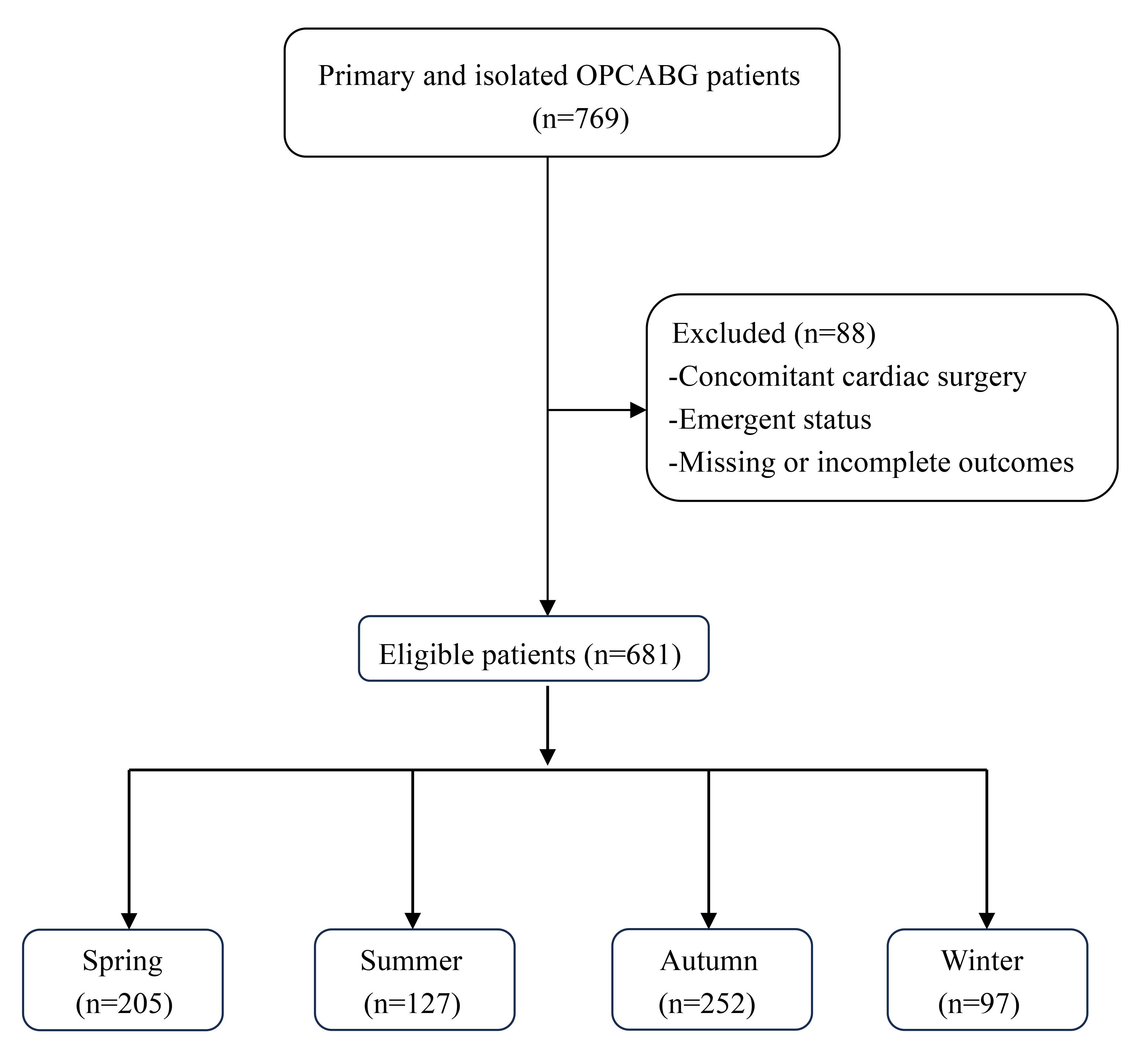

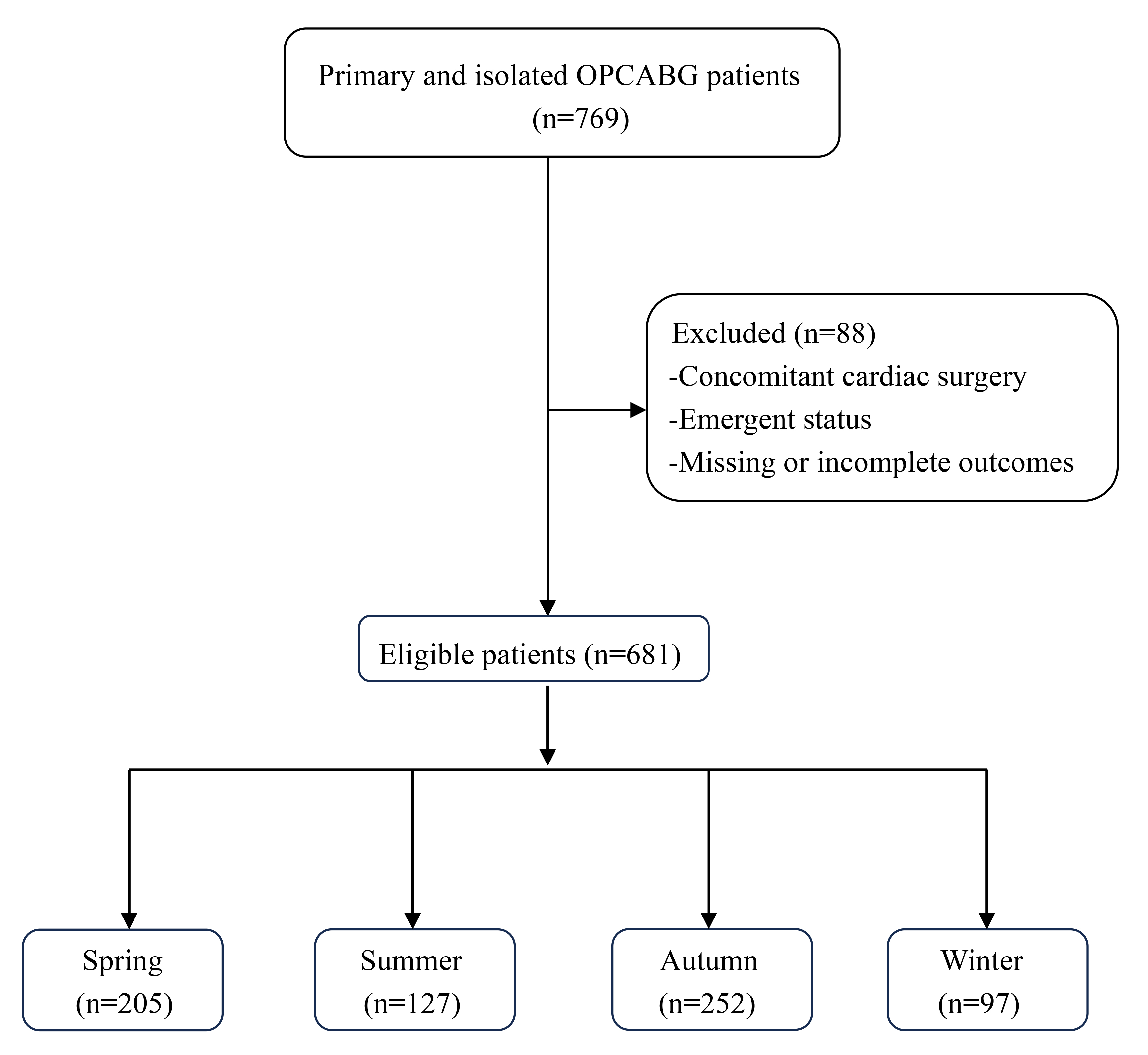

The study included consecutive patients who underwent primary and isolated

OPCABG at our hospital from January 2020 to December 2020. The inclusion criteria

comprised adult patients (

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the patient selection and categorization criteria. OPCABG, off-pump coronary artery bypass graft.

Chronic cardiac medications were continued until the morning of surgery, with

antiplatelet and anticoagulation medications discontinued preoperatively. No

anesthetic premedication was administered. Standardized anesthetic protocols were

employed, including induction with 0.2 mg/kg etomidate, 2–3 µg/kg

sufentanil, and 0.15–0.2 mg/kg cis-atracurium, and maintenance with 100–200

mg/h propofol, 30–50 ug/h dexmedetomidine, 10–20 mg/h cis-atracurium, and

0.5%–2.5% sevoflurane. Surgical procedures involved a median sternotomy, with

the left internal thoracic artery and/or great saphenous veins harvested for

coronary grafts. A heparin dose of 200 U/kg was used to achieve an activated

clotting time (ACT) of

Blood products were transfused in adherence to the hospital’s transfusion

protocol. An allogeneic red blood cell (RBC) transfusion was administered with

hemoglobin (HB)

The primary outcome was the composite incidence of in-hospital mortality and

morbidity, which included myocardial infarction (MI), low-cardiac output syndrome

(LCOS), use of intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), new-onset atrial fibrillation,

ventricular fibrillation, new pacemaker placement, acute kidney injury (AKI),

stroke, pneumonia, wound infection, reoperation, intensive care unit (ICU)

readmission, and cardiac arrest. MI was defined as an increase in cardiac

biomarkers (

Secondary outcomes included CTD within 24 h, total CTD, chest drainage duration, mechanical ventilation duration, and postoperative LOS in the ICU and hospital.

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the included OPCABG patients. There were no major differences in patient characteristics by season except for a disparity in preoperative usage of statins (p = 0.004).

| Spring (n = 205) | Summer (n = 127) | Autumn (n = 252) | Winter (n = 97) | p-value | |||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, y | 64 (57, 69) | 61 (55, 67) | 64 (57, 70) | 63 (54, 68) | 0.142 | ||

| Male sex, n (%) | 156 (76.1%) | 104 (81.9%) | 196 (77.8%) | 77 (79.4%) | 0.647 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.4 (23.7, 27.4) | 25.6 (23.5, 28.0) | 25.9 (23.7, 27.7) | 25.2 (23.2, 27.0) | 0.292 | ||

| Risk factor and comorbidities, n (%) | |||||||

| Smoking | 97 (47.3%) | 71 (55.9%) | 123 (48.8%) | 39 (40.2%) | 0.134 | ||

| Drinking | 10 (4.9%) | 9 (7.1%) | 25 (9.9%) | 12 (12.5%) | 0.088 | ||

| Hypertension | 148 (72.2%) | 82 (64.6%) | 169 (67.1%) | 62 (63.9%) | 0.370 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 91 (44.4%) | 58 (45.7%) | 99 (39.3%) | 40 (41.2%) | 0.585 | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 179 (87.3%) | 98 (77.2%) | 208 (82.5%) | 75 (77.3%) | 0.058 | ||

| COPD | 3 (1.5%) | 5 (3.9%) | 3 (1.2%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.299 | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 6 (2.9%) | 8 (6.3%) | 10 (4.0%) | 3 (3.1%) | 0.459 | ||

| Heart block | 2 (1.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 3 (1.2%) | 2 (2.1%) | 0.849 | ||

| Previous MI | |||||||

| 4 (2.0%) | 7 (5.5%) | 11 (4.4%) | 4 (4.1%) | 0.316 | |||

| 25 (12.2%) | 23 (18.1%) | 47 (18.7%) | 17 (17.5%) | 0.270 | |||

| PCI | 7 (3.4%) | 6 (4.7%) | 7 (2.8%) | 7 (7.2%) | 0.257 | ||

| Heart failure | 3 (1.5%) | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (0.8%) | 2 (2.1%) | 0.702 | ||

| Renal failure | 5 (2.4%) | 3 (2.4%) | 4 (1.6%) | 3 (3.1%) | 0.739 | ||

| Stroke | 34 (16.6%) | 17 (13.4%) | 29 (11.5%) | 8 (8.2%) | 0.189 | ||

| Peripheral vascular diseases | 15 (7.3%) | 9 (7.1%) | 8 (3.2%) | 7 (7.2%) | 0.186 | ||

| Preoperative medications, n (%) | |||||||

| 187 (91.2%) | 118 (92.9%) | 232 (92.1%) | 87 (89.7%) | 0.835 | |||

| Nitrates | 189 (92.2%) | 118 (92.9%) | 241 (95.6%) | 91 (93.8%) | 0.466 | ||

| ACEI | 27 (13.2%) | 16 (12.6%) | 49 (19.4%) | 20 (20.6%) | 0.120 | ||

| CCB | 82 (40.0%) | 47 (37.0%) | 78 (31.0%) | 36 (37.1%) | 0.231 | ||

| Insulin | 24 (11.7%) | 16 (12.6%) | 40 (15.9%) | 20 (20.6%) | 0.179 | ||

| Hypoglycemic agent | 63 (30.7%) | 39 (30.7%) | 80 (31.7%) | 27 (27.8%) | 0.919 | ||

| Statins | 188 (91.7%) | 111 (87.4%) | 230 (91.3%) | 77 (79.4%) | 0.006 | ||

| Aspirin | 50 (24.4%) | 32 (25.2%) | 54 (21.4%) | 18 (18.6%) | 0.577 | ||

| Ticagrelor | 2 (1.0%) | 5 (3.9%) | 6 (2.4%) | 2 (3.7%) | 0.225 | ||

| Clopidogrel | 34 (16.6%) | 24 (18.9%) | 46 (18.3%) | 7 (7.2%) | 0.063 | ||

| Operative parameters | |||||||

| Surgery duration, min | 211 (175, 245) | 210 (180, 255) | 205 (175, 242) | 207 (176, 240) | 0.603 | ||

| Anesthesia duration, min | 260 (222, 299) | 260 (225, 300) | 255 (225, 291) | 250 (220, 289) | 0.428 | ||

| Graft number | 3 (3, 4) | 3 (3, 4) | 3 (3, 4) | 3 (3, 4) | 0.516 | ||

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; BMI, body mass index; CCB, calcium channel blocker; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Data are presented as the number (percentage) or median (interquartile range).

As shown in Table 2, the primary outcome exhibited significant differences

(p = 0.004), with winter and spring surgeries revealing higher composite

incidence of mortality and morbidities compared to the summer (15.7%) and autumn

(11.1%) surgeries (p

| Spring (n = 205) | Summer (n = 127) | Autumn (n = 252) | Winter (n = 97) | p-value | ||

| Mortality and morbidity, n (%) | 37 (18.0%) | 20 (15.7%) | 28 (11.1%) | 26 (26.8%) | 0.004 | |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.651 | |

| Any morbidity, n (%) | 36 (17.6%) | 20 (15.7%) | 27 (10.7%) | 25 (25.8%) | 0.006 | |

| MI | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.630 | |

| LCOS | 5 (2.4%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0%) | 0.017 | |

| IABP | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 6 (2.4%) | 2 (2.1%) | 0.142 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 2 (1.6%) | 4 (1.6%) | 2 (2.1%) | 0.139 | |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.651 | |

| New pacemaker | 3 (1.5%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0%) | 0.084 | |

| AKI | 8 (3.9%) | 1 (0.8%) | 5 (2%) | 4 (4.1%) | 0.228 | |

| Stroke | 3 (1.5%) | 4 (3.1%) | 0 | 2 (2.1%) | 0.022 | |

| Pneumonia | 15 (7.3%) | 15 (11.8%) | 15 (6.0%) | 19 (19.6%) | 0.001 | |

| Wound infection | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.8%) | 0 | 0.639 | |

| Reoperation | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0%) | 0.194 | |

| ICU readmission | 2 (2.0%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0%) | 0.042 | |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.630 | |

| CTD within 24 h, mL | 640 (415, 955) | 520 (335, 675) | 480 (360, 650) | 500 (350, 610) | ||

| Total CTD, mL | 730 (500, 1100) | 940 (668, 1305) | 970 (690, 1380) | 880 (740, 1190) | ||

| Chest drainage duration, d | 4 (4, 5) | 4 (4, 5) | 4 (3, 5) | 3 (3, 4) | ||

| Mechanical ventilation duration, h | 16 (13, 18) | 16 (14, 18) | 16 (13, 18) | 16 (12, 19) | 0.687 | |

| LOS in the ICU, h | 69 (45, 98) | 88 (60, 116) | 51 (24, 96) | 68 (29, 100) | ||

| Postoperative LOS in hospital, d | 7 (7, 9) | 8 (7, 10) | 7 (7, 10) | 8 (7, 10) | 0.213 | |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CTD, chest tube drainage; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ICU, intensive care unit; LCOS, low cardiac output syndrome; LOS, length of stay; MI, myocardial infarction; OPCABG, off-pump coronary artery bypass graft.

Data are presented as the number (percentage) or median (interquartile range).

This study sought to investigate the influence of seasonality on outcomes following OPCAB in a specific center. While mortality rates were not significantly affected by the season, our findings underscore a noteworthy impact on postoperative complications and ICU length of stay.

Winter emerged as a potentially unfavorable season for OPCABG, with postoperative pulmonary infection being the most prevalent alongside severe complications. Prior research has highlighted increased risks of postoperative pneumonia, influenza, and infections during the winter season [13, 14]. The incidence of pneumonia after OPCABG showed a strong seasonal pattern, which might also apply to other cardiothoracic surgical procedures [15]. Moreover, influenza season was identified as an independent risk factor for developing acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) after cardiac surgery (odds ratio, 1.85; 95% confidence interval, 1.06 to 3.23) [16].

The underlying physiological mechanism driving seasonal variations in OPCABG outcomes appears rooted in the impact of cold exposure on coronary artery disease. Cold exposure may induce inflammatory and coagulation responses, particularly affecting vulnerable individuals [17]. Several climatic factors, such as light, temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure, can profoundly affect neurobiology, hormonal physiology, and cardiovascular function [18]. Furthermore, it has been reported that C-reactive protein levels show a seasonal dependence, being higher in winter and spring [19]. These factors may collectively contribute to a higher risk of postoperative complications when performing OPCABG in winter.

Interestingly, our study revealed that patients who underwent OPCABG in the summer tended to have longer ICU stays, which may be attributed to heat exposure on the body. Heat exposure can cause physiological changes, such as increased heart rate, blood viscosity, and coagulation [20], leading to poor prognosis after OPCABG, which may also be mediated by other factors such as the occurrence of heart failure, conduction disturbances, and arrhythmias [21, 22]. In addition, a lower rate of OPCABG surgeries was performed in winter, which was inconsistent with the epidemiology of coronary heart disease. This discrepancy may reflect the influence of the traditional Chinese festival of Spring Festival, as patients might favor conservative treatment or coronary stenting over OPCABG surgery due to traditional cultural values or beliefs [23].

Notably, although difficult to interpret, the variations in postoperative bleeding observed in our study raise intriguing questions about potential seasonal factors influencing hemostasis and coagulation [24]. Weather-related factors, patient physiology variations, or other seasonal dynamics may contribute to this phenomenon [25]. Thus, clinicians and surgical teams should be attuned to these seasonal nuances, adjusting strategies for managing intraoperative bleeding during autumn to optimize patient outcomes [26].

Our study has some limitations. First, as a retrospective cohort study, the methodology contains some inherent biases. Unmeasured or uncontrollable confounders remained, such as admission variations or staff differences. Second, the single-center characteristic of the study limits the generalizability and applicability of these results. Third, our study only addressed in-hospital events and did not capture long-term outcomes. Lastly, the study only describes the association between the seasons and OPCABG outcomes, meaning an explanation of causal mechanisms cannot be established.

In conclusion, our study provides valuable insights into the nuanced impact of seasonality on OPCABG outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease. More large-scale, multicenter, prospective studies are warranted to examine the effects of seasonal variation on the clinical outcomes of this population.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

YTY designed the research study. LW and PSL performed the research. LW analyzed the data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuwai hospital (Protocol No. 2019-1301). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for written informed consent was waived.

The authors would like to thank the colleagues and statisticians at Fuwai Hospital for their indispensable help with data collection and data analysis. During the preparation of this work, the authors used chatGPT in the writing process to improve the language and readability of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.