1 Key Laboratory of Vascular Biology and Translational Medicine, Medical School, Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, 410208 Changsha, Hunan, China

2 College of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine, Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, 410208 Changsha, Hunan, China

Abstract

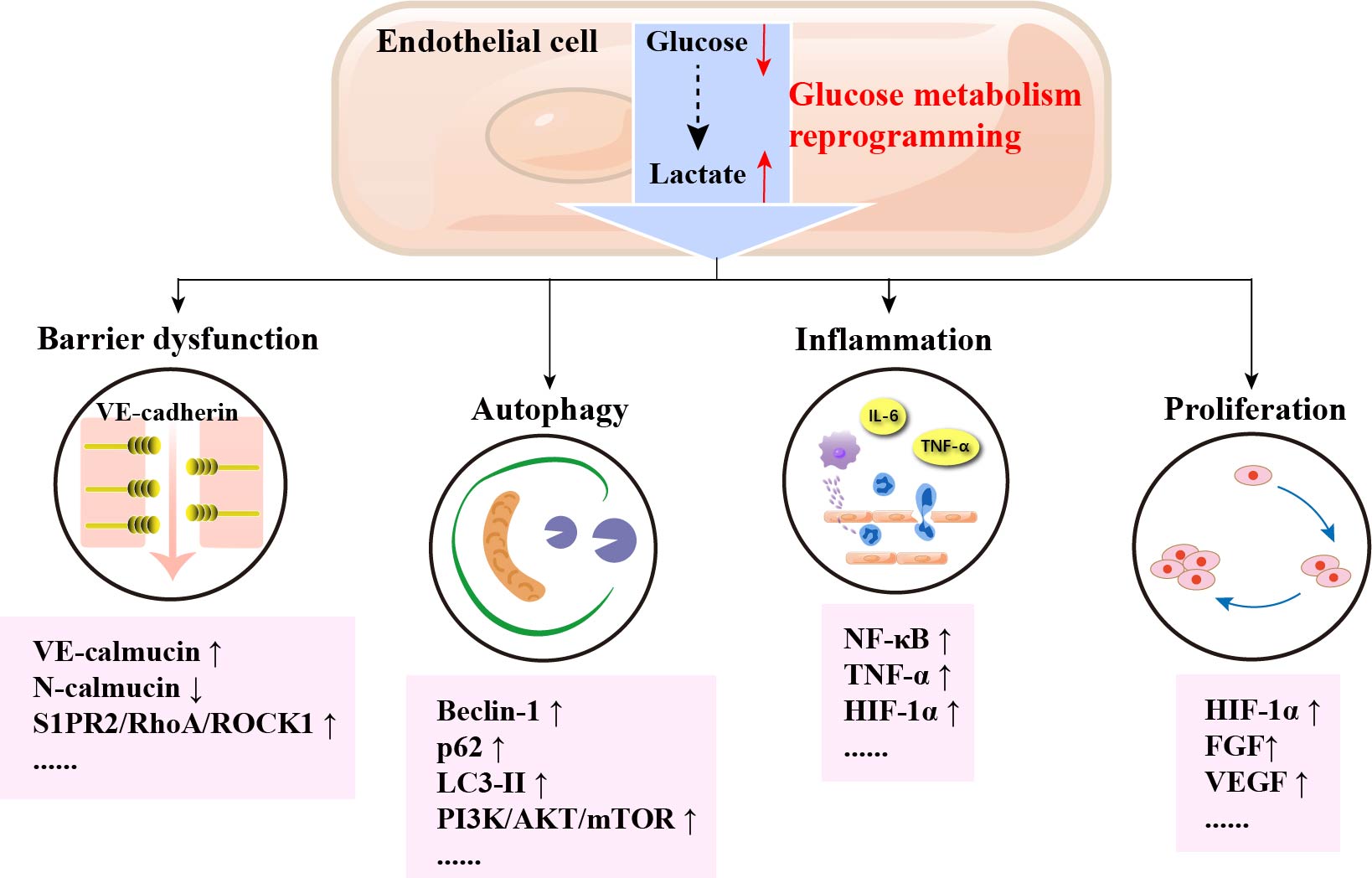

Atherosclerosis (AS) is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in cardiovascular diseases such as coronary atherosclerotic heart disease and stroke. As the primary natural barrier between blood and the vessel wall, damage to vascular endothelial cells (VECs) is one of the initiating factors for the development of AS. VECs primarily use aerobic glycolysis for energy supply, but several diseases can cause altered glucose metabolism in VECs. Glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs is the core event of AS, which is closely related to the development of AS. In this review, we review how glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs promotes the development of AS by inducing VEC barrier dysfunction, autophagy, altering the inflammatory response, and proliferation of VECs, in the hopes of providing new ideas and discovering new targets for the prevention and treatment of AS.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- vascular endothelial cells

- glucose metabolism

- atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis (AS), is a chronic disease characterized by lipid deposition in large and medium-sized arteries and the eventual formation of plaques that block blood flow, and forms an important pathological basis for the occurrence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [1]. This pathological process involves the abnormal proliferation and apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells (VECs), smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts, especially the early dysfunction of VECs [2, 3] and reprogramming of glucose metabolism, all of which are closely related to the occurrence of AS.

In the early stages of AS, in the presence of risk factors such as hypertension, hyperglycemia, and nicotine from cigarette smoke, VECs are damaged and destroyed, leading to increased vascular endothelial permeability, which causes lipoproteins to aggregate in the subendothelial space. Simultaneously, VECs are activated to recruit leukocytes and monocytes from the blood [4]. Monocytes differentiate into macrophages after activation and engulf and digest oxidized lipoproteins to form foam cells. Foam cells gradually die and accumulate to form fatty streaks and plaques [5]. Subsequently, fatty streaks and plaques, together with cholesterol crystals, dense collagen fibers, and scattered smooth muscle cells and other components, form a fibrous cap, which eventually evolves into a plaque and promotes thickening and stiffening of the arterial blood vessel wall [6]. Therefore, the basic pathophysiological process of AS involves multiple cellular components (Fig. 1). Endothelial cell damage in the vascular wall is considered to be one of the risk factors for the occurrence of AS [7].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The development of atherosclerosis. Vascular endothelial cells (VECs) are damaged and destroyed. VECs recruit leukocytes and monocytes from the blood. Monocytes differentiate into macrophages after activation and engulf and digest oxidized lipoproteins to form foam cells. Foam cells gradually die and accumulate to form fatty streaks and plaques. Subsequently, fatty streaks and plaques, together with cholesterol crystals, dense collagen fibers, and scattered smooth muscle cells and other components, form a fibrous cap. LDL, low-density lipoprotein; ox-LDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein.

Thickness or hardening of the blood vessel wall and plaque formation caused by AS may obstruct blood flow, and leads to a variety of cardiovascular diseases. Currently, AS has become a major challenge to human health [8], and cellular dysfunction. Alterations in vascular development and structure caused by glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs are closely related to the occurrence of AS [9, 10]. Therefore, the study of glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs will provide new strategies for their prevention and treatment. This review summarizes the glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs and its significance in the development of AS, providing new ideas for the prevention and treatment of AS.

VECs are squamous epithelium located on the inner surface of blood vessels. As the primary natural barrier between blood and the vessel wall, VECs form a barrier through adherence and tight junctions between cells to avoid the entry of macromolecules such as lipoproteins and leukocytes. Adherence junctions are the more prevalent connection and are the determining factor for the barrier function of VECs [11]. Healthy VECs are usually stationary, but under the stimulation of hemodynamic changes, harmful substances and other factors, cell connections and their structural integrity are disrupted, which in turn provides the necessary conditions for lipid deposition, macrophage recruitment, and foam cell formation [12]. Therefore, damage to VECs is one of the initiating factors for the occurrence and development of atherosclerosis [13, 14, 15].

When quiescent VECs are activated, they accelerate the development of AS by causing platelet agglutination and stimulating platelets to secrete platelet-derived growth factors which promote abnormal proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells to form fibromuscular plaques. Injured VECs release cytokines such as active monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), P-selectin and E-selectin, to recruit monocytes to the subendothelium and induce monocytes to transform into pro-inflammatory macrophages. In turn, macrophages and the massive accumulation of foam cells exacerbate inflammation by releasing interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, TNF-

Apoptosis of VECs has been found to be associated with the development of AS. Apoptosis of VECs causes a loss of their ability to regulate lipid homeostasis, immunity and inflammation. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) is considered to be one of the key factors in the induction of apoptosis in VECs. Ox-LDL produces lipid peroxides and induces apoptosis of VECs, inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and prevents the repair of VECs, promotes increased activity of the apoptosis-promoting proteins Bax, caspase9 and caspase3, and decreased expression of the anti-apoptotic protein b cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) during oxidation [18]. The autophagic process is a self-protective mechanism to maintain the homeostasis of the intracellular environment. A study found that VECs which induce the formation of atheromatous plaques have the typical autophagic features such as increased expression of microtubule-associated proteins light chain 3 (LC3) and myelin-like structures, and increased vacuole formation [19]. Cav-1 deficiency plays a protective role by activating autophagic flux and attenuating the response of VECs to atherogenic cytokines [20]. In summary, damaged VECs and dysfunction of VECs including pro-coagulation, pro-inflammation, pro-proliferation, induction of apoptosis and autophagy, are closely related to the development of AS.

Glucose is the main energy source of vascular endothelial cells. Glucose is first absorbed in the periphery of cells and aggregates at intercellular junctions. Subsequently, VECs will absorb glucose through a diffusion pathway mediated by glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), which does not involve energy consumption [21]. After glucose is absorbed into VECs, it catalyzes the production of glucose 6 phosphate (Glu-6-P) under the action of hexokinase (HK). Simultaneously, glucose regulators phosphofructokinase-2/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), utilizing their high kinase activity to generate 2,6-fructose diphosphate (Fru-2,6-P2), thereby activating the rate-limiting enzyme phosphofructose kinase-1 (PFK1). Under the catalysis of PFK1, Glu-6-P phosphorylates to produce fructose 1,6-diphosphate (Fru-1,6-P2), and subsequently is converted to pyruvate, which can not only be catalyzed to lactate by lactate dehydrogenase, but also can be catalyzed to acetyl-coA delivery to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [22]. The majority of normal cells in the body derive their energy from oxidative phosphorylation of the mitochondria. However, most tumor cells rely on aerobic glycolysis. Therefore, under aerobic conditions, they still choose the glycolysis pathway to generate energy, resulting in high glucose utilization and lactate secretion [23]. VECs also primarily use aerobic glycolysis for energy supply. Under physiological conditions, due to the inhibitory effect of glucose on mitochondrial respiration, less than 1% of glucose-derived pyruvate can be utilized in the TCA cycle, and this pathway accounts for only 15% of the total adenosine triphosphate (ATP) produced by VECs [24]. In comparison, up to 85% of ATP in VECs is produced by glycolysis, whose expression greater than glycolysis in other cell types [25]. Aerobic glycolysis results in far lower ATP production than oxidative phosphorylation. In addition, aerobic glycolysis can produce a large number of basic raw materials required for biosynthesis [3], therefore VECs prefer to rely on this energy metabolism pathway to meet their energy needs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Normal glucose metabolism process in vascular endothelial cells. Absorbed into VECs, glucose catalyzes the production of glucose 6 phosphate (Glu-6-P) under the action of hexokinase (HK). Simultaneously, phosphofructokinase-2/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) generate 2,6-fructose diphosphate (Fru-2,6-P2), thereby activates the rate-limiting enzyme PFK1. Under the catalysis of PFK1, Glu-6-P phosphorylates to produce Fru-1,6-P2, and Fru-1,6-P2 is subsequently converted to pyruvate, which can be catalyzed to lactate by lactate dehydrogenase or enter tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. GLUT, glucose transporter; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; VECs, vascular endothelial cells; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase A; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; G3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; PFK1, phosphofructokinase 1.

Abnormalities of glucose metabolism of VECs is mainly characterized by increased expression and transcription of glycolytic genes, increased glycolytic flux, and significantly suppressed intracellular oxidative phosphorylation. A study found that mechanical low shear stress, hypoxia, hyperglycemia and several other specific environments can cause altered glucose metabolism in VECs [26].

VECs are simple squamous epithelium which are in direct contact with blood, and regulate their biological functions such as proliferation, differentiation and migration by sensing the mechanical forces generated by blood flow and translating them into corresponding biochemical signals [27]. Low shear stress (LSS) is the frictional force generated by blood flow impinging on the vessel wall, and its magnitude is closely related to the direction of blood flow, flow rate, and viscosity [17]. Arterial branches and curvatures where blood flow is uneven will induce LSS or oscillatory shear stress (OSS), leading to remodeling of the vessel wall, which results in VEC dysfunction, resulting in oxidative stress and endothelial metabolic dysfunction, resulting in phenotypic changes in VECs [28]. Meanwhile, low and disturbed shear stress (DSS) mediates the metabolism of VECs and promotes the AS process by reducing Krüppel-like transcription factor 2 (KLF2) through ox-LDL and hyperglycemia [29]. Compared with LSS, amp-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activated by pulsatile shear stress (PS) at straight parts of arteries can promote phosphorylation of the Ser-481 site of glucokinase regulatory protein (GCKR), resulting in decreased activity of hexokinase 1 (HK1), which attenuates glycolysis of VECs [30]. Study has found that Pim1 may effectively regulate the glycolysis of VECs through PFKFB3 in laminar shear stress [31]. In addition, the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1

Increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and decreased nitric oxide (NO) in VECs are stimulated by hypoxic factors. NO can mediate the endothelium-dependent vasodilation required for normal vascular homeostasis and inhibit platelet aggregation, vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and other key events in atherosclerosis [33]. Study has found that VECs cultured under hypoxic conditions had an increased rate of glucose transport and produced more lactate [34]. Interestingly, low levels of oxidative phosphorylation produce less ROS. Despite their proximity to a hyperoxic environment, VECs have reduced levels of oxidative stress, which protect it from ROS-induced cell death [35]. GLUT1 expression is upregulated in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) after being stimulated by hypoxia and promotes ROS-driven HIF-1

Hyperglycemia is also one of the main causes of glucose metabolism reprogramming induced by VECs. It was shown that high glucose environment stimulated the increased expression of PFKFB3 protein in HUVECs. In contrast, inhibition of PFKFB3 significantly attenuated pathological angiogenesis induced by a high glucose environment and reversed the low expression of the protective factor phosphorylated protein kinase B (pAKT), in high glucose environments [41]. The expression of PKM2 was significantly upregulated in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells stimulated by high-glucose factors, and inhibition of PKM2 reversed the damage and apoptosis of VECs in high-glucose conditions [42]. In addition, hyperglycemia can induce cells to produce macromolecules and energy through glycolytic side pathways to maintain stable internal metabolic regulation [43]. The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and the polyol pathway (PP) are side branch pathways of glycolysis. Inhibition of glucose-6-phosphate entry into the pentose phosphate pathway under hyperglycemic conditions leads to reduced proliferation and migration of VECs. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency increases ROS by reducing glutathione (GSH), which in turn activates the transforming growth factor-

VECs upregulate glycolytic fluxes to resist the hypoxic environment and maintain normal ATP levels under low shear stress, hypoxic stimulation, and stimulation by high glucose factors. In addition, glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs may promote proliferation, oxidative stress, and inflammatory activation of VECs, which may ultimately lead to the development of AS (The process of glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs is shown in Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs. Pulsatile shear stress (PS) activated AMPK, which can promote phosphorylation of the Ser-481 site of GCKR to inhibit the activity of HK1. The expression of HIF-1

Glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs is significantly related to the progress of AS. During the early stages of atherosclerosis, superoxide generated by NADPH oxidases originating from VECs plays a different role to the development of AS. NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) activates eNOS to improve vascular function, but accumulating ROS induces VEC barrier dysfunction and vasoconstriction to promote inflammation and thrombosis [49]. Under the stimulus of plaque composition such as ox-LDL, VECs and macrophages induce high glucose-induced NADPH oxidases to generate ROS, then upregulate the expression of adhesion molecules, which lead to altered glycolytic flux and accumulated intermediates. The generation of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate is subsequently altered and influences the progress the atherosclerosis [50, 51]. Study suggests that vascular endothelial dysfunction takes place before the development of atherosclerosis. The first step in atherosclerotic plaque formation is that the inflammatory response is triggered and fatty streaks appear. Hyperglycemia induces the glycosylation of proteins and phospholipids, which subsequently increase oxidative stress. Products such as glucose-derived Schiff base and nonenzymatic reactive products form chemically reversible early glycosylation products, are rearranged to form more stable products, to produce AGEs after undergoing a series of complex chemical rearrangements. AGEs generate ROS which increase damage from oxidative stress and accelerate the process of atherosclerosis [52].

In susceptible areas of atherosclerotic plaques, the increased glycolytic flux of VECs can induce inflammation and other lesions, promoting further development of the middle stage of AS. Recently, it has been shown that blood flow turbulence can promote the glycolysis of VECs [53]. The disturbed flow in vulnerable regions prone to atherosclerosis enhances the expression and activities of protein kinase AMP-activated catalytic subunit alpha 1 (PRKAA1/AMPK

The expression of HIF-1

Several mechanisms of glucose metabolism in the reprogramming of VECs in atherosclerosis have been discovered, such as VECs barrier dysfunction, autophagy in VECs, inflammation of VECs, and proliferation of VECs. The detailed mechanism of glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs in atherosclerosis are shown in Table 1 (Ref. [54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80]).

| Modeling method | Mechanism of action | Pharmacological action | References |

| Adeno-associated virus 1 | Pro-inflammatory signal pathway | Ox-LDL, LOX-1 | [54] |

| ICAM-1, VCAM-1 | |||

| CCL5, CXCL1 | |||

| ERK1/2, p38 | |||

| Endothelial inflammatory reaction | |||

| TNF- | NF- | SELE, VCAM-1, IL-6 | [55] |

| Intermediate factor | |||

| Endothelial inflammation | |||

| DSS, LPS | S1PR2/RhoA/ROCK1 | Endoplasmic reticulum stress | [56] |

| SiGLUT1 | Lactic acid signaling pathway | MCT1, MCT5, MCT8 | [57] |

| Lactic acid metabolism | |||

| BEG 10 µmol/L | PI3K/Akt/eNOS/NO antioxidant signaling pathway | ROS, LDH, MDA | [58] |

| SOD | |||

| Akt | |||

| eNOS phosphorylation | |||

| NO | |||

| Endothelial cell viability | |||

| EGCG 100 µM | Glycolysis pathway | Angiopoietin-2 secretion | [59] |

| Endothelial cell proliferation, migration, invasion | |||

| Barrier function | |||

| Lactic acid 10 mM | HMGB1 | YAP, SIRT1, HMGB1 | [60] |

| HMGB1 exosomes release | |||

| Streptomycin 100 µg/mL | Glucose metabolism signal pathway | MCT1, MCT4 | [61] |

| VCAM-1, VE-cadherin | |||

| VEGFa, VEGFR2 | |||

| TGF- | |||

| Endothelial cell migration andproliferation | |||

| In vitro angiogenesis | |||

| AGEs | Profilin-1 RhoA/ROCK1 | RhoA, ROCK1 | [62] |

| ROS | |||

| Endothelial dysfunction | |||

| Oxidative stress | |||

| FGF2 10 IU/mL | mTOR | P8 protein, ROS | [63] |

| Mitochondrial membrane potential | |||

| Apoptosis | |||

| Angiogenesi | |||

| Rapamycin | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | MiRNA-155, LC3-II | [64] |

| P-mTOR/mTOR | |||

| Autophagy | |||

| NAR 100 mg/kg | Inflammation signaling pathway | TC, TG, LDL-C, TNF- | [65] |

| ALT, MDA | |||

| HDL-C, SOD, GSH-Px | |||

| Autophagy | |||

| ECGS 1% | MitoQ | NF- | [66] |

| ROS | |||

| VE-cadherin decomposition | |||

| Actin cytoskeleton remodeling | |||

| Autophagy | |||

| Ang-II | SESN2/AMPK/TSC2 | mTOR phosphorylation | [67] |

| Oxidative stress | |||

| Autophagy | |||

| Endothelial progenitor cell injury | |||

| LDL 50 µg/mL | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | P62 | [68] |

| LC3-II, IR, LDLR | |||

| mTOR, Akt, GSK3 | |||

| Glucose uptake | |||

| Autophagy | |||

| TNF- | NF- | VCAM-1, ICAM-1 | [69] |

| LC3-II | |||

| Angiogenesis in plaque | |||

| Cardiac function | |||

| Ang II | PKM2 | EndoMT | [70] |

| PKM2 | |||

| Synthetic VSMC marker | |||

| Endothelial cell transformation | |||

| Palmitate 200 µM | PINK1 | P-Drp-1/Drp-1 | [71] |

| Fis1 | |||

| Mfn2, Nix, LC3B | |||

| Oxidative stress | |||

| Mitochondrial autophagy | |||

| Ox-LDL 50 µg/mL | Let-7e | lnc-MKI67IP-3 | [72] |

| I | |||

| NF- | |||

| Nuclear translocation | |||

| Inflammation | |||

| Adhesion molecule | |||

| Amaryl novoNorm | Inflammation and oxidation pathway | GSH | [73] |

| HsCRP, IL-6, TNF- | |||

| MDA | |||

| Intima thickness of artery | |||

| Glucan 40 mM | HIF-1 | ROS, NOX4, HIF-1 | [74] |

| PDK1 | |||

| Glycolytic enzyme | |||

| Inflammation | |||

| Mitochondrial respiratory ability | |||

| E06-scFv 5 µg/mL | OxPL | TNF- | [75] |

| Cholesterol | |||

| Aortic valve calcification | |||

| Inflammation | |||

| Toluene thiazine 20 mg/mL | PFKFB3 | VLDL, LDL, HDL | [76] |

| Glycolysis | |||

| GLUT3 | |||

| Inflammation | |||

| Cone plate flow system | PRKAA1/AMPK | PRKA, AMPK | [77] |

| Glycolysis | |||

| Slc2a1, PRKAA1 | |||

| Endothelial cell proliferation | |||

| Endothelial vitality | |||

| EGF 0.1 ng/mL | TNF- | TNF-R1 | [78] |

| VEGF, HIF-1 | |||

| Angiogenesis | |||

| P65 phosphorylation | |||

| Gibco 0.1 mg/mL | PFKFB3 | MMP, dvWF | [79] |

| VEGFR-2 | |||

| Endothelial differentiation | |||

| Glycolysis | |||

| Angiogenesis | |||

| Penicillin 100 U/mL | PFK15 | Glucose intake | [80] |

| Streptomycin 100 µg/mL | Endothelial cell migration | ||

| Endothelial cell proliferation | |||

| Glycolytic activity |

Abbreviation: VECs, vascular endothelial cells; TNF-

Vascular endothelial barrier dysfunction is one of the factors in the development of AS. The main features of barrier dysfunction in VECs are disruption of intercellular junctions resulting in increased permeability, the entry of monocytes and leukocytes into the vessel wall causing structural damage, and the aggregation of plasma low-density lipoproteins under the endothelium [81]. In addition, a large number of neutrophils are recruited to VECs, resulting in an interaction between endothelial injury and the inflammatory response, which eventually leads to endothelial barrier dysfunction. There is convincing evidence that in the vascular endothelium, disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10 (ADAM10) can inhibit AS lesion occurrence by inhibiting pathological angiogenesis and ox-LDL-induced inflammation to regulate barrier function [54]. NF-

Glucose metabolism reprogramming plays an important role in mediating impaired vascular endothelial function. Study has found that activated pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHC) reverses the glycolysis of HUVECs, while PDHC remains dephosphorylated to reduce lactate production and prevent HUVEC barrier dysfunction [56]. In turn, the glycolytic product lactate also has an effect on the barrier function of VECs. A study found that knocking down GLUT1 protein in mice, which decreases the accumulation of lactate in VECs, can lead to blood-brain barrier rupture and increased permeability [57]. Furthermore, in an endothelial barrier model constructed from HUVEC monolayers, the activation of

In contrast, a study has also demonstrated that increased glycolytic flux promotes endothelial cell dysfunction and can damage barrier function by affecting the level of VE-calmodulin, particularly on endothelial cells [59]. Increased lactate induces extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-dependent activation of calpain1/2 for VE-calmucin hydrolysis, enhancing VE-calmucin endocytosis and increasing cell permeability in VECs [60]. 3PO (3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one), as an inhibitor of glycolysis, can enhance the vascular barrier by inhibiting VE-calmucin endocytosis and promoting pericytes by upregulating N-calmucin adhesion, or inhibiting the expression of adhesion molecules in VECs by inducing NF-

In summary, glucose metabolism reprogramming, especially abnormal glycolysis, induces a bidirectional effect on the alteration of VECs barrier function. Glycolysis can not only reduce VECs barrier function damage, but also can promote VECs barrier dysfunction and increased permeability, which affects the development of AS, which is dominated by the protective effect on endothelial barrier function.

Autophagy in VECs is a form of programmed cell death that participates in different stages of AS [84]. In the early development of atherosclerosis, autophagy in VECs stabilizes the formation of plaques and maintains endothelial integrity by reducing endothelial inflammation, oxidative stress, and endoplasmic reticulum stress [85]. In the late stages of atherosclerosis, due to insufficient autophagy, VECs are unable to clear the damaged organelles and denatured proteins, leading to increased intracellular oxidative stress and damage to VECs, promoting the development of AS [86]. Study has found that rapamycin can slow the formation of atherosclerotic plaques by activating autophagy [87]. Naringenin can inhibit inflammation and oxidative damage by inducing autophagy of VECs, thereby reducing the occurrence and development of AS [63]. These results indicate that normal autophagy levels are the main mechanism for delay of the development of AS. However, elevated levels of HUVEC autophagy induced by endostatin cause cell death [64]. Therefore, the autophagy of VECs has a dual role in regulating its survival and death. In addition, autophagy is also involved in the regulation of major functions in VECs, including angiogenesis, thrombosis, and NO production [65].

The relationship between autophagy and glucose metabolism in VECs has not been fully elucidated. A study found that the phosphatidylinositol3 kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) signaling pathway not only induced GLUT1 transport into the cell membrane thus promoting glucose metabolism, but also inhibited autophagy induced by mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mTOR) and prevented the occurrence of cardiovascular diseases such as AS [66]. Endothelial cell (EC)-specific sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) transgenic mice reduced endothelial cell transition. Furthermore, knocking out SIRT3 could inhibit the maturation of the hyperacetylafion of endogenous autophagy-regulated gene5 (ATG5) and up-regulate the expression of PKM2 dimer, demonstrating that SIRT3 can regulate endothelial-mesenchymal transition by improving the autophagy degradation and glucose metabolism of PKM2 [67]. Study also indicated that the expression levels of Parkin, light chain 3 beta (LC3B)-II and beclin1 mitochondrial autophagy-related proteins were down-regulated in glucose/palmitic acid-treated rat aortic endothelial cells [68]. Additionally, the autophagy of HUVECs is significantly inhibited in a high glucose environment, manifested by up-regulation of Beclin-1, LC3-II protein and gene levels, and down-regulation of p62 gene and protein expression levels [69]. Tumor protein 53 (TP53)-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator can effectively regulate the pentose phosphate pathway of VECs, up-regulate the expression of NADPH, and then inhibit excessive autophagy, which protects blood vessels [70]. Therefore, enhanced glucose metabolism can mediate the inhibition of autophagy and protect blood vessels. The inhibition of glycolysis can also treat AS by inhibiting autophagy of VECs. A study found that 3PO, a glycolysis inhibitor, could reduce the intracellular content of fructose 2,6-bisphosphate and inhibit the formation of coronary artery plaques in mice and improve cardiac function, via inhibiting the NF-

In the early stage of atherosclerosis, the activated VECs stimulate various inflammatory cells, which secrete relevant inflammatory factors involving in all stages of AS [72]. The metabolic reprogramming of VECs plays an important role in this process, which contributes to increased expression of inflammatory genes. VECs exposed to disturbed flow can promote lactate production by upregulating glycolytic flux to activated macrophages and other immune cells via the NF-

Lipoproteins(a) [Lp(a)] can bind to plasma apolipoproteins(a) [Apo(a)] and form oxidized phospholipids (OxPLs), which plays a significant role in promoting inflammation in VECs [74]. Lp(a) has been shown to activate VECs by mediating PFKFB3 and GLUT1-regulated glycolysis [89]. The activated VECs further promote adhesion and migration of monocytes [75]. In addition, glycolysis mediated by PFKFB3 can help to activate macrophages and VECs, thereby causing inflammation and promoting the formation of atherosclerotic plaques [90]. Study also confirmed that treatment of VECs in mice with 3PO suppressed an inflammatory macrophage, M1, and promoted an anti-inflammatory macrophage, M2, to stabilize the atherosclerotic plaque [91]. The altered flow can activate HIF-1

Under the influence of ischemia, hypoxia, inflammation and other factors, VECs can stimulate the release of VEGF and fibroblast growth factor (FGF). VECs change from a static state to an active state, allowing VECs to differentiate into terminal cells with high migration ability and stalk cells with proliferation ability, and then stabilize and lengthen new blood vessels. Additionally, glycolysis levels increase to provide energy for vascular development [78, 93, 94]. PFKFB3-mediated glycolysis plays an important role in endothelial differentiation and angiogenesis [95]. Alpha-mangosteen inhibits aerobic glycolysis, thereby reducing angiogenesis mediated by HIF-1

Ensuring that VECs have the ability to maintain the integrity of the vascular monolayer barrier has been found to be critical for the prevention of AS [99]. Researchers established an in vitro mouse model and found that PRKAA1 could enhance glycolytic flux and induce the proliferation of VECs by mediating the AMPK and the HIF-1

Evidence from basic and clinical studies suggests that clinically used drugs and drug candidates with varying structures and mechanisms of action can improve multiple aspects of endothelial dysfunction, and most of these drugs have shown promising cardiovascular protective effects in preclinical and clinical studies. Details of the studies (summarized) in this review, including drug names, mechanisms of action, clinical applications, and citations, are summarized in (Table 2, Ref. [102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113]).

| Drug | Mechanism of action | Clinical application | References |

| Antihypertensive drugs (including ACEI, ARB, CCB, and | ARBs, CCBs, | Arterial blood flow disorders | [102, 103, 104, 105] |

| Endothelial function | Ankle blood pressure | ||

| ACEI and ARB: | The femoral vascular resistance | ||

| ROS production | Lipoprotein | ||

| Vasoconstrictor production | |||

| Endothelial function | |||

| VE-PTP inhibitors | Tie2 phosphorylation | Endothelial barrier | [106] |

| eNOS | Blood flow shear force | ||

| VEGFR2 dephosphorylation | Blood pressure | ||

| Glycocalyx-targeted agents | NO-mediated vasodilation | Arterial dysfunction | [107] |

| Endothelial function in mice | Brachial artery flow-mediated dilation | ||

| eNOS enhancer (AVE3085), Antioxidants (including vitamin C/E, NAC, erdosteine, carbocysteine and genistein etc.) | The expression of eNOS | Cardiovascular function | [108, 109] |

| NO production | Vasomotor response | ||

| Oxidative free radical | |||

| Endothelial dysfunction | |||

| Anti-inflammatory drugs (including canakinumab, colchicine, inflammasome inhibitors, NSAIDs, resolvins) | Neutrophil chemotaxis | Atherosclerotic thrombotic | [110, 111] |

| NLRP3 inflammasome | CRP | ||

| Endothelial inflammation | LDL | ||

| IL-1 | |||

| Anti-diabetic drugs (including insulin, metformin, SGLT2i, GLP1RA, DPP-4i) | Pro-inflammatory mediators | Blood glucose | [112, 113] |

| Vascular redox homeostasis is maintained | Frequency of hypoglycemia | ||

| Endothelial function | Glycosylated hemoglobin is stable in the normal range | ||

| Arterial dysfunction | |||

| Blood pressure | |||

| LDL | |||

| Anti-platelet |

Abbreviation: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; VE-PTP, vascular endothelial tyrosine phosphatase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthases; NAC, acetylcysteine; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SGLT2i, sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor; GLP-1RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; DPP-4i, DPP-4 inhibitors; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Tie2, angiopoietin-1 receptor tyrosine kinase; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2; NO, nitric oxide; NLRP3, nlr family pyrin domain containing 3; CRP, c-reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; IL-1

Metabolism in VECs is of great interest but has been understudied. Glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs can induce vascular dysfunction and the development of AS. Glucose is the main source of energy metabolism in VECs. Alterations in glucose metabolism under pathological conditions may also promote the development of AS. Glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs in atherosclerosis promotes autophagy and inflammation which contributes to the formation and occurrence of AS. There are many pathways involved in glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs (Fig. 4). Among them, glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs mediated by the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, the NF-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Mechanism of glucose metabolism reprogramming of VECs in atherosclerosis. Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHC) reduces lactate production and prevents barrier dysfunction. Furthermore, the activation of

SL, LL: participated in the conceptualization, information collection and article writing; HC, JW: participated in the design of the Tables, article writing, review, editing; DY: participated in the conceptualization, later thought arrangement and language modification of the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Projects of Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department (grant number 2022SK2011), the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (grant number 2021RC4064), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant number 2022JJ40314) and the Scientific Research Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department (grant number 22B0387).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.