1 The School of Nursing, Fujian Medical University, 350005 Fuzhou, Fujian, China

2 Department of Nursing, Jingmen Peoples Hospital, 448001 Jingmen, Hubei, China

3 Department of Nursing, Women and Children’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, 361005 Xiamen, Fujian, China

4 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, 350001 Fuzhou, Fujian, China

5 Department of Nursing, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, 350001 Fuzhou, Fujian, China

Abstract

Prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV) is a common complication after cardiac surgery and is considered a risk factor for poor outcomes. However, the incidence and in-hospital mortality of PMV among cardiac surgery patients reported in studies vary widely, and risk factors are controversial.

We searched four databases (Web of Science, Cochrane Library, PubMed, and EMBASE) for English-language articles from inception to October 2023. The odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), PMV incidence, and in-hospital mortality were extracted. Statistical data analysis was performed using Stata software. We calculated the fixed or random effects model according to the heterogeneity. The quality of each study was appraised by two independent reviewers using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale.

Thirty-two studies were included. The incidence of PMV was 20%. Twenty-one risk factors were pooled, fifteen risk factors were found to be statistically significant (advanced age, being female, ejection fraction <50, body mass index (BMI), BMI >28 kg/m2, New York Heart Association Class ≥Ⅲ, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal failure, heart failure, arrhythmia, previous cardiac surgery, higher white blood cell count, creatinine, longer cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time, and CPB >120 min). In addition, PMV was associated with increased in-hospital mortality (OR, 14.13, 95% CI, 12.16–16.41, I2 = 90.3%, p < 0.01).

The PMV incidence was 20%, and it was associated with increased in-hospital mortality. Fifteen risk factors were identified. More studies are needed to prevent PMV more effectively according to these risk factors.

This systematic review and meta-analysis was recorded at PROSPERO (CRD42021273953, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=273953).

Keywords

- cardiac surgical patients

- in-hospital mortality

- meta-analysis

- prolonged mechanical ventilation

- risk factors

Based on the findings of the Global Burden of Disease study, there was a significant two-fold increase in cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevalence between 1990 and 2019, with the number of afflicted individuals escalating from 271 million to 523 million [1]. The progressive evolution of cardiac surgical technology has engendered a burgeoning cohort of patients eligible for surgical interventions. Despite the advancements in perioperative management, anesthesia, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), and the surgical environment remain vulnerable to postoperative functional changes, which give rise to consequential complications. Among these, the incidence of prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV) constitutes a substantial proportion, accounting for up to 53.27% [2]. PMV has been correlated with heightened reintubation and prolonged duration of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU), leading to more pulmonary complications [3].

Globally, the number of PMVs has increased. Within the United States, the demand for PMVs reached an estimated 625,000 cases in 2020, while in Taiwan, 92,324 patients required PMVs between 2015 and 2019 [4, 5, 6]. PMV not only results in negative patient experiences but also reduces their quality of life. The complications arising from PMV, encompassing muscle wasting, functional impairment, and diaphragmatic dysfunction, have been found to be associated with extended hospitalization periods and elevated mortality. Consequently, these complications impose considerable financial strain upon afflicted families [7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. The reported incidence of PMV in patients undergoing cardiac surgery ranges from 1.96% to 53.27% [2, 10, 12, 13, 14], and the risk factors for PMV include older age [12, 15], emergency surgery [10, 15, 16], and being female [9, 15]. However, these findings are controversial. The current evidence on PMV prevention and treatment in cardiac surgical patients has yet to be comprehensively synthesized, largely due to variations in PMV definitions and study designs across different investigations. In addition, the effect of PMV on in-hospital mortality remains controversial [8, 14]. Therefore, identifying PMV-related risk factors and prognoses may optimize clinical treatment and decision-making to assist surgeons in surgical planning and postoperative management.

Thus, through a systematic review and meta-analysis, the present synthesis endeavors to investigate the incidence, identify risk factors and analyze in-hospital mortality in patients experiencing PMV after cardiac surgical procedures. The overarching objective of this study is to furnish evidence that informs the prevention and effective management of PMV-associated complications in this specific patient population.

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary material 1) and recorded at PROSPERO.

Databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library, were independently searched by two researchers for studies published from the database inception through October 2023. The retrieval strategy combined cardiac surgery with PMV. Detailed search strategies are shown in Supplementary material 2.

Two researchers independently selected the articles. First, duplicate studies were removed by EndNote X20 (Thomson ResearchSoft, Philadelphia, PA, USA), and inappropriate studies were eliminated based on the title and abstract. After screening by title and abstract, we assessed the articles to select qualified literature through full-text screening. Disputes or disagreements were resolved through discussions with a third researcher.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: age: 18 years or older; undergoing

cardiac surgery; data should be available for extracting the incidence, risk

factors, or in-hospital mortality for PMV; risk factors for PMV must be assessed

by an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI); PMV was defined as a

ventilation time

The quality of the included studies was independently appraised and

cross-checked by two reviewers using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment

scale (NOS). The total score for NOS is 9. The risk of bias was classified into

three categories: low-quality, NOS

According to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, two investigators independently assessed the quality of the evidence for risk factors. Evidence grades were divided into the following categories: high, where authors were confident that the estimated effect was similar to the actual effect; moderate, where the estimated effect was probably close to the exact effect; low, where the true effect might be different from the estimated effect; very low, where the actual effect was probably markedly different from the estimated effect.

Two researchers independently extracted data from the included studies using a pre-designed data form. The following data were extracted: the characteristics of each study, risk factors, and in-hospital mortality.

We used Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) to perform

a meta-analysis. The incidences of PMV, in-hospital mortality, and PMV-related

risk factors were pooled. Subgroup analyses were performed according to PMV

definitions and study population. OR and 95% CI were calculated to assess the

strength of the associations, and Cochran’s Q and I2 tests

were used to evaluate heterogeneity. I2

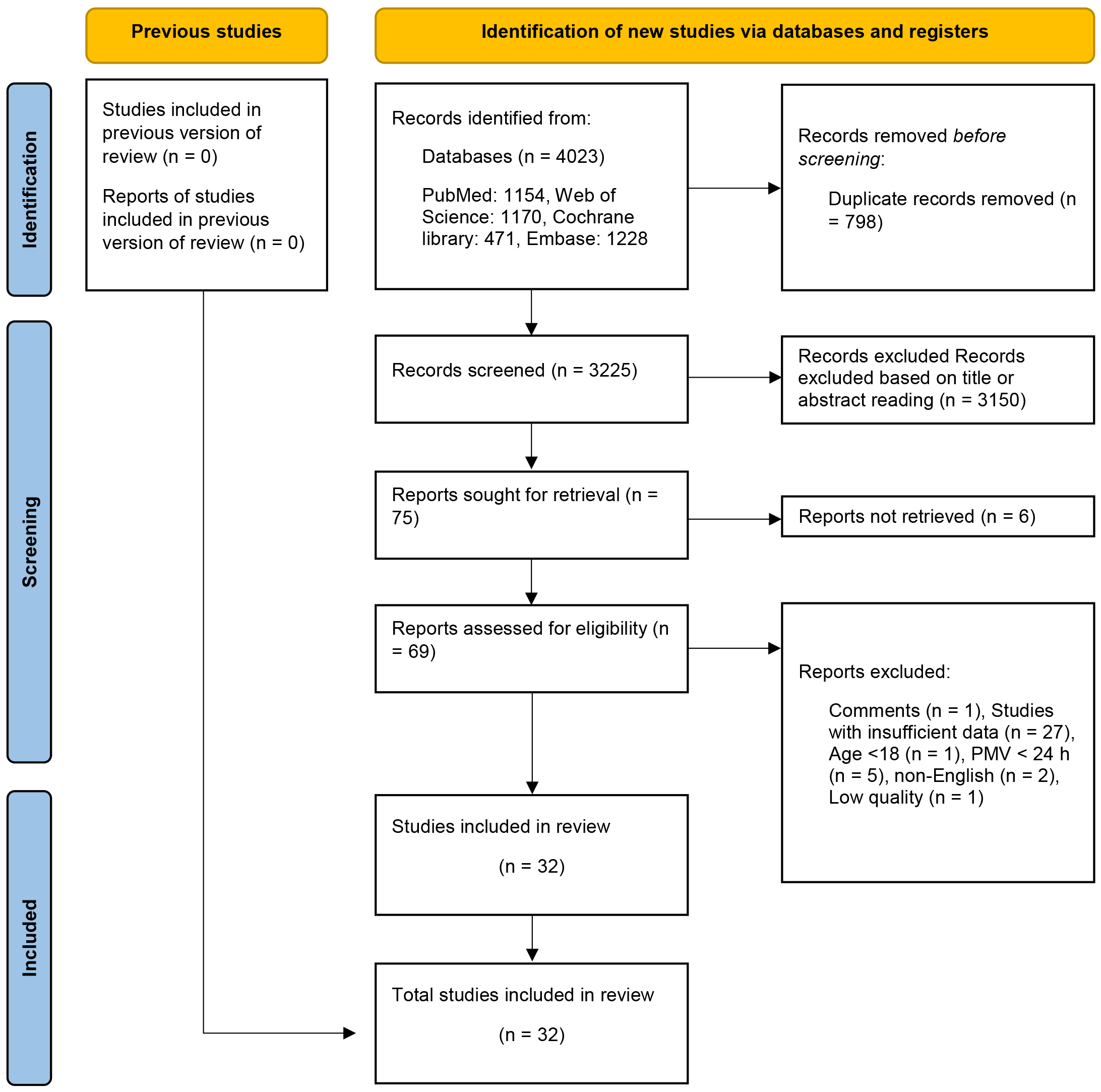

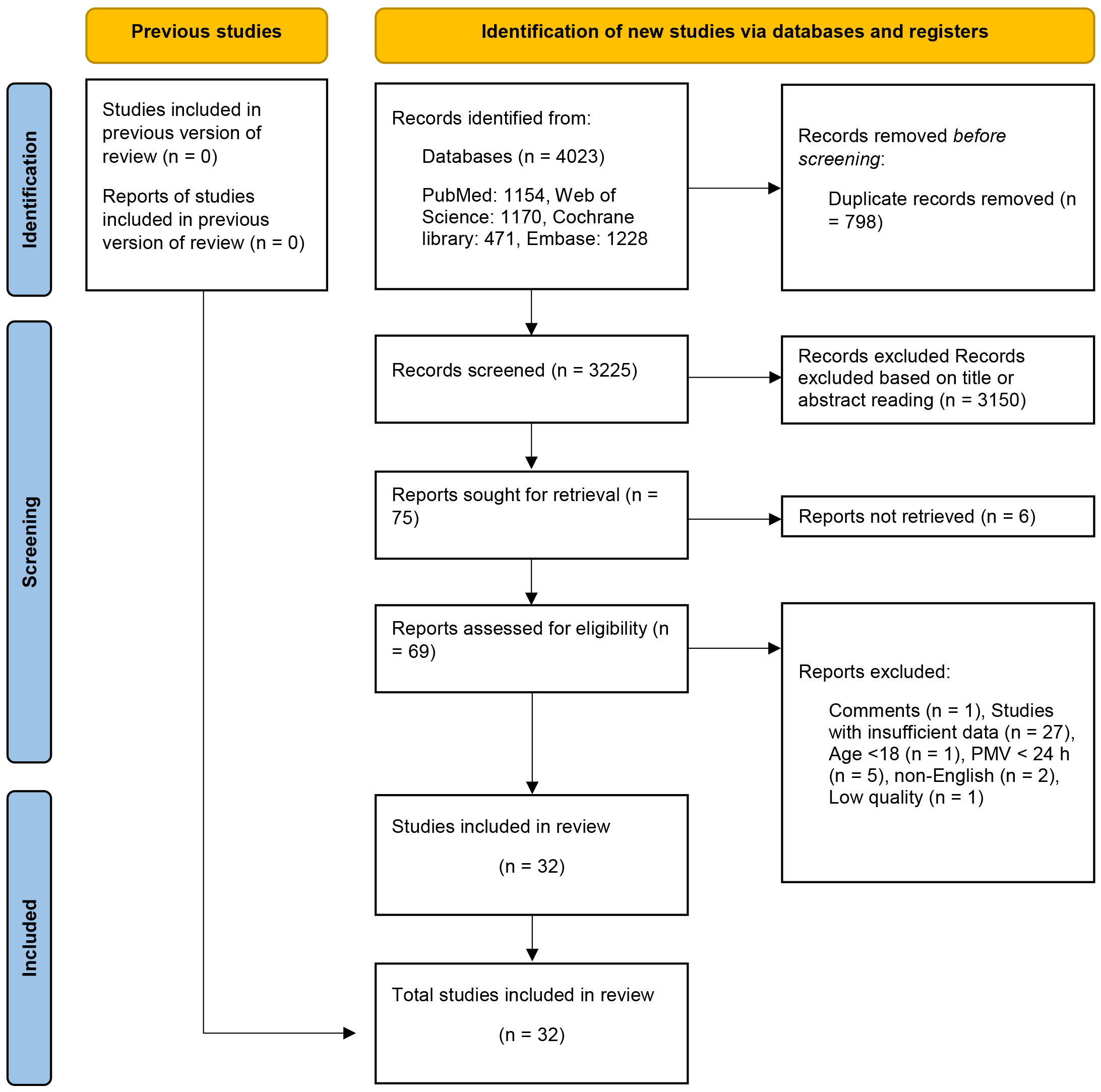

After eliminating duplicate entries, 3325 articles underwent preliminary

screening through title and abstract assessments. Following this, seventy-two

eligible articles were subjected to full-text screening. After conducting a

thorough full-text screening, forty-two articles were excluded from the analysis.

Among these, twenty-seven studies were excluded due to insufficient data: one was

a review, one had participants below the age of 18 years, five had a PMV

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of research strategy. PMV, prolonged mechanical ventilation.

| Author/year | Country | Study design | Age | Study population | Sample Size | PMV definition | PMV incidence | Mortality | ||

| PMV | Non-PMV | PMV | Non-PMV | |||||||

| Engle J et al. 1999 [17] | America | Retrospective case–control study | NA | NA | TAAA | 256 | 41.8% | NA | NA | |

| Kern H et al. 2001 [18] | Germany | Retrospective cohort study | Median: 66.2 | Median: 62.3 | CABG, valve | 687 | 9% | 11.3% | 0.48% | |

| Légaré JF et al. 2001 [19] | Canada | Retrospective cohort study | 65.40 |

CABG | 1829 | 8.6% | 18.5% | 1.2% | ||

| Yende S et al. 2004 [20] | America | Retrospective cohort study | NA | NA | CABG | 400 | 6.75% | NA | NA | |

| Natarajan K et al. 2006 [21] | India | Retrospective cohort study | 56.80 |

56.90 |

CABG | 470 | 4.7% | 36.3% | 0.45% | |

| Lei Q et al. 2009 [22] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 48.90 |

44.20 |

Aortic arch surgery | 255 | 10.2% | 11.5% | 0.9% | |

| Shirzad M et al. 2010 [23] | Iran | Retrospective cohort study | 53.93 |

48.25 |

Valve surgery | 1056 | 6.6% | 42.9% | 2.2% | |

| Christian K et al. 2011 [24] | America | Retrospective cohort study | 66.00 |

66.40 |

CABG | 464 | 25% | 12.9% | 2.9% | |

| Piotto RF et al. 2012 [16] | Brazil | Retrospective cohort study | 62.00 |

67.30 |

CABG | 3010 | 2.6% | 58.4% | 2.3% | |

| Siddiqui MMA et al. 2012 [25] | Pakistan | Retrospective cohort study | 39.50 |

30.29 |

CABG, valve | 1617 | 4.8% | 32.5% | 0.4% | |

| Saleh HZ et al. 2012 [12] | UK | Retrospective cohort study | 68.6 (63.2, 73.7) | 65.2 (58.5, 71.1) | CABG | 10,977 | 2.0% | 28.4% | 0.5% | |

| Bartz RR et al. 2015 [13] | UK | Retrospective cohort study | 65.20 |

62.60 |

CABG | 3881 | 33.2% | NA | NA | |

| Gumus F et al. 2015 [8] | Turkey | Retrospective cohort study | 65.60 |

60.40 |

CABG | 830 | 5.6% | 45.7% | 4% | |

| Sharma V et al. 2017 [15] | Canada | Retrospective cohort study | 65 (37, 80) | 67 (47, 81) | Valve surgery | 21,654 | 6.2% | NA | NA | |

| Wise ES et al. 2017 [26] | America | Retrospective cohort study | 64.35 |

62.95 |

CABG | 738 | 14.1% | NA | NA | |

| Chen Y et al. 2019 [9] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 58.30 |

50.94 |

AAAD | 102 | 29.4% | 20.7% | 5.6% | |

| Hsu H et al. 2019 [10] | Taiwan, China | Retrospective cohort study | 64.00 |

CABG | 382 | 11.3% | NA | NA | ||

| Papathanasiou M et al. 2019 [7] | Germany | Retrospective cohort study | 58.5 |

57.5 |

LVAD | 139 | 43.2% | 60.0% | 2.5% | |

| Aksoy R et al. 2021 [27] | Turkey | Retrospective cohort study | 60.80 |

59.20 |

CPB | 207 | 20.8% | 37.2% | 5.5% | |

| Ge M et al. 2021 [14] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 53.60 |

51.10 |

De Bakey type I aortic dissection | 582 | 44.5% | 18.1% | 7.4% | |

| Kreibich M et al. 2022 [28] | Germany | Retrospective cohort study | 68.4 (9.9) | Valve surgery | 2597 | 16.3% | NA | NA | ||

| Lin L et al. 2022 [2] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 52.5 |

AAAD | 734 | 53.3% | NA | NA | ||

| Li X et al. 2022 [29] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 58 (50, 65) | 54 (46, 62) | Cardiac surgery | 3919 | 13.6% | 3.8% | 0.5% | |

| Michaud L et al. 2022 [30] | France | Retrospective cohort study | 67.3 |

67.4 |

CPB | 568 | 12.0% | 47.1% | 4.6% | |

| Meng Y et al. 2023 [31] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 61.44 |

59.33 |

Cardiac surgery | 693 | 21.2% | NA | NA | |

| Sankar A et al. 2022 [32] | Canada | Retrospective cohort study | 71 (11) | 73 (10) | CPB | 4809 | 15.0% | 14.0% | 1.0% | |

| Xie Q et al. 2022 [33] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 49.86 |

44.87 |

AAAD | 384 | 55.5% | NA | NA | |

| 51.40 |

45.58 |

35.4% | ||||||||

| 51.72 |

46.28 |

25.0% | ||||||||

| Xiao Y et al. 2022 [34] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 54.5 (39.0, 63.0) | 64 (56.0, 69.5) | Redo valve surgery | 117 | 38.5% | 13.3% | 0% | |

| Zhang Q et al. 2023 [35] | China | Retrospective cohort study | NA | NA | Cardiac surgery | 3835 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Shen X et al. 2022 [36] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 66 (55, 72) | 66 (54, 71) | CPB | 118 | 45.8% | NA | NA | |

| Rahimi S et al. 2023 [37] | Iran | Retrospective cohort study | NA | NA | CABG | 1361 | 21.4% | NA | NA | |

| Zhou Y et al. 2023 [38] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 65 (57, 75) | 52 (47, 62) | Valve surgery | 105 | 40% | 7.1% | 0% | |

NA, not applicable; TAAA, Stanford type A aortic dissection; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; UK, United Kingdom; AAAD, acute type A aortic dissection; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; PMV, prolonged mechanical ventilation; h, hours; d, days.

Based on NOS, three studies scored 8, fifteen scored 7, and eleven scored 6. These assessments revealed that 62% of the included studies satisfied the standards for high quality (Supplementary material 3).

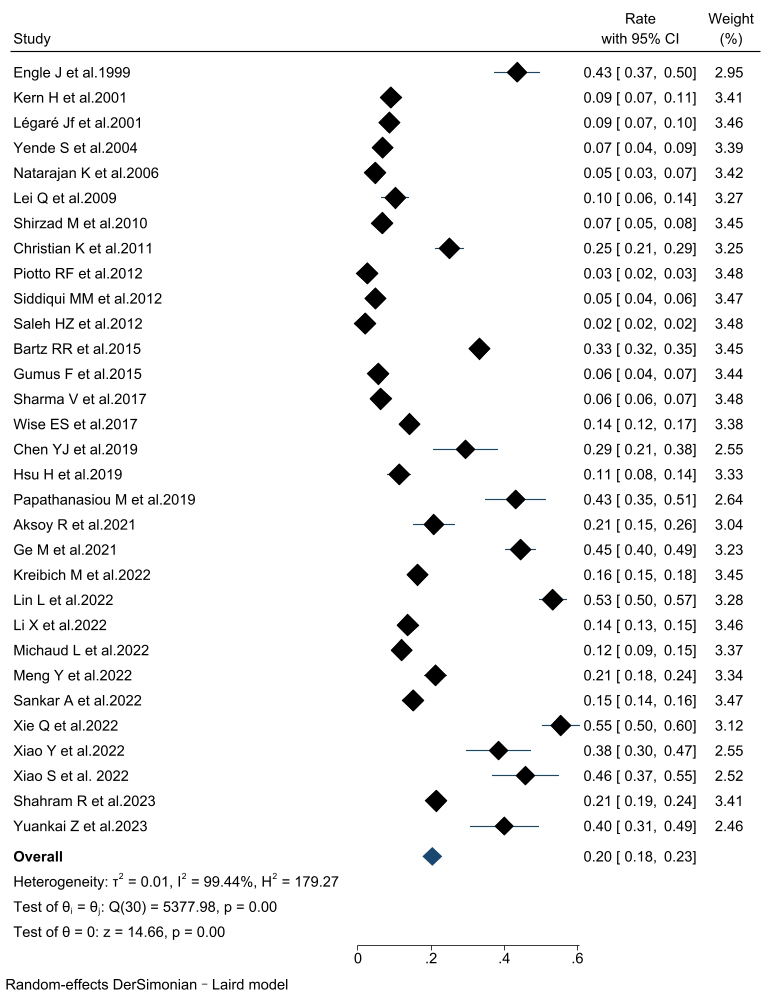

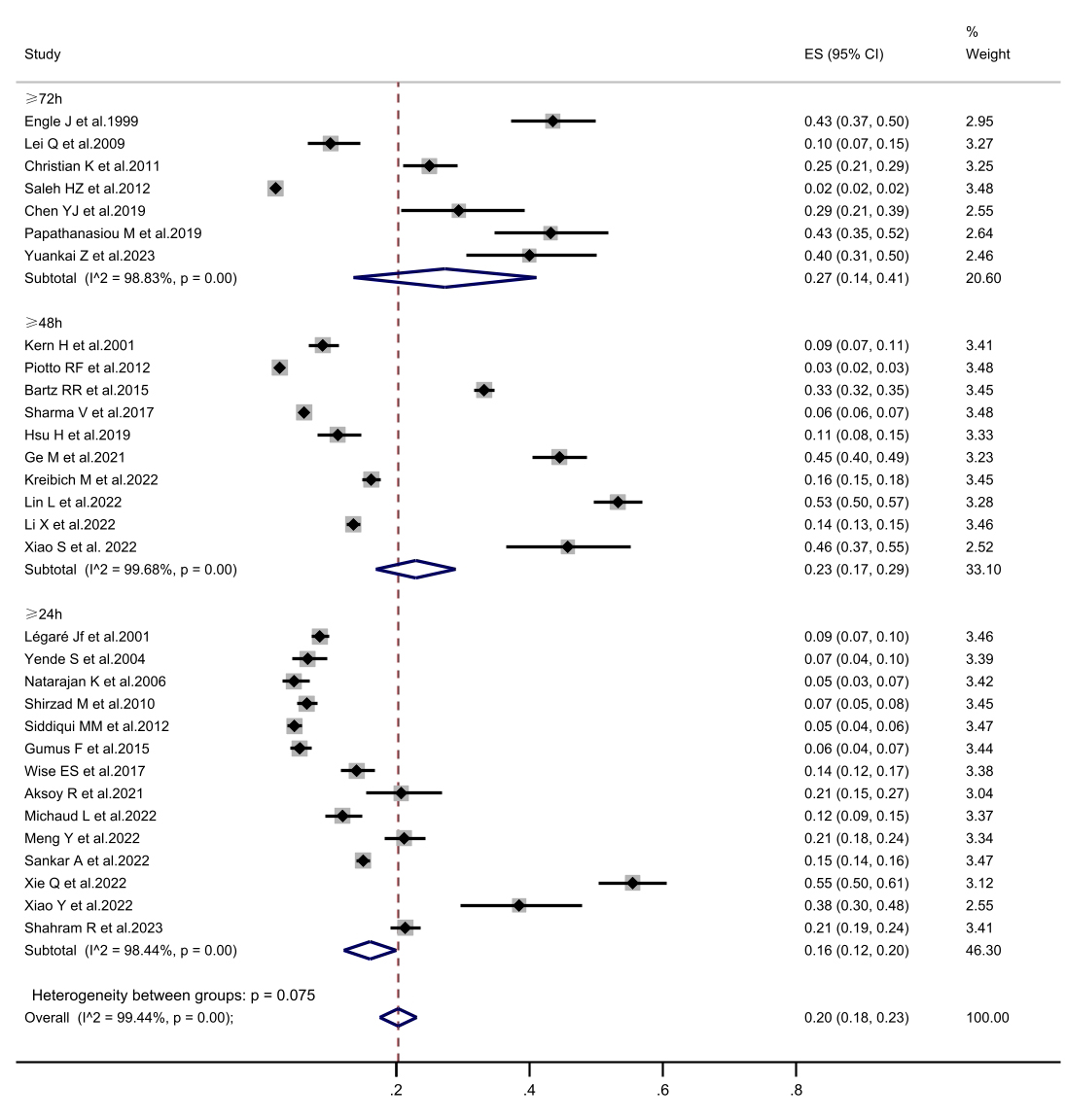

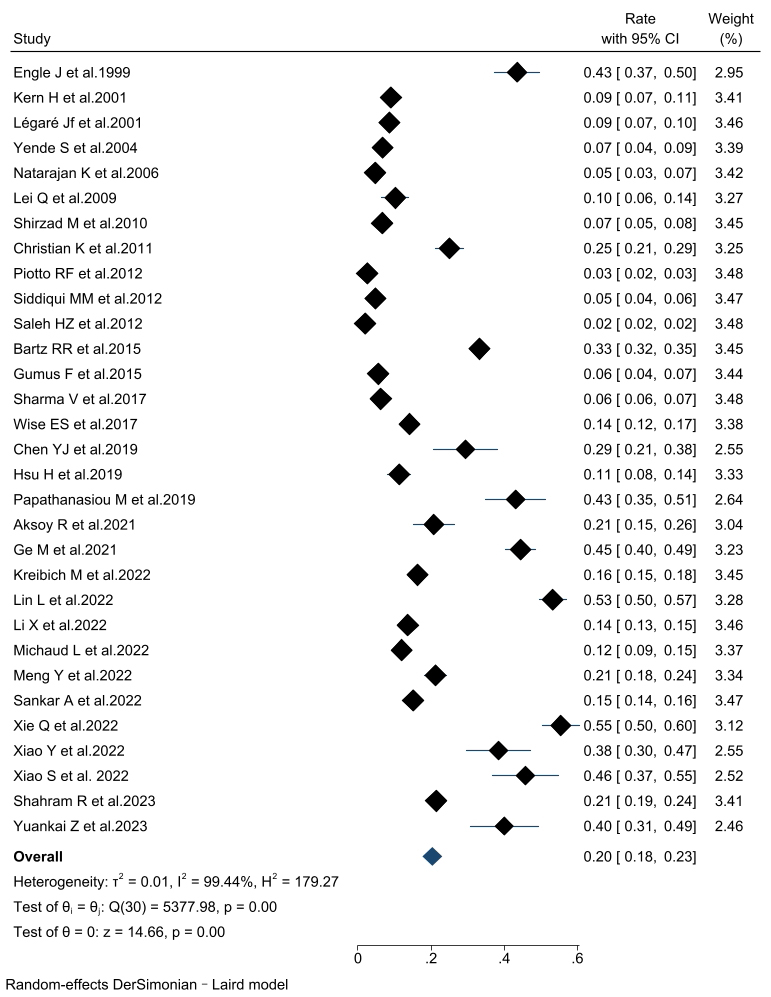

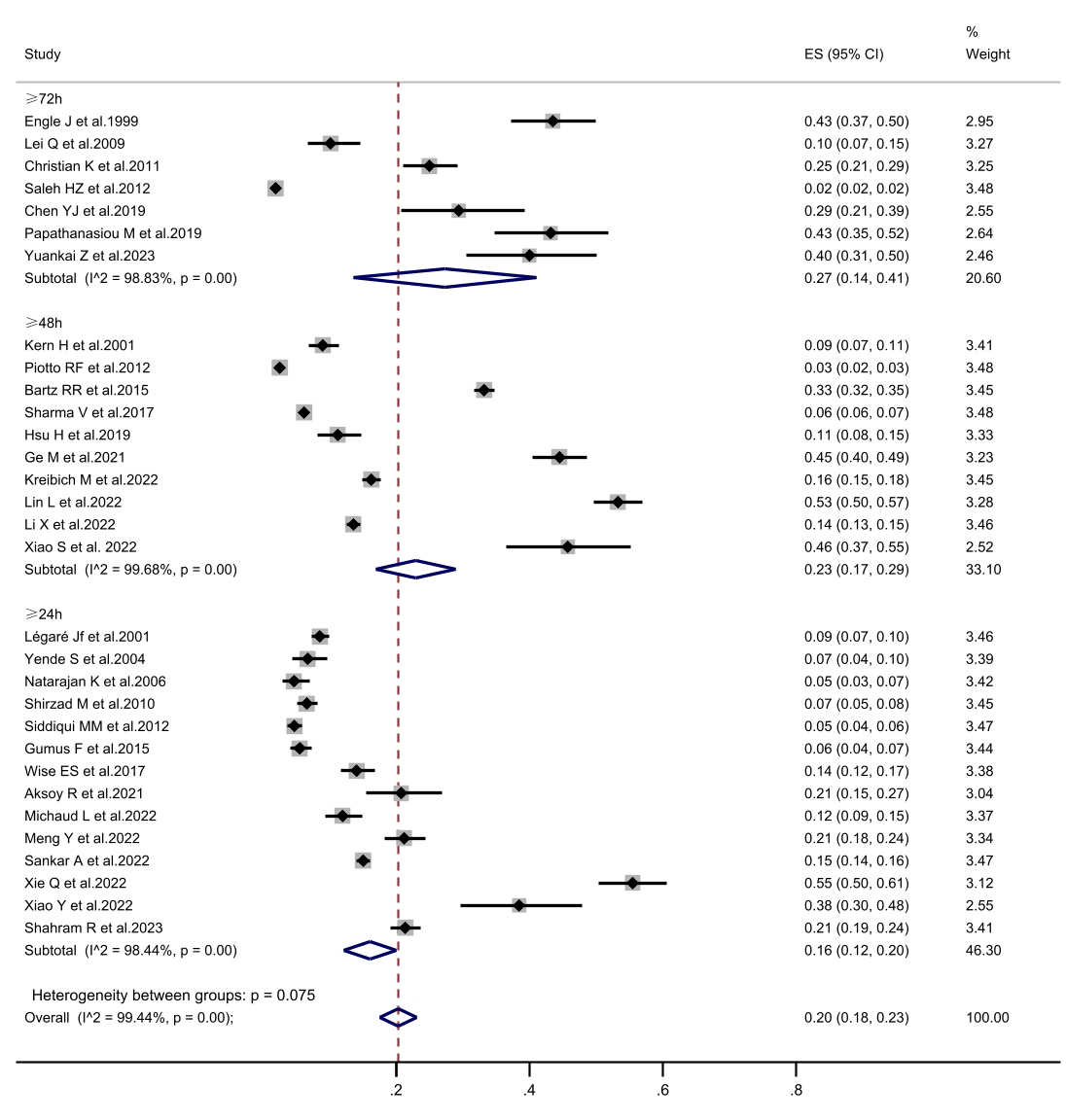

The incidence of PMV in patients undergoing cardiac surgery was 20% (95% CI,

18%–23%) across the thirty-two included articles. Subgroup analyses were

performed according to the PMV definition and the study population (Fig. 2).

Consistent findings were observed throughout all subgroup analyses. The combined

incidence of PMV was 16.1% (95% CI, 12.1%–20.1%) in the PMV

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The forest plot of prolonged mechanical ventilation incidence. CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The forest plot of subgroup analysis in prolonged mechanical ventilation incidence is defined according to prolonged mechanical ventilation. CI, confidence interval; ES, Eric Stephen Wise.

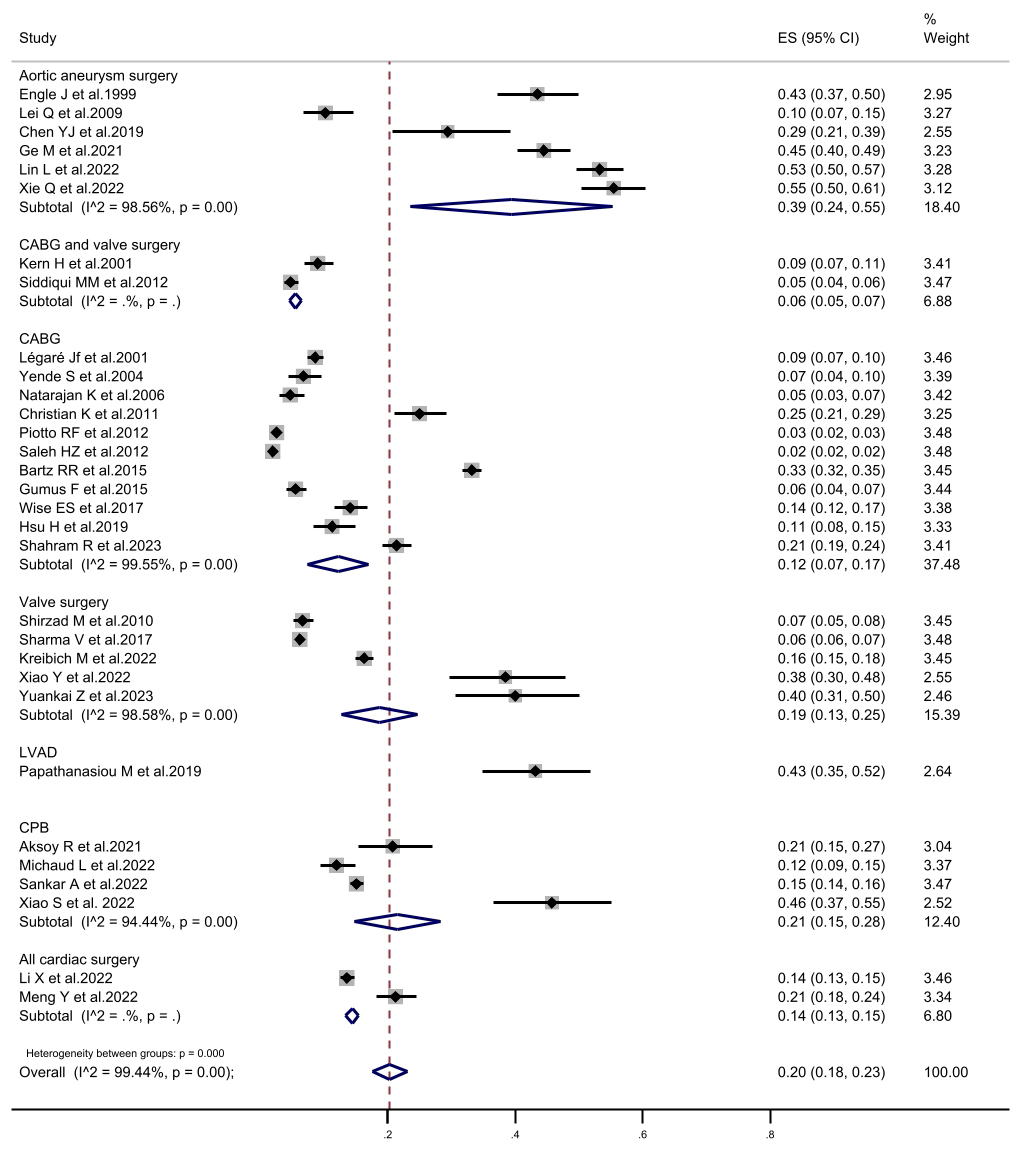

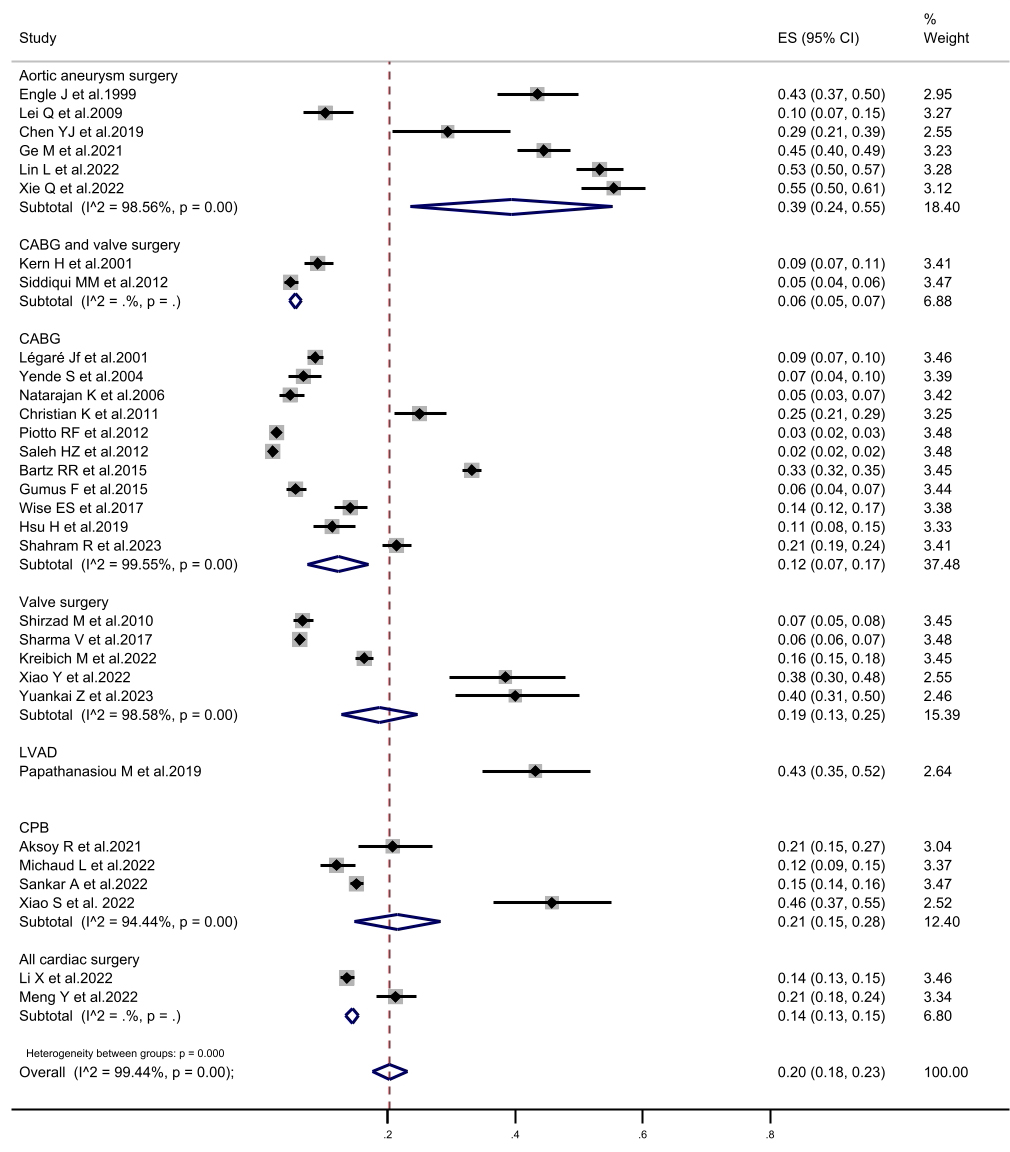

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The forest plot of subgroup analysis in prolonged mechanical ventilation incidence according to the study population. CI, confidence interval; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; ES, Eric Stephen Wise.

Eighteen preoperative risk factors were synthesized, with advanced age (OR,

1.03, 95% CI, 1.02–1.04, I2 = 53.9%, p

| Name | Number of articles included | OR | 95% CI | I2 (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced aged | 12 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | 53.9 | |

| Being female | 7 | 1.68 | 1.18–2.39 | 83.3 | |

| Ejection fraction |

6 | 2.32 | 1.72–3.13 | 66.6 | |

| Body mass index | 4 | 1.07 | 1.01–1.14 | 79.9 | 0.03 |

| Body mass index |

3 | 2.24 | 1.74–2.87 | 14.5 | |

| NYHA |

5 | 2.01 | 1.41–2.87 | 77.8 | |

| COPD | 6 | 1.61 | 1.37–1.90 | 16.3 | |

| Chronic renal failure | 8 | 2.47 | 1.92–3.19 | 13.0 | |

| Heart failure | 2 | 3.14 | 0.79–12.55 | 89.3 | 0.01 |

| Arrhythmia | 3 | 1.87 | 1.07–3.29 | 87.2 | |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 8 | 1.98 | 1.75–2.23 | 30.6 | |

| White blood cell count | 4 | 1.11 | 1.06–1.17 | 0 | |

| Creatinine | 4 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 27.1 | |

| Hypertension | 5 | 1.11 | 0.90–1.36 | 68.4 | 0.23 |

| Diabetes | 7 | 1.31 | 1.00–1.72 | 76.9 | 0.09 |

| Three or more vessel disease | 3 | 2.04 | 0.98–4.22 | 96.2 | 0.06 |

| Emergency surgery | 6 | 1.78 | 0.41–7.68 | 94.4 | 0.44 |

| Perioperative stroke | 3 | 1.15 | 0.81–1.62 | 67.2 | 0.15 |

| Longer CPB time | 8 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 86.3 | 0.02 |

| CPB time |

2 | 3.16 | 1.25–7.95 | 61.9 | |

| Cross-clamp time | 5 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.02 | 81.1 | 0.50 |

| Study population | |||||

| Name | Study population | Number of articles included | OR | 95% CI | I2 (%) |

| Advanced aged | Aortic aneurysm surgery | 4 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | 0 |

| CABG | 4 | 1.04 | 1.02–1.06 | 68.7 | |

| Valve surgery | 3 | 1.57 | 0.99–1.11 | 70.4 | |

| All cardiac surgeries | 1 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | - | |

| Ejection fraction |

CABG | 3 | 2.93 | 1.16–7.39 | 80.9 |

| Others | 3 | 2.23 | 1.70–2.92 | 54.6 | |

| Body mass index | CABG | 2 | 1.04 | 0.93–1.16 | 90.2 |

| Aortic aneurysm surgery | 2 | 1.10 | 1.06–1.15 | 0 | |

| Hypertension | Aortic aneurysm surgery | 1 | 0.81 | 0.38–1.07 | - |

| CABG | 1 | 1.48 | 1.08–2.02 | - | |

| Valve surgery | 2 | 0.97 | 0.64–1.47 | 87.4 | |

| CPB | 1 | 1.22 | 0.99–1.50 | - | |

| Diabetes | CABG | 3 | 1.68 | 1.12–2.53 | 78.1 |

| Non-CABG | 3 | 1.01 | 0.72–1.41 | 64.4 | |

| COPD | CABG | 4 | 1.83 | 1.36–2.47 | 0 |

| Aortic aneurysm surgery | 2 | 1.52 | 1.25–1.85 | 53.0 | |

| Chronic renal failure | CABG | 6 | 2.68 | 1.88–3.82 | 23.4 |

| CABG and valve surgery | 1 | 2.43 | 1.32–4.49 | - | |

| LVAD | 1 | 1.15 | 0.34–4.05 | - | |

| Longer CPB | Aortic aneurysm surgery | 3 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0 |

| Others | 2 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 46.2 | |

| PMV definition | |||||

| Name | Number of articles included | OR | 95% CI | I2 (%) | |

| Advanced aged | PMV |

3 | 1.03 | 0.98–1.08 | 76.4 |

| PMV |

6 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | 59.6 | |

| PMV |

3 | 1.04 | 1.02–1.05 | 0 | |

| Ejection fraction |

PMV |

3 | 2.83 | 1.49–5.36 | 79.5 |

| PMV |

3 | 2.20 | 1.51–3.19 | 60.0 | |

| Being female | PMV |

2 | 1.80 | 1.30–2.51 | 0 |

| PMV |

3 | 1.10 | 0.87–1.47 | 73.8 | |

| PMV |

2 | 4.14 | 2.39–7.20 | 0 | |

| Hypertension | PMV |

1 | 1.48 | 1.08–2.02 | - |

| PMV |

3 | 0.94 | 0.66–1.34 | 76.6 | |

| PMV |

1 | 1.48 | 1.08–2.02 | - | |

| Diabetes | PMV |

2 | 1.41 | 0.83–2.42 | 58.7 |

| PMV |

3 | 1.41 | 0.94–2.10 | 86.6 | |

| PMV |

2 | 0.83 | 0.19–3.61 | 85.7 | |

| COPD | PMV |

2 | 1.70 | 1.17–2.48 | 15.8 |

| PMV |

4 | 1.59 | 1.32–1.91 | 36.0 | |

| Chronic renal failure | PMV |

5 | 2.22 | 1.65–2.99 | 0 |

| PMV |

3 | 3.13 | 1.49–6.58 | 47.5 | |

| Emergency surgery | PMV |

3 | 2.05 | 0.15–27.37 | 88.0 |

| PMV |

3 | 1.51 | 0.26–8.71 | 95.3 | |

| Previous cardiac surgery | PMV |

2 | 2.17 | 1.12–4.17 | 35.9 |

| PMV |

5 | 1.91 | 1.60–2.28 | 30.1 | |

| PMV |

1 | 5.08 | 1.67–15.43 | - | |

| Longer CPB | PMV |

3 | 2.58 | 0.78–8.50 | 89.1 |

| PMV |

4 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0 | |

| PMV |

2 | 1.15 | 0.96–1.37 | 92.9 | |

| Name | Number of articles included | OR | 95% CI | I2 (%) | ||

| Overall mortality | 17 | 14.13 | 12.16–16.41 | 90.3 | ||

| Subgroup analysis | Study population | CABG | 4 | 26.51 | 20.58–34.14 | 94.2 |

| Valve surgery | 3 | 18.90 | 11.69–30.55 | 0 | ||

| CABG and valve surgery | 2 | 34.67 | 16.84–71.40 | 92.6 | ||

| Aortic aneurysm surgery | 3 | 2.95 | 1.95–4.47 | 52.4 | ||

| Cardiopulmonary bypass surgery | 3 | 11.94 | 9.11–15.65 | 51.4 | ||

| Others | 2 | 8.69 | 4.90–15.42 | 59.0 | ||

| PMV definition | PMV |

8 | 14.88 | 12.15–18.23 | 76.1 | |

| PMV |

3 | 3.60 | 2.51–5.15 | 72.0 | ||

| PMV |

6 | 30.02 | 22.59–39.90 | 89.2 | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NYHA, New York Heart Association (classification); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PMV, prolonged mechanical ventilation; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

Three intraoperative risk factors were identified and summarized. Our analysis

revealed that longer CPB time and CPB time

Subgroup analyses were performed for each risk factor according to the PMV

definition and study population. The pooled effect and heterogeneity remained

largely unchanged across various subgroups, including advanced age, being female,

EF

A sensitivity analysis was performed for several risk factors, including

advanced age, being female, EF

Seventeen out of the thirty-two studies reported data on in-hospital mortality

in both the PMV and non-PMV groups, with our analysis revealing a significant

association between PMV and in-hospital mortality (OR, 14.13, 95% CI,

12.16–16.41, I2 = 90.3%, p

The findings indicate that advanced age, being female, COPD, chronic renal

failure, and higher WBC exhibited a high level of supporting evidence classified

as high-quality; EF

This systematic review and meta-analysis represent the inaugural endeavor to

comprehensively examine the incidence, risk factors, and in-hospital mortality

concerning PMV in cardiac surgery patients. The synthesis included 32 studies

involving a total of 68,766 patients and yielded the subsequent key findings: PMV

incidence was 20%; 15 risk factors were associated with PMV (advanced age, being

female, EF

PMV is a well-recognized complication of cardiac surgery, with an incidence

ranging from 1.96% to 53.27% [12, 14]. The observed variation in reported

incidences of PMV may be attributed to the lack of standardized definitions

across studies. To address this issue and enhance the homogeneity of the study

population, we employed a uniform definition of PMV as a duration equal to or

exceeding 24 hours. By implementing this consistent criterion, we aimed to

mitigate potential discrepancies in the identification and classification of PMV

cases, ensuring a more reliable and comparable analysis of relevant outcomes. CVD

patients are typically extubated within 6 h of surgery; 24 h is sufficient to

stabilize their hemodynamics and eliminate the negative effects of surgery and

CPB [25, 39]. Concurrently, PMV

The pooled incidence of PMV among patients who underwent cardiac surgery was

determined to be 20%. Subgroup analysis, according to the study population,

revealed that the highest incidence of PMV was 39.4% in aortic surgical patients

(patients with aortic dissection and aortic arch disease). Conversely, the lowest

incidence of PMV was observed in patients undergoing CABG combined with valve

surgery, with a rate of 5.6%. In the subgroup analysis of PMV definitions, when

PMV was defined as a duration of 72 hours or longer, the incidence was higher at

27.3%, compared to definitions of 24 h (16.1%) and 48 h (23.0%). Notably, the

PMV

Evaluating the risk factors associated with PMV in patients undergoing cardiac

surgery is essential for improving patient prognosis. In our synthesis, we

identified advanced age, being female, and BMI as demographic characteristics

that exhibited a significant association with PMV and served as risk factors.

Patients who developed PMV in the included articles were predominantly over 60

years of age. Advanced age would reduce functional reserves and increase

comorbidities, which have been associated with PMV. The assessment of other

surgical patients provided the same conclusion [45, 46]. Although the

relationship between PMV and women continues to receive widespread attention, the

findings remain controversial. Epidemiological studies have consistently provided evidence

supporting the protective role of estrogen against CVD in women. Notably, before

menopause, the incidence of coronary heart disease is lower in women compared to

men. This observation is attributed, at least in part, to the beneficial effects

of estrogen on various cardiovascular parameters, including lipid metabolism,

vascular function, and inflammation [47]. Therefore, we speculated that there may

have been a selection bias. In addition, being female has been identified as a

possible risk factor for intensive care unit-acquired weakness, which causes

diaphragmatic weakness and prolongs the duration of mechanical ventilation [48, 49]. Whether a higher BMI is associated with PMV has been debated. Our results

suggest a higher BMI and BMI

The influence of heart conditions cannot be ignored. Ejection fraction

In addition, we confirmed that the patient’s medical history and information on other diseases are crucial for preventing PMV. COPD, chronic renal failure, previous cardiac surgery, higher WBC, and creatinine were proved. Comorbidities such as renal injury and pulmonary hypertension are worthy of attention as they increase the risk of severe cardiac dysfunction and limit physiologic reserve [52, 53]. Cardiac patients, such as those with renal impairment, often have other comorbidities (e.g., diabetes and hypertension) that increase their mental, physiological, and economic burden. The same conclusion has been reported in previous studies [54, 55]. While our analysis suggested that hypertension and diabetes mellitus do not significantly elevate the risk of PMV, it is crucial to acknowledge that the evidence supporting this conclusion was of low quality. Consequently, further research with higher-quality evidence is warranted to establish the relationship between these comorbidities and PMV risk definitively.

Regarding intraoperative risk factors for PMV, longer CPB times and CPB

Finally, we examined the relationship between PMV and in-hospital mortality. We found cardiac surgical patients with PMV had a 14-fold increase in in-hospital mortality compared with that in patients without PMV. Subgroup analyses based on different study populations and PMV definitions revealed that in-hospital mortality significantly increased among PMV patients. Moreover, the relationship between long-term mortality and PMV should be addressed. A large analysis of critically ill patients receiving at least 48 hours of mechanical ventilation showed a 28-day mortality rate of 26.3% [58]. Due to limited evidence, we only analyzed in-hospital mortality. Future studies should explore the effects of PMV on long-term mortality.

We conducted a comprehensive search and rigorous screening of studies for inclusion. NOS was also used to assess the quality. Since the included studies had similar but different clinical settings, we performed subgroup analyses of different study populations and PMV definitions. Given the presence of identical yet distinct clinical settings among the included studies, we conducted subgroup analyses to examine the effects of diverse study populations and variations in PMV definitions. However, our synthesis had some limitations. Firstly, our analysis included only English-language publications, which might have partly caused us to miss relevant non-English publications. Secondly, the number of studies included in each analysis was relatively small. Finally, an exhaustive analysis of other PMV risk factors, such as smoking history and operative time, was not feasible due to their absence or limited coverage in the original studies. Future large-scale clinical trials are required to validate the relationship between those unidentified risk factors and the PMV. In addition, further research should be conducted to determine the weights of these identified risk factors to make them more clinically feasible.

The incidence of PMV was 20%. Fifteen risk factors were associated with a heightened risk of PMV. However, the potential impacts of higher BMI, heart failure, and arrhythmias require further exploration. Our synthesis also revealed that PMV was significantly associated with increased in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Moreover, we support the definition of PMV as a duration greater than or equal to 24 hours, as it would enable earlier identification of cases with PMV. The findings of our synthesis suggest that the timely identification of risk factors for PMV and prompt recognition and intervention are vital for enhancing patient prognosis. Therefore, future PMV management should better emphasize these identified risk factors.

All data points generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and there are no further underlying data necessary to reproduce the results.

QW, YT, XZ—designed the study, wrote manuscript; SX, YP, LL—conducted literature search, appraisal of study quality, reviewed and revised the manuscript; LC, YL—revised the manuscript, examined study design and findings. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by grant from Fujian provincial health technology project (2021CXA017).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.rcm2511409.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.