1 Department of Echocardiography and Cardiology, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, 213000 Changzhou, Jiangsu, China

2 Department of Cardiology, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, 213000 Changzhou, Jiangsu, China

Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common persistent arrhythmia, with increasing incidence worldwide. Transcatheter radiofrequency ablation (RFA) represents a first-line therapy for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF), although the long-term recurrence rate of AF remains relatively high. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between the average heart rate (AHR) on a dynamic electrocardiogram before transcatheter RFA and the postoperative recurrence of AF in patients with PAF.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients with PAF who experienced primary transcatheter RFA. Relevant clinical indicators, dynamic electrocardiograms, and echocardiography were collected from the enrolled patients before ablation. Multivariate logistic regression analysis examined the relationship between the preoperative AHR and postoperative recurrence of AF in patients with PAF.

This study included 224 patients with PAF who were scheduled for transcatheter RFA. Based on the AHR in sinus rhythm state on the dynamic electrocardiogram before ablation, the patients were divided into three groups: low, medium, and high heart rate. The recurrence rates of AF after ablation for the three groups were 14.667%, 8.108%, and 4.000%, respectively. After adjusting for confounding factors, postoperative AF recurrence risk gradually decreased with an increase in preoperative AHR (odds ratio: 0.849, 95% confidence interval: 0.729–0.988, p = 0.035). This trend remained statistically significant even after adjusting for the three categorical variables of AHR (odds ratio = 0.025, 95% confidence interval: 0.001–0.742, p = 0.033). The curve fitting analysis indicated a linear and negative correlation between the preoperative AHR and postoperative AF recurrence risk in patients with PAF.

In patients with PAF who experienced their primary transcatheter RFA, there was a linear and negative correlation between the AHR in sinus rhythm state on the preoperative dynamic electrocardiogram and the risk of postoperative AF recurrence.

Keywords

- paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

- transcatheter radiofrequency ablation

- postoperative recurrence

- average heart rate

- echocardiography

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a prevalent tachyarrhythmia in clinical practice,

with rapidly increasing incidence and prevalence rates [1]. AF is associated with

elevated risks of thromboembolism, heart failure, and other cardiovascular

events, leading to higher mortality and disability rates [2]. AF treatment

strategies include rhythm and heart rate control therapy, which are crucial

components in comprehensive treatment approaches [3]. Some scholars stated there

was a probability of spontaneous conversion to sinus rhythm in AF patients, so a

score was developed and validated to determine the probability in patients with

hemodynamically stable, symptomatic, and recent-onset AF [4]. However, a few

patients with AF can convert to sinus rhythm spontaneously and have a high

possibility of recurring and maintaining AF rhythm, meaning transcatheter

radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has emerged as a significant treatment option for

controlling rhythm, alleviating symptoms and enhancing the quality of life in

patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF) (Ia) [5]. However, literature

reports show a recurrence rate of approximately 11%–30% within 1–5 years

after RFA [6, 7, 8, 9]. Thus, to optimize AF treatment strategies, predicting AF

recurrence after RFA is essential. Common risk factors for AF recurrence after

RFA include left atrial enlargement, prolonged AF duration, and impaired left

atrium storage function. Researchers have developed several predictive models to

improve the accuracy of predicting AF recurrence after RFA. For instance,

Mesquita et al. [10] constructed and validated the ATLAS score to

estimate the recurrence rate of AF after RFA, and Kornej et al. [11]

developed the APPLE score to identify patients with low, medium, and high risks

of AF recurrence, Winkle et al. [12] created the CAAP-AF scoring

system to estimate AF recurrence within 2 years after RFA and Mujović

et al. [13] established the MB-LATER clinical score to predict very late

recurrence of AF occurring

Dynamic electrocardiography is a commonly used method for detecting arrhythmias in medical practice. This technology offers several advantages: simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and non-invasiveness. Furthermore, the average ventricular rate obtained from a dynamic electrocardiogram can more accurately reflect a patient’s cardiac activity. Research has demonstrated the significance of the average ventricular rate in guiding optimal heart rate control treatment and adjusting drug dosage in patients with AF when obtained from a 24-hour dynamic electrocardiogram; moreover, it can provide comprehensive information on AF burden and the onset of AF [20]. Another study [21] has suggested that a 24-hour dynamic electrocardiogram can serve not only in diagnosing AF but also in independently correlating ST segment depression with the occurrence of AF, thereby identifying patients with AF who are either at high or low risk.

A prospective cohort study conducted in Norway based on the general population

with a follow-up period averaging 20 years has reported that individuals with a

higher resting heart rate (

This study retrospectively examined the 24-hour dynamic electrocardiogram of patients with PAF before undergoing RFA and analyzed the correlation between the AHR in the sinus rhythm state and postoperative recurrence of AF. The objective was to provide guidance for adjusting preoperative antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) usage while also enabling early identification and targeted intervention for patients at high risk of postoperative recurrence.

A single-center, retrospective cohort method was used in this research. Patients

with PAF admitted to Changzhou First People’s Hospital between January 2017 and

December 2020 and scheduled to undergo RFA for the first time were included in

this study. PAF was defined as AF with a duration of 7 days or less, mostly

lasting less than 24 hours, and capable of self-termination. Inclusion criteria

were as follows: (1) no significant history of organic heart disease; (2) aged

between 18 and 75 years; (3) absence of cardiac insufficiency in preoperative

echocardiography (left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)

We collected various clinical baseline indicators from the patients, including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), duration of AF, blood urea nitrogen level, blood cholesterol level, atrial fibrillation thrombus risk score (CHA2DS2-VASc score), medical history (including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, stroke or transient ischemic attack and peripheral vascular disease), lifestyle factors (such as smoking and alcohol consumption) and the usage of AAD.

Before RFA, patients underwent dynamic electrocardiogram examination within 48

hours. The BI900 series dynamic electrocardiogram monitoring system (Shenzhen Boying Biomedical

Instrument Technology Co., Ltd. Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) was used for dynamic

electrocardiogram recording. The instrument consisted of a smaller recorder,

electrodes, and a playback system. Patients were initially positioned supine,

with right arm (RA) electrodes placed at the right subclavian fossa, left arm (LA) electrodes placed at

the left subclavian fossa, left leg (LL) electrodes placed at the junction of the left

clavicular midline, and rib arch, right leg (RL) electrodes placed at the waist or sloping

shoulder at the junction of the right clavicular midline and rib arch, and V1–V6

electrodes horizontally attached to the anterior chest rib. Once the electrodes

were attached, they were connected to the small recorder and secured with a

strap. Patients were instructed to avoid strenuous activity and overexertion.

After 24 hours, the dynamic electrocardiogram image recording was completed and

fully imported for archiving. All collected electrocardiogram data were

cross-analyzed by two experienced intermediate or higher-ranked

electrocardiologists, and a senior electrocardiologist reviewed the analysis

results. All electrocardiologists who analyzed the dynamic electrocardiogram (ECG) recordings were

blinded to the procedure outcomes. The 24-hour dynamic ECG data analysis included

the assessment of AHR in sinus rhythm state, total time of AF, total episodes of

AF (with each episode lasting

Prior to RFA, all patients underwent transthoracic echocardiography using the Philips EPIQ 7c color Doppler ultrasound diagnostic instrument(Philips Healthcare Royal Philips Electronics, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Patients were positioned left-lying and connected to a 12-lead electrocardiogram. The probe utilized a center frequency of 1–5 MHz and a frame rate of 50 Hz. Standard M-type, two-dimensional, and Doppler images of the sternum and apex were obtained. Two experienced physicians collected data during sinus rhythm, capturing five cardiac cycles, according to the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography [26], the left atrial diameter (LAD), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD), and LVEF, which was measured by the biplane Simpson method.

The ablation catheter and stimulation catheter were inserted into the right atrium through the femoral vein and then into the left atrium by transseptal puncture. Then, the CARTO system (Biosense Webster, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) performed three-dimensional mapping and merged with optimal three-dimensional reconstruction by computer tomography. A Thermocool SmartTouch ST or STSF (Biosense Webster, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) was employed to deliver the radio frequency signals at a target temperature of 45 °C and a power of 40 W. The resulting local myocardial injury had a depth and range of approximately 3–4 mm. Additionally, the radiofrequency ablation path was targeted as wide antral circumferential pulmonary vein isolation (the pulmonary vein ostium). This resulted in a reduction in local myocardial voltage to less than 0.15 mV and the elimination of pulmonary vein potential.

Commonly employed medications for managing ventricular rate in selected patients

before ablation primarily consisted of

All patients were followed up with a daily electrocardiogram for three days following the ablation procedure. They were also prescribed oral anticoagulants for a minimum of two months and continued taking their previous AAD for three months. After discharge, patients were monitored with monthly electrocardiograms, and at least one 24-hour dynamic electrocardiogram examination was conducted monthly.

R (https://www.R-project.org) and EmpowerStats software

(https://www.empowerstats.com, X&Y Solutions,

Inc, Boston, MA, USA) were used for the statistical analysis. Measurement data that

followed a normal distribution are expressed as the mean

Univariate logistic regression analysis assessed the association of different

factors and AF recurrence. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed

to evaluate whether AHR was an independent risk factor for AF recurrence. Exact

and asymptotic methods were applied to analyze unadjusted and adjusted estimates,

respectively. If a covariate changed the estimates of AHR on AF recurrence by

greater than 10% or had a significant association (p

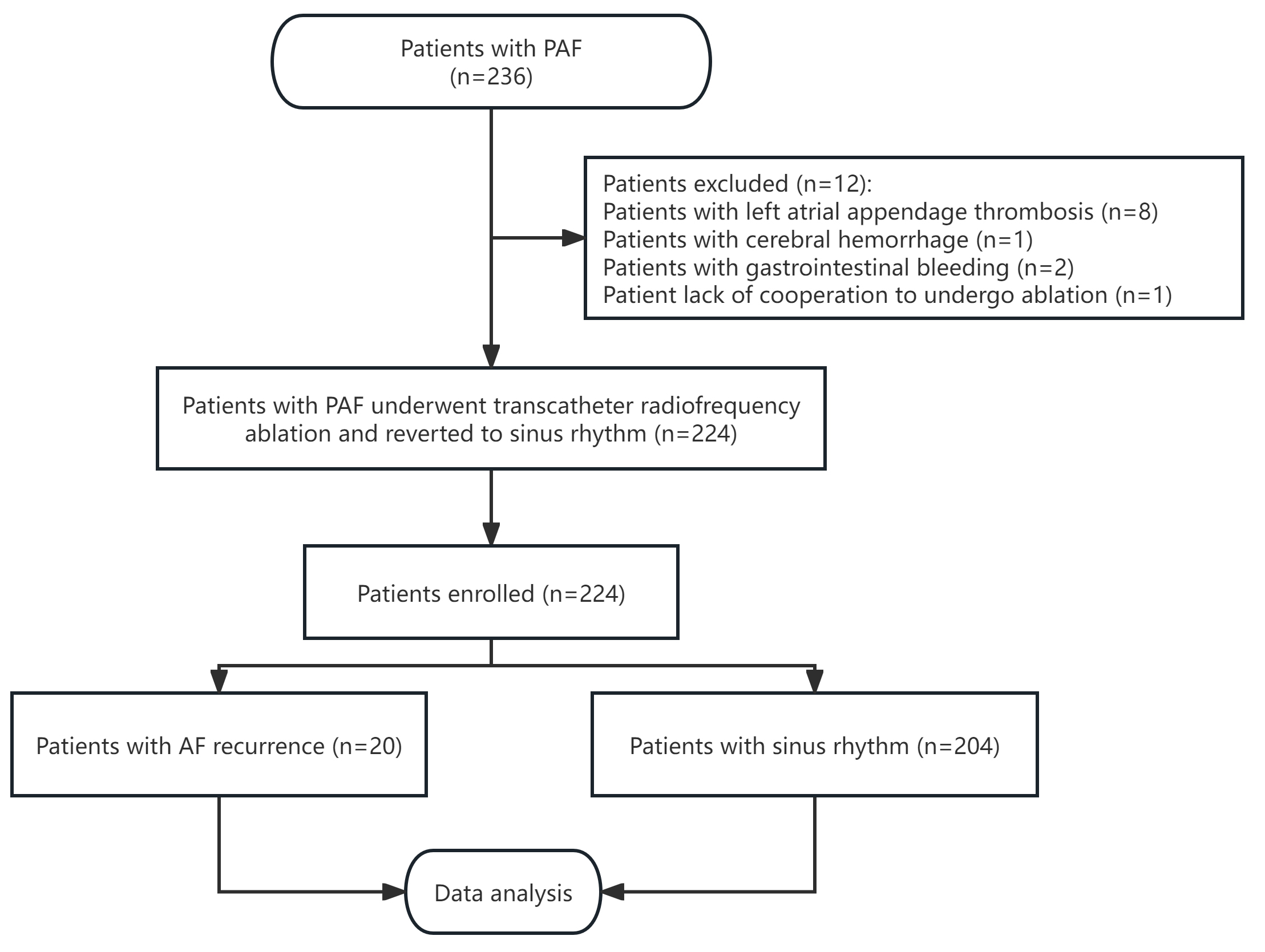

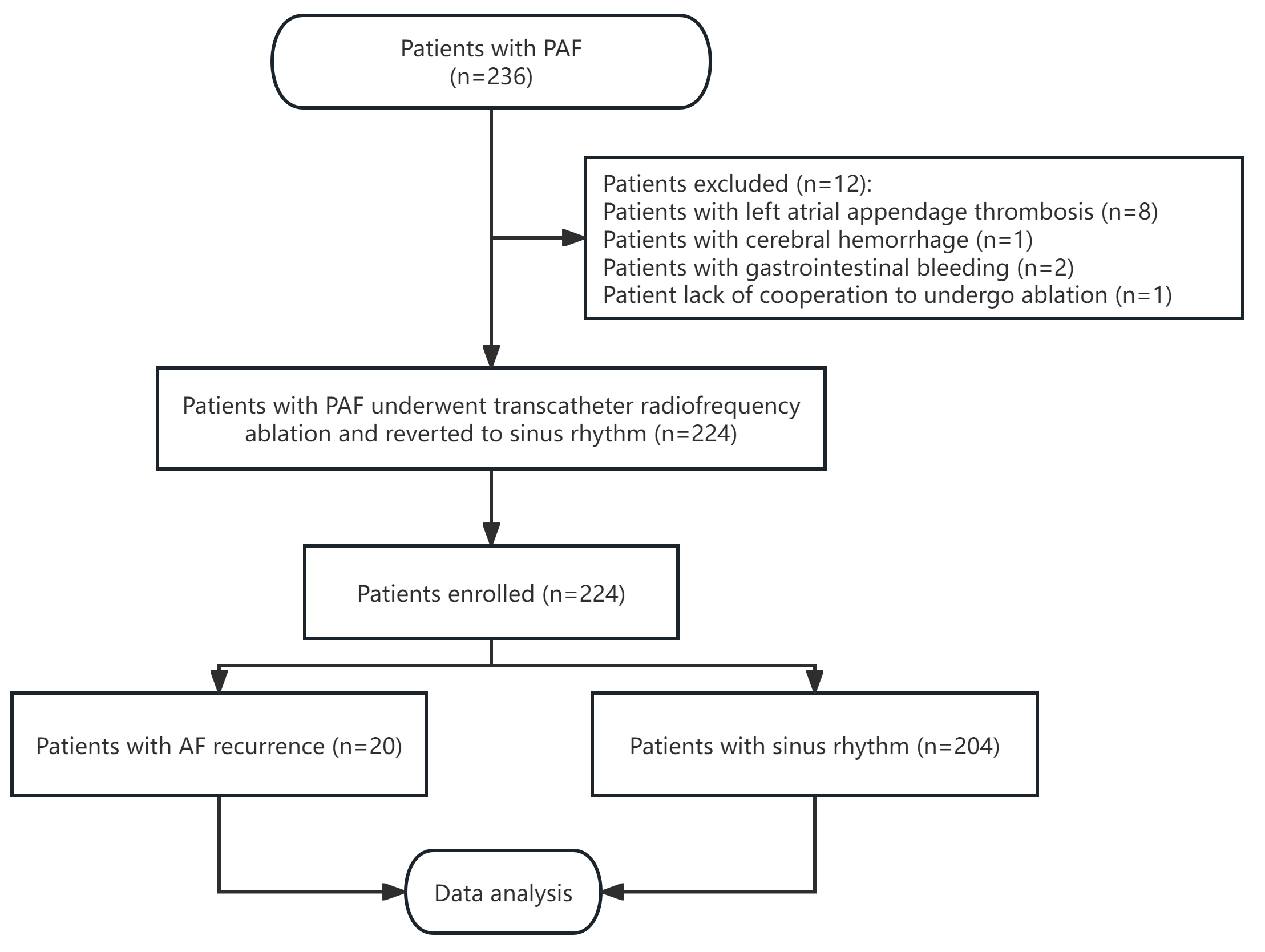

According to the inclusion criteria, 236 patients diagnosed with PAF were

enrolled in this study. Among the initial participants, eight patients were found

with left atrial appendage thrombosis, three experienced severe bleeding events

(one case of cerebral hemorrhage and two cases of gastrointestinal bleeding), and

one was unable to undergo RFA due to a lack of cooperation. Hence, these cases

were excluded from the final analysis. Consequently, 224 patients underwent RFA

and successfully reverted to sinus rhythm (Fig. 1). This group comprised 129

males and 95 females, averaging 61.500

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study. PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; AF, atrial fibrillation.

| AHR tertiles (bpm) | Total | Low | Medium | High | p-value | |

| 70–75 | ||||||

| N (cases) | 224.000 | 75.000 | 74.000 | 75.000 | ||

| Female, n (%) | 95 (42.411) | 35 (46.667) | 30 (40.541) | 30 (40.000) | 0.657 | |

| Age (years) | 61.500 |

62.707 |

60.838 |

60.947 |

0.381 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.569 |

24.589 |

24.483 |

24.633 |

0.962 | |

| AF duration (months) | 6.834 |

6.113 |

6.985 |

6.754 |

0.066 | |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.290 |

5.305 |

5.420 |

5.145 |

0.518 | |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.138 |

3.945 |

4.196 |

4.274 |

0.103 | |

| AHR (bpm) | 72.857 |

61.520 |

72.486 |

84.560 |

||

| Box-Cox transform (Total time of AF) | 0.550 |

0.547 |

0.550 |

0.552 |

0.058 | |

| Box-Cox transform (Total episodes of AF) | 5.411 |

5.231 |

5.449 |

5.553 |

0.080 | |

| Box-Cox transform (Proportion of time in AF) | 5.406 |

5.234 |

5.398 |

5.587 |

0.058 | |

| LAD (mm) | 39.342 |

40.627 |

39.095 |

38.274 |

0.043 | |

| LVEDD (mm) | 48.977 |

49.213 |

49.351 |

48.356 |

0.384 | |

| LVESD (mm) | 32.495 |

32.520 |

32.878 |

32.082 |

0.497 | |

| LVEF (%) | 61.338 |

61.453 |

60.892 |

61.671 |

0.629 | |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 135 (60.268) | 49 (65.333) | 41 (55.405) | 45 (60.000) | 0.464 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 25 (11.161) | 11 (14.667) | 8 (10.811) | 6 (8.000) | 0.429 | |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 29 (12.946) | 11 (14.667) | 6 (8.108) | 12 (16.000) | 0.308 | |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 36 (16.071) | 12 (16.000) | 10 (13.514) | 14 (18.667) | 0.693 | |

| History of stroke or TIA, n (%) | 21 (9.375) | 11 (14.667) | 5 (6.757) | 5 (6.667) | 0.156 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 68 (30.357) | 26 (34.667) | 28 (37.838) | 14 (18.667) | 0.024 | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 0.985 | |||||

| 0 | 39 (17.411) | 14 (18.667) | 12 (16.216) | 13 (17.333) | ||

| 1 | 78 (34.821) | 27 (36.000) | 25 (33.784) | 26 (34.667) | ||

| 105 (46.875) | 34 (45.333) | 37 (50.000) | 34 (45.333) | |||

| Smoking, n (%) | 49 (21.875) | 14 (18.667) | 19 (25.676) | 16 (21.333) | 0.580 | |

| Drinking, n (%) | 30 (13.393) | 12 (16.000) | 9 (12.162) | 9 (12.000) | 0.718 | |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs, n (%) | 0.304 | |||||

| Amiodarone | 35 (15.625) | 11 (14.667) | 11 (14.865) | 13 (17.333) | ||

| Dronedarone | 14 (6.250) | 5 (6.667) | 4 (5.405) | 5 (6.667) | ||

| Propafenone | 15 (6.696) | 4 (5.333) | 5 (6.757) | 6 (8.000) | ||

| Sotalol | 20 (8.929) | 6 (8.000) | 7 (9.459) | 7 (9.333) | ||

| 60 (26.786) | 18 (24.000) | 20 (27.027) | 22 (29.333) | |||

| AF recurrence, n (%) | 20 (8.929) | 11 (14.667) | 6 (8.108) | 3 (4.000) | 0.069 | |

Abbreviations: AHR, average heart rate; BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood–urea–nitrogen; TC, total cholesterol; AF, atrial fibrillation; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; TIA, transient ischemic attack; CHA2DS2-VASc, stroke risk score of AF patients; PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.

Using AF recurrence after RFA as the dependent variable and clinical parameters

and echocardiographic and dynamic electrocardiogram indicators, including AHR, as

the independent variables, a univariate logistic regression analysis was

performed to identify potential factors associated with AF recurrence. The result

showed that total time of AF, total episodes of AF, proportion of time in AF, AHR

in sinus rhythm state, LVEDD, LVESD, and LVEF were potential factors related to

AF recurrence (p

| Covariate | Statistics | OR | p-value | |

| Female, n (%) | 95 (42.411) | 1.123 (0.446, 2.828) | 0.806 | |

| Age (years) | 61.500 |

0.999 (0.951, 1.050) | 0.980 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.569 |

1.075 (0.944, 1.223) | 0.276 | |

| AF duration (months) | 6.834 |

1.059 (0.971, 1.134) | 0.776 | |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.290 |

0.898 (0.644, 1.252) | 0.525 | |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.138 |

1.067 (0.669, 1.703) | 0.785 | |

| AHR (bpm | 72.857 |

0.957 (0.913, 1.004) | 0.073 | |

| Box-Cox transform (Total time of AF) | 0.550 |

inf. (inf., inf.) | ||

| Box-Cox transform (Total episodes of AF) | 5.411 |

2.587 (1.822, 3.673) | ||

| Box-Cox transform (Proportion of time in AF) | 5.406 |

2.501 (1.765, 3.545) | ||

| LAD (mm) | 39.342 |

1.058 (0.978, 1.145) | 0.158 | |

| LVEDD (mm) | 48.977 |

1.131 (1.029, 1.243) | 0.011 | |

| LVESD (mm) | 32.495 |

1.180 (1.070, 1.302) | 0.001 | |

| LVEF (%) | 61.338 |

0.859 (0.791, 0.933) | 0.000 | |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 135 (60.268) | 0.632 (0.252, 1.587) | 0.329 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 25 (11.161) | 1.460 (0.396, 5.382) | 0.570 | |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 29 (12.946) | 1.208 (0.331, 4.409) | 0.775 | |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 36 (16.071) | 0.914 (0.254, 3.298) | 0.891 | |

| History of stroke or TIA, n (%) | 21 (9.375) | 0.000 (0.000, Inf.) | 0.991 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 68 (30.357) | 0.547 (0.176, 1.701) | 0.297 | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | ||||

| 0 | 39 (17.411) | Reference | ||

| 1 | 78 (34.821) | 1.043 (0.956, 1.142) | 0.419 | |

| 105 (46.875) | 1.114 (0.933, 1.14) | 0.657 | ||

| Smoking, n (%) | 49 (21.875) | 0.606 (0.170, 2.160) | 0.440 | |

| Drinking, n (%) | 30 (13.393) | 0.318 (0.041, 2.465) | 0.273 | |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs, n (%) | ||||

| Amiodarone | 35 (15.625) | 0.949 (0.263, 3.426) | 0.936 | |

| Dronedarone | 14 (6.250) | 0.773 (0.096, 6.239) | 0.809 | |

| Propafenone | 15 (6.696) | 1.632 (0.341, 7.809) | 0.539 | |

| Sotalol | 20 (8.929) | 1.148 (0.246, 5.350) | 0.860 | |

| 60 (26.786) | 0.661 (0.212, 2.062) | 0.475 | ||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood–urea–nitrogen; TC, total cholesterol; AHR, average heart rate; AF, atrial fibrillation; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; TIA, transient ischemic attack; CHA2DS2-VASc, stroke risk score of AF patients; OR, odds ratio; inf. (inf., inf.), it is suggested that the coefficient estimate corresponding to Box-Cox transform (total time of AF) tends to positive infinity, the OR is going to go to infinity.

Table 3 presented both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis outcomes, representing the AHR in the sinus rhythm state expressed as continuous variables and three tertiles, respectively. Model 0 corresponded to the unadjusted covariate equation, equivalent to the univariate logistic regression analysis. Model I was the preliminary adjusted covariate equation, which included adjustments for seven covariates: age, gender, BMI, peripheral vascular disease, LVEF, LVEDD, and total episodes of AF. Model II was the fully adjusted covariate equation, which included adjustments for nine covariates: age, gender, BMI, peripheral vascular disease, LVEF, LVEDD, total episodes of AF, total time of AF, and proportion of time in AF.

| Variable | Model 0 | Model I | Model II | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| AHR | 0.957 (0.913, 1.004) | 0.073 | 0.929 (0.875, 0.987) | 0.017 | 0.849 (0.729, 0.988) | 0.035 | |

| AHR tertiles | |||||||

| Low | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Medium | 0.513 (0.179, 1.469) | 0.214 | 0.254 (0.066, 0.975) | 0.046 | 0.121 (0.015, 0.982) | 0.048 | |

| High | 0.242 (0.065, 0.908) | 0.035 | 0.099 (0.017, 0.559) | 0.009 | 0.025 (0.001, 0.742) | 0.033 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; AHR, average heart rate; BMI, body mass index; AF, atrial fibrillation; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; OR, odds ratio.

Model I adjusted for gender, age, BMI, peripheral vascular disease, LVEDD, LVEF, and total episodes of AF.

Model II adjusted for gender, age, BMI, peripheral vascular disease, LVEDD, LVEF, total time of AF, total episodes of AF, and proportion of time in AF.

When AHR in a sinus rhythm state was treated as a continuous variable, the regression equations of Model I and Model II demonstrated that an increased preoperative AHR in patients with AF decreased the risk of recurrence after RFA. These findings were statistically significant in both models (odds ratio (OR): 0.929, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.875–0.987, p = 0.017; OR: 0.849, 95% CI: 0.729–0.988, p = 0.035; respectively).

Setting AHR in sinus rhythm state into three tertiles, we also observed a trend of increasing AHR being associated with a decreasing risk of AF recurrence in Model 0, Model I, and Model II regression equations (OR: 0.242, 95% CI: 0.065–0.908, p = 0.035; OR: 0.099, 95% CI: 0.017–0.559, p = 0.009; and OR: 0.025, 95% CI: 0.001–0.742, p = 0.033; respectively).

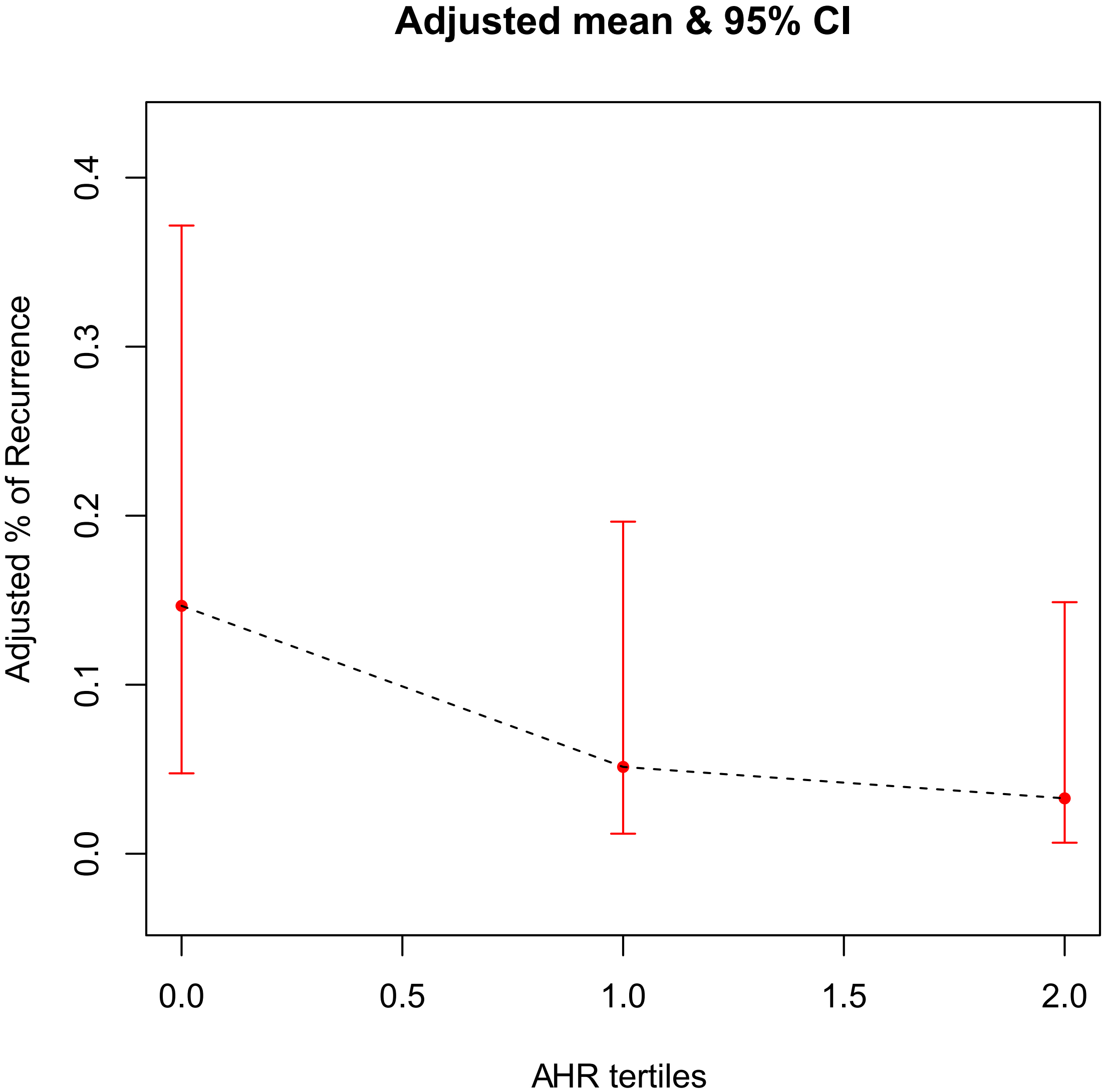

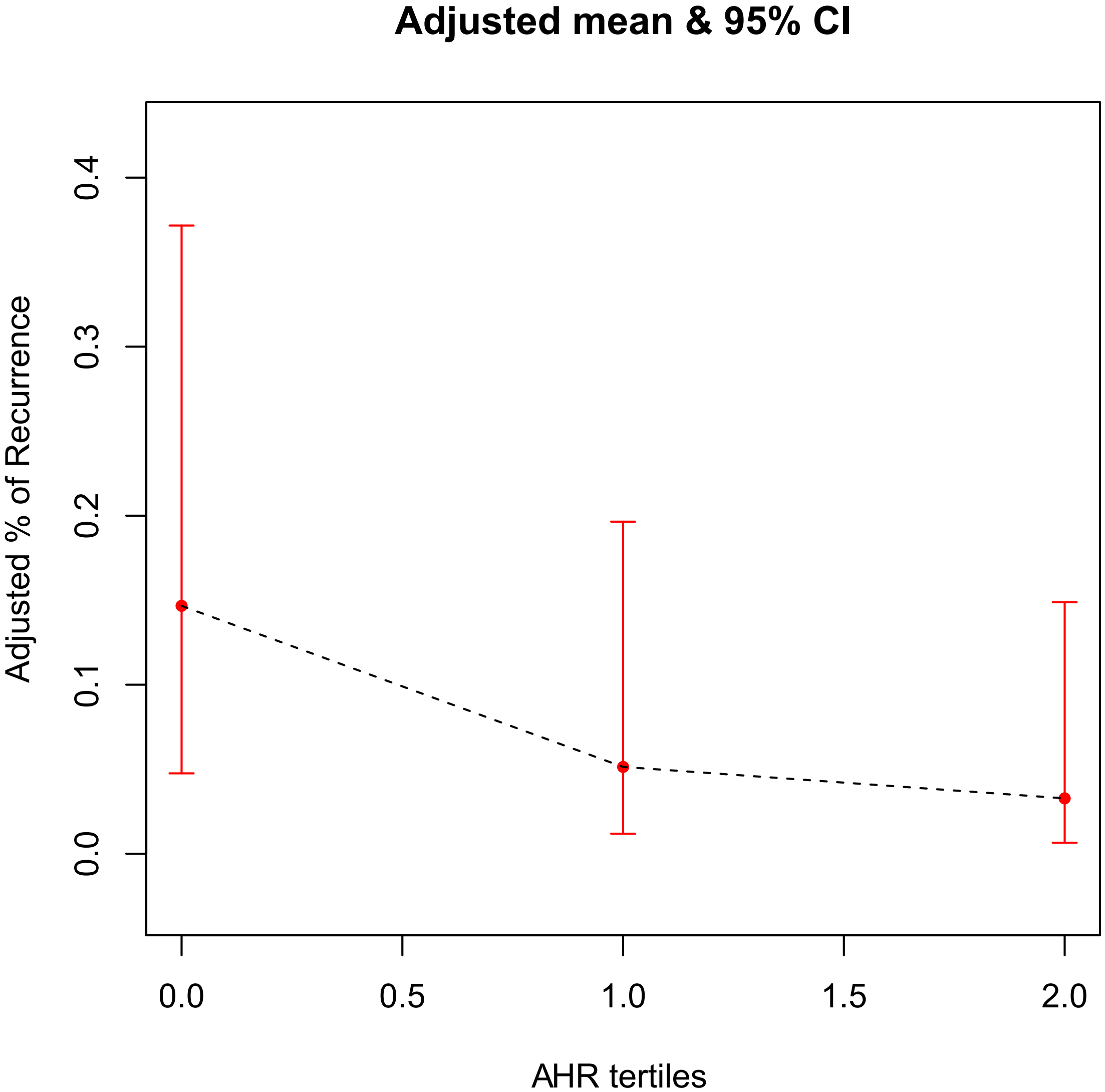

A generalized additive model was used to test the correlation between AHR and AF

recurrence. The finding revealed that, in the AHR tertiles groups, after being

fully adjusted for covariates such as age, gender, BMI, peripheral vascular

disease, LVEF, LVEDD, total episodes of AF, total time of AF and proportion of

time in AF, there was a gradual decrease in the probability of postoperative AF

recurrence as the grouping level increased. The two variables were approximately

linearly and negatively associated (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The association between AHR tertiles and AF recurrence risk. The black dotted line represents the fitted line between the recurrence rate of AF and the AHR tertiles, and the red line is the 95% confidence interval. AHR, average heart rate; AF, atrial fibrillation.

The findings of this study revealed that for patients with PAF, the recurrence rate of AF decreased with an increase in the AHR in the sinus rhythm state after achieving ventricular rate control before RFA.

In recent years, the management of AF has undergone revolutionary changes. Transcatheter RFA has become a first-line treatment option for drug-resistant and symptomatic PAF patients [5]. However, the high rate of AF recurrence after RFA often diminishes the benefits of ablation. Therefore, the early identification of risk factors for AF recurrence is crucial for detecting and treating such arrhythmias to prevent complications such as stroke.

The guidelines from the American Heart Association [28] suggest long-term

administration of a

Several scholars have researched the relationship between heart rate and the

development or recurrence of AF and found that a low heart rate can increase the

risk of both AF occurrence and postoperative recurrence. For example, O’Neal

et al. [29] showed that a decreased resting heart rate is associated

with an increased risk of AF, and this finding is consistent in subgroups of age,

gender, race, and coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. Other two large

independent cohort studies, namely the Copenhagen Electrocardiographic Study [30]

and the Tromsø Study [22], have discovered that a low resting heart rate

(

As previously mentioned, several studies demonstrated that patients with significantly increasing AHR post-ablation had a lower recurrence rate of AF. The cardiac autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays an important role in the pathophysiology of AF [5]. The intrinsic part of the ANS is located primarily in the ganglionated plexus (GP) [35], which primarily contains parasympathetic but also sympathetic neurons [36], considered to influence the sinus rate, atrial refractory period and atrioventricular conduction [37]. Most of the GP lie near the pulmonary vein ostia and left atrium junction [38, 39], where pulmonary vein isolation is operated. Therefore, inadvertent ablation of the GP is possible, which then contributes to the increase in post-ablation heart rate through parasympathetic denervation and could ultimately be relative to a lower recurrence rate of AF.

In this study, we demonstrated that the AHR in the preoperative sinus rhythm state in patients with PAF was negatively associated with the risk of postoperative AF recurrence, which various biological mechanisms can explain. Firstly, it was observed that patients with lower AHR had significantly larger LAD compared to those with higher AHR. This can be attributed to left atrial enlargement, which promotes electrical and anatomical remodeling of the left atrium and leads to the secretion of inflammatory factors, subsequent fibrosis, left atrial matrix remodeling [40], increased P-wave dispersion [41], prolongation of intra-atrial and inter-atrial conduction times [42], and significant atrioventricular block.All these changes increase sensitivity to AF. Secondly, maintaining sinus rhythm for at least three months after ablation is crucial for electrical and anatomical reverse remodeling of the left atrium. However, in patients with low preoperative AHR, the routine use of AAD becomes contraindicated, or the dosage is limited after ablation. This may result in difficulty maintaining sinus heart rate and delayed reverse remodeling of the left atrium, which can easily result in AF recurrence. Lastly, a low resting heart rate is associated with ANS activity or subclinical sinoatrial node dysfunction [29, 32]. On the one hand, the ANS activity is an important modulating factor in the perpetuation of AF [43]. Increased ANS activity shortens the duration of the action potential by increasing acetylcholine-dependent potassium current while also leading to calcium transients by increasing norepinephrine secretion [44, 45]. The above two factors jointly increase early post-depolarization potential, contributing to the formation of AF trigger potential [46] and subsequently increasing the recurrence rate of AF. Meanwhile, lower AHR could be an indicator of increased ANS activity, which may make successful GP ablation more difficult, while the addition of GP ablation has been confirmed to be related to reduced arrhythmia recurrence in PAF patients in a meta-analysis [47]. On the other hand, subclinical sinus node dysfunction is related to sinoatrial node dysfunction and age-related changes and fibrosis in the cardiac conduction system outside the atrial myocardium and sinoatrial node. These anatomical changes create a substrate for the development of AF. Additionally, the accompanying bradycardia further facilitates AF development by increasing the probability of atrial arrhythmias and dispersion of refractory periods [48].

Limitations: Firstly, this study was a retrospective cohort study conducted at a single center. The sample size was relatively small, and the follow-up period was short. Secondly, the multivariate logistic regression model included several potential confounding factors that could influence the development of AF. However, as with other epidemiological studies, residual confounding factors were still possible. For instance, our model did not fully adjust for the duration and severity of certain conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, and blood pressure and blood sugar control. Moreover, previous studies have shown that less postoperative heart rate increases compared to preoperation may be associated with higher postoperative AF recurrence [24, 31, 33, 34]; we will incorporate postoperative heart rate change parameters in the future to explore the risk of AF recurrence and possible mechanisms. Furthermore, the relationship between left atrial size and AF recurrence has been proved by several studies. In contrast, this study stated that left atrial size had no significant correlation with the recurrence of AF; this result may be relevant to the small sample and less left atrial remodeling in patients with PAF. In future research, we will expand the samples’ quantity and refine the evaluation of left atrial by adding left atrial volume and left atrial strain parameters to better explore the relationship between left atrial and AF recurrence. Finally, the mechanism underlying the occurrence of low preoperative AHR and postoperative recurrence in AF patients is currently unknown. Therefore, large-scale, multicenter, prospective case–control trials are still required to establish the correlation and mechanism between preoperative AHR and postoperative recurrence in patients with PAF.

In summary, the correlation between preoperative AHR in sinus rhythm state and the likelihood of postoperative AF recurrence offers valuable insights for risk stratification and clinical management of AF. Moreover, it serves as scientific evidence supporting the adjustment of preoperative AAD, intraoperative additional ablation of GP, and the identification and early intervention of high-risk patients prone to postoperative recurrence. In the case of AF patients with a low preoperative AHR, it is necessary to administer AAD with caution and to perform additional ablation of GP during RFA.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

MX designed the study and carried out the study, data collection and analysis. XF contributed to acquisition and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. LY made substantial contributions to conception and design and revised the manuscript. ZY and YM designed part of the experiments. MG and JM collected the PAF patients. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (2016TNo. 44). All patients or their families/legal guardians gave their written informed consent before they participated in the study.

We would like to give our heartfelt thanks to all the people who have ever helped us in this paper. We are really grateful to all those who devote much time to reading this paper and give us much advice, which will benefit us in our later study.

This study was supported by Changzhou Health Commission Youth Project (QN202208) and Top Talent of Changzhou “The 14th Five-Year Plan” High-Level Health Talents Training Project (2022260).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.