1 Department of Geriatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wannan Medical College, 241001 Wuhu, Anhui, China

Abstract

Cardiac hypertrophy is characterized by an increased volume of individual cardiomyocytes rather than an increase in their number. Myocardial hypertrophy due to pathological stimuli encountered by the heart, which reduces pressure on the ventricular walls to maintain cardiac function, is known as pathological hypertrophy. This eventually progresses to heart failure. Certain varieties of regulated cell death (RCD) pathways, including apoptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, necroptosis, and autophagy, are crucial in the development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. This review summarizes the molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways underlying these RCD pathways, focusing on their mechanism of action findings for pathological cardiac hypertrophy. It intends to provide new ideas for developing therapeutic approaches targeted at the cellular level to prevent or reverse pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

Keywords

- regulated cell death

- cardiac hypertrophy

- pyroptosis

- autophagy

- ferroptosis

Cardiac hypertrophy, an important risk factor underlying cardiovascular diseases, manifests as an increase in cardiomyocyte size rather than number in the adult heart owing to the terminal differentiation of cardiomyocytes shortly after birth [1]. Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy is distinguished by augmented cellular dimensions, heightened protein synthesis, and increased sarcomere tissue. The workload of cardiomyocytes is escalated during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by thickening the ventricular wall to sustain cardiac pumping, necessitated by augmented peripheral organ load. This is deemed as an adaptive and compensatory response. Cardiac hypertrophy is physiological or pathological, and the underlying molecular mechanisms, prognoses, and other aspects of the two differ greatly. Physiological cardiac hypertrophy is typically reversible [2], marked by increased heart mass and cardiomyocyte size [3]. Conversely, pathological cardiac hypertrophy, which is irreversible, is intertwined with processes, including autophagy and oxidative stress. It is characterized by the elongation of individual cardiomyocytes, cardiomyocyte death, ensuing progression of myocardial interstitial fibrosis, dysfunctional myocardial systole–diastole, perivascular fibrosis, and ultimately, attenuation of the ventricular wall, ventricular chamber dilation, and diminished cardiac output [4, 5]. This leads to several adverse cardiovascular events, such as heart failure, arrhythmias, and death [6]. Therefore, a comprehensive grasp of the molecular mechanisms that underlie pathological cardiac hypertrophy is promising for identifying novel drug targets and enriching therapeutic strategies.

Cell death is a multifaceted and interconnected process. Between 500 and 70 billion cells undergo this process daily within the adult body [7]. Regulated cell death (RCD) under physiological regulation is known as programmed cell death (PCD), which was initially synonymous with apoptosis and is recognized as an active, programmed cellular catabolic process that occurs autonomously without releasing cytoplasmic contents into the extracellular space [8]. However, additional types of RCD have been unveiled recently, including necroptosis and autophagy [9]. Mounting evidence indicates that different RCD and cytokine-type mechanisms regulate pathological cardiac hypertrophy development. Therefore, elucidating the mechanisms of interactions among various cytokines, cell death pathways, and pathological cardiac hypertrophy is expected to facilitate a better understanding of disease pathogenesis and progression.

Apoptosis is an evolutionarily conserved and inducible PCD type. In 1972, Kerr et al. [10] first proposed the notion of apoptosis and delineated its morphological characteristics, including nuclear and cytoplasmic condensation and degradation of apoptotic bodies by lysosomes. Apoptosis is mainly triggered through extrinsic and intrinsic signaling pathways [11]. Both pathways ultimately converge to caspase-3, which is involved in a protease cascade. Apoptotic caspases can be categorized as initiating caspases (caspases 8 and 9) and executioner caspases (caspases 3 and 7). These proteases are pivotal in cleaving regulatory and structural molecules, ultimately leading to nuclear apoptosis [12].

Extrinsic or cytoplasmic pathways trigger apoptotic signaling by binding to

death receptors on the cell surface. Death receptors are transmembrane proteins

with cysteine-rich extracellular and intracellular domains containing homologous

amino acid residues. The death domain (DD) is crucial in apoptotic signaling due

to its protein hydrolysis function [13]. Death ligands, including tumor necrosis

factor (TNF-

Intrinsic pathways, or mitochondrial pathways, are triggered by intracellular stressors, including DNA damage, oxidative stress, and loss of survival signals, which cause increased outer mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (MOMP) [17]. This pathway is regulated by the B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family of anti-apoptotic proteins, including the pro-apoptotic effector molecule, Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), and the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2 [18]. Upon stimulation, MOMP increases, releasing the pro-apoptotic factor cytochrome c and activating death signaling pathways. The release of cytochrome c from the inner mitochondrial membrane, an important electron transporter in the respiratory chain, blocks electron transfers downstream and compromises the respiratory chain, leading to an accelerated production of the superoxide anion. The Bcl-2 protein can inhibit this process. The binding of cytochrome c to the apoptosis-inducing factor apoptotic protease activating factor-1 (APAF-1) triggers the oligomerization of APAF-1 and the formation of apoptotic bodies that activate caspase-9, which, in turn, initiates the activation of caspase-3, propelling the mitochondrial cascade, and the activated caspases-3 degrades the substrate. The degradation products of the proteins cause changes in mitochondrial permeability, blocking the release of pro-apoptotic proteins from the mitochondria and ultimately leading to apoptosis [19].

Another apoptosis pathway, the perforin/granzyme-mediated signaling pathway, is mediated by cytotoxic T cells to perforate the cells, mainly through granzyme A or granzyme B, leading to apoptosis [20]. Granzyme B, a serine protease, triggers the caspase apoptotic pathway through caspase-3 cleavage and the direct proteolysis of numerous critical caspase substrates [21, 22]. Granzyme A-mediated is caspase-independent, granzyme A enters the target cell through perforin and crosses the mitochondrial membrane, blocking the mitochondrial electron transport chain without increased MOMP [23]; producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) that drive the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) associated SET (Su (var) 3-9, Enhancer of zeste, Trithorax) complex into the nucleus [24]. In the nucleus, granzyme A cleaves the SET complex to activate the nuclease in the complex and produce single-stranded DNA damage that ultimately causes the death of the target cell [25].

Some environmental chemicals, including heavy metals such as arsenic and copper, decompose and enter the natural aquatic environment. When the concentration exceeds the standard, apoptosis is induced in fish cells. Heat shock proteins 70 (HSP70) and metallothionein (MT) can strongly bind to metals but can hardly block apoptosis [26]. Nanoplastic can induce vascular inflammation and apoptosis of endothelial cells in vitro [27]. In a follow-up of 34 months in an observational study, patients with carotid plaques developed myocardial infarction and stroke or constituted a composite end point of the high risk for all-cause mortality [28].

In a healthy heart, apoptosis is extremely low. However, ischemia and resulting

hypoxia are well-known promoters of apoptosis. Pressure overload-induced

apoptosis is an early pathological feature of cardiac hypertrophy and myocardial

remodeling. Once activated, apoptotic cells are replaced by an extracellular

matrix, which damages cardiomyocytes, increases interstitial fibrosis, promotes

myocardial hypertrophy, and ultimately leads to heart failure [29]—study in

mice have confirmed this theory [30]. Accumulating evidence indicates that

apoptosis regulates pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Apoptosis promotes

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy through cell shrinkage, chromatin compaction, plasma

membrane blistering, and nuclear fragmentation [31]. Furthermore, interleukin-18

(IL-18) is a multifunctional pro-inflammatory cytokine and a potent inducer of

cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro. In a rabbit myocardial model of

myocardial infarction, IL-18 enhanced TNF-

Study found that increased expression of Bax, Fas, and FasL promotes persistent cardiomyocyte apoptosis in sinoaortic denervation rats, contributing to cardiac damage [34]. Additionally, a significant elevation in TNF-

The heart harbors the most mitochondria, comprising approximately 30% of the

volume of ventricular cardiomyocytes. Intracellular stressors activate

mitochondrial pathways. Apoptosis is correlated with the dysregulated activation

of the Wnt signaling pathway [38]. Activation of Wnt/

Amphiregulin (AREG), an epidermal growth factor receptor ligand, is widely expressed in cardiomyocytes. Downregulation of AREG in the mouse heart inhibits apoptosis and reduces myocardial hypertrophy by cleaving the pro-apoptotic proteins, Bax and caspase-3 [44]. Study in mice have found that granzyme B is elevated in a mouse model of cardiac fibrosis induced by angiotensin II. Granzyme B deficiency reduces angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis independent of perforin [45]. Therefore, apoptosis is crucial in pathological myocardial hypertrophy. A specific type of cell apoptosis, pyroptosis, has been recently discovered and confirmed to be intricately involved in the pathophysiology of numerous cardiovascular diseases, and pyroptosis-related regulatory pathways have been implicated in myocardial hypertrophy [46].

The concept of cellular pyroptosis was first introduced by Zychlinsky et al. [47] in 1992 by studying macrophages infected with Gram-negative Shigella hosts. They identified a form of cell death distinct from apoptosis, a form of cell death activated by caspase-1. In 2001, Cookson and Brennan [48] termed this inflammatory PCD as pyroptosis. Notably, pyroptosis can be initiated by various pathological stimuli and is characterized by its dependency on caspase-1, which leads to a pro-inflammatory response. Unlike other forms of RCD, pyroptosis involves swift disruption of the plasma membrane integrity, leading to the release of intracellular contents and inflammatory mediators into the extracellular compartment and consequent activation of an intense inflammatory response, which exploits intracellularly generated pores to disrupt electrolyte homeostasis and results in cell death [49]. Ultimately, pyroptosis leads to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and is linked to heightened membrane porosity, cell expansion, and DNA damage [50].

The classical pyroptosis pathway is mediated through caspase-1 by gasdermin D

(GSDMD). Specifically, pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) binds to

pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). The NOD-like receptor (NLR) family pyrin domain-containing 3

(NLRP3) inflammatory vesicles, a nod-like receptor, recognizes various stimuli,

including PAMP [51]. ROS is a key regulator of NLRP3 inflammasome activation

[52]. Meanwhile, ROS inhibition reverses NLRP3 inflammasome activation [51].

Following activation, the NLRP3 inflammasome assembles, leading to the activation

of caspase-1 [53]. Once activated, caspase-1 cleaves GSDMD at its central

junction, initiating partial oligomerization of its N-terminal domain. GSDMD-N

release results in pore formation in the cell membrane [54]. In the resting

state, GSDMD oligomerization is automatically inhibited by intramolecular binding

between the N and C termini [55]. However, cleavage of inflammatory caspase-1

reverses this autoinhibition. Concurrently, activated caspase-1 induces the

activation of two major pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1

Many recent studies have demonstrated that pyroptosis is associated with the pathogenesis of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Silica nanoparticles increased intracellular ROS production and activated the NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes, thereby inducing pyroptosis and promoting cardiac hypertrophy [57]. Specifically, NLRP3 inflammasomes facilitate the maturation and release of inflammatory cytokines by activating caspase-1 [58, 59]. Mouse experiments have revealed that large amounts of mtDNA are released into the cytoplasm of oxidatively stressed cardiomyocytes. Oxidative stress activates the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase and stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS–STING) signaling pathway in the hearts of mice with diabetic cardiomyopathy and induces the escape of mtDNA into cytoplasmic lysates. Stimulation of the cGAS–STING pathway subsequently activates the NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD-mediated pyroptotic pathway, contributing to advancing diabetic cardiomyopathy [60]. Targeted NLRP3 inhibition and gene silencing blocks caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis in cardiomyocytes and alleviated manifestations of cardiac hypertrophy [61]. Thus, pyroptosis serves a pathological role in cardiac hypertrophy, and inhibition of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles is a potential target for treating cardiac hypertrophy.

NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD is the classical pathway underlying cardiomyocyte

pyroptosis. Caspase-1 facilitates cardiomyocyte apoptosis and affects cardiac

hypertrophy through its downstream mediator, IL-1

Degterev et al. [65] introduced the concept of necroptosis in 2005. Necroptosis differs from apoptosis in that its progression does not involve caspase activation. Necroptosis is a form of cytolytic cell death resulting in a widespread inflammatory response through the release of endogenous molecules, typically in the form of perforation, rupture of cell membranes, swelling, disintegration of organelles, and leakage of cellular contents, with no obvious morphological changes in the chromatin of the nucleus [66].

Typically, necroptosis is mediated by the interaction of death signaling

molecules (TNF-

Caspase-8 triggers apoptosis by inhibiting necroptosis by cleaving RIPK1 and RIPK3 [72]. In death receptor-induced necroptosis signaling, RIPK3, a pivotal mediator of necroptosis, serves as a substrate for caspase-8-mediated proteolysis. Embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice can be rescued through RIPK3 knockdown, further demonstrating that caspase-8 inactivation promotes necroptosis. Upon inhibition of caspase-8 activity, RIPK1 and RIPK3 interact through the RHIM to form the RIPK1–RIPK3 necroptosis complex [73]. Therefore, two fundamental prerequisites for necroptosis have been identified: (1) the presence of RIPK3 and MLKL within cells and (2) the inactivation of caspase-8 [74].

Accumulating evidence indicates that necroptosis is important in cardiac hypertrophy, while the inhibition of necroptosis is expected to mitigate the progression of cardiac hypertrophy [75]. The expression of RIPK3 and RIPK1 was elevated in cardiomyocytes after treatment with palmitic acid in vitro. Knocking down RIPK3 or RIPK1 attenuated palmitic acid-induced myocardial hypertrophy; meanwhile, Nec-1 (necroptosis inhibitor-1, RIPK1 inhibitor) effectively blocked the expression of hypertrophic marker genes by inhibiting RIPK1. Additionally, caspase-8 activation was reversed, thereby underscoring the significance of necroptosis in mediating cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [76]. Xue et al. [77] established a rat model of cardiac hypertrophy by aortic narrowing, revealing a significant elevation in RIPK3 expression in hypertrophied myocardial tissues—the myocardial hypertrophy phenotype was reduced after RIPK3 downregulation. RIPK3 interacts with its downstream target, MLKL, to promote its localization to the cell membrane and increases the influx of intracellular calcium, thus facilitating the progression of myocardial hypertrophy. Similarly, RIPK3 deficiency alleviates myocardial necroptosis, mitigates oxidative stress, and improves myocardial mitochondrial ultrastructure in mice with cardiac hypertrophy. To a certain extent, the downregulation or depletion of RIPK3 attenuates myocardial necroptosis and mitigates myocardial hypertrophy [78, 79].

The RIPK1–RIPK3–MLKL necroptosis complex disrupts cell membrane integrity, causing cell swelling and rupturing, nuclear abscess and lysis, and the release of cellular contents, thereby stimulating innate immune activation and inflammatory responses [80]. Several studies have shown that in diseased myocardial tissues, necroptosis is dependent on the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL cascade and is regulated by the RIPK3/(Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) signaling pathway. CaMKII is a newly identified substrate of RIPK3, which mediates necroptosis by activating CaMKII to mediate ischemia and oxidative stress (OS) to trigger myocardial necroptosis [81]. Specifically, RIPK3 can directly phosphorylate CaMKII or indirectly oxidize CaMKII through ROS, which promotes the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), increases mitochondrial membrane permeability, decreases mitochondrial membrane potential, inhibits the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation reaction, and promotes ROS production, ultimately causing necroptosis in cardiomyocytes and promoting pathological cardiac hypertrophy [82].

Iron is a key trace element in living organisms, essential for various biological processes, including cellular respiration, DNA synthesis, and redox reactions. However, when iron ions are present in cells above normal levels, they may trigger harmful oxidative stress, damaging cell membranes, proteins, and DNA, ultimately leading to cell death. Initially conceptualized by Dr. Brent R. Stockwell in 2012, ferroptosis represents a distinct form of RCD characterized primarily by lipid peroxidation induced by iron overload [83]. Unlike other RCD pathways, ferroptosis lacks typical features such as cell swelling, plasma membrane disruption, chromatin condensation, and nuclear fragmentation. Instead, it is characterized by diminished or absent mitochondrial cristae, reduced mitochondrial volume, increased density, and outer membrane rupture [84].

Under physiological conditions, iron is primarily absorbed as Fe2+, while Fe3+ binds to transferrin (TF) in the serum and is recognized by transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1) on the cell membrane. After absorption by TFR1, the STEAP3 metalloreductase in the endosome reduces Fe3+ to Fe2+. Divalent metal transfer protein 1 (DMT1, or SLC11A2) mediates the entry of Fe2+ into the unstable iron pools in the cytoplasm, where it is stored in the iron pool, ferritin, crucial for maintaining iron levels [85]. Glutathione (GSH) and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) are negative regulators of ferroptosis as they limit ROS production and reduce cellular iron uptake. When GSH is depleted, or GPX4 is inactivated, and the iron pool is overloaded with Fe2+, nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) can translocate ferritin into the autophagosome for lysosomal degradation, resulting in the release of free iron [86, 87]. When iron homeostasis is dysregulated, and the balance of iron metabolism is disrupted, massive amounts of free iron are generated through the Fenton reaction to produce large amounts of ROS and lipid peroxide (LPO), which directly damages intracellular substances and destroy structures, leading to rapid cell death, a process known as ferroptosis [88].

The involvement of ferroptosis in pathological cardiac hypertrophy remains understudied. However, several studies have identified the modulation of pathological cardiac hypertrophy by ferroptosis. Zhou et al. [89] used pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ), a natural water-soluble oxidoreductase coenzyme, to treat TAC model mice with cardiac hypertrophy. PQQ suppressed cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting ferroptosis in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes in vivo. Similarly, Xu et al. [90] found that nuclear suffix domain 2 (NSD2), a methyltransferase, promotes pathological cardiac hypertrophy by activating ferroptosis signaling in TAC mice. Mixed-spectrum kinase MLK regulates necroptosis in cardiac hypertrophy, and its family member MLK3 is elevated in a pressure load-induced mouse model of cardiac hypertrophy. MLK3 depletion inhibits ferroptosis and expression of oxidative stress-related proteins, thereby exerting a protective role in cardiac hypertrophy [91]. The ferroptosis deterrent protein, cystine/glutamate transporter (xCT), is an Ang II-mediated cardiac hypertrophy inhibitor. xCT inhibition exacerbates cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and elevates Ang II-induced ferroptosis biomarkers, including Ptgs2, malondialdehyde, and ROS [92]. Mouse experiments have proven that ferroptosis exacerbates pathological cardiac hypertrophy [93].

The nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide–sirtuin 1 (NAD–SIRT1) pathway may be an important mechanistic pathway in regulating

cardiac hypertrophy through ferroptosis. SIRT1 is a NAD-dependent nuclear histone

deacetylase that regulates histone deacetylase activity by deacetylating various

histone proteins [94]. The NAD–SIRT1 pathway is closely associated with

ferroptosis, with SIRT1 sensitizing cells to ferroptosis by depleting NAD+ and

exerting an inhibitory effect on ferroptosis by upregulating GPX4 [95].

SIRT1 inhibits ferroptosis by inhibiting oxidative stress. When excess iron is ingested, the body can use ferritin to resist iron toxicity; however, the absence of cardiac ferritin increases ROS production [97]. SIRT1 activation or overexpression in vitro can prevent cardiac hypertrophy by blocking pro-inflammatory pathways [98, 99]. Specifically, SIRT1 activation finally alleviates cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting the ROS-induced TGF1/Sma and mad homolog 3 (Smad3) signaling pathway [100] and inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation [101].

Autophagy, a cellular self-catabolic process, upholds intracellular stability by degrading organelles, proteins, and other cellular structures through lysosomal degradation, facilitating the removal of damaged organelles and metabolites and providing nutrients to meet cellular requirements. The autophagic process unfolds in two key stages: intracellular targets are enveloped by membrane structures, resulting in the formation of autophagosomes; subsequently, these autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes, leading to the degradation of the enclosed material by autophagic lysosomes. Autophagy is a pivotal regulator of the delicate balance between cell survival and death, exerting the capacity to promote or inhibit cell death [102]. However, excessive autophagy is associated with diverse varieties of caspase-dependent cell death types, termed “autophagic cell death” [103]. Moreover, autophagy is critical for sustaining cellular viability and maintaining energetic homeostasis.

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (PKB) (Akt)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway has garnered significant attention recently due to its pivotal involvement in autophagy regulation. PI3K initiates this pathway by facilitating cell membrane formation, subsequently activating its downstream target, Akt, which is translocated to the cell membrane. Akt phosphorylates mTOR to modulate autophagy. mTORC1, an mTOR complex, suppresses autophagy by inhibiting the formation of downstream Unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) and ULK2 autophagy vesicles [104]. Thus, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway exerts a negative regulatory effect on cellular autophagy. The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/mTOR/ULK pathway is also a crucial regulator of autophagy. AMPK, a key player in energy and metabolic homeostasis, forms a heterotrimeric complex and is widely expressed in metabolic organs [105]. AMPK activation is a positive regulator of autophagy. AMPK promotes autophagy by activating ULK1 directly through phosphorylation or indirectly by inhibiting mTOR, which normally acts as a brake on autophagy [105]. Consequently, cellular autophagy exhibits a dual role, with pathological overactivation and inhibition. Dysregulated autophagy adversely affects cellular metabolism and various organ systems within organisms.

Autophagy removes damaged mitochondria accumulated in hypertrophied myocardium, reducing ROS production in cardiomyocytes. Mitochondrial autophagy in cardiomyocytes is mainly orchestrated through the cytoplasmic E3 ubiquitin ligase, Parkin, and the mitochondrial membrane kinase phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) [106]. PINK1 is a serine/threonine kinase localized on the surface of mitochondria and selectively stabilized in the organelle. During mitochondrial depolarization, the electrochemical potential is reduced, and Parkin is recruited to mitochondria for E3 ubiquitin ligase activation [106, 107]. Hence, optimal levels of physiological autophagy are indispensable for maintaining cellular homeostasis. However, excessive or insufficient aberrant autophagic activity can disrupt metabolic equilibrium in cardiomyocytes, facilitating the progression of cardiac hypertrophy.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that autophagy inhibition attenuates

pathological cardiac hypertrophy. LncRNA Gm15834 acts as an endogenous sponge RNA

for microRNA-30b-3p and is downregulated during cardiac hypertrophy. MiR-30b-3p

inhibition enhances autophagic activity in cardiomyocytes, exacerbating cardiac

hypertrophy, while miR-30b-3p overexpression inhibits autophagy-induced cardiac

hypertrophy by targeting autophagy factors downstream of ULK1 [108]. Xie

et al. [109] demonstrated that knocking down the immune subunit

Akt signaling and its downstream targets have been implicated in cardiac hypertrophy. Akt is an important regulator of cardiac hypertrophy, and sustained Akt activation is associated with the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, leading to pathological cardiac hypertrophy associated with mitochondrial dysfunction [111]. Zhang et al. [112] showed that calpain 1-mediated mTOR activation mitigated hypoxia-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Zhao et al. [113] observed the activation of mTOR and its downstream effectors in aortic arch narrowing-induced cardiac hypertrophy models, along with the downregulation of autophagy markers and reduced myocardial autophagy levels. Protein kinase D, a member of the calmodulin kinase family, regulates autophagy through the Akt/mTOR pathway, participating in cardiac hypertrophy. In contrast, knockdown by the corresponding siRNA inhibited pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, and myocardial autophagy levels were upregulated. Lower autophagy can lead to cardiac hypertrophy. Thus, myocardial autophagy exerts dual effects on cardiac hypertrophy.

Mitochondria are the power source of cells and the main source of ROS generation in cardiomyocytes; thus, mitochondria are crucial in cell death. ROS induces oxidative stress, activates ER stress sensors, transmits apoptotic signals, impairs the antioxidant defense system of cardiomyocytes, and induces cardiac hypertrophy [114, 115]. During necroptosis, ROS production is an effector of the RIP/RIP3/MLKL signaling pathway mediating necroptosis [116]. RIPK3 can indirectly oxidize CaMKII through ROS, opening MPTP, increasing mitochondrial membrane permeability, and causing cardiomyocyte necroptosis [82]. An increase in mitochondrial membrane permeability represents the initial factor of apoptosis. Simultaneously, ROS can induce lipid peroxidation, promoting ferroptosis and autophagy [117, 118]. Autophagy regulation through the ROS signaling pathway can alleviate nicotine-induced cardiac hypertrophy [119].

In ferroptosis, iron can produce excessive ROS through the Fenton reaction. Under physiological conditions, ROS is scavenged by autophagy, a process that can also regulate ferroptosis by removing damaged mitochondria and lipid peroxide [120]. However, excessive autophagy can cause ferritin degradation and induce ferroptosis [121]. Reducing autophagy, ferritin decomposition, and iron content reduction alleviated ferritin-induced oxidative damage and ferroptosis [122]. Additionally, knocking down autophagy-related genes (ATG) increases ferritin content and suppresses ferroptosis. Further, a crosstalk exists between mitophagy and apoptosis. As cell stress increases, mitophagy fails to protect the cell, thus triggering apoptotic signals [123]. Knocking down ATG5 leads to cardiomyocyte apoptosis [124]. The anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2, can bind to the autophagy protein, Beclin-1, involved in the formation of autophagosomes and regulates autophagy and apoptosis [125]. When mitophagy is inhibited, damaged mitochondria cannot clear ROS and can directly activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, eventually leading to pyroptosis [126]. Metformin can promote autophagy through the mTOR signaling pathway, inhibit the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, regulate cell pyroptosis, and alleviate cardiac hypertrophy [127].

When the myocardium is stimulated by factors such as hypoxia, mechanical stress, oxidative stress, and neurohumoral overactivation, cardiomyocytes produce and secrete angiotensin II (Ang II), further activating the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS). Continuous Ang II activation can lead to cardiomyocyte apoptosis and induce cardiac hypertrophy [128, 129]. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is involved in protein folding, calcium homeostasis, and lipid biosynthesis. During dysregulated protein homeostasis, ER stress-mediated activation of caspase 12 is a marker of maladaptation and an inducer of apoptosis [130]. An increase in soluble free radicals caused by oxidative stress leads to an imbalance in the intracellular redox environment. Myocardial metabolic demand increases, excess free radicals produce damaged cells, and NADPH oxidase produces ROS, which can induce lipid peroxidation through a reaction with polyunsaturated fatty acids in the lipid membrane, ultimately causing ferroptosis of myocardial cells through the Fenton reaction [88]. ROS also stimulates ER stress and promotes apoptosis of cardiomyocytes during hypertension, leading to hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes and activation of myocardial fibroblasts [131, 132].

When the heart is under pressure overload stress, excessive pro-inflammatory

factor secretion recruits macrophages into the heart. Cardiac macrophages secrete

transforming growth factor (TGF-

Metabolic disturbances can sensitize cardiomyocytes to various forms of cell

death, and diabetic cardiomyopathy, a common heart disease in diabetic patients,

can lead to cardiac hypertrophy. Notably, when rat cardiomyocytes are stimulated

by high glucose, caspase-1, IL-1

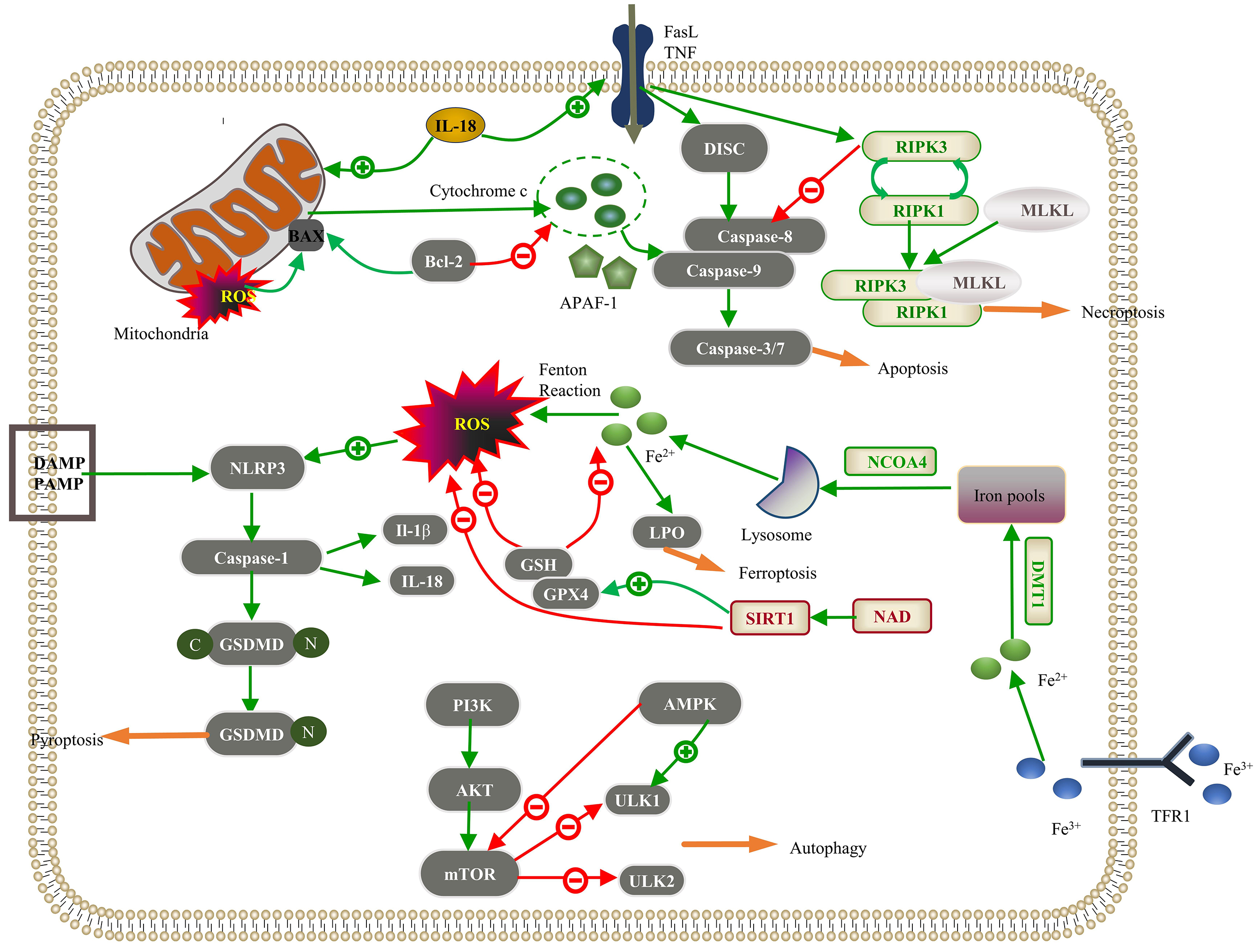

Emerging evidence underscores the pivotal role of various modes of RCD pathways in orchestrating the intricate network governing the progression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Findings from clinical samples, in vitro studies, and animal models collectively highlight the involvement of multiple forms of RCD, including apoptosis, autophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis, in regulating pathological cardiac hypertrophy through distinct signaling pathways (Fig. 1). Interconnections between these diverse RCD pathways suggest intricate crosstalk, necessitating comprehensive exploration in the future. Clinical management of cardiac hypertrophy predominantly relies on existing hypertensive medications; however, their efficacy remains limited. A deeper comprehension of the molecular and cellular mechanisms governing RCD is promising for identifying specific drug targets, designing and developing new drugs against these pathways, and integrating drug therapy, gene therapy, stem cell therapy, and other approaches to intervene in cell death pathways. Furthermore, the exact percentage of cardiomyocyte loss attributable to each RCD pathway remains unclear, highlighting a crucial area for future investigation. An in-depth study of the regulatory mechanism of RCD in pathological cardiac hypertrophy offers many opportunities and challenges for future treatment strategies. We anticipate that targeting RCD pathways will emerge as a viable therapeutic strategy for pathological cardiac hypertrophy in the foreseeable future.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Regulated cell death (RCD) pathways implicated in pathological

cardiac hypertrophy. Apoptosis: The intracellular damage signal in the intrinsic

pathway releases cytochrome c through mitochondrial outer membrane

permeabilization (MOMP), which integrates with apoptotic protease activator

factor-1 (APAF-1) to activate caspase-9; Bcl-2 inhibits this process. In the

extrinsic pathway, the death ligand binds to the death receptor, forming a

death-inducing signaling complex (DISC), which activates caspase-8. These jointly

activate the “executor” function of caspase-3/7 in apoptosis. Interleukin-18

(IL-18) promotes intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Necroptosis: The interaction

between the death receptor and the membrane receptor initiates the death receptor

signal and activates receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 3

(RIPK3). Upon inhibition of the caspase-8 activity, the interaction between RIPK1

and RIPK3 leads to the autophosphorylation of RIPK3, further activating mixed

lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) and leading to MLKL oligomerization.

RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL proteins form a necrotic signaling complex, which induces

necroptosis. Autophagy: The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian

target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway inhibits downstream Unc-51-like

kinase 1 (ULK1) and ULK2 to suppress autophagy, and AMP-activated protein kinase

(AMPK) inhibits mTOR to promote autophagy. Pyroptosis: Pathogen-linked molecular

patterns (PAMPs) or damage-linked molecular patterns (DAMPs) activate the NLR

family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3), activating caspase-1. Reactive oxygen

species (ROS) promote NLRP3 activation, and caspase-1 hydrolyzes gasdermin D

(GSDMD) to produce GSDMD-C and GSDMD-N. GSDMD-N polymerizes on the cell membrane

to form a nonselective membrane pore; caspase-1 can also cleave IL-1

SNW conceived the idea, collected literature, and drafted the manuscript. DD participated in the design and reviewed relevant literature. DGW contributed to the conception of the review and provided critical revisions for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We thank all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81670301) and Key Research and Development Projects of Science and Technology Department of Anhui Province (No. 2022e07020019).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.