1 Division of Cardiology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital Linkou Medical Center, 333423 Taoyuan, Taiwan

2 Healthcare Center, Taoyuan Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, 333008 Taoyuan, Taiwan

3 Department of Internal Medicine, Taoyuan Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, 333008 Taoyuan, Taiwan

4 Department of Applied Statistics and Information Science, Ming Chuan University, 333321 Taoyuan, Taiwan

5 Artificial Intelligence Development Center, Fu Jen Catholic University, 242062 New Taipei City, Taiwan

6 Department of anatomy, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, 333323 Taoyuan, Taiwan

7 Graduate Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Chang Gung University, 333323 Taoyuan, Taiwan

8 Heart Failure Center, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital Linkou Medical Center, 333423 Taoyuan, Taiwan

Abstract

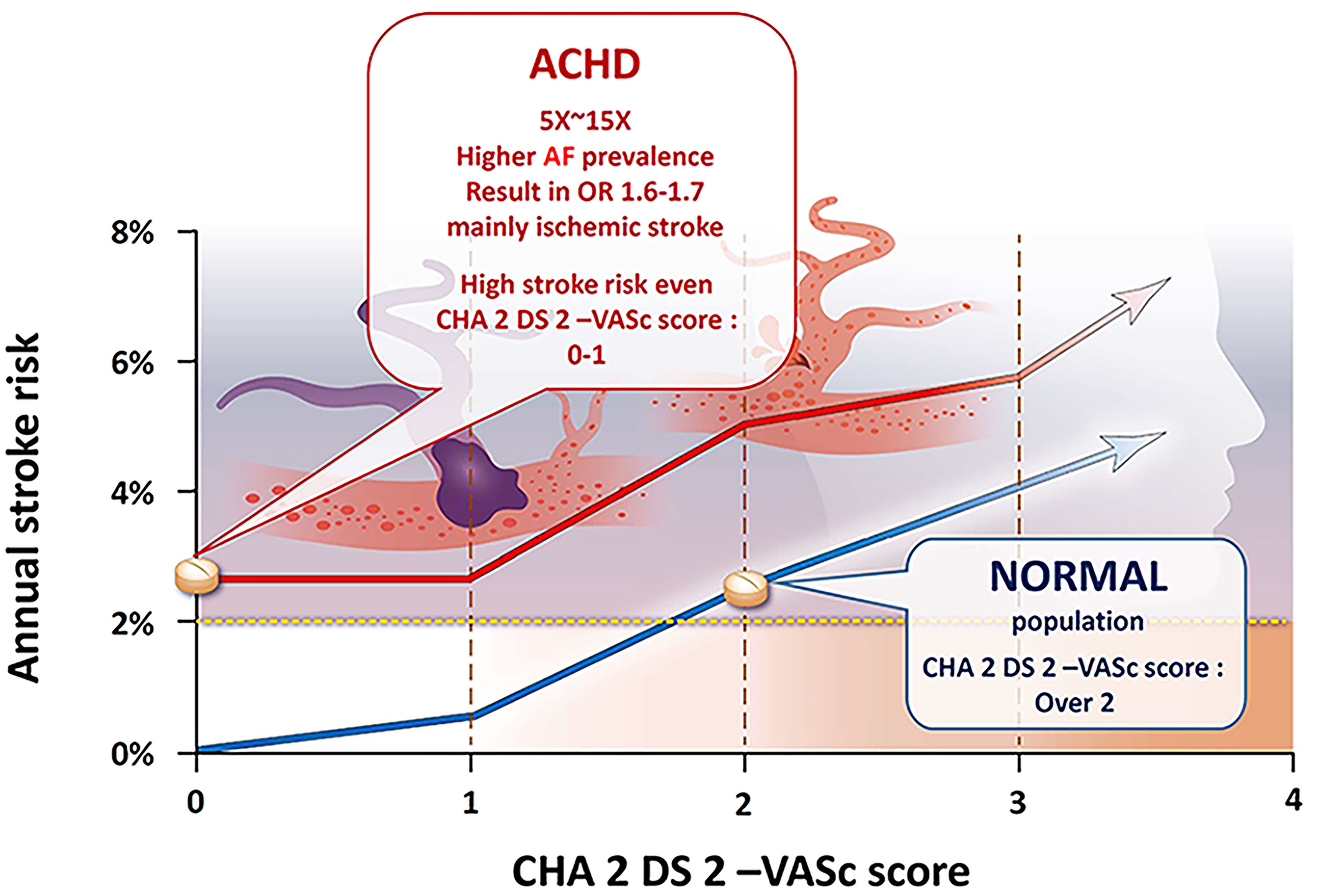

Background: The population of adults with congenital heart diseases

(ACHDs) is expanding, and atrial fibrillation (AF) emerges as a crucial risk

factor for ischemic stroke. However, the evidence regarding the impact of AF on

the incidence of ischemic stroke in ACHDs remains limited. In this study, we

aimed to investigate the prevalence and effect of AF among ACHDs and assess the

suitability of the traditional CHA₂DS₂-VASc score in this specific population.

Methods: Data of ACHDs from 2000 to 2010 were retrospectively collected

from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database. We divided ACHDs

into those with and without AF, and ischemic stroke incidence was studied among

ACHD subtypes and those who received anticoagulant therapy with warfarin or not

according to CHA₂DS₂-VASc score. Results: 36,530 ACHDs were retrieved

from the database. ACHDs had a 4.7–15.3 times higher AF risk than did the

general population, which varied based on the age group. ACHDs with AF had 1.45

times higher ischemic stroke risk than those without AF (p = 0.009).

Ischemic stroke incidence among ACHDs with AF aged

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- adult congenital heart disease

- atrial fibrillation

- ischemic stroke

- anticoagulation

- CHA2DS2-VASc score

The prevalence of congenital heart disease (CHD) worldwide is currently estimated to be 9 per 1000 newborns, with significant geographic variability [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Although the prevalence of severe CHD is decreasing in many Western/developed countries due to fetal screening and pregnancy termination, the overall global prevalence of CHD is increasing [6]. This may be attributed to various factors such as improved diagnosis and increased survival rates due to advancements in medical, surgical, and technological interventions. In fact, more than 90% of individuals born with CHD now survive into adulthood as a result of these advancements over the past few decades [2, 7, 8]. CHD cannot be completely cured; therefore, adults with CHD (ACHD) have a high risk of cardiovascular complications, including arrhythmia, stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction, as well as their early manifestation and a shortened lifespan [9, 10, 11, 12].

Arrhythmia is the most common cause of unscheduled hospital visits in ACHDs and accounts for one-third of all emergency admissions in this population [10, 13]. Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most powerful risk factor for stroke, conferring a four- to seven-fold increased risk in the general population [14]. Dr. Pedersen [15] used Danish nationwide registries to demonstrate that young ACHD patients have a higher risk of ischemic stroke compared to the general population, even at low CHA

Therefore, this retrospective study evaluated the association between AF and stroke in ACHDs and the accuracy with which the CHA

We retrospectively collected the longitudinal claims data of all individuals with CHD between 2000 and 2010 from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) (http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/date_01.html). The national health insurance program in Taiwan was launched in 1995, and it universally and successfully provides quality health care at an affordable cost. More than 99.6% of the residents of Taiwan are covered under the program, and medical records are stored in the NHIRD, which is updated biannually. All patients with major diseases, including ACHD, must be registered in the Registry for Catastrophic Illness Patients database (http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/date_01.html).

In Taiwan, suspected ACHDs are referred to cardiologists for echocardiographic diagnosis and treatment, and the majority of them are followed up at medical centers. The diagnosis of ACHDs, whether inpatient or outpatient, is made based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, and the accuracy of the diagnosis is verified by a hospital-based insurance claims data to ensure its validity. Hospitals that file inaccurate claims may be penalized by the National Health Insurance Bureau. In addition, patients who receive a catastrophic illness certificate are exempted from copayments pertaining to their condition in Taiwan. The CHD diagnoses can be classified into cyanotic CHD (tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), ICD-9-CM code 745.2; common truncus, ICD-9-CM code 745.0; double-outlet right ventricle, ICD-9-CM code 745.11; or other cyanotic CHDs, ICD-9-CM codes 745.1, 745.12, 745.3, 746.1, 746.7, and 747.41) and noncyanotic CHD (ventricular septal defect (VSD), ICD-9-CM code 745.4; ostium- or secundum-type atrial septal defect (ASD), ICD-9-CM code 745.5; congenital pulmonary stenosis (PS), ICD-9-CM code 746.02; or other noncyanotic CHDs, ICD-9-CM codes 745.60, 745.6, 746.2, 746.3, 746.82, and 747.1). In addition, patent ductus arteriosus was not included because it is generally not considered to be ACHD.

AF diagnosis was ascertained if an ICD-9-CM code of 427.31 was listed in the secondary discharge diagnosis of stroke hospitalization, in at least one subsequent inpatient claim, or in at least two subsequent outpatient claims. The primary outcome of this study was hospitalization, with a principal discharge diagnosis of stroke events during the study period. The stroke refers to ischemic stroke only (ICD-9-CM codes 433-434), excluding hemorrhagic stroke, cryptogenic stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA). The diagnostic codes of AF and strokes have been validated in previous NHIRD studies [19, 20, 21, 22, 23].

The comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, congestive heart failure, prior stroke or TIA or thromboembolism, vascular disease, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, and CHA

ACHDs were identified from the Registry for Catastrophic Illness database, which is a sub-database of the NHIRD, between 2000 and 2010. Among ACHDs, the date of the first AF diagnosis (either before or after the CHD diagnosis) was considered the cohort entry date in the AF group. We further assigned the cohort entry date of ACHDs with AF to ACHDs without AF. This assignment approach is termed as “prescription time-distribution matching” which is known to deal with the immortal time bias [24]. We further matched the two groups at a 1:1 ratio based on sex, age group (18–54, 55–64, 65–74, and

The SAS statistical package (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. The risk of stroke events between the AF ACHD and non-AF ACHD groups was compared using the Cox proportional hazard model. Further, patients who underwent mechanical valve surgery are obligatory treated with warfarin lifelong, therefore a sensitivity analysis by excluding the patients who received mechanical valve surgery was conducted (the matching was re-performed).

Furthermore, subgroup analysis was performed based on the age group and CHD type. Finally, after excluding patients receiving antiplatelet therapy, we evaluated whether warfarin use was associated with ischemic stroke occurrence in ACHDs with AF. ACHDs with AF were subgrouped based on warfarin use and CHA

A total of 36,530 ACHDs were enrolled. Compared with the general population, ACHDs have an increased prevalence of AF in the 55–65 age group (up to 12.1 times in men and 15.3 times in women; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Difference in the prevalence of atrial fibrillation (Afib) between the general population and adults with congenital heart diseases (ACHDs). (A) Male population. (B) Female population.

The baseline characteristics of ACHDs in the AF and non-AF groups after matching are presented in Table 1. The mean age was approximately 54 years, with no significant differences in age, sex, CHA

| Variables | AF ACHD (N = 1244) | Non-AF ACHD (N = 1244) | p value | |

| Sex (%) | Female | 686 (55.1) | 659 (53.0) | 0.296 |

| Male | 558 (44.9) | 585 (47.0) | ||

| Age (%) | 18~54 | 593 (47.7) | 578 (46.5) | 0.320 |

| 55~64 | 275 (22.1) | 313 (25.2) | ||

| 65~74 | 267 (21.5) | 255 (20.5) | ||

| Over 75 | 109 (8.8) | 98 (7.9) | ||

| Hypertension (%) | Yes | 381 (30.6) | 392 (31.5) | 0.665 |

| No | 863 (69.4) | 852 (68.5) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | Yes | 153 (12.3) | 154 (12.4) | 1.000 |

| No | 1091 (87.7) | 1090 (87.6) | ||

| Obstructive sleep apnea (%) | Yes | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 1.000 |

| No | 1242 (99.8) | 1241 (99.8) | ||

| Hypothyroidism (%) | Yes | 3 (0.2) | 7 (0.6) | 0.342 |

| No | 1241 (99.8) | 1237 (99.4) | ||

| Congestive heart failure (%) | Yes | 52 (4.2) | 52 (4.2) | 1.000 |

| No | 1192 (95.8) | 1192 (95.8) | ||

| Prior stroke or TIA or thromboembolism (%) | No | 1244 (100.0) | 1244 (100.0) | NA |

| Vascular disease (%) | Yes | 52 (4.2) | 52 (4.2) | 1.000 |

| CCI score (mean (SD)) | 1.66 (2.19) | 1.67 (2.04) | 0.902 | |

| CHA | 1.89 (1.73) | 1.85 (1.67) | 0.563 | |

| ACHD (%) | ASD | 855 (68.7) | 841 (67.6) | 0.576 |

| VSD | 437 (35.1) | 411 (33.0) | 0.290 | |

| TOF | 56 (4.5) | 46 (3.7) | 0.363 | |

| Others | 157 (12.6) | 184 (14.8) | 0.130 | |

| 415 (33.4) | 421 (33.8) | 0.832 | ||

ACHD, adults with congenital heart disease; AF, atrial fibrillation; ASD, atrial septal defect; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CHA

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Incidence of ischemic strokes in adults with congenital heart disease with and without atrial fibrillation (Afib) in the overall population and the population aged

| ACHD | AF ACHD (n/N) | Non-AF ACHD (n/N) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p value |

| Overall | 129/1246 | 80/1246 | 1.45 (1.10, 1.92) | 0.0093 |

| Excluding mechanical valve replacement surgery | 106/1055 | 52/1055 | 1.82 (1.31, 2.54) | 0.0004 |

| Age | 35/478 | 18/509 | 1.46 (0.81, 2.63) | 0.2071 |

ACHD, adults with congenital heart disease; Adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio for age and sex; AF, atrial fibrillation; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CI, confidence interval; n, number of participants with stroke; N, total number of participants.

In ACHDs aged

Among ACHDs with AF, the subgroups of ASD, VSD, TOF, and other CHDs demonstrated 1.57, 1.29, 2.29, and 1.66 times higher risk of ischemic stroke, respectively, compared to the corresponding subgroups in the non-AF group (Table 3, Fig. 3). Although the trend remains consistent, statistically significant ischemic stroke risk was observed only in the ASD subgroup with AF, even in individuals under the age of 50 (adjusted HR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.11–2.21, p = 0.0097) (Table 3, Fig. 3).

| Type of ACHD | AF ACHD (n/N) | non-AF ACHD (n/N) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p value |

| ASD | 91/855 | 52/841 | 1.57 (1.11, 2.21) | 0.0097 |

| VSD | 39/437 | 24/411 | 1.29 (0.77, 2.15) | 0.3280 |

| TOF | 3/56 | 1/46 | 2.29 (0.20, 26.14) | 0.5056 |

| Others | 22/157 | 15/184 | 1.66 (0.86, 3.22) | 0.1296 |

| 48/415 | 27/421 | 1.62 (1.01, 2.60) | 0.0457 |

ACHD, adults with congenital heart disease; Adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio for age and sex; AF, atrial fibrillation; ASD, ostium or secundum type atrial septal defect; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CI, confidence interval; n, the number of subjects with stroke; N, the total number of subjects; TOF, teratology of Fallot; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Incidence of ischemic strokes in the population with atrial septal defect (ASD) and ventricular septal defect (VSD). (A) Overall ischemic stroke incidence (Left: ASD; Right: VSD). (B) ischemic stroke incidence in the ASD population aged

Mixed type CHD is defined as the presence of two or more diagnosis CHD subtypes in a patient, and the ratio of this mixed type CHD is approximately 33% of the overall ACHD population (Table 1). Patients with mixed type CHD with AF had higher ischemic stroke risks than patients with mixed type CHD without AF (HR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.01–2.6, p = 0.0457; Table 3).

After the exclusion of patients who underwent antiplatelet therapy (in the original cohort before propensity score matching), patients with AF were divided into two subgroups according to the CHA

| ACHD without warfarin | ACHD with warfarin | Total | |||||||

| CHA₂DS₂-VASc scoring | Number | Ischemic stroke incidence | Estimated year-risk % | Number | Ischemic stroke incidence | Estimated year-risk % | Number | Ischemic stroke incidence | Estimated year-risk % |

| 0&1 | 460 | 32 | 1.17 | 189 | 24 | 2.22 | 649 | 56 | 1.47 |

| 2+ | 433 | 47 | 2.56 | 157 | 26 | 4.69 | 590 | 73 | 3.06 |

| Overall | 893 | 79 | 1.73 | 346 | 50 | 3.06 | 1239 | 129 | 2.08 |

ACHD, adults with congenital heart disease. CHA

*Patients with antiplatelet therapy usage were excluded from the analysis.

Our study showed that ACHDs (regardless of their sex or age) had a high prevalence of AF, particularly young women. However, the results of the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study were different, wherein AF prevalence was 0.95% (95% CI, 0.94%–0.96%), and it was more common in men than in women (1.1% vs. 0.8%; p

Furthermore, among ACHDs, patients with AF have a higher ischemic stroke risk than those without AF. The Framingham study in 1991 demonstrated that AF is an independent risk factor for stroke in the general population [14]. Although the mechanism is unclear, ACHDs have some unique risk factors that are suspected to be associated with thromboembolic events, such as cyanosis, Fontan circulation, intracardiac shunt, and heart defect complexity [27]. Thus, thromboembolic risk in ACHDs might be underestimated. In the current study, among ACHDs, those with AF had nearly 1.5 times higher risk of ischemic stroke than those without AF. This trend was the same in the younger population (age

Previous data on ACHDs from Asia and Europe showed that the overall stroke incidence was higher in ACHDs than in the general population, but details regarding stroke subtypes were limited [15, 28]. In this study, the overall ACHDs with AF as well as ASD, mixed type CHD subgroups showed a significantly increased risk of ischemic stroke. Importantly, in the young population (age

Previous attempts to use the CHA

This study has several limitations. First, information on many risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, metabolic syndrome, ventricular function, and severe valvular disease, was unavailable in the claims database, which may confound the results. Additionally, information on the International Normalized Ratio (INR) level and medical compliance of warfarin usage were unavailable in the database. Second, it is known that a patent foramen ovale (PFO) can increase the risk of ischemic stroke. However, the ICD-code based diagnosis cannot differentiate between ASD and PFO. To overcome this limitation and identify patients with ACHD in our study, we used the Registry for Catastrophic Illness database, a sub-dataset of the Taiwanese NHIRD that includes detailed clinical information and requires expert audited approval with formal medical echocardiography or cardiac catheterization reports. Using this rigorous criterion, we are confident that simple PFO cases were not classified as ACHD in our study. Third, detailed AF subtypes could not be validated from this cohort due to the limitations of the database. Moreover, information on the complexity and clinical functional status of CHD subtypes was limited. Fourth, it is important to acknowledge that this study has a retrospective observational design, which introduces the possibility of confounding factors influencing the outcomes of anticoagulation therapy. Despite the significantly high risk of ischemic stroke observed in ACHD patients with AF, as evidenced by the data presented in Table 4, it is likely that clinical and ethical biases have influenced the lack of protective effect observed with warfarin treatment. It should be noted that the decision to use warfarin in Taiwan is based on physician judgment, and this can be a challenging task given the higher propensity for bleeding and substantial fluctuations in therapeutic plasma levels among the Asian population. Close monitoring of anticoagulation therapy is crucial, especially in young populations [29]. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that the time spent within the therapeutic International Normalized Ratio (TTR) range is lower in Taiwan compared to other countries, even when considering data from randomized controlled trials such as RE-LY and ROCKET-AF [30, 31]. Furthermore, the baseline characteristics between the warfarin and non-warfarin groups were not balanced due to the limitation of small event numbers, which may have influenced the observed protective effect of warfarin. These findings raise questions about the potential benefits of anticoagulant therapy with warfarin in the ACHD population in Asia, specifically in Taiwan, and highlight the need for further prospective studies to address this issue. Additionally, in Taiwan, reimbursement policies do not allow the prescription of novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) for stroke primary prevention in young adults with congenital heart disease (ACHDs) and atrial fibrillation. In 2020, a systematic review of the literature on NOAC use in ACHDs was conducted, and the results indicated that NOACs are safe and effective in ACHDs without mechanical prostheses [32]. Later, the international NOTE registry revealed that NOACs are safe and may be effective for thromboembolic prevention in adults with heterogeneous forms of congenital heart disease [33]. Further studies, such as the ongoing PROTECT AR (Apixaban in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease and Atrial Arrhythmias: the PROTECT-AR Study) trial, are necessary to confirm whether ACHDs with simple or complex diseases may benefit more from NOACs than from warfarin [34]. Finally, the study cohort sizes were small with few stroke events, but the number of ACHDs has been increasing in the past decade, and the management of clinically crucial issues such as AF and ischemic stroke in this population is important.

In summary, this study is the first to confirm the high prevalence of AF in Asian adults with congenital heart disease, which leads to an increased risk of ischemic stroke events. This risk is observed even at a young age (under 50 years old) or with a low CHA

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to ethical/privacy reasons. It could be applied followed Taiwan’s NHIRD policy.

Conception or design of the work: YSL, PHC. Data collection: YSL, PHC, YCH, YWK. Data analysis and interpretation: YSL, YCH, YWK, CPL, VCCW, HYC. Drafting the article: YSL, YCH, CPL, VCCW, HYC. Statistical analysis: YWK. Critical revision of the article: all authors. Final approval of the submitted version: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (IRB no. 201800169B1) and was performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The authors thank Chris Kao for assistance with statistical analysis. The authors also thank Ms. Ingrid Kuo and the Centre for Big Data Analytics and Statistics (Grant CLRPG3D0047) at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for creating the illustrations used herein.

Dr. Lin was supported by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan [grant numbers CMRPG5H0221, CMRPG5K0161]. Dr. Chu was supported by Taiwan’s National Science and Technology Council (NSC) 111-2314-B-182A-013-MY3.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Yu-Sheng Lin is serving as Guest Editor of this journal. We declare that Yu-Sheng Lin had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Boyoung Joung.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.