1 Department of Cardiology, State Key Laboratory of Complex Severe and Rare Diseases, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, 100730 Beijing, China

Abstract

Background: Patients may experience a decline in cardiac function even after successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). It is apparent that the assessment of left ventricular (LV) function before PCI is often overlooked. The purpose of this review is to explore the significance of LV function assessment before PCI by comparing the differences in short- and long-term PCI outcomes between patients with different LV ejection fraction (LVEF) stratified preoperatively. Methods: PubMed and Scopus were searched to identify potential studies from January 1, 2001 through January 1, 2022. Results: A total of 969,868 participants in 33 studies at different stratifications of baseline LVEF were included in this review and their PCI outcomes were stratified for analysis. The hazard ratio of all-cause mortality within 30 days, one year and greater than 1 year after PCI between patients with abnormal and normal LVEF were 2.96 [95% CI, 2.2, 3.98], 3.14 [95% CI, 1.64, 6.01] and 3.08 [95% CI, 2.6, 3.64]; moderately impaired LV function versus normal were 2.32 [95% CI, 1.85, 2.91], 2.04 [95% CI, 1.37, 3.03], 1.93 [95% CI, 1.54, 2.44]; poor LV function versus normal were 4.84 [95% CI, 3.83, 6.1], 4.48 [95% CI, 1.37, 14.68], 6.59 [95% CI, 4.23, 10.27]. Conclusions: A moderate or severe reduction in patients’ LVEF may have a serious impact on PCI prognosis. We strongly advocate for adequate assessment of LVEF before PCI as this will assist in choosing the optimal revascularization and postoperative treatment, thereby reducing short- and long-term mortality.

Keywords

- percutaneous coronary intervention

- left ventricular ejection fraction

- prognostic

Since percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was introduced in 1977 [1],

important advances have been made. Early and long-term outcomes of PCI have been

improved with the advent of lower profile balloons, bare-metal stent (BMS), drug

eluting stent (DES), improved guide-wire support, increased use of adjuvant drugs

and hemodynamic support devices. Recent studies have shown that increased use of

PCI reperfusion has led to a decrease in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) mortality.

In patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), primary PCI

can limit infarct size and preserve left ventricular (LV) systolic function [2, 3]. Despite being highly effective in reducing the need for repeat

revascularisation compared with BMS, early-generation DES were associated with an

increased risk of late (

PCI is a mature technology that is highly utilized in clinical practice. Lack of evaluation of the LV function before PCI may result in the failure to select the optimal revascularization protocol. In a 2021 network meta-analysis by Yujiro Yokoyama et al. [9], coronary-artery bypass grafting (CABG) remained the treatment of choice in patients with coronary artery disease and low LV ejection fraction (LVEF). Studies have shown that approximately one-third of patients who undergo PCI [10, 11, 12] suffered from LV dysfunction—an important predictor of post PCI death and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) [13, 14]. PCI does not improve or maintain cardiac function in all STEMI patients with data demonstrating that 4.7–8.6% of patients may experience a decline in cardiac function after successful primary PCI [15, 16]. Therefore, the stratification of LVEF risk assessment before PCI is particularly important but often overlooked. According to the audit of European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Intervention in the UK, only 46% of patients undergoing PCI had ever received LV classification [10]. According to the Mayo Clinic, information on LV function is available in only 60% cases [17] with the main reason being that PCI is increasingly performed in the setting of ACS that requires timely intervention [18, 19]. Comprehensive clinical assessment is sacrificed for the sake of expediency, resulting in insufficient time to assess LV function before PCI. Congestive heart failure (CHF) after STEMI PCI is the primary reason behind the increase in morbidity and mortality [20]. Patients at high risk for CHF need to be identified to select more appropriate post infarction therapies. We believe that LV assessment is helpful for patient risk stratification, even in the context of ACS. This ensures the preoperative awareness of the high-risk nature of the surgery and facilitates the proper revascularization [21].

This study aims to explore the significance of LV function assessment before PCI by comparing the differences in short- and long-term PCI outcomes between patients with different LVEF levels stratified preoperatively along with raising the importance of the evaluation of LVEF before PCI.

The protocol was registered on INPLASY (INPLASY202220031) and is available on inplasy.com (https://doi.org/10.37766/inplasy2022.2.0031). Our systematic review was consistent with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement [22].

PubMed and Scopus were searched to identify potential studies from January 1, 2001 through January 1, 2022 (Supplementary Method M1) There were no language restrictions. The reference list of previous systematic reviews [23, 24, 25, 26] was scrutinized.

We included observational studies or secondary analysis of intervention studies that reported prognosis of PCI. Outcomes of studies needed to be stratified according to LVEF. Two investigators performed title/abstract screening independently from each other. Following this, the full-text of potentially eligible studies was accessed by two investigators for determining eligibility and data extraction. Data evaluated included study design, age, gender, grouping rules, sample size, patients, country, follow-up periods, and study results. If the article did not provide data results, we used free software Engauge-digitizer (Version 12.1, Mark Mitchell, Baurzhan Muftakhidinov and Tobias Winchen et al.) [27] to obtain data from figures present [28]. We assessed study quality using items from the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) [29].

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality stratified according to LVEF at

baseline. The secondary outcomes were MACE and cardiac mortality in-hospital or

long-term. We conducted random-effects or fix-effects meta-analysis of outcomes

for which at least 2 studies contributed data. Categorical data were expressed as

the pooled odds ratio (OR) or Hazard ratio (HR) with their 95% CIs using the

inverse variance method. Heterogeneity was evaluated using both the

We analyzed three subgroups. (1) Patients with heart failure (New York Heart

Association or Killip class

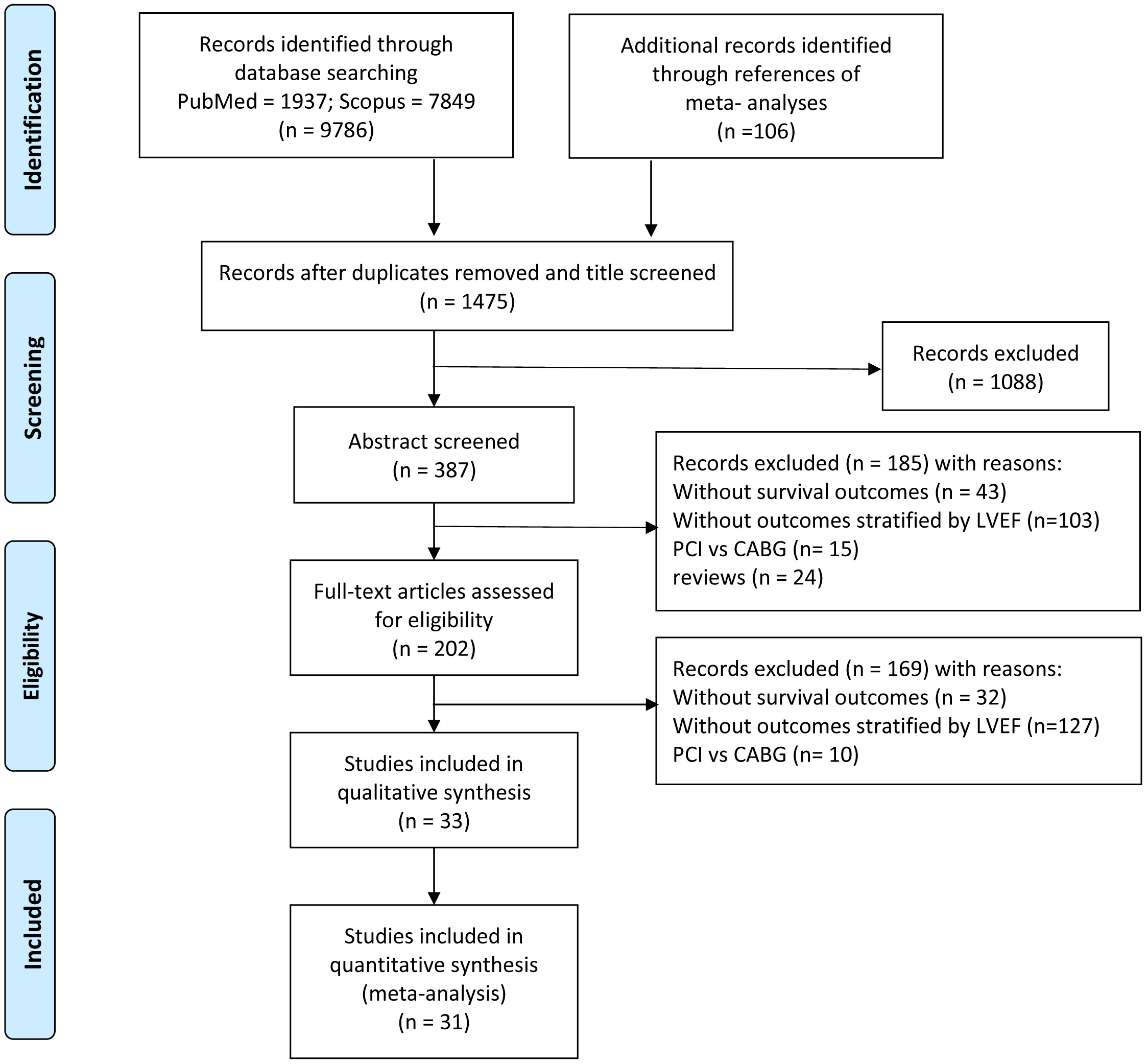

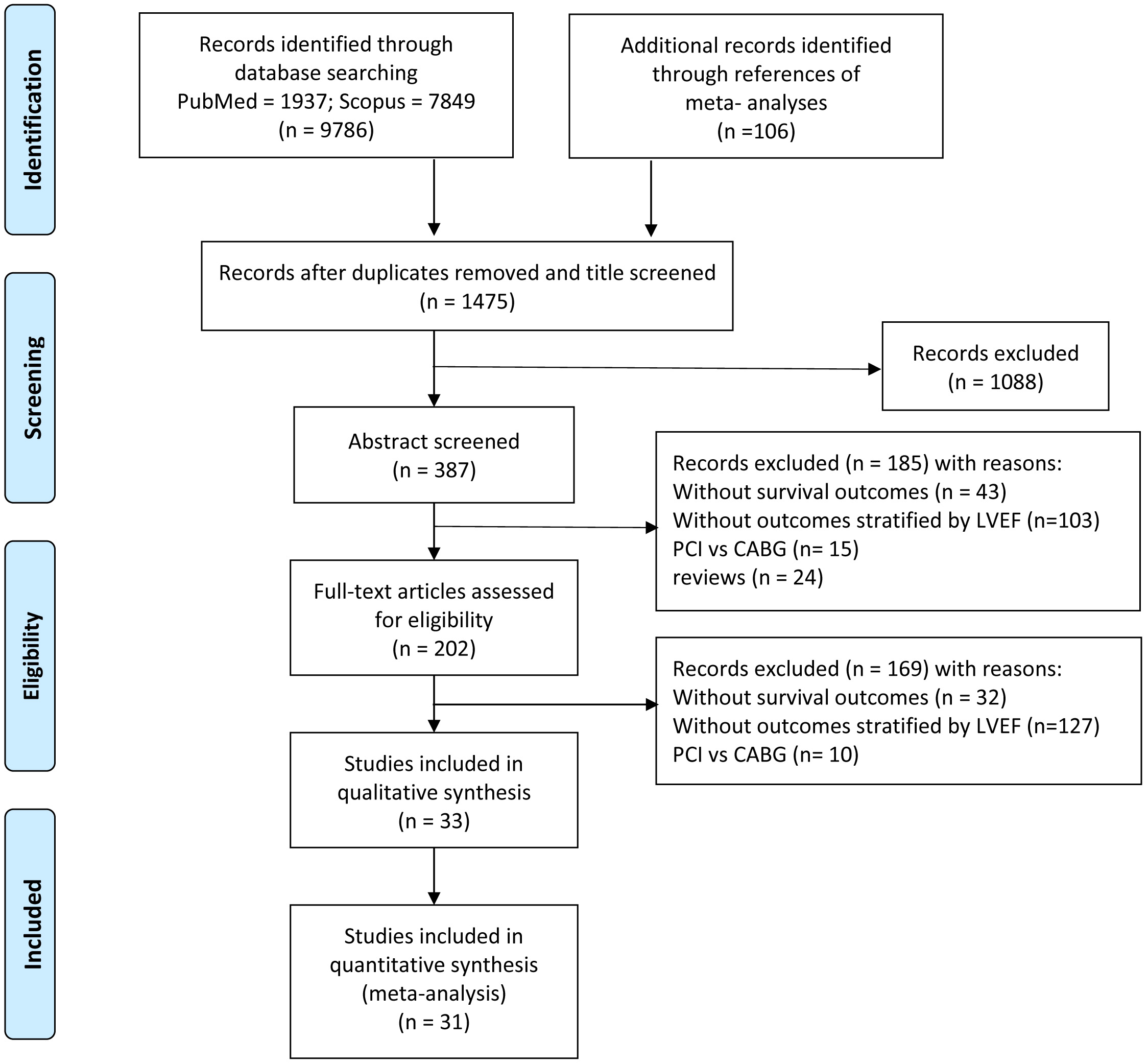

We identified 9786 studies by database searching and 106 additional articles by reference tracking, of which 33 met inclusion criteria with resultant 969,868 patients. The flowchart of the article search and selection process is demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Flowchart of study selection.

Of the 33 studies included, two were secondary analyses of randomized controlled trials [13] with the remaining 31 being observational studies (12 prospective and 19 retrospective). Participants in 6 studies [13, 14, 30, 31, 32, 33] were exclusively patients with STEMI, in 3 studies [34, 35, 36] participants were exclusively patients with CTO, and 3 studies [31, 37, 38] were patients with baseline heart failure. Thirteen studies [11, 30, 31, 32, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45] reported the prognostic outcomes during hospitalization, 14 studies [14, 33, 34, 35, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55] reported the prognostic outcomes for greater than or equal to one year, and 6 studies [10, 13, 36, 56, 57, 58] reported the prognostic outcomes in both short and long term. The characteristics of the included studies are detailed (Table 1, Ref. [10, 11, 13, 14, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58]). The average NOS score of all included studies was 7.6 points, with 2 studies having a minimum score of 5 [32, 34] and 3 studies having score of 6 [30, 40, 43] (Supplementary Table 1). Five studies [30, 32, 34, 40, 43] were of low quality because they had too small sample sizes to be representative of the average level of the community, and confounders were not well controlled during the compassrison process, resulting in low comparability.

| Study | Year | Study design | Age | Male | stratified LVEF% | Sample size | Patients | Country | Follow up |

| Alidoosti [46] | 2008 | Prospective Observational | 56.1 | 69.0% | 2030 | Patients with low, intermediate and high ejection fraction | Iran | long-term | |

| Banga [30] | 2019 | Retrospective Observational | 61.8 (12.9) | 74.3% | 249 | Patients with STEMI treated with primary PCI | USA | in-hospital | |

| Daneault [13] | 2013 | Secondary analysis of open-label, randomized trial | 60.3 (54.6–72.3) | 69.3% | 2430 | Patients with STEMI treated with primary PCI | USA | 3-year | |

| Doshi [31] | 2019 | Retrospective Observational | 65.6 (13.4) | 65.0% | 31,180 | hospitalisations undergoing STEMI-PCI | USA | in-hospital | |

| El Awady [34] | 2020 | Prospective Observational | 61.1 (8.2) | 76.0% | 75 | patients undergoing CTO PCI | Egypt | 6 months | |

| Galassi [35] | 2017 | Prospective Observational | 839 | patients undergoing elective PCI of CTOs | Italy | 6 months | |||

| Holper [47] | 2006 | Prospective Observational | 69.2 | 54.5% | 4697 | patients undergoing PCI | USA | 1 year | |

| Jiang [48] | 2017 | Prospective Observational | 10,490 | patients undergoing PCI | China | 2 year | |||

| Jiang [37] | 2019 | Retrospective Observational | 68.6 (12.1) | 69.8% | 1270 | hospitalised patients with AMI undergoing emergency PCI | China | in-hospital | |

| Marui [49] | 2014 | Prospective Observational | 69.7 (9.7) | 1432 | patients undergoing first myocardial revascularization | Japan | 5 years | ||

| Sardi [56] | 2012 | Retrospective Observational | 68.6 (11.7) | 75.8% | 5337 | patients undergoing PCI | USA | 1 year | |

| Shiga [50] | 2009 | Prospective Observational | 66 (12) | 73.7% | 4122 | patients with AMI, who were discharged alive | Japan | 5 years | |

| Son [51] | 2016 | Retrospective Observational | 66.8% | 319 | patients who underwent successful PCI | Korea | 1 year | ||

| Sutton [52] | 2016 | Retrospective Observational | 78 (71–84) | 57.3% | 82,558 | patients who underwent successful PCI | USA | 1 year | |

| Toma [36] | 2017 | Prospective Observational | 66 (11) | 87.0% | 2002 | patients undergoing elective CTO PCI | Germany | 2 years | |

| Vakili [32] | 2014 | Prospective Observational | 63.5 (12.6) | 65.2% | 401 | patients with STEMI who underwent primary angioplasty | Iran | in-hospital | |

| Wang [38] | 2017 | Prospective Observational | 64.20 |

79.2% | 1647 | patients who had HF, and undergoing PCI/CAG | in-hospital | ||

| Ye [39] | 2018 | Retrospective Observational | 62.18 (10.31) | 69.9% | 1600 | patients who have undergone PCI | China | in-hospital | |

| Zhong [53] | 2020 | Prospective Observational | 63.69 (8.10) | 87.5% | 301 | patients who underwent successful PCI | China | 1 year | |

| Alaswad [40] | 2018 | Retrospective Observational | 69.57 (11.29) | 75.3% | 891 | patients undergoing PCI | USA | in-hospital | |

| Biondi-Zoccai [57] | 2011 | Retrospective Observational | 74.2 (9.2) | 76.1% | 975 | patients undergoing PCI | Italy | median of 18.2 months | |

| De Silva [10] | 2012 | Retrospective Observational | 65.7 (57.4–73.4) | 73.7% | 2328 | patients undergoing PCI | UK | long-term | |

| Gao [58] | 2013 | Prospective Observational | 59.9 (11.1) | 83.2% | 4335 | patients undergoing PCI | China | 36 months | |

| Halkin [54] | 2005 | Retrospective Observational | 62 (53–71) | 72.9% | 1620 | AMI | USA | 1 year | |

| Jackson [41] | 2018 | Retrospective Observational | 68 (12) | 77.0% | 260,726 | patients who received PCI | UK | 1 month | |

| Keelan [11] | 2003 | Retrospective Observational | 72.3% | 1158 | patients who underwent PCI | USA | in-hospital | ||

| Kwok [42] | 2015 | Retrospective Observational | 73.5% | 246,840 | patients who received PCI | UK | 30 days | ||

| Levi [55] | 2016 | Retrospective Observational | 72 (12) | 73.0% | 974 | patients who underwent an elective PCI | Israel | 5 years | |

| Mamas [14] | 2014 | Retrospective Observational | 68.5 (68.3–68.6) | 77.4% | 230,464 | patients undergoing PCI for elective STEMI and non-STEMI | UK | 5 years | |

| Marsico [43] | 2003 | Retrospective Observational | 67 (27–89) | 79.2% | 2488 | patients who underwent PTCA | Italy | in-hospital | |

| Singh [44] | 2007 | Retrospective Observational | 66.9 (12.1) | 69.0% | 7457 | patients who underwent PCI | USA | in-hospital | |

| van der Vleuten [33] | 2008 | secondary analysis of two randomized controlled trials | 59.8 (12.0) | 77.8% | 924 | patients with STEMI treated with PCI | Israel | 2.5 years | |

| Wallace [45] | 2009 | Retrospective Observational | 63.8 (11.7) | 67.5% | 55,709 | patients who underwent PCI | USA | in-hospital | |

| Studies | 33 | 969,868 | |||||||

| AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CTO, chronic total occlusion; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PTCA, Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction. | |||||||||

Normal LVEF is defined as LVEF

The hazard ratios of all-cause mortality within 30 days (or in-hospital), in one year and over a period more than 1 year after PCI between patients with abnormal and normal LVEF were 2.96 [95% CI, 2.2, 3.98], 3.14 [95% CI, 1.64, 6.01] and 3.08 [95% CI, 2.6, 3.64]. The hazard ratios of all-cause mortality within 30 days (or in-hospital), in one year and over a period more than 1 year after PCI between patients with moderately impaired LV function and patients with normal LVEF were 2.32 [95% CI, 1.85, 2.91], 2.04 [95% CI, 1.37, 3.03], 1.93 [95% CI, 1.54, 2.44]. The hazard ratios of all-cause mortality within 30 days (or in-hospital), in one year and over a period more than 1 year after PCI between patients with poor LV function and patients with normal LVEF were 4.84 [95% CI, 3.83, 6.1], 4.48 [95% CI, 1.37, 14.68], 6.59 [95% CI, 4.23, 10.27] (Table 1, Supplementary Figs. 1–9). The above comparisons suggested that the poorer baseline LV function was a major source for all-cause PCI mortality.

The odds ratios of MACE occurrence within 30 days (or in-hospital), in 1 year and over a period greater than 1 year after PCI between patients with abnormal and normal LVEF were 1.9 [95% CI, 1.65, 2.2], 1.71 [95% CI, 1.13, 2.59], and 1.37 [95% CI, 1.14, 1.65]. The odds ratios of MACE occurrence within 30 days (or in-hospital), in 1 year and over a long-term of period greater than 1 year after PCI between patients with moderately impaired LV function and patients with normal LVEF were 1.35 [95% CI, 1.27, 1.43], 1.194 [95% CI, 0.96, 1.48], and 1.15 [95% CI, 0.879, 1.52]. The odds ratios of MACE occurrence within 30 days (or in-hospital), in 1 year and over a period greater than 1 year after PCI between patients with poor LV function and patients with normal LVEF were 2.41 [95% CI, 2.04, 2.85], 1.47 [95% CI, 1.03, 2.081], and 2.31 [95% CI, 1.46, 3.66] (Table 2, Supplementary Figs. 10–18). The above comparisons suggest that the risk of MACE occurrence in 1 year or over a period greater than 1 year after PCI in patients with modestly impaired LV function was not different from that in patients with normal LVEF, but was greater in patients with poor baseline LV function than that in patients with normal LVEF.

| Outcomes | Comparisons (stratified according to LVEF at baseline) | Follow-up | HR [95% CI] | p-value | I² | Studies | Samples |

| All-cause mortality | abnormal vs normal | 30-day | 2.96 [2.2, 3.98] | 0.000 | 96.3% | 13 | 813,975 |

| All-cause mortality | abnormal vs normal | 1-year | 3.14 [1.64, 6.01] | 0.000 | 99.7% | 8 | 324,723 |

| All-cause mortality | abnormal vs normal | long-term | 3.08 [2.6, 3.64] | 0.000 | 88.5% | 7 | 237,097 |

| All-cause mortality | moderate vs normal | 30-day | 2.32 [1.85, 2.91] | 0.000 | 80.8% | 9 | 807,277 |

| All-cause mortality | moderate vs normal | 1-year | 2.04 [1.37, 3.03] | 0.000 | 98.1% | 7 | 320,026 |

| All-cause mortality | moderate vs normal | long-term | 1.93 [1.54, 2.44] | 0.000 | 89.1% | 5 | 235,665 |

| All-cause mortality | poor vs normal | 30-day | 4.84 [3.83, 6.1] | 0.000 | 77.8% | 7 | 797,443 |

| All-cause mortality | poor vs normal | 1-year | 4.48 [1.37, 14.68] | 0.000 | 99.8% | 5 | 317,248 |

| All-cause mortality | poor vs normal | long-term | 6.59 [4.23, 10.27] | 0.000 | 96.7% | 5 | 235,665 |

| MACE | abnormal vs normal | 30-day | 1.9 [1.65, 2.2] | 0.000 | 76.3% | 7 | 521,584 |

| MACE | abnormal vs normal | 1-year | 1.71 [1.13, 2.59] | 0.011 | 61.2% | 3 | 6477 |

| MACE | abnormal vs normal | long-term | 1.37 [1.14, 1.65] | 0.001 | 0.0% | 4 | 14,334 |

| MACE | moderate vs normal | 30-day | 1.35 [1.27, 1.43] | 0.000 | 2.3% | 4 | 515,998 |

| MACE | moderate vs normal | 1-year | 1.19 [0.96, 1.48] | 0.107 | 0.0% | 2 | 6176 |

| MACE | moderate vs normal | long-term | 1.15 [0.87, 1.52] | 0.329 | 0.0% | 3 | 3844 |

| MACE | poor vs normal | 30-day | 2.41 [2.04, 2.85] | 0.000 | 61.3% | 4 | 515,998 |

| MACE | poor vs normal | 1-year | 1.46 [1.03, 2.08] | 0.036 | 0.0% | 2 | 6176 |

| MACE | poor vs normal | long-term | 2.31 [1.46, 3.66] | 0.000 | 0.0% | 2 | 1814 |

| Cardiac death | 30-day | 7.54 [2.7, 21.06] | 0.000 | 56.1% | 2 | 6765 | |

| Cardiac death | 1-year | 4.51 [1.96, 10.38] | 0.000 | 0.0% | 2 | 8457 | |

| Cardiac death | long-term | 6.51 [4.25, 9.97] | 0.000 | 51.2% | 3 | 10,887 | |

| CTO-Death | abnormal vs normal | all | 3.3 [2.53, 4.29] | 0.000 | 0.0% | 2 | 2841 |

| CTO-MACE | abnormal vs normal | all | 1.6 [1.34, 1.9] | 0.000 | 0.0% | 3 | 2916 |

| STEMI-Death | abnormal vs normal | 30-day | 4.36 [1.52, 12.5] | 0.000 | 96.9% | 4 | 264,475 |

| STEMI-Death | abnormal vs normal | 1-year | 5.22 [3.87, 7.04] | 0.000 | 92.8% | 3 | 233,818 |

| STEMI-Death | abnormal vs normal | long-term | 3.83 [3.35, 4.37] | 0.000 | 82.7% | 3 | 233,818 |

| STEMI-MACE | abnormal vs normal | 30-day | 3.78 [2.54, 5.64] | 0.000 | 0.0% | 2 | 2679 |

| HF-Death | HFrEF vs HFpEF | 30-day | 1.36 [1.15, 1.6] | 0.000 | 0.0% | 3 | 34,097 |

| CTO, chronic total occlusion; HF, heart failure; HFrEF, HF with reduced ejection

fraction; HFpEF, HF with preserved ejection fraction; HR, Hazard ratio; LVEF,

left ventricular ejection fraction; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; STEMI,

ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Bold italics mean no statistical significance. | |||||||

Due to the paucity of study data, in this study the outcomes were pooled based

on a cutoff value of 40% for the baseline LVEF. The hazard ratios of

cardiovascular mortality within 30 days, in 1 year and over a period greater than

1 year after PCI between patients with baseline LVEF

Among patients undergoing elective CTO PCI, patients with abnormal LVEF had significantly higher all-cause mortality than that of patients with normal LVEF, HR = 3.30 [95% CI, 2.53, 4.29], and the incidence of MACE was significantly increased, OR = 1.60 [95% CI, 1.34, 1.90]. Among patients undergoing STEMI PCI, patients with abnormal LVEF had significantly higher 30-day, 1-year, and long-term all-cause mortality compared to patients with normal LVEF, with HR = 4.36 [95% CI, 1.52, 12.5], 5.22 [95% CI, 3.87, 7.04], and 3.83 [95% CI, 3.35, 4.37]. Compared with HFpEF, patients with HFrEF undergoing PCI were significantly noted to have an increased all-cause mortality, HR = 1.36 [95% CI, 1.14, 1.60] (Table 2, Supplementary Figs. 22–28).

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and asymmetry of the funnel plot was evaluated with the Egger regression test for implementation strategies with at least 10 studies. We found publication bias in the comparison of 30-day all-cause mortality in patients with abnormal versus normal LVEF (Supplementary Fig. 29).

A total of 969,868 participants in 33 studies [10, 11, 13, 14, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58] at different stratification of baseline LVEF were included in this study and their PCI outcomes were stratified for analysis. This study found that lower baseline LVEF was associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality after PCI. Patients with a moderate level of LVEF had a 2.32-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality within 30 days and a 1.93-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality over 1 year compared with patients with a normal LVEF. Compared with patients with normal LVEF, the HR of 30-day all-cause mortality was 4.84 and the HR of over 1-year all-cause mortality was 6.59 in patients with poor LVEF. We also investigated cardiovascular mortality in patients with LVEF below 40%. Our study demonstrated that patients with LVEF below 40% had 7.54 times higher 30-day cardiovascular mortality and 6.54 times higher cardiovascular mortality over 1 year compared with patients with LVEF above 40%. This data supports that reduced LVEF is an important contributing factor to the prognosis of all-cause mortality, especially to cardiovascular death after PCI.

Studies have suggested that our findings may be related to the following

reasons: (1) patients with reduced LV function are mostly elderly diabetic

patients with a history of acute myocardial infarction and a higher possibility

of cardiogenic shock; (2) with the decrease of LV function, the shear forces in

the stented segment decreases, increasing the possibility of thrombosis [59, 60];

(3) with the decline of cardiac function, the incidence of renal insufficiency,

which is a known risk factor for stent thrombosis, increases. In view of this,

adequate preoperative evaluation of LVEF and the pursuit of optimal

revascularization may be of great significance for the outcomes of these

patients. Some guidelines recommend CABG as a revascularization strategy for

patients with poor ejection fraction. The European Society Of Cardiology

Guidelines indicate that CABG is superior to PCI, whereas the US guidelines only

recommend CABG and have no comment on PCI [61, 62]. CABG is more likely to

achieve complete revascularization than PCI [63]. Full revascularization can more

effectively reduce the burden of myocardial ischemia, thereby reducing the risk

of both sudden death and cardiac death. Moreover, CABG is better for blood supply

in the distal vascular bed with full revascularization achieved after CABG

resulting in better outcomes to patients [64]. However, PCI is still widely used

due to its operational ease and patients’ own choice. Especially in the context

of ACS, evaluation of LVEF before PCI becomes even more important when clinicians

are challenged to complete surgery within 72 [18] or 48 hours [19]. Understanding

LV dysfunction can provide insight into the possible complexity of the intended

PCI, thus providing a basis for preoperative preparation and medical optimization

of patients. Meanwhile, this ensures that all team members understand the

high-risk nature of the case before starting the procedure, and deploy

percutaneous LV assist device in advance, such as axial flow pumpor intra-aortic

balloon counter-pulsation. Moreover, identifying high-risk patients facilitates

postoperative care, understanding postoperative changes in LVEF, and increases

the use of more appropriate postinfarction therapies, such as optimal doses of

angiotensin receptor blockers, aldosterone antagonists, or angiotensin converting

enzyme inhibitors [65, 66]. The ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines advise that all

patients with STEMI undergo a systematic echocardiographic assessment to assess

LV function before discharge from the hospital. For patients with LVEF

Our subgroup analysis of CTO PCI patients suggests that CTO patients with abnormal LVEF have a 3.3-fold increased risk of mortality and a 1.6-fold increased risk of MACE compared with CTO patients with normal LVEF. PCI may provide significant clinical benefit for CTO [69]. Although the applicability of CTO PCI to symptomatic patients has been generally accepted by guidelines and consensus [70], CTO PCI has another important potential benefit, that is improved LV function. Preoperative assessment of LVEF is necessary to assess the improvement in LV function. According to Galassi et al. [35] and Tajstra et al. [71], a higher prevalence of peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes mellitus in patients with CTO and low LVEF significantly increases the surgical risk. Preoperative LVEF assessment is critical to identify high-risk patients who are to undergo CTO PCI. CTO PCI is a relatively complex procedure, and blocking side branches during CTO PCI is associated with a high risk of coronary perforation and perforation tamponade [72] as well as periprocedural myocardial infarction [73, 74]. The use of the antegrade crossing techniques in CTO recanalization may be preferable because the retrograde crossing techniques have been associated with a high risk of procedural complications [74, 75] and surgical perioperative myocardial infarction. However, preservation of bifurcations and recanalization of complex CTOs often require retrograde techniques [76, 77]. CTO PCI relies heavily on operator experience, so preoperative LVEF evaluation is necessary to fully understand the patient’s condition and the difficulty of operation.

Our subgroup analysis of HF patients showed that the 30-day mortality in HFrEF patients was 1.36 times higher than that in HFpEF patients. Although the data volume is small, it can still be seen that HFrEF patients have a poor prognosis. Currently, there are no clear guidelines for the role of PCI in the treatment of HFrEF. Therefore, for HF patients, pre-PCI LVEF assessment is needed to identify HFrEF patients and select appropriate treatment strategies.

Our findings have some limitations. The stratification criteria of LVEF were not completely consistent across the included studies, and relatively broad criteria were used to classify LVEF into normal, moderate and poor levels, which may account for the higher heterogeneity (Table 2). The time span of our included studies was 20 years and during this time many advances have been made in PCI technology, which may also be one of the reasons for the high heterogeneity among studies in different years. Therefore, the effect sizes in the meta-analysis of all-cause mortality should be interpreted with caution. However, a random effects model has been used to minimize the bias associated with high heterogeneity.

Our study suggests that a moderate or severe reduction in patients’ LVEF may have a serious impact on PCI prognosis. Therefore, we strongly advocate for adequate assessment of LVEF before PCI (regardless of ACS) in order to choose the optimal revascularization and postoperative treatment resulting in reduced short- and long-term mortality.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome(s); BMS, bare-metal stent; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CHF, Congestive heart failure; CTO, chronic total occlusion; DES, drug eluting stent; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, HF with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, HF with reduced ejection fraction; HR, Hazard ratio; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale; OR, odds ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial.

MY—Writing - Original draft preparation. FG—Formal analysis. YY—Data curation, Validation. ZJ—Data curation, Validation. KS—Writing - Reviewing and Editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.