1 Department of Communications Engineering, University of the Basque Country, 48940 Bilbao, Spain

Abstract

Semantic web applications are witnessing a dramatic increase in complexity, data volume, and usage. Likewise, large language models (LLMs) are experiencing significant developments in performance and capabilities. Consequently, LLMs have been utilized in various fields and applications to support primary and secondary tasks. The proven ability of LLMs to process natural language (NL) has opened the door to integration into many tasks, including NL-related tasks such as Knowledge Graph Question Answering (KGQA), which involves translating NL questions into SPARQL queries to retrieve answers from Knowledge Graphs (KG). However, answering questions over domain-specific KGs is challenging due to complex schema structures, specialized vocabularies, and query complexity. Therefore, the development of domain-agnostic and user-friendly KG querying mechanisms has become necessary. Motivated by this need, this paper presents an LLM based approach for translating NL questions into SPARQL queries over domain-specific KG by investigating how various configurations of augmented KG data influence LLM responses. Our approach adopts a streamlined method for zero-shot SPARQL query generation by augmenting LLMs with different arrangements of previously extracted domain-specific KG information. Specifically, our experiments evaluate LLM generated SPARQL responses against twenty manually crafted questions of varying complexity using prompts augmented with different KG information: first, a reduced linearized KG, and second, discrete vocabulary information extracted from a reduced ontology KG. The results indicate that supplementing LLM prompts with discrete vocabulary information extracted from a reduced KG ontology yields competitive performance levels for the target LLM models compared to supplementing them with a reduced ontology. Ultimately, our approach reduces the augmented KG information size while preserving response accuracy, enables off-domain users to interact with domain-specific KG information and retrieve responses through a domain-agnostic interface, and facilitates benchmarking over a wide spectrum of LLM models.

Keywords

- large language models

- knowledge graphs

- SPARQL

- ontology

- natural language

- KGQA

The emergence of Large Language Models (LLM’s) and the advancement of their implementations in various scientific and applied fields have led the research community to utilize their capabilities to perform many tasks (Zhao et al, 2024; Chang et al, 2024; Tran et al, 2025). In particular, LLM is continually proving its substantive capabilities in analysing and understanding the semantics of Natural Language (NL) text (Min et al, 2023; Myers et al, 2024); consequently, it can offer semantic responses to questions posed in NL. This is due to the fact that LLMs have been extensively trained on massive and diverse datasets from different publicly available sources, allowing them to be used in many downstream text-based tasks more effectively (Myers et al, 2024). LLM’s capabilities in capturing linguistic nuances, general knowledge, and analysing patterns of unstructured text such as NL can be effectively employed in Knowledge Graph Question Answering (KGQA) tasks. As its name implies, KGQA is a task that aims to develop techniques capable of providing explicit or implicit factual answers to NL questions against Knowledge Graphs (KG). LLM can enforce and assist the KGQA task by translating unstructured NL questions into a structured formal query language required to retrieve answers from KGs (Karanikolas et al, 2023; Mishra et al, 2022).

KGs organize and structure factual information in a flexible and transparent manner, facilitating collaboration over cross-systems in various domains (Hogan et al, 2021; Khan, 2023; Yani and Krisnadhi, 2021). Interacting with and extracting information from KG requires deep and comprehensive experience and understanding of its structure, schema, vocabularies, and specialized query languages. Since most KGs represent their data and information using graph-based triples such as Resource Description Framework (RDF) (Beckett et al, 2014), accessing and retrieving information exhibited by triples requires syntax and semantic proficiency in a formal query language such as SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language (SPARQL) (Lan et al, 2021). However, creating queries using SPARQL is a cumbersome and challenging task even for experts due to its syntactic complexity and dependency on the underlying knowledge vocabulary, structure, and schema (Mishra et al, 2022; Kim and Cohen, 2013).

Minimizing the constraints of these challenges has provoked the need for an interface mechanism that can semantically translate an informal language (i.e., NL) to formal languages such as SPARQL. More specifically, this interface should have the ability to process queries expressed in NL as input and translated into a corresponding formal language, such as a SPARQL representation. Taking into consideration the capabilities of LLM and its excel in the processing and understanding of NL (Brown et al, 2020), LLM can be employed to integrate two different types of data structures and translate unstructured NL to a structured data format such as SPARQL (Pan et al, 2024).

Furthermore, publicly available KGs organize their information using conventional, frequently reused vocabulary and terminology to illustrate the representation of concepts and the relationships between them. Thus, public KGs and their internal node organization and interconnection exhibit many common characteristics in terms of context, vocabulary, and schema. In contrast, domain-specific KGs tend to be more complex with limited reusability due to their use of unique in-domain vocabulary and terminology for nodes and edges that reflect the knowledge domain (Diefenbach et al, 2018). As a consequence, seeking LLM assistance in generating NL-based SPARQL queries to retrieve information from domain-specific KGs can be complex, time-constrained and prone to logical errors compared to retrieving information from publicly available generic KGs (Gouidis et al, 2024; Zlatareva and Amin, 2021). This is because LLMs were trained primarily on diverse and publicly available data sets including generic KGs such as Wikidata and dbpedia, therefore, LLM can effectively generate SPARQL queries that answer generic questions based on previously seen data and vocabulary during their training phase while it struggles to generate correct SPARQL queries to answer questions related to domain-specific KGs (Taffa and Usbeck, 2023). To elucidate the issue at hand, a simple NL question such as “Give me a list of all the cities in Italy?” can be answered correctly after converting it to SPARQL in zero-shot mode using a language model such as ChatGPT. The same language model fails to answer domain-specific questions with similar questions simplicity as “Give me a list of all rail operational points in Italy?”. Although the SPARQL query generated by the LLM can be syntactically correct, the endpoint fails to generate the intended answer when the SPARQL query is executed against the domain-specific SPARQL endpoint. As explained earlier, the reason behind this is that LLMs are not familiar with the underlying ontology vocabulary and KG schema architecture of the domain-specific KG, thereby leading to selecting, inferring, or hallucinating incorrect subjects, predicates, or object identifiers. However, we generally observed three major limitations in leveraging LLMs to produce SPARQL queries over domain-specific KGs and ontologies that, if addressed, can significantly minimize the constraints of creating SPARQL queries.

First, LLMs cannot answer domain-specific questions because they lack structural insights, schema, and vocabulary of domain-specific KG. Their responses are based solely on previously seen training data, which may not include or reflect the specialized knowledge of the domain.

Second, according to (Naveed et al, 2025; Polat et al, 2025), the accuracy of LLM responses is highly dependent on the prompt and the information provided within its context. In our case, to prioritize generality and interoperability, the inclusion of domain-specific KG information is crucial to make LLM translate NL questions to SPARQL queries and generate accurate and correct responses (Pan et al, 2024). This leads to our first research question: What is the most effective format to augment knowledge graph (KG) information into the prompt to enable LLM to generate SPARQL queries that align with the user’s natural language question?

Third, although the quality, quantity, and arrangement of augmented KG information within the LLM prompt has a great effect on the generated responses, most LLMs are constrained by a limited input token size which, in return constrains the amount of augmented information within the context of the prompt (Mialon et al, 2023). This leads to our second research question: What strategies can be employed to condense and reduce the amount of augmented KG information to fit within the token window constrains of the LLM?

In this paper, we also investigate the ability of two LLM models to generate SPARQL queries from NL questions. Our approach is to generate prompts augmented with different arrangements of KG information, pass the prompt to LLM along with the NL input question to generate the intended SPARQL query, and retrieve answer from the SPARQL endpoint. The following summarizes the main contributions of this paper:

NL question answering over structured data has gained significant attention in recent years. These efforts led to the emergence of two dominant lines of research: Text-to-SQL translation for querying relational databases and Text-to-SPARQL translation for querying knowledge graphs and RDF data. Text-to-SQL research have made significant progress, providing valuable insights for NL to query translation tasks. However, the methods and approaches implemented introduces significant differences in assumptions and as well as challenges when compared to translating NL to SPARQL (Qin et al, 2022). Most of the approaches proposed are inherently dependent on tabular structure and format, which is ambiguous when applied to RDF-based knowledge graphs (Hong et al, 2025). Pourreza (2023) proposed an in context learning approach called DIN-SQL featuring automatic correction of the generated SQL query after generation, the approach proposed improves accuracy by breaking down complex queries into smaller parts, which is promising as an idea to be projected to SPARQL translation but still not transferable due to differences in query structure and triple path reasoning.

Contrary to SQL, SPARQL query generation depends on matching triple and property paths and patterns presented mostly presented as Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs), which are not considered in SQL models due to its tabular structure. Furthermore, SQL is inherently based on direct column mappings, while SPARQL often involves mapping heterogeneous ontologies and entity linking from different knowledge graphs, which limit their applicability to SPARQL translation tasks (Rony et al, 2022). Although text-to-SQL methods provide methodological inspiration, they lack the capacity to model semantics within ontology and KG, which are critical in SPARQL generation. As such, adapting these methods directly to SPARQL often yields suboptimal performance without significant modifications. This highlights the need for SPARQL-specific methods with domain-specific prompting, information augmentation approaches, and different knowledge representation.

In terms of translating NL to SPARQL Queries, a considerable number of studies have investigated the translation of NL questions to SPARQL queries without considering LLMs (Liang et al, 2021; Zlatareva and Amin, 2021). However, the expressiveness and ambiguity of NL led to the emergence of various input constraint approaches and methods to perform the translation task (Liang et al, 2021). With recent advances in LLMs taking into consideration its excel in semantic understanding of NL, many studies have leveraged the use of general LLMs to support the translation process at various locations within the process pipeline (Avila et al, 2024; Kovriguina et al, 2023; Meyer et al, 2023; Taffa and Usbeck, 2023). It is noticeable that most of the proposed methods and approaches proposed by researchers are evaluated against public KGs and their corresponding datasets, which are freely available within database repositories.

Kovriguina et al. (2023) designed a one-shot prompt-based template to instruct LLM to generate SPARQL from NL based on similar labelled examples extracted from three publicly available datasets, QALD-9, QALD-10 and Bestiary datasets. Another promising approach with high leaderboard scores on the QALD-9 is proposed by SGBT (Rony et al, 2022) which focuses on fine-tuning LLM to generate SPARQL from NL question. Kim and Cohen (2013) proposed an easy interface called LODQA based on semantic analysis of the NL question. The linguistic parser is employed to identify entities from the NLQ and create a pseudo-SPARQL query based on the linguistic analysis, then perform a URI lookup using OntoFinder against the KG to retrieve corresponding KG entities and substitute the pseudo-variables with the URI and finally generate a SPARQL representation of the NL question. Another LLM based approach is proposed by taffa (Taffa and Usbeck, 2023), proposing an approach that uses few shot LLM prompts with top-n labelled examples similar to the NL question to retrieve scholarly information from SciQA benchmark. Their approach is only effective when the top-n labeled examples match. Meyer et al. (2023) explored the potential of using ChatGPT to support related KG tasks, among these tasks is the generation of SPARQL from NL. The experiment was based on a self-created small KG and was therefore very limited. Lehmann et al. (2023) proposes using controlled NL as a middle step to answer the NL question over KGs using semantic parsing via LLMs, addressing the unambiguous translation of controlled NL into SPARQL queries. Avila et al. (2024) conducted similar experiments to evaluate how well ChatGPT can translate NL questions into SPARQL queries using a method called Auto-KGQAGPT, tested against a toy KG. The evaluation employed 15 NL questions with varying complexity. The method proposed separating both schema (T-Box) and data (A-Box) of the KG and selectively includes relevant fragements in the propmpt to reduce token size. The experiments were conducted using different versions of ChatGPT, including GPT-3.5 Turbo and GPT-4 Turbo, demonstrating the effectiveness of structured KG information input.

Moreover, the scarcity and limited access to labelled examples datasets to support LLMs in their translation process is also another issue. Prior to the emergence of Attention Mechanism, which is considered the building block of LLMs, Statistical Machine Learning approaches focus on training a Neural Network models on many NL labelled examples with their corresponding SPARQL queries producing results that depend on the quality, quantity and diversity of the labelled examples used to train the model. Many domain-specific KGs, such as industrial and medical KGs may not have enough data sets or information that can be used to support the process of translating NL into SPARQL quires or fine-tuning LLMs. Therefore, our work aims to facilitate the retrieval of information from domain-specific KG that uses in-domain vocabulary without any support of any curated data sets or labelled examples solely focusing on the ontology and vocabulary used within.

In conclusion, leveraging LLMs to translate NL into SPARQL queries has shown promising results. However, methods converting NL queries into SPARQL queries for domain-specific KGs that lack resources availability in terms of labelled datasets are needed. Therefore, our work is also motivated by the fact that there are limited attempts to study the capabilities of LLM to generate SPARQL queries targeting domain-specific KGs with minimal or no curated data sets.

This section describes our targeted KG ontology, experiment architecture, prompt design, and related experiment scenarios to investigate the capabilities of LLM to translate NL questions to SPARQL queries over domain-specific KG. All NL experiment competency questions sent to LLM with their corresponding SPARQL queries as well as the main Registers of Infrastructure (RINF) ontology, its reduced version, and the extracted RINF vocabulary can be found at the project GitHub repository as referred in the Availability of Data and Materials section.

Our proposed work uses the European Union Railway Agency (ERA) KG governed by the European Union Railway Agency as a Knowledge Base (KB). As part of ERA KG, which consists of many ontologies and graphs, we have used public data for the European Register of Infrastructure (RINF) ontology as a target KB. RINF facilitates access to all national railway infrastructure data and information records, covers and designates all concepts, classes, instances, and relationships related to the data of national registers and all vehicles that facilitate infrastructure (Rojas et al, 2021). Our experiment employed 20 NL competency questions formulated based on RINF KG to test targeted LLMs capability to answer diverse question complexity illustrated by simple queries: single triple, complex queries: multiple triples amd/or aggregation and filtering functions. Table 1 illustrates a sample of NL questions used in the experiment with their corresponding use justifications. The ‘No.’ column identifies the NL question sequence, the ‘NL Question’ corresponds to the actual input text of the NL question, and finally the ‘Justification’ explains the reason behind using each question. A complete list of NL competency questions including their corresponding SPARQL query translation can be found at the GitHub repository.

| No. | NL Question | Justification |

| Q1 | Please give me a list of all operational points. | Evaluating LLM based lookup task capability to map NL question to domain-specific class corresponding to the concept or class URI. |

| Q2 | Please give me a list of distinct train detection systems. | Evaluates LLM’s ability to handle pluralized concept references and apply a DISTINCT modifier in the query. This represents a simple aggregation and filtering task that tests concept resolution. |

| Q3 | Please give me a list of all national railway lines. | Evaluates LLM’s ability to recognize high-level domain classes with implicit terms. This is also a simple lookup query, but domain-specific terminology makes it more semantically demanding. |

| Q4 | Please give me a list of all national railway lines, Limit to 100 results. | Evaluates whether LLM can recognize and apply constraint as expressed in natural language question. This is a constrained retrieval task that combines class lookup with result bounding. |

| Q5 | Please give me a list of all national railway lines, return the name of the resource only, Limit to 100 results. | Combines multiple constraints: selecting a specific property (label/name), enforcing output size (Limit), and filtering the projection to a literal field. This is a constrained property projection query that tests precision in field selection and formatting. |

| Q6 | Please give me all operational points names and then filter results to find all operational points in Empoli. | Evaluates LLM’s handling of aggregated query with two steps: (1st) retrieve resource entity, and (2nd) apply a literal filter constraint based on a location (“Empoli”). This is a multi-triple query with filtering. |

NL, natural language; LLM, large language model; URI, Uniform Resource Identifier.

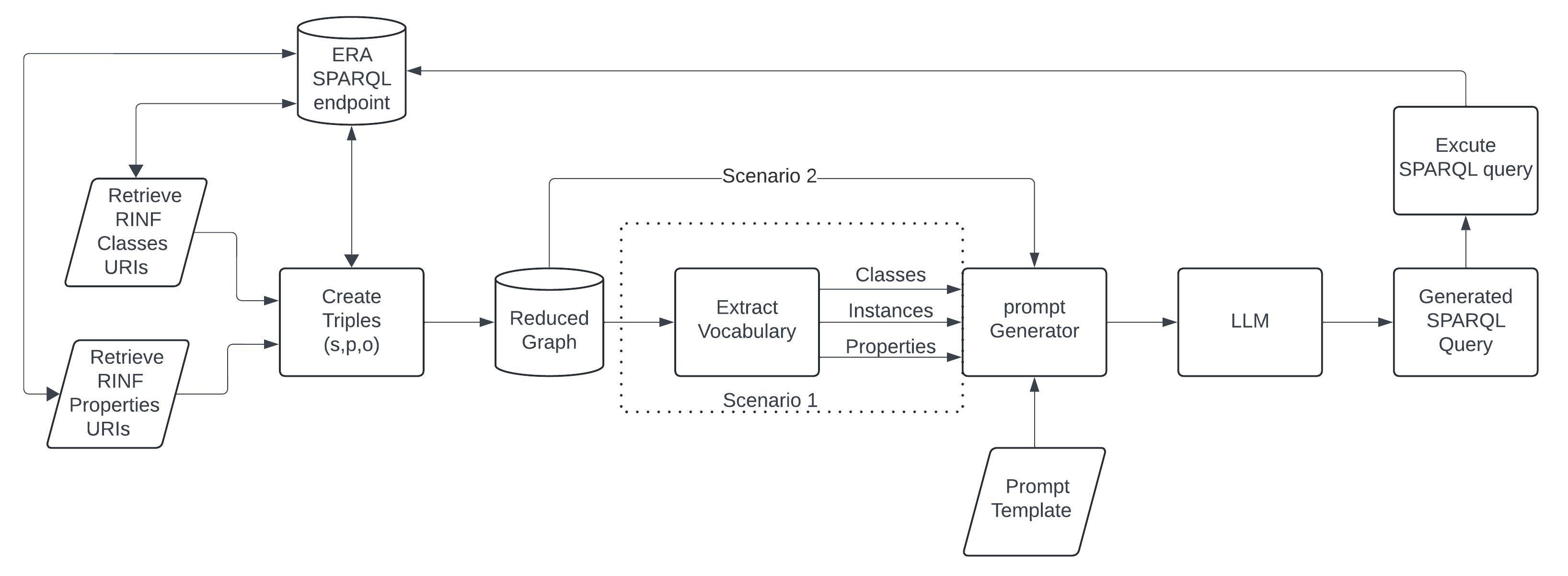

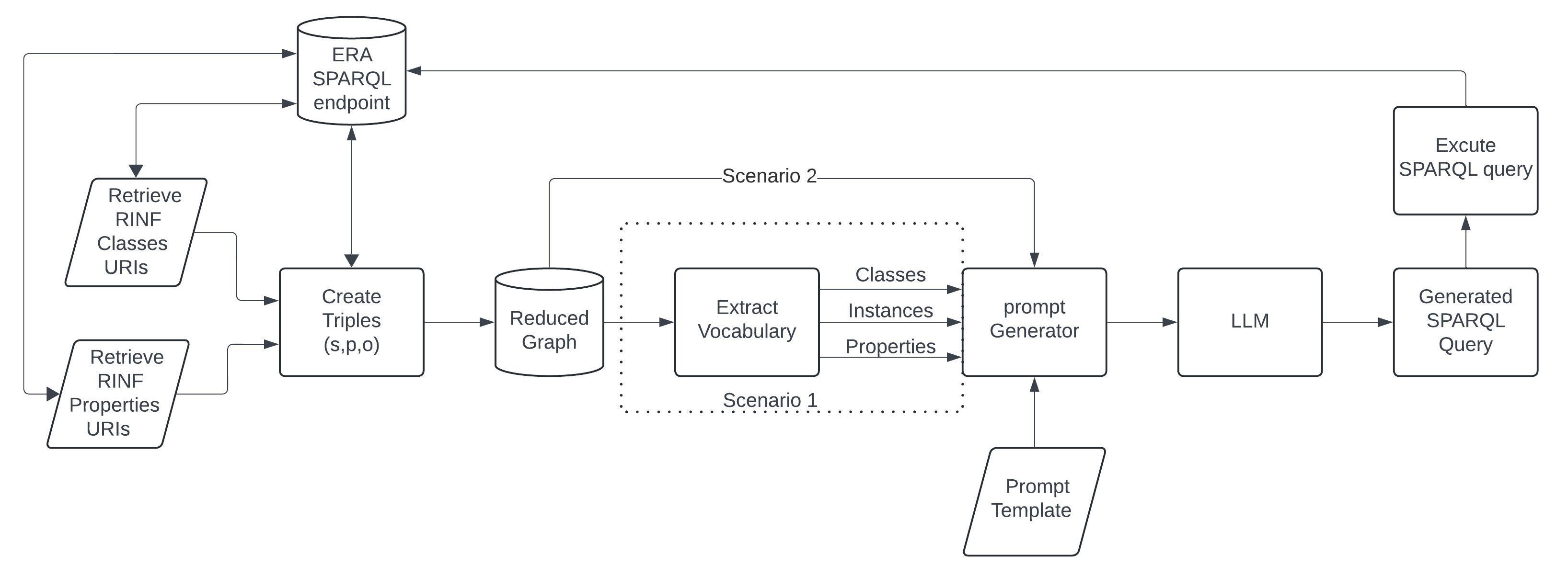

To investigate the capabilities of LLM to generate SPARQL queries and retrieve information from a domain-specific KG such as RINF based on the NL question, we conducted an experiment using two scenarios with three different prompt structures against two different LLM models without any prior NL processing and in an unadorned fashion. The main difference between the two scenarios is that scenario 1 uses only lists of ontology vocabulary extracted from the reduced graph, while scenario 2 uses a reduced ontology graph serialized in turtle format. As shown in Fig. 1, the intention of the first scenario (Scenario 1) is to provide LLM with the necessary vocabulary information as a context to explore the degree to which LLM can answer the NL questions. The vocabulary information is composed of a list of classes, instances, and relations extracted from the RINF ontology, as described in Section 3.4. This scenario is mainly oriented to be used with LLMs that have a limited or relatively small token size window such as GPT-3.5. The second scenario uses a reduced graph version of the RINF ontology graph serialized in RDF turtle format to overcome the limitation of the LLM context window size and conform to the Gemini specification. Finally, the results between the two are compared in terms of the generated SPARQL correctness.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proposed model design and evaluation Scenarios. RINF, Registers of Infrastructure; ERA, European Union Agency for Railways; SPARQL, SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language; RDF, Resource Description Framework.

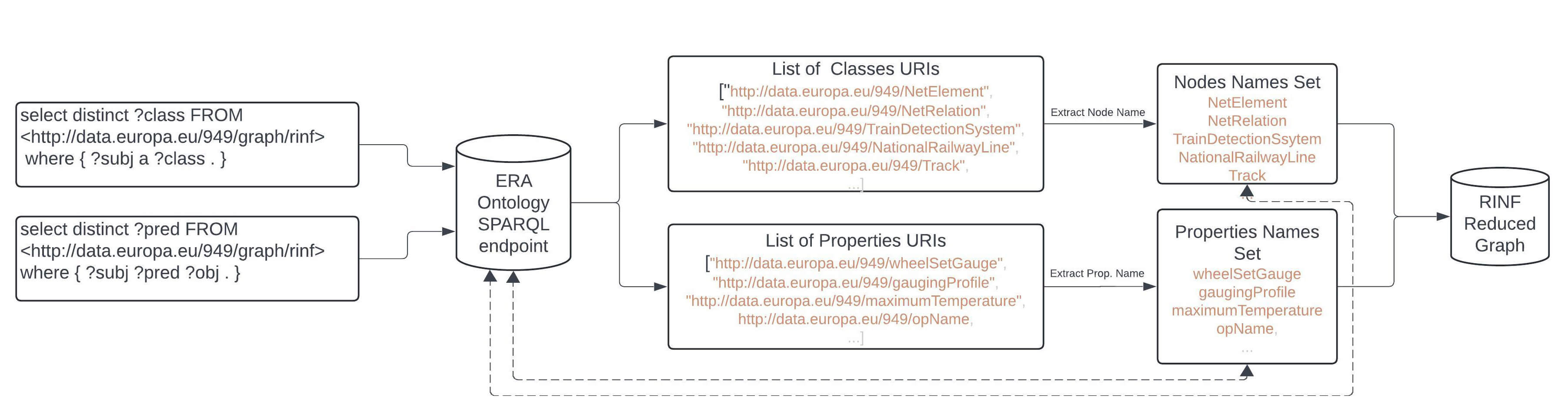

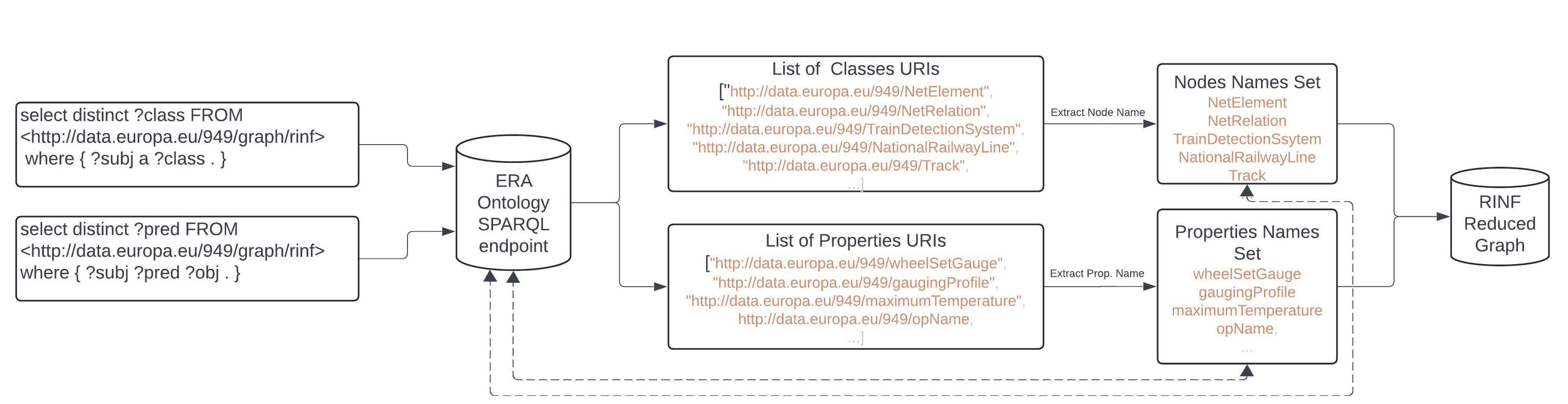

Initially, our reduced graph generation starts by creating an empty graph. Parsing the entire ERA Vocabulary ontology from the RDF. The graph content will be used later to fetch triple information for our ontology vocabulary information list and reduced graph. Since LLMs are constrained by the size of the context window, reducing a graph becomes a crucial step. To create a reduced graph, as illustrated in Fig. 2, we initially retrieve all classes related to the RINF ontology from the ERA endpoint using the SPARQL query shown below in real time and save their corresponding URIs in a list called relevant classes. This will return 21 URIs classes that RINF employ. Obtaining the ontology information directly from the endpoint allows our model to count for any changes or updates that may occur on the KG.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Reduced RINF graph generation process.

select distinct ?class FROM ¡http://data.europa.eu/949/graph/rinf¿ where ?subj a ?class .

Then, we retrieve all properties used by entities using the SPARQL query below and save their corresponding URI in a list called relevant properties. The process will return 226 predicates URI from RINF.

select distinct ?pred FROM ¡http://data.europa.eu/949/graph/rinf¿ where ?subj ?pred ?obj .

The URI contents of the two lists will be used to generate the reduced graph. The results retrieved from both queries are in JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) format and contain URIs only. To create our reduced graph and populate it with triples corresponding to extracted URIs, we first extract the complete URIs from JSON list, for example, the URI (http://data.europa.eu/949/OperationalPoint) followed by extracting the last fragment of the URI which represents a resource name or a class, in this particular case is OperationalPoint class. To create our reduced RINF graph, we loop through all extracted fragments and retrieve their corresponding triples from the original ERA ontology.

To generate vocabulary information for our reduced RINF graph intended to be injected into our LLM prompt, three empty sets are created (main class, properties, and instance of class). A Python Set data structure is used instead of a list to prevent duplicated triples from being appended.

A method is created that iterates through all triples (s, p, o) in our RINF reduced ontology to extract classes, instance of a class and properties. The subject part can represent one of two concepts, a class or an instance of a class. The separation between the two concepts is based on the properties that they use within the triple. If the property is of RDF type and the object resource does not represent a type of rdfs class, then it can be concluded that the subject is an instance of a class and the object is a main ontology class, subsequently added to a list called instances of class. Otherwise, if the property is not of RDF type, then it is appended to the properties list. Finally, three sets are generated that represent the vocabulary of our reduced RINF graph and can be found in the GitHub repository.

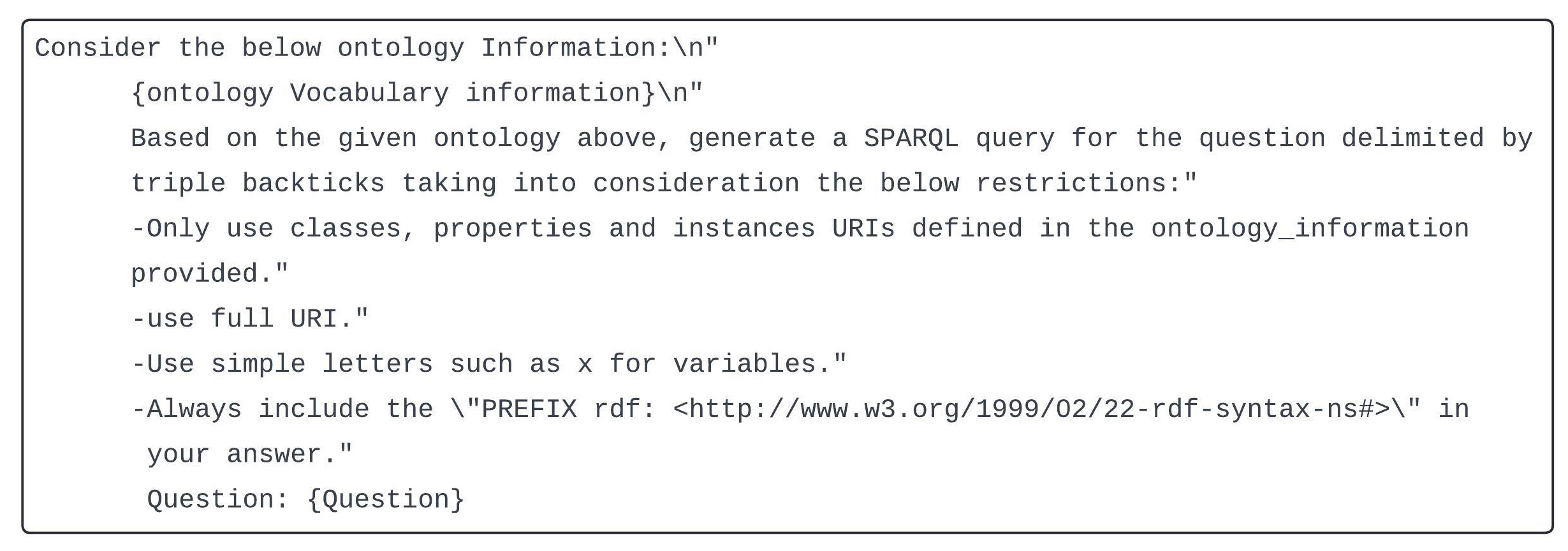

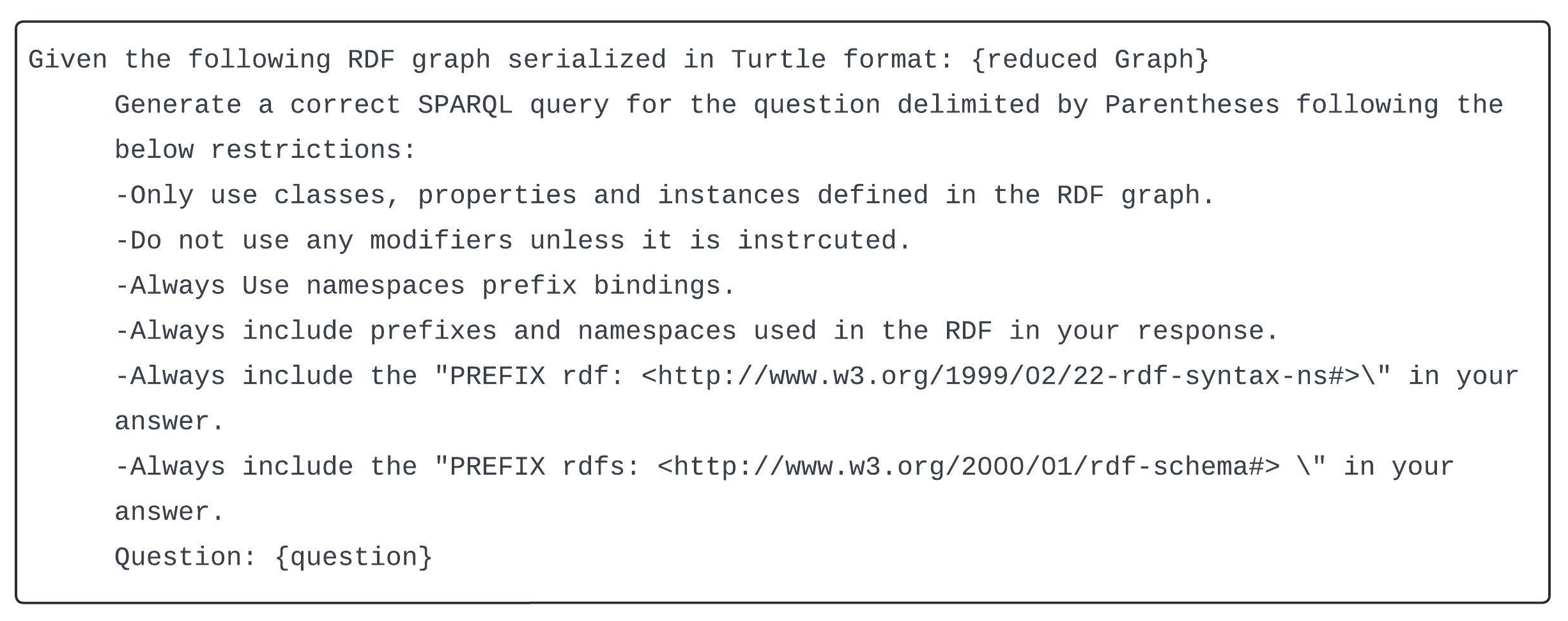

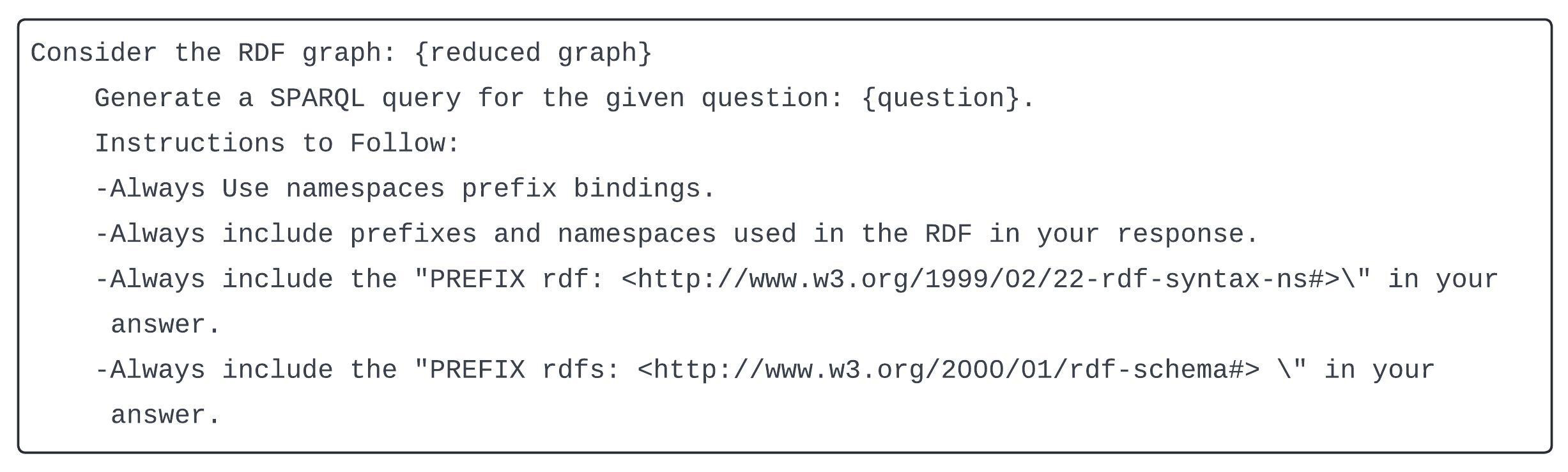

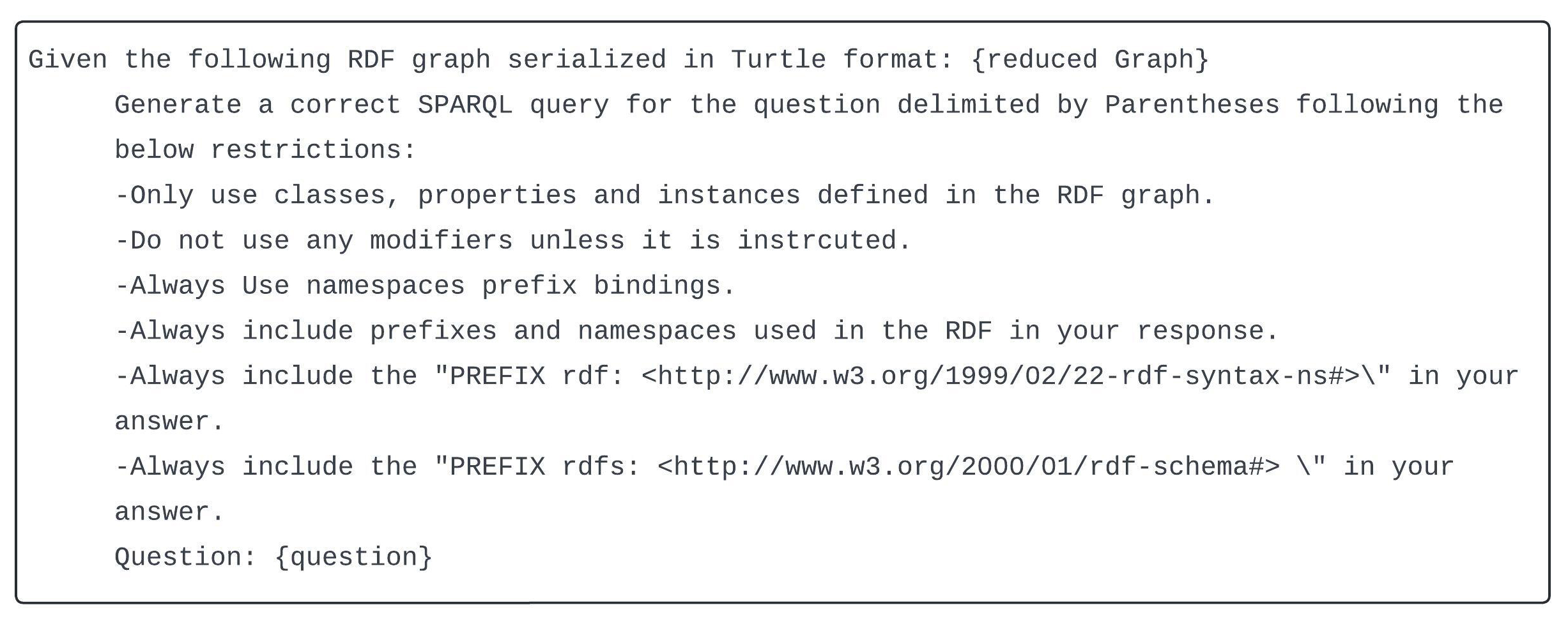

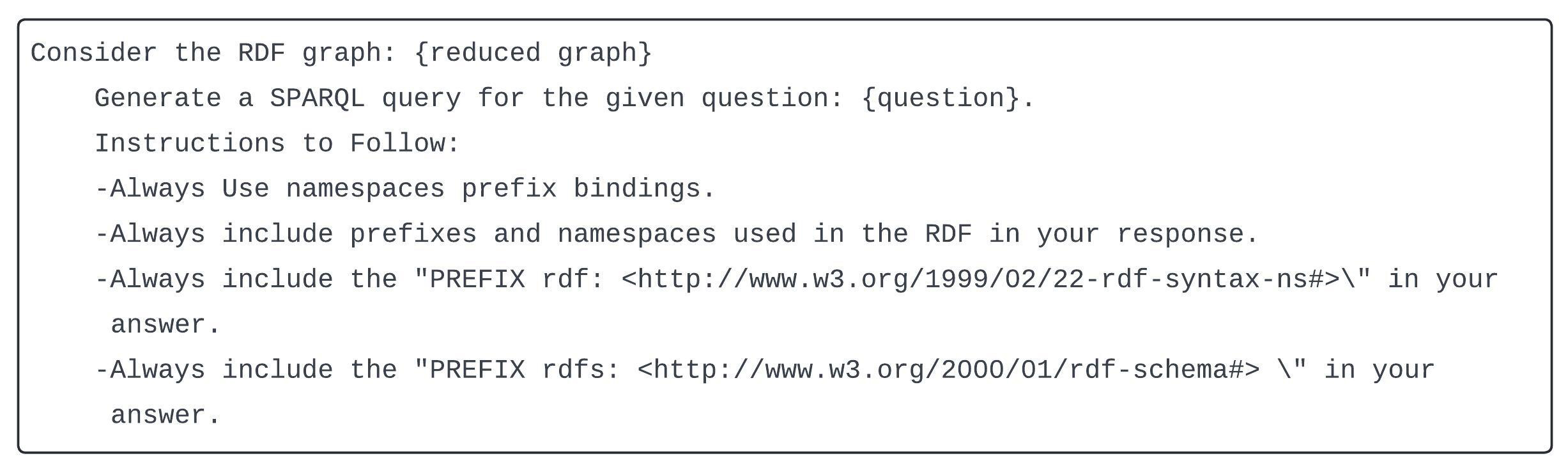

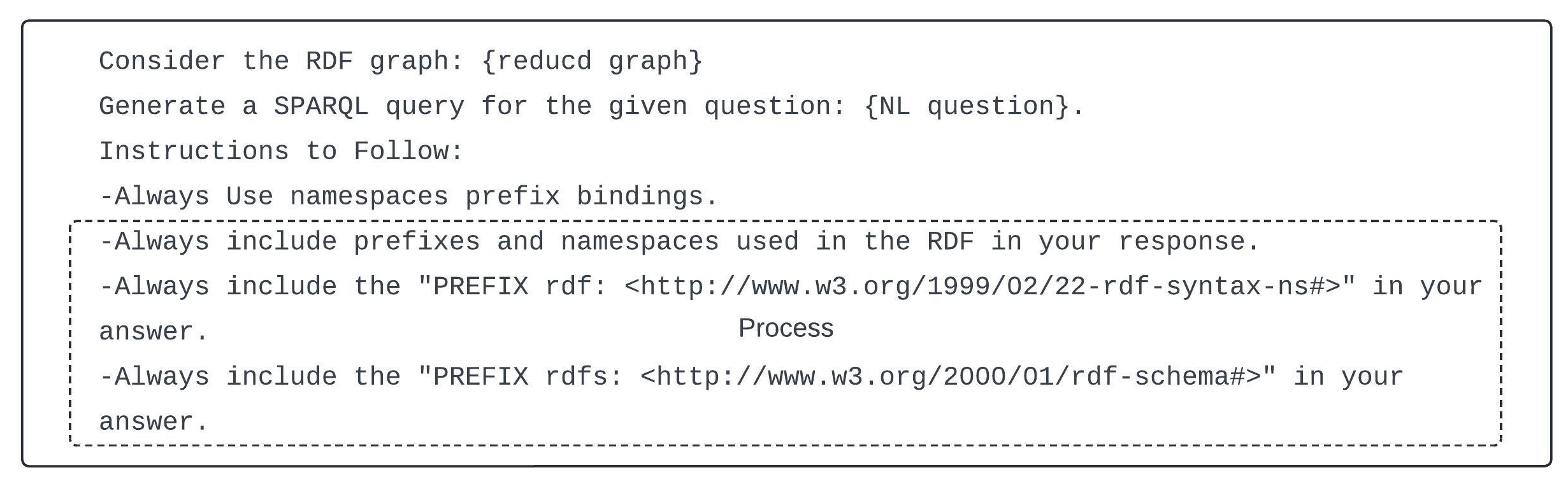

Prompt engineering is a delicate step in calibrating LLM to generate relevant responses that align with the intended tasks (White et al, 2023; Marvin et al, 2023), in our case translating NL questions into SPARQL queries. Generally, our proposed LLM prompts consist mainly of three parts: LLM orientated instructions part, the original NL question part supplied by the user, and the knowledge base part. The prompts labelled P1, P2, and P3 as illustrated in Figs. 3,4,5, respectively, were formulated after a detailed analysis of the requirements of the task and outcomes format required ensuring the inclusion of all elements that could efficiently guide the LLM to produce the desired responses and enforce rules in terms of context and format. More specifically, to effectively guide the model and enforce rules that ensure specific qualities of the generated responses, we have experimented with various prompt contexts by altering the phrasing of the LLM instruction parts while maintaining the NL question and knowledge base unchanged, which allowed us to observe the impact of LLM orientated instructions modification on the outcome rather than the effect of the knowledge base information. It was very clear that the complexity and expressivity of the LLM oriented instruction part of the prompt is directly proportional to the accuracy of the generated results, which can be tuned depending on the content and format of the required results (He et al, 2024; White et al, 2023). Consequently, each prompt was evaluated according to its ability to produce accurate and consistent responses. The optimal prompt was then selected based on several criteria, such as task alignment, completeness of retrieved responses, and consistency of SPARQL over multiple executions.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

P1, LLM prompt structure with ontology vocabulary information.

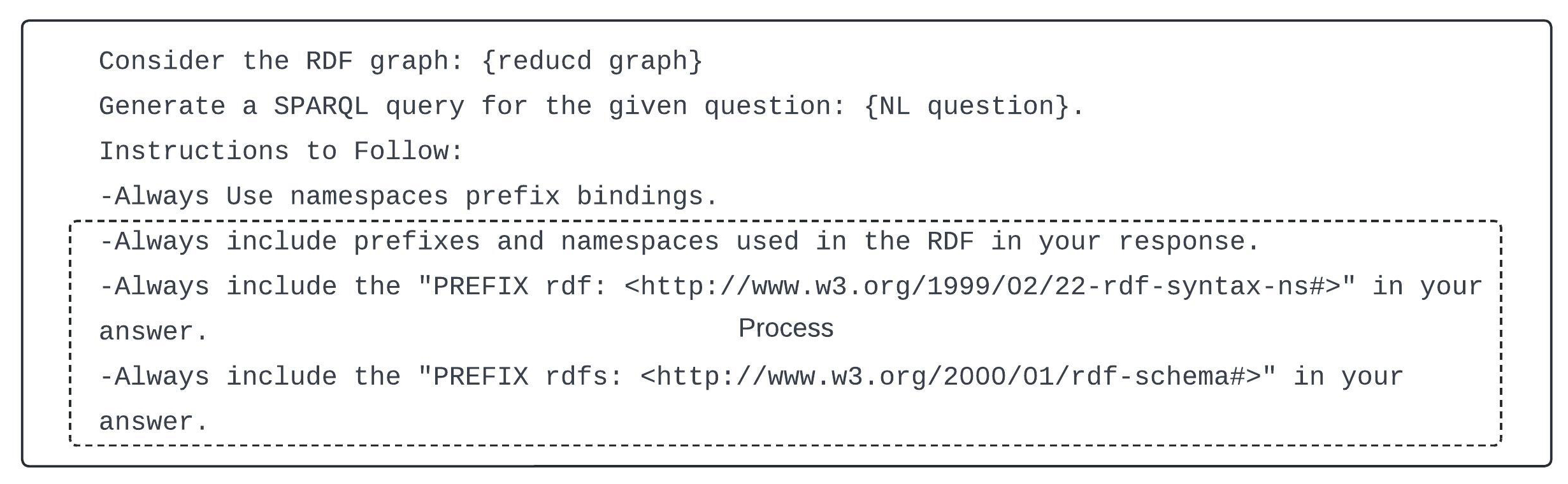

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

P2, Detailed LLM prompt structure with reduced RINF graph.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

P3, An Abbreviated LLM prompt structure with reduced RINF graph.

In our proposed approach, three versions of prompts (P1, P2, and P3) are used against two LLM models. In addition to providing the NL question, knowledge information is passed in two different forms: as discrete ontology vocabulary lists or as a reduced graph serialized as RDF format. To be more specific, P1 as shown in Fig. 3, is used to provide LLM with only extracted discrete vocabulary information using three lists (main class, properties, and instance of class) generated as explained in Section 3.4, each of which contains vocabulary extracted from the RINF ontology KG, while P2 and P3 use the reduced RINF graph serialized in RDF generated as described in Sections 3.3. The main difference between the two is that P2 and P3 are more expressive than P1 in terms of knowledge utilization and semantics, which allowed us to compare LLM ability to translate NL to SPARQL between the two. The NL question is passed to the LLM without any pre-processing, as our intention is to evaluate LLM responses over different knowledge forms.

Even though the augmented KG information within the prompt significantly impact the correctness and the semantic accuracy of the generated SPARQL query, it is important to note that employing specific explicit directives within the prompt can influence structural consistency and correctness of the generated SPARQL queries. For example, the directive specified in P1: “Only use classes, properties and instances URIs defined in the ontology_information provided” reduced LLM hallucination of the instances and properties and forced LLM to map terms in the NL question with the correct vocabulary, eliminating this directive, especially with our proposed vocabulary method, can lead to incorrect mapping of instances and properties. On the other hand, during experiments and by analysing the LLM SPARQL responses, we have noticed inconsistent use and sometime incorrect use of property and entity URIs mainly due to incorrect use of prefixes. Moreover, the LLM SPARQL responses in terms of binding prefixes to URIs were inconsistent over multiple runs for the same NL question. As shown in P1, P2, and P3, including explicit namespaces or PREFIX directives such as “Always use namespaces prefix bindings” and “Always include prefixes and namespaces used in the RDF in your response” can contributed to the consistency of URIs used within the generated SPARQL query over multiple runs for the same NL question, eventually eliminate incorrect URIs prefix binding inconsistency and improve human readability. Another noticeable source of error is that LLM’s tend to unnecessarily complicate SPARQL queries with modifiers, this can be mitigated by instructing the LLM with the directive “Do not use any modifiers unless it is instructed” to force LLM not to use any SPARQL modifiers unless it is explicitly stated in the original input question. This directive has contributed to the simplicity and consistency of the generated SPARQL and reduced SPARQL structural errors.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, once the prompts are generated as shown in the previous section, it is passed to the LLM API to generate the SPARQL query. The generated SPARQL is then passed to the ERA SPARQL endpoint to retrieve the answers. Minor text processing can be applied to eliminate spaces, carriage returns, and escape characters in the generated responses produced by certain LLMs such as Gemini.

This section covers LLM configurations used in our experiments, as well as analyzing responses generated by the experiments carried out in this research.

Two different LLM models were implemented, Gemini (gemini-pro) from Google9, and GPT-3.5 (GPT-3.5 Turbo) from OpenAI. Gemini is used for its considerable input token capacity and its superior performance metrics in code generation relative to GPT-3.5 (Hou and Ji, 2025; Islam and Ahmed, 2024). Gemini has an input token limit of 30,720 tokens, making it a perfect choice to pass our reduced RINF Graph as RDF file. GPT 3.5 is used due to its wide acceptance and popularity in the research community during the time this work was conducted. We utilized the API provided by Google and OpenAI to pass prompts and retrieve responses.

All prompts, including its supplementary information, are passed as text to LLM. Throughout the experiments, LLMs temperature was retained at 0.4 to maintain consistency across all results. It is important to recognize that reducing the temperature leads to a decrease in randomness and diversity and produces more deterministic responses that reflect our use case requirements of being accurate rather than creative (Tufek et al, 2025; Fakhoury et al, 2023). Our model is implemented using Python (version 3.12.1., Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA).

In general, our experiments test the ability of LLM to translate NL questions into SPARQL queries based only on the content passed from the domain-specific KG information. As illustrated in Section 3.1, our experiment employed 20 NL competency questions formulated based on RINF KG. Moreover, all NL questions were passed as text without any kind of Natural Language Processing (NLP), allowing us to examine the impact of different KG data arrangements on LLM responses. The correctness and evaluation of the returned SPARQL queries were manually evaluated and checked by taking the LLM responses and executing it against the complete original KG through the ERA endpoint. The results of the experiment are summarized in Table 2. As described in Section 3.5, P1 refers to the prompt template that only incorporates discrete vocabulary data derived from the minimized RINF graph; recall Section 3.4. In contrast, P2 and P3 prompts employ a fully reduced RINF graph extracted as described in Section 3.3. These three prompts were passed to two distinct LLMs (GPT-3.5 and Gemini) to retrieve their corresponding SPARQL queries.

| Columns | COL1 | COL2 | COL3 | COL4 | COL5 | COL6 |

| Prompt | P1 | P2 | P3 | P1 | P2 | P3 |

| Q1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Q7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Q10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Q12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Q13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q14 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Q19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Q20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Correct Answers: | 10 | 10 | 10 | 17 | 15 | 17 |

| Accuracy Percentage | 50% | 50% | 50% | 85% | 75% | 85% |

COL, Column; 1 indicates for correct response and 0 refers to incorrect response from SPARQL endpoint.

A quick analysis on the results of Table 2, GPT 3.5 turbo has consistently achieved 10 correct responses out of 20 achieving a precision of 50% for each prompt (P1, P2, and P3). In contrast, Gemini achieved 17 correct answers generated from P1 and P3, and 15 correct answers against P2, achieving an accuracy of 85% for P1 and P3, and 75% for P2. consequently, in terms of overall performance and based on the statistics above, it can be concluded that Gemini outperformed GPT 3.5 turbo in all scenarios.

Furthermore, a careful analysis and contrasting of the two LLM models responses corresponding to P1 (Col1 and Col6) with the responses of P2 and P3 (Col2, Col3, Col4 and Col5), it is evident that GPT-3.5 Turbo exhibits consistent performance across all types of prompt, indicating that augmenting different arrangements of KG information (vocabulary vs. RDF triples) does not have a noticeable effect. In contrast, Gemini exhibits high performance with both types of KG data arrangements but with a slight dip in accuracy for P2. This suggests that although Gemini is effective with both structured RDF triples and vocabulary, it is evident that LLM augmented with vocabulary information can provide the same level of accuracy compared to RDF triples. Hence, it can be concluded that the integration of vocabulary information achieves a competitive accuracy to that observed with P2 and P3 using GPT 3.5 and Gemini. This is a very interesting insight, because the word count is much smaller when comparing the vocabulary context size with the reduced graph size. This gives a clear indication that LLM can select correct entities and relationships and generate correct SPARQL quires based on discrete vocabulary information provided and not fully dependent on the semantics that can be deduced from a reduced KG triples at least on questions that do not require logical reasoning over multiple triple paths, which we believe that LLM need to do reason over triple paths within the KG to answer such complex questions.

A careful review of the responses generated using Gemini indicates that the responses were much more focused and detailed in terms of outcome representation than those obtained with GPT-3.5 Turbo. More specifically, for example, Q1 corresponding to the NL question “Please give me a list of all operational points.” has been answered correctly by both models using all three prompts. Although the responses of P1, P2, and P3 produced correct answers by returning the answers as URIs, Gemini generated SPARQL queries in which its responses (corresponding to P2 and P3) are more human-readable in terms of the presentation of the returned answer by returning only the labels of the “operational point” rather than the URIs which are more easily interpreted and understood by users. This indicates that Gemini has a greater ability to understand the semantics of the question and to produce more human-readable responses based on the question rather than returning only the URIs, which sometimes need to be investigated to get the required answer.

On the Question-Level Performance side, it is obvious that both models have accurately answered simple lookup questions (e.g., Q1 through Q5) across all proposed prompts. With more complex questions that involves filtering, aggregation, or multiple triples (e.g., Q6 to Q20), Gemini maintained higher accuracy, while GPT-3.5’s performance dropped significantly. Other questions (e.g., Q9, Q11, Q12, Q18, and, Q20) were challenging for both models, indicating difficulties with complex query structures or specific domain vocabulary.

The outstanding performance of Gemini compared to GPT-3.5 in translating NL to SPARQL can be owed to several reasons including architectural design as well as training advancements. Recent studies showed Gemini model features a large context window size up to 1 million tokens (Team et al, 2024), whereas GPT-3.5 is only limited to 16K tokens (Brown et al, 2020). The extended capacity allowed Gemini to be augmented with extensive vocabulary and ontology information within the prompt, providing more contextual accurate SPARQL translation. Moreover, according to (Li et al, 2024), Gemini demonstrated stronger ability to synthesize syntactically correct and semantically meaningful code which in return contributed to improve the performance on task related to code generation which is closely aligned with the NL to SPARQL translation task. The aforementioned factors collectively can justify to some extent the outstanding performance of Gemini over GPT-3.5 in the domain of NL to SPARQL translation.

In a more general prospective, our experiments show competent performance when augmenting KG vocabulary information rather than reduced KG of RDF triples, which makes it suitable for large domain-specific KGs, given that: (1) the vocabulary approach prevents instance and relation hallucinations during the LLM inference process; (2) our model accounts for any updates as it generates vocabulary information directly from the KG endpoint; (3) reducing the size of tokens passed to the LLM which gives more usable space to include more information in the future that may assess the LLM model to perform better.

A detailed look at the SPARQL responses in all scenarios shows that the main source of error is due to incorrect use or inference of properties, instances and missing prefixes. By further analysing the generated SPARQL responses, errors presented can be summarized into the following categories:

1. Mismanagement and misuse of prefixes: Several queries either missed required prefixes or defined incorrectly, for instance, the namespace for ns2 (http://data.europa.eu/949/) was inconsistently included or entirely missing, especially in GPT-3.5 prompt variants, this can be prevented by giving an explicit instruction to include prefixes in the prompt to as shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Prompt namespace directives.

2. Misuse or incorrect inference of properties: Some queries used generic Resource Description Framework/Web Ontology Language (RDF/OWL) properties such as rdf:type, or rdfs:label instead of targeted domain-specific properties, for example ns2:operationalPoint and ns2:trackGauge. In more complex questions such as Q4 and Q5, wrong properties were inferred by the LLM resulting in a syntactically correct but semantically incorrect queries.

3. Query Structure Issues: in some responses that requires nested SPARQL query, the structure of the SPARQL query were mishandled. For example, the questions involving numeric comparisons (e.g., maxSpeed properties) led to misuse of FILTER clauses or incomplete OPTIONAL blocks.

4. Vocabulary Hallucinations: There were several instances where incorrect vocabularies were introduced, indicating confusion in entity/property mapping due to LLM hallucinations, this can be mitigated if more information is augmented thorough prompts.

Most of these issues can be bypassed either by giving a detailed prompt instructions and directives to include prefixes as in P2 and P3, clearly illustrated in Fig. 6 or by using NLP methods.

The paper presented experiments to examine and investigate the ability of GPT 3.5 Turbo and Gemini to translate NL questions to SPARQL queries and generate responses over domain-specific KGs by examining the impact of augmenting prompts with different arrangements of KG information on LLM responses.

The experiment presented in this work concluded that Gemini outperforms GPT 3.5 turbo in converting NL queries to SPARQL in all scenarios. Additionally, utilizing prompts augmented with vocabulary information extracted from a reduced ontology KG shows competitive performance levels relative to prompts augmented with a reduced RINF triples graph. Hence, the importance of incorporating vocabulary information in generating SPARQL queries is clearly evident, which can contribute to reducing the size of the augmented KG information, hence reducing the number of tokens passed to the LLM while preserving an accepted level of response accuracy. Finally, and from a general prospective, the experiments suggest that LLM has great potential in the domain of KGQA systems, being able to translate NL questions for domain-specific KGs without the need to augment a large amount of KG information, as well as its accountability for any changes or update in the ontology since it directly obtains the KG information directly from the ERA KG endpoint.

Furthermore, our proposed method for extracting vocabulary information from a reduced RINF KG can be considered as domain-agnostic and can be utilized over any KG over different domains such as healthcare, finance, or any other domain. The reason behind this is that most ontologies and KGs adhere to the semantic web standard and data interchange on the web (e.g., RDF, OWL, SPARQL) standardized by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) consortium, which allows persistent standard access to classes and property hierarchies as well as annotation within the ontology. Extracting vocabulary from any available KG endpoint is a straightforward task, as they all follow the same principles and standards of semantic web and RDF standards, and then by using our proposed method, the LLM can be augmented with domain-relevant relevant vocabulary and terminologies that are specific to the target domain. Hence, our proposed approach ensures adaptability and scalability across diverse use cases and domains.

Future work may include developing an accurate algorithm to reduce domain-specific KG based on NL questions. Furthermore, improving the accuracy of the responses by incorporating NLP techniques to provide more information and insight on the semantics of the question to the LLM and updating the vocabulary information accordingly is another prospective research.

The data sets, experiment codes, results, RINF ontology, SPARQL queries and competency questions generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Github repository at this link https://github.com/mhrjabary/NL-TO-SPARQL-RINF.

MHR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Dataset curation, Software and coding Writing—original draft. MA: Validation, Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Resources. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.