1 Computer Science - School of Science and Technology, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia

Abstract

Managing personal electronic records that individuals and households receive and must address in daily life such as bills, receipts, and warranties is often frustrating, and oversights can result in unnecessary costs, including fines for overdue bills or penalties for driving an unregistered vehicle. Important personal records sent as a hyperlink in an email rather than an attachment may not remain available. Systematically saving and sorting personal electronic records leads to higher levels of satisfaction, reduced oversights such as missed payments, and increased motivation to attend to the management of personal electronic records. Information in personal records is often summarized allowing users to view how much they are spending on various categories such as utilities or subscriptions. This paper discusses findings from a user trial of a prototype application designed to aid personal electronic records management and task management at home by downloading, reading, analyzing and summarizing the content of personal records. Findings suggest a personal records management application can assist with timely task completion, such as paying bills, simplifying personal records management, reducing oversights and improving records management. The prototype alerted users that they may need to retrieve records that they did not anticipate needing again. Easier management and tracking of expenses and identification of unnecessary spending may encourage users to enhance their records management. The ability to extract information from personal records can generate innovative ideas for making everyday life easier. This study adds to the body of knowledge in the development of personal records management applications and to the wider domain of personal information management.

Keywords

- personal electronic records management

- personal information management

- records management

Research has identified dissatisfaction amongst people managing their personal information (Alon and Nachmias, 2020b; Jones, 2015), using terms such as ‘anxious’, ‘frustrated’ and ‘desperation’ (Alon and Nachmias, 2020a). While there are many tools available to assist users in the management of specific types of personal electronic records, such as photographs (Whittaker et al., 2009), recipes (Hartel, 2010), collections (Cushing, 2013), and so forth, these do not address the overarching management of personal information in daily life and household matters such as bills, receipts, and warranties (Balogh, 2025). This work falls within the broad domain of personal information management (PIM), encompassing information that people individually manage in both work and home settings and includes both electronic and paper-based records (Jones et al., 2017). A subset of PIM is personal electronic records management (PERM), which focuses on the processes of how people manage the electronic records that they and their households receive and must deal with in their daily lives at home, such as bills, receipts and warranties as PERM (Balogh et al., 2022b).

Qualitative research using the guided tour method of participants’ home records management identified a problem: important personal records are often sent as hyperlinks in emails rather than as attachments. These records can become inaccessible if users no longer have an active relationship with the service provider that issued them (Balogh et al., 2022a). Additionally, personal electronic information management tools for use in people’s daily lives are rarely able to read and use the content of the electronic records that they manage, therefore requiring users to manually enter information (Balogh, 2025). Oversights can result in unnecessary costs, including fines for overdue bills or penalties for driving an unregistered vehicle (Balogh, 2025; Balogh et al., 2024).

Systematically saving and sorting personal electronic records leads to higher levels of satisfaction, reduced oversights such as missed payments, and increased motivation to attend to the management of personal electronic records (Alon and Nachmias, 2020b; Alon and Nachmias, 2022; Balogh et al., 2024). Analysis of the online survey results found a relationship between practices and self-reported levels of satisfaction with their personal records management. For example, participants that saved records on a computer or in the cloud reported higher levels of satisfaction with how they managed their personal records and experienced fewer adverse events such as losing documents or missing a bill payment as compared to those that did not save records outside of email (Balogh et al., 2024). Organizing and categorizing records into folders can lead to increased satisfaction with records management tasks and a decrease in oversights. Additionally, the study found that individuals are more likely to adopt specific PERM practices such as storing and retrieving records efficiently if they perceive the process as being as easy as or easier than their current methods. Moreover, they are more likely to embrace such practices if they believe the approach offers clear positive outcomes, such as simplified tax reporting, improved budgeting, or reduced oversights (Balogh et al., 2024).

Analysis of both the guided tour research and the online survey identified three key oversight risks in PERM and proposed solutions for each of these (Table 1).

| Oversights | How oversights are avoided | |

| Missing ‘pull’ records; i.e., records sent by email as hyperlinks to the record, rather than as PDF attachments | By retaining records not attached to emails (i.e., records that may not be retained by relying on an inbox for records management) | |

| Overlooking emails that need to be addressed or responded to due to too many emails in the inbox | By helping users manage email and to use the inbox as a to-do list | |

| Overlooking bill payments, renewals and cancellations and failing to review records such as statements | By reminding users of upcoming bill payments, renewals, and cancellations |

(Balogh, 2025).

The analysis also examined the difficulties in PERM and proposed ways to make it easier to organize and re-find records, summarizing the information in retained records and reducing time and paperwork in personal records management (Table 2).

| Difficulties | How difficulty is overcome | |

| Difficulty in re-finding records when required | By making it easier to re-find records when needed without reliance on search terms | |

| Problems associated with not grouping related records | By helping organize and categorize personal records | |

| Unnecessary and unwanted retention of records in hardcopy | By reducing the proportion of records retained in hardcopy | |

| Untracked expenses and unmanaged budgets | By summarizing expenses by services in a simple table | |

| Lack of time available to manage personal records | By reducing the amount of time spent managing personal records | |

| Unnecessary costs such as un-required subscriptions | Improving users’ bottom line by saving costs on late payments or unwanted subscriptions |

(Balogh, 2025).

This paper reports on the evaluation of a prototype application designed to test the effectiveness of the proposed improvements in PERM. The application is evaluated against the core objectives of avoiding oversights in personal records management at home, assessing the benefits of categorizing personal records and making the management of personal records easier, while ensuring flexibility for individual needs and integration with other applications.

Two prominent themes within PERM and PIM revolve around whether individuals sort their information or records and their reliance on email applications for storing such data. Regarding record sorting, existing literature discusses various categories of records management styles: for example “pilers” or “no-filers”, who typically do not organize records into folders and allow them to accumulate in paper or electronic piles (Henderson, 2009a; Henderson, 2009b; Whittaker and Hirschberg, 2001); “periodic filers” or “spring cleaners”, who periodically file groups of items (Jones, 2008); and “filers”, who sort everything into folders as they go (Oh and Belkin, 2011). Another significant theme investigates whether individuals manage their records within their email or adopt alternative methods (Gwizdka, 2004; Whittaker et al., 2006; Whittaker et al., 2007). Leaving all emails in the inbox corresponds to the behavior of pilers, while organizing emails into folders aligns with the actions of filers (Balogh et al., 2024).

Throughout the PIM literature there are accounts of experiments with systems to improve or automate aspects of personal information management or personal records management, such as Haystacks (Karger et al., 2020; Karger et al., 2005), MailCat (Segal and Kephart, 1999), Treetags/Linked Treetags (Albadri and Dekeyser, 2022; Albadri et al., 2016) and TV-acta (Bellotti et al., 2007). The experience of another prototype, Taskmaster, shows that the transition must be painless—people will not use two systems, even for a transitional period (Bellotti et al., 2003, p. 6). In 2000 Dourish and colleagues (2000, p. 10) proposed Placeless Documents or Placeless, an operating system that avoided the use of folders and replicated files across locations in the way that home and work computers and networks typically operate (distributed system). Instead, Placeless used file properties, such as the topic (active properties) and importance, and records were stored in ‘kernels’ essentially a metadata database. Placeless permitted different uses to apply different properties to the same file. Placeless Documents was also intended to cater for workflow, with the notion of active document properties—a form of metadata (Dourish, 2003, p. 12). In retrospect the authors found that user confidence and willingness to adopt the new tool was impaired by a lack of connectivity between placeless and other applications (Dourish et al., 2000, p. 12). Ideally the system must also be open and not entrenched in any particular technology—a prototype should be able to be replicated in alternative software or systems by anyone who cares to do so (Billingsley, 2016, p. 172; Buttfield-Addison, 2014).

Lessons have been learnt from these and other prototypes, such as the need to ensure easy and full compatibility with other software, which was one of the lessons learnt from Haystacks (Karger et al., 2005; Karger and Jones, 2006). While few of these prototypes have developed into complete applications, many have influenced either the development of existing or ensuing applications (Dix, 2024; Kljun et al., 2013).

Existing commercial applications that may be used for some aspects of personal records management are often characterized into two groups; broad applications such as spreadsheets and notes applications, and specialist applications. The broad applications and notes applications are not specifically designed for records management, but is often used to manually save information. Evernote (Evernote Corporation , 2022) is an example of an advanced notes facility which synchronises notes between devices, and can include text, images, audio, and PDFs. These tools offer users the opportunity to make notes or insert files or images, which are synchronised between multiple platforms, such as mobile phones, tablet computers or iPads, laptops, and desktop computer software or online websites. Notes applications do not perform PERM functions such as managing records, bill payments, subscriptions, or other tasks that may be required in daily life and household management.

There is other specialist software that is often used for specific aspects of PERM such as managing photographs (Whittaker et al., 2009) recipes (Hartel, 2010) and health and informatics applications are a prime example of specialist applications for a specific aspect of people’s daily lives. Adobe Lightroom is an example of an application which creates a catalogue of photos, edits, and categories (Lightroom, 2022). Splitwise (2022) is an application for managing expenses between two or more people, such as bills in a shared accommodation, or expenses amongst a group of people travelling together. TripIt is an example of a travel management application which assembles an itinerary out of emailed travel and accommodation bookings. Many banks offer applications for keeping information about payments and receipts, such as Slyp Smart Receipts, a tool offered by the National Australia Bank (2022) that allows users to ‘Share a Smart Receipt with your accountant or merchant at the touch of a button’. Nevertheless, specialist software, such as software for managing travel planning, does not address the overall challenge of personal records management at home. Additionally, specialist software may contribute to the complication of personal records management by requiring the use of multiple applications that may not synchronise with each other. However, specialist software can provide many ideas for how a PERM application could work; for example, the shareability of Splitwise, the reading of details in attachments of TripIt (2022), and the note-making of Evernote.

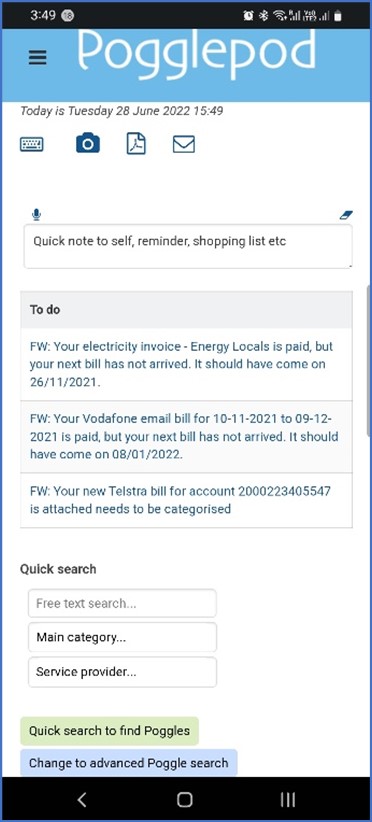

The prototype application was designed to minimize oversights in personal records management (Table 1) and deliver tangible benefits by providing ‘to-do’ lists for task management by making use of their personal records to better understand their expenditure and to make tax reporting easier (Table 2). The prototype’s interface centered around a ‘to-do’ list (Fig. 1), because this presentation provided the benefit of making it clear to users what actions they needed to take to avoid oversights in their personal records management. Fig. 1 shows the interface on a mobile device. The interface on a computer differed only in shape to the one shown. The to-do list comprised a prioritized list of new emails forwarded to the user’s account in the application and reminders for tracking or follow-up. Icons at the top offered different ways in which users could include records, for example, by entering a record by text or voice, taking a photo, scanning or emailing records to the prototype. The ‘to-do’ list showed records requiring user actions. The lower part of the screen offered user search capabilities. The application could be accessed online using a computer screen format or online with a mobile device format. A video demonstration of the application is often seen at https://youtu.be/9IhvHxuF1p0.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Application interface on a mobile phone.

The working name ‘Pogglepod’ was adopted to provide a one-word name for the application, of which the ‘Poggle’ part of this word was used to describe the records that people included in the system. Thus, a made-up word was chosen to remove any possible pre-conceived notions of what records or items should be included by users. The use of a made-up name allowed the research participants to develop their own ideas about what to include in ‘Pogglepod’, although some examples were provided in the explanation for participants to understand the purpose of the application.

The application was designed to address common frustrations in managing personal electronic records by providing a clear layout, intuitive navigation, and structured organization. At its core, the application enabled users to forward emails containing bills, receipts, or other important documents to a generic email address. From there, attached files and linked documents were automatically captured and added to the user’s account.

To keep records organized, the system used a multi-faceted categorization

process and stored documents within a folder structure that reflected those

categories. It also applied meaningful, standardized filenames—such as

“Vodafone bill September 2021 direct debit.pdf” or “All Roofing Services Pty

Ltd Invoice #18219 for

To maintain a manageable and relevant database, only records actively added by the user were stored, helping to avoid clutter from junk mail or trivial communications. Powerful retrieval tools allow users to find documents using free-text search, category filters, and date ranges.

The application uses a structured workflow to guide users through record stages such as “arrived but not categorized” and task reminders for actions like bill payments. Usability is prioritized through a clear interface, familiar icons, hover-over text, and consistent interaction patterns, all designed to support both individual users and those collaborating with others.

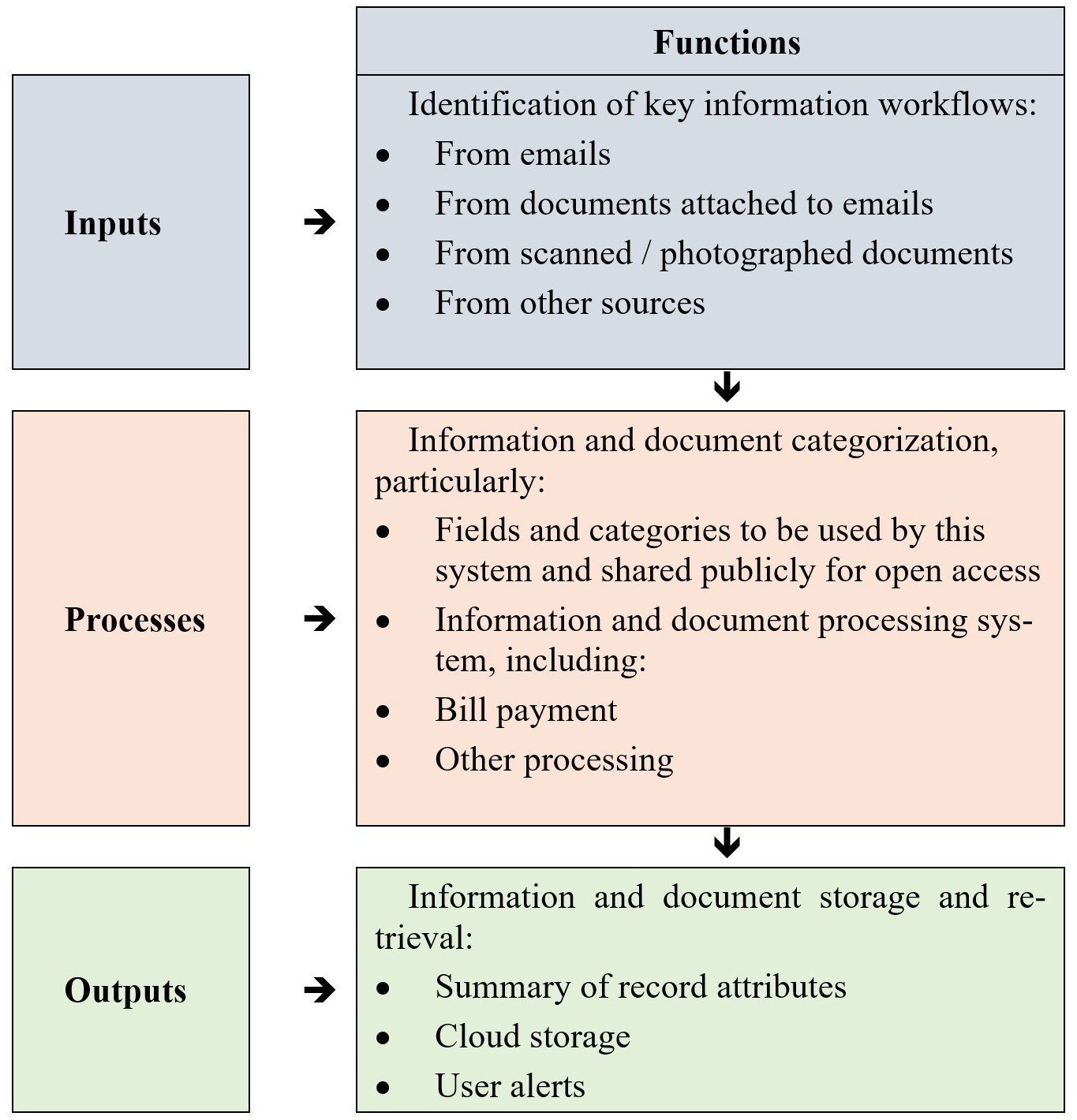

Fig. 2 illustrates the overall framework of the application workflow, starting with the inputs, such as from emails or other documents received, the processing of these by populating fields in the database categorizing and describing the records and thirdly, the outputs such as the expenditure summary and user reminders and alerts.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Application framework.

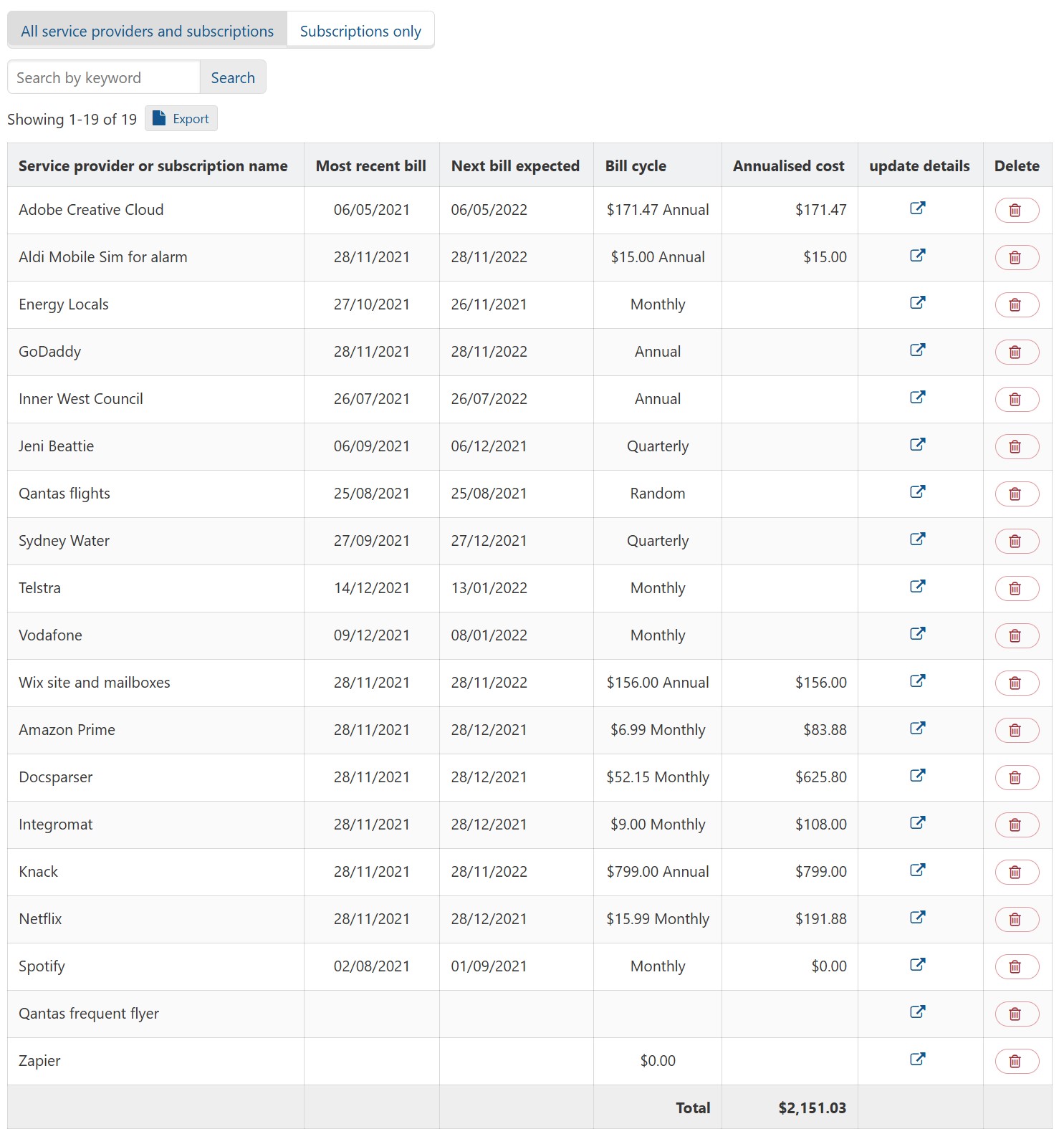

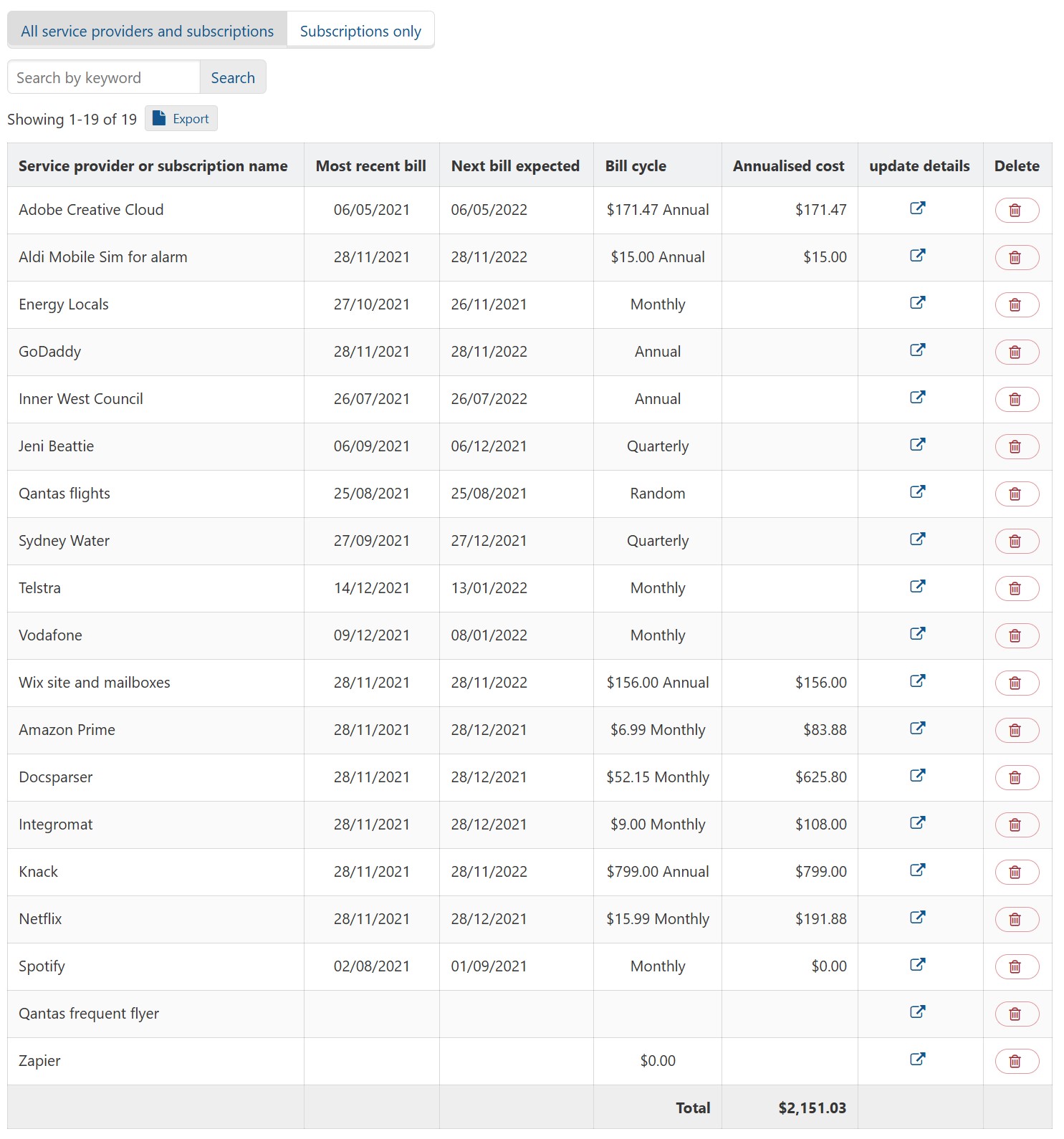

To help users understand and manage their spending, a ‘Service providers’ summary screen (Fig. 3) displays expenditure by provider, including an annualized total to help with budgeting. To support planning and oversight of upcoming obligations, the prototype includes a calendar view that shows records related to future appointments and due dates. To enable collaboration and shared responsibility, the application also allows users to share specific categories of records—such as bills or receipts—with others, including a significant other or an accountant.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Summary of service providers in the prototype to illustrate potential for summarizing records.

The prototype included a demonstration user account with 53 records that had already been categorized to illustrate a variety of uses of the application based on prior research, such as managing household bills, keeping track of manuals and warranties for appliances, keeping an electronic copy of documents such as qualifications and maintaining a searchable list of the user’s favorite recipes among other examples (Table 3).

| Record category | Number of records |

| Household bills | 15 |

| Manuals, receipts and warranties | 9 |

| Qualifications | 12 |

| Recipes | 5 |

| Miscellaneous | 12 |

| Total | 53 |

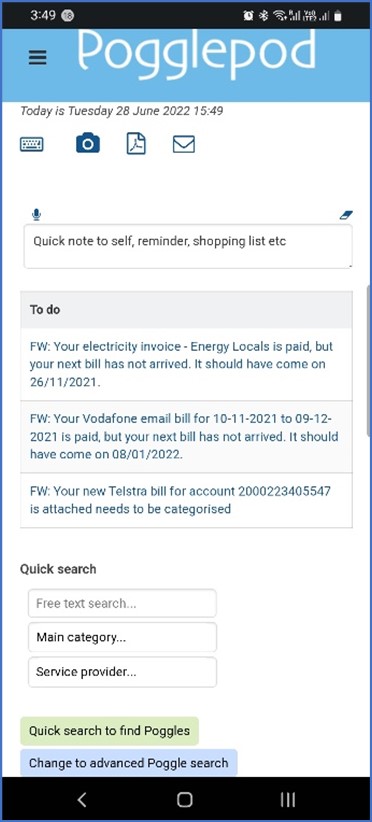

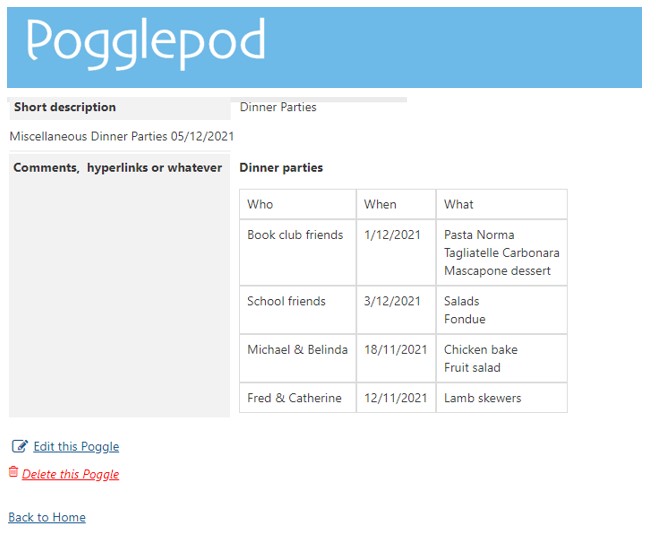

In order to provide an example of a record that might prompt participants in the research to explore more ideas for which the prototype could be used, an example record was created comprising a notation of people who had attended dinner parties hosted by the account holder, and what dishes were served to those guests (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Example record with dinner party records.

The next section describes how the prototype was evaluated to inform future applications designed to address similar objectives of reducing oversights and providing beneficial outcomes from personal electronic records management.

The evaluation was conducted by means of a multi-stage user-trial. A ‘walking through’ approach was used, wherein the participants were guided through a series of tasks while being observed (Lazar et al., 2009, p. 269). The user trial commenced with three in-person software labs, each with 6 participants, hence a total of 18 participants. Software labs are a variation of focus groups (Bloor et al., 2001) wherein the participants use a prototype of the software in order to evaluate whether the design works as intended, and to assess how users respond to the prototype (Arnowitz et al., 2007, p. 10). Bergman, Israeli and Whittaker used a similar approach, inviting research participants to bring their own devices, and filming them (Bergman et al., 2019; Bergman and Whittaker, 2016, pp. 83–85).

Participants were enlisted through Facebook invitation posts, enabling us to engage individuals beyond the confines of professional and academic networks. A brief screening questionnaire was employed to ensure a diverse representation of gender and age. No other screening requirements were required, as availability and willingness to attend were the priority during this COVID impacted period. Six participants were aged 18–39 and 12 were aged 40 and over. Eight participants were male and ten were female. Given the emphasis of the research on everyday household record management, we aimed to assemble a wide-ranging sample that wouldn’t disproportionately skew towards knowledge workers and students. During the software labs, users were shown how to use the prototype through a short video and verbal advice. Participants were then invited to start creating some records in the application. User activities included re-finding the records that they had created and categorizing them, followed by looking for records in the demonstration account by category of interest to them, and examining the summary expenditure table. Users then had the opportunity to explore the software as they wished. Users were also given access to a demonstration account within the prototype that had already been populated, as described in section 3.1.

At the end of the software labs, participants were asked to respond to an on-line questionnaire about their experience with the application. The questions addressed the participant’s views on how useful such an application might be to them in the future, how such an application would influence their personal records management behavior, and what benefits they might expect from such an application. The structured questions were designed to encourage all participants to share their perspectives on the prototype. While the sample size was limited, the insights gathered provided valuable qualitative feedback.

Six of the user trial participants were recruited to take part in an optional six-week period to further trial the prototype. During that period, participants were contacted by means of a short phone call after three weeks to remind and encourage them to use the application; to provide any assistance, to answer any participant questions and to get any initial feedback and comments from the participants in the user trial. Participants were contacted in a second short phone call and second online survey after six weeks.

The software labs were recorded and fully transcribed. Comments were first grouped into loosely defined topics and then re-sorted into more refined categories which became the section headings in the reporting. Verbatim quotations were selected for their relevance to the purpose of the research in a holistic and interpretive approach (Krueger, 2014; Rabiee, 2004; Williamson et al., 2018) in order to focus on the comments most pertinent to the design of the prototype application. The questionnaire contained only three pre-coded questions which have been reported numerically.

The use of social media to recruit participants provided a convenience sample during the COVID lockdowns when other methods of recruitment and participation were unavailable. While social media offers a potentially varied pool of participants (Vitak, 2016, p. 9), a recognized drawback of this method is that the sample is a convenience sample and therefore not a representation of a definable population. Consequently, the findings cannot be generalized to a wider audience.

The findings from this research are presented in terms of the key objectives; whether the application reduced oversights, and whether it made records management easier, whether the categorization of records was beneficial and whether the application was suitably flexible for the needs of the users. Results are mostly presented qualitatively. The number of respondents that gave certain answers to the structured questions is reported, although these are not of statistical significance due to the small sample size.

With regards to the ‘avoiding oversights’ objective, all 18 of the respondents said that the prototype made it easier for users to re-find records, both within the application, and potentially outside of the application by virtue of the use of folder categories and file names. While participants—both in this study and as noted in the literature—were able to re-find individual items using email search, the prototype made it easier to retrieve groups of records or combinations of groups outside of email, based on specific search criteria. Participants commented that they liked the fact that it established a personal repository of their electronic records, as illustrated by these comments:

‘Personal data archive, independent of the banks, accountant, email providers etc’.

‘It’s a neat filing cabinet’.

‘I think it would ensure quick access and avoid me losing track of bills and other documents. The downside would be honing-in on the best system of categorization to ensure I can keep track of things effectively. Also, would need guarantees on privacy and safety’.

Participants were most vocal about the prototype’s potential to reduce oversights in personal records management, such as not overlooking bill payments, illustrated by these comments:

‘I love the idea of all my insurance going straight through, so I get reminders, because sometimes we’ve missed NRMA bills’.

The following comment was made in relation to overlooking bills sent by email:

‘You’re not on second notice of the first email you saw of it’.

‘The concept is good, the whole fact that you can put in a bill and it will tell you that the next one is due, I think that kind of thing is good’.

Seventeen of the 18 participants in the research responded to a question in the survey at the end of the software labs by agreeing with the statement ‘The prototype would help ensure I don’t overlook things such as paying bills or renewing vehicle insurance or registration’, seven of whom agreed strongly with the statement.

With regards to having a ‘to-do’ list that reflects incoming emails that require actions such as bill payments, the prototype software trial indicated that this is often achieved, but probably not in the way that was tested in this instantiation. The issue with the application’s ‘to-do’ list, whether displayed in the default interface or through the prototype’s calendar, was that it created an extra place that users needed to check in addition to their email and their existing calendar of events. Participants suggested that closer integration with email would be better, for example:

‘…useful in providing that bridge from email to organized list. Possibly other options might seem ‘more hassle than they’re worth’ initially. What is the advantage of saving here than just keeping the email? On exploration it becomes more apparent what the benefits are, how will these be communicated up front?’.

The disadvantage of adding an additional interface for personal records management was expressed by participants as follows:

‘It would be a great way to manage this information and I think it has great potential as a service as in either a separate app or through major email providers like Gmail’.

‘The value-add on top of just getting bills is exciting, disadvantages include not being fully integrated with other apps like Gmail and the calendar’.

Findings suggest creating a clear ‘to-do’ list in conjunction with in-bound email was expected to reduce oversights, however the interface for this may be better integrated with an existing tool such as the email in-box or a calendar.

The notion of categorizing records or sorting records, whether they be in email or files saved on a computer or in the cloud was understood, but not necessarily practiced by all participants. Eight of the participants already sorted records into folders in their email and six of the 18 participants sorted records into folders on a computer, while all participants agreed that the application ‘would help me re-find records when I need them’. Participants were not initially convinced of the benefits of the potentially laborious task of categorizing records:

‘Useful idea, would be a great advance on how I do things currently. Automatic categorization of bills and documents strikes me as the most useful feature, but I need to use the prototype to provide better feedback’.

‘Benefit would be saving of time, improving access to historical records. Has to be simple to learn. Categorization has to work well’.

The benefits of categorization became clear to the participants when they were shown the service providers summary screen (Fig. 2). The attraction of the service providers and subscriptions table was that it brought together and summarized expenditure by service provider and subscription service provider. Eleven of the 18 participants agreed that the application would help ‘track my expenses’. This feature gave rise to thoughts of better budgeting and financial planning, as expressed by this comment:

‘I like the idea of how it lays out everything you know so like you know your brain can actually visualize where your money’s going because like if you put in an email and you put it in a folder, I’m not necessarily looking at it in the whole wider context of how much I’ve got to pay. I’m just ticking box, I’ve got to sort this, I’ve got to sort that. When you actually look at it oh wow, I am actually spending X thousands on entertainment a year, it’s just automatic’.

Participants in the third group commented:

‘The running total is super handy’.

‘It requires effort, but that effort collects it in a way that when I, you need it, when you need quick access, when you want to see the bottom line, it’s right there’.

‘[The]main advantage for me is tracking expenses and income with category totals etc. being able to be forwarded to my accountant’.

Similarly, although to a lesser degree (10 of the 18 participants), participants in this trial expected that a smart personal electronic records application could save costs, particularly by bringing excessive or unnecessary expenditure to their attention. Several participants in the software labs saw the benefit of monitoring ongoing subscriptions and expenses that might otherwise be overlooked.

The prototype demonstrated to users an effective logic to categorizing personal records by category and according to the service provider. Only one participant disagreed that the application would help them organize their personal records, and that was because that individual already categorized their records in their preferred distinctive way. Participants were attracted to this approach but raised concerns about the burden of categorizing records in the way that the prototype prescribed. While the prototype did not resolve this requirement, it succeeded in showing to users both the logic applied to categorizing personal records, and the outcome achieved.

With regards to the second objective to improve personal records management by ‘making it easier’, participants reported that the application made some aspects of personal records management easier, but made others more difficult. For example, the prototype automatically retrieved and saved many records sent to participants by a hyperlink in an email which participants might otherwise not save locally. Fifteen participants agreed that this would ‘help retain records that are not sent to me as email attachments’. However, participants found the task of categorizing records was excessively burdensome. This concern was expressed by comments made in response to a question about negative aspects of the application:

‘Initial time in the set up and time learning a new program’.

‘Somewhat time consuming but you should end up with easily accessible files’.

‘Just the time required to enter the categories and details initially, but I think that would be a positive’.

Conversely, participants who envisioned an automated version of the application were drawn to having their personal records categorized:

‘The categorization seems like a particularly useful feature, particularly as it is largely automatic’.

Findings suggest the categorization of records needs to be made simpler and easier with further automation: [Edited: Original was ‘The findings indicate that the categorization of records needs to be made simpler and easier with further automation:’]

‘Make it as simple as possible… so that I don’t stumble of which categories I put it in, or which sub-categories or whatever… make it simple, make it do as much as possible without you having to think too much about it… I think the idea is great’.

Measured against the objective of making personal records management easier, the prototype fell short for many participants because of the burden of having to forward emails and categorize records within the application. Only a few of the participants in this stage of the research already categorized their personal records, meaning that for the balance, adopting the application as their personal records management system would increase the amount of time spent managing their personal records and affairs. A successful personal electronic records management system would need to be smarter than this prototype, automating nearly all of the records saving and categorizing processes, as well as being simpler to use and interrogate, and would also need to be integrated into other applications such as email and calendars, in order to reduce the need to learn and adopt a new application and consult multiple applications for a single task.

Participant feedback indicated that there was a need for flexibility in the use of a PERM application from three perspectives; the ability to add features, the flexibility to only use some features and the ability to modify how the application does certain tasks.

Illustrating the need for the flexibility to add features, participants in the software trial also discussed the inclusion of more complex personal record formats. For example, participants were shown a record that comprised a table of dinner guests at dinner parties, and what they were served, the purpose of which was to avoid serving the same dish to the same person twice. Responses were as follows:

‘That’s amazing because my mum did that so she made sure she never gave the same menu to the same people ever’.

‘Wow!’.

‘It never occurred to me that I would forget that. That would really help me’.

This evokes an additional potential for a PERM application comprising the ability for users or other software developers to create a wide range of templates as ideas to inspire people to grow their record keeping.

Conversely, the demand for flexibility to only use some parts of the application is illustrated by this comment:

‘I just tend to leave everything in my email in-box, then I look through if there’s anything. But one thing I do print out is all my donations, because then the person that does my tax, I can give him the hardcopy, but in that case, I can put them all in here, because you get a receipt for every one of those donations… then you would have them all ready, in which case I wouldn’t have to remember, did I print this already, how I do it at the moment I keep it as an unopened mail so that I remember… so this is a really good way of organizing those, because you can mail them, create your donations category, then everything’s there when you need it’.

In other cases, participants had preferred ways of doing things. For example, this participant already had a preferred naming convention for their records:

‘The prototype has different naming conventions, getting the name in the way you like it, that would be a big plus’.

This indicates that a smart personal electronic records management application would benefit from maximizing flexibility to offer the opportunity to add functionality and use the software selectively and to alter software settings, for example to choose their own file naming conventions for the software.

The two issues of privacy and security were raised in discussion during the research. When asked, ‘what concerns do you have?’, a participant said:

‘Privacy is obviously one of those, and that I would lose documents… currently the way that I have got is tenuous anyway…’.

A similar comment was recorded in the questionnaire administered at the end of the research:

‘I think it would ensure quick access and avoid me losing track of bills and other documents. The downside would be honing-in on the best system of categorization to ensure I can keep track of things effectively. Also, would need guarantees on privacy and safety’.

Privacy concerns were also raised spontaneously by a participant as follows:

‘I have some pretty significant security concerns putting my bills and personal information in a third-party service that I’m not comfortable with. Like there’s a certain element of being within the sort of either Google sphere or one of those big names is that you kind of rely on their security abilities and also to keep it in within one- world minimizes the amount of information that’s kind of being shared and dispersed… I think that’s what would make people lean more towards [the prototype] being within another existing program instead of being a sort of stand-alone item’.

Concerns about security and privacy is often addressed in two ways. First, by providing clear information about privacy compliance and a process for contacting the software supplier about privacy and information about the applications security protocols. Secondly, by embedding some aspects, or all the application within some other trusted application, such as a Google or Microsoft product.

Regarding the first objective of ‘avoiding oversights’, the prototype improved users’ ability to locate records both within and outside the application through folder categories and file names. While participants in the research could find individual items by searching within their email, the prototype simplified the process of finding groups or combinations of records based on search criteria. Additionally, the prototype enhanced record retention by providing hyperlinks in emails instead of attachments.

The results indicate that an application that provides a ‘to-do’ list reflecting incoming emails requiring actions such as bill payments would be beneficial and achievable, although not in the manner tested in this case. The creation of a ‘to-do’ list within the prototype seemed to increase the burden of personal records management rather than reducing it. Moreover, forwarding emails to the application did not directly influence email inbox management. In hindsight, it is evident that improving email management requires a process integrated within the email application itself, rather than developing a separate application. To motivate users to use their email inbox as a ‘to-do’ list, an application would need to be fully integrated with the user’s email management system.

The prototype’s most significant contribution to reducing oversights in personal records management lies in avoidance of overlooking bill payments, checking subscription renewals and other aspects of personal records management that relate to the bigger picture, such as seeing records in context and in time series. The table of service providers and subscriptions in the prototype was perceived as the most valuable feature by participants since it presented the content of records in a user-friendly way, helping with budgeting and planning for upcoming expenditures.

Regarding the second objective of making personal records management easier, the prototype simplified some aspects while making others more challenging. The prototype organized and categorized personal records using intuitive categorization of records and grouping by service providers. Users were attracted to this approach but expressed concerns about the burden of categorizing records in the application. While the prototype did not fully address this requirement, it successfully showcased the logic behind record categorization and the resulting outcomes. A key insight from the trial is the necessity for future smart personal records management applications to automate and simplify the process, particularly in the context of the growing number of applications using generative artificial intelligence for self-organizing information (Jilek et al., 2023). An aspect of achieving the ‘making it easier’ objective was to ensure that the personal records management system reduced the amount of time users needed to spend managing their personal affairs (Balogh et al., 2024). However, the findings from the trial suggest that the current version may not achieve this goal. Only a few participants in this research stage already categorized their personal records, meaning that for most users, adopting an application as their personal records management system would increase the time spent managing their records and affairs. The comment made by one participant captures the potential value of an application if it ‘lays out everything you … in the whole wider context …. I’ve got to sort this… I’ve got to sort that’. This comment suggests that the focus of personal records management at home may need to be on those records’ content, over and above their format. Potentially, if the required information that people need were extracted from those records, there may be less concern about where and how the records are stored, which has been the subject of prior PIM studies (Dinneen and Julien, 2019; Grbovic et al., 2014; Oh, 2012; Whittaker et al., 2011). One reason why this may be more achievable for personal records at home than for the broader catchment of PIM research is that identifying the information that people need in the home context may be easier than doing so with regards to records relating to workplaces or study.

The findings suggest that this version of the prototype is likely to be just one of multiple iterations in the development of a PERM application. Future versions will need to be tested to ensure that they reduce the burden of inputting information, and that the application integrates with other software, particularly email, more smoothly. Artificial intelligence could be used to automate the records input and particularly the categorization of records. Experimentation and research will be required to ensure that automated categorization works for individual user needs. Integrating into existing software could make the application transparent to users. It may be possible for most of the software to function in the background of other applications such as email or file management applications. Further experimentation may determine whether the essential user interface components such as the expenditure summary table and the task reminders would be best presented in an application such as this or integrated into tools that users are already using.

The participants in this software trial recognized the benefits of a smart personal electronic records application, particularly through cost savings by identifying excessive or unnecessary expenses. The feedback gathered during the research strongly emphasized that an effective personal records management system can significantly assist participants in managing their expenses and budgets. Both the software lab discussions and questionnaire responses revealed that participants recognized the value of having their expenses summarized, as demonstrated by the prototype’s service providers and subscriptions table. They expressed that this feature would provide clarity on their spending habits and aid in highlighting excessive or unnecessary expenditure.

One function of PERM comprises ‘to-do’ management, encompassing practical tasks such as bill payments, insurance policy renewals, and others, as well as tasks aimed at ensuring easy retrieval of records. This aspect ensures that necessary tasks are not overlooked and provides advance notice of expected future items. However, participants expressed a strong preference for incorporating their ‘to-do’ list into applications that they are already using, such as email or a calendar. The challenge lies in finding a method to achieve this integration without making outstanding tasks overly conspicuous.

Secondly, regardless of where or how records are saved, it is crucial to ensure that people can easily retrieve the required records, even when they haven’t anticipated the need for them. This particularly applies to sets of records that should form a comprehensive compendium, particularly when users may have forgotten or be unaware of all the records that should be included.

Thirdly, a PERM application offers significant user value by generating awareness of things that users would not typically track. By extracting the information from personal electronic records, this kind of application can provide insights into spending patterns across various services and forecast future costs. There is also room for innovative ideas, as illustrated by the example of keeping a record of dishes served at dinner parties. Prompts like this can motivate individuals to manage their personal records in a way that better prepares them for unforeseen future requirements, even if they are not consciously aware that the system is facilitating such preparedness. The development of PERM applications could lead to a wide range of new tools that enhance everyday life and make personal records management more convenient.

Finally, the limitations of a PERM application also need to be recognized. An application to assist in personal electronic records management may not provide a complete solution. The question arises as to whether the participants would have perceived the prototype in the same way had they not been introduced to it in the trial and discussed their PERM issues in the process. If the experience of the software labs contributed to improved personal records management, then this would suggest that achieving the goals of reduced pain-points and oversights in PERM might be better achieved by a combination of an application and training, the latter of which could improve awareness of problems and clarify the practices that can result in more satisfactory outcomes. The application itself needs to operate more transparently in the background, automating the input and categorization functions while providing users with the benefits of the information summary and task reminders.

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the correspondence author upon reasonable request.

MB: Prototype design and development, research design, conduct, analysis, data curation and draft paper. WB: Advice, supervision, review and editing. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Associate Professor David Paul of the University of New England, NSW, Australia and Adjunct Associate Professor Mary Anne Kennan of Charles Sturt University, NSW Australia.

This work is partially funded by an Australian Government Research Training Program Stipend Scholarship (RTP) granted to Matt Balogh on the 25th November 2019, which paid for his research doctorate degree tuition fees at the University of New England for a period of three years.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.