1 Chinese Academy of Science and Education Evaluation, Hangzhou Dianzi University, 310018 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 School of Information Resource Management, Renmin University of China, 100872 Beijing, China

Abstract

This study presents a new framework for building rich, digital profiles of Chinese researchers by using ontology technology to organize and connect information from various online sources. The system, called POAS (Persona-of-a-Scientist), combines semantic technologies, natural language processing, and linked data standards to bring together scattered academic data into a structured and accessible knowledge base. Key elements of scholar profiles were identified through interviews and literature reviews, providing a strong foundation for the model. The platform supports open access, semantic search, and personalized recommendations, helping to improve data sharing, academic collaboration, and the development of intelligent, knowledge-based research services.

Keywords

- ontology modeling

- ontology mapping

- digital user profile

- heterogeneous information integration

The vast networked resources in the era of big data have posed significant challenges to digital engineering and digital library initiatives. In addition to substantial investments by traditional academic service institutions—such as university libraries, public libraries, and archives—large-scale national and international digital literature and storage projects have gained increasing attention and government support in recent years. Supported by such initiatives, projects like the “Chinese Memory Project”, which aims to preserve traditional cultural heritage, and the “Internet Archive Project”, a global nonprofit archival effort, have developed rapidly (Lin et al, 2017). At the same time, institutions are increasingly recognizing that, beyond the digitization of literature, the integration and construction of networked personal virtual archives is equally vital. Scholars such as Genoni (2005) argue that academic online profiles are essential for communicating researchers’ professional expertise and scholarly achievements. From a national strategic perspective, the management of scientific researchers plays a critical role in enhancing international competitiveness and driving technological innovation. Therefore, the organization, archiving, and standardized digital management of academic materials is of growing importance.

However, compared with progress in digital resource construction and related research, the challenge of implementing scientific, personalized, and user-friendly knowledge management for research datasupporting academic search, intelligent recommendations, and research services—remains largely unresolved. According to Dagienė (2016), although the vast majority of respondents are employed by formal academic institutions (e.g., universities, research institutes, libraries), only 32.5% of these organizations actively manage and maintain records of their scientific work. Additionally, nearly a quarter of respondents reported relying solely on third-party platforms, such as Microsoft Academic, for academic record management. These findings highlight a key issue: academic information and research data are widely dispersed across various internet service platforms, lacking effective integration and centralization.

Open data, as a global trend, emphasizes the sharing and reuse of information across various platforms and sectors. It promotes transparency, collaboration, and innovation by making data accessible to a wider audience (Laurila et al, 2012; Piwowar and Vision, 2013). In the academic context, open data facilitates the integration and aggregation of dispersed scholarly information, enabling more comprehensive and accurate representations of researchers’ activities and achievements (Faniel et al, 2013). However, despite the growing availability of open data, its integration and application in academia remain challenging. The fragmented nature of scholarly information and research data across internet platforms continues to hinder the development of holistic academic profiles (Tenopir et al, 2011). This limitation highlights the need for effective tools and methodologies to manage and integrate heterogeneous data sources.

In response, this research introduces ontology-based technologies to semantically organize and reconstruct academic portrait data for Chinese scholars. Taking selected prominent Chinese scientists as examples, we construct a resource database that integrates heterogeneous data from various online platforms and systems, encompassing key dimensions of academic profiles. Through interview analysis, critical attributes are extracted and used to develop a unified ontology-based conceptual model, enabling a standardized framework for describing academic portraits and structuring knowledge. Utilizing an automated ontology mapping and transformation process, the system converts multidimensional scholar information into an ontologized academic knowledge base. This knowledge base provides a robust foundation for semantic search, personalized recommendation, question answering, expert identification services, and even applications in big data-driven medical research.

Domestic and international large-scale digital library projects are increasingly focusing on the organization and management of data resources related to researchers and their academic activities. These projects often emphasize the categorization and semantic management of research outputs, primarily through the standardized annotation of metadata for core knowledge units—such as journal articles, bibliographic records, and conference proceedings—as well as through efforts in e-publishing, open access, and the digital storage of research and teaching materials. To enrich metadata structures and functional requirements, the UK Joint Information Systems Committee, in collaboration with Dublin Core (DC) and Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) proposed the Scholarly Works Application Profile (SWAP), an ontology framework designed to characterize scholarly texts and support navigation and access to different preprint versions (Allinson, 2008). Peroni et al. (2012) advanced this effort by integrating the Dublin Core metadata model with FRBR-aligned Bibliographic Ontology (FaBiO) and Citation Typing Ontology (CiTO) vocabularies to address the lack of standardized semantic relationships between document descriptions and citation networks in scholarly publishing. Their approach promotes the integration of heterogeneous document formats and citation data into a unified schema. In Brazil, the “Health 360 Project” at the United University of São Paulo constructs comprehensive academic profiles of researchers using the Linked Open Data (LOD) Cloud. This initiative employs multiple Resource Description Framework (RDF) ontologies—such as Academic Institution Internal Structure Ontology (AIISO), Research Organization Registry Vocabulary (ROV), and Organization Ontology (ORG)—to model research roles, organizational structures, project descriptions, and temporal participation attributes. The project systematically categorizes data from scientists’ homepages into four key areas: personal information, professional background, academic achievements, and published works (Teixeira et al, 2016). Other projects include Electronic Theses and Dissertations (ETD), a digital thesis and dissertation archiving standard developed by McGill University Library in Canada (Park and Richard, 2011), and the VIVO family of ontologies, a Linked Data standard for semantically integrating a range of research entities—such as researchers, resource products, grants, and events—by reusing ontologies like Dublin Core, Friend of a Friend (FOAF), Bibliographic Ontology (Bibo), and Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS) (Chambers et al, 2013).

Additionally, several studies focus on the evaluation and measurement analysis of researchers and their institutional affiliations. This includes research on co-authorship networks, scientometric services, citation analysis, and domain knowledge visualization systems. For example, Costas et al. (2010) explores a range of individual-level bibliometric indicators—such as publication count, total citations, h-index, percentage of highly cited papers, and journal impact factor metrics—and highlights their importance in understanding academic research behaviors. These metrics can support policy makers and research administrators in developing collaboration strategies, identifying potential research teams, and modeling factors influencing scientific output. Hwang et al. (2010) explore the construction of a recommendation and retrieval system for academic literature based on author co-authorship networks. Compared to international research, Chinese intelligence research is noted for its diversityand theoretical orientation, while international efforts often emphasize refined, practical applications (Ma et al, 2009).

Web-based media and services have significantly diversified and enhanced access to scholarly materials and digital archives. The rise of powerful academic search engines, alternative metrics frameworks, and scholarly social networking platforms has drawn increasing attention within the academic community. Research shows that academic social media platforms enable scholars to build and maintain personal academic profiles, thereby increasing the visibility and public impact of their work through rapid online dissemination and scholarly interaction. However, this impact varies across different social media platforms and should be seen as complementary to traditional citation-based metrics. For example, Ortega’s studies (2013; 2015b) on research institutions within the Google Scholar Collaboration Network indicate that personal social profiling can elevate a scholar’s visibility, enhance academic competitiveness, and potentially contribute to future recognition and research opportunities. While social media platforms showcase scientific publications, career milestones, and technical expertise—improving the reach and communicability of research findings (Vainio and Holmberg, 2017)—Thelwall and Kousha (2014) found that platforms with an explicitly academic focus attract more scholarly engagement than general platforms like Twitter. This trend is especially pronounced in the humanities, where ideologies, literature, and research findings are commonly shared and discussed. By comparing various academic platforms, Ortega (2015a) observed that Microsoft Scholarship is particularly suitable for interdisciplinary institutional-level research, with a focus on computer science, albeit with slower database updates. In contrast, Google Scholar offers more comprehensive citation data and a broader scope of scholarly materials, making it more appropriate for individual-level assessment, though it is more labor-intensive to process. Both platforms face technical limitations, including duplicate profiles, citation errors, and potential for manipulation (Ortega and Aguillo, 2014). Martín-Martín et al. (2018a) further demonstrated that Google Scholar’s inclusion of journals, conferences, bibliographies, and news sources allows for more nuanced and inclusive metrics. These alternative metrics offer a valuable supplement to conventional evaluations of academic impact. Nonetheless, Ortega (2015b) emphasized that while such alternative measures can indicate scientific popularity and networking strength, traditional citation metrics remain the most robust and consistent indicators of scholarly influence and academic contribution.

In addition, researchers have explored the behavioral preferences and information needs of scholars using academic social networking sites and search engines to better inform the development of digital academic portraits. Stvilia et al. (2018) conducted a survey examining the role of research information systems such as ExpertNet, Google Scholar, Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID), REACH NC, and ResearchGate. Their findings indicate that most researchers use these platforms primarily to search for and discover scholarly papers, while fewer use them to seek collaborators or participate in Q&A activities. Active sharing and self-promotion of research were limited, and usage patterns varied significantly across academic disciplines. Similarly, Nández et al. (2013) emphasized that a defining feature of academic social networks is the formation of user connections. As scholars update their profiles—such as by uploading publications on platforms like Academia.edu—they can monitor peers’ activities and receive system-generated notifications, allowing them to stay informed about emerging research trends and academic developments.

At the application service level, one of the primary goals of academic profiling is to establish a unified and standardized database framework for academic knowledge management. This includes not only efficient and accessible data services but also semantically enriched data interfaces, academic support platforms, and service systems tailored to the needs of researchers. A prominent example is Academic Knowledge Mapping, a cutting-edge research area. AMiner, developed by the Knowledge Engineering Research Laboratory at Tsinghua University’s Department of Computer Science and Technology, is one of the most influential academic profiling platforms in China. It integrates multidimensional academic profiles—including metadata from 155 million papers and over 60 million semantic academic relationships across international publications in computer science, expert archives, and citation indexes. Through data mining and knowledge integration techniques, AMiner addresses challenges such as name disambiguation, heterogeneous textual metadata, and linking academic relationships to construct a comprehensive knowledge graph. This forms the basis of its open sharing interface, SciKG (Science Knowledge Graph) (Tang, 2016). Similarly, the Acemap team at Shanghai Jiao Tong University developed AceKG, a nearly 100GB academic knowledge graph for computer science, by integrating major international databases such as Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), and Digital Bibliography & Library Project (DBLP) (Wang et al, 2018). In terms of recommendation services based on academic profiles, Uddin et al. (2013) constructed an Academic Knowledge Base (AKB) using multi-layered metadata and combined scholar co-authorship networks with topic networks to rank and recommend experts. Their results show that weighted academic portrait ontologies significantly improve the accuracy of literature retrieval systems (Uddin et al, 2013). Building on scholars’ background knowledge, Amini et al. (2014) categorized academic knowledge into thesis-related information (e.g., coursework and learning concepts), research projects, academic web content, research directions, and demographic attributes. Their empirical studies demonstrated that reusing intermediate-level ontologies and integrating heterogeneous academic knowledge significantly improved feature selection performance. Further research by Amini et al., (2014). integrated multiple domain ontologies to build a more complete academic knowledge base, which served as an effective reference for scholar topic preferences and showed superior performance in recommendation tasks. Additional studies have also explored integrating semantic web crawlers with personalized recommendation engines (Yang, 2010) and profiling literature and journals for improved academic service delivery (Silva et al, 2015).

The concept of open data emerged during the early digital revolution, gaining traction in the 1990s with the rise of the Internet. Advocates like Tim Berners-Lee emphasized open data’s potential to foster a more connected web ecosystem. Open data breaks down disciplinary silos, enabling researchers from diverse fields to access and build on one another’s work, thereby enhancing transparency, reproducibility, and interdisciplinary collaboration (Terras, 2015; Faniel et al, 2013).

In the Digital Humanities (DH), open data has transformed methodologies for analyzing cultural heritage, textual corpora, and socio-historical trends. Projects like Europeana and Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) aggregate extensive historical and cultural data, providing DH scholars with valuable resources (Ciasullo et al, 2016; Petras et al, 2017). Semantic web technologies and linked open data (LOD) frameworks enhance interoperability, enabling scholars to query and visualize complex relationships across datasets (Hyvönen, 2019), supporting tasks like metadata extraction, sentiment analysis, and topic modeling (Daquino et al, 2017; Bucea, 2022).

As big data becomes integral to DH research, international platforms like the Stanford Humanities Center’s digital initiatives now support data integration, visualization, and collaboration (Ding and Li, 2019). However, in China, DH platforms remain underdeveloped, with systems like China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and the Shanghai Library’s Historical Archives, lacking semantic structuring and user-centric features (Xia, 2017; Smithies et al, 2019). This highlights the need to develop ontology-driven digital user profiles tailored to Chinese scholars.

To summarize, although substantial progress has been made by international scholars in the field of digital academic portraits, several important areas remain underdeveloped. These include challenges such as managing heterogeneous multi-platform academic profiles (Greifeneder et al, 2018; Martín-Martín et al, 2018b) and constructing multi-dimensional classification frameworks for academic personas (Arenas et al, 2014). For instance, Mikki et al. (2015) highlighted the growing trend of multi-platform academic presence, noting in their study that only 20% of researchers maintained a profile on a single platform, while 26% had dual profiles and 11% maintained profiles across five platforms. In contrast, research on digital academic portraits in China remains at a relatively early stage. Existing efforts, such as the development of academic databases (Xia, 2017), largely remain at the level of theoretical discussion and high-level system planning. There is still a lack of well-established theoretical models and practical applications grounded in standardized frameworks. A central aim of this study, therefore, is to address how diverse profile resources can be integrated to design a scientifically robust and comprehensive digital portrait model for Chinese scholars—one that captures the full range of academic attributes and activities.

Moreover, most existing academic profile resources—whether for scholars, e-commerce users, or other domains—are currently stored in closed relational database systems. These systems lack the capacity to support rich semantic knowledge services and intelligent applications such as academic search, personalized recommendation, expert discovery, or evaluation of research outputs. They also fall short in enabling semantic interoperability and integration across platforms, as envisioned by frameworks like Linked Data. To address these limitations, this study applies ontology technologies to semantically structure and reconstruct the profile data of Chinese researchers. By transforming this data into an annotated knowledge base, the project enables more efficient querying, semantic linking, and open access, thereby laying the groundwork for intelligent, knowledge-driven academic services.

To meet the growing demands of academic knowledge services and evaluation in increasingly complex and intelligent environments, this study proposes a multidimensional scholar portrait model. This model focuses on the systematic organization of data and knowledge related to researchers’ personal academic information, scholarly outputs, and academic activities. These features are categorized into two primary dimensions: the knowledge outcomes dimension, which is based on documentary resources, and the scholarly description dimension, which is based on personal and professional academic activities. The knowledge outcomes dimension encompasses tangible products of intellectual labor that have been validated by the academic community, such as theses, bibliographies, and patents. In contrast, the scholarly description dimension emphasizes aggregated information about a scholar’s educational background, research interests, project experience, and other activity-related data. Recognizing the growing significance of academic social behaviors in contemporary research practice, this study also incorporates a supplementary review of online academic social resources and their behavioral characteristics (e.g., blog activity and peer recommendations) to enhance and complement the core dimensions of the portrait model.

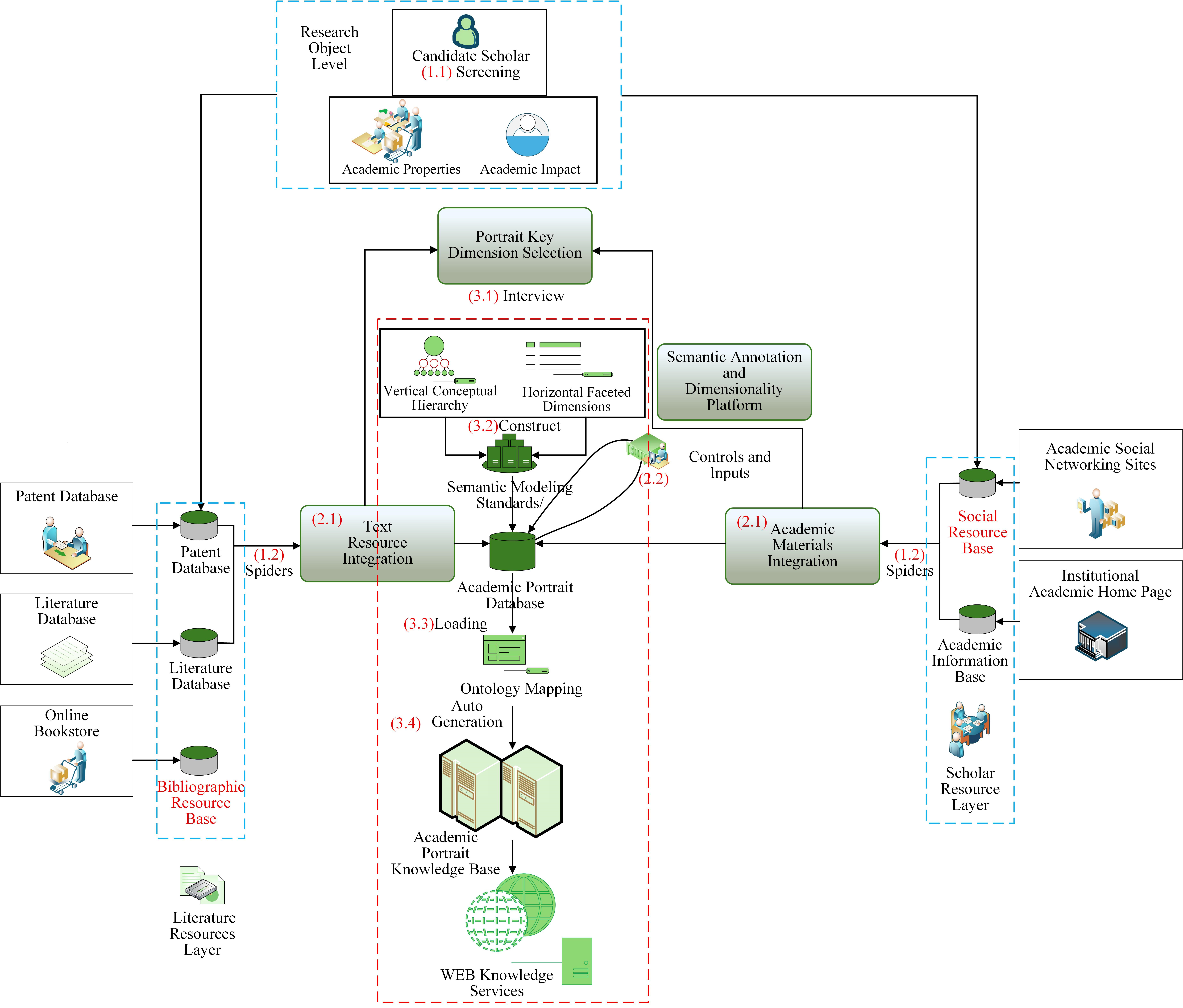

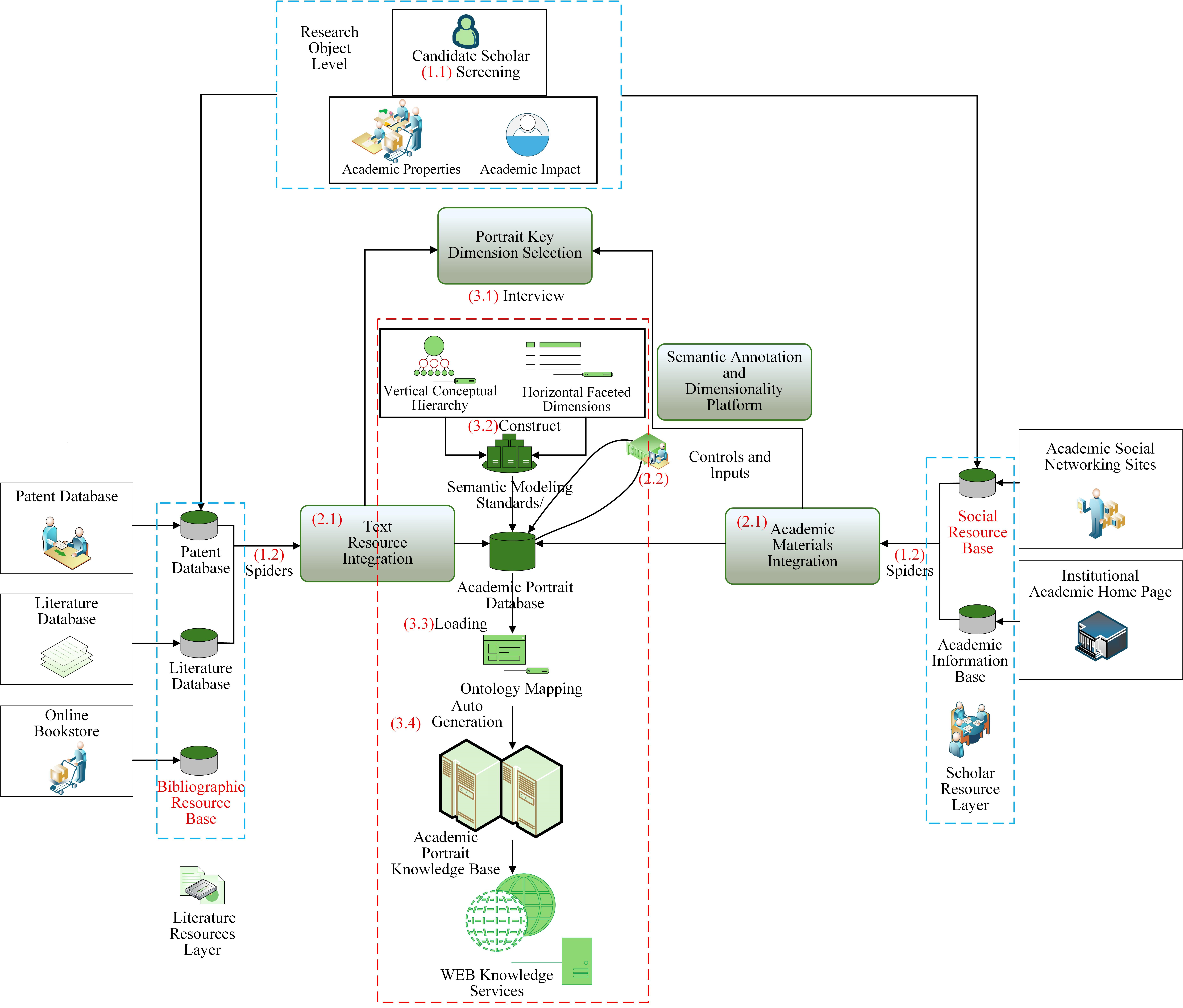

This study introduces a multidimensional academic portrait analysis framework that integrates data from heterogeneous platforms. The framework consists of two core components: the organization of multidimensional portrait data and the ontology-based structuring and delivery of knowledge services, as illustrated in Fig. 1 below.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Research framework for the construction of an academic portrait knowledge base for Chinese scientists.

In the multidimensional portrait data organization process, candidate scholars are initially selected based on their academic achievements and influence, as well as relevant attribute information (1.1). Scholar-related resources are then semi-automatically collected using distributed web crawling techniques and targeted acquisition strategies (1.2). Through heterogeneous information resource integration methods, data from multiple platforms are aggregated to form a two-tier resource repository: a literature resource layer (corresponding to the knowledge outcomes dimension) and a scholar resource layer (corresponding to the scholar description dimension). Natural language processing, data integration, and alignment technologies are applied to construct a foundational academic portrait database (2.1), which is subsequently refined through collaborative semantic annotation platforms that support manual proofreading and correction (2.2). Key dimensions of the academic portrait knowledge base are then extracted through face-to-face interviews (3.1).

For ontology-based knowledge organization and services, the conceptual structure of scholarly resources is developed using the key dimensions identified in step (3.1), followed by the design of a multilayered, faceted semantic framework (3.2). An automated ontology mapping system is employed to generate the academic portrait knowledge base (3.3, 3.4). Finally, RDF-formatted semantic records are published via web services, enabling Linked Data integration and semantic querying.

In this study, metadata extraction techniques are employed to parse elements

from acquired HyperText Markup Language (HTML) web pages to identify key

scientific research attributes. Subsequently, natural language processing methods

are used to segment the titles and abstracts of books, blogs, and journal

articles, enabling the construction of content-based features for scholars. To

address the challenge of author name disambiguation, a rule-based matching

algorithm is developed. This algorithm assumes a similarity score between two

authors with the same name

This study employed semi-structured, face-to-face interviews with randomly selected scientific researchers, each lasting approximately 30 to 60 minutes. Interviews were conducted at designated laboratory sites. One team member introduced the interview topics and guided the discussion, while another recorded key points, timestamps, and location details. During the data analysis phase, the study combined qualitative methods with quantitative analysis to identify key dimensional attributes of research scholars, which were then used to inform the structure of the academic portrait knowledge base.

In the conceptual modeling phase, the controlled vocabulary of multidimensional academic portrait variables was analyzed and extracted as classes, relationships, constraints, and factual rules. This process followed an ontology-based semantic conceptual modeling approach, as proposed by La-Ongsri et al. (2015). Using the “seven-step method”, a hierarchical system was developed to semantically describe various elements of scholars’ profiles, including demographic attributes, knowledge interests (Duong et al, 2010), and academic resource data. Where possible, existing ontologies such as FOAF, DC, and SKOS were reused to ensure interoperability and standardization in constructing the knowledge structure of Chinese scientific researchers’ profiles.

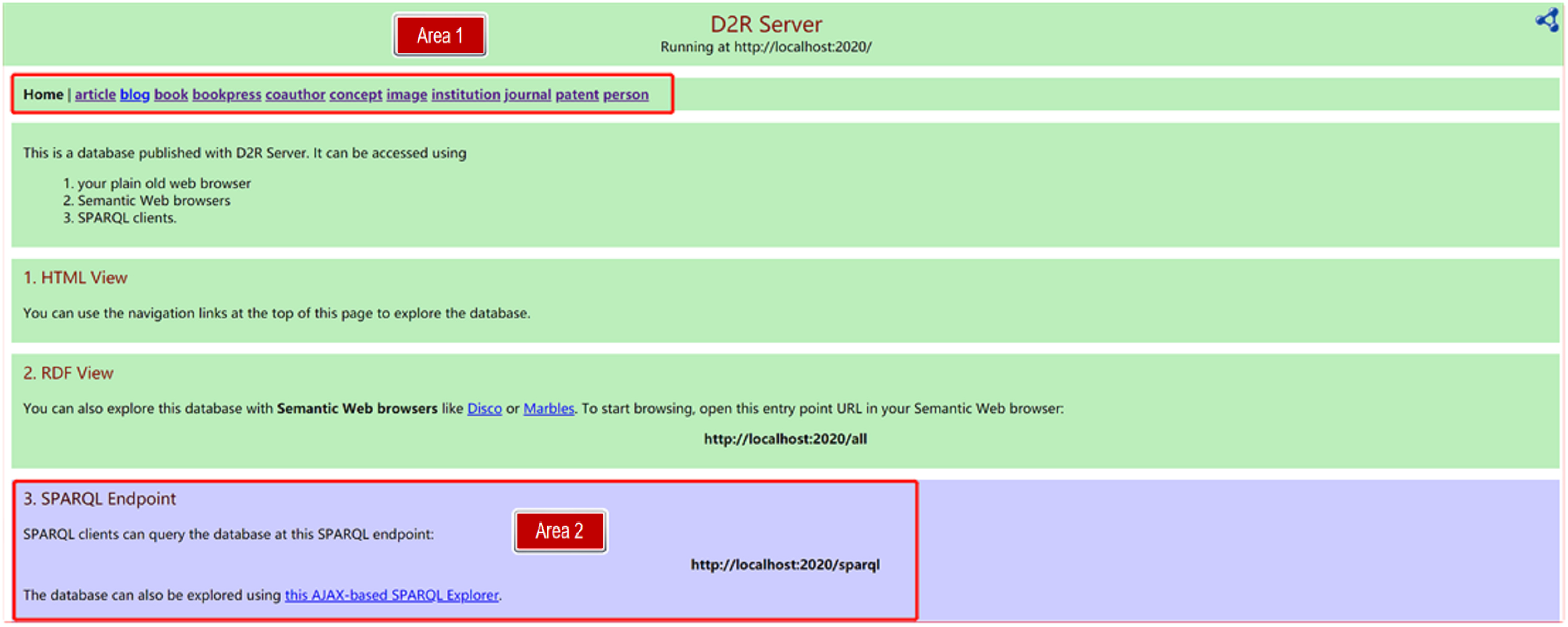

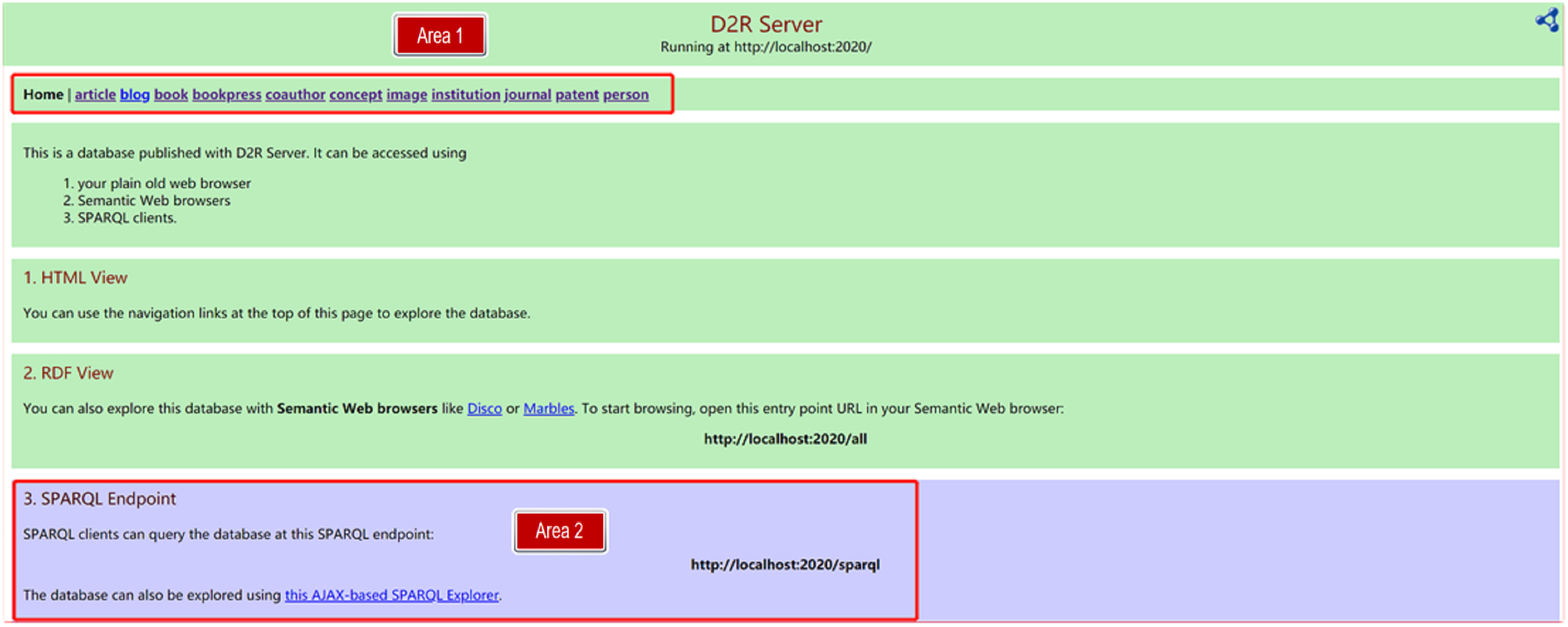

At the instance level, tables from the Academic Portrait Database were normalized into third normal form (3NF), with each table named after a corresponding ontology class and each column directly linked to a primary key. Resource Description Framework (RDF) format was automatically generated from these tables through conversion and mapping using the Database to RDF Query (D2RQ) platform. The resulting RDF data were published to support semantic querying of the Academic Portrait Knowledge Base, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In this figure, Area 1 provides a knowledge navigation interface for browsing entity categories and their associated metadata, while Area 2 offers a semantic query interface for retrieving detailed information.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

RDF (Resource Description Framework) data and semanticized query interface for academic portrait knowledge base. D2R, Database to RDF; SPARQL, SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language; HTML, Hyper Text Markup Language.

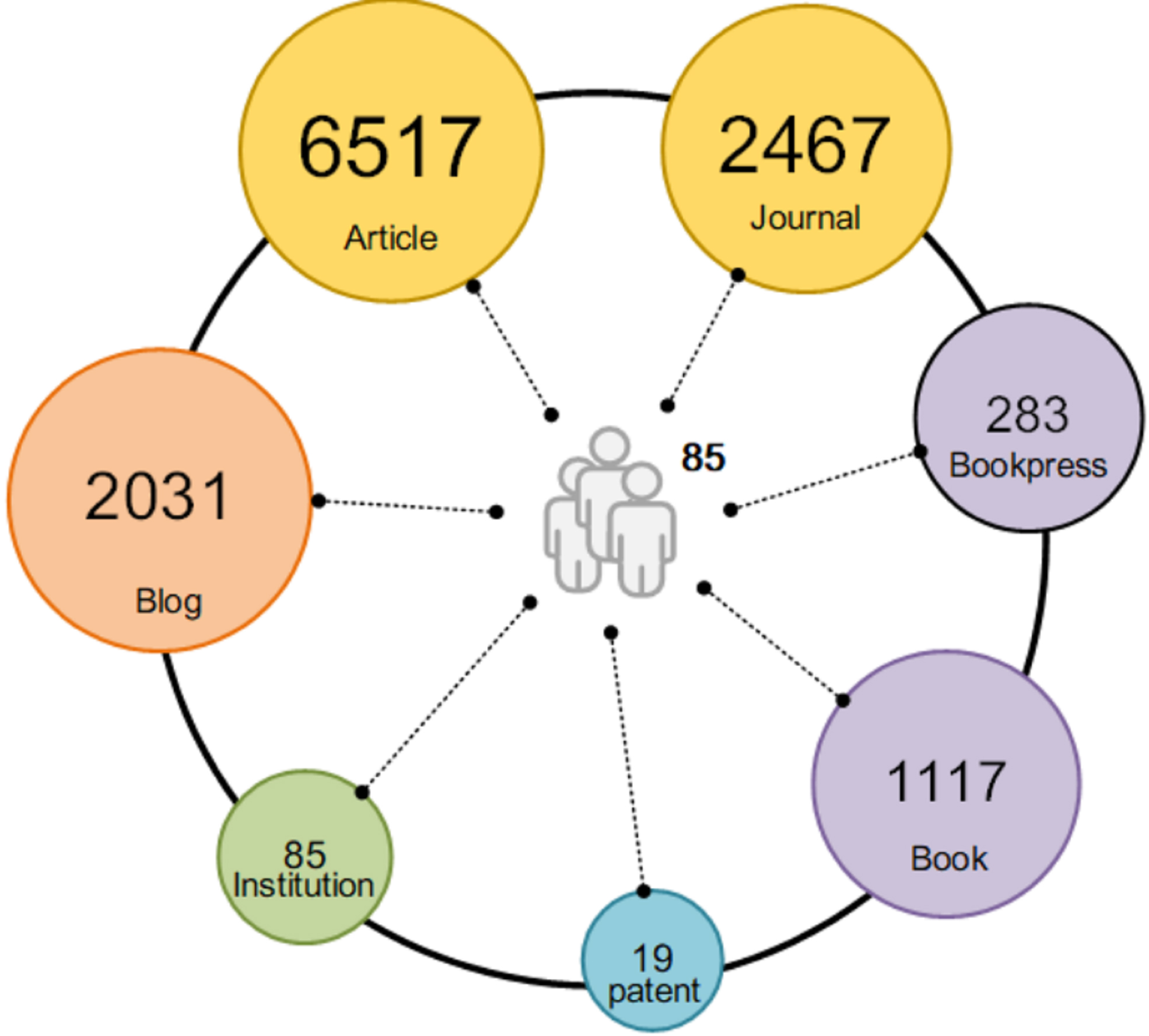

In this study, we began by collecting data from the social platform “‘Web of Chinese Science’ (WCS)”, initially focusing on members of the WCS blogger committee and their connections (see the sample profile as Fig. 3). Using a “snowball sampling” method, we gradually expanded the dataset to compile a preliminary pool of candidate scholars. To capture the portrait information of Chinese research scholars across different dimensions, we applied the following selection criteria: (1) holding the academic title of professor; (2) ranking in the top 20% in terms of online activity; (3) ranking in the top 20% in terms of publication count; (4) possessing a personal h-index greater than 10; and (5) having published at least 20 scholarly works. These criteria were chosen to ensure the inclusion of senior scholars with established academic status (professor title), active engagement with the broader community (online activity), consistent research productivity (publication count), and scholarly impact (h-index). The requirement of at least 20 publications ensures that each scholar has a substantial body of work to support meaningful analysis. Together, these dimensions reflect academic visibility, influence, and sustained contribution, making the sample suitable for drawing insights into the characteristics and patterns of leading Chinese researchers.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Sample Chinese researcher profile in Web of Chinese Science (WCS).

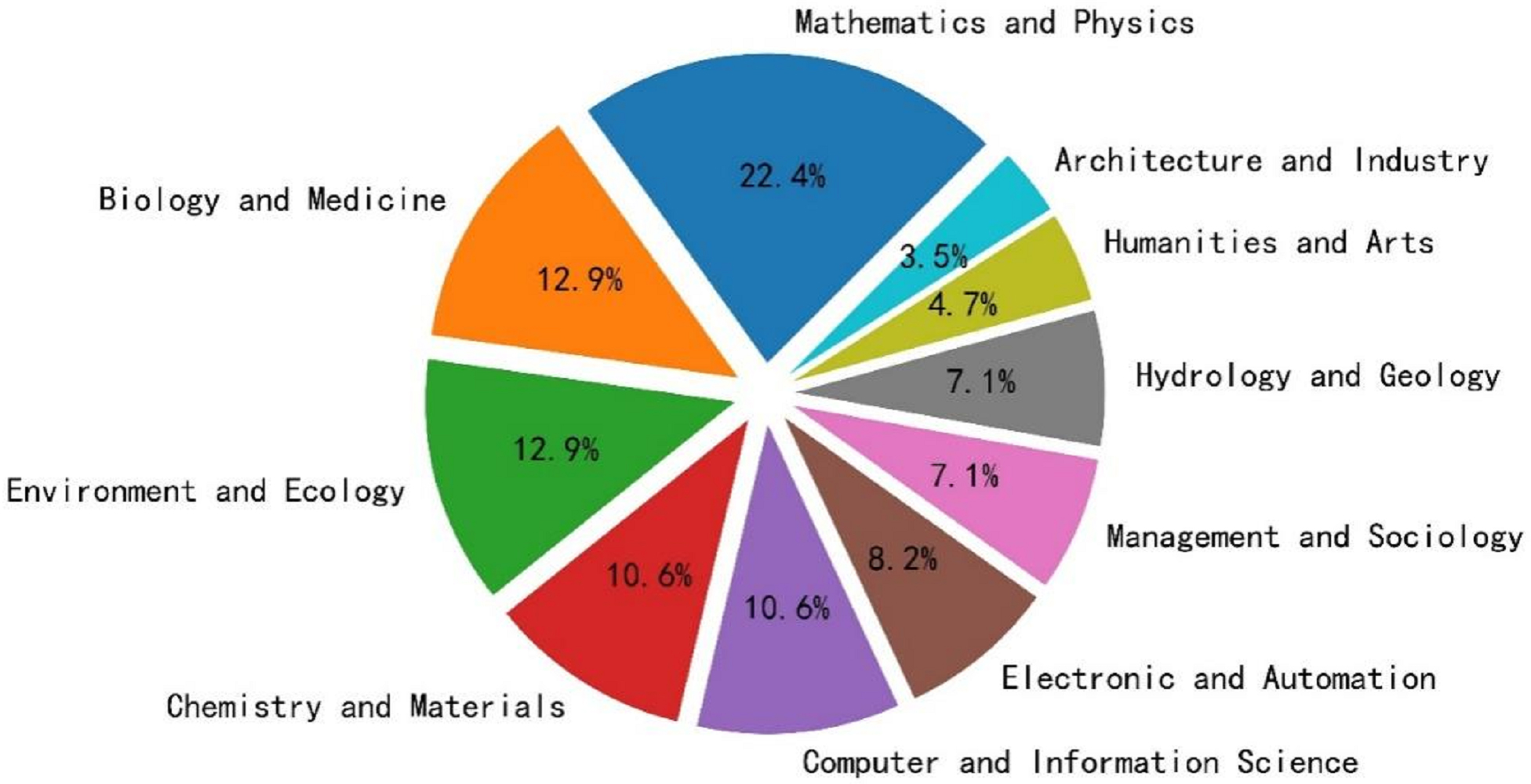

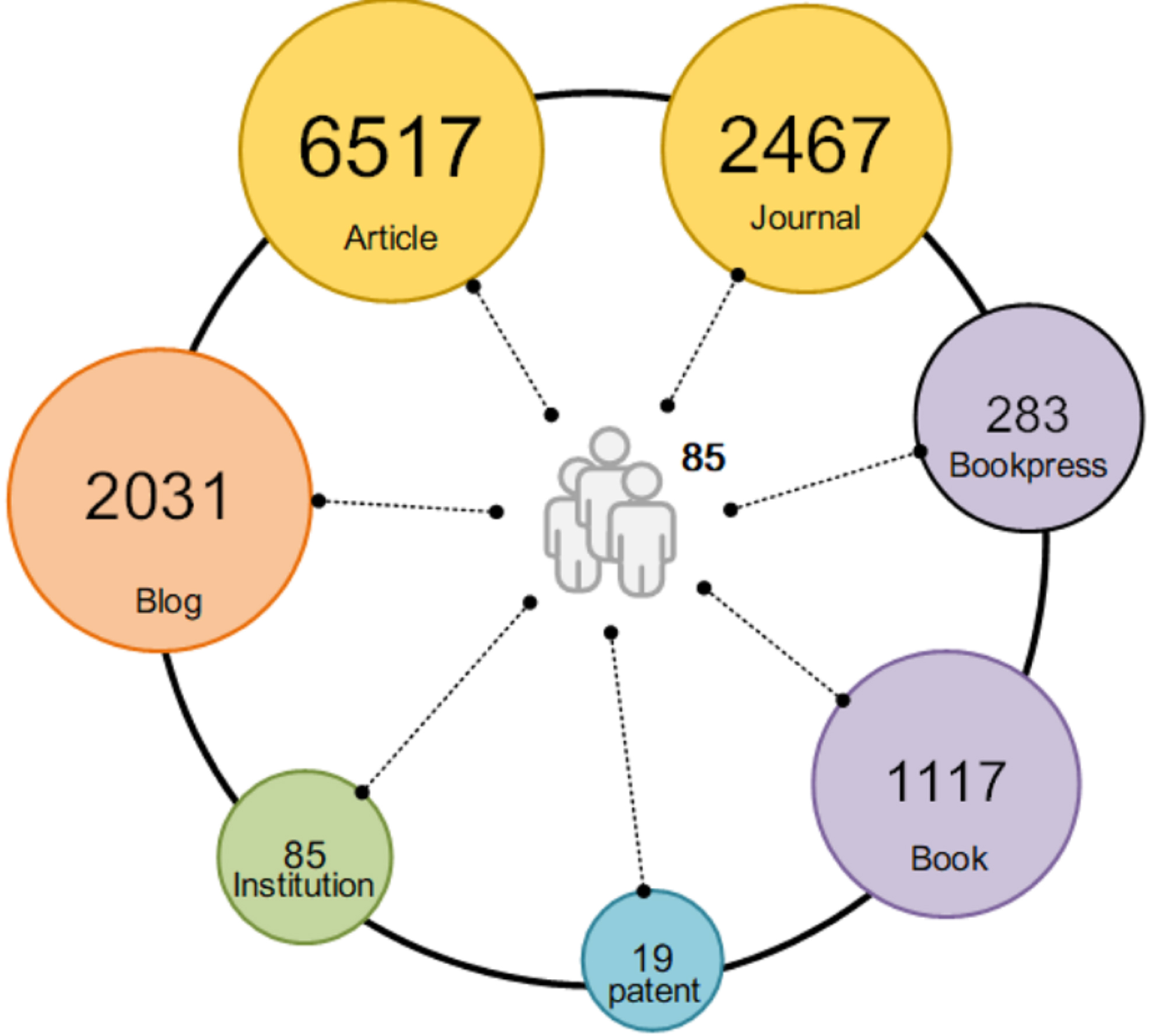

Based on the selection criteria, we identified an initial dataset of approximately 376 candidate scholars. All candidates were contacted and invited to verify the information retrieved from their profiles. However, only 85 scholars responded and agreed to participate in the data verification process. These 85 scholars constituted our final dataset, and their disciplinary backgrounds are illustrated in Fig. 4. To enrich the dataset, we collected supplementary information on these scholars from various sources, including Baidu Scholar (for academic publications), Dangdang.com (for book publications), personal academic websites, and publicly available patent records (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Representative Candidate Chinese scholars in different disciplines.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Descriptions of the proposed dataset.

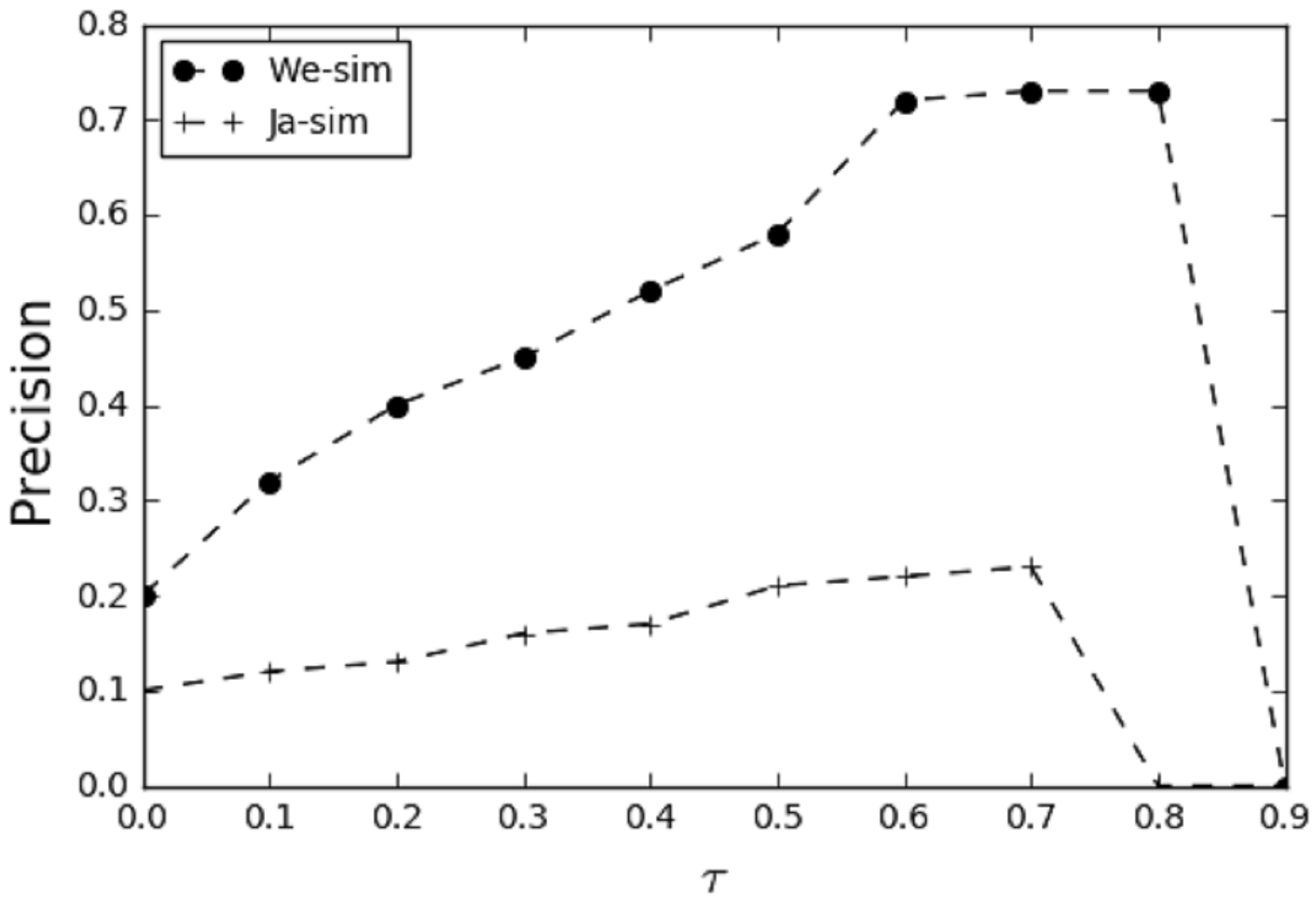

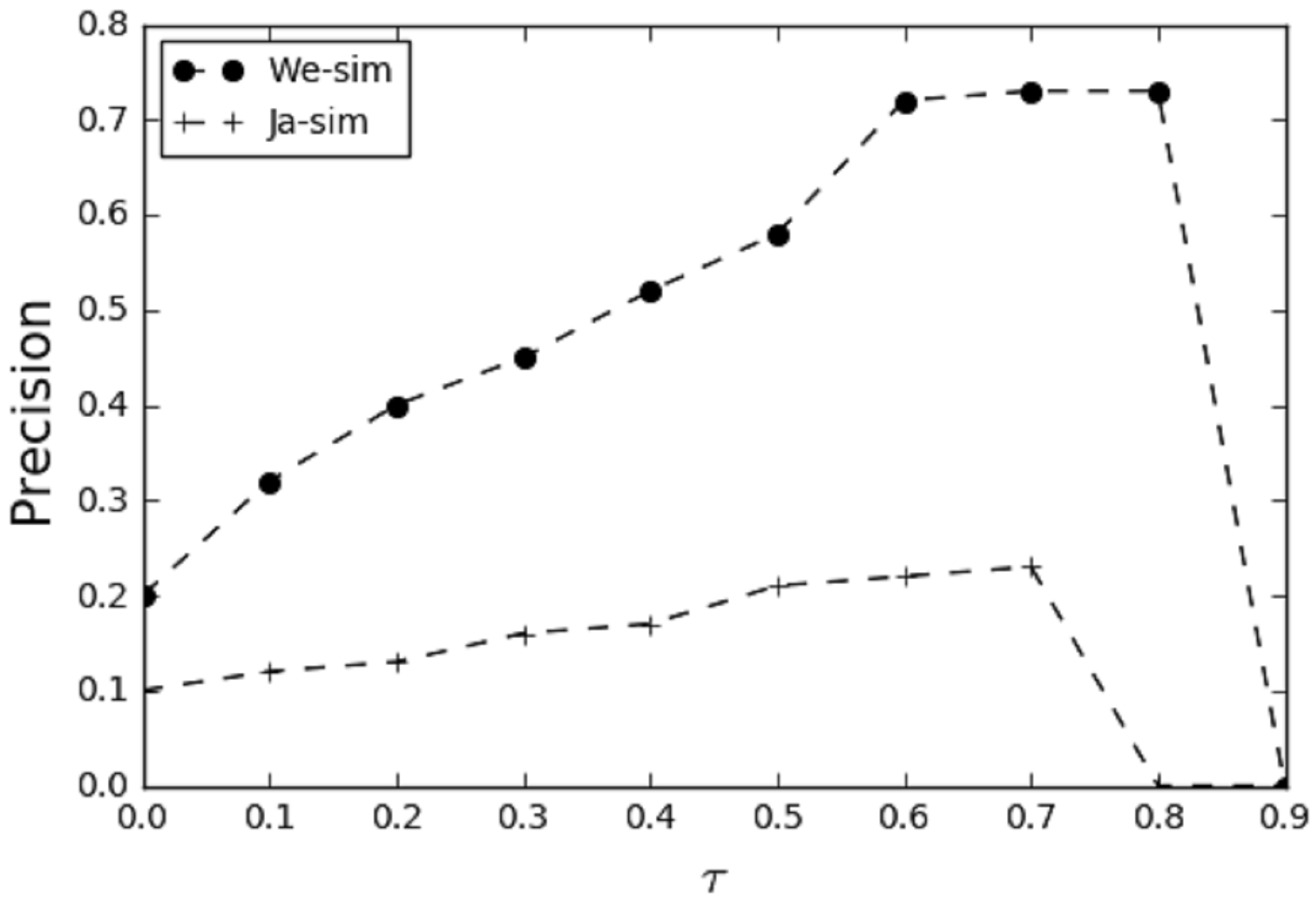

In the heuristic rule-based algorithm, this study employs two similarity

calculation methods for authorship disambiguation experiments. The first method

is keyword co-occurrence similarity, referred to as Jaccard similarity

(Ja-sim) (Niwattanakul et al, 2013). The second method utilizes

word embedding vector representations via Word Embedding Similarity (We-sim)

(Mikolov et al, 2013), which measures textual similarity by computing the

cosine similarity between the word embeddings of the two objects. For this model,

we used a 32-dimensional vector space, a contextual window size of 3, and the

skip-gram architecture. The accuracy results of both methods at various threshold

values (

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Correlation between We-sim and Ja-sim.

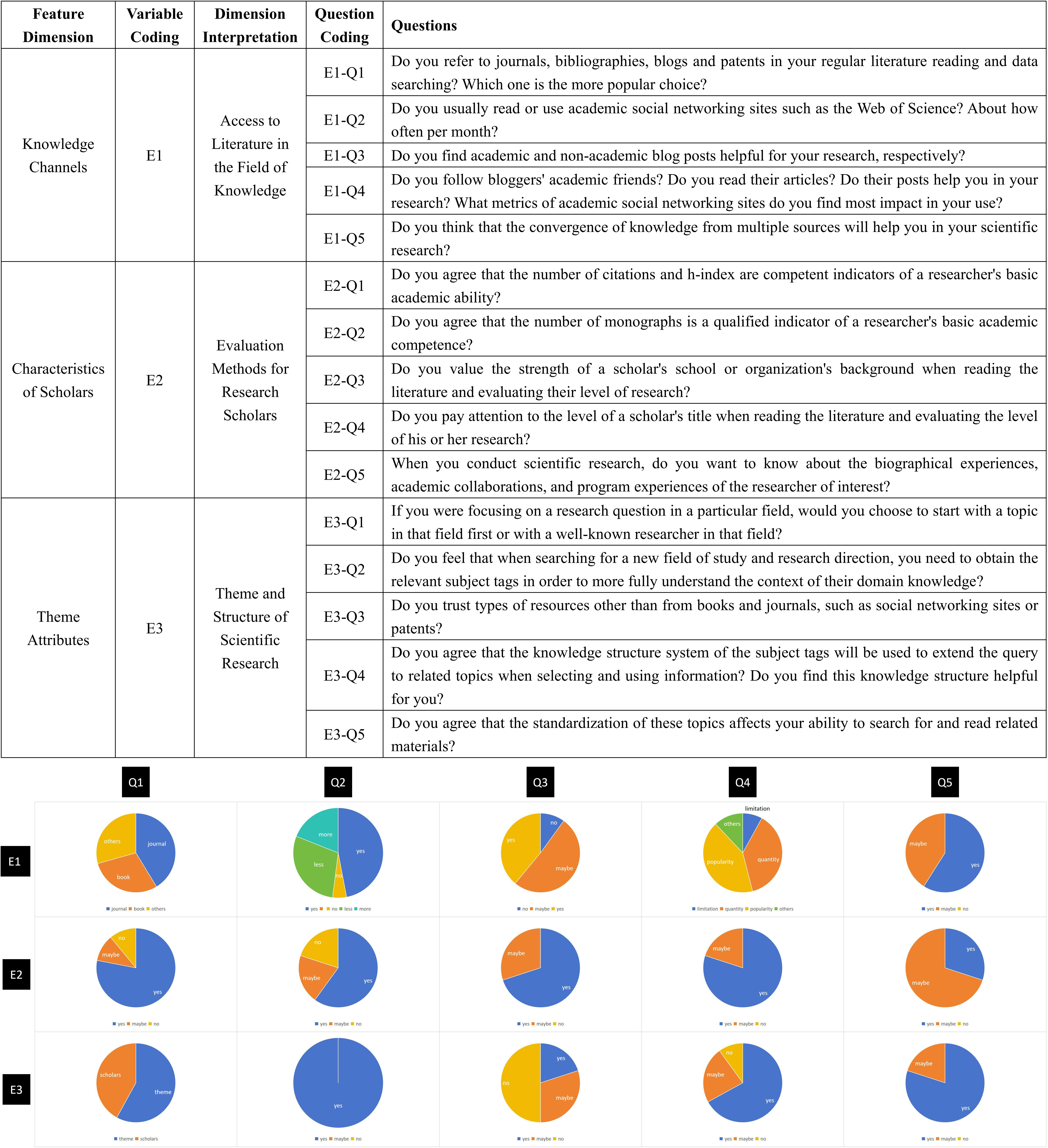

Based on the behavioral needs of scholars in their research activities, this study proposed an interview analysis process targeting the key features of academic portraits of Chinese scholars and classified the dimensions into three categories: knowledge channels, scholar characteristics, and topic attributes. For each category, five core questions were formulated. This process includes four steps as follows.

The first step involved developing a preliminary interview outline based on a review of relevant literature and an analysis of the research behaviors and activity patterns of Chinese scholars. To refine and validate this outline, four experts representing diverse disciplines (biochemistry, agricultural and forestry science, humanities and social sciences, and information management) were invited to discuss, revise, and finalize the interview framework.

In the second step, 50 active researchers were recruited from six universities across China. An initial screening was conducted using a pre-interview questionnaire designed to assess eligibility. This questionnaire collected demographic and background information, including age, education level, academic discipline, frequency of study and reading habits, and use of academic social networking platforms such as WCS. Scholars who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 30 participants. All participants provided formal consent in accordance with procedural compliance. The sample consisted of 15 male and 15 female scholars, including 12 doctoral students, 11 master’s students, 4 undergraduates, and 3 faculty members.

The third step involved conducting in-depth, semi-structured, face-to-face interviews with the selected participants. Each interview was conducted by a single interviewer and supported by electronic voice and video recording. Additionally, two note-takers were present at each session, seated behind the interviewees to minimize bias and ensure accurate and objective documentation. Interviews were scheduled to last between one and two hours, with flexibility allowed to probe relevant themes and elicit more comprehensive responses.

In the fourth step, interview recordings were transcribed and coded digitally, combining both the note-takers’ records and electronic recordings. The resulting codes were analyzed statistically based on response frequency to identify key themes and insights.

In this study, we counted the frequency with which specific types of codes appeared in interview responses. The coding rules were as follows: for yes/no questions, responses were categorized as “no”, “maybe”, or “yes”; for temporal questions, responses were coded as “won’t”, “maybe”, “less”, or “more”; and for dimensional factors, frequency was determined by the number of times a particular factor was acknowledged. The results of this analysis are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Coding table and result statistics.

In terms of knowledge channels, journals were the most frequently read type of publication among participants (29 out of 30), followed by bibliographies (15 out of 30); Although not all subjects regularly accessed academic social networking sites (25/30 had limited experience), a majority (17) still reported using them occasionally. Only 36.67% of participants believed that blog content or posts by bloggers’ friends were helpful to their research, with content quality and popularity ranked as the most important concerns (17 and 7 respondents, respectively). All interviewees agreed that accessing information through multiple channels would or could benefit their research. Regarding scholar characteristics, 73.33% of participants acknowledged the number of citations and h-index as meaningful indicators of a scholar’s academic competence. Most also considered the prestige of the scholar’s affiliated institution and academic title important, though the difference between these two factors was marginal (17 and 16 of the 30 respondents, respectively). In contrast, only 30.43% expressed strong interest in biographical or experiential information about scholars. As for topic attributes, both specific research topics and authoritative scholars were seen as valid entry points for exploring a research field, with individual preferences influencing which was prioritized. Topic labels, their standardization, and the structural organization of knowledge were considered highly valuable for locating relevant information. However, trust in non-traditional sources (such as channels other than journals or bibliographies) was limited, with only 40% expressing confidence in them. Therefore, resource access channels, topic classification systems, academic social media content (including its popularity and quality), and bibliometric indicators such as citations and h-index are all key dimensions in constructing academic portraits of Chinese scholars. These dimensions have been incorporated into the ontology design proposed in this study.

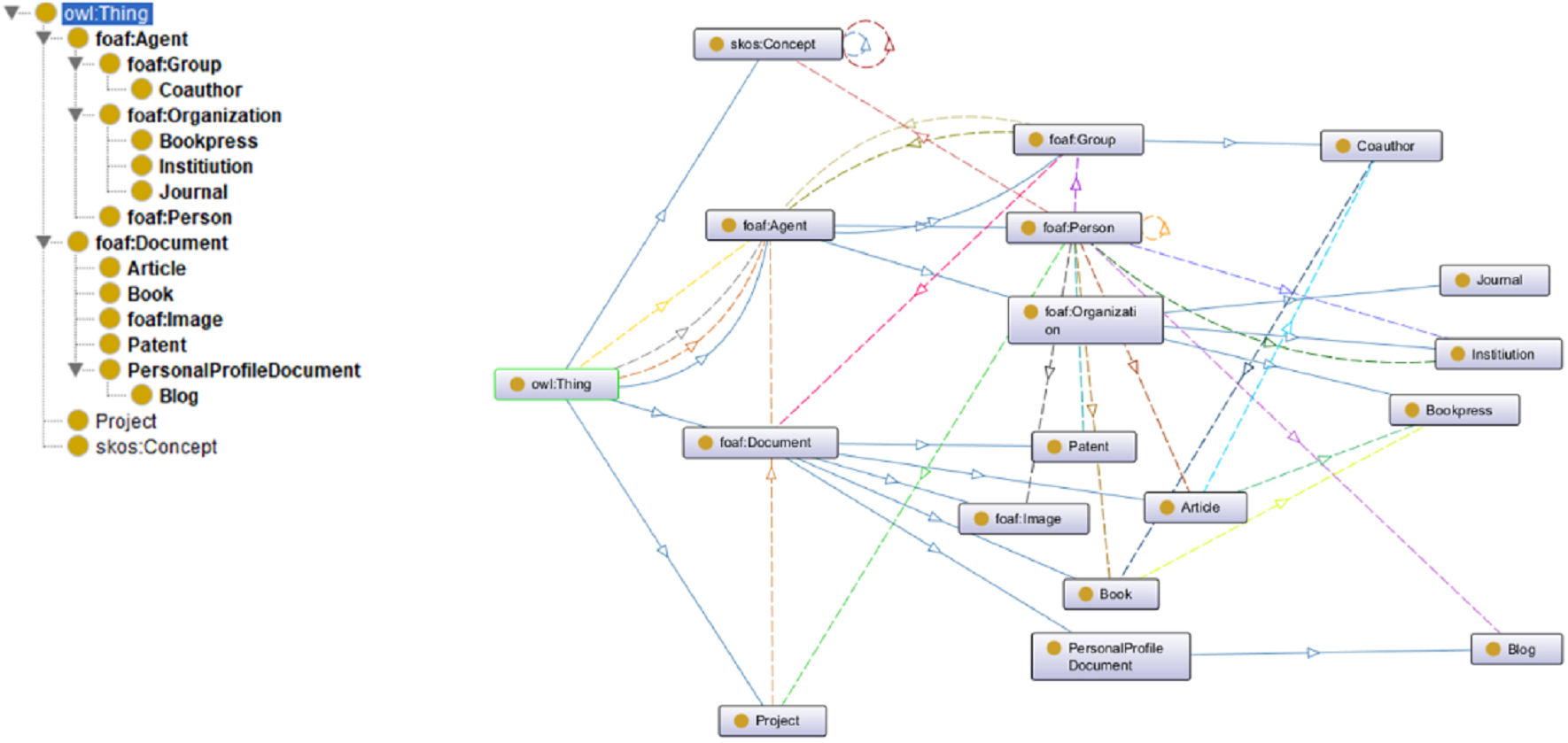

Following the steps of the “seven-step approach”, this study first identifies the knowledge domains and classification categories relevant to the academic portrait research of Chinese scholars. These encompass both the literature resource layer and the scholar resource layer, covering six key domains: patents, bibliographies, journals, scholars’ personal homepages, and academic social networking sites. The domain-specific knowledge is then semantically enriched through the integration of ontology reuse techniques, utilizing three widely adopted controlled vocabularies: DC-Core, SKOS, and FOAF. Finally, the ontological structure of POAS (Persona-of-a-Scientist) academic portraits is constructed in compliance with the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C)-recommended standard, Web Ontology Language (OWL).

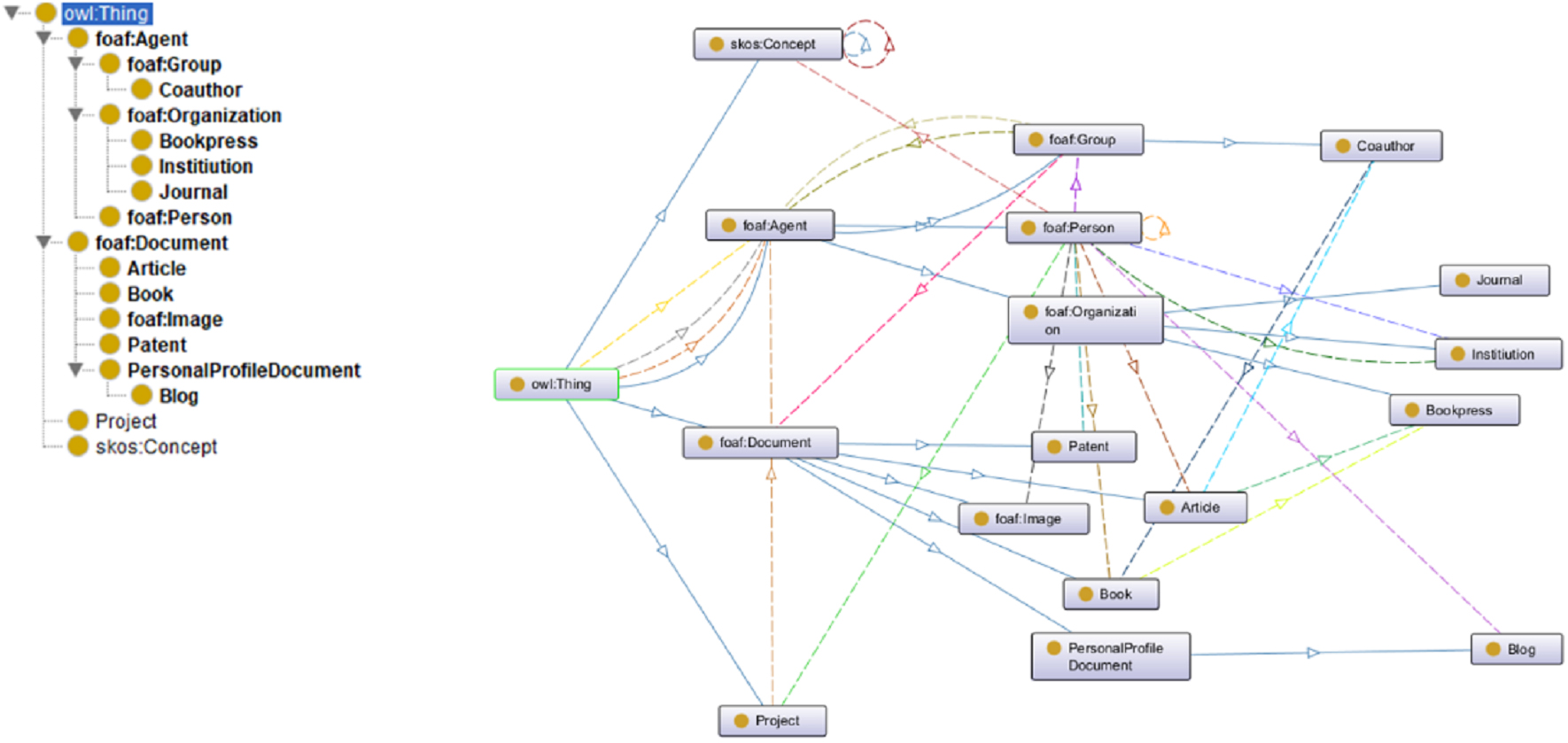

The POAS Academic Portrait Ontology extends the ontological framework vertically by organizing different “Classes” (i.e., collections of individuals sharing certain attributes) into hierarchical structures and establishing subclass relationships using the “rdf:subClassOf” property, as illustrated in Fig. 8. In OWL Lite, the class owl:Thing serves as the most general class, acting as the parent class of all OWL classes. The foundational structure of the POAS ontology is built by defining foaf:Agent, foaf:Document, SKOS:Concept, and Project as subclasses of owl:Thing, thereby representing the academic portrait across four dimensions: institution, document, concept, and project. Among these, foaf:Agent and foaf:Document serve as core classes, with several domain-specific subclasses either reused from existing ontologies or custom-defined to enhance the representation of Chinese academic profiles. These include reused classes such as foaf:Person, foaf:Group, foaf:Organization, and foaf:Image, as well as customized POAS classes such as poas:Coauthor, poas:Article, poas:Book, poas:Patent, poas:PersonalProfileDocument, and poas:Blog.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

POAS (Persona-of-a-Scientist) ontology Class hierarchy. owl, Web Ontology Language.

The reuse of established ontologies such as FOAF and SKOS provides two key benefits. First, it enables inheritance of existing class definitions, offering strong scalability and facilitating integration with other ontologies. Second, by defining relationships between reused and custom classes—through constructs like equivalentClass and intersectionOf—the model supports semantic interoperability while minimizing conceptual redundancy within the ontology.

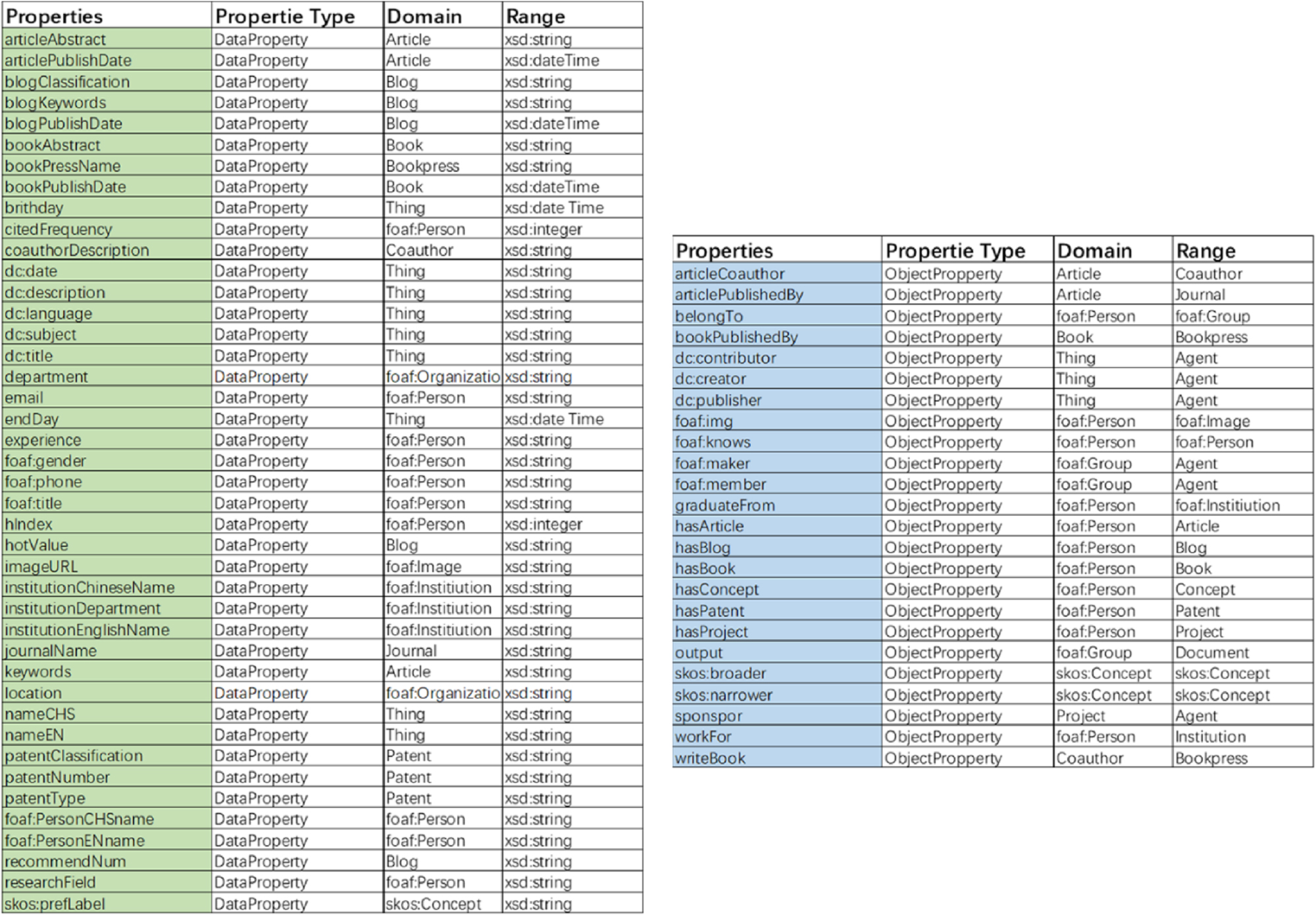

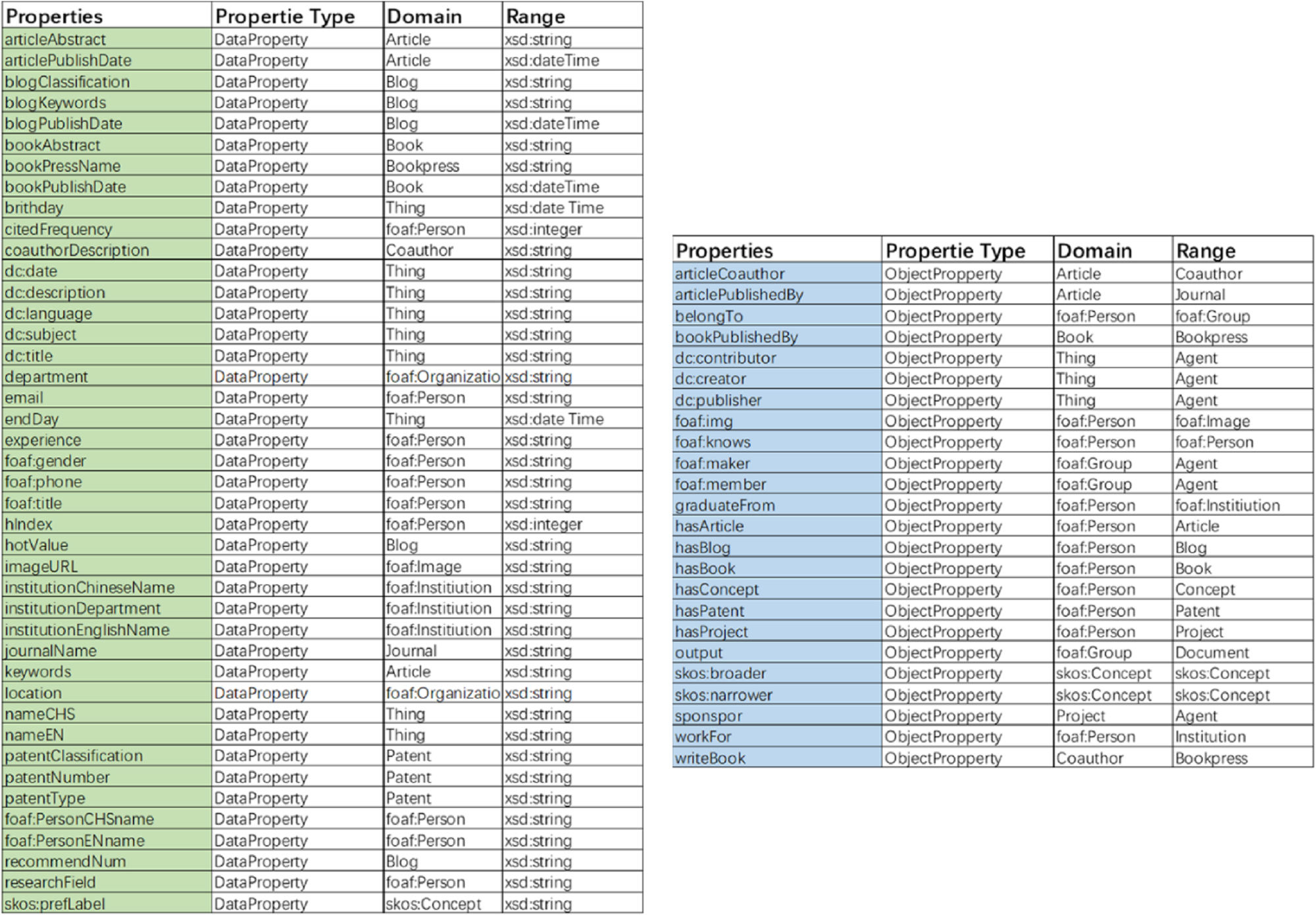

In the POAS Academic Portrait Ontology, class properties are defined using rdf:Property, and the RDF Schema (rdfs) vocabulary is employed to specify the type and scope of each property’s subject and object. The scope of the subject and object is constrained by rdfs:domain and rdfs:range, respectively. Properties are categorized as either object properties or data (numeric) properties. Object properties (ObjectProperty) require the object to be an instance of a specific class, while data properties (DatatypeProperty) have value ranges such as xsd:string, xsd:integer, or xsd:dateTime. Within the POAS ontology, this study defines 42 data properties (including 11 reused properties) and 24 object properties (including 9 reused properties), as illustrated in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

POAS ontology property description.

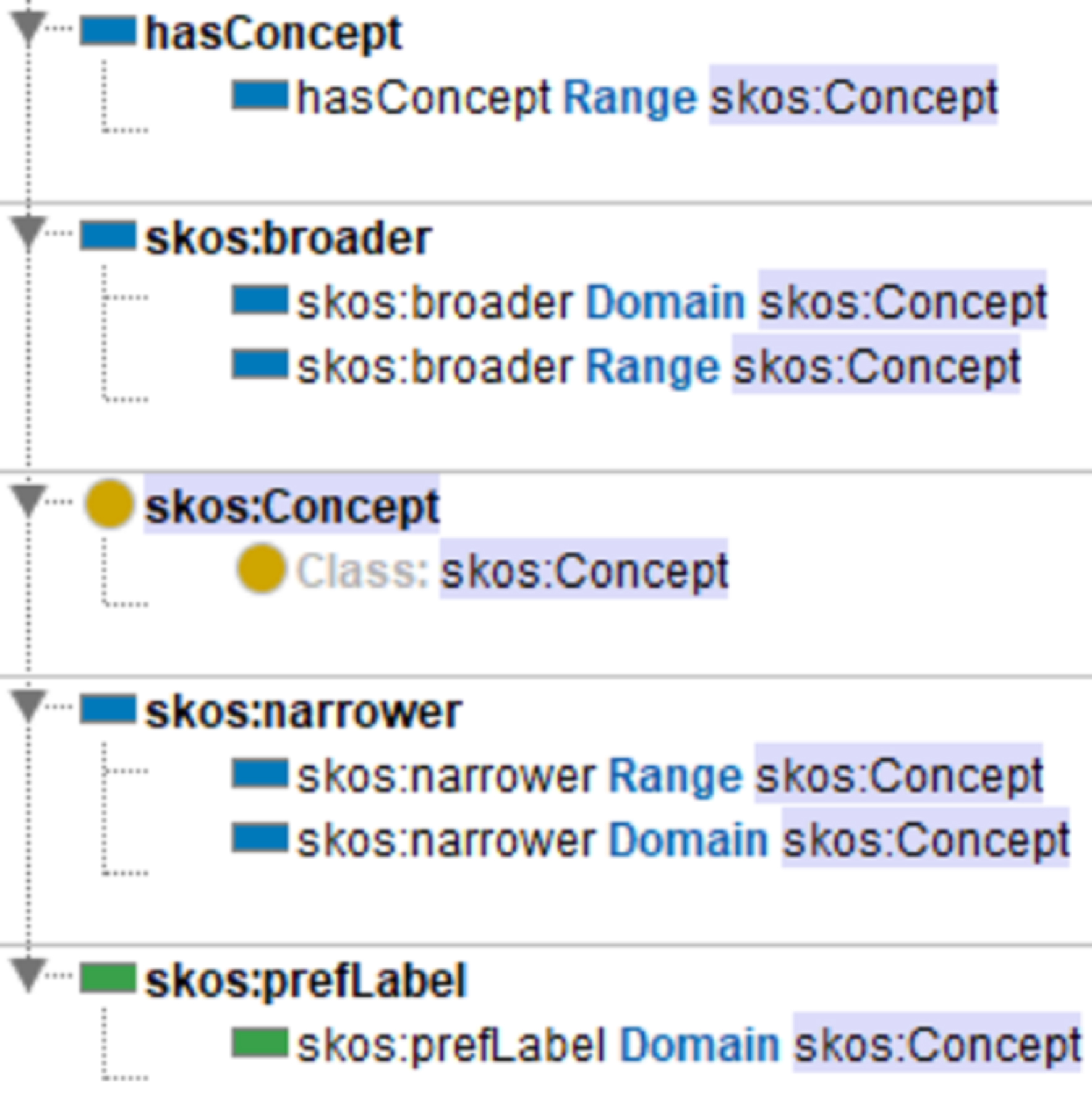

In particular, for subject concepts, the POAS Academic Portrait Ontology reuses the numeric attribute skos:prefLabel (preferred term) and defines object-oriented properties that establish semantic relationships. One such property, hasConcept, links the foaf:Person class (representing scholars) with the skos:Concept class (representing subject concepts). Additionally, the ontology reuses skos:narrower and skos:broader to define hierarchical relationships among subject concepts, allowing for the contextual inheritance of knowledge themes. This implicit semantic hierarchy differs from the explicit class inheritance structure in ontology design. The former is organized around “thematic concepts” as the core of domain representation—where concepts are not equivalent to classes—whereas the latter reflects the structured hierarchy of scholar portrait dimensions based on class characteristics, as illustrated in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Design of classes and attributes for the theme concept (skos:Concept).

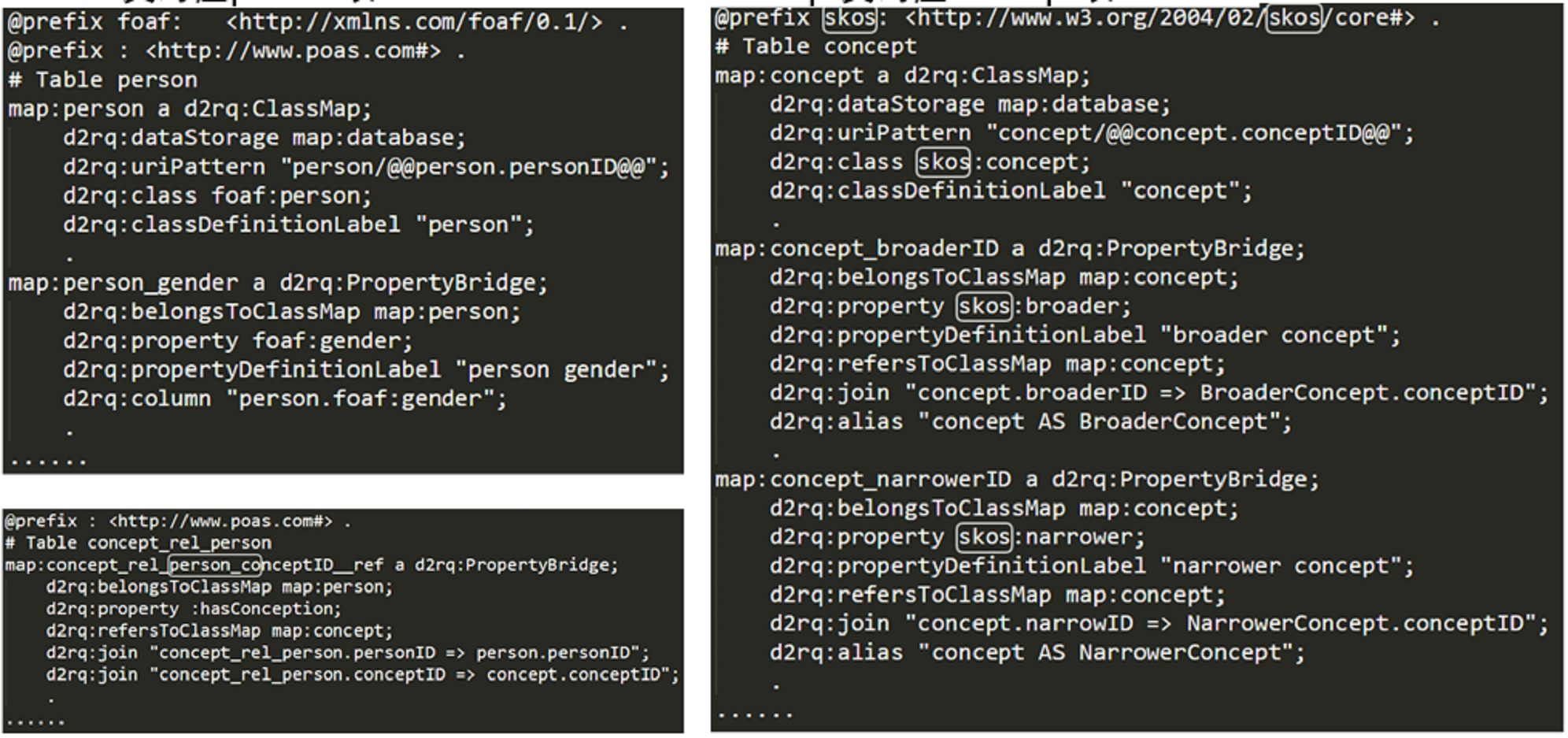

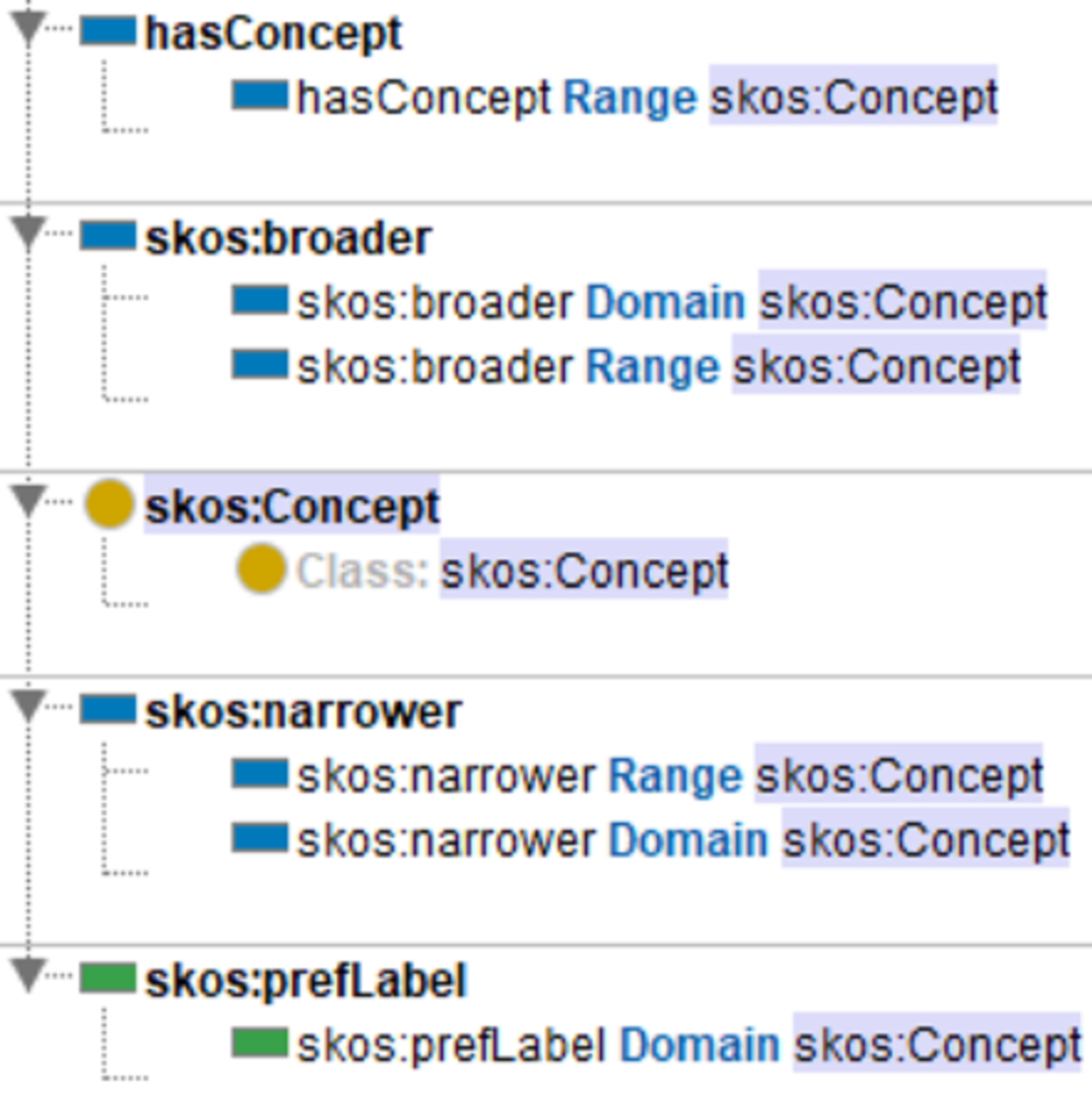

Based on the ontology schema, we perform relational database-to-RDF file mapping using a D2RQ mapping file. The core of this approach involves introducing relevant namespaces—such as rdf, rdfs, and owl—and reusing established ontologies like DC and SKOS, in addition to defining a default base namespace to serve as a prefix vocabulary within the mapping file. Next, for various types of individual tables, we define specific “D2RQ ontology mapping rules”. As illustrated in Fig. 11, one example is the mapping configuration for the Person class (representing scholars), which uses the hasConcept property to link to instances of the Concept class (representing scholars’ topics of interest).

Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Mapping ttl file correction for d2rq.

The class rules use d2rq:ClassMap to define the mapping between the Person table in the Academic Portrait database and its corresponding ontology class. The primary key (personID), which uniquely identifies each scholar instance, is mapped using d2rq:pattern to generate the url for each individual. To ensure consistency in class naming, the vocabulary prefix for the concept of scholars (e.g., foaf:person) must first be established to determine the name space of the reused ontology, which is then specified using d2rq:class. For property mappings, d2rq:PropertyBridge is employed to define data properties—such as the scholar’s gender (e.g., person_gender)—by linking them to corresponding columns in the Person table using the d2rq:column attribute.

Multi-category join tables are used to represent relational attributes between different classes—for example, the concept_rel_person table captures the associations between individual scholars and their subject interest concepts. Based on this structure, existing defined classes can be used to constrain the domain and range of relational attributes via d2rq:belongsToClassMap and d2rq:refersToClassMap, respectively. To establish a semantic connection between the Person class and the Concept class, the object property hasConcept is defined using d2rq:Property, with the appropriate prefix from the default namespace. The d2rq:join directive specifies the mapping between the primary key of one class table and the foreign key in the join table. In this context, it is used to semantically map entries in the person and concept tables to their corresponding identifiers (primary keys) in the concept_rel_person table.

For the subject concept class Concept, relational attributes play a crucial role in defining contextual and logical relationships for knowledge representation. This study employs the SKOS ontology to define such relationships, using skos:broader and skos:narrower to represent hierarchical links between broader and narrower concepts, respectively. The mapping to database tables is implemented using the aliasing method (d2rq:alias) and foreign key specifications via the d2rq:join statement, enabling the manipulation of topic concepts through self-joins within a single table.

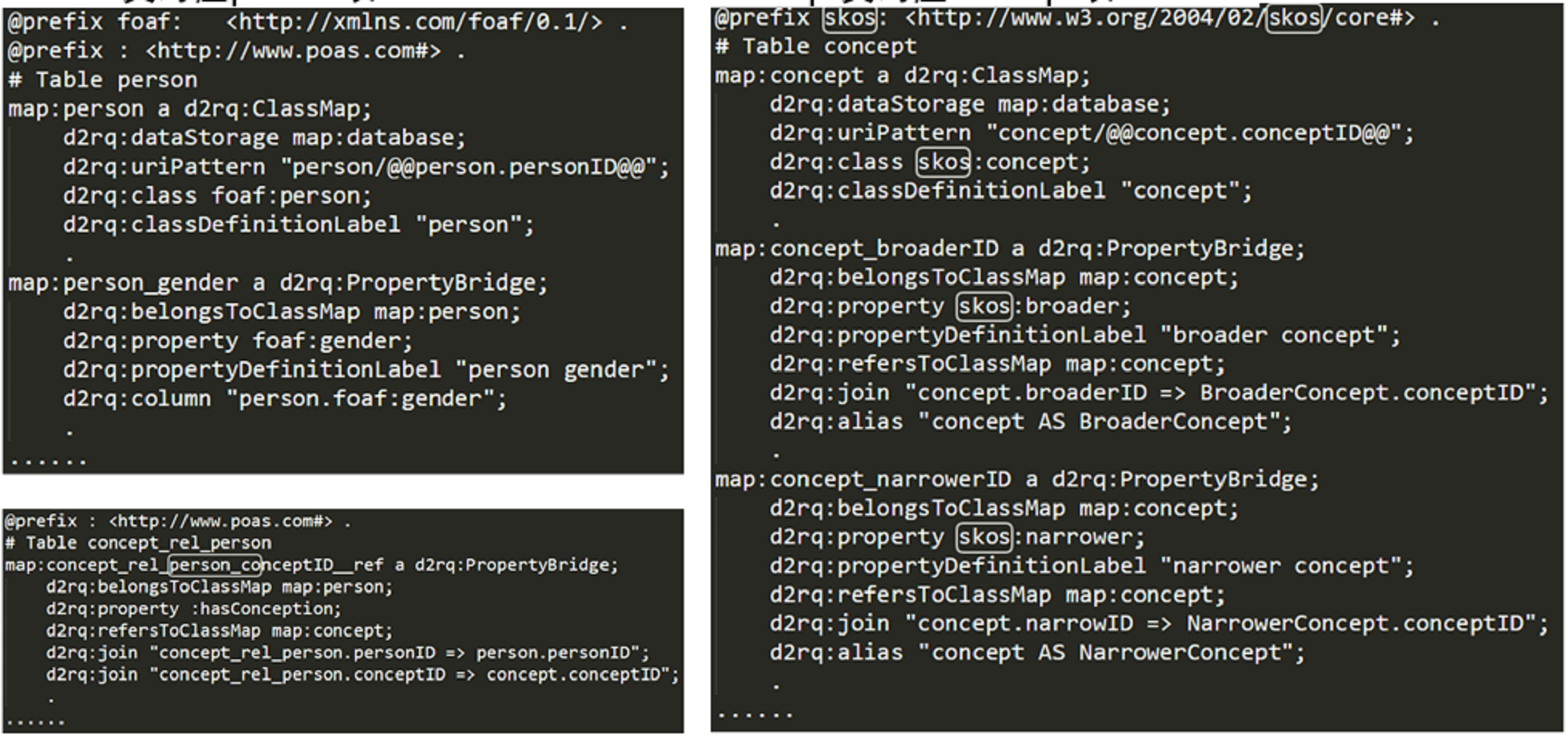

In ontology-based web services, users can perform query and navigation operations on D2RQ-published ontologies available online—for example, browsing and accessing information related to the “Person” class. These detailed knowledge descriptions include a scholar’s name, date of birth, gender, email address, contact information, research field, educational background, professional experience, co-author network (coauthor), affiliated organization (workFor), and more, as illustrated in Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

Scholar instance information for “person#100463”.

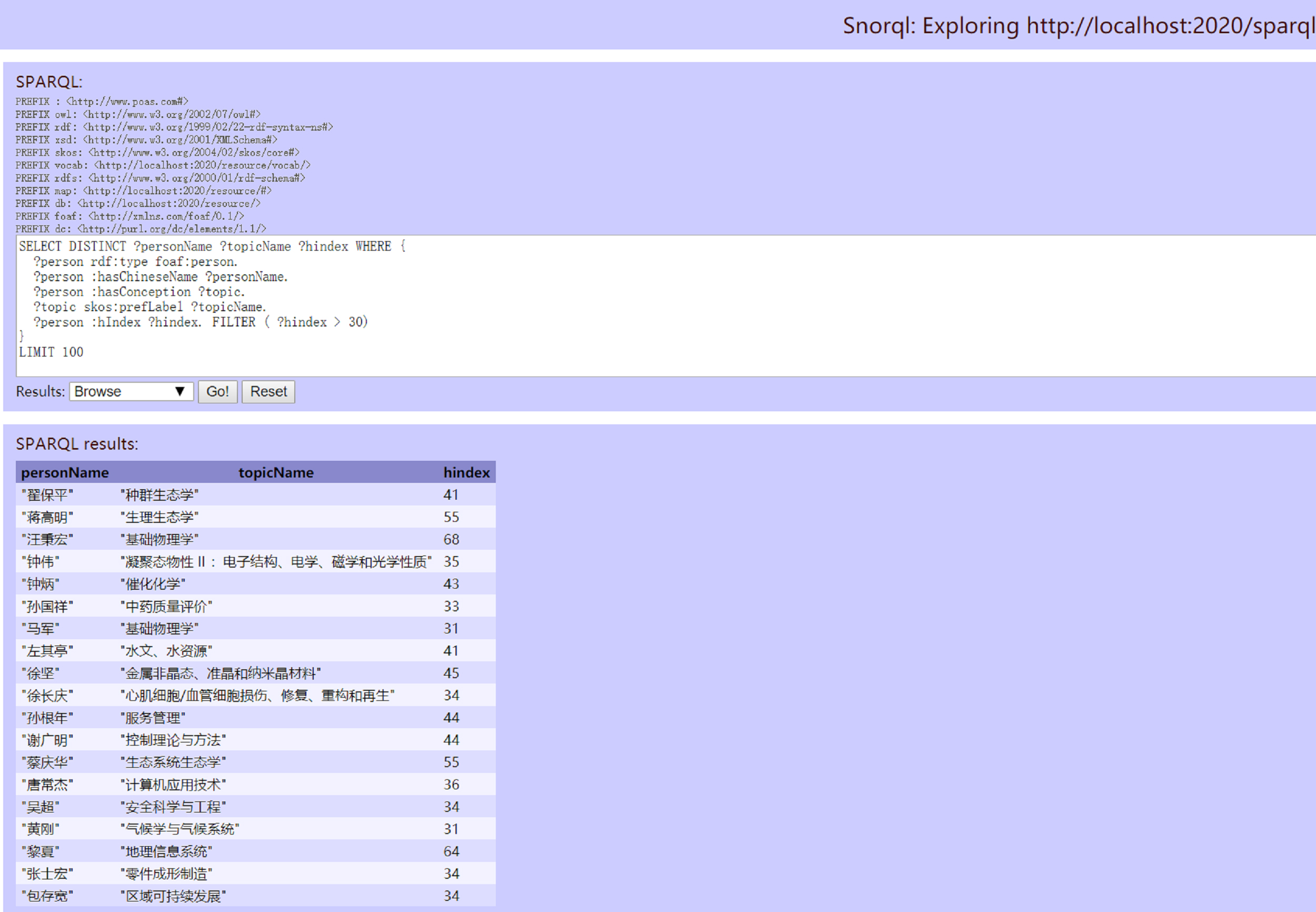

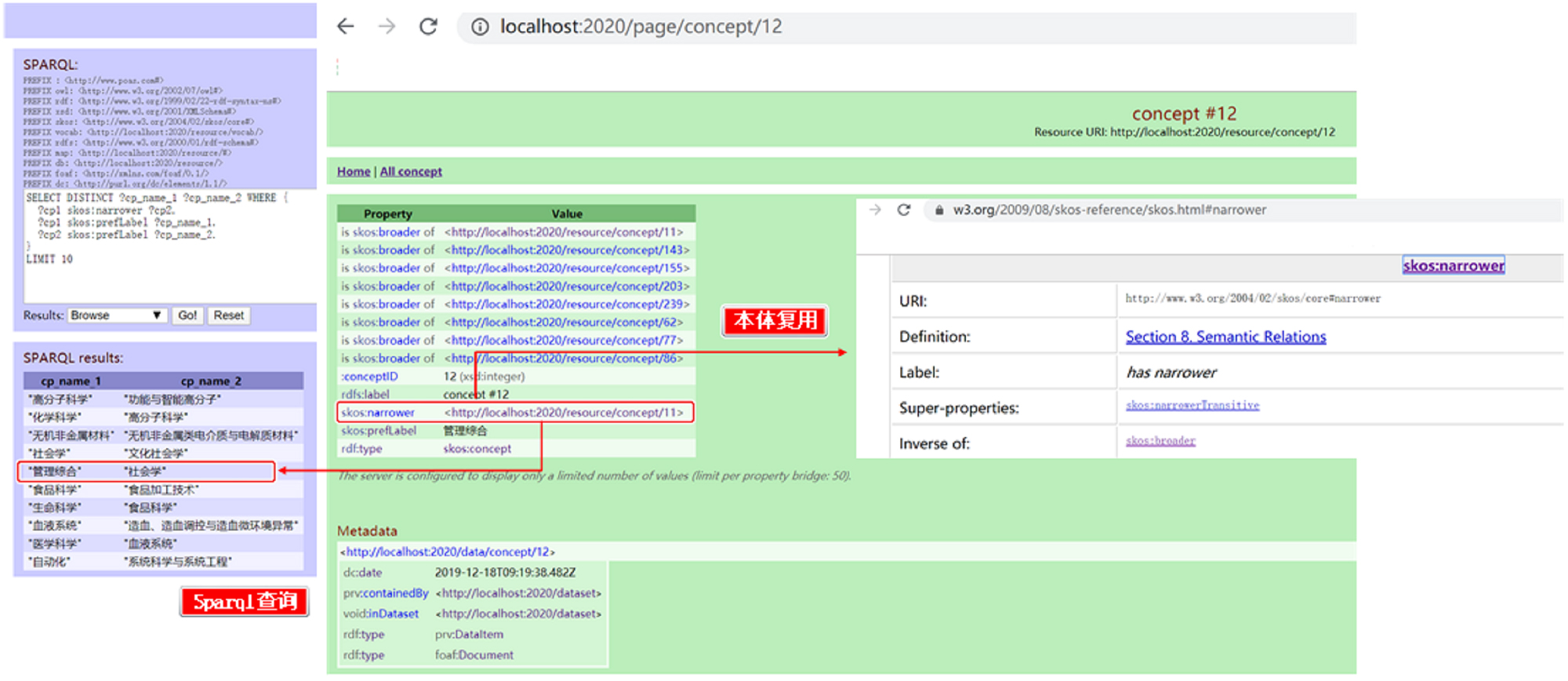

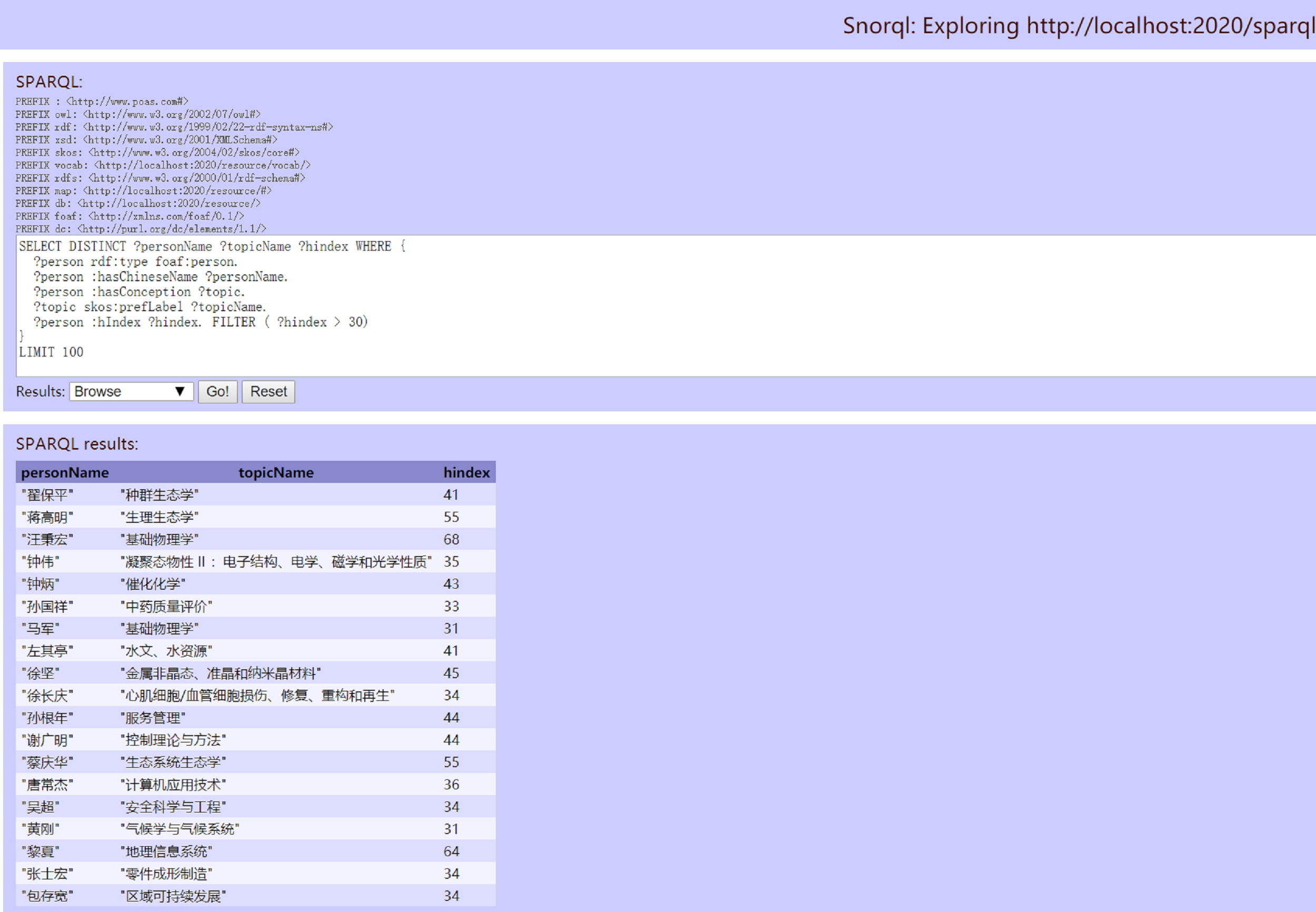

In addition to knowledge browsing and navigation, this study introduces a SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language (SPARQL)-based query method that allows users to perform customized searches on RDF class data resources. Fig. 13 illustrates a complex query example that retrieves topics of interest for scholars with an h-index greater than 30. The SPARQL query method enforces strict normalization and precision in vocabulary usage, minimizing semantic ambiguity during database queries. Moreover, each object, term, and resource in POAS is linked to a unique namespace, further reducing confusion in user interpretation. For instance, as shown in Fig. 14, a user querying the structure of a research theme concept can quickly learn that “sociology” is a subfield of “management synthesis”. If the user wants to explore the meaning and scope of the skos:narrower relationship, they can follow its corresponding URL to view its namespace, concept definition, and knowledge domain. By directly reusing the SKOS ontology, the system effectively manages the contextual hierarchy of conceptual topics. From the user’s perspective, semantic interoperability enhances the clarity and utility of query results. From a development standpoint, ontology reuse significantly reduces redundancy and errors, while also improving storage efficiency and web service performance.

Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Topics of research interest for scholars with an “h-index greater than 30”.

Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.

Academic portrait RDF semantic data publishing with sparql queries.

This research focuses on developing a standardized and actionable model for digitized materials related to scientists across various domains, as well as their associated academic information. By integrating heterogeneous platforms and applying ontology-based knowledge organization, the study aims to promote data openness and enhance the efficiency of academic knowledge management services. We conduct an in-depth analysis of the multidimensional digital data generated by Chinese scientists, including research activities, academic outputs, and documentary records. Building on ontology reuse and faceted analysis within a “horizontal” network environment, we construct a conceptual foundation for standardized academic digital portraits. Furthermore, we design a mechanism that integrates heterogeneous information sources and applies semi-automated semantic annotation and validation, significantly improving data accuracy and consistency across platforms. The final output—academic portraits of Chinese researchers—is published and made available for semantic querying via customized scripts.

From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to the advancement of the semantic web, ontology theory, and knowledge graph research. It also promotes interdisciplinary collaboration among fields such as library and information science, sociology, computer science, and psychology, fostering the development of diverse academic disciplines and generating innovative theoretical insights. These advancements support cross-disciplinary research and personalized knowledge services, ultimately enhancing academic exchange and collaboration. From a technical standpoint, the academic portrait knowledge base supports semantic search, personalized recommendations, question-answering systems, and intelligent discovery services—key components of intelligent web services in the big data era.

Nevertheless, some limitations remain. The scope of interviews was limited, and the sample size of participants and scientists included in the portrait knowledge base is still relatively small. Additionally, the ontology modeling process requires substantial manual input, and the integration of this knowledge base with large-scale external systems for semantic reasoning remains an open challenge. Notably, one issue that warrants attention is the disciplinary composition of WCS bloggers. The majority come from natural science and engineering backgrounds, particularly the committee members whose research is predominantly focused in these areas. In contrast, scholars from the humanities and social sciences account for less than 5% of the total. The criteria used to build a representative sample of Chinese scientists did not fully account for disciplinary differences, which may introduce bias into the results and limit the generalizability of the findings across all academic fields. Future work should focus on expanding the scale of the dataset and applying machine learning models to generate embedded characterizations. The development of a more intelligent and interactive visualization platform for the academic portraits of Chinese scholars, based on advanced analytics and visualization technologies, is also a key direction for ongoing research.

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the correspondence author upon reasonable request.

YL and CY designed the research study. YL performed the research. FS provided help and advice on research design and methodology. CY analyzed the data. YL, CY and FS wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

We gratefully acknowledge the comments and guidance from all reviewers.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGpt-3.5 in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.