1 Department of Library and Information Science, Hansung University, 02876 Seoul, Republic of Korea

Abstract

This study explores how integrating Knowledge Organization Systems (KOSs) with generative artificial intelligence (generative AI) can enhance retrieval and discovery processes. KOSs offer structured vocabularies to support knowledge organization, whereas generative AI provides advanced language processing and recommendation capabilities. A major challenge is hallucination, where AI generates responses that appear plausible but are factually incorrect. To address this issue, the study examines how the quantity and quality of metadata influence hallucination mitigation and recommendation accuracy. The study evaluates four levels of metadata (0–3) using an iterative approach that incorporates expert feedback for validation. The results indicate that higher levels of metadata improve the precision of recommendations and significantly reduce hallucination rates. In addition, refinement was applied to Level 0, where hallucinations were most frequent, and Level 2, where metadata usage was suboptimal, through prompt engineering and iterative feedback. The findings confirm that structured prompts and user feedback can effectively enhance the reliability of AI-generated recommendations. Moreover, the study emphasizes the essential role of expert involvement in curating high-quality metadata and ensuring the credibility of AI-driven knowledge retrieval systems. Future research should investigate multilingual KOS recommendations, examine the scalability of AI-integrated KOS models, and develop methods to ensure consistency and reproducibility in AI-generated recommendations.

Keywords

- knowledge organization systems (KOSs)

- metadata-driven recommendation

- AI-based recommendation

- generative artificial intelligence

- prompt engineering

- hallucination mitigation

As fundamental infrastructures for knowledge organization and discovery, Knowledge Organization Systems (KOSs) enable structured access to information across diverse domains. KOSs also function as a valuable information resource, requiring effective management through dedicated registries. Despite their importance, current retrieval and recommendation methods for KOS registries are limited in both scope and efficiency, posing challenges to the seamless access and utilization of knowledge. Most existing approaches still depend on browsing structured lists or conducting keyword-based searches, which often fail to align with users’ diverse search intentions. To address these limitations, several enhancements are proposed, including the use of advanced retrieval and recommendation algorithms, the implementation of query expansion techniques, and the inclusion of more detailed KOS descriptions.

However, implementing these enhancements presents significant challenges, as KOS repositories are often maintained collaboratively rather than through large-scale funding. The key challenge lies in predicting the impact of updates prior to implementation, which complicates the assessment of potential improvements. In this context, generative artificial intelligence (generative AI) offers a promising solution. By enabling interactive query-and-response exchanges without the need for coding, generative AI allows intuitive engagement through conversational interfaces, thereby enhancing user interaction with KOS registries. In prompt-based interactions, generative AI maintains contextual awareness across consecutive queries, enabling users to refine or specify their questions progressively.

Furthermore, with the integration of data upload and web search functionalities, generative AI supports both internal data exploration and external data retrieval. These capabilities position generative AI platforms, such as ChatGPT, as valuable tools for knowledge discovery, data exploration, and analysis. However, generative AI also presents challenges, as it may generate unintended responses and exhibit hallucinations, producing seemingly factual answers that do not reflect actual occurrences. Therefore, when applying generative AI to KOS management and discovery, it is crucial to consider not only strategies for optimizing retrieval and recommendation performance but also measures to mitigate hallucination and enhance the reliability of AI-generated outputs.

Building on this foundation, this study aims to integrate metadata from existing KOS registries with generative AI platforms to enhance the performance of KOS retrieval and recommendation. Specifically, it investigates how generative AI can leverage KOS metadata to improve search accuracy, refine recommendations through user feedback, and generate recommendations beyond those registered in the KOS. In addition, the study addresses the issue of hallucination in AI-generated recommendations, with the goal of improving their reliability. To achieve these objectives, the study formulates the following research questions.

• How effectively can generative AI retrieve relevant KOSs from existing

registries? • To what extent can user feedback improve the accuracy of KOS recommendations

from generative AI? • Can generative AI recommend that KOSs be excluded from the registry by

leveraging external knowledge sources? • How can hallucinations in generative AI-generated recommendations be minimized

to improve reliability?

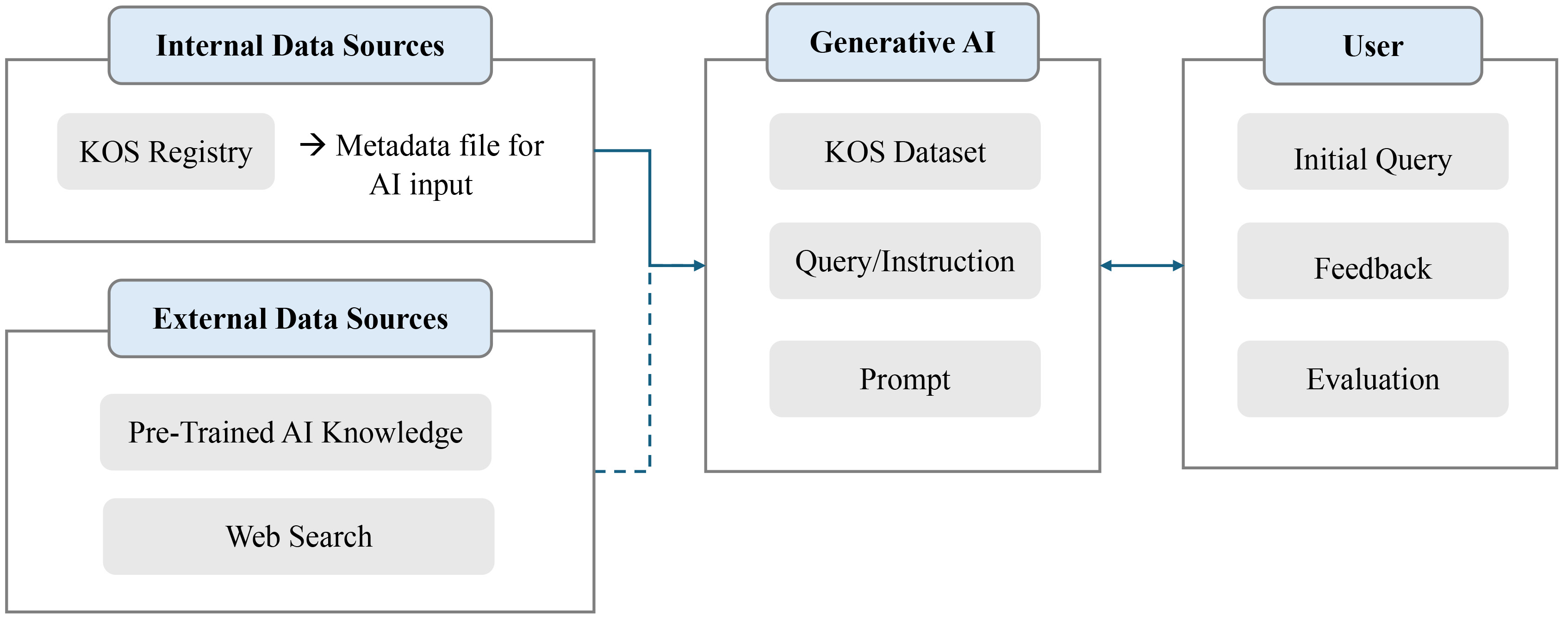

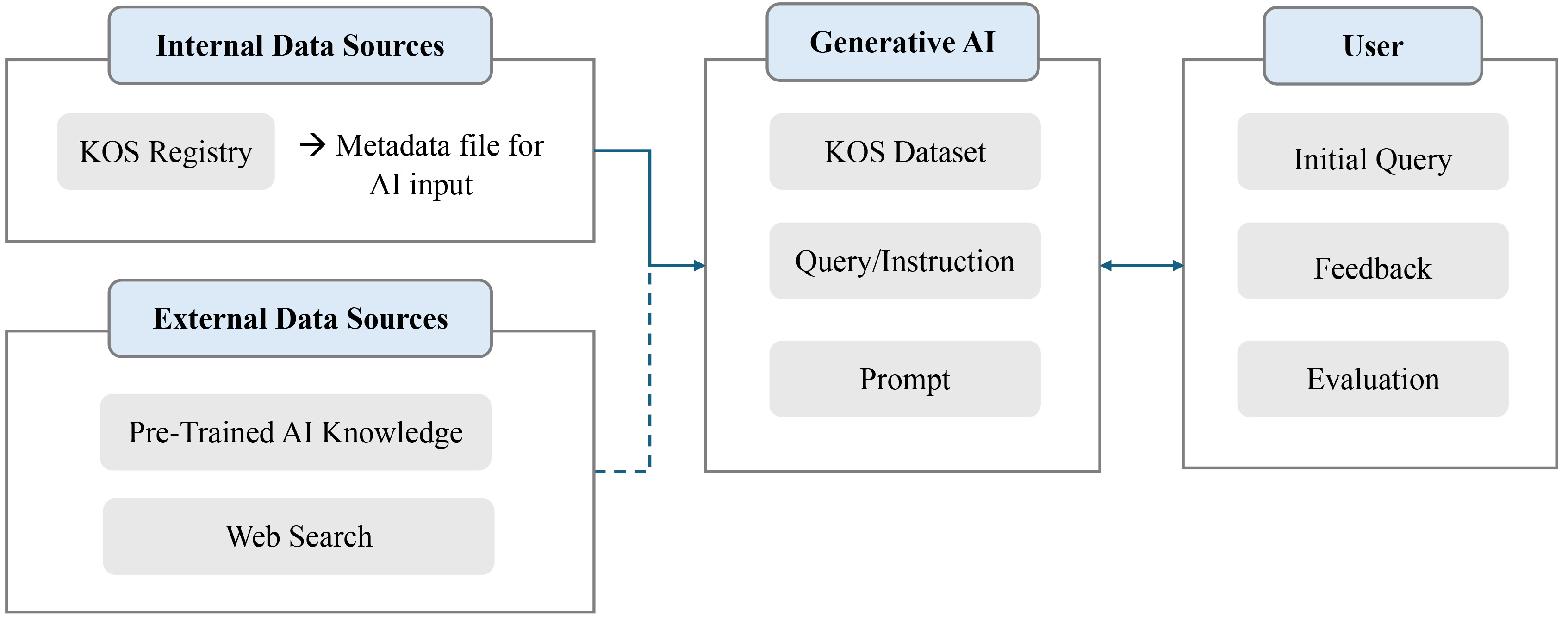

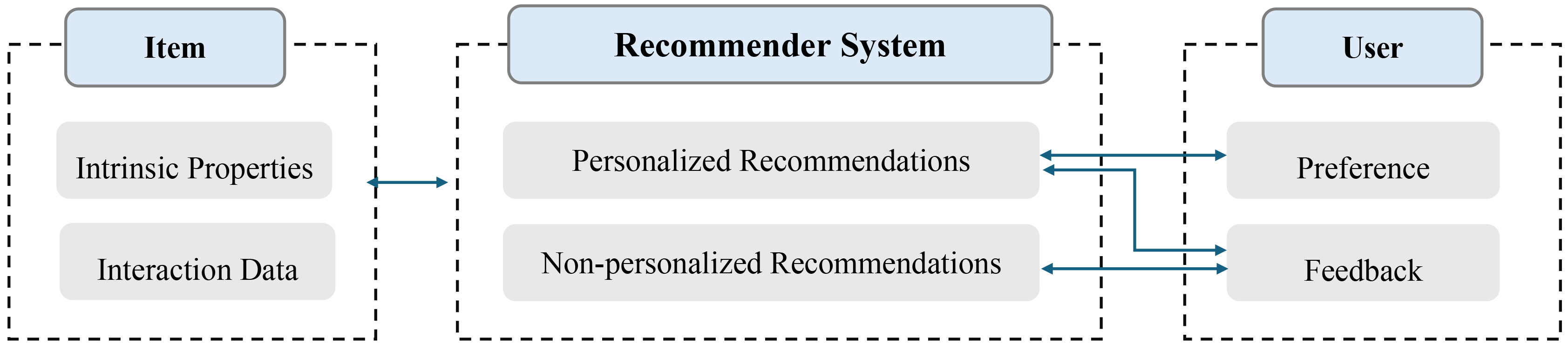

This study proposes a structured framework that integrates metadata extracted from KOS registries with generative AI to enhance the accuracy and relevance of retrieval and recommendation processes. Fig. 1 illustrates this structured methodological framework, outlining the three key components of the research design, which are (1) data sources, including internal KOS registries and external knowledge bases; (2) generative AI processing; and (3) user interaction for iterative refinement.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the research methodological framework. KOS, Knowledge Organization System; AI, artificial intelligence.

(1) Data sources

• The internal data source consists of KOS registries, from which structured

metadata files (KOS datasets) are extracted for recommendation tasks. • The external data source includes pretrained knowledge embedded in the

generative AI model, along with web search capabilities that provide additional

contextual information for recommendations.

(2) Generative AI processing

• The system processes KOS datasets and user-provided queries or instructions as

prompts to refine both search and recommendation results. • Through iterative refinement, the generative AI continuously enhances the

quality of its recommendations based on received inputs.

(3) User interaction and evaluation

• User interaction begins with submitted queries, which are analyzed and processed

by the generative AI. • Feedback mechanisms support ongoing refinement, enabling recommendations to

adapt to user needs dynamically. • Evaluation measures the system’s effectiveness by assessing retrieval accuracy,

recommendation quality, and overall user satisfaction.

This framework offers a dynamic and interactive approach to KOS recommendation by integrating structured metadata, pretrained AI knowledge, and external data sources. The generative AI system enables adaptive learning through iterative user interactions, continuously improving the accuracy of recommendations. By incorporating user feedback and evaluation metrics, the model supports a more context-aware and user-driven discovery process. This methodology not only enhances the usability of KOSs but also advances AI-driven knowledge retrieval by addressing the limitations of traditional keyword-based search systems.

Functioning as structured vocabularies, KOSs support both the organization and retrieval of knowledge. Controlled vocabularies—such as classification schemes, thesauri, and metadata schemas—serve as forms of KOSs that facilitate the structuring and retrieval of knowledge (Bratková and Kučerová, 2014; Gnoli, 2020, pp. 74–85; Mazzocchi, 2018; Zeng and Qin, 2016, p. 187). Although the term “knowledge organization systems” has gained widespread recognition only in recent years, the tools it encompasses—such as classification schemes and indexing languages—have long existed. KOSs include a wide range of structures, from simple keyword lists to more complex frameworks such as gazetteers, classification schemes, taxonomies, and ontologies. Moreover, the choice of these terms has been shaped more by cultural context than by strictly defined semantic distinctions (Gnoli, 2020, p. 71).

From a metadata perspective, KOSs function as controlled or value vocabularies, supplying value spaces for metadata elements to support effective information description. In addition to offering controlled terms and codes, KOSs play a fundamental role in structuring the semantic framework of a domain. They enhance concept representation, navigation, and interoperability by defining relationships, properties, and classifications through structured labels and definitions (Zeng and Qin, 2016, p. 279). Therefore, although the names, types, and structures of KOSs may vary across periods and contexts, they can broadly be defined as metadata specifically created to support knowledge organization and discovery.

KOS registries are designed to aggregate and provide systematic metadata on diverse KOSs to enhance the organization and retrieval of knowledge resources. Zeng and Žumer (2013a; 2013b) emphasize that such registries should assist users in tasks such as finding, identifying, selecting, obtaining, and exploring KOSs. Just as the term “KOS” encompasses various knowledge organization tools and systems, KOS registries are also described using multiple terms, including vocabulary registries and KOS online directories. Zeng (2019) distinguishes between vocabulary registries and vocabulary repositories, noting that registries provide metadata about KOSs rather than storing the actual content of the vocabularies themselves. Similarly, Gnoli (2020, p. 73) refers to KOS metadata services such as the Basic Register of Thesauri, Ontologies & Classifications (BARTOC) (VZG, 2024), describing it as an “online directory of thousands of KOSs”. In other words, a KOS repository can be defined as a service that collects and provides KOS metadata in an online environment. The operational environment of KOS has evolved from physical libraries to digital databases and eventually to the Internet (Mazzocchi, 2018).

Historically, KOSs were distributed in book format, organized by call numbers, and shelved in library reference sections. Today, they are structured and delivered in an online environment. As the web has become the primary platform for information access and KOSs continue to be digitized, it is now possible to interlink and integrate previously dispersed KOS across domains, enabling more comprehensive retrieval. Like KOS themselves, KOS registries vary in the scope and volume of aggregated content, as well as in the depth and granularity of the metadata they provide. Nevertheless, collecting reliable KOSs and developing well-structured metadata remain essential for enabling effective discovery, identification, comprehension, use, and reuse of KOS.

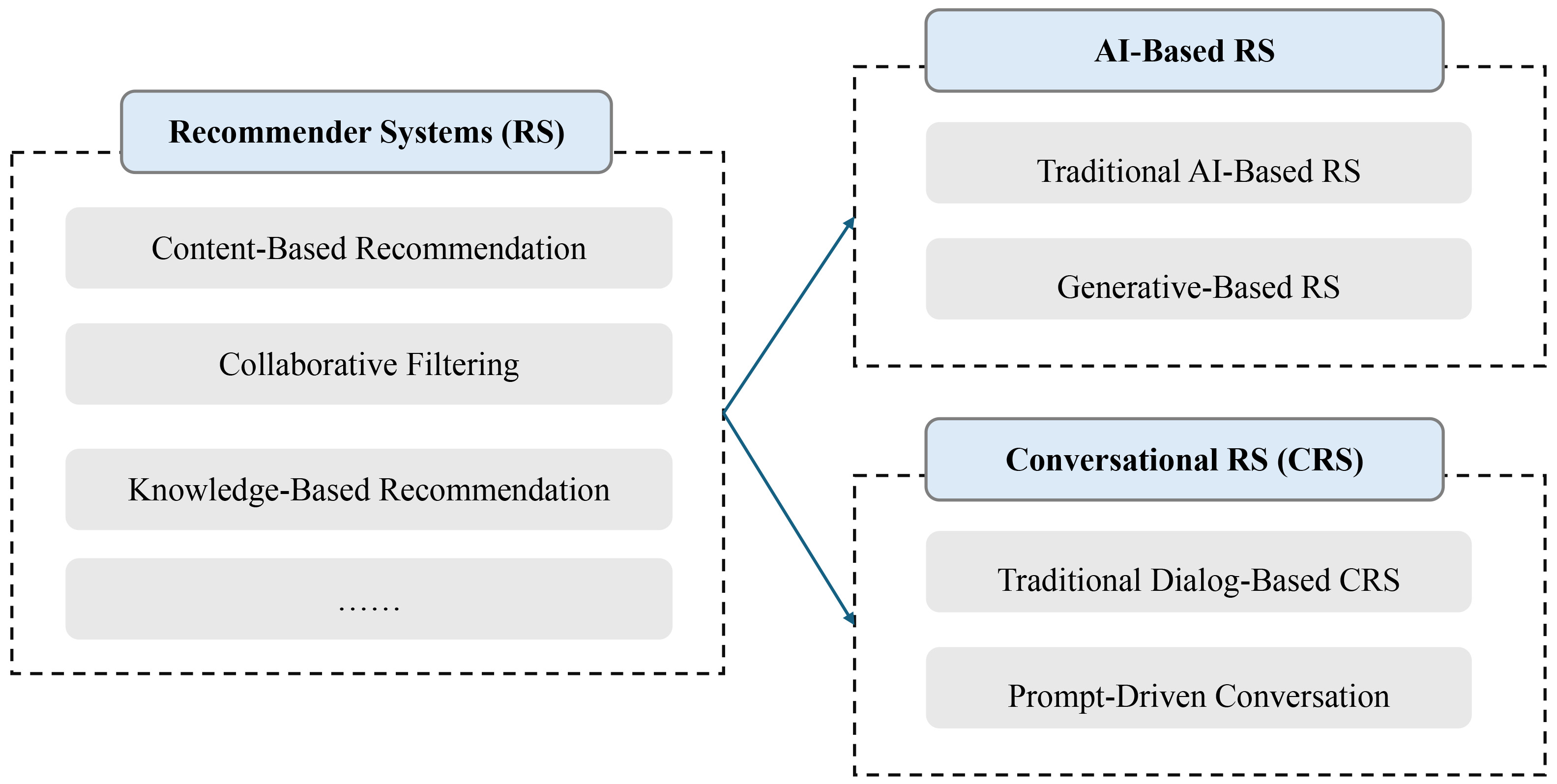

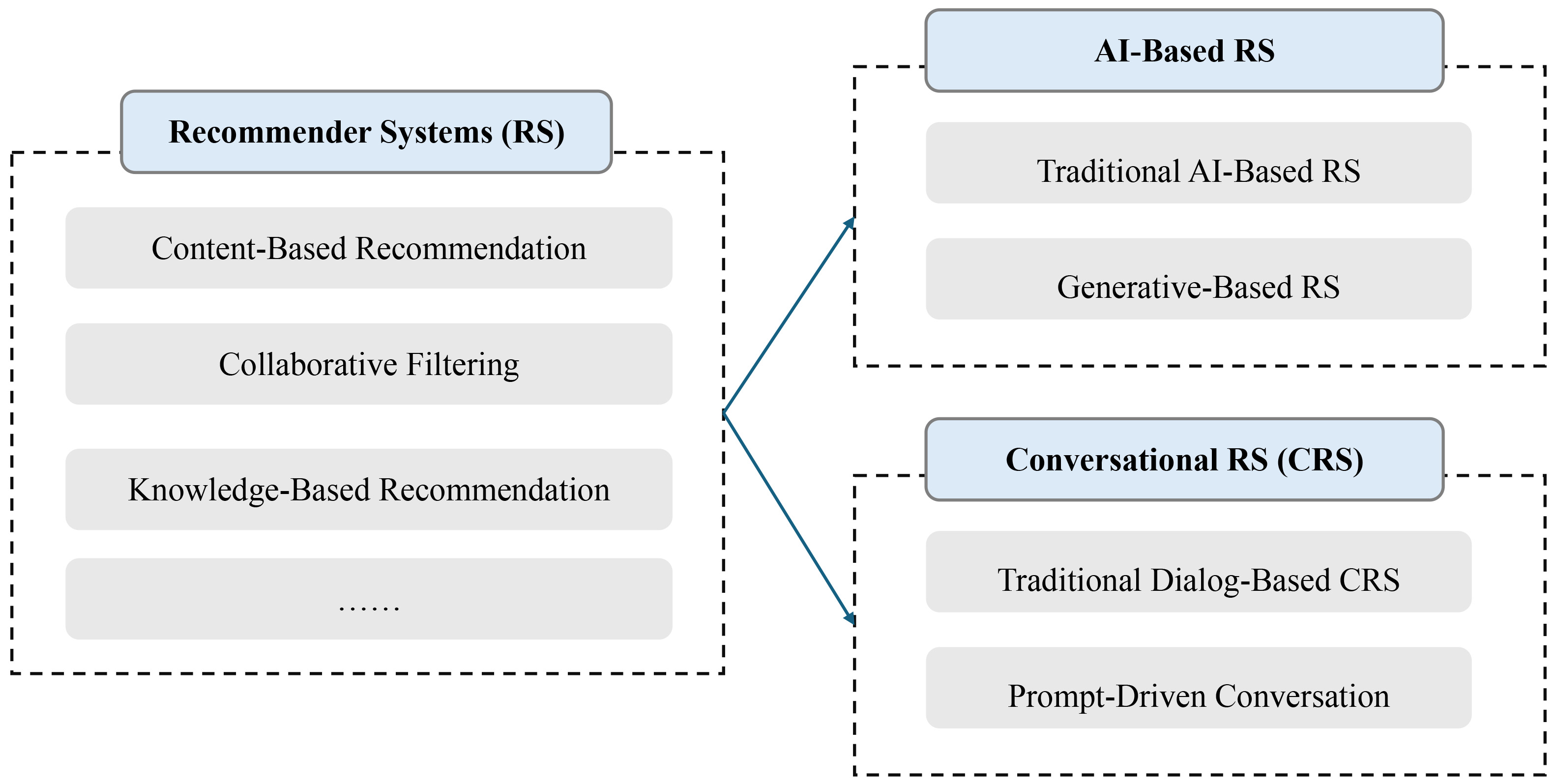

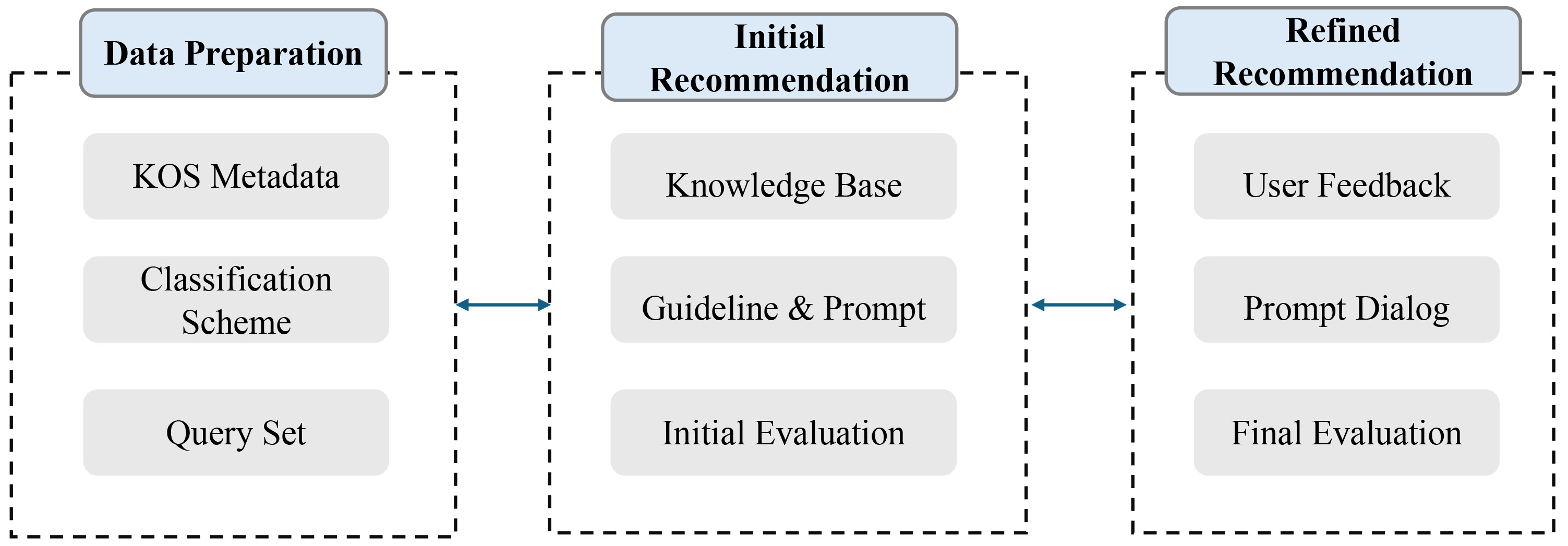

Recommender systems (RSs) have emerged as a key technology in personalized information retrieval, distinguishing themselves from traditional search engines by proactively suggesting items based on user preferences and interactions. The development of RS has progressed through various approaches, including content-based filtering, collaborative filtering, and knowledge-based recommendation techniques. Recent advancements in AI have significantly enhanced RS capabilities, giving rise to AI-driven and conversational recommender systems (CRSs). CRSs, in particular, enable interactive recommendations through natural language exchanges, with generative AI-based systems providing enhanced adaptability and contextual awareness. To illustrate this evolution, Fig. 2 presents a classification of RS research, mapping the progression from traditional systems to AI-driven RS and CRS. The contrast between traditional AI-based and generative AI-based recommendations underscores recent advancements in AI, particularly in enhancing contextual understanding and addressing hallucination challenges.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

RS Research Classification: AI-based and conversational approaches.

RSs are software tools that suggest relevant items to users, where an “item” refers to any entity recommended by the system (Ricci et al, 2011, p. 1). These systems primarily function as personalized recommendation engines, tailoring suggestions to user preferences and mitigating information overload across various domains (Zhang et al, 2021, p. 439; Ayemowa et al, 2024, p. 87742). While personalized recommendations dominate, nonpersonalized recommendations also play a role, providing suggestions based on general trends rather than individual user preferences. In this regard, nonpersonalized RSs share similarities with search engines, which retrieve and rank items based on relevance (Ricci et al, 2011, p. 6).

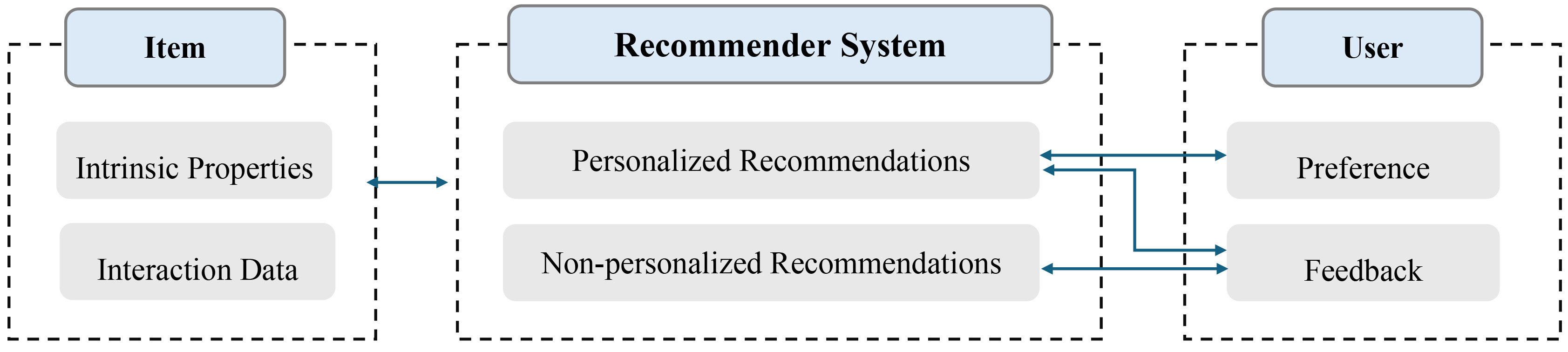

Based on this framework, the RS can be summarized as shown in Fig. 3. The figure illustrates a system composed of three core components: the item, the RS, and the user. The item component consists of intrinsic properties, such as categorical classifications and descriptive attributes, along with interaction data, which reflects user engagement patterns like browsing history and ratings. The RS generates both personalized and nonpersonalized recommendations, utilizing either individual preferences or general content-based patterns. The user component further refines recommendations through preferences and feedback, enabling continuous learning and performance optimization. These distinctions correspond to the three primary recommendation techniques: content-based RSs, collaborative filtering, and knowledge-based methods (Zhang et al, 2021, pp. 440–442).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Structure of RS with personalized and non-personalized recommendation flow.

Content-based RSs analyze item descriptions and match them with user profiles to suggest similar items. Collaborative filtering infers item relevance based on the preferences of users with similar interests, assuming that individuals with shared preferences will likely favor similar items. Knowledge-based RSs generate recommendations by leveraging structured knowledge of user needs and item functionalities, incorporating prior constraints and solutions into the decision-making process.

Although RSs have significantly enhanced information retrieval through personalized suggestions, they continue to face several challenges. In particular, collaborative filtering-based systems have inherent limitations that compromise recommendation accuracy and adaptability.

• Cold start problem: There is a difficulty in generating recommendations for new

users or items because of insufficient interaction history. • Data sparsity problem: Sparse user-item interactions hinder the generation of

accurate recommendations. • Diversity problem: Recommendations often cluster within limited categories,

reducing the variety of suggested items.

Therefore, alongside collaborative filtering, knowledge-based methods have been introduced, and hybrid models integrating multiple recommendation techniques are increasingly adopted. Among these approaches, knowledge base-driven studies have gained increasing attention. Uta et al. (2024) demonstrate that knowledge-based RSs incorporate user preferences and enhance accuracy through domain-specific knowledge and rule-based mechanisms. Hegiansyah and Baizal (2023) employed ontologies in RSs to map user requirements to smartphone specifications, allowing an interactive agent to suggest suitable products. Subsequently, ontology-based RSs have been combined with collaborative filtering techniques. Darjanto and Baizal (2024) improved a camera recommendation system by combining ontology-based user requirement mapping with collaborative filtering to refine product suggestions.

RSs are a prominent domain where AI is extensively utilized. These systems leverage various AI techniques and theories for user profiling and preference discovery (Zhang et al, 2021, p. 439). Verma and Sharma (2020) introduced the concept of AI-based recommendation systems and explored various approaches, including collaborative filtering and content-based recommendation methods. In particular, their study focused on leveraging AI to mitigate key challenges in collaborative filtering-based RS, such as the cold start problem, data sparsity, and scalability issues. Nevertheless, because of the exploratory nature of their research, the study does not provide concrete implementations or detailed improvement strategies for AI integration. Additionally, it does not address CRSs based on generative AI.

Since 2024, research on generative AI-based CRSs has increased. This growth is driven by advancements in generative AI’s natural language processing capabilities and its improved ability to retain conversational context through prompts. Ayemowa et al. (2024) conducted a systematic review comparing traditional AI-based RSs with generative AI-based RSs. Their findings indicate that generative AI-based RSs outperform traditional AI-based systems in both recommendation accuracy and adaptability (p. 87743). The study also identified key challenges inherent in traditional AI-based RSs, including data sparsity, cold start, and diversity limitations.

As the importance of user feedback and human involvement in evaluating RS performance grows, this trend has been further amplified by the widespread adoption of generative AI-driven, prompt-based interfaces. Pramod and Bafna (2022) conducted a systematic literature analysis on CRSs, highlighting that recent research increasingly emphasizes user preferences and experiences as critical factors. Chen et al. (2025) proposed evaluation methodologies for CRSs that prioritize user interaction over traditional rule-based metrics such as Recall and Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU), which is commonly used in machine translation evaluation. Similarly, Manzoor et al. (2024) examined the effectiveness of generative AI models, particularly GPT-based CRSs, by comparing them with traditional approaches. Focusing on the movie RS, their study found that ChatGPT’s responses were perceived as more meaningful than those from earlier systems. Moreover, the study underscores the essential role of human involvement in assessing CRSs.

While most CRS research evaluates performance using predefined datasets and benchmarks, this study incorporates human participation across multiple stages—from dataset construction to feedback-driven refinement. It uniquely evaluates hallucinations in AI-generated recommendations and implements specific mitigation strategies. Rather than relying on conventional datasets, it utilizes structured metadata from a KOS registry, integrating generative AI with metadata-driven recommendations to improve performance through iterative user feedback.

Generative AI services, such as ChatGPT, are increasingly supporting human activities across both everyday and specialized domains. As the influence of generative AI expands, new challenges that were initially overlooked are now gaining attention. The tools we use to make decisions and perform specific tasks are, in turn, shaping human behavior and cognition. Long before the rise of generative AI, McLuhan (1964) emphasized this phenomenon with the phrase “The medium is the message”, highlighting how new media reshape both individual experiences and societal structures. This concept was first introduced as the title of the opening chapter in Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man and was later reinterpreted in The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects (McLuhan et al, 1967). While initially applied to technologies such as television and the Internet, this perspective is equally relevant to generative AI.

Park (2024a, p. 23), citing McLuhan, noted that media-driven societal changes often unfold before people fully comprehend the nature of the medium itself. Similarly, users interact with generative AI via prompts and application programming interfaces (APIs) without necessarily understanding how the responses are generated. This lack of transparency raises critical concerns regarding the reliability and interpretability of AI-driven knowledge production. Among the most pressing issues in this context is hallucination. Mitigating hallucination in generative AI systems such as ChatGPT requires actively integrating external knowledge bases. Park (2024a, p. 312) argues that “allowing general AI systems to access knowledge databases during task execution can enhance the reliability of language model outputs”. Accordingly, access to credible knowledge databases is essential for reducing hallucinations in AI-generated content.

Beyond hallucinations, a significant challenge in AI learning is the increasing reliance on AI-generated training data. As AI-generated content proliferates, a growing proportion of web data—the primary source for AI training—now consists of outputs created by AI systems themselves. For example, when AI-generated summaries or synthesized content is published online, it may be recycled as training data for future AI models. Given the accelerating proliferation of AI-generated data on the Internet, most future models will inevitably rely on data collected from web sources. Shumailov et al. (2024) predict that if this trend persists, AI models will increasingly be trained on data generated by earlier AI models, rather than on original human-created content. Their research on AI-generated image training shows that when a generative model learns from its outputs, data quality gradually degrades, ultimately reducing model performance. This phenomenon, known as model collapse, refers to the progressive degradation of data quality when models are repeatedly trained on self-generated data, eventually leading to the regression of generative models.

This challenge also poses a broader societal concern. Park (2024a, pp. 248–250) refers to this as “the disappearance of the original”, arguing that as AI becomes increasingly embedded in problem-solving, human discourse and contributions to online platforms diminish. As fewer individuals produce original content, AI-generated material gradually replaces human input, perpetuating a cycle that intensifies model collapse. In the context of training data for RSs, human-generated data remains superior to AI-generated content, underscoring the critical importance of original, human-curated information. Shumailov et al. (2024, p. 755) reinforce this view, stating that “the value of data collected about genuine human interactions with systems will be increasingly valuable in the presence of Large Language Model (LLM)-generated content in data crawled from the Internet”. Therefore, enhancing the performance of generative AI-based recommender systems and mitigating hallucinations requires prioritizing human-generated data as the foundational source for training and recommendation. Pretrained models and AI-generated outputs may serve as supplementary elements, but they must be grounded in a reliable foundation of human-curated data to ensure both accuracy and trustworthiness.

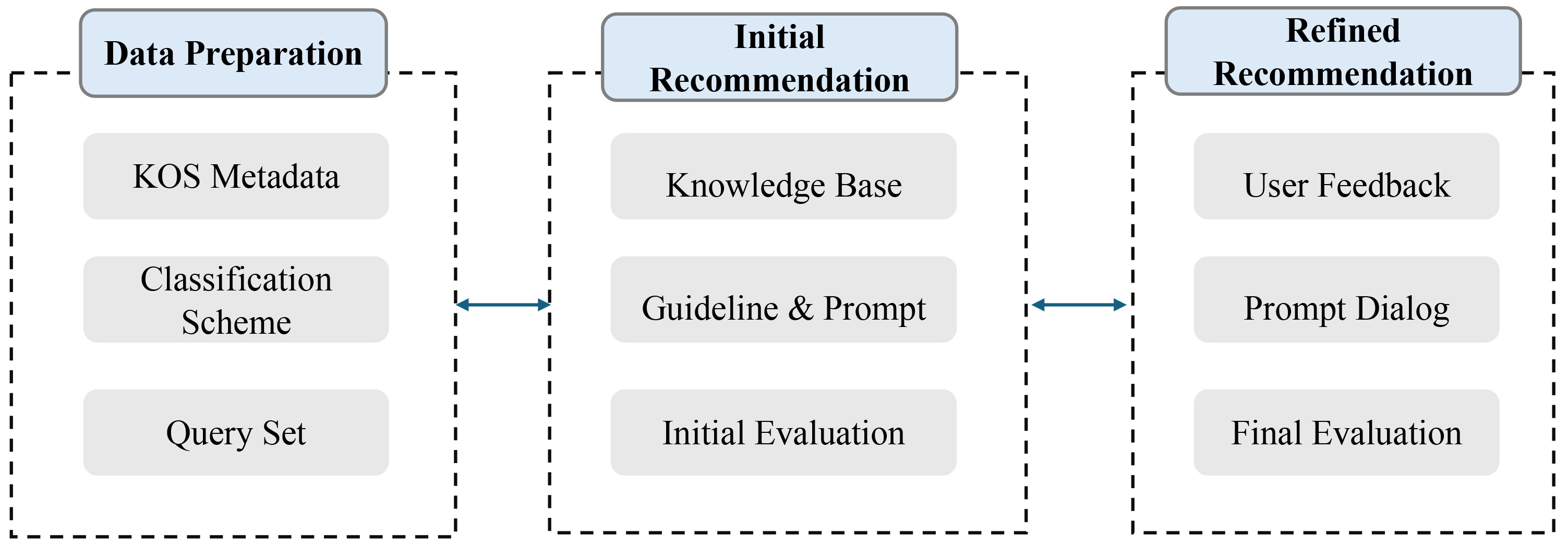

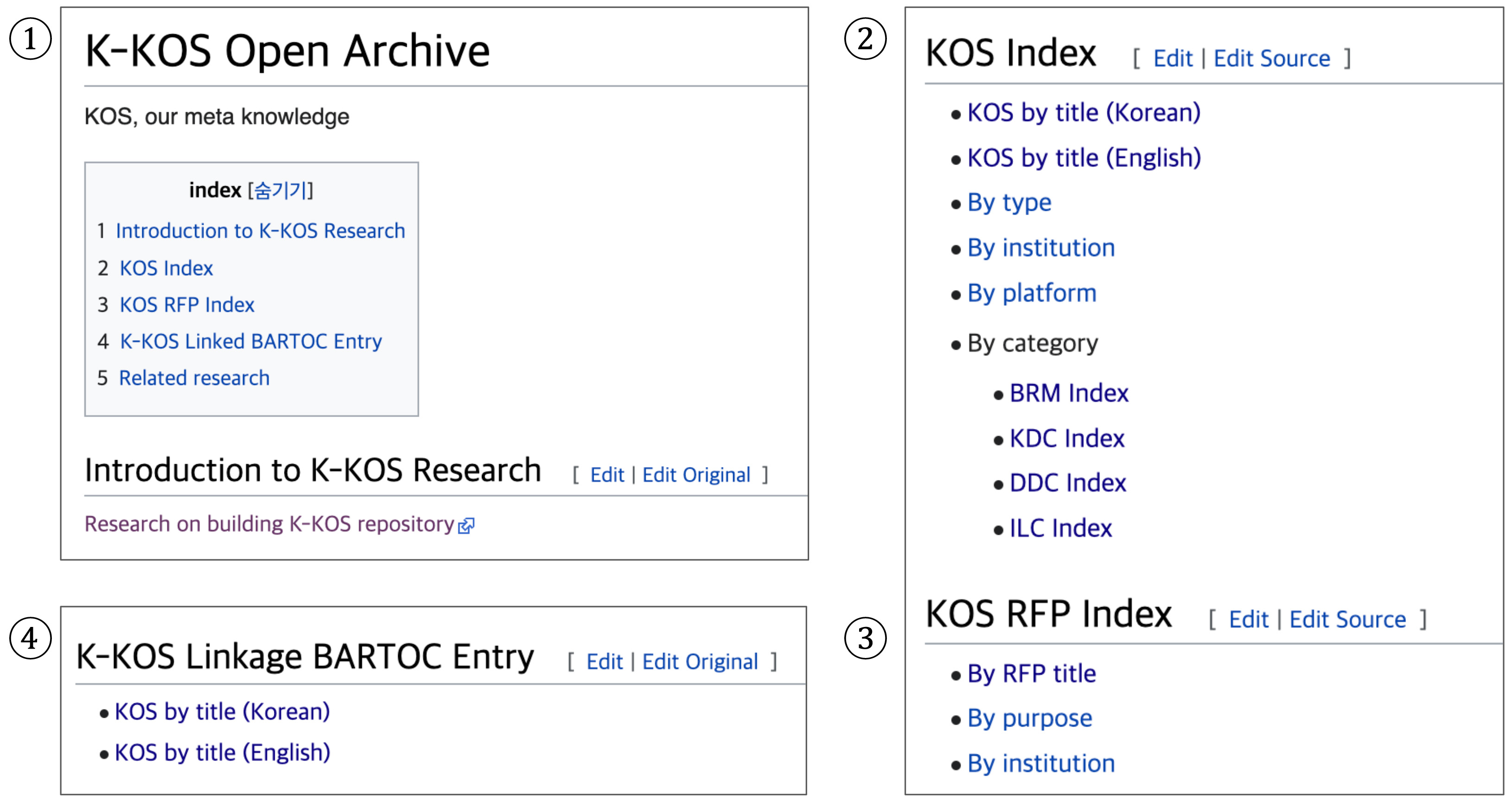

This study integrates KOS registries with generative AI to enhance retrieval and recommendation performance. The proposed methodology comprises three components: data sources, AI processing, and user interaction. Fig. 4 illustrates the overall research design, outlining the process of AI-based recommendation. The framework comprises three key phases: Data Preparation, Initial Recommendation, and Refined Recommendation. The Data Preparation phase involves curating KOS metadata, classification schemes, and an initial query set, all of which form the foundational knowledge base for AI-driven recommendations.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Overview of research design: AI recommendation process.

In the Initial Recommendation phase, the generative AI system is configured with predefined knowledge sources, recommendation guidelines, and structured prompts. This phase operates as a nonpersonalized recommendation system, retrieving relevant KOSs based on structured metadata instead of user-specific preferences. By analyzing predefined metadata and classification schemes, the AI identifies KOSs that align with the given query, ensuring efficient and structured knowledge discovery. An initial evaluation is conducted to assess the baseline performance of the recommendation system.

Finally, the Refined Recommendation phase incorporates user feedback through interactive prompt-based dialogues, enabling iterative refinement and evaluation. At this stage, user interaction transforms the system into a personalized recommender model by refining AI outputs through feedback-driven adjustments. By integrating additional user-provided context, the AI dynamically adapts its recommendations, thereby enhancing both accuracy and relevance in KOS discovery. This structured approach ensures that AI-driven KOS recommendations evolve dynamically, aligning with user needs while mitigating potential hallucination in generated outputs.

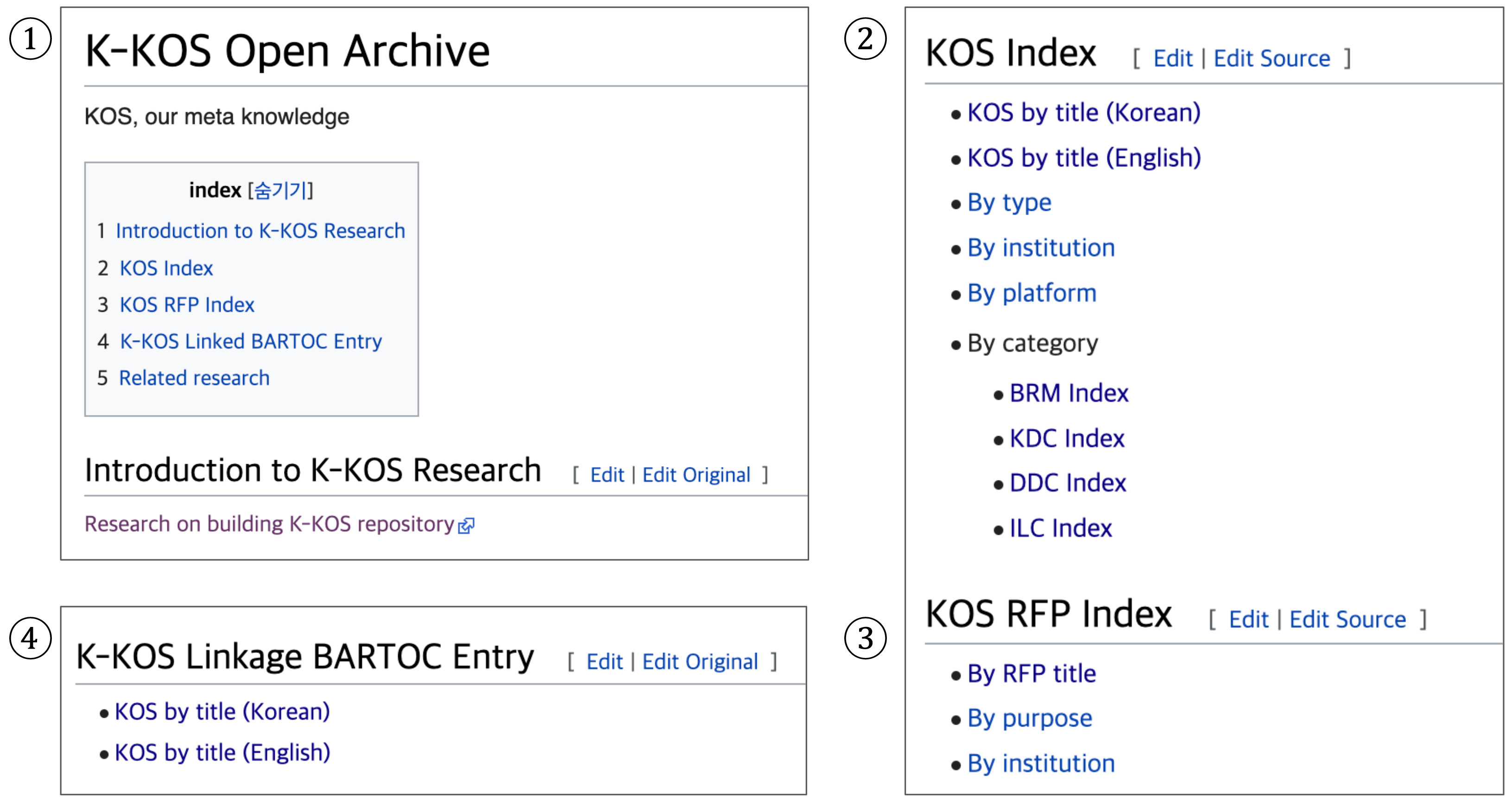

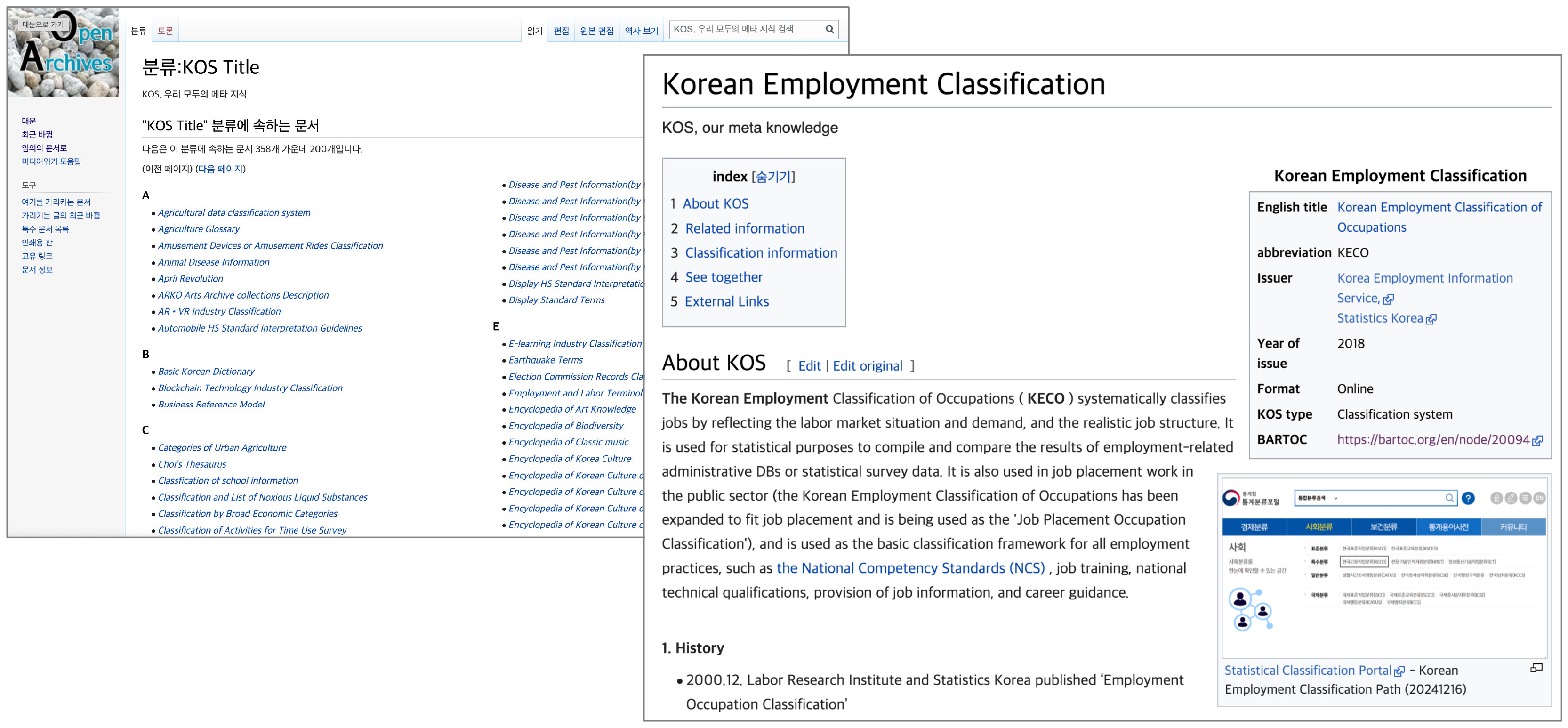

In this study, the KOS metadata utilized as the knowledge base was extracted from the Korean KOS registry, K-KOS Open Archives. This platform collects and organizes Korean KOS metadata while providing public access through a web-based service (Hansung University K-KOS Metadata Project Team, 2025). Fig. 5 presents the main interface of K-KOS Open Archives, automatically translated by Google Chrome, illustrating its key components. The title page (①) includes the registry name along with a comprehensive index that categorizes metadata into sections such as KOS Index, KOS Request for Proposal (RFP) Index, and K-KOS Linked BARTOC Entry. It also features a research project introduction menu, providing an overview of ongoing initiatives. The KOS Index section (②) offers a more detailed categorization of metadata, organizing it by title, type, institution, platform, and category. It includes classification schemes such as the Business Reference Model (BRM), Korean Decimal Classification (KDC), Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC), and Integrative Levels Classification (ILC). The KOS RFP Index section (③) further categorizes metadata by title, request purpose, and institution. Lastly, the interface includes a linkage menu (④) that connects K-KOS metadata with the BARTOC KOS registry, facilitating interoperability across metadata repositories.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Korean KOS (K-KOS) open archives main page (http://openarchives.net/). BARTOC, Basic Register of Thesauri, Ontologies & Classifications; BRM, Business Reference Model; KDC, Korean Decimal Classification; DDC, Dewey Decimal Classification; ILC, Integrative Levels Classification; RFP, Request for Proposal.

This structured metadata framework enhances retrieval efficiency and supports systematic knowledge organization, providing a robust foundation for diverse applications in KOS research and implementation. Fig. 6 shows the K-KOS title index page alongside the detailed entry for the example KOS “Korean Employment Classification”, as rendered via Google Chrome’s automatic translation. A more detailed structure of K-KOS entries is available in Park (2023, pp. 763–765), while the classification schemes and criteria for KOS categorization are addressed in Park (2024b).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

K-KOS list by English title (left) and individual KOS page, “Korean Employment Classification” (http://openarchives.net/wiki/index.php?title=Korean_Employment_Classification_of_Occupations).

Among these components, the metadata used for the RS includes the following:

• KOS title (available in both Korean and English); • KOS classification information (codes and labels); • KOS managing institution (in Korean); and • KOS descriptions (in Korean).

This study primarily focuses on descriptive metadata, which reflects the thematic structure of each KOS. Although administrative metadata—such as legal status, provenance, and access rights—is essential for ensuring metadata trustworthiness in digital environments, it does not directly influence subject classification. Future research may explore how administrative metadata can indirectly improve the reliability of AI-driven recommendation systems by enhancing metadata quality and provenance.

The experiment is designed to evaluate how different metadata levels affect the recommendation performance of generative AI systems. Four levels of metadata provision are defined in this study and summarized in Table 1.

| Level | Title | Classification | Description | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 0 | Baseline | |||

| Level 1 | O | Title Only | ||

| Level 2 | O | O | Title + Structured Metadata | |

| Level 3 | O | O | O | Title + Structured Metadata + Description |

For example, Table 2 provides the metadata associated with the KOS entry “Korean Standard Classification of Diseases”. Note that KOS_URL is included for evaluation purposes only and does not correspond to any specific metadata level.

| Element | Definition | Value | Metadata Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| KOS_ID | KOS identification number | AI212 | Level 1 |

| KOS_title_kor | KOS Korean title | 한국표준질병사인분류 | Level 1 |

| KOS_title_eng | KOS English title | Korean Standard Classification of Diseases, KCD | Level 1 |

| ILC_no | ILC2 number | mad, vm | Level 2 |

| DDC_no | DDC23 number | D616 | Level 2 |

| KDC_no | KDC6 number | K512 | Level 2 |

| BRM_no | Business Reference Model number | H001 | Level 2 |

| KOS_organization_kor | KOS managing institution | Statistics Korea (Translated from Korean) | Level 2 |

| KOS_desc | Simple description of KOS | This classification table, developed and provided by Statistics Korea, systematically categorizes disease morbidity and mortality data based on their similarities (…). (Translated from Korean) | Level 3 |

| KOS_URL | K-KOS Open Archives URL | http://openarchives.net/wiki/index.php?title=Korean_standard_Classification_of_Diseases | Not Applicable |

This study uses the most recent available versions of the KOS involved, including the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases (KCD), at the time of analysis. Although updates to a KOS can significantly alter its structure, terminology, and granularity, as observed in the transition from International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 to ICD-11 (Hong and Zeng, 2022; Zeng and Hong, 2022), which led to corresponding updates in the KCD, the classification codes used in this study remained consistent across versions. Therefore, version differences were not considered in the evaluation. Future research may investigate whether such changes, while not affecting domain categorization, could influence metadata structure or granularity, and whether KOS metadata should explicitly incorporate versioning to support more robust AI interpretation. Additionally, in Korea, a separate KOS called the Traditional Korean Medicine Classification (TKMC) has been developed to complement the international classification by covering areas not addressed in the ICD. Although not a version per se, the TKMC represents a significant structural divergence. In the K-KOS registry, the KCD and TKMC are registered as separate entries, linked through metadata as related yet distinct KOSs.

The KOS recommendation questions were categorized into three domains: Culture, Environment, and Healthcare. Each domain includes 1 general and 3 specific questions, totaling 12 questions. These questions are summarized in Table 3 below.

| Domain | Type | Question |

| Culture | General | KOS for managing cultural heritage |

| Specific | KOS for classifying and managing folklore culture | |

| KOS for managing data related to World Heritage registration | ||

| KOS for systematizing the types of traditional architecture | ||

| Environment | General | KOS for managing environmental data |

| Specific | KOS for classifying and managing environmental pollutants | |

| KOS for recording and preserving biodiversity data | ||

| KOS for systematically managing carbon emission data | ||

| Healthcare | General | KOS for managing medical information |

| Specific | KOS for systematically classifying and managing patient records | |

| KOS for standardizing medical device and equipment information | ||

| KOS for developing a disease diagnosis coding system |

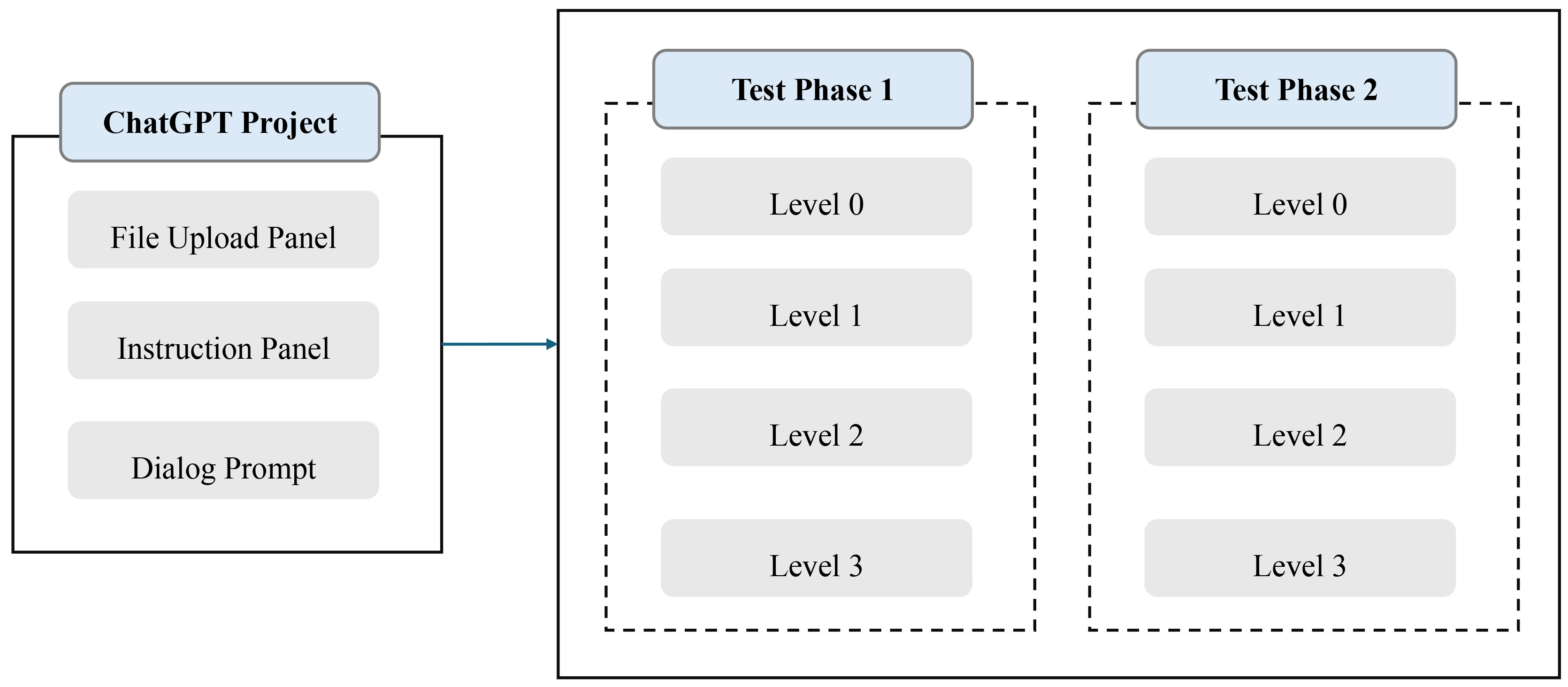

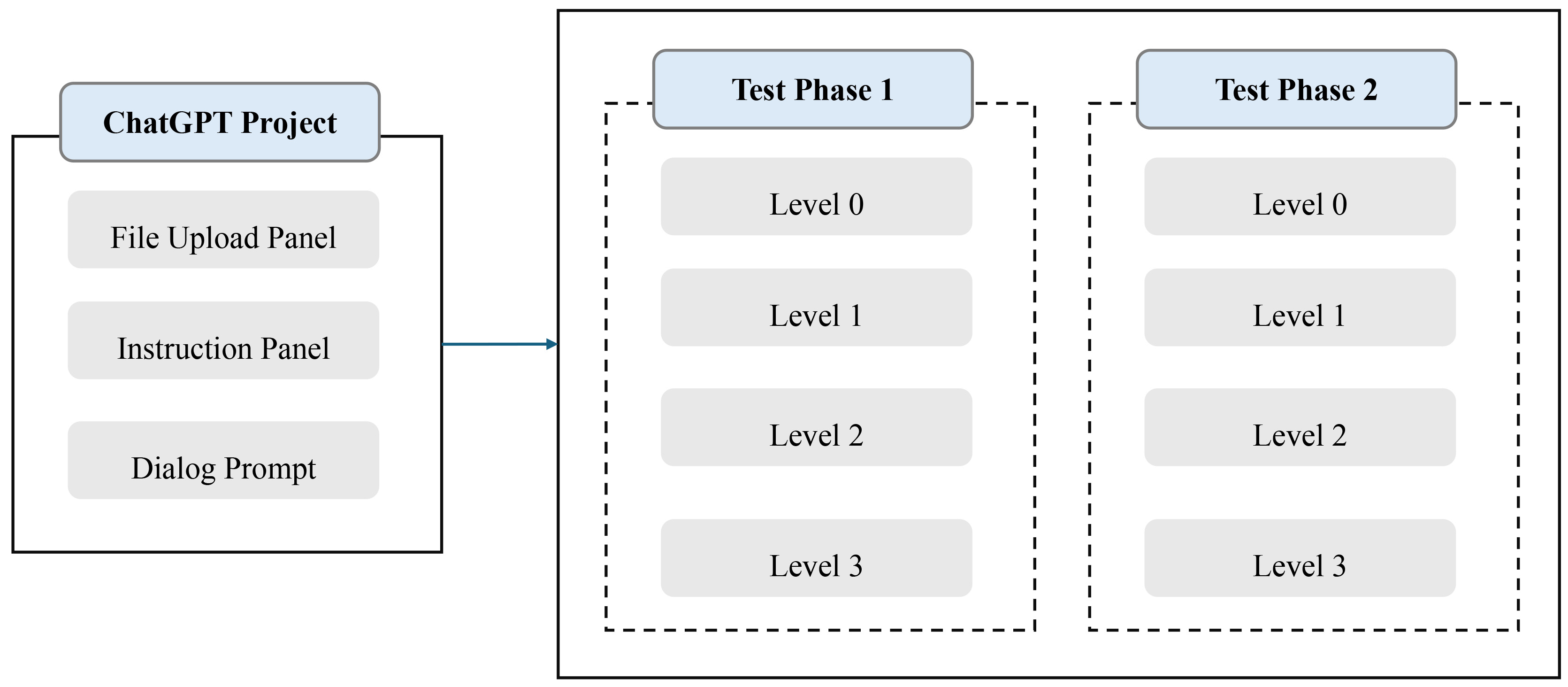

As shown in Fig. 7, the project creation process involved configuring separate environments for each metadata level. The experiment was conducted using the ChatGPT-4o model, with its project feature employed to create separate projects for each of the four metadata levels (Level 0 to Level 3). Each project consists of three main components: a file upload panel, an instruction input panel, and a chat interface (prompt window). Users can initiate a project by uploading files and entering initial instructions, which could be referenced in subsequent chats without requiring re-upload or repetition. Additionally, all files and instructions uploaded through the designated panels persist across all chat sessions within a given project. To ensure consistency in the recommendation results, KOS recommendations were generated twice per metadata level, resulting in a total of eight projects.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

ChatGPT project creation based on metadata levels.

Each project includes pre-uploaded KOS metadata files corresponding to its metadata level (Level 0 to Level 3), with additional classification scheme files for Level 2 and Level 3. The Project Instruction Panel outlines the KOS recommendation process by specifying evaluation criteria, recommendation steps, and output formats. It specifies the following components.

• Purpose and scope: Evaluation of AI-driven KOS recommendations and reduction of

hallucination risks. • Evaluation criteria: Assessment of relevance and hallucination likelihood for

the recommended KOS. • Recommendation guidelines: Generation of internal (metadata-based) and external

(AI-informed) suggestions. • Output format: Structured CSV files containing recommendation details. • Uploaded files: Metadata and classification files used for accurate KOS

matching.

After uploading metadata files according to their respective levels and defining project-specific instructions, recommendation queries were submitted via the prompt interface. Although a predefined question file was available for all levels except Level 0 (which required minimal configuration), the initial query and recommendation request were entered manually and reviewed before proceeding with the remaining queries in sequence. Each query submitted through the prompt interface was carefully examined to ensure alignment with the overarching project instructions. Additionally, when the KOS recommendation output failed to conform to the specified format, supplementary constraints were added to the prompt. Each metadata level follows a structured approach to generating KOS recommendations.

• Level 0: Processes all queries in question.csv using predefined

guidelines • Level 1: Prioritizes domain-specific recommendations using internal metadata

while adding up to five external recommendations • Level 2: Enhances internal KOS selection by considering classification data

(DDC, KDC, ILC, BRM) and managing institutions • Level 3: Builds upon Level 2 by incorporating descriptive KOS information to

improve relevance ranking

For a detailed breakdown of prompt queries, recommendation logic, and output structure, refer to Prompt Query Specifications. In addition to predefined project-specific queries, supplementary conditions were occasionally incorporated directly into the prompts. To improve Level 0 recommendations, adjustments were made to ensure the inclusion of Korean-language KOS, as the initial results lacked such an entry. For Levels 1 to 3, constraints were implemented to regulate the number of recommendations. The maximum number of internal KOS suggestions was capped at 20 to avoid excessive internal recommendations. Conversely, external KOS recommendations were often insufficient, so exactly five were required for each prompt.

The evaluation of KOS recommendation results is organized around two primary aspects: recommendation performance and hallucination likelihood. To ensure a systematic review, the scope and target groups are categorized as follows.

(1) Evaluation based on metadata levels and domains ◦ Recommendation performance is analyzed across different metadata levels and

domains to assess how variations in metadata depth affect accuracy and

reliability. (2) Evaluation of recommendations derived from internal and external data sources ◦ Internal recommendations are based on structured KOS metadata, whereas external

recommendations are derived from the AI’s pretrained knowledge. ◦ The evaluation compares the validity and consistency between these two

recommendation sources. (3) Evaluation by language context: Korean vs. non-Korean KOS recommendations ◦ The effectiveness of KOS recommendations is examined in terms of linguistic

context, comparing Korean-language KOS with non-Korean (primarily English) KOS.

◦ This analysis aims to identify potential biases in multilingual KOS

recommendations and evaluate their impact on overall recommendation quality.

By structuring the evaluation across these dimensions, this study offers a comprehensive assessment of how metadata levels, data sources, and linguistic variation influence the effectiveness and reliability of KOS recommendations.

To systematically assess the performance of the AI-based KOS RS, three key evaluation metrics were employed.

(1) Question suitability • Evaluates whether the recommended KOS is relevant to the input query. • Rated on a three-point scale: H (High), M (Medium), L (Low) • Calculation Formula:

(2) Data inclusion • Assesses whether the recommended KOSs exist in the internal dataset, regardless

of their relevance. • Calculation Formula:

(3) Actual existence • Determines whether the recommended KOS exists in reality, independent of dataset

inclusion. • Calculation Formula:

Among these criteria, Actual Existence is directly linked to hallucination likelihood, as nonexistent KOS recommendations indicate hallucination. Hallucination likelihood was assessed by comparing recommended KOS entries with the internal metadata set. Any KOS not found in the dataset was verified through a web search, confirming both its existence and reliability. Domain experts in KOS classification conducted these verifications collaboratively. Unlike question suitability assessments, this process did not require individual cross-validation among three experts, as the existence of a KOS is an objective fact. These three evaluation criteria ensure a structured assessment of recommendation quality, dataset accuracy, and hallucination mitigation in the AI-driven KOS recommendation framework.

Based on these criteria, recommendations are categorized into distinct labels to facilitate structured evaluation. While a greater number of recommendation types could be derived by combining the three evaluation metrics, this study defines six key labels, excluding cases such as dataset errors. Table 4 presents this classification framework, which ensures a structured assessment of recommendation quality, dataset accuracy, and hallucination mitigation, contributing to a more transparent and reliable AI-based KOS RS.

| Question suitability | Dataset inclusion | Actual existence | Label name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suitable | Included | Existent | Core Recommendation |

| Suitable | Not Included | Existent | Expanded Recommendation |

| Suitable | Not Included | Nonexistent | Hallucinated Recommendation |

| Unsuitable Included | Existent | Internally Mismatched Recommendation | |

| Unsuitable Included | Existent | Externally Mismatched Recommendation | |

| Unsuitable | Not Included | Nonexistent | Complete Hallucination |

To systematically compare AI-generated KOS recommendations, this study constructed a reference dataset by collecting expert evaluations on KOS relevance. For the 12 questions developed in this study, experts were allowed to select appropriate KOS entries freely from a pool of 342 candidates. Three experts with experience in literature and data classification independently completed the task under controlled conditions, enabling comparative analysis of their selections.

During the aggregation of results across all experts, a total of 318 KOS entries were recommended at least once, while at least 2 experts recommended 184 entries. Each expert recommended between 15 and 20 KOS entries per question, although the number of recommendations varied significantly depending on the question. Table 5 summarizes the number of KOS entries recommended per question. In the KOS_no attribute, the first value indicates the number of KOS entries recommended by at least one expert for each question. In contrast, the value in parentheses shows how many were recommended by at least two experts.

| question_no | KOS_no | question_no | KOS_no | question_no | KOS_no |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cul_g01 | 59 (19) | env_g01 | 31 (11) | med_g01 | 41 (25) |

| cul_s01 | 34 (30) | env_s01 | 13 (9) | med_s01 | 19 (17) |

| cul_s02 | 40 (5) | env_s02 | 12 (11) | med_s02 | 12 (9) |

| cul_s03 | 10 (3) | env_s03 | 11 (11) | med_s03 | 36 (34) |

These results serve as a reference baseline for evaluating the question suitability evaluation metric. If a KOS was considered relevant by at least two experts, it was classified as High (H) relevance. If only one expert found it relevant, it was classified as Medium (M). The count of entries recommended at least once includes those recommended multiple times. Thus, the exact number of entries recommended only once is derived by subtracting the value in parentheses from the total. Since each question_no is linked to a KOS_ID, this result enables the construction of a matrix indicating which questions are suitable for each KOS entry. For instance, the KOS_ID “AI212” corresponds to the Patient Classification System, which was recommended by three experts for the query med_s03, resulting in a Question Suitability value of “H”. Consequently, in the KOS metadata table, the row for KOS_ID “AI212” is assigned the value “H” in the med_s03 column. Using this approach, each KOS_ID can be mapped across question_no columns, with assigned values of “H”, “M”, or “L”. If a particular KOS is not recommended for a given question, meaning it is assigned neither “H” nor “M”, it is labeled as “L”. Since most KOS entries are unlikely to be relevant to multiple questions, “L” values predominate in the resulting matrix. Table 6 summarizes the distribution of Question Suitability values across all questions.

| question_no | H_count | M_count | L_count |

| cul_g01 | 19 | 40 | 283 |

| cul_s01 | 30 | 4 | 308 |

| cul_s02 | 5 | 35 | 302 |

| cul_s03 | 3 | 7 | 332 |

| env_g01 | 11 | 20 | 311 |

| env_s01 | 9 | 4 | 329 |

| env_s02 | 11 | 1 | 330 |

| env_s03 | 11 | 0 | 331 |

| med_g01 | 25 | 16 | 301 |

| med_s01 | 17 | 2 | 323 |

| med_s02 | 9 | 3 | 330 |

| med_s03 | 34 | 2 | 306 |

H, High; M, Medium; L, Low.

This classification framework serves as a benchmark for assessing the alignment between AI-generated recommendations and human judgment. By constructing this expert-evaluated dataset, the study establishes a reliable ground truth for the evaluation of AI-driven KOS recommendations. This dataset enables a structured comparison between human and AI recommendations, offering valuable insights into the consistency and reliability of AI-generated outputs.

Each metadata level (0–3) was tested across two separate iterations to account for variability in generative AI outputs. Performance was evaluated based on question suitability scores, and the iteration with the higher score was selected for further analysis. Table 7 presents the variation in responses between iterations across all metadata levels. To compare the two iterations, Question Suitability scores were quantified by assigning numerical values: H = 2, M = 1, and L = 0. The average score for each level was calculated, and the first iteration’s score was subtracted from that of the second. A positive average difference indicates superior performance by the second iteration, whereas a negative value suggests the first iteration was more effective. Average difference values were rounded to the fourth decimal place.

| Level | Average difference (2nd–1st) | Recommended iteration |

| lv0 | 0.075 | 2nd |

| lv1 | –0.247 | 1st |

| lv2 | 0.084 | 2nd |

| lv3 | –0.293 | 1st |

The number of recommended KOS entries was analyzed by question domain and metadata level, as summarized in Table 8. For Level 0, the generative AI was instructed to recommend five KOS entries without language restrictions and five specifically targeting Korean-language KOSs. For Levels 1 to 3, up to 20 KOS entries were recommended per query. As the number of Level 0 recommendations was fixed at 120, only Levels 1 to 3 were included in the summary. KOS entry counts for these levels are separated by slashes (/), with values in parentheses indicating entries deemed suitable by at least two experts. The table also demonstrates variation in recommendations across question domains, with the medical domain yielding the highest number across all metadata levels.

| question_no | Level (1/2/3) | question_no | Level (1/2/3) | question_no | Level (1/2/3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cul_g01 | 3/20/8 (19) | env_g01 | 6/15/7 (11) | med_g01 | 16/17/18 (25) |

| cul_s01 | 18/20/20 (30) | env_s01 | 4/20/6 (9) | med_s01 | 20/20/19 (17) |

| cul_s02 | 2/12/3 (5) | env_s02 | 3/13/9 (11) | med_s02 | 20/20/20 (9) |

| cul_s03 | 5/5/7 (3) | env_s03 | 7/16/11 (11) | med_s03 | 20/20/20 (34) |

Generative AI recommendations were further analyzed using evaluation metrics and compared against expert-validated KOS entries. Suitability scores, dataset inclusion, and actual existence rates were measured to assess the likelihood of hallucination. Table 9 presents the proportions of Question Suitability scores (“H” and “M”), along with Dataset Inclusion and Actual Existence rates across the four metadata levels. Level 0 serves as the baseline, where recommendations were generated without metadata and tested in two conditions: with and without language restriction for Korean KOS. At Level 0, the proportion of “H” and “M” scores in Question Suitability was relatively high. Nevertheless, only a small fraction of the recommended KOS matched the reference metadata, and the proportion of actually existing KOS entries remained low. When language was unspecified, the AI predominantly recommended English-based KOS entries, which showed higher accuracy and lower hallucination rates than Korean ones, despite the lack of metadata. Since Levels 1 to 3 utilized Korean KOS metadata, all recommendations were in Korean, and no language-based analysis was conducted.

| Level | KOS_count | Question suitability (%) | Dataset inclusion (%) | Actual existence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 0 | 120 | 88.33 | 3.33 | 57.5 |

| (Korean/Non_Korean) | (60/60) | (96.67/80.00) | (6.67/0.00) | (23.33/91.67) |

| Level 1 | 124 | 61.29 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Level 2 | 198 | 25.25 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Level 3 | 148 | 69.59 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

For Levels 1 to 3, the number of recommended KOS entries varied, with Level 3 showing the highest performance because of the inclusion of the most metadata. Dataset Inclusion and Actual Existence rates approached 100% across these levels, indicating minimal hallucination. However, Question Suitability showed a notable discrepancy: Levels 1 and 3 achieved similar scores in the 60% range, whereas Level 2 lagged significantly behind at 25%. These results suggest that generative AI generally adheres to the provided dataset when generating KOS recommendations from internal data. Therefore, incorporating external sources requires explicit instruction within the prompt. The notably low performance of Level 2, despite utilizing more metadata than Level 1, warrants further investigation.

By combining Question Suitability, Dataset Inclusion, and Actual Existence, recommendation class labels were assigned to each KOS entry. Table 10 summarizes the distribution of these recommendation labels across metadata levels. The six labels are defined as follows.

• Core Recommendation (Core_Rec)

• Expanded Recommendation (Exp_Rec) • Internally Mismatched Recommendation (Int_Mis_Rec) • Externally Mismatched Recommendation (Ext_Mis_Rec) • Hallucinated Recommendation (Hall_Rec) • Complete Hallucination (Comp_Halluc)

| Level | Core_Rec | Exp_Rec | Int_Mis_Rec | Ext_Mis_Rec | Hall_Rec | Comp_Halluc |

| lv0 | 4 | 52 | 0 | 13 | 50 | 1 |

| lv1 | 76 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| lv2 | 50 | 0 | 148 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| lv3 | 103 | 0 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Core_Rec, Core Recommendation; Exp_Rec, Expanded Recommendation; Int_Mis_Rec, Internally Mismatched Recommendation; Ext_Mis_Rec, Externally Mismatched Recommendation; Hall_Rec, Hallucinated Recommendation; Comp_Halluc, Complete Hallucination.

At Level 3, the most frequent category was Core Recommendations, representing accurate matches derived from internal metadata. Conversely, Hallucinated Recommendations were most prevalent at Level 0, where metadata was not provided. The relatively lower performance of Level 2 compared to Level 1 warrants additional analysis. However, the overall higher accuracy and significantly lower hallucination rates in Levels 1 to 3, compared to Level 0, confirm that metadata significantly improves recommendation quality.

This study analyzed the initial KOS recommendations generated by ChatGPT and identified several key issues requiring refinement.

(1) Language-Related Performance Variations: In the absence of predefined metadata,

the recommendations varied significantly depending on the language setting. When

no language restriction was applied, the AI predominantly recommended

English-language KOSs. However, when restricted to Korean, the recommended KOS

often featured seemingly appropriate titles that did not correspond to actual

systems. (2) Impact of Metadata on Recommendation Accuracy: The accuracy of KOS

recommendations improved proportionally with the amount of metadata provided. The

inclusion of structured KOS metadata in the prompt significantly reduced

hallucinations. Even with only KOS titles provided, the AI generally avoided

generating nonexistent entries. This confirms that systematically curated

metadata helps minimize hallucinations in AI-generated recommendations. However,

despite the inclusion of classification data at Level 2, the expected improvement

in performance was not realized. Among all domains, the medical field, supported

by the most structured KOS, yielded the highest number of recommended and

relevant entries. (3) Patterns of Hallucinated Recommendations: Hallucinated recommendations were most

frequently observed at Level 0, where no additional metadata was available.

Notably, hallucinations occurred more frequently for Korean KOS than for English

KOS. These hallucinations can be categorized as follows. • Type 1: Overgeneralized but nonexistent KOS names • Type 2: KOS names that appear Korean but are actually translated versions of

English KOSs • Type 3: KOS names similar to actual KOSs but not exact matches • Type 4: Titles related to KOS but representing projects rather than actual KOS

These findings highlight two key areas for refinement: (1) enhancing metadata utilization to improve recommendation accuracy and (2) reducing hallucinations through iterative feedback mechanisms. Refinement requires the use of structured prompts to analyze erroneous outputs and guide the AI toward more accurate responses.

During the research design phase, Level 2—which incorporated classification and institutional metadata—was expected to outperform Level 1 (title-only) but remain below Level 3 (which included descriptive metadata). However, test results showed that Level 2 underperformed relative to expectations, ranking only slightly above Level 0. To address this issue, iterative feedback was delivered through structured prompts to diagnose and enhance Level 2’s recommendation performance. Level 2 incorporated classification codes stored in a separate file, rather than embedding them directly within the primary KOS metadata file. The AI was instructed to reference multiple files concurrently while generating recommendations. A structured prompting strategy was implemented to identify and resolve potential issues. Extensive dialogue was exchanged, and ChatGPT’s responses were refined iteratively through multiple feedback loops. Selected examples from this process are as follows.

(1) Verifying Metadata Linkage

• Prompted AI to list all uploaded files, including attribute names and value

types. • Verified correspondence between classification attributes in kosmeta_level3.csv

and classification files. • Adjusted parsing logic to properly handle comma-separated values and map them to

classification terms.

(2) Improving Classification Matching and Hierarchical Context

• Checked if classification labels were utilized as indexing terms for KOS

recommendations. • Analyzed the hierarchical structure of classification codes for

broader-to-narrower inference. • Compared labels across systems to determine shared classification criteria.

(3) Reevaluating KOS Recommendations

• Asked AI to justify the exclusion of specific KOS entries. • Required AI to append the selection rationale to each recommended KOS. • Refined prompt constraints to prevent the inclusion of domain-inappropriate KOS.

(4) Expanding Recommendations Based on Refined Criteria

• Enabled the use of pretrained knowledge and external web search; required the

inclusion of source URLs. • Encouraged query refinement by suggesting additional relevant keywords.

Through systematic validation of metadata integration, classification utilization, and recommendation logic, Level 2’s recommendation performance was incrementally improved. These refinements underscore the essential role of expert intervention in directing AI-driven recommendations. Moreover, meticulous documentation of metadata structures and their interrelationships is essential to ensure reproducibility and accuracy in AI-assisted KOS expansion.

To address high-hallucination cases, structured feedback was iteratively applied to improve the AI’s recommendations. This process focused on three primary strategies.

• Addressing Hallucinations via Iterative Feedback: AI-generated hallucinations

were identified and corrected through sequential prompting, with responses

refined step-by-step. • Verifying Pretrained and External Data Sources: When no predefined dataset was

available, the AI was guided to refine its recommendations via web searches, with

explicit instructions to include URLs for source validation. • Ensuring Consistency in External Data Recommendations: When recommendations were

sourced externally, consistency was ensured by verifying that identical prompts

produced reproducible outputs.

Hallucinated recommendations were systematically refined through iterative prompting. The following illustrates an example of refining KOS recommendations for biodiversity conservation in the environmental domain.

(1) Initial Prompt: The AI was asked to recommend a Korean-language KOS relevant to

biodiversity conservation, including the KOS_ID, name, managing institution, and

source URL. (2) Second Prompt: The AI’s output was reviewed, and one incorrect recommendation

was selected for justification and further analysis. (3) Third Prompt: The AI’s explanation was analyzed, and misleading classifications

were identified, prompting additional refinement through targeted queries. (4) Fourth Prompt: Duplicate recommendations were identified, prompting a reduction

in the number of requested KOS entries from five to three. (5) Final Prompt: The AI returned three refined recommendations, whose validity was

subsequently verified through external sources.

By applying this iterative feedback loop, the final set of recommended KOSs included relevant entries absent from the original internal dataset. These results were classified under the “Expanded Recommendation” category, demonstrating that generative AI can effectively support KOS registry enhancement when carefully guided. This underscores the critical importance of expert oversight in validating AI-generated recommendations.

Generative AI, which leverages vast pretrained datasets and real-time web exploration, demonstrates enhanced recommendation performance and reduced hallucination rates when structured metadata is systematically utilized. The key contributions of this study are summarized as follows.

First, the study confirms that both the quantity and quality of metadata significantly influence the performance of generative AI and its capacity to mitigate hallucinations. Prioritizing high-quality, structured data while selectively incorporating external data remains essential even in the era of generative AI. The evaluation showed that hallucination rates declined sharply beginning at Level 1, where only KOS titles were provided, with the highest performance observed at Level 3, which included the most comprehensive metadata. In contrast, Level 0, which lacked metadata entirely, exhibited a particularly high hallucination rate for Korean KOSs. This finding underscores the necessity of metadata provision, especially for languages and domains with limited prior AI training data.

Second, the study confirms that prompt engineering effectively improves generative AI recommendation performance and reduces hallucination rates. Iterative prompt adjustments significantly enhanced the performance of Level 0, which had the highest hallucination rates, and Level 2, which exhibited a relatively high proportion of unsuitable KOS recommendations. In high-hallucination scenarios, prompt-based feedback enabled a detailed assessment of recommendation criteria and KOS suitability, leading to the discovery of new KOS entries not initially present in the metadata but relevant to the query. In cases of lower performance, prompts helped assess metadata connectivity and utilization, allowing the exclusion of irrelevant recommendations.

Third, the study emphasizes the essential role of expert involvement in constructing high-quality metadata and evaluating AI-generated recommendations. Generative AI interacts with humans via interfaces such as prompts, meaning that both the requester and the user of the recommendations play a crucial role in defining KOS requirements and validating results. Experts are essential in determining metadata structures, setting evaluation criteria for initial recommendations, and verifying both intermediate and final outputs through prompt-based adjustments. Ultimately, expert intervention proves invaluable in metadata construction, recommendation evaluation, and iterative refinement through feedback.

As a less globally dominant language, Korean poses greater challenges for generative AI, primarily because of higher hallucination rates. However, this focus enabled the identification of hallucination patterns and the development of feedback mechanisms tailored specifically to Korean KOSs. Future research should extend to English-language KOSs, enhancing the generalizability of findings. As the K-KOS Open Archives is developing links with BARTOC, comparative analyses between Korean and global KOSs could reveal structural and cultural variations in recommendation behavior.

This study also found limitations at Level 2, where classification metadata was underutilized during initial recommendations. Given its ability to link and expand semantic topics, often more effectively than technical metadata, future work should explore ways to integrate classification metadata from the outset and assess its impact through controlled testing.

Additionally, recommendation accuracy could benefit from a hybrid approach to data integration. While internal metadata alone may constrain generative AI’s potential, incorporating external data increases hallucination risk. Fine-tuning AI on structured internal metadata before engaging external sources may offer a balance, enhancing performance while minimizing hallucination.

Finally, future research should consider how administrative metadata, such as provenance and access rights, can support trust and traceability in AI-driven recommendations. It is also worth exploring how version differences in a KOS may influence metadata structure or classification granularity, and whether explicit versioning should be recorded within metadata schemas.

AI, Artificial Intelligence; KOS, Knowledge Organization System; CRS, Conversational Recommender System; LLM, Large Language Model; RS, Recommender System; DDC, Dewey Decimal Classification; KDC, Korean Decimal Classification; BRM, Business Reference Model; ILC, Integrative Levels Classification; BARTOC, Basic Register of Thesauri, Ontologies & Classifications.

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The author confirms sole responsibility for the conception and design of the study, data collection, analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the manuscript, and approval of the final version. The author has read and approved the final manuscript and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The author thanks the K-KOS Metadata Project Team for valuable support in organizing and refining the dataset used in this study.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2023S1A5A2A03085177).

The author declares no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT-4o to evaluate the performance and hallucination risks of generative AI in K-KOS recommendation tasks, as well as to check spelling and grammar. All final judgments regarding the performance evaluation and hallucination classification of generative AI were made by the author in accordance with the study’s research design. In addition, the final version of the manuscript underwent professional language editing to ensure the accuracy of English expression, including grammar and spelling. The author takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.