1 Department of Histology and Embryology, Medical School of Nantong University, 226001 Nantong, Jiangsu, China

Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a severe medical condition resulting from trauma, disease or degeneration, leading to partial or complete loss of sensory and motor functions. Huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1) is a classical neuronal protein that plays a crucial role in the nervous systems. Although numerous proteins and molecules have been extensively studied, the mechanisms underlying SCI pathogenesis remain incompletely understood. This study aimed to elucidate how HAP1 modulates functional recovery and tissue repair post-SCI through a multifaceted experimental approach.

Immunofluorescence staining was used to evaluate the spatial distribution and expression levels of HAP1 in spinal cord. An SCI model was established to assess behavioral functions using the Basso Mouse Scale, forced swim, inclined plate and hot plate tests. Luxol fast blue staining was used to assess morphological repair. The protein and mRNA expression levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) were quantified post-SCI using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, respectively. To elucidate the functional role of HAP1 in the SCI process, BDNF injections and behavioral tests were performed. Finally, RNA sequencing followed by bioinformatics analyses (Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways and Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment) were performed to identify differentially expressed genes and signaling pathways associated with HAP1 in the SCI process.

HAP1 is abundantly expressed in spinal cord neurons and plays a crucial role in post-traumatic recovery. HAP1 deficiency significantly impairs both functional recovery and morphological repair following spinal cord injury. Comparative analysis revealed lower BDNF levels in HAP1 heterozygous (HET) mice than in wild-type (WT) controls post-injury. Exogenous BDNF administration partially rescued behavioral deficits in HET mice, indicating BDNF-dependent compensatory mechanisms. RNA-seq analysis identified 444 differentially expressed genes and potential pathways associated with HAP1 in the SCI process.

HAP1 significantly enhances functional recovery and morphological repair post-SCI through potentiation of BDNF signaling pathways. These findings position HAP1 as a novel therapeutic target for SCI treatment.

Keywords

- spinal cord injuries

- huntingtin-associated protein 1

- brain derived neurotrophic factor

- behavioral research

- pathway analysis

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a debilitating neurological condition marked by acute structural damage and progressive secondary pathological cascades, that lead to chronic disability and serious complications. This disorder imposes significant socioeconomic burdens and profoundly impairs a patient’s quality of life [1, 2, 3]. SCI pathogenesis involves: primary mechanical damage (structural disruption/cell death), with secondary cascades (apoptosis, glial scarring, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress) developing over subacute-chronic periods [1, 4, 5]. Despite significant progress in therapeutic strategies, including neurotrophic factor delivery and stem cell-based therapies, the effect of SCI treatment is still not ideal [6, 7, 8, 9]. This persistent therapeutic gap underscores the need to identify and validate novel molecular targets capable of synergizing with existing interventions and should be a priority direction for contemporary SCI research.

Huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1), first identified through its interaction with mutant Huntingtin (mHtt), is a neuron-specific scaffold protein existing as two alternatively spliced isoforms: huntingtin-associated protein 1A (HAP1A, 599 amino acids) and huntingtin-associated protein 1B (HAP1B, 629 amino acids), which differ in their C-terminal domains [10, 11]. HAP1 knockout (KO) mice display profound postnatal lethality within 5–7 days, primarily attributed to neurodegeneration and suppression of feeding behaviors [12]. Additionally, these mice demonstrate significant deficits in cognitive functions, including impaired spatial learning and reduced recognition memory [12, 13].

HAP1 has emerged as a scaffold protein that orchestrates diverse cellular processes, including: signal transduction, vesicular transport, transcriptional regulation, and membrane receptor recycling [14, 15, 16]. Mounting evidence demonstrates that HAP1 interacts with multiple trafficking proteins, including dynactin subunit P150Glued (P150Glued) [17], kinesin light chain [18], and kinesin family motor protein 5 [19]. These interactions enable HAP1 to coordinate bidirectional vesicular trafficking, particularly modulating the balance between retrograde and anterograde transport in neurons. Besides, HAP1 interacts with multiple receptors, including epidermal growth factor receptor,

This study demonstrated that HAP1 is predominantly expressed in spinal cord gray matter neurons, indicating neuron-specific regulatory roles. HAP1 heterozygous (HET) female mice exhibited significantly worse morphological and functional recovery post-SCI. Notably, exogenous BDNF administration rescued functional deficits in HET mice, confirming a pivotal role of BDNF in HAP1-mediated repair. RNA-sequencing reveals differentially expressed genes and potential pathways in SCI. These findings establish HAP1 as a master regulator of SCI recovery via BDNF-dependent pathways.

HAP1 genetically modified mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Strain #007749; Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). HET (heterozygous, HAP1+/-) mice were used to generate HET, KO (knockout, HAP1-/-) and WT (wild type, HAP1+/+) mice. Genotyping was performed through PCR using the following primers: WT 5′-TTTTGGAGGTCTGGTCTCGCTCTG-3′ and 5′-CGTCTTCCATCTTAGTGCGTTCAC-3′, and KO 5′-TTTTGGAGGTCTGGTCTCCGCTCTG-3′ and 5′-CTTCATGTGGATGCTAGGGATCC-3′. Given that KO mice exhibit postnatal lethality within several days [12], HET and WT littermates were used for experiments.

To avoid sex-specific complications (male-predominant urinary retention and mortality post-SCI) [26, 27, 28], only female C57BL/6 mice were used in this study.

Anesthetized mice were transcardially perfused with 0.9% NaCl and 4% paraformaldehyde (Beyotime, Hangzhou, China, P0099-3L) in PBS. T8–T10 spinal cord segments were isolated and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. Tissues were coronally cut into 14-µm sections and blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Beyotime, P0007) with 0.3% Triton X-100 (Beyotime, ST2776-1L) for 1 hour. Sections were immersed in primary antibodies against HAP1 (rabbit, 1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, cat#: PA5-20377), Nissl (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat#: N21483), Ibal1 (goat, 1:400, Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA, cat#: NB100-1028SS) and GFAP (mouse, 1:2000; Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA, cat#: MAB360) overnight. The following day, sections were dark incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with species-matched Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000 dilution; Cy3 affinipure goat anti-mouse IgG, cat#: 115-165-003, 1:800, Jackson, West Grove, PA, USA; goat anti-rabbit IgG fluorescein (FITC) cat#: 111-095-003, 1:800, Jackson). Ultimately, sections were stained with DAPI (cat#: h-1200, Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and coverslipped using mounting medium.

Mice (8 weeks, 23–25 g) were anesthetized and positioned in a stereotaxic frame. The T8–T10 vertebrae were exposed to visualize the dorsal spinal cord. The T9 spinal segment (primary impact zone) was operated on by dropping a 10 g rod (tip diameter: 1.5 mm; impact force: 50 kDyn, 1 Dyn = 10-5 N). Mice that received a laminectomy without injury were assigned to the sham group.

Prior to behavioral testing, all mice underwent a 30 min habituation to acclimatize to the experimental environment. Investigators were blinded to group allocation for behavioral assessment throughout the study.

Postoperative motor recovery was evaluated using the BMS, a validated scoring system for assessing hindlimb locomotor function [29, 30]. Higher score values indicated superior functional recovery (complete paralysis: 0, normal gait: 9).

Mice were forced to swim in a transparent glass tank (45

Hindlimb muscle strength was assessed in a rectangular glass chamber (45

Thermal nociception was assessed using a hot plate test (40 cm high chamber with a metal surface maintained at 55.0

Briefly, tissue sections were stained overnight at 56 °C in LFB (Beyotime, Hangzhou, China, C0631S) solution (0.1% LFB, 0.05% acetic acid in 95% ethanol), followed by sequential washes in 95% ethanol and differentiation in 0.05% lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) with 70% ethanol. After thorough rinsing in distilled water, differentiation was arrested by brief immersion in 0.05% Li2CO3. Dehydration was completed through a graded ethanol series (70%, 95%, 99%) to ensure optimal myelin visualization.

Total RNA was isolated from spinal cord tissue (2 mm around the T9 injury core) using the RNA-easy mini kit (cat#:74104, QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), followed by cDNA synthesis from 1 µg RNA with the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (cat#: K1622, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For qPCR amplification, we used the Bio-Rad CFX96 system with SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Shengkang, Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China) under standardized cycling conditions. The primer sequences for BDNF were F: 5′-CCCACTTTCCCATTCACCGA-3′ and, R: 5′-CCTTCAGCGAGAAGCTCCAT-3′, and for GAPDH, F: 5′-GAGGTAGTTATGGCGTAGTGC-3′ and, R: 5′-CTGGTTTCTGGAGGATGG-3′, with GAPDH used as the endogenous control. Relative quantification was calculated via the 2-ΔΔCT method after verifying amplification specificity through melting curve analysis.

Spinal cord tissue samples (2 mm around the T9 injury core) were dissected, homogenized in radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime, Hangzhou, China, P0013E) and centrifuged. Supernatants were collected and diluted 20-fold prior to analysis. BDNF concentration was quantified using a commercial ELISA kit (R&D Systems, cat#: DBNT00027620, Saint Paul, MN, USA) following manufacturer’s protocol, with absorbance measured at 450 nm (correction wavelength: 540 nm). Protein normalization was performed using bicinchonininc acid (BCA) assay results, with final BDNF levels expressed as pg/mL.

BDNF (Sigma-Aldrich) was initially prepared as a 5.0 µg/mL stock solution in 0.9% saline, aliquoted and stored at –80 °C to maintain stability. Immediately prior to intrathecal delivery, stock was diluted in saline to a final therapeutic concentration (20 ng/10 µL). At 7 days post-surgery, injections were performed between the L5–L6 vertebral interspace using a 30-G needle. The injection volume (10 µL) was delivered over 30 s followed by a 60-s needle retention period to ensure complete dispersion and prevent reflux. Normal saline was administered identically as the parallel control.

Spinal cord tissue samples (2 mm around the T9 injury core) were collected from HAP1 HET and WT female mice, with total RNA extracted using the QIAcube Automated System (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). RNA integrity was verified and sequenced at RiboBio Co. (Guangzhou, China). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyzed differentially expressed genes (DEGs, false discovery rate (FDR)

All quantitative data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) with appropriate statistical tests: unpaired t-test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison. All results are presented as mean

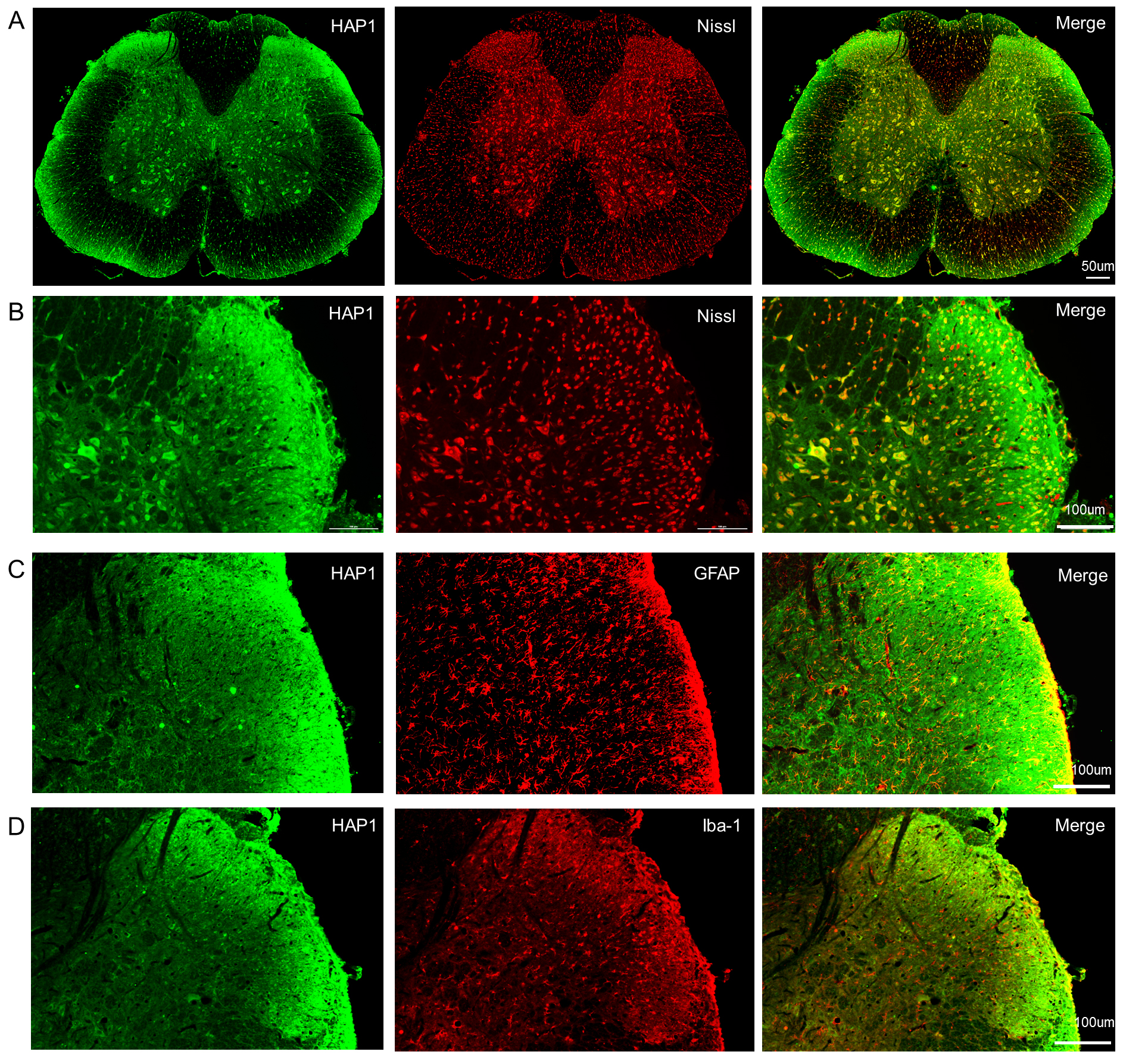

To characterize the distribution of HAP1, transverse spinal cord sections (T8–T10) were used for immunohistochemistry. HAP1 immunoreactivity exhibited selective enrichment in gray matter regions with minimal expression observed in white matter tracts (Fig. 1A). Double-label staining demonstrated robust colocalization of HAP1 with Nissl bodies, confirming its neuronal-specific expression pattern in spinal cord neurons (Fig. 1A,B). Negligible colocalization was observed between HAP1 and GFAP or Iba1 (Fig. 1C,D), further reinforcing the neuron-specific expression profile of HAP1 in the spinal cord.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Fluorescence staining of transverse spinal cord sections (T8–T10) from female mice. (A) HAP1 expression predominantly localized within gray matter regions, exhibiting strong colocalization with Nissl bodies (neuronal marker). Scale bars, 50 µm. (B) Enlarged images demonstrate significant spatial overlap between HAP1 and Nissl bodies in spinal cord neurons. (C,D) Double staining detected negligible colocalization between HAP1 and GFAP (astrocyte marker) or Iba1 (microglia marker). Scale bars, 100 µm. HAP1, huntingtin-associated protein 1; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein.

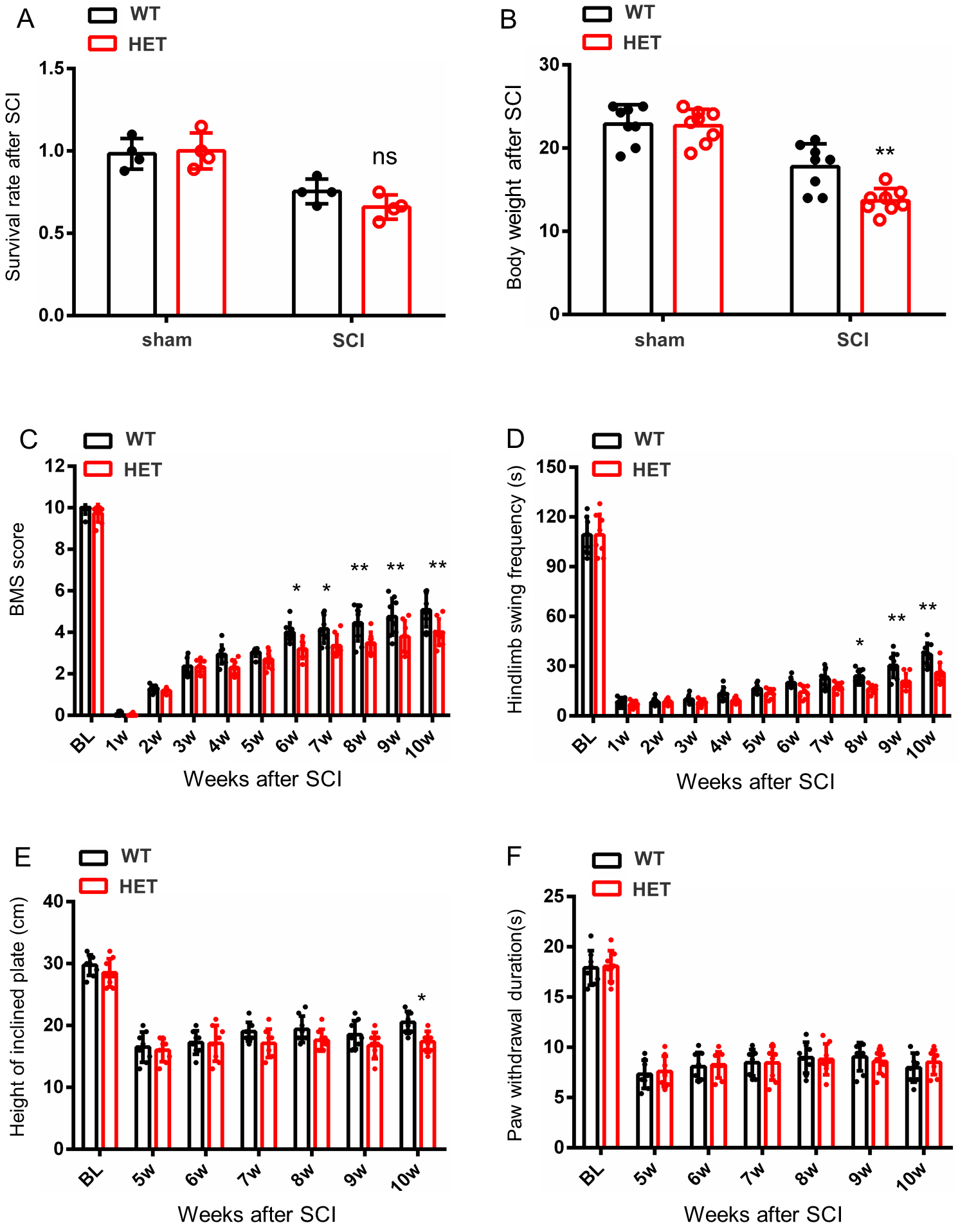

To elucidate the functional role of HAP1 in SCI recovery, HET mice were utilized due to postnatal lethality in KO mice [12]. HET mice exhibited normal motor function and growth, when compared with WT littermates and post-SCI survival rates showed no genotype-dependent differences. HET mice also displayed significant body weight reduction (Fig. 2A,B), indicating that HAP1 insufficiency may exacerbate injury-induced metabolic dysregulation. Behavioral analyses revealed functional recovery differences between the HET and WT groups. While WT mice demonstrated progressive hindlimb motor improvement, HET mice exhibited persistent motor dysfunction (Fig. 2C). This deficit manifested behaviorally as impaired buoyancy maintenance in forced swim tests and reduced postural stability on inclined plates (Fig. 2D,E).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Behavioral analysis of HET and WT female mice after SCI. (A) Survival rates were comparable between the WT and HET groups both pre- and post-SCI. (B) HET mice exhibited significant weight loss versus WT littermates. (C) BMS revealed enhanced locomotor recovery in WT mice compared with HET mice, with WT mice achieving higher BMS scores. (D) The Swim test showed superior performance in WT mice when compared with HET mice during the chronic phase of SCI. (E,F) No significant intergroup differences between WT and HET mice were found for the inclined plate or hot plate tests. Data are presented as mean

Notably, negligible differences in nociceptive thresholds were found between the HET and WT groups (Fig. 2F), highlighting HAP1’s selective requirement for motor recovery rather than sensory recovery. These results establish HAP1 as a critical regulator of locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury.

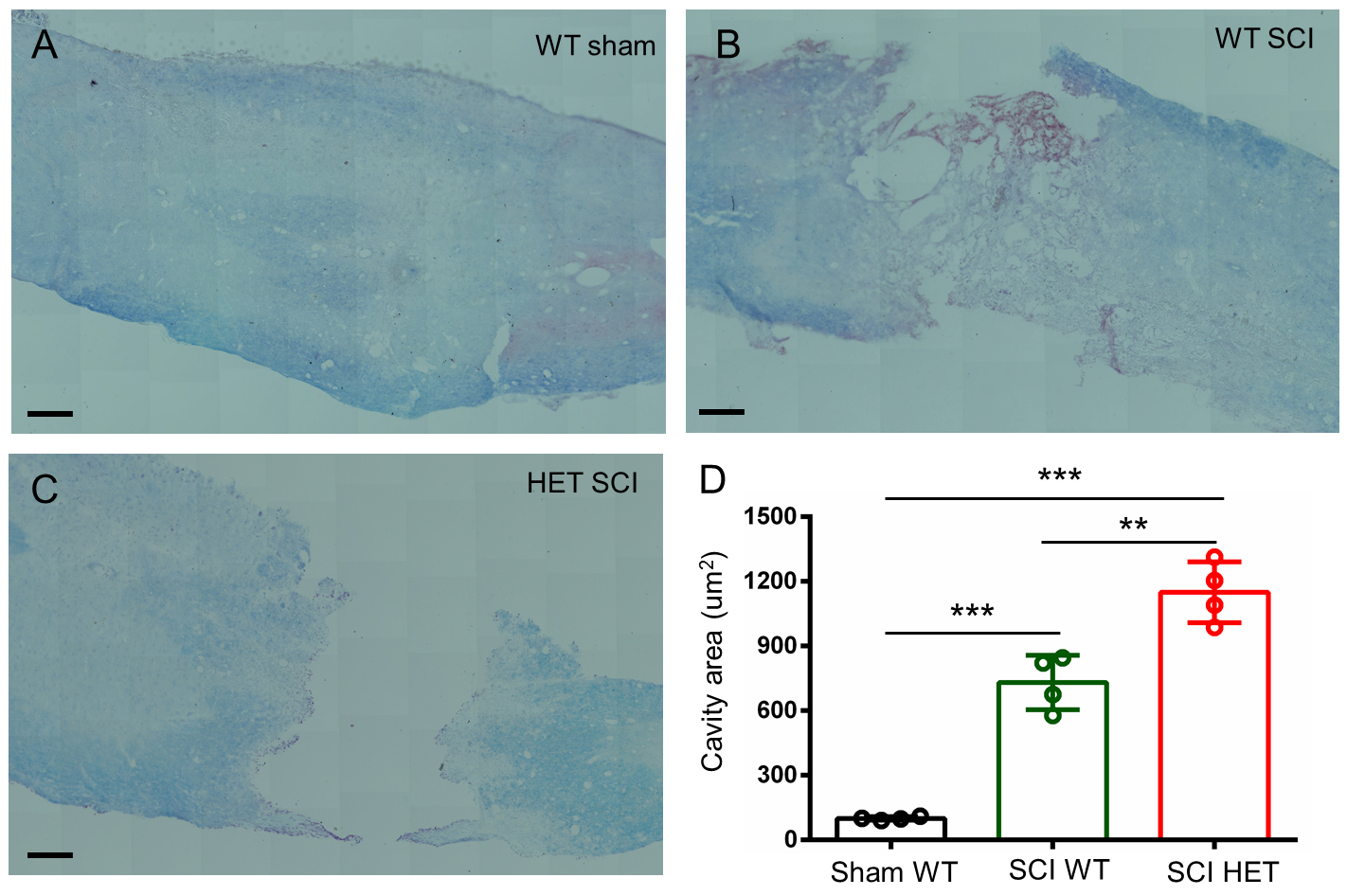

LFB staining of T8–T10 spinal cord sections at 1month post-SCI was performed to observe structural repair. Sham-operated WT mice exhibited intact architecture with sharp gray/white matter demarcation and robust myelin sheaths (Fig. 3A). Both WT and HET SCI groups exhibited characteristic necrosis, demyelination, and cystic cavitation at the injury epicenter (Fig. 3B,C). Lesion area analysis demonstrated that HET mice developed lesion volumes 33% larger than WT mice (Fig. 3D). HAP1 deficiency weakened structural repair and exacerbated secondary degeneration.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Histological analysis of T8–T10 spinal cord sections from female mice at 1 month post-SCI using LFB staining. (A) WT sham controls exhibited intact gray/white matter architecture and continuous myelin sheaths. (B,C) Both WT and HET groups showed severe tissue damage, characterized vacuolation, irregular cystic cavities and extensive demyelination. (D) Quantitative analysis demonstrated that HET mice developed larger cystic lesions than WT mice. Scale bars, 100 µm. Mean

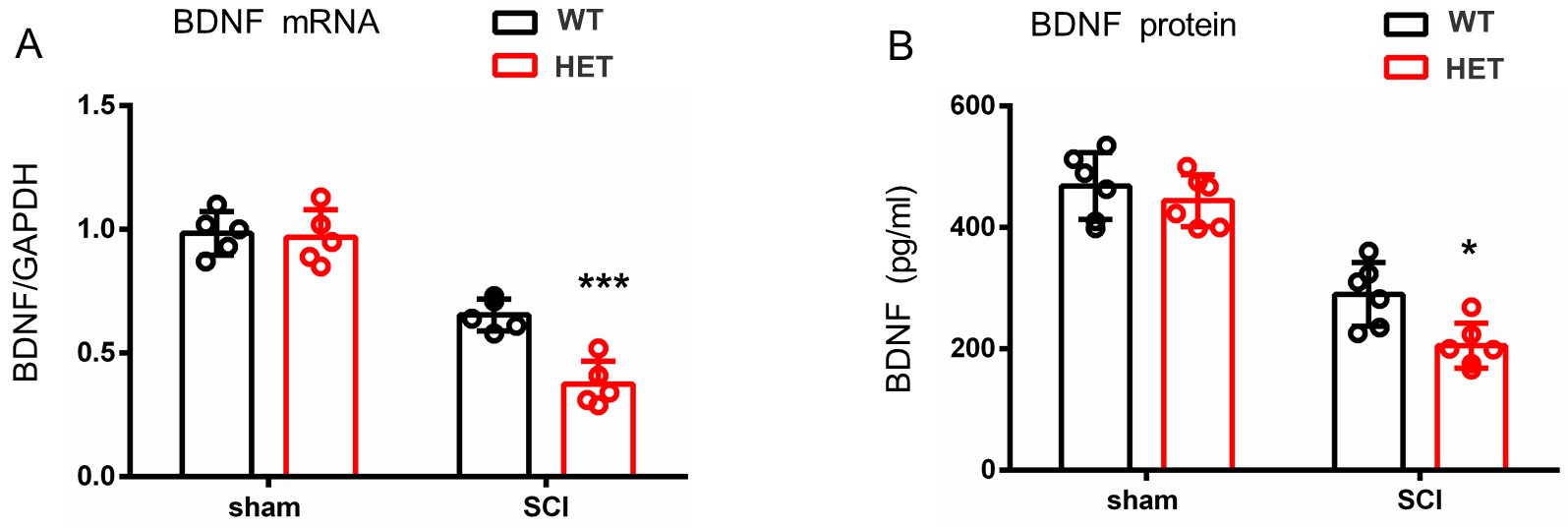

HAP1 serves as a critical neuronal trafficking regulator that facilitates the intracellular transport and activity-dependent secretion of BDNF, thereby establishing HAP1 as a master coordinator of neurotrophic signaling [15, 25]. BDNF levels in spinal cord (2 mm around the T9 injury core) were measured using qPCR and ELISA. It was found that WT and HET mice exhibited comparable baseline BDNF mRNA expression pre-SCI and both groups showed significant downregulation at 1 month post-injury, with HET mice displaying obviously exacerbated suppression (Fig. 4A). This dysregulation was mirrored at the protein level, where ELISA results demonstrated a greater decrease in mature BDNF in HET than in WT mice (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that HAP1 deficiency disrupts BDNF homeostasis during SCI pathogenesis, leading to insufficient neurotrophic support during critical recovery phases.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Quantitative analysis of the injured T9 spinal cord segment at 1 month post-SCI. (A) qPCR demonstrated a greater reduction of BDNF mRNA in HET than in WT female mice. (B) ELISA showed protein level suppression, with HET female mice exhibiting lower brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) than WT counterparts. Mean

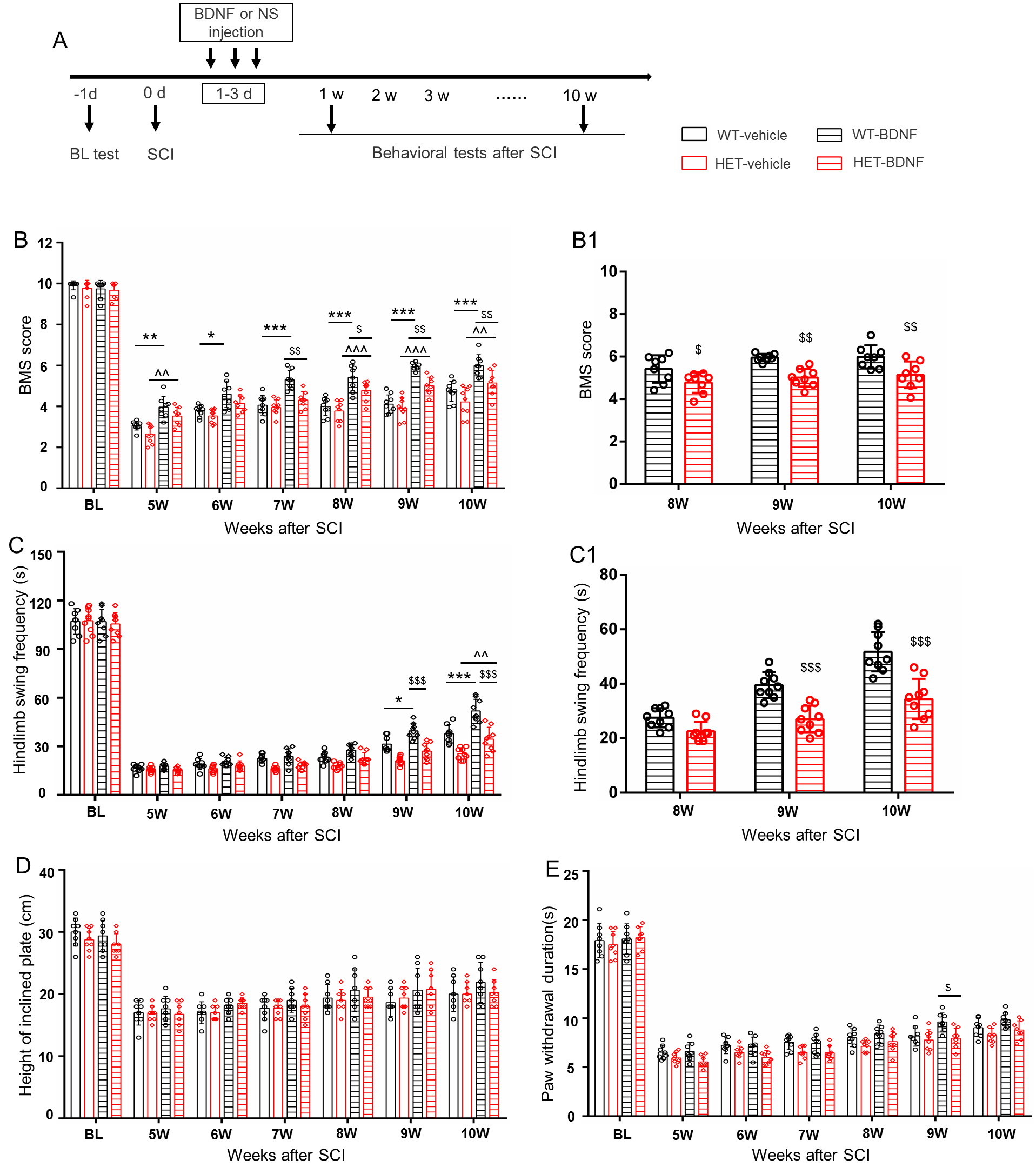

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of BDNF, WT and HET mice received daily intrathecal injections of 20 µg BDNF (in 10 µL saline) or vehicle (normal saline) for 3 consecutive days post-SCI (Fig. 5A). Behavioral assessment revealed that intrathecal BDNF administration specifically improved motor function in HET mice after SCI, as evidenced by time-dependent enhancements in BMS scores and swim test performance. Such improvements ultimately surpassed the recovery levels observed in the HET and WT vehicle groups by the chronic phase (Fig. 5B,C), while no significant improvements were detected in sensory or balance in the hot plate and inclined plate tests (Fig. 5D,E). This demonstrates that BDNF’s therapeutic effects are selectively targeted to motor circuit plasticity rather than generalized neurological recovery.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. BDNF enhances motor recovery in HET female mice post-SCI. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental timeline for BDNF/vehicle administration. (B,C) BDNF administration improved locomotor function in HET female mice after SCI in the BMS and swimming test, when compared with the HET and WT vehicle groups ((B1,C1) panels show function changes in the chronic stages). (D,E) No significant effects were observed in sensory (D) or static balance assessments (E). Mean

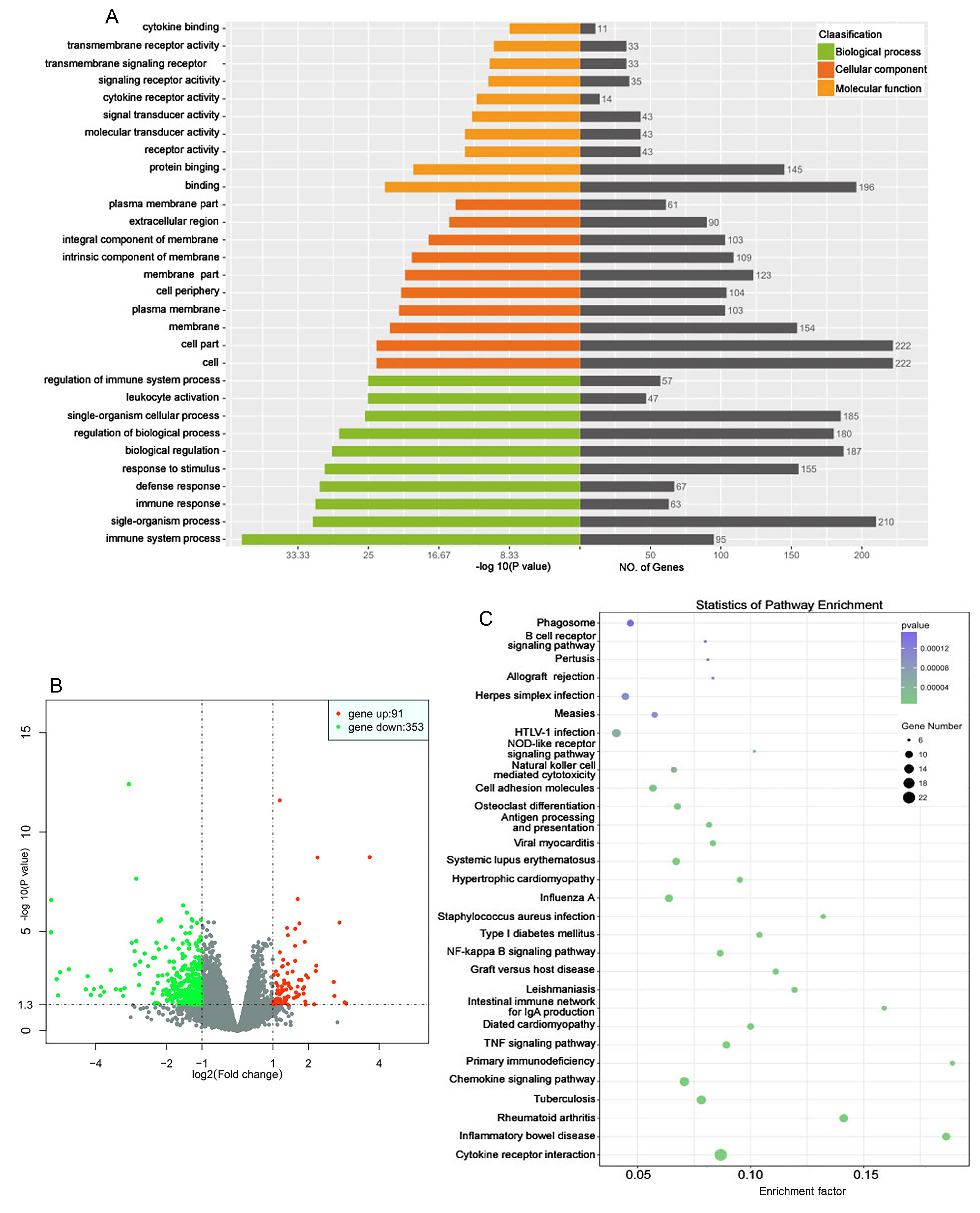

To explore the underlying mechanisms associated with HAP1, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed using RNA extracted from the T8–T10 spinal segments of WT and HET female mice 1 month after SCI. The genetic differences between the WT and HET SCI groups were analyzed from three perspectives: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. GO analysis revealed that upregulated genes in the WT group were primarily enriched in regulation processes and protein binding (Fig. 6A). DEGs were identified and resulted in 91 upregulated genes and 353 downregulated genes in the WT SCI group when compared with the HET SCI group (Fig. 6B). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed several pathways related to spinal injury, including the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Gene expression profiles of WT and HET female mice after SCI. The T8–T10 spinal segments were used for RNA-seq 1 month after surgery. (A) Gene ontology analysis revealed gene expression differences between the WT and HET groups. Upregulated genes were primarily enriched in regulation process and protein binding. (B) Volcano plot of significantly altered genes between the WT and HET groups. Red dot, gene up; green dot, gene down; grey dot, no significant difference. Fold change

SCI is a devastating neurological condition triggered by trauma, ischemia, or compression [31]. It initiates a complex pathological cascade characterized by irreversible neuronal death and reactive gliosis with scar formation and progressive cystic cavitation, ultimately leading to chronic sensorimotor deficits and debilitating complications including neuropathic pain, autonomic dysreflexia, and secondary infections [1, 6, 31]. Current therapeutic paradigms employ two complementary strategies: (1) neuroregenerative approaches (stem cell transplantation, biomaterial scaffolds) targeting neural circuit reconstruction through axonal regrowth facilitation and lesion site repair [32, 33] and (2) neuroprotective interventions (anti-inflammatory agents, Rho-kinase inhibitors) aimed at preserving spared neural tissue by mitigating apoptosis and demyelination [34, 35]. However, clinical translation remains hampered by the multidimensional nature of SCI pathophysiology, particularly the inhibitory glial microenvironment, deficient axonal guidance cues, and failed synaptic reintegration that collectively underscore the importance of deciphering the spatiotemporal dynamics of molecular and cellular mechanisms governing SCI progression in the development of effective combinatorial therapies.

As the structural and functional core of stigmoid bodies, HAP1 serves as both a defining component and critical biomarker of these neuroprotective organelles [36], with high expression in hypothalamic nuclei and hippocampal and spinal cord dorsal horn, thereby orchestrating multiple neuronal processes, including trafficking, endocytosis, postnatal feeding, and axon growth [37, 38]. Central nervous system (CNS) regions with high stigmoid body/HAP1 density demonstrate remarkable resistance to apoptosis, while HAP1 deficient zones consistently develop hallmark pathologies, including polyQ aggregates in Huntington’s disease, motor neuron degeneration in spinal muscular atrophy, and progressive Purkinje cell loss in spinocerebellar ataxias [37, 39]. While its important roles in the brain are well-documented [40, 41], this study explored the possible functions of HAP1 in the spinal cord. Immunofluorescence data demonstrated higher HAP1 intensity in gray than in white matter, colocalizing with Nissl+ neurons but complete absence in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP+) astrocytes or Iba1+ microglia, suggesting neuron-exclusive functions in spinal cord that may underlie its observed neuroprotection.

To investigate the functional role of HAP1 in the spinal cord and SCI, longitudinal behavioral assessments in HET and WT female mice were conducted over a 10-week post-injury period. Survival rates and general locomotor activity showed no significant intergroup differences during both pre-injury and acute post-injury phases. Given HAP1’s known involvement in insulin secretion regulation, body weight changes were analyzed throughout the 10-week observation period. Notably, HET female mice displayed significantly reduced weight gain when compared with WT littermates, suggesting a potential metabolic influence of HAP1 in the post-SCI recovery process. To assess motor functional recovery, BMS scoring and swim tests were employed. They revealed delayed hindlimb functional restoration in HET female mice relative to WT controls. However, no significant intergroup differences were observed in the inclined plate or hot plate tests. Quantitative histopathological evaluation demonstrated markedly enlarged cystic cavities in HET female mice when compared with WT counterparts. These integrated results indicate that HAP1 deficiency aggravates SCI progression by amplifying both structural damage (cystic cavitation) and functional deficits (hindlimb recovery delay).

In the nervous system, BDNF secretion and transmission play pivotal roles in cell survival, neuronal differentiation, and synaptic plasticity [42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47]. Following synthesis, BDNF undergoes axonal transport and is released in an activity-dependent manner [42, 48, 49]. Notably, HAP1 exhibits widespread distribution throughout the neural system, including brain, spinal cord, and dorsal root ganglia [37, 50, 51], where it interacts with multiple membrane proteins regulating vesicular trafficking, particularly those involved in BDNF and pro-BDNF transmission [15, 25, 42, 52]. Building upon this evidence, BDNF expression was quantified via qPCR and ELISA, revealing a marked reduction in both mRNA and protein levels of BDNF in HET mice when compared with WT controls post-SCI. Critically, exogenous BDNF administration significantly enhanced functional recovery, thereby substantiating the hypothesis that HAP1 deficiency impairs behavioral restoration through BDNF downregulation.

Mounting evidence suggests that HAP1 deficiency exacerbates functional impairment after spinal cord injury; however, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying its role in SCI pathophysiology remain elusive. To address this knowledge gap, RNA-seq technology was utilized to comprehensively characterize functional alterations, pathway dysregulation, and transcriptomic changes associated with varying HAP1 expression levels post-SCI. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed significant perturbations across multiple biological domains, including fundamental cellular processes, disease-related pathways, and information transduction systems.

This study elucidated the neuroprotective role of HAP1 in SCI pathogenesis and its underlying mechanisms. Abundant HAP1 expression was identified in spinal cord tissues and demonstrated that a genetic deficiency of HAP1 markedly exacerbates both structural damage (cystic cavitation) and functional impairment (hindlimb motor deficits) post-SCI. Mechanistically, these detrimental effects were primarily mediated through significant downregulation of BDNF levels, as evidenced by rescue experiments showing improved behavioral recovery upon exogenous BDNF administration. Transcriptomic profiling revealed gene expression differences in HAP1-deficient conditions, implicating its multifaceted regulatory roles in SCI-related pathological cascades. Collectively, such findings establish HAP1 as a crucial molecule in SCI progression, with the HAP1/BDNF axis representing a promising therapeutic target that merits further investigation.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

JP and RY designed the research study. XX and YW performed the research. HZ provided help and advice on the ELISA experiments and contributed to the conception of this work. FL analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All procedures were approved by Nantong University’s Animal Care Committee (No. S20200323-212) and followed strict ARRIVE guidelines for housing and experimentation.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82001168).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.