1 Key Laboratory of Human Microenvironment and Precision Medicine of Anhui Higher Education Institutes, School of Life Sciences, Anhui University, 230601 Hefei, Anhui, China

2 Institute of Anatomy, Department of Biomedicine, University of Basel, 4056 Basel, Switzerland

Abstract

Spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder marked by progressive loss of cerebellar function. Over 40 genetically defined SCA subtypes have been identified, arising from mechanisms such as cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeat expansions, point mutations, and gene deletions. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 (SCA14) stems from mutations to the protein kinase C gamma (PRKCG) gene, which codes for protein kinase C gamma (PKCγ), a signaling protein predominantly expressed in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Although the genetic basis of SCA14 is well established, the mechanisms driving Purkinje cell dysfunction remain poorly understood. Notably, transgenic mice expressing the common PKCγ-Gly118Asp (G118D) mutation, located in the protein’s regulatory domain, do not exhibit an overt disease phenotype, raising questions about potential compensatory changes at the molecular level.

We examined the expression of regulator of G protein signaling 8 (Rgs8), a molecule implicated in SCA-related pathways. Organotypic slice cultures and primary cerebellar cell cultures were generated in vitro to assess Purkinje cells from the non-manifesting PKCγ-G118D transgenic mouse line.

A significant increase in Rgs8 expression was observed in both slice cultures and primary cerebellar cell cultures derived from the non-manifesting SCA14 mouse line.

Elevated Rgs8 expression in Purkinje cells from symptom-free PKCγ-G118D mice suggests molecular adaptations that may underlie the non-manifesting phenotype, offering insight into the subclinical SCA14 pathophysiology.

Keywords

- spinocerebellar ataxia

- PKCγ

- Rgs8

- regulator of G protein signaling 8

- protein kinase C gamma

- Purkinje neurons

Spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) represent a diverse group of autosomal dominantly inherited disorders marked by progressive cerebellar degeneration and dysfunction [1, 2]. There are more than 40 genetically distinct subtypes within SCAs, classified by their disease loci or causative genes identified over time. Genetically, SCAs can be divided into two primary groups: Group I encompasses repeat expansion SCAs, such as spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) and spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2), induced by dynamic genetic alterations like polyglutamine repeat augmentations; whereas Group II encompasses conventional mutation related SCAs (non-repeat expansion SCAs), such as spinocerebellar ataxia type 5 (SCA5) and spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 (SCA14), which stem from nonsense, missense mutations, deletions, or insertions [1]. The primary anatomical region exhibiting pathological alterations in SCAs is the nervous system, and the cerebellum represents the portion of the brain most severely impacted. Notably, dysfunction and degeneration of Purkinje cells, which result in cerebellar atrophy, are frequently observed in most SCA subtypes. Furthermore, abnormalities in Purkinje cell development at early stages have been linked to the severity of disease progression [3, 4]. Increased serum levels of Neurofilament light polypeptide have been observed in SCA patients, indicating its potential as a progression marker [5, 6]. However, Neurofilament light polypeptide lacks specificity for cerebellar damage, necessitating the identification of SCA-specific biomarkers. Regulator of G protein signaling 8 (Rgs8), a protein highly expressed in Purkinje cells, has emerged as a crucial signaling component in various SCA subtypes [7]. Rgs8 expression alterations, encompassing both increases and decreases, have been documented in multiple mouse models of SCAs and are linked to the pathology of several SCA forms. For example, Rgs8 downregulation is observed in SCA1, SCA2, spinocerebellar ataxia type 7 (SCA7), and spinocerebellar ataxia type 17 (SCA17), whereas its upregulation modulates mGluR1-protein kinase C (PKC) signaling in Purkinje cells within a mouse model of SCA14 harboring a constitutive PKC mutant [7, 8, 9, 10]. These findings suggest that changes in Rgs8 expression may serve as a sensitive indicator of intracellular signaling disturbances in SCAs.

SCA14, an inherited disorder, is a subtype of SCAs characterized by ataxia, oculomotor disturbances, and dysarthria. The causative gene for SCA14 has been identified as protein kinase C gamma (PRKCG), which encodes protein kinase C gamma (PKC

The ethical principles set forth in the EU Directive 2010/63/EU concerning the utilization and welfare of laboratory animals were strictly adhered to throughout the execution of our experiments. Prior approval was granted by both the veterinary office of the canton of Basel and the relevant Swiss authorities. For this study, we utilized SCA14 conditional transgenic mice with an FVB background, which has been previously described in detail [12]. The transgenic experiments were performed in mice with an FVB genetic background at the Transgenic Animal Facility of the Biozentrum, University of Basel, utilizing the pronuclear microinjection technique. To identify founder animals, genotyping was carried out using genomic DNA extracted from biopsy samples via PCR analysis. In the initial genotyping step, forward primer 1 (5′-GACCCCTCCAGACCGCCTAGTCCTG-3′) and reverse primer 1 (5′-GCCTATGGAAAAACGCCAGCAACGC-3′) were employed, while in the second round, a 585 bp fragment was detected using forward primer 2 (5′-GAGACTTGATGTACCACATTCAACAG-3′) and reverse primer 2 (5′-GGCGGGGTCTGAAAGGAGGCGGG-3′). Subsequently, the presence of the transgenic human PRKCG gene was confirmed through DNA sequencing, with the DNA fragment for sequencing amplified by PCR using genomic DNA samples and a different primer pair: forward primer (5′-GTCGAGTTTACTCCCTATCAGTGATAG-3′) and reverse primer (5′-TAGTCCTGTCGGGTTTCGCCACCTC-3′). After confirming the transgenic founder animals, they were bred with FVB-Tg (Pcp2-tTA) 3 Horr/J transgenic mice obtained from the Jackson Laboratory in Sacramento, CA, USA, to generate Pcp2-tTA/TRE-PKC

Organotypic slice cultures were generated according to a previously established protocol detailed by Kapfhammer and Gugger (2012) [13]. On postnatal day 8, mouse pups were euthanized via decapitation, and their brains were aseptically extracted and dissected. In a chilled minimal essential medium (MEM) (Gibco, cat. no. 11090-081, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Reinach, Switzerland) supplemented with 1% glutamax (Gibco, cat. no. 35050-061, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific), the cerebellum was isolated, and sagittal slices of 350 micrometers in thickness were precisely cut using a McIlwain tissue chopper (model McIlwain TC752, Mickle Laboratory Engineering Co. Ltd., Guildford, Surrey, UK; distributed by Thermo Fisher Scientific) under sterile conditions. The cerebellar slices were then meticulously separated and placed onto a permeable membrane (Millicell-CM, cat. no. PICM03050, Merck Millipore, Merck AG, Buchs, Switzerland). These slices were incubated in either incubation medium, composed of 50% MEM (Gibco, cat. no. 11090-081), 25% Basal Medium Eagle (BME; Gibco, cat. no. 21010-046), 25% horse serum (HS; Gibco, cat. no. 26050-088), 1% glutamax (Gibco, cat. no. 35050-061), and 0.65% glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. G7021, Merck AG), or in Neurobasal medium, consisting of 97% Neurobasal medium (Gibco, cat. no. 21103-049), 2% B27 (Gibco, cat. no. 17504-044), and 1% glutamax (Gibco, cat. no. 35050-061). Both incubations were carried out under 5% CO2 at 37 °C, with the medium being renewed every 2 to 3 days to ensure optimal culture conditions.

Primary Purkinje cell cultures were generated from neonatal transgenic mice based on established methods [12]. At postnatal day 0, cerebella were harvested from the mice and processed for dissociation. Subsequently, cells were seeded onto Poly-D-lysine-treated glass chambers to promote adhesion. Cultures were maintained in medium containing 90% DFM (DMEM/F-12, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12, cat. no. 21331020, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with essential supplements: 1% N2, 1% glutamax, and 10% fetal bovine serum (cat. no. 10270106, Life Technologies, Zug, Switzerland). Within the initial 2–4 hours after plating, each well received 500 µL of supplemental DFM containing 1% N2 and 1% glutamax. To preserve favorable growth conditions, 50% medium was refreshed every 4 days. Following a 14-day culture period, cells were fixed for downstream assessment.

For immunocytochemical analysis, primary cerebellar Purkinje cells derived from PKC

Purified protein extracts were obtained by homogenizing cerebellar slices in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. 11836170001, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. 4906845001, PhosSTOP, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Protein lysates were then electrophoretically separated via SDS-PAGE and trans-blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes for immunodetection. Preceding primary antibody exposure, membrane blocking was conducted with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (1 hr) to reduce non-specific interactions. Membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies: sheep anti-Rgs8 (cat. no. AF6880, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; 1:1000) and rabbit anti-α-Tubulin (cat. no. 11224-1-AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA; 1:1000). After TBS-T washes to clear unbound antibodies, detection was performed using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies: anti-sheep HRP conjugate antibody (cat. no. HAF016, R&D Systems, 1:1000), anti-mouse HRP conjugate antibody (cat. no. W402B, Promega, Madison, WI, USA; 1:10,000), and anti-rabbit HRP conjugate antibody (cat. no. W401B, Promega, 1:10,000). Alternatively, membranes were incubated with IRDye Secondary Antibodies, specifically IRDye 680LT-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. 926-68021, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA; 1:10,000) and IRDye 800CW-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. 926-32210, LI-COR Biosciences, 1:10,000), for quantitative analysis. Protein visualization was achieved using the ECL method provided by Pierce, a brand of Thermo Fisher Scientific. For quantitative assessment of protein expression, Band quantification was performed utilizing C-Digit Blot software (Image Studio version 5.2.5, LI-COR Biosciences, Bad Homburg, Germany) for precise densitometric analysis.

To measure the dendritic area of Purkinje cells, we employed a validated image analysis program as previously described [7]. This protocol designated the average dendritic area of control Purkinje cells as baseline (normalized to 1). For controls, we selected green fluorescent protein (GFP)-negative Purkinje cells adjacent to GFP-positive counterparts, detected through specific protein markers. This strategy guaranteed comparable growth environments for both cell types, enabling direct comparisons. Using ImageJ software (Version 1.53t, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), we scrupulously outlined both control and experimental Purkinje cells to calculate total soma and dendritic areas. These measurements underwent additional analysis in GraphPad Prism (Version 9.0.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). ImageJ computed mean somatic fluorescence intensity, while raw images were applied to intensity analysis. Images underwent linear brightness/contrast adjustments. Sholl analysis centered on mean/max intersection counts assessed dendritic complexity and measured soma areas in primary cultures. Statistical variations were examined via unpaired t-tests (95% confidence interval (CI)), with significance ascertained at p

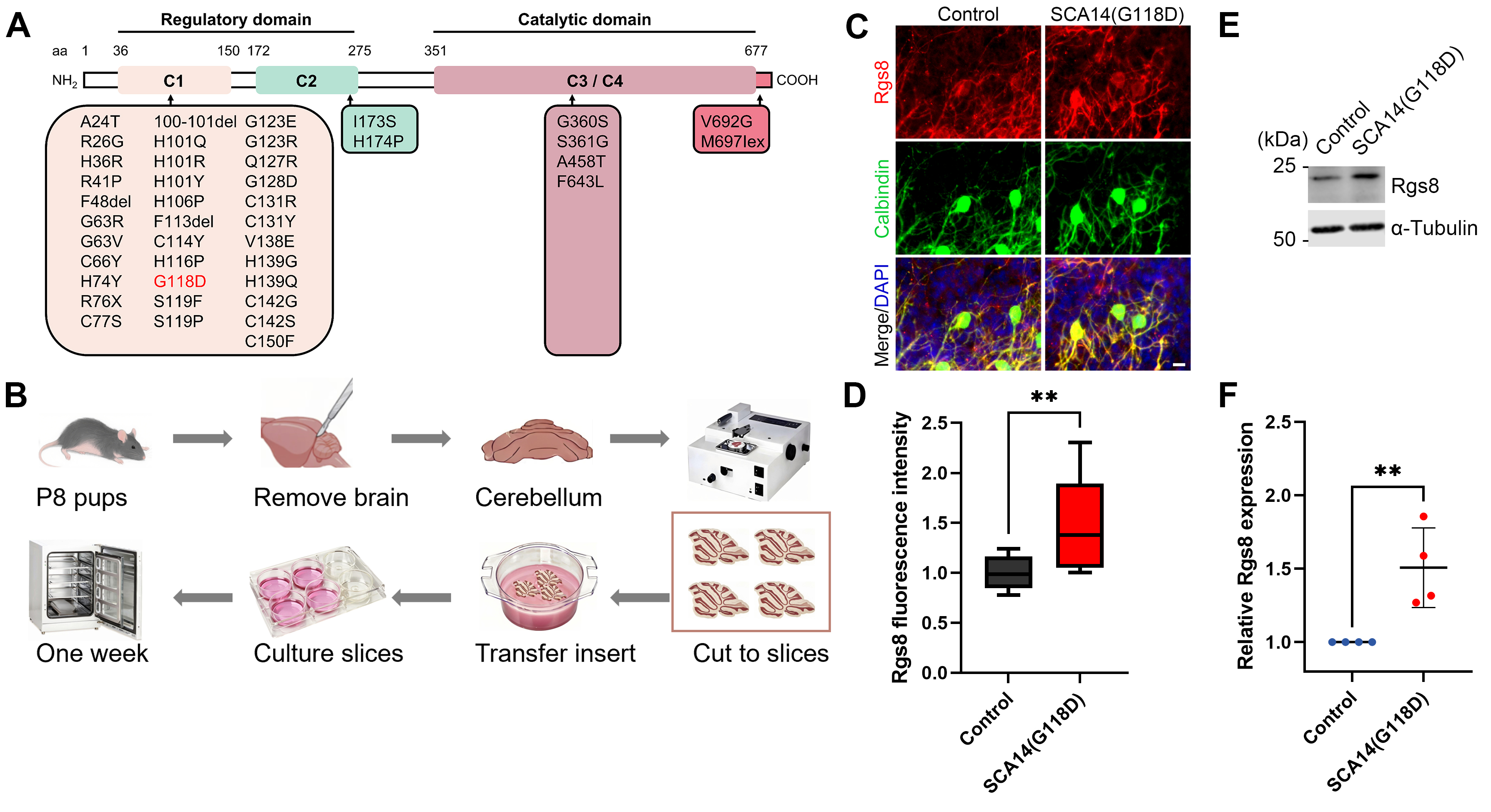

The PRKCG gene harbors more than 40 mutations, one of which is the G118D mutation, identified in patients with SCA14 (Fig. 1A). This particular mutation is located in the regulatory domain of the PKC

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Increased Rgs8 expression in cerebellar slice cultures of SCA14(G118D) mouse line. (A) Mutation overview in protein kinase C gamma (PKC

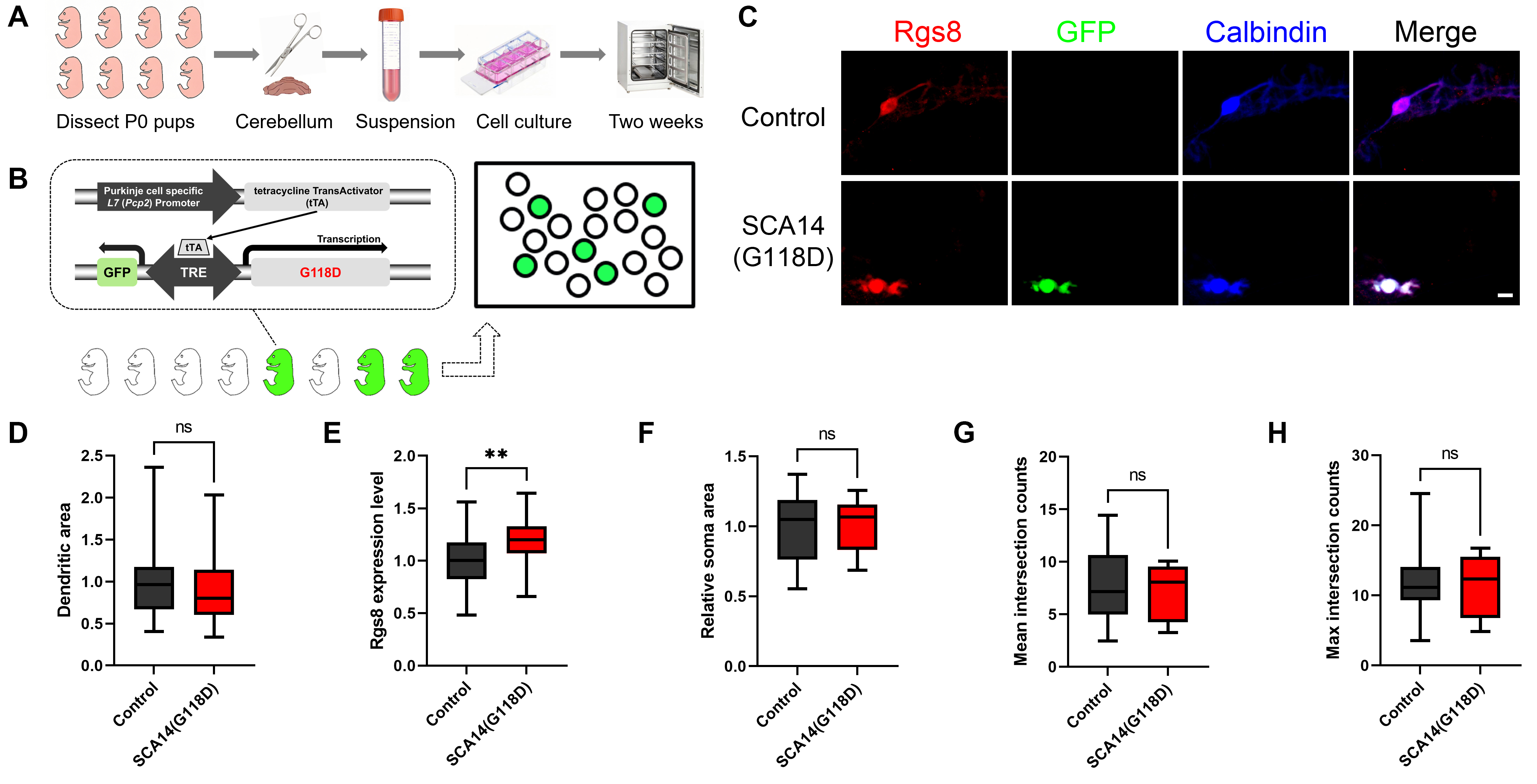

To further assess potential Rgs8 expression changes, we established primary cerebellar cell culture methods, which allowed systematic characterization of individual Purkinje cell phenotypes. Cerebellar tissue from P0 pups was dissociated into single-cell suspensions, cultured for two weeks, and then fixed for immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 2A). The SCA14(G118D) transgenic mouse model attains cell-specific expression of the transgene along with GFP via the Tet-Off system driven by the Purkinje Cell Protein 2 / L7 (PCP2/L7) Promote. This approach allowed us to isolate the effects of the mutation, excluding other potential factors involved in SCA pathogenesis. Within the mixed dissociated cultures that were obtained from both G118D-transgenic and control mouse pups, we identified transgenic Purkinje cells through their endogenous GFP expression (Fig. 2B). A quantitation of immunoreactivity was then conducted between GFP-positive Purkinje cells from G118D-transgenic mice and GFP-negative Purkinje cells from control mice within the same culture well. Our findings revealed that, although there were no significant morphological differences between Purkinje cells from G118D-transgenic mice and control mice (Fig. 2C), there was a notable increase in Rgs8 immunoreactivity. Specifically, Rgs8 expression was 1.2

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Increased Rgs8 expression in Purkinje cells of SCA14(G118D) transgenic mice suggests early disruption of intracellular signaling pathway. (A) The illustrated workflow begins with the dissection of postnatal day 0 (P0) mouse pups. Cerebellar tissue is isolated and dissociated into a single-cell suspension, which is transferred into a conical tube. The suspension is then cultured in a dish containing the medium. After a two-week incubation period, the cultured cells are fixed and stained. (B) A depiction of the SCA14(G118D) mouse line is shown, illustrating Purkinje cells that either express the G118D mutant (and are thus GFP-positive) or do not express it (and are GFP-negative). This expression is facilitated by the L7 promoter-based Tet-Off system. Cerebellar dissociated cultures were employed, in which Purkinje cells from both transgenic mice and their control littermates were cultured under identical conditions. Within the culture dish, GFP-positive cells (appearing green) were observed, indicating the expression of the PKC

In our previous studies, we documented a non-manifesting SCA14 mouse line that did not exhibit overt ataxia despite the presence of the PKC

Recently, Rgs8 has emerged as a pivotal molecule altered in various SCA mouse models [4, 7, 15], prompting us to investigate its role in our non-manifesting SCA14 mouse line. Utilizing both organotypic slice cultures and primary cerebellar dissociated cultures, we were able to examine Rgs8 expression in both control and SCA14(G118D) mouse lines. Our findings revealed a significant upregulation of Rgs8 protein levels in the SCA14(G118D) mouse line, indicating a disruption of intracellular signaling within the cerebellum of these mice, even in the absence of overt ataxia. To further delve into the specific changes in Rgs8 expression at the Purkinje cell level, we use this conditional transgenic mouse line, which allowed for the specific expression of SCA14-associated G118D mutations in Purkinje cells using a Tet-Off system based on the PCP2/L7 promoter driving tetracycline TransActivator (tTA). In order to avoid any confounding factors, we used dissociated cultures with cells mixed from wild type control mice and mice from the non-manifesting SCA14 mouse line. Purkinje cells derived from this mouse line could be identified by endogenous GFP-expression. This setup enabled us to eliminate any confounding influences from other cell types, providing a clearer condition of Rgs8 expression changes specifically within Purkinje cells. Consistent with our observations within organotypic slice culture systems, Purkinje neurons derived from G118D-transgenic mice did not exhibit significant morphological differences in comparison with GFP-non-expressing Purkinje cells sourced from control mice. However, immunohistochemical analysis revealed an elevated expression level of Rgs8 within Purkinje neurons derived from G118D-transgenic mice, confirming the disruption of signaling pathways in these Purkinje cells.

Our findings highlight the sensitivity of Rgs8 to intracellular signaling changes in Purkinje cells of the non-manifesting SCA14 mouse line. Despite the lack of overt ataxia and significant Purkinje cell abnormalities, the upregulation of Rgs8 suggests a disruption in signaling pathways that may be linked to the underlying mechanism of the muted effect of the PKC

In our study, we observed a significant upregulation of Rgs8 expression levels in the Purkinje cells from a non-manifesting SCA14 murine line carrying the PKC

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors.

QWW and JPK conceived and designed the study. QWW performed the experiments and analyzed the data. QWW and JPK wrote the manuscript. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The animal study protocol was approved by the Veterinary Office of the Canton of Basel (date of approval on 16 April 2018) and was registered with the relevant Swiss authorities in accordance with EU Directive 2010/63/EU (registration number 1708-28053). The ethical principles set forth in the EU Directive 2010/63/EU concerning the utilization and welfare of laboratory animals were strictly adhered to throughout the execution of our experiments.

The technical assistance provided by Markus Saxer and Aleksandar Kovacevic is greatly appreciated.

This research was funded by the Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation, grant number 2408085QH277, the Natural Science Research Project of Anhui Educational Committee, grant number 2024AH050075, the Swiss National Science Foundation, grant number 310030_189083, and was supported by the State Scholarship Fund of China Scholarship Council, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.