1. Introduction

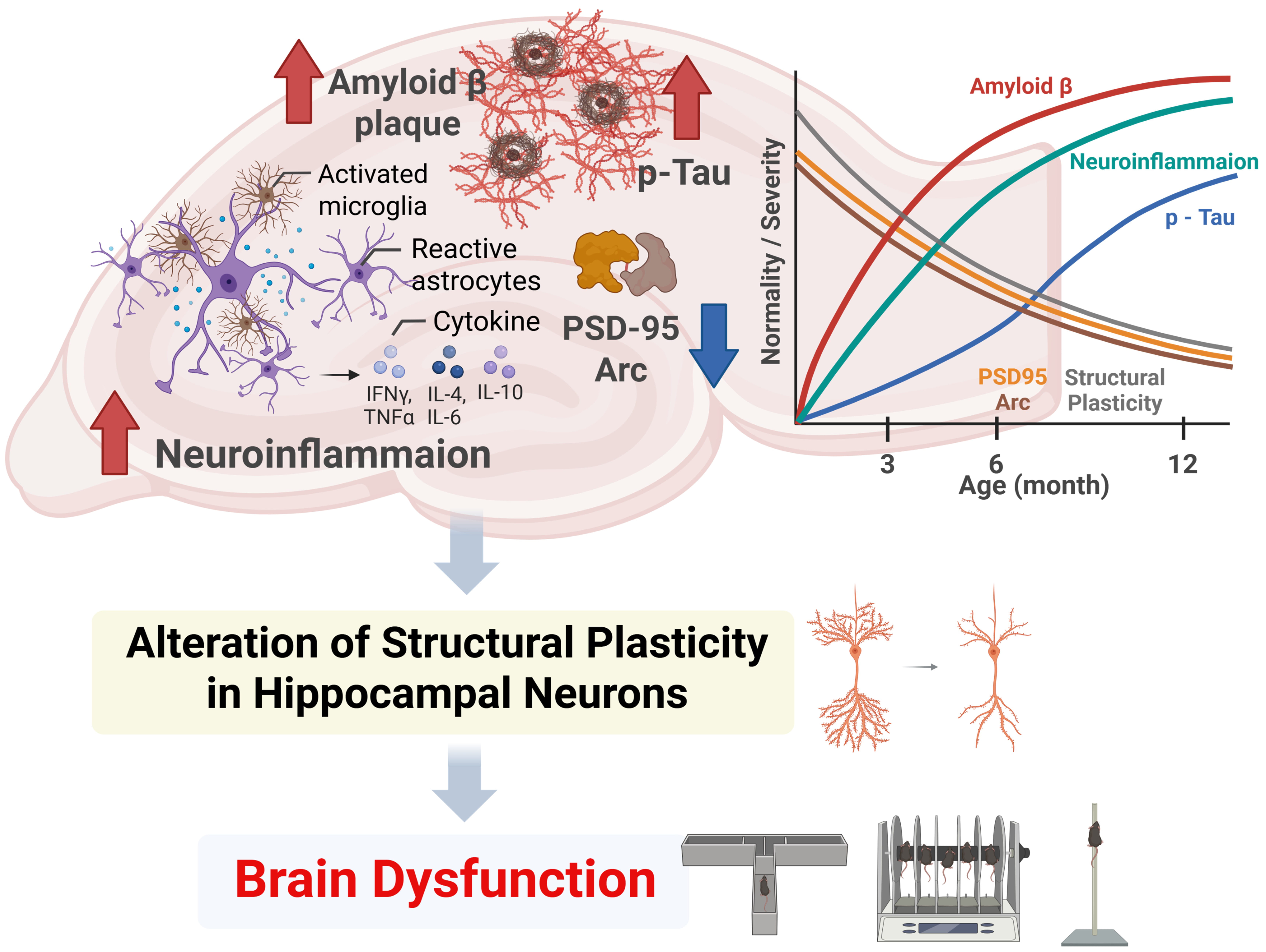

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) represents the predominant form of dementia and is increasingly recognized as one of the costliest, deadliest, and most burdensome diseases of the current century [1]. AD is a progressive and chronic neurodegenerative disorder clinically characterized by cognitive dysfunction, memory impairment, and behavioral changes, including motor symptoms such as gait disturbances and impaired balance [2, 3]. These complex clinical manifestations are attributed to the multifaceted pathology of AD, characterized primarily by the excessive accumulation of amyloid (A) peptides, the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) composed of phosphorylated tau (p-Tau), and persistent neuroinflammation across various brain regions [4].

Neuroplasticity encompasses a series of stimuli-induced biochemical alterations at both pre- and postsynaptic sites [5, 6]. Further, neuroplasticity is categorized into structural plasticity and functional plasticity [7]. Structural plasticity is crucial in forming and developing neuronal dendrites and spines. Cytoskeleton-regulating proteins modulate structural plasticity by regulating actin cytoskeletal dynamics, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor, glutamate receptors, and postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95) [7]. Functional plasticity, or synaptic plasticity, modulates synaptic transmission by altering synaptic formation or transmission efficacy [5]. Functional plasticity is demonstrated through long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), contingent upon synaptic activity and efficacy [5]. The two forms of plasticity are closely interconnected, as demonstrated by synaptic plasticity leading to morphological changes in dendritic spines; specifically, LTP promotes spine head growth, whereas LTD results in spine retraction [8]. Thus, structural and functional plasticity interactions are fundamental to maintaining normal brain microarchitecture and physiology.

In AD patients, the homeostasis of neuroplasticity is disrupted, representing a significant pathological feature of disease progression [9]. This impairment in neuroplasticity progressively impacts various aspects, including dendritic ramifications, axonal sprouting, neurogenesis, synaptic remodeling, synaptic efficacy, and synaptogenesis [10]. A and p-Tau, the main pathogenic factors of AD, inhibit excitatory synapses and diminish neuronal activity, thereby disrupting synaptic networks, ultimately resulting in spine or synaptic loss and neuronal death [11, 12]. Furthermore, neuroinflammation significantly impacts neuroplasticity, contributing to AD pathology [13]. Pathological lesions are particularly pronounced in susceptible brain regions, notably the hippocampus, and are among the first to exhibit changes in AD [14, 15]. Nevertheless, the mechanisms through which their relationship with neuroplasticity is governed remain inadequately understood.

Hippocampal functional plasticity has been extensively studied in various neurological disorders, including AD, highlighting its significant association with learning and memory functions [16]. However, a deficiency exists in our comprehension of hippocampal structural plasticity during AD progression. Further, the molecular mechanisms underlying alterations in structural plasticity remain largely unexplored. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the temporal changes in neuroarchitecture within the hippocampal subregions and the associated molecular alterations linked to brain dysfunction in AD using the 5FAD mouse model, which is commonly utilized in AD research due to its rapid and aggressive A deposition, gliosis, and progressive neuronal loss [17].

2. Methods

2.1 Animals

Transgenic 5FAD mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (strain: 034848JAX; Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and were maintained through regular breeding with C57BL/6 mice (Damool Science, Daejeon, Korea). Female C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) and 5FAD mice at 3, 6, or 12 months of age were included in this study. Genotyping confirmed the presence of five familial AD mutations: App KM670/671NL (Swedish), App I716V (Florida), App V717I (London), Psen1 M146L (A C), and Psen1 L286V. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (66794-013-10, Piramal Critical Care Inc, Bethlehem, PA, USA; 3% for induction, 1.5–2% for maintenance) and euthanized by cervical dislocation under deep anesthesia, in accordance with institutional guidelines. Experimental timelines are presented in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic of the experimental design and behavioral changes in 5FAD mice. (A) Pole and T-maze tests were performed on 5FAD and WT mice aged 3, 6, and 12 months. Subsequently, the animals were sacrificed to collect samples for Golgi staining, Western blot, and IHC. (B) Images representative of the pole tests are provided (left panel). The bar graphs illustrate time to turn and time to descend in the pole test in 5FAD mice compared with the WT (right panels). (C) Representative illustrations of the T-maze test are provided (left panel). The bar graphs illustrate the spontaneous alternation ratio observed in the T-maze test (right panel). Fig. 1A and Fig. 1C were generated using BioRender.com (https://www.biorender.com/). The data represent the combined mean standard error (SE) from two distinct experiments (n = 10/group). * p 0.05, ** p 0.01, *** p 0.001, **** p 0.0001. IHC, immunohistochemistry; WT, wild-type; 5FAD, five familial Alzheimer’s disease.

2.2 Pole Test

The pole test was performed based on a previously established method, incorporating minor modifications [18]. In brief, a metal pole (0.5 cm diameter, 50 cm height) was covered with gauze to prevent slippage. Each mouse was placed facing upward at the top of the pole, and the time taken to descend to the base was measured. Mice completed three trials, separated by 20-minute intervals, and the average times (s) were assessed.

2.3 Spontaneous Alternation T-maze Test

The spontaneous alternation T-maze test was carried out using a previously reported method with minor changes [19]. A T-maze was constructed from black acrylic plastic, featured arms measuring 30 10 20 cm. Each mouse was placed at the start arm for 10 min, after which the central divider was removed to begin the trial. The animal was allowed to move freely toward either the left or right goal arm. Once the tail fully entered the chosen arm, it was closed off with a divider. After 30 s, the divider was lifted, and the mouse was returned to the start arm for another trial. This procedure was performed twice daily for three days, with 3-hour intervals between sessions. Scoring was performed as follows: a score of 0 was assigned if the mouse chose the same arm consecutively, and 1 if it alternated between arms within the trial.

2.4 Golgi Staining

To examine dendritic architecture, including spine morphology and density, neurons from the cornu ammonis (CA) 1 subregion and dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus were subjected to Golgi staining. Following previously described procedures [20], we used the FD Rapid Golgistain™ kit (#PK401, FD Neurotechnologies, Columbia, MD, USA), following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Brain hemispheres (n = 5/group) were rinsed with 0.1 M phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 1X; diluted from 10X stock, 502B828, Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd., Gyeonggi-do, Korea) and immersed in Golgi–Cox solution for 2 weeks. Subsequently, the samples were placed in a sucrose-based solution at room temperature (RT; 22 2 °C) for an additional 3 to 7 days. Coronal brain sections, cut at 200 µm thickness, were mounted on gelatin-coated slides with a small amount of sucrose solution. After air-drying in the dark for 3 days, the slides were processed according to the staining kit’s standard protocol.

2.5 Sholl Analysis

Quantification of dendritic complexity, length, and branching was performed according to established methods [20]. Neuronal structures were imaged at 200 magnification using a Leica DM750 microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and neuronal traces were obtained with Leica Application Suite (v4.12) alongside Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). Sholl analysis was carried out with ImageJ software (version 1.53f51, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) using a concentric circle overlay technique [21]. For each animal (n = 5/group), 10 neurons were selected per hippocampal subregion following defined criteria [22]: The cell body was situated in the designated subregion, exhibiting thorough and effective branch staining along its entirety while remaining isolated from adjacent cells. Concentric circles were drawn from the center of the soma to the most distal dendritic end, spaced 10 µm apart. The number of dendritic intersections at each radius was recorded to assess arborization. Ten neurons per subregion were analyzed per mouse, and the mean value from each mouse was treated as n = 1. Group results were calculated as the mean standard error (SE), and sample details are provided in the respective figure legends.

2.6 Analysis of Dendritic Spine Density and Morphology

The density and morphology of dendritic spines were measured according to an established methodology [23]. For this analysis, we enumerated all identifiable dendritic spines along a 30 µm segment of the distal dendrite of each neuron using a magnification of 1000. Only segments that were intact, clearly stained, and unbranched were selected. Spines were categorized into three morphological types: thin spine, featuring a small head and elongated neck; mushroom spine, distinguished by a large head and defined neck; stubby spine, characterized by a compact appearance and absence of a discernible neck. A total of 10 dendritic segments were analyzed per animal (n = 5/group), and spine density was calculated as the number of spines per 10 µm of dendritic length.

2.7 Western Blot

Western blotting was conducted in accordance with established protocols [24]. Each sample was sonicated in buffer H for 10 s, which contained 50 mM -glycerophosphate (#G6376, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 1.5 mM ethylene glycol tetra-acetic acid (#E3889, Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM dithiothreitol (#09779, Sigma-Aldrich), 10 µg/mL aprotinin (#A1153, Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (#P7626, Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1 mM Na3VO4 (#S6508, Sigma-Aldrich), 10 µg/mL leupeptin (#L2884, Sigma-Aldrich), and 2 µg/mL pepstatin (#EI10, Sigma-Aldrich) at pH 7.4. Subsequently, 6 sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer was added, and samples were boiled at 100 °C for 10 min. Protein samples were separated on 10–15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (#1658033, Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA), followed by transfer onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (#10600023, Amersham Hybond-P; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). To block nonspecific binding, membranes were incubated at RT for 1 h in PBS (1X; diluted from 10X stock, 502B828, Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.) with 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (#P2287, Sigma-Aldrich; PBS-T; pH 7.4) containing 1% (v/v) normal goat serum (NGS; #S-1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and 0.5% (v/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA; #A9647, Sigma-Aldrich). Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution and then left at RT for 1 h. Primary antibodies included mouse anti-A (1-16) (clone 6E10, 1:1000; #803001, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), rabbit anti-p-Tau (Thr181) (1:1000; #12885S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:1000; #3670, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba-1, 1:1000; #016-20001, Fujifilm Wako, Osaka, Japan), rabbit anti-PSD-95 (1:1000; #2507, Cell Signaling Technology), and rabbit anti-activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein (Arc; 1:1000; #ab183183, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Subsequent to the primary antibody incubation, membranes were incubated for 2 h with either a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5000; #31460, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) or mouse secondary antibody (1:5000; #31181, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Signals were visualized using the EZ-Western Lumi Femto kit (#DG-WF200, DoGenBio, Seoul, South Korea). Following stripping, membranes were re-probed with mouse anti--actin antibody (1:5000; #A5441, Sigma-Aldrich) at RT for 2 h. The optical density (OD) of each band was evaluated utilizing an iBright CL750 Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mean band intensity of the WT group was designated as ‘1’ for each blot, and relative expression levels were calculated as fold changes. Group means were calculated and reported as mean SE.

2.8 Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed in accordance with the protocol previously established [20]. Brain hemispheres were fixed and sectioned sagittally into 3 µm slices. The paraffin-embedded tissues were processed using the Vectastain® Elite ABC kit (Rabbit IgG, #PK-6101; Mouse IgG, #PK-6102, Vector Laboratories) in accordance with standard immunohistochemical procedures. To inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity, sections were incubated in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide (#4104-4400, Daejung Chemicals & Metals Co., Ltd., Siheung, South Korea) for 20 min. Subsequently, tissues were blocked with either 5% NGS or 5% normal horse serum (Vectastain® Elite ABC kit) in PBS-T at RT for 1 h to minimize non-specific binding. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-A (1-16) (clone 6E10, 1:2000; #803001, BioLegend), rabbit anti-p-Tau (Thr181) (1:100; #12885S, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-GFAP (1:4000; #3670, Cell Signaling Technology), and rabbit anti-Iba-1 (1:2000; #019-19741, Fujifilm Wako). Following three washes with PBS, the slides were incubated with the appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies and subsequently treated with ABC peroxidase in accordance with the kit protocol (Vectastain® Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories). Finally, peroxidase labeling was developed using the 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) Substrate kit (Vector Laboratories), followed by hematoxylin counterstaining.

2.9 Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

Cytokine levels, specifically tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF, #DY410), interferon-gamma (IFN, #DY485-05), interleukin (IL)-1 (#DY401), IL-6 (#DY406), and IL-10 (#DY417), were quantified in hippocampal lysates from 5FAD mice using commercial Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The hippocampal tissues were mechanically disrupted in lysis buffer, and the concentrations of total proteins were subsequently determined. Lysates were applied to ELISA plates, and cytokine concentrations were assessed by comparing sample absorbance to standard curves created with recombinant cytokines. Absorbance measurements were conducted using an Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.10 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad software (version 9.3.1, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). To evaluate group differences in behavioral performance, dendritic complexity, and spine density between WT and 5FAD mice, a two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc test was used. Additional pairwise comparisons were conducted using an unpaired Student’s t-test. A significance threshold of p 0.05 was considered for all analyses. All numerical values are presented as mean SE. The number of samples included in each experiment is indicated in the corresponding Results sections and figure legends.

3. Results

3.1 Progressive Motor Deficits Observed in 5FAD Mice

The 5FAD mouse model exhibits age-related deficits in motor function [25]; however, limited information exists regarding the temporal profile of motor dysfunction in these mice. Therefore, this study conducted a pole test to validate the fine motor dysfunctions in 5FAD mice (n = 10 mice/group; the time to turn down: Finteraction (2,54) = 1.946, p = 0.1527, the time to descend: Finteraction (2,54) = 8.825, p = 0.0005; Fig. 1B). Notably, no significant differences were observed at 3 months in the time it took the mice to turn down from the top of the pole (WT vs. 5FAD: p = 0.4608) or to descend to the base of the pole (WT vs. 5FAD: p = 0.7966). Comparatively, the 5FAD mice displayed a significantly prolonged time to turn (p = 0.0357) and descend (p = 0.0006) at 6 months compared to the WT mice. At 12 months, these impairments were significantly more pronounced, with 5FAD mice showing a significantly longer time to turn (p = 0.0004) and to descend (p 0.0001). Collectively, these findings indicate that motor dysfunction is evident in 5FAD mice and exacerbates with increased age.

3.2 Progressive Cognitive Impairments Observed in 5FAD Mice

Next, the T-maze test was conducted in 5FAD and WT mice at 3, 6, and 12 months of age to assess the working memory through spontaneous alternation behavior (n = 10/group; Finteraction (2,54) = 2.943, p = 0.0612; Fig. 1C). This assessment evaluates the innate exploratory behavior of rodents in novel environments, indicative of hippocampal-dependent cognitive function [26] (Fig. 1C, left scheme). No significant differences were noted in the spontaneous alternation ratio at 3 months between WT and 5FAD mice (p = 0.9955), indicating comparable cognitive performance during the early stage of AD pathology. However, by 6 months, the 5FAD mice exhibited a significant reduction in the spontaneous alternation ratio relative to WT mice (p = 0.0141), suggesting the emergence of hippocampus-dependent cognitive impairment is linked to AD pathology. Meanwhile, cognitive deficits in 5FAD mice were significantly more pronounced at 12 months—indicated by a further decrease in the spontaneous alternation ratio (p = 0.0042). Statistical analysis demonstrated an age-related cognitive decline in 5FAD mice, with significant differences observed at 6 months, which were exacerbated by 12 months (Fig. 1C, right bar graphs).

3.3 Increased Expression of A and p-Tau (Thr181) in the Hippocampi of 5FAD Mice

This study investigated the age-dependent changes in A and p-Tau (Thr181) expression in the hippocampi of 5FAD mice compared to WT controls using Western blot and IHC (n = 3 mice/group). Western blot analysis demonstrated a significant and progressive increase in A1-42 levels in 5FAD mice with age compared to WT controls (t(4) = 3.311, p = 0.0296 at 3 months; t(4) = 3.467, p = 0.0257 at 6 months; t(4) = 5.260, p = 0.0063 at 12 months) (Fig. 2A). Moreover, an age-dependent increase in p-Tau expression levels was observed, achieving statistical significance at 12 months (Fig. 2A). At 3 months, p-Tau levels did not significantly differ from WT controls (t(4) = 0.8643, p = 0.4362). At 6 months, p-Tau levels were elevated in 5FAD mice, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (t(4) = 2.166, p = 0.0963). At 12 months, hippocampal p-Tau levels in 5FAD mice significantly increased (t(4) = 3.854, p = 0.0182).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Expression levels of A1-42 and p-Tau (Thr181) in the hippocampus. (A) Representative Western blot images and bar graphs of the relative levels of A1-42 (~4 kDa) and p-Tau (Thr181) in the hippocampi of WT and 5FAD mice (n = 3 mice/group). The full-length blot images are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. (B) Representative immunohistochemical images and bar graphs of the relative immunoreactivities of A and p-Tau (Thr181) in the hippocampus of WT and 5FAD mice (n = 3 mice/group). High-magnification versions of the insets are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. The data represent the combined mean SE from two distinct experiments. * p 0.05, ** p 0.01, *** p 0.001. Scale bars represent 500 µm (low magnification) and 100 µm (inset) in panel B. A, amyloid ; OD, optical density; p-Tau, phosphorylated Tau.

Next, we performed IHC to characterize further the spatial distribution of A and p-Tau (Thr181) expression across hippocampal subregions. IHC analysis demonstrated a significantly progressive increase in A immunoreactivity with age in 5FAD mice (t(4) = 5.879, p = 0.0042 at 3 months; t(4) = 8.966, p = 0.0009 at 6 months; t(4) = 4.443, p = 0.0113 at 12 months) (Fig. 2B, left panels). At 3 months, A exhibited extensive staining in the stratum pyramidale of CA1 and the distal CA1 subregion adjacent to the subiculum, with slight staining observed in the molecular layer of the DG. Immunoreactivity was more pronounced at 6 months than at 3 months of age, with A also detected in the stratum oriens of CA1, stratum lucidum of CA3, and the subgranular zone as well as in the hilus of the DG. At 12 months, the staining pattern was significantly enhanced across the hippocampus of 5FAD mice.

IHC analysis of p-Tau demonstrated a delayed yet progressive accumulation in the hippocampi of 5FAD mice (Fig. 2B, right panels). However, the p-Tau levels in 5FAD mice did not significantly differ from those in WT controls at 3 months (t(4) = 1.483, p = 0.2122). Conversely, the difference in p-Tau expression reached statistical significance at 6 and 12 months (t(4) = 4.275, p = 0.0129 at 6 months; t(4) = 3.822, p = 0.0187 at 12 months). In the spatial pattern analysis, the immunoreactivity of p-Tau was faintly detected at 3 months; however, p-Tau was observed in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare of CA1, distal CA1 area, and hilus at 6 months of age. Moreover, enhanced immunoreactivity was noted across the hippocampus of 5FAD mice at 12 months of age. Collectively, these findings indicate a notable age-related escalation in early A and a subsequent increase in p-Tau expression within the hippocampi of 5FAD mice.

3.4 Elevated Neuroinflammatory Responses Observed in the Hippocampi of 5FAD Mice

We assessed the age-related alterations in astrocytic and microglial activation and cytokine levels in the hippocampi of 5FAD mice. GFAP and Iba-1, which serve as astrocytes and microglia markers, respectively, were assessed through Western immunoblotting and IHC (n = 3 mice/group). Western blot analysis revealed a progressive increase in GFAP and Iba-1 expression with age in 5FAD mice relative to WT controls (Fig. 3A). At 3 months, GFAP levels were marginally elevated in 5FAD mice, though this difference did not achieve statistical significance (t(4) = 1.986, p = 0.1180). Comparatively, GFAP expression was significantly elevated in 5FAD mice at 6 months and 12 months relative to WT controls (6 months: t(4) = 2.904, p = 0.0439; 12 months: t(4) = 4.792, p = 0.0087). Iba-1 levels were significantly elevated in 5FAD mice across all examined age groups: 3 months: (t(4) = 6.161, p = 0.0035), 6 months: (t(4) = 4.351, p = 0.0121), and 12 months: (t(4) = 5.931, p = 0.0041). In the IHC analysis, the left panels in Fig. 3B demonstrate no significant differences in the GFAP intensity in the hippocampus between groups at 3 months (t(4) = 1.054, p = 0.3515). However, a slight increase was observed in the 5FAD mice in the distal CA1 area. Elevated GFAP expression was significantly noted at 6 months (t(4) = 4.722, p = 0.0092) and 12 months (t(4) = 7.026, p = 0.0022). Notably, the intensities were markedly pronounced throughout the hippocampus of 5FAD at 6 and 12 months of age, particularly in the distal CA1, stratum oriens of CA1, and hilus. Iba-1 immunoreactivity in microglia (Fig. 3B, right panels) showed significant differences with age-dependent increases (t(4) = 3.320, p = 0.0294 at 3 months; t(4) = 4.742, p = 0.0090 at 6 months; t(4) = 4.031, p = 0.0157 at 12 months). Furthermore, the Iba-1 expression was primarily noted in the distal CA1 region at 3 months. In contrast, Iba-1 expression was present throughout the hippocampus at 6 and 12 months of age, especially in the distal CA1, stratum oriens of CA1, and molecular layer and hilus of the DG.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. GFAP and Iba-1 expression and cytokine levels in the hippocampus. (A) Representative Western blot images and bar graphs of the relative levels of GFAP and Iba-1 in the hippocampi of WT and 5FAD mice (n = 3 mice/group). The full-length blot images are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. (B) Representative immunohistochemical images and bar graphs of the relative immunoreactivities of GFAP and Iba-1 in the hippocampi of WT and 5FAD mice (n = 3 mice/group). High-magnification versions of the insets are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. (C) The bar graphs illustrate the cytokine levels (TNF, IFN, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-10) in the hippocampi of WT (n = 5) and 5FAD mice (n = 7) at 3, 6, and 12 months of age, as determined by ELISA. The data represent the combined mean SE from two distinct experiments. * p 0.05, ** p 0.01. Scale bars represent 500 µm (low magnification) and 100 µm (inset) in panel B. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; Iba-1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1; IFN, interferon-gamma; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Additionally, ELISA was employed to assess the inflammatory cytokine profile in the hippocampi of 5FAD mice for TNF, IFN, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-10 at 3, 6, and 12 months of age (n = 5 for WT and n = 7 for 5FAD; Fig. 3C). The inflammatory cytokines levels in the hippocampi of 5FAD mice showed an overall upward trend across ages. At 3 months, the IL-1 (t(10) = 3.042, p = 0.0124), IL-6 (t(10) = 2.632, p = 0.0251), and IL-10 (t(10) = 3.084, p = 0.0116) levels were significantly increased in 5FAD mice compared to WT controls (Fig. 3C, left bar graphs). At 6 months, the TNF (t(10) = 2.375, p = 0.0390), IFN (t(10) = 2.329, p = 0.0422), IL-1 (t(10) = 3.016, p = 0.0130), IL-6 (t(10) = 2.472, p = 0.0330), and IL-10 (t(10) = 2.946, p = 0.0146) levels were significantly elevated (Fig. 3C, middle bar graphs). At 12 months, the elevated level of IL-1 (t(10) = 2.567, p = 0.0280) was statistically significant (Fig. 3C, right bar graphs). Thus, these findings demonstrate a progressive and age-dependent increase in astrocytic and microglial activation, along with alterations in cytokine expression, in the hippocampi of 5FAD mice.

3.5 Dendritic Complexity Alterations in the Hippocampi of 5FAD Mice

We assessed hippocampal structural plasticity alterations in 5FAD mice by analyzing the dendritic complexity of neurons in the CA1 and DG subregions, focusing on the number of crossing dendrites, total dendritic length, and branch points per neuron. Fig. 4 illustrates the counting of dendritic intersections at various radial distances from the neuronal soma in the CA1 and DG subregions, conducted through Sholl analysis (n = 5 mice/group). In the CA1 basal subregion (Fig. 4A, upper panels), the 5FAD group showed fewer dendritic intersections compared to the WT group at a Sholl radius of 50 µm from the soma (Finteraction (20,1960) = 1.944, p = 0.0073; left-upper line graphs) at 3 months. Dendritic intersections exhibited a significant reduction at Sholl radii of 10–80 µm from the soma (Finteraction (20,1960) = 4.581, p 0.0001; middle-upper line graphs) at 6 months, with a more pronounced effect observed at 12 months, particularly at Sholl radii of 10–90 µm (Finteraction (20,1960) = 5.652, p 0.0001; right-upper line graphs). The total dendritic length in the CA1 basal subregion was reduced in 5FAD mice relative to WT controls across all ages; however, these differences did not reach statistical significance (Finteraction (2,24) = 0.2901, p = 0.7507; Fig. 4A, left-upper bar graphs). Analysis of neuronal branch points (Finteraction (2,24) = 3.405, p = 0.0499; Fig. 4A, right-upper bar graphs) revealed no significant differences at 3 months (p = 0.8217). However, a significant reduction was observed in 5FAD mice at 6 months compared to WT controls (p = 0.0126), with a more pronounced decrease at 12 months (p = 0.0005).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Dendritic complexity of hippocampal neurons in WT and 5FAD mice. Photographs illustrate representative neurons used for the Sholl analysis in the CA1 (A) and DG (B) subregions. Line graphs illustrate the mean number of intersections per 10 µm radial unit distance from the soma (0 µm) in the neuronal dendrites of CA1 basal (A, upper panels) and apical (A, lower panels), as well as in the DG (B) subregions. The bar graphs illustrate the total dendritic length (left panels) and the number of dendritic branch points (right panels) per neuron within each subregion. The data represent the combined mean SE from two distinct experiments involving 10 neurons per mouse and five mice per group. The actual images of the neurons are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5. The gray areas illustrate the SE of the means presented in the line graphs. * p 0.05, ** p 0.01, *** p 0.001, **** p 0.0001. Scale bars shown in the illustrated neuron images indicate 100 µm. CA1, cornu ammonis 1; DG, dentate gyrus.

No significant differences in dendritic intersections were noted in the CA1 apical subregion at 3 months between the 5FAD and WT groups (Finteraction (30,2940) = 1.199, p = 0.2103; Fig. 4A, left-lower line graphs). The dendritic intersections at 6 months showed a significant reduction at Sholl radii of 90–200 µm from the soma (Finteraction (30,2940) = 6.308, p 0.0001; Fig. 4A, middle-lower line graphs). This gap became more pronounced at 12 months, particularly at Sholl radii of 30, 50–70, and 90–190 µm (Finteraction (30,2940) = 10.070, p 0.0001; Fig. 4A, right-lower line graphs). The total dendritic length in the apical subregion (Finteraction (2,24) = 4.403, p = 0.0235; Fig. 4A, left-lower bar graphs) did not show a significant reduction in 5FAD mice compared to WT controls at 3 months (p = 0.2714). However, the total dendritic length in the apical subregion was statistically significant at 6 months (p = 0.0002) and 12 months (p 0.0001). Analysis of neuronal branch points (Finteraction (2,24) = 4.125, p = 0.0289; Fig. 4A, left-lower bar graphs) revealed no significant differences at 3 months. Meanwhile, a significant reduction was observed in 5FAD mice at 6 months compared to WT controls (p = 0.0001); this reduction persisted at 12 months (p = 0.0012).

No significant differences were observed in the dendritic intersections in the DG subregion between 5FAD and WT mice at 3 months (Finteraction (25,2450) = 0.8327, p = 0.7022; Fig. 4B, left line graphs). The dendritic intersections in 5FAD mice at 6 months were significantly diminished at Sholl radii of 80–140 µm from the soma (Finteraction (25,2450) = 5.886, p 0.0001; Fig. 4B, middle line graphs). This reduction became more pronounced at 12 months, particularly at Sholl radii of 100–160 µm (Finteraction (25,2450) = 4.635, p 0.0001; Fig. 4B, right line graphs). The total dendritic length (Finteraction (2,24) = 0.5119, p = 0.6057; Fig. 4B, left bar graphs) did not show a significant reduction in 5FAD mice, although a trend towards a decrease was observed across all ages in 5FAD group. Neuronal branch points in the DG (Finteraction (2,24) = 1.460, p = 0.2520; Fig. 4B, right bar graphs) exhibited a slight decrease at 3 months, with no significant difference observed. Alternatively, significant reductions were observed at 6 and 12 months in 5FAD mice compared to WT controls (p = 0.0049; p = 0.0103, respectively). Collectively, these findings suggest that dendritic complexity decreases with age in the CA1 and DG subregions of 5FAD mice.

3.6 Alteration in Dendritic Spine Density and Morphology in the Hippocampi of 5FAD Mice

Dendritic spines serve as the main components of synapses in hippocampal neurons and undergo rapid modifications in response to particular microenvironments, including neurodegenerative conditions [27]. This study investigated the temporal variations in dendritic spine density and morphology within the hippocampal CA1 and DG subregions of 5FAD and WT mice aged 3, 6, and 12 months (n = 5 mice/group; Fig. 5). Fig. 5A shows representative photomicrographs of neuronal dendrites across the various hippocampal subregions. No significant differences in spine density were observed in the CA1 basal subregion between 5FAD and WT mice at 3 months (Finteraction (2,24) = 3.295, p = 0.0544; Fig. 5B, left bar graphs). At 6 months, 5FAD mice exhibited a significant reduction in spine density (p 0.0001), which persisted at 12 months (p 0.0001). In the CA1 apical subregion of 3-month-old 5FAD mice (Finteraction (2,24) = 5.820, p = 0.0087; Fig. 5B, middle bar graphs), spine density exhibited a slight but significant decrease (p = 0.0450); a notable reduction was observed at 6 months (p = 0.0114), with an additional decrease at 12 months (p 0.0001). The spine density at 3 months in the DG subregion (Finteraction (2,24) = 9.058, p = 0.0012; Fig. 5B, right bar graphs) presented no significant difference between groups (p = 0.9738). At 6 months, 5FAD mice exhibited a significant reduction (p = 0.0018), which remained evident at 12 months (p 0.0001).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Dendritic spine density and morphology of hippocampal neurons in WT and 5FAD mice. (A) Representative images of dendritic spines in the CA1 basal, CA1 apical, and DG regions of 5FAD and WT mice at 3, 6, and 12 months of age. (B) The bar graphs illustrate spine density per 10 µm of dendrite length across hippocampal subregions in both WT and 5FAD mice. (C) The bar graphs exhibit proportional variations in spine morphology categories (thin, stubby, and mushroom) per 10 µm of dendrite. The data represent the combined mean SE from two distinct experiments involving 10 neurons per mouse and five mice per group. * p 0.05, ** p 0.01, *** p 0.001, **** p 0.0001. Scale bars in panel A represent 5 µm.

Additionally, differences in the proportion of dendritic spine morphology (% in 10 µm dendrite) were observed in the subregions of the hippocampi of 5FAD and WT mice (Fig. 5C). The proportion of thin spines (Fig. 5C, left panels) was significantly elevated in the CA1 basal subregion (Finteraction (2,24) = 1.933, p = 0.1667) of 6-month-old 5FAD mice (p = 0.0385), the CA1 apical subregion (Finteraction (2,24) = 4.453, p = 0.0227) of both 6- and 12-month-old 5FAD mice (p = 0.009 and p = 0.0309, respectively), and the DG subregion (Finteraction (2,24) = 0.5795, p = 0.5678) of 6- and 12-month-old 5FAD mice (p = 0.0070 and p = 0.0063, respectively). In contrast, the proportion of mushroom spines (Fig. 5C, right panels) was significantly decreased in the CA1 basal subregion (Finteraction (2,24) = 0.7758, p = 0.4715) of 6-month-old 5FAD mice (p = 0.0306), the CA1 apical subregion (Finteraction (2,24) = 6.364, p = 0.0061) of both 6- and 12-month-old 5FAD mice (p = 0.0017 and p 0.0001, respectively), and the DG subregions (Finteraction (2,24) = 1.003, p = 0.3818) of 6- and 12-month-old 5FAD mice (p = 0.0179 and p = 0.0026, respectively). No significant difference was exhibited between WT and 5FAD mice in the proportion of the stubby spines across all hippocampal subregions and age (Fig. 5C, middle panels). Collectively, these findings indicate that changes in spine density and morphology in the hippocampal neurons of 5FAD mice significantly worsen with advancing age.

3.7 Decreased Expression of PSD-95 and Arc in the Hippocampi of 5FAD Mice

The subsequent investigation focused on the molecular alterations associated with postsynaptic dysfunction in the hippocampi of 5FAD mice, specifically analyzing the protein expression levels of PSD-95 and Arc, which serve as markers of neuroplasticity [28, 29]. Western blot analysis was performed on hippocampal lysates from 3-, 6-, and 12-month-old WT and 5FAD mice (n = 3 mice/group; Fig. 6). At 3 months, no significant differences in PSD-95 or Arc expression were noted between WT and 5FAD mice (t(4) = 1.005, p = 0.3719; t(4) = 0.2712, p = 0.7997, respectively). Conversely, both PSD-95 and Arc expression were significantly reduced in 5FAD mice at 6 months relative to WT controls (PSD-95: t(4) = 3.169, p = 0.0339; Arc: t(4) = 3.746, p = 0.0200). While Arc levels remained consistently reduced at 12 months (t(4) = 2.875, p = 0.0452), PSD-95 expression showed a more pronounced decline (t(4) = 4.639, p = 0.0097). The results indicate an age-related decrease in the expression of PSD-95 and Arc in the hippocampi of 5FAD mice.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Expression levels of PSD-95 and Arc in the hippocampi of 5FAD and WT mice. Representative Western blot images and bar graphs of the relative levels of PSD-95 and Arc in the hippocampi of WT and 5FAD mice (n = 3 mice/group). The full-length blot images are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6. The data represent the combined mean SE from two distinct experiments. * p 0.05, ** p 0.01. Arc, activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein; PSD-95, postsynaptic density protein-95.

4. Discussion

This study examined the temporal changes in behavior and histopathological lesions in 5FAD mice to understand the potential interactions between these factors over time. The aging 5FAD mice demonstrated progressive deficits in motor and cognitive functions, along with aggregation of A and p-Tau, activation of astrocytes and microglia, production of proinflammatory cytokines, alterations in neuronal dendritic complexity and spine morphology, and reduced expression of postsynaptic proteins associated with neuroplasticity. These data indicate a progressive decline in both neuronal structure and function within the hippocampus of the AD mouse model, which may contribute to the manifestation of behavioral symptoms associated with AD. To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the temporal changes in the architecture of hippocampal neurons in 5FAD mice. Therefore, this study offers significant evidence concerning neuronal structural plasticity in AD progression. In contrast to other prevalent AD models such as 3Tg and APP/PS1, the 5FAD model exhibits an earlier and more severe onset of A pathology, due to the presence of five familial AD mutations [30, 31, 32]. The features offer a clear advantage in detecting early structural and functional changes in the hippocampus, thus reinforcing the temporal emphasis of the current study.

Cognitive impairment is recognized as the primary pathological symptom in AD patients [33]. Numerous studies have investigated learning and memory deficits in various AD mouse models, including APP/PS1, Tg2576, 3Tg, and 5FAD, employing assessments such as passive avoidance, fear conditioning, novel object recognition, and maze tests [34, 35, 36, 37]. Furthermore, there is a growing body of evidence regarding non-cognitive motor symptoms in AD, encompassing gait slowing, deficits in functional mobility, and impaired movement balance [38, 39]. This study examined cognitive and motor functions in 5FAD mice at various ages, utilizing the T-maze test to assess hippocampus-dependent working memory and the pole test for motor evaluation. Although no significant differences were noted in the earlier age group (3 months), a marked decline in working memory and fine motor coordination became evident at 6 months, with a more pronounced deterioration observed as the mice aged. Multiple prior studies have indicated that an impairment in synaptic plasticity, including diminished basal synaptic transmission and LTP, in the hippocampus of 5FAD mice is directly linked to deficits in learning, memory [40, 41, 42], and motor function [3]. The current findings indicate that hippocampus-related behavioral dysfunction in 5FAD mice deteriorates with age, mirroring the pathological progression of AD in humans.

The current study aimed to investigate the changes in the neuronal microarchitecture of hippocampal subregions, including CA1 and DG, in 5FAD mice across various ages. Among indexes for dendritic complexity, the significant decrease in crossing dendrite number was first observed in the CA1 basal dendrites of 3-month-old 5FAD mice, with subsequent reductions noted in all examined regions. Total dendritic length and the number of dendritic branches decreased across all subregions in 5FAD mice after 6 months of age, with significant reductions in dendritic length observed exclusively in the CA1 apical dendrites. As indicated by the synaptic drive of afferent inputs such as the perforant pathway [43], the accumulation of pathological proteins in the entorhinal cortex (EC) and subiculum throughout AD progression subsequently impacts the CA1 subregion, particularly the stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare (SRLM) [44, 45, 46]. The DG, a gate in the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit, regulates the transmission of information from the EC to the CA3 region, subsequently influencing CA1 pyramidal neurons. Consequently, the AD pathology originating in the EC also impacts the DG and CA3 subregions [43]. Furthermore, the impairment of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in early AD may lead to neuronal degeneration in the EC due to a reduction in newly formed axonal targets in the DG [47]. Consequently, significant neuronal death in the EC results in axonal denervation from the perforant pathway and synaptic loss in the DG dendrites, thereby fundamentally disrupting dendritic and axonal integrity and, in turn, hippocampal circuitry [48, 49]. Postmortem studies in AD patients have indicated a progressive synaptic loss in the SRLM from normal individuals to those with mild cognitive impairment and further to AD [50]. Additionally, notable atrophy of the SRLM was observed in mild AD cases [51]. DG granule cells exhibit early morphological changes that worsen as AD progresses, suggesting a correlation with cognitive deficits [49]. Meanwhile, highly plastic synapses onto hippocampal dendrites are hypothesized to be critical for learning and memory [52]. Therefore, dysfunction in neuroplasticity at these synapses may directly induce cognitive impairment in AD.

In addition, this study observed a decline in spine density across all identified hippocampal areas in 3 or 6-month-old 5FAD mice, characterized by an increase in thin spines and a decrease in mushroom spines. Thin spines can transform into mushroom spines while encoding information and reacting to neuronal activity [53, 54]. In contrast to thin spines that predominantly feature N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors (NMDARs), mushroom spines, characterized by a broad postsynaptic density in their large heads, contain a higher concentration of -amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPARs), thereby enhancing synaptic functionality [55]. Therefore, a deficiency in mushroom spines enriched with AMPARs may contribute to learning and memory deficits exhibited in the AD pathophysiology, as reduced AMPAR levels are linked to the spine and synaptic immaturity and LTD [56]. Additionally, activation of the extrasynaptic NMDAR GluN2B subunit following excessive glutamate release from activated glia results in LTD, spine shrinkage, and retraction, which can ultimately promote synaptic loss [57]; the dysregulation of NMDAR subunits contributes to glutamate excitotoxicity in AD pathology [58]. Consequently, the functional imbalance of glutamatergic receptors in spines, associated with their morphology, will result in synaptopathy in AD. Furthermore, clinical studies indicate a correlation between cognitive impairment and reduced spine density, decreased spine head diameter, and increased spine length in AD patients [59, 60]. Local synaptic dysfunction in AD patients initiates several years before the onset of clinical symptoms, with cumulative deficits in neuronal plasticity leading to behavioral changes [61]. Based on prior evidence, we propose that early morphological changes in dendrites and spines within the hippocampal CA1 and DG subregions may contribute to behavioral dysfunction in 5FAD mice.

To enhance our understanding of the mechanisms contributing to structural impairments of hippocampal neurons in AD, we investigated the temporal patterns of accumulation of key pathological proteins, including A and p-Tau, and neuroinflammation. The present study showed that A deposits were prominently identified initially in the distal CA1 subregion connecting with the subiculum and the stratum pyramidale of CA1 in 3-month-old 5FAD. Additionally, p-Tau exhibited faint staining in the distal CA1 and the stratum lacunosum-moleculare of CA1 in 6-month-old 5FAD mice. Subsequently, both immunoreactivities disseminated across all hippocampal subregions. These results align with our neuromorphological data and support the prior assertion that A is primarily involved in the early stages of AD progression; meanwhile, p-Tau pathology is likely significant in the later stages [62, 63]. Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that A oligomers contribute to postsynaptic dysfunction and dendritic pathology in AD through the dysregulation of glutamatergic receptors, including NMDARs, AMPARs, and metabotropic glutamate receptors. This dysregulation may result in an imbalance of LTP and LTD and loss of dendrites and spines [64, 65, 66, 67]. Furthermore, A oligomers induce neurotoxicity via several mechanisms, such as blood–brain barrier disruption, oxidative stress, glial activation, and dysfunction of kinases and phosphatases [68, 69]. A oligomers induce the overproduction of p-Tau, with both proteins interacting synergistically through a feedback loop, independent of their aggregation into plaques and tangles, thereby impairing neuroplasticity [70]. Therefore, our findings suggest that the accumulation of A and p-Tau adversely affects neuronal structure and synaptic integrity, contributing to cognitive decline in AD.

Additionally, we investigated the inflammatory responses, identified as a third core feature of AD in 5FAD mice, alongside A plaques and NFTs [71]. At 3 months, microgliosis was primarily observed in the distal CA1 subregion, aligning spatially and temporally with A staining. Subsequently, as AD progressed, the activation of astrocytes and microglia was heightened across the hippocampus, particularly in the distal CA1, stratum oriens of CA1, and molecular layer and hilus of the DG, where immunoreactivity mirrored the accumulation of A and p-Tau. Inflammatory cytokine production was observed in the hippocampus of 5FAD mice from an early age. Meanwhile, substantial evidence exists in AD patients and animal models regarding the inflammatory response contribution to the disease pathology [72]. In the early stages of AD, A deposition triggers microglial activation and the recruitment of astrocytes. Moreover, glia-secreting inflammatory cytokines, including TNF, IL-1, and IL-6, can increase A accumulation and promote hyperphosphorylation of tau proteins. This process establishes a detrimental cycle that leads to additional glial activation and cytokine production [73, 74, 75]. Furthermore, A can stimulate the release of complement protein C3 in astrocytes, and the binding of C3 to microglial or neuronal receptors may influence A phagocytosis or dendritic morphology, respectively, contributing to synaptic deficits in AD [76]. This study identified a close temporal relationship among pathological protein accumulation, neuroinflammation, neuroarchitecture, and behavioral impairment, suggesting that these interconnected factors may collectively contribute to synaptic and cognitive dysfunction in AD.

Arc, an immediate early gene, and PSD-95, a scaffolding protein, both situated post-synapse, regulate synaptic homeostasis through distinct mechanisms. Arc promotes the endocytosis of AMPARs by interacting with endocytic machinery and alters dendritic spine morphology by regulating cytoskeletal proteins [77, 78, 79]. PSD-95 influences the trafficking and localization of postsynaptic components, including ion channels, signaling molecules, cytoskeletal elements, and glutamate receptors [80, 81]. Consequently, Arc or PSD-95 dysfunction induces abnormal synaptic plasticity and neuronal morphology. In AD pathology, Arc and PSD-95 contribute directly to disease progression through their respective roles in A production by interacting with presenilin 1 [82] and the essential involvement in the neurotoxic pathway of A and p-Tau [83]. Conflicting observations have been noted regarding the up- or downregulation of Arc and PSD-95 expressions in the brains of AD patients and animal models; however, both homeostatic dysfunctions may contribute to synaptopathy [84, 85]. These contrasting expression patterns may be linked to varying disease severities or susceptibility among brain regions in the studied subjects [85]. This study confirmed a decrease in the expression of both proteins in the hippocampus of 5FAD mice from 6 months of age. This decline appears to be attributable to the hippocampus being one of the most vulnerable brain regions in AD, with pathological progression accelerating from that age. Furthermore, clinical reports indicate that decreased expressions of Arc [86, 87] and PSD-95 [88] significantly correlate with cognitive status and postmortem levels of A and p-Tau. Therefore, as AD progresses with age, postsynaptic proteins associated with synaptic homeostasis, including Arc and PSD-95, may become compromised in the hippocampus, leading to synaptic degeneration, loss, and subsequent behavioral dysfunction.

While this study provides valuable insights into the age-dependent structural and behavioral alterations in the 5FAD model, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, all experiments were conducted using only female 5FAD mice to reduce variability related to sex-dependent transgene expression and behavioral phenotypes [89, 90], which may limit the generalizability across sexes. Second, although the T-maze test efficiently assesses hippocampal-dependent working memory, incorporating additional cognitive paradigms would provide a more thorough behavioral profile. Third, a consistent within-subject design was not implemented at all time points to mitigate stress and maintain tissue quality, especially in aged mice. This may restrict direct associations between molecular markers and behavior. Fourth, the relatively small sample size necessitates careful interpretation of the results. Lastly, the analysis focused solely on pTau181 and excluded other phospho-tau species, such as p-Tau217, which may offer further insights into tau pathology [91, 92]. Taken together, these limitations underscore the necessity for future research to include both sexes, utilize broader cognitive assessments, employ longitudinal within-subject designs, involve larger cohorts, and integrate distinct p-Tau markers to validate and expand upon our findings.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.  Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.  Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.  Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.  Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.  Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.  Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.