1 Artificial Intelligence and Human Language Lab, Beijing Foreign Studies University, 100089 Beijing, China

2 Institute of Modern Languages and Linguistics, Fudan University, 200433 Shanghai, China

3 Center for Psychology and Cognitive Science, Lab of Computational Linguistics, Tsinghua University, 100084 Beijing, China

Abstract

There are divergent viewpoints on how Chinese compound words undergo morphological processing—especially regarding the role and timing of morphemic semantics during word recognition. Whether—and in what way—lexical and sublexical semantics influence the recognition of Chinese compound words remains unclear; this issue is central to the debate between form-then-meaning and form-and-meaning processing models.

We investigated morphological effects on compound processing by recording event-related potentials (ERPs) to Chinese compound targets that were preceded by five prime types: W+M+, W–M+, W–M– (W = whole-word semantics, M = morphemic meaning, “+” = congruent, “–” = incongruent), a purely semantic prime, and an unrelated prime. This design simultaneously controlled prime-target relatedness at both the morphemic and whole-word levels.

The results showed that, across both the 100–300 ms and 300–500 ms windows, the W–M+ and W–M– conditions produced statistically equivalent priming effects, suggesting that the semantic content of individual morphemes contributes only minimally to recognizing the compound as a whole.

These findings align more closely with morphological models proposing parallel processing of form and meaning, as opposed to frameworks that assume a strictly hierarchical or step-by-step sequence.

Keywords

- psycholinguistics

- semantics

- evoked potential

- reading

- Chinese compound word

Morphological processing is concerned with whether sub-lexical information is accessed during word recognition and how constituent morphemes are connected [1, 2]. Specifically, morphemes are often considered the smallest units of meaning in a language and are used to create morphologically complex words. For instance, “farmer” is a morphologically complex word made up of two morphemes “farm” (base) and “er” (suffix). A dominant view of morphological processing is that language processing systems will analyse the morphological units of complex words before they are able to capture the meaning of the whole word. The early decomposition process is based solely on the form of the morpheme, without considering how the unit maps to the meaning of the word of which it is a part, hence orm-then-meaning. In light of this view, complex words will be compulsorily orthographically segmented into morphemic units in a serialized and semantically blind manner. In other words, morphemic information will be automatically processed at an early stage.

By contrast, advocates of form-and-meaning models contend that once a complex word’s visual form is recognized, its overall meaning is accessed directly, without first splitting the word into morphemic components and recombining them [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. Building on this idea, the morphologically unmediated connectionist view proposes that the mapping from word form to meaning is achieved through a learned network of associations, rather than through explicit analysis of morphemes. In this framework, complex words are processed as holistic entities: the neural network, developed through exposure to language, directly links the visual form of a word to its semantic representation. This process operates in a distributed and parallel manner, meaning that semantic activation emerges automatically from the orthographic input without the need for an intermediary stage of morphological segmentation. Some neuroimaging and behavioral evidence further supported this view, indicating that word recognition can bypass the traditional, step-by-step morphological parsing in favor of a more integrated, connectionist process [5, 9].

In most languages, compounding is the principal morphological process for creating new words [10, 11]. In contrast to inflectional and derivational morphemes, the morphological processing mechanisms of compound words require further attention due to the scarcity and instability of existing findings [12]. Inflectional morphemes modify a root word to express grammatical features, such as tense or number, while derivational morphemes change the meaning or category of a root word (e.g., adding “-ness” to “happy” to form “happiness”). Compound words, on the other hand, are formed by combining two or more independent morphemes or words (e.g., “notebook” or “firefighter”). The morphological processing of compound words is distinct, as it involves combining whole words rather than just morphemes. The fundamental question in the study of compounds remains whether they are represented and treated as unitary lexical units or as combinatorial constituents. While one study clearly supported the idea of accessing constituent morphemes before accessing whole compounds, other neuroimaging studies have suggested that compound words are processed at the whole-word level [13].

Evidence in favour of the morphological decomposition account comes mainly from form-priming paradigms, in which compound words like “railway” can be primed by their constituent morphemes “rail” or “way”. However, some studies have argued that priming effects of constituents and compounds cannot be taken as strong evidence of decomposition, because such priming effects may arise from the full lexical-level semantic correlation of prime-target pairs [14]. The intrinsic relationship between semantic, morphological, and formal similarities is widely acknowledged, and it is these “confusions” that genuinely reflect the interconnections between words. However, isolating the specific contribution of morphemic information to the recognition of complex words remains a challenging task. Likewise, Marslen-Wilson et al. [15] argued that experiments probing morphological influences on complex-word recognition must be designed so that any potential overlap of form and meaning is eliminated, thereby preventing confounding effects.

To minimize this confusion, several investigations have examined compound morphology while carefully matching the lexical frequencies of both the whole compound and its individual constituents. For example, eye-tracking studies of compound words in English [16], Finnish [17], and Dutch [7] have shown simultaneous effects of component frequency and full-form frequency at early stages, before the entire compound is completely scanned. An electroencephalography (EEG) study of English compound words even showed that word frequency affects the amplitude of P100, indicating that lexical-semantic information becomes available within roughly the first 100 ms of word processing [3]. These results converged to support the notion that emphasizes the simultaneous processing of form and meaning, rather than a serial or hierarchical account.

Nevertheless, Baayen et al. [18] suggested that surface frequency effects may not indicate the activation of distinct representations during lexical access or higher-level processing. Rather, the surface frequency effect is more likely to reflect the combinatorial characteristics of morphemes stored in lexical memory, as this information is crucial for differentiating true (e.g., hat in hatless) from false morphological relationships (e.g., hat in chat). In other words, the frequency of a compound word could be interpreted as the joint frequency of its morphological components.

Marslen-Wilson and Zhou [19] took an approach quite different from the frequency-matching methods noted above. They built prime-target pairs that systematically varied in transparency, morphology, and overall semantics, thereby probing how morpho-semantic cues influence compound recognition. For example, the transparent compound “teacup” facilitates recognition of “teapot”, whereas another transparent item “headache” does not speed processing of “headscarf”. No facilitation emerged when opaque or pseudo-compounds were paired with their constituent morphemes—“blackmail” failed to prime “black” or “mail”, and “shamrock” failed to prime “sham” or “rock”. If mere repetition of a morpheme were sufficient, any shared constituent should enhance target recognition regardless of whole-word meaning; instead, priming hinged on the semantic relationship between the complete prime and target [20]. By manipulating transparency in this manner, the study greatly reduced form-meaning overlap and isolated the impact of specific morphological factors.

In particular, Chinese writing and linguistic structure are best described as morpho-syllabic, uniquely combining morphology and syllabic phonology within each character [2, 21]. Regarding the cognitive and neural correlates of Chinese morphological processing, some interesting findings have been made thus far. The first line of research is concerned with the representational units of Chinese compound words in the mental lexicon. For example, by using a repetition priming paradigm, Gao et al. [22] demonstrated that for intermediate-level learners, Chinese compounds can be acquired through morphemes or words, whereas advanced-level learners and native speakers of Chinese are likely to adopt the whole-word path. The authors further suggested that learners tend to rely more on whole words as a processing strategy as their language level and reading experience develops. However, as Chen et al. [23] recently pointed out, one limitation of the repetition priming paradigm might be that orthographic effects were not well eliminated from the semantics, which might need to be addressed in future investigations.

Additionally, in light of the high temporal resolution of EEG and Event-Related Potentials (ERP) techniques, Chung et al. [1] identified the functional role and time course of the relation between constituent morphemes during the recognition of Chinese compound words. Utilizing an unmasked priming paradigm with a 57 ms stimulus-onset asynchrony (SOA), the researchers tightly controlled their experimental materials at the level of morphological structure. Specifically, the materials included subordinate compounds, where one component modifies the other (e.g., subordinate compound “汽车” (qi4 che1, gas-car, automobile), where “汽” (gas) modifies “车” (car)), and coordinative compounds, where both components are equally meaningful (e.g., coordinative compound “花草” (hua1 cao3, flower-grass, plant), where “花” (flower) and “草” (grass) are equally important). In addition to the typical N400 semantic priming effect, they also identified an earlier P250 component (220–300 ms), which the authors proposed reflects the activation of semantic memory networks during semantic processing. Notably, the effect of morphological structure was observed in the time window of the P250 component, indicating that morphological structure may automatically impact semantic processing during the recognition of Chinese compound words.

Contrary to early morphological processing claims, nevertheless, some investigations have shown that morphological constraints are encoded at a late stage of lexical processing on Chinese compound words [2]. Native Chinese speakers participated in a visual lexical‑decision experiment, in which they judged whether presented stimuli—consisting of genuine Chinese compound words, pseudowords, and orthographically legal non‑words—were real words. Their electrophysiological results showed that semantic processing (300–450 ms) occurred earlier than morphological processing (450–570 ms) and further localized the differences between morphological parsing (in the left inferior frontal gyrus) and semantic analysis (in a broader fronto-temporal network) [2].

Overall, there are divergent views on the morphological processing mechanism of Chinese compound words, particularly regarding the functional role and temporal signature of morphemic semantics during word recognition. It is still uncertain whether and how morphemic semantics might influence the recognition of Chinese compound words, a question that could significantly inform the debate between the form-then-meaning and form-and-meaning processing models. Three methodological issues hamper a definitive account of Chinese compound word recognition. First, most ERP studies adopted long stimulusonset asynchronies (SOAs

One possible resolution could be to extend the repetition priming paradigm [22] to a semantic priming paradigm, so as to mitigate the confounding issues from orthographic effects [23], while also combining priming paradigm with ERP techniques to provide insights into the time courses of morphemic modulations. Specifically, related ERP studies on Chinese morphological processing have mostly employed masked priming techniques, while several studies have clearly demonstrated that masked and unmasked priming effects involve different cognitive processes [24, 25, 26]. For instance, diffusion-model analyses have shown that masked priming chiefly reduces the encoding time of the target, whereas unmasked priming is driven by greater familiarity with the prime—target compound cue [27].

In a recent masked-priming experiment [28], we showed that whole-word semantics can be activated as early as 100–250 ms under a 50-ms SOA, whereas purely morphemic semantic overlap failed to elicit a comparable effect. However, the use of forward masks in that study prevented us from tracking later, consciously mediated stages of lexical-semantic processing. Building directly upon those findings, the present study removed the masks while keeping the SOA and prime-target manipulations identical, thereby allowing us to test whether the early advantage for wholeword semantics persists into subsequent processing windows and to further examine the putative additive versus interactive roles of morphemic meaning across time. In other words, we will thus adapt an unmasked priming technique along with a short SOA [1] to further tackle this topic.

In addition, the relationship between primes and targets will be manipulated at both the morpheme and the whole-word levels to explore the representational units of Chinese compound processing. Taking the target compound “干旱” (gan1 han4, “drought”) as an example, which is composed of the morphemes “干” (gan1, “dry”) and “旱” (han4, “drought” or “aridity”), five priming conditions were established to manipulate both whole-word semantics (W) and morpheme-level meanings (M): (1) W+M+ condition: The prime “干燥” (gan1 zao4, “arid”) shares both the overall semantic meaning and a common morpheme (“干”) with the target. (2) W–M+ condition: The prime “干洗” (gan1 xi3, “dry-cleaning”) shares the morpheme “干” (indicating “dry”) with the target but differs in whole-word semantics. (3) W–M– condition: The prime “干涉” (gan1 she4, “interfere”) shares neither the overall semantic similarity nor the relevant morpheme meanings with the target. (4) Semantically related condition: The prime “枯萎” (ku1 wei3, “withered”) is semantically related to “干旱” (drought) but does not share any morphological or orthographic similarities. (5) Unrelated condition: The prime “歌曲” (ge1 qu3, “song”) is unrelated in meaning, morphology, and orthography to the target.

Overall, our experiment utilises a short SOA together with a semantic (non‑repetition) priming paradigm, which (i) minimises orthographic confounds, (ii) allows us to test whether semantics facilitate early morphological processing. These additions make clear that our work introduces a novel combination of short-SOA semantic priming, thereby providing new evidence for the time course of Chinese morpheme processing. We predicted that, if semantic information intrudes on the earliest stage of morphological analysis [2, 22, 28, 29], priming magnitudes for the W+M+, W–M+, and W–M– conditions would already diverge in the initial time window. In contrast, we expected the W–M+ and W–M– conditions to show comparable effects—an outcome that, within a connectionist framework that does not require morphemic mediation [6, 30, 31], would indicate that the meanings of individual morphemes contribute little to whole-word recognition. If we adopt the form-then-meaning account, in which decomposition and whole-word access operate consecutively, the observed pattern of data would be reversed.

Twenty-seven college students (mean age = 21.7 years, range = 19–28 years, 14 males) in Beijing were recruited to participate in this experiment for monetary compensation. They were all right-handed according to the Edinburgh Handedness Test and reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision prior to the experiment. None of them reported any history of mental or neurological impairment. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, all participants signed an informed consent form before the experiment. The experiment complied with institutional guidelines for human research and received prior approval from the School of Psychology’s Ethics Committee at Tsinghua University.

The experiment utilized 110 Chinese two-character target words. Of these targets, 55 were real words and 55 were pseudo-words, a design chosen to balance the number of trials requiring affirmative (positive) and negative responses and thereby reduce response bias. All target words were carefully selected and classified based on their morphological composition and semantic properties. Each target word begins with a first constituent morpheme that is homomorphic, meaning that its multiple meanings are semantically unrelated. To ensure rigor in stimulus selection, all ambiguous morphemes were chosen according to strict criteria outlined in the Modern Chinese Dictionary. Specifically, only those morphemes whose meanings showed no inter-correlation were included. In this context, we distinguish between homomorphic and polysemantic morphemes: a polysemantic morpheme is one in which the different meanings are related to one another, whereas a homomorphic morpheme has meanings that are completely independent of one another. This distinction is crucial for our experimental design, as it minimizes potential confounds in morphological processing and ensures that any observed effects can be attributed to the intended manipulation rather than to semantic overlap. For example, the “拼, pin1” in the target word “拼音, pin1 yin1/phonetic” means “together”, and it also means “to do desperately”, which can form “拼命, pin1 ming4/desperately”. Each compound target was primed by W+M+, W–M+, W–M– (W = whole-word semantics, M = morpheme meaning, + = congruent, and – = incongruent), semantically related and unrelated primes. For example, the targets (e.g., “拼音”) were preceded by W+M+ (e.g., “拼读, pin1 du2/pronounce”), W–M+ (e.g., “拼盘, pin1 pan2/platter”), W–M– (e.g., “拼命, pin1 ming4/desperately”), semantically related (e.g., “字母, zi4 mu3/alphabet”) (semantically related but neither morphologically nor orthographically related) and unrelated primes (“利益, li4 yi4/benefits”). Each ambiguous morpheme was pronounced the same in all cases. Furthermore, if a target contained an ambiguous character, we presented that character in its dominant sense, whereas in a homomorphic prime the character was used in one of its less frequent meanings. Every stimulus word was high-frequency, selected from the Modern Chinese Word-Frequency Dictionary. A separate group of 26 native Mandarin speakers—who did not take part in the EEG session—rated the semantic relatedness of each prime-target pair on a six-point scale (1 = “completely unrelated”, 6 = “highly related”). Purely semantic pairs averaged 4.59, while W+M+ pairs averaged 4.57; the two means did not differ reliably (p

The task was organised into five separate blocks, with 110 trials presented in each block. In every block, 50% of the trials presented real-word targets, while the remaining 50% consisted of pseudo-word filler trials. Among the real-word trials, the primes were evenly distributed across five conditions. Specifically, each block comprised 55 real-word trials organized into five prime types (11 trials per prime condition). This design ensured balanced representation of each prime type within each block. Furthermore, no target word was repeated within any block. Both the block sequence and the trial sequence inside each block were randomized to prevent order effects. Overall, the experiment consisted of a total of 550 trials.

All participants were comfortably seated in an ERP lab with sound attenuation and dim lighting. They were asked to fixate on the centre of the screen and avoid any physical movement, but to relax during the formal experiment. All stimuli were displayed word by word on a liquid crystal computer screen at a distance of 80 cm from the subject. Each trial started with a “+” sign displayed for 500 ms. Then, the prime word, shown in PMingLiU font, appeared for 50 ms. This was followed by the target word, presented in LiSung font, which remained on the screen until the participant responded or until 2000 ms had passed. Participants were instructed to decide as quickly and accurately as possible whether the target word was real or not. Finally, the “—” was displayed for 2000 ms to signal the end of the decision phase, during which participants were free to blink.

Before the main experiment, participants completed a practice block of 30 prime-target pairs. Participants who achieved accuracy above 80% were allowed to proceed the formal experiment. After each block, participants were given a short pause of roughly 3–5 minutes. From electrode setup to completion of the final trial, the entire session lasted approximately 1.5–2 hours.

Continuous EEG was recorded from 62 Ag/AgCl channels in an elastic cap laid out according to the international 10–20 system (EasyCap, Brain Products, Gilching, Germany). Horizontal EOG was captured with an electrode at the right outer canthus, and vertical EOG with an electrode positioned beneath the left eye. The impedance of all electrodes was kept below 10 k

Using Brain Vision Analyzer 2.0 (Brain Products, Gilching, Germany), we first excluded trials containing eye or muscle artefacts and then computed target‑locked average ERPs offline. All channels were subsequently re-referenced to the average of the left and right mastoid electrodes. ERPs were recorded from 200 ms before to 600 ms after the onset of the target word (200 ms before the target baseline). Ocular artefacts were initially flagged by Brain Vision Analyzer 2.0’s automated algorithm and then verified through manual inspection. Offline EEG data were band‑pass filtered between 0.05 Hz and 30 Hz (zero phase shift mode, 24 dB/oct). Periods exceeding

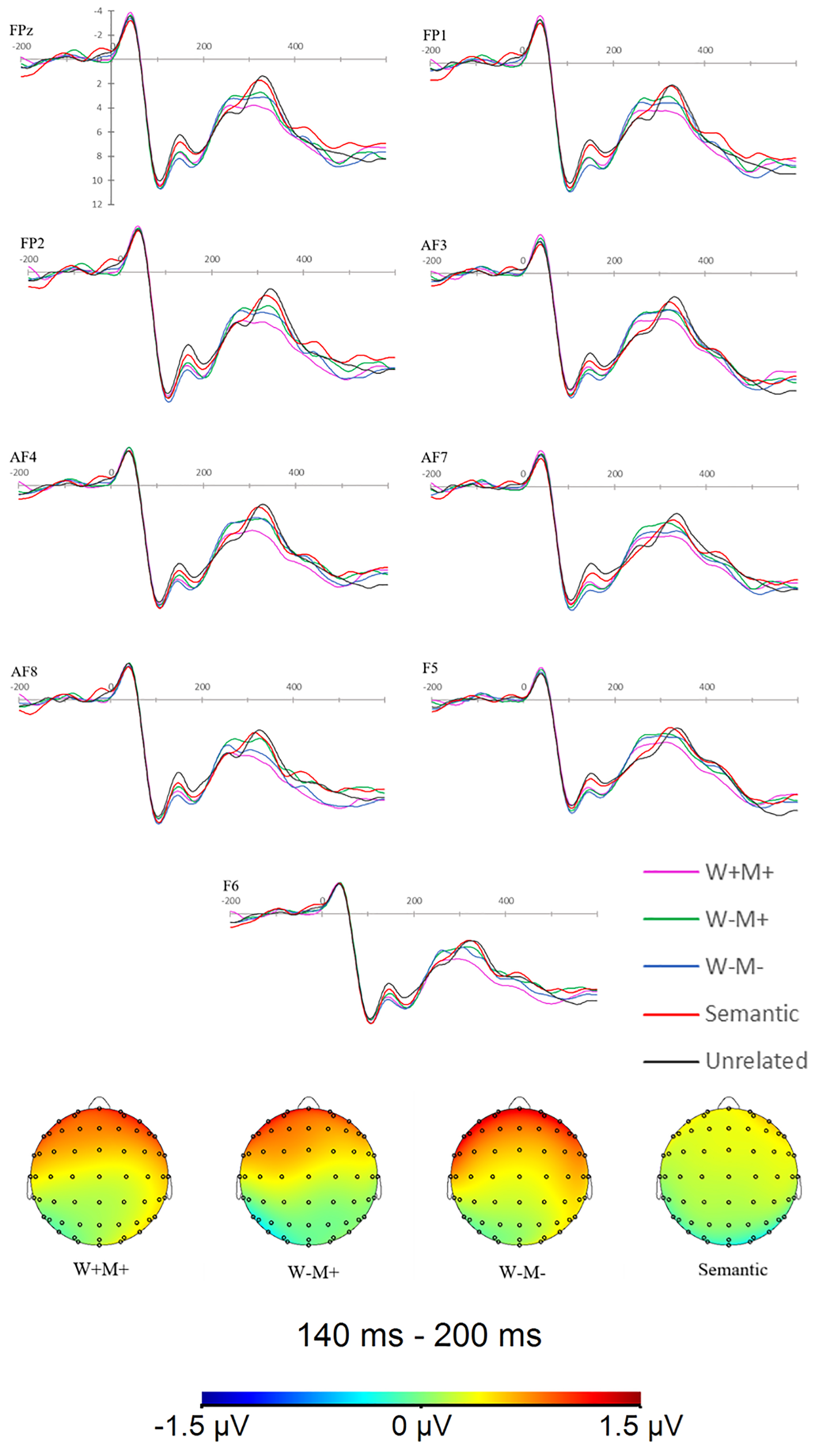

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Frontal ROI effect in the 140–200 ms window. Grand-average ERP traces recorded at nine anterior-frontal sites (FPz, FP1, FP2, AF3, AF4, AF7, AF8, F5, F6) and the corresponding scalp maps of related-minus-unrelated difference waves for the 140–200 ms interval following target onset. Only the frontal ROI showed a significant effect (all other ROIs, ps

For every latency window, we performed a within-subjects ANOVA that included three factors: Prime Type (W+M+, W–M+, W–M–, semantic-only, and unrelated), Hemisphere (left versus right), and Scalp Region (anterior, central, posterior). Crossing Hemisphere (left vs. right) with Scalp Region (anterior, central, posterior) produced six lateral regions of interest (ROIs), each defined by six electrodes: left-anterior (F5, F3, F1, FC5, FC3, FC1); right-anterior (F6, F4, F2, FC6, FC4, FC2); left-central (C5, C3, C1, CP5, CP3, CP1); right-central (C6, C4, C2, CP6, CP4, CP2); left-posterior (P5, P3, P1, PO7, PO3, O1); and right-posterior (P6, P4, P2, PO8, PO4, O2). The ERP signals within each region were averaged to yield a single value for each ROI. All analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Assumptions for repeated-measures ANOVA were checked: residual normality (Shapiro-Wilk), variance homogeneity across mean RTs (Levene), and sphericity (Mauchly). Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied when sphericity was violated. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were Bonferroni-adjusted by multiplying each raw p by the number of contrasts (k = 10); adjusted values below 0.05 were considered significant. In the 140–200 ms time window, the two within-participant factors involved were Prime Type (W+M+, W–M+, W–M–, semantically related, or unrelated), and nine anterior-frontal electrodes. Behavioral data were likewise analyzed with an ANOVA that treated Prime Type as the single within-subjects factor.

Table 1 summarises the mean reaction times and error rates for each of the five priming conditions. A repeated-measures ANOVA was run on the dataset, treating Prime Type (W+M+, W–M+, W–M–, semantic-only, and unrelated) as the single within-participant factor.

| Priming condition | Reaction times (ms) | Std. Error | Error rates (%) | Std. Error |

| W+M+ | 659.06 | 17.55 | 3.2 | 0.004 |

| W–M+ | 682.78 | 17.63 | 4.7 | 0.007 |

| W–M– | 689.93 | 16.82 | 6.3 | 0.006 |

| Semantic | 672.91 | 15.62 | 3.4 | 0.004 |

| Unrelated | 696.13 | 16.64 | 5.0 | 0.006 |

W represents whole-word semantics, M represents morphemic meaning; “+” denotes congruence and “–” denotes incongruence.

Reaction-time analysis showed a robust main effect of Prime Type [F(4,104) = 15.096, p

For error rates, the main effect of Prime Type [F(4,104) = 12.156, p

As shown in Fig. 1, between 140 and 200 ms after target onset we found a significant main effect of Prime Type [F(4,104) = 3.115, p = 0.018,

As shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2, in the time window of 250–300 ms, the priming effects of the four related conditions begin to diverge. ANOVA yielded a significant main effects of Prime Type [F(4,108) = 2.902, p = 0.025,

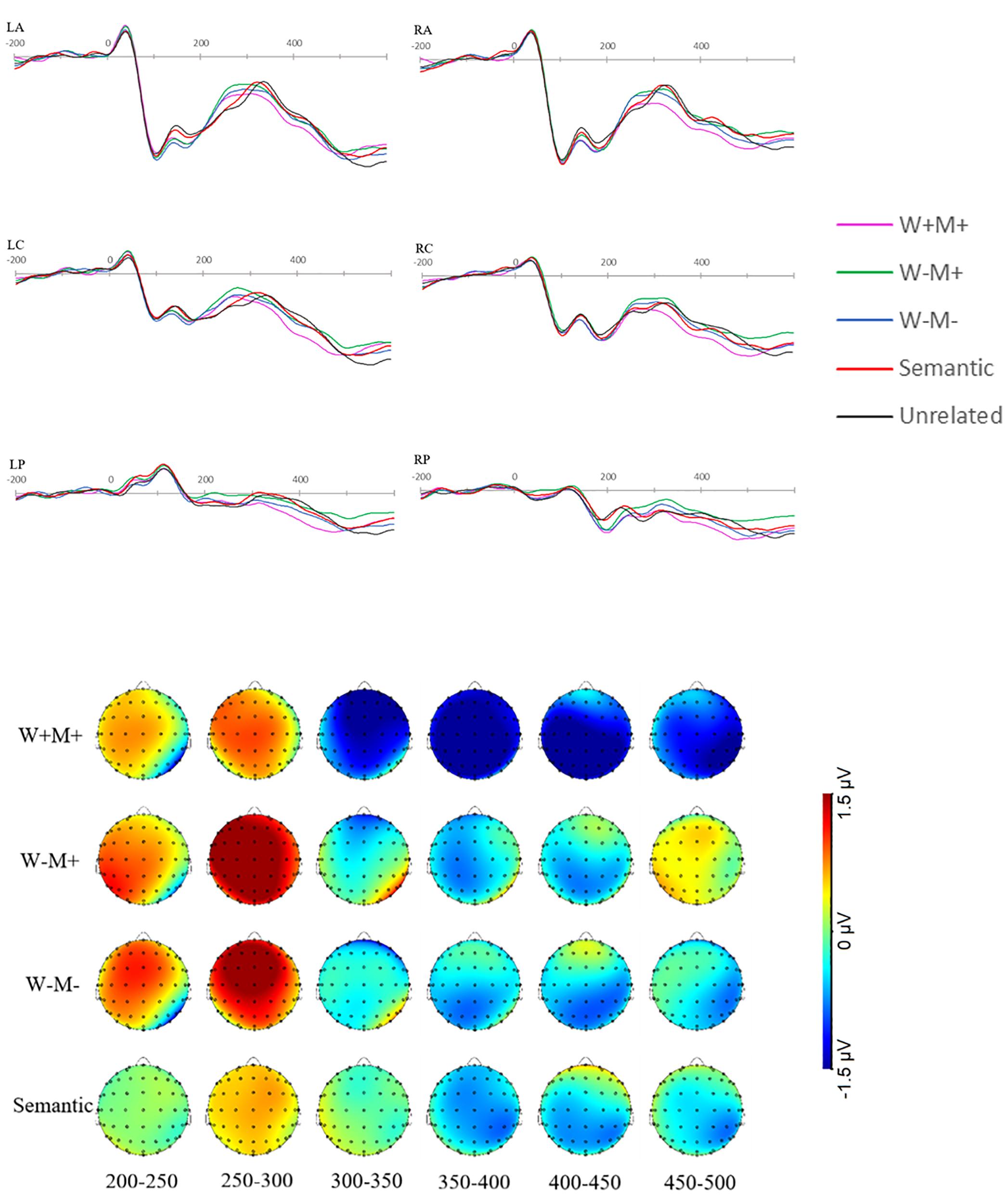

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Priming effects for the four related conditions (200–500 ms). Grand-average ERP traces for the six lateral ROIs, together with scalp maps depicting the unrelated-minus-related difference waves—where W denotes whole-word semantics, M denotes morphemic meaning, “+” indicates congruence and “–” incongruence—computed for the 200–500 ms window after target onset.

| W+M+ vs. Unrelated | W–M+ vs. Unrelated | W–M– vs. Unrelated | Semantic vs. Unrelated | |||||||||

| Anterior | Central | Posterior | Anterior | Central | Posterior | Anterior | Central | Posterior | Anterior | Central | Posterior | |

| 200–250 | 0.490 | 0.560 | 0.664 | 0.338 | 0.191 | 0.516 | 0.236 | 0.366 | 0.761 | 0.971 | 0.951 | 0.803 |

| 250–300 | 0.219 | 0.180 | 0.406 | 0.011* | 0.009** | 0.031* | 0.019* | 0.032* | 0.219 | 0.315 | 0.353 | 0.401 |

| 300–350 | 0.003** | 0.023* | 0.162 | 0.503 | 0.934 | 0.496 | 0.325 | 0.589 | 0.970 | 0.968 | 0.959 | 0.788 |

| 350–400 | 0.004** | 0.001** | 0.010* | 0.571 | 0.426 | 0.887 | 0.562 | 0.276 | 0.416 | 0.443 | 0.235 | 0.604 |

| 400–450 | 0.036* | 0.001** | 0.004** | 0.716 | 0.338 | 0.729 | 0.698 | 0.234 | 0.307 | 0.899 | 0.269 | 0.428 |

| 450–500 | 0.097 | 0.014* | 0.027* | 0.636 | 0.698 | 0.529 | 0.649 | 0.469 | 0.383 | 0.782 | 0.279 | 0.463 |

*p

| W+M+ vs. W–M+ | W+M+ vs. W–M– | W–M+ vs. W–M– | W+M+ vs. Semantic | |||||||||

| Anterior | Central | Posterior | Anterior | Central | Posterior | Anterior | Central | Posterior | Anterior | Central | Posterior | |

| 200–250 | 0.560 | 0.223 | 0.074 | 0.286 | 0.538 | 0.853 | 0.669 | 0.686 | 0.197 | 0.387 | 0.371 | 0.364 |

| 250–300 | 0.033* | 0.046* | 0.040* | 0.042* | 0.188 | 0.463 | 0.826 | 0.419 | 0.212 | 0.920 | 0.711 | 0.904 |

| 300–350 | 0.017* | 0.018* | 0.032* | 0.008** | 0.035* | 0.106 | 0.913 | 0.679 | 0.508 | 0.009** | 0.023* | 0.135 |

| 350–400 | 0.051 | 0.012* | 0.011* | 0.008** | 0.014* | 0.064 | 0.821 | 0.869 | 0.514 | 0.049* | 0.025* | 0.055 |

| 400–450 | 0.177 | 0.019* | 0.004** | 0.079 | 0.040* | 0.052 | 0.962 | 0.849 | 0.468 | 0.010* | 0.004** | 0.021* |

| 450–500 | 0.014* | 0.002** | 0.001** | 0.227 | 0.141 | 0.213 | 0.289 | 0.215 | 0.127 | 0.034* | 0.028* | 0.082 |

*p

As illustrated by Table 2 and Fig. 2, both the W–M+ and W–M– conditions showed a significantly greater positive amplitude than the unrelated condition in the 250–300 ms time period, mainly concentrated in the anterior and central regions. In addition, as shown in Table 3, the W–M+ and W–M– conditions both showed significant differences compared with the W+M+ condition during the 250–300 ms window, indicating an early semantic influence.

As shown in the topographic map in Fig. 1, in the 300–500 ms time window, compared to the unrelated condition, only the W+M+ condition produced a significant priming effect; none of the other related primes reached significance (see Table 2 for details). Even compared to the other three related priming conditions (W–M+, W–M–, semantic-only), W+M+ showed a significant effect (as shown in Table 3). Moreover, Table 3 and Fig. 3 show that the priming magnitudes for W–M+ and W–M– were statistically indistinguishable in both the early and the late latency windows.

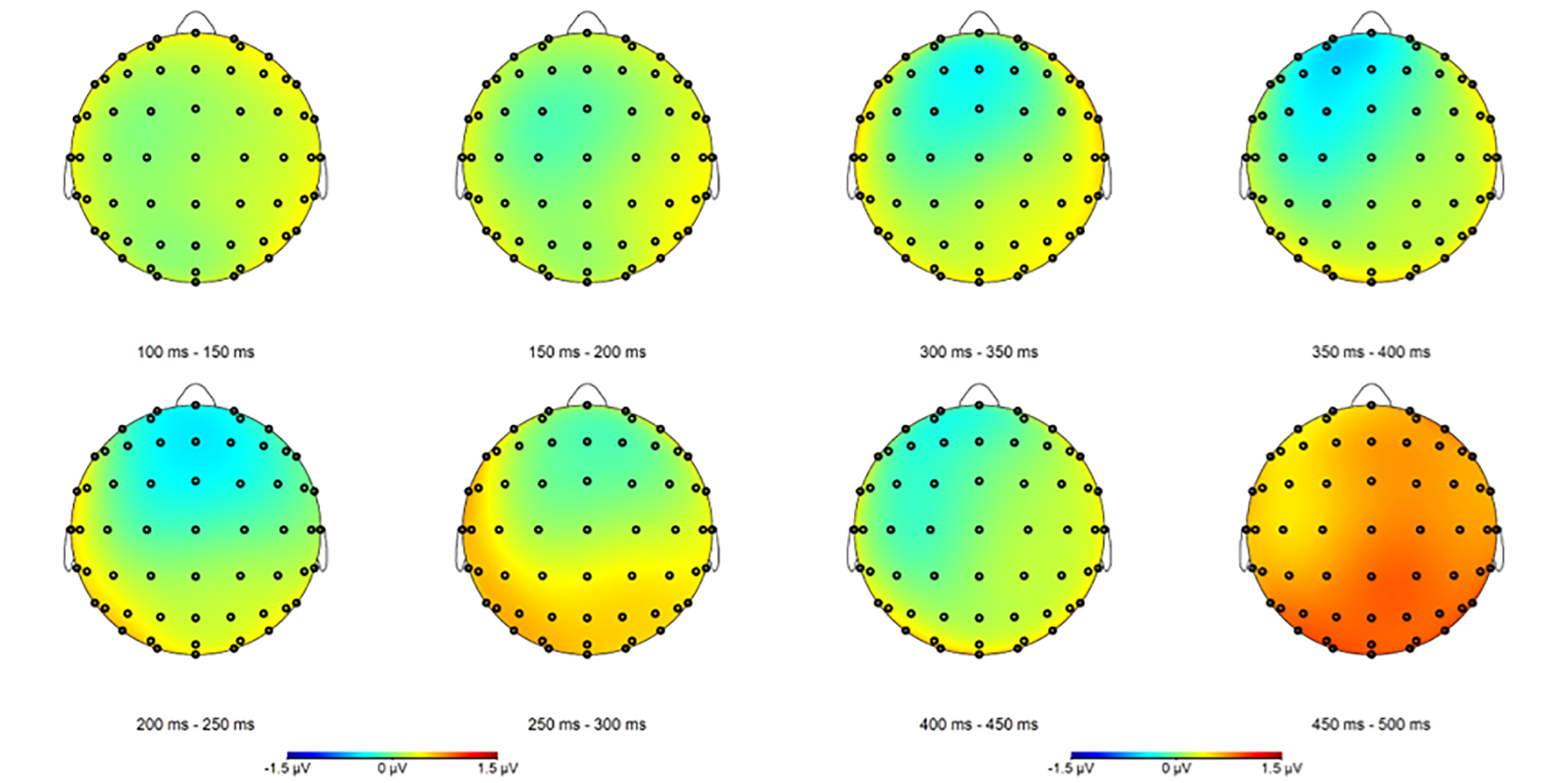

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Topographies of the W–M– minus W–M+ difference (100–500 ms). Scalp maps of the W–M– minus W–M+ difference wave displayed for the 100–500 ms interval following target onset. Here, W represents whole-word semantics, M represents morphemic meaning; “+” denotes congruence and “–” denotes incongruence.

This study aimed to examine the role of lexical and sublexical semantics in Chinese compound word recognition by using a semantic priming paradigm, which could further elucidate the neuro-cognitive mechanisms of Chinese morphological processing. Existing hypotheses about the morphological processing of complex words fall into two main camps. First, the form-then-meaning views describe a process whereby a complex word is accessed only after its orthographic form has been decomposed into morphological constituents and then isolated morphemic representations are recombined [32, 33, 34, 35]. Conversely, form-and-meaning frameworks propose that a word’s overall meaning is accessed directly, bypassing any intermediate morphemic segmentation or recombination [3, 9, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40]. How Chinese compound words are morphologically processed remains contentious [1, 2, 28, 41, 42, 43, 44]. By simultaneously manipulating the semantic relationship while also controlling for the morphological, orthographic, and phonological associations of the prime-target pairs at the whole-word and morpheme levels, we found—using an unmasked priming paradigm with a short SOA (50 ms)—that the data support models positing parallel processing of form and meaning.

First, the behavioural data collectively showed significantly faster reaction times for W+M+, W–M+, and the semantic-only condition compared with the unrelated condition, with W+M+ even being significantly faster than the other three related priming conditions. Meanwhile, W+M+ and the semantic-only condition both exhibited significantly lower error rates than the unrelated condition. Overall, W+M+ produced the strongest priming effect, followed by the purely semantically related condition. This result is similar to that of Wang et al. [28], who adopted a masked priming paradigm, both showing semantic priming effects at a short SOA condition. However, this result is inconsistent with Chung et al. [1], who used a more comparable experimental paradigm (unmasked priming and short SOA). No morphological effects or semantic priming effects were found for either reaction time or error rates in Chung et al. [1].

In addition, all four priming conditions revealed significantly fewer errors compared with the W–M– condition. The difference between W–M–, W+M+, and W–M+ is mainly in the semantic similarity at the whole-word or morpheme level of the prime-target pairs, so the significantly higher error rate for W–M– may indicate the influence of semantic factors. More specifically, significant differences in response times and error rates between W–M–and W+M+ seem to better validate the early role of semantics. Moreover, these significant differences were similar to those reported by Wang et al. [28] based on masked priming. The robust facilitation observed for the purely semantic primes—and the marked contrast between the W–M–and W+M+ conditions—both reinforce the notion that whole-word semantics become active at an early stage. This line of evidence is in favour of the whole-word processing account of Chinese lexical processing [20, 41, 45, 46, 47], such that Chinese words are stored and accessed holistically in the mental lexicon.

In contrast to behavioural data, EEG provides high temporal resolution for capturing the dynamics of neural activity during visual word recognition [9]. In the earliest 140–200 ms time window, it was found that ERP waveforms generated by W+M+, W–M+, and W–M– priming conditions were significantly more positive-going than the unrelated controls in the anterior frontal electrodes, while the purely semantic-related condition showed no such positivity. Furthermore, there were no significant differences between the W+M+, W–M+ and W–M– priming effects during this initial latency window, consistent with Wang et al. [28]. These three priming conditions are similar in that they all contain the same morpho-orthographic information, so this early priming effect may be triggered by the orthographic similarity of the prime-target pairs. In addition, the early equivalent priming effect of the three conditions may also characterize the morpho-orthographic decomposition. The frontal distribution converges with some evidence that morphological-semantic parsing of Chinese compound words may rely on left anterior generators [2]. Two task-specific factors may account for the absence of posterior effects here. First, an ultra-short SOA (50 ms) combined with high morphological predictability preferentially elicits early anterior N/P150–N250 activity, reflecting rapid form-to-meaning mapping and predictive processing, while robust centro-parietal N400 integration has insufficient time to develop [48, 49, 50, 51]. Second, high-frequency targets reliably attenuate the amplitude of the classic centro-parietal N400 [52, 53, 54], thereby making frontal differentials more salient. As a result, a reliable differential wave was observed only in the frontal ROI, with no significant effects in other regions.

Importantly, priming magnitudes for the W–M+ and W–M– conditions were statistically equivalent in both the 100–300 ms and 300–500 ms windows, implying that sublexical morphemic semantics exert little influence on recognising the compound. This result is consistent with Wang et al. [28], indicating that morpho-semantic information alone seems to have little effect on the recognition of compound words from which they are built, regardless of whether the subjects are recognizing unconsciously (masked priming/SOA = 50 ms) or consciously (unmasked priming/SOA = 200 ms) or a state in between (unmasked priming/SOA = 50 ms). A similar pattern has been reported for English compounds: “teacup” speeds recognition of “teapot”, whereas “headache” fails to facilitate “headscarf”, suggesting that whole-word semantic relatedness—not shared morphemes—drives the priming effect [20].

In contrast, using the same unmasked and short SOA priming paradigm, Chung et al. [1] found significant morphological effects in the P250 component (220–300 ms) and further suggested that morphological structure automatically influences semantic information processing. Specifically, positive priming effects were found in Chung et al. [1] for prime-target pairs with the same compound structure (coordinative compounding). Using a similar design with only SOA extended to 200 ms, Liu and McBride-Chang [55] also found an effect of morphological structure on semantic information. However, the same morphological structure tended to inhibit the processing of semantic information in Liu and McBride-Chang [55]. Chung et al. [1] attributed this to the relatively longer SOA (200 ms) and hypothesized that the effects of morphological structural information may be unconscious and that the activation of morphological structural information is likely to be very brief (SOA = 57 ms). However, neither Wang et al. [28] nor this study found a role for constituent morphemes in Chinese compound word recognition, regardless of long vs. short SOA or masked vs. unmasked priming. It is important to note that we also hypothesized, as Chung et al. [1] suggested, that morphological effects may be very transient and therefore difficult to detect. In addition, although our study controlled whole-word and morpheme-level correlations via ambiguous morphemes, it did not impose strict constraints on morphological structure. By contrast, Chung et al. [1] and Liu and McBride-Chang [55] rigorously controlled morphological structure, which may also account for the differing results.

Specifically, Kuperman [6] found that morphemes play a limited role in recognizing English compound words, while highlighting the behavioural effects of six semantic properties related to the affective and sensory connotations of compounds and their morphemes, as well as their semantic richness. The results showed that the morpho-semantic information had little effect on compound recognition, except for longer recognition times for compounds with emotionally negative morphemes (e.g., seasickness). The authors therefore argued that the data counter models requiring obligatory decomposition or dual-route processing and instead favour a framework in which orthographic cues elicit immediate, parallel access to all relevant meanings [6]. According to this view, orthographic and phonological cues can be mapped directly to meaning without the need for morphemes as mediators. The weights of semantic and orthographic connections are the result of statistical learning gained from the experience of recognizing words in context [30, 36].

In addition to the weak role of morphemes, this study also revealed early influences of whole-word semantics. In the 250–300 ms time window, both W–M+ and W–M– all elicited larger negativities than the unrelated condition, while the W+M+ and semantic-only condition did not. Since the only distinction between W+M+ and W–M– is their whole-word semantic relatedness, the markedly stronger priming for W+M+ relative to W–M– offers direct evidence that lexical-level semantic information is already engaged. Similarly, a number of related studies on the mechanisms of Chinese morphology have also shown whole-word processing in early time windows. For example, Huang et al. [42] observed early ERP differences (250–300 ms) for words and pseudowords, suggesting early automatic lexical processing. Wang et al. [28] even suggested that the brain is sensitive to semantic information as early as 100–250 ms. Other work has likewise shown that lexical‑semantic effects can emerge as early as 100–300 ms [3, 5, 8, 9, 44, 56, 57].

During the 300–500 ms post-stimulus window, W+M+ elicited significantly less-negative potentials than not only the unrelated condition but also the other three related conditions. Strikingly, the priming effects for W+M+ and the purely semantic condition began to diverge significantly as early as the 300–350 ms interval. Our ERP findings show that shared morphology on its own (W–M+ versus W–M–) produced no reliable priming, whereas primes that combined morphological overlap with whole-word semantics (W+M+) yielded greater facilitation than purely semantic primes within the 300–500 ms window. This pattern points to an additive interaction between morphological and semantic information. This finding was also confirmed by Wang et al. [28]. These interactions suggest that that morphemic activation emerges only after 300 ms, later than the lexical-semantic activation. In a similar vein, using a different task setup, Gao et al. [2] also found that semantic processing (N400, 300–450 ms) precedes morphological processing (450–570 ms). The authors explicitly proposed that morphological constraints are encoded in the later stages of Chinese compound word processing, and the left prefrontal cortex plays a crucial role in this process [2].

Curiously, the ERP analyses revealed no priming for the strictly semantic condition in either the early or the late latency window, whereas the behavioural data did show reliable semantic facilitation. By contrast, Wang et al. [28] observed significant semantic-only priming in both EEG and behavioural measures when a masked-priming paradigm was used. The SOA for both studies was 50 ms, differing only in that the mask was not included in this study. While some studies did not find a priming effect for purely semantic conditions with a short SOA [58, 59], the N400 effect was typically observed under masked repetition priming conditions [60]. Thus, purely semantic priming effect may be unstable under short SOAs. Our results confirm that whole-word semantics are activated not only under purely semantic primes but also through the differential priming observed between the W+M+ and W–M– conditions. Therefore, even if the purely semantic related condition in the present study did not show any significant effect, the significant difference between W+M+ and W–M– at an early stage could still indicate early activation of semantics.

From the perspective of processing efficiency, the preferred strategy appears to be focusing on the meaning of the whole compound word rather than its individual lexical units. First of all, the goal of reading is to access the meaning of the whole word, so giving priority attention to the whole-word meaning rather than dividing it among multiple entities may help improve processing efficiency. Second, it may be inefficient to focus on the meaning of constituents of a complex word, since even highly transparent compounds are seldom fully compositional [6]. Chinese compound words show a similar pattern; for example, the fully transparent compound “花粉” (“pollen”) is composed of the morphemes “花” (“flower”) and “粉” (“powder”). According to the Modern Chinese Dictionary, “花” means not only “flower”, but also “cost”, “philandering”, “complex color” and so on (nearly 20 senses in total). Meanwhile, in addition to the meaning of “pink”, “粉” could also denote “fans”, “vermicelli”, “powder brush” and six other meanings. Therefore, it seems to be inefficient if the whole word meaning of Chinese compounds is decomposed by constituent morphemes and then recombined.

Overall, our findings indicate that morphemic semantics on its own exerts only a minimal influence on the recognition of Chinese compound words. Moreover, lexical-semantic influences surface very early during word recognition—often preceding or at least coinciding with morphological effects. This temporal profile accords with a variety of form-and-meaning frameworks which, despite their differences, all posit that a complex word’s morphological activation is jointly shaped by its orthographic form and its meaning [4, 8, 9, 61, 62]. By contrast, other models argue that whole-word meaning can be retrieved independently of any morphemic representation [5, 6, 30, 36].

In sum, this study focused on examining the morphological processing mechanism of Chinese compound words by investigating the role of semantics at the morpheme and whole-word levels. Our findings indicate that the meanings of individual morphemes, when considered in isolation, contribute minimally to recognising Chinese compound words. Taken together, the evidence favours models in which form and meaning are processed in parallel rather than sequentially.

There are also some limitations of this study and future directions that warrant discussion. It is important to note that different languages or different morphologies or even different experimental design approaches may affect morphological processing mechanisms. These factors could be taken into account in future investigations. Moreover, the current study did not control for the morphological structure, and the experimental material only included high-frequency words, even though frequency is an important determinant of word recognition. Thus, the precise mechanisms underlying compound-word processing should be verified across more languages and experimental designs.

All data generated or analysed in this study are included in this published article. These datasets are all available upon request from the corresponding author.

YLW and MHJ designed the research study. YLW performed the research. YLW and FG analyzed the data. YLW and FG wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study received ethical clearance from the School of Psychology’s Ethics Committee at Tsinghua University, the ethical approval number 202322. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to the start of the experiment, every participant provided informed consent.

We are grateful to all anonymous reviewers, whose insightful feedback and constructive suggestions have substantially enhanced the quality of this manuscript.

This work was supported by the Major Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 62036001], and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF [grant number GZC20230286].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/JIN40569.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.