1 School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Southern Medical University, 510000 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

2 Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, 510000 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

3 Guangdong Basic Research Center of Excellence for Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine for Qingzhi Diseases, 510000 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

4 Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University, 510000 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Abstract

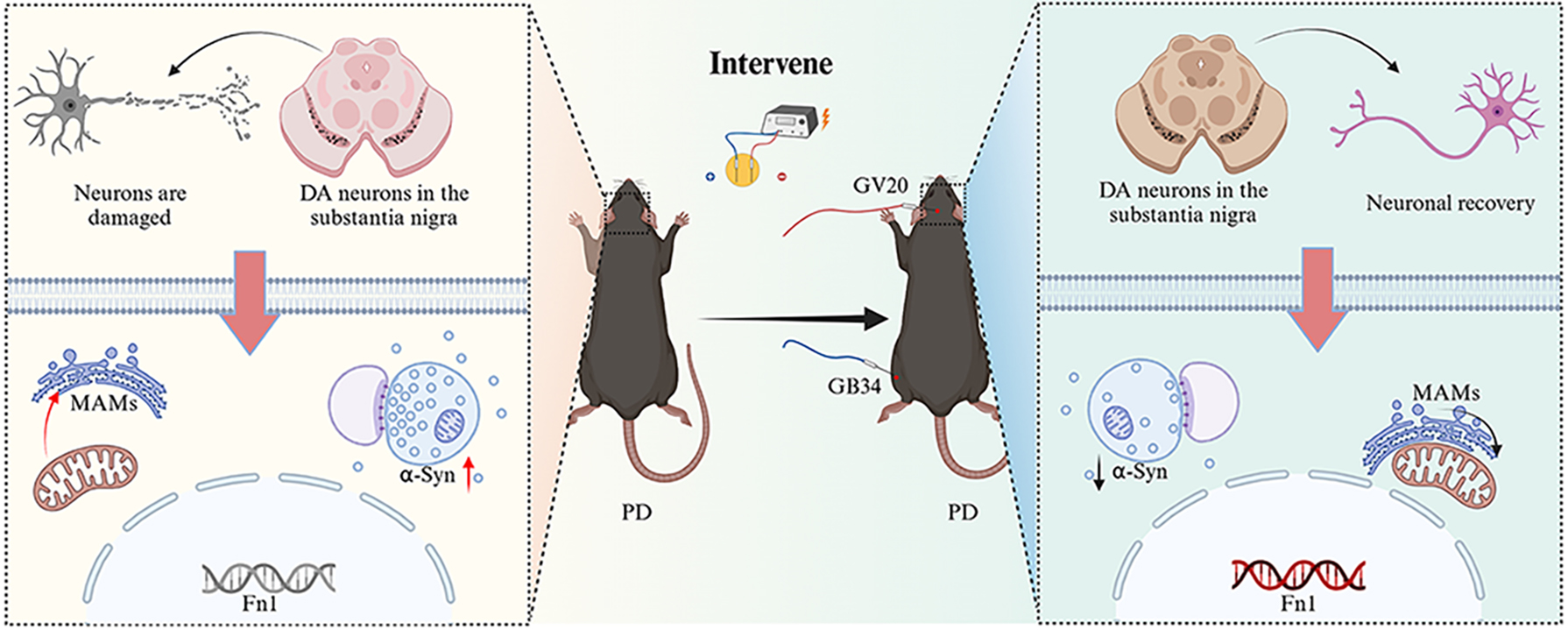

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by dopaminergic neuron degeneration and disruption to mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAMs). This study explores whether electroacupuncture (EA) can alleviate 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) induced PD symptoms and investigates the underlying mechanisms using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq).

A PD mouse model was established using MPTP, followed by EA treatment at governing vessel 20 (GV20) and gallbladder meridian 34 (GB34) acupoints, with sham EA treatments as a control. Behavioral assays, immunohistochemistry, and Western blotting assessed neuroprotective effects. MAM integrity was assessed using Western blot, immunofluorescence staining, and transmission electron microscopy. RNA-seq and protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis identified differentially expressed genes which were validated by real-time fluorescence quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

EA treatment improved motor performance, increased substantia nigra (SN) and striatum tyrosine hydroxylase expression, reduced SN alpha-synuclein, and improved SN dopamine neuron MAM structure. Transcriptomic analysis identified 32 MAM-associated genes, of which fibronectin-1 (Fn1) was identified as a key regulator. EA was found to upregulate Fn1 expression, suggesting its involvement in MAM stabilization and neuroprotection.

EA at GV20 and GB34 alleviated motor and neural impairments in a PD mouse model potentially through modulation of Fn1 and its role in MAM-associated pathways.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- electroacupuncture

- Fn1

- mitochondria-associated membranes

- Parkinson’s disease

- RNA sequence analysis

Parkinson’s disease (PD), a widespread degenerative disorder of the central nervous system, is characterized by degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SN), alpha-synuclein (

Acupuncture has become a widely used complementary therapy for the treatment of neurological disorders including PD [7, 8]. Clinical investigations have demonstrated that the concurrent application of electroacupuncture (EA) and medication significantly improves motor symptoms such as myotonia, bradykinesia and resting tremor in patients with PD when compared to medication alone [9, 10]. EA has been shown to inhibit apoptosis, upregulate neurotrophic factors and activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK/ERK) pathways, to promote dopaminergic neuron survivals in PD [11]. EA targeting specific brain regions activates Akt and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), increasing striatal DA phosphatase-interacting protein levels and reducing 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced symptoms [12]. It also upregulates BDNF expression to counteract neurotoxicity and prevent reductions in BDNF and phosphorylated-ERK levels in the striatum (STR) [13]. EA modulates inflammation and brain connectivity, potentially improving PD symptoms through vagal anti-inflammatory activation and enhanced brain function [14]. Acupoints governing vessel 20 (GV20) and gallbladder meridian 34 (GB34) have significant potential to alleviate clinical symptoms of PD [15, 16, 17, 18]. EA in PD model rats has been shown to increase DA levels in STR, inhibit cell apoptosis in the SN and reduce the loss of dopaminergic neurons [19]. Overall, EA improves dopaminergic neuron survival, protecting against neuronal fiber loss in PD [8, 20].

Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAMs) are specialized junctions between the outer mitochondrial membrane and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, facilitating complex interactions between these two organelles [21]. MAMs significantly contribute to PD pathogenesis. The study has shown that after transfection of

This study hypothesizes that EA improves mitochondrial function by acting on MAMS, thereby alleviating dopaminergic neuronal degeneration and slowing the progression of PD. To test this hypothesis, transcriptome analysis of mouse brain tissue was employed to identify MAM-related pathways and key genes regulated by EA. Subsequently, the transcriptomic results were validated using real-time fluorescence quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) to comprehensively clarify the potential therapeutic mechanisms of EA for PD.

Male mice have more consistent physiological and metabolic responses, which helps reduce variability in experimental results [33]. C57BL/6 male mice were used to control for sex variables and improve the consistency and comparability of results. As effect sizes and standard deviations were not readily available directly from the existing literature and were difficult to estimate, the “resource equation method” was used to determine sample sizes [34, 35]. This study was approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Southern Medical University (Approval No. L2021119). Eighty-five eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (20–22 g) from Southern Medical University’s Animal Center (License No. SYXK[Yue]2021-0041) were acclimated for one week in a controlled environment (22

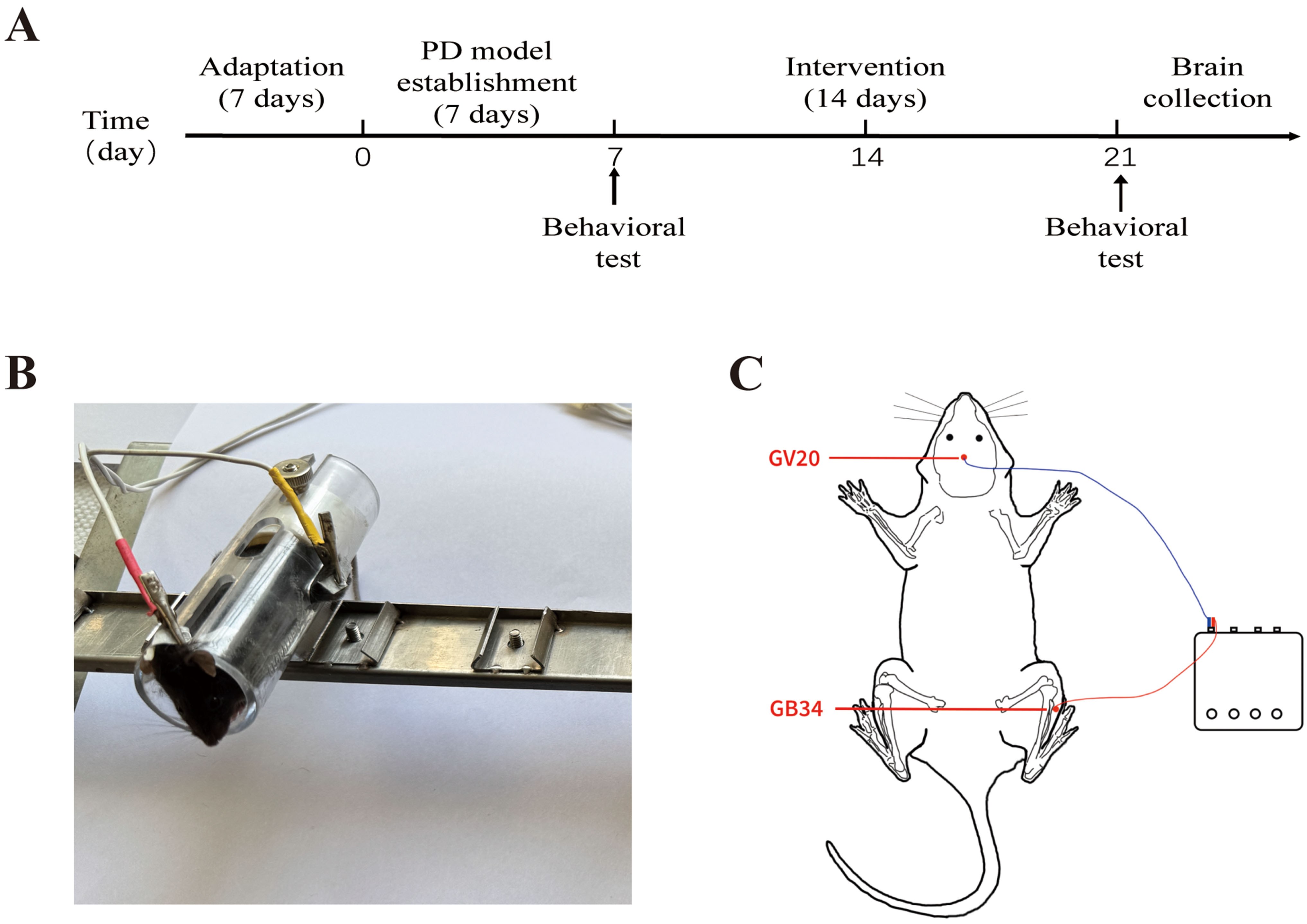

To further investigate EA’s influence on MAMs in the SN, mice were randomly divided into three groups (10 mice/group): control, MPTP and EA groups. Treatment and intervention were consistent with prior protocol, mice were then euthanized and the brain tissues were analyzed by WB, immunofluorescence, transcriptome analysis and RT-qPCR. The procedure is given in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Time axis of experimental procedures and positioning of acupoints. (A) Timeline outlining the experimental phases, including adaptation, PD model establishment, intervention, and brain collection, with behavioral tests scheduled at key time-points. (B) Photograph showing the setup of a mouse undergoing electroacupuncture treatment. (C) Schematic diagram depicting the selected electroacupuncture acupoints in a mouse: GV20 (middle of the parietal bone) and GB34 (lateral calf, in the depression below the anterior aspect of the fibular head). PD, Parkinson’s disease; GV20, governing vessel 20; GB34, gallbladder meridian 34.

EA treatment was conducted at the GV20 (middle of the parietal bone) and GB34 (lateral calf, in the depression below the anterior aspect of the fibular head) acupoints for 20 minutes daily following the induction of MPTP (Fig. 1B,C). GB34 on both sides was alternated daily. Acupuncture needles (0.16 mm

The drug group received levodopa (D9628, Sigma-Aldrich, dissolved in normal saline) and benserazide (B7283, Sigma-Aldrich, dissolved in normal saline) via intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 20 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg, respectively, once daily for 14 consecutive days.

Before the experiment, animals were acclimatized for 12 hours, after which various behavioral tests were conducted, with an inter-test interval of one hour. Mice were placed on a wooden ball atop the pole-climbing apparatus (diameter 8 mm, height 50 cm). Timing started following stabilization. Key points: (T1) Center of mass crosses ball-pole junction, (T2) Reaches pole midpoint, (T3) Forelimbs touch ground. Scoring for each stage of the pole climbing test was determined based on the duration: three points awarded for 1–3 s, two points for 3–6 s and one point for exceeding 6 s or inability to maintain grip on the apparatus [38]. The entire test was repeated three times and mean values were calculated.

The Rotarod fatigue tester (JB-6C, Huai Bei 900 Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., Huaibei, Anhui, China) was set with parameters: Initial speed of four rpm, final speed 40 rpm, accelerated uniformly over five minutes [39]. Mice were placed on the Rotarod with their heads facing inward. The acceleration program of the Rotarod was initiated and an infrared detection device with software was used to record the latency time from the start to the fall of the mouse (each mouse was tested three times and the average value was taken).

A custom wooden frame (length 50 cm, height 39 cm) with platforms at either end and a center steel wire (length 50 cm, diameter approximately 2 mm) supported the mouse’s limbs for a 30 s test. Scoring: Falling 0, both forelimbs gripping 1, all four limbs gripping 2, wrapping tail and limbs 3, attempting to climb but failing 4, successful climb 5. Each mouse was tested three times, averaging scores. Tests were separated by 20 minutes to reduce fatigue [40].

The apparatus (black plastic 40

Bilateral SN of four mice in each group were homogenized in lysis buffer prepared with a protein extraction kit (KGB5303-100, Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, Jiangsu, China), followed by centrifugation and collection of supernatant. Protein concentration was measured using a Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay Kit (P0009, Shanghai Beyotime Biological Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Total lysates were denatured in sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample loading buffer (NA0007, Beijing Leagene Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) at 95 °C for eight minutes. 20 µg of protein were separated on 6%–12.5% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (ISEQ00010, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 for two hours at room temperature, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-IP3R (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; sc-377518), anti-Mfn2 (1:10,000; Proteintech, Wuhan, Hubei, China; 12186-1-AP), anti-VAPB (1:6000; Proteintech, 14477-1-AP), anti-TH (1:5000; Proteintech, 25859-1-AP), anti-

One hemisphere was separated and immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, paraffin-embedded and sectioned into 6-µm-thick slices. Immunohistochemistry was performed following kit instructions (PV-9000, Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Brain sections underwent xylene deparaffinization and ethanol solutions (from 100% to 75%) and were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling sections in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) in a microwave oven for 15 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase blocking reagent was added dropwise to each section and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with the primary antibodies: anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (1:5000; Proteintech, 25859-1-AP) and anti-

Brains were perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde, fixing the entire organ. Post-fixation, hemispheres were separated, and one hemisphere was processed for immunofluorescence and sliced into 20-micron frozen sections. These sections were immersed in Frozen Sections Antigen Repair Agent (P0090, Shanghai Beyotime Biological Co., Ltd.), followed by three washes and incubation in 0.3% Triton X-100 (T9284, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes. After washing with PBS, sections were blocked with PBS solution containing 5% goat serum (16210064, Gibco, New York, NY, USA) for 30 minutes. Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C: anti-translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOM20) (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; SC-17764) and anti-calreticulin (1:500; Proteintech,10292-1-AP). After washing,slices were dark incubated for two hours with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488-conjugate IgG (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; ab150077) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647-conjugate IgG (1:500; Abcam, ab150115). Finally, slices were mounted using Fluoroshield with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (F6057, Sigma-Aldrich) and imaged using a Leica BX53 fluorescent microscope.

The SN tissue on one side of three mice in each group was taken as a sample and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde overnight. Samples were then rinsed in buffer, post-fixed in 1.0% osmium tetroxide for one hour, rinsed again, and dehydrated through graded ethanol series. After resin embedding, the samples were made into ultrathin sections. These sections were viewed on a TEM (H-7500, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

The SN tissue from the remaining side of three mice in each group was used for transcriptomic analysis. Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) performed all transcriptomic procedures—including RNA purification, reverse transcription, library preparation (TruSeqTM RNA Kit, Illumina; 1 µg total RNA), and Illumina platform sequencing—according to the Illumina’s instructions (San Diego, CA, USA). Principal component analysis of gene expression profiles was performed using the platform (https://www.majorbio.com). The DEseq2 algorithm based on the platform was used to identify DEGs among the control, MPTP and EA groups. The fold change threshold was set at

Total RNA from the SN of four mice in each group was extracted using TRIzol reagent (15596026CN, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A BioTek spectrophotometer was used to detect the concentration and purity of RNA, which was then diluted in a proportion appropriate to make a final concentration of 1000 ng/µL. The Evo M-MLV Reverse Transcription Kit (AG11705, Accurate Biotechnology, Changsha, Hunan, China) was used to synthesize cDNA by reverse transcription of total RNA. The target gene expression levels were determined with a synergetic binding reagent (SYBR) RT-PCR kit (AG11739, Accurate Biotechnology, Changsha, Hunan, China). RT-qPCR was performed using a Roche LightCycler 96. Primers were procured from TSINGKE (Beijing, China) and the sequences are shown in Table 1. GAPDH was considered as the housekeeping gene to normalize the expression levels of targeted genes, three parallel holes were set for every sample and the relative expression of genes was analyzed according to the 2-ΔΔCt method.

| Targeted genes | Forward and reverse primers |

| Myocilin (Myoc) | CAGGGAAGTCTCTCAGTGGAATT (F) |

| GGTCTCTCATCCACACTCCATAC (R) | |

| Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (Pcsk9) | TATGACCTCTTCCCTGGCTTCTT (F) |

| GGATAATTCGCTCCAGGTTCCAT (R) | |

| Fibronectin 1 (Fn1) | TGAGCGAGGAGGGAGATGAA (F) |

| TAGGTGCCTGGGGTCTACTC (R) | |

| Cubilin (Cubn) | TCTGGCATCTTGGAGAGCATAAA (F) |

| TTTCTCCACAGTAGCGTCCTATC (R) | |

| Integrin Alpha 5 (Itga5) | GCTGGACTGTGGTGAAGACAATA (F) |

| AATGTCAGGTTCAGTGCGTTCTT (R) | |

| Dopamine Receptor D1 (Drd1) | AGGTTGAGCAGGACATACGC (F) |

| TTGCTTCTGGGCAATCCTGT (R) | |

| Adenosine A2a Receptor (Adora2a) | TCACGCAGAGTTCCATCTTCAG (F) |

| AGGTCTTTGTGGAGTTCTCATCTT (R) | |

| Cluster of Differentiation 4 (Cd4) | CCTGACCTTGGATAGCAACTCTAA (F) |

| CGCTGACTCTCCCTCACTCTTAT (R) | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGACTG (F) |

| ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG (R) |

To analyze data, the average of several groups of data was calculated and outliers with scores greater than 1.5 interquartile ranges from the first and third quartiles of the data distribution were eliminated. Additionally, after excluding outliers, to ensure consistency in the number of animals per group, an equal number of animals were randomly selected from each group for evaluation. Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Data are reported as mean

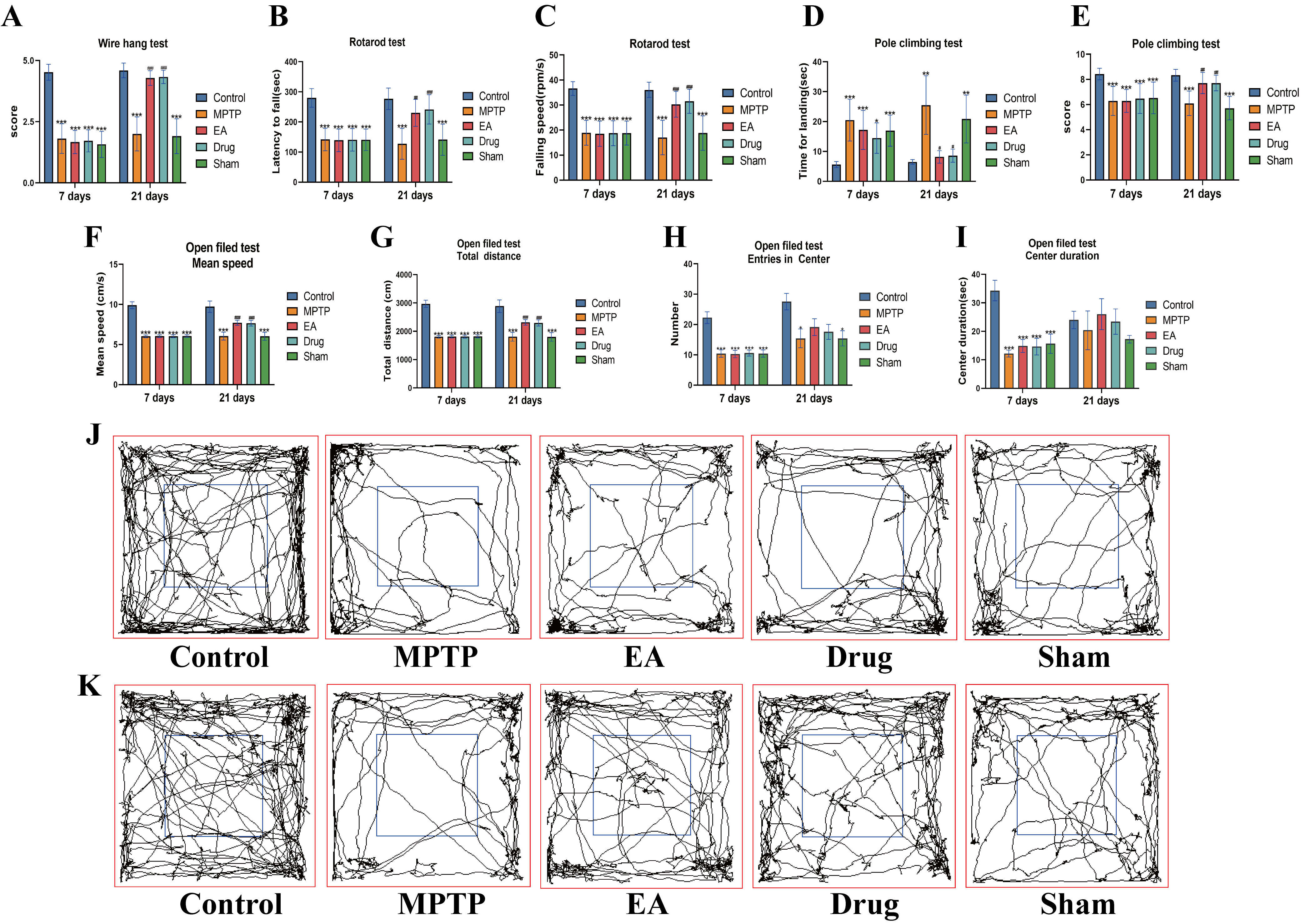

To determine whether EA can increase motor function in the MPTP model, pole climbing, rotarod, wire hang and open field tests were performed. Following successful establishment of the PD mouse model on day seven, behavioral assessments revealed that MPTP-treated mice exhibited significant motor impairments across all tests (Fig. 2), confirming the successful replication of Parkinsonian motor dysfunction characteristics and providing a reliable model for subsequent intervention studies. Moreover, there were no statistical differences between the treatment groups, which excludes the interference of factors on the results that may have existed prior to the implementation of the intervention, thus avoiding false-positive results post-intervention. After 14 days of counterpart interventions, one-way ANOVA showed significant differences among the groups in the behavioral tests. In the pole climbing test, the total landing time of the MPTP group mice was significantly prolonged (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Behavioral analysis. (A) Time to landing in the pole climbing test (Day 7 F = 7.645, p

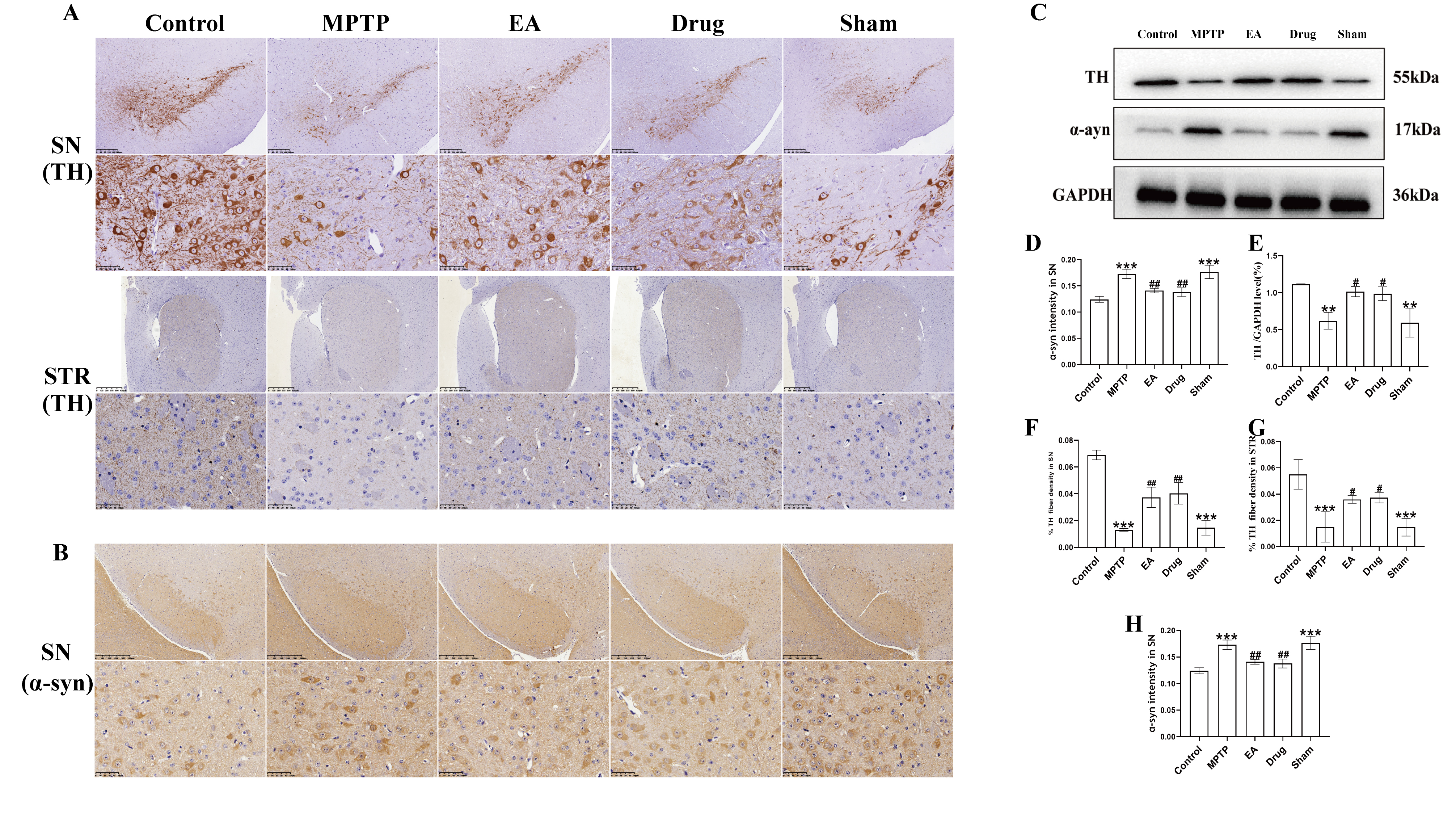

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. EA ameliorated neuropathological alterations produced by MPTP in PD mice. (A) Representative immunohistochemistry analysis of TH for SN and STR. Magnifications of

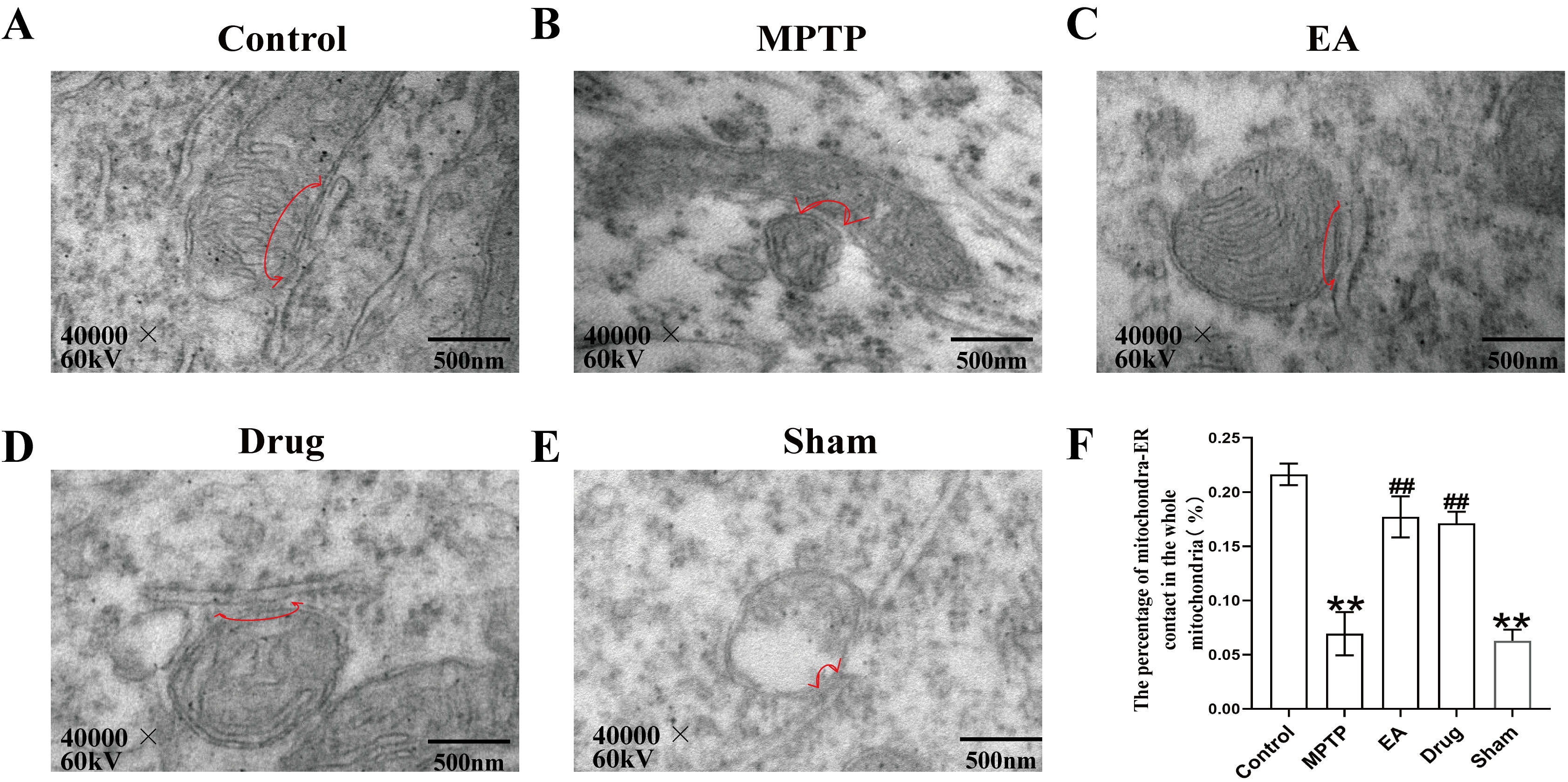

MAMs in the SN were observed through TEM. As shown in Fig. 4, compared with controls MAMs in the MPTP and sham groups were loose, with significant distance between mitochondria and ER, reducing the percentage of mitochondrial-ER contact in the whole mitochondria (p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Results of endoplasmic reticulum membranes in the SN in each group of mice were observed under transmission electron microscope. (A–E) Representative transmission electron micrographs for each group, the arrowheads with loops show regions of association. (F) The percentage of the mitochondria surface closely apposed to endoplasmic reticulum (defined as

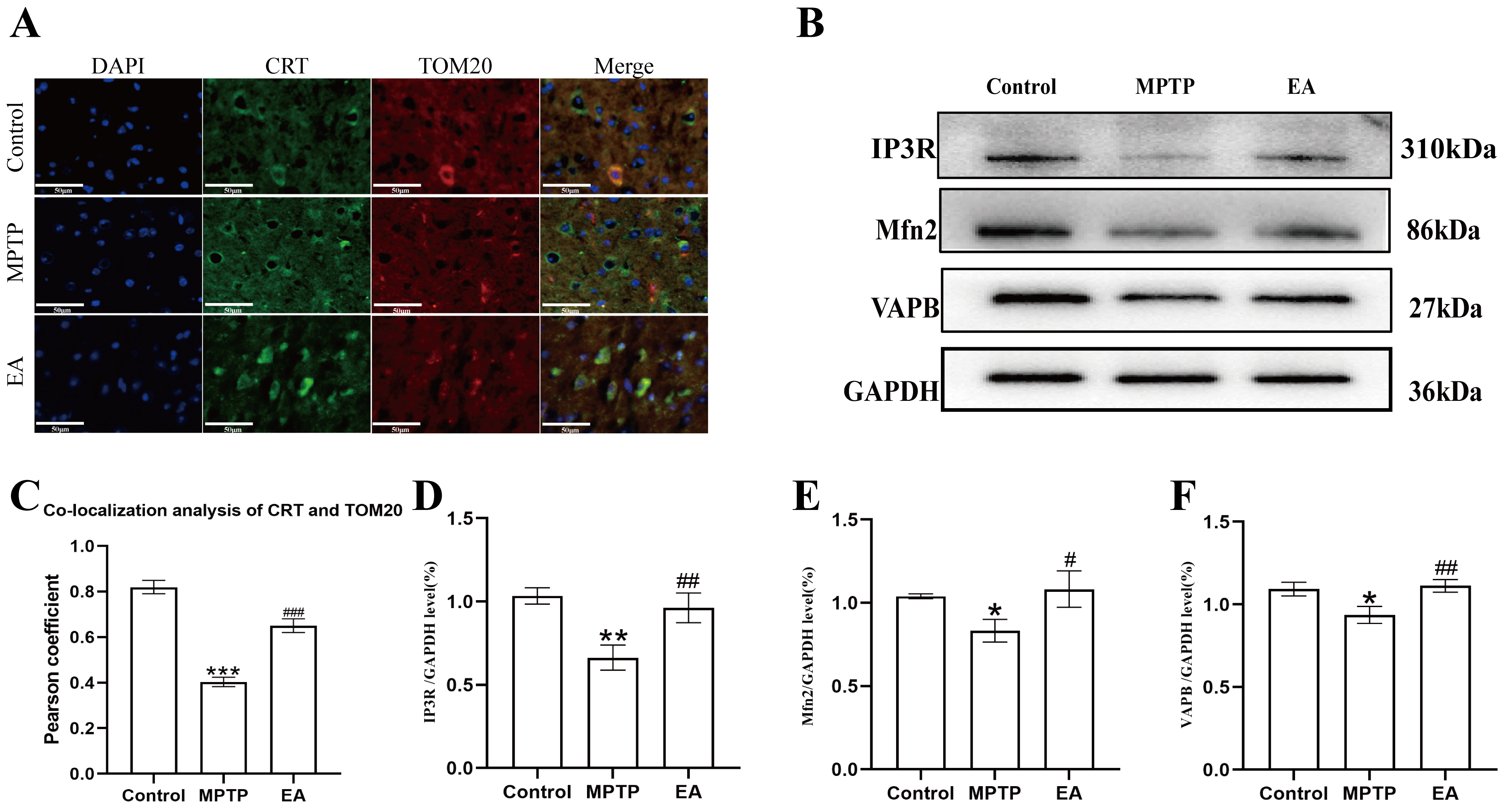

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Effect of EA on MPTP-induced changes of MAMs in PD mice. (A) Co-localization of ER and mitochondria in each group of substantia nigra neurons detected by immunofluorescence. DAPI marks the nucleus blue. TOM20 stains the mitochondria red. CRT marks the endoplasmic reticulum, shown as green. The overlapping area of TOM20 and CRT represents the MAMs (magnification,

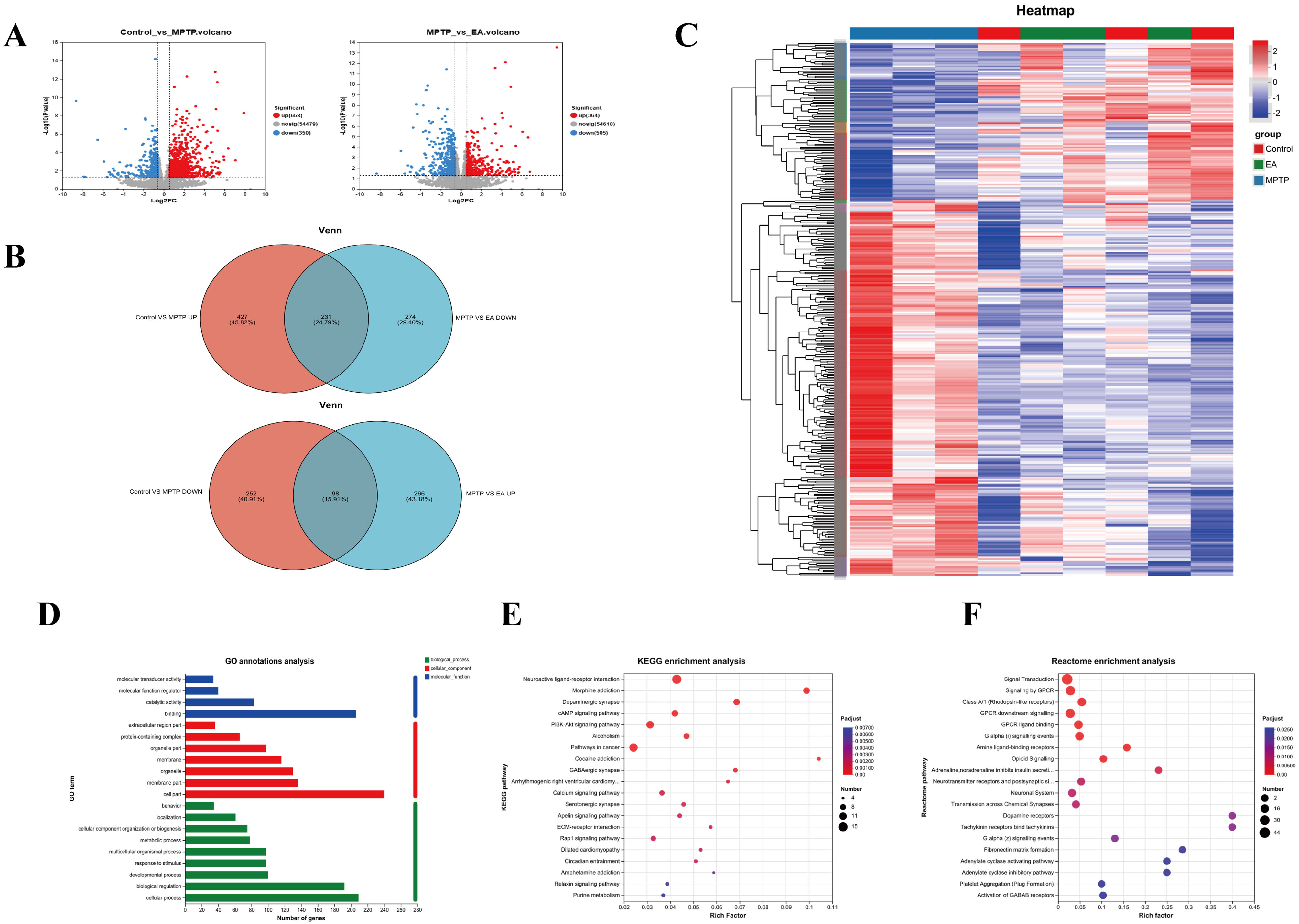

To explore EA’s mechanism in PD, gene expression profiling was completed for different groups. A volcano map revealed 1008 DEGs in the MPTP vs. control (658 up, 350 down). Between the MPTP and EA groups, 869 DEGs were identified (364 up, 505 down). Heat maps visualized expression patterns of up-regulated and down-regulated genes for the control, MPTP and EA groups. As Fig. 6A shows, red and blue colors respectively illustrate higher and lower expression of genes. DEGs overlaps were then analyzed with Venn diagrams (Fig. 6B). EA downregulated 231 of the 658 up-regulated DEGs and upregulated 98 of the 350 down-regulated DEGs in the MPTP group. The 329 DEGs may be key EA targets against PD, as shown in the heat map (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Analysis of mice transcriptome samples. (A) Volcano plot for (

To investigate the function of the DEGs, GO classification, KEGG and Reactome annotations, analysis and enrichment analyses were performed. Following the GO database, three different ontologies were used to annotate the genes, including biological process (BP), cellular component (CC) and molecular function (MF). In GO BP terms, the DEGs were mostly enriched in catalytic activity and binding. The DEGs were mostly enriched in cell and membrane part categories according to their CC classification. MF DEGs were mostly enriched in cellular processes and biological regulation (Fig. 6D). To identify key pathways modulated by EA in PD, we analyzed DEGs via KEGG pathway enrichment. KEGG pathway analysis revealed EA modulation of the first three pathways: neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions, morphine addiction and dopaminergic synapses (Fig. 6E). Reactome analysis showed EA modulation of signaling, G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling and downstream GPCR signaling (Fig. 6F).

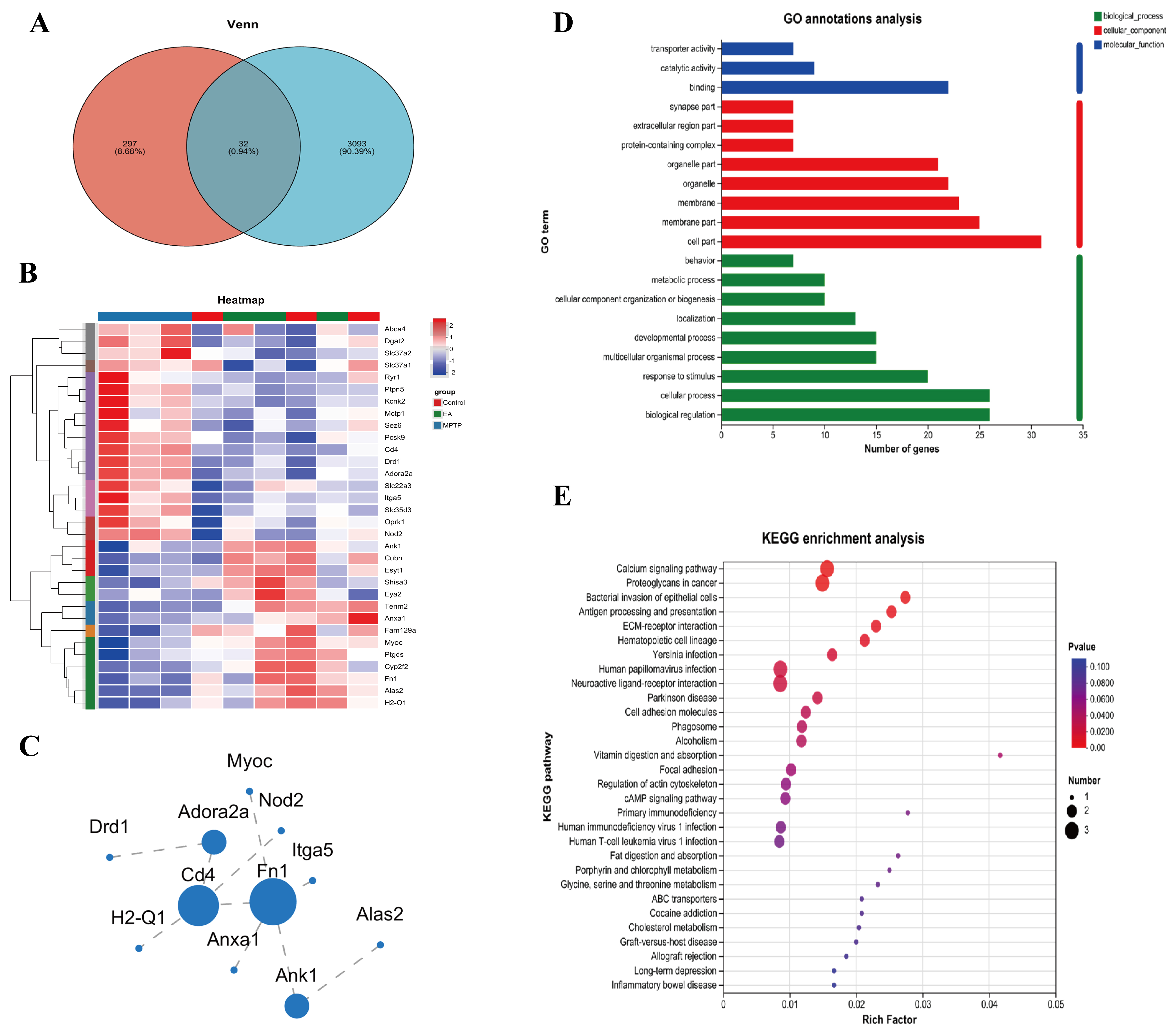

To explore the mechanism of EA regulation of MAMs in depth, a Venn diagram analysis was performed of 329 genes potentially regulated by EA with genes that are known to be associated with the regulation of MAMs in the GO database. 32 candidate genes most likely to be key players in the regulation of MAMs function and activity were screened by electroacupuncture (Fig. 7A). To visualize the specific changes of these genes in different experimental groups, heat maps were created to clearly show their expression differences (Fig. 7B). These DEGs were analyzed for GO and KEGG pathway enrichment to further reveal the mechanism of EA regulation of MAMs. The MF were mainly enriched in biological regulation, cellular process, and response to stimulus; the CC was enriched in cell part, membrane part and membrane, the BP was primarily enriched in binding, catalytic activity and transporter activity (Fig. 7D). Pathway analysis showed that the MAMs pathways were inhibited, such as calcium signaling pathway, cAMP signaling pathway and ECM-receptor interaction pathway (Fig. 7E). A protein-protein interaction network was constructed using the STRING database (Fig. 7C). These findings provide further evidence that fibronectin-1 (Fn1) is strongly associated with MAMs. The results indicated that EA may influence MAMs by enhancing the expression of Fn1, thereby providing a potential treatment for PD.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. MAMs-related transcriptomic analysis. DEGs: (A) Venn diagram; (B) Heat map; (C) Protein-protein interaction analysis; (D) GO functional annotation classification; (E) KEGG enrichment analysis.

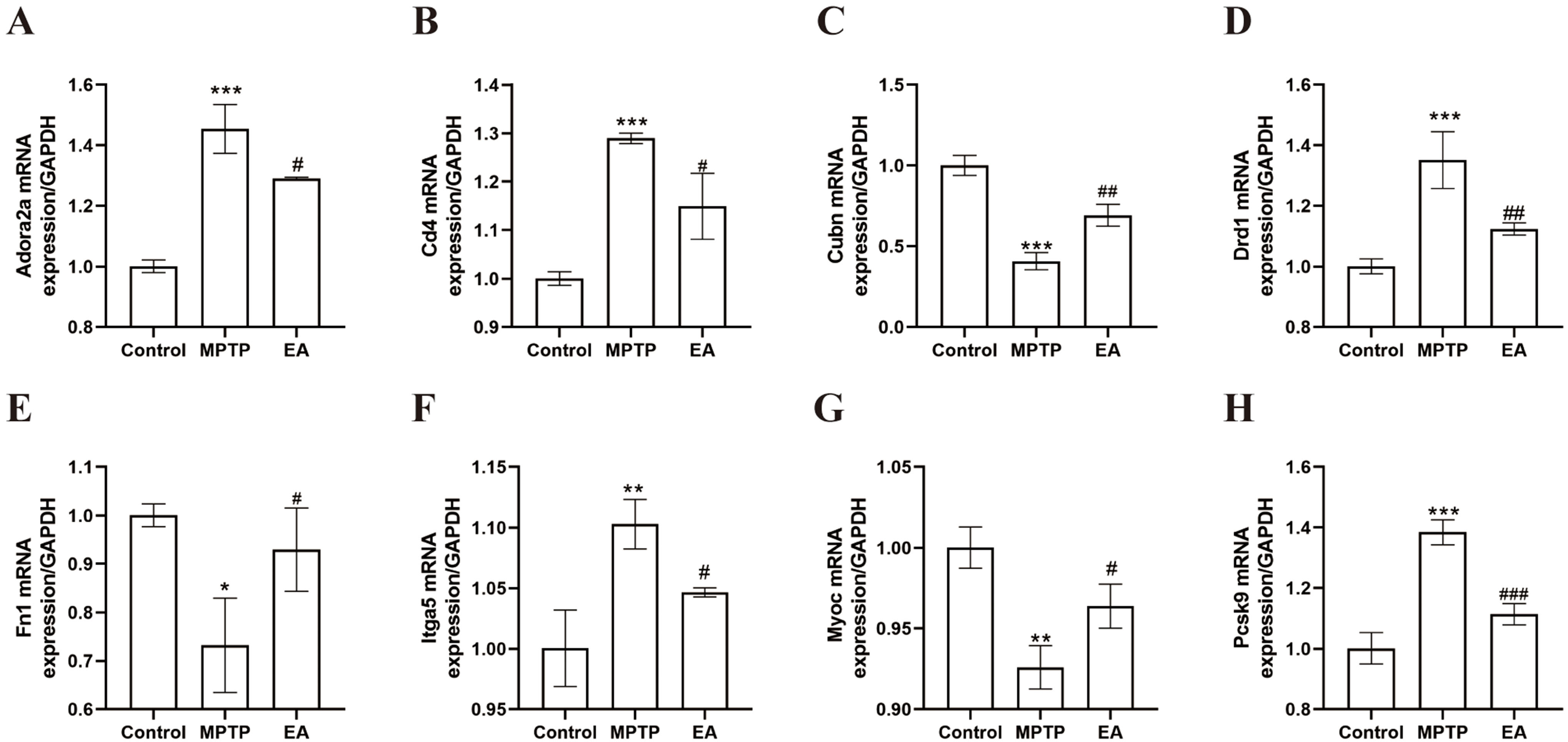

To validate RNA-Seq data reliability, we examined eight DEGs: adenosine a2a receptor (Adora2a), cluster of differentiation 4 (Cd4), cubilin (Cubn), dopamine receptor d1 (Drd1), fibronectin 1 (Fn1), integrin alpha 5 (Itga5), myocilin (Myoc) and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (Pcsk9). Their expression trends (Fig. 8) matched RNA-Seq profiles. Three genes (Cubn, Fn1 and Myoc) were downregulated in the MPTP group (Fig. 8C,E,G) but upregulated by EA. Conversely, five genes (Adora2a, Cd4, Drd1, Itga5 and Pcsk9) were upregulated in the MPTP group but downregulated by EA (Fig. 8A,B,D,F,H).

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Confirmation of RNA sequencing results by real-time fluorescence quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). (A) Adora2a (F = 68.08, p

A PD model induced by MPTP compounds is one of the most commonly used disease models for PD [48]. After seven days of MPTP injection, all experimental mice except the control showed significant impairment in wire hanging, rotarod, climbing and open field tests, confirming successful model establishment. In contrast, the EA and drug groups exhibited significant recovery, while the sham EA group did not. These behavioral results suggest that EA at GV20 and GB34 effectively enhances motor coordination, balance, limb strength and overall motor function in mice with PD with effects comparable to those of positive drugs.

Given that motor function recovery likely reflects neuronal protection, next investigation was dopaminergic neuron integrity. TH plays a key role in regulating DA biosynthesis and TH-positive neurons may represent dopaminergic neurons [49]. According to the results of immunohistochemistry (IHC) and WB experiments, the optical density of TH in the STR and SN, which had been reduced in the MPTP group, was notably increased following EA, Meanwhile, the accumulation of pathological protein

To explore the mechanism of EA, its effect on MAMs was examined. TEM showed loose mitochondrial-ER coupling and reduced coupling areas in the MPTP group, which were enhanced by EA. TOM20 and CRT immunofluorescence co-staining results further supported these findings, indicating that EA may enhance neuroprotection by promoting mitochondrial-ER coupling. This may be linked to the recovery of the expression of MAMs-related proteins such as IP3R, Mfn2 and VAPB. WB results showed that the expression levels of IP3R, Mfn2 and VAPB showed a decreasing trend in the MPTP-induced mouse model of PD and EA was shown to be effective in ameliorating this pathology. These proteins play pivotal roles in MAMs. Mfn2, a regulator of mitochondrial fusion, not only establishes physical connections between the ER and mitochondria but also regulates Ca2+ transfer [50]. The absence of Mfn2 has been shown to reduce mitochondrial-ER connectivity and Ca2+ uptake [51]. IP3R facilitates the mitochondrial-ER coupling by forming complexes with glucose-regulated protein 75 kDa (GRP75) and voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), thereby enhancing mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and ATP production [27]. Meanwhile, VAPB, in conjunction with phosphatase-interacting protein 51, regulates the transfer of Ca2+ between the ER and mitochondria and disruption of this interaction leads to the dissociation of MAMs and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction [52]. Therefore, the restoration of these proteins by EA likely underpins the observed improvement in MAMs structure. Further mechanistic studies may focus on Ca2+ signaling and ATP synthesis in MAMs [53, 54].

To further elucidate the molecular pathways involved in EA modulation of MAMs, RNA-Seq analysis showed significant regulation by EA in PD mice. When compared to controls, 1008 DEGs were identified in the MPTP group and EA altered 869 genes. Venn diagram analysis revealed reversal of 231 upregulated and 98 downregulated genes, suggesting key targets. Further analysis revealed that EA modulated 32 MAMs-related genes. GO analysis indicated involvement in biological regulation, cellular processes and response to stimuli, while KEGG pathway enrichment linked these genes to MAM-associated pathways, including calcium and cAMP signaling and extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions. EA reversed the suppression of these pathways in PD, suggesting a role in delaying PD progression. These results add another layer of support to the claim that EA, by modulating MAMs, improves calcium signaling, optimizes the intracellular environment and in turn, has a beneficial effect on PD. The RT-qPCR validation of Adora2a, Cd4, Cubn, Drd1, Fn1, Itga5, Myoc and Pcsk9 exhibited concordance with the RNA-Seq data, providing further evidence of EA’s modulatory impact.

Concurrently, through a comprehensive examination of the protein network interactions of DEGs, Fn1 was identified as a core gene regulated by EA. Based on these findings, it is plausible to hypothesize that EA at GV20 and GB34 is likely to exert its therapeutic effect on PD by modulating the expression of Fn1, which in turn affects MAMs. Fn1, as a large glycoprotein, is a crucial component of the ECM and plays a key role in cell adhesion and migration processes [55]. Fn1 is closely related to the ECM-receptor interaction signaling pathway involved in various cancer-related processes [56]. The present study observed a significant enrichment of Fn1 in the ECM-receptor interaction pathway, providing evidence to support the hypothesis that EA may mediate this pathway through Fn1, thereby exerting its biological effects. Specifically, the interaction of Fn1 with integrins activates Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) and Steroid receptor coactivator (Src) family kinases [57], thereby triggering a series of complex signaling cascades that potentially impact the structure and material exchange between the mitochondria and ER. In PD, decreased FAK levels may impair the autophagic response to ER stress, leading to its persistence and exacerbation. This aggravation may further lead to the loosening of the MAMs structure, which hinders the essential material exchange and signaling between the ER and mitochondria. This, in turn, disrupts cellular homeostasis and accelerates PD progression [58]. Furthermore, Fn1 deficiency may negatively impact mitochondrial function by inhibiting the FAK/STAT3 pathway, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction, loss of membrane potential and increased reactive oxygen species production. This similarly affects the material exchange between mitochondria and the ER within MAMs [59]. Fn1 also interacts with the PI3K-Akt pathway [60], which regulates Ca2+ exchange between the ER and mitochondria by modulating key proteins such as GRP75, IP3R and VDAC [61]. Previous study has shown that inhibiting the PI3K/Akt pathway leads to structural damage to MAMs [62]. Additionally, downregulation of the Fn1 gene leads to decreased expression of Bcl-2 protein and increased expression of Bax protein [63]. Anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 are typically located on the mitochondrial membrane, where they influence the function and stability of mitochondria [64]. This may indirectly affect the structure and function of MAMs. On the basis of such evidence, it is hypothesized here that EA may regulate the interaction between Fn1 and integrins by up-regulating the expression or enhancing the activity of Fn1. This regulatory process subsequently affects the activation of FAK and Src family kinases and ultimately influences the structure and function of MAMs through related signaling pathways. Additionally, EA may indirectly modulate Fn1’s role in MAMs by regulating the FAK/STAT3 and PI3K-Akt pathways. Therefore, future studies should further explore the specific mechanisms by which EA therapies modulate the effects of Fn1 on MAMs, providing new insights and approaches for advancing this field.

This study reveals a novel mechanism by which EA may exert its neuroprotective effects in ameliorating PD symptoms by enhancing MAMs structure and function, potentially through the restoration of key MAMs proteins (IP3R, Mfn2 and VAPB) and the modulation of critical pathways involving genes like Fn1. Future studies should further explore how EA can fulfill its potential in the treatment of PD by modulating these MAMs-related proteins and their mediated Ca2+ signaling and energy metabolism processes, with a specific focus on validating the Fn1-MAMs axis.

However, this study has several limitations. While RNA-Seq showed effects on multiple genes and pathways and identified Fn1 as a key EA-regulated gene that influences MAMs, the specific underlying mechanisms require further validation. To further elucidate these mechanisms, it is planned to develop a CRISPR-dCas9 activation/repression system to specifically regulate Fn1 expression in the SN pars compacta. This approach will be combined with AAV-mediated MAMs reporter viruses to dynamically dissect the functional axis of Fn1-MAMs. Additionally, the exploration of MAMs in the present study focused primarily on structure and protein composition, while the effects of Ca2+ dynamics (e.g., IP3R-GRP75-VDAC1 flux) and ATP production following changes in MAMs have not been studied in detail. Future research will employ live-cell imaging techniques to dynamically monitor Ca2+ oscillations and ATP production rates. Meanwhile, focus will be on the regulation of Fn1 expression and activity by EA therapy and its effect on Fn1-integrin interactions. The central goal is to elucidate how EA regulates Fn1 binding to integrins at the molecular level and how this regulation further affects the structure and function of MAMs. There were some limitations in the experimental design of this study and the unfinished experimental elements included MAMs-associated immunofluorescence co-localization analyses, WB assays and transcriptomics analyses in the sham and drug groups, which may affect comprehensive assessment of the effects of EA and drug interventions on the structure and function of MAMs, as well as in-depth understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of related gene expression. The small sample size is a limitation of the current study, which may hinder a comprehensive assessment of the combined effects of EA in PD. Also, a focus on midbrain dopaminergic neurons may overlook changes in other brain regions. The inability to conduct long-term behavioral assessments also limits the generalizability of findings regarding the sustained impact of EA. Future studies should refine these experimental elements and incorporate multimodal imaging, larger samples and extended durations are required to clarify the comprehensive effects of EA in PD. Single-nucleus sequencing should be integrated with spatial transcriptomics to generate a 3D expression map of MAMs-related genes across the brain following EA intervention. Such studies aim to provide a more robust principled basis for EA as a potential treatment for PD.

EA at GV20 and GB34 alleviates PD motor deficits by restoring MAMs’ integrity. Mechanistically, EA enhances MAMs function via modulating Fn1 to improve neuronal organelle interactions and DA homeostasis. This study first demonstrates EA’s neuroprotection through MAMs’ remodeling, suggesting a multi-target strategy for PD. Targeting Fn1-mediated networks may offer novel therapeutic avenues for neurodegeneration.

The transcriptome assembled for this study are available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive via accession number PRJNA1175895 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=PRJNA1175895).

PL: Data curation, writing – original draft. FW: Conceptualization. ZF: Investigation, data curation. JL: Visualization. QL: Methodology, investigation. XC: Investigation. SH: Investigation. XQ: Investigation. ZZ: Investigation. YH: Conceptualization, writing - review & editing. JZ: Investigation, writing - review & editing, resources, funding acquisition. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was conducted in accordance with the NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals and was approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Southern Medical University (Approval No. L2021119).

Not applicable.

This research was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2021A1515011518); Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (202102080301); National Natural Science Foundation of China (82305365).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/JIN40105.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.