1 Department of Pharmacology, School of Pharmaceutical Science, Ohu University, 963-8041 Koriyama, Fukushima, Japan

2 Department of Cellular Pathology, Institute for Developmental Research, Aichi Developmental Disability Center, 480-0392 Kasugai, Aichi, Japan

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) has been implicated in the formation of false contextual fear memory. Here, we examined the involvement of glucocorticoid (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) in this process.

Adult male C57BL/6J mice were exposed to Context B, similar but distinct from Context A, 3 h (B-3 h) after electric foot shock (FS) in Context A, and re-exposed to Context B either 24 h (B-24 h) or 9 days (B-9 d) after FS in Context A. To assess the effect of B-3 h exposure on the specificity of original memory, freezing levels were also measured in Context A (A-24 h or A-9 d) in a separate group, following the B-3 h exposure after FS. GR and MR protein levels in the hippocampal nuclear fractions were analyzed by western blotting. In pharmacological studies, dexamethasone (a GR agonist), fludrocortisone (an MR agonist), and mifepristone (a GR antagonist) were subcutaneously administered to hypothalamic CRF knockdown mice.

When mice were exposed to B-3 h after FS, they exhibited increased freezing at B-24 h compared with B-3 h and showed further increases at B-9 d compared with B-24 h, indicating a time-dependent intensification of false contextual fear memory. In contrast, freezing behavior in Context A was reduced at A-24 h and A-9 d after B-3 h exposure compared with mice that were not exposed to B-3 h, suggesting diminished precision of the original memory. Immunoblotting revealed increased nuclear GR levels at B-3 h and decreased MR levels at B-24 h and B-9 d. In CRF knockdown mice, dexamethasone enhanced freezing at B-3 h, whereas fludrocortisone reduced freezing at B-24 h and B-9 d. Co-administration of mifepristone and fludrocortisone suppressed both the formation of false memory at B-3 h and its subsequent enhancement. However, this treatment increased freezing in Context A at A-24 h and A-9 d following B-3 h exposure.

Exposure to a similar but distinct context shortly after FS induces false contextual fear memory via GR activation and promotes its time-dependent potentiation through MR inactivation. Such early exposure may also impair the specificity of the original fear memory.

Keywords

- false context fear memory

- glucocorticoid receptor

- mineralocorticoid receptor

- time-dependent false memory potentiation

- fear memories less precise

Fear-related traumatic events often occur abruptly, providing little opportunity to process the situation or comprehend the context. Consequently, individuals affected may retain fragmented memories that are devoid of contextual information [1]. It has been suggested that fear memories may contain information about events that either never occurred or occurred differently from how they are remembered [2]. A study using mice indicated that false memories—resulting from the rapid degradation of experienced fear memories—can form within 3 h after fear exposure [3] and that memory reconsolidation following retrieval requires the synthesis of fear-related proteins in the amygdala within 6 h [4]. In our previous study using mice, we demonstrated that a fear response could be observed in a context different from the one in which the mice had experienced an electric foot shock (FS) as a conditioning stimulus [5]. Specifically, mice exposed to Context B—a similar but novel environment—3 hours after conditioning in Context A, where the FS had been administered, exhibited a freezing response upon re-exposure to Context B 24 hours later, despite never having received shocks there. Importantly, the freezing time in Context B at 3 hours after conditioning was significantly higher in mice that had received FS in Context A compared to mice that had not. These findings indicate that the observed freezing behavior in Context B reflects the formation of a false contextual fear memory—defined as the expression of fear in a neutral context due to temporal proximity of contexts during memory consolidation—rather than a simple response to novelty [5]. This fear response was further potentiated when the mice were re-exposed to Context B 24 h after the FS [5]. However, if the mice were not exposed to Context B 3 h after Context A, the fear response at 24 h during their first exposure to Context B was significantly less intense. Therefore, we hypothesized that the potentiated false contextual fear response observed in Context B 24 h after the FS in Context A—when the mice had been exposed to Context B within a narrow time window of 3 h after Context A—may result from a memory confusion regarding whether the FS had occurred in Context A or Context B. Moreover, we found that the overexpression of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) facilitates the formation of false context fear memories, and the knockdown (KD) of hypothalamic CRF potentiates a fear response due to the fear contextual memory [5]. However, the role of CRF in the formation and potentiation of false context fear memory remains unclear.

Following a traumatic experience, the secretion of cortisol in humans or corticosterone in rodents increases, which in turn inhibits the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and reduces CRF production in the hypothalamus [6]. HPA axis activation supports the formation of false context fear memories [5]. CRF secretion and HPA axis activation might support the formation of a false memory, typically occurring within 3 h after a fear exposure [3]. Glucocorticoid receptor (GR) activation in the hippocampus may contribute to the formation of false fear memories [7]. A corticosterone injection into the dorsal and ventral hippocampus via GR activation impairs the reconsolidation of fear memories in a time-dependent manner in rats [8]. GR activation in the hippocampus after an excessive fear experience suggests it interferes with the original fear memory and forms a false fear memory by impairing memory reconsolidation. On the other hand, mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) activation disrupts the overconsolidation of aversive memories [9], and its overexpression confers resilience to the effects of chronic stress on hippocampus-dependent functioning and structural plasticity [10]. Taken together, we hypothesized that GR activation and MR inactivation after excessive fear experience might have critical roles in the formation of the false fear memory [7, 11, 12]. It follows, then, that understanding the roles of GR and MR in the formation of false fear memory is crucial for elucidating the neuronal mechanisms underlying both the formation and potentiation of such memories. The loss of context-specific reactivation patterns in the hippocampal ensemble 9 days after conditioning has been reported as a source of fear memory generalization [13]. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the expression patterns of GR and MR in the hippocampus, as well as their roles in the formation and potentiation of false context fear memory at 3 h, 24 h, and 9 days after fear exposure in mice, to elucidate the underlying neurobiological mechanisms.

We purchased adult male C57BL/6J mice, aged 6–7 weeks, from Charles River Laboratories (Yokohama, Japan) and CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan). All mice were allowed 1 week of acclimation to the housing facilities before being randomly assigned to experimental groups. The mice were housed under a controlled environment (25

Dexamethasone 21-phosphate disodium salt (Dex; #D4438) and mifepristone (Mifeprex; #M1732) were obtained from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), and fludrocortisone acetate (FDC; #F6127-1G) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All three compounds were dissolved in corn oil (Cat. No. 23-0320-5-500G-J, Sigma Aldrich, Inc.). For anesthesia, medetomidine hydrochloride (Cat. #135-17473) and butorphanol tartrate (Cat. #021-19001) were obtained from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp. (Osaka, Japan), and midazolam (Cat. #1124401A1060) was obtained from Sandoz Group AG (Basel, Switzerland). These anesthetics were mixed and dissolved in saline. An enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit for corticosterone measurement (#YK240) was purchased from Yanaihara Institute Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). For immunohistochemistry, the following primary antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal anti-green fluorescence protein (GFP) antibody (#M048-3, MBL Life Science, Tokyo, Japan; 1:200); and rabbit polyclonal anti-CRF antibody (#H-019-06, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Burlingame, CA, USA; 1:100). These antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20 (Cat. No. 40350-02, KANTO CHEMICAL CO.,INC., Tokyo, Japan) and 10% donkey serum (Cat. No. D9663-10ML, Sigma Aldrich, Inc.). The following secondary antibodies were used: for detecting GFP and CRF, Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG (H&L) (#ab150105, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:200) and Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H&L) (#ab150106, Abcam; 1:200), respectively.

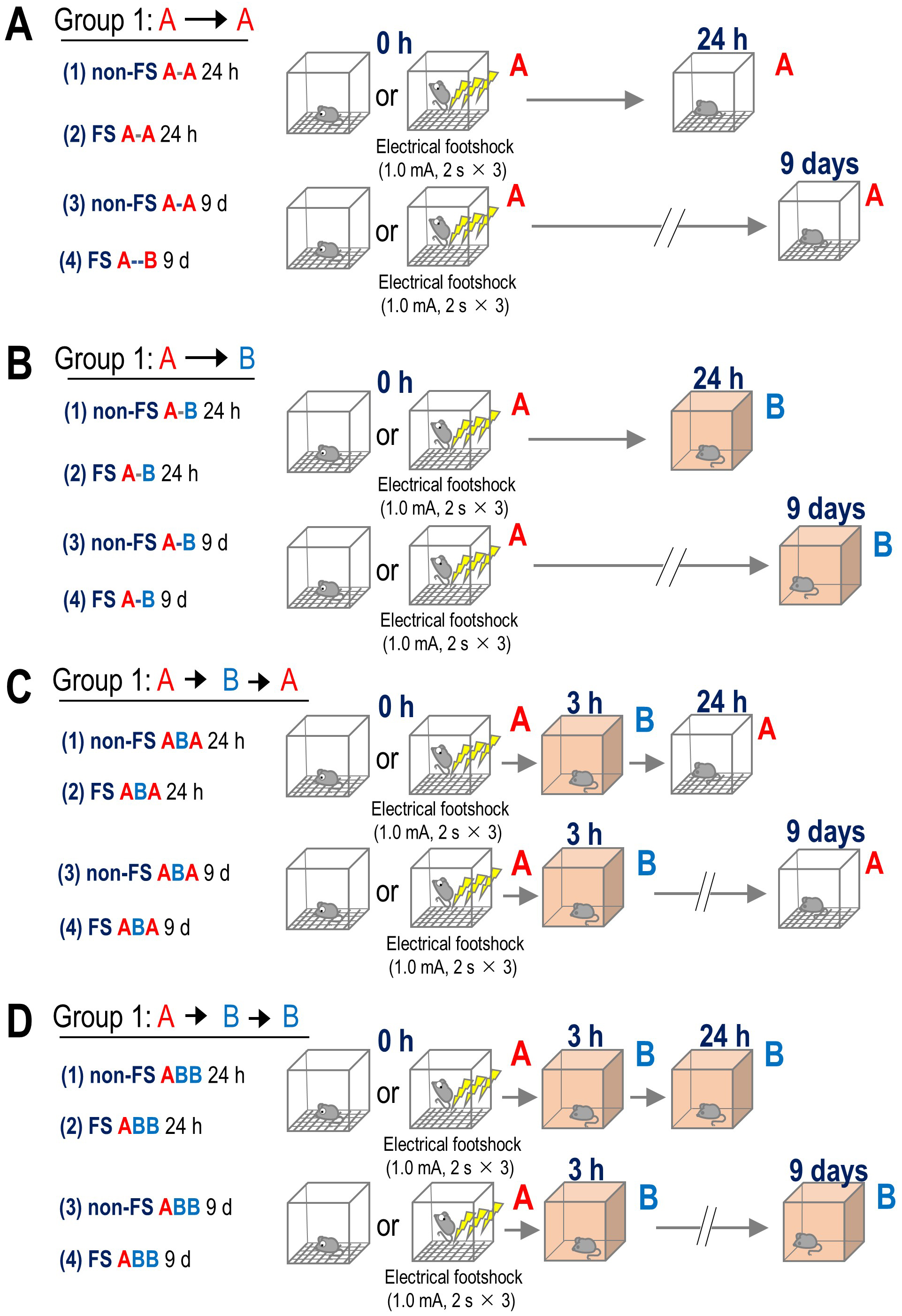

As previously described [5], the apparatus was constructed accordingly, with further details provided in the Supplementary Material. We randomly assigned adult male C57BL/6J mice (7–10 weeks old) to the behavioral testing groups. Two investigators blinded to the group assignments performed all behavioral tests between 11:00 and 16:00 h. We recorded all behavioral tests using a web camera installed with the ANY-maze software. The mice were handled for three consecutive days prior to the behavioral test. One hour before FS in Box A, all mice were habituated to Box A for 10 min. The mice were then subjected to FS (1.0 mA for 2 s, delivered three times at 100-s intervals) 3 min after being placed on the grid floor in Box A as Context A. The mice were subsequently returned to their home cages until the next context. The mice were randomly assigned to four groups (Fig. 1), with each group further subdivided into four subgroups based on whether they received an FS in Context A at 0 h or served as a control without FS (non-FS). They underwent a final test in either Context A or Context B at 24 h or 9 days after their initial exposure to Context A, as follows: Group 1: After the initial exposure to Context A, the mice were re-exposed to Context A for 5 min without electric shocks after 24 h or 9 days. The subgroups in Group 1 included: (1) non-FS A-A 24 h; (2) FS A-A 24 h; (3) non-FS A-A 9 d and (4) FS A-A 9 d (Fig. 1A). Group 2: After the initial exposure to Context A, the mice were exposed to the novel Box B (Context B) for 5 min without electric shocks after 24 h or 9 days. The subgroups in Group 2 included: (1) non-FS A-B 24 h; (2) FS A-B 24 h; (3) non-FS A-B 9 d; and (4) FS A-B 9 d (Fig. 1B). Group 3: After the initial exposure to Context A, the mice were exposed to Context B for 5 min after 3 h, followed by re-exposure to Context A at 24 h or 9 days. The subgroups in Group 3 included: (1) non-FS ABA 24 h; (2) FS ABA 24 h; (3) non-FS ABA 9 d; and (4) FS ABA 9 d (Fig. 1C). Group 4: After the initial exposure to Context A, the mice were exposed to Context B for 5 min after 3 h, followed by re-exposure to Context B at 24 h or 9 days (Fig. 1D). The subgroups in Group 4 included: (1) non-FS ABB 24 h; (2) FS ABB 24 h; (3) non-FS ABB 9 d; and (4) FS ABB 9 d. We cleaned the chambers with 70% ethanol between tests and detected freezing with ANY-maze software set to a minimum detection time of 1 s [14]. We expressed the freezing level as the percentage of time spent freezing and measured the distance traveled. In the present study, after confirming the effect of the drugs on freezing time at 3 h, 24 h, and 9 days, we subcutaneously administered the drug immediately after fear conditioning.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Apparatus and experimental paradigm for the contextual fear memory test. Electric shocks (1.0 mA for 2 s

To assess the effects of GR or MR agonists on receptor protein levels in the nuclear fraction of the hippocampus, Dex (a GR agonist) or FDC (an MR agonist) was administered subcutaneously. Mice were euthanized 30 min after drug administration, and hippocampal tissue was collected for nuclear protein extraction. To identify the corticoid receptor contributing to false context fear memory, Dex (10 µg/kg, s.c.) or FDC (5.0 mg/kg, s.c.) was immediately injected subcutaneously after Context A. The doses of Dex and FDC were determined based on previous findings, as it has been demonstrated that 10 µg/kg of Dex is the minimum dose that does not affect the motivation of mice to escape from aversive stress [15], and 5.0 mg/kg of FDC is the least effective dose affecting renal function in mice [16].

The mice in each experimental group were anesthetized with 1% pentobarbital sodium (Cat#: 26427-72, Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan), and hippocampal tissue was exposed and excised without any context exposure, either 1 h after the electric FS in Context A or 1 h after exposure to Context B at 3 h, 24 h, or 9 days. The mice were euthanized using a combination of anesthetics: medetomidine hydrochloride (0.3 mg/kg), butorphanol tartrate (5.0 mg/kg), and midazolam (4.0 mg/kg), followed by cervical dislocation after the behavioral tests. The brain tissues were placed in pre-cooled saline and thoroughly rinsed to remove blood and other impurities. Nuclear fractions were extracted using a commercially available LysoPur Nuclear Extractor Kit (FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals). We added complete Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (#4693159001, Merck Millipore, MA, USA) and PhosSTOP Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (#4906837001, Merck Millipore) to the nuclear fraction buffers before hippocampus homogenization. We doused homogenized mouse hippocampal tissues in nuclear fraction buffer and centrifuged the mixture (500

We anesthetized the mice with a mixture of medetomidine hydrochloride, butorphanol tartrate (0.3 and 5.0 mg/kg, respectively), and midazolam (4.0 mg/kg) and obtained blood samples by cardiac puncture with 26-gauge syringes. Next, we collected plasma in tubes containing 1.0% citrate (Cat. No. C0368, TCI) , 1.5 mg/mL EDTA-2Na (Cat. No. 15130-95, NACALAI TESQUE, INC.), and 12 U/mL of heparin (Cat. No. 081-00136, FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals) to protect the coagulant. We centrifuged the plasma samples at 1200

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Easy R) software [18] (version 1.38; Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) and BellCurve for Excel (version 3.20; Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) [19]. For comparisons between two groups, Student’s t-tests were used, and paired-sample t-tests were performed for within-subject comparisons. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparisons among more than two groups. When a significant main effect or interaction was observed in ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test was conducted. Two-way ANOVA was used to examine the effects of two interacting factors. Two-way and three-way repeated measures ANOVAs were performed when analyzing the interaction of two or more factors across multiple time points. In factorial analyses, electric FS versus no electric FS (non-FS) was defined as Factor 1, and Context A vs. Context B as Factor 2. For the drug administration experiments studies, FS versus non-FS was designated as Factor 1, and vehicle versus drug treatment as Factor 2. Statistical significance was set at p

Based on previous findings that false contextual fear memory can be formed within 3 h [3], we hypothesized that exposure to a novel environment shortly after a traumatic experience alters the specificity of the original fear memory. Therefore, in the present study, we characterized the effect of exposure to a similar but novel environment within 3 h after fear conditioning in mice.

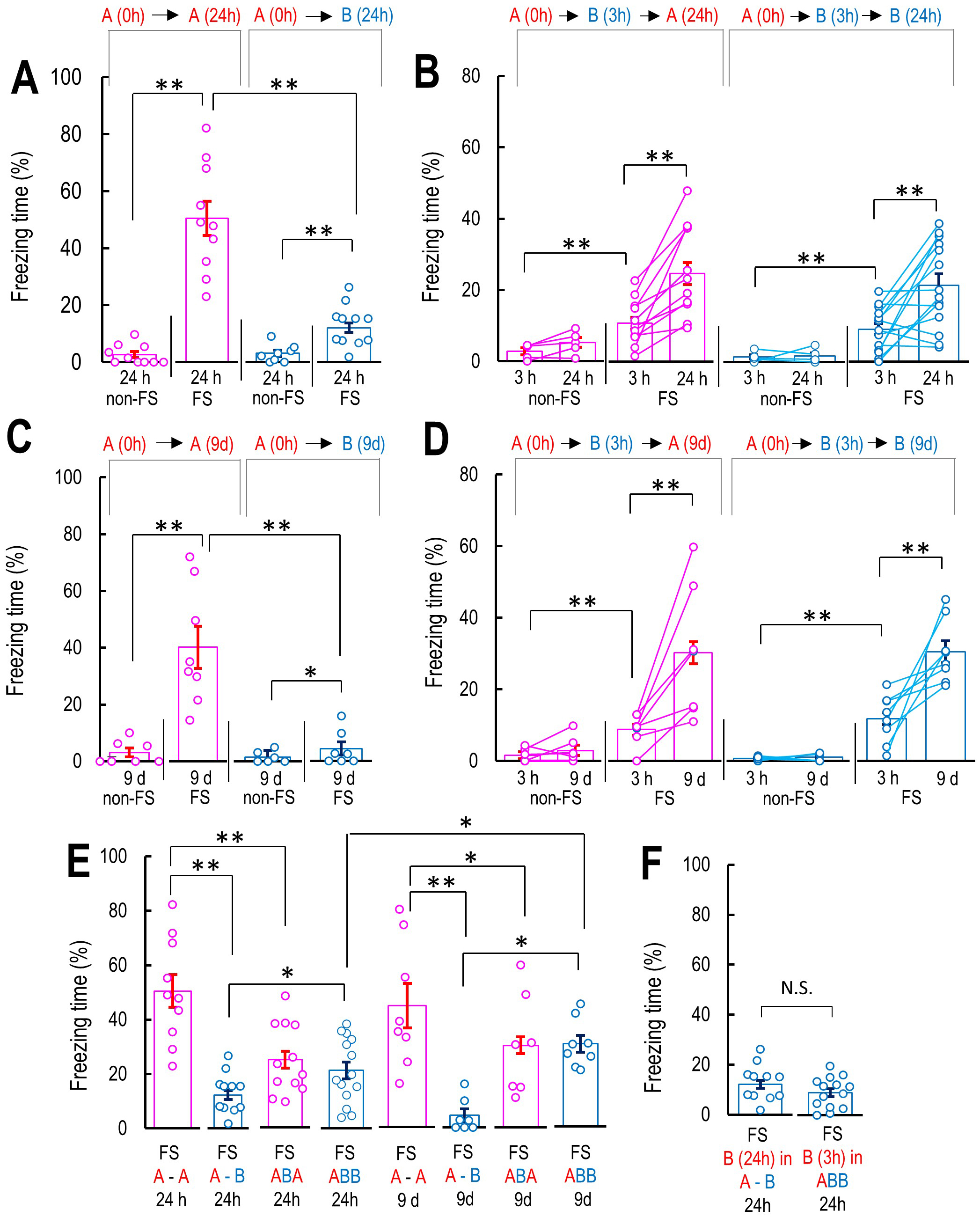

Two-way ANOVA showed a significant interaction between electric FS (FS vs. non-FS) and context (Context A vs. Context B) on freezing time during exposure to Context A or B, 24 h after the mice had been subjected to FS or non-FS in Context A (F(1, 34) = 29.5, p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Characterization of false context fear memory-dependent freezing behaviors. (A) Freezing level in the contextual fear conditioning models. The bar graphs show the percentage of freezing level in Context A 24 h after Context A with or without FS; non-FS A-A 24 h (FS: n = 10; non-FS: n = 10), Context B 24 h in non-FS A-B 24 h and FS A-B 24 h. (B) Freezing level in Context A during Context A with or without FS, followed by Context B 3 h and Context A or Context B 24 h, non-FS ABA 24 h (n = 5), FS-ABA 24 h (n = 12), non-FS ABB 24 h (n = 5), FS ABB 24 h (n = 14). (C) Freezing level in Context A or B at 9 days after Context A with or without FS, non-FS A-A 9 d (n = 7), FS-A-A 9 d (n = 8), non-FS A-B 9 d (n = 6), FS-A-B 9 d (n = 11). (D) Freezing level in Context A during Context A with or without FS, followed by Context B 3 h and Context A or Context B 9 d, non-FS ABA 9 d (n = 7), FS-ABA 9 d (n = 7), non-FS ABB 9 d (n = 6), FS ABB 9 d (n = 8). (E) Summary of the freezing levels in Context A or B 24 h or 9 days for comparison of freezing level in all conditions and the confirm the effect of Context B 3 h after the Context A. (F) Comparison of the freezing level in Context B at 24 h after the Context A with FS and without the exposure to Context B 3 h and the freezing level in Context B 3 h after the Context A with FS. Data are represented by mean

Similarly, in the 9-day groups (groups 3 and 4), two-way ANOVA showed a significant FS (FS vs. non-FS) and context (Context A vs. Context B) interaction on freezing time during exposure to Context A or B, 9 days after the mice had been subjected to FS or non-FS in Context A (F(1, 24) = 15.2, p

To evaluate how 3-h exposure to the novel Context B influenced subsequent fear expression, we summarized the freezing times at 24 h and 9 days across all groups that received electric FS in Context A. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant context (Context A vs. Context B)

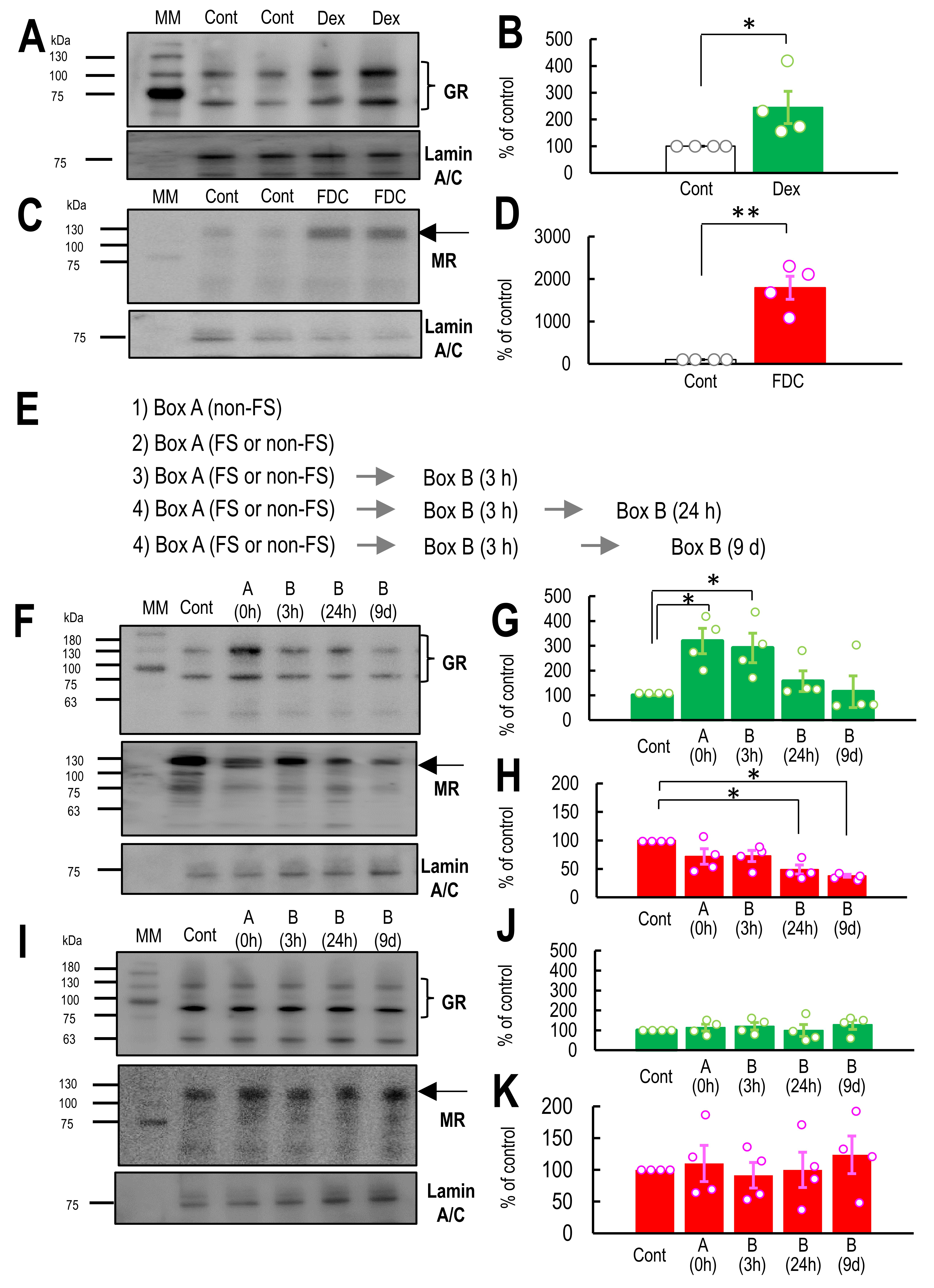

We previously demonstrated that the overexpression of hypothalamic CRF facilitated the formation of false contextual fear memories, and KD of hypothalamic CRF potentiated a false contextual fear response due to these memories [5]. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the GR and MR protein expression levels in the nuclear fractions obtained from the mouse hippocampus and their association with false contextual fear memories. In light of research that suggests that both GR and MR are translocated to the nucleus when activated by agonists [20, 21], we confirmed that the subcutaneous injection of Dex (10 mg/kg, s.c.), a GR agonist, increased the GR protein level in the nuclear fraction obtained from the mouse hippocampus (t-test: t(6) = 4.50, p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Dynamics of nuclear glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) protein levels in the hippocampus. (A) Western blotting membrane for GR and Lamin A/C in the nuclear fraction of the hippocampus in control and dexamethasone (Dex)-treated mice. (B) The graph shows the percentage of GR expression normalized by the control (100%) (n = 4). (C) Western blotting membrane for MR and Lamin A/C in the nuclear fraction of the hippocampus in control and fludrocortisone (FDC)-treated mice. (D) The graph shows the percentage of the GR expression level normalized by the control (100%) (n = 4). (E) A representative schedule (indicated by arrows) shows the timing of hippocampal tissue collection for Western blotting. Downward blue arrows indicate the time points at which tissue collection occurred. (F) Western blotting membrane for GR, MR, and Lamin A/C in the nuclear fraction of the hippocampus 1 h before (control) and after exposure to Context A and B at 3 h, 24 h, and 9 days. (G,H) The graph shows the percentage of GR (G) (n = 4) or MR (H) (n = 4) protein expression normalized by the control (100%) 1 h before (control) and after exposure to Context A and B at 3 h, 24 h, and 9 days after the electrical foot shock (FS) in Box A. (I) Western blotting membrane for GR, MR, and Lamin A/C in the nuclear fraction of the hippocampus 1 h before (control) and after exposure to Context A and B at 3 h, 24 h, and 9 days. (I,J) The graph shows the percentage of GR (J) (n = 4) or MR (K) (n = 4) protein expression normalized by the control (100%) 1 h before (control) and after exposure to Context A and B at 3 h, 24 h, and 9 days without the FS in Context A. Open circles in the graphs represent individual data points obtained from the western blotting experiments shown in panels (B) and (E). The black arrows indicate the MR protein bands. The two bands corresponding to GR are indicated by a closing brace symbol. Data are represented by mean

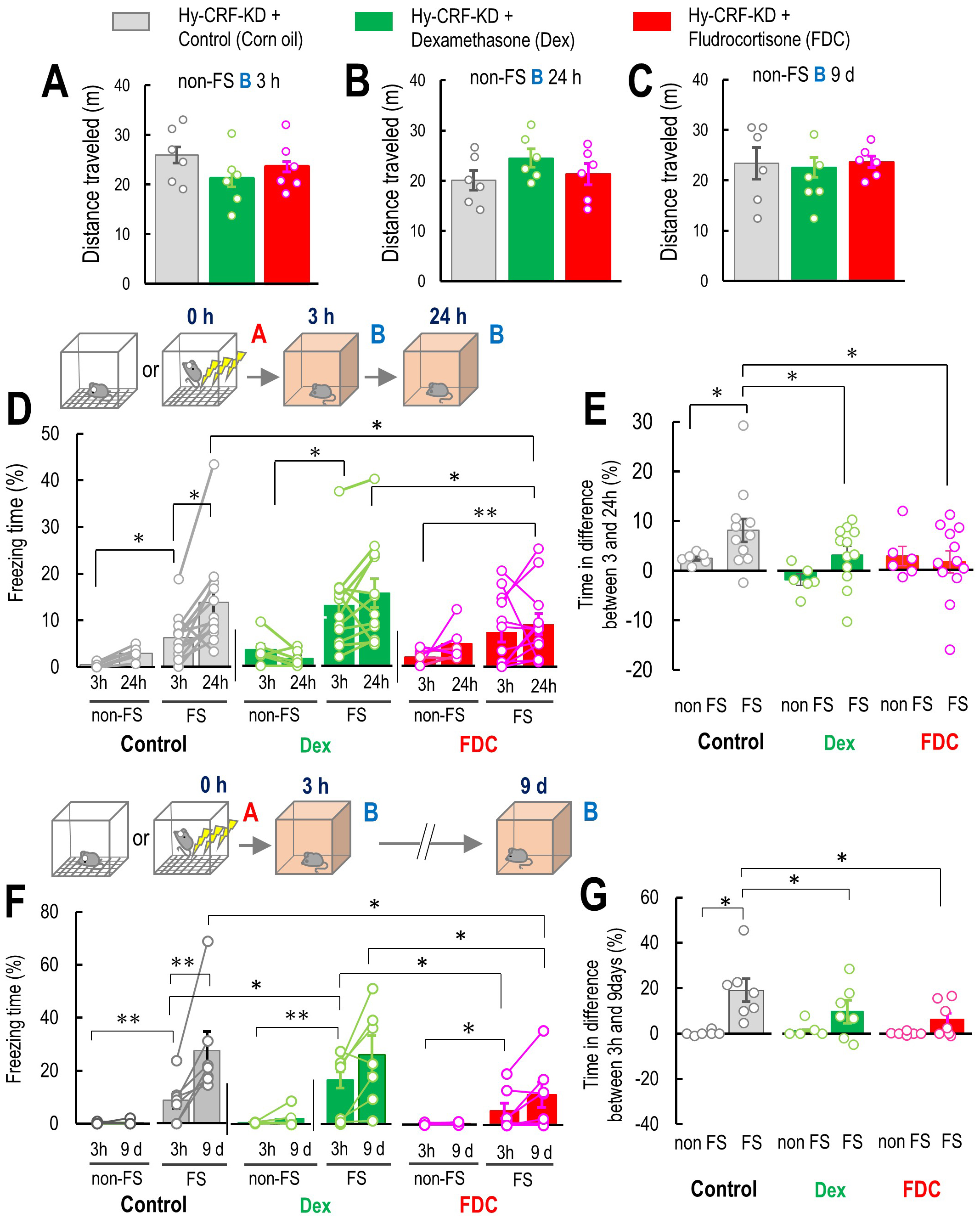

To investigate the contribution of GR and MR activations to the formation of false contextual fear memories at 3 h and the potentiation of false contextual fear memories at 24 h or 9 days in Context B after FS, we used the hypothalamic CRF KD mice to minimize the effect of intrinsic MR and GR activation via corticosterone. Hypothalamic CRF KD mice showed lower corticosterone levels than control adeno-associated virus (AAV) injected mice, but normal locomotor activity and fear sensitivity, and their formation of false contextual fear memories was comparable to that of control mice injected with control AAV (Supplementary Fig. 3), consistent with our previous findings [5]. We focused on the effect of drugs on FS-induced and -potentiated false contextual fear memories at 3 and 24 h or 9 days in Context B.

When the drugs were applied immediately after exposure to Context A without FS, one-way ANOVA indicated that locomotor activity in Context B at 3 h, 24 h, or 9 days was not affected by treatment with Dex or FDC, as the mice had not received FS in Context A (non-FS 3 h: F(2, 17) = 1.161, p = 0.340; non-FS 24 h: F(2, 17) = 1.334, p = 0.293; non-FS d: F(2, 33) = 0.0606, p = 0.941; Fig. 4A–C). These results suggest that neither Dex nor FDC affects the locomotor activities. Three-way repeated measures ANOVA (FS

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. GR and MR are involved in false contextual fear memory formation and potentiation. (A–C) The effect of co-treatment of dexamethasone (Dex: n = 12) or fludrocortisone (FDC: n = 12) on mouse locomotor activity (control: n = 12) at 3 and 24 h after the Context A without the electrical foot shock (non-FS, FS), non-FS B 3 h (A), 24 h (B), and 9 d (C). (D) Percentage of freezing level in Context B at 3 and 24 h for non-FS ABB 24 h and FS ABB 24 h mice with a vehicle as a control (non-FS: n = 6, FS: n = 12), Dex (non-FS: n = 6, FS: n = 12), and FDC (non-FS: n = 6, FS: n = 12) using hypothalamic Crf knockdown (KD) mice at 3 and 24 h after FS. (E) Percentage of freezing level in differences between 3 and 24 h in non-FS ABB 24 h and FS ABB 24 h with a vehicle as a control (non-FS: n = 12; FS: n = 14), Dex (non-FS: n = 10; FS: n = 14), and FDC (non-FS: n = 12; FS: n = 14) using hypothalamic Crf KD mice. (F) Percentage of freezing level in Context B at 3 h and 9 days for non-FS ABB 9 d and FS ABB 9 d mouse subgroups with a vehicle as a control (non-FS: n = 12; FS: n = 14), Dex (non-FS: n = 10; FS: n = 14), and FDC (non-FS: n = 12; FS: n = 14) using hypothalamic Crf KD mice at 3 h and 9 days after FS. (G) Percentage of freezing level in differences between 3 h and 9 days in non-FS ABB 9 d and FS ABB 9 d with a vehicle (control) (non-FS: n = 12; FS: n = 14), Dex (non-FS: n = 10; FS: n = 14), and FDC (non-FS: n = 12; FS: n = 14) using hypothalamic Crf KD mice. Inset illustrations represent the experimental designs. Hy-CRF-KD, hypothalamic CRF knockdown. Data are represented by mean

We also investigated the effect of Dex and FDC on the formation and potentiation of the fear response due to the false contextual fear memory at 9 days. Three-way repeated measures ANOVA (FS

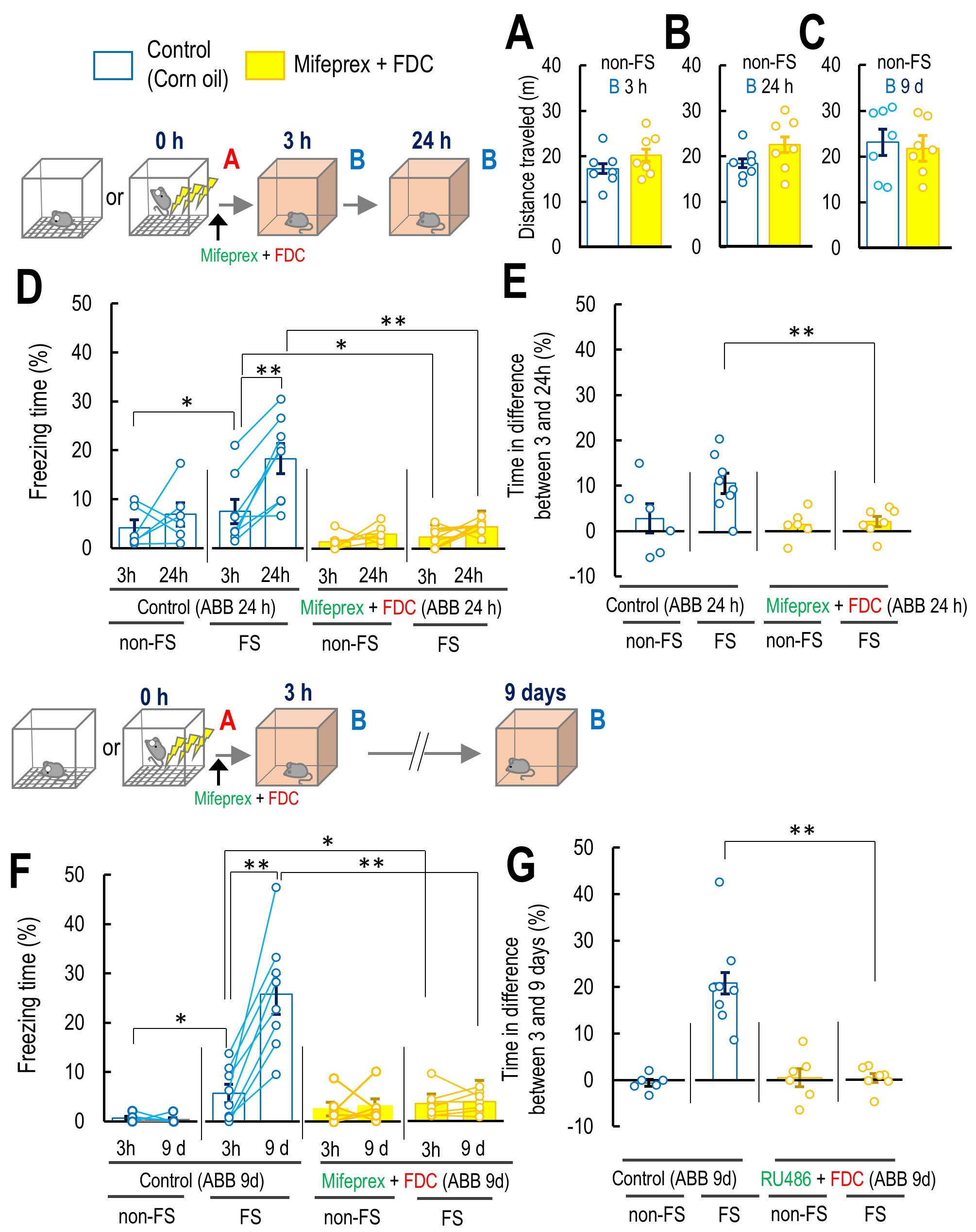

We investigated the effect of Mifeprex, an antagonist of GR, and FDC on the formation and potentiation of false contextual fear memory. Subcutaneous injection of Mifeprex and FDC immediately after Context A without FS did not affect the locomotor activities in Context B at 3 h, 24 h, and 9 days, respectively (Student’s t-test: 3 h: p = 0.274; 24 h: p = 0.124; 9 days: p = 0.752; Fig. 5A–C), indicating that co-administration of these drugs did not affect the locomotor activity in mice.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. The effect of co-treatment of mifepristone (Mifeprex) with FDC on the false fear memory formation and potentiation. (A–C) The effect of co-treatment of mifepristone (Mifeprex) with fludrocortisone (FDC) on the mouse locomotor activity in Context B 3 and 24 h or 9 d after the Context A without the FS, non-FS B 3 (A: 3 h: control: n = 7; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7), and 24 h (B: 24 h: control: n = 7; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7), and 9 d (C: 9 d: control: n = 7; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6). (D) Percentage of freezing level in Context B at 3 and 24 h for non-FS ABB 24 h and FS ABB 24 h (non-FS ABB 24 h: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6; FS ABB 24 h: control: n = 7; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7). (E) Percentage of freezing level in differences between 3 and 24 h in non-FS ABB 24 h and FS ABB 24 h in control and Mifeprex and FDC co-treated mice (non-FS ABB 24 h: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6; FS ABB 24 h: control: n = 7; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7). (F) Percentage of freezing level in Context B at 3 and 9 d for non-FS ABB 9 d and FS ABB 9 d (non-FS ABB 9 d: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6; FS ABB 9 d: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7). (G) Percentage of freezing level in differences between 3 and 9 d in non-FS ABB 9 d and FS ABB 9 d in control and Mifeprex and FDC co-treated mice (non-FS ABB 9 d: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6; FS ABB 9 d: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7). Inset illustrations represent the experimental designs. Data are represented by mean

Three-way repeated measures ANOVA (FS

Furthermore, three-way repeated measures ANOVA (FS

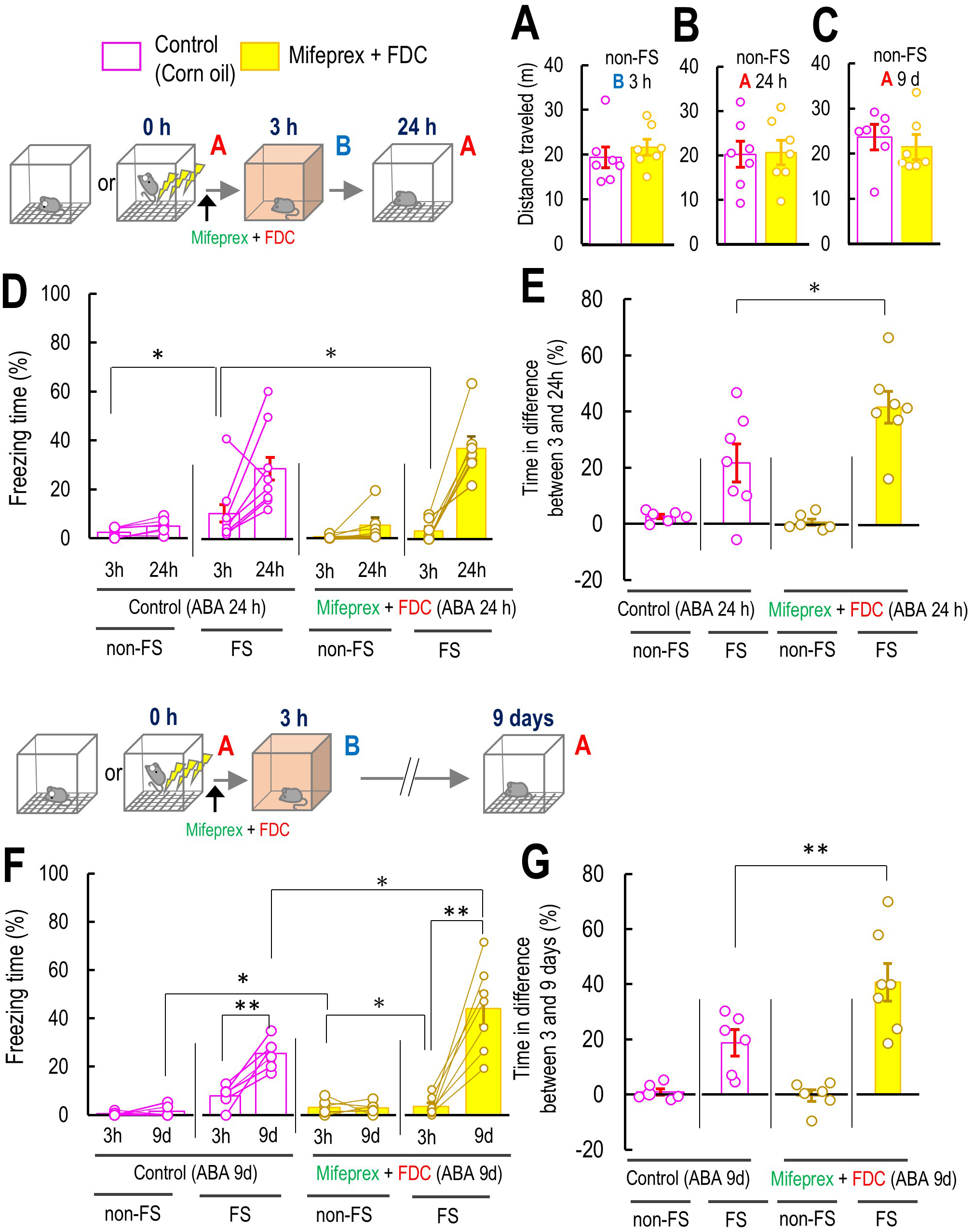

Next, we investigated how a GR antagonist and an MR agonist affect freezing levels in Context A at 24 h or 9 days, as a measure of original fear memory, in mice of the FS ABA 24 h and FS ABA 9 d groups that had been subjected to FS in Context A and were exposed to Context B 3 h after the initial Context A exposure. Mifeprex and FDC were administered subcutaneously to the mice immediately after they were subjected to electric FS or non-FS in the initial Context A. The locomotor activities in Context B at 3 h, and Context A at 24 h, or 9 days after Context A were not affected by the treatment of Mifeprex and FDC (non-FS Context B 3 h: p = 0.550; non-FS Context A 24 h: p = 0.991; non-FS Context A 9 days: p = 0.302; Fig. 6A–C), indicating that co-application of Mifeprex + FDC did not affect the mouse locomotor activities. Three-way repeated measures ANOVA suggested that the interactions among FS, drugs, and time did not affect the freezing levels in mice of groups non-FS and FS ABA 24 h (F(1, 22) = 2.72, p = 0.113, Fig. 6D). However, two-way ANOVA revealed that the interaction between FS and time significantly affected the difference in freezing time between 3 and 24 h (F(1, 25) = 5.81, p

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. The effect of co-treatment of mifepristone with fludrocortisone on the original contextual fear memory of Context A. (A–C) The effect of co-treatment of Mifeprex with FDC on the mouse locomotor activity in Context B 3 and Context B 24 h or 9 d after the Context A without the FS, non-FS B 3 (A: 3 h: control: n = 7; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7), and with FS, FS B 24 h (B: 24 h: control: n = 7; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7), and 9 d (C: 9 d: control: n = 7; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6). (D) Percentage of freezing level in Context B at 3 h and Context A 24 h for non-FS ABA 24 h and FS ABA 24 h (non-FS ABA 24 h: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6; FS ABB 24 h: control: n = 7; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7). (E) Percentage of freezing level in differences between 3 and 9 d in non-FS ABA 9 d and FS ABA 9 d in control and Mifeprex and FDC co-treated mice (non-FS ABA 9 d: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6; FS ABB 9 d: control: n = 7; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7). (F) Percentage of freezing level in Context B at 3 h and Context A 9 d for non-FS ABA 9 d and FS ABA 9 d (non-FS ABA 9 d: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6; FS ABB 9 d: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7). (G) Percentage of freezing level in differences between 3 and 9 d in non-FS ABA 9 d and FS ABA 9 d in control and Mifeprex and FDC co-treated mice (non-FS ABA 9 d: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6; FS ABB 9 d: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7). Inset illustrations represent the experimental designs. Data are represented by mean

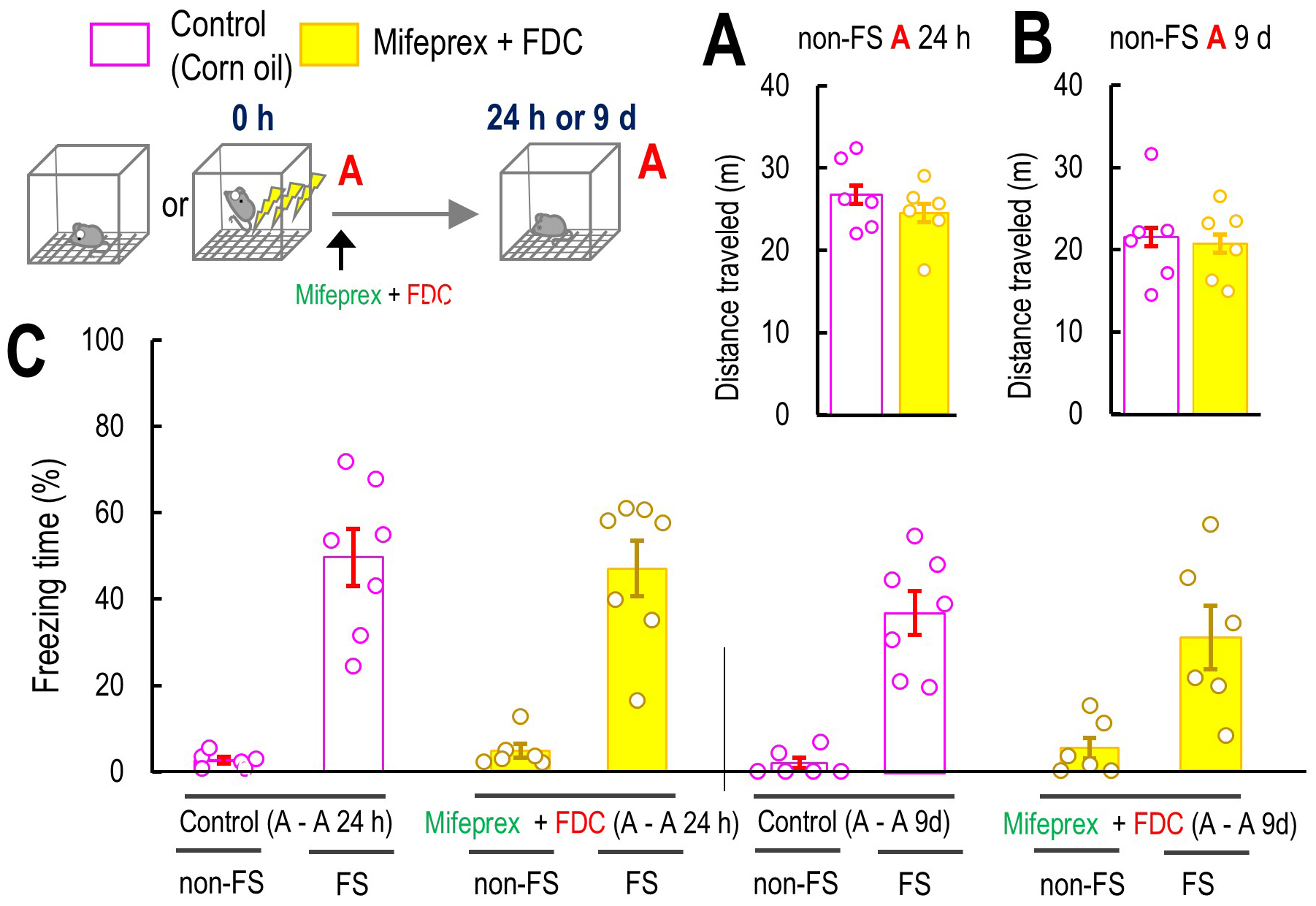

Finally, we investigated whether the GR antagonist and MR agonist affected freezing time at 24 h or 9 days, in mice that were not exposed to any other environment between the initial FS and re-exposure to Context A at 24 h or 9 days. We also confirm that the co-treatment of Mifeprex and FDC did not affect the locomotor activities 24 h and 9 days after Context A if the mice did not receive FS during Context A (non-FS Context A 24 h: p = 0.343; non-FS Context A 9 days: p = 0.465; Fig. 7A,B). Three-way ANOVA suggested that the interaction between FS, Mifeprex + FDC, and time did not significantly affect the freezing time (F(1, 50) = 0.219, p = 0.642, Fig. 7). These results suggested that if the mice did not experience the novel box before Context A 24 h or 9 days, GR antagonist and MR agonist did not affect the fear memory. Taken together, experiencing a novel environment after the fear event may produce false contextual fear memory by causing confusion between the actual fear event and the passage of time, leading to inaccurate memory recall.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. The effect of GR antagonist and MR agonist on original fear memory. (A,B) The effect of co-treatment of Mifeprex with FDC on the mouse locomotor activity in Context A 24 h or 9 days after the Context A without the FS, non-FS A-A 24 (A: 3 h: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6) or 9 days (B: 3 h: control: n = 6; Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6). (C) The effect of Mifeprex and FDC on the freezing level in 24 h after the Context A in non-FS A-A 24 h (control: n = 6, Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6), FS A-A 24 h (control: n = 7, Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7), and non-FS A-A 9 d (control: n = 6, Mifeprex + FDC: n = 6), and FS A-A 9 d mice subgroup (control: n = 7, Mifeprex + FDC: n = 7). Inset illustrations represent the experimental designs. Data are represented by mean

It has been demonstrated that when mice are exposed to two distinct contexts separated by 1 week, these contexts are encoded by overlapping neural ensembles in the hippocampal CA1 [22]. However, if these two contexts are separated by just 5 h, the two distinct contexts are encoded by independent populations of neurons [22]. The contextual fear memory may be initially specific but becomes less so within 9 days due to the diminishing precision of remote memory recall [23]. Time-dependent fear generalization has also been suggested to be attributed to the loss of context-specific reactivation patterns in the hippocampal ensemble within 9 days after fear conditioning [13]. As we previously demonstrated, when mice were exposed to Context B at 3 h after FS in Context A, their false fear response upon re-exposure to Context B at 24 h was greater than that observed at 3 h in Context B [5], and that induction of false fear response was further potentiated in 9 days in Context B than 24 h as we found in the present study. However, if the mice that had not been exposed to Context B at 3 h were first exposed to Context B at 24 h after FS, their false fear response at 24 h was similar in magnitude to that observed when they were first exposed to Context B at 3 h after FS. Furthermore, in mice not exposed to Context B at 3 h after FS, the false fear response observed at 24 h was smaller and comparable to the response observed in mice exposed to Context B at 3 h. Moreover, when the mice were later exposed to Context B for the first time at 9 days after FS in Context A, the false fear response remained comparable in magnitude to that observed at 3 h. In contrast, when mice were exposed to Context B once within a 3-h time window after FS in Context A, their fear response upon re-exposure to Context A at 24 h or 9 days, which depended on the actual fear memory of FS in Context A, was significantly smaller than that observed in mice not exposed to Context B 3 h. Taken together, we hypothesize that the specific memories of the fear experience in Context A, which are likely associated with hippocampal processing, may become time-dependently less precise if the mice re exposed to a different context within a narrow time window after the fear experience, eventually leading to memory confusion regarding which context was associated with the fear. Moreover, based on our results, we suggest that time-dependent loss of precision in memory does not occur simply due to the passage of time but rather from the experience of different environments shortly after the fear experience, which leads to confusion in memory about which context was associated with the fear.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) generally show clinical symptoms at a particular time after a traumatic event [24]. Contextual fear memory is time-dependently generalized by the diminishing precision of remote memory recall [23]. This generalization is attributed to the loss of context-specific reactivation patterns in the hippocampal ensemble 9 days after conditioning [13]. In our experimental condition, we did not observe a significant freezing response at 9 days in Context B unless the mice were exposed to Context B 3 h after FS. We compared this to the fear response at 9 days after Context A without FS. However, a significant freezing response was observed in Context B at 9 days after fear conditioning in Context A, when the mice were briefly exposed to Context B 3 h post-conditioning. Furthermore, by comparing the fear responses of mice not subjected to FS in Context A, we observed a significant false context fear memory at 3 h, 24 h, and 9 days. The fear response associated with false memory on day 9 was significantly larger than that observed on the first day after FS. These results suggest that specific memories of Context A become time-dependently less precise, leading to memory confusion. Although we detected GR and MR protein expression alterations in the nuclear fraction obtained from the hippocampus, it remains unclear if the false context fear memory observed 9 days after FS is hippocampal-dependent. Further research should clarify if this property could be observed 28 days after FS.

We found that a subcutaneous injection of Dex increased the GR protein level in the nuclear fraction obtained from the hippocampus. In addition, FDC also increased the MR protein level in the nuclear fraction obtained from the hippocampus. We also found a significant increase in the nuclear GR protein level obtained from the hippocampus after FS. This increase was sustained until 3 h after FS. In contrast, we observed a decrease in the protein level of MRs in the nuclear fraction obtained from the hippocampus at 24 h and 9 days after FS. It has been reported that the GR activations by Dex increased the GR protein level in the nucleus of breast cancer cells [25]. The inactivation of MR by spironolactone, an MR antagonist, decreased its protein expression level in the nucleus of hippocampal neurons [26]. The potentiation of the fear response was associated with a false contextual fear memory at the late phase in hypothalamic CRF KD mice [5]. Cortisol in humans and corticosterone in mice bind with a tenfold lower affinity to GR than to MR, which implies that GR becomes activated only with rising hormone levels after stress [27]. The neuronal effects of corticosterone, mediated by MRs and GRs, are long-lasting, and additional GR activation, such as after acute stress, generally depresses the CA1 hippocampal output, while corticosterone also blocks stress-induced HPA activation in hypothalamic CRF neurons via GR [28]. Therefore, based on our results, the GR was activated when the mice were exposed to a different context, not only when they received an FS in Context A. Meanwhile, MR was inactivated when the mice exhibited a significant fear response associated with a false contextual fear memory. These findings collectively suggest a temporal division of labor between GR and MR: GR activation in the early phase may promote generalized encoding by dampening hippocampal specificity, while delayed MR inactivation may facilitate consolidation of these generalized traces, reinforcing the false memory over time. This is in line with the dual-receptor theory of stress hormone action [29], where GR mediates rapid, stress-induced encoding shifts, and MR supports long-term precision and stability.

In the present study, we found that Dex facilitated the formation of false fear memories at 3 h in Context B, while FDC inhibited the potentiation of the fear response associated with false contextual fear memories at 24 h or 9 days in Context B, following FS in Context A. We also confirmed that the co-administration of mifepristone and FDC remarkably suppressed the formation and potentiation of false contextual fear memories in Context B at 3 h, 24 h, and 9 days, in naïve mice. These results indicated that GR activation contributes to the formation of the false contextual fear memories and that MR activation may ameliorate the potentiation of the fear response elicited by the false memories. Interestingly, we also found that the fear response in Context A at 9 days after FS in Context A was significantly larger than that observed in Context B 3 h after FS when mifepristone and FDC were co-administered to the mice immediately after FS. In addition, the difference in freezing time between 3 and 24 h in mice co-administered with mifepristone and FDC was greater than that observed in the control vehicle corn oil-treated mice, similar to the significant difference observed between 3 h and 9 days after FS. Therefore, the co-administration of mifepristone and FDC immediately after FS specifically suppressed the formation of false fear responses, while this co-administration also prevented the decrease in the fear response associated with actual fear memory.

GR activation reportedly impairs the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) in the hippocampal CA1 region [30, 31]. On the other hand, LTP in the CA1 region of the hippocampus was facilitated by MR activation [30, 32]. GR activation impairs the retrieval of long-term spatial memory in the hippocampus [33, 34], while reduced hippocampal MR expression is associated with impaired synaptic plasticity and spatial memory deficits in mice [35]. A study has demonstrated that intracerebroventricular corticosterone administration significantly suppressed LTP in the CA1 region of the hippocampus within 30 min in vivo [36], indicating that the increase in corticosterone in the brain dominantly activated the GR rather than the MR. Therefore, there is a possibility from our results that the GR activation and MR inactivation in the early phase of fear stress may disrupt the detailed spatial memory of Context A, producing the false contextual fear memory in Context B.

In general, it has been widely demonstrated that the same animal is used to test whether the mouse can discriminate between the actual context and different contexts when analyzing fear generalization, typically by assessing discrimination indexes [13, 37]. Indeed, it seems most appropriate to test both Context A, in which FS was administered, and Context B, in which no FS was given, using the same mice, in order to assess whether the fear memory has generalized. However, this method may complicate the assessment and interpretation of the time-dependent potentiation of false fear responses, as re-exposure to Context A, in which FS was delivered, 3 h after FS may interfere with the false fear response in Context B, thereby making it difficult to accurately evaluate the time-dependent potentiation of false fear responses and the loss of precise fear memory in Context A. Since the time-dependent potentiation of false fear responses is the major finding of our study, we employed this experimental model throughout the study, although future studies should investigate whether our experimental model is preferable to other models for examining the time-dependent potentiation of false fear responses.

Our findings demonstrate that exposure to a similar but distinct context (Context B) shortly after fear conditioning in Context A leads to a time-dependent enhancement of freezing behavior in Context B, suggesting the formation and gradual consolidation of false contextual fear memory. Importantly, the increase in freezing observed at B-24 h and B-9 d following B-3 h exposure was not seen in mice that were exposed to B-3 h without prior FS in Context A, supporting the interpretation that the behavioral response reflects fear memory generalization rather than anxiety due to novelty. This pattern is consistent with theories of systems consolidation, which propose that memories initially stored in the hippocampus undergo gradual reorganization into cortical structures, often resulting in reduced specificity and increased generalization over time [38]. Our data suggest that such reorganization may be vulnerable to interference from similar environmental cues encountered shortly after encoding.

Specifically, exposure to Context B within 3 h of fear learning may allow features of B to be incorporated into the original memory trace. This observation is in line with recent engram-based theories of systems consolidation, which suggest that memory representations may shift and reorganize over time, incorporating new contextual elements through ensemble overlap and reactivation [39]. This supports the idea that early post-learning exposure to similar environments can induce integration of novel elements into the original fear memory, rather than forming independent traces. In our paradigm, the presentation of Context B shortly after fear conditioning may lead to co-allocation of A- and B-related information into overlapping neuronal ensembles, producing a generalized fear memory that encompasses features of both contexts [22]. Moreover, the reduction in freezing observed in Context A at A-24 h and A-9 d following early B exposure implies that the specificity of the original memory is compromised. Rather than encoding B as a separate experience, the memory system appears to have merged A and B into a single, less precise representation. This could reflect an imbalance between memory integration and pattern separation mechanisms in the hippocampus.

The role of stress-related signaling pathways in this process is further supported by our molecular data. Western blot analysis revealed increased nuclear GR levels at B-3 h and decreased nuclear MR levels at B-24 h and B-9 d, suggesting that GR activation may be involved in the initial formation of false memory, while MR inactivation may contribute to its time-dependent consolidation. Pharmacological experiments further confirmed these roles: GR agonist treatment enhanced freezing at B-3 h, while MR agonist treatment suppressed freezing at B-24 h and B-9 d. Co-administration of a GR antagonist and MR agonist not only reduced freezing in Context B across timepoints but also restored higher freezing levels in Context A, suggesting enhanced memory specificity.

The involvement of stress hormones in memory generalization is consistent with prior reports that stress exposure alters hippocampal network dynamics and promotes integration over separation of contextual elements [40, 41]. From a clinical perspective, these findings may have important implications for understanding intrusive or generalized fear memories, such as those seen in PTSD. If the original memory trace is rapidly and robustly consolidated, it may serve to prevent the incorporation of unrelated contextual cues, thereby protecting against the development of false or intrusive memories. In contrast, if memory consolidation is incomplete or disrupted, the memory trace may remain vulnerable to contamination by similar but irrelevant contexts. This interpretation aligns with theoretical models suggesting that memory generalization and misattribution are key features in PTSD pathophysiology [42]. In light of this, enhancing the specificity and integrity of memory traces shortly after trauma exposure could be a promising strategy for preventing maladaptive fear responses. Our finding that the combined administration of a GR antagonist and an MR agonist not only suppressed false memory formation in Context B but also increased freezing in Context A supports this possibility.

In future studies, techniques such as activity-dependent engram tagging or optogenetic manipulation could be employed to determine whether the same neuronal ensembles are reactivated during freezing in Contexts A and B. Such investigations would provide direct evidence for the proposed neural overlap and offer further insight into the cellular mechanisms underlying memory integration and specificity, as well as false memory formation.

A notable limitation of the present study lies in the discrepancy between the localized genetic manipulation and systemic pharmacological interventions employed. While hypothalamic CRF knockdown (Hy-CRF-KD) mice were used to specifically reduce CRF expression in the hypothalamus, administration of GR and MR agonists (Dex and FDC) was performed via systemic subcutaneous injection. Although we confirmed that systemic administration Dex or FDC significantly increased GR and MR nuclear protein levels in the hippocampus, respectively, it remains difficult to exclude contributions from other brain regions or peripheral systems influenced by circulating corticosteroids. Moreover, in the present study, we demonstrated that the hypothalamic CRF KD induces a marked reduction in circulating corticosterone levels. In our previous study, we showed that the overexpression of CRF in the hypothalamus significantly increased corticosterone [5]. Therefore, these results, taken together, imply that hippocampal GR and MR activity may be indirectly modulated via systemic hormonal changes rather than solely by local hypothalamic signaling. Furthermore, although our data demonstrate the association between hippocampal GR/MR nuclear levels and false contextual fear memory formation and potentiation, we do not claim that hippocampal mechanisms alone fully account for the observed behavioral phenomena. Other brain regions, such as the amygdala or prefrontal cortex, may also contribute significantly to false memory processes, either through direct CRF signaling or via interactions with hypothalamic pathways. In this regard, the increased freezing observed in control electrically FS mice in Context A suggests the involvement of additional neural circuits or locally produced CRF within these regions. Additionally, previous findings showed that hypothalamic CRF overexpression enhanced false memory formation at 3 h in Context B after FS in Context A, while hypothalamic CRF KD increased false memory at 24 h in Context B, highlighting the complex and time-dependent role of hypothalamic CRF in false memory regulation [5]. These results suggest a nuanced temporal and spatial interplay between CRF signaling and corticosteroid receptor activation, warranting further investigation. Given the systemic nature of our pharmacological interventions and the hypothalamus-restricted CRF KD, it remains unclear whether the observed behavioral effects are mediated directly via hippocampal GR/MR signaling or involve broader neuroendocrine mechanisms. To address this, future studies employing region-specific manipulations—such as targeted receptor modulation in the hippocampus—would be necessary to clarify the precise contribution of hippocampal versus extrahippocampal structures to false contextual fear memory formation and generalization.

These findings suggest that fear memories gradually lose precision over time when another context is experienced shortly after the initial fear event, leading to confusion about the origin of the fear. Activation of GRs facilitates the formation of false contextual fear memories, while inactivation of MRs enhances the associated fear responses. Together, these results indicate that timely pharmacological intervention following a traumatic experience may help prevent the development of false contextual fear memories across different environments.

FS, electrical foot shock; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; KD, knockdown; HPA, hypothalamic pituitary adrenal; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; Dex, dexamethasone 21-phosphate disodium salt; Mifeprex, mifepristone; FDC, fludrocortisone; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; GFP, green fluorescence protein; PVDF, polyvinylidene fluoride; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean; LTP, long-term potentiation.

Data are available from the Mendeley data (doi: 10.17632/3w6trnfpvn.1) (https://data.mendeley.com/drafts/3w6trnfpvn). Data are also available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request and with the permission of TM and KS.

HA, KM, YK, FO, EK, and MM performed experiments and acquired and analyzed all data. TM generated the virus using a plasmid AAV-CRF-shRNA-GFP virus, designed the experiments, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KS designed the experiments, performed the experiments, and the analysis of all data. KS conceived and designed the experiments and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HA, KM, YK, FO, EK, MM, TM, and KS analyzed and interpreted all data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The Animal Care Committee of Ohu University approved this study (No. 2022-20 and 2023-16). All procedures adhered to the Animal Care Committee of Ohu University’s guidelines and the ARRIVE guidelines. All efforts were taken to minimize distress and use the minimum required number of animals. We strictly followed the laboratory animal care principles to reduce animal stress and use the minimum number of animals necessary for the experiments. The Institutional Recombinant DNA Experiments Committee of Ohu University (No. 2019004) and the Aichi Developmental Disability Center (No. 19-6) for all recombinant DNA experiments.

We thank Haruna Takahashi and Miyuu Abe for technical support for mouse behavioral studies. We gratefully acknowledge the help of past and present members of the laboratory.

This work was partly supported by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan, JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP19K06959 (KS and TM), and a part of JP24K09699 (KS and TM), JP18K06543 (TM), Research Funding Granted by Ohu University President (2023-6, 2024-07; KS) and the research grant by the School of Pharmaceutical Science, Ohu University (KS).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/JIN40000.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.