1 Department of Pharmacology and Neuroscience, Garrison Institute on Aging, and Center of Excellence for Translational Neuroscience and Therapeutics, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, Lubbock, TX 79430-6592, USA

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia in older adults, marked by a gradual and irreversible deterioration of cognitive abilities, including memory and thinking skills. AD is highly heterogeneous, with variations in amyloid and tau pathology, symptoms, proteostasis, neuroinflammation, and genetics. Dysregulated proteostasis and neuroinflammation, though usually protective, contribute significantly to disease progression. Proteostasis refers to the network that maintains the integrity of both intracellular and extracellular proteins, while neuroinflammation is the biological response to harmful stimuli. Proteostasis stress can activate immune responses and cause excessive inflammation, while impaired microglia and astrocyte function can further disrupt proteostasis and worsen disease progression. While numerous reviews on AD exist, this review focuses on the complex interplay between proteostasis and neuroinflammation in AD and their integral roles in disease pathology. Additionally, we will explore current and promising therapeutics targeting these processes, potential biomarkers, and the clinical trials conducted over the past 5 years, particularly those that address neuroinflammation and proteostasis, as identified through a PubMed search.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- Alzheimer’s disease

- proteostasis

- neuroinflammation

- proteotoxic stress

- microglia

- astrocytes

- brain

- cognition

- inflammation

- immunity

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common form of dementia in older adults, is a degenerative brain disorder that causes a steady and irreversible loss of memory and cognitive abilities [1, 2]. Around 6 million Americans over 65 are living with Alzheimer’s, and many younger people are affected too. As more people live longer, that number will likely grow, since age is the biggest risk factor [3]. After the discovery of AD, it was found in 1984 that the amyloid

Recent investigation supports that overactivated inflammatory responses in the brain, abnormal mitochondria, and impaired protein turnover are connected to AD [7]. Genome-wide association studies have established a link between AD risk genes and innate immune function, including microglia and inflammatory signaling molecules, suggesting a key role for neuroinflammation in AD [8]. Microglia are macrophage-like innate immune cells in the central nervous system (CNS) that can respond to disease progression by altering their physiological functions and inducing the activation of inflammatory pathways [9]. Microglia exist in different subtypes and can interact with various CNS cells, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and neurons [10]. Their activation and inflammatory response are crucial for neuroprotection. However, persistent and prolonged microglial activation and associated neuroinflammation are central pathological features of AD [11].

Neuroinflammation can have both helpful and harmful effects. It plays a protective role by activating immune responses, where astrocytes and microglia carry out phagocytosis to clear pathogens and debris. However, if this process becomes dysregulated, it may contribute to disease progression [12]. The dual nature of neuroinflammation becomes apparent when the negative effects of this process, causing harmful consequences for neurons in the patient’s brain, were observed [11, 13]. In each type of inflammatory reaction, the moment that marks the end of its duration is very important. It is an active process supervised by specialized mediators acting as regulators. Numerous studies have demonstrated a reduced concentration of neuroinflammation suppression regulators, which may be related to amyloid deposits present in the brain of AD patients, driving the inflammation process [14, 15].

Proteostasis is the maintenance of protein balance in the brain, a complex system crucial for cell function and survival. It includes the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the autophagic-lysosomal system which are responsible for the degradation of aberrant proteins under physiological conditions [16, 17, 18, 19]. AD is characterized by the accumulation of aberrant proteins, which signals a severe disturbance in the proteostasis network [17, 19]. Under normal conditions, the proteostasis network controls protein quality to prevent aggregation. However, if this system is disrupted, misfolded proteins build up, clump together, and form structured aggregates [20, 21, 22]. While AD has been proven to be heterogeneous and has many factors that can contribute to it, this review will be largely focused on the influence of neuroinflammation and aberrant proteostasis, the complex interplay between both in the pathogenesis and progression of the disease, and the recent therapeutic considerations involving neuroinflammation and proteostasis in the management and possible treatment of AD.

Under physiological conditions, inflammation is considered a beneficial physiological response within the brain and spinal cord, promoting clearance of neuronal debris, misfolded protein, and assisting in tissue repair [23]. However, when inflammation becomes prolonged and sustained, it contributes to a variety of chronic inflammatory diseases. In the central nervous system, brain-residing microglia and astrocytes are the primary sources of inflammation. Therefore, inflammation has been considered as a contributor to neurodegeneration, together with glial activation and peripheral immune infiltration, and proteostasis [24, 25]. Inflammation is a key part of AD pathophysiology, with astrocytes and microglia—which release chemokines and cytokines—being the first cells to respond [26, 27]. According to Paolicelli et al. [28], microglia exist in a dynamic continuum of transcriptional and functional states rather than simplistic binary categories such as “resting” or “activated”. This heterogeneity is shaped by age, brain region, sex, disease context, and environmental stimuli. The paper advocates for a refined nomenclature grounded in multi-omic characterizations—integrating transcriptomic, proteomic, epigenetic, and spatial data—to capture the full complexity of microglial biology. It also highlights the need for standardized reference atlases and cross-species comparisons to clarify distinctions between microglial states observed in health and disease, particularly neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, where microglia may have both protective and pathogenic roles. Similarly, Fumagalli et al. [29] utilized advanced single-cell RNA sequencing and computational modeling to identify a continuum of microglial states, termed the microglial state continuum (MSC), which reflects varying degrees of activation and functional specialization. They showed that this continuum is influenced by brain region, developmental stage, and disease state. In neurodegenerative contexts, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, microglia exhibit shifts towards less active or dysfunctional states, which may impair their ability to maintain homeostasis. The study also introduces tools for annotating microglial cell states based on gene expression profiles, offering a framework for future research into microglial function and pathology.

An inflammatory response usually begins with overexpression of interleukin (IL-1), monocyte-attracting chemokines, macrophage inflammatory proteins, prostaglandins (PG), factors of coagulation, reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide (NO), complement factors, proteases, and pentraxins, which in turn activate other processes and finally lead to a vicious circle that has a key role in the accumulation of amyloid plaques and neuronal death [27, 30]. As mentioned earlier, activated microglia trigger a cascade of signaling pathways, including the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) pathway, which regulates inflammation and apoptosis, and the nuclear transcription factor

Proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines secreted from microglia, astrocytes, T helper 1 cells, CD4+ cells, and dendritic cells regulate growth, differentiation, and cell activation. The major proinflammatory cytokines are interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor

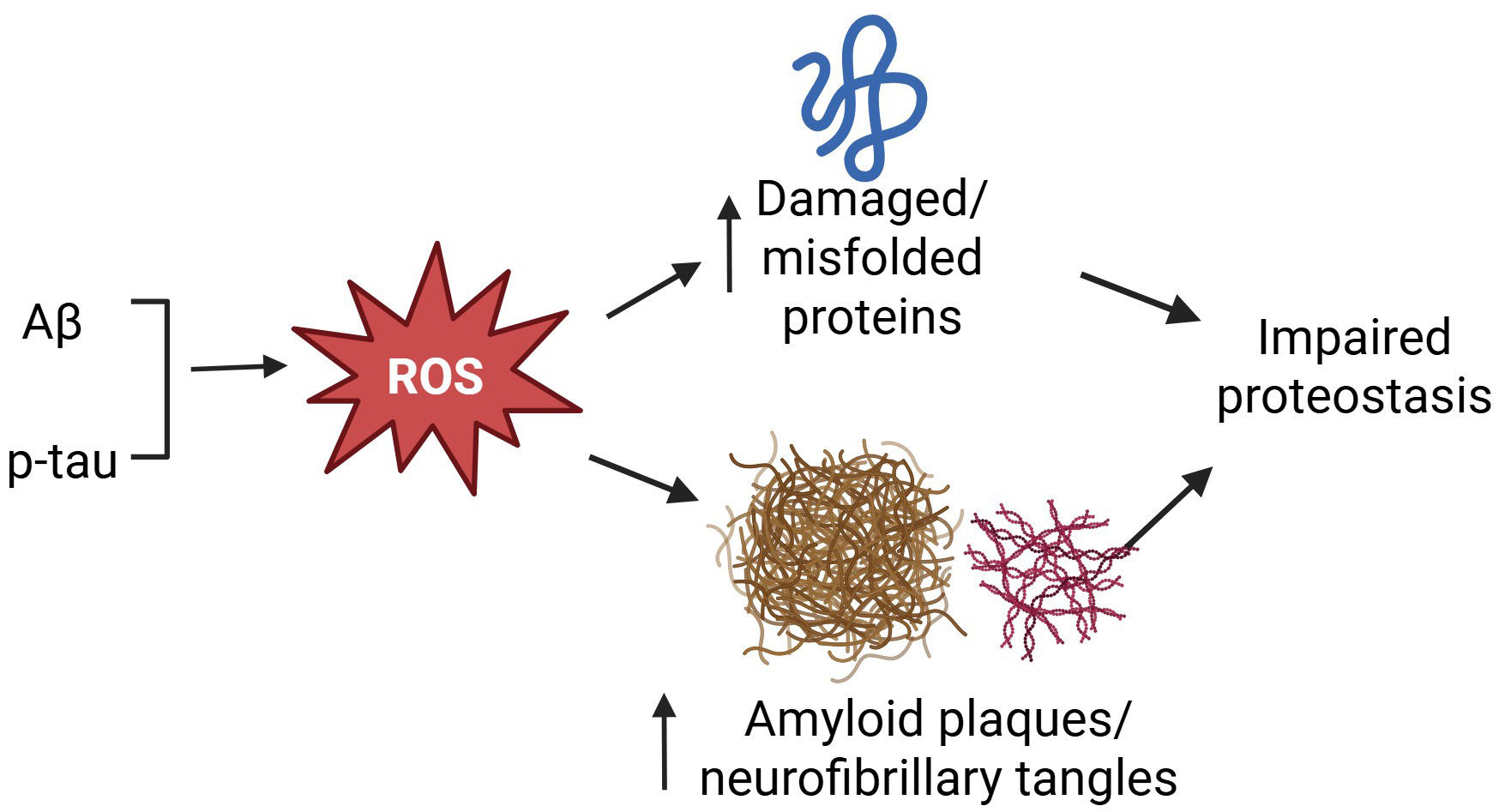

Oxidative stress (OS) occurs when the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) exceeds the capacity of the cell’s antioxidant defenses. OS plays a detrimental role in the pathogenesis of AD as neurons are particularly susceptible to OS due to their high oxygen utilization, weak antioxidant system, and high polyunsaturated fatty acid content in membranes [41, 42]. Studies show that antioxidant levels in the brain decline with age, thereby affecting the proteostasis of the brain by increasing susceptibility to protein misfolding [43]. OS results from the accumulation of oxidized and damaged macromolecules that are not efficiently removed and renewed. Proteins are highly susceptible to oxidative damage that inevitably affects the secondary and tertiary structure, causing an irreversible modification of protein structure and function [44, 45].

Many studies have shown links between protein homeostasis and OS. As mentioned above, during aging, the capacity of cells to maintain homeostasis and proteostasis decreases, leaving the organism susceptible to AD as proteins are irreversibly oxidized and cannot be efficiently degraded [46, 47, 48]. Considering these findings, the formation of toxic and large protein aggregates is a major consequence of protein oxidation and poor proteostasis. Insoluble aggregates can be formed as a result of covalent cross-links among peptide chains, as in the case of A

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Oxidative stress impairs proteostasis in AD. Increased production of amyloid peptides and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) enhances the generation of ROS to damage intracellular proteins and increase the accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to impaired proteostasis. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Aβ, amyloid β protein.

While mitochondrial dysfunction spans metabolic, oxidative, and proteostatic roles, one critical consequence is the leakage of mitochondrial DNA, which activates the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS–STING) pathway—linking mitochondrial damage to neuroinflammation in AD. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a key feature of AD pathology, which is characterized by altered cellular metabolism [52, 53, 54]. Mitochondria are present in all human body cell types (except mature red blood cells) to perform important cell fate-determining functions, and their abundance depends on the role of the cell. Under physiological conditions, mitochondria are well equipped with antioxidants like cytochrome c to mop up ROS, but during aging and in AD, these systems become dysfunctional [55]. Specifically, studies have shown that complex I and complex II are altered during aging and AD [56, 57, 58]. On the other hand, protein buildup within mitochondria impairs the electron transport chain’s function. It is noted that A

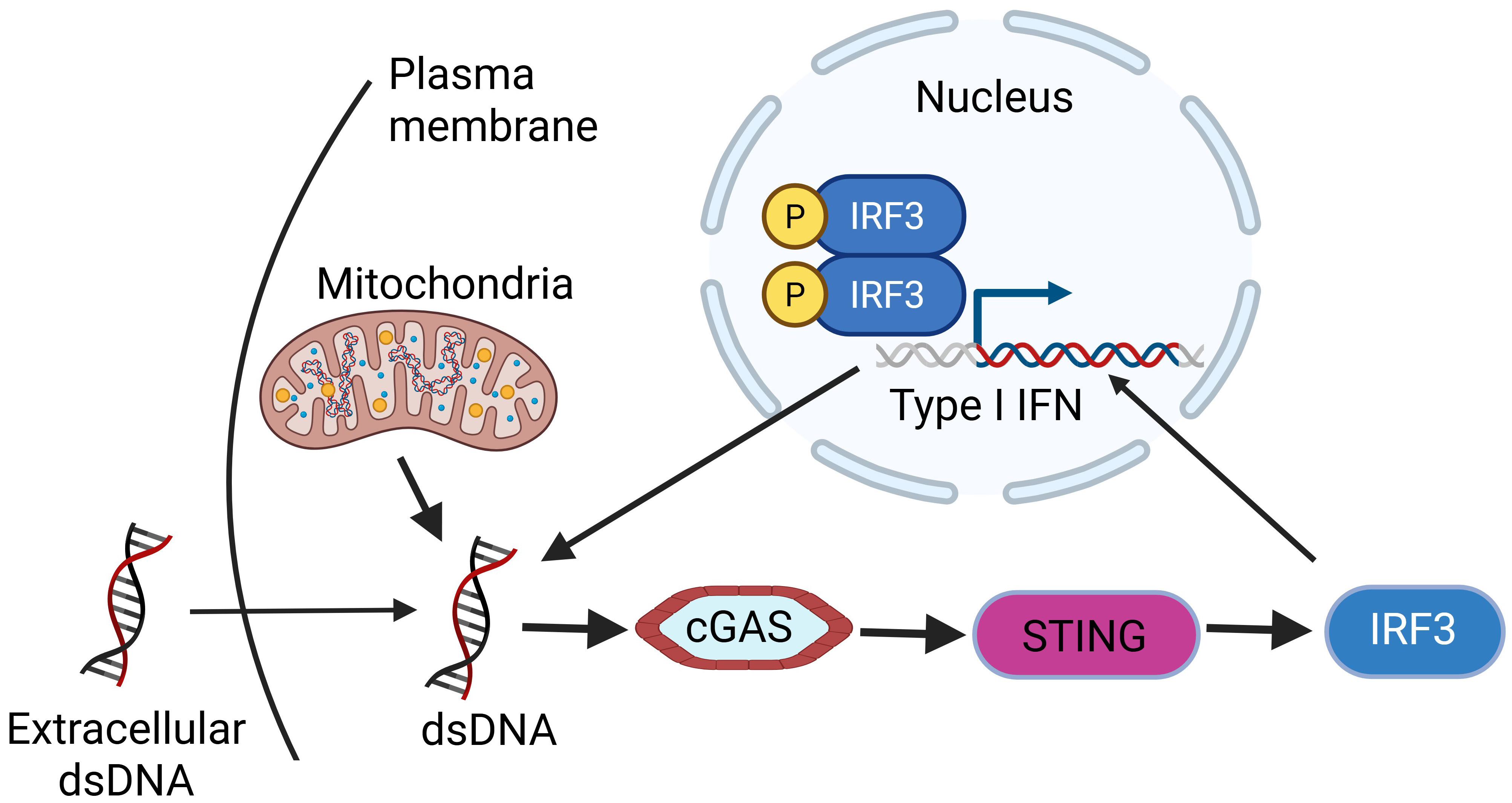

The cGAS-STING pathway functions as a DNA detector in the cytosol to identify damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and to trigger the inflammatory reactions through STING. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been recognized as a key contributor of AD, and when their damages occur, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is released into the cytosol, where the leaked mtDNA serves as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) to activate the cGAS-STING pathway, resulting in neuroinflammation [61, 62, 63].

The cGAS is a

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. dsDNA activates cGAS-STING signaling pathway to transcribe type I IFNs and trigger inflammation. Created with https://www.biorender.com/. dsDNA, double stranded DNA; IFNs, interferons; IRF3, interferon regulatory factor 3; cGAS, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; STING, stimulator of interferon genes.

Mammalian cells contain many distinct proteins that vary from cell to cell depending on the type, function, and status of the cell at various times [70, 71]. Proteostasis, or protein homeostasis, refers to maintaining a proper balance between protein production and breakdown, ensuring proteins are correctly synthesized, folded, and cleared when damaged or no longer needed. Proteostasis is essential in maintaining human cells’ healthy, as 33–35% of newly synthesized proteins are prone to misfolding under physiological conditions. Hence, it becomes crucial during aging as the activity of proteostasis machinery is reduced, causing aggregation and accumulation of damaged/aberrant proteins [72, 73].

Maintenance of protein homeostasis is important for cell function, fitness, and survival. As such, cellular integrity relies on proteolytic systems that not only maintain the proper concentration of regulatory and structural proteins but also scavenge damaged and misfolded proteins [3, 74]. The two main protein degradation systems are the evolutionarily conserved UPS, which is responsible for the degradation of both functional and dysfunctional short-lived proteins coupled with poly-ubiquitin molecules, and the autophagy-lysosomal system that degrades long-lived proteins, large aggregates of proteins, cellular components, and organelles [75, 76]. Proteostasis can be modified by pathogens, aging, environmental changes, cellular stress, and a host of other factors [77, 78].

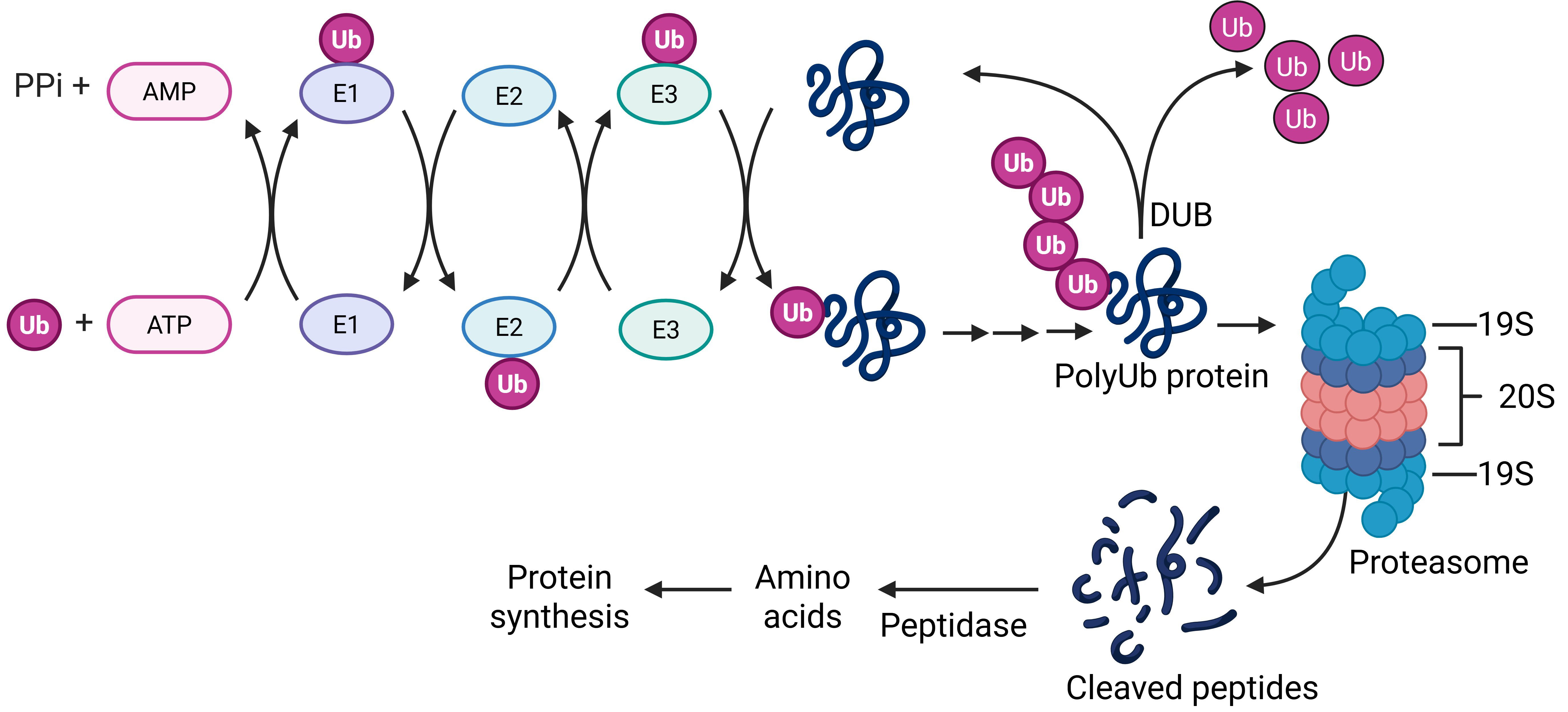

The UPS consists of the ubiquitin conjugation system and the proteasome, working together to degrade intracellular proteins. Ubiquitination or polyubiquitination serves as a tagging mechanism, marking proteins for destruction, while the proteasome carries out the actual degradation process. Together, they help cells maintain proteostasis [79, 80, 81]. Through the UPS pathway, potentially toxic proteins marked for degradation are broken down into small peptides, which can then be recycled to restore intracellular amino acid levels [82] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. UPS pathway. In the presence of ATP and the three ubiquitin enzymes (E1, E2, and E3), a Ub is covalently added to a substrate protein. Repeat ubiquitination leads to a polyUb chain attached to the protein to mediate the substrate protein interacting with the proteasome for degradation. A DUB reverses the ubiqutination process to stabilize the substrate protein. Created with https://www.biorender.com/. UPS, ubiquitin proteasome system; Ub, ubiquitin; DUB, deubiquitinating enzymes.

Protein degradation via the UPS pathway starts with ubiquitin (Ub) [83]. Downstream of the ubiquitination reaction is the degradation of polyUb-tagged proteins by proteasome, a multiple-protein assembled large complex composed of two particles: the regulatory 19S complex which aids substrate recognition, deubiquitinating, unfolding of protein and uncoiling of protein for degradation, and the 26S catalytic complex which is hollow, cylindrical, composed of two inner and two outer rings responsible for the actual degradation of substrate protein [84, 85] (Fig. 3). Extensive research has demonstrated that the UPS plays a vital role in eliminating AD-related pathological proteins, and its impairment is associated with increased severity of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Tau is degraded by 26S proteasome in a ubiquitin- and ATP-dependent manner because phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated tau proteins are the substrate of ATP/Mg2+-dependent proteasome [86]. In contrast, when UPS is disrupted, accumulation of nondegraded protein and neuroinflammation will occur.

Autophagy is a major proteolytic system in the cytoplasm and removes aggresomes by lysosomal degradation [87]. Under physiological conditions, there is usually no buildup of aberrant protein as the clearance rate is always higher than the production rate. Autophagy, also known as autophagocytosis, is one of the ways that the brain ensures this happens; it is a self-eating process that delivers cytoplasmic cargo to the lysosome for degradation [5, 18]. The autophagy-lysosome pathway (ALP) involves the biogenesis of a unique organelle enclosed by a double lipid bilayer, named the autophagosome. During autophagy, autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes, where protein-containing vacuoles are broken down by hydrolytic enzymes. Age-related, stochastic, non-enzymatic, post-translational modifications, as well as macromolecules, cytosolic portions, and entire organelles, are usually degraded by the ALPs via lysosomes [88, 89].

Neurovascular unit (NVU) dysfunction and the glymphatic system have been implicated in neuroinflammation and proteostasis in AD. NVU plays an important role in maintaining homeostasis of the brain microenvironment and the accelerated aging of NVU cells may directly impair NVU function and contribute to AD pathogenesis [90]. Thus, rescuing NVU dysfunction might be a viable approach to AD treatments [91]. One study has showed that the diameter of microvessels and PV (Parvalbumin) neuron numbers were decreased, the microglial number was increased, and spatial learning was deficient in the hippocampus at 24 months of age, suggesting that the impairment of the hippocampal neuro-vascular unit precedes changes in spatial cognition in naturally aged rats [92]. In addition, single-nucleus transcriptome analysis identified eight main cell types and the expression patterns of aging-related genes in NVU cells of AD [90].

The glymphatic system is considered to be associated with the pathogenesis of AD, although the alterations of the glymphatic system along the AD continuum are still unknown, it is suggested that cognitive dysfunction is closely associated with the activity of the glymphatic system [93]. Evidence showed lower diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) index was found in patients with AD dementia, which may suggest impaired glymphatic system function [94]. A new small molecule, OAB-14, enhances the clearance of brain A

Extracellular A

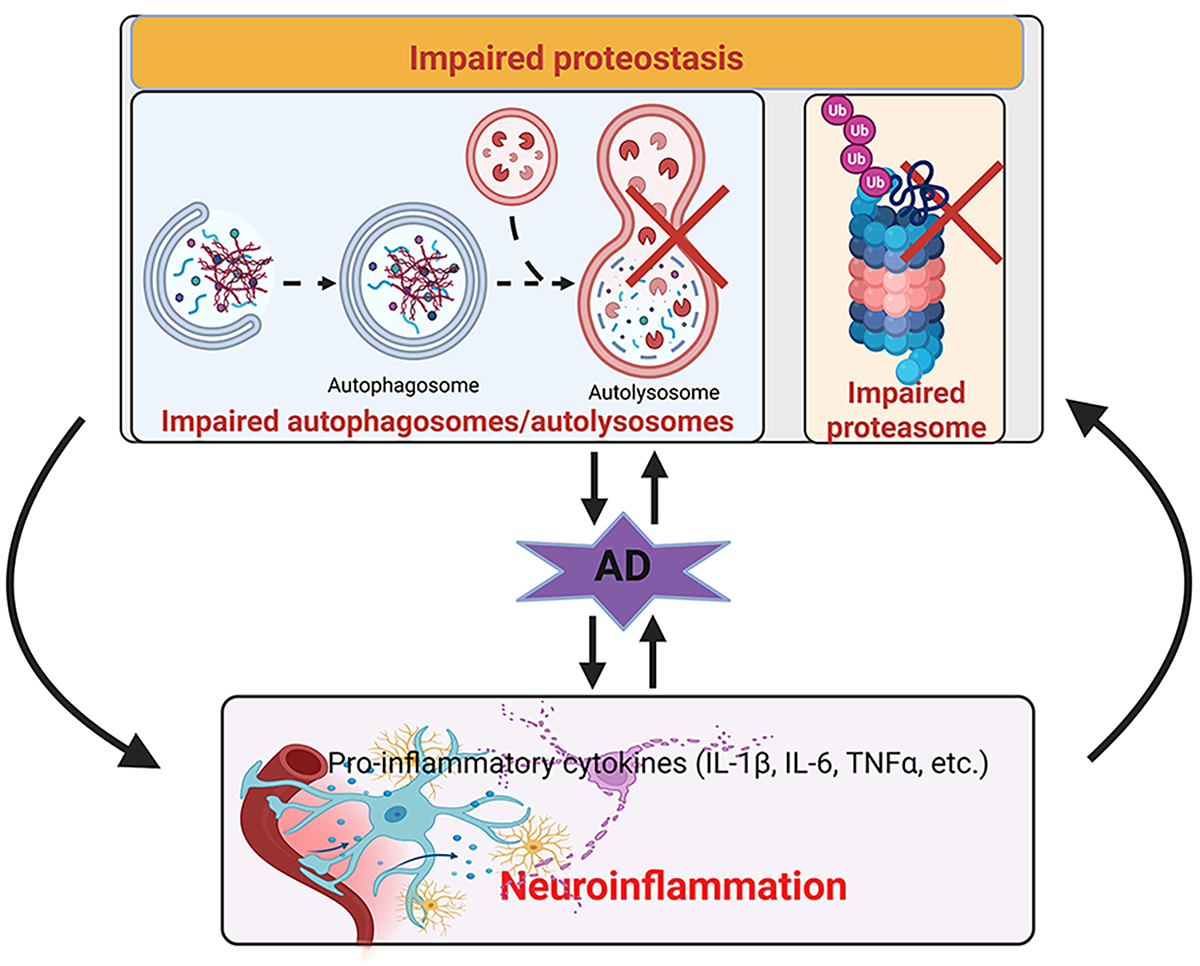

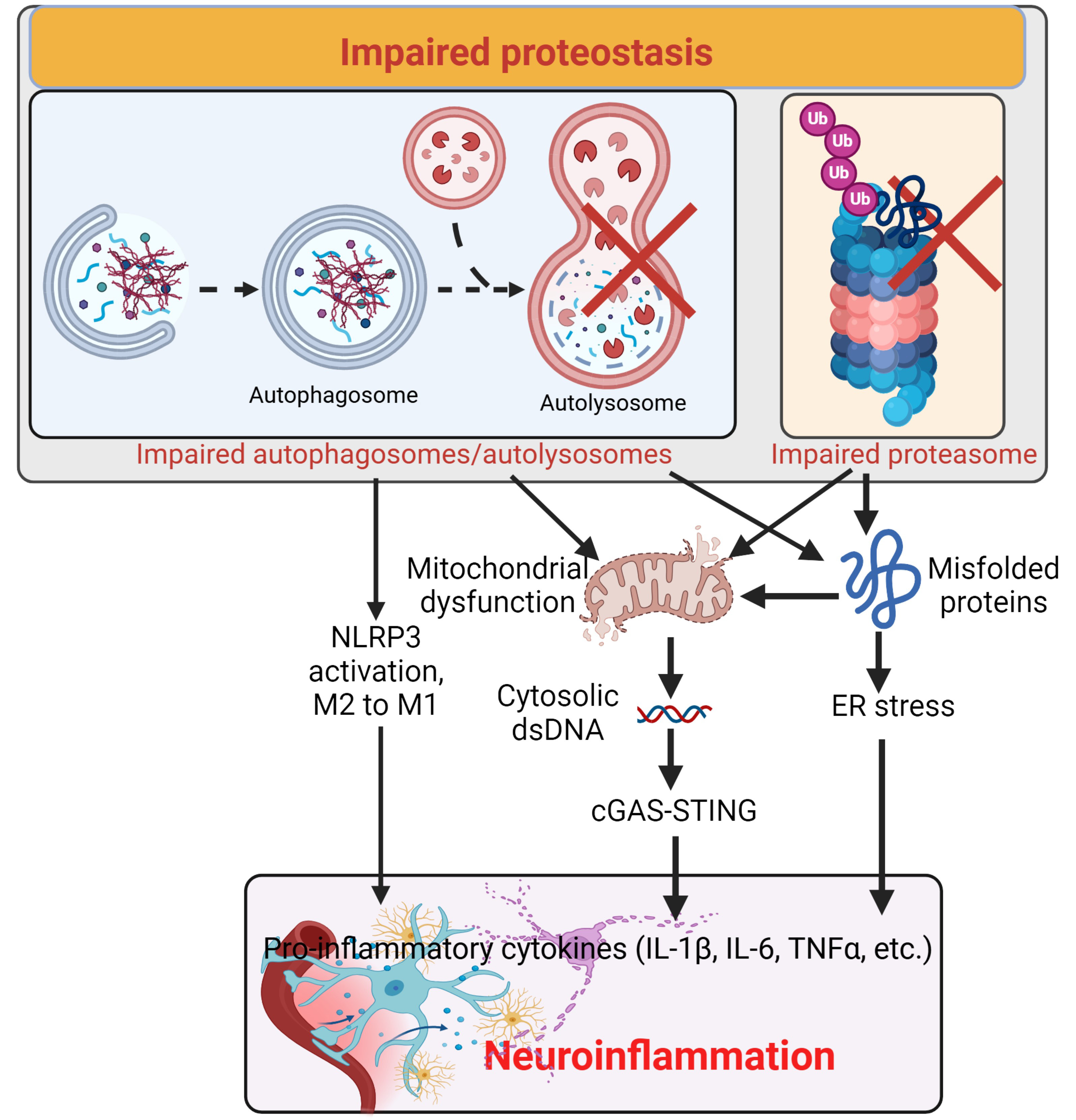

The cellular stress response is a major regulator of the proteostasis network in various scenarios of induced imbalance in proteostasis. Previous data show that impaired proteostasis leads to toxic protein buildup and mitochondrial dysfunction, triggering an immune response; when excessive, this inflammation can contribute to neuronal dysfunction [102, 103]. For instance, when the neuronal proteasome function is disrupted, this causes mitochondrial DNA to be released into the cytosol, activating the cGAS-STING pathway and triggering neuroinflammation and necroptosis in the animal brain (Fig. 4). Likewise, autophagy and mitophagy dysfunctions are found in most AD cases, likely caused by A

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Impaired proteostasis induces neuroinflammation. Impaired proteasome and autophagy cause accumulation of misfolded proteins and mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to ER stress and release of dsDNA from the mitochondria and/or nuclei to activate the cGAS-STING pathway inducing neuroinflammation. Additionally, impaired autophagy also activates the NLRP3 and facilitates the conversion from M2 to M1 of microglia, enhancing neuroinflammation. Created with https://www.biorender.com/. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; NLRP3, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain leucine-rich repeat and pyrin domain containing 3; ×,impairment.

Inflammasomes are multiprotein complexes present in microglia, astrocytes, neurons, endothelial cells, and macrophages within the CNS; they are part of the innate immune system that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [103, 104]. The activation of inflammasomes, such as the NLRP3 which is a key component of inflammasomes, has been reported in several neurodegenerative diseases because they activate caspase-1 and the subsequent release of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1 and IL-18 [103].

Amyloid-

As mentioned above, microglia are one of the first immune cells that get activated and recruited to the site of infection or injury as an inflammatory response [111]. It is noted that microglia express the purinergic receptors that act as ATP-activated ion channels abundantly present on the surface of microglia and play a role in immune response [112, 113]. One type of purinergic receptor is called the P2 receptor, which can be activated by metabolites and A

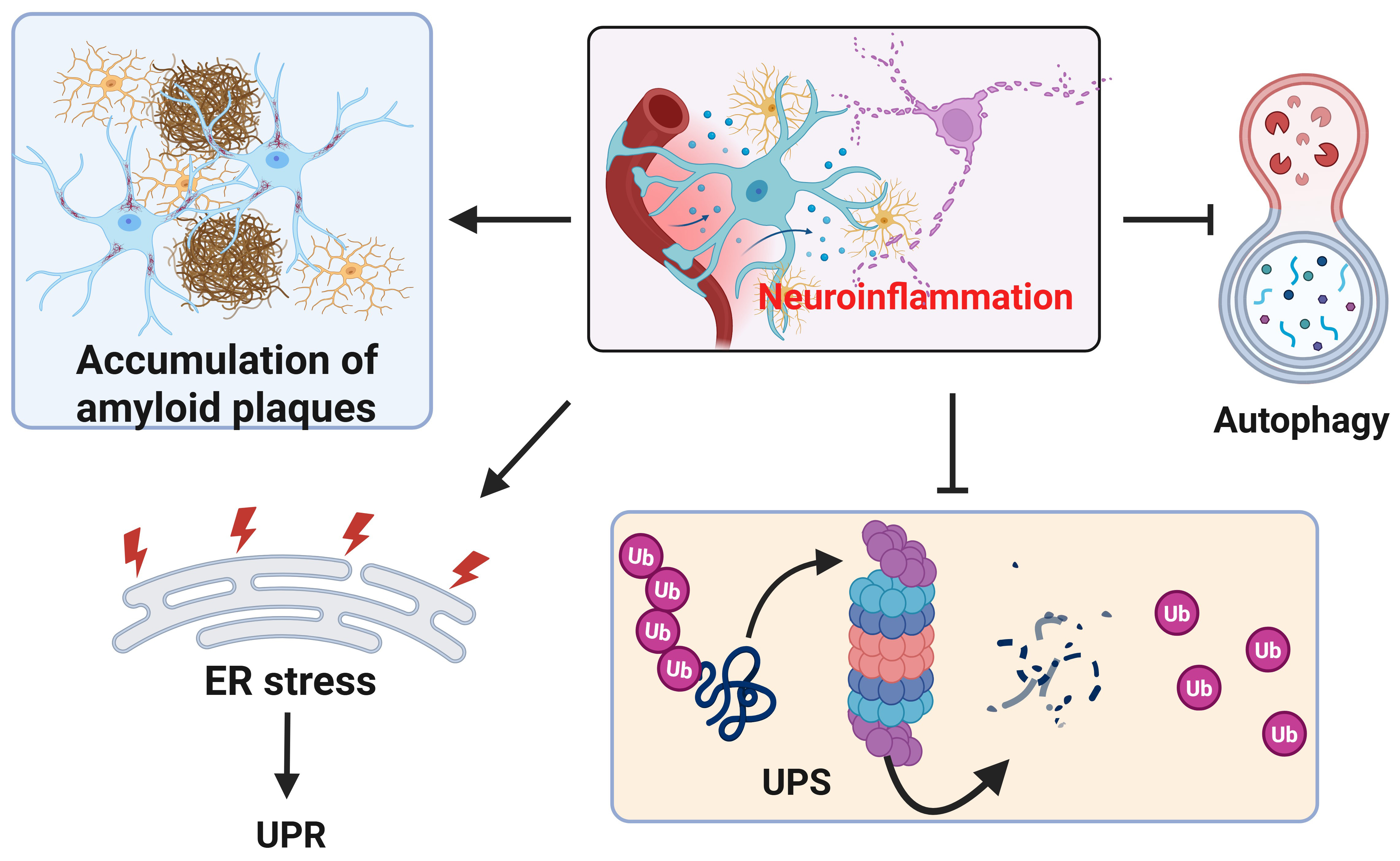

However, the challenge lies in the fact that overstimulating these receptors can lead to excessive production of inflammatory factors such as TNF-

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Neuroinflammation impairs proteostasis. In presence of neuroinflammation, the accumulation of amyloid plaques and p-tau (not shown) increases (upper left). In addition to inducing ER stress and unfolded protein response (UPR) in the ER, neuroinflammation also inhibits UPS and autophagy. Created with https://www.biorender.com/.

AD is a heterogeneous condition, characterized by variability in amyloid composition, tau distribution, the relationship between amyloid and tau, clinical symptoms, neuroinflammation, age, and genetic background. This complexity has led to the development of multiple research and treatment strategies targeting different aspects of the disease, such as oxidative stress, genetic mutations, gut microbiome disruption, protein homeostasis (or proteostasis), neuroinflammation, and more. Here, we focus specifically on research and therapeutic strategies targeting neuroinflammation, proteostasis, and their interplay in the management of AD.

Current drugs used in the management of AD either target cholinergic or glutamatergic neurotransmission, which only relieve the symptoms. There is no curative medication available, though there are many ongoing clinical trials for such drugs. Some newly developed agents target the amyloid and tau proteins [132]. Donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine are the current three acetylcholinesterase inhibitors that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and they act via modification of the cholinergic system. They are usually used for mild to moderate AD, while Memantine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist of the glutaminergic system, was approved in 2003 for moderate to severe AD. These drugs improve cognition in the patient and ease the social and economic burden [133]. A lot of reviews have done a deep dive into the above medications, so we will not dwell on them here. Researchers are developing various agents with the hopes of finding a lasting solution to AD. The list of such drugs that are in clinical trials is long, and those related to neuroinflammation and proteostasis mechanisms in the past five years (2019 till date) using PubMed search are mentioned in Table 1 (Ref. [134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163]).

| S/N | Agent | Route | Target | AD Stage | Phase | Reference |

| 1 | Hydromethylthionine Mesylate | Oral | Tau aggregation inhibitor | Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)-AD | III | [134, 135] |

| 2 | Buntanetap | Oral | Neuroinflammation, A | Mild AD | I | [136] |

| 3 | AADvac1 (active peptide vaccine) | IV | Tau aggregation | Mild AD | II | [137] |

| 4 | Gosuranemab (anti-tau monoclonal antibody) | IV | Tau aggregation | Mild AD | II | [138] |

| 5 | Semorinemab | IV | Tau aggregation and microglia activation (neuroinflammation) | Mild-Moderate AD | II | [139, 140, 141] |

| 6 | MAPTRx (Tau-targeting antisense oligonucleotide) | IV | Tau aggregation | Mild AD | Ib | [142] |

| 7 | Tilavonemab | IV | Tau aggregation | Mild AD | II | [143] |

| 8 | NPT088 | IV | A | Mild-Moderate AD | Initial | [144] |

| 9 | Neflamapimod (p38 | Oral | A | Mild AD | II | [145] |

| 10 | Lecanemab (humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody) | IV | A | Mild AD | III | [146, 147, 148] |

| 11 | Donanemab | IV | A | Mild AD | II | [149] |

| 12 | Gantenerumab (anti-A | IV | A | Mild AD | III | [150] |

| 13 | Aducanumab (human monoclonal antibody) | IV | A | Mild AD | III | [151] |

| 14 | Aducanumab (Japanese subgroup Analysis) | IV | A | Mild cognitive impairment-AD (MCI-AD) | III | [152] |

| 15 | CT1812 (modulator of the sigma-2 receptor (S2R)) | Oral | A | Mild-Moderate AD | II | [153] |

| 16 | CT1812 (modulator of the sigma-2 receptor (S2R)) | Indwelling cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) catheter | A | Mild-Moderate AD | Ib | [154] |

| 17 | Atabecestat (JNJ-54861911) | Oral | βAPP-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) inhibitor | Mild AD | II | [155] |

| 18 | Verubecestat | Oral | BACE1 inhibitor | Mild-Moderate AD | III | [156] |

| 19 | Hydralazine | Oral | Mitochondrial function SIRT1/SIRT5 axis and NRF2 signaling pathway (Neuroinflammation and Oxidative stress) | Mild-Moderate AD | III | [157] |

| 20 | NeuroEPO plus (NeuralCIM®) | Oral | Oxidative damage and neuroinflammation | Mild-Moderate AD | II-III | [158] |

| 21 | GRF6019 | IV | Neuroinflammation, cognition and synaptic plasticity | Severe AD | II | [159] |

| 22 | Semaglutide (glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist) | Oral | Neuroinflammation | Mild AD | III | [160] |

| 23 | Masitinib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor) | Oral | Neuroinflammation (Mast cells and Microglia)- Adjunct treatment | Mild to Moderate | III | [161] |

| 24 | AL002 (engineered, humanized monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody) | IV | Neuroinflammation (Microglia, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) agonistic) | Mild AD | I | [162, 163] |

While some act on tau, such as donanemab (The trailblazer-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial), which significantly slowed clinical progression at 76 weeks in those with low/medium tau and in the combined low/medium and high tau pathology population [149]. Similarly, gosuranemab had an acceptable safety profile and was generally well tolerated. At week 76, all doses caused significant reductions in the cerebrospinal fluid levels of unbound N-terminal tau compared to placebo [138]. Tilavonemab was generally well tolerated, although it did not demonstrate efficacy in treating patients with early AD. Thus, further investigation of tilavonemab in early AD is not warranted [143]. Some therapeutics target both proteostasis and inflammation, such as buntanetap, which was safe and well tolerated. Biomarker data during the trial indicated a trend in lowering the levels of neurotoxic proteins and inflammatory factors and improving axonal integrity and synaptic function in both AD and PD cohorts [164].

While some drugs, such as Tilavonemab, did not move further because of efficacy and toxicity, others have continued through various clinical trial phases and gotten approved, such as Aduhelm (aducanumab), which was approved using the accelerated approval pathway in 2021, lecanemab, approved in 2023, and Eli Lilly’s Kisunla (Donanemab), recently approved in 2024 [4]. It is important to highlight that most drugs in clinical trials target tau and/or A

A biomarker is an indicator considered for the evaluation of any normal biological as well as pathogenic processes and pharmacological effects of any therapy. In the case of AD, a biomarker can be used to assess the overall health and disease condition of aged patients [165]. An extracellular deposition of amyloid-

| Biomarkers | Source | References |

| A | Brain, CSF | [168] |

| pTau181 | Plasma | [169] |

| NF-L, p-tau181, and GFAP | Plasma, CSF | [170] |

| p-tau217 and p-tau217/A | Plasma | [171, 172] |

| EV S100A8 | Plasma | [173] |

| lncRNAs, BACE1-AS | Plasma | [174, 175] |

| A | Plasma | [176] |

NF-L, neurofilament light chain; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; lncRNAs, circulating long noncoding RNAs; BACE1-AS, BACE1-antisense; EV, extracellular vesicles.

Elevated pTau181 in the plasma identifies participants more likely to progress to AD [168] and is a suitable method for enrichment in AD clinical trials. A study by [169] showed CSF-soluble platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (sPDGFR

Circulating long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) might serve as biomarkers for different pathological conditions. BACE1-antisense (BACE1-AS) lncRNA is upregulated in the AD brain and might be detected in the bloodstream (Table 2). The BACE1-AS level was low in the pre-AD subgroup but was high in full-AD people compared to the healthy controls. Therefore, BACE1-AS lncRNA may discriminate pre-AD and healthy control (75% sensitivity and 100% specificity), full-AD and healthy control (68% sensitivity and 100% specificity), and pre-AD and full-AD subgroups (78% sensitivity and 100% specificity), highlighting its potential as a biomarker for AD development [173]. Also in agreement with the above data is the research that suggests lncRNA MALAT1 (CSF but not plasma lncRNA-MALAT1) targeted miR-125b as potential biomarkers for AD, as they could predict the MMSE score decline at 1, 2, and 3 years in AD patients [174].

Inflammatory cells have also been explored as possible biomarkers. FP40/FP42 and type 1 T-helper cells can accurately predict the pathological changes of late mild cognitive impairment [175] (Table 2). The inflammatory biomarker, GFAP, is a more sensitive marker of the inflammatory process in response to the A

AD is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder with complex pathogenic mechanisms that go far beyond amyloid-

Relying solely on targeting neuroinflammation is unlikely to resolve the underlying proteostasis dysregulation in AD. Rather, a combinatorial therapeutic strategy is required—one that addresses both neuroinflammatory responses and proteostatic collapse simultaneously. The development of preclinical models that more accurately reflect the human disease, especially in terms of inflammation-proteostasis interactions, remains a priority. Many current transgenic or knock-in models fail to capture the full scope of proteostasis disturbances and chronic inflammation seen in human AD brains, thereby limiting translational success.

Recent technological advances offer hope for overcoming these barriers. Tools such as single-cell RNA sequencing have revolutionized our ability to dissect cellular heterogeneity within the brain, especially among microglial subpopulations. These tools allow for the identification of disease-associated microglial states and the mapping of their transcriptional dynamics across disease stages. Additionally, organoid models of the human brain, particularly those incorporating immune components such as microglia, present promising platforms for studying drug responses in a more physiologically relevant context. The application of cerebral organoids, combined with advanced transcriptomics and proteomics, could pave the way for identifying more precise therapeutic targets and predicting human responses more effectively.

Current Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapies for AD—such as aducanumab, lecanemab, and donanemab—are largely focused on reducing A

There is growing consensus in the field that addressing multiple pathological pathways simultaneously—such as combining anti-inflammatory agents, proteostasis enhancers, mitochondrial stabilizers, and synaptic modulators—may produce synergistic effects and yield better clinical outcomes. The future of AD therapy will likely hinge on the integration of multi-target approaches tailored to disease stage and patient-specific pathophysiological profiles. Personalized medicine strategies, possibly guided by biomarkers of proteostasis and inflammation, hold promise in optimizing these combination therapies.

In conclusion, advancing AD treatment requires a paradigm shift toward holistic, multi-modal strategies that address the disease’s complex molecular underpinnings. This includes prioritizing research into proteostasis-inflammation crosstalk, investing in the development of more representative disease models, and embracing the power of emerging technologies in neuroscience. Only through such an integrative approach can we hope to develop effective therapies that not only delay disease progression but also improve the quality of life for patients across all stages of AD.

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; A

AP and HW designed the research work; AP wrote the first draft; HW edited the manuscript. AP made tables, and HW prepared figures. Both authors searched references. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the NIH/NIA RF1 AG072510. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIH.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Hongmin Wang is serving as one of the Editorial Board members of this journal. We declare that Hongmin Wang had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Gernot Riedel.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.