1 Department of Neurology, Waikato Hospital, 3204 Hamilton, New Zealand

2 Department of Medicine, University of Auckland, 1142 Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

Predictive processing asserts that the brain learns a generative model of the world, which it uses to make sensory-updated predictions about reality. While traditional views emphasize the cerebral cortex, prediction is a fundamental brain principle, which underscores the vital role of older subcortical structures. This review offers a framework for understanding the brain as an integrated system of semi-independent cortical and subcortical functional units that collectively enable predictive processing. The cerebral cortex is positioned as the primary driver of subconscious predictions, whereas the thalamus, hippocampal complex, amygdala, basal ganglia, and cerebellum contribute critical indirect roles by translating the predictions into conscious, cohesive, and coordinated experiences and behaviours. Specifically, the thalamus controls and establishes selective attention by synchronizing multiple cortical regions, enabling attended predictions to be expressed into conscious perception and cognition; the hippocampal complex captures novelty and constructs episodic simulations, which represent highly abstract or hypothetical predictions that contribute to the conscious cognitive experience; and the amygdala appraises motivational value and activates emotional states, which predict survival-critical events and prime the brain for action, contributing to a subjective emotional experience. During this translation, the basal ganglia and cerebellum contribute sculpting roles, with the basal ganglia chunking predictions into repertoires, facilitating the cohesive expression of actions, and potentially perceptual, cognitive, and emotional experiences, while the cerebellum generates and adjusts temporal predictions, enabling the coordinated expression of actions and experiences. This integrative framework highlights the essential, often-overlooked contributions of subcortical units to predictive processing, providing a unified model for future research.

Keywords

- cerebral cortex

- thalamus

- hippocampal complex

- amygdala

- basal ganglia

- cerebellum

- perception

- action

- cognition

- emotion

For over 2000 years, philosophers have contemplated that subconscious inferences underly human perception [1]. During the 19th century, Helmholtz advanced this idea by suggesting that much of visual perception consists of subconscious conclusions about the world, whereas many of the actual sensations, considered unimportant, are disregarded [2]. In the 20th century, Craik described the brain as an inference generator, viewing perception as a stream of sensory-updated “best guesses” about reality [3]. Later, Jaynes proposed that the brain employs a Bayesian approach to statistical inference [4]. Under this approach, the brain generates a set of beliefs (“prior” probabilities), which are updated by sensory information (“likelihoods”), the merging of which leads to a new, updated set of beliefs (“posterior” probabilities).

Predictive processing offers a plausible neurobiological mechanism for inference generation [5], asserting that the brain learns a generative model, based on statistical patterns previously detected in the world, to make predictions about reality [6, 7]. In other words, rather than passively reacting to its sensory inputs, the brain proactively anticipates these inputs by generating a constant stream of subconscious hypotheses, or “predictions”, about the sources of its sensations. These predictions are updated, modulated, and constrained (but not dictated) by the sensory data, and may be categorized as “exteroceptive”, concerning sensations from the external world, or “interoceptive”, pertaining to internal body states. The brain strives to minimize the difference between the sensory updates and the generated predictions, known as the “prediction error”. Predictions with the lowest prediction error are expressed into conscious awareness.

Traditional theories of “higher” brain functions typically emphasize the cerebral cortex [8], including perspectives on predictive processing [9, 10, 11]. Yet, prediction is a fundamental brain principle, evident in ancient predictive and error correction circuits that predate the cortex [12], which underscores the vital role of older, “lower” subcortical structures in predictive processing [8]. Some viewpoints recognize this, many of which suggest that structures such as the thalamus, hippocampal complex, amygdala, basal ganglia, and cerebellum directly participate in predictive processing, often through active inference [13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. Alternatively, it may be argued that while the cortex is primarily responsible for generating subconscious predictions, these subcortical structures are critical for “translating” predictions into conscious, cohesive, and coordinated experiences and behaviours, potentially (though not necessarily) engaging in other forms of predictive processing during this translation. The indirect contributions of these structures are less apparent, particularly when examined outside an integrative framework.

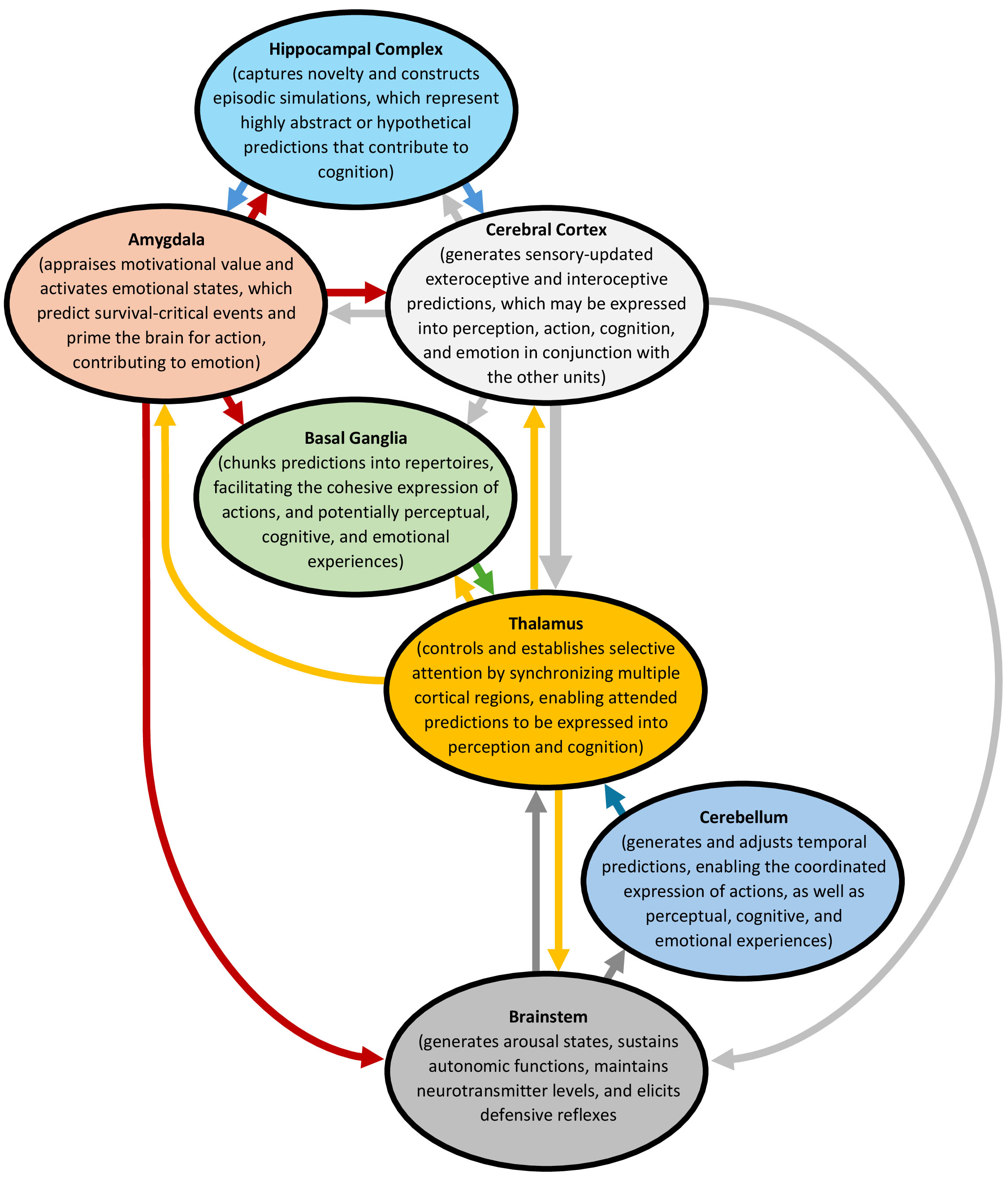

Accordingly, the brain can be viewed as an integrated system of semi-independent functional units, each of which contributes uniquely to predictive processing (Fig. 1). The cerebral cortex primarily drives this process by generating subconscious, sensory-updated predictions [18, 19]. However, the translation of these predictions into conscious perception, action, cognition, and emotion relies on specialized contributions from other units, as well as skeletal muscles and visceral processes. These collaborators include the thalamus, which controls and establishes attention, enabling states of thalamo-cortico-thalamic synchrony for the expression of conscious perception and cognition [20, 21]; the hippocampal complex, which captures novelty and constructs episodic simulations that represent highly abstract or hypothetical predictions, contributing to the conscious cognitive experience [22, 23]; and the amygdala, which appraises motivational value and activates emotional states that predict survival-critical events and prime the brain for action, contributing to a subjective emotional experience [24, 25]. During this translation, the basal ganglia and cerebellum contribute “sculpting” roles, with the basal ganglia chunking predictions into repertoires, facilitating the cohesive expression of actions, and potentially perceptual, cognitive, and emotional experiences [26], while the cerebellum generates and adjusts temporal predictions, enabling the coordinated expression of actions and experiences [27].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The integrative brain. The brain may be envisioned as an integrated system of semi-independent functional units, each contributing uniquely to predictive processing. The cerebral cortex drives this process by generating subconscious, sensory-updated predictions, whereas the translation of the predictions into conscious perception, action, cognition, and emotion relies on specialized contributions from other units. The figure was created using Microsoft Word 365 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA 98052, USA).

This review offers a framework for understanding the brain as an integrated system of semi-independent cortical and subcortical functional units that collectively enable predictive processing. The cerebral cortex is positioned as the primary driver of predictive processing, whereas the thalamus, hippocampal complex, amygdala, basal ganglia, and cerebellum provide critical, yet indirect, supportive and integrative roles. Drawing on over 50 years of neuroscience research, including experimental evidence and associated theories, this framework illustrates how these subcortical units facilitate the translation of subconscious predictions into conscious perception, action, cognition, and emotion. The proposed integrative framework highlights the essential, often-overlooked contributions of subcortical units to predictive processing, providing a unified model for future research.

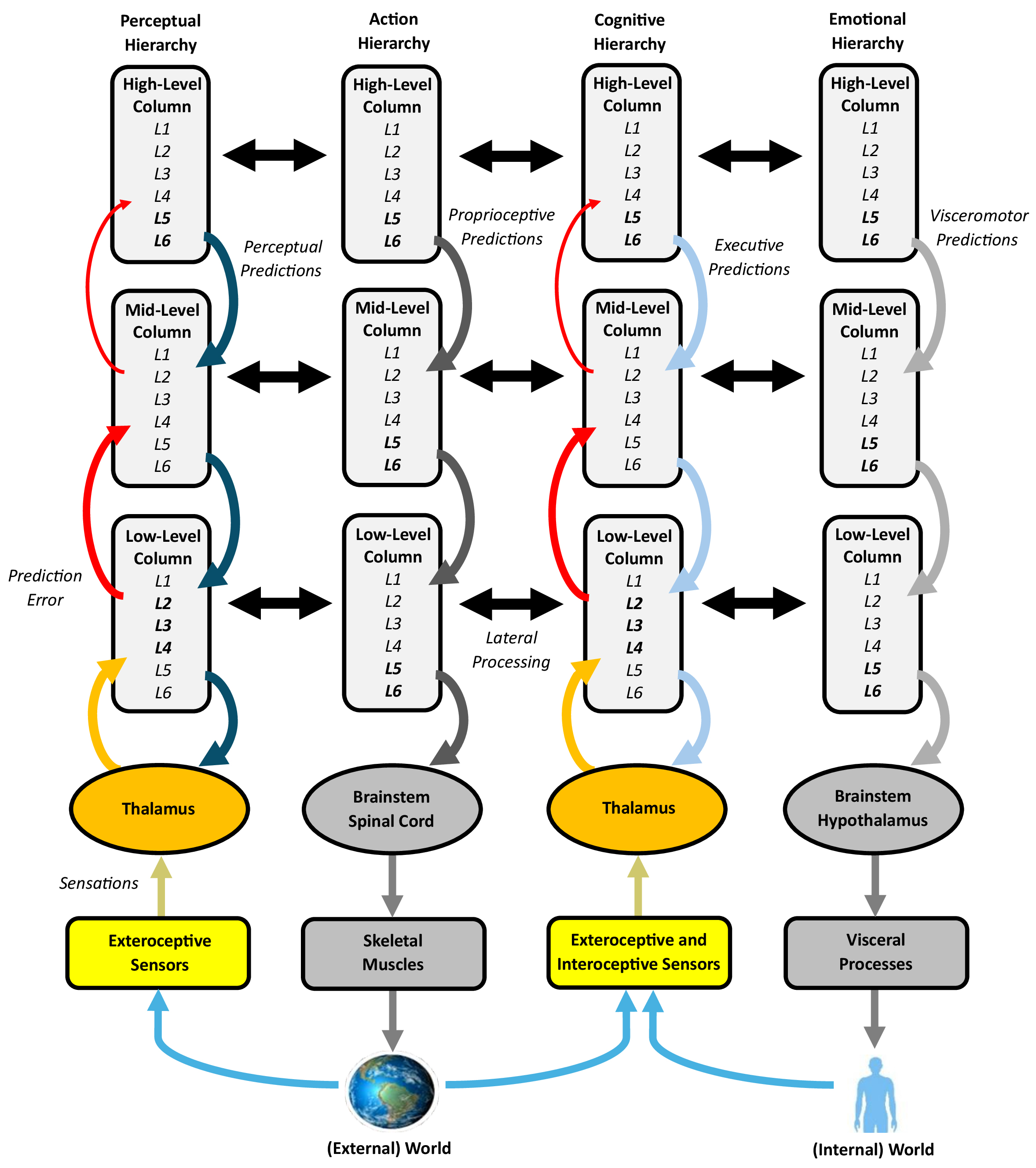

The cerebral cortex, as the core of predictive processing, generates sensory-updated exteroceptive predictions about the external world and interoceptive predictions about internal body states. These subconscious predictions may be expressed into conscious perception, action, cognition, and emotion in conjunction with other functional units, as well as skeletal muscles and visceral processes. Cortical processing occurs within the canonical circuitry of its “columns”, which are arranged into a series of processing hierarchies (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Processing in the cerebral cortex, with an emphasis on the columns and processing hierarchies. Cortical columns, based on their canonical circuitry, likely perform a common predictive processing operation, where deep layers of agranular, high-level columns primarily generate predictions (descending pathways) and superficial layers of granular, low-level columns handle the bulk of prediction error (ascending pathways). Variations in column granularity impact the vertical cortico-cortical projections (bolded layers and thicker arrows represent more well-developed layers and projections, respectively), forming a series of processing hierarchies that generate subconscious, sensory-updated exteroceptive and interoceptive predictions. The perceptual and cognitive hierarchies exhibit bidirectional processing, whereas the action and emotional hierarchies are largely unidirectional. The predictions issued by these various hierarchies may be expressed into conscious perception, action, cognition, and emotion in conjunction with other functional units, as well as skeletal muscles and visceral processes. Horizontal cortico-cortical projections engage in lateral processing, which plays a modulatory role. The figure was created using Microsoft Word 365. L1–6, Layers 1–6.

The cerebral cortex is a thin, folded layer of grey matter enveloping the outer brain [28]. Based on subtle differences in neural network, it can be divided into several dozen “Brodmann areas”, some of which are topographically arranged [29, 30]. Despite these variations, the cortex is also composed of around 150,000 structurally similar neural networks called columns, each of which is 1 mm2 in surface area, 2–4 mm in depth, and oriented perpendicularly to the cortical surface [31, 32]. These columns consist of approximately 80% excitatory neurons and 20% inhibitory neurons.

Most columns show a canonical six-layered circuitry (layers 1–6, or L1–6), which is replicated, with minor variations, throughout the cerebral cortex [33, 34, 35]. Many of the neurons within these layers share cortico-cortical projections with other columns, extending “vertically” (across layers) or “horizontally” (within layers) [36]. Neurons in the superficial layers (L1–3) contribute both vertical and horizontal projections, with the latter extending 2–5 mm parallel to the cortical surface and reciprocally connecting with neurons in local and distant columns, particularly those with similar response properties [37, 38]. The most superficial layer, L1, receives strong inputs from lower layers and the thalamus, while L2 and L3, driven by strong inputs from L4, dominate the horizontal projections. Conversely, neurons in the deep layers (L4–6) focus on the vertical projections and subcortical connections, especially with the thalamus. The “granular” layer, L4, integrates the inputs from the thalamus and other columns, then connects to L3 and L5. The next layer, L5, targets the thalamus, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and (via pyramidal tracts) brainstem and spinal cord. The deepest layer, L6, sends extensive outputs to the thalamus, with roughly ten cortico-thalamic projections for every thalamo-cortical projection.

Despite this “canonical” circuitry, column layers vary across the cerebral cortex, which influences the distribution of the vertical cortico-cortical projections [39]. Columns are classified as agranular (undifferentiated L2–3, no clear L4), dysgranular (poorly defined L4), or granular (distinct L2–3, clear L4) [40]. Agranular columns are prevalent in the limbic and paralimbic cortices, such as the perirhinal, parahippocampal, cingulate, and insular cortices [18], as well as the motor cortices, which display an especially prominent L5 [41]. Agranular columns send extensive vertical projections from their well-developed L5–6 layers to the superficial layers of dysgranular and granular columns [18, 42]. Granular columns, prevalent in the primary sensory cortices, relay numerous vertical projections from their well-differentiated L2–3 layers to the deep layers of dysgranular and agranular columns.

In a predictive processing framework, the cerebral cortex leverages learned sensory patterns to build a generative, memory-based model of statistical regularities in the world, which it uses to make inferences, or predictions [6, 7]. Given their canonical circuitry, columns are considered the fundamental processing elements of this model, each of which performs a common, massively-reiterated predictive operation [32, 33]. This operation may be speculated as follows [42, 43]. As sensory inputs are relayed through the thalamus to L4 of any number of columns, they are dispersed to update the other layers in those columns. At the same time, L5–6 neurons generate predictions to anticipate these inputs, while L1–3 neurons assess the degree of prediction error between predictions and updates, resulting in prediction error signals. If the prediction error is below a set physiological threshold, the sensory updates are “explained away” and replaced with predictions. Conversely, if the prediction error exceeds this threshold, further processing occurs, which either modifies the predictions, moves the body to alter the sensations, or changes how the sensations are attended. Based on this description, the cortex actively generates predictions about the world that strive to anticipate and replace the incoming sensations, but the predictions are constrained by prediction error, keeping them in check.

While predictive processing may be grounded in a common cortical operation, the observed differences in column granularity across different regions may also form a series of processing hierarchies that unite perception, action, cognition, and emotion [18]. According to this view, agranular columns in the prefrontal, limbic, and paralimbic cortices, at higher hierarchical levels, generate most of the predictions, whereas granular columns at lower levels handle the bulk of prediction error. Exteroceptive hierarchies generate predictions that drive perception and action, culminating in a “perception-action cycle” [44], while interoceptive hierarchies generate predictions that underpin cognition and emotion [45]. Default mode, executive control, and salience networks further support these processes in a domain-general manner [46, 47, 48].

Many posterior regions of the cerebral cortex may be organized into a sensory-based “perceptual hierarchy” of processing regions, which aims to model hierarchical patterns in the external world [44]. Columns in the visual, auditory, and somatosensory cortices are organized into processing levels based on their vertical cortico-cortical projections, forming “ascending” and “descending” processing pathways, while columns within levels are connected by horizontal projections comprising “lateral” processing pathways [36]. Studies in humans support a generative, hierarchical model of perceptual processing [49, 50, 51, 52]. Briefly, high-level agranular columns in the limbic and paralimbic cortices, which display extensive vertical L5–6 projections but no clear L4, generate transmodal predictions about complex features in the external world (such as objects and situations), whereas low-level granular columns in the primary sensory cortices generate unimodal predictions about simple features (such as colour and pitch) [42, 53]. As the predictions generated by columns at all levels flow down the processing hierarchy, they strive to anticipate and explain away the ascending exteroceptive sensory prediction error. High-level predictions are weakly constrained by prediction error due to a larger number of synapses between high-level columns and their sensory receptors, whereas low-level predictions are more tightly constrained. Moreover, at all levels, lateral processing may play a modulatory role by allowing predictions from more successful columns to expand at the cost of their neighbours [54]. According to this description, predictive processing in the perceptual hierarchy occurs bidirectionally, with higher levels generating most of the brain’s “perceptual” predictions, while lower levels process the exteroceptive sensory prediction error that constrains those predictions. The overall processing goal is to minimize this prediction error by either modifying the predictions or altering how the sensations are attended, enabling predictions with the lowest prediction error to be expressed, in conjunction with the thalamus, into conscious perception.

Beyond perception, the cerebral cortex may also feature a motor-based “action hierarchy” of processing regions, which models body movements [44]. Higher levels of this hierarchy, localized to the premotor and prefrontal cortices, generate complex movements, whereas lower-level primary motor cortices generate simpler movements. Long-standing evidence supports such a hierarchy [55, 56]. However, unlike the perceptual hierarchy, agranular columns are prevalent at every level of the action hierarchy, which suggests that processing is essentially unidirectional, characterized by cascades of predictions flowing down the hierarchy, but little (if any) prediction error flowing upwards [57, 58]. Given this variation, the action hierarchy may generate predictions that specify the desired proprioceptive “intentions” of an action, which are directly expressed by skeletal muscles into the act itself [59]. The ensuing “proprioceptive” predictions physically change the proprioceptive sensory inputs, thereby reducing any associated prediction error being simultaneously processed through the perceptual hierarchy. Based on this description, rather than modifying its predictions or altering its attention, the action hierarchy, working with skeletal muscles, moves the body to change the sensations, culminating in action.

Many anterior regions of the cerebral cortex may be loosely organized into an executive-based “cognitive hierarchy” of processing regions, which influences the other hierarchies at their highest levels [60]. Based on meta-analytic evidence, neuroimaging studies in humans demonstrate the existence of a “cognitive control network”, which generates a diverse range of executive functions, including initiation, inhibition, cognitive flexibility, abstraction, long-term planning, and working memory [61]. This network may be largely characterized by a hierarchical cascade of executive processes across the prefrontal cortex [62]. Specifically, rostral regions of the prefrontal cortex process abstract concepts critical for higher cognitive control, while caudal regions focus on contextual information [63]. The mid-lateral prefrontal cortex, which integrates the data processed by the rostral and caudal regions, may serve as the apex of the hierarchy [64]. Given the highly integrative nature of the prefrontal cortex, the cognitive hierarchy would be expected to heavily utilize lateral processing, particularly for working memory. Within a predictive processing framework, the higher levels of this hierarchy generate “executive” predictions, which are constrained by exteroceptive and interoceptive sensory prediction error and expressed, in conjunction with the thalamus, into conscious cognition, with contributions from the hippocampal complex.

Emotional development involves a progressive shift from subcortical to cortical circuits [65], which may form a crude “emotional hierarchy” of processing regions. While various brain networks activate during a range of subjective emotions, each with a semi-distinct neural signature [66], neuroimaging studies consistently highlight activation in the prefrontal, cingulate, and insular cortices during emotional expression [42, 67], possibly within an emotional hierarchy. The anterior insula, which integrates cognitive and affective processes [68], may sit atop the hierarchy. In a predictive processing framework, agranular columns in the prefrontal, cingulate, and insular cortices generate “visceromotor” predictions, which orchestrate autonomic, hormonal, immunological, and metabolic body processes to sustain energy regulation in an anticipatory or “allostatic” manner [42, 48]. These predictions are thought to be minimally constrained by vagus nerve prediction error, suggesting that processing is primarily unidirectional, with the predictions mostly converted directly into the desired allostatic adjustments. Through these visceral processes and contributions from the amygdala, visceromotor predictions may be experienced as subjective emotions, which serve as conscious reflections of the content of the predictions and their expected allostatic impact on the body [19].

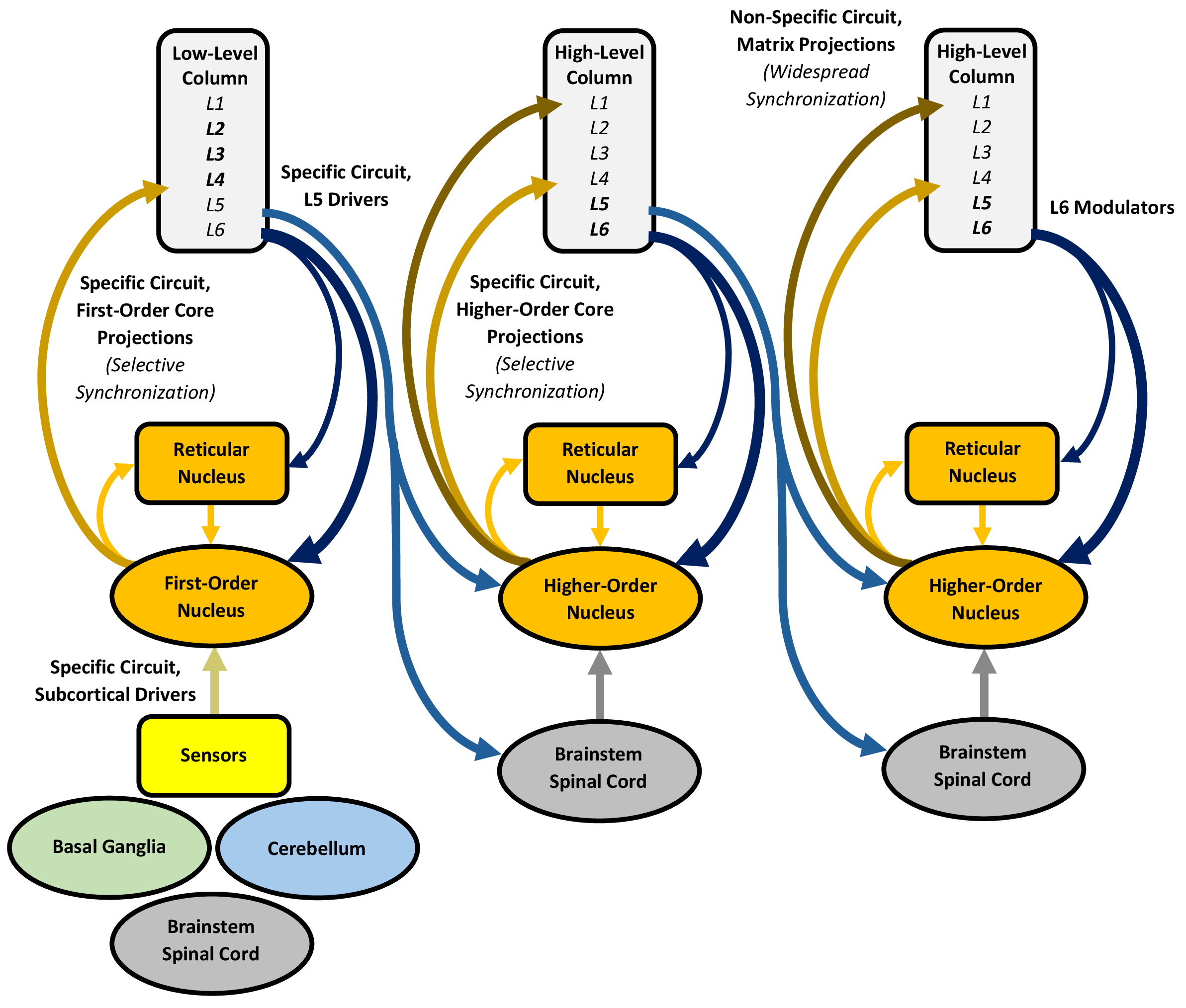

Given its central position and extensive reciprocal connectivity with the cerebral cortex, the thalamus likely plays a crucial role in controlling and establishing selective attention by synchronizing activity across multiple, separate cortical regions. This synchronization allows attended predictions to be expressed into conscious perception and cognition. Thalamic processing depends on its diverse nuclei, which participate in “specific” and “non-specific” thalamo-cortico-thalamic circuits (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Processing in the thalamus, with an emphasis on the specific and non-specific circuits. The specific circuit proceeds through drivers and core projections, giving rise to a trans-thalamic pathway that links multiple, spatially distinct regions of the cerebral cortex, whereas the non-specific circuit proceeds through the more diffuse matrix projections (in the columns, bolding represents more well-developed layers). Both circuits are influenced by enormous numbers of modulators. The reticular nucleus controls selective attention by inhibiting the other thalamic nuclei, relaxing this inhibition for novel or motivational information, including predictions, to establish selective attention. Enhanced activity in the specific circuit selectively synchronizes multiple, separate cortical regions at local and long-range scales, whereas non-specific circuit activity promotes widespread cortical synchronization. The ensuing thalamo-cortico-thalamic synchrony may serve as the primary physiological basis for expressing predictions into conscious perception and cognition, with gamma synchrony binding and expressing the predictions of the activated columns into a conscious, unified experience, modulated by lower-frequency synchrony. The figure was created using Microsoft Word 365.

The thalamus consists of several dozen nuclei, categorized as “first-order” or “higher-order” [69, 70]. First-order nuclei receive inputs from various sensors as well as the basal ganglia, cerebellum, brainstem, and L6 of the cerebral cortex. These nuclei contain two types of excitatory neurons with inherent oscillatory properties, including “core” neurons, which project in a topographic, spatially segmented manner to L4 of the cortex, and “matrix” neurons, projecting more diffusely to L1 and the basal ganglia striatum [71]. Conversely, higher-order nuclei, comprising the majority of the thalamus, primarily receive inputs from L5–6 of the cortex and feature many matrix neurons with diffuse projections, as seen in the intralaminar nuclei [72]. Beyond this categorization is the reticular nucleus, a thin inhibitory shell surrounding the main body of the thalamus, which is extensively innervated by L6 of the cortex and linked to all the other nuclei.

The thalamus and cerebral cortex are connected through thalamo-cortico-thalamic circuits, which may be divided into specific and non-specific circuits [21, 73, 74]. Both circuits involve “driver” and “modulator” inputs [75], as well as core and matrix neuron outputs [71]. In the specific circuit, subcortical drivers relay sensory and subcortical inputs to a first-order thalamic nucleus, which forwards its core projections to L4 of an ensemble of modality-related, low-level cortical columns. These columns forward their L5 drivers to a modality-related, higher-order nucleus, which then forwards its core projections to L4 of multiple high-level column ensembles. Importantly, the higher-order nuclei form a “trans-thalamic pathway”, which links multiple, spatially distinct regions of cortex, providing an adjacent route to the more direct cortico-cortical projections that link those regions [76, 77]. Conversely, the non-specific circuit features matrix projections that extend more diffusely from higher-order nuclei to L1 and the striatum. Although termed non-specific, this circuit is not entirely indiscriminate, as even the widespread intralaminar projections preferentially target certain cortical regions [78]. Both specific and non-specific circuits are influenced by enormous numbers of L6 modulators, which project from the cortex to all thalamic nuclei.

Selective attention may be conceptualized as a “spotlight”, which illuminates specific information for intensified processing while filtering out unwanted stimuli [79, 80]. This spotlight can highlight exteroceptive sensory data from the external world or interoceptive data pertaining to internal processes, such as working memory and subjective emotion [81]. The reticular nucleus, based on its position and physiological properties, is considered the primary facilitator of the attentional spotlight, positioning it to play a powerful role in attentional control [82, 83]. In theory, when exposed to novel or motivational information, including predictions, the reticular nucleus relaxes its inhibition over select first-order and higher-order nuclei, triggering rapid firing in specific neural subgroups [79]. In the specific circuit, these nuclei, through the trans-thalamic pathway, drive excitatory responses across multiple, separate cortical regions, promoting oscillatory coupling that selectively “synchronizes” their processing of the attended information at local and long-range scales [84]. Concurrently, higher-order nuclei in the non-specific circuit support more widespread cortical synchronization [85]. Synchronized activity in the gamma range (typically, 30–80 Hz) enhances processing efficiency for the attended information [20, 86], whereas alpha range frequencies are linked to inattention, indicating a role in suppressing less relevant data [87, 88]. Attended sensory and predictive information is primed for expression into perception and cognition.

Although there is evidence suggesting that synchronized processing, driven partly by cortico-cortical projections, underpins perception and cognition [89, 90], clinical data emphasize that the thalamo-cortico-thalamic circuits primarily orchestrate this expression [21, 74]. Functionally, the thalamus includes intralaminar, reticular, sensory, motor, associative, and limbic nuclei [91], with lesions in these nuclei leading to “cortical” clinical deficits that mimic cortical damage. For example, lesions involving the intralaminar or reticular nuclei impair arousal and complex attention, sensory nuclei lesions disrupt modality-specific perception, and associative nuclei lesions affect cognitive processes [91, 92, 93]. Since the cortex remains intact, the clinical deficits likely stem from disrupted thalamo-cortico-thalamic synchrony, underscoring its vital role in conscious perception and cognition [20, 21].

The fractured nature of sensory representation across the cerebral cortex raises the question of how information, including exteroceptive predictions, can be unified into a single perceptual experience [89, 90, 94]. Gamma synchrony in the thalamo-cortico-thalamic circuits has been proposed to subserve this expression by temporally “binding” the activities of relevant columns, enabling unified perception [21]. Through specific and non-specific circuits, higher-order sensory nuclei can activate L4 and L1 of the sensory cortices simultaneously, which enables these inputs to be integrated at the apical dendrites of L5–6 neurons [74]. Since these deep layers likely generate most of the brain’s predictions, this temporal integration may provide a foundation for gamma synchrony and the emergence of a unified perceptual experience, which can be supported by any number of columns. Human studies confirm that perceived stimuli elicit gamma synchrony in the visual, auditory, and somatosensory cortices [95, 96, 97], whereas unperceived stimuli do not. Importantly, lower synchronization frequencies, such as beta synchrony in primate visual cortices [98, 99], potentially modulate this gamma synchrony during perception [84], while pulvinar-driven alpha synchrony “gates” sensory processing by prioritizing representations from task-relevant regions and suppressing irrelevant ones [88, 100, 101, 102].

Thalamo-cortico-thalamic gamma synchrony may also subserve as a physiological basis for expressing information, including interoceptive predictions, into higher cognitive experiences [20]. Sustained gamma synchrony has been demonstrated in non-sensory cortical regions, especially during memory tasks [103, 104]. Several prominent thalamic nuclei may sustain gamma synchrony with the prefrontal cortex, modulated by lower oscillatory frequencies during cognition [105]. For instance, the medial dorsal nucleus, heavily connected to the prefrontal cortex [106], exhibits enhanced gamma and beta synchrony during cognitive tasks, such as working memory [106, 107, 108]. Lesions of this nucleus induce “prefrontal” symptoms, including impaired executive functions [109, 110]. These findings suggest that beta-coupled gamma synchrony between the medial dorsal nucleus and prefrontal cortex supports working memory expression [111, 112]. Similarly, the anterior nucleus, linked to the prefrontal cortex and hippocampal complex [113], shows enhanced gamma and theta synchrony during episodic memory encoding and retrieval [114]. Lesions of this nucleus can impair recollection [115]. These findings indicate that theta-coupled gamma synchrony between the anterior nucleus, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal complex underlies episodic memory expression [116]. Like perception, pulvinar-driven alpha synchrony across the prefrontal cortex may support cognitive control by gating irrelevant or contradictory representations during working and episodic memory tasks [117, 118, 119].

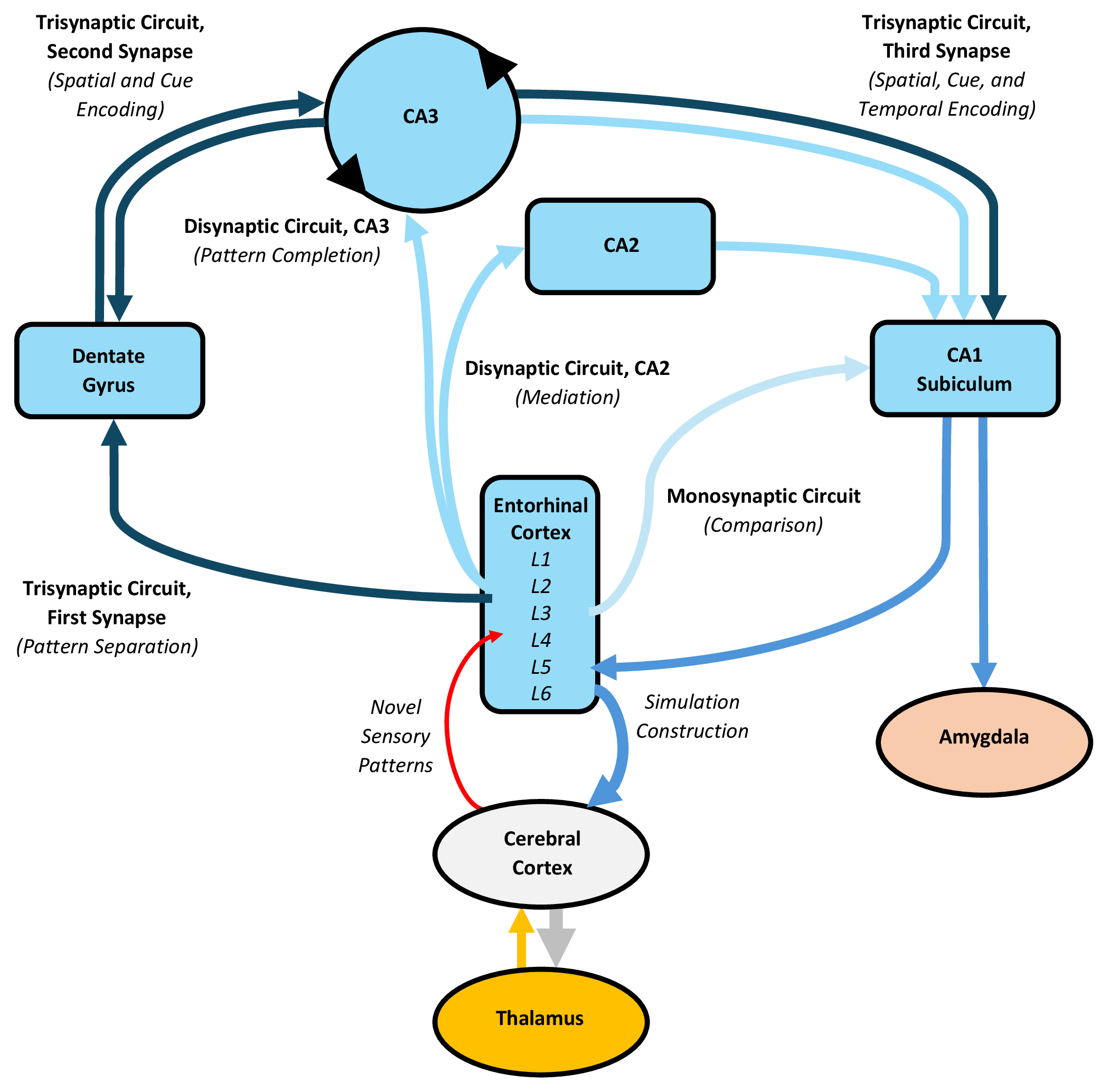

The hippocampal complex likely engages in an alternative form of predictive processing by capturing novelty and constructing episodic simulations, which represent highly abstract or hypothetical predictions that contribute to the conscious cognitive experience. Its processing relies on distinct subdivisions that engage in the classic “trisynaptic” cortico-hippocampal-cortical circuit, as well as lesser-known “disynaptic” and “monosynaptic” circuits (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Processing in the hippocampal complex, with an emphasis on the trisynaptic, disynaptic, and monosynaptic circuits. The trisynaptic circuit connects the entorhinal cortex to the dentate gyrus, then to CA3, and finally to CA1, while the two disynaptic circuits project to either CA3 or CA2 before reaching CA1, and the monosynaptic circuit directly targets CA1 and the subiculum. Following predictive processing, the trisynaptic circuit may capture residual prediction error, representing novel sensory patterns, commencing with pattern separation in the dentate gyrus. Subsequently, neurons in CA3, CA1, the subiculum, and entorhinal cortex encode spatial, contextual, and temporal patterns of interest. The hippocampal complex can also switch from encoding to retrieval, reassembling encoded information with consolidated cortical memories. This process additionally involves the disynaptic circuit through CA3, which completes the encoded memory trace and forwards it to CA1, after which back-projections to the entorhinal cortex may retrieve and integrate consolidated cortical memories into the trace, culminating in constructed episodic simulations. These constructed simulations represent highly abstract or hypothetical predictions, which contribute to conscious cognition. The disynaptic circuit through CA2 likely mediates this construction, while the monosynaptic circuit enables CA1 to compare its contents with cortical inputs and detect prediction error. The figure was created using Microsoft Word 365. CA1–3, Cornu ammonis 1–3.

The hippocampal complex, encompassing the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, operates as a distinct functional unit [120]. The hippocampus can be subdivided into the dentate gyrus, cornu ammonis fields 1–3 (CA1–3), and subiculum [121, 122]. The dentate gyrus primarily contains granule cells that exhibit lifelong neurogenesis [123, 124]. CA3 features pyramidal neurons that make numerous excitatory synapses upon each other, forming an intrinsically “recurrent” CA3-CA3 network [125]. CA2 consists of pyramidal neurons with unique physiological properties and is positioned to influence CA3 and CA1 activity [126]. CA1 has pyramidal neurons that project to the subiculum, which houses both pyramidal and “ovoid” neurons, the latter displaying distinct connectivity and physiological properties [127]. Each subdivision connects with the entorhinal cortex, which serves as a hub linking the hippocampus to various transmodal cortical areas, including the prefrontal, limbic, and paralimbic cortices [128].

The cerebral cortex and hippocampal complex are connected through cortico-hippocampal-cortical circuits [120, 129]. The classic trisynaptic circuit involves pyramidal projections from L2 of the entorhinal cortex to the dentate gyrus (first synapse), mossy fibers from the dentate gyrus to CA3 (second synapse), and Schaffer collaterals from CA3 to CA1 (third synapse). Notably, the entorhinal cortex L2 neurons extend to approximately 15 times as many dentate gyrus granule cells [130]. There are two disynaptic circuits, composed of connections from L2 of the entorhinal cortex to either CA3 or CA2 (first synapse), followed by CA1 (second synapse). Importantly, the disynaptic circuit through CA2 constitutes a powerful, highly plastic link between the entorhinal cortex and CA1 [131]. The monosynaptic circuit projects directly from L3 of the entorhinal cortex to CA1 and the subiculum. All circuits converge in the subiculum, which connects to L5–6 of the entorhinal cortex and the amygdala.

Due to its prominent connections with the prefrontal, limbic, and paralimbic cortices, the hippocampal complex is situated at the apex of the perceptual hierarchy [36], positioning it to handle residual prediction error that predictive processing cannot resolve [132]. Much of this residual prediction error contains novel sensory patterns, which are often unfamiliar, or familiar in new arrangements [133], that can be captured or “encoded” into temporary memory traces mediated by changes in long-term potentiation and depression [134, 135, 136]. Encoding is thought to commence in the trisynaptic circuit, where novel patterns converge upon the entorhinal cortex and are relayed to the dentate gyrus, which utilizes its abundant granule cells to isolate or “separate” specific patterns [137]. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus allows overwriting of old patterns with new ones [138]. Newly separated patterns are relayed to CA3, where pyramidal neurons encode spatial and non-spatial environmental features [139], including “place cells” for spatial maps of the environment [140], as well as “cue cells” for contextual details such as odour and touch [141, 142, 143]. Given its recurrent connectivity, the CA3-CA3 network may support “autoassociative” encoding, which enables rapid, one-trial learning between neurons that share different patterns of the same memory, allowing CA3 to store a large number of autoassociative memories [125, 144]. CA3 outputs are relayed to CA1, which also encodes spatial and non-spatial patterns [139], with “time cells” encoding how multi-episodic experiences are temporally organized [145, 146]. CA1 is tightly linked with the subiculum and its ovoid neurons, which appear specialized for encoding novel, non-spatial sensory patterns [127]. Outputs from CA1 and the subiculum return to the entorhinal cortex, which contains specialized grid, border, and head direction cells encoding location, boundaries, and direction [147, 148, 149]. Across weeks to months, the entorhinal cortex utilizes cortical projections to reorganize and “consolidate” novel encoded memory traces within the cerebral cortex [144, 150]. Once integrated into the generative model, these learned sensory patterns, now consolidated memories, can be leveraged to make predictions and construct simulations.

Studies of memory suggest that the hippocampal complex can switch between encoding and retrieval modes [134, 151]. While retrieval is often considered a recollective activity, human evidence shows that recalling the past and imagining the future share similar processes, indicating a common, fundamentally “constructive” physiological substrate [152]. Neuroimaging supports this, revealing that both recollection and imagination engage a common neural system involving the hippocampal complex working in conjunction with a core cortical network [23, 153]. Moreover, bilateral hippocampal lesions profoundly impair the ability to recollect the past as well as imagine the future, reinforcing this shared system [154, 155, 156]. Collectively, these findings imply that the hippocampal complex and cortex work in concert to construct episodic memories, which may be applicable to both past and future events [155]. This constructive process lends itself to the flexible reassembly of past experiences into consciously expressed, “simulated” experiences [22]. Consequently, it supports a markedly conjectural form of predictive processing, where constructed episodic simulations represent highly abstract or hypothetical predictions, useful in novel circumstances [23], or when sensory data is absent [132, 153].

For nearly a century, recollection has been recognized as a constructive process [157], but the specific role of the hippocampal complex in this process continues to be debated [138]. As stated, episodic memory retrieval relies on both the hippocampal complex and cerebral cortex, which collaborate to reassemble memories consolidated in the cortex [158]. However, several theories suggest that the hippocampus permanently stores its own memories, which may be used to retrieve cortical memories using tracing or indexing mechanisms [159, 160]. These proposals are supported by studies that show hippocampal lesions impair memories of any age [161, 162]. However, other studies imply a time-limited role for the hippocampus in memory storage [163, 164, 165]. To reconcile these findings, it has been proposed that the hippocampus may serve as a “template” for constructing both encoded and consolidated memory elements into episodic memories [166]. While its original, encoded memory traces would decay over time, limiting their storage, the template function would allow the ongoing retrieval and reassembly of cortical memories [138]. According to this view, damage to the hippocampal complex could disrupt recent memories by damaging the encoded traces, but it could also disrupt remote memories (and constructed simulations in general) by damaging the template.

Based on this template mechanism, episodic simulation construction may rely minimally on encoded hippocampal memory elements and primarily on the retrieval of consolidated cortical memories, which most likely requires contributions from cortico-hippocampal-cortical circuits outside the trisynaptic pathway [129]. This process can be speculated as follows. Given its connectivity, the disynaptic circuit through CA3 leverages the autoassociative CA3-CA3 network to “complete” an encoded memory trace by sourcing its missing elements from other subdivisions of the hippocampal complex [137]. This completed memory trace is recoded in CA1 and relayed through “back-projections” to the entorhinal cortex, where it may serve as an efficient retrieval signal to recall and integrate transmodal cortical memories into the trace, culminating in constructed episodic simulations [167, 168], which represent highly abstract or hypothetical predictions. The disynaptic circuit through CA2, positioned to coordinate information routing between the entorhinal cortex and CA1 [129, 131], likely plays a key role in mediating this construction. Finally, the monosynaptic circuit positions CA1 to compare its contents with cortical perceptual inputs, indicating a potential role for CA1 in detecting simulation prediction error [169, 170].

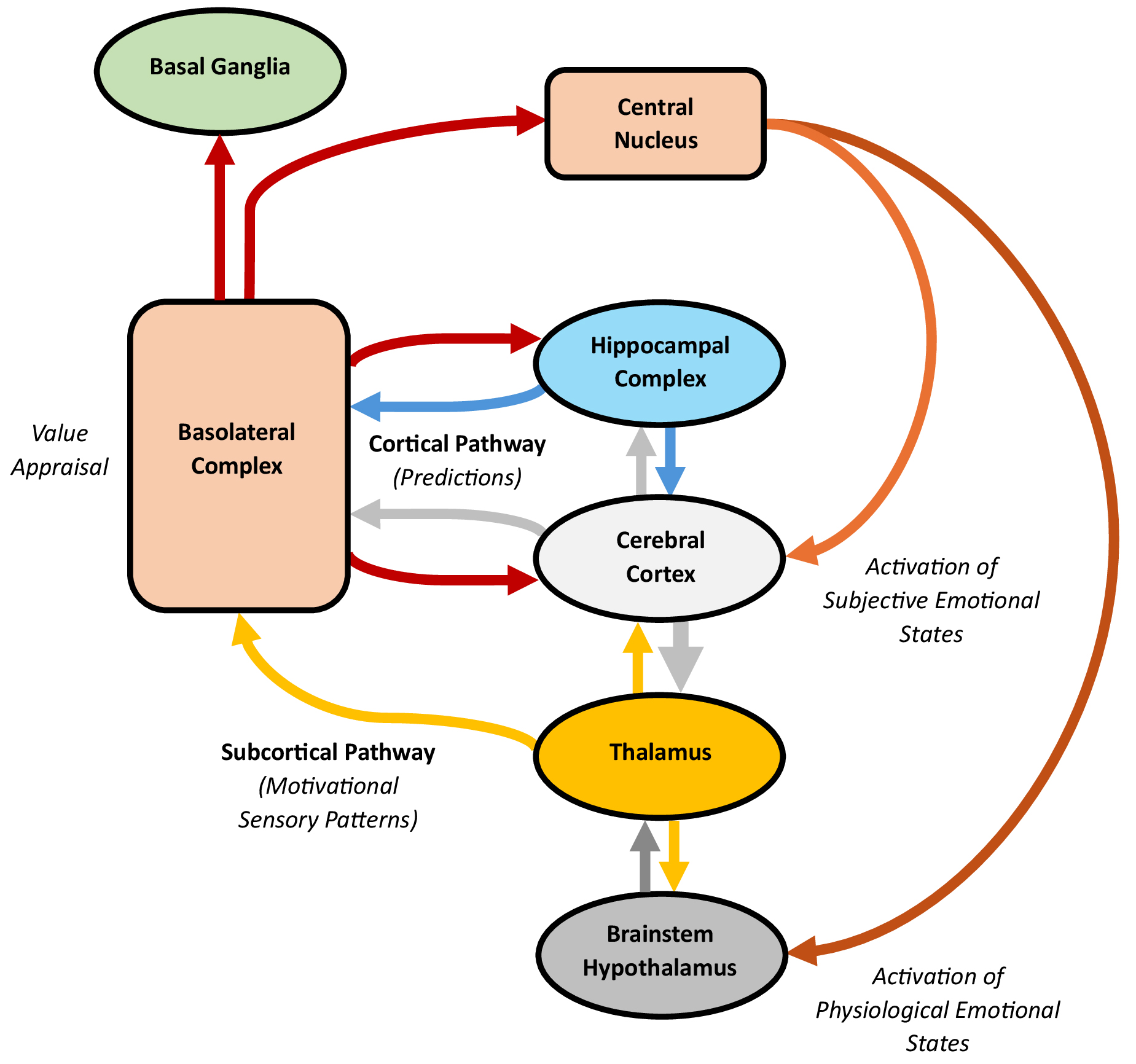

Though its precise role in emotion is still debated, the amygdala influences predictive processing by appraising motivational value and activating emotional states, which predict survival-critical events and prime the brain for action, contributing to a subjective emotional experience. Amygdala processing depends on distinct nuclei involved in “subcortical” and “cortical” pathways (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Processing in the amygdala, with an emphasis on the subcortical and cortical pathways. The subcortical pathway travels through the brainstem and thalamus to the basolateral complex, whereas the cortical pathway runs through the cerebral cortex to the same complex. Both pathways send outputs to the central nucleus, which can stimulate the brainstem, hypothalamus, and cortex. The basolateral complex likely monitors and appraises the motivational value of exteroceptive and interoceptive stimuli, quickly signalling other functional units about threats or rewards. This value appraisal leads the amygdala to activate emotional states, which predict survival-critical events and prime the brain for action. Through the subcortical pathway, the basolateral complex can trigger the central nucleus to activate physiological emotional states and, less consistently, subjective emotions. Through the cortical pathway, cortical modulation can refine or dampen these initial physiological responses, including any associated subjective emotions. Additionally, the basolateral complex is well-positioned to appraise the motivational value of emotionally salient cortical predictions, supporting parallel roles in regulating social interactions, decision-making, and memory. The figure was created using Microsoft Word 365.

The amygdala contains over a dozen nuclei, with the lateral, basal, accessory, and central nuclei being the most prominent [171, 172, 173]. Collectively, the lateral, basal, and accessory nuclei form the “basolateral complex”, the major input region to the amygdala, which receives signals from the cerebral cortex, thalamus, and hippocampal complex. Since it contains pyramidal and non-pyramidal neurons resembling those of the cortex, the basolateral complex is considered cortex-like [174, 175]. It projects predominantly unidirectionally to the other amygdaloid nuclei, with minor reciprocal projections [173], and extensively to the prefrontal, cingulate, and insular cortices [24], hippocampal complex [176], and basal ganglia striatum [177]. Conversely, the central nucleus, the main output region, displays a striatal-like architecture [178]. It connects to the brainstem and hypothalamus, controlling these structures to stimulate sympathetic and attention processes [179], and to the basal forebrain, which influences arousal and attention through widespread projections across the cortex [180, 181].

The amygdala may be activated through either subcortical or cortical pathways [182, 183]. The subcortical pathway, projecting from sensory receptors through the midbrain, sensory thalamus, and basolateral complex, can stimulate autonomic and conditioned emotional responses [184]. This pathway is capable of activating the amygdala even after a sensory stimulus is presented so quickly that it is not consciously detected, as seen in “blindsight” [185, 186]. The subcortical pathway can activate the amygdala within 40–140 ms after a sensory stimulus is presented, whereas the slower cortical pathway, which involves additional processing by the cerebral cortex, activates the amygdala within 280–410 ms [187]. However, unlike the subcortical pathway, the cortical pathway supports conscious processing [182].

Human neuroimaging evidence shows that the amygdala reliably activates to motivationally significant sensory patterns predictive of biologically important events in the environment, such as threats or rewards [25]. This activation occurs in the basolateral complex, which may encode a representation of the motivational importance or “value” of these patterns [24, 188]. This representation enables the basolateral complex to subconsciously monitor and appraise the value of stimuli, even without conscious perception [189, 190], along dimensions such as polarity, magnitude, and location. For polarity, the basolateral complex divides into two roughly equal neuronal populations encoding negative or positive stimulus value [191], which gives rise to opposing “aversive” (withdrawing, protecting) and “appetitive” (consuming, nurturing) systems [192]. It also appraises the magnitude of stimulus value, particularly for ambiguous or unpredicted stimuli [193]. Moreover, the basolateral complex enhances spatial attention to locate stimuli predictive of threats or rewards [194]. Beyond external stimuli, value appraisal likely extends to internal processes, including executive rules and visceromotor impulses, such as hunger and satiation [188]. Altogether, these findings indicate the amygdala operates as a “vigilance system”, which subconsciously monitors and rapidly appraises the value of exteroceptive and interoceptive information [25], including predictions, enabling it to alert other functional units of the brain to the nature and location of threats and rewards. Once appraised, sensory and predictive information with strong motivational value can spark the activation of emotional states that predict survival-critical events.

After value appraisal, the basolateral complex sends outputs to the central nucleus, stimulating the brainstem, hypothalamus, and cerebral cortex to activate emotional states [179]. These states may be characterized by changes in physiology, subjective affect, or both. The subcortical pathway enables the amygdala to activate subconscious physiological emotional states marked by autonomic and neurotransmitter adaptations, defensive reflexes, and heightened attention [195]. Additionally, this pathway can, peripherally or indirectly, evoke subjective emotions, which serve as conscious reflections that guide survival-related decisions and actions, particularly in ambiguous or complex situations [24, 196]. The cortical pathway, by contrast, provides a way for cortical information to modulate the subcortically-activated emotional states [182]. Hypothetically, it can also enable the amygdala to appraise the cortical inputs, influencing the cortex through return projections. Both physiological and subjective emotional states may function as “action dispositions”, predicting events important for immediate or long-term survival and preparing the brain to act accordingly [192].

A wealth of raw, primal sensory data is transmitted to the amygdala through the subcortical pathway [182], activating physiological emotional states and, less reliably, subjective emotions. When a potential threat or reward is detected, the basolateral complex stimulates the central nucleus, which engages the brainstem and hypothalamus to drive autonomic adaptations, such as changes in heart rate [197]. The central nucleus also projects to many brainstem nuclei, including the ventral tegmental area, substantia nigra, locus coeruleus, and raphe nuclei, influencing the release of dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin [179]. Additionally, it can prompt defensive reflexes, including freezing, startle, or orienting responses [171]. The central nucleus may further stimulate the nucleus basalis in the basal forebrain, releasing acetylcholine across the cerebral cortex to sharpen attention towards motivationally significant stimuli [24]. Collectively, these physiological changes enable the brain to quickly predict and prepare for action when faced with potential threats or rewards. However, while the amygdala robustly activates physiological emotional states, stimulation of the amygdala inconsistently (or even rarely) elicits subjective emotional responses, possibly excepting fear and anxiety [197, 198, 199]. Studies of individuals with bilateral amygdala lesions, who often report ongoing subjective emotional experiences, reinforce this [200, 201]. Altogether, these findings suggest that the amygdala primarily drives physiological responses but can, in specific contexts, activate subjective emotions, likely in concert with the cerebral cortex [42, 67].

While abundant cortical information reaches the amygdala through the cortical pathway, the amygdala also sends projections back to many higher-level regions of the cerebral cortex, indicating bidirectional communication between these functional units. Following the rapid subcortical activation of the amygdala, which enables quick responses to potential threats or rewards, the slower cortical pathway may allow processed information from the cortex and hippocampal complex to refine or dampen the initial physiological response, including any associated subjective emotions, such as fear [182]. Hypothetically, within a predictive processing framework, the cortical pathway could also enable the basolateral complex to appraise the content of emotionally salient cortical predictions, subsequently influencing the prefrontal, cingulate, and insular cortices, hippocampal complex, and striatum through its return projections. This interaction may support “parallel roles” for the amygdala beyond activating emotional states, such as regulating social interactions, decision-making, and memory [183]. For instance, human studies show that the amygdala activates to a diverse range of social stimuli [202, 203, 204], and bilateral amygdala damage often impairs the ability to interpret facial expressions, hindering social interactions [204, 205]. The amygdala also influences decision-making [206, 207], with damage disrupting executive function and judgement [208, 209]. Moreover, it supports the encoding and consolidation of emotional events across the cortex, hippocampal complex, and striatum [210, 211, 212].

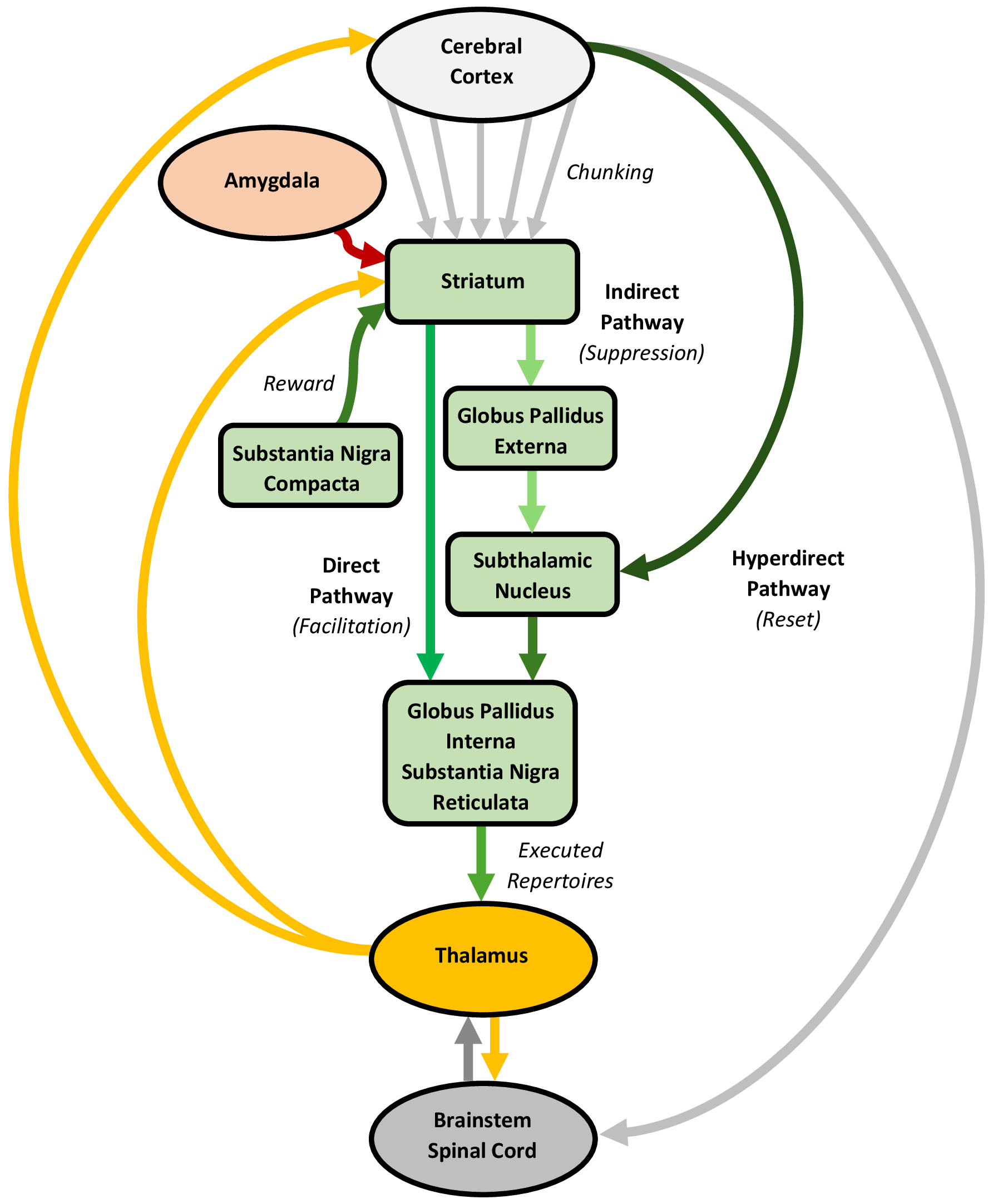

Rather than contributing to the content of actions and experiences, the basal ganglia likely plays a sculpting role in cortical predictive processing by chunking predictions into coherent repertoires, facilitating the cohesive expression of actions and possibly supporting perceptual, cognitive, and emotional experiences. Its processing relies on cortico-basal ganglia-thalamic circuits, involving “direct”, “indirect”, and “hyperdirect” pathways (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Processing in the basal ganglia, with an emphasis on the direct, indirect, and hyperdirect pathways. The cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus, and amygdala are connected through circuits involving direct, indirect, and hyperdirect pathways. These circuits likely learn purposeful and habitual actions through a striatal chunking process, which integrates and converts action signals, including proprioceptive predictions, into cohesive repertoires. Chunking allows complex actions to be stored as single units, facilitating their cohesive expression with minimal conscious oversight. The selective execution of these action (and potentially, experience) repertoires involves a co-mobilization of the direct and indirect pathways, regulated by a dopamine reward signal. The direct pathway facilitates the execution of specific action repertoires, whereas the indirect pathway suppresses irrelevant actions. The hyperdirect pathway likely serves as a global reset, halting ongoing actions to enable repertoire switching. The figure was created using Microsoft Word 365.

The basal ganglia consists of input, intrinsic, and output nuclei spread across four subdivisions known as the striatum, globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, and substantia nigra [213, 214]. The striatum, the primary input region, may be subdivided into a “limbic” ventral region (centered on the nucleus accumbens), an “associative” dorsomedial region (centered on the caudate nucleus), and a “sensorimotor” dorsolateral region (centered on the putamen) [215]. The striatum integrates topographic inputs from nearly the entire cerebral cortex, alongside dopaminergic inputs from the substantia nigra compacta, thalamus, and amygdala [216, 217, 218]. Approximately 90% of striatal neurons are spiny neurons that project, directly or indirectly, to other subdivisions [214, 216], while the remaining 10% are interneurons, which can powerfully inhibit the spiny neurons [219]. The “direct” spiny neurons target the basal ganglia output subdivisions, the globus pallidus interna and substantia nigra reticulata, whereas “indirect” spiny neurons connect to the globus pallidus externa and subthalamic nucleus, which then link to the output subdivisions. The direct and indirect spiny neurons exhibit distinct physiological properties and dopamine receptors, with dopamine stimulating the former and inhibiting the latter [220, 221]. Additionally, while the striatum serves as the main input hub to the basal ganglia, many cortical projections bypass it and proceed directly to the subthalamic nucleus, establishing this subdivision as a second input region [222].

The cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, and thalamus form parallel circuits involving direct, indirect, and hyperdirect pathways [214]. Broadly, these circuits may be categorized into a limbic circuit (encompassing the prefrontal and limbic cortices, ventral striatum, thalamus, and basolateral complex of the amygdala), a cognitive circuit (prefrontal and limbic cortices, dorsomedial striatum, thalamus, and basolateral complex), and a sensorimotor circuit (sensorimotor cortices, dorsolateral striatum, thalamus, and central nucleus) [215, 223]. In each circuit, the cortical neurons project to a smaller population of spiny neurons, which then connect to an even smaller number of downstream neurons, creating a convergent architecture [224]. The direct and indirect spiny neuron projections within these circuits form direct and indirect pathways with opposing effects on thalamic activity. Specifically, the direct pathway inhibits the basal ganglia output nuclei, thereby disinhibiting the thalamus, whereas the indirect pathway disinhibits these nuclei, suppressing thalamic activity [217, 223]. Additionally, “bridging collaterals” in the pallidum link the direct and indirect pathways [225]. Beyond these pathways, cortical projections to the subthalamic nucleus form a hyperdirect pathway [222], which transmits signals faster than the direct or indirect pathways, enabling an immediate, diffuse inhibition of basal ganglia and thalamic activity [226].

The basal ganglia is crucial for learning and executing sequences of information, particularly the action sequences that may be considered to underpin complex behaviours [227, 228, 229]. Initially, many actions are learned and executed in a goal-directed, “purposeful” way, reinforced by reward-based outcomes, typically involving dopamine release [26]. However, with sustained reinforcement, these actions often shift to procedural, “habitual” forms, which are stimulus-driven and less sensitive to rewards or punishments. This change aligns with a gradual shift in processing from the limbic and cognitive circuits to the sensorimotor circuit [215, 230]. Beyond supporting purposeful and habitual action sequences, mounting evidence suggests the basal ganglia also influences various perceptual, cognitive, and emotional experiences [26, 231, 232, 233, 234]. In a predictive processing framework, it is tempting to speculate that the basal ganglia may play a broader role in learning and executing the sequences of predictions underlying not only actions but predictions generally, though evidence for this is preliminary [235].

The basal ganglia is central to learning purposeful and habitual actions [26, 236], which likely entails a unique striatal encoding process, called “chunking”, that composes cohesive action repertoires [227, 229]. Early learning involves purposeful actions, which are primarily mediated through the cognitive circuit, especially the dorsomedial striatum. The dorsomedial striatum’s key role in purposeful learning has been demonstrated in animals, where lesions reduce sensitivity to devaluation treatments, rendering actions habitual [237]. The basolateral complex may contribute to this learning by appraising and encoding outcome incentive values [238]. However, with repeated reinforcement, actions become stimulus-driven, with processing shifting to the sensorimotor circuit, particularly the dorsolateral striatum. Accordingly, lesions in the dorsolateral striatum restore sensitivity to outcome devaluation, highlighting its role in habit formation [239]. This gradual acquisition of habitual actions may involve chunking, which integrates and converts multiple action sequences into cohesive repertoires [227, 229]. Chunking provides a way for complex actions to be stored as singular entities with clear start and end points, which can be executed in an orderly, timed manner that requires minimal conscious oversight. This is especially adaptive in highly unpredictable environments [240]. Importantly, chunking is considered a core mechanism underlying all action learning stages, which becomes more pronounced as actions turn habitual [241]. Beyond action, there is evidence that chunking may also apply to cognitive processes [235].

Theoretically, basal ganglia processing involving the direct, indirect, and hyperdirect pathways enables the selective execution of cohesive action repertoires [228, 232, 242]. Animal studies show that the basal ganglia activates late during action expression, which supports an executory (rather than generative) role [243, 244]. This process presumably begins as purposeful and habitual cortical action signals, including proprioceptive predictions, converge on the dorsomedial and dorsolateral striatum, respectively [26, 215]. The convergent signals suggest that striatal spiny neurons serve as “coincident detectors”, selectively activating relevant spiny neuron ensembles [213]. The activated neurons process their information streams, in parallel, through other basal ganglia subdivisions, which is thought to involve a co-mobilization of the direct and indirect pathways [241]. This co-mobilization is primarily regulated by dopamine [217], with noradrenaline, serotonin, and acetylcholine also playing distinct regulatory roles [245]. Selective activation of the direct pathway disinhibits specific thalamic regions, facilitating the execution of specific action repertoires, while indirect pathway activation inhibits other thalamic regions, suppressing irrelevant or impulsive actions. Importantly, although largely segregated, these pathways are interconnected through striatal interneurons and pallidal bridging collaterals, potentially allowing the management of multiple variables [246]. Finally, the hyperdirect pathway may serve as a global reset, which can immediately halt ongoing actions to enable repertoire switching [247, 248, 249].

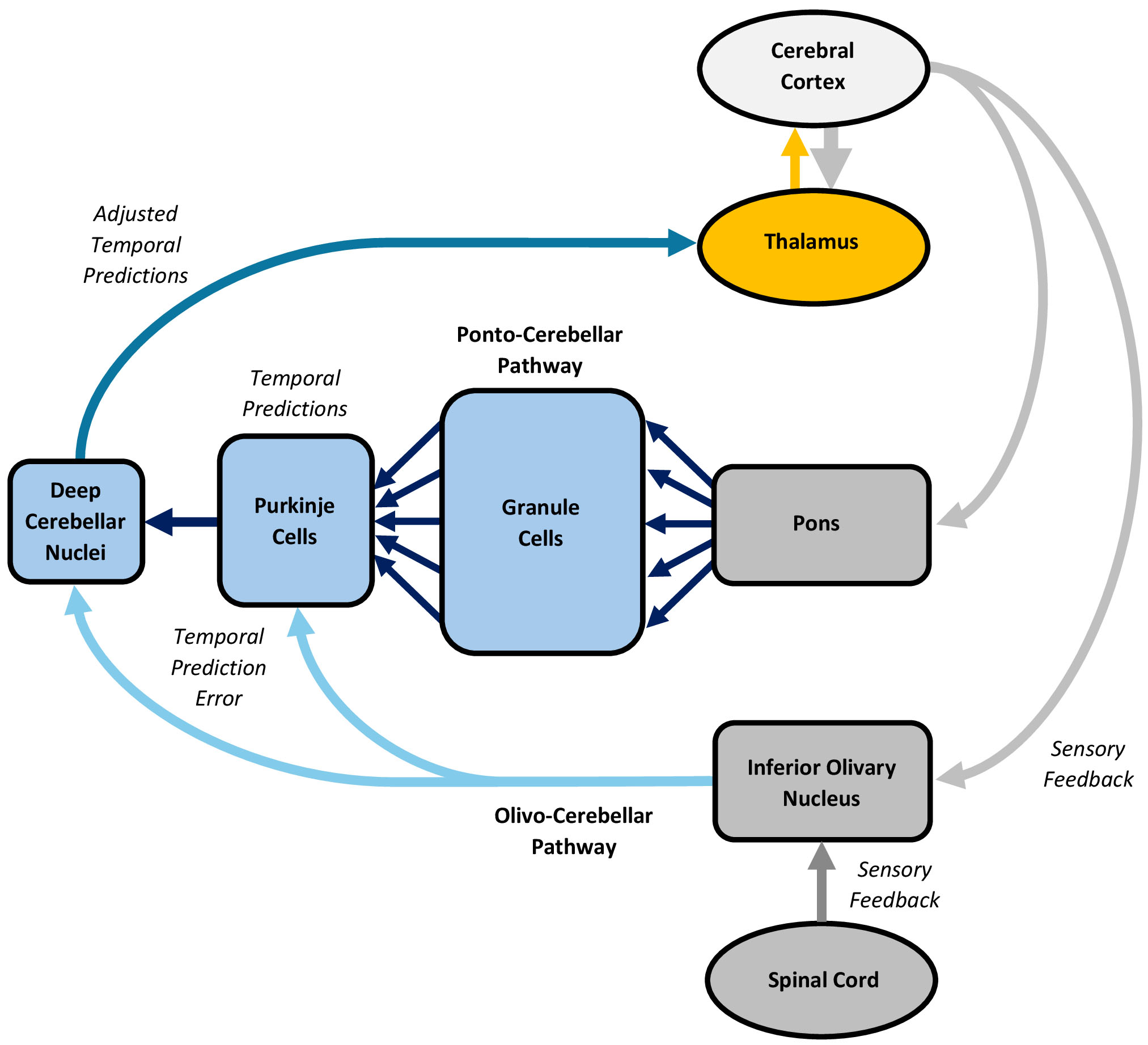

By engaging in its own unique form of predictive processing, the cerebellum likely sculpts cortical predictive processing by generating and adjusting temporal predictions, enabling the coordinated expression of actions and supporting perceptual, cognitive, and emotional experiences. Cerebellar processing depends on cortico-brainstem-cerebellar-thalamic circuits, involving “ponto-cerebellar” and “olivo-cerebellar” pathways (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Processing in the cerebellum, with an emphasis on the ponto-cerebellar and olivo-cerebellar pathways. The cerebral cortex, brainstem, cerebellum, and thalamus form circuits involving ponto-cerebellar and olivo-cerebellar pathways. Many actions and experiences are discontinuous, discrete, or non-rhythmic, requiring a representation of the temporal intervals that link them together. The cerebellum likely performs this role by engaging in a temporally-specific form of predictive processing that entails generating and adjusting temporal predictions through conjunctive processing in the ponto-cerebellar and olivo-cerebellar pathways, resulting in coordinated actions and experiences. Descending cortical signals, including predictions, are processed through the ponto-cerebellar pathway, where they are transformed into an alternative representation to generate temporal predictions. Simultaneously, sensory feedback from the sensorimotor cortices, vestibular system, midbrain nuclei, and spinal cord is processed through the olivo-cerebellar pathway, which elicits a teaching signal that conveys temporal prediction error, driving immediate and long-term adjustments in the temporal predictions. The figure was created using Microsoft Word 365.

The cerebellum comprises a large, intricately folded cerebellar cortex and a small white matter core [250, 251]. The cerebellar cortex crudely mirrors the topography of the cerebral cortex and features a unique geometric arrangement, primarily characterized by excitatory granule cells and inhibitory Purkinje cells. Granule cells, which outnumber all other neurons in the brain and body combined [252], each extend an unmyelinated, slow-conducting parallel fiber laterally, perpendicular to the cerebellum’s unfolded long axis [250]. These fibers synapse with the “dendritic trees” of Purkinje cells, which elicit both simple and complex spikes. Simple spikes arise intrinsically at regular intervals, creating inherent pacemaker activity [253]. However, up to 200,000 parallel fiber inputs synapse with each Purkinje cell [254], which can modulate or override this activity [255]. By contrast, complex spikes are typically provoked by a single, extraordinarily potent climbing fiber from the inferior olivary nucleus, which wraps around the dendritic trees of a handful of Purkinje cells [256]. This climbing fiber forms roughly 1000 synaptic contacts with each Purkinje cell, enabling a strong influence on pacemaker activity and synaptic plasticity among the parallel fibers, Purkinje cells, and local interneurons [255]. Collectively, the Purkinje cells project to the cerebellar white matter core, which houses four nuclei that also show pacemaker activity. Together, the Purkinje cells and nuclei comprise the output of the cerebellum.

The cerebral cortex, brainstem, cerebellum, and thalamus form parallel circuits involving ponto-cerebellar and olivo-cerebellar pathways [257]. The ponto-cerebellar pathway integrates topographic inputs from the cerebral cortex via limbic, cognitive, and sensorimotor circuits [258], as well as from cortical default mode, executive control, and salience networks [259]. This pathway primarily features a feedforward architecture, though Purkinje cell simple spike discharges may provide feedback [260, 261]. Importantly, the ponto-cerebellar pathway shows initial divergence, with each pontine mossy fiber connecting to about 500 granule cells [254], followed by massive convergence as the numerous granule cell parallel fibers target a much smaller number of Purkinje cells [257]. Conversely, the olivo-cerebellar pathway receives inputs from the sensorimotor cortices, vestibular system, midbrain nuclei, and spinal cord [262]. This pathway is topographically organized into “modules”, each defined by a single climbing fiber projecting from a specific inferior olivary nucleus region to a targeted zone of Purkinje cells, as well as their connections to a specific cerebellar nuclei cluster [263]. While feedback inhibition from climbing fibers dominates each module, the olivo-cerebellar pathway exhibits many other feedforward and feedback loops across the cerebellar cortex [255].

Compelling evidence demonstrates the cerebellum’s critical role in timing, which enables the coordinated expression of various actions and a broad array of perceptual, cognitive, and emotional experiences [27, 264, 265, 266, 267]. Many actions and experiences are characterized by “emergent timing”, whereby their temporal expression arises implicitly from processing in the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, and thalamus, possibly through oscillatory entrainment [268]. This emergent timing supports the efficient execution of continuous, cyclical, or rhythmic actions and experiences, such as sustained circle drawing [269], or beat-based auditory perceptual tasks [270]. In contrast, discontinuous, discrete, or non-rhythmic actions and experiences, such as intermittent circle drawing [269], or auditory duration discrimination [271], further require an explicit representation of the temporal intervals linking the individual (or chunked) actions and experiences. This non-emergent “event timing” is thought to rely on a distinct neural substrate, the cerebellum [272].

The cerebellum’s regular geometry and modular organization suggest that event timing may stem from a universal cerebellar processing operation grounded in predictive processing [27, 264, 273]. It has long been proposed that the cerebellum employs a feedforward model to generate action-related predictions that are updated by sensory feedback [274, 275], with the cerebellar nuclei activating prior to action initiation [276, 277]. Beyond action, the cerebellum also contributes to perceptual, cognitive, and emotional experiences, with preliminary evidence indicating granule cells can generate non-motor predictions [27, 278]. These findings support a temporally-specific form of predictive processing that spans motor and non-motor domains [264, 279]. Primate and human studies further imply that the cerebellum composes “temporal” predictions, which are vital for timing many actions and perceptual experiences [280, 281, 282, 283]. Additional evidence from animals shows that climbing fibers encode temporal prediction error, which may enable the temporal predictions to be continuously updated [284].

Theoretically, cerebellar predictive processing involves a conjunctive operation between the ponto-cerebellar and olivo-cerebellar pathways, with the former generating feedforward predictions and the latter adjusting them by utilizing prediction error feedback. This process tentatively begins as limbic, cognitive, and sensorimotor cortical signals, including predictions, travel a “descending” route to the ponto-cerebellar pathway [257], where the pontine mossy fibers diverge onto the granule cells, breaking the signals into multiple components [254]. Granule cells may transform these component signals into an alternative representation, which differs from mossy fiber activity [285]. The massive convergence of the parallel fibers upon the Purkinje cells allows these components to be weighted and integrated into their pacemaker signals, potentially through a “tidal wave” mechanism that converts sequential granule cell activation into synchronized Purkinje cell excitation [286]. The ensuing outputs of the Purkinje cells and cerebellar nuclei may reflect temporal predictions [280]. Simultaneously, sensory feedback pertaining to ongoing actions and experiences is relayed by the sensorimotor cortices, vestibular system, midbrain nuclei, and an “ascending” spinal cord route to the olivo-cerebellar pathway [257]. The climbing fibers in this pathway provoke complex spikes in Purkinje cells, which can adjust rate and temporal coding [255]. Collectively, these inputs likely serve as a “teaching signal” that conveys temporal prediction error, indicating how the temporal predictions associated with an action or experience must be adjusted to align with expected outcomes. Beyond this immediate, ongoing adjustment, this signal also induces long-term potentiation and depression between parallel fibers and Purkinje cells [287], promoting learning. By this account, the ponto-cerebellar pathway generates temporal predictions, which are adjusted by the olivo-cerebellar pathway as they are relayed to the cortex and other functional units for event timing and the coordinated expression of actions and experiences.

Consistent with an ancient history of philosophical thought, contemporary evidence suggests that the brain actively generates a stream of subconscious, sensory-updated statistical inferences about the world, which drive its conscious reality. Although the cerebral cortex generates these subconscious predictions, the thalamus, hippocampal complex, amygdala, basal ganglia, and cerebellum provide critical, yet indirect, supportive and integrative roles in translating the predictions into conscious, cohesive, and coordinated experiences and behaviours. Drawing on over 50 years of neuroscience research, including experimental evidence and associated theories, this review offers a framework for understanding the brain as an integrated system of semi-independent cortical and subcortical functional units, which work together, in harmony, to enable predictive processing. However, even when supported by considerable evidence, no framework can fully encompass the range of theories explaining how the brain processes reality. Given this intrinsic limitation, the proposed model should be seen as “one” way to understand how the brain works, rather than “the” way, which remains open to updates as new evidence arises.

MCLP conceived, wrote, edited, and approved the final manuscript. MCLP has participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The author acknowledges his colleagues, Dr James Leyden, Dr Thomas Oxley, and Dr Campbell Le Heron, for their insights during the genesis of this article.

This research received no external funding.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.