1 The Second School of Clinical Medicine, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, 310053 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 Wenzhou Institute, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 325001 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

3 Department of Engineering Mechanics, Institute of Biomechanics and Applications, Zhejiang University, 310007 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

4 The First Clinical Medical College, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, 310053 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

5 Department of Psychiatry, Wenzhou Seventh People’s Hospital, 325006 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

6 Department of Acupuncture and Physiotherapy, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, 325000 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

7 Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Zhejiang Hospital, 310013 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

8 Department of Acupuncture, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, 310005 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Abstract

Pharmacological treatment for adolescent depression is limited in safety and efficacy. Acupuncture treatment for depression has been endorsed by the World Health Organization. This study aimed to analyze the efficacy and mechanisms of acupuncture in treating adolescent depression.

An 4-week clinical trial was conducted from February 1, 2022 to June 30, 2024 at three hospitals. Patients aged 12 to 18 years were divided into three treatment groups: Manual acupuncture (MA), antidepressants (ADM), or acupuncture combined with antidepressants (MA+ADM). The 24-item Hamilton Depression scale (HAMD-24) scores, serum neurotransmitters levels, and resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (RS-fMRI) data were assessed at baseline (week 0) and after treatment (week 4).

After a 4-week intervention, both the MA and MA+ADM groups showed significant improvement in HAMD-24 scores. The MA+ADM group experienced more improvement, particularly in addressing somatization and sleep disorders. The study revealed that acupuncture increased serum levels of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), kynurenic acid, dopamine noradrenaline, adrenaline, L-histidine, and picolinic acid in adolescents with depression. Acupuncture was also found to regulate the excitability of depression-related brain regions (frontal lobe, caudate nucleus, anterior cingulate, and paracingulate gyri) and the functional connectivity of depression-related circuits (limbic-cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic circuit and hate circuit). Furthermore, significant negative correlations were observed between week 0 and week 4 HAMD-24 scores and up-regulated serum levels of 5-HT and dopamine. Scores were positively associated with increased amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations and regional homogeneity values.

Acupuncture improves adolescents’ depressive mood and sleep quality and alleviates somatic symptoms by modulating neurotransmitters levels and brain activity.

No: ChiCTR2200056171. https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=151197.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- adolescent

- depression

- acupuncture

- neurotransmitter agents

- magnetic resonance imaging

Adolescent depression has become the second leading cause of death among teenagers [1], with a prevalence of approximately 16% [2]. About 29% of these individuals exhibit suicidal ideation and 11% have attempted suicide [3]. The disorder imposes a tremendous socioeconomic and clinical burden, as patients often experience cognitive decline, reduced learning efficiency, substance abuse and suicide [4, 5]. Current studies propose that the depression results from multiple factors, specifically: (1) imbalance of monoamine neurotransmitters; (2) the brain structure and function reorganization hypothesis; and (3) dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [6]. However, the pathogenesis of adolescent depression and the biomarkers for predicting recurrence and evaluating efficacy are unclear. Moreover, the increase in drug variety forms an ever increasing “treatment-prevalence paradox” [7]. Therefore, finding safe and effective therapies is a compelling issue. Current guidelines provide evidence for the use of acupuncture in combination with medication for the treatment of adult depression, while adolescent depression primarily relies on psychotherapy and/or fluoxetine as the main treatment methods [8]. However, the efficacy and adherence of both therapies are limited, and concerns about medication tolerance and suicide risk persist [9, 10].

The 2024 guidelines from the American Medical Association clearly recommend incorporating non-pharmacological therapies into depression management [11]. Acupuncture has been acknowledged by the World Health Organization since 2002 as an effective non-drug therapy for depression. Accumulating evidence suggests that acupuncture is beneficial for various types of depression [12, 13]. Furthermore, acupuncture has the potential to both enhance patient response to antidepressants and reduce their side effects [14, 15, 16]. However, research on acupuncture for adolescent depression remains relatively scarce. One pilot study found that three weeks of auricular acupuncture reduced repetitive self-injurious behavior in eight adolescents with depression, although it did not improve their depressive mood [17]. Other studies are limited to case reports and protocol explorations, employing interventions such as intradermal acupuncture and transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation, and lack clinical data and mechanistic research on the efficacy of traditional manual acupuncture [18, 19, 20, 21]. A recent study shows that acupuncture alters the emotional responses of youth with self-reported depressive symptoms, suggesting the potential of acupuncture in adolescent depression [22]. Therefore, there is a need to conduct multi-center clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture for adolescent depression and to explore its mechanisms of action, which would provide valuable contributions to this field.

To address these issues, this study has two main objectives: (1) to evaluate the clinical efficacy of manual acupuncture (MA), antidepressant medication (ADM), and manual acupuncture combined with antidepressant medication (MA+ADM) on adolescent depression using the 24-item Hamilton Depression scale (HAMD-24) scores before and after treatment; (2) to explore the mechanisms of acupuncture treatment through a multidimensional analysis approach. Specifically, we compared the levels of serum neurotransmitters (such as tryptophan, tyrosine, and histidine) between the MA group and healthy control group (HCs). This comparison aimed to identify metabolic pathways associated with depression. Subsequently, we assessed the changes in serum neurotransmitters levels in the MA group before and after treatment to determine whether acupuncture could normalize these pathways. Then, we evaluated the changes in neuronal activity and functional connectivity in the brain using resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (RS-fMRI) data from the MA group before and after treatment. Additionally, we conducted Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis using large public databases to investigate the potential causal relationship between fMRI and depression risk.

This clinical study was conducted at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University and Wenzhou Seventh People’s Hospital from February 1, 2022 to June 30, 2024. The study patients included patients with depression who fulfilled the following criteria: (1) Age between 12 to 18 years; (2) Meeting the criteria of International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD-10); (3) Score of HAMD-24 greater than 20 points; (4) Agreement on informed consent signing; (5) Received a stable dose of antidepressant medication for at least four weeks prior to the start of the study in the groups of ADM and MA+ADM. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Secondary depression caused by drugs or organic psychosis; (2) Pregnant or lactating patients; (3) Treatment with antibiotics, steroids, or immunosuppressive agents two weeks before the assessment; (4) Severe suicidal or self-abusive tendencies; (5) Serious disease (such as heart, lung, liver, kidney dysfunction and infectious diseases).

A total of 150 adolescents diagnosed with depression and 50 age- and sex-matched HCs were recruited from local schools and communities via advertisements. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (2021-KL-075-01), the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (KY2021-123) and Wenzhou Seventh People’s Hospital (2022-Y26). All patients and their legal guardians provided written informed consent. The study registration code number (ChiCTR2200056171) was recorded with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (study registration date February 1, 2022).

All patients were grouped according to their willingness. Patients in the MA group received a 30-minute treatment three times per week for four weeks. Treatment was performed by licensed acupuncturists with more than five years’ experience. The acupuncture prescription was semi-standardized. The obligatory points were Baihui (DU20), Yintang (EX-HN3), Zhongwan (RN12), Qihai (RN6), Tianshu (ST25 bilateral), Neiguan (PC6 bilateral), Zusanli (ST36 bilateral) and Taichong (LR3 bilateral). In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theory, DU20, EX-HN3 and PC6 are commonly used to calm the spirit (Shen) and regulate mental disorders. RN12, RN6, ST25 and ST36 are key acupoints to regulate the Middle and Lower Jiao, helping to restore Qi balance and support digestion, which is considered essential for emotional stability. LR3 is a major Liver meridian point, often used to soothe Liver Qi stagnation, a core pattern of depression. Together, these points form a classical prescription to harmonize Heart, Liver, and Spleen, calm the Shen, and promote Qi circulation-key therapeutic strategies in managing depression from a TCM perspective. Adjunct acupoints were individualized by two senior TCM physicians-each with over five years of clinical experience-based on syndrome differentiation in accordance with TCM theory. Key TCM syndrome differentiation criteria are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Qimen (LR14 bilateral) was used for the syndrome of liver qi stagnation, Xingjian (LR2 bilateral) for the syndrome of stagnated qi transforming into fire, Fenglong (ST40 bilateral) for the syndrome of qi stagnation causing phlegm retention, Shaohai (HT3 bilateral) and Xinshu (BL15 bilateral) for the syndrome of lack of heart spirit, Xinshu (BL15 bilateral) and pishu (BL20 bilateral) are used for the syndrome of heart-spleen deficiency. Shenshu (BL23 bilateral) and Taixi (KI3 bilateral) for the syndrome of yin-deficiency and fire-hyperactivity. Disposable sterile acupuncture needles (0.25

In this study, antidepressant therapy was restricted to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) only (fluoxetine, escitalopram, and sertraline), with all prescriptions and dosing overseen by board-certified psychiatrists. In principle, no medication changes or dose adjustments were permitted during the trial period. Prior to initiation, research assistants provided thorough education on the importance of adherence; during the study, regular follow-ups and assessments were conducted to monitor each participant’s medication use, with reminders and interventions promptly delivered to those exhibiting poor adherence.

HAMD-24 scores were assessed by board-certified psychiatrists with over five years of clinical experience in the diagnosis and treatment of adolescent depression. Both clinicians held national licensure in psychiatry and were responsible for evaluating the severity of depression at baseline (week 0, W0) and after treatment (week 4, W4). HCs were assessed according to HAMD-24 only at W0 to ensure they were not in depressive mood. Seven factors, were assessed, including: anxiety/somatization, cognitive impairment, sleep disturbance, retardation, weight, diurnal variation and feelings of despair. Higher scores indicate increased depression.

Blood samples were collected from 28 patients with depression at baseline and after treatment, while 28 HCs were randomly selected for blood samples collected at baseline. Serum samples were obtained after centrifugation (3000 rpm, 20 min) and immediately stored at –80 °C. Human ELISA Kits 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, CSB-E08363h, CUSABIO, Wuhan, Hubei, China), Dopamine (DA, CSB-E06888h, CUSABIO, Wuhan, Hubei, China), 4-Aminobutyric acid (GABA, EHJ-11108, HUIJIA BIOTECHNOLOGY, Xiamen, Fujian, China) were used to measure levels of the serum neurotransmitters, including 5-HT (ng/mL), DA (ng/mL) and GABA (µmol/g).

Eight patient serum samples were collected before and after treatment and eight HC serum samples were sent for ultra high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) and mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. All 23 different neurotransmitters were analyzed. The information of 23 neurotransmitters is shown in Supplementary Table 3. All serum samples were analyzed with the UHPLC-MS/MS system (ExionLC™ AD UHPLC-QTRAP® 6500+, AB SCIEX Corp., Boston, MA, USA). Processing parameters are given in the Supplementary Material.

Data on depression (n = 53,313 cases and n = 394,756 controls) were obtained from the FinnGen Biobank (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5775047). RS-fMRI data were obtained from Zhao et al. [23] in the UK Biobank (UKB) sample, which includes 191 phenotypes (75 amplitude traits that reflect regional spontaneous neural activity, 111 pairwise functional connectivity (FC) and 5 global FC). To ensure the accuracy of MR analysis, single-nucleotide polymorphisms significantly associated with RS-fMRI phenotypes were used as instrumental variables (p

MRI images of 11 patients were scanned before and after treatment on a SIEMENS 1.5T MRI system (Avanto, SQ engine, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo sequence was used to obtain high-resolution 3D-T1WI anatomical images (parameters given in the Supplementary Material). Acquisition of both sequences required about eight minutes. During the MRI scan, patients were instructed to close their eyes, remain awake, stay relaxed, avoid thoughts and not move their head.

The RESTplus v1.24 (maintained at http://www.restfmri.net/forum/restplus) software package based on MATLAB R2017b (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) was used for data preprocessing. Amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (ALFF), regional homogeneity (ReHo) and FC analysis were performed (procedures given in the Supplementary Material).

The brain regions with statistical differences in ALFF and ReHo values before and after acupuncture treatment were as follows: for ALFF, the right middle frontal gyrus (MFG.R), right superior frontal gyrus (SFG.R), right granular dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC.R), right anterior cingulate and paracingulate gyri (ACG.R); for ReHo, the regions included MFG.R, SFG.R, dlPFC.R, ACG.R, the right caudate nucleus (CAU.R); and for MRI analysis, the regions were the temporal lobe, superior frontal gyrus (SFG), precuneus, angular and cingulate gyri. These regions were taken as regions of interest (ROI), and the peak value of ALFF and ReHo was at the position (33, 45, 33). In addition, for FC analysis, left superior frontal gyrus medial area 8 (SFG.L.7.1) (–5, 15, 54), left superior frontal gyrus medial area 6 (SFG.L.7.5) (–6, –5, 58), right superior frontal gyrus medial area 6 (SFG.R.7.5) (7, –4, 60) and left posterior parietal thalamus (THA.L.8.5) (–16, –24, 6) were also taken as ROIs [24]. Spherical regions with a six mm radius were taken as seed points to conduct the whole-brain FC analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were first evaluated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and for homogeneity of variance using Levene’s test. Variables meeting both criteria are presented as mean

Baseline clinical characteristics across all four groups (HCs, MA, ADM, MA+ADM) were compared. HAMD-24 total and factor scores at W0 and W4 were compared among the three patient groups (MA, ADM, MA+ADM): continuous measures satisfying ANOVA assumptions were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc correction; otherwise, the Kruskal-Wallis H test with Dunn’s post-hoc correction was used. Pairwise comparisons of categorical variables were Bonferroni-adjusted. Spearman’s rank correlation assessed relationships between HAMD-24 scores and serum neurotransmitters levels, ALFF values, and ReHo values. Differences and correlations will be considered statistically significant at a p-value

A total of 150 depressed adolescents and 50 matched HCs were recruited (Fig. 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of all individuals are summarized in Table 1. HAMD-24 scores and disease duration of patients were not significantly different among the three intervention groups. Statistically significant differences (p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Clinical study flowchart. HCs, healthy controls; MA, manual acupuncture; ADM, antidepressant medication; HAMD-24, 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; DA, dopamine; GABA, 4-aminobutyric acid; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging.

| Characteristics | HCs (n = 50) | MA (n = 50) | ADM (n = 50) | MA+ADM (n = 50) | p-valuea | |

| Age, M (P25, P75), y | 16.0 (14.75, 17.00) | 16.0 (15.00, 17.00) | 16.0 (14.00, 17.00) | 16.0 (15.00, 17.00) | 0.837 | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.423 | |||||

| Male | 21 (42.00) | 15 (30.00) | 15 (30.00) | 14 (28.00) | ||

| Female | 29 (58.00) | 35 (70.00) | 35 (70.00) | 36 (72.00) | ||

| Duration of depression, mean (SD), y | NA | 1.91 (1.23) | 2.08 (1.21) | 1.68 (0.84) | 0.194b | |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 20.72 (2.66) | 20.89 (3.45) | 20.57 (3.30) | 20.18 (3.07) | 0.707 | |

| Somatotype, n (%) | 0.895 | |||||

| Thin | 11 (22.00) | 13 (26.00) | 11 (22.00) | 15 (30.00) | ||

| Normal | 31 (62.00) | 28 (56.00) | 33 (66.00) | 27 (54.00) | ||

| Overweight/Fat | 8 (16.00) | 9 (18.00) | 6 (12.00) | 8 (16.00) | ||

| Educational attainment, n (%) | 0.849 | |||||

| Junior high school and below | 18 (36.00) | 16 (32.00) | 18 (36.00) | 13 (26.00) | ||

| Senior high school | 23 (46.00) | 24 (48.00) | 26 (52.00) | 28 (56.00) | ||

| College and above | 9 (18.00) | 10 (20.00) | 6 (12.00) | 9 (18.00) | ||

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.910 | |||||

| Not smoking | 45 (90.00) | 43 (86.00) | 44 (88.00) | 45 (90.00) | ||

| Smoke regularly | 5 (10.00) | 7 (14.00) | 6 (12.00) | 5 (10.00) | ||

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 0.253 | |||||

| No alcohol | 42 (84.00) | 42 (84.00) | 47 (94.00) | 46 (92.00) | ||

| Drink regularly | 8 (16.00) | 8 (16.00) | 3 (6.00) | 4 (8.00) | ||

| Stressful events, n (%) | ||||||

| Family problems | 12 (24.00) | 32 (64.00)* | 39 (78.00)* | 33 (66.00)* | ||

| Study/work problems | 36 (72.00) | 42 (84.00) | 39 (78.00) | 43 (86.00) | 0.290 | |

| Interpersonal relationship/Emotional problems | 17 (34.00) | 33 (66.00)* | 29 (58.00) | 32 (64.00)* | 0.004 | |

| Other events | 16 (32.00) | 31 (62.00)* | 30 (60.00)* | 29 (58.00) | 0.008 | |

| HAMD-24 scoresc, mean (SD) | 4.22 (1.89) | 27.70 (10.63) | 26.82 (5.85) | 28.14 (9.33) | 0.749b | |

SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index. a Calculated using a one-way analysis of variance (p-value based on the Tukey adjustment in pairwise comparison based on data distribution) or Chi-square test (p-value based on the Bonferroni adjustment in pairwise comparison). b HCs group were not analyzed with other three groups. c Score range is from 0 to 76, with higher scores indicating more serious depression. *p

Table 2 presents the pre- and post-treatment changes in HAMD-24 total and factor scores for all patients. There was significant reduction (p

| Outcome Measure | MA (n = 50) | ADM (n = 50) | MA+ADM (n = 50) | F/H | p-valuea | ||

| HAMD-24 scoresc, mean (SD)/median (quartile 1-quartile 3) | |||||||

| Week 0 | 27.70 (10.63) | 26.82 (5.85) | 28.14 (9.33) | 0.289 | 0.749b | ||

| Week 4 | 17.00 (12.00, 25.00)*### | 16.76 (6.09)### | 13.60 (6.46)### | 8.741 | 0.013 | ||

| Seven factor scores of HAMD-24 | |||||||

| Factor 1: Anxiety/Somatisation | |||||||

| Week 0 | 7.00 (5.00, 8.00) | 6.66 (1.85) | 6.70 (3.02) | 0.113 | 0.945 | ||

| Week 4 | 4.50 (3.00, 6.00)***### | 4.54 (1.57)***### | 2.00 (1.00, 4.00)### | 33.276 | |||

| Factor 2: Cognitive impairment | |||||||

| Week 0 | 6.00 (3.00, 8.00) | 4.90 (2.31) | 6.00 (2.99) | 3.928 | 0.140 | ||

| Week 4 | 3.00 (2.00, 6.00)### | 3.00 (2.00, 5.00)### | 3.00 (1.75, 5.00)### | 3.141 | 0.208 | ||

| Factor 3: Sleep disturbance | |||||||

| Week 0 | 3.22 (1.76) | 4.00 (2.00, 5.00) | 3.50 (2.00, 5.00) | 2.313 | 0.315 | ||

| Week 4 | 3.00 (2.00, 4.00)***### | 2.00 (1.00, 3.00)***### | 0.50 (0.00, 2.00)### | 56.559 | |||

| Factor 4: Retardation | |||||||

| Week 0 | 5.00 (3.75, 7.00) | 5.00 (4.00, 6.00) | 5.30 (2.11) | 1.357 | 0.507 | ||

| Week 4 | 3.00 (2.00, 4.00)### | 3.00 (2.00, 4.25)### | 3.00 (2.00, 4.00)### | 2.874 | 0.238 | ||

| Factor 5: Weight | |||||||

| Week 0 | 1.00 (0.00, 1.25) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.524 | 0.769 | ||

| Week 4 | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)### | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)### | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)### | 1.956 | 0.376 | ||

| Factor 6: Diurnal variation | |||||||

| Week 0 | 1.00 (0.00, 2.00) | 1.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00) | 5.622 | 0.060 | ||

| Week 4 | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00)### | 1.00 (0.00, 1.00)### | 1.00 (0.00, 1.00)### | 2.110 | 0.348 | ||

| Factor 7: Feelings of despair | |||||||

| Week 0 | 5.00 (3.00, 6.00) | 4.00 (3.75, 6.00) | 4.64 (2.27) | 0.109 | 0.947 | ||

| Week 4 | 3.00 (2.00, 4.00)### | 2.50 (2.00, 3.00)### | 3.00 (2.00, 4.00)### | 1.274 | 0.529 | ||

a Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to compare the three groups. b A one-way analysis of variance (p-value based on the Tukey adjustment in pairwise comparison based on data) was used to compare the three groups. c Score range is from 0 to 76, with higher scores indicating more serious depression. *p

Patients in the ADM and MA+ADM groups included in this study had been taking different types and doses of antidepressants for at least one month. Antidepressants are known to work by altering neurotransmitters levels and may have a greater effect on serum neurotransmitters levels [25]. Therefore, this study focused on the detection of serum neurotransmitters levels in the HC and MA groups to observe the effect of acupuncture treatment on serum neurotransmitters.

Table 3 shows serum levels of 5-HT, DA and GABA in HCs and adolescents with depression in the MA group before and after acupuncture treatment. Compared with patients in the pre-treatment group, 5-HT and DA serum levels were significantly increased in patients in the post-treatment group (p

| Group | Serum neurotransmitters levels | ||

| 5-HT (ng/mL) | DA (ng/mL) | GABA (µmol/g) | |

| HCs (n = 28) | 237.09 (46.01) | 58.50 (17.69) | 1.44 (0.26) |

| pre-treatment (n = 28) | 111.88 (35.53, 225.70)*** | 25.87 (12.42)*** | 1.46 (1.30, 1.75) |

| post-treatment (n = 28) | 177.71 (59.32, 289.56)###* | 47.81 (24.42)### | 1.30 (1.23, 1.49) |

All data were expressed as mean (

Based on literature [6], we focused on four neurotransmitters pathways closely associated with depression: the tryptophan-5-HT, tyrosine-DA/noradrenaline (NE), histidine-histamine (HisA), and glutamate-GABA pathways. Initial ELISA results revealed significant differences in 5-HT and DA levels both between and within groups, underscoring their potential role in adolescent depression. To further investigate whether acupuncture modulates a broader spectrum of neurotransmitter pathways, we subsequently conducted targeted UHPLC-MS/MS analysis of 23 neurotransmitters in serum samples collected at W0 and W4 from 8 HCs and 8 patients who received MA treatment. Eighteen kinds of neurotransmitters were identified, of which 10 showed significant difference among three groups (Fig. 2), including 5-HT, DA (found in section 3.3). When compared to HCs group, the pre-treatment group showed distinctly lower level in serum 5-HT, 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid (5-HIAA), kynurenic acid (KynA), NE, L-histidine (His) and acetylcholine chloride (Acetyl-CoA). After treatment, the serum 5-HT, KynA, DA, NE, adrenaline (E), His and picolinic acid (PA) levels increased compared to the pre-treatment group. The serum 5-HIAA and Acetyl-CoA levels of post-treatment were significantly lower, while serum DA and HisA levels of the post-treatment were higher, compared with those in HCs group. No difference was detected in GABA, L-tryptophan, DL-kynurenine (Kyn), L-tyrosine (Tyr), levodopa, L-glutamic acid (Glu), L-glutamine and xanthurenic acid.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Serum levels of neurotransmitters in healthy controls and patients with depression before and after acupuncture treatment. (a) Eleven kinds of neurotransmitters involved in tryptophan metabolism. (b) Five kinds of neurotransmitters involved in histidine and glutamate metabolism. (c) Seven kinds of neurotransmitters involved in tyrosine metabolism. The neurotransmitters within blue boxes were detected. #p

An MR analysis found that increased FC between the temporal lobe and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) reduced the risk of depression (Inverse-Variance Weighted Odds Ratio (IVW OR) = 0.88, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.80–0.96, p = 0.004). Additionally, it was found that enhanced neural connection activity in SFG and IFG was associated with a lower risk of depression (IVW OR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.68–0.92, p = 0.003). Further analysis revealed that higher FC of the temporal lobe, frontal lobe or supplementary motor area and frontal lobe was inversely related to depression risk (IVW OR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.72–0.92, p = 0.001). Conversely, it was discovered that increased FC between precuneus, angular gyrus or cingulate and temporal lobe elevated the risk of depression (IVW OR = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.03–1.32, p = 0.012). It is also noted that higher connectivity in the global measure of the default mode network (DMN) was associated with a heightened risk of depression (IVW OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.00–1.13, p = 0.044). Finally, findings indicated that increased activity in the calcarine, lingual or cuneus and paracentral or postcentral regions was linked to a decreased risk of depression (IVW OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.87–1.00, p = 0.040) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Forest plot of the causal association between RS-fMRI and depression. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphisms; OR, odds ratio; MR, Mendelian randomization; IVW, inverse variance weighted; CI, confidence interval; RS-fMRI, resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging.

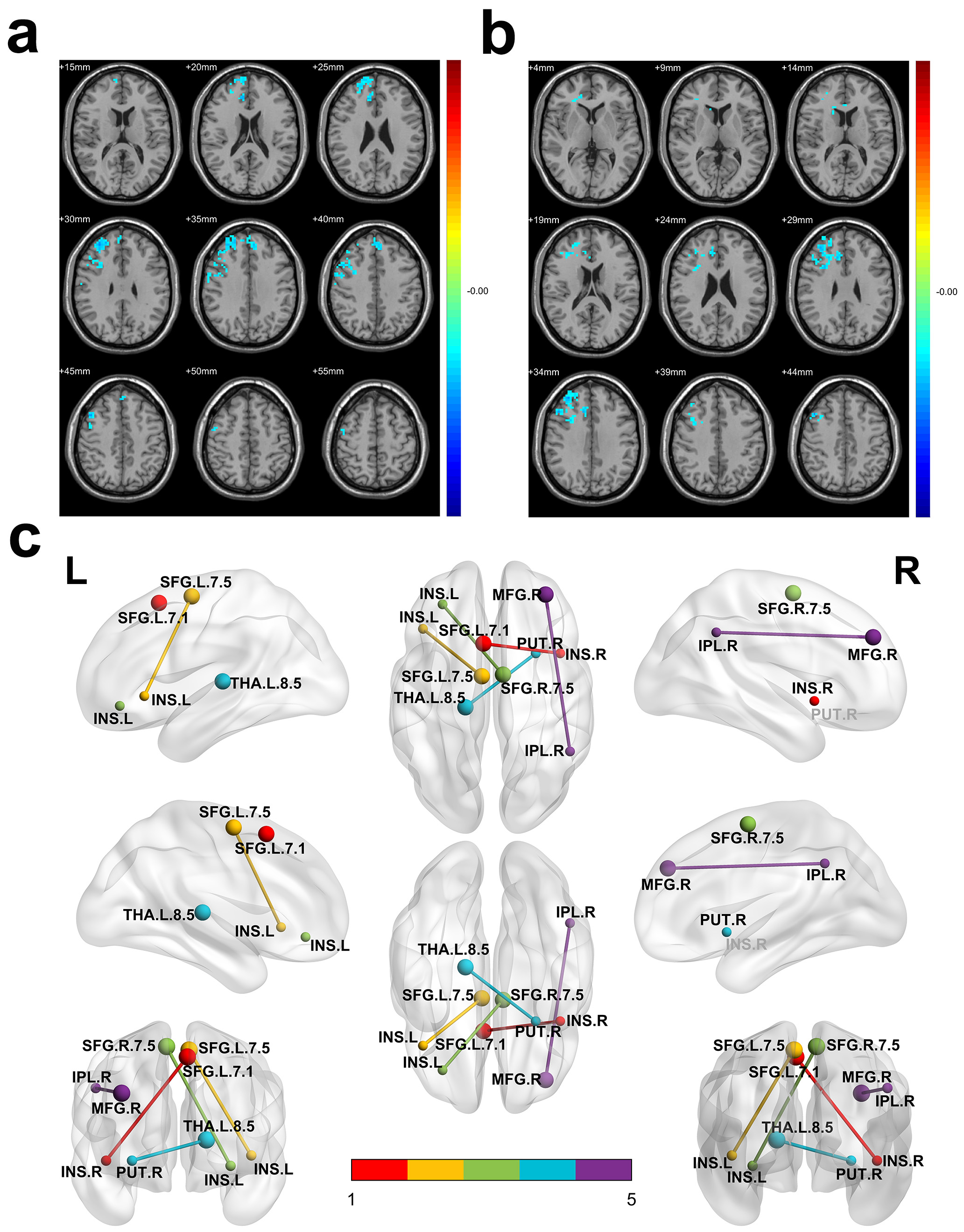

Compared to the pre-treatment group, patients after treatment showed significantly lower ALFF and mKccReHo values in MFG.R, SFG.R, dlPFC.R, and ACG.R (Fig. 4a,b, Table 4). Additionally, the mKccReHo value of the CAU.R in the post-treatment group was significantly reduced (Fig. 4b, Table 4). These results suggest that the excitability of the above brain regions would be reduced after acupuncture treatment.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Differences of ALFF, ReHo and FC in adolescents with depression before and after acupuncture treatment. (a) Compared with patients before acupuncture treatment, reduced ALFF values in the MFG.R, SFG.R, dlPFC.R and ACG.R were observed in patients after treatment. (b) Compared with patients before acupuncture treatment, reduced mKccReHo values in the MFG.R, SFG.R, dlPFC.R, ACG.R and CAU.R were observed in patients after treatment. (c) Compared with patients before acupuncture treatment, patients after treatment show two negative connections: between MFG.R and IPL.R (purple line), between THA.L.8.5 and PUT.R (blue line); and patients before treatment show three positive connections: between SFG.L.7.1 and INS.R (red line), between SFG.L.7.5 and INS.L (yellow line), as well as between SFG.R.7.5 and INS.L (green line). (a,b) Red and blue denote higher and lower ALFF or mKccReHo respectively and the color bars indicate the T value from two-tailed tests. ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; ReHo, regional homogeneity; mKccReHo, mean Kendall coefficient of concordance regional homogeneity; MFG.R, right Middle Frontal Gyrus; SFG.R, right Superior Frontal Gyrus; dlPFC.R, right dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex; ACG.R, right Anterior cingulate and paracingulate gyri; CAU.R, right Caudate nucleus; FC, functional connectivity; IPL.R, right Inferior Parietal Lobule; THA.L, left Thalamus; PUT.R, right putamen; SFG.L, left Superior Frontal Gyrus; INS.R, right Insula; INS.L, left Insula.

| Coordinate regions | Cluster size | Peak T value | MNI coordinate (mm) | |||

| X | Y | Z | ||||

| ALFF | ||||||

| MFG.R, SFG.R, dlPFC.R, ACG.R | 456 | –3.8082 | 33 | 45 | 33 | |

| ReHo | ||||||

| MFG.R, SFG.R, dlPFC.R, ACG.R, CAU.R | 358 | –3.6502 | 33 | 45 | 33 | |

ALFF, the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; Gaussian random field (GRF) correction, voxel-level p

In agreement with the partial aforementioned MR estimates, the post-treatment patients exhibited increased FC between the temporal lobe and IFG, SFG and IFG, as well as between the temporal lobe and the frontal lobe, when compared to their pre-treatment state (Table 5).

| ROI | Coordinate regions | Cluster size | Peak T value | MNI coordinate (mm) | ||

| X | Y | Z | ||||

| STG.L.6.4 | IFG, Frontal Gyrus (MR related FC) | 512 | 4.2077 | –42 | 21 | 12 |

| STG.L.6.6 | IFG, Frontal Gyrus (MR related FC) | 189 | 3.7442 | –33 | 36 | –21 |

| SFG.R.7.7 | IFG (MR related FC) | 235 | 3.5071 | –18 | 30 | –27 |

| MFG.R | IPL.R, PCUN.R, right temporal lobe (DMN) | 446 | –4.1908 | 48 | –51 | 36 |

| (MR related FC) | ||||||

| SFG.L.7.1 | IFG (MR related FC) | 869 | 3.8338 | 42 | 9 | –6 |

| INS.R, PUT.R (hate circuit) | ||||||

| SFG.L.7.5 | IFG (MR related FC) | 255 | 3.9593 | –42 | 24 | –3 |

| INS.L, PUT.L (hate circuit) | ||||||

| SFG.R.7.5 | IFG (MR related FC) | 310 | 4.604 | –30 | 39 | –9 |

| INS.L, PUT.L (hate circuit) | ||||||

| THA.L.8.5 | PUT.R, right limbic lobe, right frontal lobe, SFG.R (orbital part), CAU.R, PAL.R (LCSPT circuit) | 177 | –3.993 | 27 | 9 | –6 |

STG.L, left superior temporal gyrus; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; PCUN.R, right precuneus; DMN, default mode network; PAL.R, right pallidum; LCSPT, limbic-cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic.

For ROI-whole brain connectivity (Fig. 4c, Table 5), post-treatment patients showed decreased FC when compared to pre-treatment in terms of MFG.R connectivity with clusters including the right inferior parietal lobule (IPL.R), right precuneus (PCUN.R) and right temporal lobe. These regions showing significant changes after acupuncture treatment are mainly within the DMN, which was a causal risk factor for depression in this MR analysis.

Another area with decreased FC was located in the left posterior parietal thalamus (THA.L.8.5) area extending into the right putamen (PUT.R), right limbic lobe, right frontal lobe, right caudate (CAU.R) and right pallidum (PAL.R). These structures are predominantly components of the limbic-cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic (LCSPT) circuit. Post-treatment patients exhibited enhanced bilateral SFG connections with insula (INS) and putamen (PUT), which are primarily part of a hate circuit.

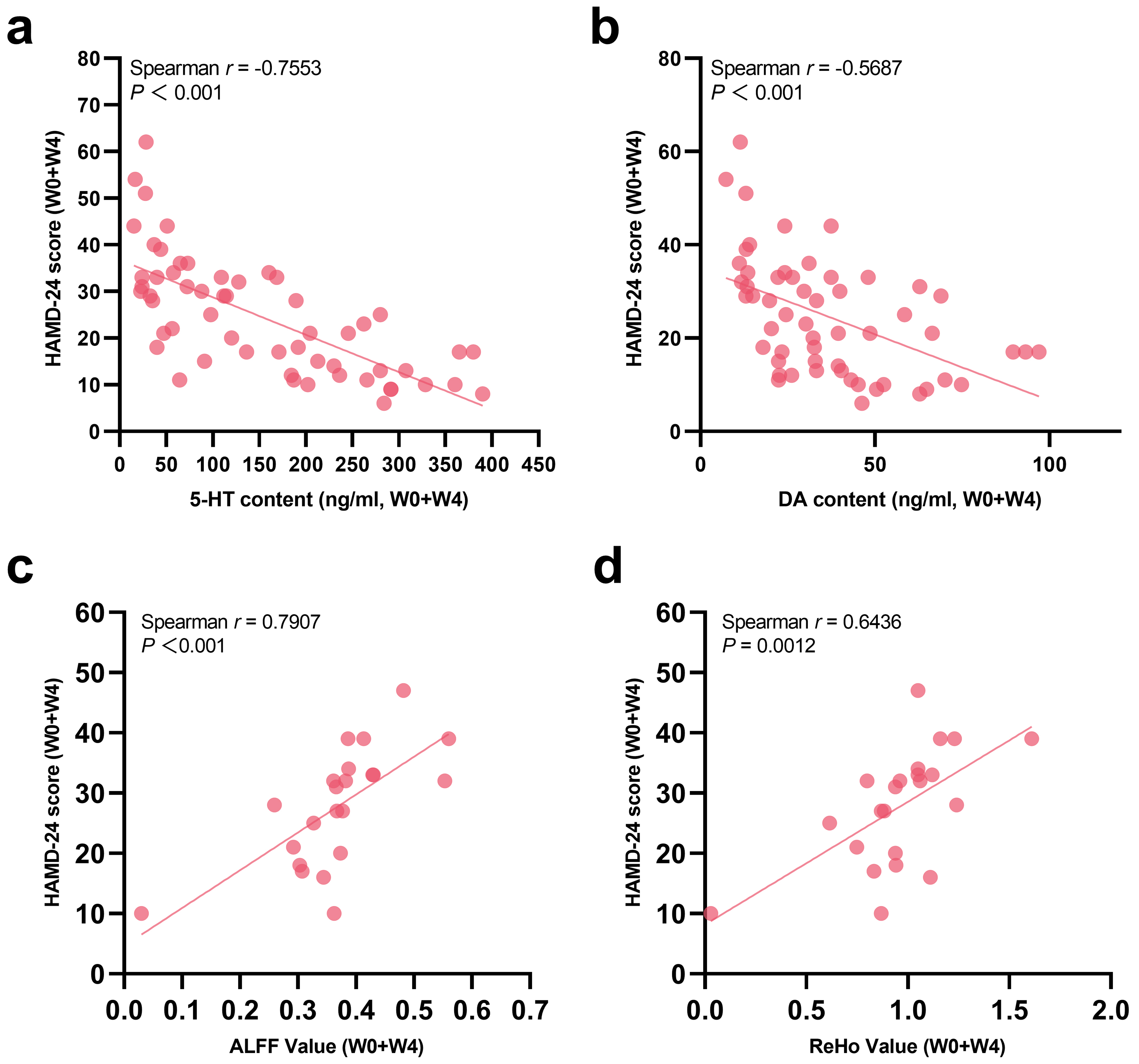

Spearman correlation analysis was used to further explore correlations between HAMD-24 scores and serum 5-HT levels, serum DA levels, ALFF values and ReHo values of patients with depression (Fig. 5). It was found that the HAMD-24 scores of patients at W0 and W4 showed significant negative correlations with up-regulated serum 5-HT and DA levels, while they had a positive correlation with the ALFF and ReHo values of SFG.R, dlPFC.R and ACG.R.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Correlations between HAMD-24 scores and (a) serum 5-HT levels, (b) Serum DA levels, (c) ALFF, and (d) ReHo in adolescents with depression.

This study shows that a four-week course of acupuncture significantly improves depressive symptoms in depressed adolescent patients. The efficacy likely arises from increased serum levels of 5-HT, DA, KynA, NE, E, His and PA, decreased functional connectivity in the DMN and LCSPT networks and strengthened connectivity in a hate circuit. Furthermore, HAMD-24 scores are closely correlated with 5-HT, DA, ALFF and ReHo. No serious adverse events were reported in our study.

Twelve acupuncture sessions over four weeks reduced HAMD-24 scores in adolescents with depression and the synergy with antidepressants is significant. Acupuncture also alleviates anxiety/somatization and sleep disorders in depressed adolescent patients, with more pronounced effects in the MA+ADM group, exceeding those of either MA or ADM alone. These findings are consistent with recent studies [12, 26]. Four weeks of acupuncture significantly alleviated depression and insomnia [27], while six weeks of acupuncture combined with SSRIs showed superior improvements in anxiety, somatization and sleep disturbances when compared to SSRIs alone [14, 28]. The synergistic effect of acupuncture has been preliminarily validated [14, 29, 30, 31]. Although this study did not include a predefined medication tapering assessment protocol, psychiatrists reported a faster medication tapering trend among some patients in the MA+ADM group who voluntarily continued acupuncture treatment post-trial. This observational phenomenon requires validation through prospective studies with standardized tapering protocols.

Depression is associated with dysregulation in the neurotransmitters systems, including the serotonin and dopamine pathways [32]. Results reported here suggest that acupuncture affected serum neurotransmitters regulation in adolescents with depression and involved the tyrosine (DA, NE and E), tryptophan (5-HT, 5-HIAA, KynA and PA) and histidine (His and HisA) pathways.

These findings are consistent with previous studies. Specifically, for the tyrosine metabolic pathway, the levels of DA, NE and E could be improved by acupuncture in depressed patients and animal models [33, 34]. These neurotransmitters are frequently found at reduced levels in the serum of patients diagnosed with depression. Moreover, PC6 stimulation has been demonstrated to reverse anhedonia and to markedly suppress c-fos expression within the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus [35].

For the tryptophan metabolic pathway, the levels of 5-HT, 5-HIAA, KynA and PA of patients before the treatment were lower than those in the HCs group. For instance, recent studies have found that the levels of PA in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid were lower in depressed patients [36, 37, 38, 39] and this state had persisted in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients who had attempted suicide for a duration exceeding more than two years [40]. The current study showed that the levels of those transmitters could be significantly increased by acupuncture treatment. Further research indicated that the combined stimulation of DU20, ST36, and CV12 upregulated the 5-HT system, promoted gastrointestinal motility, and repaired synaptic damage in the hippocampus [41]; moxibustion at ST25, CV6, and DU20 regulated the kynurenine metabolic pathway along the gut-brain axis, inhibited overactivation of microglia and neurons in the hippocampus, and improved depressive-like behaviors [42]. Additionally, electroacupuncture at ST36 and ST25 exerted antidepressant effects by modulating the gut microbiota and neurotransmitter systems [43]. Finally, electroacupuncture at LR3 modulated the cerebral kynurenine pathway, decreased proinflammatory cytokines and glutamate release [44].

For the histidine metabolic pathway, it was found that the level of His in patients before treatment was lower than that in HCs group and it increased after acupuncture treatment. Studies have shown that His deficiency can be used as a predictor of moderate depressive symptoms in older women [45]. In the current study, it was found that HisA levels tended to be elevated in the pre-treatment group but were significantly higher after acupuncture treatment when compared to a HCs group, which may be related to the involvement of HisA in the regulation of brain 5-HT, DA and NE systems, as well as the immune system [46].

The RS-fMRI technology measures brain neuron activity and synchronicity, aiding in evaluating acupuncture’s effects on depression. While many studies focus on adults, adolescent depression may involve different mechanisms due to incomplete neurodevelopment. Thus, analyzing RS-fMRI changes in adolescents before and after acupuncture is crucial. Higher ALFF values represent stronger neuronal activity and higher ReHo values represent greater synchronization of local neuronal activity. The frontal lobe is an important part of the cognitive control network and is involved in emotion regulation and cognitive execution. The ACG is a limbic structure involved in the processing of emotional and reward information. The CAU is involved in the brain’s reward system and is associated with the dopamine system and its dysfunction causes anhedonia. Depressed patients have elevated fALFF in the prefrontal lobe, ACG, SFG and MFG [47]. The current study found that acupuncture decreased the ALFF and ReHo values of the MFG.R, SFG.R, dlPFC.R and ACG.R and also decreased the ReHo value of CAU.R. These changes mainly occurred in the right cerebral hemisphere. A positive correlation between ALFF and ReHo values and HAMD-24 scores was also found, suggesting that acupuncture could balance neuronal activity and local consistency in the aforementioned brain regions of adolescents with depression, which is consistent with the results of acupuncture treatment for depression in adults [48, 49] and elderly people [50]. Notably, stimulation of LR3 might exert antidepressant effects by enhancing frontal-lobe function [51]. Antidepressants and acupuncture somehow have a consistent regulatory effect on the SFG and MFG. Additionally, acupuncture also regulates CAU dysfunction when compared to antidepressants. Such results support the existing results of the role of the frontal limbic system in the pathogenesis of adolescent depression and that acupuncture treatment reverses the abnormal activity of the frontal limbic system [52].

In the MR study reported here, elevated FC between the temporal lobe and the inferior frontal, superior frontal and inferior frontal gyri, as well as the temporal and frontal lobes, were identified as protective factors against depression. After acupuncture treatment, the FC within these specified brain regions was observed to have increased. This study found no significant effect of acupuncture on the regulation of FC between the precuneus or cingulate and temporal lobe, which has been found to be enhanced in depressed patients. No effect of acupuncture was found on the regulation of neural activities of the calcarine cortex, lingual gyrus, cuneus, postcentral gyrus and precentral gyrus. It is speculated that this discrepancy may be the result of participant variability.

The DMN is thought to be involved in emotional and cognitive function and previous studies have confirmed over-connectivity within the DMN in depressed patients [53, 54, 55, 56, 57], with similar findings in adolescent depression [58, 59]. The DMN may be a potential target for the treatment of depression, which can be normalized by transcranial magnetic stimulation [60]. MR suggested that increased connectivity of the DMN causes higher depression risk. In the current study, the FC between the MFG.R and IPL.R, PCUN.R and temporal lobes were found to be weakened by the acupuncture treatment in depressed patients, suggesting that acupuncture reduced the connections within the DMN. Other studies found that electro-acupuncture at the Baihui point suppressed DMN overactivation [61, 62].

The LCSPT circuit is considered to be an important circuit in the pathogenesis of depression [63]. Structural and functional changes in LCSPT circuits are likely to be highly reliable markers of depression diagnosis [64, 65]. The amygdala is located in the limbic system and is involved in a variety of emotional processes. When the pathological activity of the amygdala increases, abnormal activity of the LCSPT circuit might occur [66]. Additionally, it was found that by cutting off the projection of the amygdala to the LCSPT circuit, patients with treatment-resistant depression were less likely to relapse into depression [67, 68]. It can be seen that there is a close relationship between the amygdala and LCSPT circuits. This study showed that in the resting state of the brain of patients after acupuncture, the FC of the LCSPT circuit were weakened when compared with that found prior to treatment, including in the right limbic lobe, right frontal lobe, SFG.R (orbital part), PUT.R, PAL.R and THA.L, in addition to the amygdala. Both monoamine-targeted antidepressants and electroconvulsive therapy reverse structural abnormalities in LCSPT circuits [69, 70, 71]. Several studies have even suggested that regulating the LCSPT circuits may be the central mechanism of acupuncture treatment for depression [29, 72, 73]. It is worth mentioning that Glu is an excitatory neurotransmitter that exhibits elevated transmission in the LCSPT circuits of depressed patients [74], which is consistent with the trend found here in the mass spectrometry analysis.

When using bilateral SFG as the seed points for whole-brain FC analysis, this study found that the FC of a hate circuit was enhanced in adolescents with depression after acupuncture, mainly involving the functional regions SFG, INS and PUT. INS and PUT are involved in the perception of contempt and hate [75, 76]. It was first proposed in 2013 that the FC of hate circuits was weakened in patients with depression. If the hate circuit is damaged, patients would have less cognitive control over their emotions and have difficulty in controlling negative thoughts, such as self-loathing or hatred of external circumstances. Several subsequent studies have found similar results, including a decrease in FC inside the PUT [75, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81]. Given that adolescents with depression are prone to resentment, it is speculated here that changes in a hate circuit may play an important role in both the pathogenesis and treatment of adolescent depression and acupuncture may provide a better treatment option.

This study preliminarily reveals the potential mechanisms of acupuncture in treating depression in adolescents. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. There was no sham acupuncture control group, making it difficult to isolate non-specific effects. The effects of acupuncture may be influenced by psychosocial factors such as patient expectations, doctor-patient interactions, and procedural rituals. Future research should introduce standardized sham acupuncture devices and evaluator blinding, quantify patient expectations, and monitor neurotransmitter and brain function changes to analyze the specific mechanisms of acupuncture and reduce bias from placebo effects. Additionally, the limited sample size leads to insufficient statistical power and a risk of Type II errors, which may affect the accuracy of the results. The lack of tracking long-term efficacy and changes in biological markers also limits the assessment. Subsequent studies should be conducted within a multi-center, large-sample, long-follow-up framework, employing rigorous control designs and multimodal biomarker analyses to validate the reliability and generalizability of the research findings.

In this study, it was shown that acupuncture treatment had a significant effect on depression in adolescents. Additionally, it was found that four weeks of acupuncture combined with antidepressants was superior to either acupuncture or antidepressants alone, thus showing significant advantages of acupuncture in improving the anxiety/somatization and sleep disorders of patients. The study showed that acupuncture increased the levels of serum 5-HT, KynA, DA, NE, E, His and PA in adolescents with depression, supports a causal relationship between depression and RS-fMRI and that acupuncture modulates the level of excitability of emotion-related brain regions (including frontal lobe, CAU and ACG) and the FC of depression-related circuits (DMN, LCSPT circuit and a hate circuit). Further, a correlation was found between HAMD-24 scores and the mechanism-related objective indicators studied. Results confirm the efficacy of acupuncture in treating adolescent depression, suggesting potential mechanisms through the regulation of HAMD-24 factor scores, serum neurotransmitters levels and RS-fMRI findings. This provides a degree of evidence supporting acupuncture as a viable treatment for adolescent depression.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

JLJ: Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. BHJ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—reviewing and editing, Project administration. WJ: Formal analysis, Data curation, Project administration, Writing—review & editing. PYZ: Investigation, Data curation, Project administration, Writing—review & editing. HRC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Supervision, Project Administration, Writing—review & editing. WJC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Supervision, Project Administration, Writing—review & editing. XQJ: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing—reviewing and editing. LHL: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing—reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Our study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (2021-KL-075-01), the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (KY2021-123) and Wenzhou Seventh People’s Hospital (2022-Y26). All patients and their legal guardians provided written informed consent.

We would like to thank all the patients who made it possible for us to conduct this study.

The study is supported by Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Zhejiang Province (No. 2022ZQ072); Key Research and Development Project of Zhejiang Province (No. 2024C03208); Inheritance Studio of the Xiaoqing Jin Famous Chinese Medicine Experts in China (Grant number 2022 No.75); Inheritance Studio of Xiaoqing Jin Famous Chinese Medicine Experts in Zhejiang Province (Grant number GZS2021011).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/JIN38071.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.