1 Central Laboratory, The First Affiliated Hospital of Henan Polytechnic University (Jiaozuo Second People’s Hospital), 454001 Jiaozuo, Henan, China

2 School of Medicine, Henan Polytechnic University, 454000 Jiaozuo, Henan, China

Abstract

Epilepsy, a significant neurological condition marked by the occurrence of repeated seizures, continues to pose a substantial health challenge. Previous studies have indicated that Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitors may possess antiepileptic properties. Ferroptosis, a newly discovered type of programmed cell death, has recently surfaced as a promising therapeutic target in the management of epilepsy. Nevertheless, the exact mechanisms responsible for the effects of DPP4 inhibitors have not yet been fully elucidated.

The anti-epileptic effect was evaluated through electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings, behavioral assessments, and immunohistochemical analysis in a mouse model of epilepsy induced by LiCl/Pilocarpine. Public RNA-sequencing data was used to search the key targets of epilepsy. Neuronal ferroptosis was assessed through western blotting and immunofluorescence in an epilepsy rat model and a glutamate-induced neuronal cell model.

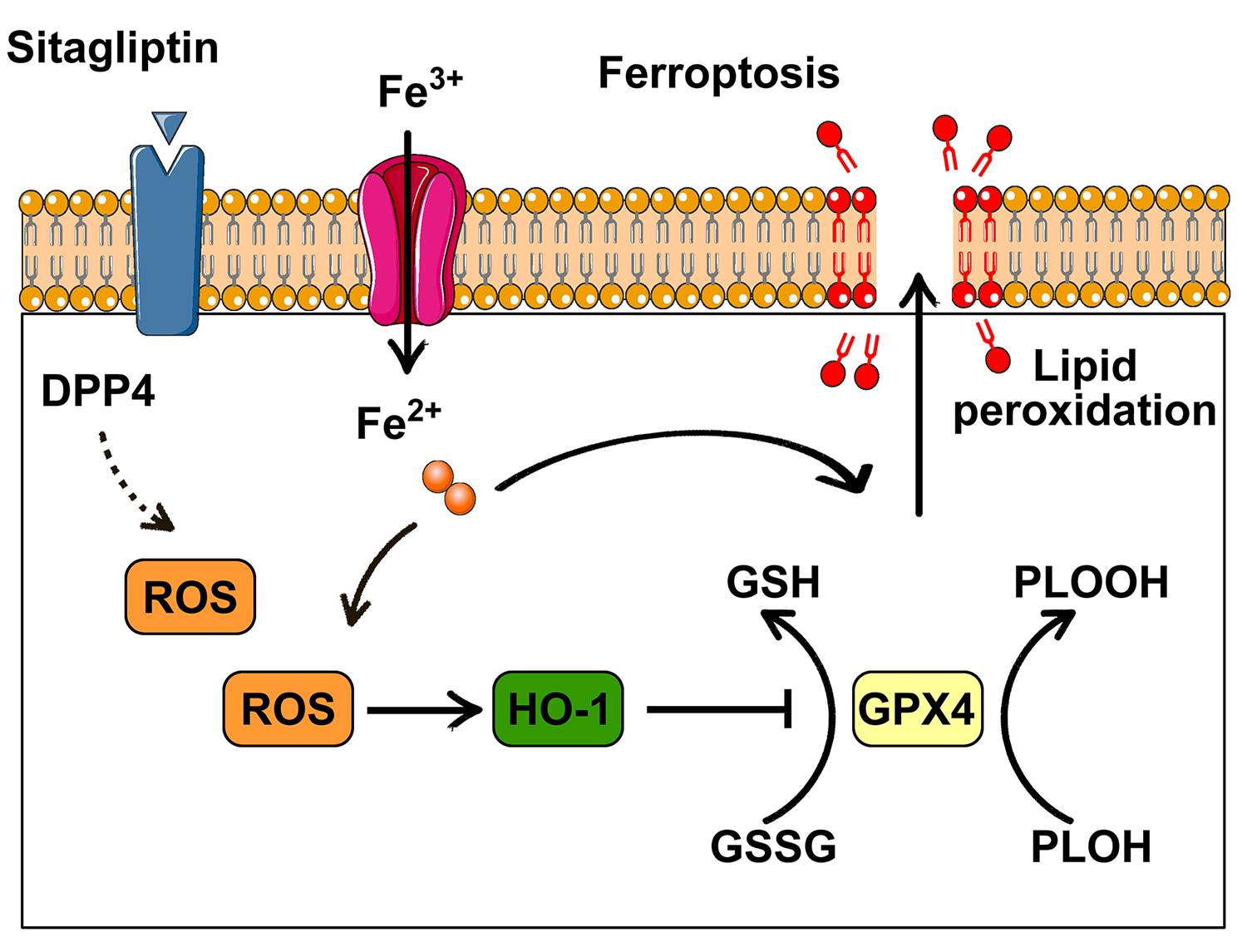

Administration of the DPP4 inhibitor sitagliptin was observed to markedly reduce seizure severity in an animal model of epilepsy. Furthermore, sitagliptin effectively diminished epileptiform activity, as assessed by EEG. Additionally, pretreatment with sitagliptin led to a notable decrease in the expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and mitochondrial damage, while increasing glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) expression in the epilepsy rat model. Similar effects were observed in cell-based experiments, where sitagliptin pretreatment enhanced GPX4 expression in glutamate-induced neuronal models.

The DPP4 inhibitor sitagliptin mitigates ferroptosis in epilepsy models. These findings highlight new potential targets and treatment modalities for epilepsy.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- ferroptosis

- dipeptidyl peptidase-4

- epilepsy

- heme oxygenase-1

- glutathione peroxidase 4

Epilepsy represents a chronic neurological condition distinguished by the occurrence of recurrent seizures, and it impacts approximately 1% of the worldwide population [1]. Despite advancements in antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), a substantial number of patients remain resistant to treatment [1]. Thus, the discovery of new anti-epileptic medications with improved efficacy and safety profiles is essential.

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4), which is also referred to as CD26, functions as a serine protease and plays a regulatory role in the activity of diverse bioactive peptides [2]. In addition, DPP4 participates in multiple biological processes that are implicated in inflammation and tumorigenesis [3]. DPP4 inhibitors reduce the neuron damage and cognitive deficit in cerebral hypoperfusion models [4]. Additionally, DPP4 inhibitors exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, rendering them as promising candidates drugs for the treatment of central nervous system disorders [5]. DPP4 inhibitors may possess antiepileptic properties. However, the mechanisms underlying these effects remain to be fully understood.

Ferroptosis, a recently discovered type of programmed cell death, makes garnered significant attention [6]. A key indicator of ferroptosis is the dysfunction of the antioxidant stress signaling pathway, particularly glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) [6]. From a functional perspective, neuronal ferroptosis plays a role in the advancement of central nervous system diseases [7]. Prior studies have additionally underscored that neuronal ferroptosis is implicated in the pathomechanism of epilepsy across various animal models [8]. Therefore, regulating ferroptosis presents a potential therapeutic strategy for epilepsy. This study investigated whether the DPP4 inhibitor sitagliptin exerts its anti-epileptic effects by modulating ferroptosis.

All experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee at Henan Polytechnic University. Adult male rats, weighing between 220 and 250 grams, were maintained in an environment with standard conditions, including a temperature range of 22 to 24 ℃. The rats had unrestricted access to both food and water. The rats were randomly divided into three groups (6 rats per group): (1) Control group (Ctrl), in which rats received 0.9% saline; (2) Pilocarpine epilepsy model group (Pilo), in which rats received an intraperitoneal administration of LiCl (127 mg/kg, L9650, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) followed 19 hours later by pilocarpine (35 mg/kg, i.p., Sigma). Thirty minutes before pilocarpine administration, atropine sulfate (1 mg/mL, A822893, MACKLIN, Shanghai, China) was given to attenuate peripheral cholinomimetic symptoms. Seizure severity was evaluated using Racine’s scale, with generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS) categorized as stage 6. Only the model reaching stage 4 (rearing) or above stage 4 is considered successfully constructed. This allows for subsequent experiments to be conducted. The onset of status epilepticus (SE) was noted when seizures reached stage 4. After one hour of SE onset, diazepam (10 mg/kg, H23021885, HAPHARM, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China) was administered to stop seizures; (3) Pilo + sitagliptin group (Pilo + Sita), in which rats were pretreated with sitagliptin (50 mg/kg/day, S832608, MACKLIN) for 5 days, followed by the lithium chloride, atropine sulfate and pilocarpine injection.

To obtain EEG recordings, rats were rendered unconscious with pentobarbital (30 mg/kg, P3761, Sigma) anesthesia. They were then immobilized in a stereotaxic apparatus (Zhongshi, Beijing, China) to ensure precise positioning. Stereotaxic coordinates targeting the hippocampus were utilized: –3.8 mm posterior to bregma, 3.5 mm lateral to the midline, and 3.8 mm ventral to the dura, for electrode placement. Post-surgery, rats were administered buprenorphine (0.5 mg/kg, 110483373347, Par Pharmaseutical, LA, USA). One week after the operation, the epilepsy model was induced. EEG recordings were sampled at 10 kHz with a 1.0 Hz high-pass filter and a 1 kHz low-pass filter. Fast Fourier transform analysis of EEG data was conducted using LabChart software (v8.1, AD Instruments, Bella Vista, Australia).

To investigate gene expression alterations for seizures, Gene Expression Omnibus 2R (GEO2R, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used for differentially expressed genes analysis between epilepsy group and normal group from gene expression omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Default parameters included the Benjamini & Hochberg method for multiple testing correction (adjusted p-value

Twenty-four hours following epilepsy model induction, rats were subjected to deep anesthesia using pentobarbital. Subsequently, they underwent perfusion, first with 0.9% saline and then with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, BL539A, Biosharp, Hefei, Anhui, China). The perfused brains were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for an additional 24 hours. Following this, brains were sectioned into 4-µm thick slices. Nissl staining was employed to evaluate hippocampal neurons damage. Survived neurons were counted under microscope (

HT22 hippocampal neuronal cells (CL-0697, Procell system, Wuhan, China) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, L110KJ, Yuanpei, Shanghai, China) medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, C0232 Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and a moderate concentration of penicillin-streptomycin solution. All cell lines were validated by autosomal short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma. Glutamate-induced excitotoxicity was employed as an in vitro model of epilepsy. HT22 cells were randomly assigned to three groups: (1) the control group (Ctrl), where HT22 cells were cultured without any treatment; (2) the glutamate group (Glu), where HT22 cells were treated with 5 mM glutamate (G6204, MACKLIN) for 24 hours; and (3) the Glu + sitagliptin group (Glu + Sitagliptin), where cells were pretreated with 50 µM sitagliptin for 2 hours, followed by 5 mM glutamate treatment for 24 hours.

Twenty-four hours after epilepsy model induction, hippocampal tissue and cultured cells were collected. Protein was extracted using Radio Immunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (P0013B, Beyotime Biotechnology) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (P1005, Beyotime Biotechnology) to prevent protein degradation. The concentrations of different groups were quantified by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit (P0011, Beyotime Biotechnology). Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels were used for separation base on molecular weight. Then, the Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) were used for transfer and immunoblotting. To minimize non-specific antibody binding, membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature (RT) and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Then the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at RT. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (P0018S, Beyotime Biotechnology) and detected with a chemiluminescence imaging system (ChemiDoc XRS+ System, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (v1.51, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Following treatment, cells from different groups were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, BL539A, Biosharp) and permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 (T6328, MACKLIN). After blocked, cells were incubated with GPX4 antibody and the corresponding secondary antibodies (EarthOx), protected from light. 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; D9542, Sigma) was used visualize nuclei. Fluorescence imaging was captured using Leica fluorescence microscope, and the analysis were performed by ImageJ software.

For immunofluorescence labeling of brain tissue, the slices were blocked with 5% BSA, GPX4 antibody and NeuN antibody were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Then, slices were incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies at RT and DAPI to stain nuclei. Image capture and analysis were performed using a Leica fluorescence microscope and ImageJ software.

The primary antibodies: GPX4 (1:200, 30388-1-AP, Proteintech) and NeuN (1:500, 66836-1-Ig, Proteintech). Secondary antibodies: DyLight 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500, E032210, EarthOx) and DyLight 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500, E032420, EarthOx).

Brain tissue slices (4 µm thickness) underwent deparaffinization in xylene (X823028, MACKLIN) followed by rehydration using a descending alcohol gradient. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwave heating. Slices were incubated with 3% H2O2 (H792073, MACKLIN) and 5% normal goat serum (C0265, Beyotime Biotechnology) at RT. Then NeuN antibody and corresponding secondary antibody were incubated. After three PBS washes, slices were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (ZLI-9017, ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China). Microscope (Ci-E, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and ImageJ software were employed for visualization and quantification respectively.

Primary antibodies used were NeuN (1:500, 26975-1-AP, Proteintech), and the secondary antibody was HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500, E030120, EarthOx).

Frozen brain sections were exposed to 10 µM dihydroethidium (S0063, Beyotime Biotechnology) for reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection, followed by fluorescence microscopy imaging (Leica).

For TEM, tissues underwent overnight fixation in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (G916055, MACKLIN) at 4 °C, followed by Epon (02660-AB, Ted Pella Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA) embedding and staining with 2% uranyl acetate (02624-AB, Ted Pella Inc.) and 0.04% lead citrate (L885990, MACKLIN) on 200-mesh copper grids (WTMTW-200, Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China). Mitochondrial morphology was examined using a transmission electron microscope (HT7800, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Data are presented as mean

To assess the antiepileptic effects of sitagliptin, epileptic seizures were first evaluated via EEG recordings. The results revealed that sitagliptin pretreatment significantly reduced seizure activity (Fig. 1A), with a marked decrease in amplitude in the pretreatment group compared to the epilepsy group (F (2, 15) = 19.71, p = 0.0004) (Fig. 1B). Behavioral testing in the LiCl/Pilocarpine-induced epilepsy model further demonstrated that sitagliptin pretreatment significantly reduced seizure severity (F (2, 17) = 43.17, p = 0.0017) and prolonged the latency to the first GTCS (F (2, 15) = 90.46, p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Sitagliptin pretreatment significantly reduced epilepsy severity. (A) Representative EEG traces of electrographic activity from the Ctrl, Pilo, and Pilo + sitagliptin groups. (B) Local maximum amplitude of EEG data. (C) Sitagliptin pretreatment decreased seizure severity compared to the Pilo group. (D) Sitagliptin pretreatment increased latency to the first GTCS. Data are presented as the mean

To explore whether sitagliptin pretreatment alleviated neuronal loss in the epilepsy model, H&E, Nissl staining, and NeuN immunostaining were performed. As shown in Fig. 2A,B, H&E and Nissl results demonstrated that hippocampal neurons in the epilepsy group exhibited significant damage compared to the control group (F (2, 6) = 59.29, p = 0.0001). In contrast, the sitagliptin pretreatment group demonstrated reduced neuronal loss (p = 0.0005). The same result was obtained by NeuN immunostaining (Fig. 2C), the neuronal damage in sitagliptin pretreatment group was significantly improved (F (2, 6) = 73, p = 0.0002). These results suggested that sitagliptin exerts a protective effect against hippocampal neuronal degeneration in the LiCl/Pilocarpine-induced epilepsy model.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Sitagliptin pretreatment prevented neuronal loss in rat hippocampus. (A) Representative H&E staining, the red arrow indicates the damaged neurons. (B) Nissl staining, and (C) NeuN immunostaining of hippocampal CA1 regions in the Ctrl, Pilo, and Pilo + sitagliptin groups. The scale bar = 50 µm. Data are presented as the mean

To investigate the gene expression profile associated with epilepsy, a comprehensive analysis of five independent GEO datasets was conducted. Both upregulated and downregulated genes were identified (Fig. 3A). Intersection analysis revealed 11 genes with consistent expression patterns across the datasets: zinc finger protein 36 (ZFP36), heat shock protein family b (small) member 1 (HSPB1), cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1a (CDKN1A), inhibin subunit beta a (INHBA), tubulin beta 6 class v (TUBB6), activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), purinergic receptor p2y12 (P2RY12), adam metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 1 (ADAMTS1), bag family molecular chaperone regulator 3 (BAG3), fbj murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog (Fos) and HO-1 (Fig. 3B–D). Among these, HO-1 plays a pivotal role in the pathological mechanisms underlying multiple central nervous system (CNS) disorders [9]. The effect of sitagliptin on HO-1 expression was then examined. Consistent with GEO database results, immunohistochemistry analyses showed a significant increase in HO-1 expression in the epilepsy group compared to the control group (F (2, 6) = 21.24, p = 0.0016) (Fig. 3E). However, sitagliptin pretreatment significantly reduced HO-1 expression (p = 0.0144) (Fig. 3E). The same result was obtained by Western blot (WB) analyses (Fig. 3F), the HO-1 expression in sitagliptin pretreatment group was significantly decreased (F (2, 6) = 61.79, p = 0.0002). All original WB figures in Fig. 3F are provided in the Supplementary material. These results suggested that HO-1 may be involved in the antiepileptic effects of sitagliptin.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. HO-1 expression is upregulated in the epilepsy model. (A) Histogram showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (red, upregulated genes; blue, downregulated genes). (B,C) Intersection analysis across five databases identified eleven commonly altered genes. (D) Heatmap of HO-1 mRNA levels. (E) Representative images and statistical analysis of HO-1 immunostaining in different groups. The scale bar = 50 µm. (F) Western blot (WB) detection of HO-1 in different groups, with relative expression normalized to

HO-1 overexpression may be linked to the accumulation of iron resulting from HO-1 catabolism [10]. Additionally, ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death, is associated with the accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides [11]. To investigate the role of sitagliptin in neuronal ferroptosis in epilepsy, several ferroptosis-related biomarkers were assessed. DHE staining revealed elevated neuronal ROS production in the epilepsy group compared to the control group (F (2, 6) = 13.36, p = 0.0095), while sitagliptin pretreatment significantly reduced ROS levels (p = 0.0106) (Fig. 4A,B). TEM analysis further revealed that the epilepsy group displayed mitochondrial damage and increased membrane density (Fig. 4C). However, sitagliptin pretreatment markedly alleviated mitochondrial damage (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Sitagliptin pretreatment ameliorated ROS production and mitochondrial damage. (A,B) Fluorescence staining of DHE used to detect ROS levels in different groups. The scale bar = 50 µm. (C) TEM analysis of mitochondrial damage in different groups. The scale bar = 0.5 µm. Data are presented as the mean

Next, GPX4 expression was examined. As shown in Fig. 5, GPX4 levels were downregulated in hippocampal neurons of the epilepsy group compared to the control group (F (2, 6) = 21.63, p = 0.0026), and this expression was significantly upregulated following sitagliptin pretreatment (p = 0.0036).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Immunofluorescence with GPX4 and NeuN antibodies identified neuronal status of ferroptosis in different groups. The scale bar = 50 µm. Data are presented as the mean

Furthermore, GPX4 expression was assessed by immunofluorescence and WB in the glutamate-induced neuronal death models. As shown in Fig. 6A,B, compared to the control group, the glutamate group exhibited reduced GPX4 expression (F (2, 6) = 28.56, p = 0.0031). However, sitagliptin pretreatment significantly increased GPX4 levels (p = 0.0009). The same result was confirmed by WB analysis, GPX4 expression in sitagliptin pretreatment group was significantly decreased (F (2, 6) = 50.08, p = 0.0069) (Fig. 6C). All original WB figures in Fig. 6C are provided in the Supplementary material. These results collectively demonstrate that sitagliptin significantly reduces ferroptosis in both LiCl/Pilocarpine-induced epilepsy and glutamate-induced neuronal death models.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Sitagliptin attenuated neuronal ferroptosis in neuronal models. (A,B) Immunostaining and statistical analysis for GPX4 expression in different groups. The scale bar = 100 µm. (C) WB detection of GPX4 in different groups, with relative expression normalized to

Hippocampal neuron loss is a pivotal pathological process underlying the development of epilepsy [12]. Previous research has primarily focused on two forms of hippocampal neuronal death: apoptosis and necrosis [12]. Apoptosis is often triggered by abnormal neuronal electrical activity, such as calcium overload [13]. Ferroptosis, a newly recognized form of regulated cell death, has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of epilepsy [6]. Inhibiting ferroptosis has emerged as a potential strategy for treating epilepsy. DPP4 (also known as CD26) inhibitors, initially developed for managing type 2 diabetes, have shown potential in modulating central nervous system (CNS) disorders by targeting neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and neuropeptide regulation [14]. These inhibitors increase the bioavailability of neuroprotective substrates, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which enhances neuronal survival, suppresses release of IL-1

HO-1 (also known as HOMX1) is a stress-inducible enzyme [10]. Research indicates that ferroptosis mediated by HO-1 is a significant contributor to the development of diabetic nephropathy [18]. Furthermore, one of environmental pollutants, di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate, have been shown to induce ferroptosis through the HO-1 signaling pathway [19]. HO-1 is regarded as a key regulator of ferroptosis [8]. In the present study, GEO data analysis confirmed that HO-1 expression was significantly elevated in various epilepsy models, suggesting its involvement in epilepsy-related ferroptosis [20]. Our results also demonstrated that sitagliptin pretreatment significantly reduced HO-1 expression. Additionally, other key ferroptosis-related targets, including ROS production, mitochondrial damage, and GPX4 downregulation, were evaluated. Results indicated that the epilepsy model exhibited higher neuronal ROS production, marked mitochondrial damage, and reduced GPX4 expression, all of which were significantly improved by sitagliptin pretreatment. Similar findings were observed in cell-based experiments, where sitagliptin pretreatment also significantly increased GPX4 expression in glutamate-induced neuronal models. In addition to HO-1 and GPX4, there are other ferroptosis regulatory factors, such as ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) and Acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4) may also be involved [21]. But unfortunately, these were not detected in this study. Subsequently, we will further detect the changes of the ferroptosis related proteins. Furthermore, this research was limited to animal and cell models, and there was a lack of verification of the long-term administration effect.

In conclusion, the DPP4 inhibitor sitagliptin can ameliorate oxidative stress, protect against mitochondrial damage, inhibit ferroptosis, and exert antiepileptic effects. These findings may provide novel targets and therapeutic strategies for the treatment of epilepsy.

The data for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conceptualization, BH and JG; GraphPad Prism Software and ImageJ Software, BH and FW; validation, LL; Formal analysis, BH; Data curation, BH and FW; Writing—original draft preparation, BH; Writing—review and editing, JG; Funding acquisition, LL, FW, and JG. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the American Veterinary Medical Association Guidelines and approved by the Committee on Ethics of Animal Experiments of Henan Polytechnic University (permit number: 20230607).

Not applicable.

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 32300803), the 2023 Key Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Science and Technology Department (232102310148, 232102310259), the 2024 Key Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Science and Technology Department (242102310275), and the Doctoral Fund Project of Henan Polytechnic University (B2021-68).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/JIN39469.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.