1 Faculty of Health Sciences, Ontario Tech University, Oshawa, ON L1G 0C5, Canada

2 Center of Chiropractic Research, New Zealand College of Chiropractic, 1060 Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

Sensory feedback from the upper cervical regions is used by the central nervous system to stabilize the occipito-atlantal (C0-C1) joint for leveled vision and to assess head position, which is used in sensorimotor integration (SMI) of neck and upper limb motor control. However, few studies have specifically investigated the impact of C0-C1 dysfunction and/or its rectification on SMI related outcomes. This study sought to determine the impact of restricted C0-C1 mobility and musculoskeletal pain on neck and upper limb motor control, whether these motor control deficits persist without treatment, and whether motor control improves following treatment designed to improve C0-C1 mobility.

Twenty-two participants with restricted C0-C1 mobility attended three data collection sessions (baseline, control (2 to 5 days later), and post-treatment) at a private clinic. The One-to Zero (OTZ) system which treats the C0-C1 first followed by other spinal regions if clinically indicated, was administered twice weekly until participants reached 80% improvement from baseline symptoms. Shoulder range of motion, peak force and electromyography during maximal resisted scapular elevation (upper trapezius) and neck flexion (sternocleidomastoid), peak grip, and quadricep strength were measured before and after treatment. Repeated measures ANOVAs with pre-planned contrasts (e.g., control to baseline, and post-treatment to baseline) were conducted.

Neck and limb control impairments persisted without treatment, with no changes between the double baseline (p > 0.05). Shoulder abduction and extension, and peak force output of the sternocleidomastoid, upper trapezius, and quadriceps improved post-intervention (all p < 0.05).

Selective improvement in neck and limb motor control outcomes post-treatment suggests that increased corticospinal drive/motor neuron excitability from normalized afferent input may impact gross motor output first.

ACTRN12625000627459. https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=389394&isReview=true.

Keywords

- motor control

- occipito-atlantal joint dysfunction

- musculoskeletal pain

- spinal manipulation

The execution of a smooth movement is dependent on peripheral and central mechanisms [1]. The peripheral input (i.e., receptors within the muscles, joints, and etc.) that is transmitted to the central nervous system is processed and evaluated in order to create a motor program that fits the demands of the movement, a process known as sensorimotor integration (SMI) [2]. This ability to coordinate and control synergistic actions of motor units within a single muscle and/or or several muscles is referred to as motor control [1]. This occurs naturally; however, SMI may be disrupted to the point it leads to maladaptive motor control, especially following musculoskeletal pain, injury and/or due to resulting spinal dysfunction [3].

Spinal dysfunction refers to restricted joint movement and tenderness in the spine [4, 5], that commonly persist following spinal injury and/or pain and is recognized as a biomechanical lesion of the vertebral column by the World Health Organization (ICD-10-CM code M99.1) [6]. Characteristics of joint dysfunction include tight vertebral muscles, decreased intervertebral movement, and tenderness to touch [7]. When spinal dysfunction persists over weeks, month or even years, it provides an opportunity to study the impact of chronic changes in sensory feedback from dysfunctional regions [3]. Past research has shown that neck dysfunction impacts upper limb motor control [3], scapular kinematics [8] and orientation [9], and increases neck muscle myoelectric activity [10, 11], and muscle activation patterns in accessory neck muscles during upper limb movement [12]. The neuromuscular efficiency of superficial cervical flexor muscles, the ratio between the amount of myoelectric activity and associated force [13], reflects overall motor control strategies. This is reduced in individuals with chronic neck pain under low load contractions [13]. Neck sensory input is also used by the central nervous system for limb control. Altered SMI from disordered neck sensory input influences upper limb function [14] as there is a relationship between the integrity of the corticospinal system and task-dependent grip force generation [15]. Additionally, back and/or knee pain decreases strength of the hip flexors and quadriceps [16, 17], likely due to increased inhibitory activity/decreased cortico-spinal drive within the reflex neural outputs.

Spinal dysfunction in conjunction with occipito-atlantal (C0-C1) joint dysfunction(s) is also likely to yield impairments in motor control. The C0-C1 joint complex will impact and alter motor control, due to maladaptive SMI with its sensorimotor connections due to the number of deep suboccipital muscles. The suboccipital muscles (rectus capitis posterior major and minor, and obliquus capitis superior and inferior) have a high density of muscle spindles, which projects sensory input to the caudal brainstem, rostral spinal cord and ipsilateral lateral cuneate nucleus [18, 19]. This information is transmitted to the cortex via the dorsal column medial meniscus pathway alongside the ascending cuneocerebellar and rostral spinocerebellar tracts [20]. Sensory feedback from the upper cervical regions is used by the central nervous system to stabilize the C0-C1 joint in the sagittal and coronal plane (for leveled vision) [19, 21] and to assess head position, which is used in SMI of neck and upper limb motor control by the descending corticospinal and corticobulbar tracts [20]. Thus, while several studies have investigated the impact of neck dysfunction on upper limb motor control, very few have specifically investigated C0-C1 dysfunction and/or the rectification of this dysfunction using spinal manipulation specifically targeting this region prior to other regions on motor control of the neck, upper and lower limb.

Translatoric mobilization of the C0-C1 for 5-minutes in individuals with chronic neck pain alone yields improvements in upper cervical spine mobility and the pressure pain threshold of the right trapezius and right splenius [22]. Six sessions of C0-C1 translatoric mobilization and physical therapy of the cervical spine [23] or 20 minutes of manipulation and/or mobilization of the C0-C1 and C2-C3, with cervical exercises [24] improve passive upper cervical spine mobility in individuals with chronic neck pain. The improvements following manipulation and/or mobilization with exercises are immediate, with decreases in pain intensity and increases in active cervical range of motion [24]. Improvements in active shoulder abduction range and shoulder pain intensity occur following a series of treatments that include high-velocity, low amplitude thrusts at the C0-C1, known as the One-to-Zero (OTZ) tension adjustment, and thoracic spine manipulation, in those with frozen shoulder syndrome accompanied by C0-C1 joint dysfunction(s) [25]. Manipulation of the C0-C1 joint complex (OTZ tension adjustment) before and alongside other dysfunctional spinal regions (the OTZ system) may have restored normal function at the C0-C1 by improved central processing from normalized sensory feedback. This may have led to improvements in gross motor function of the shoulder girdle via improved upper trapezius and sternocleidomastoid (SCM) function, muscles commonly affected in frozen shoulder syndrome [26, 27]. Given the neurophysiology of the upper cervical region, it is likely that C0-C1 dysfunction may also present with impairments in neck, upper and lower limb motor control, and may improve in response to the OTZ system.

Past work has demonstrated restored SMI and motor control following manipulation/adjustment of dysfunctional spinal regions showing tenderness and decreased movement [4, 5], in response to cervicothoracic or lumbosacral manipulation [3]. There were immediate reductions in electromyographic (EMG) activity of the SCM [28], and a greater EMG response in the upper trapezius [29] following upper thoracic spine manipulation, dependent on neck pain severity. Combined upper and lower cervical spine manipulation leads to a greater EMG response in the SCM along with increased anterolateral neck flexor strength in those with neck disability [29, 30]. Neuromuscular drive (i.e., overall motor unit recruitment) to the axioscapular muscles during arm elevation immediately increases following thoracic manipulation in those with shoulder pain [31]. Grip strength improves following lower cervical spine manipulation [32] and after 3 weeks of neck manipulation [33] in athletes, and in those with chronic neck pain, after cervical or thoracic spinal manipulation [34]. Lower limb strength improves immediately after spinal adjustments [35], or following sacroiliac joint manipulation [36], irrespective of pain location. Manipulation or adjustment of the dysfunctional spine improves neuromuscular function or strength of the neck, and limbs, resulting in increased corticospinal drive/excitability likely due to improved SMI [3, 35]. Spinal manipulation increased force production, accompanied by and increased V-wave to maximal M wave (Vmax/Mmax) ratio, indicative of increased cortical drive [35]. In study involving spinal manipulation of dysfunctional joints in the neck, that used transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), there was an increase in short interval cortical facilitation (SICF), a decrease in short interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) and a shorted cortical silent period of the abductor pollicis brevis muscles, with reciprocal changes in the extensor indicis muscle [37]. A study by Baarbé et al. [38] used dual pulse TMS to investigate the impact of neck spinal manipulation on cerebellar disinhibition in response to acquisition of a novel motor task in those with recurrent neck pain. The neck pain group receiving manipulation prior to motor acquisition showed disinhibition levels even greater than shown by healthy controls, while the non-treated neck pain group showed no disinhibition at all. Combined, these studies indicate that spinal manipulation can decrease cortical and/or spinal inhibition and improve cortical drive, but very few studies which have specifically studied whether the manipulation of C0-C1 region in addition to other regions yields similar improvements.

Given the neurophysiology of the region with its rich proprioceptive innervation [19], it is important to know whether individuals with C0-C1 joint dysfunction and musculoskeletal pain exhibit altered neck and limb control, which persists without treatment and improves in response to treatment with the OTZ system. This quasi-experimental longitudinal repeated measure study design investigated the impact of the OTZ system (pragmatic treatment method) on neuromuscular function of the neck, as well as force production of the upper and lower limbs in those with C0-C1 joint dysfunction and chronic musculoskeletal problems, where participants were acting as their own control. It was hypothesized that in the absence of treatment there would be continued deficits, while there would be improvements following the OTZ system in shoulder range of motion, neuromuscular function and force production of the upper and lower limb. Additionally, the study included effect sizes to inform power calculations for future randomized controlled trials.

Eighteen participants were required according to a priori power analysis for 1 group and 3 repeated measures conducted with G*power version 3.1.9.7 (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) (f = 0.4,

Participants aged 18- and 65-years seeking chiropractic care from a private chiropractic practice in Toronto, Canada were screened for C0-C1 joint dysfunction(s). This practice was chosen as the chiropractor had over 30 years of clinical experience and advanced training in the OTZ system, and patients with C0-C1 dysfunction were routinely referred there. Participants were recruited via posters in the practice reception area and receptionists asked participants if they were interested in being part of the study, as which point they would be assessed by the chiropractor. To assess eligibility, the chiropractor performed skull glide assessments along the C0-C1 [25] to identify the joint dysfunction(s) and their orientation. As mentioned, joint dysfunction is reflected by tenderness of the joint upon touch, reduced movement of the intervertebral segments, imbalances in muscle tightness, and abnormalities or blocked joint play and end-feel [7]. These biomechanical impairments within the spinal segments indicated if it was clinically necessary to administer a spinal adjustment. Screening included individuals complaining of reduced shoulder range of motion, and/or recurrent unilateral or bilateral musculoskeletal problems, such as pain, stiffness or reduced mobility of the joints and/or extremities [25].

Participants were ineligible if they reported any of the following during the screening and medical history review: neurological conditions or residual symptoms from a recent head injury, chiropractic intervention within the past 6 months, or contraindications to chiropractic care. Participants were eligible to participate in this longitudinal observational study if they had chronic musculoskeletal problems with C0-C1 joint dysfunction(s), and no recent head injuries or contraindications to chiropractic care.

Upon confirmation of eligibility, the chiropractor informed the researcher, who then emailed participants with the study details and the informed consent form. Online consent was obtained via email, followed by booking a baseline data collection session. On the day of data collection, the researcher obtained verbal and written informed consent prior to collecting measurements. All participants who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate.

This study was conducted at a private practice in Toronto, Canada, in compliance with the Ontario Tech University’s Research Ethics Board (File #: 14817). Recruitment took place between June 11, 2018 and January 4, 2019 with the final data collection taking place on May 27, 2019. This study adheres to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies (https://www.strobe-statement.org/checklists/) (Supplementary material-STROBE checklist). It is registered with the Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12625000627459).

Participants received a symptom-specific chiropractic intervention using the OTZ system. This system focuses on addressing C0-C1 joint dysfunction(s) followed by other spinal joints, working in a cephalocaudal direction until mobility of affected regions is improved and/or no longer requires treatment.

During each session, the chiropractor identified the areas of joint dysfunction using the biomechanical indictors [7]. For the C0-C1 joint, a skull glide was used [25]. For other spinal joints, common standards of practice were followed, including palpation for joint tenderness and intervertebral muscle tension, assessment of range of motion, joint play, and end-feel [40, 41].

The chiropractor applied a high-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) thrust along the C0-C1 joint, known as the OTZ tension adjustment [25]. A single adjustment was applied to the side with the greatest restriction, followed by the other side, only if it also showed restricted movement. “The practitioner’s index finger contacted the C1 lamina on the side of restricted movement. The line of drive of the thrust was posterior to anterior, lateral to medial, and slightly superior to inferior along the C0-C1 articulation” [25]. This was performed while the participant sat facing away from the chiropractor. Following the OTZ adjustment, HVLA adjustments or mobilization techniques were applied to other dysfunctional joints, including the mid-thoracic and lumbosacral regions. As part of the chiropractor’s standard practice, participants received adjunct treatment (e.g., massage therapy) for accompanying myofascial pain and were instructed to walk for 30 minutes within 24 hours of the OTZ adjustment.

The total number of treatments varied amongst participants based on the chronicity and severity of their musculoskeletal problems and the improvement of C0-C1 joint function. The treatment was complete when participants achieved 80% recovery from their initial visit. Participants were treated twice a week for 2.5 to 7.5 weeks (5 to 15 treatments), with two individuals requiring 21 and 23 visits, respectively.

An 80% recovery threshold was used to standardize the end point across participants. This marked the resolution of C0-C1 dysfunction and the transition to maintenance care for remaining symptoms. The chiropractor assessed improvement at each treatment using a global assessment of function and pain rating [42]. Before the first treatment, participants were asked to describe their current state (i.e., symptomology, mobility, and pain), recorded as 10/10 at baseline. A decrease in score indicated an improvement from baseline symptom presentation. The intervention concluded when participants reported a score of 2 (representing 80% recovery from initial visit), and the chiropractor confirmed concomitant improvement of C0-C1 joint mobility using the skull glide technique [25]. At this point, participants were ready for their post-OTZ measurement session with the researchers. It is important to note that participants were not informed in advance that 80% improvement would trigger the follow-up assessment, as we wanted to decrease subjective reporting bias.

In this repeated measures within subject feasibility study, participants attended three data collection sessions with the researchers. During these sessions, the following data were collected: shoulder range of motion (ROM), electromyography (EMG) and peak force of the upper trapezius and sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles, peak force of the upper arm (grip strength), and quadriceps. The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire was administered at the baseline and post-OTZ collection measures, to document changes in upper-extremity physical functioning and disability.

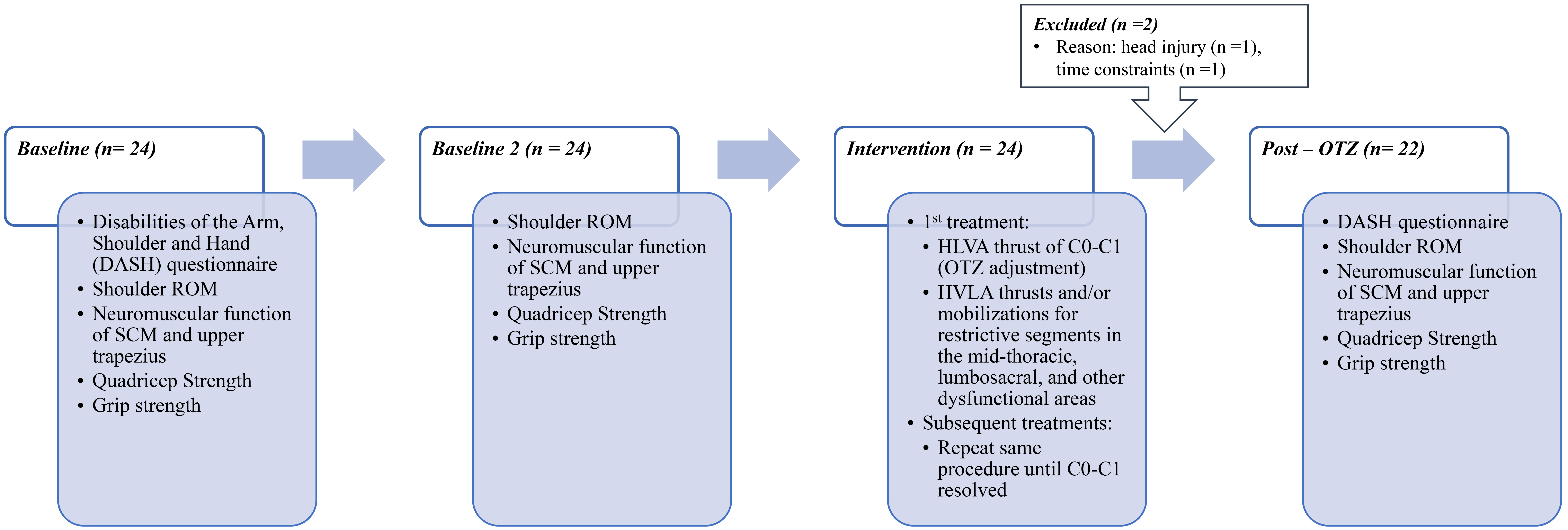

Baseline measures were completed within one week of confirming eligibility. After the initial baseline collection, participants were scheduled for a second baseline measurement session, conducted 2 to 5 days later and prior to the first intervention. During this control period, participants were instructed to refrain from receiving any type of intervention. This was intended to capture the effects of this dysfunction in the absence of treatment, control for potential familiarity or learning effects, and measurement stability. Immediately after the second baseline collection, participants attended their first treatment session with the chiropractor. Within a week of the final treatment session, participants attended the post-OTZ data collection session, which was arranged via email communication initiated by the researcher. See Fig. 1 for experimental protocol.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of experimental design. ROM, range of motion; SCM, sternocleidomastoid; C0-C1, occipito-atlantal; HVLA, high-velocity, low-amplitude; OTZ, One-to-Zero.

The DASH Outcome Measure, a validated self-report questionnaire [43, 44] that reliably assesses functional disability in various regions of the upper extremity at the moment of administration [44, 45, 46, 47], and changes over time [45, 48, 49]. DASH questionnaire has 30-items [45, 50]. Twenty-one items focus on the degree of difficulty when performing various physical activities, 5 item address the severity of upper-extremity symptoms, and 4 items are capture problems related to social activities, work, sleep and self-efficacy [45, 50]. The two optional modules (work and sports/performing arts) were also administered and completed if applicable, each consisting of 4 items. Each item is measured on a 5-point Likert scale, 0 to 4 [51]. The disability/symptom score was calculated by transforming the summed and averaged responses of at least 27 items to a score out of 100 (most severe disability) [51]. The minimum clinically important difference is 10.83 to 15 points [52], and the minimum detectable change is between 12.75% and 17.23% [53].

Shoulder abduction, flexion and extension were measured using a height adjustable wall goniometer (OTZ Health Education Systems, Dallas, TX, USA). Participants stood in anatomical position with their back against the height-adjustable wall goniometer, body aligned with the vertical line (0° to 180° marking) and horizontal line (shoulders aligned with the 90° marking), prior to performing pain-free shoulder ROM, as described by Murphy et al. [25]. The researcher stood two meters in front of the wall goniometer, to record shoulder motion using a cellphone camera so that the recorded angle could be documented and double-checked following data collection. Maximum ROM was measured as the alignment of the humerus along the angle gradations on the wall goniometer at the highest point.

Three, three-second long, trials were performed for each muscle of interest, with the first considered practice. A minute rest was provided between each maximum voluntary contraction (MVC). The last two MVCs were analyzed and utilized for statistical analysis.

A mechanical resistance was provided when participants performed MVCs of the SCM, upper trapezius, quadriceps and upper arm. A wooden platform housing a force transducer (Model: BG 500, Mark-10 Corporation, New York, NY, USA) and pulley system was used. It allowed for the thin wired cable connected to the force transducer to be attached to different attachment pieces (as needed for the muscle of interest). The cable was taut and formed a 90° angle between the attachment piece and the force transducer, maintained during each MVC.

Participants were instructed to pull against the force transducer while only engaging the muscle of interest, which was confirmed with during the first trial. Participants were also given verbal encouragement during each MVC, to ensure they provided their maximum effort where they neither felt pain or discomfort. MVCs of SCM and upper trapezius were performed in succession, whereas the quadriceps and upper limb were performed per side, alternatingly. Details on the MVCs procedures for each muscle of interest can be found in subsequent sections.

2.3.3.1 SCM

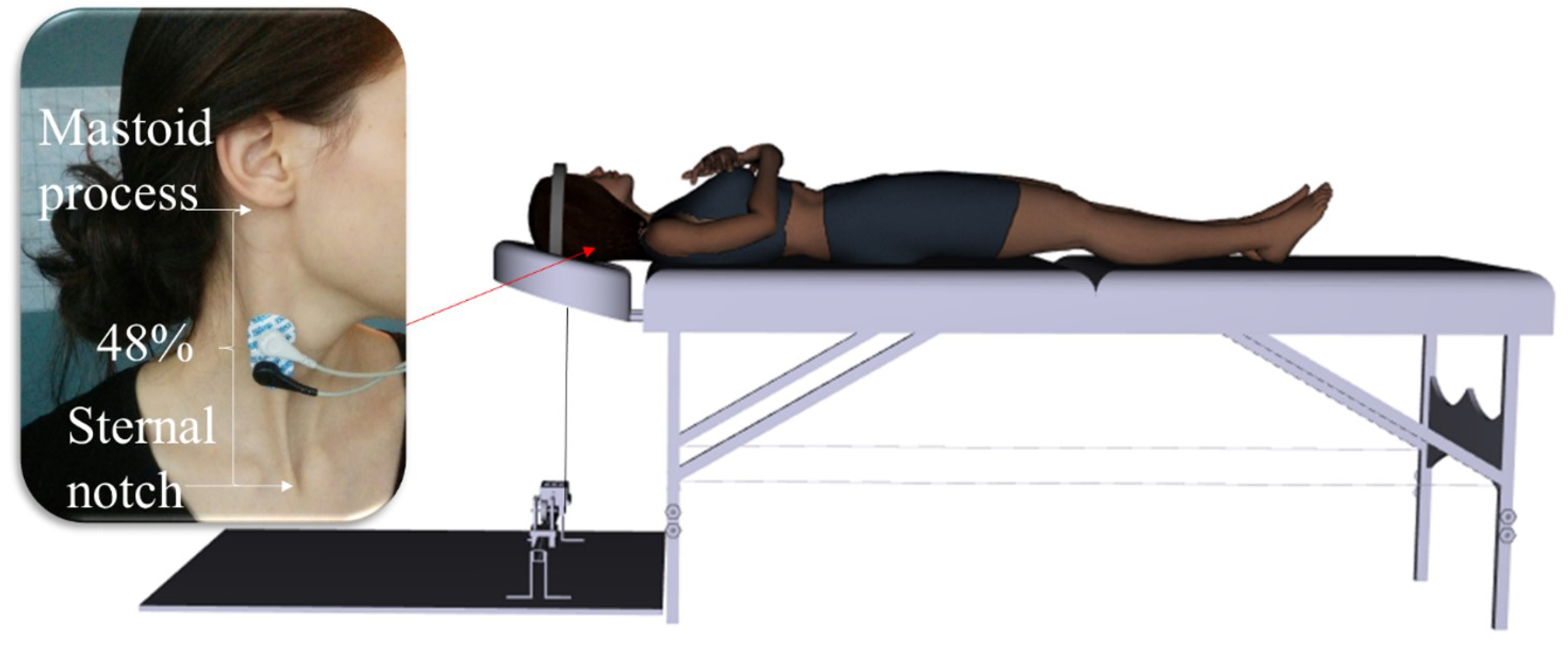

Participants performed resisted supine neck flexions. A Velcro head strap was secured to the participant’s head (sitting above their ears), and the back of the head strap was connected to the platform-mounted force transducer (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Experimental set-up for SCM muscle MVC. MVC, maximum voluntary contraction. (Created using Santos Pro software (V.1.5 2017, SantosHuman, Inc., Coralville, Iowa, USA)).

2.3.3.2 Upper Trapezius

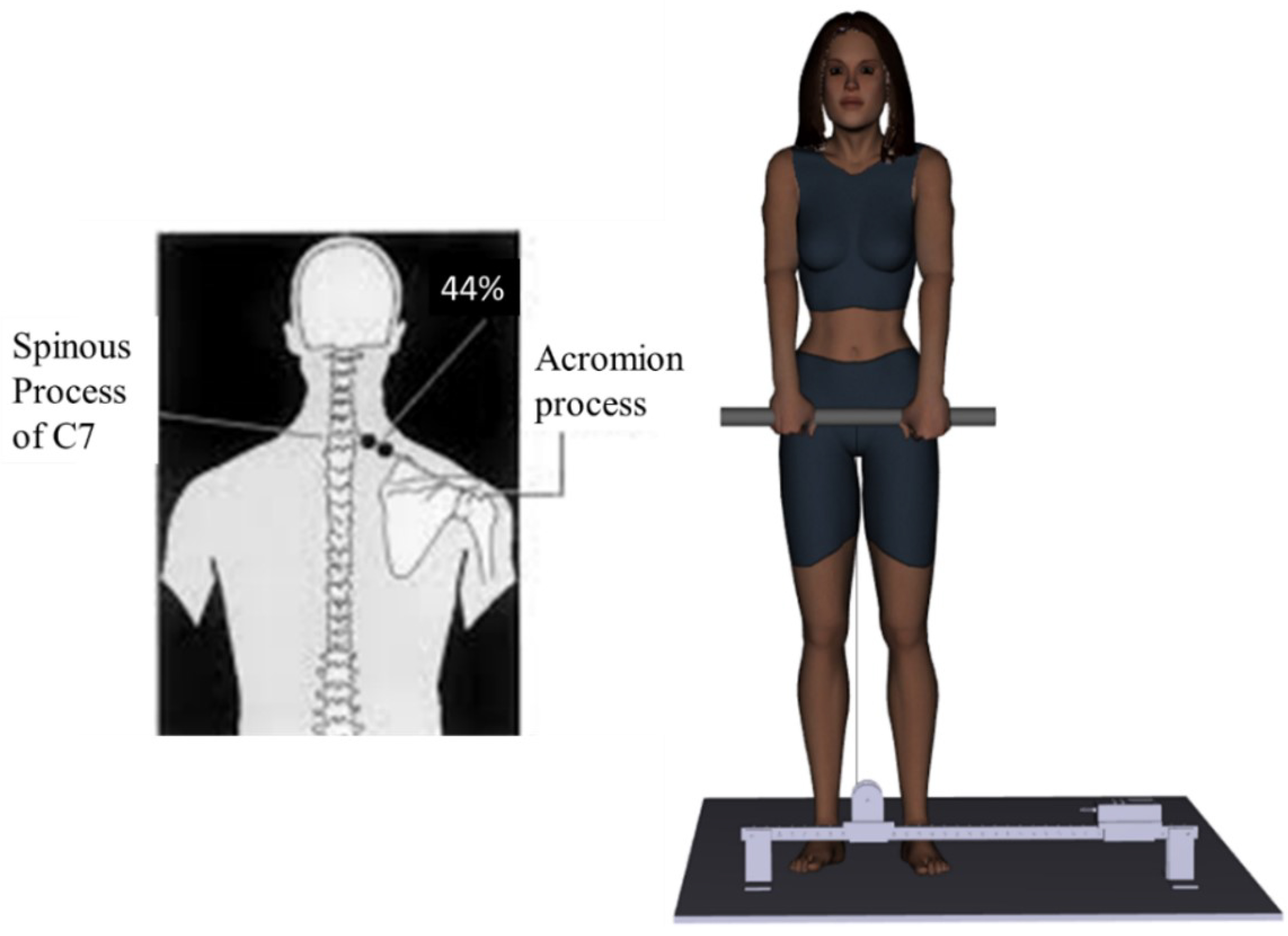

Participants performed resisted scapular elevations while they stood on a wooden platform with their feet shoulder-width apart and held onto a height-adjustable steel bar with an overhand grip (See Fig. 3). The steel bar was hooked to the force transducer.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Experimental set-up for upper trapezius muscle MVC. (Created using Santos Pro software).

2.3.3.3 Quadriceps

Participants performed resisted leg extensions while they were seated with their feet on the ground, back against the chair and arms by their sides. An ankle strap was secured to the leg of interest with the back of the strap connected to the force transducer.

2.3.3.4 Hand Grip

Participants stood in anatomical position while they used an overhand grip to squeeze a hand dynamometer (Model: Grip Force Transducer MLT004, AD Instruments, Sydney, Australia) with the arm being tested.

2.3.3.5 EMG Set-up for Neck Musculature

In order to record EMG of the upper trapezius and SCM during the MVC, a pair of tear-drop shaped, conductive adhesive hydrogel, AgCl surface EMG electrodes (MeditraceTM 130, Cardinal Health, Gananoque, ON, Canada) were placed bilaterally over the muscle belly in line with the fibers, for the muscle of interest. The skin was shaved, abraded and cleaned with an isopropyl alcohol swab, prior to electrode placement. A pair of EMG electrodes were placed bilaterally at 48% of the distance between the center of the sternal notch to the center of the inferior point of the mastoid process, for the SCM muscle [54]. The set of EMG electrodes were placed bilaterally at the level of the C7 spinous process, and at 44% of the distance between the C7 spinous processes and the acromion, for the upper trapezius muscle [54]. An inter-electrode distance of 1 cm was kept. The ground electrode was placed on the left clavicle.

All EMG signals were differentially amplified (bi-polar differential amplifier, input impedance = 100 M

A 0.25 second moving average window was applied to the force signal in LabChart 8 Pro before measuring peak force output over the three-second MVC. The average peak force output of two MVCs were used in statistical analysis.

Neuromuscular efficiency (NME) of the upper trapezius and SCM was calculated as the ratio between average peak force and the average RMS, measured in N/µV [13, 55]. NME offers insight into neural drive by measuring the amount of EMG activity needed to generate a specific force [55, 56].

There were 22 complete datasets for all outcome measures except for shoulder ROM. One shoulder ROM dataset was not included as the participant was in too much pain to do a baseline measure.

Twenty-one shoulder ROM datasets, and 22 datasets of remaining outcome measures were included in the statistical analysis. Normality was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk’s test, and square root transformations were applied for datasets that violated normality and/or were skewed. Sphericity was assessed using Mauchly’s test of sphericity. Greenhouse Geisser corrections were reported for data that violated sphericity.

Separate 3 (time)

A paired t-test was performed on the DASH scores.

To control for variability between baseline measures, percent change from baseline was conducted for RMS of the SCM, MPF and MDF of the upper trapezius. A 2 by 2 repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. The following equation was used to calculate percent change:

Statistical significance was set at p = 0.05. Partial eta squared values (

Twenty-two participants out of 24 completed the study by attending all three data collection sessions. One participant withdrew as they acquired a concussion mid-study, and another was unable to attend all treatment sessions. The demographic of the sample is provided in Table 1, and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 2.

| Demographic | Sample |

|---|---|

| Female:Male | 15:7 |

| Age (y) | 42.50 |

| Onset of clinical characteristics (y) | 7.61 |

| Average number of treatments | 11.00 |

| Average treatment frequency (number of weeks) | 5.50 |

| Clinical characteristics | Number of participants | |

| C0-C1 joint dysfunction | ||

| Bilateral | 19 | |

| Unilateral | 3 | |

| Region of pain | ||

| Neck | 12 | |

| Shoulder | 6 | |

| Arm | 3 | |

| Elbows | 0 | |

| Upper back | 0 | |

| Mid-back | 2 | |

| Low back | 12 | |

| Hip | 2 | |

| Leg | 1 | |

| Knee | 4 | |

| Ankle | 1 | |

| Heel | 1 | |

| Feet | 1 | |

| Frozen shoulder | 1 | |

| Headaches | 2 | |

| Pain exacerbated with poor posture, work/exercise | 2 | |

| Referred/radiating pain | 3 | |

| Muscle tightness | 4 | |

| Numbness of extremities | 1 | |

| Feeling off/imbalanced | 2 | |

| Easily fatigued | 1 | |

| Lack of sleep | 2 | |

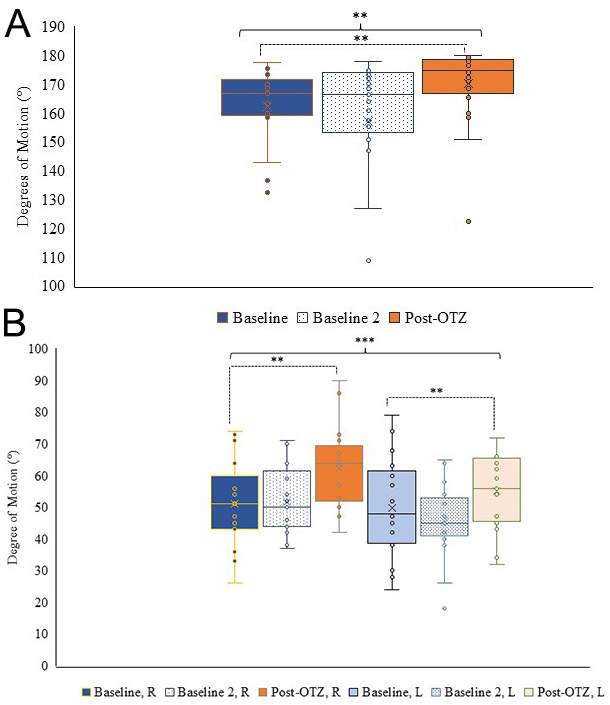

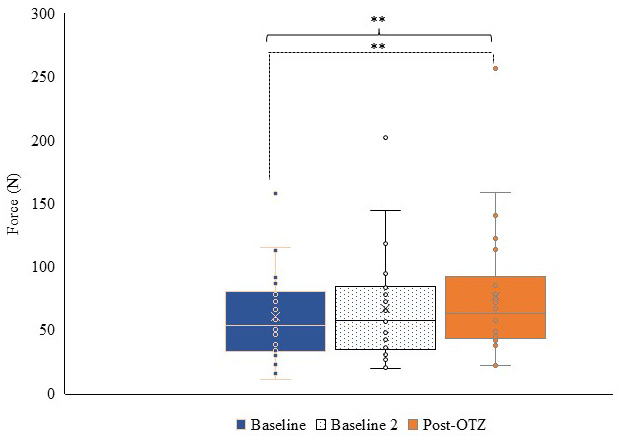

Shoulder abduction showed a main effect of time (F(1.503,30.053) = 7.737, p = 0.004,

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Shoulder range of motion. (A) Box and whisker plot for shoulder abduction ROM at the three time points. (B) Box and whisker plot for shoulder extension ROM per side and time point. Blue represents baseline, dotted represents baseline 2, and orange represents post-OTZ. The whiskers reflect minimum and maximum values. The boxes reflect the quartiles, and x symbol represents median. Dashed bars and asterisk(s) indicate a significant contrast. **p

Shoulder flexion showed no main effect of time (F(1.322,40) = 2.033, p = 0.162,

| Baseline | Baseline 2 | Post-OTZ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoulder flexion (°) | ||||

| Right | 163.00 | 163.14 | 167.76 | |

| Left | 164.90 | 158.67 | 168.71 | |

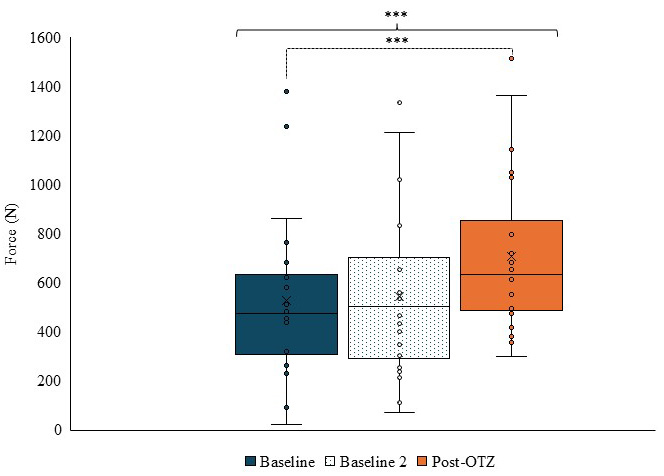

Peak force of the SCM showed a main effect of time (F(1.378,28.941) = 7.298, p = 0.006,

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Box and whisker plot for force output of the SCM at each time point. Blue represents baseline, dotted represents baseline 2, and orange represents post-OTZ. The whiskers reflect minimum and maximum values. The boxes reflect the quartiles, and x symbol represents median. Dashed bars and asterisk(s) indicate a significant contrast. ** p

| SCM | Baseline | Baseline 2 | Post-OTZ | |

| RMS (mV) | ||||

| Right | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.17 | |

| Left | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.18 | |

| NME (N/µV) | ||||

| Right | 0.40 | 0.35 | 1.50 | |

| Left | 0.55 | 0.98 | 0.93 | |

| MPF (mV) | ||||

| Right | 91.18 | 93.78 | 103.09 | |

| Left | 93.69 | 96.42 | 96.58 | |

| MDF (mV) | ||||

| Right | 76.08 | 82.58 | 85.94 | |

| Left | 77.76 | 79.85 | 82.24 | |

| Upper trapezius | Baseline | Baseline 2 | Post-OTZ | |

| RMS (mV) | ||||

| Right | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.30 | |

| Left | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.29 | |

| NME (N/µV) | ||||

| Right | 4.86 | 3.85 | 7.91 | |

| Left | 2.71 | 2.76 | 4.28 | |

| MPF (mV) | ||||

| Right | 68.26 | 74.11 | 76.70 | |

| Left | 64.36 | 68.90 | 73.66 | |

| MDF (mV) | ||||

| Right | 59.89 | 64.47 | 65.23 | |

| Left | 58.12 | 63.09 | 66.82 | |

EMG, electromyographic; RMS, root mean square; NME, neuromuscular efficiency; MPF, mean power frequency; MDF, median power frequency.

Peak force of the upper trapezius showed a main effect of time (F(2,42) = 12.341, p

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Box and whisker plot for force output of the upper trapezius at each time point. Blue represents baseline, dotted represents baseline 2, and orange represents post-OTZ. The whiskers reflect minimum and maximum values. The boxes reflect the quartiles, and x symbol represents median. Dashed bars and asterisk(s) indicate a significant contrast. *** p

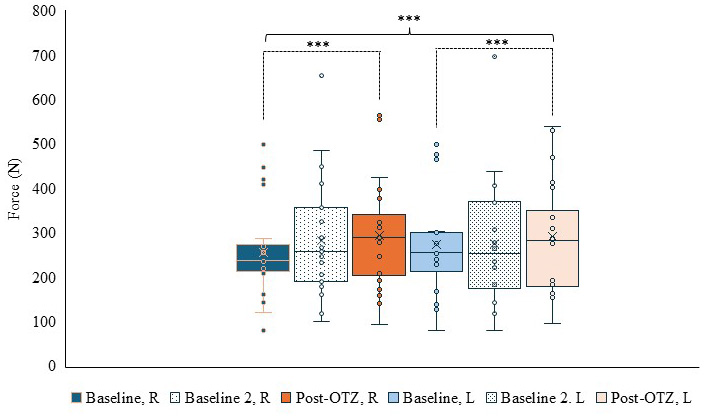

Peak force of quadriceps had an overall time by side interaction (F(1.443,30.310) = 4.448, p = 0.031,

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Box and whisker plot for force output of the quadriceps per side and time. Blue represents baseline, dotted represents baseline 2, and orange represents post-OTZ. The whiskers reflect minimum and maximum values. The boxes reflect the quartiles, and x symbol represents median. Dashed bars and asterisk(s) indicate a significant contrast. *** p

| Baseline | Baseline 2 | Post-OTZ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right grip (N) | 287.92 | 284.82 | 305.08 |

| Left grip (N) | 281.71 | 272.34 | 289.95 |

There was a statistically significant decrease from baseline (22.41

This longitudinal study revealed that in the absence of treatment there are continued impairments in shoulder ROM, EMG measures for the SCM and upper trapezius, force production of the upper trapezius, and grip strength. The peak force production of the SCM, and quadricep were slightly higher than baseline, but not significantly, indicating that repeating the movement 2 to 5 days later in of itself does not result in significant improvements in force production. In response to the pragmatic treatment, using the OTZ system, there were improvements in shoulder abduction and extension, peak force output of the SCM, upper trapezius and quadriceps, reflected by an effect of time in the post-OTZ to baseline contrast. The DASH also improved following treatment, which achieved both minimum clinically important difference and minimum detectable change. Shoulder flexion and the EMG measures (RMS, MPF and MDF) of the SCM and upper trapezius remained stable across the three time points, with no main effect of time. The NME of the SCM and upper trapezius increased in response to the OTZ system, but did not yield a main effect of time. These selective changes suggest that the OTZ system may be effective at improving impaired gross motor function before physiological measurements in a population with chronic musculoskeletal problems and C0-C1 joint dysfunction(s). The post treatment improvement also suggests that those with C0-C1 joint dysfunction had impaired motor control to begin with which was able to improve once joint dysfunction was addressed.

The decrease in self-reported upper limb pain and disability following the OTZ system aligns with previous studies that treated upper limb functional disabilities or disorders using non-spinal manipulation interventions [43, 45]. These findings suggest that the OTZ system effectively improves upper-extremity function in individuals with C0-C1 joint dysfunction and chronic musculoskeletal problems, achieving both the minimum clinically important difference, and the minimum detectable change.

The increase in shoulder abduction coincides with a retrospective case series in which HVLA adjustments were applied the C0-C1 and thoracic spine in individuals with C0-C1 joint dysfunction and frozen shoulder syndrome [25]. While the present focused on individuals with C0-C1 joint dysfunction and chronic musculoskeletal problems, the replicated findings suggest that the OTZ adjustment of the OTZ system may account for this improvement.

The increased shoulder extension ROM corresponds to literature that examined the immediate effects of cervicothoracic manipulation in those with shoulder pain [61] or shoulder impingement syndrome [62]. Though those studies examined a different clinical population with a focus on cervicothoracic adjustment, it suggests that addressing the C0-C1 prior to other spinal regions in the cephalocaudal direction influences biomechanics of scapular motion and humeral elevation.

The increase in SCM force production following C0-C1 treatment aligns with [30], who found that manipulation between C0-C7 versus C2-C7 lead to immediate improvements in anterolateral neck flexors (longus colli, rectus capitus anterior, rectus capitus lateralis, scalenes, platysma, and SCM), despite using a different MVC protocol than the present study. This suggests that addressing the C0-C1 joint dysfunction prior to other regions in the spine could impact gross motor function of the neck musculature.

The increased force production in the upper trapezius and quadriceps aligns with studies that have examined the influence of spinal manipulation on neuronal excitability in the upper limb [63] and treatment of dysfunctional sacroiliac joints [36], and neuronal excitability in the lower limb [35, 63]. There is insufficient literature discussing how the manipulation of the upper cervical spine directly influences force production of the upper trapezius and quadriceps. However, there is literature that suggests that manipulation of dysfunctional spinal segments in individuals with recurrent spinal pain yield improved central processing [64, 65], which is known to influence mechanisms (e.g., corticospinal excitability, feedback loops, etc.) underlying force production. Despite the lack of literature, it is possible that addressing C0-C1 dysfunction in conjunction with other spinal joint dysfunctions in those with C0-C1 and chronic musculoskeletal problems improved gross motor output of the upper trapezius and quadriceps.

The improvements in gross motor function of the shoulder (abduction and extension), SCM, trapezius, and quadriceps suggest that treating C0-C1 joint dysfunction(s) in addition to other spinal regions may account for these changes, as it was the only common adjustment among all participants.

As Murphy et al. [25] suggested, OTZ adjustments restored C0-C1 functionality. This could have influenced the musculature (SCM and upper trapezius) innervated by the nerve that pass through the complex, i.e., cranial nerve 11 (spinal accessory nerve) [66]. This restoration may contribute to the increase shoulder abduction (beyond 90°), and force production of the SCM, and upper trapezius.

The increase in all selective outcomes including the shoulder extension and force production of the quadriceps may be in response to restored normal afferent input to the central nervous system [3] following the restoration of normal biomechanics of paraspinal musculature within the spine via the OTZ system. Afferent feedback from the ventral rami of C2 to C4 via the upper trapezius and SCM [67, 68] contributes to feedback loops involved in force production and motor control. This is because spatial awareness, derived information from sensory feedback, plays a role in motor control including force production, as an accurate internal representation is necessary for motor neurons to work in unison to produce movements [69]. With enhanced central processing of somatosensory information, it is plausible there was increased cortical spinal drive/motor neuron excitability via central corticomotor facilitatory and inhibitory neural processing or reduced local inhibitory activity [3, 35, 63] through the reflex neural outputs on the musculature of the neck and limb following the intervention. These processes could attribute to the observed improvements in the DASH outcome measure. There is not currently a direct mechanism to explain the improvement in quadriceps strength relative to C0-C1, however it may represent generalized inhibition in response to chronic spinal dysfunction and pain. It has been suggested that there may be “whole body inhibition” in response to chronic pain as well as connections via fascial networks by which chronic upper cervical dysfunction might influence lower limb function [70]. Niazi et al. [35] showed increased cortical drive to a lower limb muscle in response to spinal manipulation that included multiple body regions including the neck, providing evidence that these connections are complex. Alternately, the improved strength may be related to the treatment of other spinal regions. There is a need for future studies to better understand the mechanism of the increased quadriceps strength.

It is important to note that this feasibility study used a repeated measures design where each participant acted as their own control via a double baseline measure. While this controlled for learning effects and measurement variability, it was not a placebo. As such, we cannot rule out that some of the improvements in subjective measures were related to placebo effects. Additionally, while the inclusion criteria was the presence of C0-C1 joint dysfunction which has be resolved, pain also improved, therefore it is possible that the decrease in pain, rather than the specific correction of the joint dysfunction was responsible for the observed improvements.

One limitation was the absence of a control group that either received no treatment or was treated for spinal joint dysfunctions other than C0-C1. A double baseline, where outcome measures showed no statistical differences, along with improvements following the OTZ system, suggests that this intervention contributed to selective improvements in neck and limb motor control. This claim cannot be made with certainty since causality is better assessed with a randomized control trial design. Due to the repeated measures design, blinding was not possible as participants would know they were wait-listed and then treated. As there was no past data on this topic, a large effect size was used. This opens the possibility of a type II error for some measures. Participants were recruited from a single practice. This was done because the practitioner had advanced training in the OTZ technique and a large number of patients with C0-C1 dysfunction were referred to that practice. While this aided recruitment, it opens the possibility of selection bias. As this was a feasibility study, p-values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. Instead, partial eta squared values were calculated to provide effect size data which could also be used in power calculations for future randomized control trials.

There is a lot of variability with the data extraction at baseline 2 and post-treatment; however, the lack of changes and changes observed indicate that the impact of this variability is negligible. In addition to the improvement criterion of 80%, it would’ve been beneficial to administer a global rate of change, to capture the participant’s self-reported response to treatment [71]. We incorporated the 80% improvement criteria as a way to standardize the measurement end point given the diversity of presenting symptom. It is possible that this 80% improvement may have introduced subjective variance. It is worth noting that participants were not informed that the 80% improvement would determine the time point for the outcome measures, which would have decreased some of this subjective variance.

It should be noted that all participants were recruited from a single clinic in Toronto which limits the ability to generalize the findings to broader populations and different clinic settings. As this was a pragmatic trial forty-five percent of the sample (10/22) received adjunct care such as massage therapy and the OTZ approach also includes treatment of other dysfunctional spinal regions once the C0-C1 dysfunction has been addressed. However, all participants presented with C0-C1 joint dysfunction and this responded to the OTZ intervention, while the involvement of other areas was variable between participants. Therefore, while the observed changes are likely due to the OTZ system, it may not be solely attributed to the C0-C1 effects. This should be considered when interpreting the findings.

It is also important to note that the detection of C0-C1 dysfunction using the OTZ technique has not undergone a specific reliability study, and the specificity of the HVLA thrust to the C0-C1 segment has not been measured, therefore while the treatment effects are clear, we cannot with certainty attribute these effects to C0-C1 dysfunction and its normalization via spinal manipulation.

The effect sizes from this study can be used to determine the required sample size for future research, such as longitudinal studies or randomized controlled trials. Future studies should address the limitations identified in this research, to confirm the effectiveness of the OTZ system. Further research could explore whether individuals with C0-C1 joint dysfunction and accompanying spinal joint issues exhibit disordered cortical, cerebellar, and central processing using neurophysiological techniques.

This pragmatic longitudinal observational study demonstrated persistent impairments in force production and range of motion in the absence of treatment, while the OTZ system intervention led to selective improvements in neck and limb force production and range of motion in those with C0-C1 joint dysfunction and musculoskeletal pain. Improvements were seen in shoulder ROM (abduction and extension), and force production of the SCM, upper trapezius and quadriceps. The lack of changes between the two baselines suggest that spinal dysfunction (C0-C1 and other regions of the spine) leads to impairments in neck and limb motor control. In contrast, the OTZ treatment improved force production and range of motion, likely due to improved central processing following normalization of afferent input from the upper cervical spine in those with C0-C1 joint dysfunction. This work suggests that the C0-C1 joint plays an important role in sensorimotor control. It also suggests that its assessment and treatment may be worth exploring in individuals with neck and upper limb sensorimotor deficits, however, this needs to be verified with a randomized control trial design in future research.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

UA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RW: Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. HH: Conceptualization, Writing – reviewing and editing. BM: Conceptualization, Validation, Resources, Writing – reviewing and editing, Supervision, funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ontario Tech University (File #: 4817), and all of the participants provided signed informed consent.

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Francis Murphy, Dr. Michael Hall and Mitacs Canada, as well as the efforts of Dr. Patricia McCord for treating the individuals that participated in this study.

This work was funded by Dr. Francis Murphy, Dr. Michael Hall and Mitacs Canada.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. None of the funders, including the founder of the OTZ system (Francis Murphy), were involved in any aspect of the research process itself. Bernadette A. Murphy is serving as one of the Editorial Board members of this journal. We declare that Bernadette A. Murphy had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Bettina Platt.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/JIN39548.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.