1 College of Electronic and Information Engineering, Hebei University, 071002 Baoding, Hebei, China

2 Key Laboratory of Digital Medical Engineering of Hebei Province, 071002 Baoding, Hebei, China

3 Academy of Medical Engineering and Translational Medicine, Tianjin University, 300072 Tianjin, China

4 The Medical Department of Neurology, Affiliated hospital of Hebei University, 070000 Baoding, Hebei, China

5 Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning, Division of Psychology, Beijing Normal University, 100875 Beijing, China

6 Department of Psychology, University of Macau, 999078 Macau, China

Abstract

Anatomical studies have indicated that the brain and the heart are connected through multiple pathways. However, the functional interplay between them is unclear, especially for different task states. This study explored the brain-heart interplay under reflexive and voluntary saccade tasks.

The Synthetic Data Generation model was used to quantify the interplay between the brain and heart.

Bidirectional interplay patterns were found between the brain and heart under different frequency bands for the two types of saccade task. There were significant variations in the interplay coupling across saccade tasks, particularly in the prefrontal and parietal lobes. This phenomenon can be explained by the complexity and cognition load among the saccade tasks.

This study shed light on the dynamic bidirectional interplay mechanisms between the brain and heart, contributing to the understanding of brain-heart interaction.

Keywords

- brain-heart interplay

- interplay mechanism

- inter heartbeat interval

- electroencephalograph

- saccade

- cognition

The central nervous system (CNS), comprising the brain and spinal cord, is the center for all neural activities in the body. It is responsible for processing and integrating sensory information from the sensory organs and coordinating appropriate responses. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) composes sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves and regulates the activity of internal organs, including heart, stomach, intestine, blood vessel and glands. Brain-Heart Interaction (BHI) refers to the dynamic interplay mechanism between the CNS and ANS, which involves how the brain influences heart function and how the heart affects brain. For instance, patients with heart disease often experience cognitive impairments, such as attention deficits and memory loss, while individuals with mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression, frequently exhibit abnormalities in the cardiovascular system [1]. This interplay mechanism relies on the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the ANS. The sympathetic nervous system increases heart rate and blood pressure during stress responses, while the parasympathetic nervous system promotes heart relaxation during calm states [2, 3]. Therefore, the brain regulates heart function through these pathways, and the heart’s state, in turn, influences brain function.

Heart rate is a significant indicator of autonomic heart function, reflecting the interplay between the CNS and the ANS. Inter heartbeat interval (IHI) refers to the variation in the time intervals between heartbeats. IHI is stable in a healthy state and may change in different states such as exercise, stress, and illness, and the degree of change in IHI depends on individual differences, severity of illness, and the specifics of the state [4]. In frequency domain analysis, IHI is typically divided into high-frequency (HF, 0.15–0.4 Hz) and low-frequency (LF, 0.04–0.15 Hz) components. The HF component primarily reflects parasympathetic activity, while the LF component represents a combination of sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation [5]. IHI is not only considered as a biomarker of heart function but also potentially reflects the brain’s adaptive interplay capacity [6]. Studies have shown that HF IHI is associated with better emotional interplay [7, 8] and improved performance in cognitive tasks such as working memory [9]. Conversely, LF IHI is linked to emotional disorders such as depression and anxiety [10]. CNS can also regulate the activity of the ANS through various cortical areas. Functional neuroimaging and near-infrared spectroscopy studies have shown that the anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal cortex are associated with stress-induced sympathetic nervous activity changes [11, 12]. Additionally, in lower body negative pressure experiments requiring decision-making tasks, significant sympathetic skin responses were correlated with activity in the extrastriate visual cortex and parietal lobe. This suggests that the central posterior regions are involved in the control of peripheral autonomic functions [13, 14].

Changes in brain-heart interplay can reflect the dynamic regulatory relationship between the brain and the heart, which may contribute the diagnosis of cardiac and brain diseases for a more precise one through dig different patterns during the performance of different tasks [15, 16]. For example, factors such as task load, emotional state, or external stimuli may affect the brain regulation of the heart, and conversely, the state of the heart may affect brain function through the autonomic nervous system [17, 18]. Therefore, further exploration of brain-heart interplay in different task contexts can help deepen our understanding of brain-heart interplay and provide new perspectives on task-driven neurophysiological regulation. This will provide important information for early diagnosis, treatment, and amelioration of physiological changes triggered by coupled brain-heart interactions and support more precise clinical intervention strategies. For example, changes in BHI in cardiovascular diseases reflect abnormalities in heart autonomic interplay, particularly in patients with arrhythmias [19]. This finding underscores that alterations in BHI may serve as an early indicator of heart disease and could be a key factor in the pathological development of such conditions. Another study has shown that during resting state and Go/No-Go tasks, changes in heart have been significantly linked to the brain’s cognitive control regions [20]. In working memory tasks, IHI has been closely associated with neural activity in patients with depression or anxiety while performing executive function tasks [21]. Additionally, cold pressor experiments have revealed that strong external stimuli not only activate the sympathetic nervous system, leading to rapid changes in heart rate and blood pressure, but also have profound effects on brain through complex neural pathways [22]. The aforementioned research advances have mainly relied on various analytical methods, including linear and nonlinear indices, time-frequency domain analyses [23, 24, 25], as well as recently developed model-based approaches such as Granger causality [26], transfer entropy [27], and Synthetic Data Generation (SDG) models. A recent comprehensive review [28], has systematically evaluated these techniques and highlighted their respective advantages and limitations in measuring dynamic brain–heart interplay. However, there remains a lack of consensus on the most effective technique for analyzing BHI, particularly under task-evoked conditions. In this study, we adopted the SDG model due to its ability to capture directed interactions with high temporal precision and distinguish between brain-to-heart and heart-to-brain couplings.

Saccade as a behavioral assessment tool, not only provides an accurate evaluation of cognitive and memory functions [29], but also effectively reflects the interplay processes of the ANS on the heart LF and HF [30]. Additionally, saccade behavior is influenced by the CNS [31], making saccade tasks as a unique tool for capturing the interplay relationship between the CNS and ANS. This provides a distinct advantage when analyzing BHI.

In summary, this study aims to investigate BHI across different saccade task paradigms by employing the SDG model. By examining bidirectional coupling dynamics, we aim to reveal how distinct saccade conditions modulate autonomic regulation and cortical activity. This research contributes to a more refined understanding of task-specific BHI and supports future clinical and translational applications.

In this study, two types of saccade task were used: the reflexive saccade task and voluntary saccade task. The reflexive saccade task contains Pro Saccade task (PS), and the voluntary saccade task contains Anti Saccade task (AS) and the Memory Guided Saccade task (MGS).

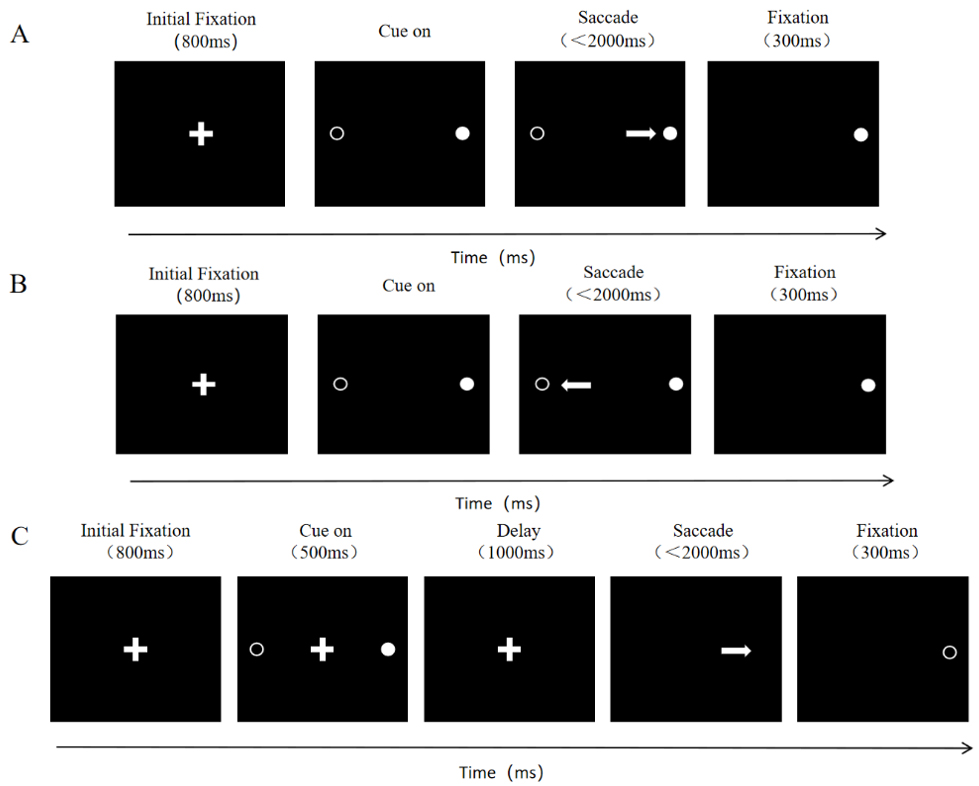

The driving factor for the PS task is primary exogenous, requiring no complex cognitive processes to be involved [32]. Specifically, in the PS task, a white cross appears at the center of the screen, and the participant must immediately fixate on the cross. When the cross disappears, a white dot randomly appears to the left or right of the fixation point. The participant must quickly and accurately direct their gaze towards the location of the white dot. The schematic of PS is shown in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of saccade tasks. The center shows the white cross. The solid white circle represents the location where the white dot appeared, while the hollow white circle indicates the possible locations where the white dot could appear. The white arrow represents the required saccade trajectory for the task. (A) Schematic of the Pro Saccade Task. (B) Schematic of the Anti Saccade Task. (C) Schematic of the Memory Guided Saccade Task.

Unlike the PS task, both the AS and MGS tasks are typically driven primarily by endogenous factors, involving the participation of higher cortical areas [33]. The AS task requires participants to suppress their automatic response to exogenous stimuli, thus effectively controlling their attention [34]. The MGS task, on the other hand, focuses on examining the memory function of participants [35].

In the AS task, the sequence of the white cross and white dot appearing on the screen is the same as in the PS task, but the participant must look at the opposite, mirrored location of the white dot after it appears (shown as Fig. 1B).

In the MGS task, when the white cross appears at the center of the screen, the participant must focus on the cross. During this fixation, a white dot randomly appears and disappears on the left or right side of the screen. The participant is asked to maintain focus on the central cross and remember the location of the appeared white dot. Once the cross disappears, the participant must immediately look at the location where the white dot appeared (shown as Fig. 1C).

A total of 30 young volunteers were recruited under three saccade tasks, during

which both electroencephalogram (EEG), electrocardiogram (ECG) and eye movement

signals were recorded simultaneously. Prior to the experiment, each participant

was required to thoroughly clean their scalp with shampoo to remove any oils or

residues. After this, the EEG cap (32-channel Quik-Cap Neo Net, Neuroscan, Compumedics Limited., Abbotsford, Victoria, Australia) was fitted, and conductive gel was applied to

ensure that the impedance at each electrode site was below 10 k

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hebei University Affiliated Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who also confirmed that they had no history of neurological, cardiovascular, or other related diseases.

Before the official experiment began, participants read the experimental instructions and completed practice trials. Only after confirming their clear understanding of the instructions did the formal experiment commence. The task of the formal experiment was performed in different sessions, each consisting of 60 trials, 30 left and 30 right, with the order of appearance of the trials being randomized. Each session consisted of only one eye-tracking task. Before the start of each task, subjects were required to stare at nine visual stimulus points that appeared sequentially at different locations on the screen to complete the calibration and validation. Subjects were allowed to perform the task only when the error in eye position was less than that allowed by the validation; otherwise, they were required to perform the calibration and validation again. At the end of each session, subjects were required to take a 5-minute rest with their eyes closed before proceeding to the next session.

EEG data preprocessing was conducted using the EEGLAB toolbox (EEGLAB 2022.1, the Swartz Center for Computational Neuroscience (SCCN) at the University of California, San Diego, CA, USA, https://sccn.ucsd.edu/eeglab/index.php) and FieldTrip toolbox (FieldTrip toolbox 20240701, the Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, Radboud University, Nijmegen, https://www.fieldtriptoolbox.org) in MATLAB. The preprocessing of EEG data involved the following steps:

(1) Channel Rejection: Bad channels were removed by inspecting the log power spectral density plot of all channels generated by EEGLAB.

(2) Filtering: A bandpass filter from 0.5 to 45 Hz was applied using the built-in finite impulse response (FIR) filter in EEGLAB.

(3) Re-referencing: The re-reference method used was the average of all electrodes across the brain [36].

(4) Artifact Removal: Independent Component Analysis (ICA), a function provided by EEGLAB, was used to remove non-brain-related components.

For power spectral analysis, we applied Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) with

a Hanning window. A sliding window of 2 seconds (corresponding to 2

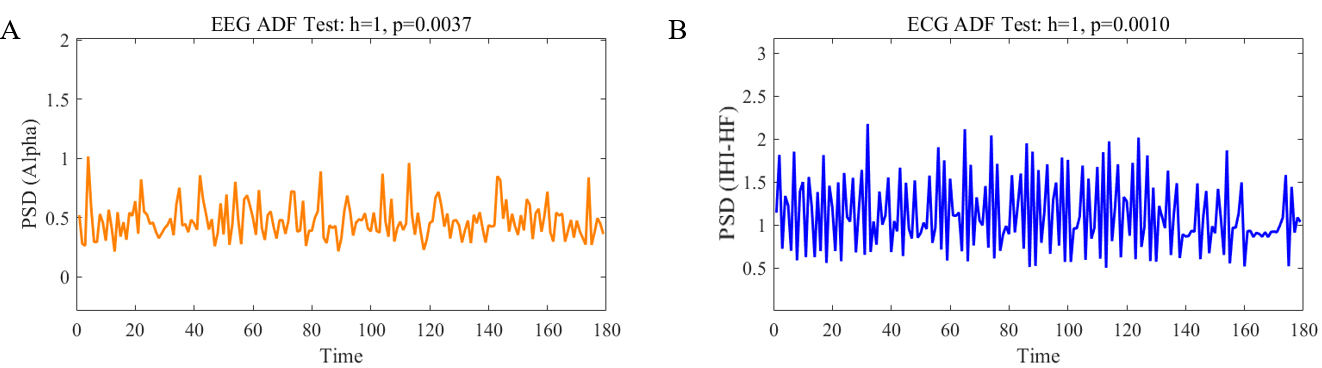

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test results. (A) refers to the ADF test of the power spectral density (PSD) time series in the electroencephalogram (EEG) Alpha band for a given subject (h = 1, p = 0.0037), while (B) refers to the ADF test of the PSD time series in the electrocardiogram (ECG) Inter heartbeat interval high-frequency (IHI-HF) band for the same subject (h = 1, p = 0.001).

The ECG time series were band-pass filtered between 0.5 and 45 Hz. A peak detection algorithm was used to identify the R-peaks of the ECG signal [36]. The detected R-peaks were visually inspected to identify any potential errors, which were then corrected accordingly. After detecting the heartbeats, we constructed the IHI sequence. To enable spectral analysis, the IHI sequence was uniformly resampled using spline interpolation to achieve a sampling rate of 4 Hz [37], corresponding to a temporal resolution of 0.25 seconds. This resampling facilitates time-frequency analysis. We then applied STFT with a Hanning window of 2 seconds (8 samples at 4 Hz) and 50% overlap. To verify the stationarity of the IHI signal within each 2-second window, we visually inspected the time series and spectrograms for abrupt shifts or drifts. Segments that clearly deviated from stationarity were excluded from analysis. For spectral decomposition of the ECG, the FFT length was set to 256 [38], which was selected to provide sufficient frequency resolution for observing LF (0.04–0.15 Hz) and HF (0.15–0.4 Hz) components. Furthermore, we evaluated the stationarity of the resulting ECG PSD time series, which serve as inputs to the model using the ADF test (Fig. 2B).

The SDG model evaluates the mutual interplay between brain and IHI dynamics across specific frequency bands (below alpha band (0.5–12 Hz), beta band (12–30 Hz), and gamma band (30–45 Hz)) in both low and high-frequency ranges [39].

To address the directional influence from the brain to heart activity, we

adopted the Integral Pulse Frequency Modulation (IPFM) model, which

conceptualizes heartbeat generation as a threshold-based integration process,

wherein heartbeats are emitted once an integrated signal reaches a preset

threshold. Specifically, this model was parameterized using the properties of the

Poincare diagram [40], where the heartbeat was considered as a collection of

impulse signals, and each impulse corresponds to a specific moment

In this equation,

Where

Here,

The angular frequencies

The interplay coefficient between the brain and the heart was calculated by the following equation:

Interplay from the heart to the brain was modeled by an adaptive Markov process to generate synthetic EEG sequences [41]. In this model, the upward interplay of the heart to the brain was realized through an autoregressive process and least squares. To be specific, this autoregressive process was designed to simulate how short-term HRV components in the LF and HF bands influence EEG power fluctuations across time. The model used the band and time window information of a specific EEG channel to integrate previous neural activity and current heartbeat dynamics to construct a Markovian neural activity sequence. In this process, the EEG signal EEG(t) can be expressed as a superposition of a series of frequency components with the following equation:

The estimation of

The heart to brain interplay coefficient was calculated by analyzing the effect of LF or HF on the generation of EEG data with the following equation:

The rationale behind this modeling approach is to infer the directional influence of ANS activity (reflected in LF and HF components) on cortical dynamics. By quantifying this influence through normalized coupling coefficients, we aimed to capture time-resolved regulatory patterns.

Interplay coefficients proposed by the SDG model were averaged for each subject

(N = 26) at the time points, both AS and MGS belong to the voluntary saccade

tasks, so we averaged the interplay coefficients of the two saccade tasks. To

reduce the effect of individual differences, the median was calculated between

all participants for each EEG channel, and Friedman’s test, followed by

Bonferroni correction (

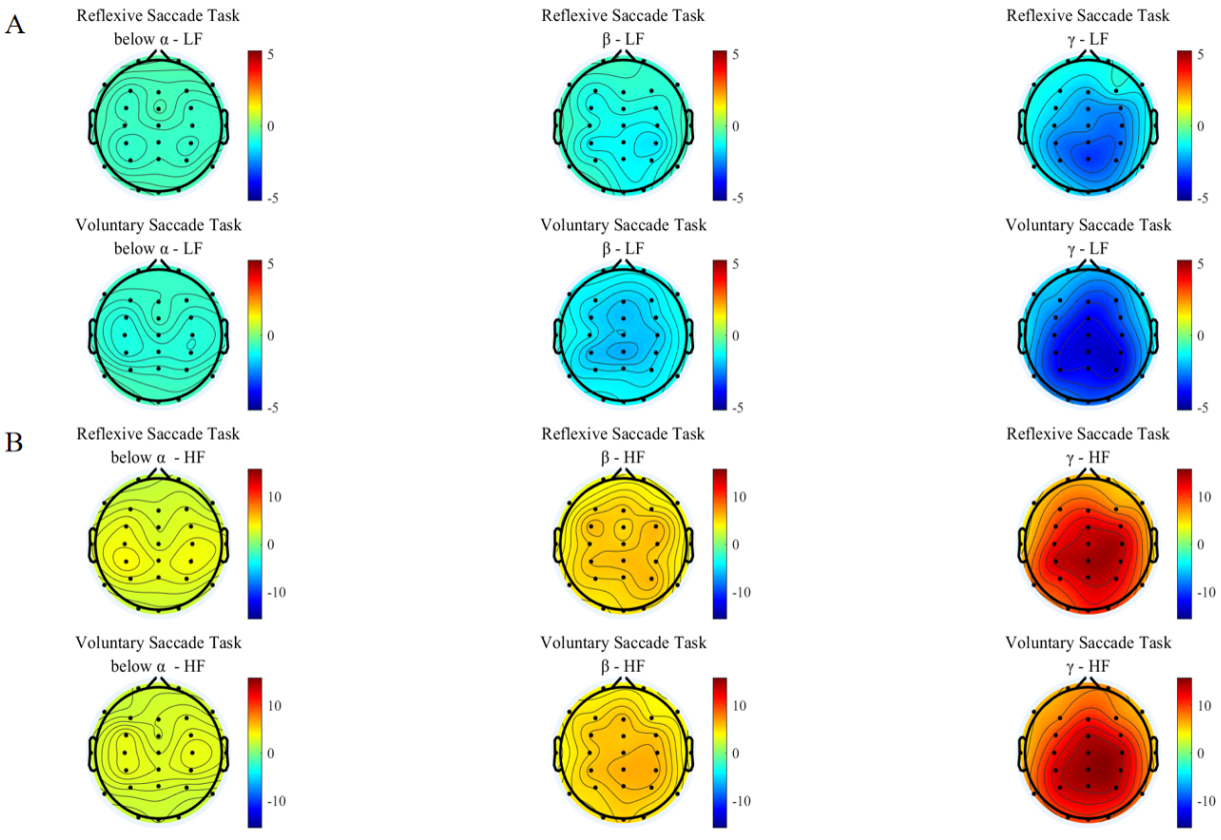

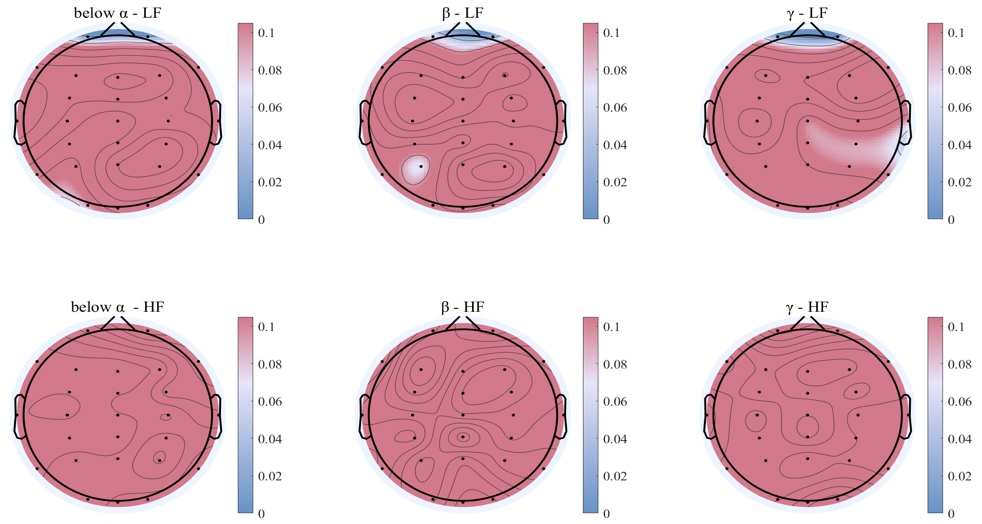

The interplay coefficients of brain to LF of heart under the two groups saccade tasks were shown in Fig. 3A. Only gamma band showed significant interplay coefficients in the two groups of saccade tasks, especially in the parietal region, whereas the interplay coefficients in other frequency bands (below alpha and beta) were not significant (Table 1). The values of the interplay coefficients from the brain to the LF of the heart were all negative. The negative interplay coefficients suggest that during the performance of the saccade tasks, the increase of brain activity led to a decrease in the LF of heart. This may stem from the cognitive load triggered by the demands of the task [42]. We observed that the absolute mean interplay coefficients across different frequency bands were higher for the voluntary saccade task compared to the reflexive saccade task. This difference may be attributed to the voluntary saccade task engaging higher cortical regions, thereby increasing cognitive load and resulting in stronger negative interplay relationships.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Brain to heart interplay coefficients. The first row is for reflexive saccade task, the second row is for voluntary saccade task. (A) Brain to low-frequency (LF) of heart interplay coefficients for participants performing two groups saccade tasks, and the subplots in each row represent the interplay coefficients from brain to LF of the heart in different frequency bands. (B) Brain to high-frequency (HF) of heart interplay coefficients for participants performing two groups saccade tasks, and the subplots in each row represent the interplay coefficients from brain to HF of the heart in different frequency bands.

| Task | BrainToLF (Mean) | BrainToHF (Mean) | ||||

| Below |

Below |

|||||

| Reflexive | –0.6755 | –1.2648 | –2.3954 | 3.0449 | 5.5381 | 10.8306 |

| Voluntary | –0.9126 | –1.6962 | –3.2995 | 3.0960 | 5.5451 | 10.5596 |

The pattern of brain to HF of the heart interplay was shown in Fig. 3B. As can be seen, the below alpha band of EEG demonstrated limited interplay with HF of the heart. However, the interplay coefficient rises as the frequency band increases (Table 1). The most pronounced interplay influence was observed in the gamma band within the parietal areas. All frequency bands showed positive interplay coefficients. The positive interplay coefficients suggested that the increased brain leads to increased heart HF during the performance of a saccade task [43]. No distinct pattern was observed in the brain average interplay coefficients across different frequency bands between the two groups of saccade tasks. This requirement may have driven the brain to regulate heart HF in a consistent manner across all tasks, thereby effectively mitigating excessive physiological stress [44].

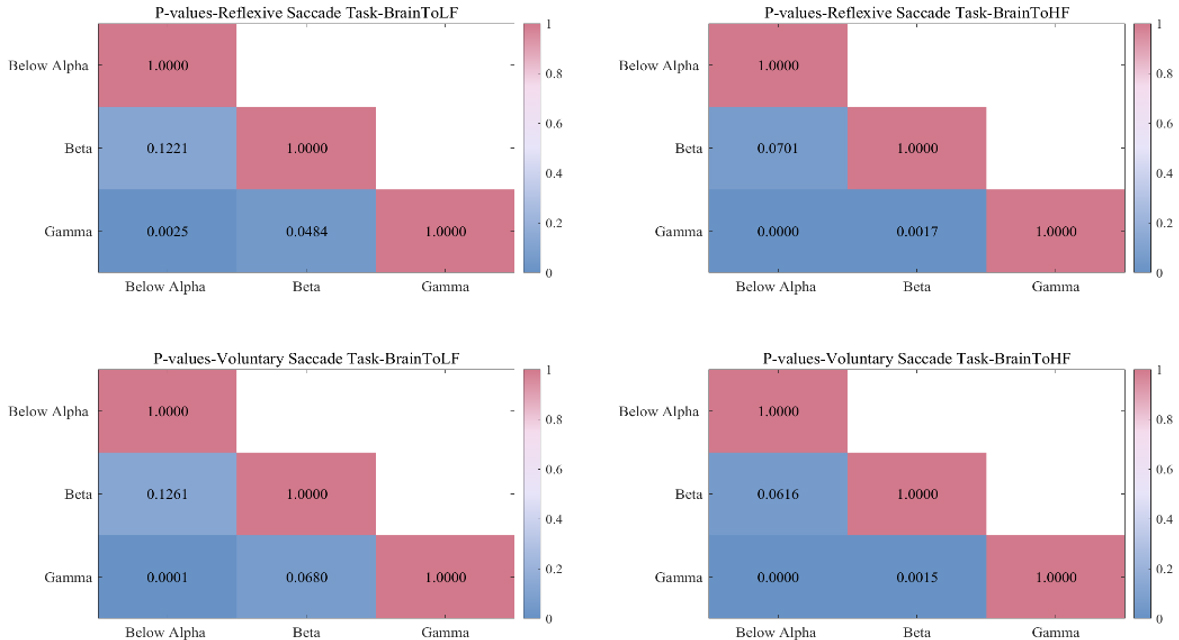

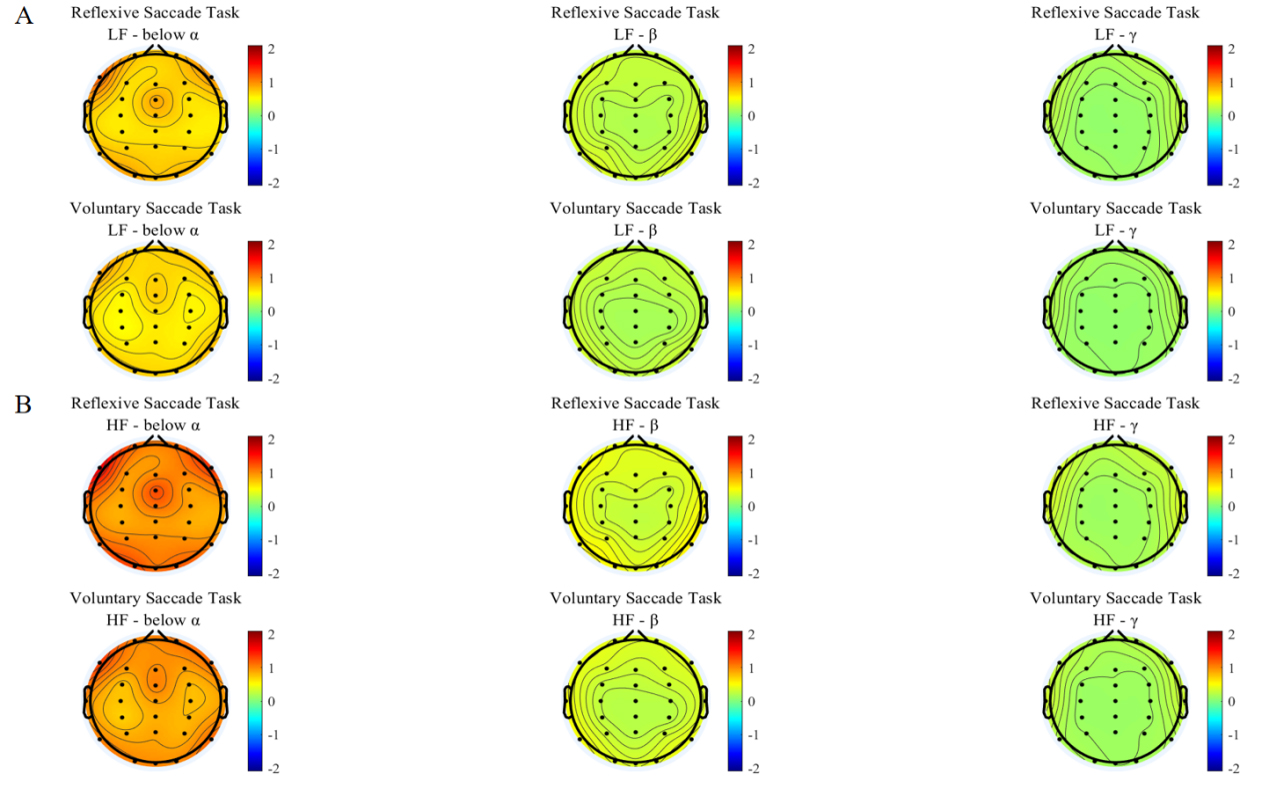

Average interplay coefficients from the different frequency bands of the brain to the LF and HF of the heart proved that the interplay coefficients of the gamma band were the strongest. To further prove this, we performed a p-value test on the interplay coefficients in different frequency bands for two groups of saccade tasks (shown in Fig. 4). p-values were obtained by Friedman’s test and Bonferroni correction. As can be seen from the figure, there are significant differences in the gamma band.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

p-values between different frequency bands for the two groups of saccade tasks. The first row is the reflexive saccade task, the second row is the voluntary saccade task. The first column is the interplay of brain to LF of heart, and the second column is the interplay of brain to heart HF.

Subsequently, comparison of the interplay coefficients from brain to heart among two groups of saccade tasks was conducted, significant difference was found in the interplay coefficients from brain to LF of heart (shown in Fig. 5). And there were no significant differences in the interplay coefficients from brain to HF of heart. The main significant differences were found in the prefrontal lobes that closely related to cognition and memory (p = 0.0163).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of different frequency bands of brain to heart interplay coefficients under two groups of saccade tasks. The results of the Wilcoxon test, with statistically significant regions shown in blue, and non-significant electrodes in red areas. The first row is the interplay of brain to LF of heart, and the second row is the interplay of brain to HF of heart.

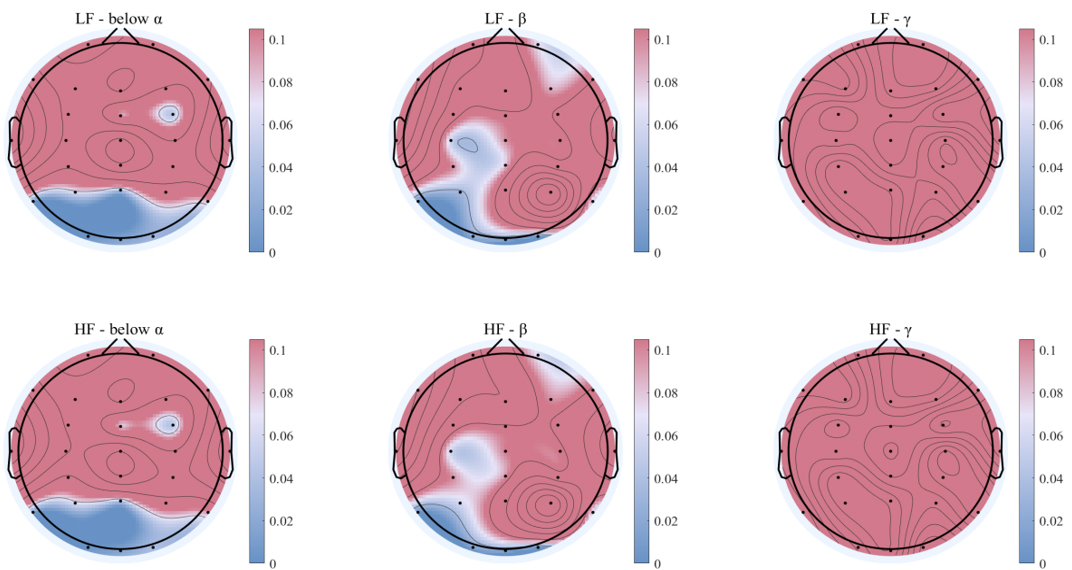

The interplay patterns from LF and HF of the heart to the brain under the two groups saccade tasks were shown in Fig. 6A,B. As can be seen, the interplay coefficients from LF and HF of the heart to EEG different bands were the most significant below alpha band under the two groups saccade tasks (Table 2). The average brain interplay coefficients were all positive and the values of average brain interplay coefficients of reflexive saccade task was greater than voluntary saccade task.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Heart to brain interplay coefficients. The first row is for reflexive saccade task, the second row is for voluntary saccade task. (A) Interplay coefficients from the LF of the heart to the brain for participants performing two groups of saccade tasks, and the subplots in each row represent the interplay coefficients from the heart LF to different frequency bands of brain. (B) Interplay coefficients from the HF of the heart to the brain for participants performing three saccade tasks, and the subplots in each row represent the interplay coefficients from the heart HF to different frequency bands of brain.

| Task | LFToBrain (Mean) | HFToBrain (Mean) | ||||

| Below |

Below |

|||||

| Reflexive | 0.9370 | 0.3118 | 0.1772 | 1.3447 | 0.4422 | 0.2508 |

| Voluntary | 0.8007 | 0.2705 | 0.1644 | 1.1446 | 0.3826 | 0.2324 |

The positive interplay coefficients suggest that heart is positively correlated to brain [43]. And both the interplay coefficients from LF and HF of the heart to EEG different bands exhibit reflexive saccade task is greater than voluntary saccade task. This may be due to the limited attentional and cognitive resources required for the brain in the reflexive saccade task, and the brain has more capacity to contact the heart. In contrast, voluntary saccade tasks require a higher degree of attention and cognitive resources, and the higher cortex of the brain is more involved, requiring more resources to be devoted to processing information and performing tasks. Although the heart is still in contact with brain, the interplay from heart to brain may be affected to some extent with the increase in cognitive resources and the complexity of the task [45].

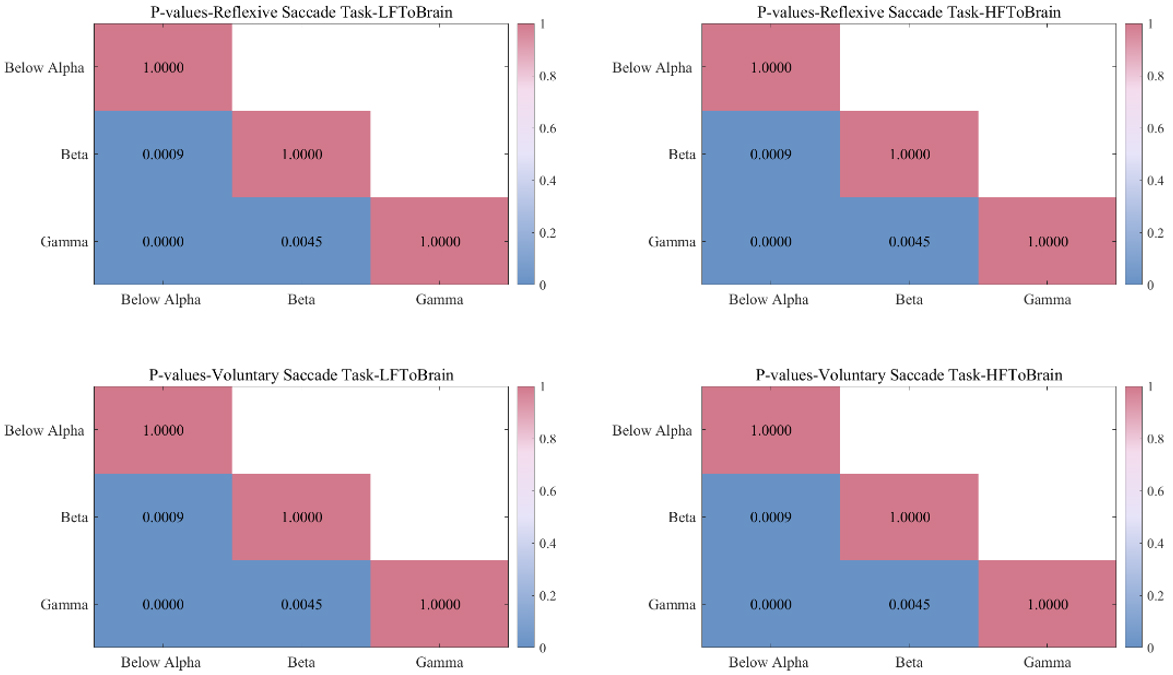

Similarly, to verify that the interplay coefficients from the LF and HF of the heart to the brain are most significant below alpha band, we also did a p-value test for the different frequency bands under the two groups of saccade task (Fig. 7). p-values were obtained by Friedman’s test and Bonferroni correction. As can be seen in the figure, there are significant differences below alpha band.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

p-values between different frequency bands for the two groups of saccade tasks. The first row is the reflexive saccade task, the second row is the voluntary saccade task. The first column shows interplay from LF of the heart to brain and the second column shows interplay from HF of the heart to brain.

Comparison of the interplay coefficients from heart to brain among different groups of saccade tasks was conducted, significant difference was found in the interplay coefficients from LF and HF of heart to brain (shown in Fig. 8). Significant differences were observed in the interplay coefficients from both the heart LF and HF to the brain below alpha band in the parietal (p = 0.0203) and occipital regions (p = 0.0097).

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of heart to brain different frequency bands of interplay coefficients under two groups of saccade tasks. The results of the Wilcoxon test, with statistically significant regions shown in blue, and non-significant electrodes in red areas. The first row shows interplay from LF of the heart to brain and the second row shows interplay from HF of the heart to brain.

The present study shows that the brain’s interplay with the LF and HF of the heart during the performance of saccade tasks exhibits opposite modes of action, with a negative coefficient of interplay between the brain and the LF of the heart and a positive coefficient of interplay between the brain and the HF of the heart. The highest interplay coefficients were found in the gamma frequency band. This phenomenon may be because gamma band is closely related to higher cognitive functions such as attention, information processing and memory [46]. And when performing a saccadic task, it requires to find a balance between brain and heart to optimize cognitive performance [47]. This finding provides new insights into how the brain regulates the autonomic nervous system under different cognitive loads. For brain to heart interplay coefficients between different tasks, we found significant differences between the reflexive saccade task and voluntary saccade task, particularly in the prefrontal lobes region. Previous studies have indicated that the prefrontal lobe is critically involved in a variety of cognitive functions, including attention, decision-making, working memory, and the regulation of emotional responses [48, 49]. And the prefrontal cortex plays a pivotal role in executive functions by orchestrating goal-directed behavior, maintaining cognitive flexibility, and modulating top-down control processes [50]. These findings are consistent with our observations of brain to heart interplay coefficients, leading us to reasonably infer that the interplay coefficients from brain to LF of heart may be related to the increasing of cognitive.

For the heart to brain interplay coefficient, the present study shows that the LF and HF of the heart with the brain interplay during the performance of saccade tasks exhibit same modes of action, their interplay coefficients were all positive. The highest interplay coefficients were found below alpha band. This phenomenon may be due to the fact that the below alpha band is associated with rest and relaxation states [51]. By interplay with the brain below alpha band, the heart might contribute to the efficient processing of visual and motor information, thus optimizing task performance. The variation induced by heart brain interplay below alpha band is likely to be essential for maintaining focused attention and preventing cognitive overload during tasks that require quick and coordinated visual-motor processing [52]. For heart to brain interplay coefficients between different groups of saccade tasks, we found significant differences in heart to brain interplay coefficients, particularly below alpha band in the parietal and occipital regions, as well as to the beta band in the occipital regions. Research [53, 54, 55] has demonstrated that the below alpha band in the parietal and occipital regions and the beta band in the occipital regions are associated with memory and visuomotor attention. The parietal region, which is integral for integrating sensory information, plays a crucial role in spatial awareness and attention, particularly during tasks involving visual processing [56, 57]. Similarly, the occipital region, which is often associated with active cognitive tasks such as visual attention and motor planning [58]. These findings align with our observations of heart to brain interplay, leading us to reasonably infer that the interplay between the heart and the brain can respond to the complexity of the task.

The findings may have broader implications for understanding the role of the ANS in cognitive processes. While the role of the brain in cognitive function has been well-established, the contribution of the ANS, particularly through its influence on BHI, may be more significant than previously thought. The ANS is responsible for regulating a variety of physiological processes, including heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, and respiratory function, and it interacts closely with the CNS to maintain homeostasis and manage stress responses [59]. These interplays are not just crucial for maintaining basic physiological stability but are also integral to higher cognitive functions, such as attention, memory, and emotional regulation [60]. In fact, recent research has highlighted that disturbances in autonomic regulation can impair cognitive performance and emotional processing, particularly in stressful or demanding situations [61, 62].

The synchronization between brain and heart observed in this study highlights how these two systems collaborate to ensure that cognitive resources are efficiently allocated and managed during complex tasks. When these systems are in sync, the brain is able to allocate attentional and cognitive resources more effectively, improving performance and efficiency in tasks that require high levels of concentration or emotional regulation [63]. This interdependence between the heart and brain is particularly evident during complex or stressful cognitive tasks, where the brain’s need for resources is matched by the body’s physiological responses.

The present study explored the brain-heart interplay under two groups of saccade tasks. It showed that the most significant interplay from heart to brain happened below alpha band, while the most significant interplay from brain to heart happens in gamma band. For the two groups of saccade tasks, the interplay coefficients were shown to be strongly correlated with the executive function of saccade task, particularly in the prefrontal occipital region and parietal lobes. This bidirectional interplay mechanism reveals a complex and strong connection between the heart and the brain, providing an important perspective for understanding psychophysiological health. There are some limitations to this study, including differences in the strength of brain-heart interplay due to different saccade tasks and uncertainty about their mechanisms. In addition, the relationship between specific regions of the brain and the autonomic nervous system still needs to be further explored to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamic nature of BHI. Future research could focus on these areas to deepen the understanding of BHI and how the balance between the brain and heart in the context of these tasks could be disrupted in clinical populations, such as individuals with autonomic dysfunction or cognitive impairments. By further exploring the role of heart brain interplay in cognitive performance, we may uncover new diagnostic markers or therapeutic targets for cognitive disorders.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional policy or privacy restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

JLY: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, and writing – review and editing. YZZ: data curation, investigation, and writing –original draft. RQL: formal analysis and investigation. XFL: collected and analyzed the data, software and supervision. WJZ: validation and visualization. YCH: validation and investigation. HQH: visualization and formal analysis. LCL: funding acquisition, visualization and supervision. JSZ: formal analysis and validation. MY: methodology and writing – review and editing. MSZ: funding acquisition, conceptualization and writing – review and editing. XLL: funding acquisition, software, formal analysis and writing – review and editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hebei University Affiliated Hospital (HDFYLL-KY-2024-099). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who also confirmed that they had no history of neurological, cardiovascular, or other related diseases.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by Expert Recommended Original Exploration Project (62450100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32030045), STI2030-Major Projects 2021ZD0204300, the Interdisciplinary Research Program of Natural Science of Hebei University (DXK202205), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62403180) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (F2022201037).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.