1 Eye School of Chengdu University of TCM, 610000 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

2 Ineye Hospital of Chengdu University of TCM, 610000 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

3 Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province Ophthalmopathy Prevention & Cure and Visual Function Protection with TCM Laboratory, 610000 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

Abstract

PANoptosis represents a novel form of programmed cell death regulated and controlled by the PANoptosome. It encompasses the essential features of apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis and combines elements from each process. PANoptosis contributes to the development of various diseases, including bacterial and viral infections, tumors, inflammatory diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases, which offers insights into the pathological mechanisms of these diseases and potential treatments. Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are nerve cells located in the final segment of the retina, which belongs to the central nervous system. The loss of RGCs caused by various diseases cannot be reversed. Consequently, safeguarding RGCs from loss is a crucial goal in the treatment of diseases that cause RGCs death (such as trauma, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy). Research on the multiple modes of death of RGCs has made some progress and, recently, PANoptosis has been observed during the death of RGCs in different models. In this article, we first give an overview of PANoptosis and summarize the fundamental mechanisms and crosstalk between apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis, as well as the characteristics of these three modes of cell death that occur in RGCs. Finally, we discuss the current status of research on PANoptosis in neurons and RGCs to establish a theoretical basis for the mechanism of PANoptosis as a novel target for safeguarding RGCs from loss.

Keywords

- cell death

- retinal ganglion cells

- molecular mechanisms

- PANoptosis

- apoptosis

- necroptosis

- pyroptosis

As a group of nerve cells at the end of the retina, retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) play an essential role in the central nervous system. Their axon fibers converge to form optic nerve bundles, creating the only neural pathway to transmit visual information from the retina to the brain [1]. The death of RGCs is a typical feature of traumatic optic neuropathy, glaucoma, and other diseases that cause optic nerve injury [2]. Moreover, the loss of RGCs resulting from optic nerve injury is irreversible and often results in different degrees of visual impairment in patients and, in severe cases, blindness. In clinical treatment, inhibiting the death of RGCs and protecting RGCs from loss is a meaningful way to protect the optic nerve and improve vision in patients with optic neuropathy, and this has been a complex problem in the study of optic nerve protection. It is worth noting that although the loss of RGCs is most often mentioned in the pathogenesis of glaucoma, it also occurs in the pathological process of traumatic optic neuropathy [3] and diabetic retinopathy [4].

Cell death mainly presents two basic modes: accidental cell death (ACD) and regulatory cell death (RCD). Among them, programmed cell death (PCD), an essential subtype of RCD, is characterized by occurring under physiological conditions and being precisely regulated by specific biochemical cascades [5]. Apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis are categorized as RCD forms. Apoptosis was first named by John Kerr in 1972 [6], and since then, other forms of PCD have been identified. With the continuous deepening of research on the mechanism of cell death, the traditional belief that the three independent forms of cell death, apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis, have significant interactions and regulatory networks among their internal molecular pathways has overturned the previous theoretical understanding that cell death models are independent of each other. In this context, a new concept of procedural cell death, PANoptosis, has been proposed [7]. This phenomenon exhibits the core molecular and functional characteristics of apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis, but a single pathway cannot fully explain or cover all of its features. As a new mode of cell death, PANoptosis was first confirmed in the study of the pathological mechanism of infectious diseases. Later, relevant studies showed that its scope of action has expanded from bacterial and viral infections to various pathological processes such as malignant tumors and neurodegenerative diseases [8, 9, 10, 11].

Apoptosis of RGCs plays a critical role in optic nerve injury pathology. In glaucoma, it is the primary mechanism leading to RGC death [12]. However, apoptosis alone cannot thoroughly explain the cause of death of RGCs, and necroptosis and pyroptosis also occur. Apoptosis inhibitors merely postponed RGC death post-optic nerve injury without preventing it [13]. This suggests that adopting a multi-pathway joint intervention strategy may provide a new treatment approach for preventing and treating RGC death caused by optic nerve injury. Recently, PANoptosis of RGCs has been observed in several different models. As the only clearly defined crosstalk mode of cell death, PANoptosis is of great significance in studying the pathological mechanisms and treatment of diseases. This article explores the molecular pathways of apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in RGCs and reviews advancements in PANoptosis’ role in RGCs death. In addition, research prospects are indicated, with the hope of providing ideas for discovering new targets to protect RGCs from loss and finally serving clinical diagnosis and treatment.

PANoptosis, a novel form of programmed cell death, was introduced in 2019 by American scientist Malireddi and colleagues [7]. PANoptosis embodies the defining characteristics of apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis, regulated by the PANoptosome [14]. This intricate, multi-protein complex integrates essential regulators from these PCD pathways, triggering their simultaneous activation [15]. To date, researchers have uncovered four distinct types of PANoptosomes: the Z-DNA-binding protein 1 (ZBP1) PANoptosome [14], the absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) PANoptosome [15], the receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) PANoptosome [16], and the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing protein 12 (NLRP12) PANoptosome [17].

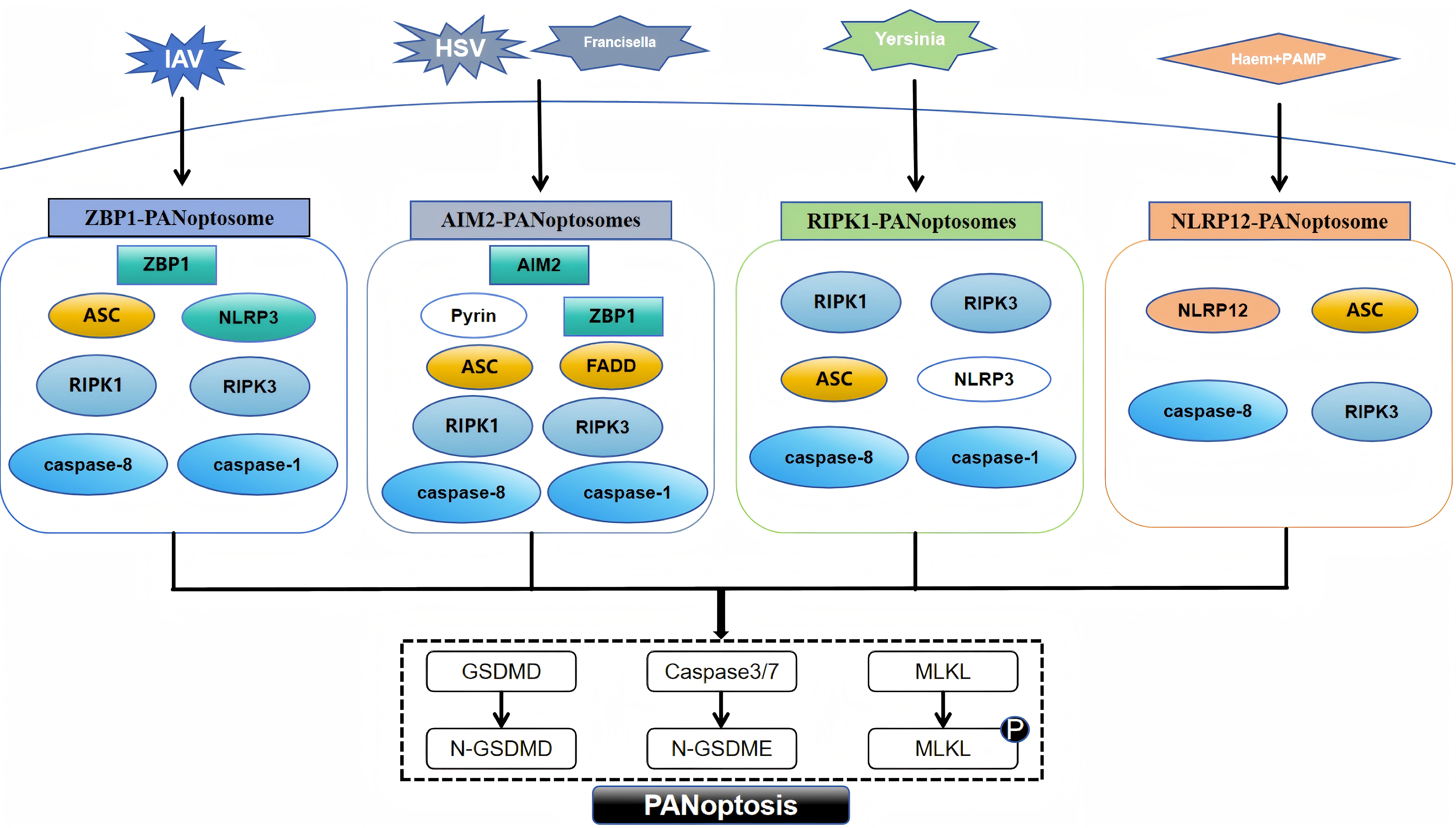

The ZBP1 PANoptosome initially appeared in bone marrow-derived macrophages of mice exposed to the influenza A virus [18]. This complex primarily consists of ZBP1, alongside key components such as apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3), caspase-8, caspase-1, RIPK1, and receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) [19]. Caspase-6 is an effector caspase involved in apoptosis, and a recent study found that when caspase-6 binds to RIPK3, it strengthens the association between RIPK3 and ZBP1 and thus promotes the assembly of the PANoptosome mediated by ZBP1. This enhancing effect is not related to the caspase activity of caspase-6, which indicates that caspase-6 acts as a scaffold in the ZBP1-mediated assembly of the PANoptosome [20]. The identification of the AIM2 PANoptosome revealed that its composition includes AIM2, ZBP1, ASC, pyrin, caspase-1, caspase-8, RIPK1, RIPK3, and Fas-associated death domain (FADD). After infection with herpes simplex virus one and Francisella, AIM2 regulates the innate immune sensors pyrin and ZBP1 to mediate the assembly of AIM2 PANoptosomes [15]. Yersinia infection induces the formation of RIPK1 PANoptosomes in macrophages. These consist of RIPK1, RIPK3, caspase-8, NLRP3, ASC and caspase-1 [21]. When stimulated by haem and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), NLRP12 mediates the activation of the PANoptosome, which consists of NLRP12, ASC, caspase-8, and RIPK3 [17]. The assembly of the above four types of PANoptosomes is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Assembly of different PANoptosome. PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; ZBP1, Z-DNA-binding protein 1; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein with a caspase recruitment domain; RIPK1, receptor-interacting protein kinase 1; AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; FADD, Fas-associated death domain; NLRP12, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing protein 12; NLRP3, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing protein 3; RIPK3, receptor-interacting protein kinase 3; GSDMD, gasdermin D; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein; IAV, influenza A virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; GSDMD, N-terminal fragment of Gasdermin-D; N-GSDME, N-terminal fragment of Gasdermin-E. Fig. 1 was drawn using WPS Office (12.1.0.17158, Kingsoft Corporation, Beijing, China).

Although the PANoptosome, which triggers assembly by sensing different stimuli, contains different sensors and regulators, the proteins that make up the PANoptosome fall into three main categories: (1) sensor proteins that sense PAMPs and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as ZBP1 and NLRP3; (2) adaptor proteins with caspase recruitment domains, such as ASC and FADD; and (3) those with catalytic effects, including RIPK1, RIPK3, caspase-1 and caspase-8 [7, 22, 23]. In PANoptosis, sensor proteins recognize different PAMPs or DAMPs, initiate assembly of the PANoptosome, and ultimately activate apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis via different proteins with catalytic effects.

PANoptosis plays an integral role across various diseases, such as infectious diseases caused by bacteria or viruses, neoplasms, inflammatory disorders, and neurological degeneration [8, 9, 10, 11]. Recent research on PANoptosis has mainly focused on the above diseases. There are also other, less studied examples, such as how exposure to copper triggers inflammation and PANoptosis via the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/nuclear factor

In recent years, the diagnostic and prognostic potential of PANoptosis-related genes in tumour diseases has also been continuously developed, for example, in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [27], lung adenocarcinoma [28, 29], breast cancer [30], colon adenocarcinoma [31], renal cell carcinoma [32, 33], and pancreatic adenocarcinoma [34]. Thus, it provides new ideas for the effective management and personalized treatment of tumour patients.

Trauma, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and other diseases can cause optic nerve injury, and a large number of RGCs die, resulting in RGCs axonal damage. Nonetheless, the process behind the death of RGCs is still unclear. It has been reported that apoptosis of RGCs is the main cause of death of RGCs in glaucoma [12, 35]. Apoptosis is the most common form of PCD [36] and is mediated by caspases [37], which can activate related internal or external pathways. This results in cell fragmentation and cell clearance by phagocytes, which differs from nucleolysis and cell swelling and rupture during cell necrosis. Its morphological features include cell shrinkage, chromosome shrinkage, DNA breakage, cell membrane blistering, and the formation of apoptotic bodies [38].

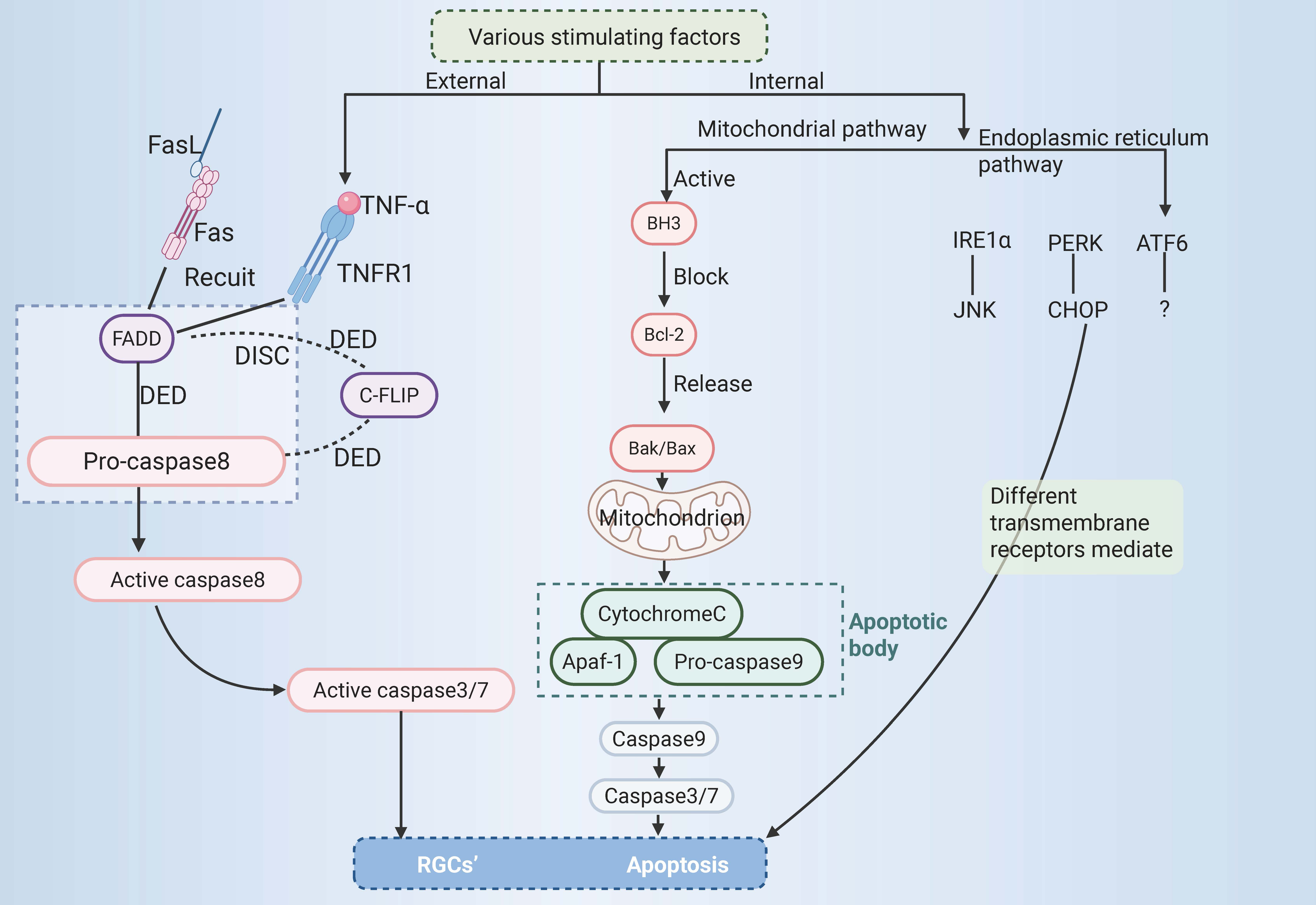

At present, apoptosis is mainly mediated by external and internal pathways, which can be categorized into the mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) pathways. The external pathway of apoptosis, also known as the death receptor pathway, is activated by changes in the extracellular environment [5]. After binding with specific death ligands, the death receptor receives the death signal outside the cell, activates the apoptosis mechanism inside the cell, and thus induces apoptosis. Currently, three primary death receptor signalling pathways are recognized in apoptosis, namely, the Fas, tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1), and tumour necrosis factor

The binding of apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 to cytochrome C might initiate the activation of caspase-3 and thus result in apoptosis. In this context, the intrinsic mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis pathway was first proposed [47]. The intrinsic apoptosis pathway is activated by stimulation by intracellular signals and may be triggered by various mechanisms, such as ER stress [48] and DNA damage [49]. The key regulators of the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis are the Bcl-2 family of proteins, which influence the process of apoptosis by modulating the permeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane. The Bcl-2 family of proteins regulates apoptosis via three types of histones, namely, Bcl-2 homology domain 3 (BH3) protein, executioner proteins (such as Bcl-2-Associated X protein (Bax) or Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer (Bak)), and antiapoptotic proteins (such as Bcl-2). The antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 is blocked by the BH3 protein, and the key effector factors in apoptosis, namely, the executioner proteins Bak and Bax, are released. This results in mitochondrial damage, an increase in the permeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane, and the release of many molecules, including cytochrome C [50]. Cytochrome C combines with apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 and procaspase-9 to form apoptotic bodies [51], which then activate and initiate the maturation of caspase-9, initiate the activation of the caspase cascade and then activate the downstream effectors caspase-3 and caspase-7, leading to apoptosis [52]. The ER is the leading site of protein assembly, folding, modification, and transport [53], and it is also involved in essential processes such as anabolic metabolism of lipids and regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis [54, 55]. A short period of ER stress can restore ER homeostasis by processing unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER via an unfolded protein response, thus enabling cell survival. However, long-term ER stress can lead to multiple forms of cell death, including apoptosis [56]. Apoptosis in cells triggered by stress in the ER involves three key transmembrane receptors, namely, inositol-requiring enzyme 1

In the 1990s, it was reported that RGCs undergo apoptosis (a mode of cell death) after acute (axotomy) [60] and chronic injury (experimental glaucoma) [61] to the optic nerve. A range of triggers, such as a lack of neurotrophic factors, oxidative stress, stress in the ER, dysfunction of mitochondria, neuroglial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation, can induce apoptosis in RGCs [62]. Apoptosis of RGCs can be mediated by external or internal pathways and can also be triggered via various mechanisms, including exogenous death receptor pathway, endogenous mitochondrial pathway, and ER pathway.

As the external pathway of apoptosis of RGCs, the death receptor pathway has been extensively studied, including the Fas receptor and TNFR1, which correspond to the ligands FasL and tumour necrosis factor

The mitochondria-mediated intrinsic apoptosis pathway also plays a vital role in the apoptosis of RGCs. The apoptosis of RGCs induced by acute and chronic damage to the optic nerve involves the mitochondria-mediated intrinsic pathway of apoptosis [71]. The key regulatory factors of the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis are the Bcl-2 family of proteins, and the complex interactions between the Bcl-2 family of proteins also play a key role in regulating the apoptosis of RGCs, the most critical factor is the executioner protein, Bax. The death of RGCs after optic nerve injury is Bax-dependent. Once Bax is activated, it can cause irreversible damage to mitochondria, which triggers a cascade of reactions that eventually lead to apoptosis of RGCs [72]. In a model of optic nerve damage in mice where the Bax gene was knocked out, RGCs were protected [72]. Another intrinsic pathway of apoptosis of RGCs is mediated by ER stress. ER stress-induced apoptosis is mediated by the IRE1

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. RGCs’ apoptosis. RGCs, retinal ganglion cells; TNF-

Necroptosis, also known as programmed necrosis, has a similar mechanism to apoptosis and is morphologically similar to necrosis [82], hence the name necroptosis. In necroptosis, the apoptosis pathways are inhibited [83]. Its morphological characteristics are as follows: significant destruction of the integrity and structure of the cell membrane [84], swelling of organelles, gradual translucency of the cytoplasm, and significant disintegration of the ER. The cell volume can be significantly reduced or enlarged due to local swelling, the genome and DNA are randomly degraded by cells [85], and necrosomes are usually produced [86].

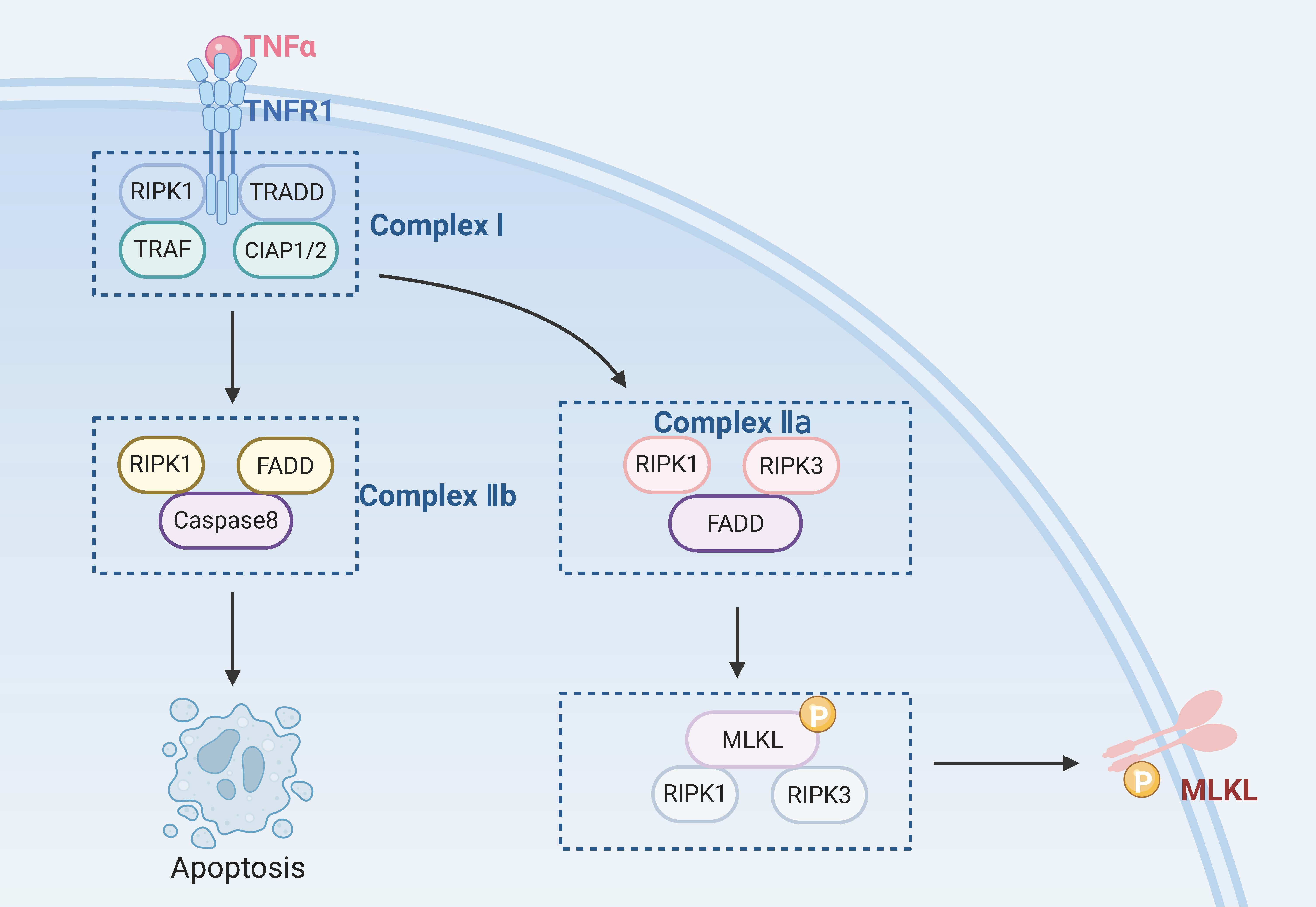

Caspase-8 is a key negative regulator of necroptosis. Cells will undergo necroptosis when caspase-8 is inhibited and the apoptosis pathways are blocked [87]. However, Duprez et al. [88] suggested that inhibition of caspase-8 may not always be necessary to trigger necroptosis in vivo. Induction of death receptors is a necessary condition for the occurrence of necroptosis. Known death receptors include the TNFR family (e.g., TNFR1), pathogen recognition receptors (e.g., TLR3), interferon receptors, DNA-dependent activators of interferon regulatory factors, and intracellular RNA and DNA receptors [89, 90]. These death receptors bind to the corresponding ligands and trigger the necroptosis pathway. The most critical molecules in this process are RIPK1, RIPK3, and mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) [91].

When TNF-

Necroptosis can be caused by various pathogenic stimuli, such as TNF-

Necroptosis occurs in various models of neurological diseases and has been studied directly and extensively in ophthalmic diseases. It has been reported [99] that in a model of transient retinal ischaemia, retinal cells undergo necrosis rather than apoptosis in the first 3 days after ischaemia–reperfusion (I/R). The endogenous factors released by the dead cells can initiate a prolonged neurotoxic pro-inflammatory response in the retina, mediating retinal damage after I/R. A direct role of necroptosis has also been demonstrated in models of retinal detachment [100] and retinitis pigmentosa [101].

The death of RGCs is the main pathophysiological cause of irreversible blindness and visual impairment caused by optic nerve injury, which is of great significance for the treatment of ocular neurodegenerative diseases. Rosenbaum et al. [102] reported that necroptosis of the RGC layer occurred after six hours in rat models of acute high intraocular pressure (aHIOP). Huang et al. [103] found that RIP3 was mainly expressed in RGCs in rats, and the expression of RIP3 was significantly upregulated in the early stage of aHIOP. Dvoriantchikova et al. [104] found that RIPK1 and RIPK3 were present throughout the retinal layer in I/R, especially in the ganglion cell layer containing RGCs, and found an increase in the expression of pro-inflammatory markers. Many RIPK1- and RIPK3-specific immunostaining locations were also seen in RGCs after oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD). Using necrostatin 1 (Nec-1), a necroptosis inhibitor, increased the survival rate of RGCs. Therefore, the level of retinal damage after I/R can be significantly reduced by preventing programmed necrosis of RGCs. The expression of many death receptors, such as TNFR1 (Tnfrsf1a), tumour necrosis factor

Nec-1 is a selective allosteric inhibitor of RIPK1 that reduces the formation of necrosomes and thereby promotes a series of reactions in the subsequent phosphorylation of MLKL and a series of necrotic cascades, such as cell membrane breakdown [106]. Nec-1 can also inhibit the expression of RIP3 in ganglion injury [107]. A novel RIPK1 inhibitor, Ripa-56 [108], has a more substantial off-target effect than Nec-1. It can reduce the loss of RGCs and the thickness of the RGC layer and bipolar cell layer in a retinal excitotoxicity model of glaucoma by alleviating necroptosis. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 may indirectly regulate necroptosis by regulating the expression of RIP3 [109]. Zhang et al. [110] studied TNF-induced necrosis of NIH 3T3 cells and found that RIP3 regulates TNF-induced excess production of reactive oxygen species by activating metabolic enzymes and leads to necrosis by destroying cell membranes and organelles. Timosaponin B-II, an antioxidant monomer extracted from sea cucumber, reduces necrosis of RGC-5 by inhibiting the accumulation of reactive oxygen species [111]. TNF-

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. RGCs’ necroptosis. TRADD, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 associated death domain protein; TRAF, TNF receptor-associated factor; CIAP1/2, cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1/2. Created with www.biorender.com.

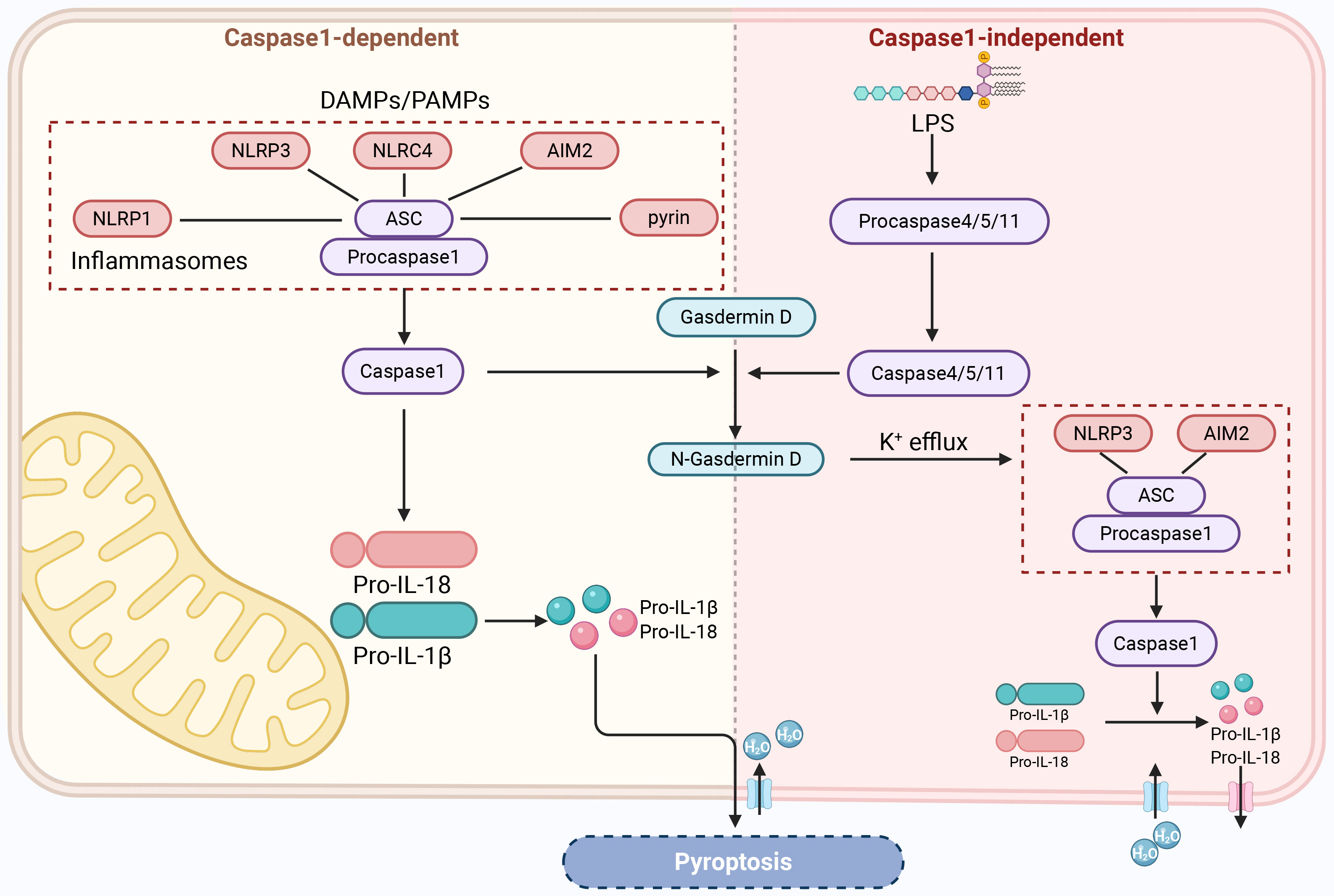

As early as the 1990s, researchers observed that macrophages exposed to Salmonella or Shigella fowleri caused cell death and released large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines [114]. Since then, this mode of cell death has gradually been found to be caspase-1-dependent and distinct from apoptosis, and in 2001, it was named caspase-1-dependent programmed necrosis, and the term “pyroptosis” was first introduced [115, 116, 117, 118]. Pyroptosis is a form of inflammatory cell death driven by gasdermin D (GSDMD) [119]. Although the process of pyroptosis also involves features similar to apoptosis, such as nuclear condensation, membrane foaming, caspase dependence, and DNA breakage, it is significantly different from other forms of PCD in terms of morphological and biochemical characteristics [120]. Morphologically, during pyroptosis, various inflammatory bodies activate caspase-1, lyse GSDMD to form transmembrane pores, and cleave inactive precursors of interleukin (IL) to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1

In the typical inflammasome activation pathway mediated by caspase-1, caspase-1 acts as a proenzyme in the resting state and forms a typical inflammasome complex with different cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptors and ASC [124]. The main pattern recognition receptors include TLRs, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors, and AIM2-like receptors [125], which can recognize stimuli by PAMPs or DAMPs [126]. NLRP3 plays a crucial role in this process. When the sensor protein in the inflammasome complex is NLRP3, the complex is called the NLRP3 inflammasome [127]. The inflammasome interacts with procaspase-1 via the caspase recruitment domain and then undergoes self-cleavage to form active caspase-1 [120]. On the one hand, active caspase-1 induces the conversion of precursors of IL-1

The atypical inflammasome activation pathway is mediated by caspase-4 and caspase-5 (caspase-11 in mice) and is primarily activated by lipopolysaccharides. Lipopolysaccharides secreted by Gram-negative bacteria bind to the N-terminal domain of caspases 4, 5, and 11 and activate these caspases to mediate pyroptosis [132]. Activated caspases 4, 5, and 11 cleave GSDMD to form N-GSDMD, which results in the same cleavage as caspase-1, resulting in pore formation in the cell membrane and pyroptosis [133]. At the same time, N-GSDMD induces signal transfer via potassium efflux to NLRP3 or the AIM2 inflammasome, which causes activation of caspase-1 [134, 135, 136]. Activated caspase-1 cleaves the precursors of IL-1

In the whole retina, pyroptosis can occur in every retinal layer, but cells undergoing pyroptosis are mainly RGCs, and the characteristic molecule of pyroptosis, GSDMD, is primarily expressed in the innermost layer of the retina (that is, the RGC layer). When RGCs were labelled with an antibody against neuronal

It is generally believed that damage to RGCs occurs mainly in glaucoma, but it also occurs in many other eye diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy and ischaemic or demyelinating optic neuritis [142]. Diabetic retinopathy is a common microvascular complication usually manifested by specific changes in retinal microvessels, but it can also cause retinal nerve damage [143]. In a study, it has been found that RGCs in diabetic retinopathy underwent pyroptosis, and cells that were positive for caspase-1, GSDMD, IL-1

In addition, the activation of microglia or Müller cells and the death of RGCs may exhibit mutual crosstalk. When stimulated, microglia and other cells are activated and release pro-inflammatory factors, which cause widespread toxicity to the axons, cell bodies, and synapses of RGCs [145]. Microglia are resident immune cells essential for the development and function of the nervous system and play an important role in mediating the pathological process of retinal and optic nerve diseases. Many studies have shown that retinal I/R not only directly causes the death of RGCs but also triggers neuroinflammation and activates microglia [132, 146]. Activated microglia initiate pyroptosis by triggering the cleavage of GSDMD and promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thus mediating the death of additional RGCs. Inhibition of caspase-1 and knockout of the GSDMD gene reduce the RGC death rate and alleviate retinal damage [131]. NLRP3 is the best-characterized member of the family of inflammatory bodies [147] and plays an important regulatory role in various inflammatory diseases [148, 149]. NLRP3 inflammatory bodies can promote the release of mature pro-inflammatory cytokines and induce the death of RGCs. In models of partial optic nerve compression injury, NLRP3 was also upregulated in microglia, leading to the upregulation of caspase-1 and the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1

The above studies have shown that RGCs, microglia, astrocytes, and Müller cells are all likely to undergo pyroptosis after specific stimulation. Pyroptosis of RGCs directly leads to their loss, whereas pyroptosis of microglia, astrocytes, and Müller cells also leads to the death of RGCs via the release of pro-inflammatory factors. The pyroptosis pathways of RGCs are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. RGCs’ pyroptosis. DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; NLRC4, NOD-like receptor family CARD domain-containing protein 4; LPS, lipopolysaccharide. Created with www.biorender.com.

While apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis are typically examined in isolation, these cell death pathways frequently intersect and influence one another. When investigating the molecular underpinnings of diseases and developing therapies, a narrow focus on just one of these mechanisms often yields limited or suboptimal outcomes. By delving deeper into the interplay between these distinct forms of cell death, we can unravel the intricate regulatory networks governing cellular demise. This comprehensive understanding will pave the way for more effective strategies to enhance or suppress cell death, ultimately advancing the treatment of various diseases.

Caspase-8 is the central regulator of apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis, orchestrating their interplay. As the primary initiator of apoptosis, caspase-8 activates the extrinsic pathway upon detecting cell death receptor signaling [154]. However, caspase-8 can also inhibit necroptosis mediated by RIPK1 and RIPK3 [154, 155]. Cylindromatosis protein has been identified as a key substrate in this inhibition process. Caspase-8 lyses cylindromatosis protein to generate pro-survival signals and inhibit the occurrence of necroptosis [156]. On the other hand, caspase-8 activates pyroptosis by cleaving gasdermin D and gasdermin E [157]. Emerging research on pyroptosis has primarily centered on the role of GSDMD and gasdermin E within the gasdermin family, particularly their cleavage and activation. However, these studies have also shed light on the involvement of the metabolite

Previously, MLKL was believed to compromise the plasma membrane’s integrity and facilitate necroptosis solely. However, it has recently been found that, in addition, necroptosis can interact with other RCD pathways via the mediating effect of MLKL. Necroptosis interacts reciprocally with other regulated cell death pathways [164]. The RIPK3-MLKL necroptosis pathway triggers NLRP3 inflammasome activation, resulting in IL-1

Beyond the well-established role of MLKL in necroptosis signaling and RIPK3’s ability to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome independently of MLKL, it’s worth noting that apoptosis also plays a significant part in triggering NLRP3 inflammasome activation. In both exogenous and endogenous apoptotic pathways, the emergence of pannexin-1 channels on the cell surface facilitates this process. This activation is further driven by the opening of plasma membrane channels and the subsequent efflux of potassium ions [169].

Neurons, the fundamental units of the nervous system, consist of cell bodies and synapses, which primarily link axons to dendrites [170]. Much like other cell types, neurons can undergo various forms of cell death—such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis—depending on the specific triggers they encounter. This neuronal cell death is frequently a hallmark of the pathological processes underlying many neurodegenerative disorders [171, 172]. Following apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis of neurons, which are types of neuronal cell death, have been shown to be crucial in diverse neurodegenerative diseases [173]. The underlying causes of neurodegenerative disorders stem from a combination of oxidative stress, impaired mitochondrial function, and neuroinflammation [174]. These factors are multifaceted, and varying sensory triggers can lead to distinct pathways of neuronal cell death. As scientific inquiry into neuronal cell death in neurodegenerative disorders advances, the therapeutic approach of targeting multiple pathways and mechanisms has proven effective in mitigating symptoms for patients suffering from these conditions. The concept of PANoptosis offers a groundbreaking lens through which to examine the interplay between apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis. Recognized as a crucial defense strategy against infections, PANoptosis has also emerged as a significant player in the progression of various non-infectious diseases. Cutting-edge research has revealed its involvement in the mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative disorders, marking it as a pivotal process in the death of neuronal cells.

In 2022, Yan et al. [175] first found by literature metrology and data mining that apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis could occur simultaneously in a model of I/R injury induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion and in vitro OGD-induced neuronal cell ischaemia and hypoxic injury. This suggests that PANoptosis may underlie the pathological mechanisms of I/R injury. In addition, PANoptosome components like NLRP3, ASC, RIP1, and RIP3 are also highly expressed, which indicates that the PANoptosome has a molecular basis in ischaemia-induced brain injury. Moreover, identifying gene characteristics and related regulatory axes of PCD in brain I/R injury supported the possibility that apoptosis, pyroptosis, necroptosis, and PANoptosis and their crosstalk might be associated with ischaemic stroke [176]. In ischaemic stroke, the key pathological features are inflammation and cell death. Oxidative stress, ER stress, and neuroinflammatory responses ultimately result in neuron death. The cyclic GMP-AMP synthase–stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS-STING) pathway is an integral part of the innate immune system [177] and also plays an important role in ischaemic diseases [178]. The cGAS-STING pathway can regulate PANoptosis via various pathways [179]. On the one hand, interferon-1 produced by the cGAS-STING pathway can promote the activation of ZBP1 and thus promote PANoptosis. On the other hand, the cGAS-STING pathway can regulate apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and, thus, PANoptosis.

Neuronal cell death also occurs during the pathological process of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Amyloid

The evidence outlined above offers a solid theoretical foundation for the existence of neuronal PANoptosis in neurodegenerative conditions. However, despite this groundwork, direct experimental validation of neuronal PANoptosis remains elusive. Chronic neuroinflammation in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion results in permanent neuron loss. In recent in vivo (mouse model of middle cerebral artery occlusion) and in vitro (OGD/R-treated HT22 cell model) experiments, the protein expression of the basic components of the PANoptosome (AIM2, ZBP1 and pyrin) and the expression of key markers of apoptosis (caspase-3 and GSDMD), pyroptosis (caspase-1 and GSDMD) and necroptosis (RIPK1, RIPK3 and MLKL) were significantly upregulated in the model group [181]. This was the first experimental demonstration of the occurrence of PANoptotic neuronal cell death under conditions of brain I/R, and the inhibition of PANoptosis by curcumin-pretreated olfactory mucosa mesenchymal stem cells demonstrated a neuroprotective effect. Upregulated levels of miRNA-423-5p in curcumin-pretreated olfactory mucosa mesenchymal stem cells modulated the microglial polarization-dependent nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2/nuclear factor-

Currently, theoretical support and experimental verification have shown that neuronal PANoptosis occurs in central nervous system diseases/neurodegenerative diseases, including ischaemic stroke, AD, brain I/R, epilepsy, and spinal cord injury. Some studies have proposed ways to reduce nerve damage by inhibiting neuronal PANoptosis. These findings indicate that neuronal PANoptosis could serve as a novel therapeutic focus for disease prevention and management.

In earlier study, the predominant pathway for neuronal cell death was widely believed to be apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death orchestrated by caspase activity. Researchers found that administering caspase inhibitors could successfully halt the apoptotic process in retinal ganglion cells, offering a potential therapeutic strategy [186]. However, in cases where caspase inhibitors alone are used, caspase activity is inhibited, which may only temporarily reduce the apoptosis rate. After exposure to TNF-

Previously, we reviewed apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in RGCs separately. Most existing research on RGC death examines distinct cell death mechanisms independently. As the body of research grows, shedding light on the intricate interplay between various forms of cell death, a pressing question emerges: do multiple cell death pathways operate concurrently in the demise of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs)? Moreover, what are the underlying mechanisms and interactions that link these pathways together? Exploring these connections could unveil critical insights into the complex dynamics of cellular demise. The research by Dvoriantchikova et al. [138] demonstrated that retinal I/R can concurrently initiate various forms of regulated cell death (RCD), like necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis. This study was carried out on the whole retina, and it was not clear whether these cell death pathways were activated simultaneously in RGCs. Following RNA-seq analysis, the research group discovered that in RGCs extracted 24 hours post-ischemia/reperfusion, there was a notable upregulation of numerous genes involved in apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis. Interestingly, these distinct cell death mechanisms were all concurrently triggered within the RGCs [105]. Experimental study based on optic nerve injury models [187] has shown that in the longitudinal synchronous analysis of 11 cell death modes, optic nerve stem cells mainly exhibit characteristic death pathways such as apoptosis, autolysis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis. Following retinal I/R injury, neuronal cell death manifests in various forms, including apoptosis, necroptosis, and ferroptosis. Inhibitors such as Z-VAD-FMK, Nec-1, and ferrostatin-1, which target these specific pathways, have been shown to enhance the survival of RGCs. However, the most promising approach is blocking multiple cell death mechanisms simultaneously. This multifaceted strategy holds significant therapeutic potential, offering a more robust defense against RGC loss and paving the way for more effective treatment options.

In recent studies, PANoptosis has been observed in infections, cancers, and neurological conditions. The aforementioned studies indicate that RGCs undergo apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis; investigations into their PANoptosis remain preliminary. Colocalization of lysed caspase-3 and

| Disease | In vivo/extracorporeal | Model | Cell death marker protein | PANoptosome member expression | Intervene | Mechanism | Reference resources |

| Ischemic stroke | In vivo | Mouse MCAO model | Apoptosis (caspase-3, caspase-8) | AIM2, ZBP1, Pyrin | CUR-OM-MSCs | Release miRNA-423-5p, inhibit NOD2/NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway, regulate microglial polarization and neuroinflammatory response | [180] |

| Necroptosis (RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL) | |||||||

| Pyroptosis (caspase-1, GSDMD) | |||||||

| Extracorporeal | OGD/R treated mouse microglia (BV2) and mouse hippocampal neurons (HT22) | Apoptosis (caspase-3, caspase-8) | AIM2, ZBP1, Pyrin | CUR-OM-MSCs | Release miRNA-423-5p, inhibit NOD2/NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway, regulate microglial polarization and neuroinflammatory response | [180] | |

| Necroptosis (RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL) | |||||||

| Pyroptosis (caspase-1, GSDMD) | |||||||

| Spinal cord injury | In vivo | Mouse spinal cord injury model | Apoptosis (Caspase3) | / | Zn ion | Regulating neuronal mitochondrial quality control under oxidative stress through the Lgals3 Bax pathway | [183] |

| Necroptosis (RIPK1, MLKL) | |||||||

| Pyroptosis (caspase1, GSDMD) | |||||||

| Spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury | In vivo | Rat SCIRI model | Apoptosis (caspase-3, caspase-7, caspase-8, Bax, Bad, Bcl-2) | / | H2S | Reduce neuroinflammation mediated by overactivated microglia | [184] |

| Necroptosis (RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL) | |||||||

| Pyroptosis (NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD) | |||||||

| Neuronal ischemia-reperfusion injury | In vivo | Rat aHIOP model | Apoptosis (caspase-3) | caspase-1, NLRP3, RIPK3 | / | / | [188] |

| Necroptosis (MLKL) | |||||||

| Pyroptosis (GSDMD) | |||||||

| Extracorporeal | R28 cells treated with OGD/R | Apoptosis (caspase-3, Bax, Bcl-2) | caspase-1, NLRP3, RIPK3 | / | / | [188] | |

| Necroptosis (RIPK3, MLKL) | |||||||

| Pyroptosis (NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD, IL-1β) | |||||||

| Acute glaucoma | In vivo | Mouse AOH model | Apoptosis (caspase-3, caspase-7, caspase-8, Bax, Bad, Bcl-2) | / | Melatonin | siRNA or Mdivi-1 treatment | [187] |

| Necroptosis (RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL) | |||||||

| Pyroptosis (NLRP3, caspase-1, ASC, GSDMD) | |||||||

| Glaucoma | In vivo | Mouse pH-IOP model | Apoptosis (cleaved-caspase3) | / | siRNA or Mdivi-1 treatment | Silencing Drp1 expression, inhibits ERK1/2-Drp1-ROS signaling pathway | [189] |

| Necroptosis (p-RIP1, p-RIP3, p-MLKL) | |||||||

| Pyroptosis (NLRP3, caspase1, GSDMD) |

MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; OGD/R, oxygen glucose deprivation/reperfusion; CUR-OM-MSCs, curcumin-pretreated olfactory mucosa-derived mesenchymal stem cells; AOH, acute ocular hypertension; Bad, Bcl-2-associated agonist of cell death; SCIRI, spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury; pH-IOP, pathologically high intraocular pressure; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; Drp1, Dynamin-related protein 1; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NOD2, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2; aHIOP, acute high intraocular.

The above experimental studies have, to some extent, confirmed the existence of PANoptosis in the retina or RGCs. There is a close relationship between RGC death and a series of diseases involving optic nerve damage, such as glaucoma, retinal ischemic injury, etc. Inhibiting a certain cell death alone can only temporarily delay RGC death, and the survival rate of RGCs is relatively low. The combination of inhibitors of multiple death modes is more effective. As a new mechanism of RGC death, how to protect RGCs from loss and protect the optic nerve by regulating PANoptosis is the future direction and key. PANoptosome is a complex composed of multiple proteins, and targeting its components provides potential for developing therapeutic strategies. The drugs investigated primarily focus on molecules like NLRP3, caspase-8, RIPK1, and RIPK3. The specific NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 [191, 192], developed based on the classic NLRP3 inhibitor glibenclamide skeleton, is continuously validated in experiments and clinical trials. Other NLRP3 inhibitors, such as DFV890 [193], are also undergoing early clinical trial research. Another potential way is to exert its effect by directly regulating PANoptosis. PANoptosis is involved in acute ocular hypertension (AOH) injury, and using melatonin to inhibit PANoptosis can exert neuroprotective effects [188]. Dickkopf-1 inhibits PANopsis in the retina of diabetes retinopathy rats [194]. In essence, the PANoptosome is a complex network of proteins and signaling pathways, and modulating these components to either trigger or suppress PANoptosis holds promise as a therapeutic approach. Ultimately, targeting multiple forms of cell death simultaneously—rather than focusing solely on apoptosis, pyroptosis, or necroptosis—offers a more effective strategy for achieving desired outcomes.

The demise of RGCs is a central pathological feature in numerous eye disorders, such as glaucoma, traumatic optic neuropathy, and diabetic retinopathy. This cellular loss is a multifaceted process involving apoptosis and other mechanisms like necroptosis and pyroptosis. The optic nerve, which serves as the sole conduit for transmitting visual signals from the retina to the brain, comprises RGC axons. Once RGCs are lost due to optic nerve damage, they cannot regenerate, leading to severe visual impairment or even total blindness, significantly impacting patient outcomes. Given the challenges in optic nerve regeneration, safeguarding RGCs from degeneration has emerged as a promising strategy for preventing and treating these conditions, offering a glimmer of hope for restoring patients’ vision.

Over the years, extensive research has delved into the processes of apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis related to retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death. While significant strides have been made in understanding PANoptosis, its specific role in the mechanisms underlying RGC death remains an area yet to be fully unraveled. During the death of RGCs in several different models, apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis occurred simultaneously, which is strong evidence for PANoptosis of RGCs. In addition, although the existence of the PANoptosome regulating the three modes of death of RGCs simultaneously has not been confirmed, some studies have found an increase in the expression of important components of the PANoptosome. PANoptosis has broad prospects in protecting RGCs from loss, but many issues still need to be addressed. While studies have shown that multiple cell death pathways are triggered concurrently in RGCs, the field remains underexplored, leaving significant gaps in our understanding. Specifically, it’s still unclear whether PANoptosis, a distinct form of cell death, plays a role in RGCs or the retina. This area warrants deeper investigation to shed light on these mechanisms. In addition, different stimuli can lead to different assemblies of PANoptosomes, and there are currently four known types of PANoptosomes. In future studies of PANoptosis of RGCs, it will be necessary to clarify the existence of the PANoptosome further and identify the key regulatory factors of the PANoptosome to control the PANoptosis of RGCs better to reduce the RGC death rate and protect the optic nerve. At the same time, we should also understand that in these diseases that cause optic nerve injury, changes in intraocular pressure or metabolic changes caused by oxidative stress and inflammation lead to functional damage and death of RGCs. If you are in such a pathological state all the time, cell death will continue to occur. Merely inhibiting PANoptosis cannot cure the disease.

In summary, PANoptosis can be used as a new target to protect RGCs from loss, and may provide new ideas for optic nerve protection in pathological states, which is worth further exploration by researchers in this field.

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; aHIOP, acute high intraocular pressure; AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; ATF6, activated transcription factor 6; c-FLIP, cellular FADD-like interleukin-1

XL and YJ conducted topic selection, YJ wrote the original manuscript, WQ and QK revised the manuscript and created charts. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Figs. 2,3,4 were created by BioRender, and we sincerely appreciate it.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82174444).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.