1 Department of Anesthesiology, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, 310053 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 Department of Anesthesiology, The Second Hospital of Jiaxing, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University, 314001 Jiaxing, Zhejiang, China

Abstract

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) is a central nervous system (CNS) complication seen in elderly patients, characterized by a decline in memory, comprehension, and attention in patients after surgery and general anesthesia. The pathophysiologic mechanisms of postoperative cognitive dysfunction are not well understood and effective means of prevention and treatment are currently lacking. Basic and clinical research, including the use of pre-clinical animal models of POCD, is advancing rapidly. In this paper, we review and summarize various factors that contribute to the development of POCD, including oxidative stress, autophagy, impaired synaptic function, and neuroinflammation, and describe the construction of animal models of POCD. By analyzing the gap between clinical and basic research, we propose recommendations for clinically relevant animal model development and the conducting of clinical studies to better understand the mechanisms and etiology associated with POCD. We aim to enhance understanding of the occurrence of POCD and to provide a more comprehensive perspective on the prevention and treatment of POCD.

Keywords

- postoperative cognitive dysfunction

- oxidative stress

- autophagy disorders

- impaired synaptic function

- neuroinflammation

- cognitive change

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) is a common neurological complication following surgery and general anesthesia [1], especially in elderly patients. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction seriously affects patients’ quality of life, prolongs hospitalization, and creates a heavy burden on society [2]. However, the etiologic and pathophysiologic mechanisms that trigger POCD warrants further research. As the population ages, the use of anesthesia in the geriatric surgical population is increasing. POCD is a new type of cognitive impairment that occurs after anesthesia and surgery, a complication characterized by impaired memory, decreased information processing, and decreased attention, which can be detected weeks to months after surgery and may be long-lasting [3]. Although a common complication of the central nervous system after surgery in elderly patients, it is often accompanied by a range of negative outcomes, such as mood and personality changes [3, 4]. Data from a prospective trial in a non-cardiac surgery population showed that the prevalence of POCD was as high as 30% [5]. According to a study by Brown et al. [6], patients who developed delirium after surgery experienced declines in multiple cognitive domains at one month and were more likely to develop POCD.

According to the available research, the occurrence and development of POCD are associated with various factors. Among them, neuroinflammation is considered to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of POCD and has become an important research topic in recent years. Animal and human studies have shown that surgical or anesthesia-induced neuroinflammation is a major cause of POCD development [7, 8]. Surgery-induced tissue damage activates the peripheral immune system and promotes an inflammatory response leading to neuroinflammation and degeneration [9]. The severity and duration of POCD are the result of several factors and therefore develop in different directions in different individuals [10]. The underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of POCD remain unclear, and preventive or ameliorative therapies are lacking. The effectiveness of several pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions based on current hypothesized mechanisms is still under investigation. Although POCD is a CNS disorder, the research on them is predominantly conducted by anesthesiologists rather than neuroscientists. The purpose of this review is to introduce POCD to a wide range of scientists and to facilitate communication between anesthesiologists and neuroscientists. Here, we first review the development history of POCD and then summarize key analyses to elucidate its mechanism for animal model development. Secondly, based on the existing research and evidence, we analyze the important mechanisms potentially involved in the pathogenesis of POCD. By summarizing the clinical studies on POCD and comparing them with the basic research, we can provide suggestions for future exploration.

POCD is a well-known surgical risks and was described as a “side effect” of anesthesia as early as 1887 [11]. Altered cognitive function in patients after anesthesia and surgery has been on physicians’ radar for over a hundred years. American dentist Zacheus Rogers was committed to a mental hospital in 1872 for nerve damage caused by nitrous oxide abuse [12]. At that time, it was widely recognized that infections and patients’ “somatic susceptibility” might be associated with changes in patients’ postoperative cognition [13]. At the time, reports of “insanity” and “death” from the use of anesthetics were on the rise throughout the United States [13]. In 1887, the American dentist Samuel J Hayes published a report linking anaerobic anesthetics to ventricular respiration and insanity, followed by a report on cases of insanity by the British psychiatrist George H. Savage [12]. Neuropathologist Cyril B. Courville published two articles on asphyxiating brain injury in 1936 [14, 15]. POCD attracted the attention of the medical community many years ago, but the causes and mechanisms of postoperative cognitive changes have not been well-studied. In 1955, Bedford first reported a series of neurological complications, such as impaired orientation and amnesia in elderly people with no preoperative abnormalities [4]. After the 1980s, multiple studies utilized detailed neuropsychological tests to assess cognitive changes after cardiac surgery [16, 17, 18]. The study found a decline in cognitive function in older patients after anesthesia and surgery, yet it was more than seven years before changes in cognitive function were detected [16]. In 1998, the International Study Group on Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction (ISPOCD) conducted a multicenter study that formally introduced POCD, a study with important implications for understanding and intervening in postoperative cognitive dysfunction [19]. Since then, the medical community has begun to conduct research into the clinical manifestations, incidence, and other aspects of POCD. An early study found that the incidence of POCD was relatively high after major operations such as cardiac surgery [20]. At the end of the last century, with the advancement of neuroscience and medical research, researchers began to explore the pathogenesis of POCD. It has been found that the patient’s factors, such as age, type of surgery, and underlying disease, are important risk factors for POCD. In recent years, with advances in mechanistic research, it has been found that factors such as inflammatory response and oxidative stress play an important role in the development of POCD.

Unlike delirium, there has never been a precise definition for POCD. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) is a disorder characterized by impairments across multiple domains that are dysfunctional, can persist long after surgery and anesthesia, and for which there is no standardized method of assessment [21]. Furthermore, postoperative cognitive dysfunction is not a clinical diagnosis but a variable operational concept. After evaluation with a series of neuropsychological tests, the postoperative cognitive decline was defined by a comparison of preoperative and postoperative cognitive function [22]. Until 2018, POCD was referred to as perioperative neurocognitive disorder (PND) to include all perioperative cognitive changes. PND was categorized into five groups based on the time of onset: Pre-existing cognitive changes, POD (occurring within 7 days after surgery or before discharge), delayed neurocognitive recovery (DNR, occurring from the end of surgery to 30 days after surgery), postoperative neurocognitive deficits (occurring from 30 days to 12 months after surgery), and cognitive deficits occurring after 12 months after surgery [7, 16].

Over the past decade, researchers have conducted numerous studies on the pathogenesis of POCD. Before discussing the mechanisms of postoperative cognitive dysfunction, it is important to identify the underlying causes. The term ‘underlying causes’ refers to the underlying factors or conditions that contribute to the development of POCD. For example, factors such as neuronal loss or excitation-inhibition imbalance are considered to be potential causes of POCD. In the central nervous system, neurons are the basic units that perform important functions such as information transmission, processing, and storage. Loss of neurons directly disrupts the integrity and function of neural circuits, resulting in abnormal transmission and processing of neural signals, leading to cognitive and memory loss, and thus causing cognitive dysfunction [23]. In addition, neuronal loss also interferes with the synthesis, release, and metabolism of neurotransmitters. Loss of cholinergic neurons leads to a decrease in acetylcholine synthesis affecting the inter-synaptic signaling and cognitive function [24]. Excitation-inhibition imbalance is a situation in which the balance between neural excitatory and inhibitory processes in the brain is disrupted, compromising normal brain function. For example, a fine balance is maintained between the excitatory neurotransmitter (glutamate) and the inhibitory neurotransmitter (gamma-aminobutyric acid, GABA) to maintain normal brain function [25]. Excitation-inhibition imbalance affects the activity of neuronal circuits, leading to the dysfunction of neural circuits ultimately damaging the neurons [26]. Inflammatory factors produced by the inflammatory response triggered by surgical trauma can not only damage neurons, but can also affect neural signaling by modulating the neurotransmitter system and disrupting the balance between excitation and inhibition, thereby promoting the development of POCD [27, 28]. Surgery and anesthesia can inhibit mitochondrial function and enhance oxidative stress, which can ultimately lead to impaired neuronal function, abnormal synaptic transmission, neurotransmitter imbalance, and even neuronal death, resulting in cognitive dysfunction [29]. In recent years oxidative stress, autophagy disorders, impaired synaptic function, and neuroinflammation are possibly involved in the development of POCD. Next, we will analyze and summarize these four mechanisms for a better understanding of the occurrence of POCD.

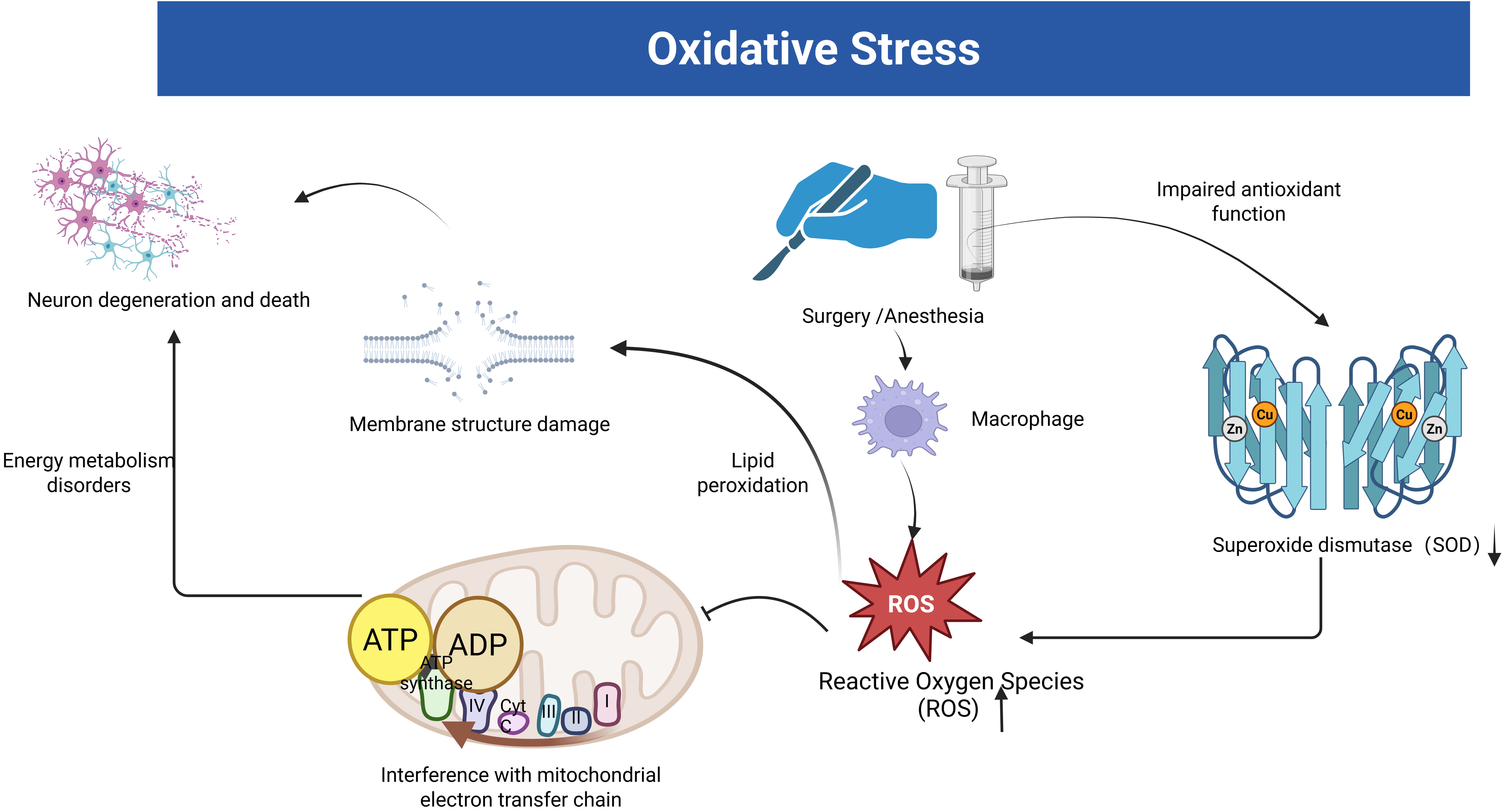

In an animal experiment using a mouse model of POCD established by tibial fracture surgery, researchers observed significant oxidative stress damage in the hippocampus of POCD mice, suggesting that mitochondrial oxidative stress may contribute to postoperative cognitive dysfunction [30]. Initially, oxidative stress is promoted by phagocytosis, which produces large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in response to infectious injury [31]. ROS/RNS promotes inflammation through lipid peroxidation in the center, causing damage to membrane structure (Fig. 1). These activities also interfere with electron transfer in mitochondria and inhibit neuronal energy metabolism [31, 32, 33] (Fig. 1). In addition, oxidative stress can also impair mitochondrial function by inducing structural changes [32]. This may be due to excess ROS disrupting the redox balance within the cell [34]. Excess ROS attack the mitochondria, leading to a decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential and the release of apoptosis-associated factors such as cytochrome C. The mitochondrial membrane potential decreases with the release of cytochrome C. Cytochrome C binds to apoptosis-activating factor-1 (Apaf-1), which activates the caspase cascade and ultimately leads to neuronal apoptosis [34, 35].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The link between oxidative stress and postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD). The figure illustrates the oxidative stress hypothesis of POCD induced by surgery and anesthesia. Stress facilitates the production of large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by phagocytic cells. Subsequently, these ROS impair mitochondrial function, disrupt membrane structures, and hasten neuronal degradation and death. Stress also exacerbates the body’s impaired antioxidant defense, resulting in reduced superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. The figure was created with https://www.biorender.com.

Oxidative stress leads to neuronal and synaptic death, which accelerates cognitive deterioration [33]. Netto et al. [36] examined the expression of oxidative damage and antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase-SOD and catalase-CAT) in the hippocampus by detecting ROS/RNS in POCD induced by tibial fracture surgery in rats. The results showed that rats developed cognitive decline associated with central oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Surgical trauma damaged the antioxidant function leading to elevated ROS/RNS, and these reactive substances caused oxidative damage leading to mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction, which affected neuronal energy metabolism and led to neuronal deformation and necrosis, triggering altered cognitive function (Fig. 1).

Sirtuin3 (SIRT3) is a class III histone deacetylase (HDAC) that is highly expressed in the brain [37]. SIRT3 regulates the mitochondrial function, and it also plays a role in extending the human lifespan [38]. Anesthesia and surgery down-regulates SIRT3 in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in aging mice, promoting oxidative stress, which further leads to microglial activation and hippocampal neuroinflammation, thereby decreasing postoperative cognitive function in aged rats [39]. Oxidative stress from anesthesia and surgery causes damage to lipids and proteins [36, 40], and both antioxidant endogenous defenses and mitochondrial respiratory function are disrupted [36, 40, 41]. It also leads to memory impairment caused by reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels [36, 41].

A study has shown that up to 60% of sepsis survivors exhibit permanent cognitive deficits [42]. Sepsis induces the production of ROS/RNS, which triggers lipid peroxidation in the cerebral vasculature and brain parenchyma [32, 42]. The lipid peroxidation chain reaction further generates free radicals in the brain, which contribute to localized inflammation and promote neuronal energy depletion [43]. The oxidative metabolism of the brain is damaged, and this leads to brain dysfunction, which causes cognitive changes. Both calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (p-CaMKII-Thr-286) and cAMP response element-binding protein (p-CREB-Ser-133) are significant mediators in regulating synaptic long-term potentiation (LTP) in the hippocampus, which is the physiological basis for memory formation [44, 45]. Song et al. [33] found that mice anesthetized by isoflurane for six hours developed cognitive deficits within 3 days, and the expression levels of SOD, P-CaMKII, P-CREB, and BDNF in the hippocampal region were downregulated. These findings further emphasize the close link between oxidative stress and POCD.

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) are a class of glutamate receptors that play a key role in learning and memory processe [46]. NR2B is one of the subunits of NMDAR, and it has been shown that the downregulation of its phosphorylation level is relative to impaired spatial learning in rats [47]. Excessive ROS can oxidatively modify NR2B, altering its structure and function, and leading to overactivation or abnormal function of NR2B [30]. Abnormal activation of NR2B triggers intracellular calcium overload and activation of reactive oxygen species-producing enzymes, leading to a further increase in ROS, forming a vicious cycle between oxidative stress and NR2B abnormalities and exacerbating neuronal damage [48]. Isoflurane is a common inhalation anesthetic, and it has been demonstrated that it impairs the stability of the NR2B/CREB pathway through oxidative stress in mice, which leads to cognitive dysfunction [49]. In addition, aggregation of the neuronal microtubule-associated protein Tau is associated with neurodegenerative diseases [50]. It has been shown that oxidative stress possibly plays a driving role in the hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau proteins [51].

Developing the nervous system is crucial for the normal function and maintenance of the brain. Autophagy not only plays an important role in neurodevelopment in neuronal precursors but also regulates axon growth and synapse formation [52]. Ka et al. [53] found that autophagy was significantly activated, and progenitor cell proliferation was inhibited in the mouse brain after selective knockdown of the MTOR gene in animal experiments, which led to a decrease in the number of interneurons in the cerebral cortex. This suggests that autophagy has a key role in regulating neuronal development. Ribas et al. [54] found from animal experiments that inhibition of autophagy with an autophagy inhibitor results in axon regeneration, promoting long-term stabilization of axons and enhancing axon sprouting. In Drosophila, loss of neuronal autophagy leads to reduced synapse formation [55]. This suggests that autophagy acts as a positive regulator of development at the synaptic level. Autophagy is a central molecular pathway for maintaining cellular and organismal homeostasis and is critical for maintaining post-mitotic neuronal homeostasis [56]. In the context of neurodegenerative diseases, a study has shown that induction of autophagy is a neuroprotective response [57].

Sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1)/p62 is an autophagy receptor protein for selective autophagy that is causally associated with the development of several neurodegenerative diseases [58]. Impaired autophagy leads to toxic accumulation of damaged proteins and organelles as well as autophagy-specific substrates such as SQSTM1/p62 in mammals, which are inextricably linked to physiology and disease [59]. Defects in autophagic activity and loss of basal autophagy levels lead to neurodegeneration [60].

Autophagy is a major intracellular pathway for the degradation and recycling of long-lived proteins and organelles [61]. Damaged organelles, long-lived or abnormal proteins, and redundant or aged cytoplasmic fractions are partially eliminated by the autophagy-lysosome system, protecting cellular function and tissue homeostasis [62, 63]. Autophagy disorders cause abnormal proteins such as

Defective autophagy is thought to be associated with the development of aging and age-related neurodegeneration due to the decline in autophagic capacity and the aggregation of abnormal and dysfunctional molecules, organelles, and proteins in aging tissues [67]. Autophagy disorders lead to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria in neurons, and the energy metabolism of these damaged mitochondria is impaired, leading to a decrease in the production of ATP and an insufficient supply of energy to neurons [52]. These damaged mitochondria also produce excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), which trigger oxidative stress, further damaging the cells, affecting neuronal function, and contributing to cognitive impairment [29]. Inflammation in the aging brain is thought to be associated with activation of the NF-

Wang et al. [82] constructed an animal model of POCD and found that oxidative stress and neuroinflammation were significantly activated and autophagy in the hippocampus was reduced after abdominal surgery in aged mice. The cognitive ability of the mice was improved after pretreatment with electroacupuncture. Detection of superoxide dismutase (SOD), reactive oxygen species (ROS), number of hippocampal microglia, and autophagy markers showed oxidative damage, autophagy dysfunction, and reduced neuroinflammation. Increased oxidative stress in the hippocampus following anesthesia and surgery contributes to microglial activation, leading to neuroinflammation in turn, microglia-mediated neuroinflammation exacerbates oxidative stress in the brain [39]. Under normal conditions, defective proteins and organelles are cleared through the autophagy pathway. However, surgical intervention disrupts hippocampal autophagy, impairing cellular waste clearance and increasing oxidative damage [83]. Zhang et al. [84] found that dexmedetomidine promotes the degradation of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles via the autophagy-ubiquitin pathway, which reduces the inflammatory response in the hippocampus and improves cognitive impairment in mice. Thus the role of autophagy in POD/POCD may be interconnected with neuroinflammation and oxidative stress.

A study has shown that synaptic plasticity is a key molecular mechanism for learning and memory [85]. The total number of dendritic crossings within the range of 70 to 130 µm is significantly reduced in aged rats following anesthesia and surgical induction [86, 87]. An animal study demonstrated that exposure to high concentrations of sevoflurane resulted in a significant decrease in the expression level of synaptotagmin 1 (Syt1) in the rat hippocampus, which impeded the release of presynaptic neurotransmitters and reduced the efficiency of synaptic transmission [88]. In addition, total dendritic length and spines were also reduced after anesthesia and surgery, which may be related to impaired synaptic plasticity in the CA1 region of rat hippocampus after anesthesia and surgery [41].

BDNF plays an important role in the development, maintenance, and function of the vertebrate nervous system, regulating the expression of proteins (neurotransmitters and ion channels) that are essential for normal neuronal function [89]. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is one of the most important neurotrophic factors in the mammalian brain and is closely associated with the control of neuronal and glial cell differentiation, neuroprotection, and the regulation of synaptic transmission and plasticity, functions that are critical for cognition and memory [90, 91, 92]. The binding of BDNF to TrkB receptors stimulates neuronal differentiation and dendritic differentiation in the hippocampal subgranular zone, and BDNF deficiency inhibits dendritic branching and disrupts synaptic plasticity [93, 94]. The function of BDNF in regulating synaptic plasticity is dependent on the synergistic effect of NO [95]. However, the specific relationship between NO and the neurotrophic factors involved in its regulation is unclear. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) regulates hippocampal synaptic transmission and plasticity [96, 97].

EP3, one of the receptor subtypes of PDE2, is highly expressed in the brain and has the highest affinity for PGE2 [98]. The PGE2- EP3 signaling pathway was shown to be involved in the development of POCD after cesarean section in aged mice [97]. CREB, BDNF, and activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein (Arc) are involved in the regulation of synaptic plasticity [99, 100]. EP3 induces a decrease in the intracellular levels of calcium and cAMP by inhibiting Ras/MAPK of the PKA pathway, which down-regulates the phosphorylation levels of CREB and its downstream products, Arc and BDNF, and thus inhibits altered synaptic plasticity [97]. Therefore, EP3 is expected to be a key breakthrough point for the treatment of POCD. Impaired synaptic function, which affects learning and memory functions, may be one of the mechanisms leading to POCD.

POCD is the result of a combination of factors. Many animal studies have shown an increase in inflammatory markers in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) even after aseptic surgery, suggesting that inflammation in the central nervous system may be one of the pathogenetic mechanisms for postoperative cognitive changes [2, 101, 102].

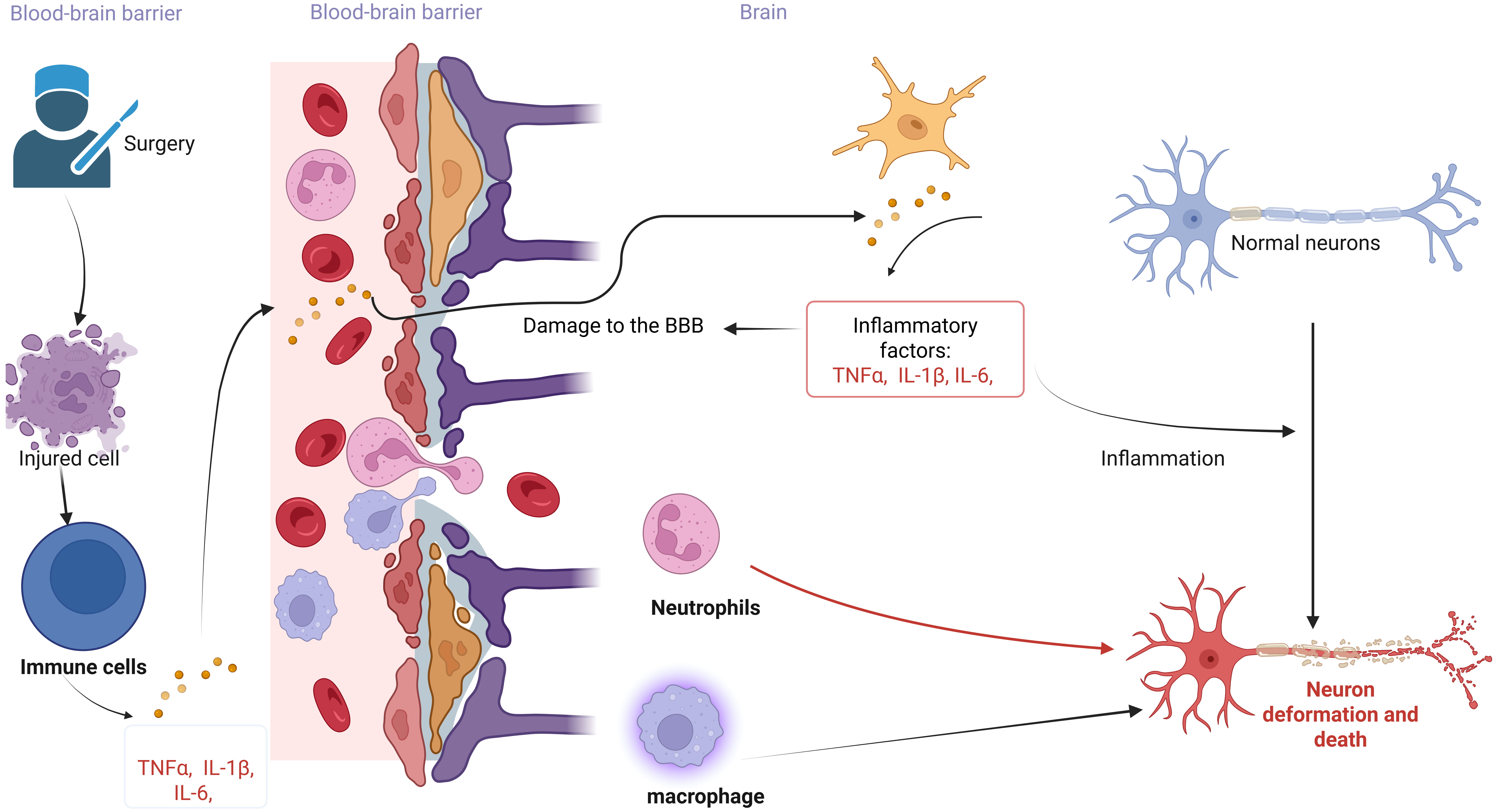

Neuroinflammation is an inflammatory response within the brain or spinal cord [103]. Surgical trauma can lead to massive immune cell infiltration, inflammatory cytokine expression, and glial cell activation, resulting in a neurotoxic response to the central nervous system [2, 104, 105] (Fig. 2). Surgery induces tissue damage and inflammatory processes, triggering the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The link between neuroinflammation and POCD. The figure illustrates the neuroinflammatory hypothesis of POCD induced by surgery and anesthesia. Peripheral immune activation leads to the production of numerous inflammatory factors, which compromise the integrity of the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB). Inflammatory factors entering the brain stimulate immune cells to secrete additional inflammatory factors, thereby initiating an inflammatory response. These inflammatory factors, along with peripheral immune cells traversing the blood-brain barrier, result in the deformation and death of normal neurons. The figure was created with https://www.biorender.com.

Although the presence of the blood-brain barrier limits the entry of inflammatory factors into the CNS, peripheral inflammation can compromise the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, allowing blood cytokines to directly affect the brain and trigger neuroinflammation [107] (Fig. 2). During surgery, the inflammatory response triggered by surgery and anesthesia promotes increased expression of inflammatory factors in plasma, impairing the structure and function of the intestinal barrier [108]. Inflammatory factors can enter the circulation through the damaged intestinal barrier [109]. Osburg et al. [110] found that TNF-

Peripheral surgery induces an innate immune response, which triggers an inflammatory process in the hippocampus mediated by the cytokine interleukin-1

The construction of animal models is indispensable for studying the pathogenesis of POCD and exploring therapeutic approaches. The current construction of animal models of POCD is based on different mechanisms of surgical and anesthetic induced POCD. The following summarizes the construction of POCD animal models (Table 1, Ref. [134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139]). The construction of animal models by surgery is based on the induction of POCD by the inflammatory response caused by surgical trauma [140, 141, 142]. In recent years, the inflammatory response has been recognized as the key factor in the development of POCD. The surgical construction of an animal model of POCD enables the analysis of the relationship between factors such as the extent and duration of surgical trauma and the occurrence of POCD. It also allows for the comparison of differences in POCD induced by general anesthesia. Surgeries known to induce POCD in mice include orthopedic procedures [140], partial hepatectomy [141], carotid artery exposure [142], and other surgical interventions. Among them, the tibial fracture mouse model is the most common POCD model, which may be related to the high incidence of POCD in orthopedic-related surgeries [1]. Although different types of surgery can induce POCD in animals, the extent and specific aspects of cognitive function are different. Anesthesia treatment allows the establishment of an animal model of POCD, which is induced by anesthetic drugs mainly by acting on N-methyl- D-aspartate (NMDA) and

| Laboratory animals | Intervention methods | Tests | Biomarkers | Behavioural disorders | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| 13–18 month-old male rats [134] | Exposure to 3% sevoflurane | MWM, EPM, OFT | Number of microglia in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, expression of TNF- | Decreases in time and number of entries into the platform quadrant versus the central region and anxiety behaviors | Fast induction and awakening of anesthesia, suitable for prolonged anesthesia, low respiratory tract irritation | High equipment requirements (special evaporation tanks required), high cost |

| 20-month-old male rats [135] | Exposure to 3% Isoflurane | MWM | Expression of expression of Hypoxia-inducible factor‑1 | Prolonged escape latency and prolonged latency to enter the target area | Easy to adjust the depth of anesthesia, good stability, low cost | Cardiovascular system depression (hypotension, decreased heart rate) |

| 20-month-old male rats [136] | Tail vein injection of Propofol (30 mg/kg) | MWM | Expression of GSK-3 | Prolonged latency and shortened target quadrant retention time | Easy to operate and highly reproducible | Poor controllability |

| 18-month-old mice [137] | Partial hepatectomy | MWM | Expression of IL-1 | the residence time stayed in the target quadrant and number of the platform crossing time was significantly reduced | Highly controllable (adjustable excision ratio) | High mortality rate and high operational requirements |

| 16-month-old mice [138] | Fracture of the tibia under isoflurane anesthesia (3% isoflurane for induction and 1.5% isoflurane for maintenance) | OFT, FCTs | Expression levels of BDNF, proBDNF, TrkB, p-TrkB, p75NTR, and Synapse Proteins | Hippocampus-dependent memory loss | Simulation of clinical fracture pathology allows study of postoperative cognitive and inflammatory responses in conjunction with anesthesia | Difficult surgery and complex postoperative pain manage |

| 8-week-old male mice [139] | Right carotid artery exposure under 1.8–2% isoflurane anesthesia | Barnes Maze and Fcts | Expression levels of Neuroligin 1 | Increased time required to identify target boxes | Motor function unaffected, exploring the link between changes in vascular function or hemodynamics and cognition | Possible nerve and tissue damage, technically demanding |

Summarize the current construction of POCD animal models from the selection of experimental animals, intervention methods, experimental projects, biomarkers, etc. MWM, Morris water maze; EPM, elevated plus maze; OFT, open field test; GSK-3

How to determine the occurrence of POCD in experimental animals is mainly measured by analyzing animal behavioral science. Behavioral experiments are important experimental methods in animal research. Morris water maze experiment (MWN) can be used to test spatial learning, memory, and cognitive flexibility in mice by observing the path trajectory, latency, and the number of times the animal traverses the platform [144]. Elevated plus maze (EPM) and open field test (OFT) can be used to measure anxiety-like behavior in mice [145]. Fear Conditioning Tests (FCTs) are primarily used to assess learning and memory in animals by observing the percentage of time spent in freezing position, latency of fear response and other indicators [146]. Barnes maze can be used to test spatial navigation and long-term memory skills by recording the latency of the animal to find a target hiding place, the number of errors, path efficiency and other metrics [147]. New Object Recognition Test (NORT) can be used to assess the learning and memory abilities of animals by recording the time they spend searching for familiar and new objects [148]. Pathological biopsy of the brain tissue of the experimental subjects and analysis of various biomarkers in the circulatory system are more reliable methods to verify the success of animal model establishment.

Differences between animals and humans in clinical manifestations and pathophysiologic processes may affect the translation of results from animal models to clinical applications. Individual differences among animals, differences in experimental environments, and differences in experimental techniques all affect model stability and reproducibility. Although animal models play a crucial role in POCD research, studies have been limited to rats and mice with no studies reported in nonhuman primates [149, 150, 151].

Clinically, postoperative cognitive dysfunction occurs in elderly patients undergoing surgical procedures requiring anesthesia, especially in orthopedic surgeries. POCD is diagnosed in the clinic and relies on cognitive functioning test scales. The Mental State Examination (MMSE) is the most widely used cognitive screening tool. It is less time-consuming and easier to administer but has limitations. The MMSE is less sensitive to detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Additionally, results may be influenced by a person’s literacy level, potentially leading to misclassification [152]. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale (MoCA) is more specific for characterizing lesions in patients with mild cognitive impairments but is susceptible to cultural and educational influences [153]. The Wechsler Intelligence Scale is a widely used tool for assessing intelligence, which includes various aspects such as verbal skills and can reflect a person’s cognitive ability more comprehensively but the test items are time-consuming and affected by the level of education [154]. Denbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III is a comprehensive cognitive functioning assessment tool that evaluates impairments in a variety of cognitive domains, including attention, memory, language, etc [155]. It is superior to other screening tests for mild cognitive impairment, but the reliability of the results depends on the number of items tested and is not a complete substitute for more specialized neuropsychological tests [156].

In addition, in recent years, it has been widely recognized that neuroinflammation is associated with postoperative cognitive dysfunction, and the inflammatory factors listed above, such as IL, C-reactive protein (CRP), TNF-alpha, and S100

| Age | Name of surgery | Anesthesia method | Cognitive measures | Biomarkers |

| 60–90 years [158] | Cardiac surgery | Intravenous-inhalation combined anesthesia | The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | / |

| Unilateral total hip replacement or total knee replacement | Combined spinal-epidural anesthesia (CSEA) with sedatives | The neuropsychological test battery: MoCA, Stroop color-word test (SCWT), Digit span test, Digit symbol test, Associative learning and memory test | / | |

| Non-cardiac surgery | Intravenous general anesthesia | The mini-mental state examination (MMSE), the neuropsychological test battery: Chinese auditory learning test (CALT), the digit span test (DST), the judgment of line orientation test (JLOT), and language fluency test (VFT) | the plasma microRNA-221-3p level | |

| Hip fracture surgery | general or subarachnoid (spinal) anesthesia | CAM, MMSE | / | |

| radical surgery for gastrointestinal tumor | Intravenous-inhalation combined anesthesia | MMSE | S100calcium-binding protein beta (S100 | |

| Thoracic surgery | Intravenous-inhalation combined anesthesia | The neuropsychological test battery | / |

Summarize current research on POCD clinical trials from different perspectives, including patient age, anesthesia method, surgical approach, cognitive assessment methods, and blood markers. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

At present, regarding the construction of animal models of POCD, most of them choose rodents as experimental subjects. The construction of animal models relies on surgical and anesthesia treatments, and most existing studies have focused on anesthesia treatments alone [134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139], with some opting for a combination of surgery and anesthesia. However, the independent contribution of surgery and anesthesia to postoperative cognitive function is not clear. It has been suggested that it is surgical trauma, not anesthesia, that causes POCD [164]. Whether anesthesia alone leads to postoperative cognitive dysfunction is controversial [10].

In clinical trials, anesthesia and surgery are often combined, so models for future animal studies should be better designed to reflect clinical settings. The definitive clinical diagnosis of POCD relies on neurocognitive test scales, while basic research determines the occurrence of POCD in experimental animals through behavioral tests. However, the cognitive evaluation scales for animals and humans are not completely standardized and may be influenced by subjective factors of the researchers. In clinical studies, it is the systematic assessment of the patient that determines POCD, which is an individual-based assessment process [158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163]. The assessment of cognitive function in surgical patients covers the entire perioperative period. In contrast, in current animal studies, experimental animals are often evaluated only once after anesthesia and surgery, which is detrimental to the detection of POCD in experimental animals [134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139]. Additionally, differences in assessment methods between basic and clinical research can hinder POCD detection. Significant variability in the type, number, and timing of tests further complicates the understanding of POCD. Although most of the clinical and basic studies rely on detecting inflammatory factors in the blood to predict POCD, its specificity remains low [165, 166].

In addition to this, blood, cerebrospinal fluid, hippocampus, and other tissues from animals can be studied. While brain tissue is difficult to obtain, inflammation-related biomarkers are mostly analyzed based on patient blood specimens. In the future, if there are neuroinflammation-specific markers capable of labeling in vivo brain tissue, it will have a profound impact on the development of POCD research. Therefore, we need more clinically relevant animal experiments to provide more valuable evidence for the pathogenesis of POCD. Through animal experiments, we can provide strong support for clinical research and faster solutions for the prevention and treatment of POCD, so that POCD patients can be better managed.

Although the major risk factors for POCD are recognized, there is no clinical or standardized method for identifying high-risk patients. Patients who developed postoperative cognitive dysfunction had no significant changes in imaging and relatively atypical clinical presentations. Therefore, extensive perioperative screening is necessary and desirable to identify individuals at risk for POCD. Currently, there is no treatment for POCD and no standardized means of routine assessment. There is a clear need for a treatment or medication that can prevent or treat POCD, especially in high-risk populations. Cognitive function involves complex mechanisms and factors, and it is difficult to improve patients’ cognitive function with medication alone.

The underlying pathogenesis of POCD is unclear due to conflicting results from different studies and controversial evidence. In addition, effective postoperative follow-up is lacking, and the incidence of POCD in China is unknown. Although many drugs have been proposed to improve POCD in animal studies [108, 167], they have always been limited in clinical application. Future research should also focus more on finding risk factors outside of surgery that would be more beneficial to patients at risk for postoperative cognitive impairment. Although many mechanisms may contribute to postoperative cognitive dysfunction, including apoptosis, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and autophagy, are involved in cognitive dysfunction induced by anesthetic drugs or surgery, the exact molecular mechanisms are unknown. Further studies on the mechanism, prevention, and treatment of POCD are needed in the future.

YL and QP did the literature search, prepared the figures, and drafted the paper. JL and LH assisted in collecting and organizing reference texts and provided advice on designing and plotting diagrams. HZ presented the paper conceptualization and design, writing, outline, and final approval of the published version of the article. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The images in the manuscript are original and were created using https://www.biorender.com.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.