1 Chair and Department of Neurology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, 60-355 Poznan, Poland

2 Laboratory of Neurobiology, Department of Neurology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, 60-355 Poznan, Poland

3 Department of Clinical Immunology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, 60-355 Poznan, Poland

4 Faculty of Health Care, Stanislaw Staszic University of Applied Sciences in Pila, 64-920 Pila, Poland

5 Department of Neurology, Specialistic Hospital in Pila, 64-920 Pila, Poland

Abstract

Aging is a multifaceted biological process characterized by numerous physiological and molecular alterations that profoundly impact health and susceptibility to disease. Among the genetic determinants influencing aging, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene cluster has emerged as a critical focus of research. This study explored the diverse roles of APOE in both normal and pathological aging, with particular emphasis on its involvement in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). We first examined the “physiological” aspects of aging, highlighting cellular and systemic adaptations that support organismal homeostasis. This was followed by an analysis of the pathophysiological deviations underlying neurodegenerative disorders, with AD as a key example. The role of APOE in normative aging was then discussed, including its contributions to lipid metabolism, synaptic plasticity, and neuroprotection—functions essential for maintaining both cerebral and systemic health. However, the pathological implications of APOE genetic variants, particularly the ε4 allele, were considered in relation to the increased risk of AD and other age-related diseases. Additionally, the APOE gene cluster, which includes adjacent regulatory and interactive genes, was examined for its potential to modulate APOE expression and function, thereby influencing the aging process. This synthesis underscores the pivotal role of the APOE gene cluster in elucidating the genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying aging and age-related diseases, providing a foundation for the development of targeted therapeutic interventions.

Keywords

- molecular factors

- APOE gene cluster

- neurodegeneration

- normal aging

The apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene plays a central role in lipid metabolism and has emerged as a critical factor in the study of both normal and pathological aging. Located on chromosome 19, the APOE gene produces three primary isoforms, APOE

Moreover, the APOE gene’s interactions with environmental factors, epigenetic modifications, and lifestyle choices underscore its complexity. Epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation at specific CpG islands within the APOE promoter, have been implicated in modifying the gene’s expression and potentially influencing aging outcomes. These findings highlight the dynamic interplay between genetic predispositions and external factors, contributing to the heterogeneity observed in aging and age-related diseases [4]. Emerging research aims to elucidate how APOE genetic variants and their associated biochemical pathways contribute to aging-related phenotypes, with the goal of informing precision medicine approaches. Investigations integrating genomic, proteomic, and metabolomics data are critical for understanding how APOE variants modulate cellular processes in both protective and deleterious ways [5]. These insights hold promise for developing targeted interventions that mitigate the negative consequences of APOE

In addition to its lipid-related functions, apoE also interacts with a network of genes that regulate inflammation, metabolism, and brain development. The genes RELB proto-oncogene, NF-κB subunit (RELB) and transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1), both involved in inflammation, play significant roles in maintaining immune homeostasis in the CNS. RelB, part of the alternative NF-

Aging is a natural biological process characterized by a progressive decline in physiological integrity at systemic, molecular, and cellular levels. This deterioration results from multiple interrelated mechanisms that gradually impair the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis. Rather than being attributed to a single factor, aging is a physiological process that arises from a complex interplay of environmental, genetic, and epigenetic elements that interact over time. Among the most widely studied contributors, instability in the aging genome plays a central role, serving as a foundation for several cellular dysfunctions associated with aging.

Genomic instability stems from various factors that damage intracellular structures, leading to mutations, chromosomal rearrangements, and other forms of genome deterioration. DNA replication errors, oxidative stress, spontaneous hydrolytic reactions, and exogenous insults such as radiation and toxins all contribute to the DNA damage observed in aging cells. As genetic mutations accumulate over time, cellular function deteriorates, affecting not only individual cells but also the overall integrity of tissues and organs [8, 9]. This decline in genomic stability is a critical driver of aging and age-related diseases. One notable consequence is the progressive shortening of telomeres, the protective nucleotide sequences at the ends of chromosomes. With each cell division, telomeres shorten, eventually triggering cellular senescence or apoptosis [10, 11, 12, 13]. While telomerase, an enzyme responsible for maintaining telomere length, is active in stem and germ cells, it is largely inactive in most somatic cells, leading to gradual telomere attrition over an organism’s lifespan. Telomere shortening has been linked to various age-related diseases, including pulmonary fibrosis, aplastic anemia, and dyskeratosis congenita [14, 15].

Beyond telomere attrition, genomic instability in aging also extends to nuclear DNA. Somatic mutations accumulate with age, significantly impacting cellular function in the esophageal epithelium of young individuals. Hundreds of mutations may be present per cell, increasing to over 2000 by middle age [16, 17]. This dramatic rise in mutations contributes to the decline in tissue functionality. Particularly in stem cells, the accumulation of DNA mutations impairs regenerative capacity. Stem cells are crucial in maintaining tissue homeostasis and repairing damage. Their dysfunction accelerates the aging process and takes part in a variety of age-related conditions [18, 19]. Despite this, somatic mutations are often tolerated, as the body prioritizes survival over complete genomic repair. This trade-off between survival and genomic integrity reflects a key physiological dilemma faced by aging organisms.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) also plays a crucial role in the aging process. Mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell, generate ATP but are also major sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage cellular components, including mtDNA. Unlike nuclear DNA, mtDNA lacks histone protection, making it more vulnerable to oxidative stress [20]. Additionally, the high replication rate of mtDNA leads to an accumulation of mutations as organisms age. This damage is compounded by inefficient mitochondrial repair mechanisms, ultimately compromising mtDNA integrity. As a result, mutations and deletions in mtDNA contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, accelerating cellular aging [20, 21, 22]. However, the direct causality between mtDNA mutations and aging remains uncertain. Recent findings suggest that replication errors, rather than oxidative stress, are the primary drivers of aging-related mtDNA mutations. This revelation underscores the need for further investigation into the mechanisms by which mtDNA mutations accumulate and contribute to aging and age-related diseases [20]. Animal models deficient in mtDNA polymerase exhibit accelerated aging and reduced lifespan, providing further evidence for the role of mtDNA in aging [22, 23, 24, 25].

In addition to genomic instability, aging is characterized by epigenetic alterations, which involve chemical modifications to DNA and histones that regulate gene expression. These modifications can be driven by both intrinsic factors, such as DNA replication errors and oxidative stress, and extrinsic influences, including environmental exposures. Key epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling, all of which can influence gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. One of the most prominent changes observed in aging is a global loss of DNA methylation, which affects various genes, including tumor suppressor genes and those involved in tissue regeneration [26, 27, 28]. While some DNA methylation modifications are reversible, others accumulate over time, contributing to cellular aging.

Loss of epigenetic control also affects histone modifications, which play a crucial role in aging. Post-translational modifications of histones, such as acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, govern gene expression. For example, aging cells exhibit increased histone acetylation and decreased h3k27me3 (trimethylation of histone h3 at lysine 27), both of which are linked to transcriptional changes that drive metabolic and homeostatic dysfunctions [29, 30]. The sirtuin (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog, SIRT) family of proteins, particularly SIRT1 and SIRT6, are key regulators of histone deacetylation. Notably, SIRT6 promotes genomic stability, enhances DNA repair, and extends lifespan in animal models, highlighting the role of sirtuins in aging [31, 32, 33, 34]. Additionally, chromatin remodeling proteins such as heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) play a role in aging. Research has shown that HP1 overexpression can extend both healthspan and lifespan, suggesting that targeting chromatin dynamics may provide therapeutic opportunities for anti-aging therapies [35, 36]. Another hallmark of aging is the loss of proteostasis, which refers to the failure of cellular mechanisms responsible for maintaining protein homeostasis. Within cells, proteins are continuously synthesized, folded, and degraded. However, with aging, the efficiency of protein quality control systems, including the unfolded protein response, autophagy, and proteasomal degradation, declines, leading to the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates. This dysfunction contributes to a range of age-associated diseases, particularly neurodegenerative disorders such as AD and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [37, 38, 39, 40].

Enhancing proteostasis by stimulating proteasomal activity or autophagy has been shown to extend lifespan in various model organisms. Moreover, restoring autophagic flux in aged mice has been found to improve tissue regeneration and extend lifespan [41, 42, 43, 44]. Cellular senescence is another defining feature of aging, characterized by cells that lose the ability to divide and undergo gene expression changes that impair tissue function. Senescence can be triggered by various factors, including telomere shortening, DNA damage, oxidative stress, and other environmental stressors. Over time, senescent cells accumulate in tissues and secrete pro-inflammatory molecules known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). These include cytokines, growth factors, and proteases that promote chronic inflammation and fibrosis while destabilizing tissue structures [45, 46, 47, 48]. The release of SASP can significantly destabilize neighboring cells, promote further senescence, and disturb tissue homeostasis, underscoring the pivotal role of cellular senescence in aging and its contribution to various age-related diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegeneration. Recent research suggests that eliminating senescent cells (senolysis) can improve healthspan and extend lifespan in animal models. Senolytic drugs such as dasatinib and quercetin have been shown to selectively remove senescent cells, delaying aging and mitigating age-related diseases in mice [49, 50]. These findings suggest that cellular senescence is not just a consequence of aging but also an active contributor to age-related dysfunction. Clinical trials investigating senolytic therapies are ongoing, with promising results suggesting they may alleviate symptoms of diseases such as osteoarthritis, kidney disease and atherosclerosis. Research on animal models and multiple clinical trials are currently investigating the potential therapeutic benefits in humans [51, 52].

As aging progresses, stem cell exhaustion becomes a significant limiting factor in tissue regeneration and repair. Stem cells are essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis, and their decline accelerates aging. Cellular reprogramming, which involves introducing specific factors to revert differentiated cells into a pluripotent stem cell-like state, has emerged as a potential strategy for tissue rejuvenation. This process can reverse epigenetic markers of aging, rejuvenating the foundational potential of aged tissues. In mouse models, transient reprogramming has been shown to restore tissue function and enhance regeneration in organs such as the pancreas, muscle and liver [53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67]. Aging is also associated with altered intercellular communication, particularly in the immune system. Immunosenescence, a decline in immune function, leads to increased susceptibility to infections, injuries and impaired tissue repair.

Moreover, chronic low-grade inflammation, known as inflammaging, has been linked to age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neurodegeneration. One key factor in altered intercellular communication is the disruption of the extracellular matrix (ECM). As individuals age, the ECM undergoes remodeling, with increased cross-linking of collagen fibers and the accumulation of advanced glycation end products. These alterations result in a stiffer ECM, which compromises tissue elasticity and function. For example, in the skin, ECM stiffening leads to decreased elasticity and the formation of wrinkles. In other tissues, such as the heart and arteries, ECM remodeling contributes to fibrosis, disrupting organ function. Interestingly, some studies suggest that targeting the ECM or modulating ECM stiffness could offer therapeutic benefits for aging and age-related diseases. For instance, inhibiting ECM stiffness in the brain may rejuvenate oligodendrocyte progenitors in aging mice, potentially offering new approaches for treating neurodegenerative diseases [68, 69, 70, 71, 72].

The concept of pro-aging blood-borne factors has also gained attention. Studies have shown that the blood of older individuals contains factors that promote aging, while the blood of younger individuals may have rejuvenating effects on aged tissues. For instance, heterochronic parabiosis, in which young and old mice share a circulatory system, has demonstrated that young blood can rejuvenate aged tissues and enhance regeneration. These findings suggest that circulating factors play a crucial role in intercellular communication and aging. Several molecules have been identified as potential pro-aging factors, including the chemokine C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)11 and the protein 2-microglobulin, both of which have been linked to neurodegeneration and impaired tissue repair [73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79]. Conversely, molecules such as growth differentiation factor (GDF)1, CCL3, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)2, found in the blood of young individuals, may exhibit rejuvenating effects and serve as potential therapeutic targets for extending healthspan and delaying aging [80, 81, 82, 83, 84].

ApoE plays a crucial role in normal aging, particularly in regulating lipid metabolism, maintaining synaptic plasticity, providing neuroprotection, and supporting the proper function of the cardiovascular and muscular systems [85]. Its wide range of functions extends beyond brain health, significantly contributing to overall systemic health and homeostasis [86].

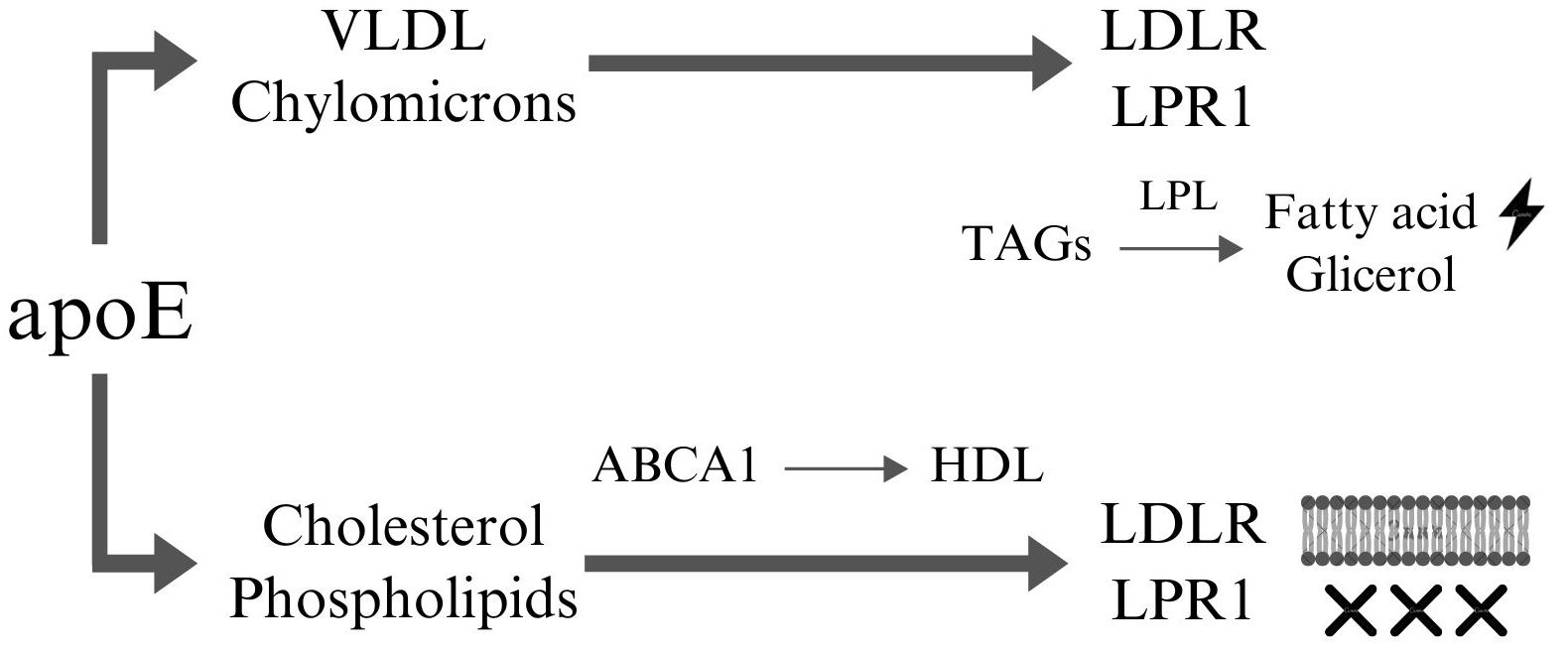

Under normal conditions in the CNS, APOE is primarily expressed in glial cells, with astrocytes serving as the main source and microglia contributing to a lesser extent. Astrocytes synthesize and secrete apoE into the intercellular space, facilitating the transport and redistribution of lipids to maintain lipid homeostasis and support neuronal protection and function [87]. Outside the CNS, the liver is the primary site of apoE synthesis, with additional, lower levels of production occurring in the kidneys, adipose tissue, adrenal glands, and other tissues [88]. ApoE binds to cholesterol and phospholipids to form lipoproteins (Fig. 1). This process is mediated by ATP-binding cassette (ABCA1), which promotes the transfer of free cholesterol and phospholipids (not bound to lipoproteins) to apoE, leading to the formation of spherical structures resembling high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles [89]. These lipoproteins are subsequently transported to neurons and peripheral tissues, where they are recognized by lipoprotein receptors such as the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and lowdensity lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) [90]. Additionally, apoE associates with lipoproteins such as chylomicrons and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), which transport triglycerides (TAGs). By binding to these lipoproteins, apoE stabilizes their structure and facilitates their recognition by receptors such as LDLR and LRP1, enabling their transport to vascular endothelial cells, the liver, skeletal muscle, and cardiac muscle. Upon reaching target cells, triglycerides are hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase (LPL) into glycerol and free fatty acids, which can then be utilized as an energy source [88, 91]. Maintaining lipid homeostasis is essential for preserving cell membrane integrity, facilitating neurotransmitter synthesis, and ensuring proper neuronal transmission.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. ApoE dependent lipoprotein transport. ApoE facilitates the transport of VLDL and chylomicrons through interactions with receptors such as LDLR and LRP1. At the end of this pathway, the transported TAGs are hydrolyzed by LPL into free fatty acids and glycerol, which can be utilized as energy sources by cells. Furthermore, apoE interacts with cholesterol and phospholipids, which are then transferred to ABCA1 to form nascent HDL particles. These HDL particles can subsequently interact with receptors such as LDLR and LRP1 to mediate lipid uptake or removal. Cholesterol and phospholipids can be incorporated into cellular membranes, contributing to membrane integrity and fluidity, or removed from the system to maintain lipid homeostasis and prevent lipid accumulation in tissues. This highlights apoE’s critical role in lipid metabolism, energy supply, and cellular lipid homeostasis. This figure was created using Canva (Canva Pty Ltd., Sydney, NSW, Australia, https://www.canva.com/). VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; LDLR, low-density lipoprotein receptor; LRP1, LDL receptor-related protein 1; TAGs, triglyceride; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; ABCA1, member 1 of human transporter sub-family ABCA; HDL, high-density lipoproteins; apoE, apolipoprotein E.

Beyond the CNS, efficient lipid transport is essential for maintaining optimal cardiovascular function, as it prevents lipid accumulation within blood vessels and the subsequent formation of atherosclerotic plaques [92]. ApoE also plays a crucial neuroprotective role in normative aging by modulating the inflammatory response through interactions with microglia, which are vital for defending against pathogens and neuronal injury. Research suggests that apoE is essential for the activation of microglia in response to amyloid plaques, as its absence weakens the microglial response while simultaneously increasing neuritic damage around these plaques [93]. Additionally, APOE

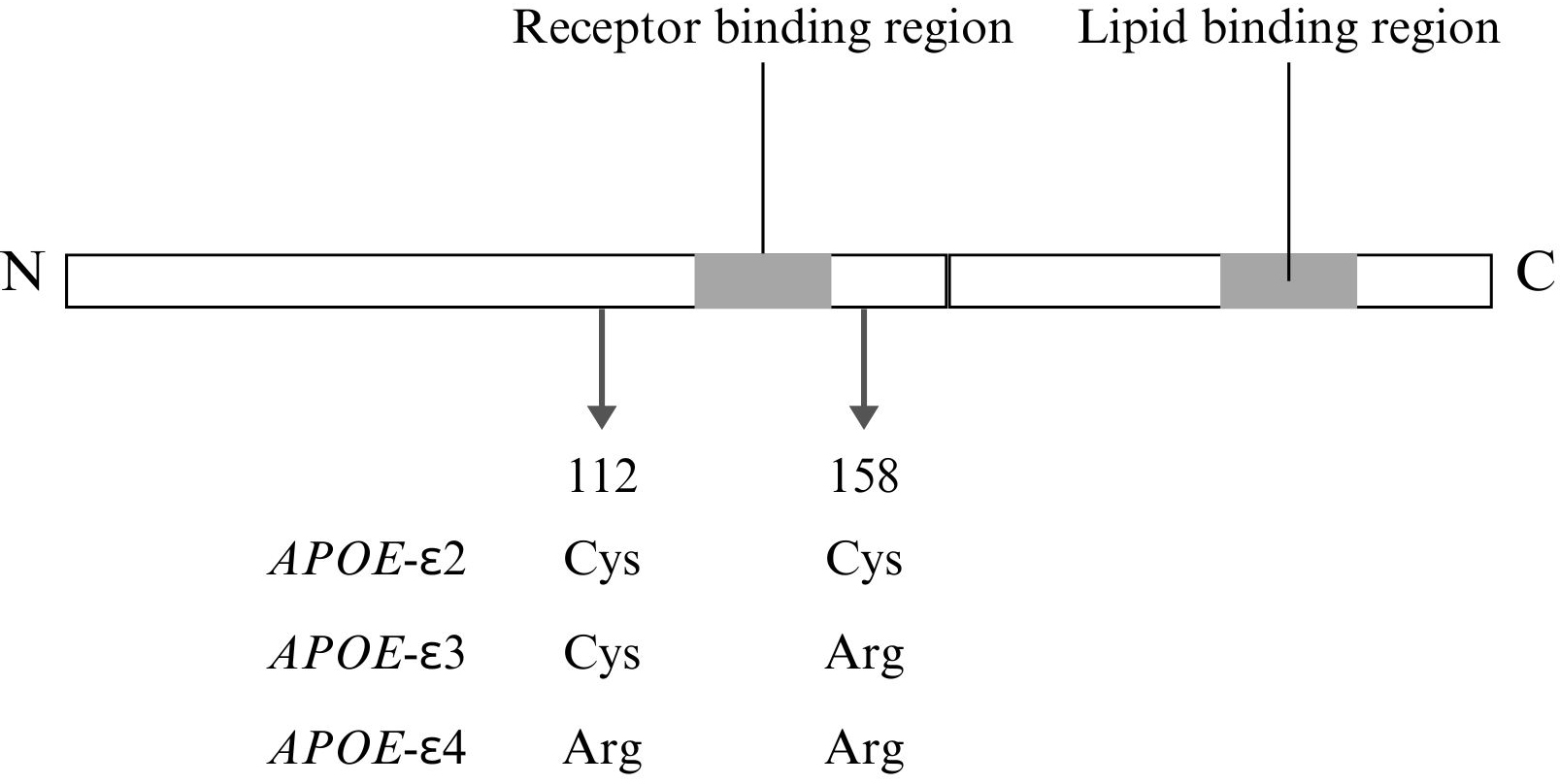

During aging, pathological processes can disrupt lipid homeostasis, neuronal function, and inflammatory regulation, with the apoE protein playing a critical role as both a protective factor and a contributor to risk in these processes. Notably, the APOE

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Structural and functional features of APOE with isoform-specific differences. This figure was created using Canva. Cys, cysteine; Arg, arginine; N, N-terminal domain; C, C-terminal domain.

Moreover, the increased hydrophobicity and reduced flexibility of APOE

APOE

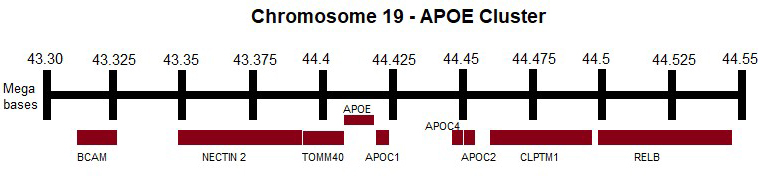

Genetic variants in the APOE cluster (Fig. 3) have been extensively studied to investigate their potential association with plasma lipid levels and the development of neurodegenerative diseases. However, there is still little information regarding their association with normal aging.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. APOE cluster. APOE, APOC1, APOC2, APOC4, TOMM40, BCAM, NECTIN2, CLPTM1, RELB genes. This figure was created using Microsoft Paint (v11, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). APOC, apolipoprotein C; TOMM40, translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40; BCAM, basal cell adhesion molecule; NECTIN2, nectin cell adhesion molecule 2; CLPTM1, cleft lip and palate transmembrane protein 1; RELB, RELB proto-oncogene, NF-

The APOE gene, located on chromosome 19q33, is part of a cluster of genes that includes APOC1, APOC4, and APOC2. Variants of the APOE gene are major genetic determinants of AD risk, with specific haplotypes defined by two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)—rs429358 (T/C, p.C112R) and rs7412 (C/T, p.R158C). These genetic variants lead to amino acid substitutions at positions 112 and 158, resulting in three alleles:

APOE and its gene cluster are critical modulators of immune and inflammatory pathways, playing a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD. APOE isoforms, particularly APOE

The APOE cluster genes, particularly APOE and its adjacent neighbor TOMM40, are essential regulators of metabolic processes, with significant implications for aging and neurodegenerative diseases. TOMM40 encodes a mitochondrial transport protein, and variants within this gene, especially intronic poly-T tracts (TOMM 523), have been associated with AD [120]. These two genes, located on chromosome 19q13.3, exhibit independent and additive associations with dementia risk, particularly in Caucasian and African-American populations [121]. Genetic variations in APOE and TOMM40 influence multiple aspects of brain aging, including cognitive decline, cortical atrophy, myelin loss, and cerebral microbleeds, which often precede clinical manifestations of AD [122]. Beyond their roles in lipid metabolism, APOE and TOMM40 also influence other metabolic processes. For example, the APOE

Research into the APOE gene cluster has revealed that genes such as basal cell adhesion molecule (BCAM) and nectin cell adhesion molecule 2 (NECTIN2), located in close proximity to APOE, play significant roles in AD and other neurodegenerative conditions [127, 128]. These genes are believed to influence the risk of LOAD through their interaction with APOE alleles, particularly APOE

Similarly, NECTIN2, another adhesion molecule, is associated with synaptic stability, and its specific genetic variants may contribute to cognitive decline, particularly in APOE

The cleft lip and palate transmembrane protein 1 (CLPTM1) gene, located within the APOE gene cluster on chromosome 19q13.32, has gained attention for its potential role in AD and metabolic disorders. While CLPTM1 is not directly involved in lipid metabolism like APOE, emerging evidence suggests that CLPTM1 variants influence lipid profiles and cardiometabolic traits, both of which are critical in AD pathogenesis. Specific CLPTM1 genetic variants, such as rs3786505 and rs11672748, have been independently linked to alterations in LDL and HDL cholesterol levels [137]. These findings indicate that CLPTM1 contributes to the regulation of lipid metabolism in both the brain and peripheral tissues, processes that are central to the development and progression of AD. Moreover, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) between CLPTM1, APOE, and nearby genes like APOC1, suggesting that genetic interactions within this region amplify the impact of the APOE locus on lipid regulation and AD risk [138]. Within the context of AD, the CLPTM1 locus has emerged as a promising candidate for further research due to its association with cardiometabolic pathways. Its role in lipid transport and interactions with apolipoproteins, such as apoE, suggests its involvement in neurodegenerative mechanisms. The localization of CLPTM1 within the APOE cluster points to a shared regulatory network, where genetic and epigenetic variations influence CLPTM1 expression and function, further reinforcing its significance in AD pathophysiology [139].

The APOE gene cluster, including APOE, TOMM40, long, BCAM, NECTIN2, and CLPTM1, plays a significant role in aging and age-related diseases, particularly AD. The APOE

Writing of the manuscript and designing, and drawing the figures - MH, DP, JP, IKŁ, APP, MW; Editing and language correction, collecting and sorting references, literature reviewing - JFW, OS, UG; Conception or design of the work, final manuscript review – WK and JD. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Jolanta Dorszewska is serving as one of the Editorial Board members and Guest editors of this journal. We declare that Jolanta Dorszewska had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Gernot Riedel.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.