1 Laboratory of Repair Enzymes, Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia

2 Department of Natural Sciences, Novosibirsk State University, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia

3 Laboratory of Molecular Genetics and Biochemistry, Mental Health Research Institute, Tomsk National Research Medical Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 634014 Tomsk, Russia

4 Department of Psychiatry, Addiction Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Siberian State Medical University, 634050 Tomsk, Russia

Abstract

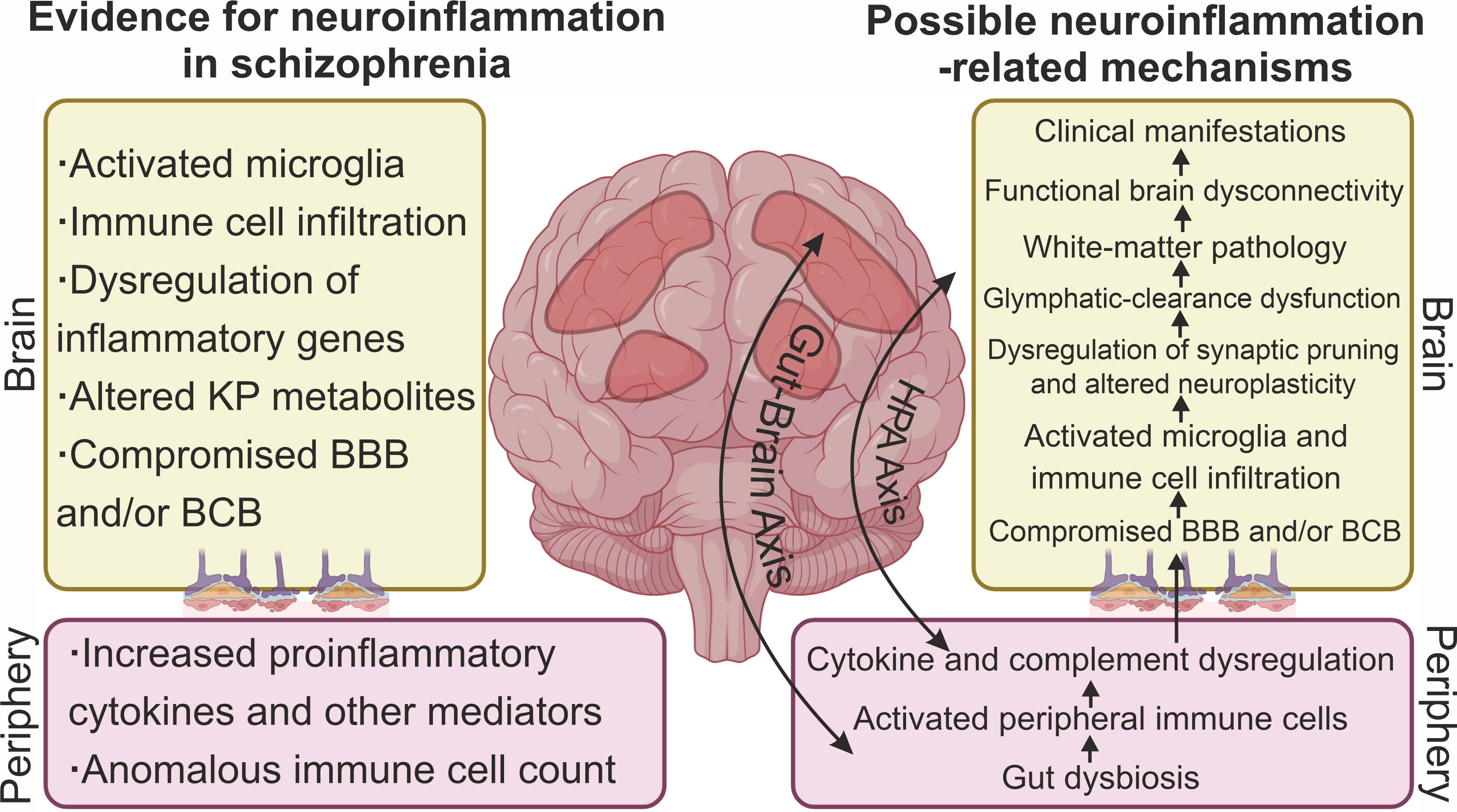

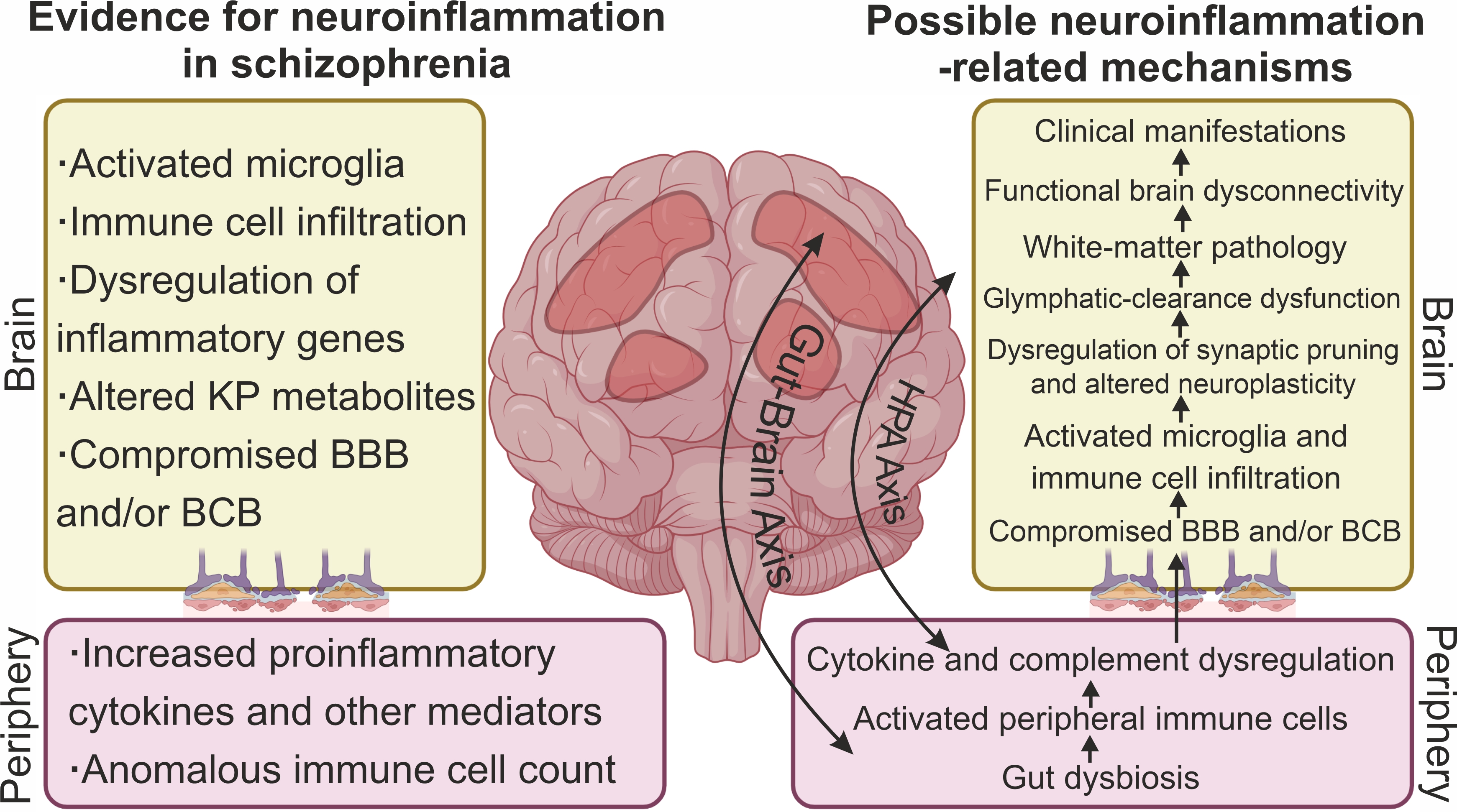

Neuroinflammation, meaning an inflammatory process primarily occurring within the central nervous system (CNS), is thought to be associated with the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia (SC), although existing evidence is sometimes contradictory. This review critically summarizes the existing data on neuroinflammation and possible neuroinflammatory mechanisms in the pathogenesis of SC. Despite heterogeneity and inconsistency, the existing evidence indicates dysregulation of inflammatory genes and infiltration of the CNS parenchyma by immune cells, disturbances in the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier and blood–brain barrier, and activation of microglia and astroglia. Widely documented increases in levels of peripheral inflammatory biomarkers also reflect activation of inflammatory processes in the CNS. Nevertheless, patients differ in the degree of activation of neuroinflammatory processes, indicating the existence of immunophenotypes of SC with and without neuroinflammation. Neuroinflammation may be associated with dysregulation of synaptic pruning, impaired neuroplasticity, glymphatic-clearance dysfunction, and white-matter pathology, all of which may ultimately lead to functional brain dysconnectivity and disease manifestation. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and gut–brain axis and disturbances in the kynurenine pathway are the main molecular mechanisms linking peripheral and central inflammation. However, neuroinflammation may not only be associated with negative consequences but also indicate activation of adaptive and reparative processes. Thus, neuroinflammation may be entwined in the pathogenetic mechanisms of SC; therefore, anti-inflammatory therapeutic strategies may improve patient care.

Keywords

- schizophrenia

- neuroinflammation

- gut-brain axis

- microglia

- blood–brain barrier disruption

- kynurenine pathway

- hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

- treatment

The term neuroinflammation is known to refer to inflammatory processes within the central nervous system (CNS) [1]. Historically, neuroinflammation has been used to characterize processes following CNS injury or infection, but over time, the concept has broadened, and neuroinflammatory mechanisms have become an integral part of the pathogenesis of a wide range of diseases including psychiatric disorders [2, 3]. Neuroinflammation is a special case of inflammation, but these concepts are often confused and conflated in the literature (e.g., peripheral inflammation and neuroinflammation). Neuroinflammation is characterized by the involvement of multiple immune cells (primarily microglia) and diverse molecular mediators [1, 4]. Moreover, inflammation in the CNS contributes to peripheral inflammation and vice versa [5]. Possible triggers of neuroinflammatory processes—aside from infectious agents and traumatic factors—are genetic susceptibility, environmental factors contributing to maternal immune activation, stress, maladaptation, and others [6, 7]. On the other hand, neuroinflammation is not always associated with negative outcomes. Neuroinflammatory processes also take part in adaptive and reparative processes [1, 3].

Schizophrenia (SC) is a chronic multifactorial psychiatric disorder with a complex etiology and entails positive (psychotic) and negative symptoms and cognitive impairment [8]. Genetic predisposition and environmental factors provide the basis for the neurodevelopmental disturbances and neurotransmitter aberrations that eventually manifest themselves in the clinical phenotype of SC [8]. In the last few decades, there has been increasing evidence that the etiopathogenesis of SC is associated with neuroinflammatory mechanisms [9, 10, 11, 12]. For example, epidemiological cohort study revealed a correlation of pre- and postnatal infections with SC risk [13]. In addition, intriguing data recently emerged about the influence of gut dysbiosis on clinical symptoms [14] and about the kynurenine pathway’s (KP’s) linking inflammation with neurotransmitter aberrations in SC [15]. Nonetheless, the presence of neuroinflammation and its involvement in the etiopathogenesis of SC remain controversial issues [3]. Signs of neuroinflammation include microglial activation, infiltration of CNS tissue by immune cells, neural degeneration, and dysregulation of peripheral inflammatory biomarkers [3]. On the other hand, existing studies do not always take into account the above-mentioned criteria when SC is classified as a neuroinflammatory disease. This review critically summarizes available evidence on neuroinflammation and possible neuroinflammatory mechanisms of SC to answer the question whether the pathogenesis of SC is indeed associated with neuroinflammation.

This narrative review includes two main parts. The first part (sections 3 and 4) analyzes the evidence for neuroinflammation in SC (mainly results of postmortem studies providing direct evidence of neuroinflammation and data on peripheral inflammation being indirect evidence for neuroinflammation). The second part (sections 5–8) describes the major inflammation-related molecular mechanisms that may directly participate in the pathogenesis of SC (in particular the gut–brain axis, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, and a metabolic pathway called the KP). A literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The most relevant studies were selected, mostly those published within the last 25 years, but some included studies are older. In this review, only human studies were considered. There are also animal studies linking inflammation and SC [16], but these results cannot be directly translated to humans because animal models do not fully replicate features of SC in humans. Besides, population-based and association studies (e.g., epidemiological cohort studies on the association of prenatal infections with SC) were not examined in the review because they are only indirect evidence for the relation between inflammation and SC and have been reviewed previously [17]. The following basic keywords were used to screen the literature: “schizophrenia OR psychosis OR FEP” in combination with one or more terms (AND): “neuroinflammation”, “inflammation”, “brain”, “postmortem”, “immune cell infiltration”, “blood–brain barrier”, “microglia”, “astrocytes”, “cytokine”, “chemokine”, “gut microbiota”, “gut dysbiosis”, “gut-brain axis”, “hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis”, “kynurenine pathway”, “treatment”, and “meta-analysis”.

Postmortem brain samples have provided important information on inflammatory-gene expression in SC. Early systematic reviews and meta-analyses pointed to altered expression of inflammatory genes in the brains of patients at transcript and protein levels [18, 19]. For example, a systematic review by Trépanier et al. [19] revealed increased expression of proinflammatory genes—in particular interferon-induced transmembrane protein (IFITM) and serpin family A member 3 (SERPINA3)—in the brain of patients with SC, although other markers were not consistent and varied between studies. A meta-analysis by van Kesteren et al. [18] showed elevated expression of proinflammatory genes but no significant alterations of expression of anti-inflammatory genes in the brain of SC patients. By contrast, subsequent study with larger sample size failed to confirm the earlier findings [20]. In addition, a recent systematic review revealed heterogeneity of gene expression results across studies and methodological inconsistencies that impede data synthesis [21]. Thus, although some evidence indicates overexpression at the protein level of proinflammatory genes including cytokines [22], evidence at the transcript level is conflicting. The differences in the detected inflammatory changes among patients should be emphasized too. In particular, only approximately one-third of patients have exhibited signs of elevated neuroinflammation, indicating the existence of an immunophenotype of SC with marked inflammation [23]. Therefore, further steps need to be taken to standardize research methodology in order to make a conclusion about the expression of inflammatory genes in the brains of patients while taking into account brain regions, immunophenotypes, and other factors.

One of direct signs of neuroinflammation is thought to be infiltration of the brain parenchyma by peripheral immune cells [3, 24]. Under physiological conditions, out of immune cells, only resident immune cells (microglia) are found in the brain and spinal-cord parenchyma. Microglia precursors populate the CNS during embryonic development and then differentiate into microglial cells [25]. During neuroinflammation, other immune cells from the periphery are recruited to CNS tissue [3].

There are some articles indicating the presence of macrophages and T and B cells in the brain parenchyma of patients with SC (Table 1, Ref. [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38]).

| Cell type | Findings | Brain region | Reference |

| Infiltrating immune cells directly observed in the brain | |||

| T cells | A trend toward an increase in CD3+ T-lymphocyte density in the total group of patients and significantly higher density was observed in patients with treatment-resistant SC compared to paranoid SC and controls. | Posterior hippocampus | [26] |

| 15–37% of SC patients showed increased numbers of CD3+ T cells in the hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, frontal and temporal cortices, thalamus, and white matter. | Hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, thalamus, frontal and temporal cortex, white matter, plexus | [27] | |

| Elevated CD3+ T-lymphocyte density was detected in 1/3 of SC patients compared to controls. | Coronal whole brain sections | [28] | |

| A significantly lower proportion of SC patients had CD3+ T cells in leptomeninges than controls did. A trend toward an increase in the proportion of patients with CD3+ T cells in the gray-matter parenchyma was revealed (control: 46.2% vs. SC 69.4%, p = 0.061). | Dorsal PFC | [29] | |

| B cells | A significant increase in CD20+ B-lymphocyte density was observed in SC patients compared to controls. | Posterior hippocampus | [26] |

| 10% of patients showed increased counts of CD20+ B cells in the hippocampus but not in other regions as compared to controls. | Hippocampus, thalamus, frontal and temporal cortex, cingulate gyrus, white matter, plexus | [27] | |

| Elevated CD20+ B-lymphocyte density was detected in 1/3 of the patients compared to controls. | Coronal whole-brain sections | [28] | |

| Macrophages | CD163+ macrophages were found in the PFC parenchyma near neurons but not vessels in 6% of low-inflammation control subjects, 25% of high-inflammation control subjects, 9% of low-inflammation SC cases, and 43% of high-inflammation SC cases (p = 0.0096). | PFC | [30] |

| CD163+ cell density in the midbrain was significantly higher in SC patients than in controls. | Midbrain | [31] | |

| CD163+ cell density was higher in a high-inflammation SC subgroup compared to controls. | Subependymal zone | [32] | |

| CD163+ cell density in the subependymal zone was significantly higher in SC patients than in controls. | Subependymal zone | [33] | |

| Infiltration of the perivascular space by CD163+ or CD206+ macrophages was not detectable. | Dorsal PFC | [29] | |

| Expression of immune-cell markers in the brain | |||

| Macrophages | A trend toward increased CD163 mRNA expression (p = 0.09) in SC compared to controls. | Hippocampus | [34] |

| mRNA and protein expression of macrophage markers including CD163 and CD64 was higher in SC (and especially in a high-inflammation subgroup of the patients) compared to controls. | Midbrain | [31] | |

| mRNA expression of CD163 and CD64 was significantly higher in SC compared to controls. | Subependymal zone | [33] | |

| Macrophages and white blood cells | A comparison of the total group of patients to controls revealed no differences in mRNA expression of white blood cell markers, but the expression of CD163, CD16, and CD14 was significantly higher in the subgroup of SC patients with signs of high inflammation. | PFC | [30] |

| Macrophages, monocytes, and natural killer cells | Expression of CD163 and CD64 (macrophages), CD14 (monocytes), and FCGR3A (natural killer cells) was higher in a high-inflammation SC subgroup compared to controls. | Subependymal zone | [32] |

| Macrophages, monocytes, and natural killer cells | Expression of CD163, CD64, CD14, and FCGR3A was higher in a high-inflammation SC subgroup compared to controls. | Subependymal zone | [35] |

| Different immune cells | Prediction by means of gene expression levels showed that numbers of CD4+ T cells, plasma cells, mast cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells in SC patients were significantly higher than those in controls, while counts of CD8+ T cells, monocytes, and natural killer cells were significantly lower in SC patients. | Cerebral cortical tissue | [36] |

| The distribution of 24 immune-cell types (based on gene expression data in the hippocampus, PFC, and striatum) differed between SC patients and healthy controls. Relative abundance levels of T helper 1 (Th1) cells in the PFC, effector memory T (Tem) cells in the hippocampus, and T helper 2 (Th2) cells and mucosa-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells in the striatum were lower in the patients than in controls. | Hippocampus, PFC, and striatum | [37] | |

| Of 22 immune-cell types, relative abundance levels of 12 cell types were significantly different in SC compared to controls. Relative abundance of only neutrophils was higher, while the abundance of other immune-cell types was lower. | PFC or dorsolateral PFC | [38] | |

PFC, prefrontal cortex; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; SC, schizophrenia; FCGR3A, Fc gamma receptor IIIa also known as CD16A.

Increased density of CD163+ macrophages in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), subependymal zone, and midbrain has been found in SC, especially in patients with signs of high inflammation compared to controls [30, 31, 33, 35]. Of note, macrophages have been found in the perivascular space, indicating active migration of these cells through the vascular endothelium [30]. On the contrary, in a study by De Picker et al. [29], infiltration by CD163+ or CD206+ macrophages of the perivascular space in the dorsal PFC was not noted. Thus, infiltration of various brain regions by macrophages can differ among SC patients.

Findings about infiltration of various brain regions by CD3+ T lymphocytes are inconsistent too (Table 2, Ref. [26, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56]). Busse et al. [26] have detected an increase in CD3+ T-lymphocyte density in the posterior hippocampus of patients with treatment-resistant SC and a trend toward higher density of T cells in the total group of SC patients. Subsequent studies have also revealed increased T-lymphocyte density in the hippocampus and other brain regions (white matter, cingulate gyrus, and frontal and temporal cortices) in approximately one-third of the patients [27, 28]. A study on the dorsal PFC has uncovered only a trend toward an increased proportion of subjects with CD3+ T lymphocytes in this region among SC patients [29].

| Brain region | Findings | Reference |

| Morphological findings | ||

| Brains of embryos between 7 and 12 weeks old, developing in healthy females and females with mental disorders including SC | Microglial cells have diverse, sometimes stick-like shapes; they form multiple thin axons, actively phagocytose | [39] |

| PFC and visual cortex of patients with SC | Signs of activation of microglial cells | [44] |

| PFC of patients with SC | A decrease in the number of ribosomes in the cytoplasm of oligodendrocytes, a significant decrease in volumetric density and in the number of mitochondria and an increase in the number of lipofuscin granules | [48, 49] |

| PFC of patients with SC | Ameboid and dystrophic microglia adjacent to oligodendrocytes and significant dystrophic changes of oligodendrocytes adjacent to microglia | [47] |

| PFC of patients with SC | Mean values of volumetric density and the number of mitochondria are significantly decreased while the number of lipofuscin granules in microglia and oligodendrocytes is increased | [43] |

| Frontal and temporal cortex of a female with chronic SC | Ramified microglial cells showing on their surface the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II. Degenerative traits (thinning, cytoplasm shrinkage, shortening, and fragmentation of their processes) up to apoptotic changes. Damaged microglia contain phagosomes and/or degenerated mitochondria | [40] |

| White matter adjacent to the dorsolateral PFC (Brodmann area 9) | Numerous activated microglial cells | [42] |

| Frontal and temporal lobes | The number of activated microglial cells is higher in SC. The number of cells with degenerative traits and damaged processes is several-fold higher than that of microglia with well-developed ramification | [41] |

| Immunohistochemical analysis | ||

| Posterior hippocampus of patients with SC | A trend toward an increase in HLA-DR+ microglia density in paranoid SC versus controls and significantly higher density as compared to treatment-resistant SC | [26] |

| Dorsolateral PFC (Brodmann area 9), superior temporal gyrus (area 22), and anterior cingulate gyrus (area 24) of patients with SC | Increased HLA-DR+ microglial numerical density in areas 9 and 22 | [45] |

| Frontal cortex and hippocampus | HLA-DR+ cells in some patients with SC | [46] |

| Dorsolateral PFC, anterior cingulate cortex, mediodorsal thalamus, and hippocampus | No effect of diagnosis on HLA-DR+ microglial density | [51] |

| Dorsolateral PFC, anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, and mediodorsal thalamus | HLA-DR+ microglial cell density is not significantly different between SC and controls | [50] |

| CA1, CA2/3, and dentate gyrus area of the posterior hippocampal formation | Reduced microglial quinolinic acid content in the hippocampal CA1 region in SC. No effect of diagnosis on HLA-DR+ microglial density | [52] |

| Frontal, temporal, and cingulate cortical gray matter, subcortical white matter regions, including the anterior corpus callosum | An increase in IBA-1+ microglia density in cortical gray-matter regions and in frontal and temporal subcortical white-matter regions in SC | [54] |

| Superior frontal cortex, superior temporal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex | Increased numbers of microglia are present in the superior frontal cortex of SC, and these cells exhibit higher inflammasome protein expression compared to controls | [53] |

| White matter adjacent to the dorsolateral PFC (Brodmann area 9) | The density of IBA-1–stained microglia does not differ between SC and controls | [42] |

| Anterior midcingulate cortex | The density of IBA-1–stained microglia does not differ between SC and controls | [56] |

| Dorsolateral PFC (Brodmann area 9) | There is no significant difference in the number of CD68+ microglia expressing calprotectin between groups of subjects. Calprotectin (S100 calcium-binding protein): expression is upregulated in microglia | [55] |

HLA-DR, human leukocyte antigen DR isotype; IBA-1, ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1.

In the case of CD20+ B lymphocytes’ infiltration, increased B-cell density is reported in the hippocampus and other brain regions of SC patients [26, 27]. Nevertheless, as with macrophage and T-cell infiltration, higher B-cell density is detected in ~10–30% of the patients [27, 28]. These data indicate the existence of a subgroup of patients with upregulated markers of neuroinflammation and immune-cell infiltration. On the other hand, immune-cell infiltration varied among different parts of the CNS, and therefore further investigation is needed to elucidate the region specificity of the infiltration of the brain parenchyma by immune cells.

Data on messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and protein expression of immune-cell markers have also yielded indirect evidence of brain tissue infiltration by immune cells (Table 1). The most common finding has been macrophage infiltration in various brain sections of SC patients. In particular, overexpression of macrophage genes (CD163 and CD64) in the midbrain and PFC has been observed in a subgroup of SC patients with signs of high inflammation as compared to controls [30, 31], although CD16 and CD14 expression characteristic of white blood cells was also found to be increased within the PFC in this subgroup of patients [30]. A hippocampus study has revealed a trend toward increased CD163 mRNA expression in the total group of SC patients [34]. A number of articles on the subependymal zone show increased expression of genes of macrophages (CD163 and CD64), of natural killer (NK) cells (Fc gamma receptor IIIa also known as CD16A (FCGR3A)), and of monocytes (CD14) in a subgroup of the patients with high inflammation as compared to controls and patients without signs of inflammation [32, 33, 35].

Large-scale gene expression data also make it possible to detect the presence of immune cells in the brain (Table 1). Immune-cell infiltration prediction based on expression levels using the CIBERSORT algorithm has shown that the numbers of CD4+ T lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and mast cells in SC patients are significantly higher than those in controls, while the counts of CD8+ T cells, monocytes, and NK cells are significantly lower in the cerebral cortical tissue of SC patients [36]. Relative-abundance analysis of immune cells by the ImmuCellAI algorithm suggests that the distribution of 24 immune-cell types based on gene expression data in the hippocampus, PFC, and striatum differs between SC patients and healthy controls [37]. Notably, relative abundance levels of effector memory T cells in the hippocampus, of T helper (Th) 1 cells in the PFC, and of mucosa-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells and of Th2 cells in the striatum have proven to be lower in the patients than in controls [37]. A recent work also based on the CIBERSORT algorithm showed that among 22 immune-cell types, relative abundance levels of 12 cell types, specifically CD8+ T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), neutrophils, M0 macrophages, eosinophils, resting mast cells, activated and resting NK cells, activated and resting dendritic cells, and memory B cells are significantly different between SC and controls. Relative abundance levels of the aforementioned immune cells were lower in the patients with the exception of relative abundance of neutrophils, which was higher in the PFC of patients with SC [38]. Thus, these papers indicate aberrations in the distribution of immune cells in brain regions in SC. Further studies, including those based on single-cell RNA sequencing technologies [57], will provide a better understanding of the presence of immune cells within the brain parenchyma in SC.

Taken together, the data described above point to evidence of neuroinflammation and immune-cell infiltration of CNS tissue in SC (Fig. 1), at least in the subgroup of patients with signs of high inflammation.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Signs of neuroinflammation and neuroinflammatory mechanisms associated with the pathogenesis of SC. The main evidence for neuroinflammation in SC includes signs of microglial activation, dysregulation of expression of some inflammatory genes, altered levels of kynurenine pathway (KP) metabolites, and infiltration of brain tissue by peripheral immune cells. A compromised blood–brain barrier (BBB) and/or blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCB) contributes to the invasion of peripheral immune cells and inflammatory mediators into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and brain parenchyma. Well-documented dysregulation of cytokines, chemokines, and other immune-system mediators along with anomalous immune-cell numbers in the periphery reflect neuroinflammatory processes in the brain of SC patients. Diverse inflammation-related mechanisms have been hypothesized to be associated with the pathogenesis of SC. Peripheral inflammation and a compromised BBB and/or BCB may contribute to immune-cell infiltration of the brain parenchyma and microglia activation. Given that SC is a neurodevelopmental disease, microglial activation during development may lead to dysregulation of synaptic pruning and in adulthood to impaired neuroplasticity. Inflammation can also lead to glymphatic-clearance dysfunction and white-matter pathology. Altered tryptophan metabolism and changed KP in the brain are considered a molecular mechanism mediating neurotransmitter aberrations in SC. Ultimately, neuroinflammation leads to functional brain dysconnectivity and the manifestation of clinical symptoms of SC. Dysregulation of the HPA axis and dysregulation of the gut–brain axis are thought to be some of the mechanisms linking peripheral and central inflammation. Created with CorelDRAW Graphics Suite X8 (Corel Corporation, Ottawa, ON, Canada).

A BBB pathology has been hypothesized to be a key component of the pathophysiology of SC [58]. There is a growing body of reproducible evidence of BBB impairment in SC [59, 60, 61]. Regrettably, there is a common misunderstanding of the term BBB in the literature [62]. Biomarkers of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that are often employed as markers of BBB permeability reflect primarily BCB status and only indirectly BBB integrity. Existing evidence indicates increased BCB permeability in SC [59]. Approximately 40% of first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients have shown CSF alterations [59, 60]. A meta-analysis has uncovered increased levels of total protein, albumin, IL-6, and IL-8 and a higher IgG ratio in CSF of the patients compared to healthy controls [61]. A recent meta-analysis confirmed these findings and revealed an increased white blood cell count in the CSF of the patients compared to healthy individuals [63]. Furthermore, an elevated concentration of complement component 4A has been detected in the CSF of FEP patients; this observation may explain the decreased postsynaptic density and excessive synaptic pruning identified in SC [64]. These data support the notion of BCB impairment in SC.

Neuronal markers detected in the blood can be used as biomarkers of BBB integrity. A meta-analysis suggests that the concentration of calcium-binding protein S100B (abundant in glial cells) is significantly elevated in the blood of SC patients compared with controls [65]. S100B is released into the circulation in substantial amounts during a BBB disturbance. Of note, in that work, S100B levels rose with increasing duration of the illness, indicating gradual deterioration of BBB integrity in the course of SC [65].

Consequently, multiple lines of evidence point to BBB and BCB impairments in SC (Fig. 1). Elevated permeability of these barriers may contribute to the above-mentioned cellular infiltration into the CNS parenchyma. Additionally, compromised barriers promote the infiltration of inflammatory molecules into (and their exfiltration out of) the CNS. Therefore, impaired integrity of the BBB and BCB may be important factors contributing to the proinflammatory state in the CNS during SC.

Microglia are resident myeloid-lineage innate immune cells. Microglial functions in the CNS include participation in tissue homeostasis and in responses to infection and injury [66]. After immunogenic stimulation, microglial activation is observed, characterized by morphological shifts, stronger synthesis of cytokines, and heightened production of reactive oxygen species, which potentiate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor–mediated responses [66, 67, 68]. Research into microglia in SC began in the 1970s, primarily by means of postmortem brain samples (Table 2). One of the first articles revealed significant morphological changes in microglial cells in embryos of SC patients [39]. According to Wierzba-Bobrowicz et al. [40, 41], most of activated microglial cells show degenerative alterations, which are most likely a consequence of initial disturbances of the neuron–glia communication. Further studies have revealed—aside from microglia activation [26, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46]—dystrophic changes in oligodendrocytes attached to microglial cells [43, 47, 48, 49]. Moreover, microglial dystrophy may contribute to degenerative changes in oligodendrocytes in SC patients having predominantly positive symptoms [43].

In addition to morphometric assays, immunohistochemistry is widely used to evaluate microglia. The most popular indicator of microglial activation is human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DR isotype: a major histocompatibility complex II protein [69]. There are no clear findings regarding changes in HLA-DR+ microglia density in SC. A number of researchers have noted elevated density of HLA-DR+ microglia within various areas of the brain in individuals with SC [26, 45, 46]. By contrast, Steiner et al. [50, 51] have not confirmed the association between microglial HLA-DR expression and SC, suggesting that microglial activation may be a result of presuicidal stress. Gos et al. [52] have also detected no changes in overall density of microglial cells in SC. Nonetheless, those authors have found a lowered number of quinolinic acid (QUIN)-immunoreactive microglial cells in the hippocampus of SC patients; this alteration may impair glutamatergic neurotransmission [52]. Another marker of microglia is ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA-1): a marker of both activated and resting microglia [69]. A comparative analysis of brains of patients with SC and healthy individuals has revealed notable expansion of the population of IBA-1+ microglia in the former group [53, 54]. Furthermore, microglia in these patients with SC expressed more of an inflammasome protein as compared to nonpsychiatric controls [53]. Despite the lack of differences in the number of CD68+ microglial cells, calprotectin expression is reported to be upregulated in frontal-cortex microglia [55]. In another paper, the density of IBA-1–stained microglia did not differ among groups of subjects [42, 56]; however, a qualitative assessment of microglial morphology detected numerous activated microglial cells [42]. Furthermore, those investigators demonstrated greater lateralization of microglial density to the right hemisphere in SC patients [56]; effect(s) of this phenomenon remain unclear [56].

Given the constraints of postmortem studies, in vivo research on microglia in SC is rapidly advancing. One of the most popular approaches is positron emission tomography (PET). Activated microglia overexpress 18kDa translocator protein (TSPO) in mitochondria, thereby making it an important target of neuroimaging analyses [70]. According to results of a meta-analysis of 12 studies, there is enhancement of tracers’ binding to TSPO in gray matter of SC patients relative to controls when binding potential is used as an outcome measure, but there are no significant differences when the volume of distribution is used instead [71]. On the other hand, a meta-analysis covering five research articles about second-generation tracers has revealed a reduction in the volume of distribution in the patients relative to healthy donors [72]. In recent years, there was a discussion about the oversimplification of TSPO as a marker of microglial activation [73]. It was shown relatively recently that TSPO is not a marker specific for activated microglia [74]; therefore, it is necessary to develop other radioligands for certain immune mechanisms. Research on microglia-like cells derived from monocytes [75] or pluripotent stem cell [76] is gaining momentum. The molecular phenotype of microglia-like cells from SC patients differs significantly from that of healthy controls [75]. A research article on monozygotic twins with SC indicates that microglia-like cells feature overexpression of inflammation-related genes and anomalies related to extracellular-matrix signaling [76].

Therefore, there is compelling evidence of microglial changes in patients with SC (Fig. 1). The emergence of new modern methodological approaches to the investigation of microglia may help to understand these shifts and to devise new therapeutic strategies.

Astrocytes derive from the neuroepithelium, namely from radial glial cells. Astrocytes express various receptors, enzymes, transporters, and ion channels, which allow them to regulate and ensure the homeostasis of ions, reactive oxygen species, neurotransmitters, pH levels, and nutrients [77]. Astrocytes perform a crucial function in neurodevelopmental and homeostatic processes related to the pathogenesis of SC, e.g., glutamatergic neurotransmission, synaptogenesis, synaptic pruning, and myelination [78]. In patients with SC, an increase in the volumetric proportion and surface numerical density of astrocytes is observed in the pyramidal region of the hippocampus, in particular within the CA3 area [79]. Nevertheless, in the posterior hippocampal CA4 area in SC, the number and density of astrocytes are reported to be comparable between SC patients and healthy controls [80]. In individuals with SC, a notable reduction in astrocyte density has been registered in the cingulate white and gray matter and in the midline of the corpus callosum, when compared to healthy controls [81]. Two independent research groups have reported contradictory changes in the astrocyte number within the mediodorsal thalamus nucleus in patients with SC [82, 83]. The ultrastructure of perineuronal astrocytes has been associated with gender and age of manifestation of the disorder [84]. Several immunohistochemical studies on glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) as an astrocyte marker have not detected astrogliosis in the brains of patients with SC [85, 86, 87, 88]. On the other hand, Rajkowska et al. [89] have reported the development of only a subtle, type- and layer-specific astroglial pathology in layer V of the dorsolateral PFC in SC. Catts et al. [90] have documented overexpression of GFAP and of three mRNA transcripts associated with astrogliosis as well as altered astrocyte morphology only in the brains of SC patients featuring upregulation of inflammatory markers. Besides, there is higher expression of an astrocytic gene’s (aldehyde dehydrogenase-1 family member L1) mRNA in individuals with SC compared to a control group [91]. Overall, reports regarding the morphology and density of astrocytes in SC differ depending on the brain region examined and the methods employed. It is likely that astrocytic responses in SC do not manifest themselves in the entire cohort of the patients and may be transient, depending on the stage of the disease.

An increase in the amount of peripheral inflammatory markers is thought to

reflect neuroinflammatory processes in the CNS (Fig. 1). There are few research

articles on the relation between peripheral and central inflammatory biomarkers.

FEP patients have shown a significant correlation between the level of plasma

inflammatory molecules (macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)

1

A large number of articles deal with the assessment of peripheral immunoinflammation in patients with SC. The inconsistency of the literature regarding the cytokine spectrum in SC has been due to several factors related to the heterogeneity of study samples of patients. It should be noted that changes in cytokine profiles can vary among different categories of patients, including drug-naïve and FEP patients, FEP patients receiving antipsychotic drugs, patients with a stable chronic condition, and patients with a chronic condition in acute relapse [98]. Furthermore, the duration of the disease, the severity of the symptoms, the presence of aggressive behavior, and cognitive abilities of the patient can all exert an influence on the levels of certain cytokines [98, 99]. Below we examine characteristics of immune inflammation in relation to clinical manifestations of SC.

Results of meta-analyses indicate that FEP patients exhibit elevated levels of

proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF, IL-6, IL-12, and transforming growth

factor (TGF)

The inflammatory response in patients with SC varies among stages of the

disease, and a chemokine such as IL-8/chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL) 8

(CXCL8) acts as a potential predictive factor and may serve as a significant

immunological signature of SC stages [107]. A fairly large number of articles

have shown an increase in the IL-6 level during the chronic stage of the disease

[108, 109, 110, 111]. A meta-analysis of 40 studies suggests that cytokine levels in SC

depend on clinical status of the patients [99]. For example, levels of such

cytokines as TGF-

A number of articles have revealed a correlation of IFN-

Upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1

Patients with SC are a high-risk group for MetS, with a prevalence of 32.5% in

this population according to a meta-analysis of 77 publications (n = 25,692)

[120]. MetS develops mainly as a consequence of antipsychotic therapy [121] and

is characterized by abnormal production of proinflammatory cytokines and the

activation of lipid peroxidation [122, 123]. Intervention with atypical

antipsychotics for 5 years resulted in weight gain and elevated serum levels of

interleukins IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and INF-

Patients with SC smoke at a higher rate and to a greater extent than the general population does and in comparison to patients with other mental disorders [132]. Smoking has a negative effect on the immune system [133]. Data on the relation between immune inflammation and smoking in the SC population are conflicting. IL-2 and IL-6, but not IL-8 or TNF, are significantly downregulated in smoking SC patients compared to nonsmoking patients [134]. Smoking patients with SC have lower NK cell activity [135]. An abnormal C-reactive protein level is linked to MetS but not cigarette smoking [136]. In patients with SC, however, chronic peripheral inflammation (as evidenced by a highly sensitive assay for C-reactive protein) has been associated with severe nicotine dependence [137]. In an in vitro experiment, blood serum from smoking patients with SC significantly enhanced T-cell proliferation; the use of blood serum from nonsmoking patients or healthy individuals did not have such an effect [138].

Thus, concentrations of peripheral inflammatory biomarkers vary depending on the stage, course of SC, treatment, or comorbidities and presumably reflect neuroinflammatory processes in the CNS.

Neuroinflammation may be linked with the pathogenesis of SC through various mechanisms (Fig. 1). The most important ones are discussed below, in particular dysregulation of the HPA axis and of the gut–brain axis and disturbances in the KP.

Accumulating evidence indicates that the gut microbiota may influence brain function through the intricate gut–brain axis, and this effect may be a contributing factor for the development of SC [14, 139, 140]. The gut–brain axis is a bidirectional communication network whose effects are exerted through pathways involving the neuroendocrine HPA axis, the immune system, and the autonomic nervous system [141]. The gut microbiota is not the only factor that can affect the HPA axis activity through mediators that cross the BBB; exposure to stressors can also influence mediators of the HPA axis, thereby affecting the gut barrier [141]. In the earliest stages of life, the intestinal microbiota seeded by the vaginal microbiota during delivery is pivotal for programming the developmental trajectory of the HPA axis, thus influencing stress sensitivity, the functioning of the HPA system, and the maturation of the immune system. The interaction between the HPA axis and the microbiota (gut)–brain axis is particularly notable in the hippocampus, which is consistently negatively affected in individuals with SC [142].

Through animal studies, several mechanisms have been identified that link the gut microbiota with dysfunction of the HPA axis. It has been demonstrated that the gut microbiota can activate the HPA axis via a release of many mediators such as microbial antigens, cytokines, and prostaglandins, which are able to cross the BBB. Furthermore, evidence suggests that different microbial species can influence ileal corticosterone production, thereby possibly affecting the HPA axis [143].

Alterations of gut microbiota activity can also have effects on neurotransmission, myelination, and BBB function [144, 145]. The alteration of the gut microbiota in SC has been found to vary across studies. A systematic review of both preclinical and clinical studies has revealed that despite considerable variation of findings owing to confounding factors, there is significant evidence supporting the hypothesis of an altered gut microbiome in psychosis as compared to healthy individuals. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that alterations in the gut microbiome may occur prior to the onset of the clinical diagnostic symptoms of SC spectrum disorders, although further investigation is required to fully test this hypothesis [146].

Eight gut microbial taxa are reported to be consistently upregulated in SC patients: Acidaminococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, Gammaproteobacteria, Lactobacillaceae, Lactobacillus, Proteobacteria, Succinivibrio, and Prevotella while five taxa have been found to be consistently downregulated in SC: Anaerostipes, Coprococcus, Faecalibacterium, Fusicatenibacter, and Roseburia. These results suggest that the gut microbial profile of patients with SC exhibits depletion of anti-inflammatory butyrate-producing genera and enrichment with certain opportunistic bacterial genera and probiotics [140].

Results of 16S rRNA and metagenomic gene sequencing have revealed that patients with SC have elevated relative abundance of Clostridium and Megasphaera. A functional analysis indicates that disturbances in phosphonates, sphingolipids, phosphinates, and glutamine metabolism may be implicated in the initiation and development of SC [147].

It has been demonstrated that early-life stress, in conjunction with a multitude

of stressors encountered during different developmental stages, is linked to

aberrant composition of the gut microbiota. This aberration in turn gives rise to

irregular immunological and neuroendocrine functions, which may be a contributing

factor for the onset of FEP [148]. Misera et al. [149] have noticed that

the observed differences pertain to bacteria associated with inflammatory

processes, with formation of short-chain fatty acids, and with the biosynthesis

of metabolites related to mental health, including lactic acid and

SC and antipsychotics have been reported to have distinct and shared effects on

the composition of the gut microbiota. A recent meta-analysis by Cheng et

al. [151] was aimed at evaluating the profile of the gut microbiota in patients

with SC systematically, at elucidating the effect of antipsychotic use, and at

revealing unique and shared gut bacteria for SC and for antipsychotic

medications. Changes in

Gut microbiota dysbiosis and immune dysfunction have a significant impact on the

development of antipsychotic-induced MetS. In MetS, decreased bacterial

Chronic use of antipsychotic drugs can cause gut microbiota dysbiosis, resulting in dysregulation of neurotransmitters such as glutamate, dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine; in enhancement of inflammatory pathways; in oxidative stress; and in mitochondrial dysfunction [153].

Recent papers point to a potential link between the profile of the gut microbiota and cognitive functioning. Findings in a study by Frileux et al. [154] highlight a link between gut dysbiosis and cognitive impairment. This relation identified specific taxa (Haemophilus, Bacteroides, and Alistipes) as possible contributors to enhanced cognitive performance. Conversely, a negative correlation was observed between the presence of Candida albicans, Toxoplasma gondii, Streptococcus, and Deinococcus and diminished performance on cognitive tests. Administration of prebiotics and probiotics turned out to be associated with enhanced cognitive performance [154].

Overall, studying the gut–brain axis is intriguing, but this area of research is still in its rudimentary stages, and therefore further research is needed.

Investigation of the KP in the pathogenesis of SC is of interest because this pathway is located at the intersection between neuroinflammation and glutamatergic neurotransmission [155, 156].

Amino acid tryptophan is converted into indoles, melatonin, and serotonin. A substantial proportion of tryptophan is metabolized via the KP, which is named after tryptophan’s primary metabolite: kynurenine. This process gives rise to a multitude of neuroactive compounds that exert various effects on brain function and dysfunction [157].

The main metabolites of the KP that have neuroactive properties and are most frequently studied are 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK), kynurenic acid (KYNA), picolinic acid (PIC), and QUIN. 3-HK and QUIN have neurotoxic effects and take part in the pathogenesis of major psychotic disorders inclusive of SC, whereas KYNA and PIC possess neuroprotective properties. It is becoming increasingly evident that ratios of neurotoxic to neuroprotective metabolites may provide valuable insights into possible prediction of manifestations of disease states versus healthy physiological processes [158].

Alterations in the spectrum of KP metabolites have been detected in postmortem brain tissues of SC patients with either FEP or chronic SC treated with antipsychotic drugs [159, 160, 161].

Kynurenine, 3-HK, anthranilic acid, and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid levels have proven to be significantly increased in white and gray matter of the dorsolateral PFC of the patients; on the contrary, concentrations of tryptophan, QUIN, and KYNA are elevated only in white matter and are not changed in gray matter [162]. The detected activation of the KP did not depend on gender, age, or clinical or pharmacological parameters of the patients. On the basis of these findings, those authors hypothesized disturbances of two branches of the KP, namely the transamination of kynurenine into KYNA and the hydroxylation of kynurenine into 3-HK, only in white matter of the brain and concluded that disturbances in white matter are implicated in the pathogenesis of SC [162].

Published findings on peripheral levels of KP metabolites in SC are contradictory. In SC patients, increased plasma KYNA levels have been documented [163], but other articles point to decreased or unchanged KYNA levels [164]. Results of a recent meta-analysis by Cao et al. [164] suggest that treated patients exhibit significantly elevated kynurenine levels as compared to healthy individuals. Furthermore, higher kynurenine and KYNA levels in CSF and lower plasma kynurenine levels correlated with SC in that work. Additionally, kynurenine levels proved to be higher in individuals with SC after antipsychotic therapy when compared to baseline [164].

Results of a meta-analysis including 101 studies on patients with mental disorders (n = 10,912) suggest that plasma/serum concentrations of tryptophan and kynurenine are diminished in SC patients, whereas the level of KYNA is not altered [165]. The findings indicate a potential alteration of tryptophan metabolism, with a shift from serotonin to the KP during SC and several other mental disorders [165].

Peripheral levels of KP metabolites may depend on several factors, including disease duration and antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Most noticeable changes are seen in antipsychotic-naïve patients with FEP; peripheral blood levels of tryptophan, kynurenine, anthranilic acid, and KYNA are reported to be significantly reduced at the early stage of the disease [166].

Another study indicates that possible immune-system–mediated hyperactivity of

the KP is correlated with clinical leading symptoms and treatment outcomes in FEP

patients [167]. A positive association was observed there between KYNA and

IL-1

According to a systematic review by Sapienza et al. [168], metabolites of the KP affect cognitive function in SC patients, and KP activation leads to greater cognitive deficits. Composite cognitive scores are negatively associated with elevated peripheral QUIN levels in SC patients [169]. Huang et al. [170] have demonstrated that levels of KYNA negatively correlate with attention/vigilance and social cognition in patients with SC.

KP metabolites and immunoinflammatory markers have different effects on cognitive functions depending on the patient’s cognitive phenotype [171]. The predominant effect of inflammation is observed in patients with relatively well-retained cognitive abilities, while a disturbance in the KP plays a major role in patients with severer deficits. Predictive markers of cognitive improvement obtained in the work just cited suggest that this pathway may play an important part in dynamic modulation of cognition. These pilot data open new horizons for nonpharmacological modalities such as cognitive remediation and aerobic exercise [171].

Thus, most of relevant studies in the literature deal with the quantification of peripheral metabolites in the blood. An important question is whether there is an association between blood and CNS levels of these metabolites because most of them are unable to cross the BBB. Orhan et al. [172] have published a correlation between plasma kynurenine, KYNA, and QUIN levels and their CNS concentrations in healthy persons. According to another study, however, serum levels of KP metabolites are not correlated with the findings in the CNS except for an increase in blood indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity [159]. Most probably, central levels of KP metabolites provide insight into pathogenetic mechanisms of SC, whereas blood levels may be regarded as biomarkers that provide insight into the disease’s progression or into treatment [173].

SC is known to be linked with reduced gray matter volume, white-matter aberrations, and impaired connectivity between brain regions. It has been suggested that the functional, cellular, and microstructural aberrations found in SC are related to neuroinflammation. Some possible implications of neuroinflammation for the pathogenesis of SC are discussed below (Fig. 1).

Microglia are key regulators of neuronal plasticity and synaptic pruning during neural development and in adulthood [174]. Microglia implement synaptic remodeling via various mechanisms, including through the complement system [175]. Overactivation of microglia and complement system dysfunction may be connected with excessive synaptic pruning and altered neuroplasticity in SC [174, 176]. The notion of excessive microglia-mediated synaptic pruning in SC is supported by several genetic articles [175, 177]. Moreover, SC patient–derived induced microglia-like cells are characterized by greater synapse uptake, which is partially caused by some genetic variants of the complement factor C4A gene [178]. Microbiota dysbiosis–associated inflammation is also hypothesized to contribute to the excessive synaptic pruning in SC [179]. Nevertheless, the role of neuroinflammation in aberrant synaptic pruning and neuronal plasticity is not yet fully established.

The glymphatic system contributes to the excretion of various toxic metabolites from the CNS. A proinflammatory state can trigger dysfunction of glymphatic clearance in SC [5]. Astrocytes expressing aquaporin-4 water channels play an integral role in glymphatic clearance. Astrocyte dysfunction caused by peripheral inflammation or neuroinflammation can lead to dysfunction of glymphatic clearance and accumulation of toxic compounds and inflammatory mediators in the CNS thereby creating a vicious cycle [180, 181]. Recently, the first evidence of glymphatic dysfunction in SC came out [182]. Nevertheless, the role of neuroinflammation in glymphatic-clearance dysfunction in SC is still unclear.

Different lines of evidence indicate neuroinflammation-related white-matter anomalies such as decreased white-matter volume and increased interstitial neuronal density in SC [183]. Elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and inflammation-induced oxidative stress are thought to cause oligodendroglial death, axonal damage, and impaired myelination [184]. Activated microglia secreting cytokines and reactive oxygen species may contribute to apoptotic death of oligodendroglia thus preventing myelination and normal white-matter development [185]. Advances in diffusion magnetic resonance imaging technology have yielded new evidence of white-matter aberrations in SC. In particular, studies on free water in the brain have detected an increase in this parameter at initial stages of SC [186]. A meta-analysis has confirmed increases in white-matter free-water amounts in SC [187]. An elevated amount of free water may be associated with peripheral inflammation in SC because a positive correlation has been detected between a free-water index and plasma concentrations of IL-6 and TNF [188]. Nonetheless, further research is needed on the contribution of neuroinflammation to white-matter anomalies in SC.

A proinflammatory state at the periphery and in the CNS may affect functional and structural connectivity of various brain regions [189]. This theory is supported by a number of identified relations of endogenous inflammation with structural dysconnectivity [190, 191]. For example, IL-6 levels correlate with reduced fractional anisotropy in several brain regions of patients with SC [190]. Inflammation-derived disturbances in neural circuits and networks may eventually induce clinical symptoms of SC. This idea is also supported by a plethora of data on the association of peripheral inflammatory mediators with clinical symptoms of SC including positive/negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunction (see section 4). On the other hand, specific pathways via which inflammation affects neural circuits in SC are far from fully understood.

Neuroinflammation is regarded as a pivotal factor in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative, neurodevelopmental, and neuropsychiatric disorders [192, 193, 194]. Although neuroinflammation is common to many CNS pathologies, immunological features may differ significantly among the diseases. Misinterpretation of the term “neuroinflammation” may lead to unjustified therapeutic interventions. A “true” neuroinflammatory disease is multiple sclerosis and its animal model: experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. This disease is due to the infiltration of Th cells into the CNS, resulting in gradual degradation of myelin sheaths. This process is marked by localized inflammation, activation of microglia, and additional infiltration by peripheral immune cells. Both microglia and invading myeloid cells respond to danger signals and cytokines released by T cells, thereby intensifying the inflammatory response. In summary, the initiation and progression of this disease are viewed as consequences of systemic immune dysregulation rather than internal dysfunction within the CNS [24]. In contrast to multiple sclerosis, the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease—another neurodegenerative disease—is thought to be the formation of abnormal proteins in the brain [193]. For SC, it is impossible to establish with certainty a specific etiological factor. According to a meta-analysis, patients with multiple sclerosis are at an elevated risk of SC [195]. There is no evidence that SC is an autoimmune disorder, but a number of studies point to the formation of autoantibodies against neuroproteins in SC and psychosis [196]. A genome-wide study on SC and multiple sclerosis has discovered 36 genetic loci shared between these disorders. A functional analysis of the common loci implies biological processes that are related to immune-response and B-cell receptor signaling pathways [197]. HLA genes have been found to participate in the development of both multiple sclerosis and SC. Nonetheless, alleles with an increased risk of multiple sclerosis correlate with a reduced risk of SC [198]. On the other hand, transcriptomes of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and SC are reported to differ significantly from those of patients with “classic inflammatory diseases”, including multiple sclerosis [199]. Thus, despite evidence of a neuroinflammatory component in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis and SC, immune dysfunction differs between these diseases. Further investigation into the relation between multiple sclerosis and SC may help to clarify underlying mechanisms of these pathologies.

Targeting of inflammatory pathways can lead to new strategies for the treatment of SC [200, 201]. A growing amount of evidence supports an alleviating effect of immunomodulators on symptoms of SC [202, 203]. A meta-analysis by Çakici et al. [204] has shown that various anti-inflammatory agents can reduce the severity of SC symptoms. Safari and Mashayekhan [205] have demonstrated that immunomodulation can be potentially used as an adjunctive therapy against mental illnesses. There is evidence that the addition of acetylsalicylic acid to conventional psychiatric treatments has the potential to enhance therapeutic efficacy of treatments of bipolar disorder and SC [206]. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) 2 (in the arachidonic acid pathway) can inhibit cytokine responses and minimize inflammation [207]. COX2 inhibitors may prove to be a promising therapeutic option for the management of clinical symptoms in FEP patients [208]. Monoclonal antibody therapy has been identified as a promising avenue for the treatment of specific subgroups of patients with SC and those exhibiting psychiatric symptoms associated with autoantibodies [209]. Rituximab and ocrelizumab were recently tested in clinical trials and provided a cognitive-function benefit in patients with SC [210, 211]. Adalimumab (a TNF blocker) have proven an efficacious treatment of both positive and negative symptoms of SC [212]. Neuroactive steroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may reduce some symptoms of SC when applied as an adjunctive therapy [213]. Key KP enzymes such as tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, kynurenine 3-monooxygenase, kynurenine aminotransferases, QUIN phosphoribosyltransferase, 3-hydroxyanthranilate oxidase, and others may also be considered targets for the development of new therapeutic strategies [214, 215].

Specific features of inflammation in SC must be taken into account when approaches to anti-inflammatory therapy are designed; one of the reasons is that many anti-inflammatory medicines have failed to alleviate SC symptoms: dextromethorphan, pregnenolone, davunetide, fatty acids, and statins [216, 217]. These findings highlight the growing importance of immune dysfunction as a critical factor in the targetable pathology of SC.

The evidence described above needs to be interpreted in light of the limitations of this review. First, this review did not cover studies on animal models because they do not provide direct evidence of neuroinflammation in SC. Second, the review did not touch on population-based studies and research into association of inflammatory diseases with SC risk because they provide only indirect evidence for the involvement of inflammation in the pathophysiologic mechanisms of SC. Third, the results presented in section 3 are mostly data from postmortem studies providing insights into the end stages of SC, often reflecting chronic disease processes. Fourth, many of the described mechanisms underlying the involvement of neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of SC are hypothetical (sections 5–8). Consequently, further studies are needed to elucidate the contribution of specific pathways to the pathogenesis of the disease. Lastly, the narrative nature of this review accounts for the breadth of the topic but limits the depth of some sections.

This review shows that despite some heterogeneity and inconsistency, there is considerable mixed evidence of neuroinflammatory processes in SC, which are related to aberrations of inflammatory-gene expression and of immune-cell infiltration of CNS tissues, BBB and BCB anomalies, microglial activation, and signs of peripheral inflammation. Nonetheless, neuroinflammatory processes are manifested to different degrees among patients, indicating the existence of immunophenotypes of SC with and without inflammation. Thus, neuroinflammation may be entwined in the pathogenetic mechanisms of SC. On the other hand, neuroinflammation may not necessarily be linked with negative outcomes. It is possible that neuroinflammation also reflects activation of reparative processes [3].

Inflammatory markers quantified in peripheral blood can serve as diagnostic and screening tools or indicators of inflammatory status and symptom severity in patients with SC [98, 218, 219]. A promising avenue of research is the use of machine learning (such as deep neural networks) and artificial intelligence—to analyze biomarkers, including cytokine and chemokine concentrations—which make it possible to construct predictive models [220, 221, 222]. For example, there are predictive models based on immune blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of SC [222]. Predicting a response to pharmacotherapy is another option for the use of immunological parameters, in particular cytokines [223, 224]. Patient stratification by immune inflammation markers may help clinicians choose the best treatment option [225, 226].

3-HK, 3-hydroxykynurenine; BBB, blood–brain barrier; BCB, blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier; CNS, central nervous system; COX, cyclooxygenase; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FEP, first-episode psychosis; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HPA, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal; IBA-1, ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; KP, kynurenine pathway; KYNA, kynurenic acid; MCP, monocyte chemotactic protein; MetS, metabolic syndrome; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; NK, natural killer; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; PFC, prefrontal cortex; PIC, picolinic acid; QUIN, quinolinic acid; SC, schizophrenia; TGF, transforming growth factor; Th, T helper; TNF, tumor necrosis factor

EE and SI designed the research study. IM and AB performed investigation. EE, IM, AB, and SI participated in literature search and selection, critical analysis and knowledge synthesis. All authors completed the writing of the original draft. EE and SI contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The authors would like to thank http://shevchuk-editing.com/ for English editing.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.