1 School of Basic Pharmaceutical and Toxicological Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Louisiana Monroe, Monroe, LA 71201, USA

Abstract

Aging alters estrogen receptor (ER) expression in distinctive hypothalamic loci, but information regarding potential adjustments in estradiol receptivity at the individual neuron population level remains incomplete. Estradiol controls glucostasis by action on ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMN) targets. VMN growth hormone-releasing hormone (Ghrh) neurons exhibit sex-dimorphic ER variant and counterregulatory transmitter gene profiles in young adult rats.

Combinatory single-cell laser-catapult-microdissection/multiplex qPCR analyses was used to investigate whether aging changes nuclear versus cytoplasmic ER gene expression according to sex.

Ghrh neuron ER-alpha and G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor-1 (GPER) transcription was decreased in old versus young rats of each sex. Old animals lacked ER-alpha transcriptional reactivity to hypoglycemia, indicative of age-associated loss of response. Hypoglycemia had divergent effects on ER-beta transcription, with no effect found in old males versus an inhibitory effect in old female rats. Hypoglycemic inhibition of Ghrh neuron GPER gene expression in old male and female rats was similar to that which occurred in corresponding young animals. Ghrh gene silencing identified age-related loss of neuropeptide modulatory regulation of ER gene transcription. Ghrh signaling inhibited eu- and hypoglycemic Ghrh neuron aromatase/CYP19A1 mRNA profiles in old male and female rats; in each sex, this gene transcript was refractory to hypoglycemia regardless of age.

VMN Ghrh neuron neuroestradiol production may be up-regulated with age, but cellular sensitivity to this local steroid signal may differ between young and old rats due to differences in ER variant expression. Further research is warranted to examine how potential age-associated modifications in absolute and proportionate signaling by distinctive ER may affect Ghrh neuron glucose-regulatory neurotransmission in male versus female rats.

Keywords

- estrogen receptor-alpha

- G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-1

- insulin-induced hypoglycemia

- Ghrh

- sex differences

The steroid hormone estradiol controls brain function by activating classical

nuclear [estrogen receptor-alpha (ER

Aging has broad-ranging effects on somatic and homeostatic bodily functions, including those governed by ER-regulated neural outflow [32, 33, 34, 35]. Indeed, the notion that aging may alter brain cell receptivity to estradiol has garnered ample, justifiable attention. Available studies provide valuable documentation of hypothalamic loci in which age-associated changes in ER expression occur [36, 37, 38, 39, 40]. Nevertheless, the unique cyto- and chemo-architectural heterogeneity of each structure accentuates the necessity for high-neuroanatomical resolution analytical techniques to determine if and how aging may affect estradiol receptivity of neurons of characterized functionality. Analysis of brain tissue samples corresponding to whole brain regions, nuclei, or areas poses a risk that averaged endpoint values may mask or obscure unique responses of individual neuron populations. Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a pervasive health concern in the elderly as acute and long-term complications of this condition exacerbate patient morbidity and mortality [41, 42, 43]. Older diabetic patients face an elevated risk of hypoglycemia-associated brain injury as counteractive hormone outflow and neurogenic awareness are impaired with age [44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49]. There is an obvious need to identify the mechanism(s) that elicits aging-related counterregulatory collapse. VMN structure is altered by aging in each sex [50]; yet it is unclear if or how age affects ER expression in VMN neurons that engage in neural regulation of glucose homeostasis, and if estradiol-induced changes in cellular function are responsible for these changes.

The VMN functions to assimilate metabolic, hormonal, and neurotransmitter cues

to shape glucose counterregulatory responses. Recent studies suggest that

estradiol-sensitive dorsomedial VMN (VMNdm) growth hormone-releasing hormone

(Ghrh) neurons are a common substrate for these diverse regulatory stimuli. Our

work shows that this nerve cell type expresses mRNA that encodes the

VMN-exclusive [51, 52] metabolic transcription factor steroidogenic factor-1

(SF-1) [53], which is implicated in regulation of systemic energy and glucose

balance [54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59]. In addition, SF-1 gene expression displays a differential

response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia (IIH) [60]. VMNdm Ghrh neurons also

express hypoglycemia-responsive genes that encode metabolic-sensory biomarkers

(i.e., the glucose sensor glucokinase and catalytic subunit of the

ultra-sensitive energy sensor 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase [61]) and, in

addition to Ghrh mRNA, transcripts for biosynthetic enzyme surrogates of

characterized counterregulatory-constraining (

Developmental organization of the sex-dimorphic VMN results in sex-specific

estradiol regulation of VMN functions. VMNdm Ghrh neurons from young adult male

and female express ER

Central ERs are activated by ligand that is synthesized in the ovary or within the brain, where testosterone is metabolized to neuroestradiol by aromatase (CYP19A1) enzyme action [63, 64]. A small number of neural structures, including the VMN, are characterized by relatively high CYP19A1 gene and protein expression and enzyme activity profiles compared to other brain loci [65, 66, 67, 68, 69]. A recent study provides evidence to infer that VMN neuroestradiol influences neural governance of glucose counterregulation [70]. The cellular source(s) of neuroestradiol produced in the VMN or elsewhere remains to be characterized. The present study investigated the corollary hypothesis that VMNdm Ghrh neurons express CYP19A1, the gene that encodes CYP19A1 protein, and that eu- and/or hypoglycemia-associated transcription of this gene may be affected by age in one or both sexes.

Young adult (2–3 months of age) and old (11–12 months of age) male and female Sprague Dawley rats were accommodated communally by sex in shoe-box cages (2–3 animals per cage), under a 14-hr light: 10-hr dark cycle (lights on at 05.00 hr). Animals were habituated to daily handling before initiation of study procedures and had ad-libitum access to standard laboratory chow (prod. no. Harlan Teklad LM-485; Harlan Industries, Madison, WI, USA) and tap water. Study protocols and procedures were performed in compliance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition, under approval of the university Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

On Study Day 1, old rats of each sex were randomly assigned to four treatment groups (n = 4 animals/sex/treatment group). Young male (n = 4) and female (n = 4) rats were designated as age-associated controls. Animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 9.0 mg ketamine (056344, Covetrus North America, Dublin, OH, USA)/1.0 mg xylazine (061035, Covetrus North America)/0.1 mL/100 g bw before infusion of Ghrh siRNA (500 pmol; Accell siRNA rat Ghrh, set of 4; A-089046-16-0010; Horizon, Cambridge, UK) or scramble (SCR) siRNA (500 pmol; Accell Control Pool Non-Targeting; D-001910-10-20; Horizon) to the bilateral VMN (coordinates: –2.5 mm posterior to bregma, 0.6 mm lateral to midline, 9.0 mm ventral to skull surface), in a 1.0 µL total volume at a 3.6 µL/min infusion rate; as described [60]. Injections were made using a 33-gauge Neuros syringe (53496; Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL, USA), under Neurostar stereotactic Drill & Injection Robot computer control (Neurostar, Tubingen, Germany). This genetic manipulation results in significant suppression of VMNdm Ghrh nerve cell Ghrh mRNA and protein [60]. Post-surgical treatments included subcutaneous(sc) ketophen (738764, Zoetis Inc., Kalamazoo, MI, USA) and IM enrofloxacin (00724089018656, Bayer HealthCare LLC, Animal Health Division, Shawnee Mission, KS, USA) injections and topical 0.5% bupivacaine (0409-1163-18, Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) application to closed incisions. Upon full recovery from anesthesia, animals were transferred to single-occupancy cages. On Study Day 7, male and female rats received a sc injection with vehicle (V; sterile diluent; Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, IN, USA) or neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin (INS; 10.0 U/kg bw; Eli Lilly & Co. [71]) at 09.00 hr; animals were sacrificed one hr post-injection by rapid decapitation. Individual whole brains were dissected for snap-freezing achieved by immersion in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane and storage at –80 °C.

Consecutive 10 µm-thick fresh-frozen tissue sections of the VMN were collected between –1.80 to –2.3 mm posterior to bregma and mounted on polyethylene naphthalate membrane-coated slides (415190-9041-000; Carl Zeiss Microscopy LLC, White Plains, NY, USA). Serial sectioning of each brain was initiated rostral to the retrochiasmatic area, at the approximate level of the optic chiasm, and continued until the VMN was reached; sections then cut through the rostral VMN were processed to acquire pure Ghrh nerve cell samples by in situ immunocytochemistry/laser-catapult microdissection for gene expression analysis. Several distinctive neuro-topographic features were used to verify the rostro-caudal progression of tissue sectioning, including continuity of the third ventricle with lateral ventricles, which occurs at the level of the suprachiasmatic nucleus; derivation of the lateral optic tracts from the midline optic chiasm; and rostro-caudal changes in curvature of the ventral surface of the hypothalamus. VMN sections were fixed with ice-cold acetone (5 min), then blocked (2 h) with 1.5% normal goat serum (S-1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.4, supplemented with 0.05% Triton X-100 (T8787, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Tissues were next incubated (48–72 h; 4 °C) with a rabbit primary antiserum against preproGhrh (PA5-102738, 1:2500; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), as described [60], followed by a goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (1 h; PI-1000, 1:1000; Vector Laboratories). Ghrh immunoreactivity (-ir) was manifested using ImmPACT 3,3′-diaminobenzidine peroxidase substrate kit reagents (SK-4105; Vector Laboratories). Ghrh-ir-positive neurons were individually isolated and removed from tissue sections using a Zeiss P.A.L.M. UV-A microlaser IV system ( Carl Zeiss Microscopy LLC), and collected into an adhesive cap (415190-9181-000; Carl Zeiss Microscopy LLC) holding lysis buffer (4 µL; Single Shot Cell Lysis Kit; 1725080; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) for single-cell multiplex quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis.

Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis and amplification: For each animal,

n = 3 Ghrh-ir neurons, the statistical unit in this study, were collected for

single-cell gene expression analysis. Thus, for each treatment group, a total of

N = 12 neurons was evaluated for male subjects and N = 12 neurons were analyzed

for female subjects. Individual cell lysates were centrifuged (3000 rpm; 4

°C; 5 min) before serial 25 °C (10 min) and 75 °C (5

min) incubations in a Bio-Rad iCyclerQ RT-PCR Detection System (170-8740;

Bio-Rad). Sample RNA quantity and purity were verified by

NanoDrop spectrophotometry (ND-ONE-W, Thermo Fisher Scientific

(ThermoFisherSci.), Waltham, MA, USA). Single-cell mRNA was reverse-transcribed

to cDNA by addition of 1.5 µL iScript™ Advanced cDNA

Synthesis Kit buffer (1725038; Bio-Rad), followed by 46 °C incubation

(20 min) and 95 °C denaturation (1 min), as previously described in

detail [72, 73, 74]. Pre-amplification master mix was prepared by combining

SsoAdvanced™ Pre-Amp Supermix (1725160; Bio-Rad) with individual

target and housekeeping gene Bio-Rad PrimePCR™ PreAmp for SYBR

Green Assays [ERalpha (ER

Mean normalized mRNA values for old male and female rats were analyzed by

three-way ANOVA and Student Newman Keuls post-hoc test. Data from young

SCR siRNA/V versus old SCR siRNA/V control groups were evaluated by t

test. Differences of p

Aging has documented effects on net ER variant mRNA and/protein content in distinct hypothalamic loci but understanding of how age may impact estradiol sensitivity of neurons that operate within the glucostatic neural circuitry is lacking. VMNdm Ghrh neurons likely function to integrate metabolic, endocrine, and neurochemical regulatory cues to shape counterregulatory neurotransmission. Here, single-cell laser-catapult-microdissection/multiplex qPCR analytical tools were applied to investigate whether aging perturbs, in one or both sexes, the magnitude and/or proportional expression of VMNdm Ghrh neuron ER variant mRNAs during eu- or hypoglycemia. Current research also examined the prospect that Ghrh neuromodulatory regulation of VMNdm Ghrh nerve cell ER gene transcription may change with aging in male and/or female rats using stereotactic delivery of in vivo Ghrh gene silencing tools.

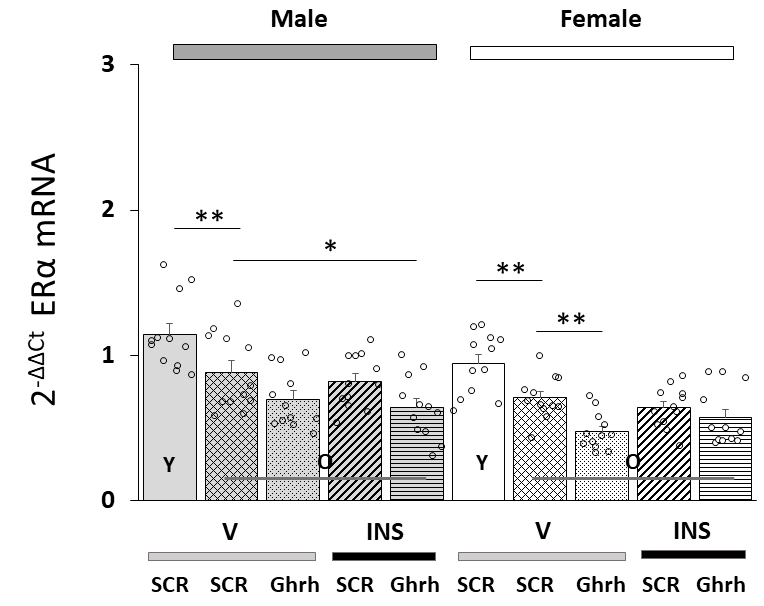

Fig. 1 (Ref. [75]) illustrates effects of VMN Ghrh gene silencing on VMNdm Ghrh nerve cell

ER

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Effects of ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMN) growth

hormone-releasing hormone (Ghrh) gene knockdown on total estrogen receptor-alpha

(ER

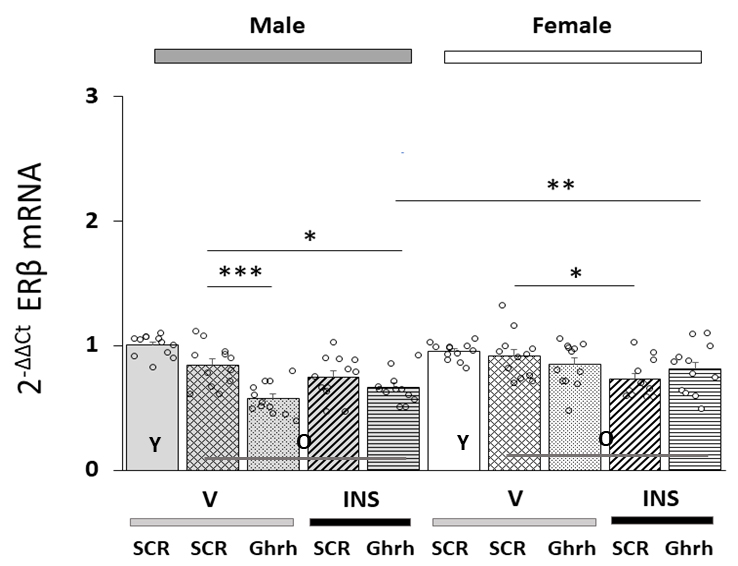

Data in Fig. 2 depict patterns of ER

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Patterns of VMNdm Ghrh neuron estrogen receptor-beta

(ER

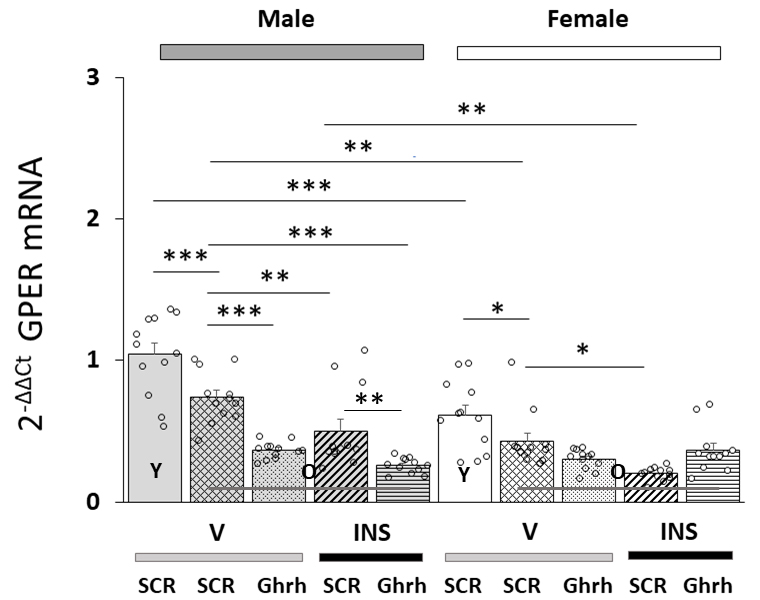

Fig. 3 shows effects of VMN Ghrh siRNA administration on VMNdm Ghrh nerve cell

GPER gene expression in eu- or hypoglycemia old male versus female rats. Data

indicate that in each sex, baseline GPER mRNA content was significantly lower in

old versus young animals [F(7,88) = 22.84, p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effects of VMN Ghrh Gene Silencing on Eu- and Hypoglycemic

Patterns of VMNdm Ghrh neuron G-protein-coupled-estrogen receptor-1 (GPER/GRP31)

mRNA expression in old male versus female rats. Data show mean total GPER mRNA

values + S.E.M. for male (five bars, at left) and female (five bars,

at right) rat treatment groups. Old rat treatment groups, indicated by

the abbreviation ‘O’, are identified as follows: SCR siRNA/V (cross-hatched bars;

male: gray, n = 12; female: white, n = 1); Ghrh siRNA/V (stippled bars; male:

gray, n = 12; female: white, n = 12); SCR siRNA/INS (diagonal-striped bars; male:

gray, n = 12; female: white, n = 12); Ghrh siRNA/INS (horizontal-striped bars;

male: gray, n = 12; female: white, n = 12). Young male and female treatment

groups, indicated by the abbreviation ‘Y’, are represented by solid gray (n = 12)

or white (n = 12) bars respectively. For each panel, circles depict individual

independent data points. Normalized mRNA data were analyzed between old rat

treatment groups by three-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc

test. Data from young SCR siRNA/V versus old SCR siRNA/V control groups were

evaluated by t test. Statistical differences between discrete pairs of treatment

groups are denoted as follows: *p

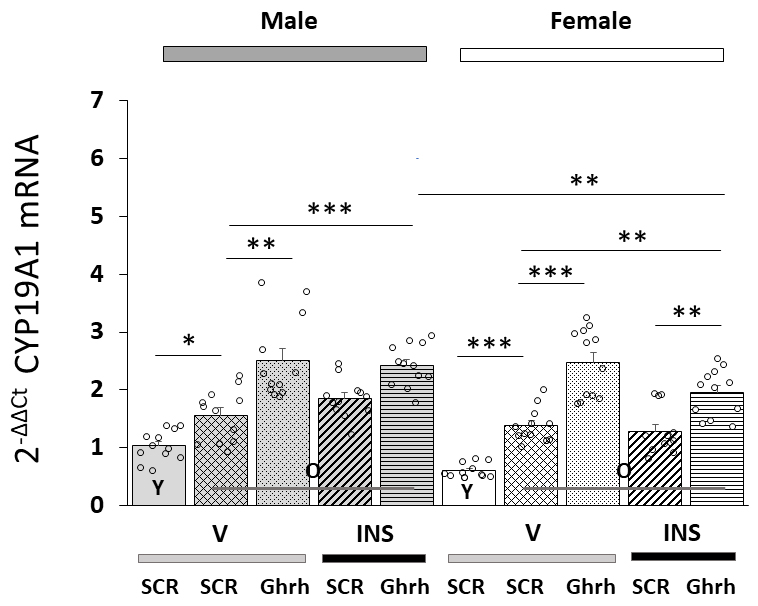

Patterns of VMNdm Ghrh nerve cell CYP19A1 gene expression in Ghrh versus SCR

siRNA-pretreated, eu- or hypoglycemic old male and female rats are shown in Fig. 4. Data indicate that this gene profile was significantly up-regulated in old

versus young animals of each sex [F(7,88)= 25.39, p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

VMNdm Ghrh neuron aromatase

(CYP19A1)

gene expression in old male versus female rat VMNdm Ghrh neurons. Data depict

mean total CYP19A1 mRNA values

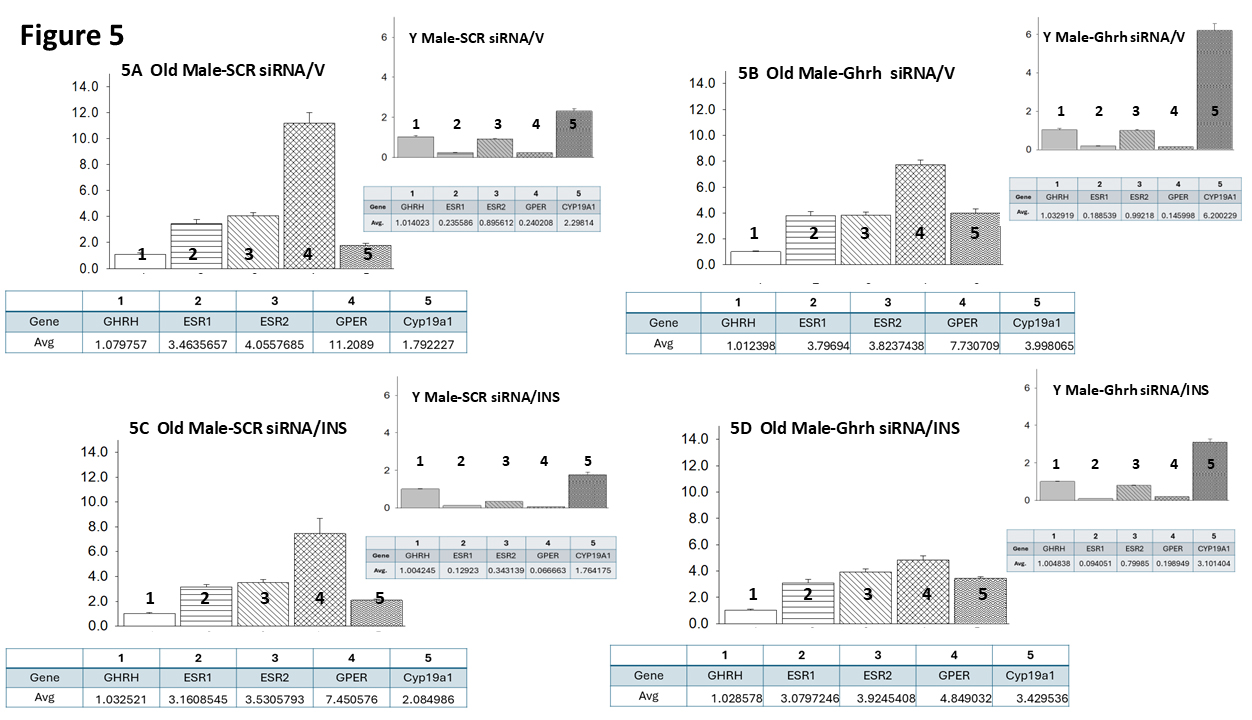

Fig. 5 (Ref. [60]) presents VMNdm Ghrh neuron ER variant and CYP19A1 gene

expression ratios for SCR versus Ghrh siRNA-pretreated sc V- (Fig. 5A,B)

or INS- (Fig. 5C,D) injected old male rats. Each panel shows average ratios of

individual target genes, identified by number, versus Ghrh mRNA; ratio values are

depicted in graphical (above) and tabular (below) formats. An insert figure in

the upper right-hand corner of each panel illustrates expression ratios for VMNdm

Ghrh neuron target genes for comparable young male rat treatment groups. Data in

Fig. 5A show that under euglycemic conditions, this nerve cell type exhibits

differential magnitude of ER variant gene transcription, as indicated by

dissimilar average ratio values, with GPER gene expression evidently

predominating compared to nuclear ER gene profiles. This gene ratio reflects a

change in proportionate transcription from young animals which are characterized

by higher relative ER

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Mean ER variant and CYP19A1 mRNA relative expression ratios for eu- and hypoglycemic old male rat VMNdm Ghrh/SF-1 neurons. Multiplex single-cell qPCR data acquired from laser-catapult-microdissected Ghrh–ir neurons here were used to establish mean ratios for target gene expression levels relative to Ghrh mRNA. Averaged ratio values were derived from n = 12 laser-catapult-microdissected VMNdm Ghrh-ir neurons from old male rats treated as follows: SCR siRNA/V (A), Ghrh siRNA/V (B), SCR siRNA/INS (C), Ghrh siRNA/INS (D). In each figure panel, mean relative gene expression data are depicted in graphical (above; bars with accompanying S.E.M.) and tabular (below; top row: gene name; bottom row: average proportionate expression ratio value) formats. The insert to each panel depicts proportionate expression of ER variant and CYP19A1 transcripts relative to Ghrh in young male rats; these data were mined from the data set from which information on Ghrh gene knockdown effect on absolute target gene expression in young rats was previously reported [60].

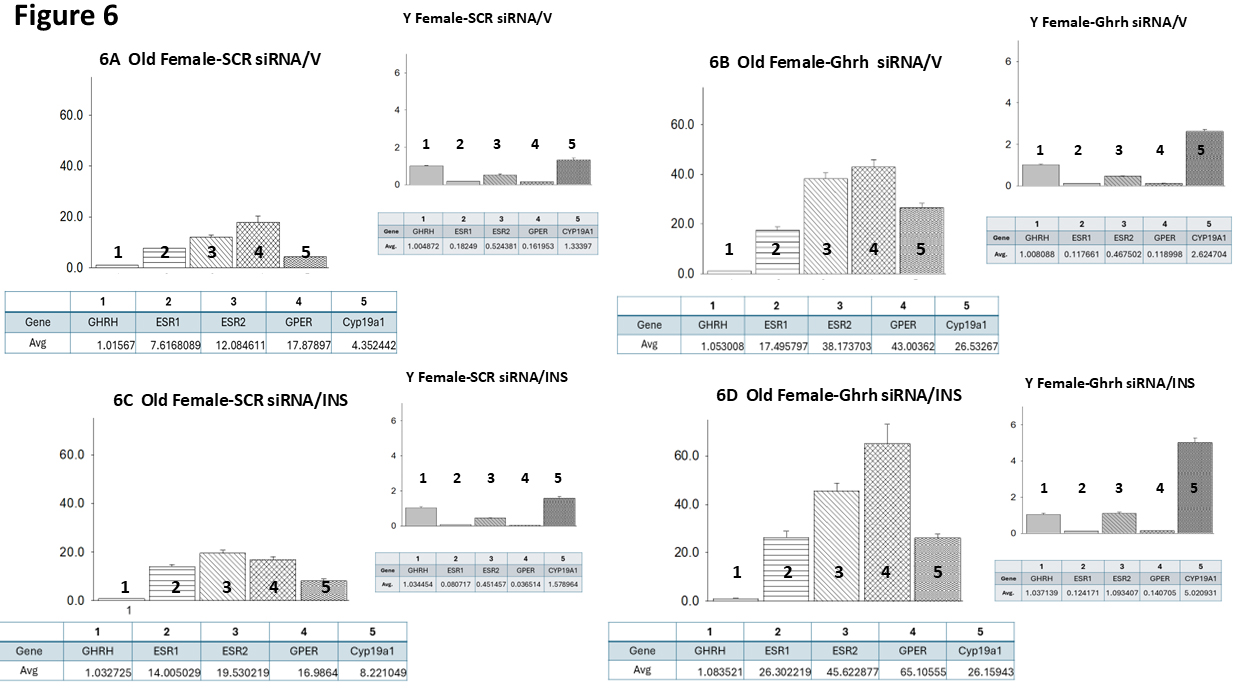

Data shown in Fig. 6 (Ref. [60]) illustrate target gene versus Ghrh mRNA ratios

in VMNdm Ghrh/SF-1 neurons from SCR siRNA/V (Fig. 6A), Ghrh siRNA/V (Fig. 6B),

SCR siRNA/INS (Fig. 6C) and Ghrh siRNA/INS (Fig. 6D) old female rats. Like old

males, euglycemic old female rats exhibit divergent target gene expression

relative to Ghrh, with GPER mRNA expressed at the higher proportion. However, in

young females, as in young males, ER

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Mean ER variant and CYP19A1 mRNA relative expression ratios for eu- and hypoglycemic old female rat VMNdm Ghrh/SF-1 neurons. Multiplex single-cell qPCR data acquired from laser-catapult-microdissected Ghrh–ir neurons here were used to establish mean ratios for target gene expression levels relative to Ghrh mRNA. Averaged ratio values were derived from n = 12 laser-catapult-microdissected VMNdm Ghrh-ir neurons from old female animals grouped as follows: SCR siRNA/V (A), Ghrh siRNA/V (B), SCR siRNA/INS (C), Ghrh siRNA/INS (D). In each figure panel, mean relative gene expression data are depicted in graphical (above; bars with accompanying S.E.M.) and tabular (below; top row: gene name; bottom row: average proportionate expression ratio value) formats. The insert to each panel depicts relative ER variant and CYP19A1 transcripts compared to Ghrh mRNA in young female rats; these data were mined from the data set from which information on Ghrh gene knockdown effect on absolute target gene expression in young female rats was previously reported [60].

Estradiol regulation of brain function requires insight into how normal- and patho-physiological processes affect brain cell sensitivity to this hormone signal. Aging is a natural, continuous process of change that affects all organ systems, including the brain, and purportedly alters ER variant gene and/or protein profiles in distinct brain regions or nuclei. The phenotypic and operational heterogeneity of cells that comprise these notable structures bolsters the need for continuing work to discern how aging affects ER expression in resident cell populations of known function. Current research illustrates the utility of multiplex qPCR technology, namely the capability for quantification of absolute and proportional expression profiles of diverse receptor targets for this hormone signal at the single-cell level, for research on the aging brain.

A Study has reported here examined how aging may affect ER variant gene expression

in VMNdm Ghrh neurons appear to provide a complex, multi-modal neurochemical

input to the counterregulatory neural network [60]. Present research also

addressed the correlated premise that characteristic sex differences in ER

transcription patterns in young animals may be likewise impacted by age. Results

here document, for each sex, age-related absolute reductions in Ghrh neuron

ER

It is worthwhile considering that evidence for age-associated alterations in ER gene expression described here does not serve as conclusive confirmation that corresponding gene protein product production is likewise changed in a similar direction and magnitude. The plausible assumption that aging may elicit tandem adjustments ER gene versus protein expression under baseline and/or hypoglycemic conditions, will require application of proteomic analysis methods of requisite sensitivity for quantification of ER protein levels in single brain cell samples.

Administration of Ghrh siRNA to the old male rat VMN disclosed a loss of Ghrh

neuromodulatory stimulation of VMNdm Ghrh nerve cell ER

Co-expression of nuclear and membrane ER variants enables integrative estradiol

regulation of VMNdm Ghrh neuron function [76, 77, 78]. It is well documented that the

nuclear transcription factors ER

Synchronized quantification of individual target gene profiles by multiplex qPCR

analysis is a valuable tool for evaluation of relative expression of diverse ER

transcripts within a common cellular source. Here, compilation of relative

ER

Data here show that IIH reduced proportionate GPER gene expression in old male

rats, i.e., SCR siRNA/INS versus SCR siRNA/V treatment groups, without major

effects on other ER variant mRNAs. This represents a change from young male rats,

which exhibit pronounced down-regulated proportionate ER

The continuum of development over the male or female lifespan involves transition between distinct reproductive states, including reproductive senescence, which are typified by unique gonadal steroid hormone secretion patterns. Current findings show that VMNdm Ghrh neuron neuroestradiol production is also apparently age sensitive as CYP19A1 gene profiles are enhanced in old versus young rats of either sex. As noted above, further experimentation is required to verify that aging amplifies CYP19A1 protein and enzyme activity profiles in this neuron population in each sex. Interestingly, eu- and hypoglycemic patterns of CYP19A1 transcription are each up-regulated in response to VMN Ghrh gene silencing, which strongly suggests that this neuropeptide transmitter imposes a negative, inhibitory tone on this mRNA profile in each sex. The literature, as ably summarized by Cruz et al. [91], documents a progressive decline in female rat fertility between the ages of 8 to 12 months, characterized by reduced numbers of developing ovarian follicles and corpora lutea alongside increasing perturbances in estrous cyclicity, such as increased length, and development of constant estrous. Constant estrous, which occurs at 10 months and onward, is typified by low, unvarying circulating estradiol, estrone, testosterone, and progesterone levels, and an increase in estradiol/progesterone ratio. Female rats 12 months of age or older are reported to lack corpora lutea, a sign of absence of ovulation. While it is presumed that female subjects of similar age used in current work exhibited the attributes described above, the lack of direct verification of that supposition is a limitation. It is noted that potential changes in ovarian-derived estradiol signal volume to the aging female rat brain apparently coincide with possible augmentation of locally-generated neuroestradiol, as discussed above. Clearly, further studies are needed to quantify effects of age in both sex on net VMN tissue estradiol concentrations.

VMN is a known substrate for estradiol regulation of glucose homeostasis.

Current work used combinative single-cell

laser-catapult-microdissection/multiplex qPCR tools to establish if and how aging

affects total and proportional VMN counterregulatory neuron ER variant gene

expression in each sex. Results indicate that aging affects absolute ER

CYP19A1, aromatase; ER

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

RS: conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, validation, data curation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization; SS: investigation, formal analysis, validation, data curation; KPB: conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All animal experimentation was carried out in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition, as stated in the submitted manuscript. Study protocols and methods were approved by the University of Louisiana Monroe Institutional Committee on Animal Care and Use, Approval number 24NOV-KPB-01. Sex of animals used is included, along with discussion of sex impacts on study outcomes.

Not applicable.

This research was supported by NIH grant DK-109382.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.