1 College of Life Sciences and Medicine, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, 310018 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Research Center, Jiaxing University Affiliated Hospital, The First Hospital of Jiaxing, 314001 Jiaxing, Zhejiang, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Bone cancer pain (BCP) is a prevalent chronic pain condition and a common clinical symptom in patients with advanced cancer. It significantly affects the mobility and quality of life of patients; however, current treatments offer limited efficacy. Harmine, a beta-carboline alkaloid extracted from Peganum harmala, exhibits anti-inflammatory, anxiolytic, analgesic, and neuroprotective properties. However, its antinociceptive properties and mechanisms in BCP models remain unclear. This study aimed to systematically investigate the analgesic effects of Harmine in rats with BCP and explore its underlying molecular mechanisms.

Using databases such as SwissTargetPrediction and Polypharmacology Browser, molecular docking analysis, behavioral tests, and biochemical analysis, we comprehensively evaluated the effects of Harmine in the BCP model.

The results demonstrated that Harmine significantly alleviated BCP induced by Luciferin-Malignant Atypical Discrete Breast 106 cells (LUC-MADB106) in a dose-dependent manner. Intrathecal administration of Harmine significantly inhibited the upregulation of dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A (DYRK1A) expression and the activation of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway in the spinal cord dorsal horn (SCDH) of rats with bone cancer.

These findings suggest that Harmine has significant therapeutic potential for alleviating BCP hyperalgesia, providing a foundation for the future development of new drugs targeting BCP.

Keywords

- bone cancer pain

- Harmine

- DYRK1A/NF-κB signaling pathway

- spinal cord dorsal horn

Bone cancer pain (BCP) is chronic bone pain caused by malignant tumors in bone metastatic sites and is one of the most common clinical symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. Approximately 75% of patients with metastatic cancer experiencing moderate-to-severe BCP [1]. Despite the availability of various clinical methods [2, 3, 4], such as surgical treatment, radiotherapy, and interventional therapies, approximately 50% of pain symptoms in patients with metastatic cancer remain inadequately controlled, leading to significant physical and mental suffering and a severe decline in quality of life [5]. The effective control of cancer pain remains a major challenge in pain research [6]. Current treatments for BCP and other cancer-related pain primarily include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, and bisphosphonates. However, these drugs are often ineffective for moderate-to-severe cancer pain, fail to provide adequate pain relief, and are associated with issues such as safety concerns, addiction, drug tolerance, and severe adverse reactions and side effects [7, 8, 9, 10]. Therefore, there is a critical need to find safe and effective new drugs for BCP with minimal side effects and to conduct in-depth research into their mechanisms, which holds significant theoretical and clinical value.

Recent studies have identified several signaling pathways that mediate these

pathological processes, including the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer

of activated B cells (NF-

Harmine is a beta-carboline alkaloid extracted from Peganum harmala L. and is known for its pharmacological activities, including

anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, antitumor, and antibacterial properties [17].

Harmine has been used in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, such as

Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, primarily because of its ability to reduce

inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress while enhancing the activity of

mitochondrial respiratory complexes, thereby providing neuroprotection [18]. In

South America, Ayahuasca is commonly used to treat depression and anxiety, of

which Harmine is one of the main components [19]. A recent research has

demonstrated that Harmine can alleviate anxiety by inhibiting neuroinflammation

and restoring neuronal plasticity in the basolateral amygdala [20]. A recent

study has shown that Harmine can mitigate neurotoxicity in neurodegenerative

diseases by inhibiting DYRK1A [21]. Moreover, Harmine effectively suppresses

neuroinflammation by modulating the TLR4/NF-

This study aimed to investigate the therapeutic potential of Harmine in BCP treatment and demonstrate its underlying molecular mechanisms. Using a rat model of BCP, we evaluated the analgesic effects of Harmine using behavioral tests, bioluminescence imaging, and biochemical analyses. Our study provides new insights into the role of Harmine as a potential therapeutic agent for BCP and contributes to the identification of novel targets for the treatment of cancer-related pain.

Harmine (purity

Female Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 160–180 g, were obtained from the Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Company, Beijing, China. The rats were housed under controlled conditions, with four rats per cage. The rats were kept under a 12-h light/dark cycle (12:12 h) with free access to water and standard laboratory chow diet. Prior to the commencement of the study, the rats were acclimatized for a 2–5-day period to adjust to the experimental environment. All animal experiments were conducted between 8:00 AM and 8:00 PM to minimize stress in the experimental animals. These experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jiaxing University (Ethical Approval No. JUMC2021-093) and were conducted in strict adherence to the guidelines set forth by the International Association for the Study of Pain for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Lentivirus-infected Malignant Atypical Discrete Breast (MADB) 106 cells, which originated from the MADB 106 breast cancer cell line (Procell, Wuhan, China), were used to establish stable cell lines. These stable luciferase-expressing MADB 106 cells (LUC-MADB 106) were used for BCP modeling. All cell lines were validated to confirm their identities using species-specific PCR methods. Mycoplasma contamination was ruled out using a detection kit from EallBio (03.17012DB, Beijing, China), and negative results ensured the purity and quality of the cell lines used.

The BCP model was established as described in previous studies [27, 28]. All rats

involved in the experiment were randomly assigned to the sham operation group or

model group. Initially, the rats were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection

of 1% pentobarbital sodium solution (50 mg/kg). Once anesthetized, the rats were

positioned in the supine position, and a small hole was drilled into the tibial

plateau of the left hind limb of each rat. Using 25µl microsyringe (RonMark, Shanghai, China), either LUC-MADB

106 cells (10 µL, 1

Von Frey filaments (BME-404, produced by the Institute of Biological Sciences at

the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Yunnan, China) were used to assess mechanical

pain sensitivity in the experimental rats. These evaluations were performed on

the day before the BCP model establishment and on days 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18

after modeling. Prior to testing, the rats were acclimatized in a 20

Gait Analysis: We utilized the CatWalk gait analysis system, model ZS-BT/S, sourced from Beijing Zhongshi Science & Technology (Beijing, China), to assess the pain behavioral effects in two groups of rats: the sham surgery group and the model group. The rats were trained to walk through a closed channel, with the bottom section consisting of a glass plate. A fluorescent tube was positioned beneath the plate, casting green light onto the glass surface to allow for detailed tracking of the rats’ footprints and movement patterns. As the rats walked across the glass plate, their paws contacted the surface, reflecting green light, which enabled the capture of footprint images and the measurement of footprint intensity. Prior training was necessary to ensure that the rats could navigate the passage at a consistent and uninterrupted speed during the formal data collection phase. The following two key indicators were used to assess the impact of pain on rat behavior: (1) footprint area and (2) average footprint intensity. The data are expressed as the ratio of the left hindlimb to the right hindlimb, which helped mitigate the influence of confounding factors.

Open Field Test (OFT): The motor functions of the rats and the presence of

anxiety-like behavior were evaluated using the OFT. The rats were acclimated to

an open-field arena measuring 80

Light-Dark Shuttle Test (LDT): This test involves two equal-sized compartments: One illuminated with white walls (light box) and the other completely dark with black walls (dark box). A small door connected the two boxes, allowing the rats to move freely between them. Prior to the experiment, the rats were placed in a dark box for 5 min to acclimatize to the environment. After the acclimation period, the activity was monitored for another 5 min as the mice moved between the two compartments. Anxiety levels were evaluated by recording the time spent and distance traveled in a light box within a predetermined period.

Rotation Test: All rats underwent a 3-day training period, with each session lasting 3 min, prior to the formal experiment. At the beginning of the experiment, the rats were placed on a rotating rod, and the time each rat remained on the rod was measured, with a maximum duration of 3 min. Motor function was assessed by recording the amount of time each rat spent on the rod over a 3-minute interval. The results of the training sessions served as baselines for subsequent statistical analyses.

In vivo bioluminescence imaging was performed using an In Vivo Imaging System Lumina III (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Bioluminescence images were acquired on days 0.5, 6, 12, and 18 after BCP modeling. Prior to image acquisition, D-luciferin (Abs816138, Absin, Shanghai, China) was administered intraperitoneally, followed by 3-min inhalation of isoflurane anesthesia. Isoflurane was obtained from RWD Life Science (R510-22-10, anesthesia concentration of 2%, Shenzhen, China). Immediately after anesthesia, the rats were positioned supine in an imaging chamber for data acquisition. The intensity of the bioluminescent region was quantified as the radiance within the region of interest (ROI) and recorded after the imaging.

CT scanning was performed on left hind limb samples from both the Sham-operated and model groups on day 18. The acquisition parameters were as follows: Spiral scanning, tube voltage of 120 kVp, slice thickness of 1 mm, and slice spacing of 1 mm. The nucleus setting was U30u, which ensured medium smoothness and a high resolution. All images were processed and analyzed using the Syngo MultiModality Workplace (MMWP) software (2007A VE22A, Erlangen, Bavaria, Germany) provided by Siemens.

Twelve days post-modeling, rats from both the Sham-operated and model groups were euthanized using pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg). The left tibia was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (BL539A, Biosharp, Hefei, Anhui, China) for 24 h and decalcified in 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, ST066, Beyotime Biotechnology) for 24 h. Decalcified tibiae were paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Images were captured using a microscope (Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan) after sealing the sections with neutral resin.

Downstream proteins associated with Harmine were identified using the SwissTargetPrediction (http://swisstargetprediction.ch/) and Polypharmacology Browser (PPB) databases (https://webtools.gdb.tools/PPB/). To ensure species specificity, the filter was set to “Rattus norvegicus” for both searches. The datasets obtained from each database were thoroughly reviewed to identify Harmine-related downstream proteins while maintaining consistency in filtering criteria.

The 3D structure of Harmine was obtained from Public Chemical Database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and the

3D structures and sequences of DYRK1A (Q63470) and NF-

After anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), the rats were placed in a prone position on an electric heating blanket. A 1.5 cm longitudinal incision was made over the L4-L5 spinous processes, allowing muscle separation around the L4 vertebra. The L4 spinous process was resected to expose the vertebral interspaces. A Polyethylene-10 catheter (Combio, Jiangsu, China) was carefully inserted approximately 1 cm into the subarachnoid space and securely fixed. Successful insertion was confirmed by the presence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) reflux. To facilitate future experiments, the distal end of the catheter was subcutaneously tunneled to the back of the rat’s neck, where it was anchored and sealed to prevent CSF leakage. On the second day post-catheterization, further experiments were initiated if hindlimb weakness was observed following intrathecal injection (i.t.) of 2% lidocaine (10 µL, TCI-L0156, TCI AMERICA, Portland, OR, USA). Normal movement was expected to resume within 5 min.

Tissues from the lumbar enlargement of the rat SCDH were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (PC101, Beyotime Biotechnology) and homogenized using a tissue homogenizer. The total protein concentration in the supernatant was measured using a Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay Kit (ZJ101L, Epizyme Biotech, Shanghai, China). The extracted proteins were separated using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Following blocking with a rapid blocking solution (PS108P, Epizyme Biotech), the membranes were sequentially incubated with the primary antibody, followed by the secondary antibody. Antibody detection was performed using an enhanced chemiluminescence exposure solution (SQ201, Epizyme Biotech), with specific antibody details listed in Supplementary Material 1.

The results were analyzed in grayscale using ImageJ software (1.4.3.67, Wayne Rasband, Bethesda, MD, USA), and the relative expression levels of the target proteins were

quantified by dividing the grayscale values of the target protein bands by those

of

Total Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) was extracted from the lumbar enlargement of the

rat SCDH using TRIzol (15596018CN, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA concentration was

measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A reverse transcription kit (RR037A, Takara, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan) was used to convert 1000 ng of RNA into complementary Deoxyribonucleic

Acid (DNA). The qPCR was performed using the SYBR Green method with primers

designed and synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Primer sequences

are provided in Supplementary Material 2. Messenger RNA (mRNA)

expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method,

with data normalized to

The expression levels of pro-inflammatory factors in the lumbar enlargement of the rat spinal cord were measured using an ELISA kit (EK301B/4, EK306/3, EK382/3, LIANKEBIO, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China). Optical density (OD) values were recorded at 450 and 630 nm according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Calibrated OD values were obtained by subtracting the 570 nm readings from the 450 nm readings. A standard curve was generated to determine the concentrations of pro-inflammatory factors in the tissue.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0, GraphPad Software, Inc., San

Diego, CA, USA), and the data are presented as mean

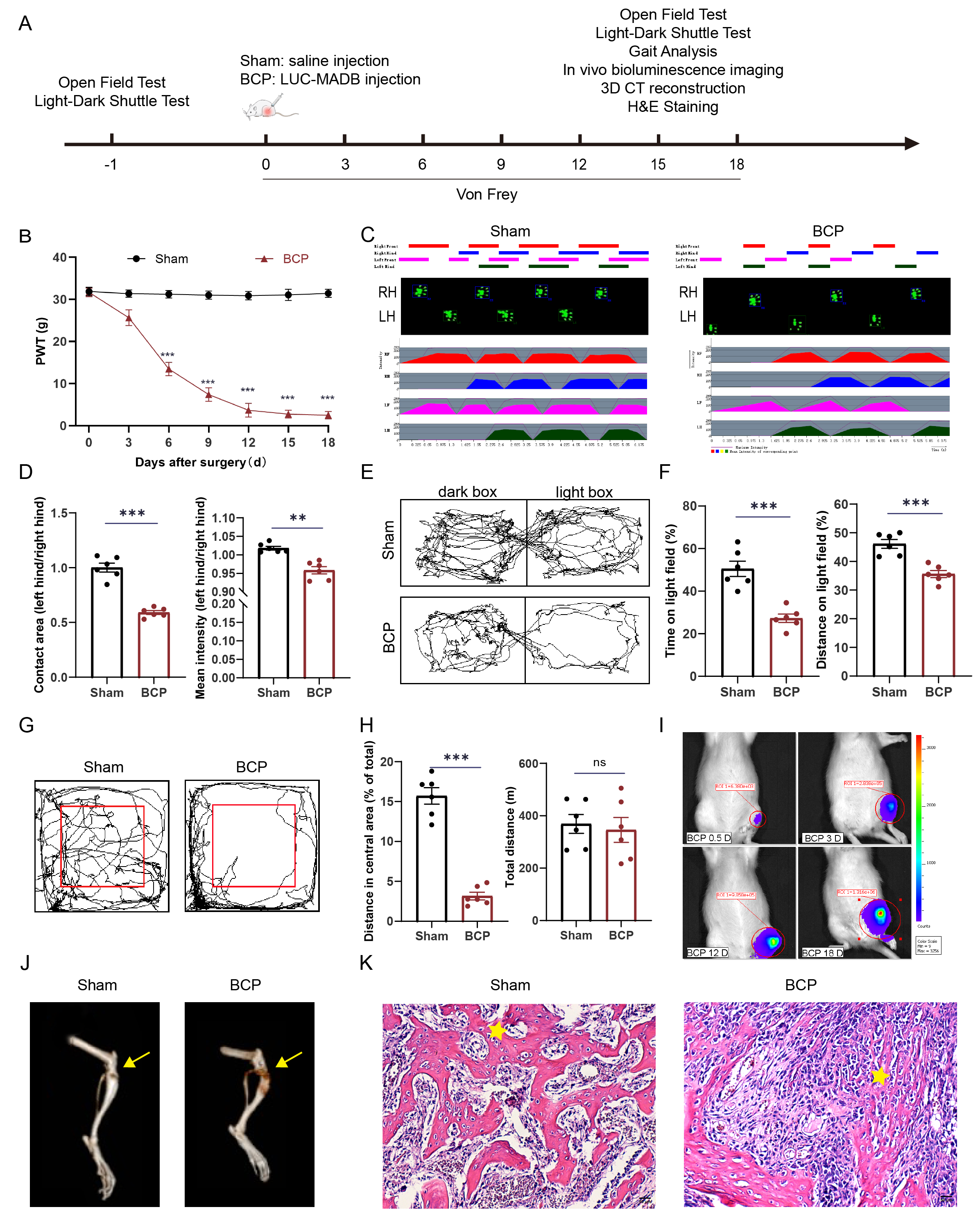

To confirm the successful establishment of the BCP model, we performed a thorough evaluation of rats in both the Sham and BCP groups, assessing their paw pain thresholds, motor function, and pain-related emotional behaviors. The specific experimental procedures are shown in Fig. 1A. Pain thresholds were measured using the Von Frey test. The results revealed a significant reduction in pain thresholds in the BCP group by day 6 compared to the Sham group, with this reduction stabilizing by day 12 (Fig. 1B). Gait analysis indicated that limb motor function remained intact in both groups; however, the footprint area and average pressure of the left hind paw were significantly reduced in the BCP group (Fig. 1C,D). Light-dark shuttle box experiments demonstrated that the BCP group spent less time in the light box and covered a shorter distance than the Sham group (Fig. 1E,F). OFT results indicated no significant difference in the total distance traveled between the two groups during the first 5 min of movement. However, the BCP group exhibited a greater tendency to walk along the walls of the box, with significantly reduced distance traveled in the central area and diminished exploratory behavior compared to the Sham group (Fig. 1G,H). These behavioral experiments demonstrated that the modeled rats developed heightened pain sensitivity and negative emotional behaviors related to their pain perception. Fluorescence in vivo imaging revealed a progressive enhancement of fluorescence signals in rats following BCP modeling (Fig. 1I). 3D CT scans indicated that the BCP group rats exhibited damage to the tibial plateau compared to the Sham group, revealing severe bone destruction (Fig. 1J). H&E staining results from tibial plateau slices indicated that compared to the Sham group, the morphology of bone trabeculae in the BCP group was altered, with significant tumor cell invasion (Fig. 1K). In summary, these experiments confirmed that tumor cells infiltrated the bone marrow cavity and proliferated extensively, leading to bone destruction and pain. Additionally, the morphological analyses also validated the successful establishment of the BCP animal model.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

BCP modeling. (A) The experimental procedures. Figure A was drawn using Adobe Illustrator 2021 software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, Ca, USA). (B) The

mechanical pain threshold results demonstrated that the paw pain threshold of the

rats progressively decreased from days 6 to 18 (n = 6). (C,D) Gait analysis

revealed a decrease in the footprint area and mean pressure in the left hind limb

in the BCP group (n = 6). LH: Left hind limb; and RH: Right hind limb. (E,F) LDT

results demonstrated that the modeled group exhibited significantly reduced time

and traveled a shorter distance in the bright compartment (n = 6). (G,H) The OFT

revealed a significant reduction in the distance traveled by the modeled rats in

the central region (n = 6). (I) Bioluminescence in vivo imaging revealed

that following cell inoculation, the model group demonstrated cell proliferation

in the tibial plateau (n = 6). (J) 3D CT images revealed extensive bone damage in

the tibial plateau following model establishment, and the yellow arrows indicate

the sites where cells or saline were injected during model establishment (n = 6).

(K) H&E staining revealed well-preserved bone trabecular structures (indicated

by pentagrams) in the Sham group, whereas in the BCP group, the bone trabecular

structures exhibited significant deterioration, with extensive tumor cell

infiltration observed in the bone marrow cavity (n = 6). Scale bar: 50 µm.

**p

To evaluate the efficacy of Harmine in alleviating pain in rats with BCP, varying concentrations of Harmine solution (6.25, 25, 100, 400, and 1600 µg/kg) were administered via intrathecal injection daily from days 8 to 12 post-modeling. Behavioral assessments were then performed (Fig. 2A). Log (dose)-response curves were generated based on different concentrations of Harmine (Fig. 2B), and log (dose)-response curves were plotted, leading to the calculation of the half-effective dose (ED50) of 72.50 µg/kg (Fig. 2C). Behavioral assays were conducted to explore the pain-relieving effects of Harmine on BCP. The results revealed that administering Harmine at doses of 25, 100, and 400 µg/kg led to a progressive increase in the pain thresholds of the rats, demonstrating both time- and dose-dependent effects. Notably, the pain thresholds in the group receiving the 400 µg/kg intrathecal injection of Harmine demonstrated significant restoration, with the analgesic effect persisting even after the cessation of Harmine administration (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Behavioral effects of intrathecal Harmine injection in rats with

BCP. (A) Schematic timeline of animal experiments. Figure A was drawn using Adobe Illustrator 2021 software. (B,C) Dose-response and log

(dose)-response curves of the analgesic effect following intrathecal injection of

Harmine indicated that the ED50 for pain relief in rats with BCP was 72.50

µg/kg. (D) Intrathecal injection of Harmine relieved pain in rats with BCP

in a dose- and time-dependent manner (n = 6). (E) Effect of a single injection of

varying concentrations of Harmine on mechanical pain thresholds in rats with BCP

was evaluated 12 days postoperatively. The analgesic effect peaked at 4 h

post-injection and was sustained for up to 8 h (n = 6). (F,G) Gait analysis

indicated changes in the footprint area and mean pressure on the left hind limb

in the model group compared to the Harmine-treated group (n = 6). (H,I) The

light-dark shuttle box experiment revealed differences in both the duration spent

and distance covered in the bright box between the two groups (n = 6). (J,K) Open

field experiments revealed changes in the total distance covered and the distance

traveled in the central area, with the model group reporting significant

differences compared to the Harmine-treated group (n = 6). (L) Rotarod test to

assess the impact of different concentrations of Harmine on the motor performance

of rats with BCP (n = 6). *p

The onset and duration of the action of Harmine were further investigated through a single administration on the 12th day post-modeling. The 25 µg/kg Harmine group did not exhibit a significant therapeutic effect on the pain thresholds of rats after this single administration. In contrast, the 100 and 400 µg/kg Harmine groups demonstrated an onset of effect 2 h after injection, with the drug’s effect peaking at 4 h and maintaining efficacy until 8 h post-administration. The pain thresholds of the rats exhibited a dose-dependent increase that was sustained for 8 h (Fig. 2E). Additionally, the pain-relieving effects of Harmine on spontaneous pain in rats with BCP were assessed using gait analysis. The findings revealed that 12 days post-surgery, the Harmine-treated group (400 µg/kg, i.t.) demonstrated significant improvement in key indicators of the left hind paw (Fig. 2F,G). To evaluate whether Harmine alleviates BCP-induced negative emotional behaviors associated with pain, we performed the LDT. The results indicated that compared with the BCP + Vehicle (Veh) group, the Harmine-treated group (400 µg/kg, i.t.) showed a marked rise in both the time in the light box and traveled a greater distance (Fig. 2H,I). Furthermore, exploratory activity of BCP rats was assessed using the OFT, which revealed that rats in the Harmine-treated group exhibited increased time in the central area compared to the BCP + Veh group (Fig. 2J,K). Collectively, these experiments demonstrated that Harmine alleviated BCP-induced nociceptive hypersensitivity and reduced pain-related negative emotional behaviors. Notably, the results of the rotarod test confirmed that intrathecal injection of Harmine did not impair motor function in rats, thereby demonstrating its safety (Fig. 2L).

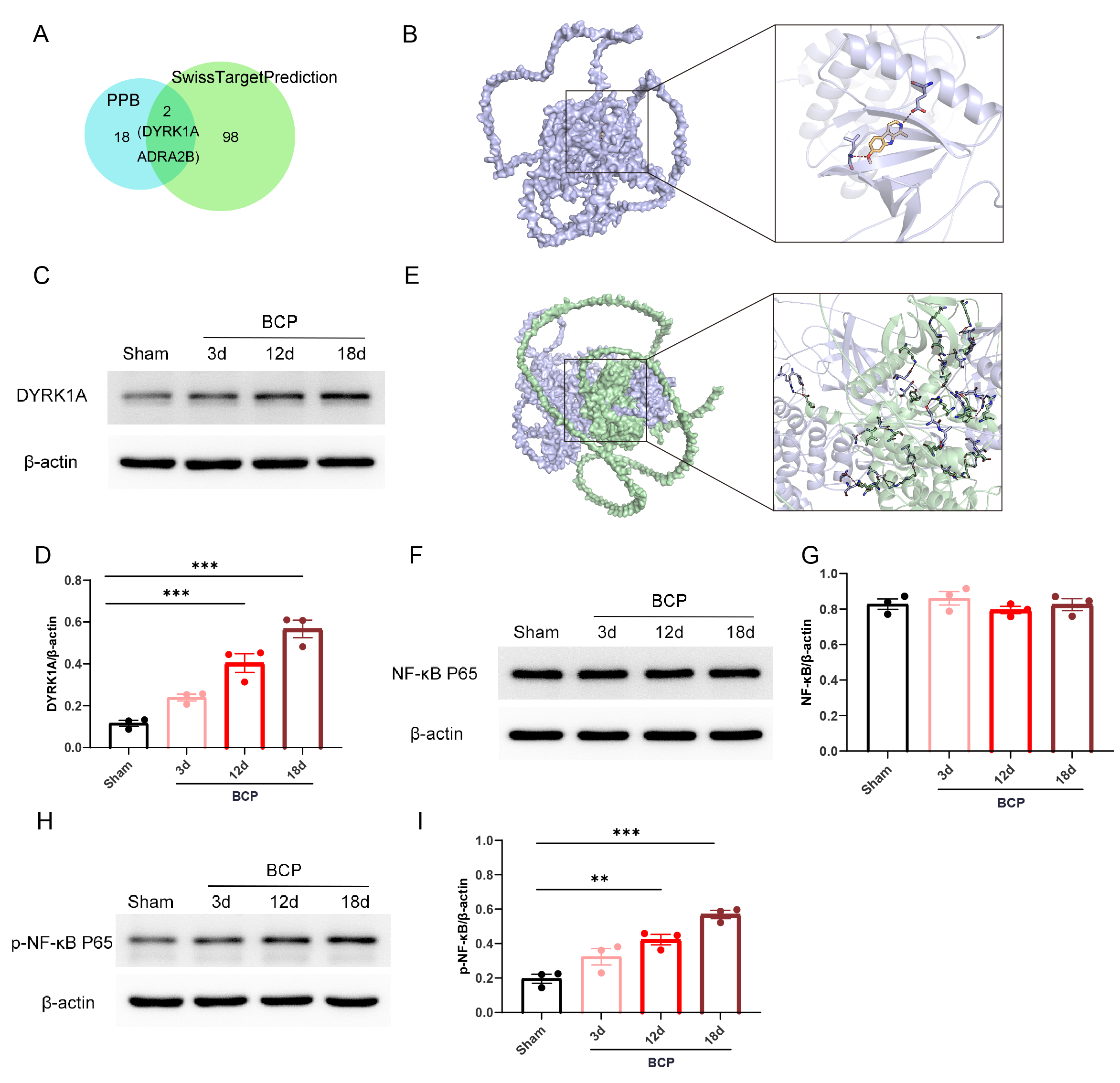

The downstream proteins of Harmine were identified using the

SwissTargetPrediction and PPB databases, which led to the identification of

common proteins, specifically DYRK1A and Adrenoceptor Alpha 2B (ADRA2B) (Fig. 3A). Previous studies have indicated that central neuroinflammatory mechanisms

play a critical role in BCP pathogenesis [29, 30]. Consequently, we selected

DYRK1A, known for its anti-inflammatory properties and anxiolytic effects, as the

downstream protein of Harmine for further investigation. To validate these

predictions, molecular docking studies were performed, which revealed hydrogen

bonding between Harmine and DYRK1A, indicating a moderate binding affinity (Fig. 3B). Further analysis of DYRK1A protein levels in the SCDH of rats with BCP

further demonstrated a time-dependent upregulation of expression (Fig. 3C,D).

Additionally, considering that DYRK1A has been shown to facilitate the activation

of NF-

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effects of bone cancer on the DYRK1A/NF-

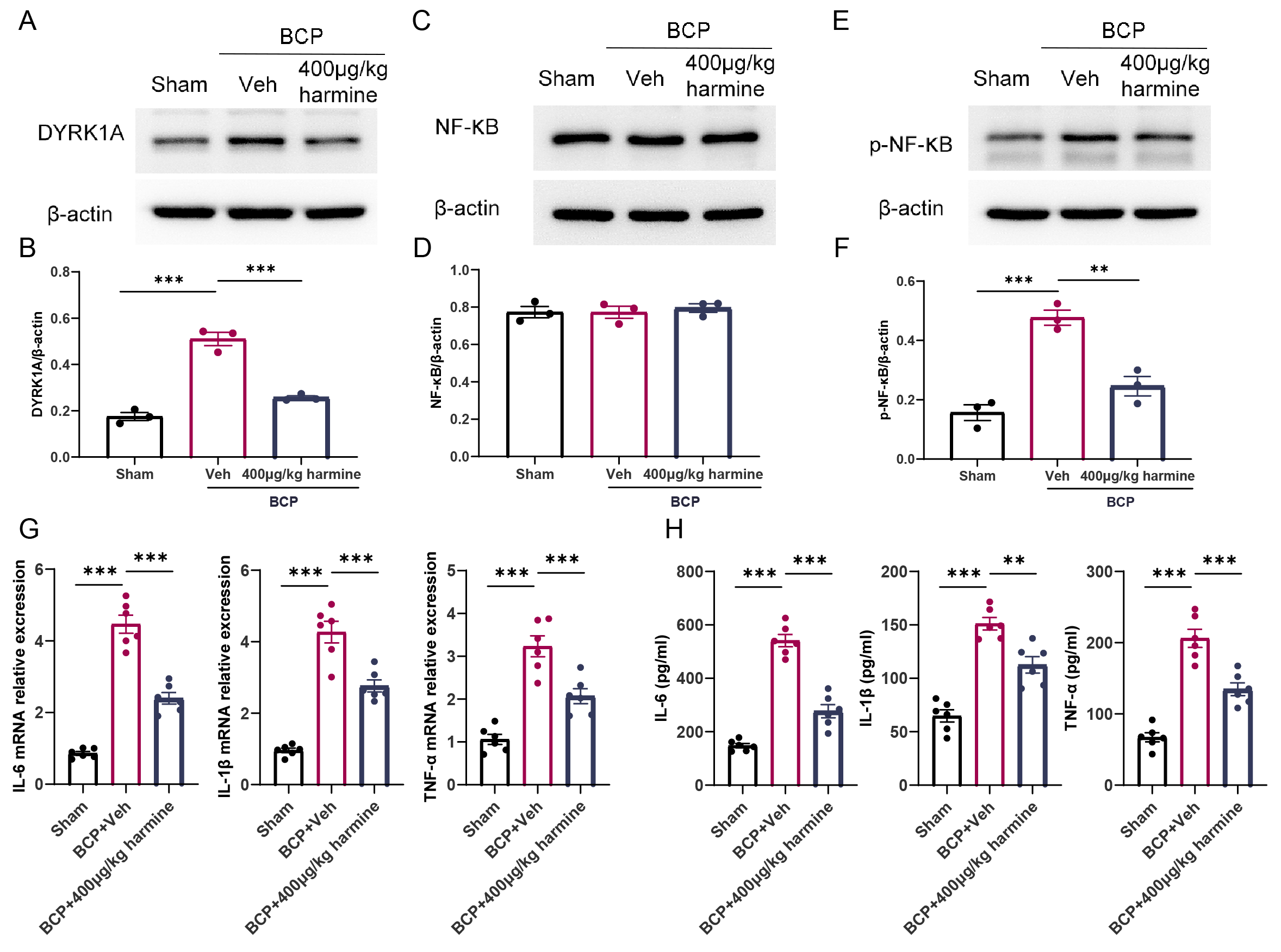

To verify that Harmine regulates the DYRK1A/NF-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Harmine modulates the DYRK1A/NF-

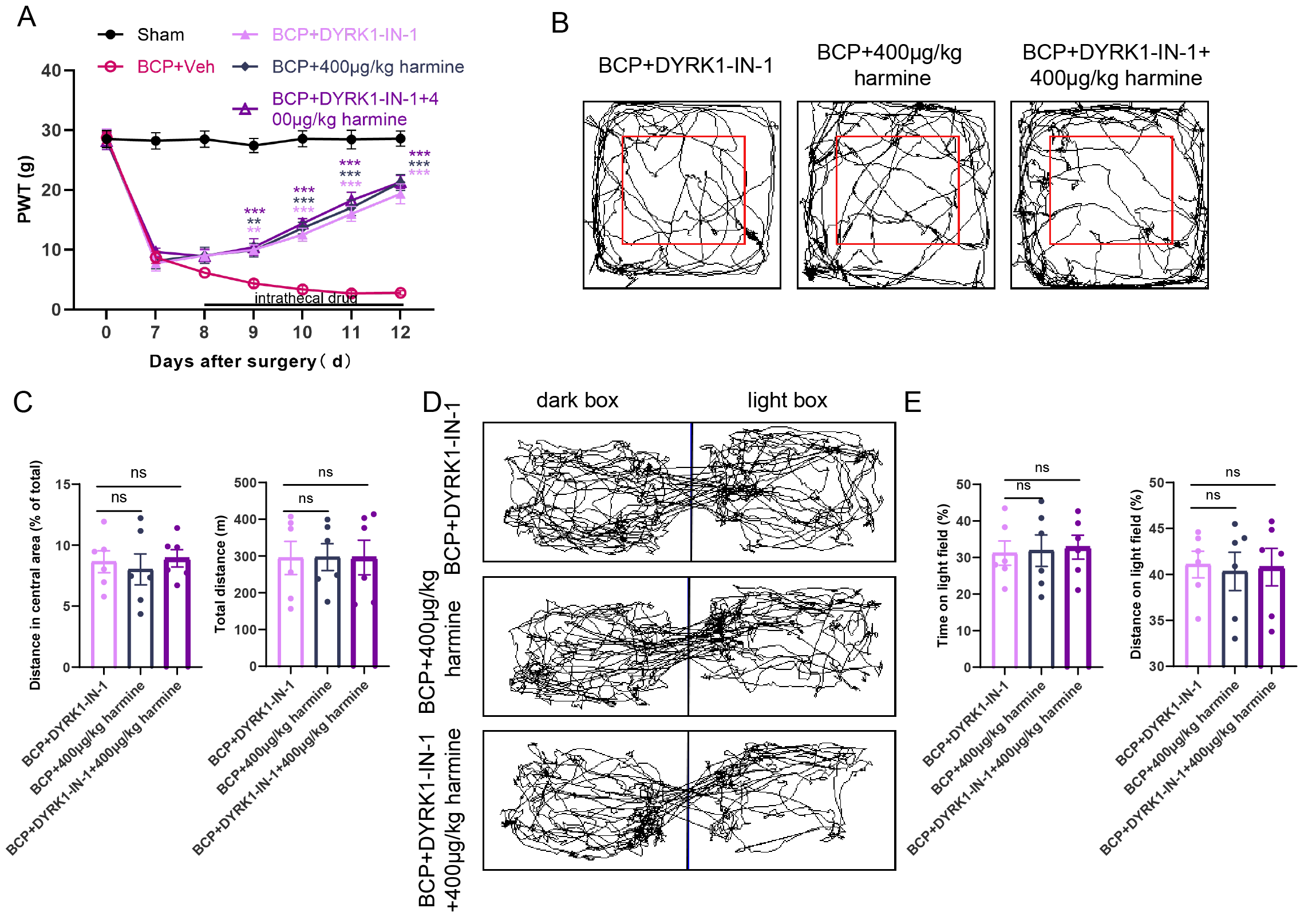

To further elucidate the role of the DYRK1A/NF-

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Effects of intrathecal injection of DYRK1-IN-1 and Harmine on

pain behavior in rats with BCP. (A) Von Frey test was used to evaluate the

effects of BCP + DYRK1-IN-1, BCP + Harmine, and BCP + DYRK1-IN-1 + Harmine on

pain thresholds in rats with BCP (n = 6). (B,C) OFT detected changes in the total

distance covered and the distance traversed in the central area by the three

groups of rats (n = 6). (D,E) LDT detected changes in the duration and distance

traveled in the bright box among the three groups of rats (n = 6). **p

In addition to assessing mechanical pain thresholds, we evaluated the anxiety levels of the rats in each group using behavioral tests. The OFT results demonstrated that all groups maintained intact motor function without significant differences in the total distance traveled within the same time period. Moreover, the rats’ desire to explore the central region was restored in all three groups, with no significant differences among them (Fig. 5B,C). Similarly, the LDT results indicated no significant differences among the three groups in terms of time spent and distance traveled in the light box, suggesting that all three treatments exerted anxiolytic effects (Fig. 5D,E).

These findings demonstrate that the inhibition of DYRK1A by DYRK1-IN-1 and

administering Harmine produced consistent effects, alleviating pain and

anxiety-like behaviors in rats with BCP. Co-administration of DYRK1-IN-1 and

Harmine did not enhance the analgesic effects on BCP or pain-related negative

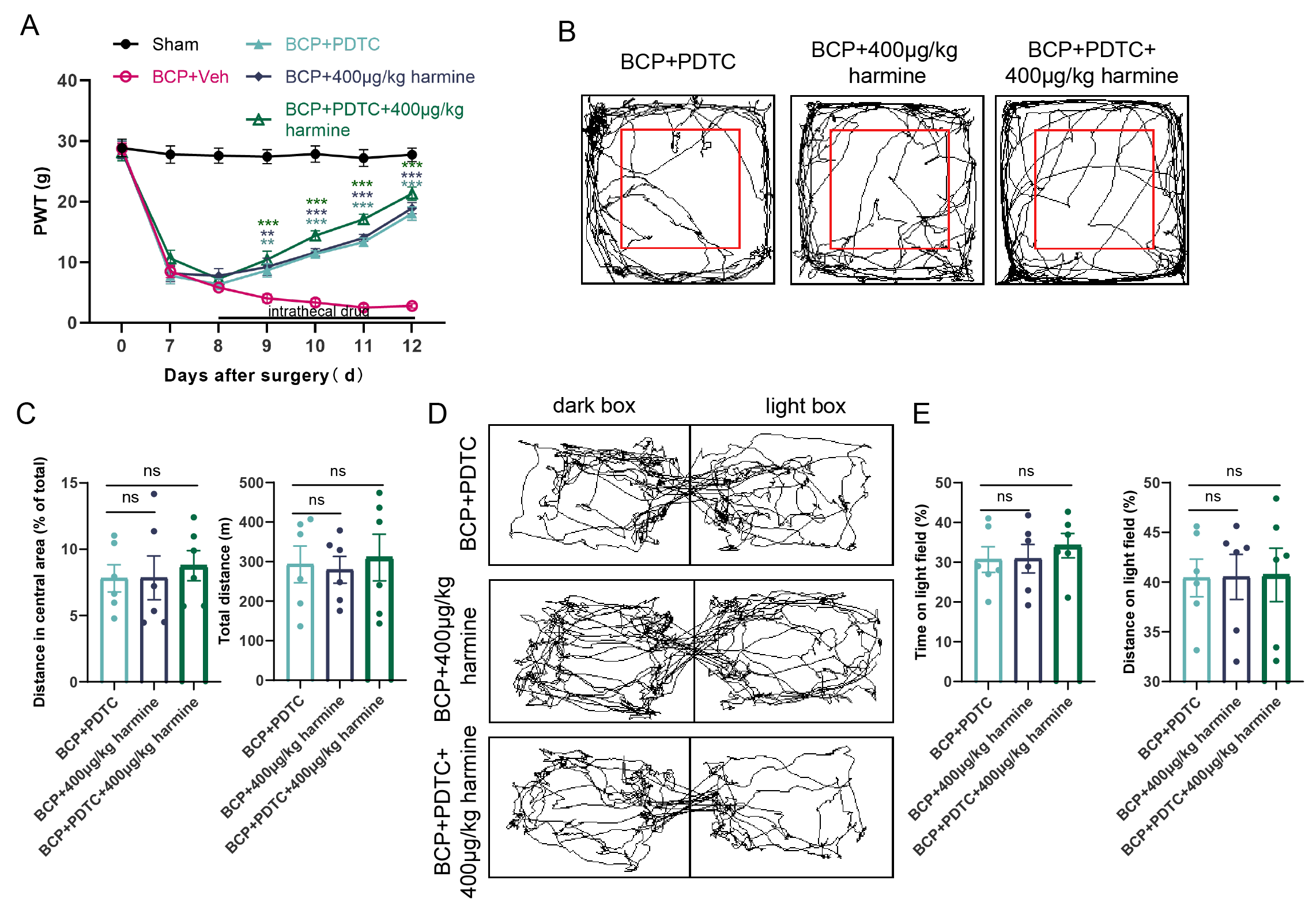

emotional behaviors. Similar experiments targeting NF-

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Effects of intrathecal injection of PDTC and Harmine on pain

behavior in rats with BCP. (A) Von Frey test was used to evaluate the effects of

BCP + PDTC, BCP + Harmine, and BCP + PDTC + Harmine on pain thresholds in rats

with BCP (n = 6). (B,C) OFT detected changes in the total distance covered and

the distance traversed in the central area by the three groups of rats (n = 6).

(D,E) LDT detected changes in the duration and distance traveled in the bright

box among the three groups of rats (n = 6). **p

BCP is a significant clinical challenge that profoundly affects the quality of

life of patients with advanced malignancies. The findings of this study provide

compelling evidence that Harmine, a

The underlying mechanisms of the analgesic effects of Harmine appear to be

closely linked to the modulation of the DYRK1A/NF-

Inflammatory factors and chronic pain mechanisms interact in complex ways.

Inflammatory mediators are released in response to injury or disease, and these

factors not only directly enhance the sensitivity of nociceptors but also promote

and sustain chronic pain through various mechanisms. Our findings indicate that

Harmine not only inhibits the activation of DYRK1A but also reduces the

expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-1

Furthermore, the behavioral assessments conducted in this study revealed that Harmine treatment not only alleviated mechanical hypersensitivity but also mitigated anxiety-like behaviors associated with chronic pain. OFT and LDT results indicated that Harmine-treated rats exhibited increased exploratory behavior, suggesting an improvement in their overall emotional state. This is particularly important because chronic pain is often accompanied by psychological distress that can complicate treatment outcomes.

While this study provides valuable insights into the analgesic properties of Harmine, it is essential to address certain limitations. This study primarily focused on a rat model of BCP, and further studies are needed to evaluate the translational potential of these findings in human subjects. Additionally, the long-term effects of Harmine and its safety profile require thorough investigation to establish its viability as a clinical treatment option.

Our study provides compelling evidence that Harmine exerts significant analgesic

effects in a rat model of BCP, which correlates with the suppression of the

DYRK1A/NF-

Data will be made available upon request.

SYZ: the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. SZ: the acquisition and analysis of data, YL, LC, JL and JJ: the acquisition of data. MY: design of the work, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision. LX: design of the work, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, writing – review & editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

These experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jiaxing University (Ethical Approval No. JUMC2021-093) and were conducted in strict adherence to the guidelines set forth by the International Association for the Study of Pain for the care and use of laboratory animals. All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jiaxing University and were performed following the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.

Not applicable.

The study was supported, in part, by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LTGC23H090002), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171216), People’s Livelihood Science and Technology Innovation Research Project of Jiaxing City (2023AY31025), Clinical Key Specialties of Zhejiang Province -Anesthesiology (2023-ZJZK-001) and National Clinical Key Specialties-Oncology (2023-GJZK-001).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/JIN38100.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.