1 Affiliated Psychological Hospital of Anhui Medical University; Anhui Mental Health Center; Hefei Fourth People’s Hospital, 230026 Hefei, Anhui, China

2 School of Mental Health and Psychological Sciences, Anhui Medical University, 230032 Hefei, Anhui, China

3 Key Laboratory of Philosophy and Social Science of Anhui Province on Adolescent Mental Health and Crisis Intelligence Intervention, Hefei Normal University, 230061 Hefei, Anhui, China

Abstract

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a global health concern, with alcohol abuse leading to structural damage to white matter (WM) fiber tracts, which are crucial for cognitive and emotional functions. However, existing studies often lack systematic evaluations of these changes and their clinical correlations.

Using tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS), we analyzed diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data from 20 AUD patients and 20 healthy controls. Correlations between fractional anisotropy (FA) values and clinical symptoms, including cognitive dysfunction, depression, and impulsivity, were examined.

AUD patients presented significantly decreased FA values in the right corpus callosum, right fornix, left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, and left cerebral white matter. The FA peak values of the right fornix and the left cerebral white matter were positively and significantly correlated with cognitive function scores in the AUD group after controlling for smoking status, age, and years of education.

Alcohol abuse significantly impairs WM integrity, particularly in regions related to cognitive and emotional regulation. These findings provide structural evidence for the neurobiological mechanisms of AUD and suggest that FA may serve as a potential biomarker for assessing brain damage, guiding therapeutic interventions.

Keywords

- white matter

- microstructure

- alcohol use disorder

- tract-based spatial statistics

- corpus callosum

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a common and serious global public health problem. Heavy alcohol consumption is strongly associated with neurocognitive impairment. These lesions often result from damage to the white matter (WM) fibre tract of the brain [1, 2], which is critical for neural communication and functional connectivity. This impairment may contribute to the cognitive deficits, emotional dysregulation, and behavioral problems common in AUD patients and, in extreme cases, may even trigger alcohol-related dementia [3].

Previous study has shown low fractional anisotropy (FA) values in key brain regions (such as the corpus callosum, cingulate gyrus and thalamus) in AUD patients, and FA values are an indicator of microstructural integrity in white matter [4]. These regions are strongly linked to cognitive control, decision making, and emotion regulation. Furthermore, there is evidence that FA values are partially restored after prolonged abstinence, suggesting neuroplastic potential in AUD patients [5]. However, traditional diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) analysis methods have limitations, such as individual differences in white matter structure and difficulties in spatial standardization, which may hinder the accurate detection of microstructural changes [6, 7].

To address these issues, tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) were used in this study. This method overcomes the problems of geometric deformation and individual differences by projecting white matter data onto common skeleton templates to assess disease-related changes more precisely. Furthermore, TBSS combines advanced techniques such as nonlinear registration and local fibre orientation estimation to handle complex crossings and branching of fibre bundles.

Despite methodological improvements, the degree of white matter microstructural damage and its association with clinical symptoms in AUD patients remain underexplored. Previous study focused only on specific brain regions or used limited indicators, leading to an incomplete understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms of AUD [8]. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of drinking patterns, comorbidities, and other confounding factors in the AUD population was not adequately controlled, further increasing the complexity of the interpretation of the results.

The main objective of this study was to analyse the white matter integrity of patients with AUD via the TBSS system and to explore the relationships between FA values and clinical symptoms such as cognitive dysfunction, depression, anxiety and impulsivity. By analysing these correlations, this study aims to identify specific brain regions affected by alcohol use disorder and provide insights into the mechanisms involved. In addition, research aims to discover potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for the diagnosis and treatment of AUD. Through a multidimensional comprehensive approach, this study attempts to fill the gap in the literature and deepen the understanding of the effects of alcohol addiction on white matter structure and function.

In conclusion, this study utilized the advantages of the TBSS technique to assess the extent of white matter damage in AUD patients, focusing on the regional specificity and clinical relevance of these changes. By integrating advanced imaging techniques with clinical assessment, this study aims to bridge the existing knowledge gap and lay the foundation for improving diagnostic and treatment strategies for improving alcohol-related brain injury.

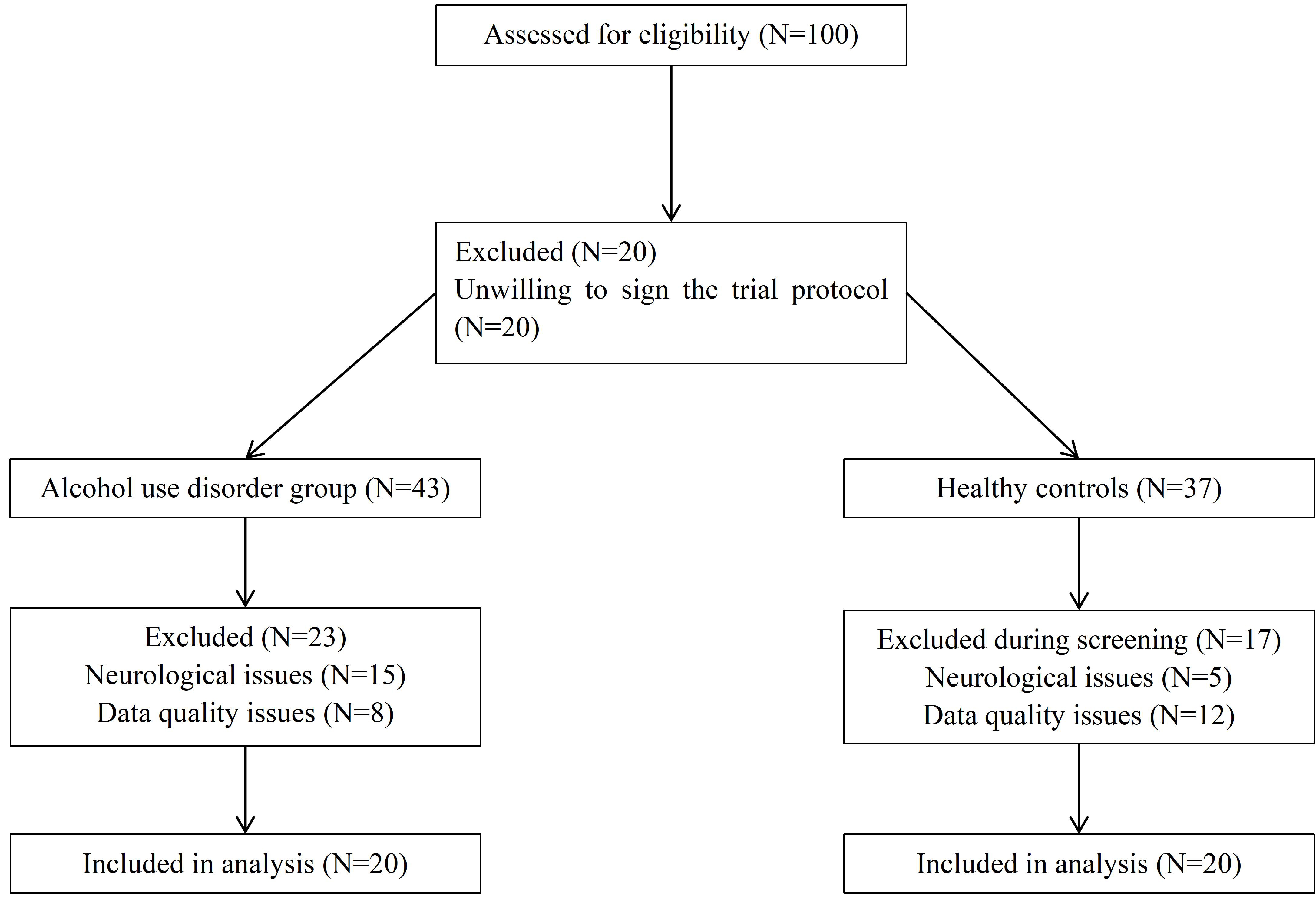

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 100 potential participants were recruited for screening, and the patient group and healthy control group were ultimately included in the analysis. Finally, this study recruited 40 subjects aged 23–71 years from the Anhui Mental Health Center, including 20 alcohol use disorder patients (AUD group) and 20 healthy controls (HC group). All participants were male to control for potential sex-related differences in white matter structure.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The process of screening participants.

The inclusion criteria for the AUD group included a clinical diagnosis of alcohol dependence according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), as well as the International Classification of Diseases 11th revision (ICD-11). The exclusion criteria included poor data quality (e.g., motion artifacts during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning), a history of neurological diseases (epilepsy), or brain trauma. In the AUD group, 85% of the participants were smokers, and the mean relapse time was 1.90 (SD = 2.86). Except for three AUD patients who had no comorbidities, the majority of patients had comorbidities of hypertension and liver dysfunction. Healthy controls had no history of substance use disorders or major psychiatric illnesses. All participants provided informed consent and were required to abstain from alcohol for at least 72 hours prior to scanning.

A series of standardized scales were used to comprehensively evaluate cognitive and psychological characteristics. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to assess cognitive function [9]. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) was administered to measure the severity of alcohol dependence [10]. Depression and anxiety symptoms were assessed via the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA), respectively [11, 12]. Impulsivity was evaluated via the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) [13]. The rationale for selecting these scales was their established reliability and relevance to AUD-related cognitive and emotional dysfunction. To ensure consistency, all assessments were administered by trained clinicians.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data were acquired via a 3T MRI scanner (PG75E1800011SC; manufacturer: General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA). The

scanning parameters were set as follows: repetition time (TR) = 8000 ms, echo

time (TE) = 100 ms, b value = 1200 s/mm2, field of view (FOV) = 220 mm,

matrix size = 256

Preprocessing of DTI data was performed via the FMRIB Software Library (FSL v6.0.3, http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/). The key preprocessing steps included the following steps: (1) Nonbrain Tissue Removal: The bet command was used to generate brain masks by removing nonbrain tissues. (2) Motion and eddy current correction: The eddy_correct command was applied to adjust for distortions caused by gradient coil eddy currents and head motion. (3) FA Value Calculation: Using the tool of fitting diffusion tensors (DTIFIT, https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/docs/#/diffusion/dtifit), the FA index was calculated on the basis of the diffusion tensor model.

The tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) pipeline was used to assess white

matter integrity: (1) Skeleton Extraction: FA skeletons,

representing the central portion of the white matter tracts, were extracted from

each subject. (2) Spatial Registration: Nonlinear registration (FNIRT) aligns

individual FA maps to the standard-space image (FMRIB58_FA,

https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/docs/#/diffusion/tbss) template in Montreal

Neurological Institute (MNI) space. Thresholding: An FA threshold of 0.2 was

applied to exclude nonwhite matter regions. (3) Statistical analysis: For the FA

values of the two groups of subjects, a permutation test was performed via the

random tool in FSL, with a permutation frequency of 5000. The statistical results

were corrected via family wise error (FWE), and multiple correction comparisons

were conducted via the threshold-free cluster enhancement correction (TFCE)

method, with significance set at p

Owing to the limitation of the sample size in this study, we need to test the normality and homogeneity of variance first. If the assumptions are met, independent samples t tests will be used to compare demographic and clinical scale data between two groups. If not, the Mann-Whitney U test will be used. Accordingly, Pearson or Spearman rank correlation coefficients will be used to measure the correlations between FA peak values from key regions of interest and scale scores. To address potential confounding variables (e.g., smoking, age and education level), these factors were included as covariates in the statistical models. Additionally, scale data were standardized via Z scores to facilitate comparisons across measures. Multiple comparison corrections, such as the Bonferroni method, were applied to minimize false positives.

All the data were subjected to rigorous quality control. Preprocessing steps were double-checked to ensure accuracy, and outliers were removed from the analysis. The inclusion of high-quality data enhanced the reliability and reproducibility of the findings.

The results of the Shapiro-Wilk test revealed that, with the exception of the

AUD group’s age (p = 0.14) and MAST score (p = 0.11), all the

other variables did not follow a normal distribution (p

The demographic and clinical results are shown in Table 1. The median age of the

AUD patients was 42 (IQR = 13), whereas the median age of HC group was 51.5 (IQR

= 22). The median years of education were 9 (IQR = 3) for the AUD group and 12

(IQR = 5) for the HC group. No significant differences in age (Z =

–1.84; p = 0.068) or years of education (Z = –1.46; p = 0.165) were found between the two groups, indicating that the groups were

demographically comparable and that the likelihood of confounding effects was

reduced. The median MMSE score was 28.55 (IQR = 1.8) in the AUD group and 29 (IQR

= 2) in the HC group, with no significant difference between two groups

(Z = –0.47; p = 0.659). However, the HAMD and HAMA scores were

significantly greater in the AUD group (HAMD: median (IQR) = 8.5 (5.8); HAMA:

median (IQR) = 4 (4)) than in the HC group (HAMD: median (IQR) = 2 (2); HAMA:

median (IQR) = 1 (1)), indicating more pronounced depressive and anxiety symptoms

in AUD patients (HAMD: Z = –5.06, p

| Measures | AUD group (n = 20) | Health controls (n = 20) | Z | p |

| Age | 42 (13) | 51.5 (22) | –1.84 | 0.068 |

| Years of education | 9 (3) | 12 (5) | –1.46 | 0.165 |

| MMSE score | 28.55 (1.8) | 29 (2) | –0.47 | 0.659 |

| HAMD score | 8.5 (5.8) | 2 (2) | –5.06*** | |

| HAMA score | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | –3.92*** | |

| BIS-11 score | 75 (8.5) | 48 (28.8) | –3.60*** | |

| MAST score | 42 (5) | 0 (0) | –5.64*** |

All participants were males.

MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; BTS-11, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Version 11; MAST, Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test; AUD, Alcohol Use Disorder.

The values in columns 2 and 3 are the medians (interquartile ranges).

Two-tailed test. ***p

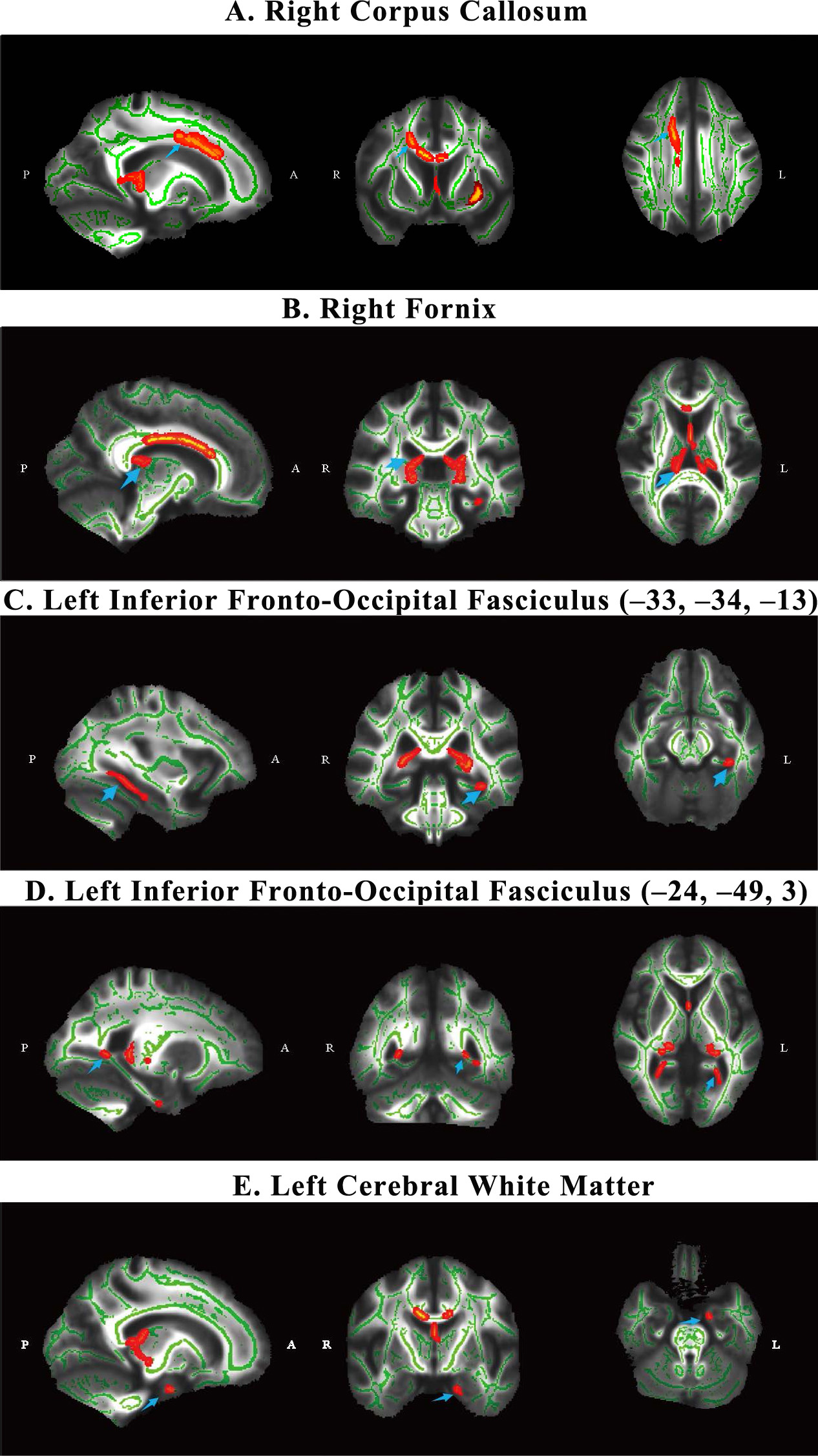

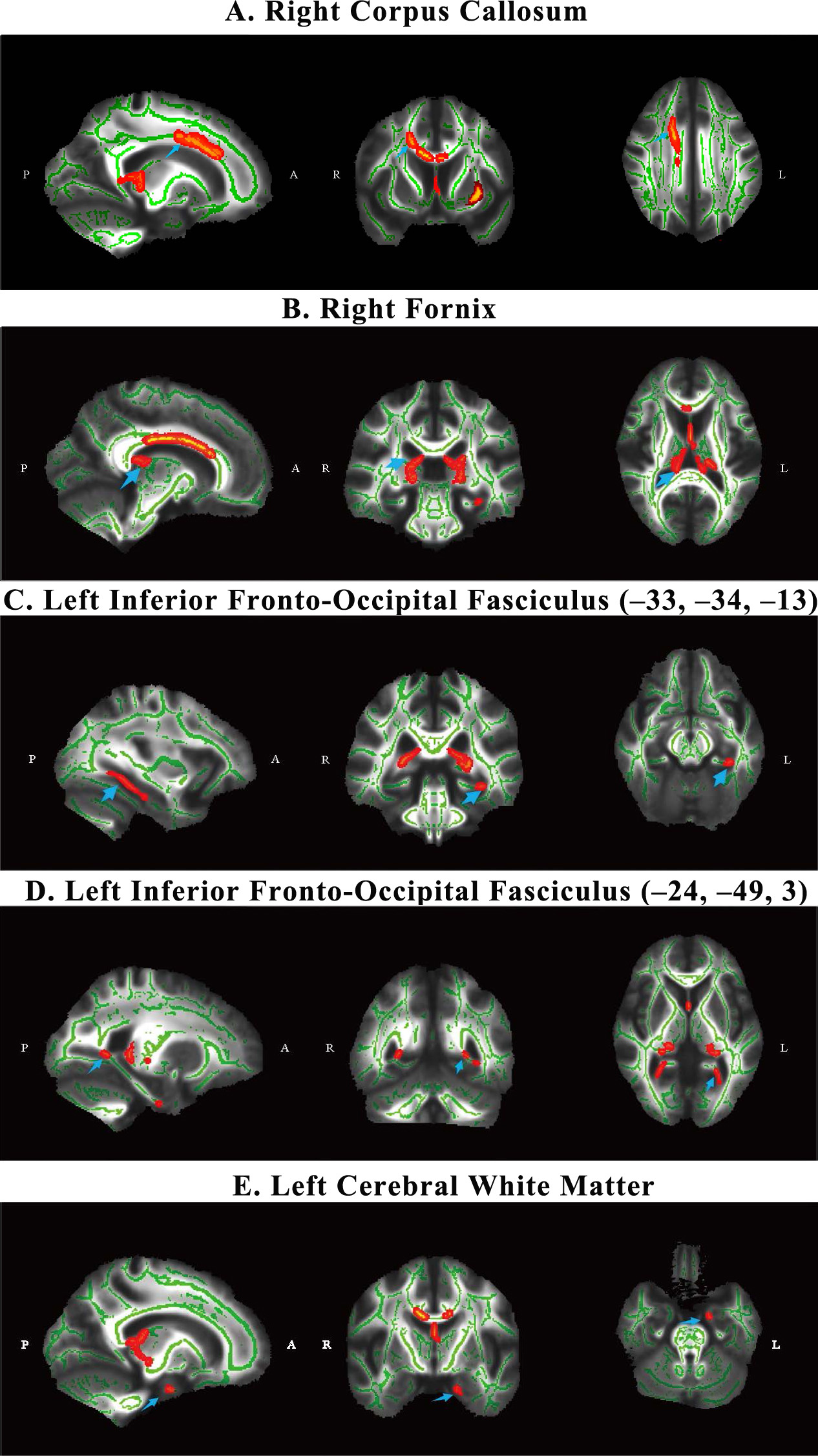

Tract-based spatial statistics analysis revealed significant differences in white matter integrity between the AUD and HC groups. As shown in Table 2, the AUD group presented decreased FA values in several white matter regions, including the right corpus callosum (cluster size = 1102, t = 0.964, p = 0.036), the right fornix (cluster size = 976, t = 0.959, p = 0.041), the left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (center (x = –33, y = –34, z = –13): cluster size = 197, t = 0.955, p = 0.045; center (x = –24, y = –49, z = 3): cluster size = 30, t = 0.951, p = 0.049), and the left cerebral white matter (cluster size = 59, t = 0.952, p = 0.048). The specific locations of the five areas are shown in Fig. 2. The differences in FA values suggest that AUD patients experience significant white matter damage in these areas compared with healthy controls.

| Brain regions | Center of mass (x, y, z) | Cluster size | t | p |

| Right corpus callosum | 18, 10, 33 | 1102 | 0.964* | 0.036 |

| Right fornix | 11, –29, 14 | 976 | 0.959* | 0.041 |

| Left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus | –33, –34, –13 | 197 | 0.955* | 0.045 |

| Left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus | –24, –49, 3 | 30 | 0.951* | 0.049 |

| Left cerebral white matter | –16, –6, –25 | 59 | 0.952* | 0.048 |

Alcohol use disorder group is less than healthy controls;

x, y, z, the location of its peak value in the cluster (MNI coordinates);

The p value has been corrected for FWE. *p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The WM differences between AUD and HC group. Images (A–E)

represent five main significantly different regions identified after patients

with AUD were compared with healthy controls (HC). The

blue arrows point to five brain regions. All significant regions were corrected

for multiple comparisons via Family Wise Error (FWE) (p

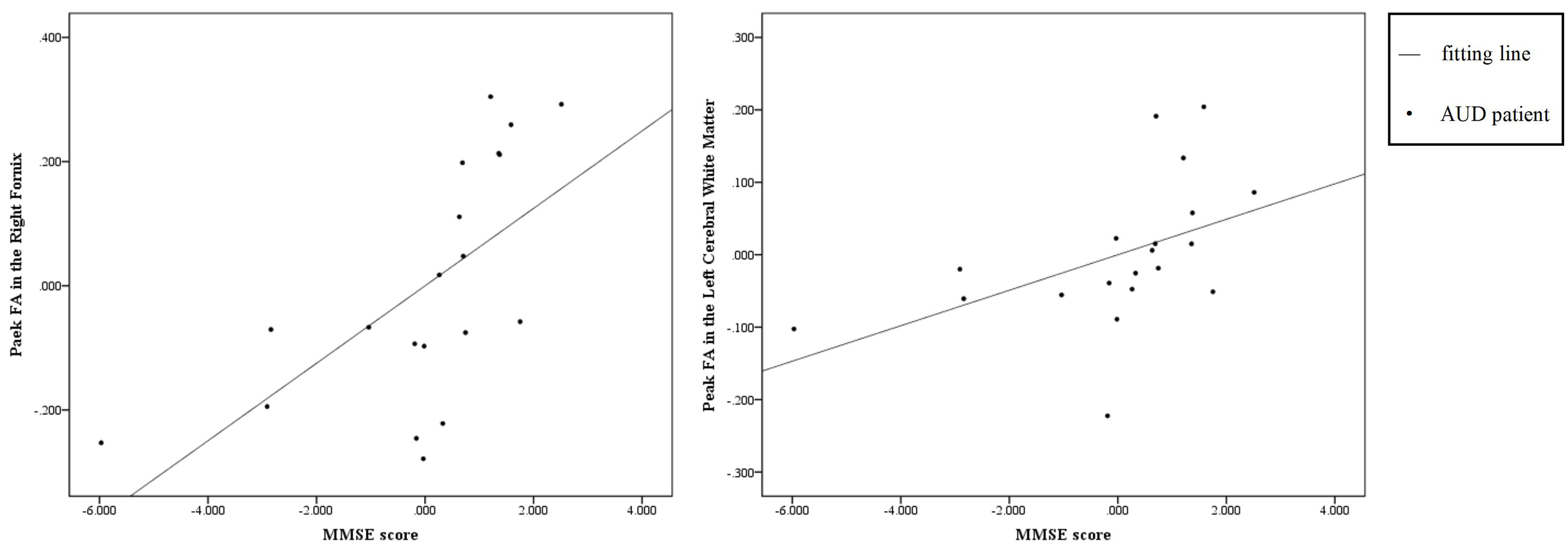

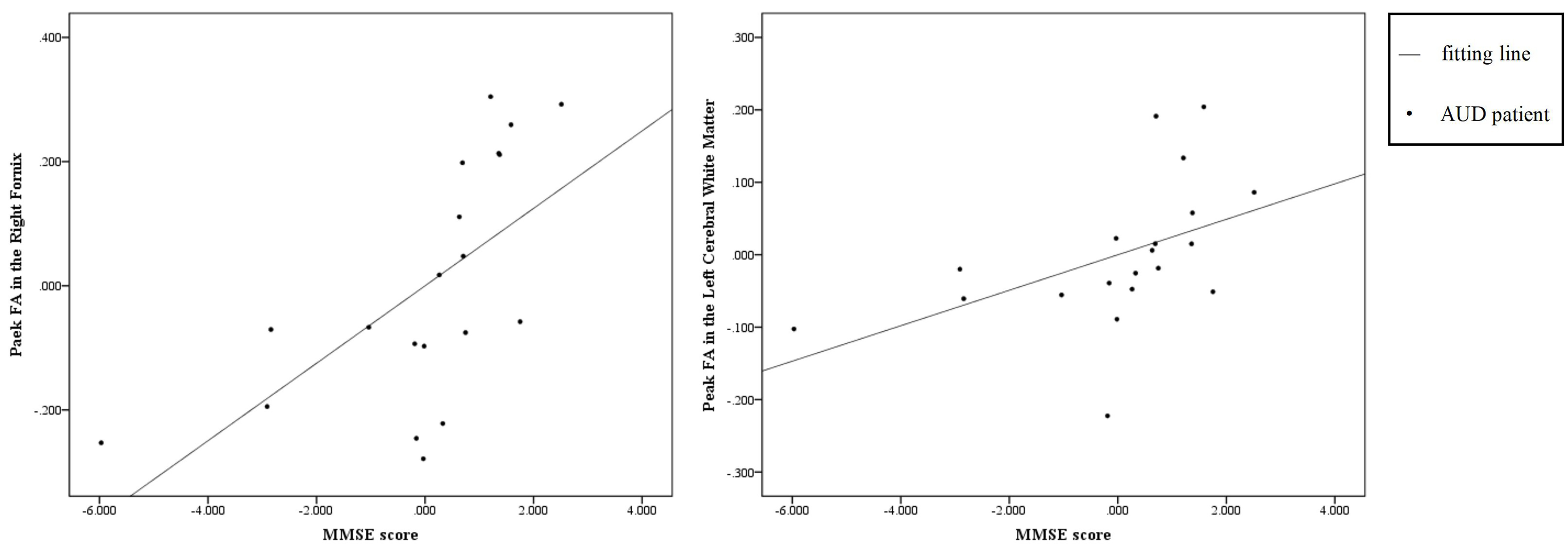

We calculated the Spearman rank correlation coefficient between the FA peak

values of the five regions of interest (ROI) and clinical scale scores in the AUD

group after controlling for smoking, age and years of education. After Bonferroni

multiple comparison correction, the significance level was set as p

| Peak FA | MMSE | HAMD | HAMA | BIS-11 | MAST | |

| Right corpus callosum | –0.209 | –0.114 | –0.057 | 0.202 | –0.250 | |

| Right fornix | 0.755*** | 0.517 | 0.068 | –0.402 | 0.197 | |

| Left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus | ||||||

| (x = –33, y = –34, z = –13) | –0.239 | –0.386 | –0.012 | 0.242 | 0.053 | |

| (x = –24, y = –49, z = 3) | 0.391 | 0.080 | –0.191 | –0.161 | 0.517 | |

| Left cerebral white matter | 0.675*** | 0.427 | –0.081 | –0.277 | 0.230 | |

These values are correlation coefficients

FA, fractional anisotropy.

After Bonferroni multiple comparison correction, the significance level was set

as p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The scatter diagram of correlation results. These scatter plots showing the partial correlation between residuals of FA peak value and MMSE score in the alcohol use disorder group (AUD, n = 20) after adjusting for smoking, age, and years of education; Data points represent individual participants in the AUD group and trend line indicates the linear fit; X-axis: Residuals of MMSE score (adjusted for smoking, age, and years of education); Y-axis: Residuals of FA peak value (adjusted for smoking, age, and years of education).

This study provides important insights into the effects of alcohol abuse on white matter integrity in the brain. Using tract-based spatial statistics, we found significantly lower FA values in multiple key brain regions in AUD patients than in healthy controls. These findings further support the association of alcohol addiction with the impairment of white matter structure and its associated cognitive and emotional dysfunction.

The decrease in FA values observed in the right corpus callosum is consistent with the previous study showing that AUD has particularly significant effects on brain regions involved in cognitive control, emotion regulation and executive function [14]. The corpus callosum, the main white matter fibre bundles responsible for interhemispheric communication, presented the most pronounced decrease in FA values. An impairment in this region may underlie the cognitive deficits and impaired decision-making in AUD patients [15]. In addition, the microstructure of corpus callosum in individuals with alcoholism was significantly associated with compromised interhemispheric processing. Damage or compromise to the corpus callosum due to chronic alcohol consumption contributes significantly to the observed cognitive deficits in alcoholism, including difficulties in managing global versus local information processing conflicts [16]. Besides, the fornix forms the two major fiber bundles of the limbic system, and their degradation might result defects in the emotional regulation process [17].

Moreover, 17 (85.0%) AUD patients smoked simultaneously, which may be attributed to some white matter abnormalities resulting from the synergistic neurotoxic effects of alcohol and nicotine. One study has shown that smoking alone can lead to alterations in white matter microstructure and that its interaction with alcohol may exacerbate neurological injury [8]. It has also been found that white matter recovery may be more pronounced in long-term abstainers, whereas relapsing drinkers have difficulty maintaining abstinence due to persistent damage or accelerated aging (e.g., corpus callosum). In contrast, the proportion of co-morbidities (e.g., depression, hypertension) did not differ significantly between groups and did not significantly affect the main white matter indicators, suggesting that white matter damage is directly related to the state of return to drinking rather than to co-morbidities [18].

Our findings revealed significant correlations between FA peak values and cognitive function scores in the AUD group after controlling for smoking, age and years of education, providing additional insights into the functional consequences of white matter damage. For example, the positive correlation between MMSE scores and FA peak values underscores the role of white matter integrity in maintaining cognitive function [19, 20]. Lower FA peak values in the right fornix and the left cerebral white matter of AUD patients were associated with lower MMSE scores which indicated potential cognitive impairment. The FA value reflects the integrity of the microstructure of white matter, and the cognitive impairment of AUD patients may have a linear relationship with the right fornix and the left cerebral white matter damage. Causal evidence showed that alcohol-induced damage to the microstructural integrity of the fimbria/fornix reduces the effective communication from the hippocampus to the prefrontal cortex, which would impede the extinction of maladaptive memories and reduce cognitive flexibility [21]. Damage especially in the frontal white matter may contribute to a neurostructural marker of core cognitive deficits in AUD, including impulsivity and abnormal reward-based choice behaviour [22].

Furthermore, there was no significant correlations between FA peak values of corpus callosum and clinical scores in AUD patients. Another research also did not find direct correlation between FA in the corpus callosum and cognitive performance in detoxified alcoholic patients. This might due to the joint involvement of several brain regions in neurocognitive performance, and the disruption of one region may be compensated by other intact brain structures [4].

The structural changes observed in this study provide a potential explanation for the neurobiological mechanism of AUD. Chronic alcohol exposure causes demyelination, axonal degeneration, and glial abnormalities, all of which reduce white matter integrity [23]. Such changes may disrupt the neural network connectivity responsible for cognitive and emotional processing and thus exacerbate the clinical symptoms of AUD [24, 25, 26]. Moreover, white matter damage is both a consequence of alcohol dependence and a possible driver of alcohol dependence progression, forming a vicious cycle [27].

This study benefits from the application of TBSS, which improves the accuracy of white matter analysis by controlling for individual differences and optimizing spatial registration [28]. The inclusion of multidimensional clinical scales also provides a comprehensive assessment of the relationship between white matter integrity and behavioural symptoms. However, the following limitations should still be noted: the small sample size may limit the universality of the results, and the cross-sectional design cannot infer the causal relationship between alcohol use and white matter injury. Since long-term smoking similarly affects white matter integrity, the independent contribution of alcohol from nicotine is indistinguishable. Future studies should control for smoking status or include smoking-matched control groups to clarify the specific effects of AUD on white matter microstructure. Furthermore, heterogeneity of drinking patterns, withdrawal symptoms and comorbidities in AUD patients may introduce outcome variation. Future studies should validate the results with a larger sample size and longitudinal design, and explore the potential for white matter recovery after withdrawal or intervention.

These findings have implications for clinical practice and for future research. Our results suggest that FA may be used as an indicator to assess the integrity of white matter microstructure in patients with AUD, facilitating early diagnosis, personalized treatment and efficacy monitoring. This study’s identification of region-specific FA reductions correlated with cognition in AUD patients implicates the idea that FA measurements could flag early cognitive decline before it’s clinically apparent. Future research should validate these findings in larger and longitudinal cohorts. Moreover, previous abstinence studies suggest the possible reversibility of white matter damage, which highlights the importance of early intervention and continuous treatment [29, 30]. Future studies should focus on the efficacy of interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy, medication, and lifestyle modification in reducing white matter injury and improving clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence of significant white matter damage in AUD patients, particularly in regions critical for cognitive and emotional functions. While further research is needed to address these limitations and explore the potential for recovery, these findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms of AUD and highlight the importance of early and targeted interventions to mitigate its impact on brain health.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

SH: Formal analysis, Visualization and Writing-review & editing; QZ: Formal analysis, Writing-original draft and Writing-review & editing; LW: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing-original draft, Project administration and Resources; YL: Writing-review & editing, Resources and Data curation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hefei Fourth People’ Hospital (HFSY-IRB-KYXM-PJ-WL). All patients or their families/legal guardians provided informed consent. All researchers contributing to the manuscripts are obliged to comply with all research and publication ethics practices in line with the ethical regulations published by the American Psychological Association and the American Medicine Association.

We are grateful for the subject recruitment supported by the Anhui Province Key Clinical Specialty (Clinical Psychology and Mental Rehabilitation) and Hefei Municipal Key Clinical Specialty (Substance Dependence). In addition, we thank Lizhuang Yang and Chuangwei Dong from Chinese Academy of Sciences, on their contribution to the data analysis.

This work was supported by the grants from Anhui Province Key Research and Development Project (202204295107020004), Anhui Health Commission Research Project (AHWJ2022b095), Key Laboratory of Philosophy and Social Science of Anhui Province on Adolescent Mental Health and Crisis Intelligence Intervention Open Fund (SYS2023A04), and Hefei Municipal Health Commission Applied Medicine Research Project (Hwk2022zd015).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.