1 Department of Neurological Rehabilitation, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, 450000 Zhengzhou, Henan, China

2 The Second Clinical Medical School, Zhengzhou University, 450000 Zhengzhou, Henan, China

Abstract

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a critical form of stroke with limited treatment options, with secondary brain injury significantly affecting patient outcomes. This study investigated the neuroprotective benefits of idebenone (IDE) in ICH.

An ICH model was established in mice and the temporal progression of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation was evaluated. IDE was then administered intraperitoneally for 3 consecutive days to evaluate its therapeutic effects. Tissue histology was examined after staining with hematoxylin-eosin and TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL), while oxidative stress was assessed by western blotting and measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and neuroinflammation was examined using immunostaining, western blotting, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation peaked at 3 days post-ICH, with elevated levels of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and significant microglial activation. IDE-treated mice had reduced hematoma volumes and improved neurological outcomes. IDE administration decreased Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) expression while increasing Nrf2 and NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) levels, leading to reduced oxidative damage (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, and p < 0.05, respectively). Moreover, IDE attenuated microglial activation and neutrophil recruitment (p < 0.01, p < 0.01), reduced the levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels (p < 0.05, p < 0.05, and p < 0.05, respectively), and increased IL-10 expression (p < 0.01). IDE also preserved the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and reduced brain edema.

The results demonstrated that IDE exerts neuroprotective effects in ICH through the mitigation of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation during the acute injury phase. IDE may be a viable therapeutic intervention for ICH.

Keywords

- idebenone

- intracerebral hemorrhage

- neuroprotective agents

- oxidative stress

- inflammation

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a critical form of stroke, representing 12–20% of all stroke occurrences, and linked to elevated mortality and disability. The 30-day mortality rate following ICH ranges from 43% to 51% [1]. The resulting brain injury is categorized into primary brain injury and secondary brain injury (SBI) [2]. While primary damage results from direct mechanical damage due to hematoma formation, SBI arises from the activation of pathways that induce further injury, including those associated with neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, iron toxicity, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption [2]. These factors collectively contribute to poor prognosis [2]. Currently, the primary treatment for ICH involves hematoma evacuation [3]. However, clinical trials have shown that the surgical removal of hematomas does not improve functional outcomes significantly and offers no clear benefit over conservative management [4, 5]. As a result, the treatment of ICH remains a major challenge, requiring further investigation into the mechanisms of brain injury, particularly SBI, and the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Neuroinflammation, driven primarily by microglia and neutrophils, plays a key

role in SBI following ICH [1, 6, 7]. Activation of glial cells by blood-derived

components within the hematoma can induce the release of pro-inflammatory

cytokines, such as interleukin-1

Idebenone (IDE) is a synthetic analog of coenzyme Q10, initially developed by Takeda Pharmaceuticals for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease [15]. Its therapeutic potential has thus far been demonstrated in various disorders, including neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular diseases [16, 17, 18]. IDE functions as a potent antioxidant, effectively inhibiting lipid peroxidation [19]. Moreover, studies suggest that IDE also exerts anti-inflammatory effects [20, 21]. While the effect of IDE on stroke is understood, the exact mechanisms require additional exploration [22]. This study investigates the neuroprotective effects of IDE in ICH, focusing on its impact on neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, perihematomal brain edema, and integrity of the BBB. These results offer valuable insights into the therapeutic potential of IDE and offer a foundation for its clinical application in the management of ICH.

All animal procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University (KY2024064) and were conducted following the National Institutes of Health’s “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”. Adult male C57BL/6J mice (18–22 g) were used in this study (Hua FuKang Experimental Animal Company, Beijing, China). Mice were housed under controlled conditions. A total of 164 operated mice were randomly allocated to the following groups:

Part I: Sixty-five male mice were allocated to five groups (n = 13), namely, (1) a sham group and (2) four ICH groups with assessments at different time points (1, 3, 7, and 14 days).

Part II: Ninety-nine male mice were assigned to three groups, namely, (1) a sham group, which received the vehicle consisting of 5% dimethyl sulfoide (DMSO) (D8370, Solarbio, Beijing, China), 30% PEG300 (HY-Y0873, MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA), 5% Tween 80 (HY-Y1891, MedChemExpress), and 60% ddH2O, (2) an ICH + Vehicle group, which also received the vehicle, and (3) an ICH + IDE group, which received IDE (58186-27-9, TargetMol, Boston, MA, USA). Following surgery, the three groups were given vehicle or IDE (100 mg/kg) in a final volume of 100 µL via intraperitoneal injection for three consecutive days.

The ICH model was established based on a previously published protocol [23]. Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal administration of a ketamine-xylazine solution, comprising ketamine (100 mg/kg, H20193336, Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd, Jiangsu, China) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, X0069, TCI Chemical Industry Development Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). Following this, experimental mice were secured in a stereotaxic apparatus (ZH-BLUESTAR B/S, Anhui Zhenghua Biologic Apparatus Facilities Co., Ltd., Anhui, China) for the surgical procedure. Type VII collagenase (0.075 U; C0773, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) was injected into the right striatum using a Hamilton syringe at coordinates 2.0 mm lateral to the bregma and 3.5 mm ventral to the skull base. Experimental animals in the sham group were subjected to the identical surgical protocol without receiving collagenase. Postoperatively, mice were positioned on a warming pad to maintain body temperature until they fully recovered from the anesthesia.

Neurological deficits were assessed using the modified neurological severity score (mNSS) and the corner test on days 1 and 3 post-ICH, as noted in prior reports [24, 25]. The mNSS consists of five components: motor function, sensory function, balance, reflexes, and abnormal movements. Scores range from 0 (normal function) to 18 (maximal neurological impairment), with higher scores indicating greater deficits.

For the corner test, mice were placed between two angled walls (30°), allowing them to move forward and turn. The frequency of left and right turns was documented, and the score was calculated as follows:

Higher scores indicate more severe left hemiparesis. All behavioral assessments were conducted by investigators blinded to the group assignments.

The mice were euthanized on day 3 after ICH modeling with carbon dioxide (CO2) (30% chamber volume displacement/min, followed by decapitation). Brain tissues were collected and dissected into ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres together with the cerebellum, as previously reported [26]. The wet weight of the sample was measured using an electronic analytical balance, followed by drying at 100 °C for a period of 24 hours, to ascertain the dry weight. The cerebellum served as an internal control. The equation for BWC is shown below:

Brain tissues were collected for protein extraction. Proteins were extracted

with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (P0013C, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and the supernatant

after centrifugation was collected. Protein concentrations were then quantified

using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (GK10009, GLPBIO, Montclair, CA, USA).

Separation of proteins was achieved through Tris-glycine gradient gel

electrophoresis, followed by transfer onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF)

membranes. The membranes were incubated with 5% nonfat milk for 2 hours to block

nonspecific binding, then incubated overnight with primary antibodies against

IL-1

Mice were euthanized with CO2 on day 3 post-ICH, and brain tissues were

homogenized and centrifuged to collect supernatants.

Levels of TNF-

Brain tissues were collected following cardiac perfusion and then paraffin embedded. The brain tissue that had been fixed in paraffin was then sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm. The sections were then deparaffinized and rehydrated, and then underwent antigen retrieval using citrate buffer. Following 30 minutes of blocking with immunostaining block buffer (P0102, Beyotime), the sections were treated overnight at 4 °C with anti-ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba-1) (1:200, 019-19741, Wako, Tokyo, Japan) and anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO) (1:200, ab208670, Abcam) primary antibodies. After rinsing with PBS, the sections were treated with the appropriate secondary antibodies (1:500, 4412, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) for 60 minutes in the dark. Following further PBS washes, the sections were mounted using an anti-fluorescence quenching mounting medium containing DAPI (S2110, Solarbio) and imaged using an Olympus microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), with positive cell counts were quantified by blinded observers using ImageJ software [27, 28].

The sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval. After cooling to room temperature, endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by treatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide, followed by blocking for 30 minutes. Primary antibodies were applied and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The following primary antibodies were used: Iba-1 (1:2000, ab178846, Abcam) and MPO (1:1000, ab208670, Abcam). Subsequently, HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibody (PV-8000, ZSBio, Beijing, China) was applied, and the samples were incubated for 20 minutes at ambient temperature. Finally, sections were stained with 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine solution, and nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. Differentiation was performed using ethanol hydrochloride rapid differentiation solution, followed by dehydration and transparency with xylene and ethanol [29].

The BrightGreen apoptosis Detection kit (A112-02, Vazyme, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) was utilized following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Overnight incubation was conducted with the primary antibody NeuN (1:1000, ab279295, Abcam). The sections were then incubated with the secondary antibody (1:500, 8890, Cell Signaling Technology) for one hour. Images were acquired utilizing an Olympus microscope.

The levels of MDA were measured to assess the degree of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. Brain tissues from the perihematomal region were collected three days post-ICH, and MDA levels were measured using a commercially available assay kit (KTB1050, Abbkine, Wuhan, Hubei, China). Absorbance values were determined with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Tissue sections underwent deparaffinization and were subsequently rehydrated using a graded series of ethanol (1030001-04-01, Paini Technology, Zhengzhou, Henan, China) and xylene (1046003-01-01, Paini Technology), followed by staining with H&E (C0105, Beyotime). Randomly selected fields within the hematoma region were evaluated and imaged under optical microscopy.

All experimental data are presented as mean

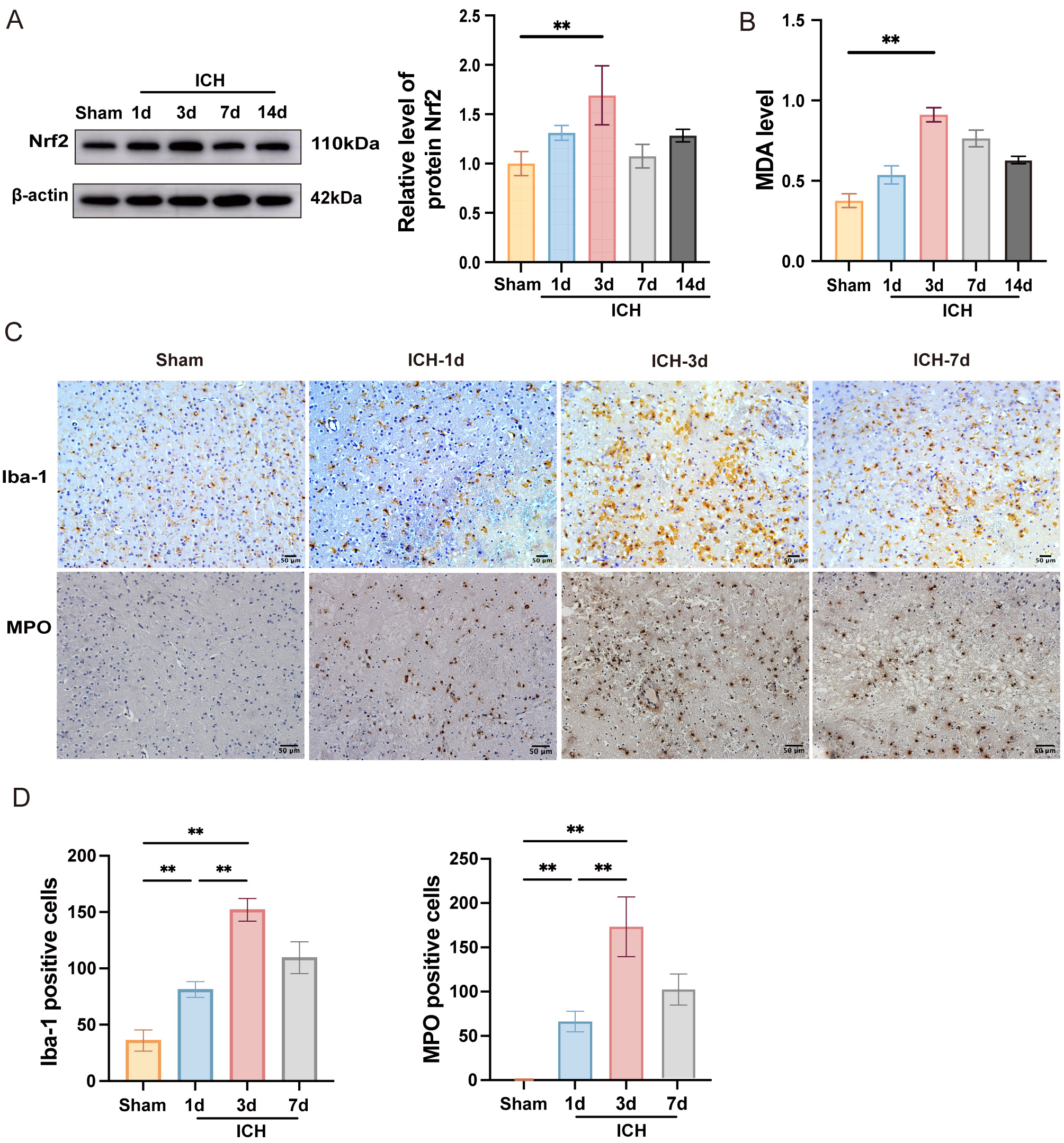

In order to evaluate alterations in oxidative stress, brain tissue specimens

were harvested at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days following ICH. Compared to the sham group,

Nrf2 expression in the ICH group increased from day 1, reaching its peak on day 3

(Fig. 1A, p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Time course expression levels of oxidative stress and

neuroinflammation after ICH. (A) Western blot analysis of Nrf2 on days 1, 3, 7,

and 14 after ICH, with quantification analysis (n = 3). (B) MDA content in the

perihematomal tissues was measured using a specific detection kit (n = 6). (C)

Immunohistochemical staining for Iba-1 and MPO was illustrated at various time

points (scale bar = 50 µm). (D) The quantities of Iba-1+ and MPO+ cells are

measured and illustrated in the respective bar graphs (n = 4). Values are

expressed as the mean

To evaluate neuroinflammation following ICH, immunohistochemistry was performed

to assess microglial activation and neutrophil infiltration in the perihematomal

region (Fig. 1C). The results demonstrated that, in contrast to the sham group,

both microglial activation and neutrophil recruitment peaked at day 3 post-ICH

(Fig. 1C,D, p

In sum, these findings indicated that oxidative stress and neuroinflammation reached their maximum levels three days after ICH. Therefore, day 3 post-ICH was selected for subsequent experiments to evaluate the neuroprotective effects of IDE in subsequent experiments.

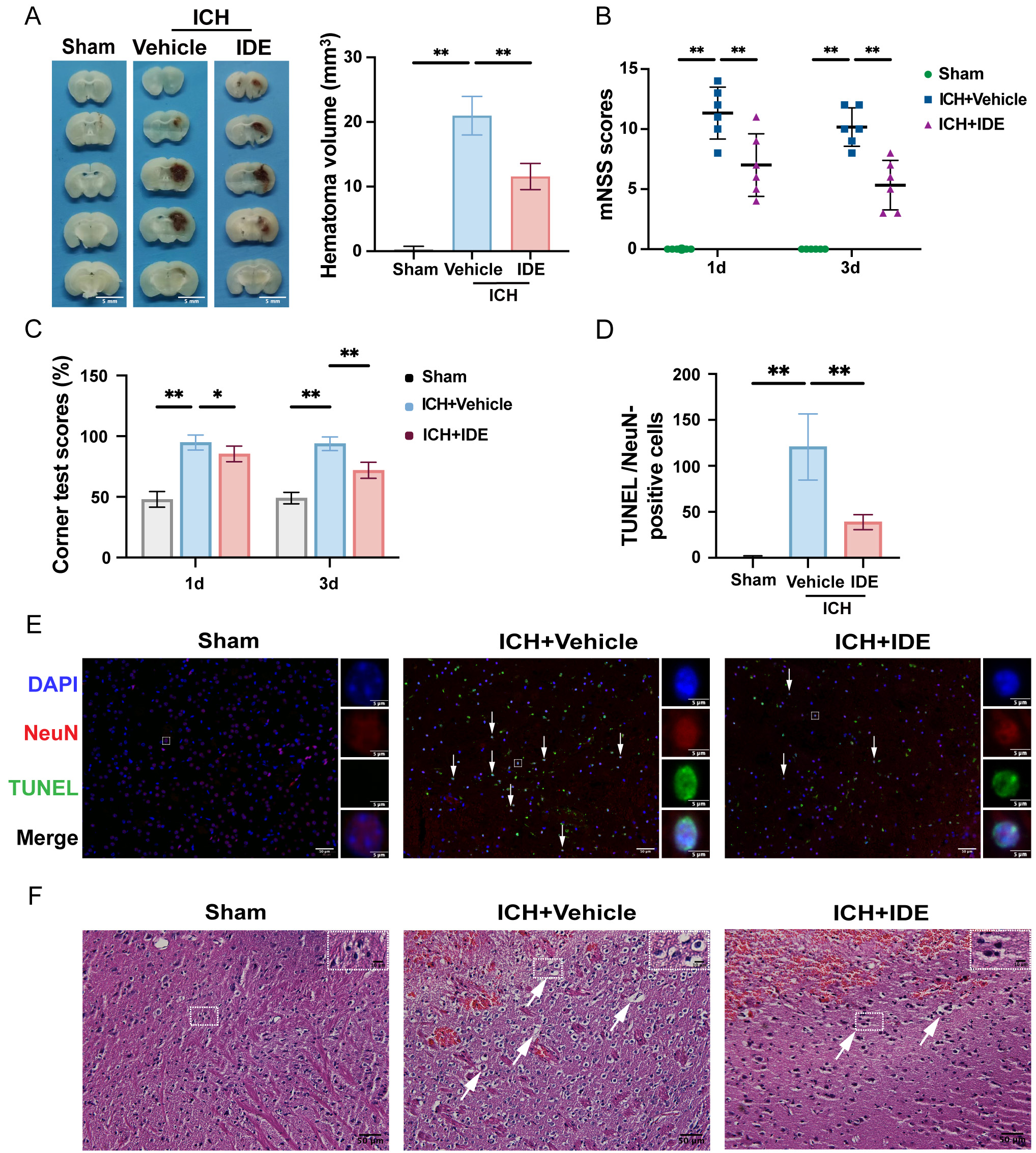

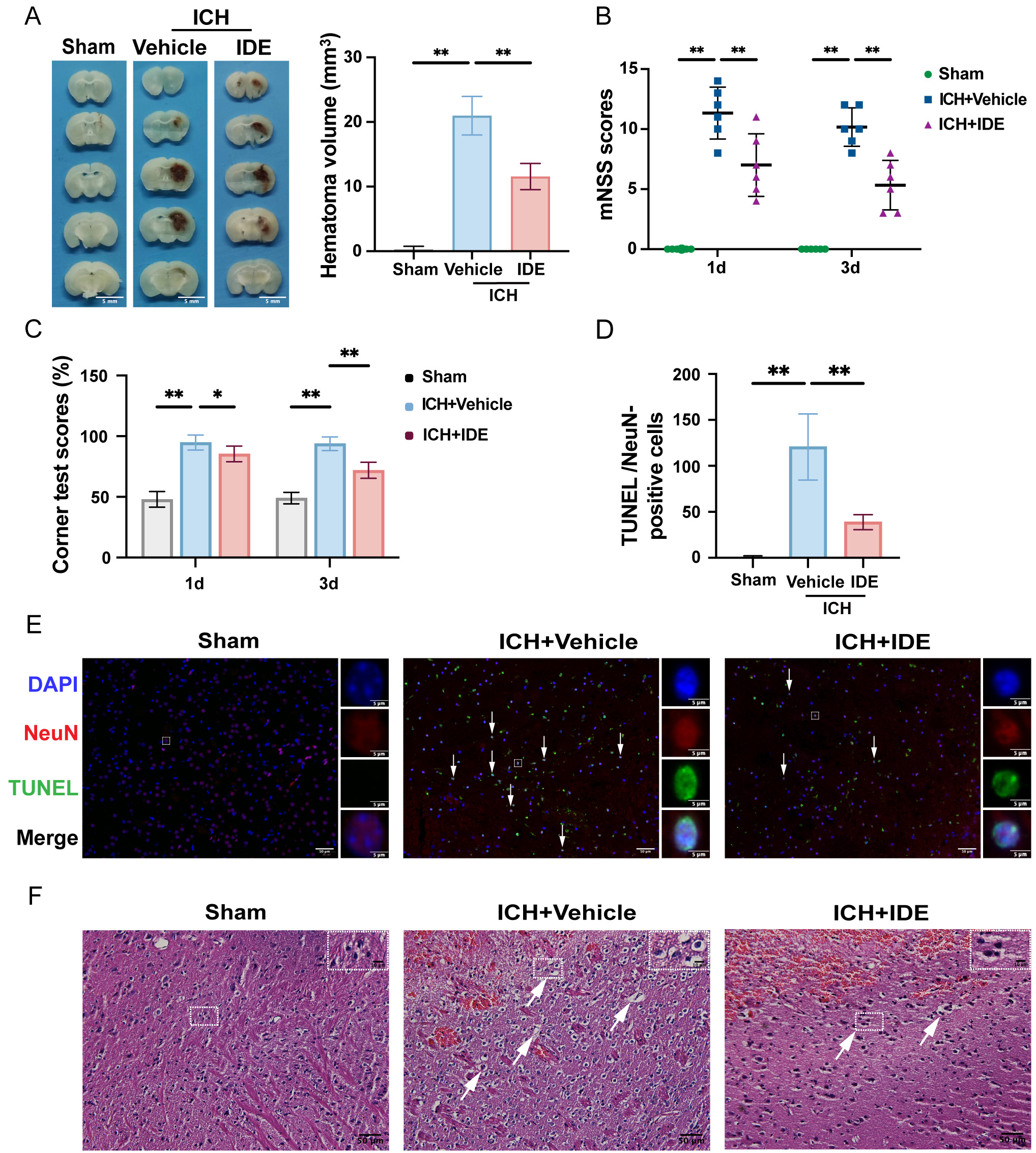

The hematoma volumes were quantified using representative brain section images,

revealing a significant reduction in hematoma volume in IDE-treated mice compared

to those in the ICH + Vehicle group (Fig. 2A, p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Effects of IDE on ICH-induced brain injury and neurological

deficits in mice. (A) Representative coronal sections of the brain tissue were

prepared after formaldehyde fixation to evaluate and quantify hematoma volume

(mm3) (scale bar = 5 mm, n = 5). (B,C) Neurological function was assessed

using the mNSS test and corner test before ICH and on days 1 and 3 post-ICH (n =

6). (D) The number of TUNEL/NeuN-positive cells was quantified (n = 5). (E)

Representative images of TUNEL staining are presented, with DAPI (blue),

TUNEL-positive cells (green), NeuN (red) labeling, and white arrows indicating

apoptotic neurons (scale bar = 50 µm) for each group are shown, with enlarged views of selected neurons within the white rectangles (scale bar = 5 µm). (F) Representative H&E staining

images for each group are shown, with enlarged views of selected cells within the

white rectangles. Representative H&E staining images (scale bar = 50 µm) for each group are shown,

with enlarged views of selected cells within the white rectangles (scale bar = 10 µm). Values are expressed as the mean

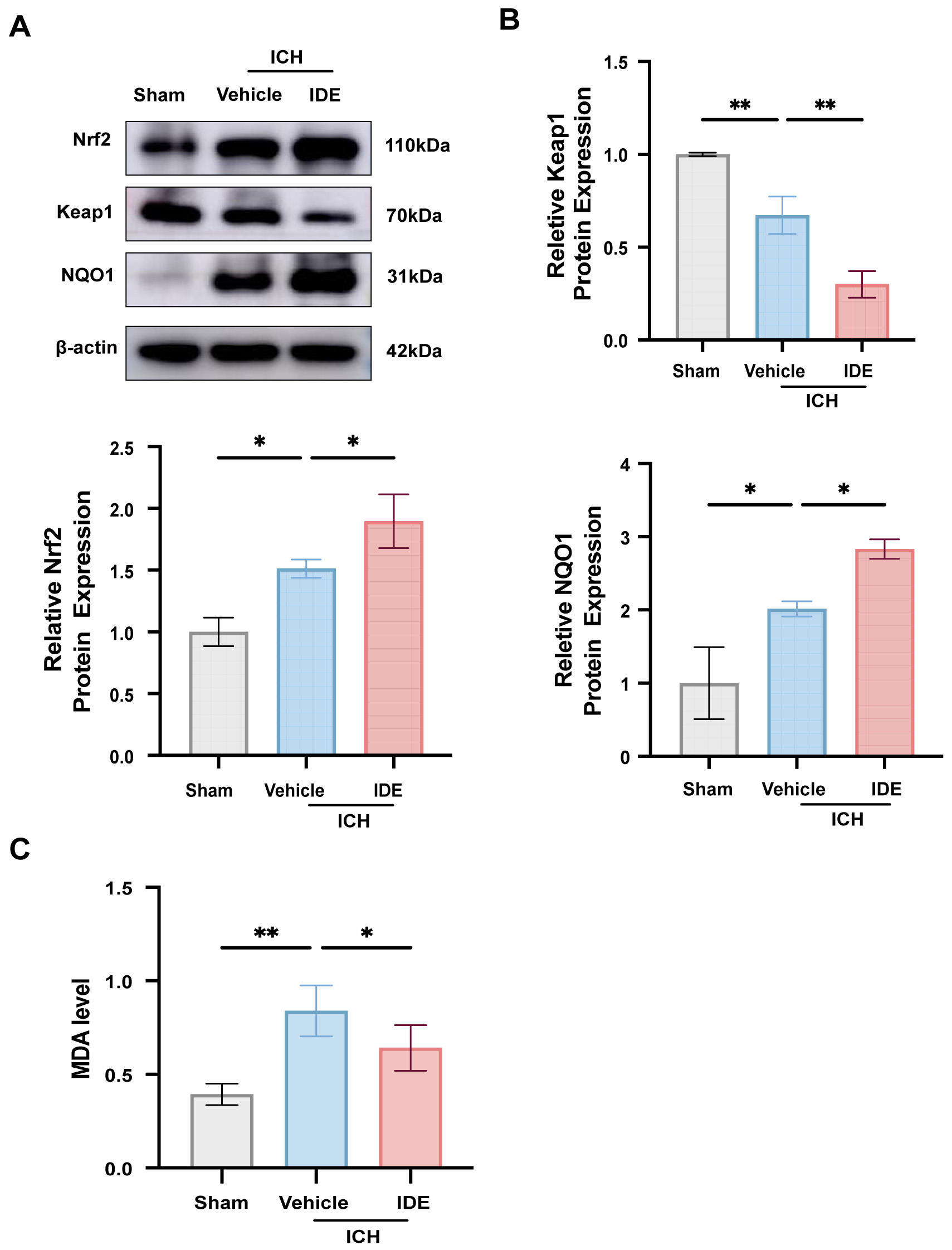

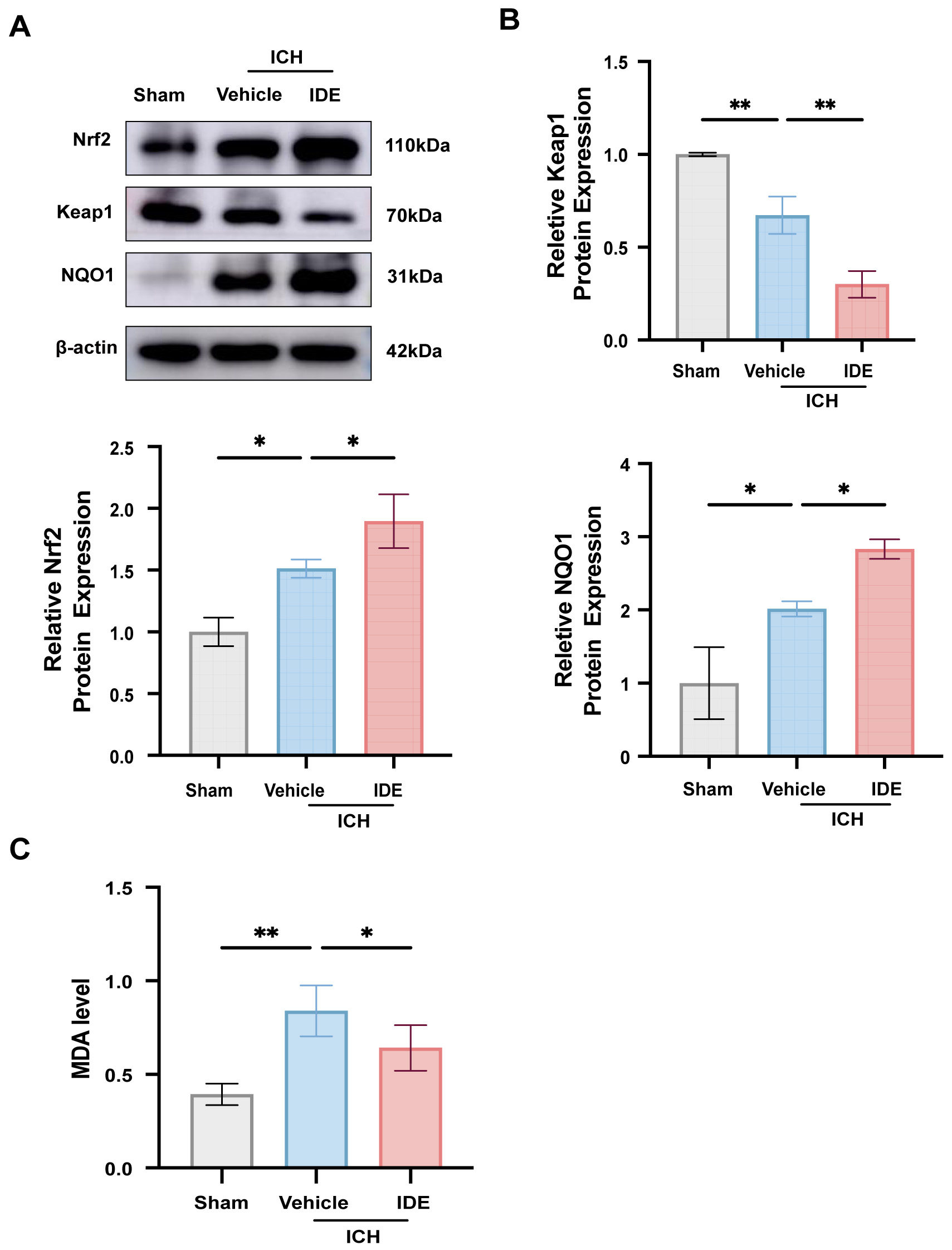

To assess the anti-oxidative stress effects of IDE, western blotting was used to

evaluate the protein levels of Keap1, Nrf2, and its downstream effector NQO1 in

perihematomal brain tissues. Compared with the sham group, the ICH + Vehicle

group exhibited elevated levels of Nrf2 and NQO1 (Fig. 3A,B, p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effects of IDE on oxidative stress after ICH. (A,B) The

expression levels of Nrf2, Keap1 and NQO1 were analyzed using western blotting

techniques across all experimental groups, followed by quantitative assessment (n

= 3). (C) MDA level was measured in each group (n = 6). Values are expressed as

the mean

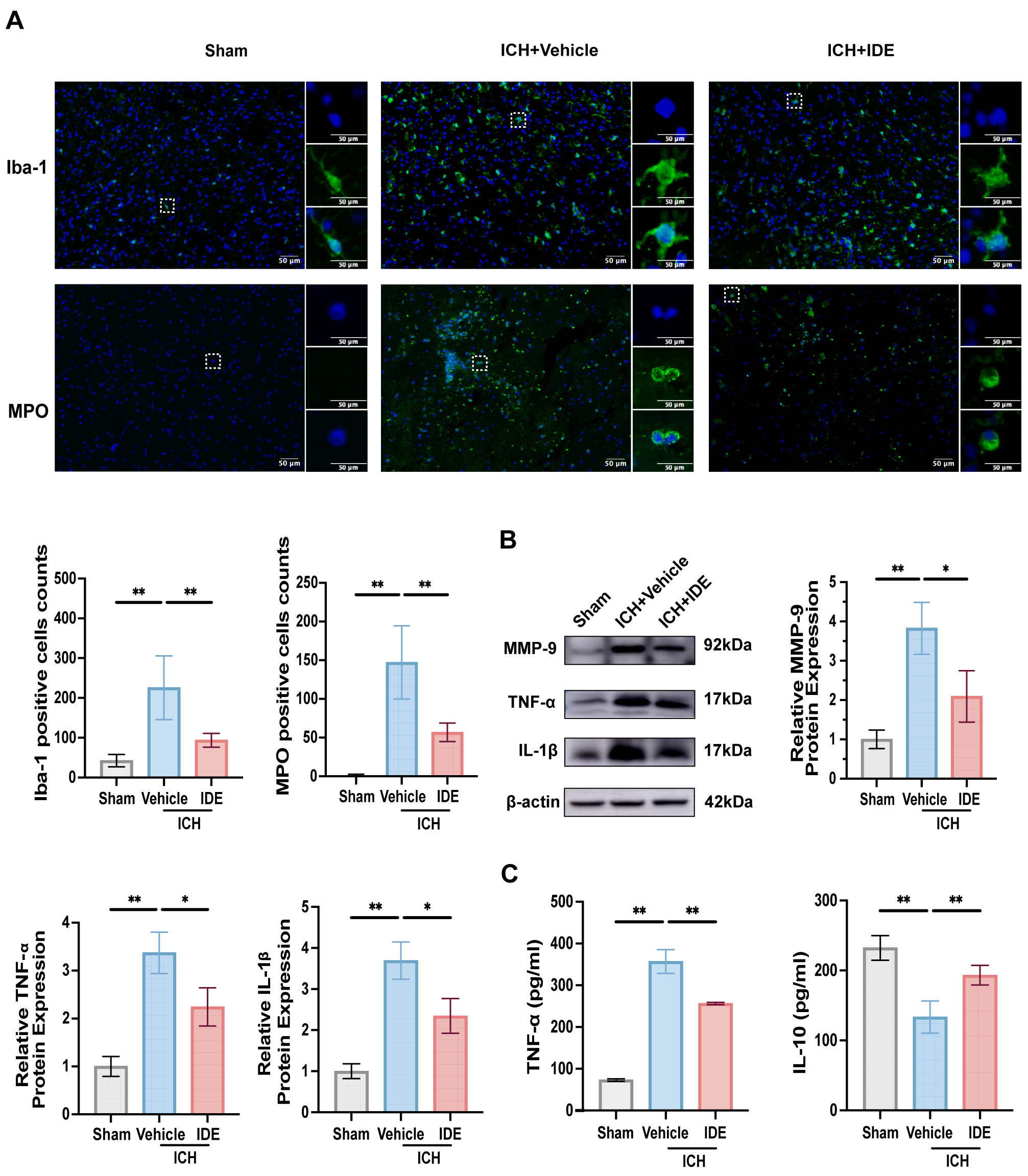

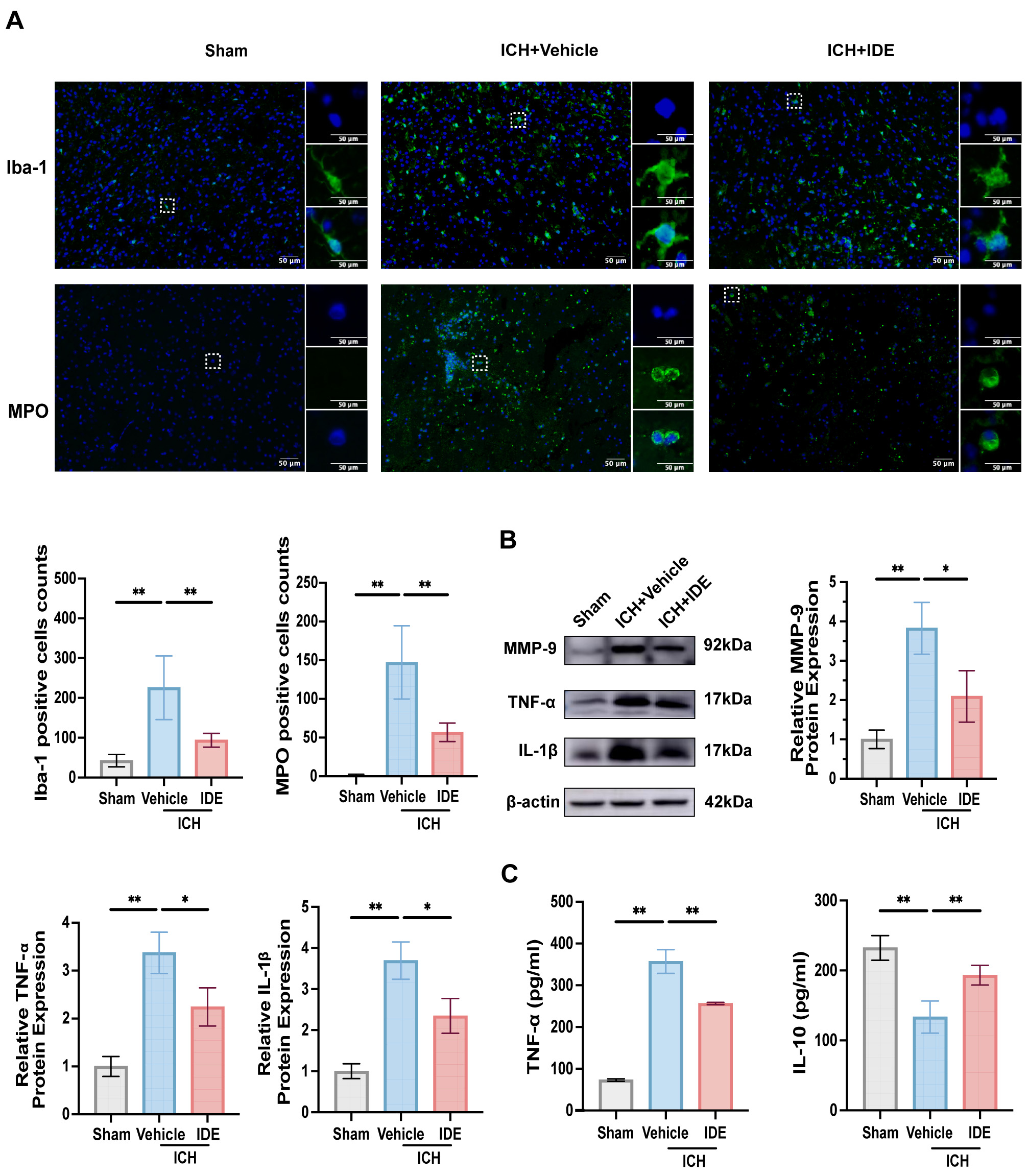

To evaluate the effects of IDE treatment on neuroinflammation,

immunofluorescence staining of Iba-1 (an indicator of microglial activation) and

MPO (an indicator of neutrophil infiltration) in the perihematomal region was

performed. In the resting state, microglia had an elongated rod-like morphology.

However, following ICH, the microglia in the ICH + Vehicle group displayed an

amoeboid shape with enlarged cell bodies, indicative of activation. However,

IDE-treated mice demonstrated significant reductions in both Iba-1 and

MPO-positive cells, suggesting decreased microglial activation and neutrophil

recruitment (Fig. 4A, p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Effects of IDE on microglia, neutrophils, and inflammatory

factors release after ICH. (A) Representative immunofluorescence staining for

Iba-1 and MPO was performed in the ipsilateral basal ganglia for each group, with

magnified views of selected cells shown within the solid rectangles (scale bar =

50 µm, n = 6). (B) Western blot analysis was conducted to evaluate MMP-9,

TNF-

Further analysis of the western blotting results indicated reduced expression of

MMP-9, IL-1

These findings imply that IDE inhibits neutrophil recruitment and microglial activation, which modulates the release of inflammatory chemicals to exert anti-neuroinflammatory effects.

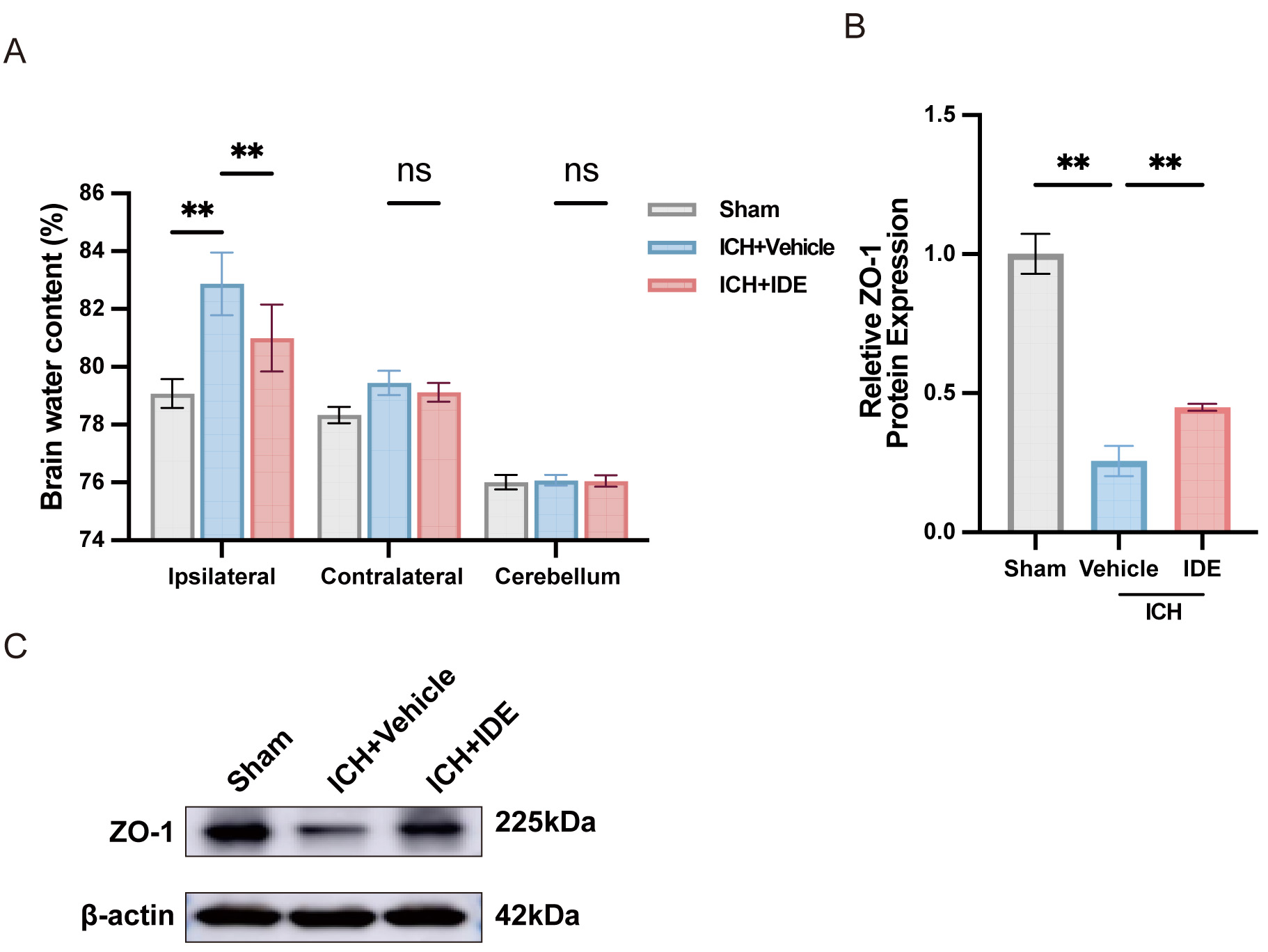

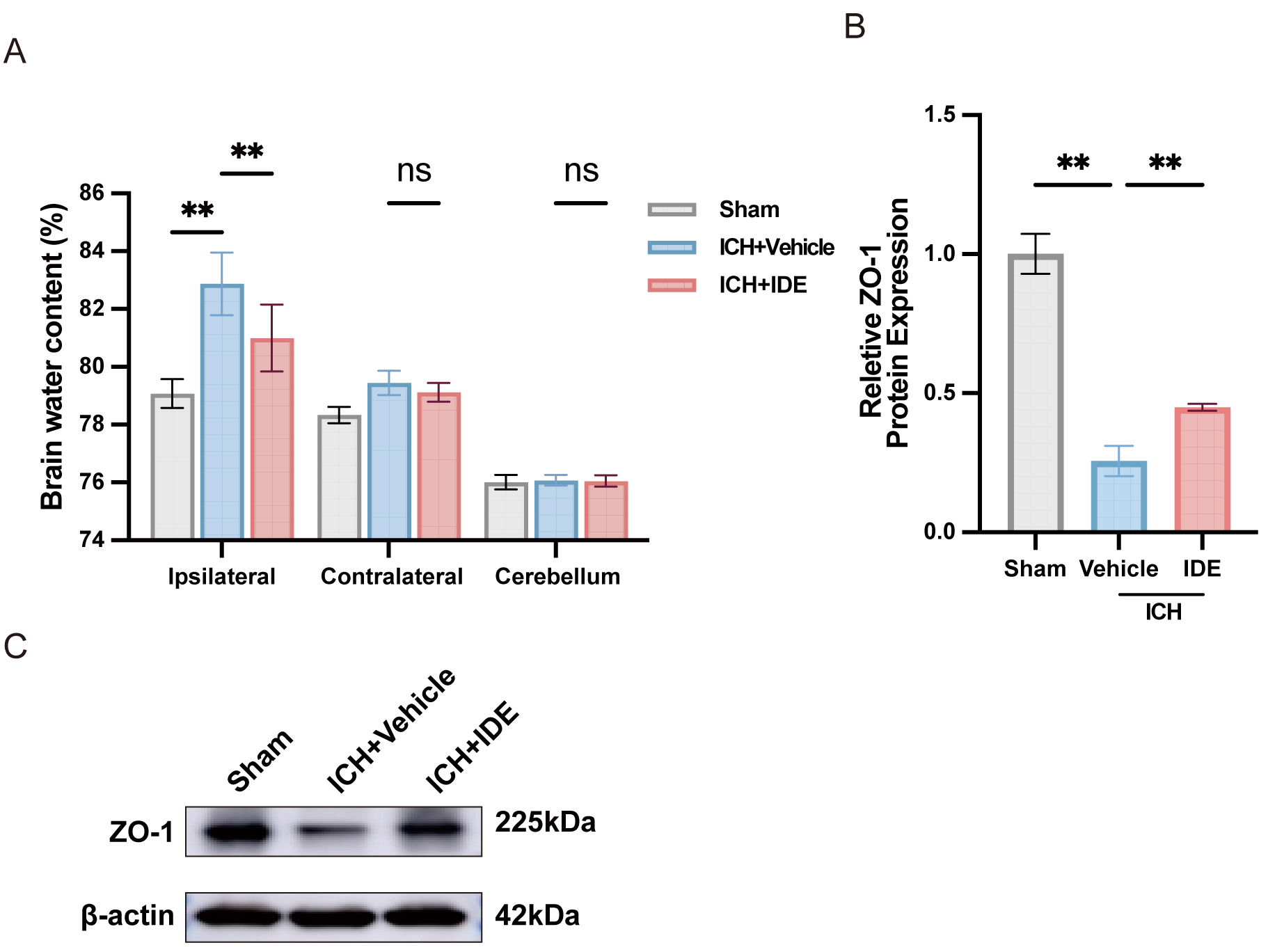

To assess the effects of IDE treatment on brain edema following ICH, the BWC was

measured in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres as well as in the

cerebellum. IDE treatment significantly reduced the BWC in the ipsilateral

hemisphere, indicating a protective effect against brain edema in the acute phase

of ICH (Fig. 5A, p

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Effects of IDE on perihematomal edema and BBB dysfunction after

ICH. (A) BWC was examined following ICH (n = 6). (B,C) Western blot analysis of

ZO-1 expression in each group, with quantification analysis (n = 3). Values are

presented as the mean

SBI contributes markedly to neurological disability and poor prognosis following ICH [30]. While the primary injury is a direct consequence of the physical presence of the hematoma, the secondary injury involves a cascade of pathological processes, including the development of brain edema, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation, ultimately leading to BBB disruption, neuronal damage, and progressive brain injury [31]. This study offers initial evidence that IDE treatment attenuates neuroinflammation in acute ICH by suppressing microglial activation, modulating the release of inflammatory mediators, and reducing neutrophil infiltration. Furthermore, IDE may alleviate oxidative stress in the acute phase of ICH by activating the Keap1/Nrf2/NQO1 pathway, thereby promoting hematoma resolution and improving neurological recovery (Fig. 6, Table 1).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

IDE alleviated neurological function after ICH via inhibiting neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, edema, and BBB dysfunction. ARE, antioxidant response element. Created with www.BioRender.com.

| Category | Findings |

|---|---|

| Temporal expression levels of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation | Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation reach their maximum levels three days after ICH. |

| Neurological dysfunction | IDE mitigates brain damage and neurological impairments during the acute phase of ICH, supporting its potential as a neuroprotective agent. |

| Oxidative stress | IDE activates the Nrf2 pathway, strengthening antioxidant defenses and lowering oxidative damage. |

| Neuroinflammation | IDE attenuates neuroinflammation by suppressing microglial activation, neutrophil recruitment, and pro-inflammatory cytokine release. |

| Brain edema and BBB disruption | IDE preserves BBB integrity and reduces brain edema. |

The findings indicated that oxidative stress and inflammatory responses peak on day 3 post-ICH, consistent with prior experimental and clinical studies. Studies have shown that oxidative stress markers, including Nrf2, MDA, and 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), reach their highest levels on day 3 following experimental ICH, marking a critical window for cellular damage and therapeutic intervention [27, 32]. Similarly, the levels of inflammatory markers also peak at this time point, coinciding with microglial activation and neutrophil infiltration in the perihematomal region [33, 34]. Clinical studies have also reported comparable temporal patterns, suggesting that the acute phase post-ICH represents both a period of severe injury and the initiation of repair mechanisms [33, 35]. Given the significance of this time window, day 3 post-ICH was selected as the optimal observation point for assessing the neuroprotective effects of IDE treatment.

Neuroinflammation plays a pivotal role in SBI following ICH [7, 36]. The

infiltration of extravasated blood into the brain triggers a robust

neuroinflammatory response, with microglia being the first non-neuronal cells to

react, ultimately inducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [37].

Inhibition of microglial activation mitigates brain damage following hemorrhagic

stroke [38]. Previous studies have demonstrated the potent anti-inflammatory

function of IDE [39, 40], with one study indicating that IDE attenuates

neuroinflammation in ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury by inhibiting the

activation of the Nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor protein 3

(NLRP3) inflammasome in the microglia [22]. While both ICH and IR involve

oxidative stress and inflammation as vital drivers of secondary injury, their

pathological mechanisms differ in terms of timing and extent. IR injuries result

primarily from oxidative stress caused by cellular hypoxia and subsequent

inflammatory activation, whereas ICH-induced secondary injury is characterized by

hematoma formation, blood metabolite-induced neuroinflammation, and oxidative

stress [41]. The present results demonstrate that IDE significantly reduces

microglial activation and neutrophil infiltration while modulating the expression

of IL-1

Besides neuroinflammation, oxidative stress aggravates SBI following ICH. Various factors contribute to oxidative stress, including red blood cells and their metabolites (heme, hemoglobin, and iron), thrombin, and neuroinflammatory responses surrounding the hematoma [42]. IDE is recognized as a potent antioxidant [43]. A previous study demonstrated that IDE significantly reduced MDA levels while increasing those of the Nrf2 downstream factor NQO1, thereby protecting mice from acute colitis through antioxidant pathways [44]. In the present study, IDE treatment resulted in elevated expression of Nrf2 and NQO1, along with a reduction in its regulatory molecule, Keap1. These data suggest that IDE exerts its antioxidant effects through activation of the Keap1/Nrf2/NQO1 pathway. IDE is not a direct antioxidant but instead enhances the cell’s intrinsic defense mechanisms by suppressing free radical generation and oxidative stress, a mechanism consistent with a previous report [15].

Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress following ICH contribute to the development of brain edema by increasing BBB permeability, exacerbating hematoma-induced damage, and inducing secondary ischemic cell death [42, 45]. Therefore, reducing BBB disruption and mitigating brain edema is essential for improving ICH prognosis. The present findings further support this role, demonstrating that IDE effectively decreased BWC in the ipsilateral hemisphere, preserved BBB integrity, and upregulated ZO-1 expression. These results indicate that IDE treatment mitigates BBB disruption and brain edema following ICH. Since ICH prognosis is affected by multiple secondary injury mechanisms, targeting a single pathway may be insufficient for achieving long-term neuroprotection. This study demonstrates that IDE exerts its therapeutic effects through multiple mechanisms, including modulation of neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, BBB integrity, and brain edema. The synergistic action of these mechanisms contributes to the significant improvements in neurological function observed in the IDE-treated mice.

Despite the promising findings, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, First, this study focused primarily on the acute phase of ICH, without assessment of long-term outcomes. Second, the precise interplay and independence of the Keap1-Nrf2 antioxidant pathway require further investigation. To address these limitations, future research should extend follow-up periods to assess long-term functional recovery and neuroprotection, investigate the effects of IDE in aged animals and female mice to ensure broader translational applicability, explore combination therapies targeting complementary pathways to enhance treatment efficacy, elucidate the dual mechanistic action of IDE, and determine the independence of pathways involved, supported by in-depth analysis of Nrf2, Keap1, and NQO1 interactions, and develop optimized drug delivery methods to enhance the bioavailability of IDE and its therapeutic potential in ICH. By addressing these aspects, future studies will provide a more comprehensive insight into the role of IDE in ICH and its potential as a viable therapeutic agent.

In conclusion, the findings demonstrate that IDE treatment mitigates neurological dysfunction following ICH by suppressing microglial activation, reducing neutrophil infiltration, modulating inflammatory factor expression, inhibiting oxidative stress, preserving BBB integrity, and reducing brain edema. This study provides critical evidence supporting the potential clinical application of IDE as a novel therapeutic strategy for ICH. By targeting both neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, IDE therapy may offer an effective approach to improving outcomes in ICH patients.

Data will be available on reasonable request.

CC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing. LC: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review & editing. MX: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review & editing. NZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The animal protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University (KY2024064) and was conducted following the National Institutes of Health’s “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”.

We would like to thank the Comprehensive Research Laboratory of the Academy of Medical Science of Zhengzhou University for their support and services.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81960234, 82071331); Henan Provincial Key Medical Scientific Research Program (SBGJ202403031); Henan Provincial Medical Science and Technology Tackling Program (LHGJ20220470).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/JIN37182.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.