1 Institute of Translational Biomedicine, St. Petersburg State University, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russia

2 Institute of Experimental Medicine, Almazov National Medical Research Centre, Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, 125993 St. Petersburg, Russia

3 World Class Research Center for Personalized Medicine, Almazov National Medical Research Centre, Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, 125993 St. Petersburg, Russia

4 Neuroscience Department, Sirius University of Science and Technology, 354340 Sirius Federal Territory, Russia

5 Suzhou Key Municipal Lab of Neuroscience and Cell Signaling, Department of Biosciences and Bioinformatics, School of Science, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, 215123 Suzhou, Jiangsu, China

6 Department of Biology, School of Science, Western Caspian University, 1001 Baku, Azerbaijan

7 Graduate Program in Health Sciences, Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre, 90050 Porto Alegre, Brazil

Abstract

Filamin A (FLNA) is a key protein that binds actin filaments to transmembrane integrins and plays an important role in maintaining cell shape and signaling. In the brain, FLNA is emerging as a critical regulator of neurodevelopment, neuronal migration, actin organization, and neuromodulation. Mutations and/or aberrant expression of the FLNA gene are associated with various brain diseases, such as periventricular heterotopia, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and other disorders with impaired cognitive function and brain maldevelopment. Here, we discuss the critical role of FLNA in brain function; its interactions with receptors, integrins, and signaling molecules, as well as the implications of its activity for brain health and disease.

Keywords

- filamin A

- neuronal migration

- neurodevelopmental disorder

- cognitive impairment

- CNS signaling pathways

- brain development

The FLNA gene encodes filamin A (FLNA), an important anchoring protein best known for linking actin filaments to transmembrane integrin molecules in focal adhesions of the cell membrane, thereby playing a prominent role in maintaining cell shape and signaling across various cell types, including neurons [1, 2, 3]. FLNA and its gene FLNA are also critical for the central nervous system (CNS), especially its development [4] and signaling pathways [5]. For example, neuronal migration, a key step in brain development, is highly dependent on FLNA [6], whose interaction with various signaling molecules and membrane receptors directs neurons to their target areas, helping create functionally specialized areas of the cortex and other brain structures [7]. The role of FLNA in cellular signaling extends beyond normal physiological conditions and includes pathological interactions with receptors in various CNS diseases [5]. In the healthy brain, FLNA plays a role in the regulation and trafficking of mu-opioid receptors, since its absence leads to reduced desensitization and downregulation of opioid receptors, as well as impaired activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway by opioids [8]. In the pathological contexts of Alzheimer’s disease, FLNA interacts with the

As FLNA interacts with

| Function | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Binding to actin filaments | Forming three-dimensional networks that support cell structure and provide mechanical strength [14] | Forming isotropic, cross-linked, three-dimensional orthogonal networks with actin filaments in the cortical region [15] |

| Interaction with integrins | Binding to transmembrane integrins in focal adhesions, enabling cell adhesion and migration [16] | Interaction with integrin |

| Regulatory role in signaling pathways | Modulating various signaling pathways by linking signaling cascades to FLNA phosphorylation [17, 18] | Modulation of epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling by affecting integrin function via phosphorylation. Inducing aberrant phosphorylation/activation in pathological conditions (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease) by facilitating aberrant signaling via the |

| Regulation of cell shape | Maintaining cell shape by linking actin to structures [21] | Conferring elastic properties on F-actin networks [21] |

| Mechanotransduction | Responses to mechanical forces [22] | Linking cytoskeleton to mechanosensitive pathways [22] |

| Scaffold for signaling complexes | Acting as a scaffold for assembling signaling complexes [23] | Attaching proteins to the actin cytoskeleton and the involvement in supporting cell signaling [23] |

| Role in neurodevelopment | Essential for neuronal migration and nervous system development [24] | Neural circuit dysfunction due to FLNA mutations [25] |

FLNA is also involved in the regulation of cell adhesion and the mechanosensory apparatus, helping cells to adapt to changes in their microenvironment [22] by modulating the cytoskeletal response to external signals, thereby influencing cell movement and positioning [26]. Such ability to adapt is particularly important for neurons that need to remain flexible for the constant remodeling of synapses and neural networks that underlie learning and memory [27]. Collectively, this suggests that FLNA may serve not only as an essential structural element, but also a key regulator of cellular dynamics and intercellular interaction in the brain. Here, we review the role of FLNA and its gene in the brain, and discuss the interactions of this protein with other molecules and the consequences of mutations in FLNA for the brain and behavior. Our improved understanding of the roles of FLNA in the CNS may provide novel perspectives for studying neurodevelopment and neuropathogenesis.

FLNA is located on the X chromosome (Xq28) and consists of 48 exons and 47 introns that span ~26 kb of genomic DNA [28, 29]. This chromosomal location is significant as it links FLNA mutations to unusually X-linked dominant disorders, which predominantly affect females due to the random inactivation of one X chromosome [30]. Human FLNA represents a large 280-kDa dimeric protein, with each monomer containing 2647 amino acid residues [23] with an N-terminal actin-binding domain, each consisting of two calmodulin-like sequences followed by 24 immunoglobulin-like domains (Ig-like domains, Fig. 1) [21]. The C-terminal part of FLNA, consisting of nine immunoglobulin-like domains, forms a compact but flexible structure that is responsible for dimerization, important for actin cross-linking and interaction with various signaling proteins (such as

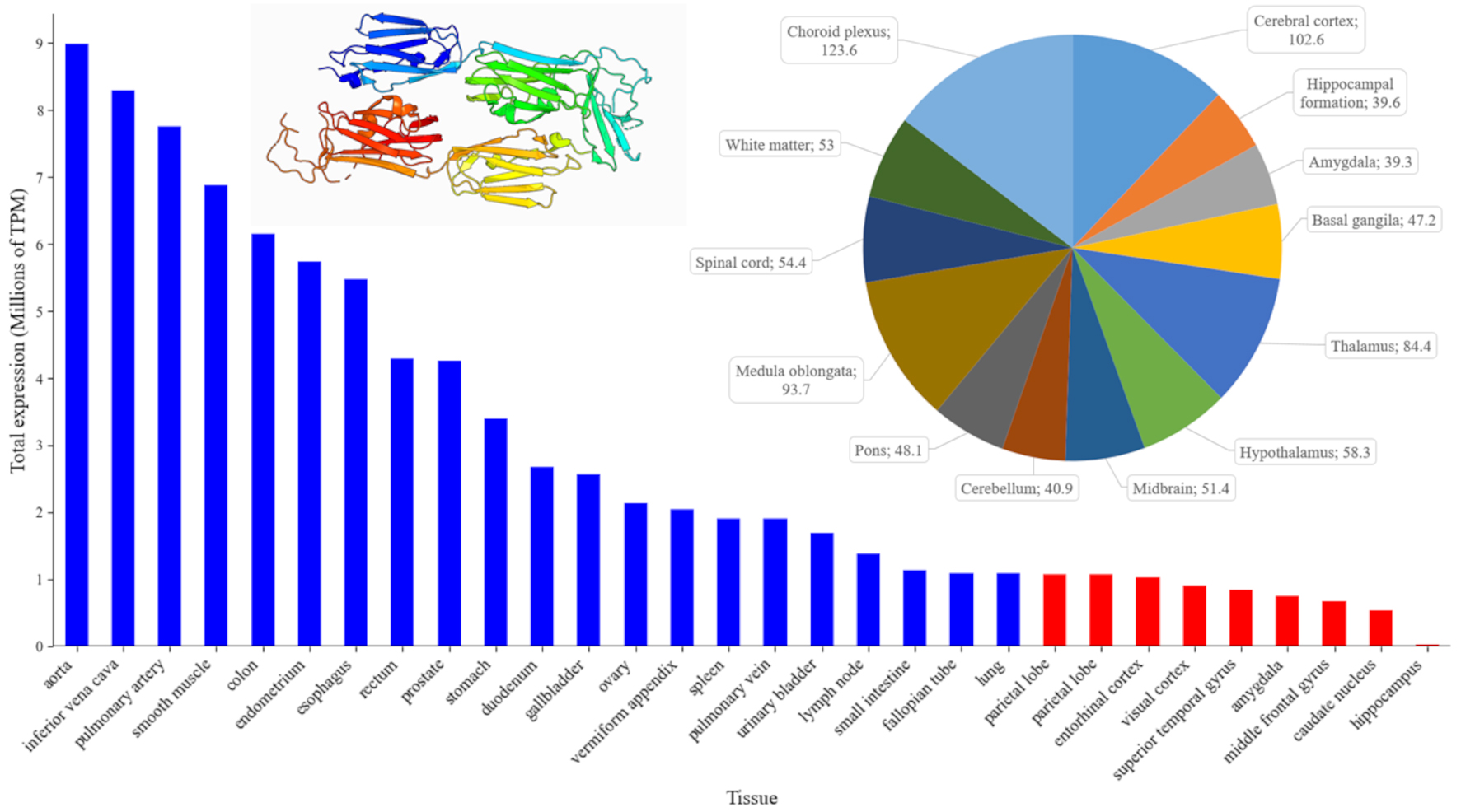

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Patterns of FLNA expression across human organs (blue bars) and major brain regions (red bars). The bar chart ranks the top human tissues by mean gene expression, measured in Transcripts Per Million (TPM) using the ENSEMBL database (https://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Gene/Summary?db=core;g=ENSG00000196924;r=X:154348524-154374634, accessed September 2024). The pie chart (top right) displays the normalized gene expression levels (nTPM) in different regions of the human brain, using data from the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000196924-FLNA/brain, accessed September 2024). Each pie chart segment is labeled with specific brain regions and their corresponding expression values, providing a detailed view of FLNA distribution within the central nervous system (CNS) (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000196924-FLNA/brain, accessed September 2024). Inset: Crystal structure of 19–21 Ig-like domains of human filamin A protein (FLNA), according to the Protein Database (PDB, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/, PDB ID: 2J3S, plotted in pyMOL (https://www.pymol.org, assessed September 2024). For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the online version of this article.

FLNA is a generally evolutionarily conserved gene, with its sequence in humans being 77.95%, 86.09%, and 86.35% homologous to those of mice, rats, and zebrafish, respectively, based on Basic Local Alignment Search Tool for Nucleotides (BLASTn) analyses [33]. This gene is widely expressed in various tissues, including smooth and skeletal muscle, vascular endothelium, and the brain [7, 34] (Fig. 1). FLNA expression is regulated by various transcription factors and can be altered in response to external signals and stress conditions [17]. For example, microRNA-200c can decrease FLNA levels by inhibiting the transcription factors c-Jun, myocardin related transcription factors (MRTFs), and serum response factor (SRF) [35]. The transforming growth factor beta (TGF-

In the brain, FLNA plays an important role in early development by controlling neuronal migration and differentiation [7, 38]. Fig. 1 summarizes its expression in different brain structures, showing the highest expression in the vascular plexus that implicates FLNA in the production and regulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). FLNA may indeed be important for maintaining the integrity and structure of the cells of this epithelium, as well as for regulating the movement of ion channels and receptors that play an important role in CSF secretion [39]. The second highest level of FLNA expression is observed in the cerebral cortex, implicating FLNA in the development and functioning of cortical neurons, including their migration and structural organization. In line with this notion, human FLNA mutations disrupt neuronal migration in the cerebral cortex, leading to PH [40].

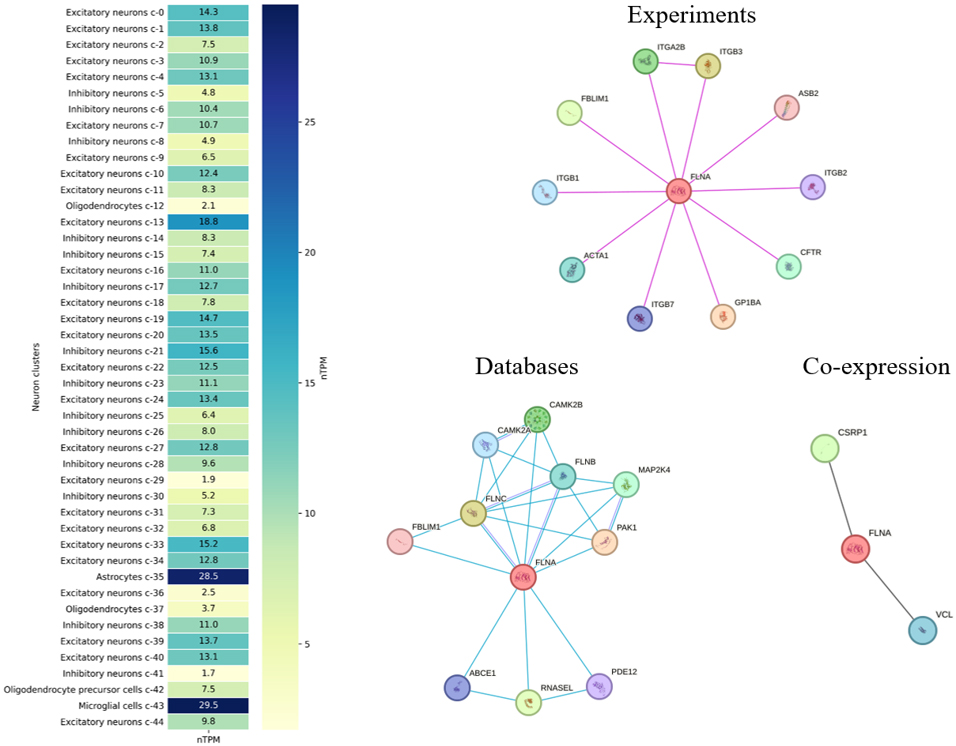

Fig. 2 also illustrates FLNA expression across different brain cell types. For example, FLNA expression is markedly lower in oligodendrocytes and their precursors, suggesting a somewhat limited role for FLNA in these cells. Moderate FLNA expression is observed among various types of neurons, both excitatory and inhibitory, with some variation likely reflecting the diversity of functional activity of FLNA in these cells. In contrast, its highest expression in astrocytes and microglia strongly implicates FLNA in maintaining the brain environment and regulating neuro-immune responses.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Heatmap of FLNA expression across various neuronal and glial cell clusters in the human brain, measured in normalized Transcripts Per Million (nTPM), according to the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000196924-FLNA/brain, accessed September 2024). The heatmap shows FLNA expression in excitatory and inhibitory neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. The right three panels display the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network for FLNA (central red circle), with interactions classified by data type, according to the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING database, https://string-db.org/, accessed September 2024; pink lines denote experimentally validated interactions, blue lines denote biological databases, and black lines showgene co-regulation or similarity). ITGA2B, integrin alpha-IIb; PAK1, p21 activated kinase 1; CSRP1, cysteine and glycine rich protein 1; ITGB, integrin subunit beta; ASB2, ankyrin repeat and SOCS box containing 2; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; GP1BA, glycoprotein Ib platelet subunit alpha; ACTA1, actin alpha 1 skeletal muscle; FBLIM1, filamin binding LIM protein 1; CAMK2B, calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II beta; FLNB, filamin B; FLNC, filamin C; ABCE1, ATP binding cassette subfamily E member 1; RNASEL, ribonuclease; PDE12, phosphodiesterase 12; MAP2K4, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4; VCL, vinculin. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the online version of this article.

Neuronal migration is key for brain development, ensuring the proper placement of neurons in different brain structures [41]. Importantly, FLNA regulates the cytoskeleton that is necessary for the movement of neurons from their origin to final location in the cerebral cortex or other brain areas [42]. FLNA also interacts with signaling molecules (e.g., Rho GTPases) that regulate actin dynamics, thereby coordinating the cytoskeletal rearrangements that are essential for directed neuronal movement [43]. The regulation of the cytoskeleton, in turn, influences the morphology of cortical neurons, facilitating their transformation from a multipolar to a bipolar form, which is critical for radial migration [42]. Disruptions in FLNA function impede neuronal migration and cause brain malformations [44]. For example, FLNA is involved in radial glia (RG) proliferation and polarity [45]. As RG serve as a scaffold for migrating neurons, the role of FLNA in maintaining their structural integrity is crucial for guiding neurons to their correct positions in the developing brain [46]. By forming a physical connection between integrins and the actin cytoskeleton, FLNA promotes the migration of various brain cells, including RG [43], neurons [47], neural progenitors [48], oligodendrocytes [49], astrocytes [44], and other cell types [50].

FLNA also plays a role in neurogenesis, which involves the proliferation of neural precursors and their differentiation into mature neurons [7]. For example, it controls the proliferation of neural progenitors and the overall cortex size by regulating the phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) by the mitosis inhibitor protein kinase (Wee1) [51]. FLNA also affects the growth of neural progenitors by controlling the expression and placement of cell cycle proteins (e.g., Cdk1, which plays a vital role during the G2/M (transition from the growth G2 stage to mitosis) phase of the cell cycle, ensuring proper progression and timing) [48]. The loss of FLNA function slows proliferation due to extended cell cycle phases and impacts the initial differentiation of progenitors [51]. In turn, such impaired proliferation can lead to microcephaly or other cortical malformations, highlighting the critical role of FLNA in early brain development [52]. Additionally, FLNA regulates dendritogenesis and spinogenesis, thereby promoting a balanced ratio of excitatory and inhibitory inputs, suggesting that mutations in FLNA can lead to neural circuit dysfunction [25].

FLNA is essential for maintaining cell shape, organizing the actin cytoskeleton by binding actin filaments to form three-dimensional networks that provide mechanical strength and flexibility to cells, allowing them to adapt to changes in their environment [53]. This function is key for maintaining the mechanical stability of the plasma membrane and cellular cortex, shaping cell structure, enabling mechanical responses, and facilitating cell movement. Recent atomic force microscopy data how that the Ig-fold domains of FLNA can reversibly unfold when subjected to forces of 50–220 pN, allowing the molecule to extend far beyond its natural length [54].

FLNA is also involved in the transmission of mechanical signals from the extracellular matrix to the cell cytoskeleton [17]. Partnering with FilGAP (FLNA-binding GTPase-activating protein specific for Rac GTPase) and

FLNA interacts with integrins and other adhesion molecules to promote cell adhesion [50, 59], which is key for linking cell surface receptors to the cytoskeleton, thereby stabilizing cell adhesion sites (focal adhesions) [60]. FLNA binds to integrins through its Ig-like repeats, facilitating connection of the actin cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix [61], which is vital for maintaining cell shape, enabling cell migration, and transmitting mechanical signals from the extracellular environment to the cell interior [50]. Moreover, the interaction of FLNA with integrins is regulated by mechanical forces, as its molecule undergoes conformational changes that expose new binding sites, hence enhancing its interactions with integrins and other signaling proteins [17, 62]. This dynamic process helps cells to adapt to varying mechanical environments, which is particularly important for tissue repair [1]. FLNA also interacts with proteins that regulate expression and recycling, such as vimentin and protein kinase C (PKC) epsilon type, which regulate the expression and recycling of integrins on the cell surface. These integrin-regulating proteins play an important role in the CNS, particularly in neuronal migration and the formation of neuronal connections, especially in the context of neuronal migration and the formation of neuronal connections [7, 50]. This complex regulatory mechanism ensures that integrins are properly positioned and functional, further supporting robust cell adhesion and spreading [63].

FLNA interacts with various signaling molecules, including cell-surface receptors and cytoplasmic proteins necessary for cell growth, survival, and differentiation [37], which allows cells to adapt to changes in their environment and maintain homeostasis. FLNA also acts as a

Analyses using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database link FLNA to the human MAPK signaling (hsa04010) and the focal adhesion (hsa04510) cascades, complementing the pathways discussed above. Examining the known protein-protein interactions (PPIs) of human FLNA (Fig. 2) using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING database) (https://string-db.org/) shows significant enrichment of cell adhesion processes, including general cell adhesion, cell-cell adhesion, and cell-matrix adhesion. In addition, platelet aggregation and wound healing-related proteins are present in PPIs, emphasizing the role of FLNA in the regulation of processes related to damage response and tissue repair. All identified processes showed high statistical significance with extremely low false discovery rates (FDRs). In addition, molecular function analysis confirms that FLNA-interacting proteins play a key role in binding cell adhesion molecules, integrins, and cytoskeleton proteins. Analysis of cellular components revealed significant enrichment in focal adhesions, cell-cell junctions, and integrin complexes, implying a role for FLNA in maintaining structural connections and signaling processes at the cell membrane level.

As shown in Fig. 2, integrin alpha-IIb (ITGA2B) is a predicted functional partner of FLNA, and their interaction may play an important role in cell adhesion and thrombosis [65]. Disruption of ITGA2B regulation inhibits integrin signaling pathways, which impairs cellular function and cytoskeletal remodeling [66]. Thus, the interaction between the FLNA and ITGA genes is involved in cell adhesion processes, affecting cytoskeleton maintenance and mediating cell migration and adhesion mechanisms [67]. The interaction of FLNA with p21 activated kinase 1 (PAK1), which is involved in the regulation of the cytoskeleton and cell morphology, is also important for cell movement dynamics and signaling [68, 69]. In addition, the interaction of FLNA with cysteine and glycine rich protein 1 (CSRP1) may play a role in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. CSRP1 plays significant roles in cellular differentiation, development, and actin cytoskeleton regulation, and it can bind to actin, contributing to cytoskeletal organization [70]. Thus, these interactions of FLNA with ITGA2B, PAK1, and CSRP1 enable a complex coordination of cytoskeletal and signaling pathways required to maintain cell structural integrity and functional activity in response to various stimuli. Similar to the described interactions, each of the genes in Fig. 2 can be considered in the context of a functional partnership with FLNA.

Mutations in FLNA (point-mutations, deletions, or duplications) alter FLNA functionality to cause various congenital anomalies [21] such as PH, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), skeletal dysplasia, neuronal migration abnormalities, and intellectual disability [71, 72]. Genetic analyses, including genome-wide association studies (GWAS), have identified genetic variations associated with susceptibility to various brain diseases. For example, PH marked by the presence of neuronal nodules outside their usual location, specifically along the lateral ventricles, is often caused by mutations in the X-linked FLNA gene [73], and while symptoms vary widely, they commonly include treatment-resistant epileptic seizures [74, 75]. A novel heterozygous intronic variant of FLNA (NM_001110556.1, c.4304-1G

Classic EDS is an inherited connective tissue disorder characterized by stretchable, fragile, and soft skin, slow wound healing, and joint hypermobility [72, 77]. The relationship between EDS and PH is particularly evident in EDS-PH, characterized by features of both EDS (skin and joint manifestations) and PH due to mutations in FLNA, leading to the connective tissue abnormalities seen in EDS and the neuronal migration defects seen in PH. Individuals with FLNA mutations may also exhibit a combination of symptoms of both EDS and PH, demonstrating the pivotal role of FLNA in both connective tissue integrity and neurodevelopment.

Other pathologies linked to FLNA include otopalatodigital spectrum disorders (otopalatodigital syndrome, type I, otopalatodigital syndrome, type II, Melnick-Needles syndrome, and frontometaphyseal dysplasia) that arise from missense mutations [78, 79]. Additionally, FLNA is mutated in X-linked chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction with CNS involvement, a condition marked by gastrointestinal dysmotility due to impaired smooth muscle function [73]. Terminal osseous dysplasia, also related to FLNA mutations, leads to skeletal abnormalities particularly affecting the terminal phalanges [80]. Furthermore, FLNA mutations can result in X-linked cardiac valvular dysplasia, a condition characterized by abnormalities in the structure and function of heart valves [81]. All these pathologies underscore the diverse and critical roles of the FLNA gene in human development and disease, highlighting its involvement in both connective tissue and neuronal disorders as well as in more systemic conditions (Table 2, also see [77, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94]).

| Disease | Details | Main symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Periventricular nodular heterotopia | A neuronal migration disorder where neurons form nodules along the lateral ventricles instead of migrating to the cerebral cortex [83] | Epileptic seizures, dyslexia, focal or multifocal seizures [83, 84] |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | A connective tissue disorder characterized by hyperelastic skin, joint hypermobility, and tissue fragility [77, 85] | Skin fragility, hypermobile joints, easy bruising [77] |

| Otopalatodigital spectrum disorders | Include otopalatodigital syndrome types I and II, Melnick-Needles syndrome, and frontometaphyseal dysplasia [86] | Skeletal anomalies [87] |

| Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction | A disorder with severe gastrointestinal motility impairment due to smooth muscle dysfunction [88] | Intestinal obstruction, abdominal pain [89] |

| Terminal osseous dysplasia | A rare skeletal disorder affecting terminal phalanges, with distinctive skin lesions and limb anomalies [90] | Skeletal abnormalities, skin lesions, limb deformities [91, 92] |

| X-linked cardiac valvular dysplasia | A condition with abnormal heart valve development [93] | Heart failure, valvular regurgitation, chest pains, shortness of breath [94] |

In addition to genetic alterations, CNS expression of FLNA is significantly altered in PH, where mutations in FLNA disrupt normal neuronal migration, leading to the formation of ectopic neuronal nodules in the brain [7]. Recent studies have identified a specific reading deficit in patients with PH, highlighting a link between PH and dyslexia [95] characterized by poor reading but normal intelligence [96]. Moreover, reading fluency deficits in patients with PH can be associated with focal white matter defects adjacent to the gray matter nodules, indicating that disruptions in white matter integrity may underlie the observed cognitive impairments [97]. Cognitive assessments of individuals with FLNA loss-of-function variants show an average intelligence quotient (IQ) of 95, yet a high prevalence of dyslexia, indicating that similar neurodevelopmental processes might underlie both PH and dyslexia [98]. Disruptions in neuronal migration and connectivity, as seen in PH, potentially contribute to the milder cognitive deficits observed in dyslexia, such as impairments in reading fluency [99]. Furthermore, patients with FLNA-associated PH present difficult-to-treat seizures [100]. Interestingly, a boy with West syndrome recently presented a de novo missense FLNA variant without PH (typically seen in such genetic cases) on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), yet exhibited severe psychomotor delay and refractory seizures, suggesting that FLNA mutations may cause overt neurological impairments even in the absence of visible structural brain abnormalities [101].

Collectively, these findings support the emerging important role of FLNA in both neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders, and the link between white matter integrity abnormalities and FLNA can underlie various cognitive impairments beyond structural anomalies. Moreover, the role of FLNA in Alzheimer’s disease reveals its active involvement in key pathogenetic processes, including the facilitation of toxic signaling pathways linked to the amyloid beta (A

Building on its role in astrocytes, the involvement of FLNA in CNS processes extends to broader mechanisms of neuroinflammation and cellular dysfunction. Indeed, FLNA is abundant in reactive astrocytes, and the number of FLNA-positive astrocytes increases as Alzheimer’s disease severity rises [102]. Recent evidence also links aberrant FLNA to Alzheimer’s disease [10], as altered conformation of this protein facilitates toxic signaling pathways associated with the A

Abnormal FLNA conformation enhances the interaction between A

Furthermore, the role of FLNA in the regulation of cytoskeletal integrity and intracellular trafficking also implicates it in neurodegenerative processes. For example, its interaction with A

Animal models are important tools for studying FLNA and its gene function, as well as their roles in neuronal migration, brain development, and other CNS processes [114]. Rodent (mice and rats) and zebrafish (Danio rerio) models have been widely utilized in this field [115, 116, 117, 118, 119]. For example, paralleling mutations in human FLNA that interfere with neuronal migration to the cerebral cortex leading to cardiovascular abnormalities, complete FLNA ablation in mice leads to embryonic death with severe structural defects in the heart, including the ventricles and outflow tracts, along with widespread abnormal blood vessel development [114]. Additionally, FLNA-deficient mice display defects in neural crest cell migration, which further contributes to craniofacial abnormalities and congenital heart defects [3].

The zebrafish is a small teleost fish and a popular model organism for studying genetics and development because of its high genetic and physiological homology with mammals, rapid development, and transparent embryos, allowing real-time visualization of processes [120, 121]. FLNA knockdown in zebrafish results in hydrocephalus, brain swelling, curved body axis, and notochord abnormalities. Additionally, embryos show renal cysts, cardiac edema, and otic vesicle defects [122]. Zebrafish FLNA is involved in ciliogenesis, interacting with meckelin (mks3) on primary cilia, necessary for the proper formation and function of cilia, essential for various cellular processes (including the Wnt and other signaling pathways), and whose disruptions are linked to ciliopathies [123]. Thus, FLNA is an important element in maintaining the structural integrity of cells and the integration of various signaling pathways, key for cellular homeostasis and normal CNS development.

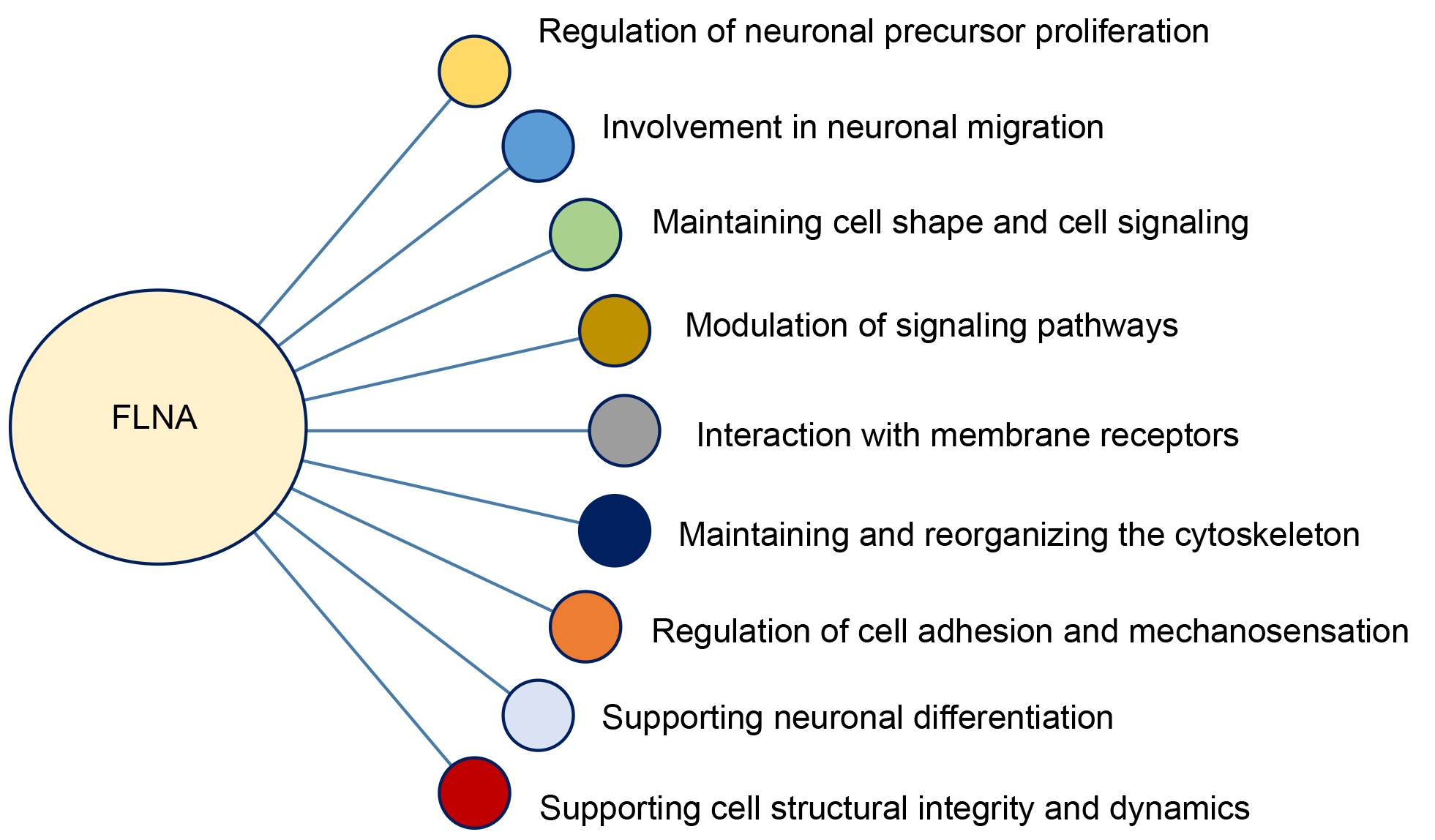

FLNA has emerged as an important regulator of CNS development and function, playing a key role in neuronal migration, neuronal network formation, and maintaining the structural and functional integrity of the brain [124, 125]. As summarized in Fig. 3, FLNA plays a significant role in cytoskeletal organization and signaling pathways regulating neuronal migration and plasticity [126, 127]. FLNA also interacts with Rho GTPase and

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Functional roles of filamin A (FLNA) in cellular dynamics and neurodevelopment.

In the context of neurodegeneration, FLNA contributes to pathological tau hyperphosphorylation and NFT formation [104]. This FLNA activity has been linked to neuroinflammation and toxic accumulation of amyloid proteins, making it a key player in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease [20, 134]. Its high expression in astrocytes and microglia (Fig. 2) indicates a role in the regulation of the reactive state of these cells during neuroinflammation. In pathologies such as progressive PSP, FLNA is detected in reactive astrocytes, highlighting its involvement in inflammation and tissue remodeling processes. Studying the role of FLNA in the brain emphasizes the potential of this protein as a putative diagnostic marker and therapeutic target, with drugs like simufilam exploring its potential to target altered forms of FLNA found in Alzheimer’s disease [135, 136]. The use of compounds that stabilize FLNA interactions with signaling proteins may potentially prevent defects in the cytoskeleton and improve neuronal migration. Such approaches may hold promise in the treatment of CNS diseases caused by FLNA mutations. Finally, modern gene editing techniques, such as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) technology, enable precise FLNA gene knockout, offering a platform to explore its role in various disorders and develop therapeutic approaches [81].

In summary, FLNA represents an important regulator of normal CNS processes and a critical element in the pathogenesis of various neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental conditions. Although multiple research questions related to FLNA neurobiology remain open (Table 3), future studies of the mechanism of FLNA action and its role in various cellular and molecular processes may foster the development of novel therapeutic strategies for FLNA-associated diseases. Further interdisciplinary efforts to explore the contributions of FLNA in CNS health and disease may lead to more ‘integrative’ approaches to diagnosing, monitoring, and treating a wide range of severely debilitating CNS disorders.

| Open questions |

| Stress and conformational changes. How do stress conditions (e.g., oxidative stress, inflammation) influence the structure and functions of FLNA, and how can these changes contribute to CNS disorders? |

| FLNA and neurodegenerative diseases. What post-translational modifications of FLNA regulate its role in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration? |

| FLNA and cellular signaling. How does FLNA interact with other cytoskeletal proteins and organelles, such as mitochondria, to influence cellular signaling and stress responses? |

| Epigenetics of FLNA. What epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation or histone modifications, regulate FLNA expression in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions? Do epigenomic (e.g., RNA methylation) processes contribute to FLNA-related CNS mechanisms? |

| Effects on the blood-brain barrier. What role does FLNA play (if any) in maintaining blood-brain barrier integrity, particularly during neuroinflammation or neurodegeneration? |

| Therapeutic opportunities. How can advanced genomic editing or small-molecule interventions target FLNA for therapeutic purposes in CNS diseases? |

All authors have extensively contributed to this manuscript. AVK conceived and coordinated the project, with conceptual input from NG, ADS and MSA. All authors have participated in data collection, analysis and interpretation. NG, ADS, DM, LY and MSA drafted the manuscript. NG, AVK and MSA participated in critical review and further revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical discussions and finalizing the manuscript before submission and have approved its final form. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The work was supported by FSMG-2021-0006 (Digital technologies for solving problems of quantitative medicine, Agreement 075-03-2024-117 of 17.01.2024) of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Russian Federation.

Given his role as the Editorial Board member, Allan V. Kalueff had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Bettina Platt.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.