1 Department of Clinical Pharmacy, The Third Hospital of Mianyang, Sichuan Mental Health Center, 621000 Mianyang, Sichuan, China

Abstract

Neuropsychiatric disorders make up 14% of the global disease burden and are the leading cause of disability from noncommunicable diseases worldwide. The primary treatment for these disorders is drug therapy. Nonetheless, these therapies do not work completely for most patients, and even with attempts to create novel drugs, no medication has been confirmed as safe and effective for treating neuropsychiatric disorders. Recent studies have emphasized the role of gene therapy in neuropsychiatric disorders. Unc-51-like kinase (ULK) has connections to central nervous system functions and disorders, but the role of ULK4 is less well understood than other members of that family.

The PubMed database was searched for articles regarding ULK4 in neuropsychiatric disorders and neurodevelopment with no restriction on publication date.

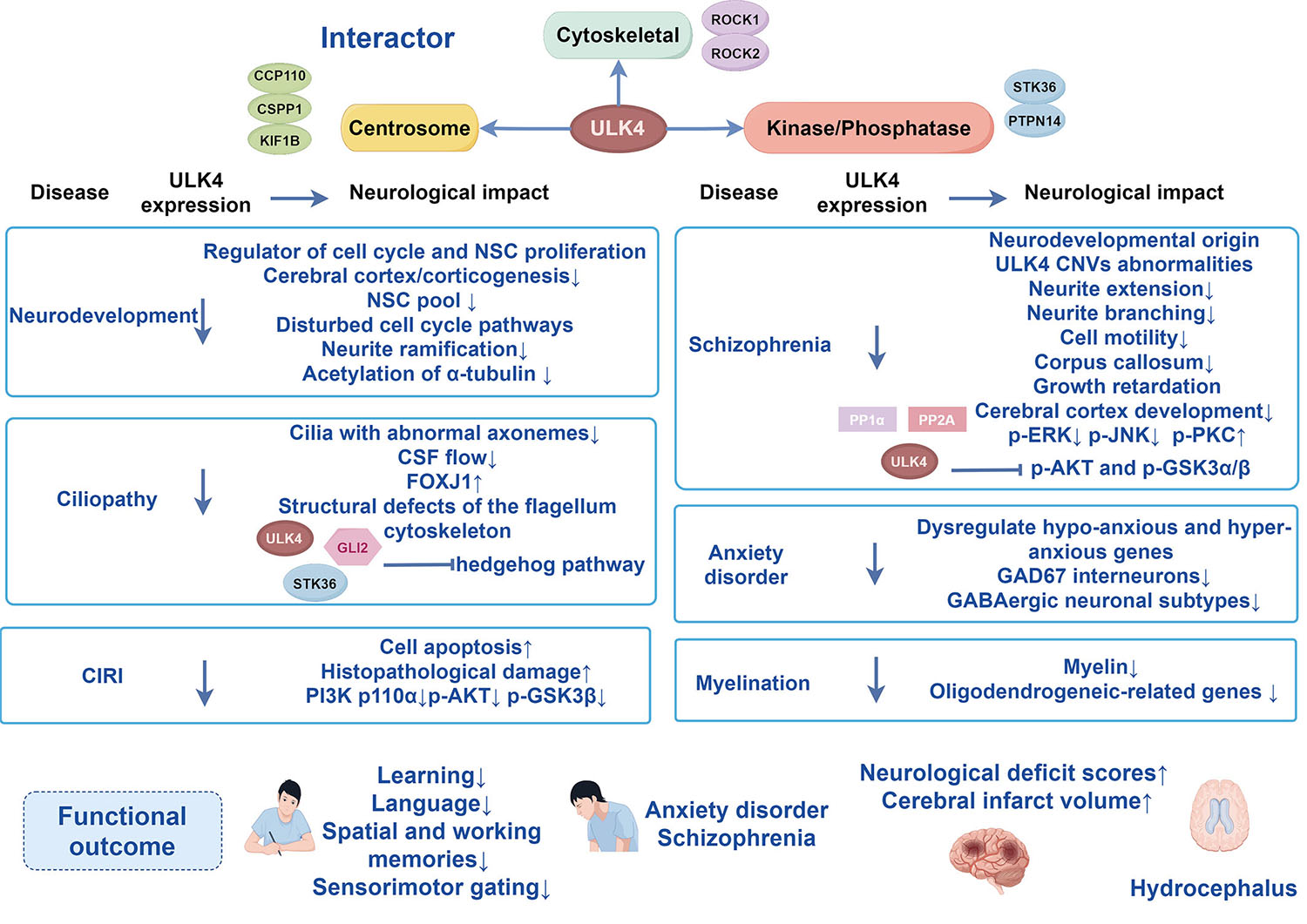

ULK4 is believed to function as a pseudokinase, potentially acting as a scaffold to connect kinases or other enzymes with their substrates or to manage the subcellular location of interacting proteins in different biological processes, abnormal low expression of which may increase the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders.

This review updates the latest evidence on the roles of ULK4 in brain development and neuronal function, and highlights some controversies and uncertainties in the current research on ULK4. This review offers perspectives on the continuous development and design of drugs targeting ULK4, supporting possibilities for their future clinical application.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- ULK4

- neuropsychiatric disorders

- neurodevelopment

- neuromodulation

- pseudokinase

Neurological and psychiatric disorders pose a significant public health challenge globally, affecting one in eight individuals with mental disorders or one in four individuals with neurological disorders at some stage in their lives [1, 2]. Neuropsychiatric conditions are complex illnesses with vague neurobiological roots, and they are all too common yet profoundly destructive [3, 4]. Despite years of research, progress in developing central nervous system (CNS) disease treatments has been slow, and small-molecule drugs continue to be the mainstay in clinical practice. An additional limitation of these therapies is that they do not cure the disease but only alleviate symptoms to slow its progression.

There is overwhelming evidence that neurological and psychiatric disorders have a developmental origin with a strong genetic underpinning [5]. Brain development disturbances may cause cerebral deformities and functional impairments, leading to developmental neuropathology [6]. The neuronal connectivity and cellular architecture of the brain are believed to be disturbed by these developmental insults. The rapid advancement of genome-engineering technologies has ushered in a new era for enhancing brain disease treatments through gene therapy [7, 8, 9]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS), databases such as the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, and ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequencing all connect Unc-51-like kinase (ULK) 4 to the CNS in processes like developmental/language delay and intellectual disability [10], mental disorders [11], ischemic stroke [12]. Outside the CNS, they have been found to be involved in hypertension [13, 14], mucociliary clearance impaired [15], sporadic thoracic aortic dissection [16], formation of bumps on the legs of pigs [17], cancer [18, 19], and age-related cataract [20].

Gene therapy provides unique advantages over traditional small-molecule therapies, such as the ability to control genes that encode proteins and achieve high target specificity [21, 22]. Significantly, there has been a consistent increase in research on gene therapy for CNS diseases in recent decades, as indicated by the swift growth in clinical trials and publications. Gene therapies are still in their infancy, and currently, there is no approved gene therapy for CNS diseases available in clinical settings. In this paper, we build on existing literature by examining the association of ULK4 with brain development and neuropsychiatric disorders, update the latest evidence with regard to ULK4, point out some controversies and uncertainty in the current research, and highlight its promising clinical application as a potential biomarker for the treatment of brain diseases [23].

We searched PubMed using the search terms “Unc-51 like kinase 4”, “unc-51-like kinase 4”, and “ULK4” with no time restrictions. Inclusion criteria included articles on ULK4 in neuropsychiatric disorders, neurodevelopment, and structure and characteristics, as well as articles on its involvement in the peripheral system (published 2020 and beyond), the rest were excluded. Table 1 (Ref. [10, 11, 12, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44]) summarizes the research on ULK4 in neuropsychiatric disorders and neurodevelopment.

| Disease | Model | ULK4 expression | Association of ULK4 with neurological condition | Ref. |

| Patients | Decreased | ULK4 CNVs abnormalities are associated with neuropsychiatric features and obesity | [10] | |

| Mental disorders | Patients | No change | Genetic variation in ULK4 may increase the vulnerability to mental disorders by modulating the extended reward system function | [11] |

| Ischemic stroke | Patients | No change | ULK4 as the shared risk SNPs between obesity and ischemic stroke | [12] |

| ULK4 structure and characteristics | [24] | |||

| ULK4 structure and characteristics | [25] | |||

| ULK4 structure and characteristics | [26] | |||

| Lrp2 mutant mice on FVB/N background | Increased | ULK4 as microtubule-associated proteins, is positive regulator of SHH signaling, and as components of primary cilia in the neuroepithelium | [27] | |

| NIH3T3 cells/HEK293T cells | No change | ULK4 acts in conjunction with STK36 to promote hedgehog pathway activation | [28] | |

| Schizophrenia | Patients/ULK4 knockdown SH-SY5Y cells/ULK4-/- mice | Decreased | ULK4 CNVs abnormalities are associated with schizophrenia | [29] |

| ULK4 deletion reduce neurite extension and impaired neurite branching, cell motility | ||||

| ULK4 deletion reduce p-ERK, p-JNK, increase p-PKC | ||||

| ULK4 deletion lead to defects of corpus callosum | ||||

| Neurodevelopment | Patients/ULK4tm1a/tm1a mice | Decreased | ULK4 deletion lead to severe language delay and learning difficulties | [30] |

| ULK4 deletion reduce cerebral cortex | ||||

| ULK4 as regulator of cell cycle and NSC proliferation | ||||

| Neurodevelopment | Disrupted ULK4 newborn mice | Decreased | ULK4 deletion reduce NSC pool | [31] |

| ULK4 deletion disturb cell cycle pathways | ||||

| Xenopus laevis | No change | ULK4 co-expressed with the neural stem/progenitor cell marker | [32] | |

| Neurodevelopment | ULK4 Knockdown mouse/Primary cultured mouse cortical neurons ULK4 knockdown | Decreased | ULK4 deletion decrease corticogenesis | [33] |

| ULK4 deletion decrease cell proliferation and deficits in radial migration and neurite ramification | ||||

| ULK4 deletion decrease acetylation of |

||||

| Myelination | ULK4tm1a/tm1a mice | Decreased | ULK4 deletion reduce myelin, which may help to explain severe learning difficulty and language delay | [34] |

| ULK4 deletion downregulate oligodendrogeneic-related genes | ||||

| Ciliopathy | ULK4tm/Lex mouse | Decreased | ULK4 deletion lead to congenital hydrocephalus | [35] |

| Ciliopathy | ULK4tm1a/tm1a mice | Decreased | ULK4 deletion reduced/disorganize cilia with abnormal axonemes | [36] |

| ULK4 deletion lead to hydrocephalus and functionally impairs the CSF circulation | ||||

| ULK4 deletion increase FOXJ1 ciliogenesis gene | ||||

| Ciliopathy | Primary cultured mouse ependymal cells ULK4 deletion | Decreased | ULK4 deletion lead to structural defects of the flagellum cytoskeleton | [37] |

| No change | ULK4 interacts with STK36 | |||

| Ciliopathy | Yeast/HEK293T cells/ULK4tm1a/tm1a mice | No change | ULK4 interacts with STK36 | [38] |

| Decreased | ULK4 deletion lead to dysfunctional CSF flow and defects of motile cilia | |||

| ULK4 deletion increase FOXJ1 ciliogenesis gene | ||||

| Ciliopathy | HEK293T cells/Depleted ULK4 by RNA interference in NIH3T3 cells | No change | ULK4 forms a complex with STK36 and GLI2 | [39] |

| Decreased | ULK4 deletion decrease the association between STK36 and GLI2 | |||

| ULK4 deletion decrease STK36 ciliary localization, GLI2 phosphorylation, and hedgehog pathway activation | ||||

| Schizophrenia | Patients | No change | ULK4 SNPs variants may be schizophrenia etiology | [40] |

| Schizophrenia | ULK4tm1a/tm1a mice/Nestin-Cre: ULK4f l/fl mice | Decreased | ULK4 deletion lead to growth retardation | [41] |

| ULK4 deletion reduce cerebral cortex development | ||||

| Cortical neuron migration is not affected in ULK4 deletion | ||||

| Schizophrenia | Emx1-Cre: ULK4flox/flox mice/SH-SY5Y cells transfected with pLex-Flag-ULK4 plasmid | Decreased | ULK4 deletion lead to deficits in the spatial and working memories and sensorimotor gating | [42] |

| ULK4 deletion reduce levels of p-AKT and p-GSK3 |

||||

| Increased | ULK4 overexpression lead to a significant enrichment of PP2A/PP1 |

|||

| Anxiety disorder | ULK4+/tm1a mice | Decreased | ULK4 deletion lead to anxiety-like behavior | [43] |

| ULK4 deletion dysregulate hypo-anxious and hyper-anxious genes | ||||

| ULK4 deletion reduce GAD67 interneurons in the hippocampus and basolateral amygdala | ||||

| ULK4 deletion reduce of GABAergic neuronal subtypes | ||||

| Cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury | MCAO/R rats/Primary cortical neurons subjected to OGD/R | Decreased | ULK4 overexpression reduce apoptosis, neurological deficit scores, cerebral infarct volume, and histopathological damage | [44] |

| ULK4 overexpression increase PI3K p110 |

CNV, copy number variation; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; SHH, sonic

hedgehog; Lrp2, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 2; STK36,

serine/threonine kinase 36; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; PKC,

protein kinase C; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; NSC, neural stem cell; CSF,

cerebrospinal fluid; FOXJ1, forkhead box j1; GLI2, GLI family zinc finger 2; AKT,

protein kinase B; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; PP2A, protein phosphatases

2A; PP1

The ULK family in mammals consists of four kinases, namely ULK1, ULK2, ULK3, and serine/threonine kinase 36 (STK36), along with one pseudokinase, ULK4. In ULKs, the kinase domains are situated at the N terminals, and the C-terminals contain protein interaction motifs crucial for substrate recruitment. Although ULK1 and ULK2 share only 29% sequence identity with ULK4 pseudokinase domain (PD), their structures superimposed well [45, 46]. All enzymes are considered crucial for development, especially for neurological development. Pseudokinases lack catalytically active kinase domains and primarily signal through their function as allosteric regulators or scaffolds [47]. Some pseudokinases serve as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) sensors, which respond to ATP binding without transferring phosphate [48, 49, 50].

ULK4 is a pseudokinase because it lacks the catalytic residues required for its kinase function. The connection of ULK4 to multiple human disorders underscores its developmental role as a kinase scaffold protein that lacks catalytic activity. The ULK4 gene’s single-nucleotide polymorphisms affect not only the CNS but also the peripheral immune system. Nevertheless, the mechanism by which ULK4 affects brain applications and mechanisms remains a mystery.

ULK4 has been discovered to have no apparent phosphotransfer activity, but it can bind ATP more effectively than other known pseudokinases [24, 25, 26]. Furthermore, a unique mechanism is discovered where ULK4 can bind ATP without the need for magnesium (Mg)2+, but it binds less potently when Mg2+ is present [24, 26].

ULK4 interacts with neighboring centrosomal proteins, such as centriolar coiled-coil protein 110 (CCP110), centrosome and spindle pole-associated protein 1 (CSPP1), and kinesin family member 1B (KIF1B) [26]. Microtubule-associated proteins, such as rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK) 1, ROCK2, and protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 14 (PTPN14), co-migrate with ULK4 [25, 26]. Additionally, the ULK family member STK36, like ULK4 [27], which plays a crucial role in regulating the hedgehog pathway [28, 51, 52], was found to be a high-confidence proximity interactor [25, 26]. However, how the pseudosubstrate binds to ULK4 pseudokinase, and whether ULK4 acts as an allosteric regulator of canonical kinases, are poorly understood.

Neurogenesis during embryonic and adult stages is essential for the formation and functioning of the brain. Disturbed neural proliferation is widely associated with brain disorders, such as schizophrenia and autism which are linked to ULK4 [10, 29]. There is genetic proof that ULK4 is deleted in 1.2 of 1000 patients who have clinical signs like developmental or language delays and intellectual disabilities [30].

The majority of mammalian cortical neurogenesis typically occurs in the embryonic stage, leaving a limited number of neural stem cells (NSCs) for adult neurogenesis [31]. These cells either divide slowly or remain inactive until they are needed for postnatal oligodendrogenesis [53, 54] and adult neurogenesis [55, 56, 57], and generate different layers of cortical neurons in a cell-cycle-dependent manner [58, 59, 60]. Thus, cell-cycle regulation is essential during cortical lamination. ULK4 is expressed alongside markers for cell proliferation and markers for neural stem/progenitor cell, showing the greatest abundance during the gap 2/mitosis (G2/M) phases [30, 32]. Consistent with ULK4 expression being specific to the cell cycle, Liu and colleagues noted that disruption of ULK4 resulted in a thinner cortex [31]. A notable co-localization of anti-ULK4 and Ki67 was detected in the neonatal subventricular zone (SVZ) region, but ULK4 expression is greatly diminished in nearby mature neuron areas [30]; this also reinforces the idea that ULK4 is needed not just for embryonic neurogenesis but also for the preservation of the NSC pool [31]. Whole-genome RNA sequencing identifies deregulation of gene expression in 19,652 in ULK4 mutants [30]. Analyses of pathways revealed a strong link between ULK4 targets and the proliferation of neural precursor cells as well as the cell cycle [31]. The absence of ULK4 in human neuroblastoma cells disturbed microtubule composition, leading to reduced neuritogenesis and cell motility [31]. Disassembled a-tubulin reduces acetylation, leading to decreased dendrite length, reduced branching, and impaired radial migration of cortical neurons [61, 62]. In the embryonic brain, silencing ULK4 led to a decrease in acetylated a-tubulin and affected both radial migration and proliferation of NSCs [33].

Although the specific molecular pathways have not been fully determined, ULK4 hypomorph mice exhibited the following phenotypes: predisposed mental disorders and neurodevelopmental diseases [23, 63, 64]; dysregulated inhibitory pathways [49]; and decreased white-matter integrity [34]. Moreover, ULK4 modulates the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and protein kinase C (PKC) signaling pathways, which are involved in managing the neuronal cytoskeleton often linked to schizophrenia neuropathology [29]. ULK4 is a key regulator of cell cycle and NSC proliferation involved in modulating wingless-int (Wnt) signaling pathways [30], and Wnt signaling is well-recognized for its role in neural development [65], and mental disorders [66].

Hydrocephalus is a serious neurological condition marked by an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain and enlargement of the brain’s ventricles [67, 68]. The complexity of hydrocephalus pathology is evident, with growing evidence indicating that a primary cause is the malfunction of motile cilia [69, 70, 71, 72, 73]. In a mouse knockout and phenotyping study, ULK4 was found among a group of genes that, when disrupted, led to hydrocephalus [35]. The ULK4 hypomorph mutant in mice leads to impaired ependymal cell differentiation and disrupted cilia function [36]. ULK4-deficient mice (ULK4tm1a/tm1a) exhibit progressive hydrocephalus and stunted growth, with the mutants not surviving beyond 3 weeks [35, 36]. RNA-sequencing analysis revealed that a number of genes associated with ciliogenesis were dysregulated in ULK4tm1a/tm1a, including the key cilia gene forkhead box j1 (FOXJ1) [36], underscoring the crucial role of ULK4 in motile cilia. In ULK4tm1a/tm1a mice, the dynein axonemal light chain 1 (DNAL1) and tubulin tyrosine ligase like 6 (TTLL6) are reduced by 10% and 49%, respectively, affecting outer and inner dynein arms [74, 75], though the molecular mechanisms remain mostly unclear.

ULK4 may homodimerize with the help of STK36 in mammals [37, 38, 39]. Continued investigation found that mutations in STK36 and ULK4 in mice resulted in hydrocephalus and other phenotypes related to ciliary defects and, as such, effectively phenocopied each other, producing growth retardation, early mortality, ventriculomegaly, underdeveloped or deficient ependymal cells, reduced or dysfunctional or disorganized cilia, disordered axoneme structure, and misaligned base body (BB) structure [37, 38]. The lack of STK36 also affects the expression of FOXJ1 and various other genes related to ciliogenesis [38]. Earlier studies indicated that mammalian STK36 is found in the motile cilium [76], and recent findings have shown that ULK4 is also present in the motile cilia of ependymal cells [37]. From these findings, we suggest that ULK4 and STK36 directly interact to jointly regulate ciliogenesis and ciliary function.

Myelin is crucial for high-speed and accurate electrical-impulse conduction in

axons, and also manages the synchronization of impulse transmission between

spatially separated cortical regions deemed critical for perception and cognitive

function [77]. Hypomyelination frequently occurs in neurodegenerative and

neurodevelopmental disorders. Children experiencing

developmental delays exhibited a notable decrease in myelinated tissue, with

19.8% brain volume compared to 21.4% in controls (p

Oligodendrocytes are responsible for producing myelin, making contact with multiple neighboring axons, and enveloping short axonal segments [81, 82]. Deficiency in ULK4 results in a notable downregulation of essential oligodendrogenic transcription factors, which are critical for the maintenance of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells and myelinating oligodendrocyte differentiation and maturation [34].

Neuropsychiatric disorders, which have complex pathogenesis, are leading causes of disability [83, 84]. Despite the efforts to elucidate their mechanisms or etiologies, they remain elusive and not yet clarified. Identification of specific gene-expression signatures has contributed to understanding the relationship between genes and brain health, and genetic risk for neuropsychiatric disorders [85]. Here, we discuss the potential effects of ULK4 on neuropsychiatric disorders, including anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, and cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury (CIRI).

Damage to synaptic connections is believed to affect neurodevelopment and brain function negatively, whether occurring alone or in combination, thereby increasing the predisposition to schizophrenia in adults [86]. ULK4 copy-number variations are found in several mental illnesses, including schizophrenia [29]. A test of association using two independent schizophrenia case-control cohorts of north Indian ethnicity reveals that ULK4 was found to alter the neurodevelopmental expression [40]. Further evidence has been found, in humans, that genetic variation in ULK4 increases vulnerability to mental disorders by modulating the extended reward system function [11]. The results offer compelling support for ULK4 as a novel rare risk factor for schizophrenia [29, 33, 41]. Genetic-linkage analyses have identified a strong co-segregation of protein kinase B (AKT) gene (AKT 1) haplotypes with schizophrenia [87]. Many downstream targets of AKT, including glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), may contribute to schizophrenia [42, 88].

According to recent findings, ULK4flox/flox conditional knockout

(CKO) mice demonstrate cognitive dysfunction and a decrease in the

phosphorylation of AKT and GSK3 [42]. As a pseudokinase, ULK4 generally executes

its biological roles by recruiting other active kinases for allosteric regulation

or by acting as scaffolds for substrate binding within signaling pathways [89].

The analysis of the proteome indicates that protein phosphatases (PP) 2A and

1

Despite showing impairments in spatial and working memory, and

sensorimotor gating, CKO mice do not exhibit anxiety-like behavior changes, which

contradicts the report that ULK4+/tm1a mice display an anxiety-like

behavioral phenotype [43]. The following factors might account for the varying

results: (a) ULK4 is deleted only in the excitatory neurons of the

cerebral cortex and hippocampus in CKO mice, but was only reduced by half in the

whole brains of ULK4+/tm1a mice; (b) impaired

Another question on the matter of debate is the radial migration of pyramidal neurons. The recent study on schizophrenia involving ULK4 found that the radial migration of pyramidal neurons is not apparent in ULK4 deletion [41], which was contrary to the findings of the previous study [33]. We hypothesized that the inconsistency might be due to the hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus may either have “add-on” effects or may “mask” the genuine migration delay through the resultant thinning of the individual sublayers.

Various studies have highlighted an imbalance between excitation and inhibition as a frequent mechanism in numerous neurodevelopmental disorders [90, 91, 92]. In line with the behavioral alterations, genes associated with hypo-anxiety, ATPase Na+/K+ Transporting Subunit Alpha 2 (ATP1A2), pleiotrophin (PTN), and midkine (MDK), were downregulated, whereas genes linked to hyper-anxiety, glutamate ionotropic receptor AMPA type subunit 1 (GRIA1), neuropeptide Y receptor Y2 (NPY2R), protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type A (PTPRA), were significantly upregulated in ULK4+/tm1a mice [43, 93]. Deleting ULK4 causes changes of GABAergic neurons, which may be a major factor reinforcing anxiety. In this case, not only were glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) 67 neurons of the amygdala and hippocampus reduced significantly, but there was also a subtype-specific reduction of GABA interneurons [43]. In addition, ULK4 deletion resulted in disruption of postsynaptic GABAergic signaling transmission, notably with significant upregulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit alpha (GABRA 1), GABRA3, GABRA4, GABRA5, and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit beta (GABRB) 3 [43]. However, it remains uncertain if ULK4deficiency has any effect on the formation or function of GABAergic neurons.

Evidence shows that schizophrenia is positively correlated with increased

mortality in ischemic stroke patients [94, 95]. Antipsychotic medication use has

been shown to reduce mortality rates in ischemic heart disease and stroke [96].

Mice experiencing experimentally induced CIRI demonstrated impairments in

learning and the development of new motor skills [97], and rats also displayed

anxiety-like behaviors after similar trauma [98]. The question of whether CIRI

influences the expression of the schizophrenia-susceptibility gene ULK4,

thereby contributing to the injuries and diseases mentioned, remains unanswered.

Whether ULK4 acts protectively or detrimentally in CIRI is uncertain.

Using an oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R) model in vitro

and a middle cerebral artery occlusion/reperfusion (MCAO/R) rat model in

vivo, we show a decline in ULK4 expression in the cortex of MCAO/R rats, and

primary cortical neurons in the OGD/R [44]. Overexpression of ULK4 inhibited

apoptosis and improved a series of indicators of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion

injury, including neurological deficit scores,

infarct volume, and histopathological damage

[44]. Through the application of network medicine analysis, our

investigation has established that ischemic stroke is prominently linked to the

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT-GSK3

Although studies suggest that ULK4 is associated with neurodegenerative disorders, direct evidence for this role is currently lacking, such as animal experiments or clinical evidence. ULK4 (also known as family with sequence similarity 7A, FAM7A) gene fuses with cholinergic receptor nicotinic Alpha 7 subunit (CHRNA7) gene to form the CHRNA7 (exons 5–10) and FAM7A (exons A–E) fusion (CHRFAM7A) gene [100]. Gene CHRFAM7A has been associated with Alzheimer’s disease risk in GWAS [101], which confirms the indirect relationship between ULK4 and Alzheimer’s disease. However, the direct evidence for the involvement of ULK4 in Multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and aging has not been retrieved. This may be an interesting direction for research, we will further connect ULK4 to neurodegenerative diseases and aging in future studies.

Deletion of ULK4 results in a thinner cortex, and a negative influence on neurite branching and neuronal motility. Brain-specific deletion of ULK4 leads to the malfunction of motile cilia, thereby resulting in congenital hydrocephalus. Severe language delay and learning difficulty are observed in the majority of ULK4-mutant children. ULK4, on the other hand, is closely associated with neuropsychiatric disorders. Susceptibility to schizophrenia is increased by ULK4 deletion. Deleting ULK4 causes changes in GABAergic neurons, which may be a major factor in reinforcing anxiety. Conversely, overexpression of ULK4 inhibits apoptosis, subsequently alleviating CIRI. The role of ULK4 in neurodevelopment and neuropsychiatric disorders is well established in overall association (Graphic abstract). Nevertheless, partial behavioral phenotypes and specific mechanisms are still controversial, such as anxiety-like behavior and radial migration of pyramidal neurons. This review summarizes the most recent research updates in the neuropsychiatric disorders and neurodevelopment concerning ULK4, and covers a larger coverage, such as CIRI, and interaction partners of ULK4, which further demonstrates the positive effects of ULK4 on neuropsychiatric disorders. In addition to this, this review highlights current inconsistencies in ULK4 research while explaining possible reasons for these discrepancies.

ULK4 is a gene that has not been extensively researched in association with neuropsychiatric disorders. Present findings somewhat elucidate the role and mechanism of ULK4 in brain function, holding promise for the development of new treatments for neuropsychiatric diseases. Given the nature of ULK4, further research should focus on identifying its role in conditions, including hemorrhagic stroke, depression, and comorbid neurological conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, Multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease. Although the results are promising, the therapeutic effectiveness of ULK4 manipulation for the aforementioned neuropsychiatric disorders relies on studies conducted on animals and cells. A future comprehensive study of the ULK4 mechanisms and functions in neuropsychiatric disorders will aid in converting pharmacological studies into clinical drug development, offering new clinical treatment alternatives.

ULK, unc-51-like kinase; CNS, central nervous system; TCGA, the cancer genome atlas; GEO, gene expression omnibus; STK36, serine/threonine kinase 36; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CCP110, centriolar coiled-coil protein 110; CSPP1, centrosome and spindle pole-associated protein 1; KIF1B, kinesin family member 1B; ROCK, rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase; PTPN14, protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 14; NSC, neural stem cell; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; FOXJ1, forkhead box j1; RNA, ribonucleic acid; DNAL1, dynein axonemal light chain 1; TTLL6, tubulin tyrosine ligase like 6; CNP, 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′ phosphodiesterase; ERBB3, erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3; GSN, gelsolin; MAL, mal, T cell differentiation protein; BCAS1, brain enriched myelin associated protein 1; AKT, protein kinase B; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; CKO, conditional knockout; GABA,

The data used in this study are included in the included articles and Table 1.

WL organized, designed, and wrote the manuscript. JW and JC performed the literature searches and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Supported by Health Commission of Sichuan Province Medical Science and Technology Program (24WSXT027).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.