1 Rehabilitation Department of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 350108 Fuzhou, Fujian, China

2 College of Rehabilitation Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 350122 Fuzhou, Fujian, China

3 Rehabilitation Medicine Department of Xiangyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Arts and Science, 441000 Xiangyang, Hubei, China

4 Xiangyang Key Laboratory of Rehabilitation Medicine and Rehabilitation Engineering Technology, 441000 Xiangyang, Hubei, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Spatial working memory (SWM) deficit is a common problem in attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity (ADHD), often correlating with the severity of ADHD symptoms and academic difficulties. Although previous studies have broadly described abnormal brain structural changes in ADHD, the potential changes in brain morphology in children with ADHD with SWM dysfunction are still uncharacterized. This cross-sectional study was used to elucidate the brain morphological alterations associated with SWM performance in boys with ADHD.

Data for this investigation were retrieved from one public dataset. A cohort of 23 boys diagnosed with ADHD and an age-matched group of 23 healthy male controls were selected for the study. Participants were administered n-back SWM tasks, with task accuracy and response times recorded. Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) was used to quantify gray matter (GM) volume, thereby characterizing the brain morphological features in both the ADHD and healthy control groups. Linear or rank correlation analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between GM volume and SWM task performance.

VBM analysis revealed significantly lower GM volume in the right middle cingulate cortex (MCC), left precuneus, and right retrosubicular region among boys with ADHD. Moreover, a significant positive correlation was observed between the GM volume of the right MCC and the accuracy of the 2-back SWM task under conditions of small reward and immediate feedback.

The reduced GM volume in the right MCC, left precuneus, and right retrosubicular might have a potential impact on SWM performance in children with ADHD.

Keywords

- ADHD

- attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity

- gray matter

- magnetic resonance imaging

- morphological characteristics

- spatial working memory

- voxel-based morphometry

Attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that typically emerges during childhood, affecting approximately 5.3% of school-age children globally. It is characterized by persistent patterns of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity [1, 2]. Working-memory impairment is a common problem in children with ADHD, and has been confirmed by many studies [3, 4, 5]. Spatial working memory (SWM) is a working-memory model that concerns the encoding, storage, and manipulation of spatial information over brief intervals [6]. Children with ADHD have greater deficits in visual-spatial information than deficits in auditory-verbal information, which significantly affects SWM processing [7]. Previous studies suggested that SWM deficits were positively correlated with the severity of ADHD symptoms, and mainly manifested by more inattentive symptoms, greater motor activity, lower intelligence, and higher medication use [8, 9, 10]. The presence of SWM deficits in children with ADHD may lead to academic difficulties and mental-developmental disorders, and subsequently affect their long-term quality of life [11, 12]. Therefore, understanding the underlying mechanisms of SWM deficits is crucial for early diagnosis and intervention in children with ADHD.

SWM is closely related to the attention system, and is modulated by multiple brain regions including the inferior and superior parietal regions and the lateral prefrontal regions [13, 14, 15]. The right occipital parietal region, right cingulate cortex, and medial temporal lobe play an important role in memory encoding, maintenance, and retrieval in SWM processing [16]. Research has identified the right middle frontal gyrus as a vital region for storing memory and maintaining spatial representations of SWM [17]. Additionally, one study found that, during the encoding and active maintenance in SWM task, the voxel activity patterns of the parahippocampal cortex and posterior hippocampus, which are part of the temporal lobe, could carry memory information regarding the configuration of spatial locations [18]. In SWM tasks, accurate localization of stimuli relies not only on memory for individual stimuli, but also involves the assessment of the relative distance of the stimulus to surrounding fixed landmarks. This process is closely related to egocentric and allocentric spatial processing [19]. The superior parietal lobe is essential for processing contextual cues that facilitate the perception of egocentric space [20]. Furthermore, the parietal cortex plays a crucial role in allocentric spatial processing, providing functional support for the switch between egocentric and allocentric frames of reference, allowing individuals to switch flexibly between different spatial frames of reference [21]. Based on the above studies, in the present study we speculated that children with ADHD with SWM deficits have brain structural and functional alterations.

Children with ADHD with worse working-memory performance in spatial positions exhibited lower volume and apparently lower fiber density of the left superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF)-II, revealing a correlation between left SLF-II and working memory performance [22]. Another neuroanatomical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) analysis focusing on ADHD individuals identified a potential connection between SWM deficits and specific brain structures including the thalamus, hippocampus, right putamen, insula, and prefrontal and temporal cortical regions [23], but the exact alterations in these brain structures were not clear. A previous functional MRI study had shown that, compared to healthy control (HC), ADHD individuals with SWM deficits had significantly lower activation in the right parieto-occipital regions (cuneus and precuneus), right inferior parietal lobe, and right caudate nucleus [24]. As the load of SWM tasks increased, there was a corresponding rise in activation within the left inferior frontal gyrus and the lateral frontal pole in the ADHD group [25]. Additionally, functional-connectivity analyses have revealed that although the connectivity between the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the left intraparietal sulcus were greater, the connections between the left DLPFC and the left middle cingulate cortex (MCC) and the posterior cingulate cortex were lower in children with ADHD [26]. It is noteworthy that most studies have investigated the functional connectivity of SWM deficits in ADHD [24, 25, 26, 27], but there is limited research on structural changes of the potential SWM deficits in ADHD. Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) is a commonly used automated method for analyzing brain structural images, and it can reflect anatomical differences by quantitatively assessing the density or volume variations in gray matter (GM) or white matter (WM) [28, 29]. Previous VBM research has identified multiple regions within the temporal lobe, cerebellum, and frontal lobe that are linked to working-memory performance in individuals with ADHD [30]. Another VBM study revealed that the reduction of GM volume in the right cerebellum lobule VI might influence verbal working memory performance in children with ADHD [31]. Based on the previous studies, using VBM is a valid method to investigate the potential changes of brain morphology associated with decreased SWM performance in children with ADHD.

The present study was designed to investigate the changes in neural morphological characteristics in boys with ADHD using VBM and analyze the correlation between brain morphological characteristics and SWM performance, which might assist to enhance further understanding of the underlying neurological mechanisms of decreased SWM performance in ADHD.

The present study used a cross-sectional method. The data for this study were retrieved from a public database (https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds002424). All participant informed-consent forms were collected and rights were protected [32]. The study included 23 ADHD boys and 23 healthy control (HC) boys. All participants were native English speakers who were right-handed and born at full term. They had no hearing loss or MRI contraindications. In addition, none of the participants had a history of mental or neurological disorders. All participants were free from medications that influence central nervous system function, with the exception of those specifically prescribed for ADHD and its associated comorbidities. Notably, boys receiving stimulant medication for ADHD were instructed to refrain from taking the medication for the 24-h period preceding the study session. The original dataset indicated that all the boys had undergone supplemental screening for difficulties or disorders like disruptive behavior, oppositional defiant disorder, and school-environment learning preferences. The questionnaires used included the ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Home Version, and the Short Survey for Behavioral Avoidance System and Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS-BAS). The present study design, ethical approval, participant recruitment, and clinical trials are detailed on OpenNeuro.org.

A detailed description of the SWM n-back task paradigm appeared in a previous article [32]. The spatial version of the n-back task enables a more direct assessment of the neural mechanisms associated with visuospatial working memory, one of the core deficits in children with ADHD. In addition, the task can be combined with neuroimaging techniques (e.g., VBM) to reveal associations between working memory performance and brain structure. In the present study, each participant completed 48 trials of 1-back SWM tasks, 48 trials of 2-back SWM tasks, and 24 trials of fixation tasks. Two independent factors were manipulated in the SWM tasks: reward magnitude (large vs small) and feedback timing (immediate vs delayed). The task was designed to examine the effects of different reward levels and feedback times on spatial working memory performance for each of four conditions. The sequence of experimental tasks was randomly generated, with each experimental comprising 12 blocks, consecutively. Prior to the test, participants were presented with task instructions (1-back or 2-back) and requirements. The participants were required to sit in front of a screen; there was a gaze square in the center of the screen. During each trial, a stimulus (English letter) appeared for a duration of 1200 msec at one of the four corners around the gaze square, followed by an 800-msec interval with no stimulus. In the n-back task, participants were instructed to respond by pressing different buttons when the presented stimulus was in the same position as the one presented in trial 1 (1 trial for 1-back task, and 2 trials for 2-back task) previously. E-Prime 2.0 (Psychology Software Tool, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) was used for stimulus presentation and response recording.

VBM was performed using Computational Anatomy Toolbox 12 (CAT12) (https://neuro-jena.github.io/cat/, Structural Brain Mapping Group, Jena, Germany).

First, T1-weighted images were segmented into GM, WM, and cerebrospinal fluid,

and the total intracranial volume was calculated. Subsequently, the segmented GM

images were spatially normalized to the standard Montreal Neurological Institute

space-based 1.5-mm template of the CAT12 toolbox for 11-year-olds [33]. The

resulting image’s uniformity was checked. Finally, a 4-mm full-width Gaussian

smoothing kernel was applied in order to smooth the normalized GM image. A

t-test was used to compare voxel-wise differences in GM volume between

the ADHD and HC groups. Brain-wide thresholds of voxel-level p

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM SPSS statistics,

Chicago, IL, USA). Normality of continuous variables was assessed using

Shapiro-Wilk test as an initial step in data analysis. For data with normal

distribution, mean values along with their corresponding standard deviations were

used for statistical description purposes, independent t-tests were used

for group-level comparisons. For data with non-normal distribution, median values

along with quartiles served as descriptive statistics, Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U

test was used for intergroup comparisons. Bivariate adoption rate was

statistically described and compared using the Chi-square test. To evaluate the

association between GM volume and SWM task performance, the study also conducted

linear or rank correlation analyses. The significance level of all statistical

tests was set at p

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics and performance metrics (response time and accuracy) in SWM n-back task for all participants. Statistical analyses revealed that there were no significant differences in age (p = 0.191), sex (p = 1.000), or handedness (p = 1.000) between groups. However, the ADHD group exhibited lower accuracy than did the HC group across various task conditions. Specifically, in the 1-back SWM tasks, accuracy was significantly lower in Condition 1 (p = 0.036), Condition 2 (p = 0.017), and Condition 4 (p = 0.027). Similarly, in the 2-back SWM tasks, accuracy was significantly lower in Condition 1 (p = 0.003), Condition 2 (p = 0.043), Condition 3 (p = 0.004), and Condition 4 (p = 0.003).

| Variables | ADHD | HC | p value | ||

| (n = 23) | (n = 23) | ||||

| Age (years) [mean (SD)] | 10.30 (0.85) | 10.65 (0.93) | 0.191 | ||

| Sex, boy (%) 1 | 23.00 (100.00) | 23.00 (100.00) | 1.000 | ||

| Handedness, right (%) 1 | 23.00 (100.00) | 23.00 (100.00) | 1.000 | ||

| ADHD medication (%) | 19 (82.61) | - | - | ||

| Accuracy (%) | |||||

| 1-back | |||||

| Large reward, delayed feedback 2 (Condition 1) | 87.23 (72.34–93.62) | 91.49 (82.98–100) | 0.036 | ||

| Large reward, immediate feedback 2 (Condition 2) | 87.23 (76.6–95.74) | 93.62 (89.36–100) | 0.017 | ||

| Small reward, delayed feedback 2 (Condition 3) | 87.23 (72.34–91.49) | 93.62 (80.85–95.74) | 0.080 | ||

| Small reward, immediate feedback 2 (Condition 4) | 87.23 (80.85–91.49) | 91.49 (85.11–100) | 0.027 | ||

| 2-back | |||||

| Large reward, delayed feedback (Condition 1) | 66.26 (14.89) | 81.1 (16.63) | 0.003 | ||

| Large reward, immediate feedback (Condition 2) | 72.21 (14.45) | 81.29 (15.09) | 0.043 | ||

| Small reward, delayed feedback (Condition 3) | 67.2 (17.72) | 80.81 (13.44) | 0.004 | ||

| Small reward, immediate feedback (Condition 4) | 66.35 (13.87) | 79.30 (14.51) | 0.003 | ||

| Response Time (s) | |||||

| 1-back | |||||

| Large reward, delayed feedback (Condition 1) | 0.61 (0.15) | 0.58 (0.11) | 0.513 | ||

| Large reward, immediate feedback (Condition 2) | 0.61 (0.14) | 0.60 (0.09) | 0.760 | ||

| Small reward, delayed feedback (Condition 3) | 0.61 (0.12) | 0.61 (0.10) | 0.911 | ||

| Small reward, immediate feedback (Condition 4) | 0.62 (0.11) | 0.60 (0.08) | 0.712 | ||

| 2-back | |||||

| Large reward, delayed feedback (Condition 1) | 0.62 (0.17) | 0.63 (0.12) | 0.806 | ||

| Large reward, immediate feedback (Condition 2) | 0.63 (0.15) | 0.61 (0.14) | 0.669 | ||

| Small reward, delayed feedback (Condition 3) | 0.63 (0.13) | 0.63 (0.16) | 0.837 | ||

| Small reward, immediate feedback (Condition 4) | 0.63 (0.15) | 0.64 (0.12) | 0.820 | ||

Note: Values are presented as mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range) or proportion; Bold font indicates that the results are significant in that condition; ADHD, Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; HC, healthy control; SWM, spatial working memory; 1 p determined using chi-square test; 2 p determined using Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test.

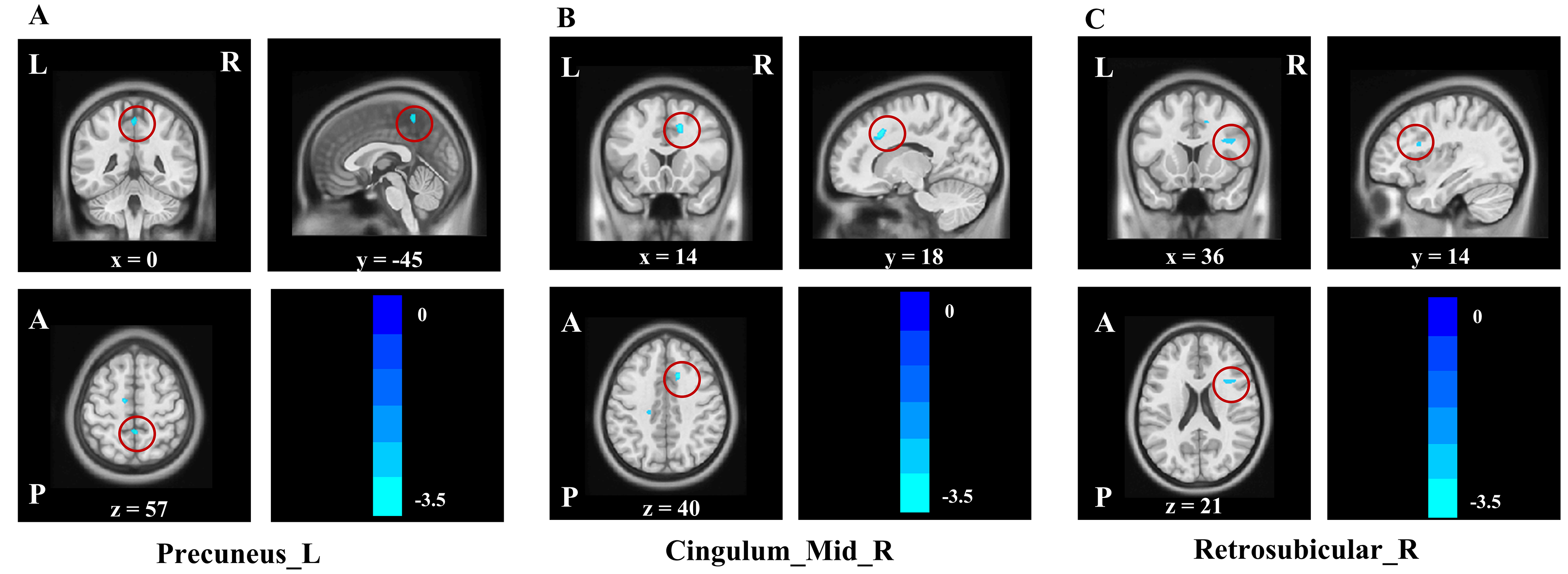

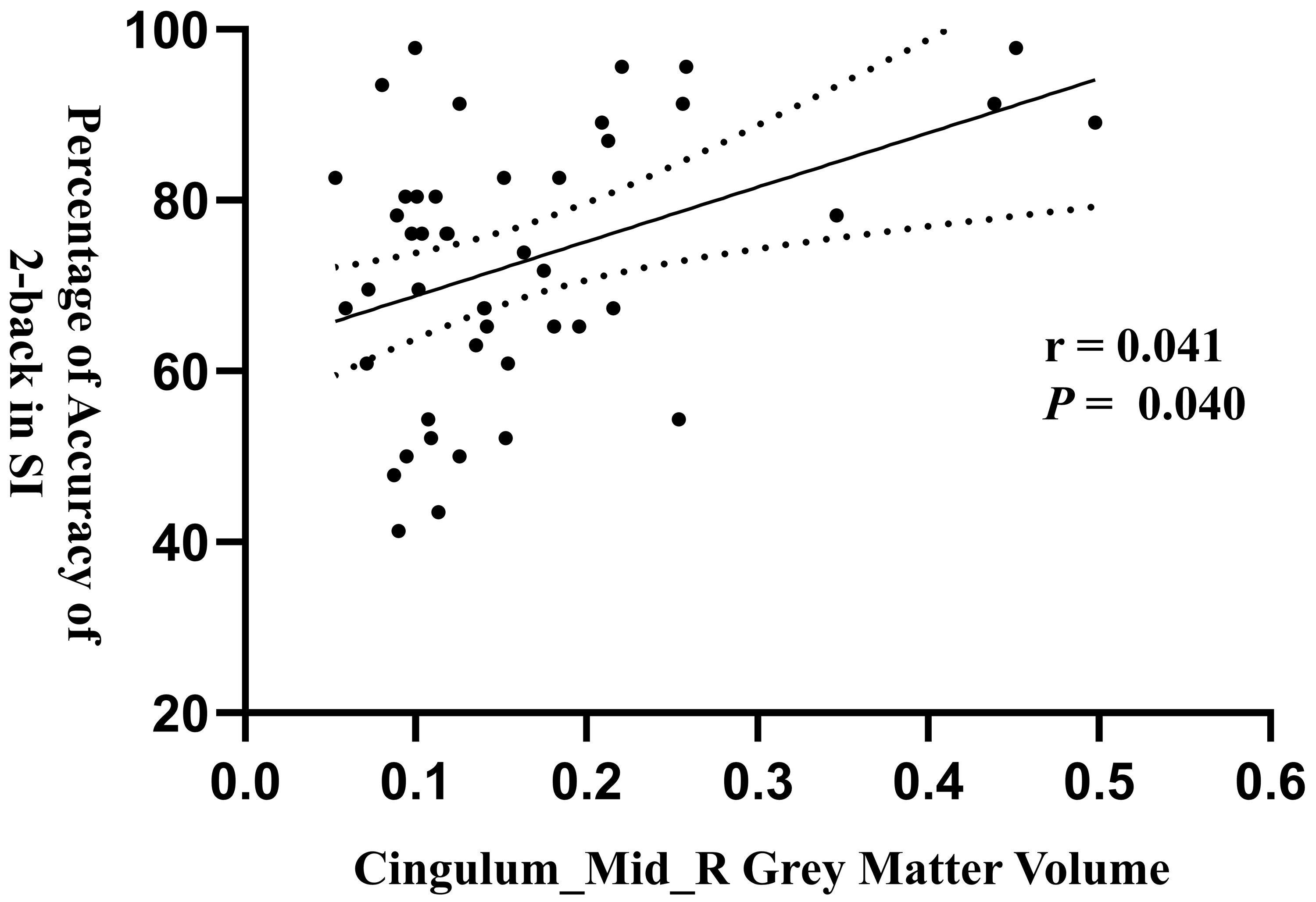

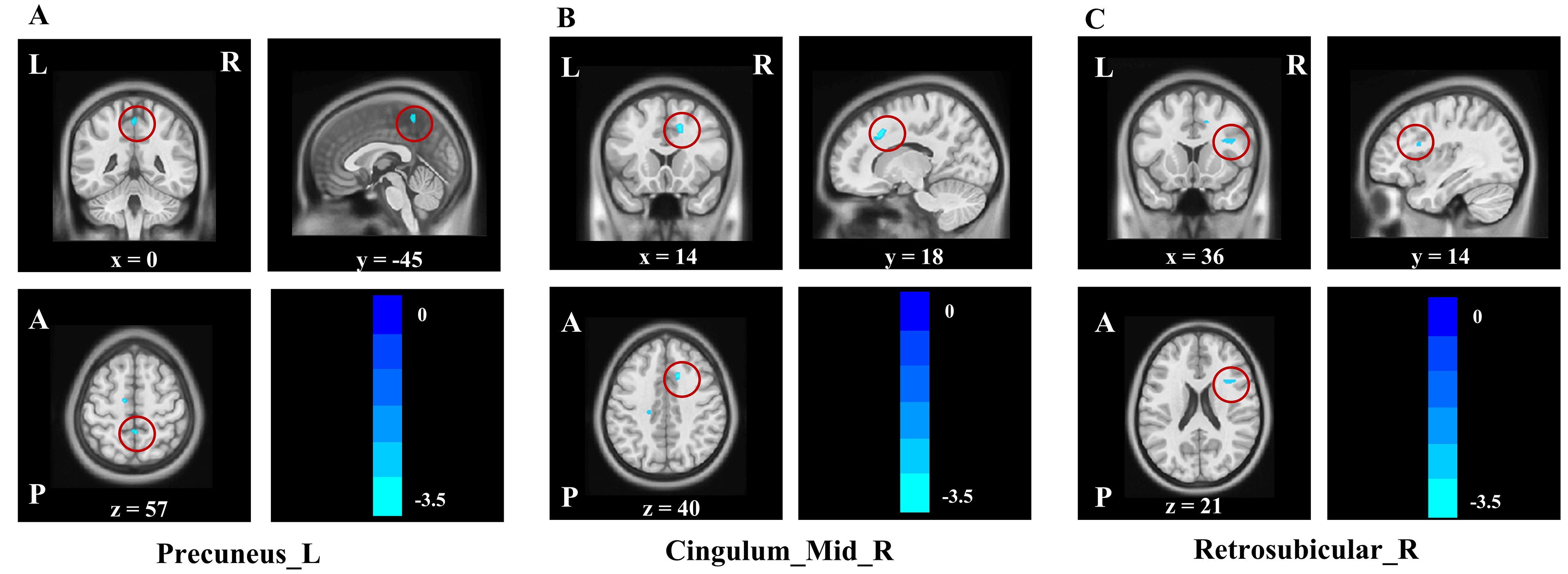

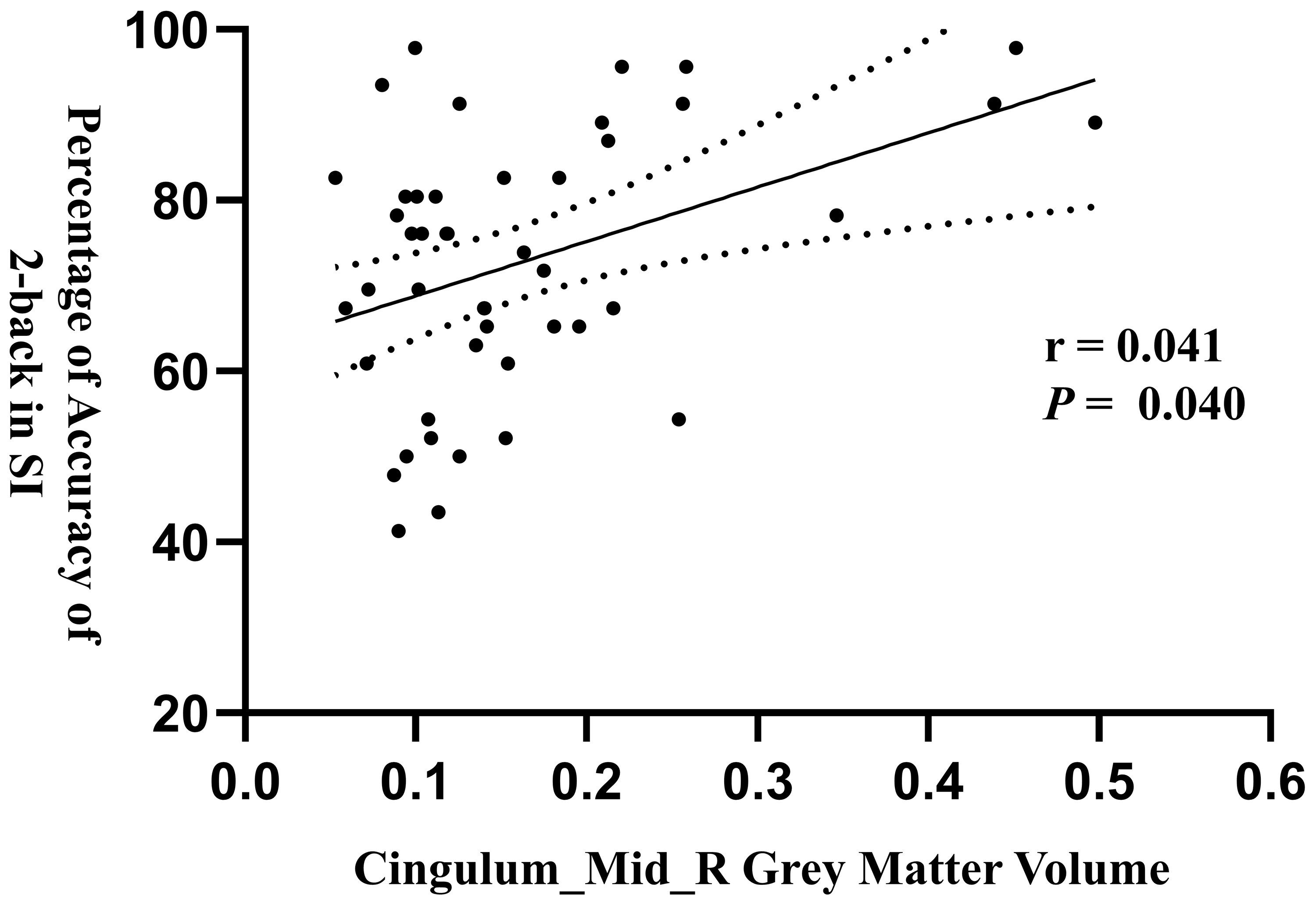

Table 2 shows the significant differences in GM volume in specific brain regions between the HC group and the ADHD group. Relative to the HC, boys with ADHD exhibited significantly smaller GM volume in the right MCC (Table 2 and Fig. 1A), the left precuneus (Table 2 and Fig. 1B), and the right retrosubicular (Table 2 and Fig. 1C). In addition, a significant positive correlation was observed between the GM volume of the right MCC and the accuracy in 2-back SWM task under Condition 4 (Fig. 2 and Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the GM Volume in the ADHD group and the HC group. The GM volumes of (A) the left precuneus, (B) the right middle cingulate cortex, and (C) the right retrosubicular were smaller in the ADHD group than in the HC group. The red-highlighted regions in the figure demonstrate GM volume alterations in ADHD group across three anatomical planes: sagittal, coronal, and horizontal plane. L, left; R, right; GM, gray matter.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Associations between the GM Volume of the right middle cingulate cortex and the accuracy of 2-back in SI. Each point represents the sample, and the linear arrangement of the samples showed a significant positive correlation between the GM volume of the right middle cingulate cortex and the accuracy of 2-back in SI in the ADHD group; SI, Small reward, immediate feedback.

| Contrast | Cluster | Brain Region | t-value | MNI Coordinates | ||

| x | y | z | ||||

| ADHD |

482 | Cingulate_Mid_R | 3.37 | 14 | 18 | 40 |

| 240 | Precuneus_L | 3.61 | 0 | –45 | 57 | |

| 202 | Retrosubicular_R | 3.06 | 36 | 14 | 21 | |

Note: A threshold of peak-level p

| Accuracy | Precuneus_L | Cingulum_Mid_R | Retrosubicular_R | |||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| LD_1back | 0.247 | 0.163 | 0.271 | 0.115 | 0.267 | 0.143 |

| LD_2back | 0.260 | 0.163 | 0.349 | 0.051 | 0.276 | 0.143 |

| LI_1back | 0.117 | 0.445 | 0.172 | 0.294 | 0.126 | 0.410 |

| LI_2back | 0.262 | 0.163 | 0.349 | 0.051 | 0.286 | 0.143 |

| SD_1back | 0.138 | 0.417 | 0.139 | 0.363 | 0.174 | 0.290 |

| SD_2back | 0.193 | 0.273 | 0.289 | 0.108 | 0.245 | 0.143 |

| SI_1back | 0.253 | 0.163 | 0.209 | 0.225 | 0.244 | 0.143 |

| SI_2back | 0.341 | 0.163 | 0.410 | 0.040 | 0.306 | 0.143 |

Note: Bold font indicates that the results are significant in that condition; LD, Large reward, delayed feedback; LI, Large reward, immediate feedback; SD, Small reward, delayed feedback.

The present study investigated the differences in brain morphology associated with SWM performance in boys with ADHD. We found that boys with ADHD with lower SWM performance showed reduced GM volume of the left precuneus, the right retrosubicular, and the right MCC. Notably, Boys with ADHD demonstrated lower accuracy in 1-back and 2-back SWM tasks than did HC boys. In addition, there was a significant positive association between the GM volume of the right MCC and the accuracy of the 2-back SWM task under Condition 4 (Small reward, Immediate feedback).

According to the results, a lower GM volume in the left precuneus and the right retrosubicular was observed in boys with ADHD. Judgements of object position and orientation in the SWM rely on allocentric and egocentric spatial processing, with egocentric spatial processing mediated primarily by the precuneus. Allocentric spatial processing mobilizes the right parietal cortex, the ventral visual stream and the hippocampus [34]. Results of an fMRI study demonstrated that the right parietal cortex exhibited greater activity during SWM tasks that involved orientation [35]. Another study showed that during rewarded SWM, the blood-oxygen-level-dependent signals in the visual association areas of the posterior prefrontal and parietal cortices exhibited increases [36]. The precuneus, which is a small part of the medial parietal lobe, is essential for spatial object-shape perception and spatial orientation, playing a crucial role in higher cognitive functions like episodic memory [37]. One study suggested that the capacity of SWM was significantly positively correlated with the functional connectivity between the left precuneus and the left DLPFC [17]. The lower GM volume in the left precuneus might be associated with changes in functional connectivity, which in turn would affect SWM capacity. In addition, one study showed that ADHD individuals with lower SWM performance exhibited remarkably lower activation in the precuneus [38], which might be caused by lower GM volume in the precuneus. The right retrosubicular is part of the hippocampus, and it is known that the hippocampus is critical in some cognitive processes including working memory, spatial navigation, and situational memory [39, 40]. Additionally, research has shown that the preservation of spatial information in SWM relied on the structural network of the hippocampus [41]. SWM involves the capacity for transient caching of spatial cues in order to facilitate decision-making, and it exhibits a close association with the structural characteristics of the hippocampus, which assumes a pivotal role in encoding cues during SWM tasks [41, 42, 43]. Therefore, the lower GM volume in the right retrosubicular might affect the encoding of SWM processing. In general, the present study conjectured that lower GM volume in the left precuneus, and the right retrosubicular in boys with ADHD affects spatial perception in SWM performance, including encoding and preservation of spatial information.

In addition, in the present study, the ADHD boys exhibited lower GM volume in the right MCC than did the HC boys. Research has shown that the MCC participates in advanced and complex executive-function processing, such as attention switching, reward-based decision-making, error detection, working memory, and action control [44]. Specifically, the MCC integrates information from different tasks to construct a fully characterized task space, making reward-related decisions and implementing corresponding actions [45, 46]. Study results have shown that MCC activities might relate to information update and internal environmental models involved in the decision-making process [47]. Previous study also has found less cortical thickness and GM volume in the left MCC of children with ADHD [45], which is consistent with the finding of the present study. Other studies have suggested that the cingulate gyrus exhibits greater activation during the encoding process of SWM [48], and the structural abnormalities of the MCC disrupted part of its function and influenced the formation of the connection between actions and outcomes [49]. Thus, the lower GM volume of middle cingulate in children with ADHD might lead to several issues including dysfunctions in reward-based decision-making, working memory, and attention switching.

Our results also showed that the boys with ADHD had significantly lower accuracy in the 1-back SWM task in Condition 1, Condition 2, Condition 4, and all 2-back SWM tasks. The amount of reward (categorized as large vs small) and feedback (categorized as immediate vs delayed) were two independent factors that influenced the accuracy of SWM tasks. Children with ADHD typically exhibit characteristics of low motivation and increased reward sensitivity [8, 50]. The moderating effect of rewards on working-memory performance in children with ADHD can be examined by setting different reward levels. For example, children with ADHD have been found to show greater task engagement and better working-memory performance under reward conditions [51, 52]. By setting different reward conditions, it is possible to explore the neural basis of the brain associated with rewards in the SWM task in children with ADHD. In addition, immediate feedback can help participants adjust their strategies quickly, whereas delayed feedback tasks can be used to examine participants’ memory retention over a longer period of time [26]. One study demonstrated that, in a feedback-based probabilistic learning paradigm, no significant differences in academic performance were observed between ADHD and non-ADHD groups under delayed-feedback conditions, whereas the ADHD group exhibited lower academic performance in the immediate-feedback condition than did the control group [53]. Given the intricate relationship between ADHD learning capacity and feedback timing—learning ability, in turn, is closely intertwined with executive functions such as SWM—our study leveraged distinct feedback conditions to delve deeply into the divergent brain mechanisms by which boys with ADHD process feedback within the context of SWM tasks. In the present study, the findings suggested that the lower GM volume of MCC in children with ADHD might lead to deficits in reward-based decision making, which might affect the accuracy of n-back SWM tasks. Furthermore, the study has shown that task-performance characteristics during the immediate-reward selections were positively correlated with MCC activity [54]. MCC neurons apparently can encode signals of fictional or hypothetical rewards, as well as signals of accepting or rejecting rewards [55, 56]. The corticobasal ganglia circuit serves as the control center for the reward system, and the key structures within this circuit including the cingulate cortex and the hippocampus, which assists in regulating the reward circuit [57]. Several studies have documented that the dorsal anterior middle cingulate cortex (daMCC) is relevant to motivation and reward, target detection, response selection, and response inhibition, thereby playing an important role in feedback-based decision-making. Abnormalities in daMCC were also observed in children with ADHD [58, 59, 60]. Moreover, the 2-back task requires a greater SWM load than does the 1-back task. One study suggested that as the demand for working memory increases, higher central executive functions and more memory stock are needed to support task implementation [27]. Previous evidence suggested that children with ADHD exhibited abnormal functional activity patterns in the left MCC under 2-back SWM loading condition [26]. The present study further revealed a significant positive correlation between the GM volume of right MCC and the accuracy of the 2-back SWM task under Condition 4. Based on the above results, we speculated that the MCC is greatly involved in tasks requiring large SWM capacity, and the structural changes in the right MCC might influence overall SWM performance in boys with ADHD.

There are some limitations of the present study. First, the limited sample size might influence the generalizability and practical application of the findings, and it is necessary to conduct large-sample studies in the future. Second, this study only included boys, which might result in overlooked sex differences. Future research should include both sexes. Third, the study mainly explored the brain morphological characteristics within a fixed period of time, and real-time dynamic tracking might be needed for comprehensive analyses. Future studies could investigate immediate and dynamic brain-signature changes in children with ADHD on SWM tasks. Fourth, the study used letters as stimuli in the SWM task, which had the effect of increasing the language component. Future research could consider using non-verbal visual stimuli, such as shapes or patterns, to optimize the evaluation of SWM performance. Fifth, the study did not screen participants for visual function. Spatial working-memory tasks rely on visual information processing, and undetected visual dysfunction may confound task performance measures and affect the interpretation of findings. Future studies should incorporate standardized visual acuity assessments during participant selection.

The present study found lower levels of GM volume in the right MCC, the left precuneus, and the right retrosubicular in boys with ADHD, and also identified the positive association between the GM volume in the right MCC and the accuracy of performance in 2-back SWM task. In conclusion, these results may shed light on potential features of brain structural changes in children with ADHD and provide further evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of children with ADHD with decreased SWM performance.

The finding of lower GM volume in specific brain regions provides new neuroimaging evidence for diagnosing children with ADHD, and changes in these brain regions may serve as potential biomarkers to help clinicians distinguish ADHD from other neurodevelopmental disorders with similar symptoms. Moreover, the correlation between the structural aberration and performance on the SWM task may also provide a potential indicator for assessing potential cognitive deficits in children with ADHD.

The results of this study suggest that interventions targeting these specific brain regions (e.g., cognitive training, neurofeedback training, or transcranial magnetic stimulation) may improve SWM performance in children with ADHD. In addition, the study highlights the need to consider individual differences in reward and feedback conditions when designing interventions, e.g., providing small immediate rewards may be more beneficial in enhancing SWM performance in children with ADHD.

The data was obtained from the open access dataset hosted on the OpenNeuro.org (https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds002424), which is a free and open platform for researchers.

LFC designed the study and wrote the original draft of manuscript. YSL and QHW analyzed the data, and wrote the original draft of manuscript. CZ, SQZ and RL were responsible for writing and revising the manuscript, and interpretation of data. YZ, QQS and LLL were responsible for the study design, manuscript writing, review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The authors are sincerely thankful to James R. Booth, Marisa N. Lytlea, Rubi Hammer and other researchers for their effort in data collection, data curation and data sharing on the OpenNeuro.org.

This research was funded by the School Management Project of Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (X2024003, X2024004).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.