1 Goethe University Frankfurt, University Hospital, Institute of Neuroradiology, D-60528 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Abstract

Schizophrenia is characterized by the presence and persistence of psychiatric symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, thought disorders, or disorganized behavior for at least 1 month. An internal medical examination and the exclusion of other causes for the symptoms are an integral part of the diagnostic procedure. However, despite constant improvements in technology and resolution, radiological imaging of structural changes of the brain is not part of the standard clinical care of schizophrenia patients, except to rule out tumors or other causes for the symptoms. There are many scientific approaches to determine morphological criteria and biomarkers of schizophrenia, which could potentially play a role in diagnosis and follow-up in the future; a summarized assessment of the current state of knowledge regarding structural changes in schizophrenia is therefore necessary. The present review demonstrates that the four disciplines of neuroradiology, genetics, neuropathology, and ophthalmology have made important contributions to the question of structural changes in schizophrenia; the individual contributions are presented and discussed below. The best characterized changes are enlargement of the lateral ventricles, volume reduction of the grey matter with thinning of the cortex, enlargement of the pallidum, diffusion disturbances in the white matter, as well as ophthalmological evidence of thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer. Equally important are the numerous additional findings whose potential significance for diagnosis and follow-up are emphasized in this review. Particularly noteworthy are significant correlations of individual structural changes with the presence of hallucinations, or even the comparison of patients with high and low cognitive performance scores, as well as correlations between morphological and genetic changes. In summary, our review demonstrates the realistic prospect of a future expanded morphological assessment of the central nervous system in the context of clinical examination. To achieve this goal, there is a need for continued interdisciplinary research into potential morphological biomarkers of schizophrenia.

Keywords

- schizophrenia

- magnetic resonance imaging

- neuropathology

- anomalies

- neurons

- neuroglia

- optical coherence tomography

- retina

- iris

- cornea

Schizophrenia is a psychotic disorder characterized by disturbances in multiple mental modalities and personality, the worldwide prevalence is 1% [1, 2, 3]. The disorder develops clinically in early adulthood, and it is rare before the age of 16 years. Patients with schizophrenia have a reduced mean life expectancy about 15 years shorter than the general population and a 5% to 10% lifetime risk of death by suicide [1, 2]. The spectrum of potential clinical manifestations includes psychopathological changes in thinking such as delusions or disorganization of thoughts, hallucinations, a disturbed self-perception, impaired attention and social cognition, loss of motivation, catatonia, as well as a disturbed behaviour including unpredictable or inappropriate emotional responses [1, 2, 3]. The understanding of the pathogenesis of schizophrenia is still limited, but there is agreement that the disease is multifactorial and that its pathogenesis begins early during neurodevelopment. Factors involved in the pathogenesis are alterations of several risk genes, changes in epigenetic regulation, and dysregulation of the cerebral transmitter system. There is also a higher probability of schizophrenia occurring in adolescence after a trauma during birth or childhood, and as a result of drug abuse [1, 2, 3]. The criteria and requirements for the diagnosis of schizophrenia were defined both in the current 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) published by the World Health Organization [3], and also in the current 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) published by the American Psychiatric Association [4]. According to ICD-11 and DSM-5, an essential criterion for the diagnosis is the presence of at least two of the five main symptoms of schizophrenia: (1) delusions, (2) hallucinations, (3) disorganized speech (thinking), (4) disorganized or catatonic behaviour, and (5) negative symptoms such as affective flattening or anhedonia. At least one of these symptoms must be (1), (2), or (3) [4]. Two further requirements for the diagnosis are the presence of the symptoms for a period of 1 month or more, and it must be ruled out that the symptoms are due to other illnesses (e.g., brain tumors) or to the effects of medication, drugs or withdrawal [3, 4]. Since the diagnosis of schizophrenia has so far been based solely on psychiatric criteria and no single symptom is pathognomonic for the disease, the intention is to expand the clinical spectrum of examination methods, also with the aim of diagnostically supported observation of the patient’s course and research into potential biomarkers of schizophrenia. Important examples of these efforts are studies on biomarker molecules in the peripheral blood, as well as genetic and epigenetic research and functional studies using task-associated or resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [5, 6, 7, 8]. Another important aspect in this context is the detection of morphological alterations, whereby the contribution of several specialist disciplines should be emphasized. In the following review, the findings to date on morphological changes in schizophrenia will be presented and their potential significance in the context of integrative diagnostics and further research into schizophrenia will be outlined. Due to the continuous improvement in the resolution of magnetic resonance imaging, neuroradiology plays a central role in the morphological investigation of structural changes in the central nervous system, including structural anomalies. This also applies to genetic and epigenetic research with regard to possible correlations between molecular findings and brain morphology. Also important are ultrastructural findings in neuropathology and the question of whether neuropathology can confirm significant radiological findings in schizophrenia patients. Finally, ophthalmology plays an additional role, as significant changes in the retina, iris and cornea have also been described in schizophrenia.

The first report of structural changes on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in schizophrenia patients by Johnstone and coworkers [9] showed a significant enlargement of the lateral ventricles in 17 patients compared to 8 age-matched control persons. This finding was subsequently replicated in several MRI-studies [10, 11, 12] and can be considered the first morphologic change detected in schizophrenia. Another important morphological change in the brain of patients with schizophrenia is a statistically significant reduced cortical thickness compared with control groups consisting of age-matched healthy persons. This result has been described in several studies and mostly, it was determined by MRI-examinations using voxel-based image analysis methods (VBM) or region of interest examinations (ROI) [10, 11, 12]. Compared to healthy control persons, the reduced cortical thickness is found in almost all brain regions. The grey matter is particularly reduced in the frontal and temporal cortex as well as in the insular region. The hippocampus, the corpus amygdaloideum and the thalamus also show a significant reduction in grey matter volume [10, 11]. With regard to the nucleus accumbens, a reduction in volume is also described in individual studies [10, 13, 14]. The direct comparison with other brain disorders such as bipolar disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder shows a significantly more pronounced reduction in cortical thickness in schizophrenia, whereas an increased thickness of the cortex was found in the frontal region in autism-spectrum disorders and in 22q11 syndrome, which will be discussed in the chapter on genetic influences [10]. Automated segmentation of hippocampal subfields revealed a significant reduction in the volume of the cornu ammonis and dentate gyrus in addition to the reduced overall volume of the hippocampus. This volume reduction was significantly more pronounced in schizophrenia patients compared with patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) [15]. The so-called “incomplete hippocampal inversion” (IHI) is a variant of the hippocampus anatomy characterized by a more medial position with flattening due to a smaller vertical diameter compared with the horizontal diameter in coronary images. IHI occurs frequently in patients with epilepsy but also in healthy individuals. In a community-based study of 2008 persons, it was observed that the occurrence of IHI on the left side is more frequent in the population (17%) than on the right side (6%) [16]. The prevalence of IHI was also investigated in an MRI study of 199 schizophrenia patients and 161 healthy control persons. Left-sided IHI was found in 27% of the patients compared to 15% of control cases. On the right side, 10% of the patients and only 4% of the controls had an IHI [17]. Confirming the hypothesis of a frequent occurrence of IHI in schizophrenia patients with visual hallucinations, left-sided examination revealed IHI in 10 of 11 patients with the combination of visual and auditory hallucinations, in 6 of 14 patients with exclusively visual hallucinations, and in 8 of 16 persons from a control collective. Since IHI is common in premature infants, the prevalence of IHI in schizophrenia patients with hallucinations is interpreted as a disturbance of the hippocampal development [18]. The results of these two studies support the hypothesis of a higher prevalence of IHI in schizophrenia patients, as well as the more frequent occurrence of IHI in those schizophrenia patients with visual hallucinations. It seems premature at present to conclude that populations with a higher prevalence of IHI, i.e., patients with epilepsy or preterm infants, are more susceptible to schizophrenia, although it is known that children with very low birth weight are more likely to manifest a psychopathological profile in adulthood [19]. It is emphasized that the impact of IHI deserves further exploration in studies of the hippocampus in schizophrenia [17].

The volume of the pallidum is significantly enlarged in schizophrenia patients, as is the volume of the putamen to a lesser extent, as well as the two lateral ventricles and the third ventricle [10, 11, 12]. These findings of a reduced cortical thickness and enlarged pallidum were confirmed in another study in a collective of 133 patients with chronic schizophrenia compared with 403 non-affected individuals. Of note, however, 45% of these patients demonstrated no significant changes regarding the volume measures of cortical and subcortical structures compared with the control group. In the same study, 163 untreated first-episode patients were investigated and only 20% of these patients showed the typical reduction in cortical thickness, whereas the other patients showed no significant morphological changes in the brain. Patients showing no morphological changes performed better on the digit sequencing and verbal fluency tests, but there were no significant differences between the subgroups of the patients regarding the frequency of positive and negative symptoms as measured by the positive and negative syndrome score (PANSS) [13]. In schizophrenia patients on antipsychotic medication, independent studies found a significant reduction in grey matter volume compared to non-treated patients, and additionally, the volume reduction significantly correlated with the cumulative amount of antipsychotics administered and with the duration of illness [20, 21]. In contrast, the pallidum and putamen in particular show a significant positive correlation of volume with the cumulative dose of antipsychotic medication, as well as a significant increase in volume in cases of schizophrenia in the early and chronic stages when compared with control cases [14]. When interpreting the influence of medication on brain morphology, it is emphasized that the exact mechanism of grey matter reduction is still largely unknown and that it is not possible to reliably differentiate the influence of medication from the influence of the duration of illness on the morphological changes described. A combined effect of antipsychotic medication and the progression of the disease is hypothesized [20, 21]. In this context, longitudinal structural MRI studies make an important contribution to the question of changes in morphological aspects during the clinical course of schizophrenia patients. These studies have confirmed a decline in multiple grey matter regions such as frontal and temporal areas, thalamus, and cingulate cortex over time [22, 23]. Also, the explicit investigation of patients with a first episode psychosis revealed a decline in multiple grey matter regions over time as well as progressive cortical thinning in the superior and inferior frontal cortex [22]. An important link to the clinical behavior of patients was shown in a longitudinal study, in which a significant negative correlation was found between the extent of aggressive behavior of the patients and the extend of the longitudinal volume reduction of the hippocampus. According to the authors, these findings reinforce the hypothesis that altered structural brain development coincides with development of more externalizing behavior [23]. As in the previously mentioned studies [20, 21], the authors of these longitudinal studies emphasize that the results should be interpreted with caution, also with regard to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, because findings might be confounded by longer periods of treatment and higher doses of antipsychotics or even other epiphenomena related to the illness such as social situations and lifetime risk factors [22, 23, 24]. Another aspect of the MRI examination of morphological aspects in schizophrenia is the examination of clinically unremarkable first-degree relevants of schizophrenia patients. Previous studies have shown that the differences are discrete when comparing clinically asymptomatic first-degree relevants of schizophrenia patients with healthy controls. Two independent studies showed a significant volume reduction especially in the area of the left cornu ammonis [25] and in the area of the left inferior temporal gyrus and the fusiform gyrus [26], but not on the contralateral side or in other brain regions [25, 26].

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have investigated white matter integrity in schizophrenia patients, with fractional anisotropy (FA) measurement being the most important parameter in all studies. The FA value of normal white matter tracts is high due to the predominance of unidirectional axonal directions, whereas FA values are lower in white matter tracts with pathological microstructural changes such as axonal damage. Some studies are limited to the detection of FA. Other studies additionally determined axial diffusivity (AD) as another measure of axonal integrity, and radial diffusivity (RD), which has an increasing value in myelin damage such as demyelination. Furthermore, mean diffusivity (MD) is another important DTI parameter that shows increasing values in case of altered cell membrane function, oedema or other cellular injury [27, 28, 29, 30]. The main finding of the DTI studies showed widespread alteration of most brain white matter tracts compared to healthy controls. A constant in these studies was a lower value for FA and a higher value for RD and MD in many different brain regions [27, 28, 29]. Axonal diffusivity showed regional variation with higher values in the fornix and uncinate fasciculus, both important limbic white matter pathways, and no change in the corpus callosum and cingulate gyrus compared to healthy controls [28]. Regarding the whole cerebrum, the regions with a pronounced change in white matter integrity were the corpus callosum, longitudinal superior fasciculus, internal and external capsule, posterior thalamic radiation, fornix and uncinate fasciculus [27, 28, 29]. Based on the finding of reduced FA together with increased values for RD and MD, it is assumed that these changes are due to an interruption of the brain connections in combination with myelin damage. However, the underlying pathobiochemical and molecular mechanisms are still largely unknown [27]. An important step in this regard is the confirmation of an increased amount of free water (FW) in the white matter tracts of schizophrenia patients, which was detected using a specific bi-tensor diffusion model that characterizes the amount of FW. Since an increased amount of FW occurs in conditions such as vasogenic oedema and neuroinflammation, the authors hypothesize that the amount of FW may indicate a combination of these processes, which is consistent with the hypothesis of immune activation in schizophrenia [31]. Differences in white matter diffusion imaging were also found between different collectives of schizophrenia patients. Compared to patients without hallucinations, schizophrenia patients with auditory verbal hallucinations showed significantly lower FA levels in many regions such as the anterior thalamic radiation, the corticospinal tract, the cingulate gyrus, and the superior longitudinal fasciculus, which is known to be connected to the speech association cortex [32]. Moreover, the comparison between schizophrenia patients with high and low cognitive performance based on the cognitive composite score revealed significantly lower FA values in the latter group in widespread white matter regions of the whole brain. Correlation analysis showed a significant positive relationship between the FA values in the fronto-temporal part of the left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF) and the global assessment of function score (GAF). The IFOF is the longest associative bundle and connects the occipital cortex, the superior parietal lobe and the temporal basal areas with the frontal lobe. Therefore, the authors consider neurobiological changes in the IFOF, as evidenced by reduced FA levels, as a probable cause of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia patients [33].

Anomalies of the brain represent neurodevelopmental changes and are associated

with the occurrence of schizophrenia in individual cases. Etiologically, genetic

changes in the form of biallelic variants or mutations are of great importance,

and they mainly affect genes that also play a role in the aetiology of

schizophrenia itself. Important examples are structural variants of the

reelin gene, as well as the genes for Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4

(ErbB4) and for neuregulin1 (NRG1) [34, 35, 36]. Reelin is expressed in

| Macroscopic findings in Schizophrenia | References | |

| 1. Enlargement of the lateral ventricles | ++ | [9, 10, 11, 12] |

| 2. Reduced cortical thickness in nearly all cortical regions | ++ | [10, 11, 12] |

| 3. Reduced volume of the hippocampus and its subfields | ++ | [10, 11, 15] |

| 4. Enlarged Pallidum | ++ | [10, 11, 13] |

| 5. Impaired integrity of the white matter as detected by DTI | ++ | [27, 28] |

| 6. More frequent occurrence of an incomplete hippocampal inversion (IHI) | (+) | [18] |

| 7. Focal alterations of the cortical gyrification | (+) | [39, 40, 41, 42, 43] |

| 8. More frequent occurrence of anomalies (heterotopias, cavum septum pellucidum) | (+) | [44, 45, 46] |

“++”: strong evidence for the statistical significance of these findings compared to a control group of healthy persons;

“(+)”: important results of individual studies with the need for further research.

The genetic influence on the development of schizophrenia (SZ) has been proven by demonstrating a high heritability rate of up to 80% of cases [53, 54]. The concordance rate for SZ has been estimated at 33% for monozygotic twins and 7% for dizygotic twins [53]. Most genetic studies such as linkage studies or genome-wide association studies (GWAS) deal with the question of genetic markers of SZ in comparison to control cases and some studies also deal with genetic differences between patient collectives with different clinical phenotypes, such as the predominance of positive or negative symptoms [53, 54, 55]. Only some of the studies investigated the question of a possible correlation between genetic and morphological findings, mostly in combination with MRI studies. Many genes throughout the human genome are involved in SZ, important genes that have been observed in several studies using multivariate data analysis are listed in Table 2a (Ref. [7, 34, 35, 36, 56, 57, 58, 59]). Just like the three genes reelin, ErbB4 and NRG1 previously described in Chapter 3 (“Brain development abnormalities”), all the genes listed in Table 2a,2b (Ref. [7, 34, 35, 36, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66]) are expressed in many different cell types within the CNS and some also outside the CNS. It is repeatedly emphasized that all these genes have multiple functions and that their involvement in different pathways, several cellular and molecular aspects, and their functions during embryonic development and in the postnatal and adult brain are still largely unknown and they are still being elucidated [35, 36, 56, 67]. This also applies to their role and that of their various alleles in the pathogenesis of morphological alterations and brain anomalies. The exact role of these genes regarding the pathophysiology of schizophrenia are still elusive, and in particular, no consistent up- or down-regulation of these genes was detected in SZ compared to control cases. The most frequently described functions of these genes are listed in Table 2a,2b. An important observation in this context is the fact that the enrichment of common gene variants in SZ occur predominantly in genes expressed in neurons of the central nervous system, both excitatory and inhibitory neurons, suggesting that neurons are the major site of pathology in SZ [7]. A further important step in understanding the genetic influence on the evolution of SZ is the Neanderthal Selective Sweep Score (NSS), which enables a distinction to be made between genes that arose after the evolutionary separation of Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis (low NSS) and phylogenetically older genes (high NSS). Gene loci associated with SZ have been shown to be significantly more common in those genomic regions that were subject to positive selection in Homo sapiens (low NSS) [68]. One of the strongest genetic risk factors for SZ is the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, which affects many organs such as CNS, heart and facial dysmorphia. This syndrome is associated with a 30–40% lifetime risk of developing SZ. In the CNS, enlargement of the cerebral cortex is typical and polymicrogyria may occur. The exact cause of the increased risk of SZ is unknown [1, 10, 69]. Currently, further schizophrenia-associated genes are being described, an important example is the gene for the cAMP-specific cyclic phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B) showing an upregulation in pluripotent neuronal stem cells and dentate gyrus granular cells of schizophrenia patients [70]. Another example is the gene for the Leucine-rich repeat and immunoglobulin domain containing protein 1 (Lingo1) showing a high frequency of the allele rs3144 and hypomethylation of surrounding CpG sites in a subclass of schizophrenia patients with generalized cognitive deficits [71]. The latter study also confirms the importance of epigenetic changes for the genesis of SZ, with all forms of epigenetic modifications playing a role [71, 72]. In experimental models of SZ, altered methylation has been demonstrated in several genes, an important example being the increased methylation of the promoter region of the reelin (RELN) gene [58]. Different forms of histone modification such as acetylation, methylation and phosphorylation, as well as the influence of non-coding RNA molecules have also been described [58, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78]. Examples of these influences are an increased expression of histone methyltransferases acting on histone H3K9 [75], the upregulation of several micro-RNAs (miRNAs) [76], as well as downregulation of the majority of circular RNAs (circRNAs) investigated in schizophrenia [77, 78].

| Gene | Full name | Locus | Major function of the encoded protein |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRG1 | Neuregulin 1 | 8p12 | Induction of differentiation of glial, neuronal and muscle cells |

| GRIN2A | Glutamate receptor subunit 2A | 16p13.2 | Subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor involved in long-term potentiation |

| DISC1 | Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 | 1q42.2 | Regulation of embryonic and adult neurogenesis |

| COMT | Catechol-O-methyltransferase | 22q11.2 | Transfer of methyl groups to catecholamines including dopamine |

| RELN | Reelin | 7q22.1 | Control of cell-to-cell contact during neuromigration |

| NRGN | Neurogranin | 11q24.2 | Part of a protein kinase C-cascade during synaptic development |

| TCF4 | Transcription factor 4 | 18q21.2 | Multifunctional regulation of neuronal differentiation |

| Gene | Full name | Locus | Major function of the encoded protein |

| TOP3B | DNA topoisomerase III Beta | 22q11.2 | Involvement in the regulation of DNA replication and transcription |

| TBR1 | T-box brain transcription factor 1 | 2q24.2 | Participation in multiple aspects of cortical development and axonal projection |

| ASCL1 | Achaete-scute family BHLH transcription factor 1 | 12q23.2 | Transcription factor in neuronal differentiation |

| TMX2-CTNND1 | Thioredoxin related trans-membrane protein 2-catenin | 11q12.1 | Read-through transcript between the neighboring TMX2 and CTNND1 genes |

| ERVWE1 | Endogenous retrovirus group W Envelope Member 1 | 7q21.2 | Participation in the apposition and subsequent fusion of membranes |

| Micro-RNA | Full name | Locus | Presumed function of the miRNA-variant |

| miRNA-137 VNTR4 | Four-repeat-variant VNTR4 of micro-RNA-137 | 1p21.3 | Dysregulation of miR-137, leading to altered neuroanatomical development |

| miRNA-137 rs1625579 | High risk variant rs1625579 of micro-RNA-137 | 1p21.3 | Dysregulation of protein kinase A signaling |

Relationships between genetic findings and cerebral phenotype have been

investigated by calculating the individual polygenic risk score (PRS) for

schizophrenia based on GWAS. In addition,

individual genes were also studied in vitro or experimentally to gain

more insight into their precise function and contribution to the development of

schizophrenia, including possible morphological changes. Consistent with the

results of MRI studies, the reduction in cortical thickness is an important

finding that shows a significant correlation with PRS in many GWAS. Reduced

thickness is most commonly found in the frontal and temporal lobes and in the

insular region [67, 79]. However, these results are not reported in all genetic

studies. It must be pointed out that the primary results of the studies show many

genes that have a univariate significant correlation of their expression with

changes in different brain regions, but statistical correction for multiple

comparisons using the so-called “false discovery rate” may result in the

observation, that multivariate statistical correlation between PRS

and morphology is no longer significant [80]. In contrast to

cortical thickness, no significant correlation was found between PRS and grey or

white matter volume, with the exception of a smaller volume of the hippocampus

[73]. Results regarding total brain surface area are variable, with some studies

showing a significant correlation with PRS [67, 81]. Results regarding the

relationship between PRS and fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, resting

state fMRI, and task-related fMRI are also inconsistent, with only some studies

showing a significant correlation [79, 82, 83]. Further experimental approaches

were able to show potential links between brain morphology and changes in

individual genes associated with schizophrenia as listed in Table 2b. Together

with the knockdown of the TCF4 gene listed in Table 2a, the knockdown of

the genes TOP3B and TBR1 listed in Table 2b also showed a

reduction in the synaptic density of mouse neurons. Based on the results of

proteomic in vitro-analyses, the authors hypothesize a functional

convergence of these three genes with the expression of syntaxin 1A, which is

involved in synaptic vesicle docking and known to be downregulated in the brains

of patients with schizophrenia [59]. Knockdown of another gene involved in

neuronal differentiation, ASCL1 (Table 2b), led to downregulation of

many other genes involved in cell mitosis, neuronal projection, neuropeptide

signaling and synapse formation. Most of these downregulated genes are known to

be associated with schizophrenia, but also with other neurodevelopmental

disorders. The authors hypothesize that downregulation of ASCL1 contributes to

the development of schizophrenia primarily by slowing cell proliferation and

negatively affecting neuroplasticity. Although this study does not provide

quantitative morphological observations, the confirmation of a direct association

of ASCL1 with cellular proliferation and plasticity should be considered

as an important indication of its potential influence on neuronal cytomorphology

in schizophrenia [60]. This is also true regarding the gene for the glutamate

ionotropic receptor AMPA type subunit 1 (GRIA1), which shows an inverse

correlation with cortical thickness in schizophrenia, i.e., higher gene

expression in cases with reduced cortical thickness. It is hypothesized that this

correlation is due to the inhibitory effect of GRIA1 on synaptic transmission in

glutamatergic neurons [61]. Another study confirmed that the cortex of patients

with schizophrenia is significantly thinner compared to controls and that there

is a significant association between schizophrenia and four single nucleotide

variants (SNVs) of different genes. Notably, the presence of SNV20673

within the TMX2-CTNND1 gene was significantly associated with a thinner

cortex in the right pars triangularis of the frontal lobe in schizophrenia

patients compared to schizophrenia patients without this SNV. In addition, a

thinner cortex in this region correlated significantly with poorer performance of

the logical memory test, especially in patients with schizophrenia. According to

the authors, this result underlines the contribution of individual genetic

variants to the pathogenesis of schizophrenia and to morphological changes in

specific brain regions of schizophrenia patients [62]. Another gene that is

frequently upregulated in schizophrenia, ERVWE1 (Table 2b), is one of

the human genes derived from ancient retrovirus infections. ERVWE1 was

upregulated in brain samples from schizophrenia patients compared to those of

healthy controls, and in vitro assays showed downregulation of the

wingless-type (WNT) signaling pathway via upregulation of micro-RNA-141-3p caused

by upregulation of ERVWE1. This WNT-down-regulation led to a significant

reduction in dendritic spine density and spine length in hippocampal neurons,

which is considered to be one of the most important causal factors for

schizophrenia [63]. miRNA-137 is one of the major microRNAs reported to be

involved in the development of schizophrenia through its dysregulation. In

addition to reports of upregulation of its expression in many cases of

schizophrenia [76], sequence variants of miRNA-137 have also been investigated,

such as a four-repeat sequence consisting of 4

Previous studies of neuropathological changes in schizophrenia are mainly based

on histological post-mortem investigations. Limiting factors for post-mortem

findings are usually limited case numbers, which rarely reach the case numbers of

radiological cohorts. Furthermore, the schizophrenia patients examined are mostly

older people in an advanced stage of the disease, so that the results of

neuropathological studies are only comparable with the findings of in

vivo studies to a limited extent [84, 85]. The central neuropathological finding

is the confirmation of the radiological findings of enlarged lateral ventricles

and reduced grey matter volume in numerous cortical regions when compared with

control collectives. In addition, most histological studies show no change in the

numerical density of the cortical neurons, but evidence for a reduced size of the

neurons [84, 86, 87, 88]. It should be added that these measurements in standard

histological sections of approx. 4

An important ultrastructural observation in schizophrenia is the reduced density of dendritic spines in cortical neurons [90, 91]. This reduction could also be determined in vivo by positron emission tomography (PET) using the tracer [11C]-UCB-J, which detects the vesicle protein 2A, which in turn is specific for dendritic spines [92, 93]. Dendritic spines are small membrane-like protrusions on the dendrites of neurons and represent an important unit for excitatory glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Reduced expression of D-serine, an important co-factor for the activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA-R) [90, 91], has been described as a key factor for the degeneration and thus the numerical reduction of dendritic spines. Physiologically, NMDA-R is activated by initiating an ion flux including Ca2+ after receptor binding of glutamate and the co-factor D-serine. In contrast, the sole receptor binding of glutamate without co-factor causes a non-ionotropic activation and a consecutive dysfunctional signaling of NMDA-R, which leads to the degeneration of the dendritic spines [91]. This degeneration also affects GABAergic inhibitory neurons because dendritic spines have also been described on inhibitory neurons. They show a marked similarity to those dendritic spines in excitatory neurons, as they also receive excitatory synapses with glutamatergic NMDA-R and display activity-dependent morphological plasticity [94]. Dysfunction of inhibitory neurons in schizophrenia mainly affects GABAergic interneurons expressing parvalbumin (PV) resulting in disinhibition of excitatory glutamatergic pyramidal cells and a further increase in the aberrant non-ionotropic activation of the NMDA-receptors leading to a further damage of dendritic spines [90, 91]. In post-mortem studies, a significantly reduced density of perineuronal networks (PNNs) was detected in the parvalbumin-containing GABAergic interneurons of the frontal and temporal cortex and the hippocampus, but not in the brains of patients with bipolar disorder or healthy controls [87, 95]. PNNs are part of the extracellular matrix and consist of hyaluronan, chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans, linker proteins and tenascin-R. They are involved in the physiological interrelation of GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons, and it is hypothesized that the loss of PNNs in parvalbumin-positive interneurons in schizophrenia patients reduces the inhibitory function of these GABAergic interneurons [87, 95, 96, 97, 98]. A reduction in PNNs and parvalbumin-containing interneurons was also observed in a mouse model of schizophrenia with mutations in the DISC1 gene (Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1) compared to control subjects at different age points. According to the authors, this aberrant development of PNNs and interneurons impairs normal neuronal processes and contributes to the typical behavioural phenotype of this mouse model of schizophrenia, which includes decreased sociability, decreased novelty, and increased ultrasonic vocalizations [99].

In addition to the dysregulation of NMDA-R and GABAergic interneurons and their

influence on glutamate release, the hyperactivity of dopamine at the D2 receptors

in the striatum is another central factor in schizophrenia, as it is responsible

for the occurrence of positive symptoms. The exact pathways leading to the

increase and hyperactivity of dopamine in schizophrenia are still elusive, but it

is likely that a deficit in inhibitory GABA neurons and increased glutamate

release are a major cause of the dopamine increase [100, 101, 102]. There is also

evidence of increased dopamine activity at D1 receptors of pyramidal cells,

especially in the prefrontal cortex, and the consequences of this overactivity

are particularly complex, as D1 receptors are also present in interneurons and

can influence both excitatory and inhibitory microcircuits of the prefrontal

cortex and thus its influence on the striatum [95]. To add to the complexity,

interneurons with D1 receptors, interneurons with D2 receptors and those with

both receptors are distributed throughout the striatum. Dysregulation of

interneuron circuitry, and in particular inhibition of parvalbumin-containing

interneurons, is thought to be a major factor in the interaction between

NMDA/glutamate receptors and dopaminergic D1 and D2 receptors, which leads to a

dysregulation of the glutamatergic and dopaminergic transmitter system in

schizophrenia [14, 100, 101, 102]. It is further emphasized that the current molecular

understanding of the interactions between the transmitter systems glutamate, GABA

and dopamine in schizophrenia has improved, but it is still insufficient for the

understanding of the entire pathophysiology, also with regard to morphological

changes in certain brain regions such as the striatum. One important finding is

that higher striatal dopamine synthesis and higher dopamine release correlates

with worsening of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia patients. There is

consensus that further research is needed to clarify whether this change in the

dopaminergic system together with the increased activity of pyramidal neurons and

the shift in the excitatory/inhibitory balance have a direct influence on the

anatomical change in the size of the striatum in schizophrenia [14, 100, 101, 102]. The

GABAergic, glutamatergic and dopaminergic systems also do not fully explain the

pathophysiology of the transmitter system in schizophrenia, as cortical

hyperfunction of serotonin/5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT2A) can also lead to

psychosis. In particular, the functional interaction between 5-HT2A and the

glutamatergic system via the formation of heterodimers of 5-HT2A with the

metabotropic glutamate 2 receptor (mGluR2) and their possible implication in

schizophrenia are the subject of current research [100, 103]. This also applies to

the cholinergic system. The number of neurons containing muscarinic

(metabotropic) M1 receptors (CHRM1+) is reduced in patients with schizophrenia

compared to controls in the prefrontal cortex and primary visual cortex, in the

medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus and in the hippocampus. Cortical pyramidal

cells with CHMR1+ in the prefrontal cortex are particular important for the

maintenance of cognitive function, as well as pyramidal cells in the primary

visual cortex for the modulation of visual attributes such as shape, position and

movement. The authors therefore hypothesize that the loss of these neurons with

metabotropic choline receptors contributes to the cognitive deficits and

visual-related symptoms of patients [104]. Nicotinic (ionotropic)

As far as the glial cells are concerned, the increased density and activation of microglia is an important finding. Using the specific histologic marker for human leukocyte antigen class II (HLA-DR), an increased numerical density of microglia was detected in the frontal and temporal cortex of patients with chronic schizophrenia. The increased density was detectable in all cortical layers and was particularly pronounced in cortical layer VI near the white matter [107]. Other studies also found an increased density of microglia in the auditory association cortex and in the thalamus [87, 108]. As evidence for the immune activation of microglia, PET studies have shown a significant increase in various tracers for the 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO), which is considered specific for activated microglia [109, 110]. To date, there is no clear evidence that bacterial, viral or fungal infections play a major role in the pathophysiology of neuroinflammation in schizophrenia, and the focus of previous research has been on maternal inflammation and the possibility that microglial activation may occur during embryogenesis. Based on current experimental evidence, it is likely that activated microglia dampen the proliferation of glial progenitor cells and lead to a disrupted white matter structure, resulting in an increased number of non-myelinated axons and reduced myelin thickness [111]. It is also assumed that activated microglial cells contribute to deficits in the differentiation of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes [111, 112, 113]. More studies are needed to show, whether the microglia-induced changes are a possible explanation for the alterations of the white matter as shown in MRI studies [111, 112, 113]. A strong indication of degenerative processes in microglia and oligodendrocytes of schizophrenia patients is the ultrastructural evidence of a reduced volume density and a reduced number of mitochondria as well as an increased number of lipofuscin granules in both cell types in the prefrontal cortex [112]. In contrast to microglia, the cell density of oligodendrocytes is not increased in schizophrenia, but decreased in various cortical and subcortical regions including the hippocampal subfield CA4 [114]. It is considered very likely that all these changes lead to impaired myelination and neuronal uncoupling, which is associated with altered functional connectivity and subsequent cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia [111, 114]. Astrocytes are involved in the delivery of glutamate to neurons, buffering of potassium and neuromodulatory activity. In a post-mortem study, a comparison with a control collective showed reduced expression of specific markers such as aquaporin-4, S100ß, glutaminase and excitatory amino acid transporter 2 in astrocytes in the deep cortex layers, suggesting that astrocytic pathology in schizophrenia is region-specific and may be the cause of glutamatergic dyshomeostasis [115]. Other experimental studies in rodent models also support the assumption of a link between astrocytes and schizophrenia, such as studies in mice with mutation of the astrocytic excitatory amino acid transporter 1 (GLAST), which were found to have behavioural abnormalities that are considered a model for the positive, negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia [116, 117, 118]. Overall, current evidence suggests that astrocytes are involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, although it is emphasized that the underlying mechanisms need to be further investigated [118]. A numerical reduction of astrocytes has only been reported in a few studies and this finding is rather the exception [111, 115, 119]. Remarkably, there are no reports of a clear increase in the numerical density of astrocytes in any brain region. This supports the view that there is no astrogliosis in schizophrenia.

Since the introduction of optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the early 1990s, non-invasive and quantitative morphological assessment of non-transparent structures of the eyeball has been possible. Since then, the retina in particular has been the subject of scientific interest. In schizophrenia, but also in other neurological and psychiatric diseases such as bipolar disorder, a significantly reduced thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and the macula has been reported compared to control collectives. Individual studies also report a significantly reduced thickness of the retinal GCL and the inner plexiform layer (IPL) [120, 121, 122, 123, 124]. The RNFL contains the axons of the ganglion cells that form the optic nerve, which leaves the retina and forms synapses on the neurons of the lateral geniculate nucleus (CGL). From the CGL, retinal information is transmitted to the visual cortex. As in the other cortex regions, a reduced cortical thickness was determined in the visual cortex of schizophrenia patients, but there is no evidence for a reduced volume of the CGL [123]. The results regarding the relationship between the degree of reduced retinal thickness and the severity of schizophrenia symptoms are variable, with some studies reporting a significant positive correlation between retinal thinning and positive and negative symptoms according to the PANSS score, while other studies found no significant correlation [123, 124, 125]. Two independent studies have shown that thinning of the GCL correlates significantly with poorer performance on a number of neuropsychological and language-related tests such as the verbal fluency test or the trail making test, suggesting that structural changes in the retina are associated with some specific cognitive domains in schizophrenia patients [126, 127]. This is supported by electroretinography studies, which confirmed pathological changes in schizophrenia patients, such as reduced amplitudes of a- and b-waves [122, 128, 129]. Several hypotheses have been formulated for the occurrence of retinal dysfunction and thinning in schizophrenia, including the possibility of retrograde transsynaptic degeneration of retinal axons or genetic factors coinciding with the predisposing factors for schizophrenia. Another important hypothesis is the dysregulation of dopaminergic signaling from amacrine cells to the glutamatergic ganglion cells, leading to cellular and axonal damage [120, 124, 130]. Changes concerning the vessels of the fundus have also been described, with dilatation of the venous vessels in particular. For the arteries, some studies report a narrowing of the diameter of the arterioles, but this finding is not reproduced in every study [121, 123, 131]. The density of the entire vasculature was quantified around the fovea showing a lower vascular density with a wider, non-vascularized fovea in schizophrenia patients [131]. Even the shape of the venous and arterial trajectories near the fovea were examined and it was confirmed that the trajectories in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are straighter and have flatter curves compared to a control group [132]. The authors are cautious in their discussion of possible explanations for these vascular findings, hypothesizing that chronic hypoxia of the patient’s brain may play a role in the dilation of the venous vessels [123, 131, 132].

The retina is not the only part of the eye that is morphologically altered in schizophrenia. Tian and coworkers [133] examined the iris with an iris image collector and found significantly more schizophrenia patients with iris crypts (39 of 41 patients) compared to healthy controls (14 of 38 individuals). This result is in contrast to an earlier study by Trixler and Tényi [134], who found no such difference between 32 schizophrenia patients and 31 controls [133]. However, both studies found a significantly higher frequency of patients with pigmented spots. Tian and colleagues [133] also investigated the frequency of wrinkles and found no significant difference between the two groups. The clinical significance of these findings is emphasized by a significant positive correlation of the number of iris crypts with the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) in untreated first-episode patients, and furthermore, the number of pigment spots and wrinkles of the iris were positively correlated with the patients’ negative symptom score [133]. The authors therefore hypothesize that iris crypts, pigment spots and iris wrinkles could be external manifestations of abnormalities in the neurotransmitters and/or neuronal pathways of the brain [133]. An indication that this hypothesis is correct is the involvement of several genes such as the genes for the proteins Hect Domain and RCC1-Like domain-containing protein 2 (HERC2) and oculocutaneous albinism II melanosomal transmembrane protein (OCA2) in the development of iris pigmentation as well as in the development of the nervous system and neurodevelopmental disorders [133, 135, 136]. The authors hypothesize, that polymorphisms of the genes for HERC2 and/or OCA2 may be a reason that a higher incidence of iris pigment spots are detected in schizophrenic patients than in healthy controls [133]. In addition to the changes in the iris itself, several studies have also reported a blunted pupillary reflex in schizophrenia patients, which occurred in task-related experimental situations. In two independent studies by Thakkar et al. [137] and by Fattal and coworkers [138], a significantly reduced constriction amplitude of the pupillary light reflex in schizophrenia patients compared to healthy control persons was observed using a pupillometer during the performance of a saccadic double-step task and controlled light presentation. Additionally, both studies found a significant association of a reduced magnitude of the pupil response with the degree of negative symptom severity in the patients [137, 138]. Several hypotheses for these findings have been discussed by the authors, including a more general reduction of preparation of schizophrenia patients to move the eyes, exert voluntary control over the eyes, or both [137]. A second important hypothesis is, that the blunted pupillary reflex might be due to retinal abnormalities that reduce the effective luminance of the light stimulus [138]. Further research is addressed by the authors with regard to the underlying pathophysiology and a possible predictive ability of the pupillary light reflex to assess the onset and development of negative symptoms [138]. A reduced nerve fiber density was found in the cornea of schizophrenia patients using confocal corneal microscopy (CCM), and the length and number of nerve branches were also significantly reduced compared to a control group. These results remained significant even when patients with hypertension, diabetes mellitus or other metabolic disorders associated with possible pathological changes in the nerves were excluded [139]. CCM offers the possibility of selective examination of all four corneal layers (epithelium, nerve layer, stroma, endothelium) and is used diagnostically in various diseases such as diabetic neuropathy, endothelial dystrophy or fungal keratitis. In this first systematic application of CCM in schizophrenia, the 36 patients and the 26 persons in the control group could be statistically separated from each other with a sensitivity and specificity of over 80 % using the above-mentioned nerve measures alone. Comparable to the thinning of the RNFL, the authors discuss the possibility that dopamine dysregulation or even hypoxia could affect not only the brain but also the retina and cornea. Larger longitudinal studies are considered necessary to further confirm the current findings and to determine the predictive ability of CCM for worsening schizophrenia or relapse (Table 3, Ref. [85, 86, 87, 88, 90, 91, 95, 96, 97, 98, 104, 107, 108, 111, 114, 115, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 131, 133, 134, 139]; Fig. 1, [139].)

| Ultrastructural findings in Schizophrenia | References | |

| 1. Confirmation of a reduced grey matter volume | ++ | [85, 86, 87, 88] |

| 2. Reduced size of cortical neurons | ++ | [85, 86, 87, 88] |

| 3. No reduction of the total neuronal density, but evidence for a reduced number of cholinergic neurons in several cortical regions | ++ | [85, 86, 87, 88, 104] |

| (+) | ||

| 4. Reduced density of dendritic spines | ++ | [90, 91] |

| 5. Reduced density of perineuronal networks | ++ | [87, 95, 96, 97, 98] |

| 6. Increased numerical density of microglia in the cortex | ++ | [87, 107, 108] |

| 7. No evidence for an altered numerical density of astrocytes (no astrogliosis) | (+) | [111, 115, 119] |

| 8. Reduced density of oligodendrocytes in several cortical and subcortical areas | ++ | [111, 114] |

| 9. Reduced thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer | ++ | [120, 121, 122, 123, 124] |

| 10. Reduced vascular density around the fovea and widening of venous retinal vessels | ++ | [121, 123, 131] |

| 11. Higher frequency of pigment spots in the iris | (+) | [133, 134] |

| 12. Reduced nerve fiber density in the cornea | (+) | [139] |

“++”: strong evidence for the statistical significance of these findings compared to a control group of healthy persons;

“(+)”: important results of individual studies with the need for further research.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

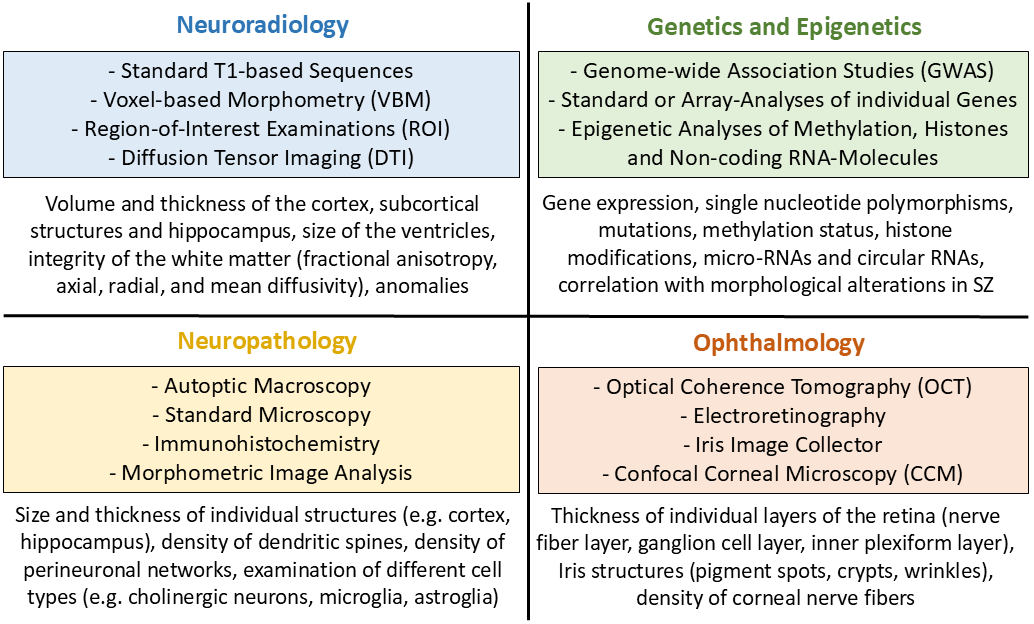

The four disciplines involved in the investigation of morphological alterations in schizophrenia; the most important methods used (coloured fields) and the major structures examined (blank fields). SZ, schizophrenia.

The first conclusion to be drawn from the current state of knowledge is the fact that the morphological changes in schizophrenia can only be researched and understood through the joint contribution of several specialist disciplines. The basis of the macroscopically detectable changes of the grey matter in imaging studies has been further characterized morphologically and molecularly by neuropathological studies. The contribution of nuclear medicine to date is also important for individual issues, such as the detection of a reduced density of dendritic spines or the detection of activated microglia. Genetic and epigenetic findings, in addition to their importance for research into the genesis of schizophrenia, are significant for the investigation of changes in molecular signaling pathways as potential causes of the morphological changes described. The cardinal contribution of ophthalmology is the detection of significant changes in the retina as an integrated component of the central nervous system. In summary of the findings to date, the enlargement of the lateral ventricles, the reduction of the cortical thickness, the enlargement of the pallidum, the disturbance of directional diffusion in the white matter, as well as the reduced thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer represent the most important significant changes in schizophrenia. However, it must be emphasized that although the statistical significance of these changes compared to control groups is given, it cannot be concluded that these changes are diagnostically applicable to individual cases. Especially, many patients with clinically manifest schizophrenia show no detectable changes regarding volumetric measures of cortical and subcortical structures on MRI. Another complicating factor is that the influence of antipsychotic medication on the morphological changes cannot be reliably separated from the influence of the duration of the illness. Nevertheless, the prospect of clinical usability of these parameters is realistic, as many studies have found a correlation with clinical and task-oriented data, for example when comparing patients with and without hallucinations, or when comparing patients with high and low cognitive performance score. In addition, the present review has shown that this perspective is further supported by the large number of other morphological observations that appear worthy of further investigation. Examples include the evidence for a greater frequency of incomplete hippocampal inversion or grey matter heterotopias, the various examples of a correlation between alterations in morphology and alterations of genes or micro-RNAs, as well as the entirety of current ophthalmological findings in the retina, iris and cornea.

The investigation of morphological alterations in schizophrenia should be seen as a sub-aspect alongside other important investigation methods and research areas that are not the subject of this review. fMRI should be mentioned in particular, which has been used to determine significant differences to control subjects [140]. Additional branches of clinically important schizophrenia research are metabolic studies using metabolic imaging and lipidomics [141], electrophysiological investigations [142], as well as ongoing research into genetic and epigenetic aspects, the CNS transmitter system and its receptors, and the abnormal development of CNS progenitor cells [143]. Another current field of research is multimodal imaging, i.e., the simultaneous acquisition of different imaging modalities such as structural MRI, functional MRI and diffusion tensor imaging, as discussed above, as well as metabolic analyses using MRI spectroscopy. Up to now, such simultaneous approaches remain relatively limited in scope, in part due to the complexity of undertaking this type of analysis. A central challenge here is the development of suitable methods for data analysis such as advanced machine learning methodologies for fusing multimodal brain imaging data, broadly categorized into unsupervised and supervised learning strategies. The central goal is to broaden perspectives on the links between the brain and mental disorders. These new multimodal strategies represent a comparably new branch of schizophrenia research that deserves a separate and detailed presentation [144, 145, 146, 147]. The current state of knowledge on morphology encourages the realistic assumption that, following further studies and the development of defined quantitative criteria, routine recording of quantitative morphological data could be a valuable addition in the context of interdisciplinary diagnostics and follow-up of schizophrenia patients. One perspective would be to record the thickness of the cortex and the volume of grey matter and subcortical structures in defined regions, combined with the integrity of the white matter determined by diffusion tensor imaging, as well as ophthalmologically determined changes in the retina.

RN, CTA, and EH designed the review. RN drafted the manuscript and designed the figure and the tables. RN performed the literature search. RN, CTA and EH critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Open Access Publication Fund of Goethe-University Bockenheimer Landstrasse 134-138 D-60325 Frankfurt am Main Germany. VAT: DE212137461.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.