1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Hangzhou Dianzi University, 310018 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 Geriatric Medicine Department, Beijing Hospital, 100730 Beijing, China

3 Institute of Geriatric Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 100730 Beijing, China

4 Digital Technology Research Center, China Electronics Standardization Institute, 100007 Beijing, China

Abstract

Owing to the intricacy of the dementia course and the selection of clinical trial populations, research on distinct populations, comorbid conditions, and disease heterogeneity is currently a topic of great interest. For instance, more than 30% of individuals enlisted for natural history and clinical trial studies may exhibit pathology extending beyond Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Additionally, recent autopsy studies have evinced significant heterogeneity in the neuropathology of individuals who succumb to dementia, with approximately 10%–30% of those clinically diagnosed with AD revealing no neurological lesions at autopsy. Nevertheless, 30%–40% of cognitively intact elderly individuals exhibit neurological lesions at autopsy. This indicates that the brain can withstand accumulated aging and neurological lesions while retaining brain integrity (brain resilience) or cognitive function (cognitive resilience). Presently, there is a lack of consensus on how to precisely define and measure the resilience of the brain and cognitive decline. This article encapsulates the research on constructing multimodal neuroimaging biomarkers for cognitive resilience, summarizes existing methods, and proposes some improvements. Furthermore, research findings on the biological mechanisms and genetic traits of brain resilience were collated, and the mechanisms for the formation of resilience and the genetic loci governing it were elucidated. Potential future research directions are also discussed.

Keywords

- Alzheimer’s disease

- A/T/N framework

- brain network

- genetics

- cognitive resilience

In recent times, there has been a surge in the occurrence of neurodegenerative disorders associated with aging, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). It is noteworthy that in the absence of biomarkers, upwards of 30% of participants selected for a clinical trial study may demonstrate pathologies distinct from AD [1]. Furthermore, current autopsy investigations have demonstrated notable heterogeneity in the neuropathology of individuals who succumb to dementia [2]. To further complicate matters, recent research indicates that individuals who die from dementia may also experience dementia-like ailments, such as age-related (Tubulin associated unit) Tau pathology, Tau astrogliopathy, and hippocampal sclerosis [3]. In view of this, a more accurate delineation of the AD concept is indispensable to establish a standardized framework for researchers, not only to facilitate clinical trials but also to prognosticate the trajectory of dementia and to assist in the formulation of individualized treatment protocols. In 2011, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the Alzheimer’s Association (AA) convened a working group to revise the primary 1984 directives formulated by the National Institute of Neurology and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) and the AD and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA) [4]. The aim of the revision was to devise an alternative set of recommendations based on distinct stages of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to dementia [5, 6]. Notably, in contrast to many other diseases, affirmative biomarkers for AD can predate clinical indications of MCI and dementia by a duration of 15 to 20 years [7]. Hence, dementia is deemed a continuum, and detecting the disease before the clinical onset of AD is considered a significant research priority, as timely intervention offers the highest possibility of successful treatment [8]. In 2018, the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) working group classified AD biomarkers into three dimensions: amyloid deposition, Tau, and neurodegeneration (cortical atrophy or metabolism) (A/T/N) [7]. The relative changes between A/T/N can capture pathological factors that adversely impact cognitive recovery, and the relationship between the three can be described using the residual method [9]. Multimodal imaging integrates various pathologies within the AD continuum, and this classification approach has revealed distinct rates of memory decline [10, 11] and clinical risk [12, 13] in certain A/T/N combination patients. On the other side, the efficacy of information transmission in the brain’s functional connectivity network and the organizational features of functional modules are intimately associated with cognitive resilience [14]. The increased connectivity between specific brain regions facilitates the mobilization of neuronal resources, which could be a mechanism for brain resilience [15, 16]. In addition to imaging features, the genetic characteristics of cognitive resilience are crucial for early intervention and treatment of AD. Previous work, due to insufficient sample sizes, could only focus on individual genes. A major challenge in advancing research is how to define different cognitive resilience groups, significantly reducing the number of participants available for analysis [17, 18]. In recent years, the residual method for quantifying “resilience” measures has become a potential phenotype for genetic analysis. Summarizing the genetic analysis results of cognitive resilience quantified through the residual method can provide insights into the genetic architecture of AD and potential therapeutic targets [19]. Currently, the main focus of drug treatment for AD is symptom relief to limit the progression of cognitive impairments and psychological symptoms of dementia. Anti-cholinesterase inhibitors and anti-glutamatergic drugs have been approved for marketing [20, 21]. These medications are administered orally or transdermally. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are molecules that increase acetylcholine levels in the brain, a neurotransmitter crucial for memory. Anti-glutamatergic agents can modulate glutamate levels by acting as non-competitive antagonists of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor. Glutamate is also a neurotransmitter involved in learning and memory functions in the brain [22]. These medications may be more beneficial in the early asymptomatic stages before neurodegenerative changes occur. Therefore, measuring cognitive resilience can aid in identifying groups with a potentially faster progression of dementia, enabling timely interventions to prevent further deterioration. Although current research has provided some insight into the genetic mechanisms and imaging characteristics of resilience, there are still several relatively independent pathological factors that remain unaccounted for, necessitating further exploration.

This review begins by introducing the definition and significance of the A/T/N framework, outlining the relationships between the three modalities of imaging. Subsequently, it summarizes the concept of cognitive resilience and its impact on the progression of AD. It elaborates on how to measure or quantify cognitive resilience using the residual method, highlighting the benefits of quantifying cognitive resilience compared to other features. Then, the latest research is summarized, elucidating how the residual method is employed to describe changes among the A/T/N dimensions and subsequently predict future cognitive trajectory changes in patients. In addition to integrating the aforementioned pathological information, this paper discusses, from the perspective of brain networks, the mechanisms that sustain cognitive resilience and how various network metric parameters can be utilized to measure brain resilience in the context of AD. Finally, we discuss the molecular mechanisms of cognitive resilience in the brain, summarizing the genetic loci and their polymorphisms that influence cognitive resilience, providing a reference for subsequent research and the development of treatment targets.

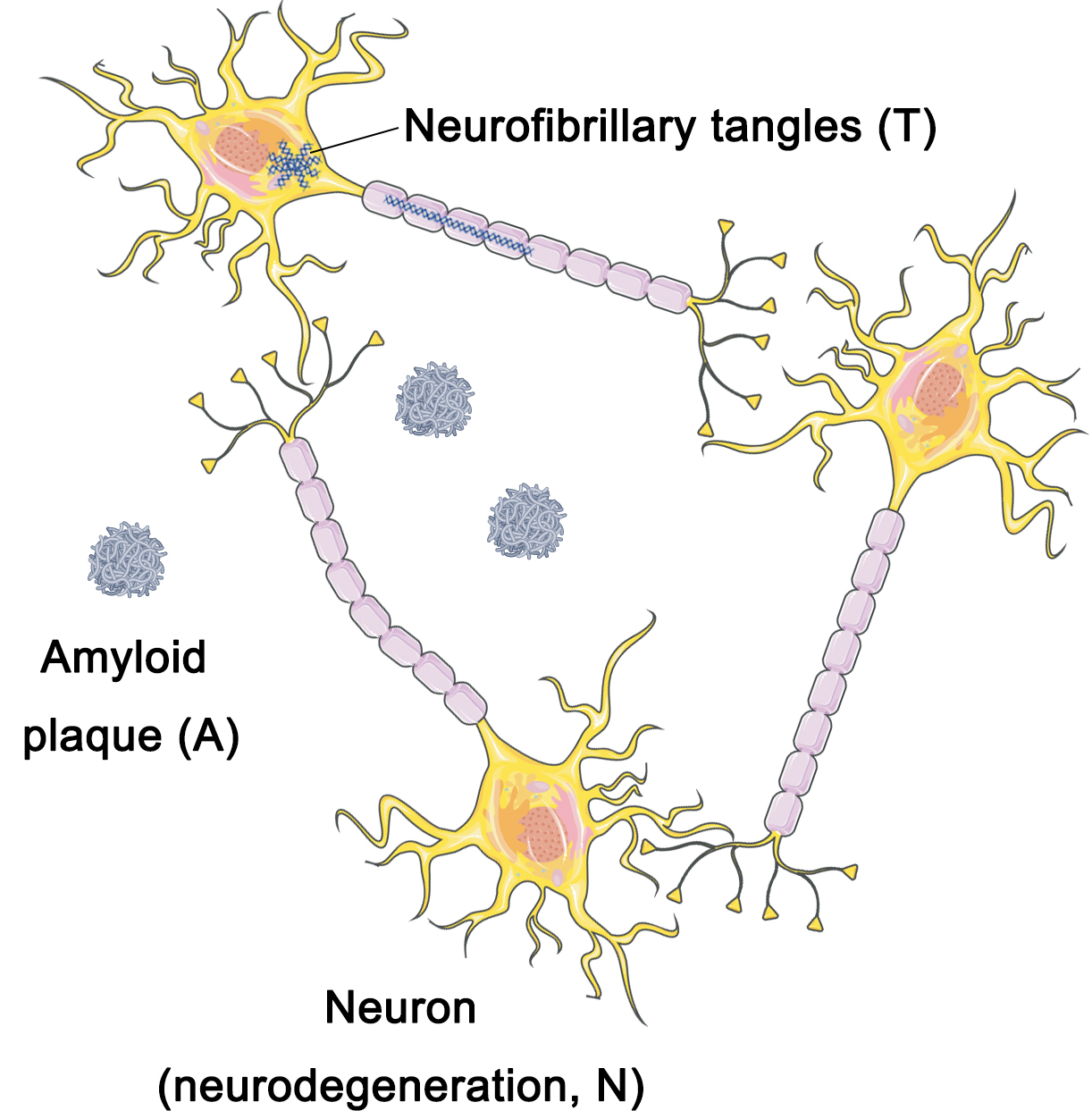

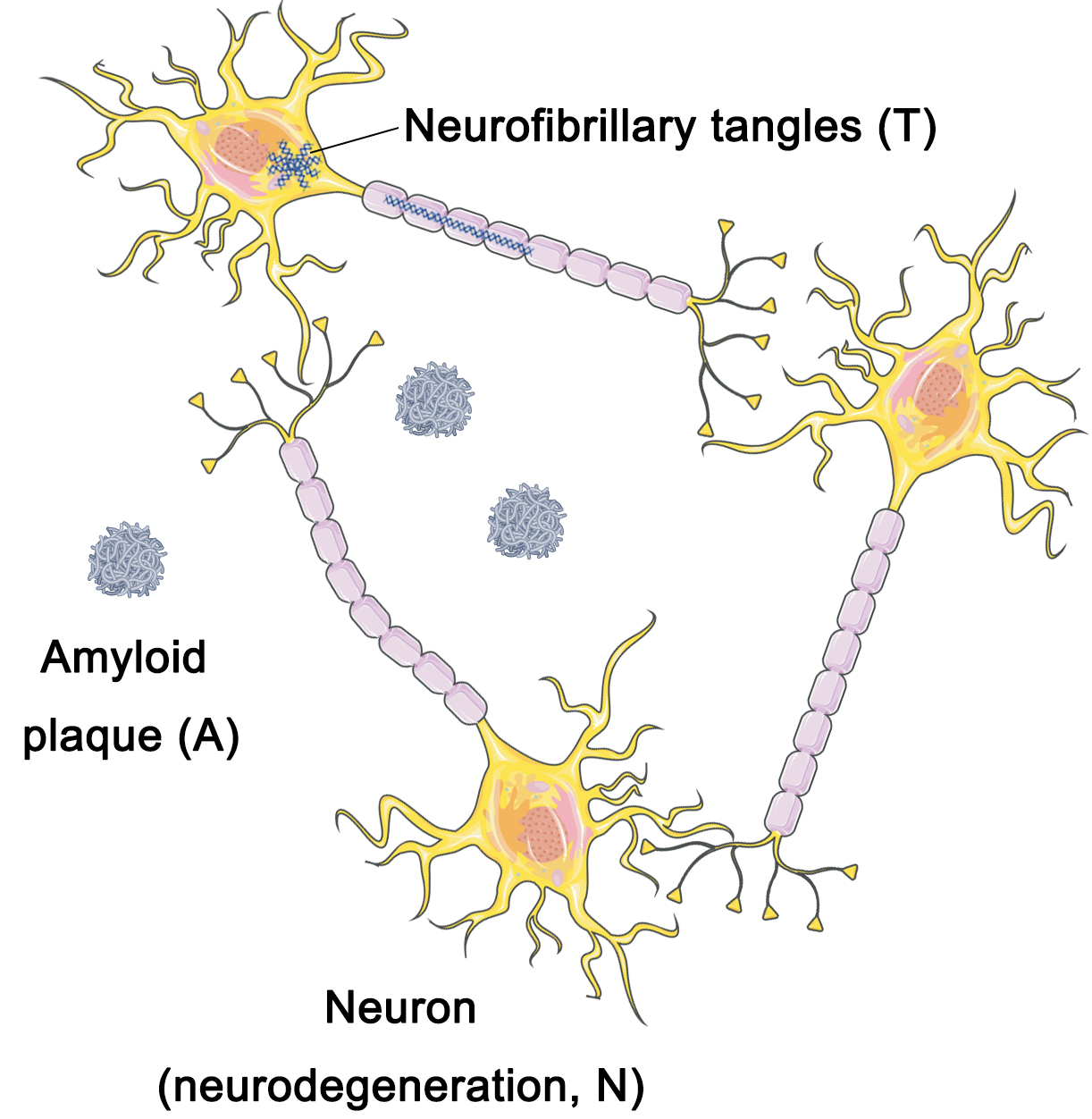

Researchers have suggested that the standardization of the AD framework must primarily rely on neuropathological data rather than clinical information in order to capture the underlying molecular mechanisms of the disease [23]. In 2018, the NIA-AA Working Group recommended that the criteria framework for AD be most aptly applied in the context of investigational research on the disease as opposed to serving as diagnostic criteria [7]. The implementation of this framework holds crucial significance in devising and implementing observational cohort studies as well as interventional clinical trials [7]. The working group partitioned the criteria framework into distinct dimensions, namely amyloid deposition (A), neurofibrillary tangles (T), and neurodegenerative lesions (N) [10] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A/T/N framework. The A/T/N framework model divides Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology into three dimensions: amyloid deposition (A), neurofibrillary tangles (T), and neurodegenerative lesions (N). A/T/N, amyloid deposition, Tau, and neurodegeneration (cortical atrophy or metabolism). Figure was created using Adobe Photoshop (2018 19.1.9, Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Among the major characteristics of brain imaging analysis are neurodegenerative lesions (cortical atrophy and hypometabolism), amyloid plaques, and Tau burdens. Due to the alterations in neuroanatomy induced by AD, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has gained widespread use for the evaluation of cognitive decline and the differential diagnosis of dementia owing to its superior spatial resolution and structural attributes. AD diagnosis can achieve increased precision by utilizing MRI to evaluate gray matter volumes in specific regions of interest (ROIs), including the hippocampus, middle temporal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, amygdala, parahippocampus, internal olfactory cortex, subparietal, precuneus, and thalamus [24, 25]. These regions are more susceptible to atrophy [26]. Positron emission tomography (PET) images of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) serve as a biomarker that gauges the level of neuronal activity, enabling differentiation between cognitively stable, healthy older adults and those who experience progressive decline to mild cognitive impairment [27]. An alternative study has scrutinized the impacts of aging on cerebral glucose metabolism and carried out a longitudinal evaluation among elderly people with normal cognition. The findings evinced a reduction in 18F-FDG absorption within the anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate/precuneus, and lateral parietal cortex. However, the subjects did not manifest any cognitive impairment, and no direct correlation was found between the metabolic decrease and cognitive deterioration [28].

In addition to the previously mentioned neurodegenerative biomarkers, the correlation between hypometabolism and amyloid deposition can serve as evidence of disrupted neuronal function and synaptic activity [29]. Elevated levels of amyloid plaques and relatively augmented glucose metabolism were observed in the cognitively normal elderly cohort [29]. Comparable findings were reported in another investigation where participants exhibited diminished cerebral glucose metabolism in a region of interest without conspicuous amyloid deposition [30]. Aside from amyloid, the gradual dissemination and age-related upsurge of Tau aggregation in healthy elderly individuals is correlated with the deterioration of memory function [31, 32]. The presence of amyloid in cognitively normal individuals is a robust predictor of Tau protein accumulation [33]. The co-occurrence of amyloid and Tau protein deposition appears to escalate Tau pathology, particularly in subjects with mild cognitive impairment or AD dementia [34], where an inverse relationship between cognitive performance and elevated Tau deposition has been demonstrated [35, 36]. Tau PET has become an effective tool for predicting cognitive changes in individuals [37].

A framework of this nature could potentially resolve the challenge that numerous individuals may have comorbid pathological conditions that, if detected and incorporated, could advance the development of more accurate biological characterizations of cognitive or behavioral conditions. The framework serves as a universal vocabulary that enables researchers to investigate the hypothesis of interactions between diverse pathologies represented by biomarkers in the progression of AD. We support the notion that such a framework has the capacity to scrutinize the correlation between biomarkers and cognitive deterioration linked to AD, as well as the heterogeneity of dementia. Extension and authentication in assorted populations might facilitate research in precision medicine and the formulation of individualized research protocols for particular demographics. In a recent study, the A/T/N framework was applied to the Argentine AD Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort. The objective of the study was to explicate the A/T/N framework in the ADNI cohort and to prognosticate the likelihood of participant conversion to dementia. The observations indicate that individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) who have A+/T+/N+ or MCI patients with A–/T–/N+ will experience the onset of dementia in a short duration. Investigations tailored to specific populations can supplement and contrast the findings obtained in developed nations and provide a more comprehensive understanding of this condition [12].

Numerous recent studies have noted the heterogeneity in both cognitive decline and brain function, highlighting the existence of individuals with varying degrees of susceptibility to age-related or neurodegenerative pathological alterations. Such studies suggest that some individuals demonstrate better preservation of cognitive function than expected, while others exhibit cognitive impairment beyond anticipated levels. Several theoretical frameworks and conjectures, such as cognitive/brain reserve, neural compensation, and brain maintenance, have been posited to elucidate the variegated concepts and hypotheses concerning the disparities in cognitive trajectories among individuals [38, 39]. There has been recent research that proposes a framework that summarizes the above phenomena as resistance and resilience [40, 41]. Cognitive resilience refers to the brain’s ability to maintain cognitive function (cognitive resilience) in the face of accumulated aging and neurodegenerative changes when confronted with significant neuropathology. Resistance is defined as the brain’s ability to maintain structural integrity in response to age-related aging and pathological changes. Cognitive resilience primarily describes the preservation of individual macro-level learning, memory, and analytical abilities, while brain resistance focuses on maintaining the integrity of brain structures. These two concepts describe individual brain functions on different scales [9].

A consensus on the optimal definition and measurement of resistance and resilience to brain and cognitive aging has yet to be reached. However, a novel approach known as the residual method, which involves statistical analysis of residuals via regression analysis, has been introduced. Residual measurement is based on statistical models that correlate predicted brain state variables (such as gray matter volume or Tau protein accumulation) with participant-specific features (such as age or cognition). Typically, resistance is assessed through the identification of an incongruity between dementia risk factors and brain integrity. Resilience is identified by the presence of a mismatch between cognitive ability and aging/neuropathologic changes. The derivation of residuals is obtained by employing regression models to investigate brain state variables and individual characteristics. These residuals denote the disparities between individual observations and the anticipated outcomes of the overall regression model. In consequence, the degree of positive or negative deviation between observed outcomes and normative values can be quantified, and individuals who exhibit outcomes that surpass expectations are deemed to have resilience or resistance [9]. Regarding the issue of the adaptability of residual models, existing studies have also proposed some solutions. A study has derived measures of resilience unrelated to education, capturing cognitive resilience beyond education-related aspects [42]. Similarly, researchers have measured cognitive resilience while controlling for apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype, thereby isolating cognitive resilience independent of this genetic component [43]. Therefore, for other types of covariates, the above-mentioned method can be referenced to eliminate potentially influential factors and enhance the adaptability of the residual method. The combination of the A/T/N framework and the residual method is also intended to directly investigate potential regulatory factors affecting cognitive resilience through the heterogeneity among multidimensional pathologies in the brain, which can to some extent mitigate the impact of covariates.

There are three main models in the residual method. Age-based residuals refer to models that use variables reflecting brain state or aging to estimate the apparent age of an individual. A canonical aging model is constructed for healthy individuals and subsequently applied to new individuals, with residual measures calculated as the difference between the actual and predicted ages. These residuals capture the extent of deviation of the individual from the population norm and quantify the maintenance of brain integrity in the presence of aging. Different biomarkers, whole brain voxel maps of gray [44, 45, 46] or white matter [47, 48, 49], or regional cortical thickness [50, 51, 52] or surface area [53, 54, 55] can represent brain integrity. Conversely, brain state can also be predicted by age, as evidenced by a study that utilized structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging data and subjected them to regression analysis with actual age as the predictor variable [56]. To estimate cognitive ability and quantify the disparity between predicted and actual cognitive function, measurements of brain pathology or structure can be utilized, providing insights into cognitive resilience or vulnerability. Deviations from individual and group regression models may be calculated to capture resilience. Among the initial models put forward was the memory residual model, which defines cognitive resilience as positive or negative residuals based on memory performance [57]. Likewise, cognitive resilience can be captured by structural MRI data, with commonly used brain metrics being whole brain gray matter volume, hippocampal volume, and white matter hyperintensities [58, 59, 60]. Numerous analogous investigations have correlated cognitive abilities with neuropathological markers [61, 62]. An alternative promising avenue is the application of somatic biomarkers of AD pathology [63, 64]. In addition, there are inquiries into a multimodal approach that integrates brain structure and neuropathology to predict cognitive ability [42]. In summary, the residual method shows promise as a tool for gauging brain resilience. Residuals can be computed using various methods. Enhanced resistance and resilience are correlated with a reduced risk of clinical disease progression. These findings imply that residual measures account for divergences in brain and aging courses across individuals.

In clinical research and applications, the use of the residual method conveniently facilitates the study of determinants and mechanisms of aging, aiding in the advancement of early intervention measures for cognitive impairment. This, in turn, enhances resilience and resistance capabilities. Similarly, the level of resilience in participants enables a more personalized prognosis assessment of clinical treatment outcomes (e.g., the risk of developing dementia) [64]. By utilizing cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers from patients with cognitive impairment, robust resilience indicators can be defined to predict slower rates of cognitive decline. These resilience indicators are defined by the residuals from linear regression models that correlate brain aging outcomes (hippocampal volume and cognitive scores) with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers (Tau, Amyloid). Positive residuals indicate outcomes that exceed expectations at given pathological levels (high resilience), allowing this metric to be used clinically to predict the risk of disease conversion. Moreover, the value of resilience measurement in prognosis assessment suggests its potential role in patient management and cohort selection for clinical drug trials. Despite some limitations, the use of the residual method is increasing because it offers unique advantages over established biomarkers. Residual methods provide a direct and objective way to quantify individual heterogeneity, offering a specific numerical value reflecting its magnitude. This is a more efficient approach, as continuous phenotypes are superior to discretely grouping patients based on thresholds, providing a more accurate reflection of the dynamic nature of cognitive resilience. With disease progression, nonlinear changes in brain resilience occur, and the residual method can capture these patterns, thereby capturing clinical information relevant to future changes in cognitive abilities.

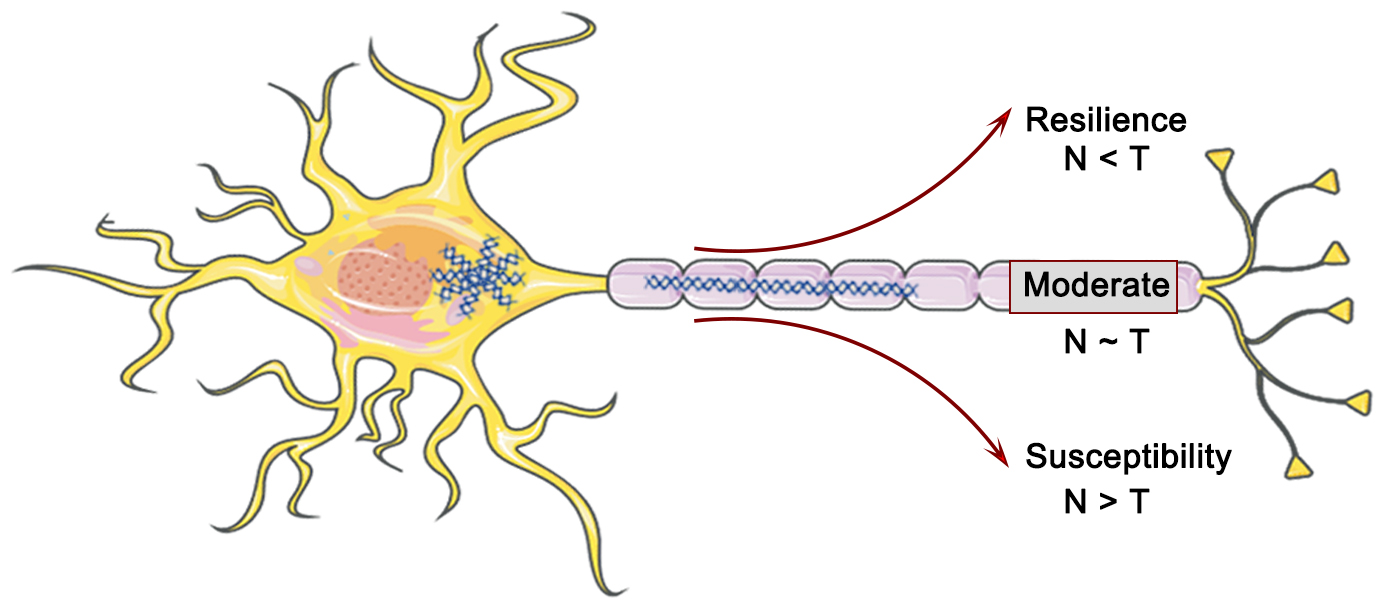

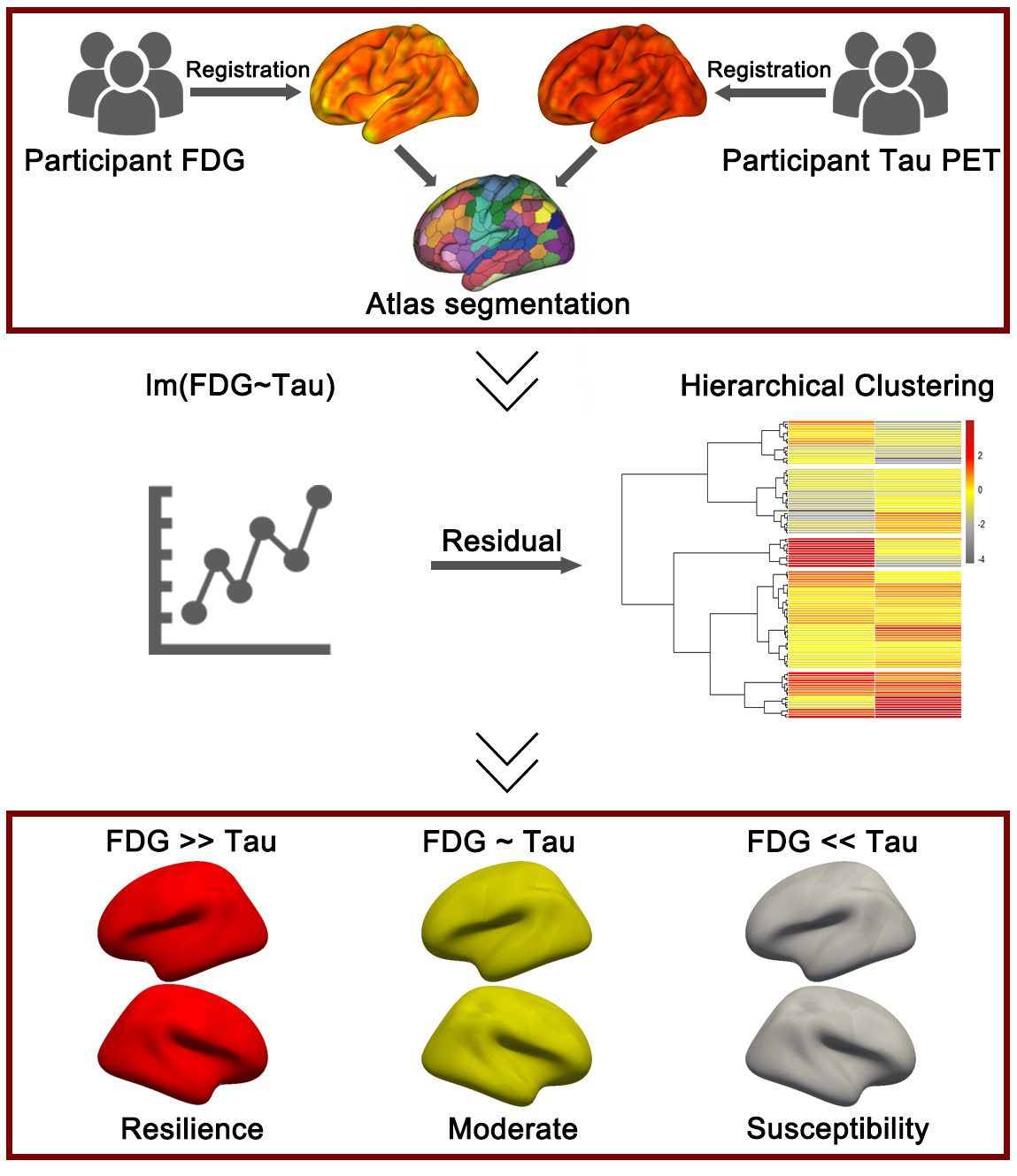

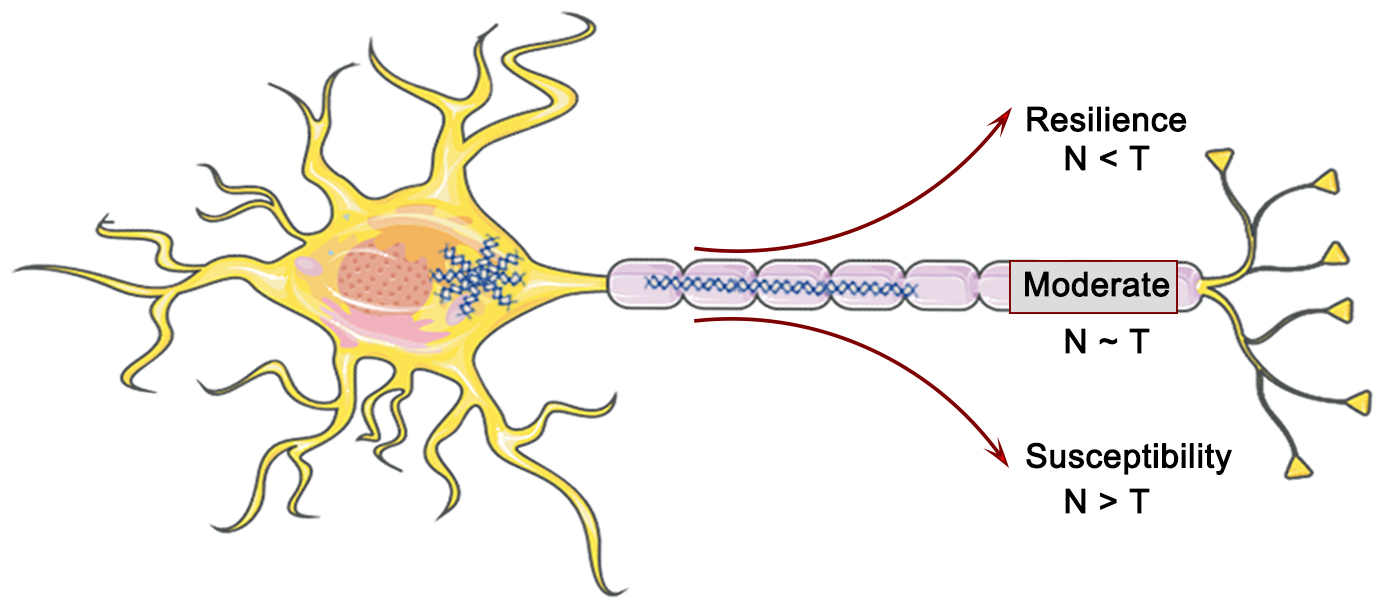

The residual method represents a valuable means to investigate the variability of individual cognitive trajectories and dementia progression. Meanwhile, the A/T/N framework has emerged as a recent and powerful approach that not only captures AD pathology but also incorporates the complexities of individual comorbidities and neuropathologies. The convergence of both pathways is expected to facilitate the development of more precise and robust biomarkers. Tau neurofibrillary tangles (T or NFT) are considered a crucial factor in driving neurodegenerative lesions (N) and associated cognitive impairment in the dementia process (Fig. 2). Nonetheless, the relationship between T and N exhibits substantial variability, with varying Tau levels in a given brain region compared to the expected cortical atrophy. This heterogeneity offers the possibility of identifying possible modifying factors or co-morbid pathologies. In this regard, cortical thickness (N) and 18F-Flortaucipir SUVR (T) were computed for each gray matter region of a cohort comprising cognitively impaired and amyloid-positive individuals, with the aim of establishing region-specific residuals for a robust linear fit between the T and N (Fig. 2). The residuals were then employed to define the T-N mismatch relationship [65] (Fig. 3). Hence, the A/T/N framework postulates that the absence of Tau neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in neurodegenerative lesions indicates the existence of underlying non-AD pathology, irrespective of the amyloid presence or absence [66, 67]. Residual measures between Tau burden in individual brain regions and neurodegenerative lesions along the AD continuum possess the capability to encapsulate the heterogeneous pathology resulting from multiple underlying factors, in addition to facilitating the identification of factors beyond Tau proteins that potentially contribute to cognitive impairment (Fig. 3). These residual measures are of considerable value in selecting cohorts for clinical trials [65]. Additionally, the utilization of data-driven clustering based on the spatial patterns of T-N mismatch indicators results in the identification of diverse groups, thereby offering valuable insights into the existence of varied underlying pathologies or brain resilience. Numerous investigations have indicated that the T-N mismatch relationship is significantly linked to two potential factors that could serve as drivers of cortical atrophy outside the ambit of AD-related pathology: age [68] and cerebrovascular disease [69, 70], respectively. A greater magnitude of cortical atrophy than anticipated was observed in individuals with a specific Tau protein concentration and was found to be associated with poorer cognitive performance. Conversely, a lesser degree of cortical atrophy was associated with superior cognitive performance at the same level of Tau protein accumulation. These investigations substantiate the notion that, in the context of a nonlinear association with neurodegenerative lesions, residual measurement remains unaffected by disease severity.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The interaction between Tau (T) and neurodegeneration (N) in AD pathology and their impact on cognitive resilience. Figure was created using Adobe Photoshop (2018 19.1.9, Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

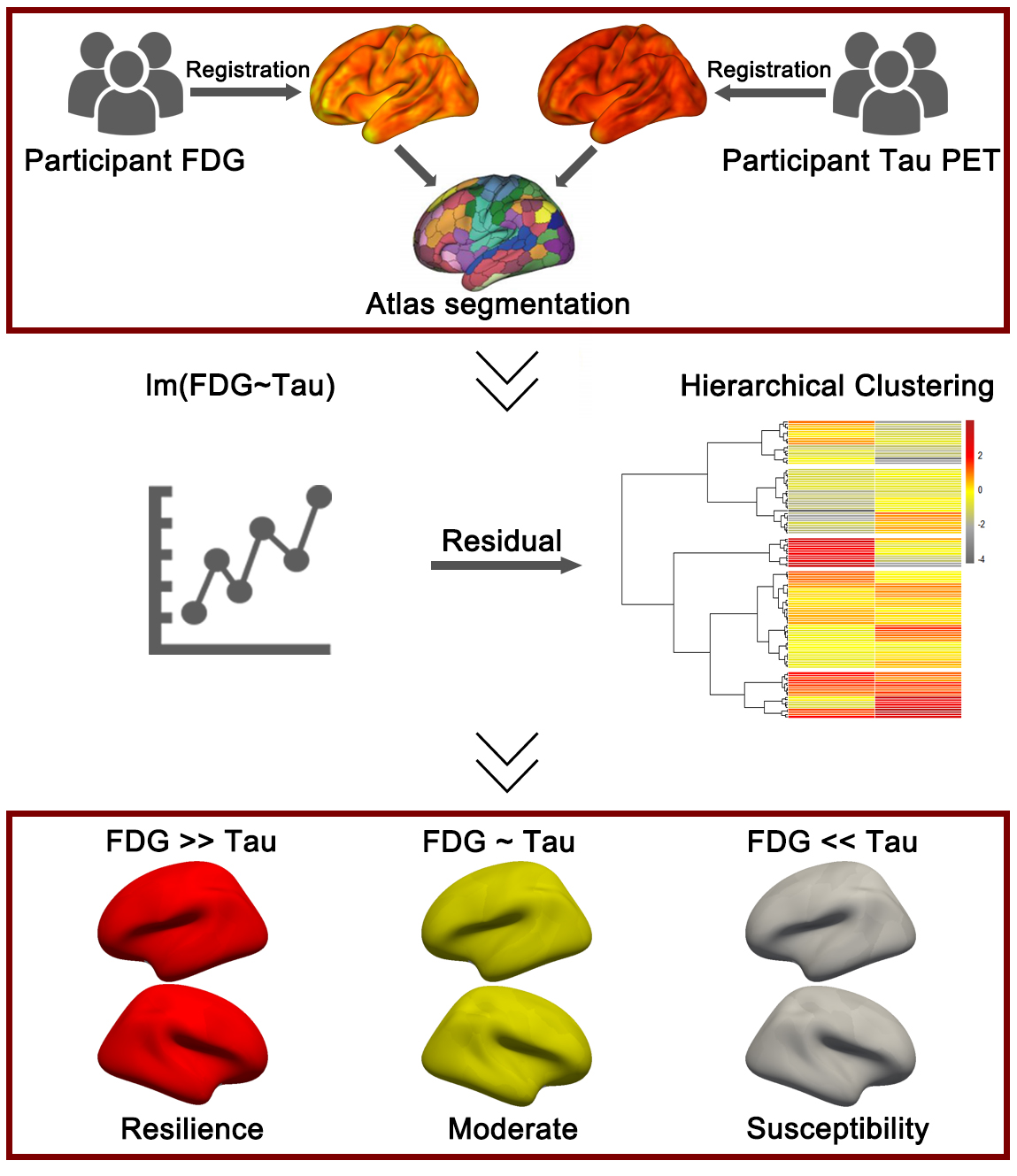

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The application of the residual method in the A/T/N framework. First, the participants’ fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) and Tau PET images were registered to the corresponding structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images, followed by segmentation based on a specific brain atlas. In the second step, a linear regression model was constructed between FDG and (Tubulin associated unit) Tau, and the model residuals (representing the mismatch between FDG and Tau) were input into an unsupervised clustering algorithm to compute different cognitive resilience groups. Figure was created using Adobe Photoshop (2018 19.1.9, Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Assessment of neurodegenerative lesions can also be achieved through the evaluation of neuronal hypometabolism (NM) based on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) [71]. Extensive research supports the spatial and quantitative correlation between Tau protein (T) and NM [72, 73, 74]. At a given level of T, patients with lower or higher levels of NM experience a dissociation between T and NM. Measuring the degree of T/NM mismatch may provide valuable insights into the resilience and susceptibility of neuronal metabolism to Tau pathology [71]. Remarkably, the T/NM cohort displayed notable differences in cortical atrophy (NS). Given the interconnectedness of NS and NM, it is plausible to anticipate interrelationships between the T/NS and T/NM associations. Employing clustering methods based on the T/NS methodology produces groups that are relatively robust or vulnerable to T. In contrast, T/NM discrepancies may furnish exclusive insights. For example, neuronal metabolism may be more responsive to Lewy body pathology [75, 76]. Moreover, metabolism may signify the functional reserve of neurons and the strength of synaptic activity that are not captured by structural markers, while structure may be less susceptible to non-dementia-related pathology than metabolism. Therefore, T/NS and T/NM disparities may complement each other, furnishing unique attributes.

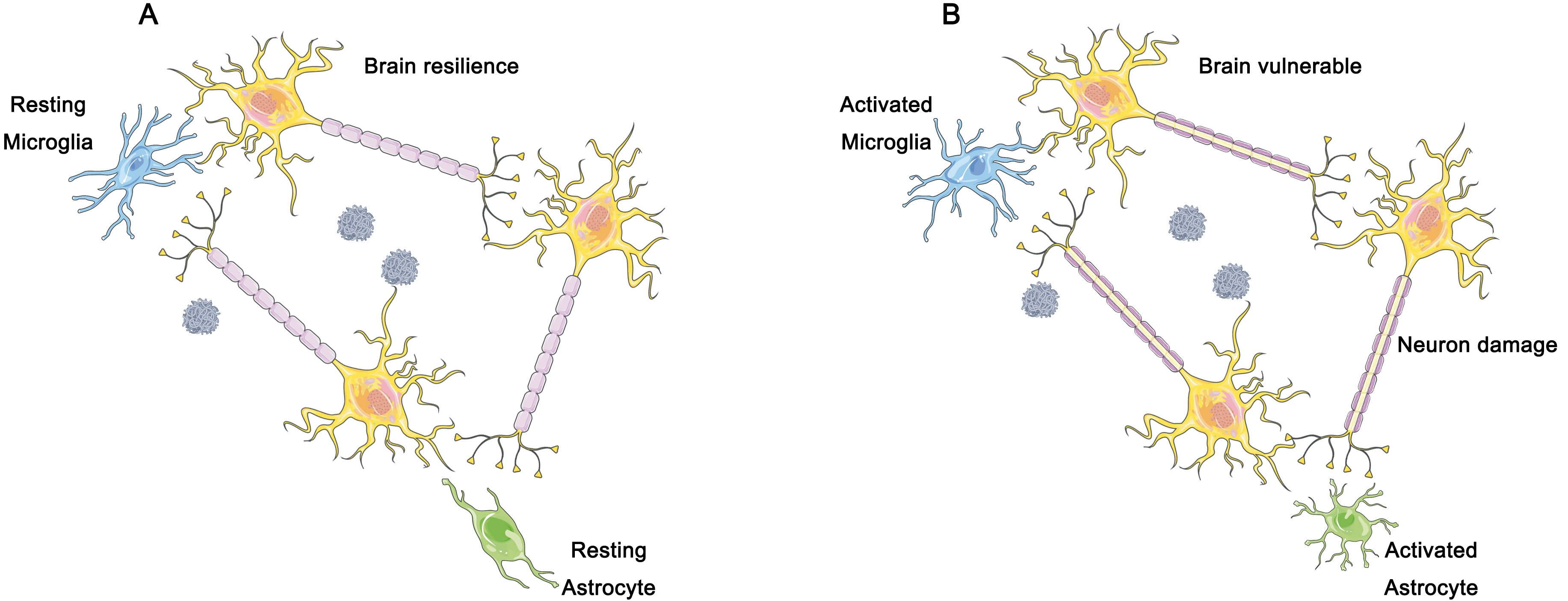

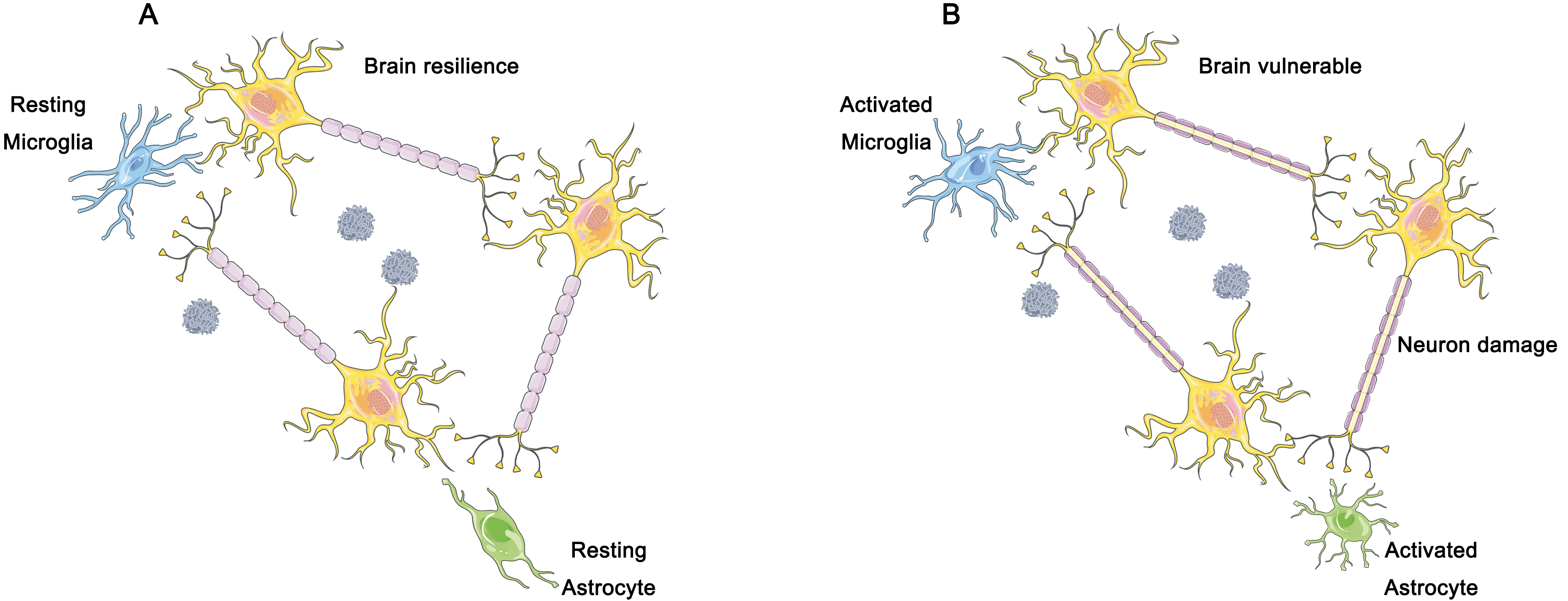

Furthermore, we believe that the immune response of the brain should be considered as part of the A/T/N framework, in addition to the three dimensions involved (Fig. 4). The accumulation of toxic proteins activates microglia, which in turn results in an elevated metabolism and changes in 18F-FDG standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) that may interfere with previous diagnostic methods [77] (Fig. 4). Fig. 4A represents the resting state of glial cells, corresponding to a better cognitive resilience condition. Fig. 4B represents the activated state of glial cells, which may cause neuronal damage and subsequently lead to a decline in cognitive resilience. According to previous studies, the amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (ALFF) is sensitive to the intensity of neuronal activity, and can serve as a valuable indicator of synaptic activity, and is incorporated into the A/T/N framework [78, 79].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The hypothesized role of microglia and astrocytes in brain resilience. (A) In individuals demonstrating cognitive resilience, a dampened inflammatory response has been observed, which is closely linked to the preservation of neurons and synapses in the face of the accumulation of plaques and tangles of nerve fibers. Such distinctive reactions to the gradual accumulation of plaques and nerve fiber tangles may underlie significant clinical variances. (B) In individuals exhibiting clinical manifestations of AD, the gradual accumulation of soluble hyperphosphorylated Tau protein and amyloid plaque triggers the activation of microglia and astrocytes. With time, the resulting excessive activation of microglia leads to brain tissue damage, including neuronal cell death and synaptic loss. Figure was created using Adobe Photoshop (2018 19.1.9, Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

T and N biomarkers provide information on both continuous and spatial changes.

Considering the distinct sites of neurodegenerative alterations in these

diseases, such inconsistent spatial patterns may support different underlying

neuropathologies. Anterior temporal lobe atrophy is greater than expected for the

local neurofibrillary tangle pathology, suggesting potential coexistence with

limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 (transactive response DNA-binding protein

of 43 kDa) encephalopathy (LATE). Participants with cognitive resilience exhibit

a lower frequency of TDP-43 pathology compared to cognitively vulnerable groups

[80]. The mismatches between T and N and the TDP-43 pathology biomarkers are

consistent. Furthermore, fewer neurodegenerative alterations than expected for a

given degree of Tau pathology may indicate resilience or cognitive reserve

against AD pathology. The situation where NM

Despite the numerous advantages of the A/T/N framework, the comorbidity between amnestic and non-amnestic variants of AD may lead to misdiagnosis within the A/T/N framework [11]. The clinical manifestation of most AD patients is amnestic AD, which is the most common form of dementia characterized by severe loss of episodic memory. One possible reason for misdiagnosis is that the widely used AD pathology may be more likely to capture the features of amnesia. However, there are several non-amnestic variants of AD that present with visual-spatial, language, or executive function impairments. Patients with non-amnestic AD may phenotypically resemble another neurodegenerative disease called frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [82, 83, 84]. The A/T/N framework may be insensitive to primary pathologies other than AD, interpreting A-/T+ or A-/N+ states as non-AD pathologies, but this is inaccurate and fails to successfully detect other neurodegenerative pathologies such as FTD [85]. Although the A/T/N framework is associated with AD and accompanying suspected non-AD pathological changes, it remains unclear whether it encompasses the majority of cases with primary non-AD pathology [86]. Considering that clinical syndromes may contribute to improving the diagnostic accuracy of the A/T/N framework for non-amnestic AD.

Furthermore, there are several factors that can affect the accuracy of the A/T/N framework. For example, the off-target effects of Tau protein contrast agents may result in some contrast agents being unable to bind to the receptors, leading to errors in Tau protein imaging. Developing a new generation of contrast agents with better affinity can address this issue.

The brain is fundamentally distinguished by disparate and intricate patterns of network connectivity that underlie its cognitive and behavioral functions. Advanced non-invasive imaging modalities have facilitated a comprehensive depiction of these patterns. Nonetheless, the issue at hand is to unravel the complex relationship between the brain network connections and their role in supporting cognitive processes, a pursuit of great significance for the personalized management of mental health and psychiatric disorders. Commonly utilized tools for the construction of operational brain networks comprise functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [87] and magnetoencephalography (MEG) [88]. Simultaneously, researchers have discerned that the functional state of the brain is not solely contingent upon the individual constituents of the brain but also upon the interplay among hundreds of neurons across brain regions [89]. Edges within a cerebral network denote the tangible links between two entities, such as synapses, which facilitate the transmission of information between neurons, and white matter bundles, which establish paths of communication between distinct brain regions [90, 91]. The arrangement of these network connections can ascertain the macroscopic traits of a system [92], and specifically, the arrangement of connections within the brain network predominantly determines the cognitive processes it facilitates [93, 94], including memory [95, 96], learning [97, 98], vision [99]. It is of utmost significance to note that the connectivity structure of the brain is profoundly heterogeneous and, as such, poses a distinctive array of challenges. Significant heterogeneity prevails among brain network modules due to the imperative need of the brain to strike a balance between a plethora of motor, energetic, and cognitive aspects of function [100]. In order to scrutinize this heterogeneity, researchers are progressively turning towards graph theory and topology, employing mathematical tools to condense copious amounts of experimental data into regular organizing principles [101, 102]. This section intends to provide an overview of certain crucial properties that are taken into account to depict brain networks. A salient aspect of the brain that has garnered significant attention is its partitioning into discrete anatomical locales that correspond to diverse cognitive functionalities [103]. In certain mammalian taxa, the macroscopic architecture of the neural network is inherently fragmented into densely interconnected clusters, which are demarcated by sparse inter-cluster connectivity [104, 105]. Notably, these highly cohesive clusters exhibit striking similarities to the established anatomical subdivisions of cerebral regions [106]. Furthermore, the cluster architecture engendered by the functional network of the brain necessitates the sustenance of an elevated level of communication efficiency among its constituent elements. The mean path length connecting all nodal pairs of a large-scale brain network is significantly shorter than that of a typical random network. However, this contradicts the characteristics of the cluster structure [107, 108]. This equilibrium between a high degree of clustering and short mean path lengths is hypothesized to enable the segregation and integration of information in the brain [109], while simultaneously minimizing the overhead required to process external stimuli [110, 111]. In a “small-world” network topology, the degree of clustering evinces a high value, whereas the average path length displays a low value. Accordingly, the brain exhibits a small-world network configuration, whereby effective information exchange ensues from a nuanced equilibrium between sub-networks and structural disorder [112]. Moreover, apart from modular clusters and small-world topologies, numerous brain networks of large scale manifest “hub systems” that give rise to a compactly interlinked core structure [113]. Functioning as connectors amidst diverse modules, these central regions are believed to mitigate the total path length of the network while expediting the incorporation of information [109]. Significant associations among seven major cerebral networks have been ascertained. The interactions amid these network modules can facilitate the comprehension of neuronal operation and dysfunctions. The central executive network (CEN) has the responsibility of electing external objectives and consolidating memories. The default mode network (DMN) acts as a reserve for the CEN and undertakes the regulation of the brain’s internal states. These two networks epitomize the cerebral internal and external states, and they collaborate with additional networks, such as the visual, sensorimotor, limbic, and attentional networks. It is the responsibility of the salience network (SN) to oversee the transition between these two control networks and to decide which network governs the brain’s state at any given moment [114, 115]. Whilst the modular and small-world topological structures, along with the central architecture of the brain networks, may offer fundamental principles for organization, the comprehensive functionality of the brain is ascertained by the continuous and dynamic interplay between these principles, resulting in a varying weighting of their contributions. There is mounting evidence that dynamic alterations in individual neurons and cerebral regions can generate noticeable configurations of distant correlations and collective activity within the brain when integrated into a network of interconnections [116, 117].

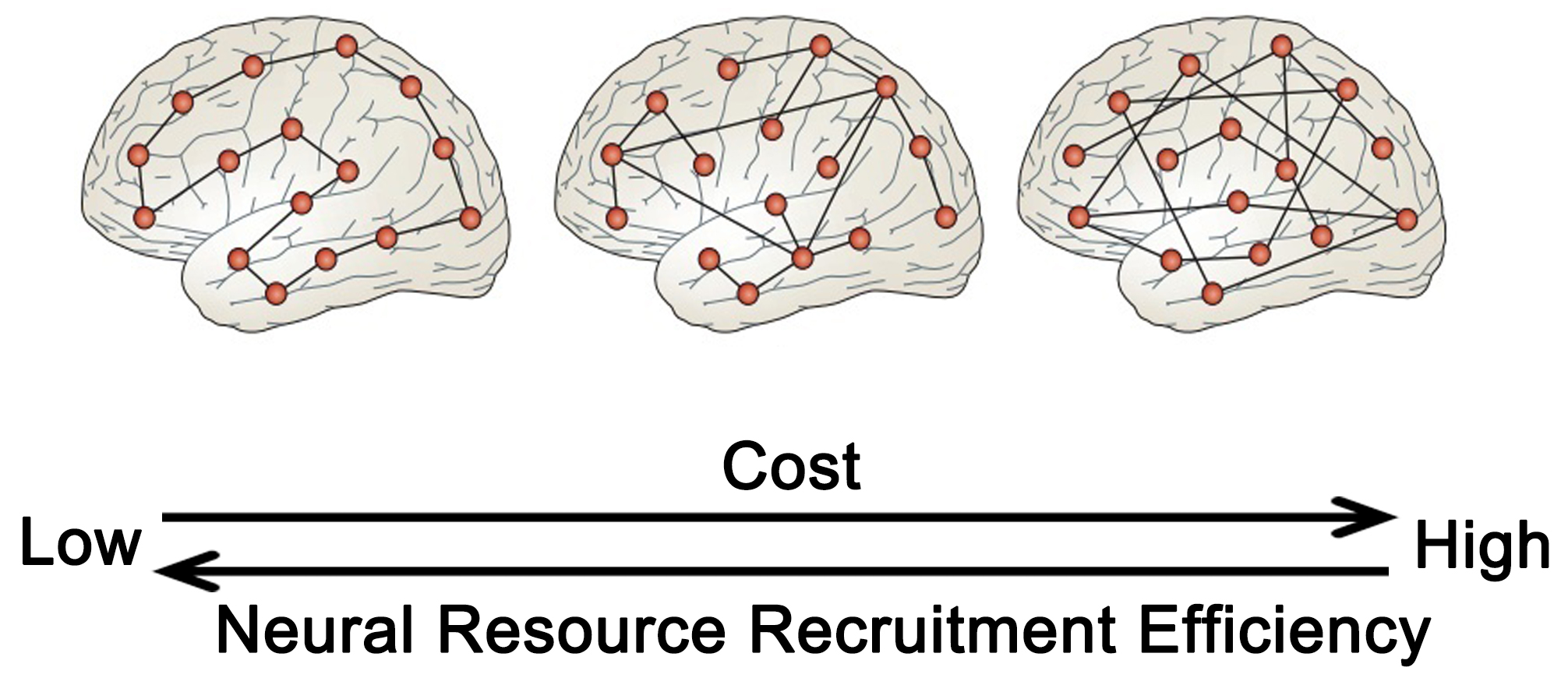

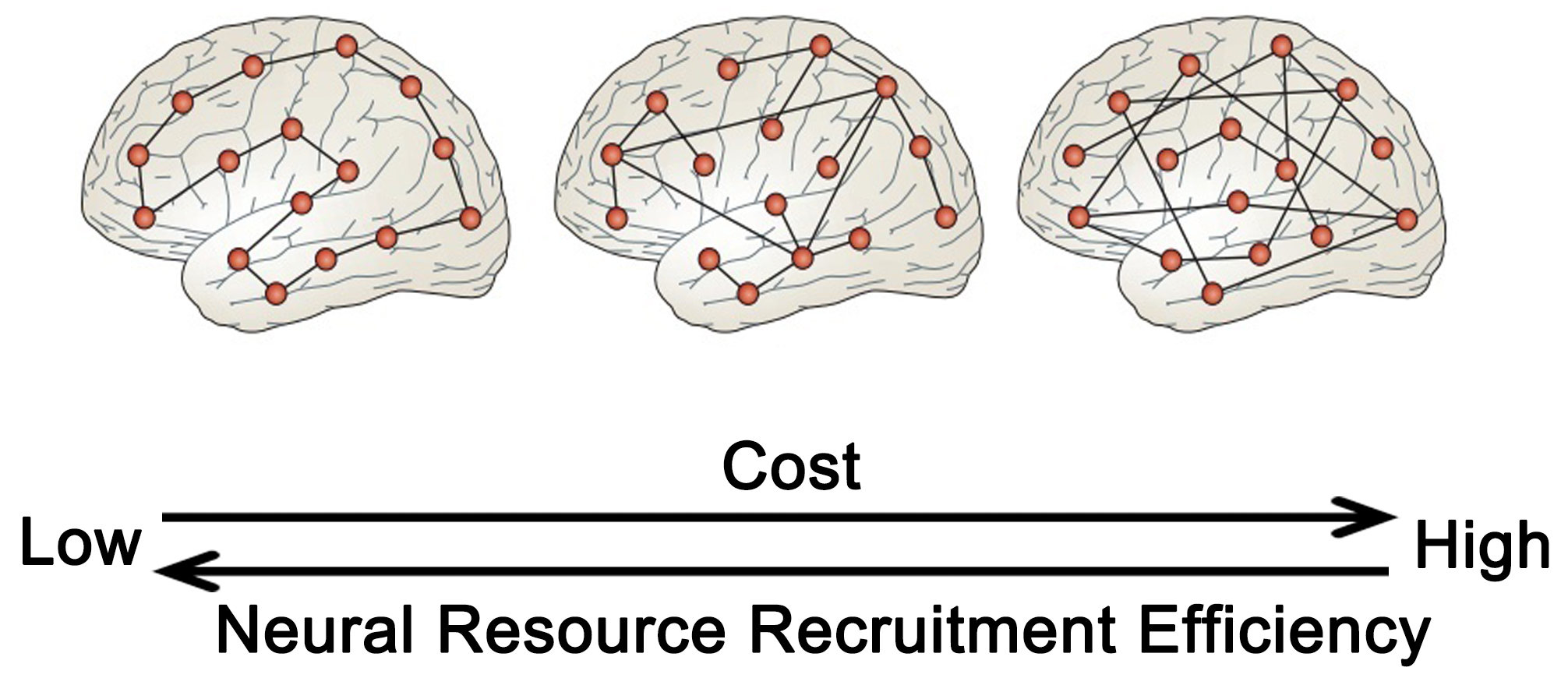

The preclinical phase of neurodegenerative conditions is characterized by structural alterations in the brain that lack significant clinical features. During the early stages of the disease, cognitive decline is influenced by cognitive resilience and compensatory mechanisms, but the functional neural mechanisms that underlie cognitive resilience are not yet fully understood. This organization is typified by a “small-world” topology with densely connected hubs that minimize the topological distance, or path length, between network modules. The path length can serve as a measure of global or regional network efficiency. Networks exhibiting efficient small-world topologies are intrinsically resistant to disruptions stemming from the removal of network nodes or connections [118, 119]. During the preclinical phase of a disease, the resilience of the brain to structural changes can be influenced by topological heterogeneity or active compensation, with some studies proposing that topology may have a greater impact. Analogous to many ecological and artificial networks, the small-world topological structure of the brain network balances the metabolic expense of long-range connections (path length) between any two points in the network with common connections between locally interconnected nodes [120] (Fig. 5, Ref. [100]).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The network structure characteristics of brain cognitive resilience. The greater the global efficiency of the brain in terms of information transmission, the more adept it is at mobilizing neuronal resources, albeit at a higher energy cost. Conversely, high connectivity between local and long-distance brain regions may strike a balance between energy expenditure and efficiency. Adapted from (Bullmore and Sporns [100]). Figure was created using Adobe Photoshop (2018 19.1.9, Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Among patients, modifications in network connectivity are consistently linked to a reduction in cognitive function [121] or a decreased reaction to treatment [122]. Conversely, the integration of network structures confers resilience in the initial stages of the disease, safeguarding cognitive well-being even in the presence of established neuropathology and cerebral atrophy. Specifically, preserving the effective organization of the brain’s functional network sustains cognitive ability even in the face of presymptomatic cortical atrophy and decreased network connectivity [123]. Recent investigations have revealed novel organizational structures within brain network modules. These structures demonstrate that cognitive resilience in AD is correlated with increased functional connectivity of cognitive control and salient network hubs [124, 125], as well as elevated glucose metabolism and brain activation in the anterior cingulate and temporal cortex [126, 127]. To enhance comprehension of the underlying mechanisms through which global brain functional network topology promotes cognitive resilience, an approach that utilizes resting-state fMRI to establish segregation between functional networks as a potential neural substrate for cognitive resilience is proposed [128]. The brain is comprised of network modules interlinked with each other [129, 130], each corresponding to a set of densely linked regions [131]. This modular functional organization of the brain, manifested in the form of segregated functional network modules, is a critical feature in maintaining cognitive capacity [100, 105].

The segregation of network modules quantifies the extent to which major functional networks are isolated from each other, that is, high intra-network connectivity and low inter-network connectivity [132]. Higher degrees of separation are associated with superior overall cognitive performance [133]. In individuals with brain injuries, a positive correlation has been observed between increased levels of dissociation and improved cognitive performance following rehabilitation. This finding suggests that dissociation may serve as a protective mechanism, endowing the brain with heightened cognitive resilience to mitigate the effects of neuropathology [14]. Other fMRI imaging studies have demonstrated that the recruitment of additional neuronal resources may be a compensatory mechanism for age- and AD-related pathology, with the effectiveness of such mechanisms being influenced by the underlying structural network connections [15, 16]. Furthermore, structural network efficiency (SNE) has been found to be positively correlated with intelligence across the lifespan, which is a known factor in resilience to cognitive decline. The resilience of a network arises from its robust and efficient connections among brain regions [134]. The allocation and mobilization of neuronal resources could rely on the structural integrity of brain networks that govern functional reorganization and optimize global network efficiency [135]. This implies a close relationship between global network efficiency and cognitive performance. Hence, compromised microstructural integrity of white matter provides a supplementary rationale for the constraints on cognitive resilience [136].

The preservation of network efficiency is reliant on the connectivity of particular network modules [137]. Recent research has suggested that the frontoparietal control network is of significant importance in preserving cognitive ability and mental health in patients with neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [137]. In individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), higher overall functional connectivity of the lateral frontal control network (LFC) centers of the frontoparietal control network and prolonged education were correlated [138]. Additionally, patients with a higher LFC overall connectivity showed greater cognitive resilience at the same level of dementia-induced hypometabolism [139]. A prior investigation examining task-related functional connectivity in frontoparietal regions, encompassing the LFC, revealed that frontoparietal control networks couple with networks such as the dorsal-attention network (DAN) and default-mode network (DMN) during task execution, facilitating adaptive task demands [140]. The LFC functions as a commanding entity, regulating activity in other cerebral networks (e.g., DAN and DMN) [141, 142], and robust connectivity between the LFC and both the DMN and DAN is linked to elevated memory reserve [78]. These findings imply that LFC connectivity to particular networks in a pathological context may foster cognitive resilience [78].

Nonetheless, the etiology of brain network dysfunction remains incompletely comprehended. Neuroinflammation has emerged as a pivotal factor in inciting dementia, as evidenced by recent research. While microglia actively partake in the establishment and upkeep of robust neuronal networks, their over activation can disrupt such circuits. Notably, cortical neuroinflammation and brain network disruption are concomitant with and dissociated from amyloid deposition and cortical atrophy. These observations interconnect aberrant brain connectivity and pathological processes in AD, implying a pathophysiological route from neuroinflammation to widespread brain dysfunction [143]. Drawing on previous research on neuroinflammation, it is postulated that an individual’s exaggerated immune response may culminate in neural impairment, thereby impairing cognitive performance [144]. Consequently, it is hypothesized that the mechanisms modulating an individual’s cognitive resilience are influenced by not only the network metric features of brain networks and the interconnectivity between network modules but also by the immune response resulting from microglia activation, which may also partly determine the changes in cognitive trajectories.

Nevertheless, there are some contradictory features present; individuals exhibiting cognitive resilience demonstrate a slower progression of cognitive impairment, yet once neurodegenerative symptoms manifest, they may experience a more rapid decline in cognitive abilities [145]. This may relate to the ability of some individuals to better recruit compensatory neural resources. For example, when cortical atrophy and decreased connectivity between brain regions occur prior to symptoms, maintaining the effective organization of brain functional networks can protect cognitive abilities [123]. Enhanced connectivity between the left LFC and the DAN and DMN can bolster memory reserves in individuals with MCI [78]. Functional imaging studies suggest that the recruitment of additional neural resources may be regulated by underlying network connectivity, which depends on the network efficiency of the brain. This network efficiency can, to some extent, quantify the physiological basis of cognitive resilience in the early stages of AD [134]. However, once individuals with cognitive resilience experience a decline in cognitive ability, it indicates that the additional recruited compensatory neural resources can no longer sustain brain function. At this point, individuals with cognitive resilience may lose more neurons than those with less apparent cognitive resilience, potentially leading to a faster progression of neurodegenerative changes.

The data indicate that certain individuals without significant co-occurring brain pathologies or who succumbed to non-dementia-related maladies prior to the onset of dementia symptoms manifest conspicuous amyloid and Tau accumulations in the brain, yet remain devoid of cognitive impairment [146, 147]. It is possible that this is due to the different loss of neurons and synapses. Previous research has demonstrated the preservation of synaptic integrity in the entorhinal cortex and superior frontal gyrus among aged individuals lacking dementia but possessing heightened levels of amyloid and Tau deposition, as determined through post-mortem analyses. Despite no differences in the mean number of plaques between the resilient and vulnerable groups, the former presented a significantly decreased quantity of neurofibrillary tangles in the superior frontal gyrus. Additionally, no significant loss of synapses was observed in the entorhinal cortex and superior frontal gyrus of the resilient group relative to the control cohort [148]. Notably, the results of immunoblotting assays indicate that participants in the resilient group demonstrated comparatively elevated levels of synaptophysin [148]. Similarly, clinically asymptomatic individuals with AD displayed considerable hypertrophy in neuronal cell bodies, nuclei, and nucleoli throughout the cortex and CA1 region, which could signify an early neurobiological reaction to the presence of plaques and tangles or a compensatory mechanism that impedes the onset of dementia [149, 150]. At a microscopic level, the brains of resilient individuals exhibited superior preservation of axonal trajectories and morphology, characterized by significantly fewer distorted axons proximal to amyloid plaques, straight axonal trajectories distal to plaques, and markedly reduced numbers of dystrophic axons concomitant with amyloid plaques [147]. Additionally, changes in the structure and density of dendritic spines can distinguish individuals’ capacity to resist neurodegenerative pathology. Compared to cognitively resilient individuals, those with cognitive vulnerability exhibit a significant reduction in thin spines and mushroom spines [151]. The loss of these synapses underlies cognitive decline in neurodegenerative pathology; however, neurons can compensate for this loss. Currently, two primary compensatory mechanisms have been identified: the expansion and regeneration of adjacent normal synapses. A early study has shown that following partial synapse loss, the remaining synapses expand [152]. This compensatory increase in surviving dendritic spines has also been observed in AD animal models. In P301S transgenic mice, synapse loss is accompanied by an increase in the size of the remaining dendritic spine synapses [153]. Another compensatory mechanism for synapse loss in neurodegenerative pathology is the regeneration of dendritic spines. A study has reported that dendrites close to plaques exhibit a higher rate of synaptogenesis, accompanied by an increase in the rate of synapse loss, whereas dendrites farther from plaques do not show this pattern. This may reflect a balance between pathological synaptic loss and compensatory increases in synapses, where synaptic elimination is accompanied by a significant increase in synaptogenesis [154].

These findings lend support to the notion that undisclosed underlying mechanisms and biological factors may play a more proximal role in preserving brain function and driving disease progression. This factor may exert a substantial influence on the development of future neuroimaging biomarkers that could better prognosticate clinical outcomes. In light of the presence of amyloid and Tau protein lesions in the brain, in vivo indicators of neuronal death and synaptic decline may more precisely forecast the likelihood of cognitive decline than mere quantification of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.

The mechanism underlying this phenomenon may be associated with the activation of astrocytes and microglia and is temporally and spatially linked to plaques and tangles [155, 156]. Glial cell activation commences near amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the early stages of AD and increases as the disease progresses [157]. Previous research has shown that individuals with resilient brains exhibit lower levels of inflammatory markers than those with dementia, and microglial numbers are more closely correlated with synaptic loss than with plaques and tangles [158]. In accordance with these findings, the brains of individuals exhibiting clinical symptoms of AD were characterized by a marked elevation in the number of astrocytes and microglia, compared to control participants who did not show signs of dementia-related lesions [159]. Conversely, the brains of resilient individuals exhibited a dampened neuroinflammatory response [147]. These investigations have also determined that attenuated glial activation within the brains of individuals with cognitive resilience was correlated with distinctive cytokine expression profiles within the entorhinal cortex and superior temporal sulci, which not only differed from the brains of patients with dementia but also deviated from control participants without dementia neuropathologic lesions [159]. The heterogeneity of cytokine expression profiles assumes a critical function in regulating immune responses, thereby indicating multifaceted and diverse connections between astrocytes and microglia, as well as the plausible presence of numerous “protective” cytokine signaling pathways in the adaptable brain. Despite the presence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, this signaling pathway may be capable of sustaining neuroinflammatory homeostasis and neuronal integrity, consequently impeding the advancement of dementia. The occurrence of congenital proinflammatory cytokines in the periphery has been determined to be a risk factor for dementia in middle-aged adults with a background of late-onset AD [160]. It is hoped that the identification of AD risk loci (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNP) from genes associated with innate immunity will contribute to a better understanding of the role of glial cells and immune-related mechanisms in AD, including PICALM [161], CR1 [162], TREM2 [163, 164], and CD33 [165]. Microglial involvement in synaptic pruning and synaptic activity regulation also highlights the importance of these mechanisms for understanding the pathophysiology of AD [166, 167]. In recent studies, it has been demonstrated that the macrophage stimulating 1 (MST1) gene regulates microglia activation, and its overexpression results in neuroinflammation and dementia-like behavior without affecting amyloid precipitation [168, 169]. Further investigation into single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes related to neuroinflammation could offer greater insight into the underlying mechanisms of cognitive resilience.

Approximately one-third of elderly individuals exhibit the neuropathological features characteristic of AD, while their cognitive faculties remain unaffected. Some investigations indicate that genetic factors may confer resilience, enabling these individuals to maintain their cognitive integrity despite the presence of significant neuropathology. Additionally, the genetic architecture underlying cognitive resilience appears to diverge from that of patients afflicted with clinical AD, proposing that research aimed at the genetic mechanisms of resilience might represent a novel approach to identify therapeutic targets.

In a single-variant analysis, researchers observed a genome-wide significant locus (rs2571244) in the ATP8B1 gene located upstream of chromosome 18 in participants with preserved cognitive function. This locus (rs2571244) is significantly associated with the methylation of multiple CpG sites in the prefrontal cortex tissue, suggesting methylation as a potential biological driving factor for this locus [170]. Another study supported the potential roles of UNC5C and ENC1 in regulating the susceptibility of different neurons to pathological damage [171]. Overexpression of UNC5C was associated with increased cell apoptosis and did not affect the production of amyloid-beta or Tau proteins. Increased UNC5C RNA led to poorer cognitive resilience. In addition, the rapid decline of episodic memory is associated with UNC5C rs3846455, which is consistent with the specific role of UNC5C in the hippocampus [172]. Similarly, ENC1 is associated with neuroprotection against various damages; in vitro, ENC1 is upregulated in cases of neuroinjury such as oxygen-glucose deprivation or toxic protein aggregation [173]. The ENC1 rs76662990 variant is correlated with slower cognitive decline in multiple cognitive assessments, and researchers have observed that individuals with higher levels of ENC1 RNA exhibit greater cognitive resilience and fewer depressive symptoms [174]. In the TMEM106B gene, there is an association between cognitive resilience and rs11509153. The TMEM106B haplotype captured by rs11509153 has been identified to have a protective effect against FTD with TDP-43 proteinopathy in genome-wide association analysis (GWAS) [171]. Besides, the maintenance of brain network structure is also crucial. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a multifunctional neurotrophic factor in the brain. This factor is crucial for the maintenance of neural networks as it is released after neuronal activity. Variations in the BDNF locus can regulate an individual’s susceptibility to neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive resilience related to dementia progression [175]. Based on the previous analysis, we speculate that this genetic mutation may affect the topological structure (global efficiency, small-world characteristics, etc.) of the brain network, thereby influencing the transmission of information and the allocation of neuronal resources in the brain network [176]. Key factors influencing cognitive resilience also include synaptic plasticity and the integrity of synaptic structures. The variant rs12056505 affects the expression of genes related to synaptic plasticity and hippocampal-dependent learning and memory. Under conditions of amyloid positivity, rs12056505 influences an individual’s cognitive resilience. rs12056505 is an intronic variant of MTMR7, overlapping with the 3′ untranslated region of VPS37A, near CNOT7 [177]. Another study found lower cortical DLGAP2 expression in individuals with AD. DLGAP2 is a crucial component of dendritic spines and may impact signal transmission in the brain by influencing synaptic morphology [178]. Recent studies have revealed that neuroinflammation also impacts the progression of AD. The genetic variant rs1057233 is associated with delayed onset of AD and low expression of SPI1 in macrophages. SPI1 is a critical transcription factor encoding myeloid cell development and function. The levels of this transcription factor influence the phagocytic activity of microglial cells, and lower SPI1 expression reduces the risk of AD by regulating myeloid genes [179]. Protein alterations such as TREM2, PLCG2, and ABI3, along with genes highly expressed in microglia, are correlated and enriched in an immune-related protein interaction network. These recent findings suggest that microglia-mediated innate immune responses directly accelerate the progression of AD [180].

In addition to molecular-level research, investigating associations between

multimodal imaging biomarkers and genetics will be highly valuable. Brain genomic

association analyses can be conducted at multiple levels: we may examine

candidate gene SNPs, relevant biological pathways, or the entire genome.

Similarly, in neuroimaging, we can explore single regions of interest (ROIs) or

circuits involving multiple ROIs. The relationship between APOE genotype

and structural MRI phenotypes has been well documented and validated in studies

based on the ADNI database. Patients carrying the APOE

In addition to studying associations between structural MRI imaging features and

genes, researchers have also investigated how SNPs affect functional neuroimaging

characteristics, such as fMRI and PET imaging. Researchers have found that

healthy elderly individuals carrying the APOE

The Val66Met polymorphism of the BDNF gene has a significant

effect on regional brain metabolic rates measured by FDG-PET, with Met

allele carriers showing distinct glucose metabolism differences across several

brain regions compared to non-carriers [192]. In ADNI participants, analyses of

[11C]PiB-PET imaging data revealed that individuals carrying a protective

allele of an intronic SNP within the DHCR24 gene exhibited lower amyloid

burdens at the whole-brain voxel level than non-carriers [193]. Similar results

were observed in carriers of the protective allele of the CR1 gene

rs3818361 SNP [194]. Furthermore, an interaction between CR1

and APOE was noted: among CR1 non-carriers, APOE

In summary, FDG-PET imaging can reveal the effects of SNP loci associated with glucose metabolism, while AV45-PET or PiB-PET SUVR values can reflect the functionality of genes involved in amyloid clearance. Additionally, the function of genes that regulate synapse formation, regeneration, and integrity can be captured through gray matter volume and synaptic density observed in MRI or SV2A PET imaging. Overall, multimodal imaging data provide a more intuitive representation of the impact of certain SNP mutations and abnormal gene expression, offering more compelling evidence for related research.

In addition to genetic factors, head trauma and alcohol intake are also factors contributing to neuroinflammation. It has recently been observed that ethanol can induce cell death by triggering inflammatory mediators [196]. Another study indicates that alcohol administration in mice can induce neuroinflammation and intestinal inflammation. The reduction in gut bacterial load can alleviate alcohol-related central nervous system inflammation [197]. Similarly, traumatic brain injury (TBI) elicits a complex cascade of secondary injury responses, with neuroinflammation being a crucial component [198]. Among them, hippocampal injury serves as the basis for the late complications of TBI, such as epilepsy, depression, and cognitive impairment. The mechanisms involved in hippocampal neuronal network reorganization include chronic neuroinflammation and secondary damage to neural tissue [199].

We provide an overview of the genetic characteristics that have been associated with cognitive resilience (Table 1, Ref. [170, 171, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206]).

| Author | Gene name | Chromosome | SNP | Polymorphism | Function | Data set |

| Dumitrescu L et al. [170] | ATP8B1 | 18 | rs2571244 | C |

ATPase phospholipid transporting 8B1; Methylation in prefrontal cortex tissue at multiple CpG sites (rs2571244) | A4 study/Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI)/religious orders study and rush memory and aging project (ROS/MAP)/adult changes in thought (ACT) |

| Davis EJ et al. [200] | KDM6A | X | rs12845057 | G |

Lysine demethylase 6A | hAPP (amyloid precursor protein) mice/ADNI |

| Ramanan VK et al. [177] | MTMR7/VPS37A/CNOT7 | 8 | rs12056505 | T |

Myotubularin related protein 7/VPS37A subunit of ESCRT-I/CCR4-NOT transcription complex subunit 7 | Mayo clinic study of aging (MCSA) |

| Eissman JM et al. [201] | LOC105376400 | 10 | rs827389 | A |

ncRNA | A4 Study/ADNI/ROS/MAP/ACT |

| Egan MF et al. [202]; | BDNF | 11 | rs6265 | C |

Brain derived neurotrophic factor | Clinical brain disorders branch “sibling study” of schizophrenia and included healthy controls, schizophrenic probands, and their mostly unaffected siblings |

| Chen ZY et al. [203]; | rs11030104 | A |

||||

| Lin Y et al. [204] | rs16917204 | G |

||||

| rs7103411 | C |

|||||

| rs2030324 | A |

|||||

| Pillai JA et al. [205] | TNFRSF1B | 1 | rs976881 | T |

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily member 1B | ADNI |

| Hohman TJ et al. [176] | NA | 5 | rs4866650 | A |

Tryptophan-Aspartic acid (WD) repeat domain 11 | ADNI |

| NA | 9 | rs7849530 | A |

|||

| WDR11 | 10 | rs12261764 | G |

|||

| NA | 5 | rs6887649 | G |

|||

| Huang KL et al. [179] | SPI1 | 11 | rs1057233 | G |

Spi-1 proto-oncogene | International genomics of alzheimer’s project/ADNI |

| Sims R et al. [180] | PLCG2 | 16 | rs72824905 | C |

Phospholipase C gamma 2/Abl-Interactor (ABI) family member 3/triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 | Alzheimer’s disease in a three-stage case–control study of 85,133 subjects. |

| ABI3 | 17 | rs616338 | T | |||

| TREM2 | 6 | rs143332484 | C |

|||

| Ouellette AR et al. [178]; White CC et al. [171] | Downstream DLGAP2 | 8 | rs2957061 | C |

Disk associated large protein 2 | The ROS and MAP/MayoRNaseq study/mount sinai brain bank (MSBB) study |

| NA | 3 | rs60328885 | G |

Unc-5 netrin receptor C | ||

| UNC5C | 4 | rs3846455 | C |

Ectodermal-neural cortex 1 | ||

| ENC1 (−75.32 kb) | 5 | rs76662990 | A |

Transmembrane protein 106B | ||

| TMEM106B | 7 | rs11509153 | G |

|||

| AGR2 (+99.33 kb), | 7 | rs74665712 | C |

|||

| AGR3 (+22.46 kb) | 7 | rs1029576 | G |

|||

| LOC286083 (−27.53 kb) | 8 | rs34130287 | G |

|||

| NA | 13 | rs9527561 | G |

|||

| NA | 15 | rs7402241 | T |

|||

| Sheng J et al. [206] | PGRN | 17 | rs5848 | C |

Progranulin | PubMed databases |

NA, not available.

In conclusion, a better understanding of neuroplasticity mechanisms and their effect on the brain and cognitive aging is of critical importance to the diagnosis and prediction of disease course in aging-related diseases, where the level of resilience influences the cognitive trajectory to some degree. Furthermore, resilience must be considered throughout the disease process since the evolutionary characteristics of AD biomarkers are not uniform across patients.

The residual method summarized in this study shares some similarities with normative modeling approaches; however, this article places greater emphasis on utilizing MRI and PET-imaged mesoscopic brain characteristics (such as biomacromolecules, brain structure, neural networks, and synaptic density) as independent and dependent variables. By examining the relative changes between mesoscopic variables, the study aims to deepen understanding of mechanisms that sustain cognitive resilience and thereby achieve accurate predictions of neurodegenerative disease progression. A biomarker-driven classification framework based on integrating multimodal images was recently identified by NIA-AA to capture this interindividual heterogeneity [7]. As a result of the inconsistency between A (amyloid), T (neurofibrillary tangles), and N (neurodegeneration), additional non-dementia modulators may exist, as well as relatively large N values that may indicate an earlier onset of the disease. Additionally, this spatial pattern of inconsistency may be indicative of different non-AD pathologies, detecting the most significant factor associated with neurodegenerative disease [207]. The present exigent issue to be resolved is how to optimally define and quantify the resistance and resilience of the brain and cognitive impairment, which is pivotal for evaluating the disease progression and devising individualized treatment strategies. In order to tackle this predicament, the residual method can be employed for the A/T/N framework, employing the residuals of regression models to depict the relative alterations between A/T/N and apprehend the pathological factors associated with cognitive resilience. T is the primary instigator of the neurodegenerative lesion (N) in AD and the ensuing cognitive decline. N incorporates atrophy of the cerebral cortex and hypometabolism. However, there exists a notable fluctuation in the T-N correlation, demonstrated by higher or lower Tau levels than anticipated atrophy/metabolism in a particular brain region. Past studies have recognized prospective controlling factors for cognitive resilience and co-pathology by exploiting mismatches in the T-N relationship. Additionally, a lesser degree of neurodegeneration than expected at a certain T level could signify resilience to dementia pathology [65, 71].

Notwithstanding, the extant research still exhibits some inadequacies. The A/T/N framework may disregard the impact of microglia activation on glucose metabolism in the brain. Scholars have established that microglia consume more glucose compared to astrocytes and neurons, and the activation level of microglia governs the modification of the FDG-PET (Fludeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography) signal in the mouse model of neurodegenerative disorder. In patients, the activity of microglia is correlated with FDG-PET, and its activity must be taken into account while diagnosing dementia [77]. To surmount this predicament, we suggest that the elevation in metabolism resulting from the activation of microglia will diminish the correlation between metabolism and the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations of neurons. The above-mentioned issue could be resolved by amalgamating this correlation coefficient into the A/T/N framework. Apart from the structural and PET imaging characteristics, the functional network interconnections in the brain can also serve as a partial representation of the cognitive resilience of individuals with mild cognitive impairment. The interconnections between certain brain regions or network modules facilitate the flow and recruitment of neural resources [15]. The high global network efficiency and conspicuous small world characteristics in brain networks can efficiently compensate for neuronal damage caused by dementia pathology or inflammatory responses [16]. It is imperative to incorporate neuroinflammatory biomarkers with other pathological features, as the influence of inflammatory reactions on the brain network is autonomous of other pathological factors [143]. The A/T/N framework primarily describes neuropathologies such as the accumulation of toxic proteins in the brain, neurofibrillary tangles, and metabolic abnormalities. However, during the process of neurodegeneration, compensatory mechanisms at the synaptic level are observed, notably the enlargement of surviving synapses and the regeneration of dendritic spines. Changes in synapse quantity are closely related to neurodegeneration and cognitive resilience. PET imaging of synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) has emerged as a promising biomarker for assessing synaptic density, allowing for in vivo quantification of synaptic density, and tracking the progression of cognitive impairment [208]. The introduction of SV2A PET imaging can provide additional complementary neuropathological information to the A/T/N framework, capturing individuals’ levels of cognitive resilience and synaptic compensation, thereby playing a significant role in the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Multimodal image characteristics are only one of the pivotal biomarkers for predicting dementia progression, and research on genetic characteristics and molecular mechanisms associated with cognitive resilience is also imperative. Investigating SNP loci and related genes that dictate cognitive resilience is highly efficacious for the early diagnosis and prevention of AD. Here, we can concentrate on the gene and site polymorphism related to neuroinflammation and the activity of microglia or astrocytes based on the original research. Research on cognitive resilience could provide another avenue for treatment strategies. In this respect, the amalgamation of neuroimaging technology and molecular biology is pivotal for exploring the in vivo characteristics of aging-associated processes and forestalling neurodegenerative disorders such as AD.

In addition to early diagnosis through the use of medical imaging, lifestyle improvements are also important for the prevention of AD. Nutritional management is also crucial for AD. Nutrition throughout the entire lifespan, from foetal development to old age, influences the risk of developing AD. Low birth weight and early-life growth retardation are associated with decreased cognitive abilities in adulthood. Midlife obesity is correlated with an increased risk of AD in later life. Therefore, interventions are recommended for prevention and treatment in midlife, but in old age, being overweight is associated with a reduced risk of AD, and weight loss is generally not recommended. If older adults experience unintentional weight loss or are underweight, consulting a physician is advisable. According to existing evidence, adhering to the Mediterranean diet has been shown to lower the risk of developing AD. In the Mediterranean diet, primary components include whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, and olive oil, consumed throughout the day [209].

This paper reviews the concept of cognitive resilience and its measurement methods in the brain. It explains its biological mechanisms based on neuroimaging biomarkers of cognitive resilience. These summaries can selectively explore the determining factors of brain aging and cognitive decline, deepening the understanding of neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia. This is crucial for early diagnosis and intervention in such diseases. Secondly, the quantification of cognitive resilience can assist in the selection of clinical trial cohorts, formulate more personalized trial protocols, enhance the development of dementia drugs, and provide assistance in the prognosis assessment and chronic disease management of neurodegenerative diseases. Finally, we analyze the genetic mechanisms behind cognitive resilience imaging biomarkers, summarizing SNP loci related to cognitive resilience. This is of significant importance for screening new dementia treatment targets and exploring novel therapeutic approaches.

This paper primarily summarizes multimodal imaging biomarkers and their genetic characteristics associated with cognitive resilience. It begins by reviewing the application of the residual method in cognitive resilience research, followed by an exploration of its use within the A/T/N framework to predict the rate of cognitive decline by capturing the misalignment between the three A/T/N dimensions. Additionally, this paper discusses the mechanisms underlying the formation of cognitive resilience from the perspective of brain functional networks. Finally, it examines the cellular and molecular pathways and mechanisms that sustain cognitive resilience, and summarizes relevant SNP loci. Although the misalignment between Tau pathology and neurodegenerative changes has provided direction for research on cognitive resilience, many pathological factors that influence cognitive trajectories remain uncaptured, and long-term studies are still lacking. Furthermore, the relationship between brain network metrics and cognitive resilience remains underexplored, requiring the introduction of more advanced brain network analysis methods to more accurately depict the information transfer mechanisms between brain regions. Future research could incorporate multimodal brain imaging to visualize key biomolecules in the brain, exploring the mechanisms underlying cognitive resilience from multiple dimensions and tracking these processes over longer time spans. The high-order topological evolution of dynamic brain networks constructed from time-series signals can reflect the dynamic changes in brain functional connectivity, providing more valuable insights for decoding cognitive resilience. Finally, it is crucial to focus on how to link newly discovered molecular mechanisms of neurodegenerative pathology with more macroscopic biomarkers in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the pathogenesis and patterns of neurodegenerative diseases.

JS designed and supervised the research; ZY collected data, performed analysis; QZ collected and sorted references. ZY and JS wrote and compiled the manuscript in collaboration with co-authors QZ, XZ, YS, GD, RZ, HLZ, JW, RP, and HDZ. XZ, YS, GD, RZ, HLZ, JW, RP, and HDZ participated in designing and drawing the figures and tables. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Key Project of the Natural Science Foundations of Zhejiang Province (CN) under grant No. LZ24F010007, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant No 62271177.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.