1 Department of Anesthesiology, Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University, Medical School of Nantong University, 226001 Nantong, Jiangsu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Over the past years, a number of clinical and preclinical investigations have been documented, suggesting treatment strategies and pharmaceuticals for neuropathic pain and depressive disorders, potentially beneficial in cases where these conditions are comorbid. This review lists these potential treatment options and discusses the proposed underlying mechanisms of action and their limitations, in terms of both physiotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Physiotherapy includes electroacupuncture and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy, both of which affect neuronal function by altering the physiological state of the neurons. Pharmacological treatments include tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin, ketamine, minocycline, and Chinese medicine, which alter ion channel activity, affect neurotransmitter release, and exert anti-inflammatory effects. As such, this review may help to improve future research endeavors and therapeutic options for this frequently occurring comorbidity.

Keywords

- neuropathic pain

- depression

- co-morbidity

- behavioral disorder

Chronic neuropathic pain, stemming from somatosensory system damage or disease, encompasses conditions like postherpetic neuralgia, painful nerve lesions, trigeminal neuralgia, and postamputation pain [1, 2]. This type of pain is characterized primarily by allodynia, which is pain triggered by stimuli that are not typically painful, and hyperalgesia, a heightened sensitivity to pain that results in an exaggerated response to normally painful stimuli [3]. Depression is medically classified as a mental or behavioral disorder [4]. The primary symptoms of depression include ongoing feelings of sadness, diminished interest in activities, alterations in sleep and appetite, fatigue, self-deprecation, concentration difficulties, and suicidal ideation [5]. In the event that neuropathic pain persists for a period exceeding three months, it will likely evolve into chronic pain [6]. Chronic neuropathic pain is frequently associated with mood disorders, particularly depression [7].

The precise etiology of pain and depression comorbidity remains unclear. However, recent research has identified the involvement of a monoamine neurotransmitter, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and an inflammatory factor, glutamate, and its receptor subtypes, in the origin of comorbidities. Monoamine neurotransmitters: Monoamine neurotransmitters, such as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), dopamine, and norepinephrine (NE), are key players in the nervous system [8]. According to the traditional monoamine hypothesis, depression is linked to a diminished presence of these neurotransmitters, including 5-HT and NE, within the central nervous system (CNS) [9]. The descending pain modulation system comprises three principal elements: the periaqueductal gray of the midbrain, the medial ventral reticular formation of the medulla oblongata, and the dorsal lateral pontine tegmentum [10]. Collectively, these components suppress nociceptive signals in the spinal cord’s dorsal horn through the action of neurotransmitters like 5-HT and NE. A reduction in serotonin and norepinephrine impairs the modulatory function of the descending pain system, culminating in heightened nociceptive responses [7]. BNDF: BDNF is a neurotrophic factor that plays a vital role in regulating neuroplasticity [11]. Depression undeniably reduces BDNF expression in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and other structures associated with depression [12]. Extensive studies have confirmed the crucial role of BDNF in the onset and development of pain. Specifically, Yajima et al. [13] have shown that BDNF, originating from the spinal cord, interacts with the TrkB receptor to initiate a signaling cascade. This cascade triggers the activation of protein kinase C in spinal neurons, which in turn modulates the sensitivity to pain [13]. Inflammatory factors: The relationship between inflammatory and the central nervous system is becoming more evident. Studies have demonstrated that the inflammatory reactions in the periphery can trigger both pain and depressive disorders. Consequently, pain that is induced by inflammatory reactions could have a stronger link to depression [14, 15]. Crossing the blood-brain barrier, inflammatory messengers impact regions within the brain that are associated with depression, leading to alterations in neurotransmitter synthesis, neuroendocrine activities, and neuroplasticity [14]. Glutamate and Its Receptor Subtypes: Glutamate, an indisputable key excitatory neurotransmitter within the CNS, is present in brain synapses extensively [16]. This neurotransmitter, along with its receptor subtypes—the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors—plays a role in the genesis of chronic pain and depressive conditions [17]. It is clear that increased activity of the excitatory system and a concomitant decrease in the inhibitory system in the spinal cord contribute to central nociceptive hypersensitivity and ultimately to the progression of pathological pain.

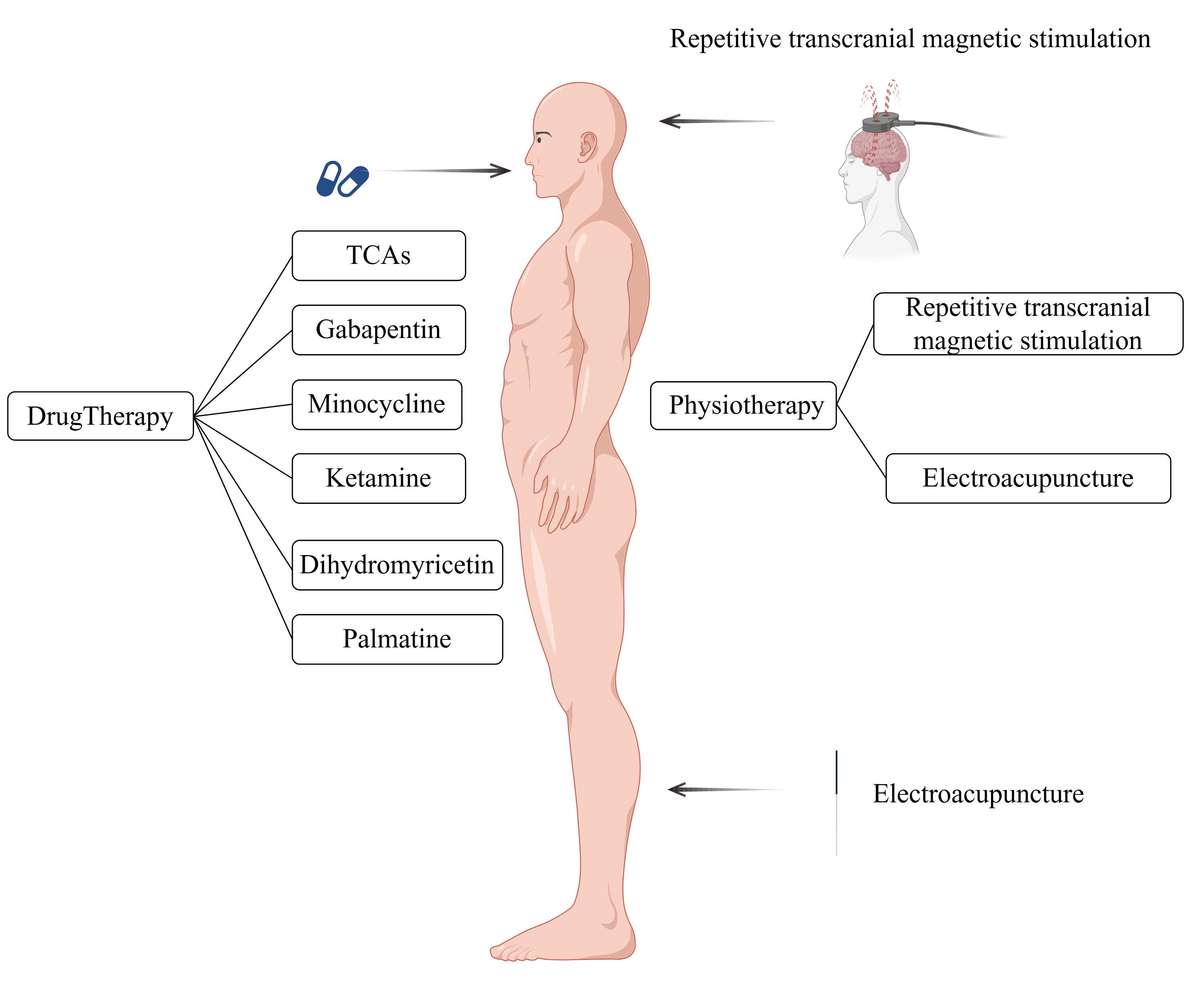

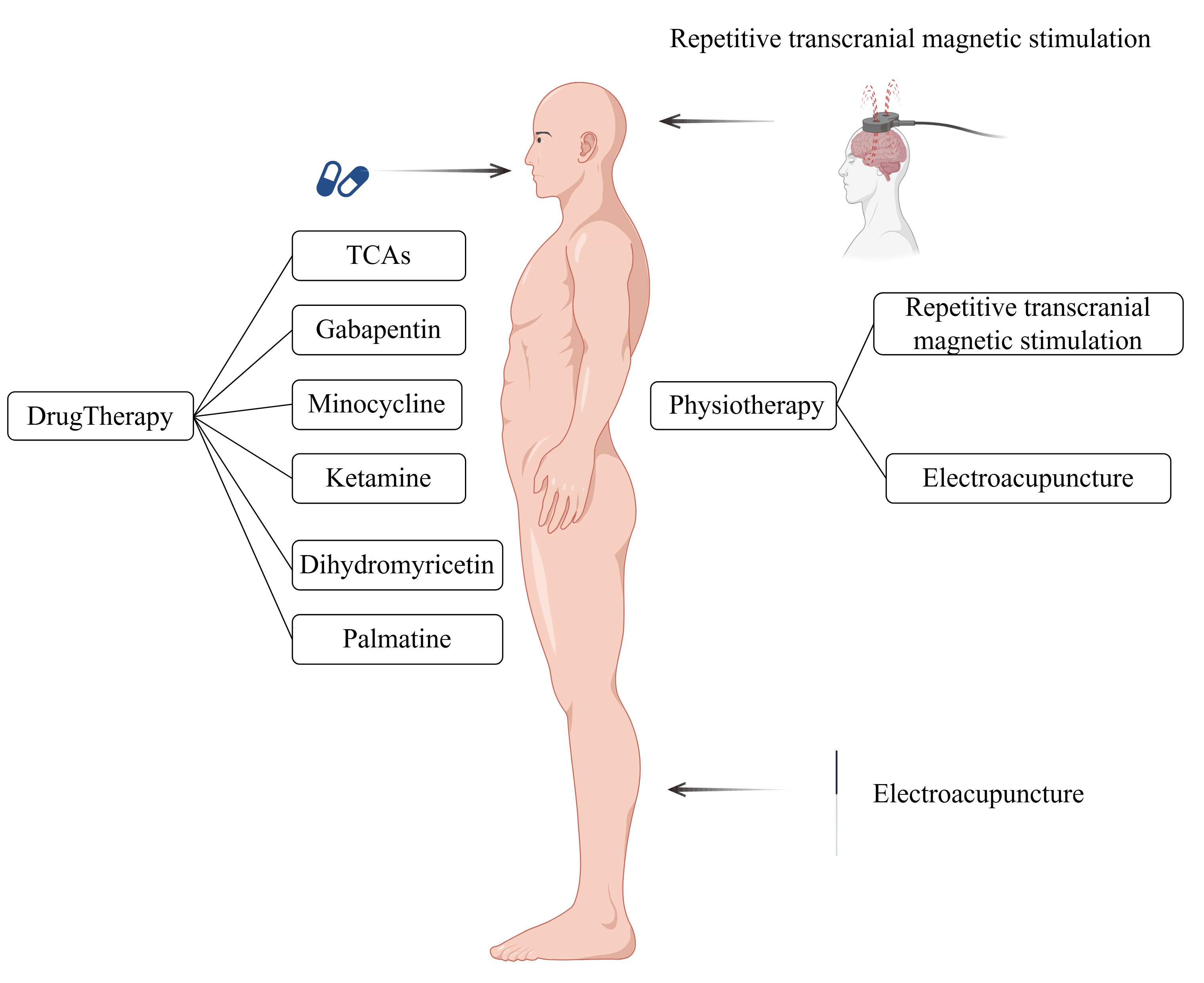

Once neuropathic pain and depression form a co-morbidity, they reinforce each other in a vicious cycle [18]. Addressing comorbid conditions presents a greater challenge compared to managing neuropathic pain or depression individually. This review aimed to provide an overview of the most effective therapeutic methods and drugs for these comorbidities (Fig. 1), highlighting their potential therapeutic mechanisms from both physiological and pharmacological perspectives. This information is expected to assist clinicians and researchers in identifying rapid and effective therapeutic strategies.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Various treatments and drugs available for neuropathic pain and depressive co-morbidities. TCA, Tricyclic antidepressants. This figure was created using Figdraw (https://www.figdraw.com).

Varying the electric current can generate a magnetic field, whereas varying the magnetic field can produce an electric current. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) utilizes figure-of-eight- or H-shaped coils to generate a fluctuating magnetic field that affects the CNS in the brain, altering the membrane potential of nerve cells [19, 20]. Additionally, TMS can change the state of the electron spin system, thereby affecting the chemical activity of compounds and achieving therapeutic effects [21]. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [22], depression, and migraine headaches. Furthermore, the efficacy of high-frequency rTMS in treating depression has been graded as A when administered to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [22, 23].

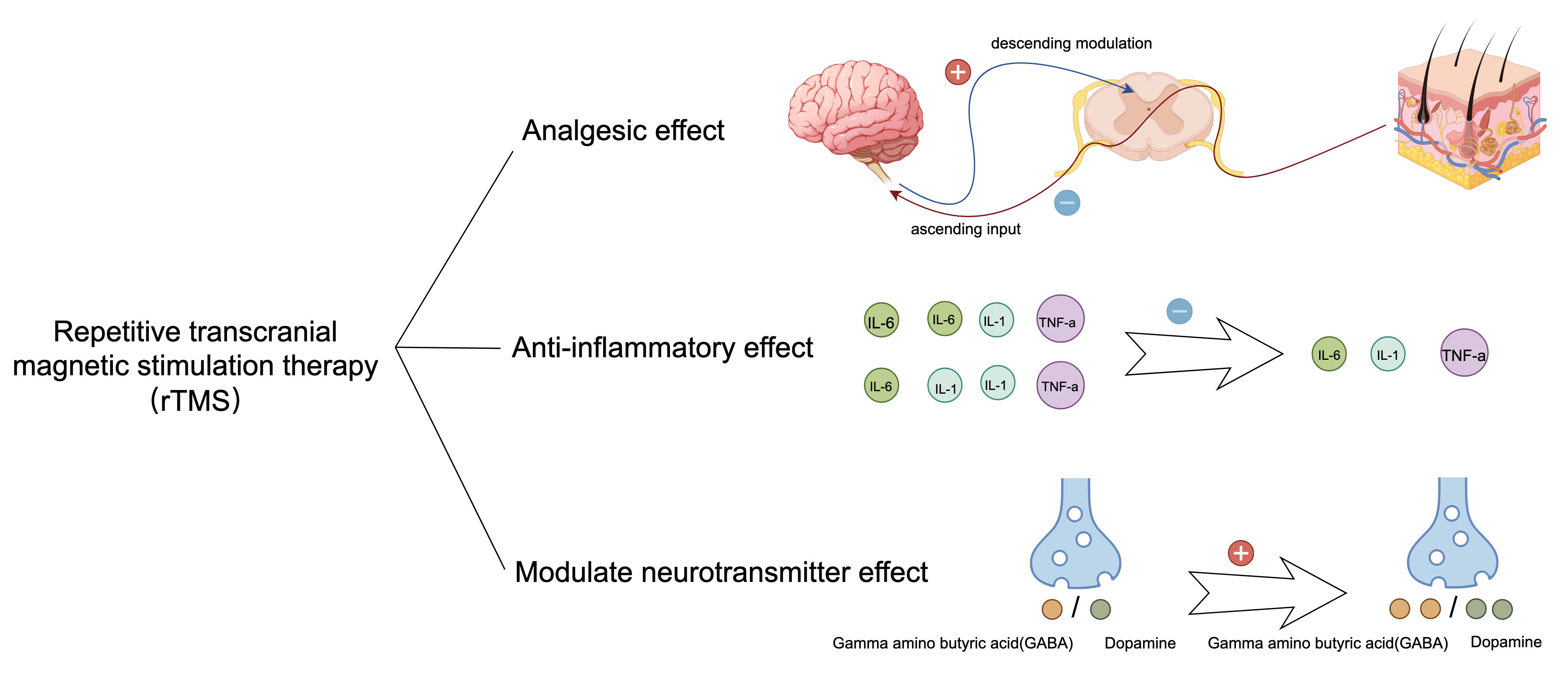

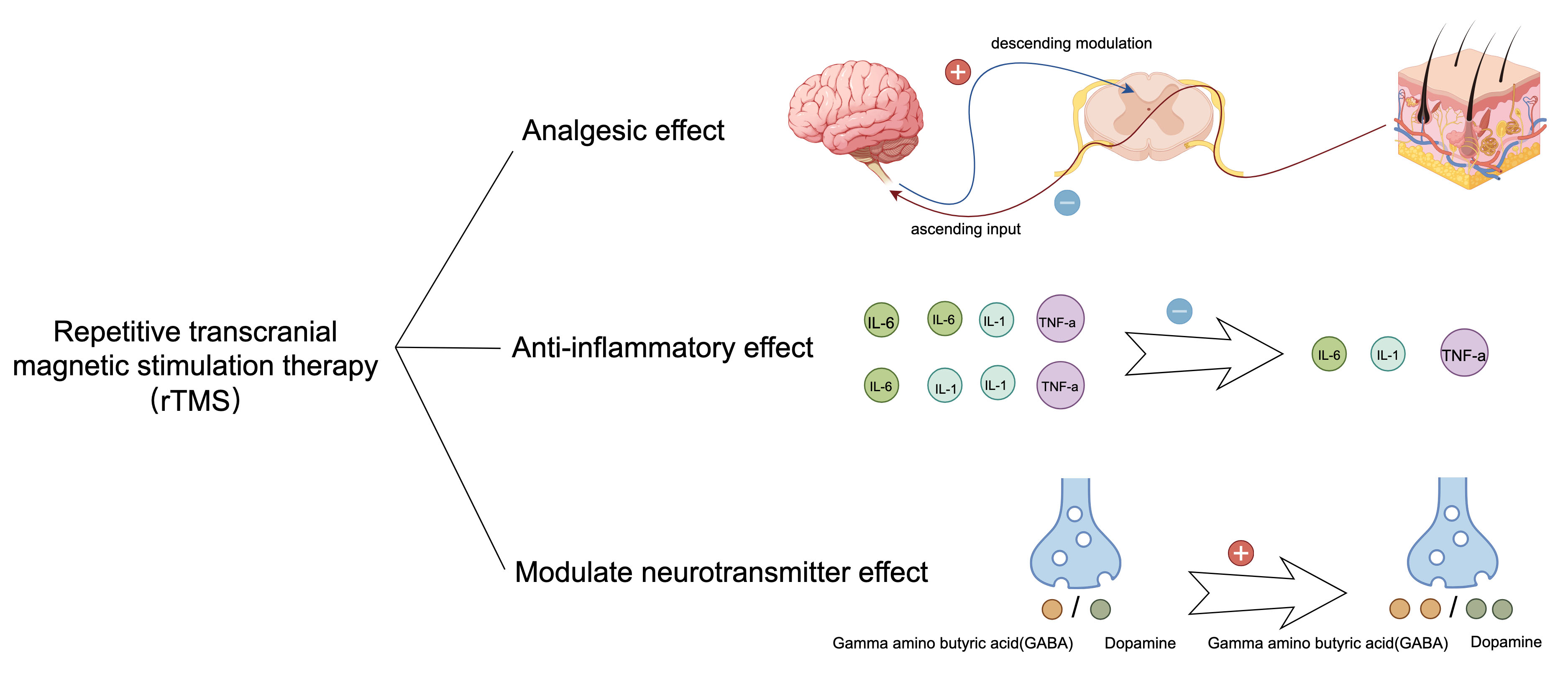

The therapeutic effects of rTMS on neuropathic pain and depressive comorbidities primarily manifest as analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and modulatory effects on neurotransmitters (Fig. 2). Analgesic effects: A single 10 Hz rTMS stimulation of the motor cortex for a period of three weeks in right-handed patients with intractable pain (resulting from thalamic stroke, brainstem stroke, spinal cord injury, brachial plexus injury, or trigeminal nerve injury) has been demonstrated to produce a notable reduction in pain levels as assessed by means of a visual analog scale (VAS) in the treatment group compared to the sham treatment group [24]. Furthermore, rTMS has been shown to drive downward pathways, thereby inhibiting pain production through electrophysiological alterations [24]. Modulatory effect on neurotransmitters: Studies indicate that under rTMS stimulation, more dopamine is released from the mesial reticular, mesolimbic, and striatal regions, whereas more

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Therapeutic effects of rTMS. After rTMS treatment, the therapy reduced the secretion of inflammatory factors IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-

Clinical and preclinical evidence suggests that rTMS treatment for comorbidities reduces pain and alleviates depressive behaviors. A clinical study suggested that in patients with postherpetic neuralgia, treatment of the motor cortex with rTMS at 10 Hz for more than 10 days can have an analgesic effect. Patients were assessed at the end of treatment. The findings indicated that rTMS therapy not only alleviated pain but also enhanced the sleep quality of the participants [28]. Furthermore, in a preclinical study, Hu et al. [27] used 10 Hz rTMS to treat the left dorsal AId of rats with chronic constriction injury (CCI) and comorbid depression for 4 weeks. Using behavioral measures, they found that rTMS ameliorated nociceptive hypersensitivity and despair behavior in rats. They found that rTMS decreased the expression of mGluR5, NMDAR2B, TNF-

Although rTMS has demonstrated good therapeutic efficacy in a clinical study, the treatment process protocols and parameter settings of therapeutic equipment for rTMS have not been standardized or regulated, which presents a challenge for promoting rTMS as a treatment for comorbidities [29].

Acupuncture involves the insertion of disposable sterile needles at specific anatomical points on the body. When used for pain management, these needles deliver electrical stimulation to acupuncture points, activating the neural network and thus regulating organ function to treat various illnesses. This technique, known as electroacupuncture (EA) [30, 31], combines traditional acupuncture and modern electrotherapy and is gaining increasing acceptance worldwide owing to its favorable therapeutic effects and lack of side effects [32].

EA has both analgesic and antidepressant effects. Analgesic effects: EA increases endogenous opioid production via two pathways: (1) Stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system facilitates the movement of opioid-producing cells towards inflammatory regions [32]. Research has shown that such stimulation can upregulate the expression of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) within the vasculature of affected tissues, thereby enhancing the migration of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells containing

EA treatment for comorbidities has only been tested in animal experiments and has not yet been administered to patients in clinical settings. One study showed that after EA treatment, mice exhibited increased mechanical and thermal pain thresholds, relieved depressive behavior, and significantly reversed downregulation of BDNF and 5-HT expression in the anterior cingulate cortex and spinal cord after chronic constriction injury [41]. Additional research has shown that EA administered to mice subjected to spared nerve injury (SNI) leads to an elevation in the population of short-chain fatty acid-generating bacteria, including Akkermansia, Ruminococcaceae, and Lachnospiraceae, in the intestinal tract. This was accompanied by alterations in histone acetylation and BDNF up-regulation. These findings suggest that EA treatment may produce therapeutic effects through the brain-gut microbiota axis [42].

Although the efficacy of EA has been demonstrated in animal models, several challenges persist before it can be effectively implemented in a clinical setting. One primary concern is the lack of consensus on the standardization of treatment parameters and the variability in treatment outcomes observed among patients. Second, the analgesic effect of EA is subject to tolerance, which is comparable to that of opioids [43, 44]. Extended treatment duration may also influence the final outcome.

TCAs were among the first antidepressants to be developed. Their molecular composition is characterized by a trio of atomic rings, featuring a central heterocyclic ring with seven members, which is bordered by a pair of benzene rings. Initially, TCAs were designed and marketed for depression treatment. However, it became evident over time that they were associated with many side effects and were potentially fatal in cases of overdose. Consequently, they have been gradually replaced by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for the treatment of depression [45, 46].

The analgesic and antidepressant effects of TCAs in the treatment of neuropathic pain and depressive comorbidities are inherently linked to their core pharmacological mechanism: binding to and inhibiting the reuptake of norepinephrine or 5-HT transporter proteins [47].Analgesic effects: Small doses of TCAs are sufficient for treating neuropathic pain, although they require prolonged administration [48]. TCAs inhibit transporter proteins, leading to increased neurotransmitter levels (norepinephrine and serotonin) in the synaptic cleft. These chemical messengers engage in a sequence of actions that dampen the transmission of pain signals within the spinal cord, with norepinephrine seemingly having a more significant impact than serotonin in this particular pathway [49]. In addition, TCAs can voltage-dependently block glutamate NMDA receptors, thereby relieving pain [50]. Antidepressant effects: The buildup of neurotransmitters within the synaptic gap results in higher levels of norepinephrine and serotonin, neurotransmitters known for their antidepressant properties [51].

Support for employing TCAs in managing concurrent disorders is primarily derived from preclinical research. A preclinical study has demonstrated the efficacy of amitriptyline in alleviating nociceptive sensitization associated with thermal and mechanical pain in rats with spared nerve injury and depressive behaviors [52]. Another preclinical study showed that combination of citicoline with imipramine produced analgesic and antidepressant effects [53]. Citicoline is a mononucleotide that comprises cytosine, choline, pyrophosphate, and ribose. It plays a dual role as both an essential intermediate and inducer in the synthesis pathways of structural membrane phospholipids, specifically phosphatidylcholine [54]. Additionally, acetylcholine, a crucial neurotransmitter, aids in the integration of phospholipids into cell membranes and boosts the production of structural phospholipids [55]. Moreover, it increases the concentrations of acetylcholine, norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin in particular brain regions [54]. Researchers employed a combination of imipramine (50 mg/kg) and citicoline (1.25, 2.5, and 5 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection in mice and observed the effects of imipramine and citicoline. The effects of imipramine and citicoline on pain and depressive behavior in mice were observed using a series of behavioral tests. The findings revealed that the co-administration of imipramine and citicoline extended the tail-flick latency and decreased the resting period during the forced swimming test (FST) in mice, suggesting potential for pain-relieving and mood-enhancing activities. Notably, a synergistic interaction was observed between imipramine and citicoline in eliciting these analgesic and antidepressant effects [53].

Although TCAs have shown promising therapeutic effects in animal experiments, their clinical application is hindered by severe side effects. TCAs impede the transport of norepinephrine and serotonin, and also occupy various receptors including post-synaptic histamine, alpha-adrenergic, and muscarinic-acetylcholine, which can result in a spectrum of side effects like xerostomia, disorientation, and diminished cognitive function. Other reported side effects included hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, blurred vision, urinary retention, somnolence, and sedation. Owing to their anticholinergic properties, TCAs are not recommended for patients with heart disease, glaucoma, or urinary retention issues [56, 57, 58]. To circumvent the deleterious side effects that impose additional suffering on patients, a treatment regimen analogous to the combination of citicoline and imipramine may be beneficial. This regimen involves reducing the dosage of TCAs and leveraging the synergistic effect of drugs to maintain therapeutic efficacy. This approach may serve as a model for the application of TCAs for the treatment of comorbidities.

Dihydromyricetin (DHM), is a flavonoid derived from the plant Ampelopsis glandulosa, which is prevalent in southern China. This compound exhibits a broad spectrum of therapeutic benefits, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticancer, and liver-protective actions. It is also utilized in the prevention and management of conditions like nephritis, hepatitis, and anorexia nervosa. While in the United States, DHM is solely sanctioned as a dietary supplement to counteract alcohol-induced hangovers, it possesses the potential to address neuropathic pain and associated depressive symptoms [59, 60].

While the principal molecular actions of DHM remain unclear, it is known to alleviate pain and exhibit antidepressant properties by inhibiting the activation of glial cells, inhibiting pain signaling, enhancing the expression of BDNF, and anti-inflammatory effects. Inhibition of glial cell activation: An increasing amount of research suggests that DHM administration can enhance the activity of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) and facilitate the shift of microglial cells from the inflammatory pro-inflammatory microglia/macrophages (M1) phenotype to the anti-inflammatory and reparative anti-inflammatory microglia/macrophages (M2) phenotype [61]. Inhibition of pain signaling: DHM decreases the levels of P2X7 receptor expression in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG), spinal cord, and hippocampus. These receptors, which belong to the ATP-activated ion channel family, are associated with the transmission of pain signals and the development of depressive disorders [62]. Additionally, DHM provides protection against P2X7 receptor-mediated damage to astrocytes in the hippocampus [63]. Upregulation of BNDF: BDNF is a crucial element in the pathophysiology of depression, as indicated by the lower BDNF concentrations found in the brains of individuals with major depressive disorder when contrasted with healthy controls. Furthermore, the direct application of BDNF to the midbrain or hippocampus has been shown to alleviate behaviors associated with depression [64]. Research has shown that DHM triggers the ERK1/2-CREB signaling pathway, enhances the phosphorylation at the ser-9 residue of glycogen synthase kinase 3

Currently, only preclinical evidence of DHM in the treatment of comorbidities has shown that it reduces pain and alleviates depression. Researchers used a high-sugar, high-fat diet; injections of streptozotocin (STZ); and chronic unpredictable stress to create a comorbid rat model of diabetic neuropathic pain and depression, followed by intraperitoneal injections of DHM to comorbid rats, and found that DHM reduced pain and alleviated depressive behavior. Simultaneously, they measured BDNF and TrkB expression before and after modeling and found that BDNF/TrkB expression levels were reduced in the hippocampus and increased in the spinal cord and DRG after modeling, and DHM could reverse these changes [67]. Another study used the same model as the previous one and found that DHM reduced pain and alleviated depressive behaviors by reducing the P2X7 receptor [63].

However, DHM is highly insoluble and dissolves only in hot water and ethanol. Most of the DHM compounds and their metabolites are eliminated through feces, with a small fraction being absorbed in the small intestine. The absorbed substances then enter the systemic circulation through the portal vein, subsequently reaching the liver. In the liver, these compounds are subjected to additional metabolic processes, including glucuronidation, sulfonation, and methylation, to form phase II metabolites, which are then assimilated into the body. DHM is inherently unstable and undergoes degradation when exposed to light, pH buffers, pepsin, and pancreatic enzymes [68, 69, 70]. In conclusion, the low bioavailability and chemical instability of DHM restricts its pharmacological effects and clinical applications.

Palmatine, an isoquinoline alkaloid derived from traditional Chinese medicinal herbs, exists naturally. It is characterized as an ammonium salt with four methoxy groups attached to phenyl rings at the C2 and C3 positions. Over recent years, a plethora of studies has been dedicated to exploring the pharmacological properties of palmatine, revealing its potential as a neuroprotectant, an anticarcinogenic agent, a bactericide, a viricide, an antioxidant, an anti-inflammatory, and a lipid-modulating compound [71, 72].

Palmatine has both analgesic and antidepressant effects. Analgesic effects Palmatine exerts analgesic effects by inhibiting neuroinflammation via the Clec7a-MAPK/NF-

For preclinical comorbidities, only preclinical data are available, with no clinical application results. Preclinical studies have shown that preclinical treatment can reduce nociceptive hypersensitivity and behaviors. Shen et al. [76] employed STZ to develop a rat model for type 2 diabetes, which led to the onset of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and depressive symptoms in the rats. Following this, researchers administered palmatine intraperitoneally and evaluated its impact on the rats’ behavior, discovering that it lessened pain sensitivity and improved depressive symptoms. Through using western blot analysis, and immunohistochemical techniques, it was determined that palmatine decreased hippocampal expression levels of P2X7 receptors, GFAP, TNF-

The side effects of palmatine are relatively mild, with isolated cases of gastrointestinal discomfort, appetite loss, and constipation. Palmatine has low bioavailability in vivo and is hepatotoxic at high doses [77]. Interestingly, when used at low doses, palmatine exerts a hepatoprotective effect, suggesting that it may have a biphasic effect of activation at low concentrations and inhibition at high concentrations [78]. Palmatine has fewer side effects than other treatments for neuropathic pain and depressive comorbidities, making it a viable option for clinical trials.

Ketamine, a phencyclidine derivative, exerts analgesic and anesthetic effects primarily by inhibiting NMDA receptors [79]. However, this is not the sole mechanism of action. Ketamine shows a high affinity for dopamine and serotonin binding sites, which may contribute to its various clinical effects. The fact that serotonin antagonists, such as methysergide, antagonize the analgesic effects of ketamine also suggests its involvement in analgesia via the serotonergic pathway [80]. Additionally, ketamine has been shown to antagonize muscarinic receptors, leading to increased sympathetic tone, pupil dilation, and bronchodilation [80, 81, 82].

Ketamine possesses dual properties of analgesia and antidepressant activity. Analgesic effects: The spinal cord’s dorsal horn is equipped with both ionotropic glutamate receptors, including NMDA, AMPA, and kainate, as well as metabotropic glutamate receptors, all of which play a role in the genesis of neuropathic pain. The interaction of excitatory amino acids with NMDA receptors is believed to be a key factor in neuronal hyperexcitability, which leads to abnormal nociceptive hypersensitivity. Therefore, medications that modulate NMDA receptor activity may alleviate neuropathic pain [83, 84].

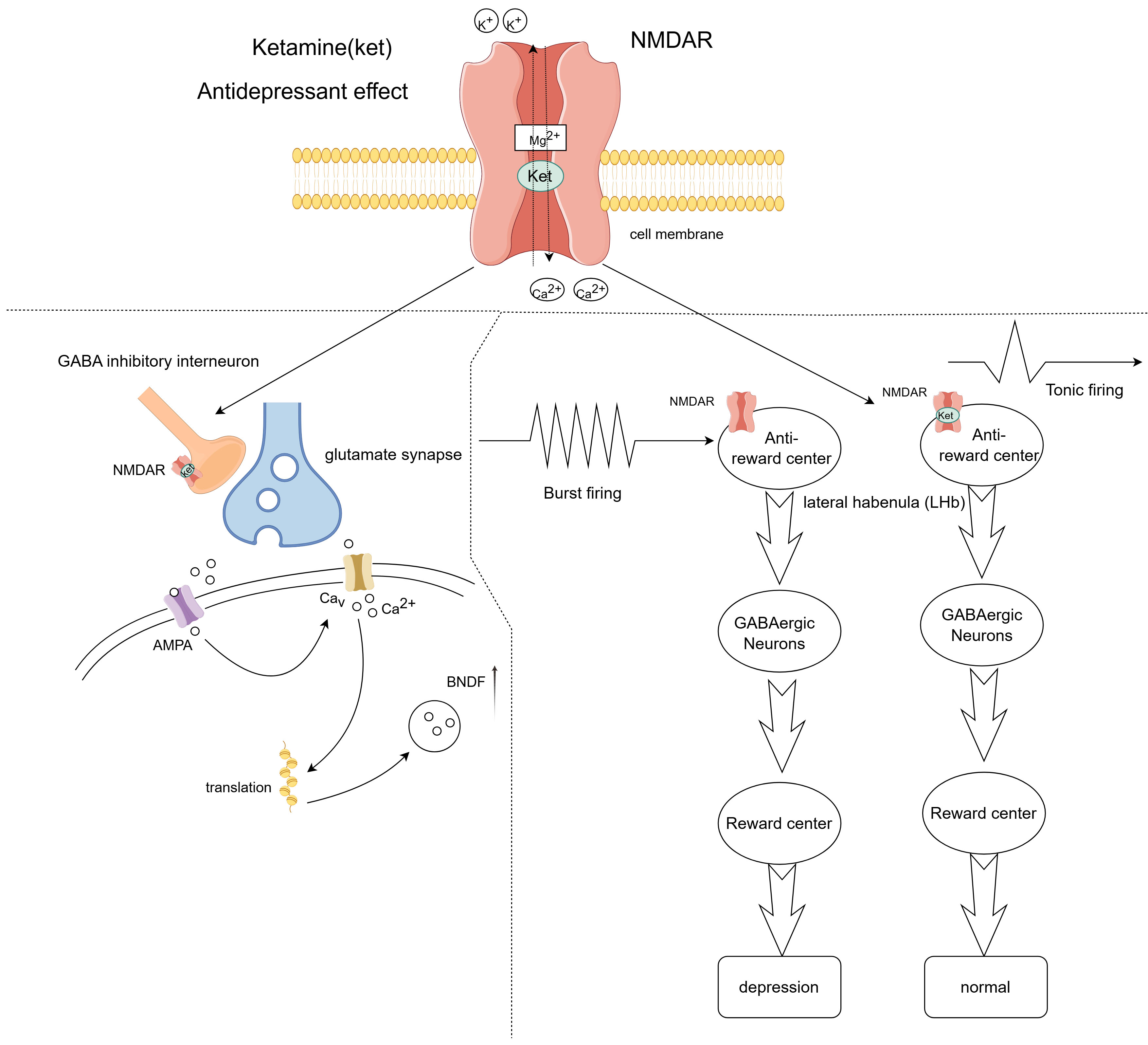

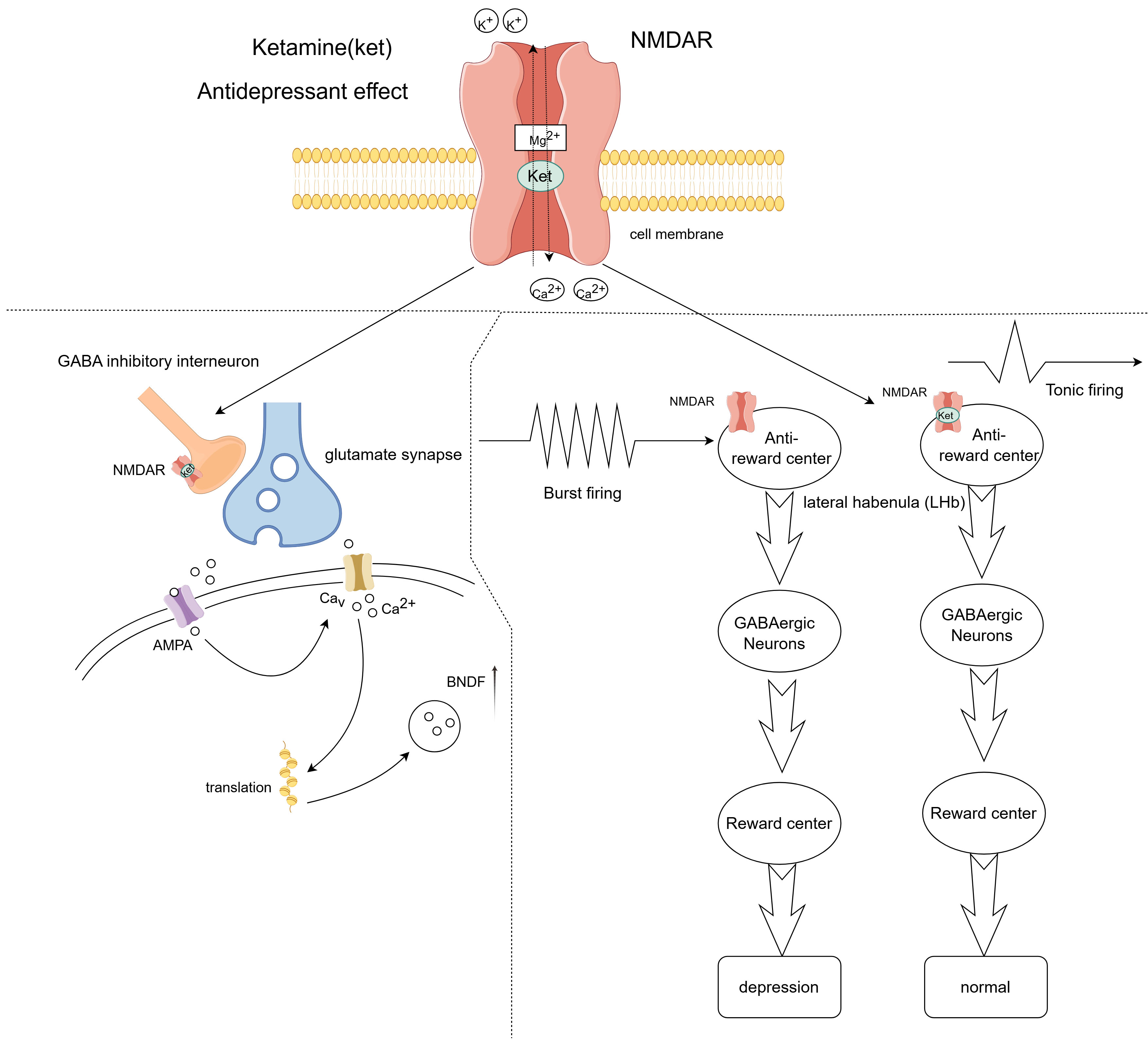

Furthermore, ketamine is believed to prevent and reduce the intensity of neuropathic pain by suppressing inflammatory signaling within diverse neuroglial cells that contribute to the establishment of painful conditions [85]. Antidepressant effects: Ketamine, when administered in subanesthetic doses, has become a novel approach for treating depression that is unresponsive to conventional therapies, demonstrating swift and potent antidepressant properties shortly after its application (Fig. 3). Compared to traditional antidepressants, which often have a delayed onset of action, depressive symptoms improve significantly after 40 minutes of ketamine treatment and maintain their efficacy for up to 72 hours [86, 87]. Ketamine blocks NMDA receptors in GABA neurons in the brain, preventing eEF2 phosphorylation and increasing BDNF levels. This, in turn, promotes AMPA receptor expression in synapses and increases synaptic connectivity [88]. A recent study showed that ketamine operates by blocking NMDA receptors on the lateral habenula, inhibiting bursts of electrical activity in neurons, which subsequently disengages the downstream reward centers [89]. The engagement of the reward system is crucial in the context of depression [90].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Antidepressant effects of ketamine. Ketamine exerts its antidepressant effects by blocking N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors on GABA-inhibitory interneurons, causing glutamatergic neurons to release more neurotransmitters that activate

Ketamine only has preclinical evidence to show its effectiveness in treating comorbidities. In a preclinical study, a single subanesthetic dose of ketamine (10 mg/kg) was administered to mice with SNI depressive comorbidities. This treatment improved depression-related behaviors compared to the sham-operated group. However, nerve injury-induced nociceptive sensitization was not alleviated, possibly because a lower dose of ketamine did not have a better analgesic effect [91].

Regarding adverse effects, the repeated and high-dose use of ketamine carries the risk of developing tolerance and dependency. Prolonged misuse of ketamine can lead to urinary system symptoms and a condition known as ulcerative cystitis. Even with subanesthetic doses, ketamine has been associated with acute side effects such as increased blood pressure, nausea, headaches, blurred vision, altered perceptions, drowsiness, lightheadedness, psychotic episodes, and feelings of anxiety [92, 93, 94]. Though ketamine in doses below those used for anesthesia is utilized to address neuropathic pain and associated depressive symptoms, and it holds promise for the swift amelioration of depressive behaviors, concerns persist regarding its potential side effects and the development of tolerance.

Gabapentin is an antiepileptic drug, a derivative of GABA, with distinct pharmacology compared to existing antiepileptic drugs. Gabapentin is frequently employed as an adjunctive medication when traditional antiepileptic drugs are ineffective or intolerable to the patient. Several studies have demonstrated that the frequency of seizures significantly decreases when gabapentin is added to the treatment regimen. Furthermore, the long-term effects of gabapentin have been proven satisfactory, with fewer adverse effects. Over the past decade, it has been increasingly used for the treatment of neuropathic pain in adults and has become the preferred analgesic of choice [95, 96].

Gabapentin exhibits analgesic effects but lacks antidepressant properties. Analgesic effects: Gabapentin inhibits calcium channels via the

Clinical data does not substantiate the efficacy of gabapentin for managing concurrent disorders. However, preclinical investigations have indicated that gabapentin may alleviate depression associated with pain by altering the activity of dopaminergic neurons and reducing

Gabapentin is generally well tolerated and has very few serious side effects. The predominant adverse effects included somnolence, lightheadedness, and exhaustion. Serious complications, including respiratory distress, visual impairments, and muscle disease, are seldom documented [100, 101]. Nevertheless, there is a potential for misuse and dependency with gabapentin among patients who have a history of or are currently struggling with substance use disorders (SUD) [102]. Therefore, physicians should exercise caution when prescribing gabapentin.

Minocycline is a second-generation tetracycline drug known for its improved pharmacokinetics compared to first-generation tetracyclines; it is completely absorbed when administered orally. This extensive-spectrum antibiotic has an antibacterial range akin to tetracycline, exerting a potent impact on Gram-positive bacteria such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Staphylococcus aureus, and Neisseria gonorrhea among the Gram-negative strains. Its antimicrobial properties stem from its ability to attach to the A site of the 30S ribosomal subunit, which hinders peptide chain elongation and, in turn, curbs bacterial protein synthesis. Primarily classified as a bacteriostatic agent, minocycline can exhibit bactericidal properties at elevated concentrations [103, 104, 105].

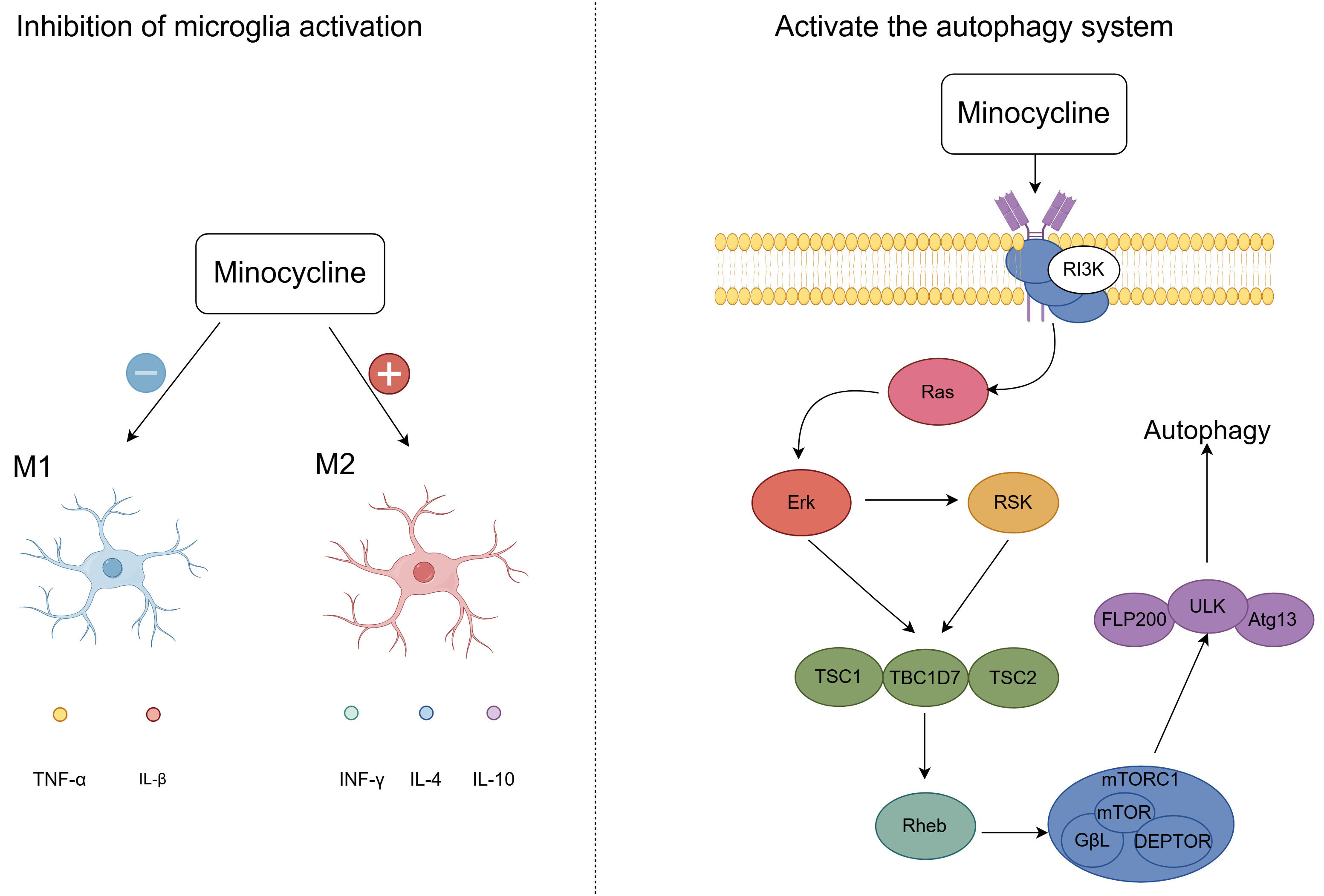

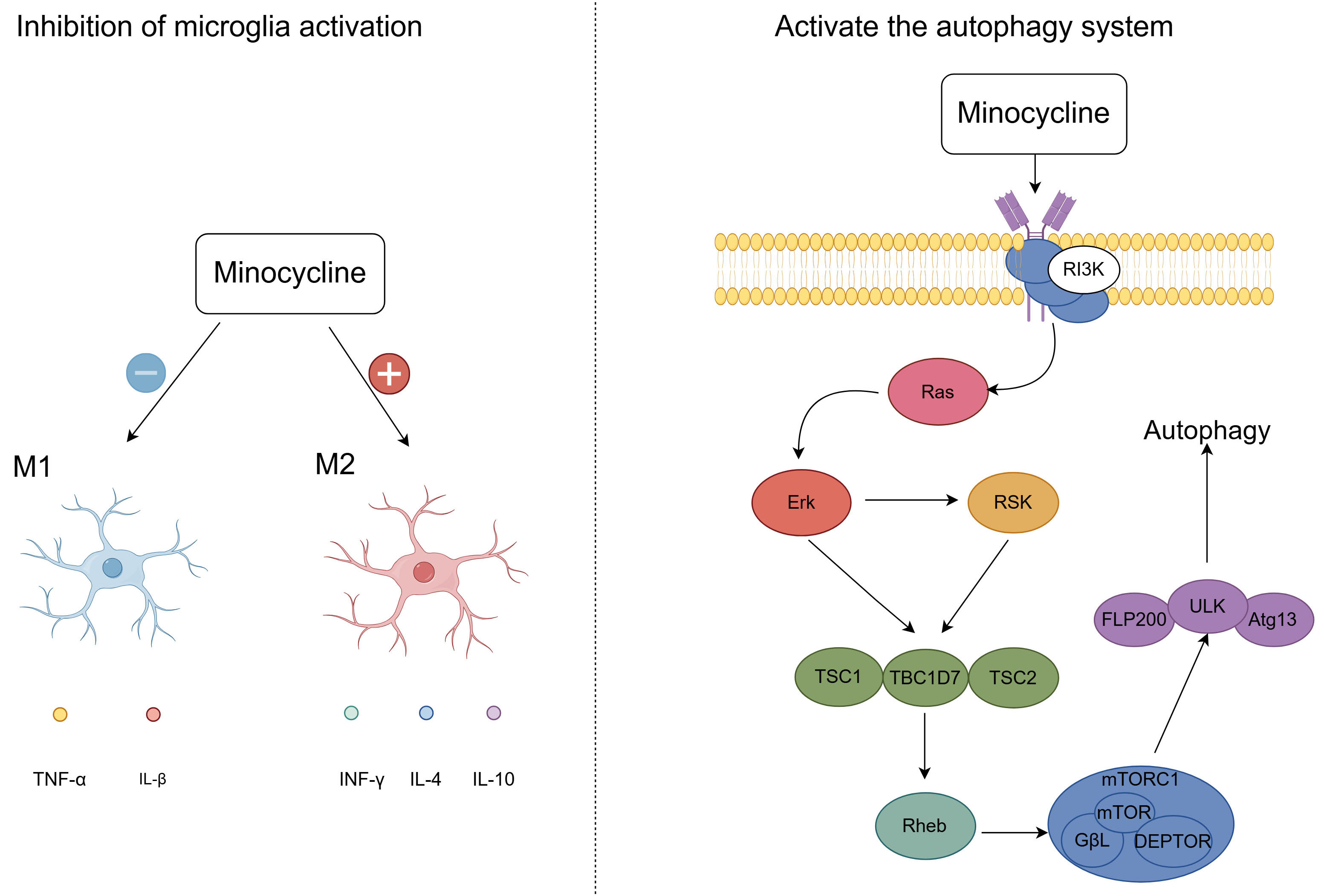

Minocycline has both analgesic and antidepressant effects. Analgesic effects: By suppressing the activation of microglia, minocycline produces analgesic effects, with microglia being crucial in the context of neuropathic pain. Research demonstrated that administering minocycline to rats post-spinal cord injury resulted in the inhibition of the IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling cascade within microglia, thereby alleviating hyperalgesia in these animals [106]. This indicates that minocycline potentially mitigates pain by targeting the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway within microglial cells. Furthermore, minocycline activates the autophagy system via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. This activation may facilitate neuroprotection and functional recovery through the upregulation of Beclin-1 and LC3B in the early stages of spinal cord injury [107] (Fig. 4). Antidepressant effects: Minocycline prevents the polarization of activated microglia towards the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and encourages their shift towards the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [108] (Fig. 4). Moreover, Minocycline is capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier and counteracting the activity of NMDA receptors within the central nervous system, thereby eliciting anti-inflammatory effects and potentially offering therapeutic benefits in the treatment of depression [109, 110]. Additional research has demonstrated that minocycline provides therapeutic benefits by curbing the release of high mobility group box-1 protein (HMGB1) from neurons and microglia, hinting that HMGB1 could serve as a promising therapeutic target for depression treatment [111].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Analgesic and Antidepressant effects of minocycline. After minocycline treatment, the drug promoted microglial activation to the M2 phenotype and inhibited microglial activation to the M1 phenotype. Minocycline also activates the autophagy system via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, promoting recovery from spinal cord injury. M1, Pro-inflammatory Microglia/Macrophages; M2, Anti-inflammatory Microglia/Macrophages; IFN-

Clinical data does not support the efficacy of minocycline for managing concurrent conditions. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that minocycline treatment can attenuate olfactory bulbectomy-induced depression-like behavior and alleviate spinal nerve ligation (SNL)-induced mechanical nociceptive hypersensitivity in olfactory bulbectomized rats [112]. However, minocycline has not been clinically used to treat comorbidities.

The side effects of minocycline primarily include vestibular toxicity, hepatotoxicity, and gastrointestinal discomfort. Vestibular toxicity: Vestibular toxicity is a rare but well-documented phenomenon that manifests as dizziness, tinnitus, and imbalance in some individuals following ingestion of minocycline. Gastrointestinal discomfort: Gastrointestinal discomfort, on the other hand, is a more common adverse reaction that often presents as nausea, vomiting, and other digestive issues. Hepatotoxicity: Hepatotoxicity is also a concern because the liver predominantly metabolizes minocycline. Individuals with poor liver function may experience elevated transaminase levels after minocycline injection, potentially leading to manifestations of drug-induced hepatitis [113, 114, 115]. The available literature on the use of minocycline for addressing neuropathic pain and associated depressive disorders is sparse, which necessitates careful consideration of its application due to potential side effects.

The complexity of neuropathic pain and depression comorbidities has resulted in a lack of clarity regarding the underlying mechanisms. Current treatment problems include suboptimal treatment protocols, high side effects associated with single-drug therapy, excessive side effects from multiple drugs, drug resistance, and nonuniformity of the physiotherapy treatment process, all of which hinder treatment efficacy. Learning from the citicoline and imipramine combination treatment plan, we can explore the use of multiple-drug regimens to minimize the side effects of a single drug and assess synergistic effects. In addition, drugs can be developed against effective targets, such as inhibition of glial cell activation, modulation of BNDF, and regulation of P2X4/P2X7. Providing patients with meticulous care and positive psychological counseling is essential. Ultimately, we hope that our endeavors will lead to expeditious eradication of the disease in patients.

Conceptualization: YG and XM; writing - original draft preparation: ZC and TC; writing - review and editing: ZC; supervision: HY; literature review, collecting and sorting references: ZC and TC; designing and drawing the figures: ZC and HY. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to thank Editage (https://www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

This work was supported by grants from the Young Scholarship Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China to Xiaqing Ma (82201366), and Jiangsu Provincial Research Hospital: YJXYY202204-YSB33 to Xiaqing Ma.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.