1 Department of Oncology, Cancer Center, Meizhou People’s Hospital (Huangtang Hospital), 514031 Meizhou, Guangdong, China

2 Medical Research and Experimental Center, Meizhou People’s Hospital (Huangtang Hospital), 514031 Meizhou, Guangdong, China

Abstract

Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairments are a significant adverse sequela of cancer treatment. The potential mechanism of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairments remains elusive. The present study evaluated the impact of a commonly utilized chemotherapy agent, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), on acetylcholine (ACh) levels in the hippocampus.

5-FU was injected into mice once a day for 10 days to create a mouse model of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment. Microdialysis and HPLC-MS/MS were used to determine hippocampal ACh levels. Biocytin injection and patch-clamp recordings were performed on cholinergic (ChAT) neurons in the medial septum (MS) to observe their morphological and electrophysiological changes. Chemogenetic tools were used to activate ChAT neurons in the MS. The acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil was injected i.p. into mice to elevate ACh levels in the brain.

Cognitive performance in mice was impaired after 5-FU treatment, accompanied by reduced ACh release in the hippocampus. The administration of 5-FU led to compromised structural integrity and diminished activity of ChAT neurons in the MS. Chemogenetic stimulation of MS ChAT neurons ameliorated the cognitive impairments. The administration of donepezil also reduced the cognitive impairments caused by 5-FU.

5-FU therapy caused cognitive impairments in mice by affecting the neuronal structure and activity of ChAT neurons in the MS. Inducing the increase of ACh levels could be a promising therapeutic approach for addressing 5-FU treatment-induced cognitive impairments.

Keywords

- 5-fluorouracil

- acetylcholine

- cholinergic neurons

- cognitive impairments

- medial septum

The majority of cancer patients still rely on chemotherapy as the primary approach for successful anti-cancer treatment, even in the era of novel therapies [1, 2]. However, the occurrence of neurotoxicity is commonly observed during chemotherapy [3]. The phenomenon known as “chemobrain” or “chemofog” is observed in approximately 75% of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, and results in persistent cognitive impairments [4, 5]. Cognitive dysfunction is characterized by impairments in attention and memory and reduced concentration after treatment [6, 7, 8]. The increasing survival rate of cancer patients necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the etiology behind chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairments and the development of preventive strategies to enhance patient quality of life.

The chemotherapeutic drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is classified as an antimetabolite due to its ability to interfere with metabolic processes [9]. It is frequently used in the management of various forms of cancer, including bowel, prostate, and breast cancer [10, 11]. Previous studies have identified cognitive impairments as a frequent consequence of 5-FU treatment [12, 13, 14], adversely affecting animal spatial and non-spatial memory [15, 16, 17]. The primary mechanism of 5-FU involves suppressing thymidylate synthase activity, thereby impeding the production of thymidine, an essential component in DNA replication [9]. The ability of 5-FU to traverse the blood-brain barrier (BBB) partly contributes to its adverse effects on the central nervous system [18]. However, the underlying mechanism of cognitive impairment related to 5-FU treatment has not been thoroughly elucidated.

The neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) in the brain is mainly released from cholinergic neurons (ChAT neurons) and plays a crucial role in cognitive function as an indispensable excitatory agent [19]. Recent research consistently highlights the pivotal role of cholinergic circuits in normal executive and mnemonic functioning, providing compelling evidence for the inseparable connection between cognitive decline and the loss of ACh signaling in the hippocampus [20]. Different subtypes of nicotinic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors are present at both presynaptic and postsynaptic locations in principal neurons and inhibitory interneurons in the hippocampus, significantly affecting synaptic transmission in both directions [21]. Evidence further supports the involvement of ACh release in both the initiation and maintenance of synaptic plasticity and its significant impact on hippocampal network oscillations [22]. The hippocampus receives the majority of its cholinergic inputs from projections originating in the medial septum (MS) through the pre-commissural branch of the fimbria-fornix pathway [20]. Abnormalities of cholinergic transmission constitute a significant contributing factor in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairments observed in various psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease [23, 24]. However, the impact of chemotherapy on cholinergic transmission in the hippocampus remains uncertain.

The present study investigated how 5-FU affects the release of ACh within the hippocampus. Based on our observations, we speculated that manipulations of increase ACh levels could potentially serve as promising therapeutic approaches for addressing 5-FU treatment-induced cognitive impairments.

Male C57BL/6 J mice were acquired from Southern Medical University’s Animal Center in Guangzhou, China. ChAT-Cre mice and Ai14 reporter mice were gifts from Tianming Gao at Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, China). ChAT-Cre mice were crossed with the Ai14 reporter mice to label the ChAT neurons with tdTomato (ChAT-Cre:Ai14 mice). All mice were housed in a controlled environment with a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 08:00 AM) and were provided with ad libitum access to food and water under standard conditions (21–26 °C). The behavioral experiment adhered to the guidelines set by the Chinese Council on Animal Care, ensuring compliance with professional and ethical standards. All behavioral testing was undertaken during the light phase of the light/dark cycle. The mice were prepared for testing by being handled gently for at least 5 days to reduce the stress that comes with manipulation. A total of 105 male mice were used in the experiment. Control group (i.p. saline, #RE1330, G-CLONE, Beijing, China); 5-FU group (i.p. 5-FU, #F6627, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); 5-FU+hM3Dq group (i.p. 5-FU with hM3Dq expressed in cholinergic neurons of MS); 5-FU+donepezil group (i.p. 5-FU followed by i.p. donepezil (#D6821, Sigma-Aldrich) before behavioral experiments). The ethical approval code and number for this experiment is 2023-F-09-01. The entirety of our endeavors was devoted to mitigating animal distress.

Mice in the 5-FU group received i.p. injections of 50 mg/kg b.w. 5-FU [25, 26]. An injection of the designer medication clozapine-N-oxide (CNO, 5 mg/kg, i.p.; #C0832, Sigma-Aldrich) was given 30 min before behavioral testing, in order to simplify chemogenetic manipulations [27]. To elevate ACh levels, donepezil was injected i.p. at a 1.0 mg/kg dose [28]. Control mice were injected with saline.

The OFT was conducted as described in our previous study [29].

Mice were placed in a transparent plastic-walled open chamber measuring 40

The NOR test was conducted as described in our previous study [29]. A

rectangular container of 30

The MWM test was conducted as described in our previous study [29]. The maze was constructed using a circular container measuring 1 m in diameter, which contained non-transparent water kept at a consistent temperature of 21 °C. The maze was separated into four parts, one with a concealed platform 10 cm across and 1 cm below the water’s surface. Three carefully positioned indicators outside the maze were spatial references to teach the mice how to find their way to the platform. They were placed into the water semi-randomly during the learning phase to stop the mice from forming particular strategies. The mice were given 90 s to search for the platform; if they could not find it within this time, they were directed gently to it. They were allowed to stand on the platform for 30 s before the next trial was initiated. After 4 trials, the mice were completely dried and were returned to their designated home cages. Training was conducted over 6 consecutive days, with each day consisting of 4 trials/mouse. The escape latency was measured as the time taken by each mouse to find the concealed platform in quadrant Q1 (identified as the target quadrant). On the day 7, the mice were given no platform and allowed to swim freely for 90 s during the spatial0-probe trials. During these trials, the drop location was initially oriented toward the wall at the boundary between quadrants three and four. The period spent in quadrant Q1, the number of times they crossed spaces that had previously contained the platform, and swimming speed, were among the data gathered. The mice also underwent a visual-cued testing session that same afternoon, in which flags were used to show different start and goal locations for every trial. A Panasonic camera model (WVBP334, Panasonic Corporation, Osaka, Japan) was used to record swimming behavior, and Ethovision XT video tracking software was used to analyze the video footage.

The microdialysis system was purchased from the Carnegie Medicine Associates (CMA, Stockholm, Sweden). A microdialysis probe (CMA/20, CMA) was inserted using a guide cannula into the dorsal hippocampal region (coordinates: AP, –2.0 mm; ML, –1.3 mm; DV, –1.6 mm; AP: anterior-posterior, ML: medial-lateral, DV: dorsal-ventral) to assess the amount of extracellular ACh in the hippocampus. Microdialysis began with the probe connected to a microinjection pump system (CMA/100, CMA). An artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) solution ((125 mM NaCl (#S9888); 2.5 mM KCl (#P5405); 1.26 mM CaCl2 (#C5670); 1.18 mM MgCl2 (#M8266)); All chemicals used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) that included neostigmine at a concentration of 10 µM, was circulated continuously in the probe, maintaining a flow rate of 1 µL/min to inhibit the degradation of ACh. Before the experiments, the dialysate concentrations were adjusted by dialysis of a specifically formulated artificial CSF solution containing 5 nM ACh (#A9101, Sigma-Aldrich). In the microdialysis procedure for both control and 5-FU mice, the initial 60-min perfusion exudate was discarded to ensure system equilibrium, with subsequent samples collected after a minimum of 1 h. Prior to being analyzed using HPLC-MS/MS (1260 Infinity III, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), the samples had been frozen at –80 °C.

The mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (75 mg/kg, i.p., #57-33-0,

Toronto Research Chemicals, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and subsequently decapitated to

collect hippocampal tissue. After weighing and homogenizing in

PBS (#P924709-5EA, Macklin, Shanghai, China), the samples were centrifuged at

25,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. AChE concentrations in the supernatants

were assessed using an assay kit (#ab138871,

Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). In a volume of 100 µL/well, 50 µL

of ACh stock was added to the standard, blank, and test samples, followed by

incubation for 30 min at room temperature away from light. Absorbances were read

at OD = 410

Biocytin was used in this study to investigate changes in the morphology of neurons. To prevent ATP/GTP from degrading, the solution and aliquots listed below were prepared and kept in a cold environment. The following ingredients (in mM) were added to a 25 mL solution: 10 NaCl; 0.3 Na-GTP (#51120, Sigma-Aldrich); 10 EGTA (#E3889, Sigma-Aldrich); 1 MgCl2; 110 K-gluconic acid (#G4500, Sigma-Aldrich); 2 Mg2+-ATP (#A9187, Sigma-Aldrich); 40 HEPES (#H4034, Sigma-Aldrich); and 0.1% biocytin (#B4261, Sigma-Aldrich). The pH was adjusted to 7.3 using a solution of NaOH (5 M, #655104, Sigma-Aldrich) to ensure osmolarity ranges of 280 to 300 mOsm. Biocytin was included in the internal solution to visualize recorded cells, and slices were drop fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (#158127, Sigma-Aldrich) for 12 h. Then, the slices were permeabilized, and stained for Streptavidin-AF488 (#S11223, Thermo Fisher).

To analyze the three-dimensional morphology of dendrites, we used Imaris software (Imaris 8.1, Oxford Instruments, Oxford, United Kingdom) to calculate the overall branching pattern and examine the characteristics of spines. In short, we imported a z-stack acquisition into Imaris and performed manual tracing after calibration. Subsequently, we determined the total length of dendrites. Sholl analysis was conducted with an interval set at 10 µm.

The brains were collected and refrigerated in a modified artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) maintained at a low temperature with ice after the mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium. The ACSF solution consisted of glycerol (250 mM, #G6279); KCl (2 mM); MgSO4 (10 mM, #M2643); CaCl2 (0.2 mM); NaH2PO4 (1.3 mM, #S5011); NaHCO3 (26 mM, #S5761); and glucose (10 mM, #G7021), All chemicals used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The brain slices were prepared by cutting 300 µm horizontal sections using a vibrating microtome (VT1200S, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Before being recorded, these slices were allowed to sit at room temperature for 1 h. All solutions used during this process contained a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 to ensure proper saturation levels.

Slices were placed in the recording chamber in an ACSF solution maintained between 32 and 34 °C. We used ChAT-Cre:Ai14 mice to specifically label ChAT neurons with tdTomato. Neurons showing fluorescence were examined by a microscope (Eclipse FN1, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with an infrared-sensitive charge-coupled device camera. Spontaneous firing patterns were recorded in a cell-attached mode using an analog-to-digital converter (Digi data 1440A, Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA), and an amplifier (Multi Clamp 700B, Axon Instruments, San Jose, CA, USA).

Neuronal excitability was assessed by examining the rate of firing in response to depolarizing pulses. At the same time, CNO was present to confirm the regulation of these neurons using DREADD. An ACSF solution (18 mM NaCl; 0.6 mM EGTA; 133 mM potassium gluconate (#G4500, Sigma-Aldrich); 10 mM HEPES; 2 mM Mg2+-ATP; and 0.3 mM sodium glutamate (#G5889, Sigma-Aldrich)) at pH 7.2 and 280 mOsm was added to the pipettes. Steady current was applied with increments of +20 pA, from –60 pA to +220 pA.

Microelectrodes (with a resistance of 3–5 M

Under pentobarbital anesthesia (75 mg/kg, i.p.), a stereotactic brain injection

was administered to mice using a stereotaxic instrument (RWD, Shenzhen, China).

We used adeno-associated virus (AAV), AAV-Ef1

All statistical analyses were conducted using the GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Prism

8, Dotmatics, Boston, MA, USA). We used Student’s t-test for simple

statistical comparisons. Post hoc analyses and 1- and 2-way ANOVAs were used to

analyze the data from the experimental groups with multiple comparisons.

According to the following standards, the figures show significant statistical

results: *p

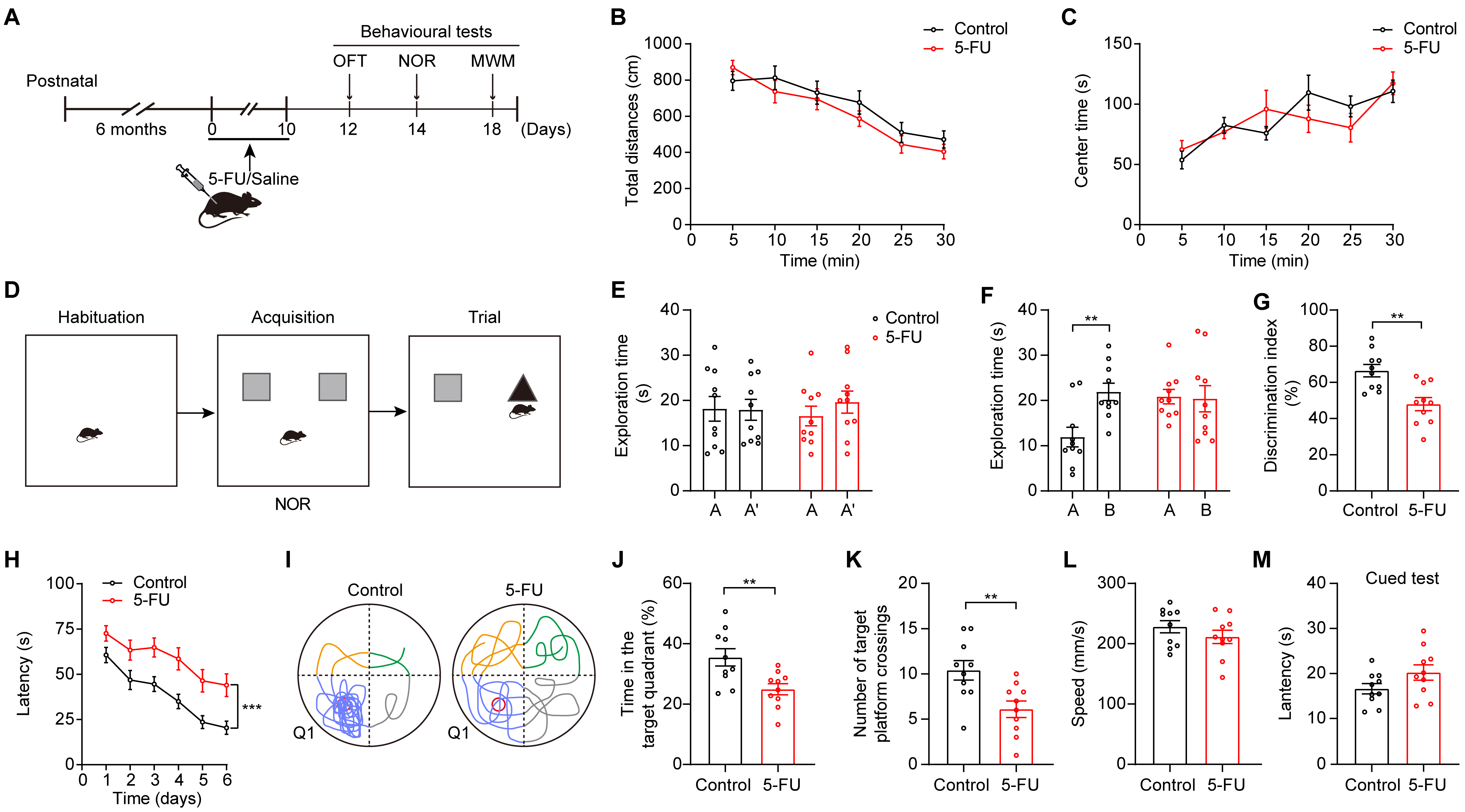

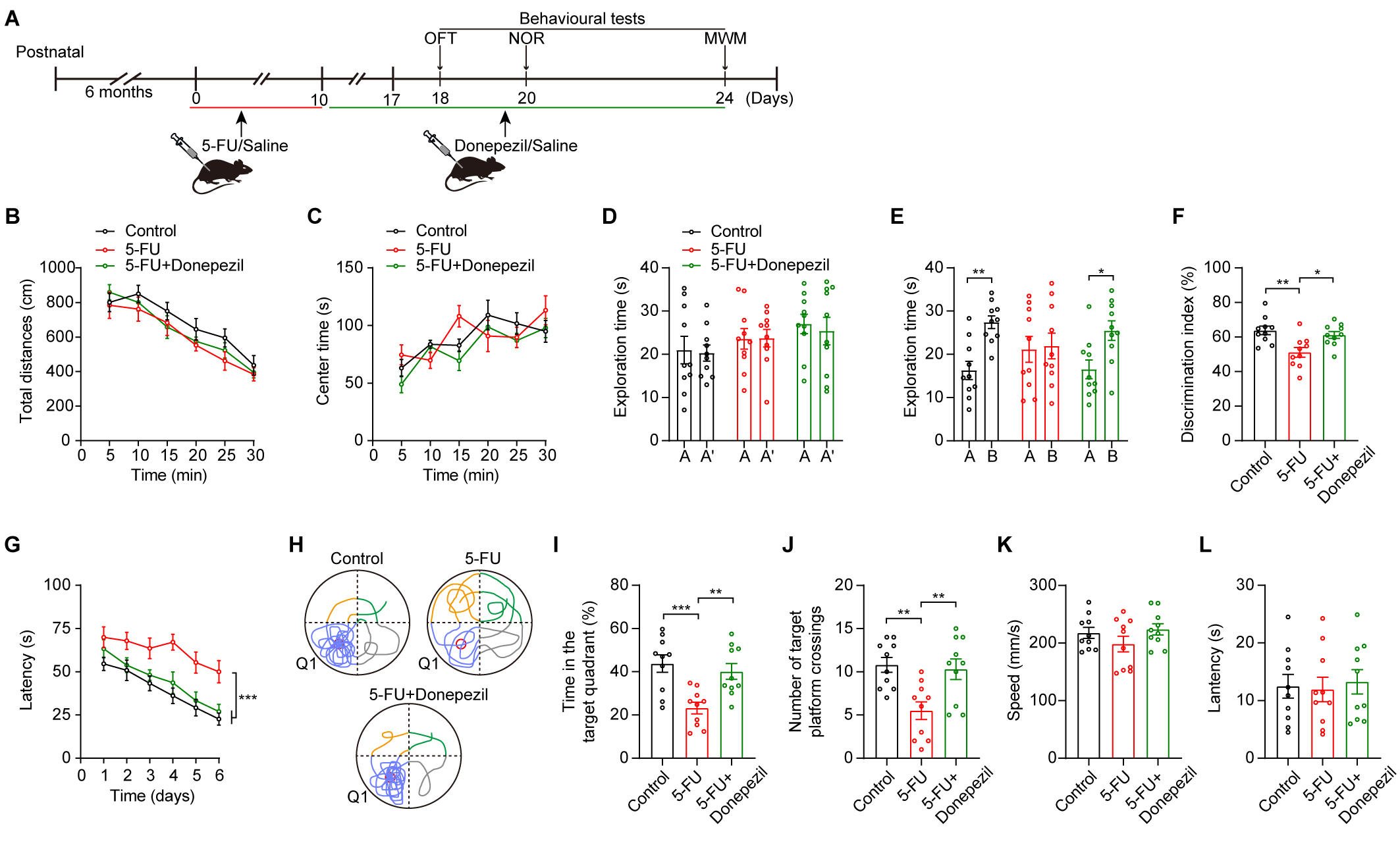

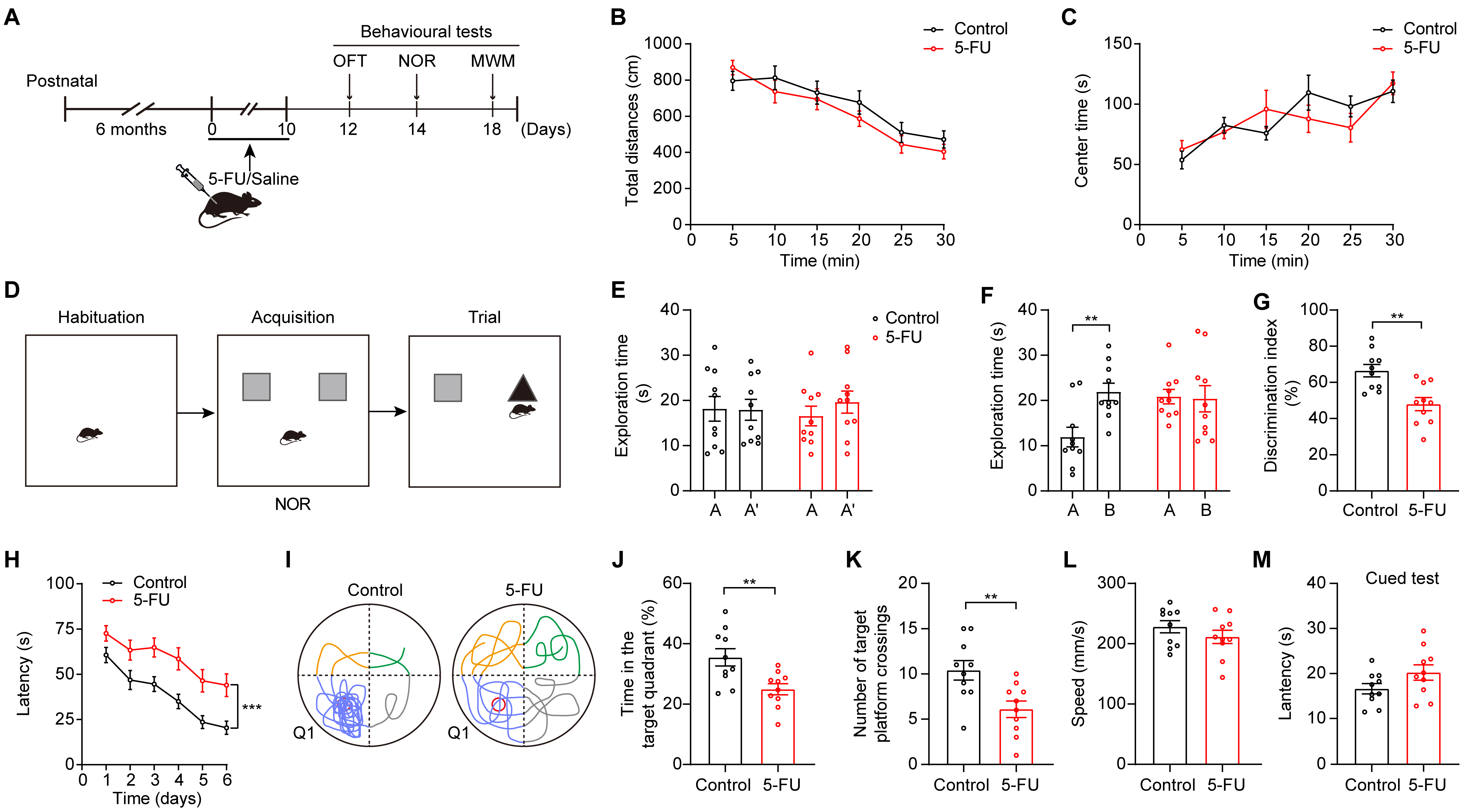

To examine cognitive function in mice after treatment, we treated mice with 5-FU (50 mg/kg) once daily for 10 consecutive days [25, 26]. After the administration of the chemotherapy drug, behavioral tests such as the MWM, OFT, and NOR tests were conducted (Fig. 1A). 5-FU treatment had no impact on mouse locomotor activity (Fig. 1B). There was no significant difference in the duration that the two groups spent in the center during the OFT, indicating that the administration of 5-FU did not affect the anxiety levels of the mice (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The administration of 5-FU impaired cognitive performance of

mice. (A) Schematic diagrams of the 5-FU treatment and behavioral tests. Created

with Adobe illustrator (CC 2014, Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). (B)

Effects of 5-FU on mouse locomotion (n = 10/group). (C) Effect of 5-FU on anxiety

levels. (D) Design of experiments for the Novel Object Recognition test. (E–G)

The duration of exploration during the learning phase (E), the duration of

exploration during 24-h retrieval assessments (F), and discrimination index of

novel object recognition (G) were quantified for mice across different

experimental groups. (H) The escape time required for relocating the platform

during testing (n = 10/group). (I) Exemplary patterns of swimming trajectories

were observed during the probe trial. (J) Times spent in Q1 during the test. (K)

The total number of platform crossings throughout the test. (L) Speed of movement

in the MWM. (M) Latency during the cued test. Data are displayed as mean

To assess cognitive performance related to 5-FU treatment, we performed

behavioral assessments, including NOR and MWM tests. During the NOR test, the

mice that received 5-FU exhibited a reduction in their 24-h item recall (Fig. 1D–G; Fig. 1F, p

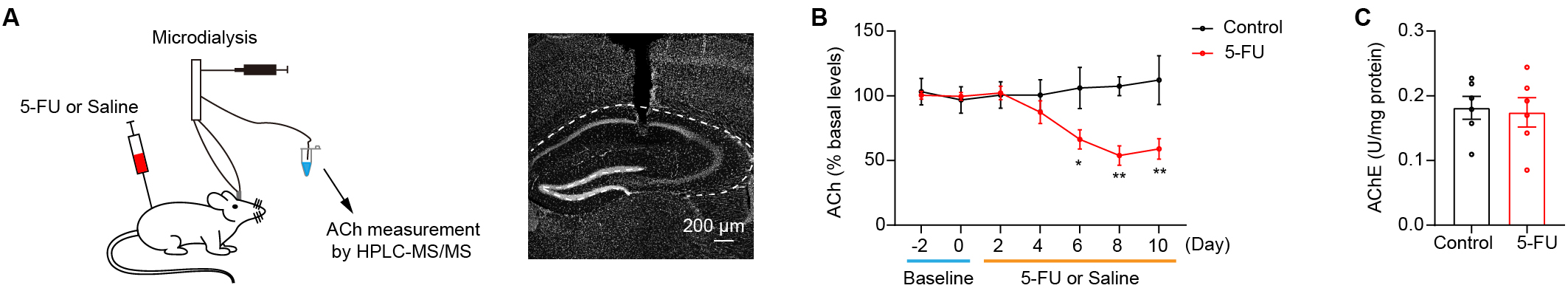

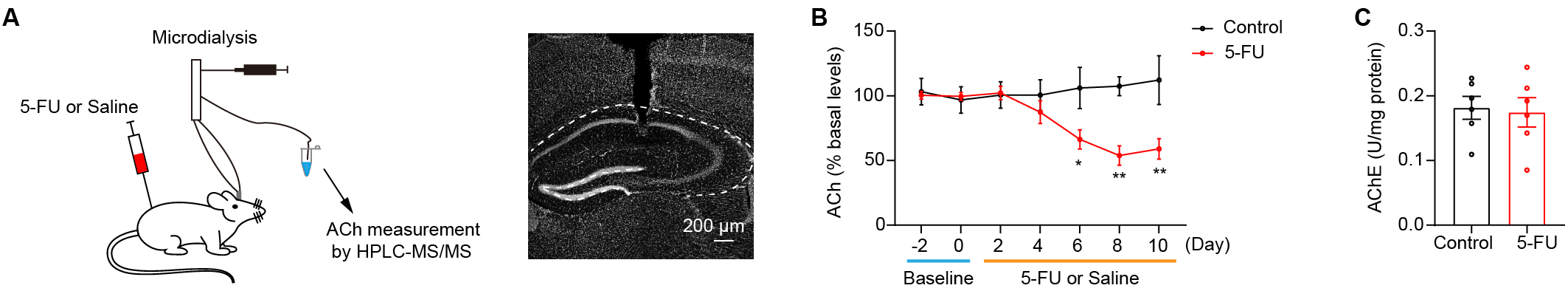

Decreased ACh levels in the hippocampus have been linked to cognitive

impairments [21, 30, 31, 32]. The present study sought to test whether the 5-FU

treatment reduced the ACh levels within the hippocampus. A microdialysis

component with HPLC-MS/MS was used to quantify extracellular ACh levels in the

hippocampal tissue during the 5-FU treatment (Fig. 2A). The data showed that mice

treated with 5-FU for 6 days had notably lower extracellular ACh levels within

the hippocampus than did the control group (Fig. 2B; Day 6 p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Hippocampus cholinergic transmission is attenuated in mice

treated with 5-FU. (A) Left: ACh levels in the hippocampus were determined by

microdialysis and analyzed via HPLC-MS/MS. Right: the position of the cannulae

and probe tracks. Scale bar = 200 µm. (B) ACh levels in the hippocampus

during 5-FU or saline treatment (n = 5–6/group). (C) The AChE activity in the

hippocampus after 10 days of drug delivery between the control and the 5-FU

groups (n = 6/group). AChE, acetylcholinesterase. * p

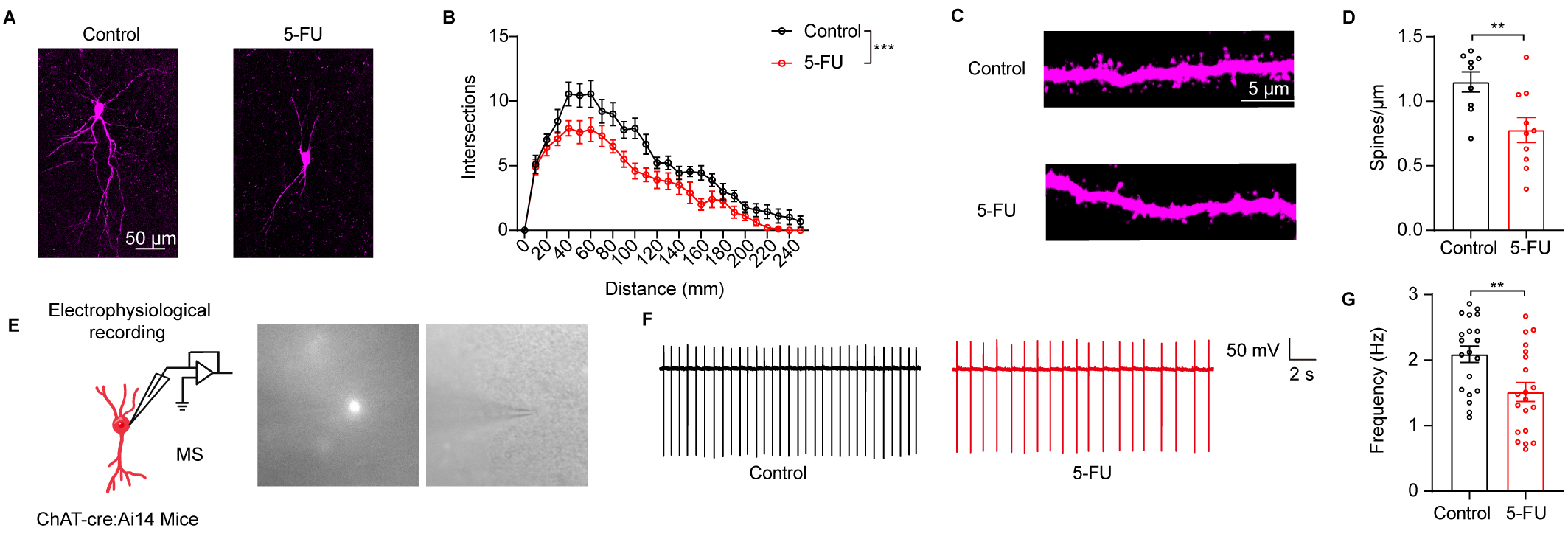

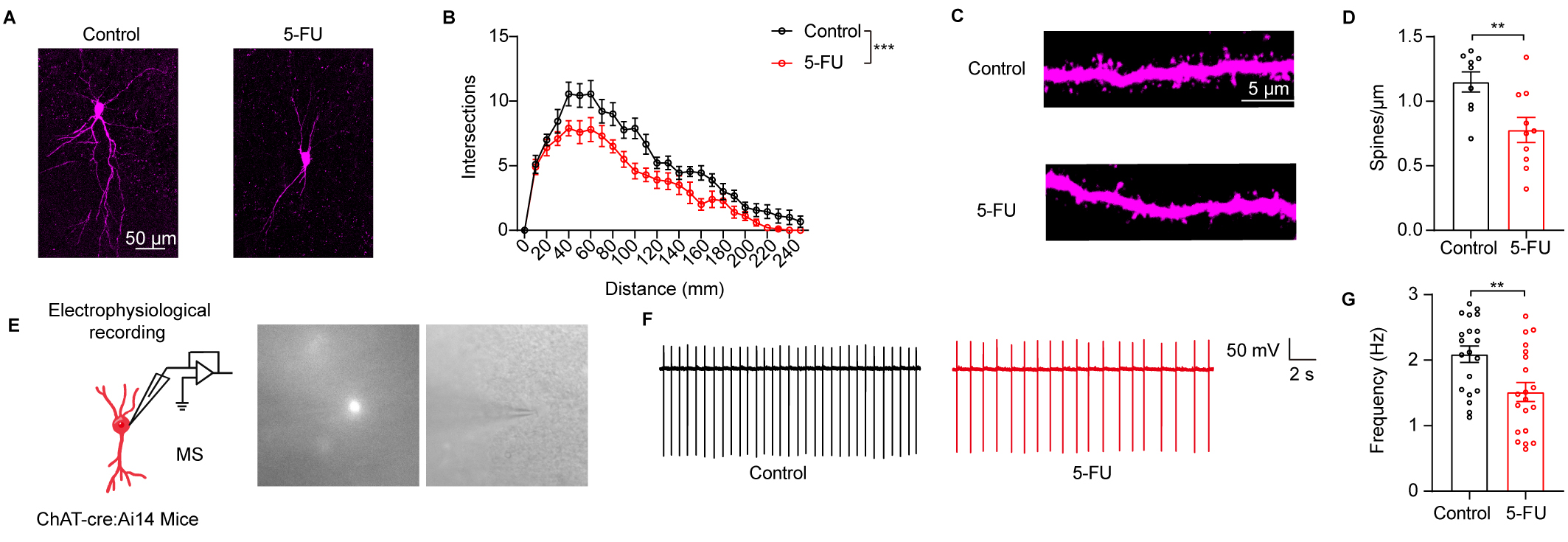

To determine whether 5-FU influenced neuronal functions, we evaluated the

dendritic structure of ChAT neurons in the MS. Markedly lower numbers of

dendritic branches were found in mice treated with 5-FU than in the control mice

(Fig. 3A,B, p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

5-FU treatment impaired the neuronal structure and activity of

cholinergic (ChAT) neurons in the medial septum (MS). (A) An illustration of the

MS ChAT neurons’ typical morphology across many groupings. (B) Sholl analysis

results (n = 9–10 neurons from three mice in each group). Scale bar = 50

µm. (C) An illustrative depiction of the neural dendrite segment from MS

ChAT that was used to examine dendritic spines. Scale bar = 5 µm. (D)

Determining the MS ChAT neurons’ spine number (n = 9–10 neurons from 3

mice/group). (E) Left: MS ChAT neuron preparation and electrophysiological

recording. Right: example of patch-clamp

recording of cholinergic fluorescent neuron under whole-cell configuration. (F)

Representative spontaneous firing traces of the MS ChAT neurons from control and

5-FU mice. (G) The spontaneous firing rate of the MS ChAT neurons was quantified

(n = 20 neurons from 4 mice/group). ** p

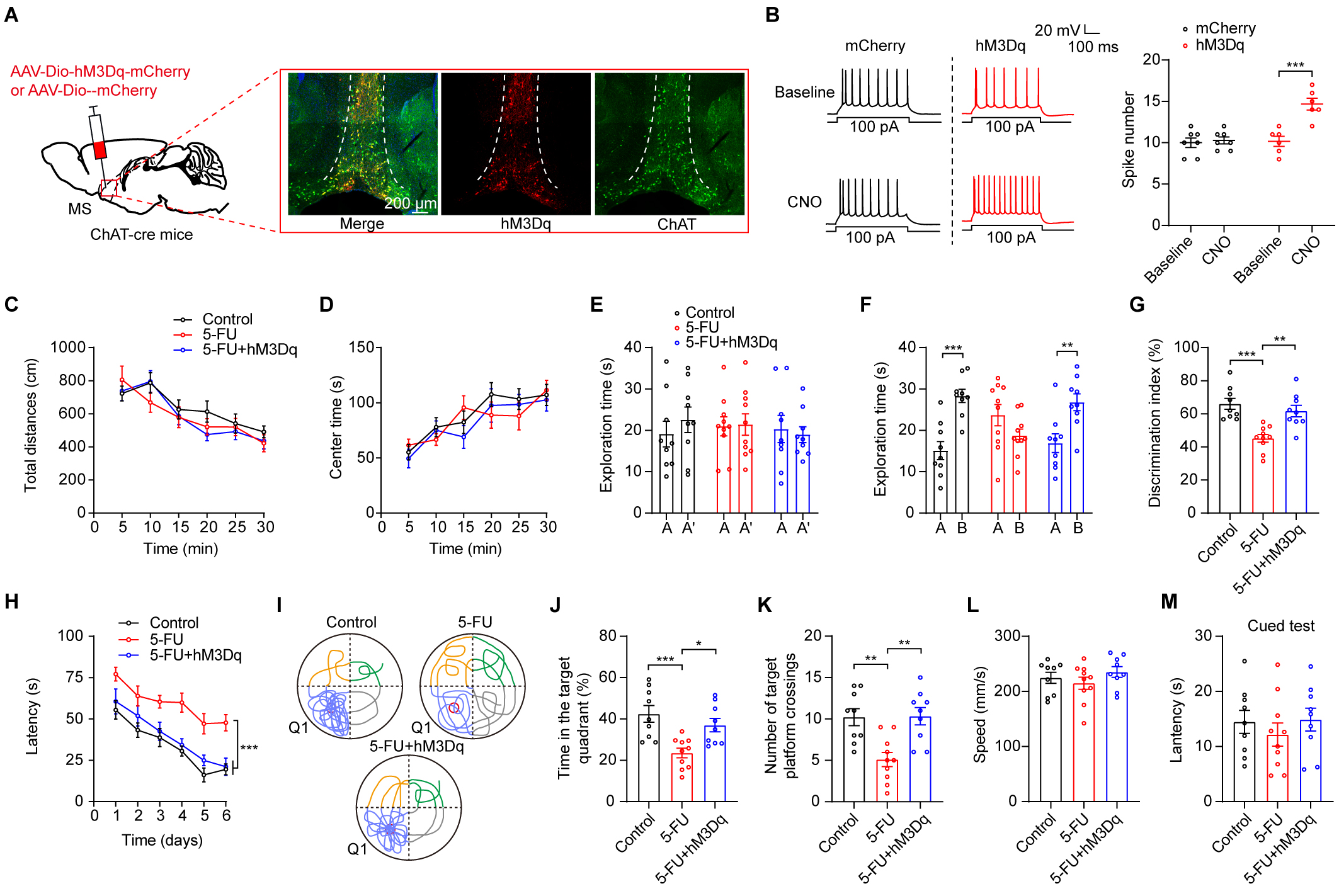

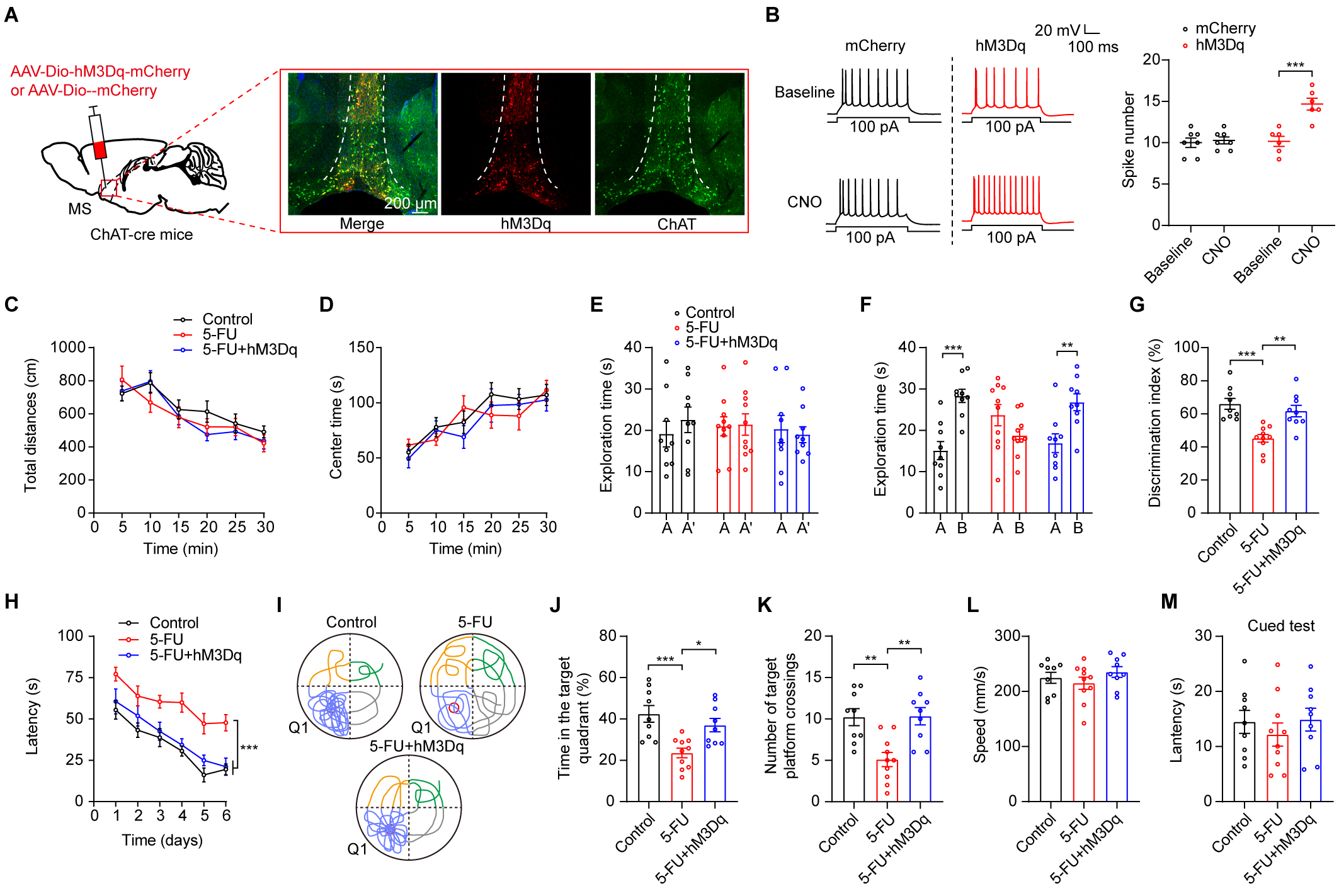

We assessed the effect of activating MS ChAT neurons on reduction of cognitive

function impairments that had been observed in 5-FU-treated mice. To simulate

clinical treatment administration and ensure prolonged activation of MS ChAT

neurons, we used chemogenetics techniques to stimulate ChAT neurons specifically.

Using clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) as an activator, we were able to successfully

activate MS ChAT neurons with the excitatory hM3Dq designer receptor by

stereotaxically delivering a Cre-dependent virus (AAV-EF1a-Dio-hM3Dq-mCherry)

into the MS region of ChAT-Cre mice (Fig. 4A,B, p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Chemogenetic stimulation of MS ChAT neurons improved the

compromised cognitive performance of 5-FU-treated mice. (A) Left: representation

of viral injection and optical fiber implantation site. Right: hM3Dq expression

in ChAT neurons in the MS. Scale bar = 200 µm. (B) Left: before and during

CNO perfusion (5 µM), typical traces show action potentials produced by a

100-pA current in MS ChAT neurons. Right: Quantification of 100-pA

current-induced action potentials hM3Dq expression neurons (n = 6–7). (C,D) The

locomotion (C) and central time (D) during OFT of mice (n = 9–10/group) in

different groups. (E–G) Times spent exploring during the learning phase in the

different groups (E), the duration of exploration over 24-hour retrieval tests

(F), and the NOR discrimination index (G) are shown. (H) During acquisition

training (n = 10/group), the escape time traveled to locate the platform. (I)

Swimming patterns during the probe trial. (J) Time spent in Q1 during the probe

trial. (K) Platforms crossings during the probe trial. (L) Swimming speeds. (M)

The cued-test latencies. AAV, adeno-associated virus; CNO, clozapine-N-oxide. * p

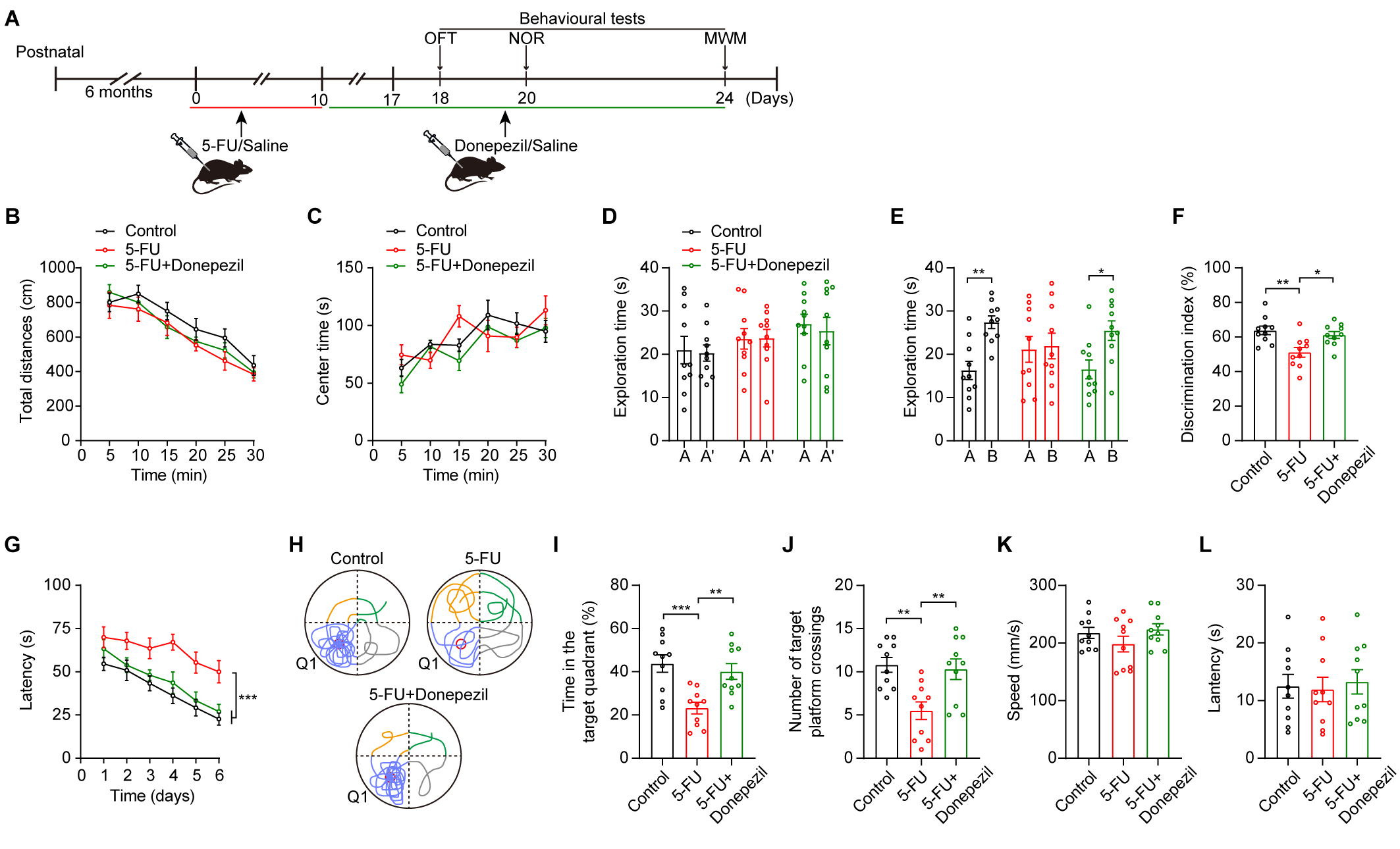

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) are extensively used in clinical

practice to treat cognitive impairments associated with neurodegenerative

diseases by elevating ACh levels [33, 34]. Donepezil, a clinically utilized AChEI,

was injected at a dose of 1.0 mg/kg, i.p. [28] to investigate its potential in

ameliorating cognitive impairments induced by 5-FU treatment (Fig. 5A). The

donepezil treatment did not affect the mice’s anxiety levels or movement (Fig. 5B,C). However, in mice treated with 5-FU, we found that administration of

donepezil ameliorated cognitive impairments (Fig. 5D–L; Fig. 5E control A vs

control B p

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Donepezil ameliorated cognitive impairments in 5-FU-treated

mice. (A) Schematic diagrams of the drug treatment and behavioral tests. (B,C)

The locomotion (B) and central time (C) during OFT of mice in various

experimental groups (n = 10/group). (D–F) Duration of exploration during the

learning phase (D), duration of exploration in the 24-h retrieval tests (E), and

NOR discrimination index (F) for mice in various experimental groups. (G) During

acquisition training, the escape time spent searching for the platform. (H)

During the probing trial, exemplary swimming trajectory patterns were noted. (I)

The duration allocated to Q1 in the probe trial. (J) The number of platform

crossings observed during the probe trial. (K) Swimming speeds in the MWM. (L)

Latency in the cued test. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s t-test (B–E,G),

One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s t-test (F,I–L). Data are shown as mean

We have shown that 5-FU treatment attenuated hippocampal ACh transmission by impairing the MS ChAT neuronal activity. Furthermore, we have shown that manipulations that elevate ACh levels in the hippocampus may present a promising therapeutic strategy for addressing chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairments.

As an antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent, 5-FU shows notable effectiveness against several forms of cancer, such as colorectal cancer and breast tumors [35]. However, cognitive impairments induced by 5-FU treatment have been observed in clinical studies [36, 37] and 5-FU treatment has been shown to have a negative impact on spatial and non-spatial memory in animals [16, 38]. The severity and duration of symptoms can vary among individuals, with many patients reporting cognitive changes both during and for several years after chemotherapy treatment [39]. Animal models have proven invaluable in further clarifying the mechanisms behind chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairments, which are not easily assessable in humans. Additionally, an animal study has contributed to shaping the future direction of clinical research [40]. Consistent with previous research [25, 38, 41], our findings demonstrated chemotherapy-induced impairments in both novel object recognition and spatial learning and memory in mice.

The processes underlying the cognitive toxicity of 5-FU treatment remain insufficiently understood. There are several hypothesized causes for “chemobrain”, such as direct neuronal injury, inflammation, oxidative damage, indirect chemical toxicity, and immunological-response induction [42]. The hippocampus is essential for maintaining cognitive function in humans and mice [43, 44]. Six days after 5-FU treatment, our mice showed decreased ACh levels. The levels of ACh primarily rely on its release from ChAT neurons and its degradation by AChE. Our results demonstrated that the administration of 5-FU had no discernible impact on the activities of AChE in the hippocampus. As regions such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and striatum are also involved in cognitive functions [45], further work is needed to detect the ACh levels in these regions after 5-FU treatment.

In addition to ACh levels, the neuronal structure and activity of ChAT neurons in the MS were impaired after 5-FU treatment. Consequently, we postulate that chemotherapy may induce damage to the mechanism for ACh release from ChAT neurons within the hippocampus. ACh in the hippocampus controls neuronal excitability, influences synaptic plasticity, affects synaptic transmission, and coordinates the firing rhythms of neuronal ensembles [20]. As a result, ACh modifies functional connectivity and response to internal and external inputs of hippocampal networks [19]. Therefore, decreased ACh levels within the hippocampus may lead to deficits in synaptic plasticity, which may underlie the cognitive impairments induced by 5-FU treatment. Although our research has shown that 5-FU treatment impairs the activity of MS ChAT neurons, the precise mechanism responsible for this effect remains unknown. The induction of inflammation and oxidative damage by 5-FU treatment necessitates further investigation into the specific pathways through which it affects the morphological and electrophysiological changes in MS ChAT neurons.

In addition, increased neurogenesis in the hippocampus dentate gyrus is linked to memory formation, and the production and survival of newborn hippocampus neurons are essential for spatial memory and learning [46]. Neurogenesis in mammals persists into adulthood; however, chemotherapy may interfere with this process and potentially lead to cognitive impairments [15, 38, 47, 48]. ACh transmission has been shown to regulate adult hippocampal neurogenesis [49]. A study of the hippocampus of adult mice showed direct innervation of immature neurons by ChAT neurons, controlling their survival and spatial patterns; in addition, using an Alzheimer’s disease model, they found spatial memory impairments were caused by the degeneration of hippocampal cholinergic synapses [23]. The impairments of MS ChAT neurons may result in deficits in the maturation and incorporation of new cells in the dentate gyrus, neuronal differentiation, and the survival of neural stem cells. Further research is required to determine whether enhancing the levels of ACh can mitigate the impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis in mice treated with 5-FU.

We found that 5-FU treatment results in deficits in ACh transmission in the hippocampus due to the impairment of MS ChAT neuron activity. The activation of MS ChAT neurons or administration of donepezil to elevate ACh levels effectively alleviated the cognitive impairments induced by 5-FU. These data may find potential applications in managing cognitive impairments caused by 5-FU chemotherapy treatment in cancer patients.

Data is available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

XWH, WJC and JLW designed the protocol. XWH, SQP and YQL carried out the experiments. XWH and SQP analysed the data. WJC and JLW wrote the manuscript. WJC and JLW revised the manuscript. WJC and JLW supervised the experimental progress. JLW supported the fundings. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All animal protocols and procedures discussed herein were approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Meizhou People’s Hospital (2023-F-09-01). The behavioral experiment adhered to the guidelines set by the Chinese Council on Animal Care, ensuring compliance with professional and ethical standards.

Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This work was supported by grants from the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022A1515011987) to JLW.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.