1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain (NP) is a prevalent condition, affecting approximately 10.3%

of individuals in the general population. Its incidence is notably higher in

specific populations such as elderly patients with herpes zoster (HZ), patients

with diabetes, and patients with cancer [1]. Studies indicated that 5–30% of HZ

patients develop postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) [2], with more than 30% of these

patients experiencing persistent neuralgia for more than 1 year. This chronic NP

significantly reduces the quality of life, leading to sleep disorders, anxiety,

depression, decreased physical function, and even debilitation [3]. Furthermore,

it increases the economic burden on patients [4]. Consequently, PHN has become

one of the most common chronic diseases affecting the quality of life and mental

health of the elderly.

Indeed, a widely recognized contributor to NP is nerve injury. Neurons, the

functional units of the nervous system, are capable of sensing stimuli,

transmitting excitation, and activating corresponding brain regions to produce

sensations. PHN, a typical form of NP associated with nerve injury, is also

related to aging, immune deficiency, and genetic factors [5, 6, 7]. Nerve injury

promotes the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines [8], activation of glial

cells [9], and reduction of peripheral sensory nerve fibers [10, 11].

Subsequently, the abnormal expression of various ion channels related to pain

signaling pathways in neurons leads to central sensitization, which is the

primary cause of increased neuronal excitability and NP [12, 13, 14, 15]. However,

although most adults infected with the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) experience

some degree of nerve injury, not all HZ is accompanied by PHN, which might be a

hint of the decline in immunity [16]. Therefore, events secondary to nerve

injury, such as the release of chemokines by peripheral neuron cell bodies and

Schwann cells, are likely to induce immune cell infiltration, further

contributing to the development of NP [17, 18, 19]. From this perspective, nerve

injury serves as the backdrop for the occurrence of PHN.

Although rodent models for exploring the pathogenesis of PHN, such as rat models

induced by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and VZV, have been successfully

constructed to the current time, there are differences in the pathways of PHN

progression from viral latency to activated infection between these models and

humans. Notably, so far, there have been no reports of constructed animal models

that mimic the VZV reactivation process. Therefore, the development of a more

reliable viral reactivation animal model that exhibits PHN-like herpetic pain is

undoubtedly a major challenge we currently face. The pathogenesis of PHN is

associated with nerve injury, and the generally accepted academic mechanism for

the pathogenesis of PHN is central and peripheral sensitization, including

abnormal activation of glial cells and dysfunction of ion channels. Meanwhile,

although the pathogenesis of other NP may vary depending on their etiology,

pathological processes such as nerve injury and abnormal ion channel function are

always present. Given this, the study of other NP can undoubtedly provide a

valuable reference for PHN. PHN, as a chronic neuralgia triggered by VZV invasion

of nerves, is essentially, like all neuralgia, closely related to nerve injury,

whether this injury is caused by viral infection, immune response, or

mechanochemical factors. However, our study of the role of cytokines in PHN

remains limited and clinical evidence seems insufficient due to the many

challenges still facing the construction of current animal models of PHN. To fill

this gap, we drew on other NP research findings to provide further insights into

the pathogenesis of PHN when exploring the role of cytokines in PHN.

The pathogenesis of PHN remains under investigation. A growing body of evidence

has enhanced our understanding of the role of inflammatory mediators, such as

interleukins (ILs), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-), ATP, and

chemokines, in the mechanisms of NP [17, 20, 21, 22]. However, systematic and

comprehensive studies on the changes and mechanisms of cytokines in the

pathogenesis of PHN are still lacking. This paper reviews the peripheral and

central mechanisms of PHN by which cytokines mediate pain, and also discusses the

signaling pathways involved in its pathogenesis.In this paper, the identification

of cytokines and neuroglial cells as potential therapeutic targets for PHN is

emphasized, along with suggestions for future research avenues focusing on PHN

treatment.

2. Nerve Injury

PHN is a prevalent type of NP in clinical practice and remains one of the most

challenging chronic pain to manage. It is triggered by infection with VZV, a

neurotropic herpes virus that lies dormant in human peripheral sensory ganglia.

Reactivation of VZV is related to cellular immunity, which is typically effective

in preventing such reactivation. However, compromised immune responses,

especially in the elderly, facilitates VZV reactivation from dorsal root ganglia

(DRG) latency, spreading along peripheral nerves to the skin [23, 24]. During

viral replication, the immune system releases inflammatory mediators, including

cytokines and chemokines [25]. This leads to inflammation, hemorrhagic necrosis,

and neuronal loss in the affected DRG [26, 27], resulting in nerve damage. The

inflammatory changes following nerve damage lead to the infiltration of immune

cells, which are consistent with observations in other animal models of

peripheral nerve injury [28, 29, 30, 31]. This causes spontaneous firing of peripheral

neurons, lowered activation thresholds, and amplified incoming neural signals,

manifesting as neuronal dysfunction and ectopic discharges [12, 13, 14, 25].

Interestingly, in the chronic constriction injury (CCI) model [32], thermal

hyperalgesia can still occur when the ligature is loosely applied without causing

actual mechanical damage. This suggests that the inflammatory response and the

release of inflammatory mediators, rather than nerve injury itself, are key to

maintaining NP. Inhibiting the inflammatory response can reduce hyperalgesia

[33], where the injection of exogenous inflammatory mediators can induce pain

[34], supporting the idea that inflammatory mediators play a role in mediating

NP. These mediators encompass cytokines, interferons, tumor necrosis factors,

chemokines, and colony-stimulating factors. Their production is from immune cells

[35] and from glial cells [18, 36, 37, 38], providing a structural basis for the

mechanism by which inflammatory mediators mediate NP. Thus, VZV reactivation in

PHN serves as the etiological factor for nerve damage, with cytokines playing a

crucial role in mediating NP.

3. Cytokines

3.1 Overview of Cytokines

Associated with PHN

Cytokines are proteins with low molecular weight that possess diverse biological

functions. These proteins are predominantly secreted by immune cells.

Additionally, other cell types, including keratinocytes, dendritic cells in the

skin, and neuroglia within the central nervous system (CNS), also contribute to

cytokine secretion [39, 40, 41]. The release of these cytokines is typically

triggered by injury and inflammation [42]. Cytokines exert their biological

functions by binding to specific receptors, and regulating cell growth,

differentiation, and tissue repair. They are particularly important in stress

reactions such as injury, pain, and infection. The properties of cytokines are

related to the microenvironment and most have dual effects in different

situations [43]. IL-1 promotes neuronal sensitization [44, 45].

Pro-inflammatory cytokines include IL-1, IL-6, IL-18 and TNF-. ILs

mainly participate in the proliferation, differentiation, and activation of

immune cells, whereas TNF- can activate cytotoxic T cells and promote

the production of other cytokines, collectively enhancing the inflammatory

response. Anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10, soluble IL-2 receptor

(sIL-2R) antagonists, and TNF-binding proteins, primarily inhibit inflammation to

prevent excessive inflammatory responses that could damage the body. However,

IL-10 additionally facilitates the activation and expansion of B cells [46],

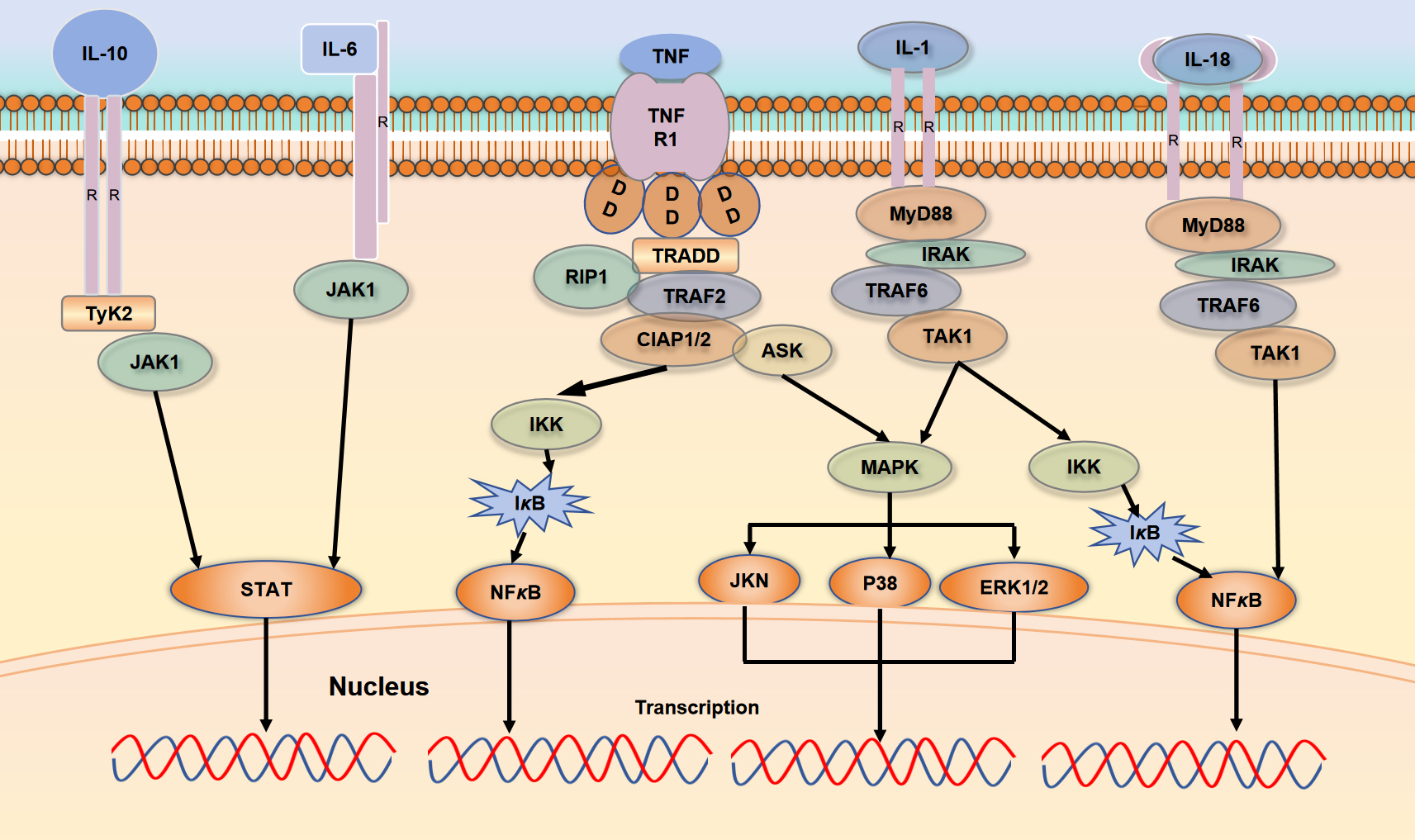

thereby sustaining autoimmune responses (Fig. 1 shows the inflammatory response

of immune cells). Under pathological conditions, an imbalance in cytokine levels

can contribute to disease progression. For instance, following nerve injury,

cytokines secreted by immune cells exert direct effects on neural signaling by

binding to homologous receptors on neurons, microglia, and astrocytes within the

spinal cord, DRG, and brain. Neuronal activation is not solely dependent on

receptor-mediated interactions and cellular contacts but is also regulated

through a broader network influenced by cytokine activity [47]. Consequently,

these cytokines establish a communication network between immune cells and

neurons, involved in the modulation of neural responses [48].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The roles of immune cells and glial cells in amplifying the

inflammatory response during nerve injury. Glial cells in the DRG and immune

cells secrete inflammatory mediators. T cells, macrophages, and monocytes have

been shown to infiltrate tissues infected by viruses. These cytokines promote the

activation of glial cells and increase neuronal excitability. The interactions of

neuroimmune and glial cells accelerate nerve injury, and promote pain generation. The figure was drawn using WPS office (12.1.0.20305, Kingsoft Office Software Co., LTD., Kowloon, Hong Kong, China). CXCL, C-X-C motifchemokine lingand; DC, dendritic cell; DRG, dorsal root ganglia;

IL, Interleukin; TNF-, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Recent research indicates that PHN is often accompanied by an inflammatory

response [10], evidenced by the presence of various cytokines at the injury site,

adjacent areas, and even in the plasma [49, 50]. These include TNF-,

ILs, interferon gamma (IFN-), various chemokines, and oxidative

stress-related factors. Collectively, these factors are pivotal in the onset and

advancement of NP. Among them, TNF-, IL-1, IL-6, IL-18, and

IL-10 have been more extensively studied in relation to PHN. Other cytokines,

such as IFN-, IL-2, IL-17 and IL-23, have been less well studied in

relation to PHN. In untreated animal models [34, 51, 52, 53, 54], intrathecal injections

of cytokines such as IL-1, IL-18, TNF, and IL-6 have been observed to

directly induce pro-nociceptive effects, leading to hyperalgesia. Cytokines are

both important members of the immune system and mediators of pain-related

signals. Specifically, TNF-, IL-1, and IL-6 have been

implicated in the development of NP across animal models, including PHN. These

cytokines, produced by both neuroglia and immune cells, share common functions

such as mediating pain-related cation channel expression, amplifying inflammatory

responses, and activating glial cells. In the context of nerve injury,

inflammatory cytokines act on nociceptor terminals to initiate pain pathways

[55]. Additionally, neuronal activation triggers reciprocal cytokine release,

further promoting inflammation. Prolonged inflammation leads to altered sensory

nerve fiber signaling, which persists even after inflammation and injury have

healed. In summary, it can be hypothesized that cytokines are closely related to

the development PHN. This paper explores the signaling pathways of

TNF-, IL-1, IL-6, IL-18, and IL-10, elucidating their roles in the

pathogenesis of PHN.

3.2 Signaling of Cytokines

3.2.1 Overview of TNF- Signaling

TNF- is intricately involved in the pathogenesis of NP. This cytokine

is primarily synthesized by macrophages and acts as a versatile systemic

inflammatory mediator. Structurally, TNF- comprises a signal peptide

and two domains, existing in monomeric, dimeric, or trimeric forms, with dimers

exhibiting the highest biological activity. Two different receptors, TNF receptor

1 (TNFR1) and TNFR2, are responsible for mediating TNF- signaling [56].

TNFR1 is broadly expressed and can induce apoptosis, while TNFR2 is predominantly

found on specific cell types like immune and endothelial cells, involved mainly

in anti-apoptotic signaling. TNF- influences a variety of biological

processes through its interaction with receptors TNFR1 and TNFR2. Through its

interaction with TNFR1, TNF- triggers the activation of the

mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor kappa B

(NF-B) pathways, initiating downstream signaling processes [57, 58, 59]. On

the other hand, when TNF- binds to TNFR2, it recruits TNF

receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) along with cellular inhibitors of apoptosis

proteins 1 and 2 (cIAP1/2), thus activating the non-canonical NF-B

pathway (Table 1, Ref. [60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66]).

Table 1.

Cytokines, receptors and signaling pathways.

| Cytokines |

Receptors |

Signaling Pathways |

References |

| TNF- |

TNFR1 |

MAPK |

[65] |

| NF-B |

[66] |

| TNFR2 |

Non-classical NF-B |

[60] |

| IL-1 |

IL-1R |

NF-B, MAPK |

[61] |

| IL-6 |

IL-6R |

JAK-STAT3 |

[62] |

| IL-18 |

IL-18R |

NF-B |

[63] |

| IL-10 |

IL-10R |

JAK-STAT |

[64] |

IL-1R, IL-1 receptor; JAK, Janus kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-B, nuclear factor-kappa B; STAT, signal transducers and activators of transcription.

3.2.2 Overview of IL-1 Signaling

IL-1, another cytokine, contributes to the initiation and advancement

of NP. IL-1 is an inactive precursor peptide that undergoes cleavage and

activation by IL-1-converting enzyme caspase-1 during inflammation,

leading to its extracellular secretion [67]. IL-1 initiates signal

transduction primarily through the IL-1 R-associated kinase

(IRAK) pathway. Upon binding, IL-1 forms a heterotrimeric complex with

IL-1R type I (IL-1R1) and IL-1R accessory protein (IL-1RAcP). This interaction

triggers the activation of IRAK4, resulting in IRAK4 autophosphorylation and

phosphorylation of IRAK1 and IRAK2. Subsequently, TRAF6 is recruited and

activated, which then activates members of the MAPK kinase kinase family. This

cascade leads to NF-B-inducing kinase phosphorylation, facilitating

nuclear translocation of NF-B and subsequent regulation of gene

expression [68]. IL-1 signaling, similar to TNF-, activates

both the NF-B and p38-MAPK pathways, promoting the increased expression

of genes such as IL-6, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, cyclooxygenase-2,

IL-1, and IL-1 [61].

3.2.3 Overview of IL-6 Signaling

IL-6 is a small molecular weight protein secreted by various immune cells. It

transmits signals via the ligand-binding IL-6R alpha (IL-6R) and the

signaling component gp130 (CD130) [69]. IL-6 signaling is primarily mediated

through three main pathways: first, IL-6 binds to its receptor (IL-6R) to form a

complex. This complex subsequently interacts with gp130, which activates

intracellular signal transduction, ultimately leading to downstream signaling

cascades and gene expression. sIL-6R binds to IL-6 and forms a complex with

gp130, initiating signal transduction. Additionally, the interaction between IL-6

and the IL-6R-gp130 complex initiates signal transduction via Janus

kinases (JAKs) and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs),

which results in STAT3 phosphorylation, subsequent transcriptional activation in

T cells, and the triggering of diverse biological effects [62].

3.2.4 Overview of IL-18 Signaling

IL-18 is a protein that mediates its action through a receptor belonging to the

IL-1R family. The IL-18R on neurons and glial cells activates important signaling

pathways. IL-18 binds to IL-18R, which then binds to IL-18R to

form a trimer [70, 71, 72, 73, 74]. The intracellular domain of IL-18R includes a Toll/IL-1R

homology (TIR) domain, which is the same as that in Toll-like receptors. This TIR

domain enables MyD88 to attach and relay signals into the cell. IL-18 activates

the transcription factor NF-B [63] and activator protein-1 (AP-1)

through signaling molecules such as MyD88, IRAK, and TRAF6 (Table 1).

3.2.5 Overview of IL-10 Signaling

IL-10 exhibits analgesic effects and is secreted and recognized by a range of

immune cells. Its main function in vivo is to suppress inflammation by

downregulating the production of various pro-inflammatory factors. The functional

IL-10R complex comprises a tetramer with two ligand-binding subunits and two

auxiliary signaling subunits [75]. The canonical IL-10 signaling pathway involves

the JAK/STAT pathway (Table 1) [64]. IL-10 binding to the extracellular domain of

IL-10R1 triggers the phosphorylation of JAK1 and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), which in turn activates

the transcription factor STAT3. Furthermore, IL-10 reduces NF-B

activation by diminishing its DNA binding ability and inhibiting the activity of

IB kinase. Simultaneously, IL-10 activates AP-1 and NF-B,

promoting the differentiation of CD8+ T cells. In monocytes, IL-10 activates p85

triiodophosphate and p70 S6-kinases. However, blocking these pathways affects the

proliferation-regulating activity of IL-10 but not its anti-inflammatory effects.

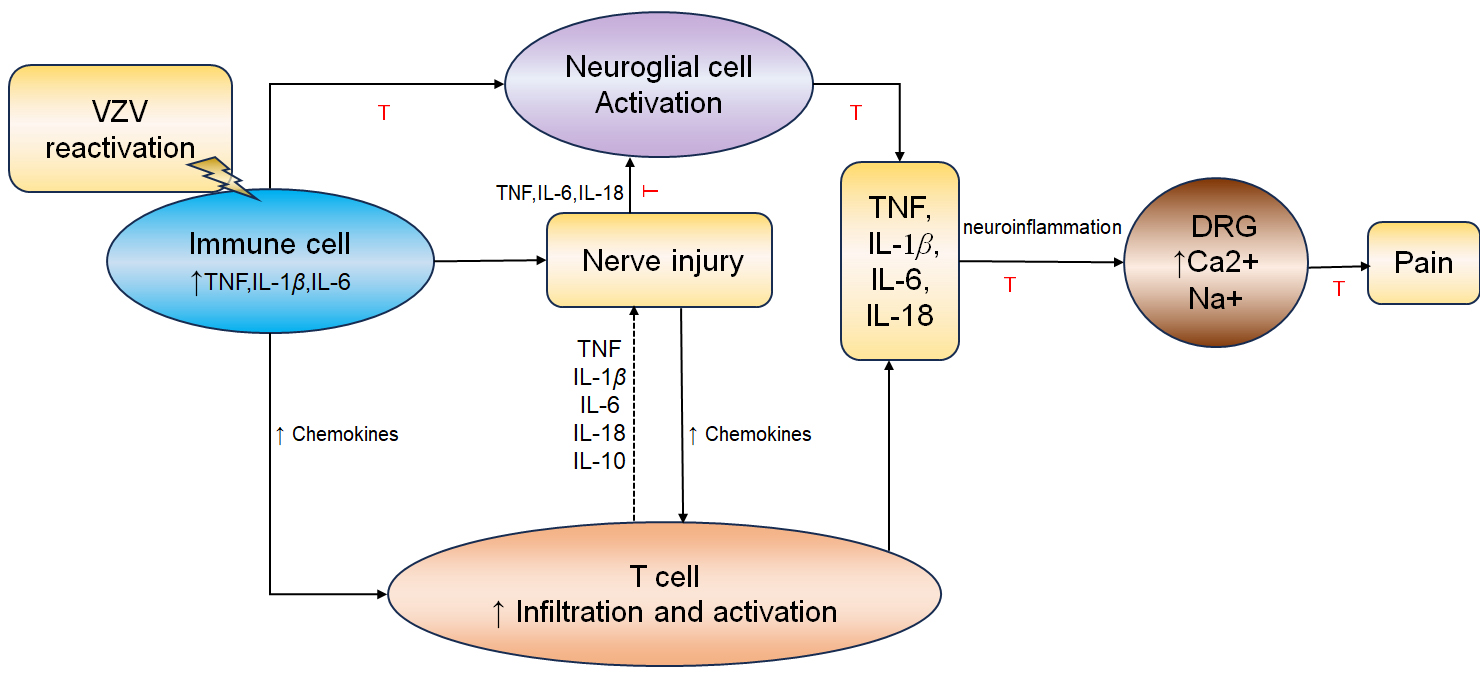

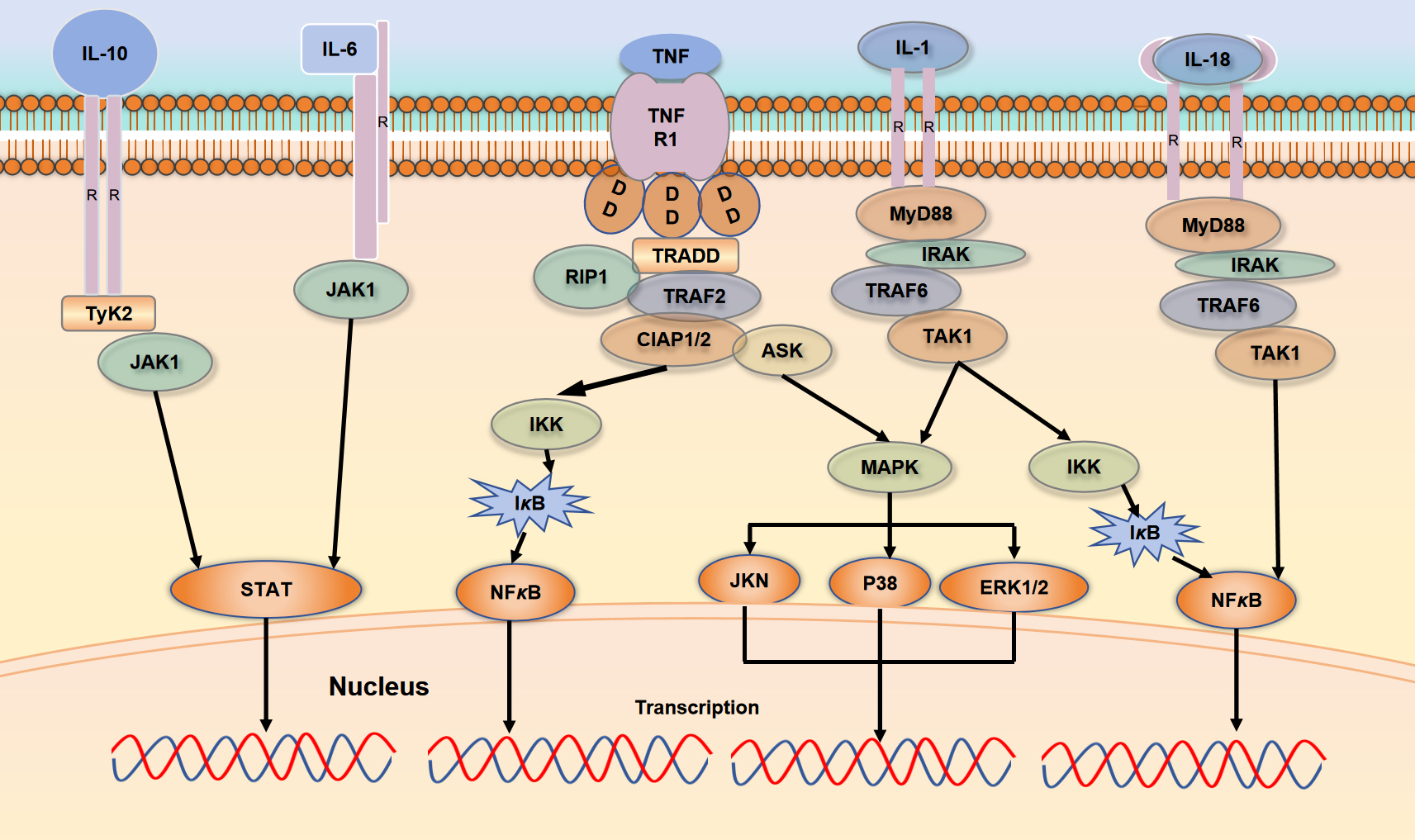

While these cytokines exhibit specificity in their biological functions

depending on the microenvironment, they share common downstream signaling

pathways. Notably, the MAPK and NF-B signaling pathways play a

significant role in pain sensitization, the expression of cation channels, and

the processes of neuroinflammation. The activation of JAK enhances the

sensitivity of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), leading to

peripheral sensitization. TNF- is critical for Na+ channel expression

via the p38-MAPK pathway, which simultaneously stimulates the production of

TNF- by microglia. IL-1 influences pain transmission by

modulating ion channels, including TRPV1 and the voltage-gated sodium channel

alpha subunit 9 (Nav1.7), through activation of the NF-B and p38-MAPK

systems. IL-6 induces JAK and protein kinase C (PKC) activation, contributing to

chronic pain. IL-18 promotes inflammation and increases pain sensitivity through

NF-B transcription. IL-10 may exert its effects by modulating these

signaling pathways (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

TNF-, IL-1, IL-6, IL-18, and IL-10

exerts various biological effects through their interactions with specific

receptors. Both TNF- and IL-1 engage with their respective

receptors, activating the NF-B and MAPK signaling pathways; IL-6 and

IL-10 activate the JAK/STAT pathway upon receptor binding, while IL-18 binds to

its receptor to activate the NF-B pathway. The figure was drawn using WPS office (12.1.0.20305, Kingsoft Office Software Co., LTD., Kowloon, Hong Kong, China). TNFR1, tumor necrosis factor

receptor 1; TRADD, TNFR1-associated DD proteins; TRAF2, TNFR associated factor 2;

TyK2, tyrosine kinase 2; IKK, IκB kinase; RIP1, receptor interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1; CLAP, caspase recruitment domain-containing protein; ASK, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase; MAPK, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase; ERK, extracellular signal regulated kinase; TAK1, transforming growth factor β activated kinase 1; IRAK, interleukin receptor associated kinase.

4. The Role of Cytokines in PHN

Immune cells and glial cells produce a range of cytokines that contribute to

both peripheral and central sensitization. Cytokines sustain pain signaling by

influencing injury receptors and/or central spinal cord neurons. Cytokines

upregulate the expression of pain-related cation channels, including Nav1.3,

Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Ca2+, and to activate neuroglial cells. Increased levels of

TNF- , IL-6, and IL-1, as well as other inflammatory

mediators, have been observed at the site of nerve injury and in adjacent areas.

Low concentrations of cytokines promote neuronal survival and growth and favor

post-injury nerve repair, whereas high concentrations of cytokines induce

neuronal apoptosis. The peripheral ends of injury receptors form tree-like

structures in tissues and organs [76]. These sites are in close proximity to

keratinocytes and immune cells and contribute to immunomodulation of injury

receptor function. In the context of high-frequency afferent input resulting from

tissue damage, a cascade of cytokines targets the ends of sensory nerve fibers

known as injury receptors. This interaction initiates the activation of pain

pathways, leading to neuronal activation and subsequent reciprocal stimulation of

various cytokine-producing cells [55]. Notably, prolonged inflammation alters

injury sensory processing, which persists even after inflammation and wound

healing, creating a “neuropathic” like phenotype. In the CNS, the types of

glial cells include astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia. Among them,

astrocytes and microglia have been the focus of extensive research in the context

of NP. It has been proposed that the p38-MAPK system can be activated by spinal

astrocytes to promote pain sensitization [77]. Moreover, astrocytes regulate

neuroplasticity [78]. Following inflammation, activated microglia undergo

transformation into macrophage-like cells [79] that release cytokines such as

TNF-, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-18, affecting synaptic signaling and

pain transmission via the p38-MAPK system [80, 81, 82]. Cytokines released from glial

cells at the spinal cord level can induce pain secondary to neuronal

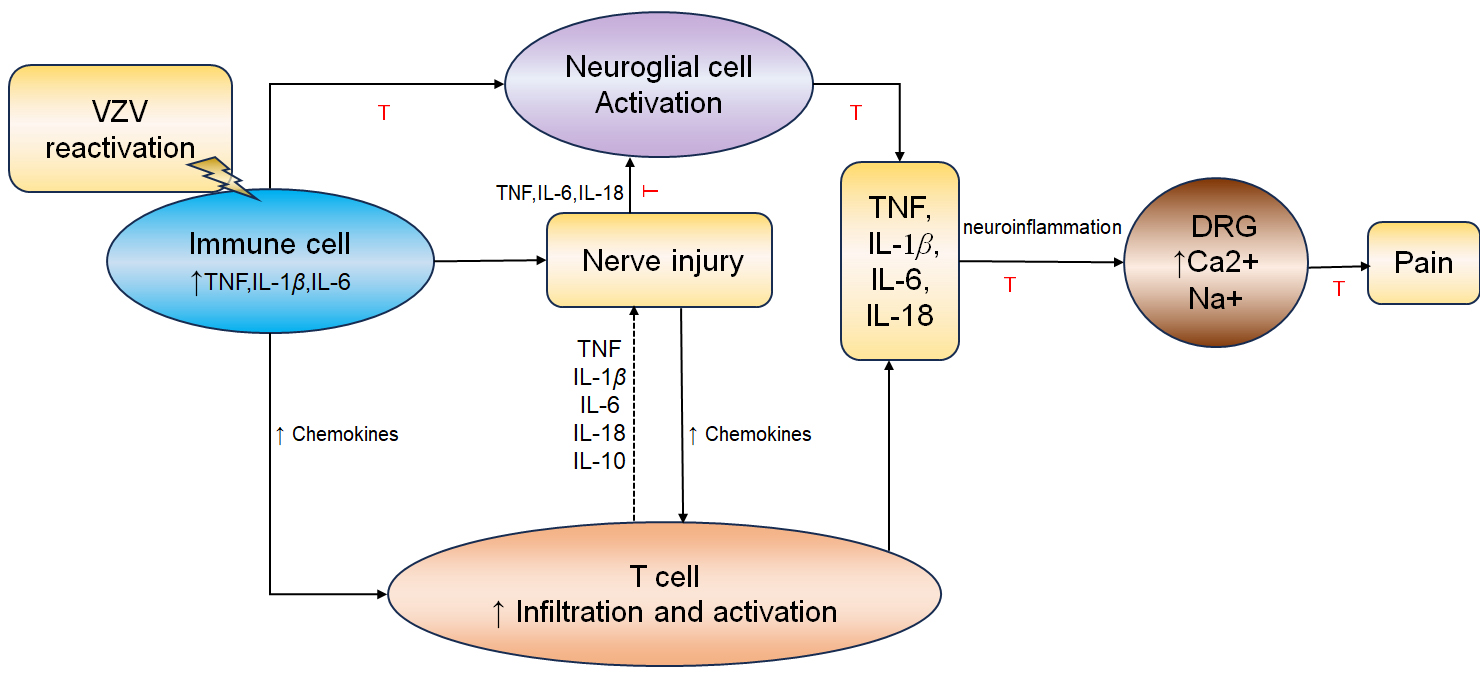

sensitization (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of major interrelationships leading to

nerve injury and pain. Upon VZV reactivation, immune cells secrete inflammatory

mediators, including TNF, IL-1 and IL6, as well as chemokines. This

inflammatory environment results in activation of glial cells and infiltration of

immune cells, further amplifing the inflammatory response. These inflammatory

cytokines, particularly TNF and IL-1, induce the expression of

pain-related cation channels in the DRG. This may lead to peripheral and central

sensitization, promoting NP. Red inhibitory lines indicate possible options for

targeted drug interventions. The figure was drawn using WPS office (12.1.0.20305, Kingsoft Office Software Co., LTD., Kowloon, Hong Kong, China). NP, neuropathic pain; VZV, varicella-zoster virus.

4.1 TNF-

In a meta-analysis study [83], TNF- levels were evaluated in the body

fluids of 113 participants, revealing higher TNF- levels in patients

with PHN compared to those who did not develop PHN after HZ. In a mouse model of

PHN induced by HSV-1, elevated TNF- levels were linked to PHN [12, 25].

These findings indicate that increased TNF- levels are linked to the

occurrence of PHN. Strangfeld et al. [84] observed an increased risk of

HZ with the use of TNF- inhibitors [85]. Interestingly, among patients

who developed HZ while using TNF- inhibitors, there was a lower

subsequent incidence of PHN, suggesting a potential role for TNF- in

PHN development. An experimental study has demonstrated that intrathecal

injection of exogenous TNF- can promote pain-induced hyperalgesia and

mechanical allodynia [34]. Conversely, TNF- inhibitors administered via

the same route can alleviate chronic pain [86]. This further confirms the crucial

role of TNF- in the pathogenesis of PHN. Consequently, TNF-

inhibitors emerge as promising candidates for the management of chronic pain

associated with PHN.

At low concentrations, TNF- promotes neuronal survival and growth,

whereas at high concentrations, TNF- induces neuronal apoptosis. In the

CCI model of rat sciatic nerve-induced NP, TNF- expression is detected

at the injury site [87]. Similar results have been observed in biopsies of human

NP lesions [88]. Exogenous TNF- injected into the DRG of CCI roots

causes ectopic pain, suggesting that the cause of NP is not the nerve injury

itself, but rather the action of inflammatory mediators following nerve injury

[28, 32]. In NP models following nerve injury, TNF- plays a pivotal role

in activating other cytokines [89]. TNF- binds to its receptors and

promotes the activation of inflammatory cells via NF-B, triggering an

inflammatory cascade [90]. TNF- binds to its receptor and activates the

NF-B signaling pathway to mediate aberrant expression of voltage-gated

Na+ channels (VGSCs) or Na+ currents [91, 92]. A study has shown that exogenous

TNF- administered around nerve leads to persistent mechanical allodynia

[90]. Zang et al. [92] demonstrated that TNF- induces the

upregulation of Nav1.3 expression in the DRG by activating NF-B, and

intrathecal injection of an NF-B inhibitor significantly alleviates

mechanical allodynia induced by the perisciatic injection of recombinant rat

TNF-. This indicates that TNF- mediates the expression of

VGSCs in the DRG via the NF-B system, contributing to the development

of NP [93, 94, 95]. Furthermore, TNF- enhances membrane cation conductance

in a non-voltage-gated manner, resulting in overall neuronal hyperexcitability,

further exacerbates NP [95].

TNF- is involved as a pro-inflammatory cytokine in the interaction

between neuroimmune cells and glial cells in sensory ganglia and is essential for

the promotion of PHN [96, 97]. Following ischemic, inflammatory, or traumatic

nerve tissue damage, TNF- rapidly increases in regions such as the

spinal dorsal horn, locus coeruleus, and hippocampus [98, 99, 100, 101]. TNF-

mediates the central mechanisms of NP through neuroglial cells.

Immunofluorescence staining has demonstrated the presence of TNF- on

the surface of astrocytes. TNF-, through G protein-coupled receptor

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4, triggers the production of IL-1, IL-6, and ATP.

These substances increase neuronal activity, and contribute to NP [80, 102]. The

TNF/TNFR1 signaling pathway contributes to NP by downregulating inward rectifying

K+ channels (Kir4.1) in astrocytes, disrupting K+ homeostasis. Microglial cells

have been shown to participate in the pathogenesis of NP [103, 104]. Following

nerve injury and inflammation [80, 105, 106, 107, 108], activated microglia secrete

pro-inflammatory cytokines mediated by the p38-MAPK system including

TNF-, IL-1, IL-6, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2, and C-X3-C motif

chemokine ligand 1, affecting synaptic signal transmission and pain transmission.

TNF- promotes Na+ ion influx and lowers excitability thresholds through

activation of the p38-MAPK pathway, thereby contributing to NP [91]. For

instance, spinal nerve injury in rats induces allodynia, accompanied by elevated

levels of TNF- and phosphorylated p38. Inhibitors of TNF- or

p38 can alleviate this allodynia. TNF- binds to its receptor and

activates the NF-B signaling pathway, whereas activation of the

N-methy1-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor is associated with the expression of

NF-B [109]. NMDA receptors are involved in peripheral, spinal cord, and

cerebral pain pathways by potentiating excitatory postsynaptic currents [110].

Thus, NMDA may be a potential therapeutic target for PHN.

TNF- is an important mediator in the pathogenesis of NP in the CNS and

the peripheral nervous system. It acts in concert with various mediators,

including ILs, nerve growth factors, chemokines, and IFNs, coordinating pain

signal transmission through the NMDA, ATP, and MAPK signaling pathways.

4.2 IL-1

IL-1, belonging to the IL-1 family, is primarily produced by activated

macrophages and exhibits different biological effects. Zhao et al. [111]

reported increased levels of IL-1 in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with

PHN. In a meta-analysis involving 1373 participants, researchers confirmed that

in patients with HZ, the expression of IL-6 and IL-1 was higher in those

who developed PHN than in those with HZ without PHN [83]. However, Cao et

al. [112] used a protein array to examine 40 common inflammatory factors in the

skin lesion tissues of patients with PHN and found that only IL-1 was

significantly elevated, albeit with low specificity, whereas there was no

difference in expression of the other 39 inflammatory factors, including

IL-1. The contradictory results might stem from differences in detection

sites. The epidermis in skin affected by PHN exhibits increased thickness

compared to normal skin, suggesting possible structural or molecular changes.

Immunohistochemical data have consistently shown reduced nerve ending density in

the epidermis of PHN skin [113, 114, 115, 116, 117]. While various cell types can express IL-1,

barrier cells such as epithelial cells normally express high amounts of IL-1. The

decreased IL-1 expression in PHN may be linked to cellular changes such as the

loss of specific cell types in the affected skin. Moreover, the molecular

pathological alterations observed in the skin affected by PHN could lead to

decreased IL-1 expression. This indicates that the persistent and chronic pain

experienced by PHN patients may not be directly linked to skin inflammation.

Under normal conditions, IL-1 expression is low. After peripheral nerve

injury, IL-1 expression is elevated in glial cells, and certain immune

cells within the spinal cord, leading to diverse effects on the nervous system.

Similar to TNF-, IL-1 signaling participates in pain through

activation of the NF-B and p38-MAPK pathways. In the peripheral DRG,

IL-1 acts on TRPV1

and IL-1R to modulate pain sensitivity [118]. TRPV1, part of the TRP family, is

closely associated with the perception of harmful stimuli and pain generation.

Activation of TRPV1 can regulate Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent Ca2+

channels (VDCCs) [119]. This process results in the release of neuropeptides and

excitatory amino acids from nerve terminals, which ultimately leads to the

perception of pain in the cortex [120]. JAK and PKC inhibitors alleviate

sensitization of TRPV1. TRP inhibitors help prevent the release of injurious

substances, paving the way for the discovery of novel analgesics. Upon binding to

IL-1Rs, IL-1 also promotes prostaglandin synthesis, indirectly

sensitizing pain receptors to induce pain. Biologically active IL-1 is

formed from the precursor IL-1 by cleavage through certain enzymes, with

matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) playing a significant role in this process.

Among these, MMPs affect the release of IL-1. Increased activity of MMP9

and MMP2 due to nerve injury promotes cleavage of the IL-1 precursor,

resulting in the formation of biologically active IL-1. Inhibitors of

MMP9 or MMP2 can reduce the biological activity of IL-1, significantly

alleviating NP behaviors in animals. In addition, at central sites, IL-1

induces nociceptive sensitization [109] by promoting the release of substance P

from -amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl4-isoxazolepropionic acid or NMDA

receptors [121], an ionotropic glutamate receptor mediating excitatory

neurotransmitter transmission that plays a crucial role in the pain pathway.

Activation of the NMDA receptor leads to Ca2+ inward flow, promoting central

sensitization [122]. In conclusion, IL-1 promotes PHN by directly or

indirectly increasing neuronal excitability. Modulation of IL-1, TRPV1

[123], and NMDA receptors may serve as new analgesic options to alleviate NP in

patients with PHN.

Therefore, therapeutic blockade of these proteases holds promise for limiting

the release of biologically active IL-1 and potentially alleviating

neuropathic inflammation to achieve relief from NP.

4.3 IL-6

IL-6 is considered an early marker of injury, playing a regulatory role in both

the immune and nervous systems. It suppresses immune function by inducing

macrophages to release transforming growth factor beta (TGF-),

which modulates the acute phase inflammatory response [69]. Arruda et

al. [124] observed elevated IL-6 mRNA levels in the spinal dorsal and ventral

horns of rats following peripheral nerve injury. Similarly, studies involving

human brain vascular adventitial fibroblasts (HBVAFs) and human peripheral nerve

cells infected with VZV revealed significant increases in IL-6 transcription and

expression levels, which lead to the loss of integrity of vascular and neural

barrier and continued viral replication [125, 126, 127].

Research has shown that patients with HZ who later develop PHN have

significantly higher IL-6 levels than those who do not develop PHN [128]. This

suggests that elevated IL-6 expression is associated with inflammatory responses

leading to nerve damage and promoting the onset and progression of NP.

Downregulation of IL-6 expression can significantly alleviate pain. Saxena

et al. [129] observed that during the treatment of neuralgia in patients

with HZ, IL-6 mRNA expression was significantly decreased following substantial

pain relief. Lin et al. [130] analyzed IL-6 levels in patients with PHN

based on pain severity and found significant differences among different severity

groups, with particularly elevated IL-6 levels in patients with severe pain.

Furthermore, IL-6 levels are correlated with short-term prognosis in patients

with PHN. However, a study by Zak-Prelich et al. [131] reported

conflicting results, possibly due to a smaller sample size and a broader age

range.

IL-6 is associated with peripheral mechanisms of pain onset. Under physiological

conditions, low levels of IL-6 are beneficial for normal development and repair

of the nervous system; however, excessive production of IL-6 can lead to

neurological damage. A study has shown that direct injection of IL-6 into rodent

joints results in sustained sensitization of injury-sensing C fibers [120].

IL-6-mediated inflammatory responses may be linked to pain hypersensitivity.

Following peripheral nerve injury, IL-6 and IL-6R are highly expressed in

neurons. Similar to IL-1 and TNF-, IL-6 enhances Na+ [132] and

Ca2+ [133] currents in peripheral nerve terminals, triggering action potential

firing. This increases membrane excitability and reducs the pain threshold,

leading to peripheral sensitization. IL-6 also induces activation of JAK and PKC,

increasing TRPV1 sensitivity and inducing pain [134, 135].

IL-6 is a neurogenic signaling mediator that transmits injury signals to the CNS

[117]. Microglia activation promotes the PHN. After nerve injury, IL-6 mediates

NP through the JAK2/STAT3 and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF)/STAT3 signaling

pathway [136, 137]. Activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway promotes microglia and

astrocyte activation, leading to cytokine release and amplifying

neuroinflammation. The initiation and progression of inflammatory cascades from

the peripheral regions to CNS are mediated by the CNTF-STAT3-IL-6 signaling axis.

Blocking the CNTF-STAT3-IL-6 pathway can alleviate nerve inflammation in the DRG

and spinal cord, thereby reducing pain following injury [137]. Administering

anti-IL-6 antibodies significantly reduces JAK2/STAT3 signaling and pain behavior

in rats. Overall, these studies suggest that targeting IL-6 could be advantageous

in alleviating inflammatory responses and modulating the impact on nociceptors.

4.4 IL-18

IL-18 is also a cytokine involved in the regulation of the immune response [71].

It has been shown to be associated with chronic pain, such as NP, osteoarthritis

pain, and cancer pain [72, 73, 74]. Khazan et al. [138] confirmed that IL-18

levels are linked to the risk of PHN. At the peripheral site, IL-18 ,which

produced by immune cells, stimulates the transcription of Toll-like receptors and

NF-B, promoting the release of inflammatory mediators and mediated pain

signaling [139, 140]. IL-18 modulates pain by influencing ion channels and

receptors mediating pain in the nervous system [72, 141]. Increased IL-18

expression has been observed in various models of NP resulting from nerve injury.

IL-18 plays a pivotal role in NP regulation through injurious sensory

transmission [141, 142, 143, 144]. In addition, IL-18 is crucial in regulating the activity

of glial cells [145, 146, 147]. Blocking the IL-18 signaling pathway inhibits glial

cell hyperactivity and subsequent activation of Ca2+ dependent signaling pathways

[148]. IL-18-mediated interactions between microglia and astrocytes are pivotal

for NP [72]. Studies [53, 144] have shown that microglia contribute to

inflammation and NP by producing IL-18. Additionally, oligodendrocytes have been

implicated in neuroinflammation via IL-18 production [149]. Immune-mediated

inflammation significantly influences NP development, with IL-18 mediating

microglial and astrocytic interactions that release proinflammatory cytokines,

chemokines, and other signaling molecules [72], thereby amplifying pain signals

and recruiting immune cells to injury sites [150]. Moreover, IL-18 triggers

cytokine production through inflammatory vesicle complexes, further enhancing the

immune response [151]. These findings collectively emphasize the critical role of

IL-18 in the pathogenesis of PHN.

4.5 IL-10

Uçeyler et al. [152] showed that IL-10 gene expression increases

immediately after nerve injury, with a secondary peak observed within 45 days.

Khan et al. [153] found that minimal inflammation of peripheral nerves

following injury had no significant effect on IL-10 levels in sciatic nerve of

rats across four types of sciatic nerve injuries. Partial nerve injury decreased

IL-10 levels in the affected nerves, whereas complete nerve transection increased

IL-10 expression. This implies that IL-10’s involvement in NP etiology may vary

depending on the specific nature of the nerve injury. After nerve injury, IL-10

activates microglia in the CNS to mediate NP [154]. IL-10 stimulates G

protein-coupled receptor 40, along with intracellular signaling pathways such as

STAT3, leading to increased -endorphin expression and secretion

[155]. Sharma et al. [156] identified the expression of IL-10 receptors

in cortical neurons, where they mediate neuroprotection through the activation of

the PI3K/AKT and STAT3 pathways. Additionally, Huang et al. [157]

demonstrated that IL-10 attenuates NP by downregulating Nav1.7 in the DRG of

rats. Following sciatic nerve crush injury in mice [158] , IL-10 secretion by

macrophages is increased, which subsequently lowers the levels of chemokines and

cytokines. Additionally, IL-10 deficiency impairs axonal regeneration and hinders

the recovery of nerve functions. Atkins et al. [159] studied the effects

of IL-10 on nerve regeneration in anesthetized C57 Black-6 mice following left

sciatic nerve sectioning and resealing with four extraneous nerve sutures. The

authors injected IL-10 (125 or 500 ng) at the repair site before and after nerve

sectioning. Their findings revealed that a low dose of IL-10 at the sciatic nerve

repair site facilitated better axonal regeneration, whereas a high dose did not.

This suggests that optimal levels of IL-10 promote nerve regeneration, while

prolonged high levels are detrimental to nerve repair. A study has shown that

the induction of VZV-specific T lymphocytes is accompanied by increased IL-10

expression [152].

Jenkins et al. [160] showed that elevated levels of IL-10 are involved

in the immune response to certain viruses. The intensity of the inflammatory

response triggered by VZV directly influences the production of IL-10, which

increases proportionally to mitigate the inflammation. However, high IL-10 levels

can inhibit T helper1-specific cell-mediated immunity, allowing the virus to

spread more effectively. While IL-10 enhances anti-inflammatory effects, it can

also prolong inflammation, explaining why chronically high IL-10 levels impede

nerve damage repair. In a study seeking predictors of neuralgia duration in HZ

patients [161], a marked elevation in IL-10 levels was observed in the serum of

patients experiencing severe HZ. IL-10 were positively correlated with neuralgia

duration and pain severity, leading to the conclusion that IL-10 levels are an

independent risk factor for PHN. Although most studies suggest that IL-10 has a

positive effect on relieving NP, NP in these studies was short-lived and mostly

inflammatory. PHN is a chronic NP lasting more than 3 months, caused by nerve

injury. Persistent elevation of IL-10 not only prolongs the inflammatory response

but also impedes nerve repair. From this perspective, IL-10 may mediate the

development of PHN. Future studies on the mechanism of IL-10 involvement in PHN

are needed (Table 2, Ref. [72, 80, 90, 91, 92, 95, 102, 110, 119, 120, 132, 133, 141, 152, 162]).

Table 2.

Possible mechanisms of action of cytokines involved in PHN.

| Cytokines |

Mechanisms of action |

Effect |

Refrences |

| TNF- |

Activation of voltage-gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels |

Central sensitization |

[91, 92, 95] |

|

Increased excitatory postsynaptic membrane currents |

Increases neuronal excitability |

[80, 102] |

|

Increase in membrane cation conductance in non-voltage gated mode |

Increases neuronal excitability |

[95] |

|

Promotes the release of inflammatory factors |

Amplifying the inflammatory response |

[90] |

|

NR1 phosphorylation of the NMDA receptor |

Hyperalgesia |

[110] |

|

Increased cyclooxygenase 2 and PGI2 synthase in endothelial cells |

Peripheral sensitization |

[162] |

| IL-1 |

Capsaicin receptor activation regulates Ca2+ inward flow via VDCC |

Release of neuropeptides and excitatory amino acids from nerve endings |

[119, 120] |

| IL-6 |

Increased Na+ and Ca2+ currents in injury receptor terminals |

Peripheral sensitization |

[132, 133] |

| IL-18 |

Regulation of ion channels and receptors |

Peripheral and central sensitization |

[141] |

|

Activation of glial cells |

Promotes inflammation and increases pain sensitivity |

[72] |

| IL-10 |

Suppression of the immune response |

Prolonged inflammatory response |

[152] |

IL, interleukin; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid; PGI2, prostaglandin I2; VDCC,

Voltage-dependent calcium channel; PHN, postherpetic neuralgia.

5. Future Research Perspectives

Cytokines are essential for sustaining NP. PHN, as a typical NP, is closely

associated with inflammatory cytokines. Cytokines are generally secreted by

multiple cells and can act on various target cells. Moreover, a single cytokine

can trigger its target cells to produce additional cytokines, initiating a

cascade of effects. In fact, neuroinflammation, driven by the interplay between

pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, serves as a fundamental

mechanism underlying the onset of PHN. The above-mentioned role of cytokines in

PHN is unquestionable, but there are few studies on the effects of cytokine

antibodies on PHN. Cell and organ culture models, as well as animal studies, have

demonstrated promising outcomes with anti-cytokine medications and pathway

inhibitors for alleviating NP. However, clinical evidence remains sparse

regarding the role of anti-cytokine drugs in NP. Moreover, clinical trials

[163, 164, 165, 166] targeting TNF- antagonists in sciatic neuropathy treatment

have notably failed to eliminate NP. Given the complex interplay in

neuroinflammatory balance, targeting specific cytokines poses a challenge. An

alternative therapeutic approach may involve regulating the cytokine cascade more

comprehensively through growth factors. In a clinical trial using ibudilast to

treat diabetic NP, patients experienced effective pain relief [167] due to the

fact that ibudilast inhibits the activation of glial cells and reduces the

release of cytokines. Valerian theophylline reduces pain by inhibiting microglia

activity [168]. Thus, future research targeting entire systems [169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174] such as

inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, MAPK, and neuroglial cells is expected to

emerge as promising avenues for comprehensive PHN treatment. Due to the strict

human specificity of VZV, how to use VZV strains in rodent models to overcome

this specific infection remains to be determined by researchers, which will also

provide reliable models for PHN treatment research.

Abbreviations

PHN, postherpetic neuralgia; HZ, herpes zoster; VZV, varicella-zoster virus; HSV-1, herpes simplex virus type 1; TNF-, tumor necrosis factor alpha; CCI, chronic constriction injury; ILs, interleukins; IFN-, interferon gamma; TNFR1, TNF receptor 1; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-B, nuclear factor kappa B; cIAP1/2, cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins 1 and 2; IRAK, IL-1 receptor-associated kinase; IL-1R1, IL-1 receptor type I; IL-1RAcP, IL-1 receptor accessory protein; TRAF6, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6; JAK, Janus kinases; STAT, signal transducers and activators of transcription; TIR, toll-IL-1 receptor; AP-1, activator protein-1; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; NMDA, N-menthy1-D-aspartic acid; VGSCs, voltage-gated sodium channels; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1; VDCC, Voltage-dependent calcium channels; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; TGF-, transforming growth factor beta.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.