1 Child Rehabilitation Division, Ningbo Rehabilitation Hospital, 315000 Ningbo, Zhejiang, China

2 School of Biomedical Engineering, Capital Medical University, 100069 Beijing, China

3 State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning, Beijing Normal University, 100875 Beijing, China

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on brain functional networks in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

We constructed brain functional networks using phase-locking value (PLV) and assessed the temporal variability of these networks using fuzzy entropy. Graph theory was applied to analyze network characteristics. Resting-state electroencephalography (EEG) data were used to compare differences in brain functional connectivity, temporal variability, and network properties between children with ASD and typically developing (TD) children. Additionally, we examined the changes in functional connectivity, temporal variability, and network properties in children with ASD after 20 sessions of tDCS intervention.

The study revealed that children with ASD exhibited lower connectivity in the alpha band and higher connectivity in the beta band. In the delta and theta bands, ASD children demonstrated a mixed pattern of both higher and lower connectivity. Furthermore, ASD children exhibited higher temporal variability across all four frequency bands, particularly in the delta and beta bands. After tDCS intervention, the total score of the Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC) significantly decreased. Additionally, functional connectivity in the delta and alpha bands increased, while temporal variability in the delta and beta bands decreased, indicating positive changes in brain network characteristics.

These results suggest that tDCS may be a promising intervention for modulating brain functional networks in children with ASD.

ChiCTR2400092790. Registered 22 November, 2024, https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=249950.

Keywords

- autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

- transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)

- electroencephalogram (EEG)

- phase locking value (PLV)

- brain functional network

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by impairments in social communication and the presence of repetitive behaviors [1]. Research has shown that abnormalities in brain development and connectivity in individuals with ASD can compromise information processing abilities, leading to a variety of behavioral challenges [2, 3]. This chronic condition significantly impacts the quality of life for both patients and their families and places a considerable burden on healthcare systems [4]. At present, there are no effective pharmacological treatment for ASD, highlighting the need for the development of more effective therapeutic interventions.

In recent years, the advancement of non-invasive neuromodulation techniques has made transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) a promising new method for treating ASD [5]. tDCS can modulate neuronal excitability by applying a weak electrical current to the scalp, thereby altering the resting membrane potential of cortical neurons [6, 7]. Existing studies have demonstrated positive effects of tDCS in various neurological disorders, including Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and depression [8, 9, 10]. This has sparked interest in its potential for treating ASD. Amatachaya et al. [11] observed significant improvements in social skills in ASD patients following five sessions of anodal tDCS treatment. Mahmoodifar found that combining motor training with tDCS enhanced balance control in children [12]. Furthermore, applying anodal tDCS to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) resulted in improvements in cognitive and social skills in ASD patients [13].

The brain was a complex network system composed of numerous interconnected regions that were spatially separate yet functionally coupled, enabling the transmission and integration of information to ensure effective responses to stimuli [14, 15]. Previous study has established correlations between brain networks and clinical disorders [16], with evidence suggesting that cognitive function in individuals with ASD is closely linked to functional connectivity within the brain network. Both insufficient and excessive connectivity can impair information processing in these individuals [17]. Furthermore, the brain is a dynamic system, with higher-order cognitive processes typically associated with synchronous activity among different regions [18, 19]. Temporal variability analysis has emerged as a key method for assessing the dynamic changes in inter-regional connectivity over time [20], and it has been shown to be related to specific higher-order cognitive processes and mental disorders [20, 21]. In individuals with ASD, resting-state electroencephalography (EEG) studies have reported widespread reductions in long-term coupling between frontal and posterior regions [22, 23]. However, these studies have not analyzed the differences in global and local information processing capabilities in ASD patients, nor have they explored the deeper characteristics of brain networks. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the functional connectivity and temporal variability of brain networks in children with ASD using high temporal resolution EEG signals. We focused on analyzing the characteristics of these networks to understand the impact of tDCS on brain function. Based on prior research indicating reduced activation in the left DLPFC in ASD patients and its relationship with cognitive function [3], we hypothesized that tDCS could modulate brain activity by enhancing activation in specific brain regions.

To test this hypothesis, we applied anodal stimulation to the left DLPFC and cathodal stimulation to the right orbitofrontal cortex in children with ASD. Resting-state EEG data were collected before and after tDCS to construct and analyze brain functional networks using network theory. We examined the parameters, including functional connectivity, temporal variability, node degree, clustering coefficient (CC), global efficiency (GE), and characteristic path length (CPL), to assess the effects of tDCS on brain network properties. Additionally, we measured behavioral changes using the Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC) before and after the intervention. Furthermore, we compared brain functional networks between children with ASD and typically developing (TD) children, aiming to provide insights into the neural mechanisms of tDCS in ASD and inform future treatment strategies.

In this study, we recruited 48 children diagnosed with ASD, with a mean age of 5.61 years (SD = 1.32), and 48 age-matched TD children, with a mean age of 5.48 years (SD = 1.39). The ASD children were randomly assigned to two groups: (1) the experimental group, consisting of 24 children (mean age = 5.84 years, SD = 1.85), who received 24 sessions of real tDCS; and (2) the control group, also comprising 24 children (mean age = 5.44 years, SD = 2.17), who received 20 sessions of sham tDCS.

The inclusion criteria for children with ASD were: (1) a diagnosis confirmed by a professional child psychiatrist based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [24]; (2) ages between 4 and 6 years; and (3) written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included: (1) a history of neurological disorders, such as epilepsy, brain injury, or neurosurgery; (2) the use of antipsychotic or anticonvulsant medications during or prior to the experimental period; and (3) previous exposure to tDCS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), or neurofeedback prior to participation. Before the experiment, parents or legal guardians were fully briefed on the study procedures and provided written informed consent. They were also informed that the children could withdraw from the study at any time without any negative consequences. Throughout the study, the children with ASD continued their regular behavioral training. This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ningbo Rehabilitation Hospital (Approval No. 2023006).

This study was conducted in three phases:

Phase 1: Baseline Assessment. In the first phase, detailed EEG recordings were taken from all participating children to establish baseline brain activity patterns. Additionally, comprehensive behavioral assessments were carried out using the ABC to evaluate the children’s behavioral baseline.

Phase 2: Treatment Period. During this phase, children in the experimental group received tDCS treatment with 1 mA anodal stimulation applied to the left DLPFC. Each treatment session lasted 20 minutes and was administered five times a week for four weeks, totaling 20 sessions. Children in the control group received sham stimulation to account for placebo effects. Throughout this phase, the children’s comfort and any potential side effects were carefully monitored to ensure both safety and efficacy.

Phase 3: Post-tDCS Assessment. After the treatment period, EEG recordings and ABC assessments were repeated for all children to evaluate changes in brain activity and behavior following the tDCS intervention.

In this study, to ensure the safety and efficacy of tDCS stimulation, we strictly controlled the impedance between the two saline-soaked sponge electrodes during stimulation, keeping it below 20 k

EEG data were collected in a soundproof room while participants remained at rest with their eyes open. An eight-channel EEG acquisition system was used to record five minutes of EEG data from electrodes placed at F3, F4, C3, C4, T3, T4, O1, and O2. During the data recording, the impedance of all channels was maintained below 50 k

The offline data analysis was performed using MATLAB R2016a (Version 9.0.0.341360, MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) and EEGLAB V2022.1 (Swartz Center for Computational Neuroscience, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA). To reduce the impact of external noise and experimental conditions on the EEG signals, a bandpass filter with a range of 0.5 to 40 Hz was applied during preprocessing. Independent Component Analysis (ICA) was then used to decompose the EEG signals and separate different independent components. The automatic algorithms in EEGlab were employed to identify and remove artifacts associated with eye movements, muscle activity, and electromyography (EMG) from the independent components. The average number of Independent Components (ICs) removed due to artifacts was 1.6. After artifact-related components were removed, the EEG signal was reconstructed using the remaining independent components, excluding any component with a data length less than half of the original data length. Finally, manual inspection was conducted to detect and eliminate any remaining artifacts to ensure data quality, and all channels were re-referenced to the average reference.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the global information flow within the complex brain network by examining the transmission of information between various brain regions. To achieve this, we constructed functional brain networks for both children with ASD and TD children across the

We first calculated the phase of the EEG for each channel and then determined the phase-locking value (PLV) for each pair of channels, as described in the literature [25]. This approach allowed us to generate an 8

To build the functional networks, we utilized a 2-second time window with an 80% overlap. This approach facilitated a comprehensive analysis of the dynamic interactions within the brain’s functional architecture across different frequency bands. Specifically, to estimate the instantaneous phases

where

where P.V. denoted the Cauchy principal value. The phases of the analytic signals

Subsequently, the calculation of the PLV was given by:

where j represented the j-th sampling point, and N was the total number of samples for each signal; t denoted the time point and

In this study, we employed fuzzy entropy to quantify the complexity of brain functional networks and to investigate the temporal variability of their connectivity [27]. Specifically, we assumed that each subject had M functional networks, with the connectivity system

where

Given r, the similarity index between

where

The

This can be estimated through statistical data:

Where M was the length of the time series to be analyzed, r was the width of the similarity measure boundary, and q was the length of the comparison window. Previous study has suggested that an appropriate value for q ensures a detailed reconstruction of dynamic processes, while values that were too large may result in information loss [28]. Based on prior research [29], we set q to 2. Furthermore, if r was too small, it may introduce noise, while if it was too large, it may lead to information loss. Therefore, we set r to 0.2 times the standard deviation of the time series [27].

Regarding the temporal variability of functional networks, we utilized preprocessed EEG signals to calculate the PLV with an 80% overlap and a 2-second time window. This approach generated M networks with a resolution of 200 milliseconds. To construct dynamic functional networks, we employed fuzzy entropy as a measure. Given that fuzzy entropy calculations can be easily influenced by false connectivity within the network, we implemented a thresholding strategy to identify and remove the false connectivity. A threshold that was too high may retain problematic connections, while one that was too low may lead to the loss of important connectivity [30]. Drawing from previous studies, we defined the top 20% of network edges with the highest fuzzy entropy as indicative of flexible network organization. This approach has been shown to help accurately classify different groups and predict cognitive performance [31]. Based on these findings, we applied a 20% threshold to eliminate false connectivity in our analysis.

To quantify the potential for functional segregation and integration in the brain and to reflect both global and local features of brain networks [32], four network characteristics were calculated: CC, CPL, GE, and local efficiency (LE) [21].

The clustering coefficient served as an indicator of the degree of interconnectivity among nodes in the brain network, reflecting the local clustering of the network. A higher clustering coefficient indicated greater efficiency in information transfer.

The characteristic path length (CPL) was the average length of the shortest paths between all pairs of nodes in the network, reflecting the efficiency of global information processing in the brain network. A smaller value indicated higher efficiency in information transfer within the network.

GE was a characteristic that reflected the speed of information transfer in the brain network and served as an important metric for assessing the network’s information transmission capacity. It was the inverse of the harmonic mean of the shortest path lengths between all pairs of nodes. A higher global efficiency indicated better information transmission performance within the network.

LE reflected the capacity for local information transfer within the network and the closeness of neighboring nodes. It was defined as the harmonic mean of the shortest path lengths between all pairs of nodes within the same local sub-network.

Here,

In this study, we used the ABC [33] as an assessment tool to monitor behavioral changes before and after the tDCS intervention. The ABC was completed by the parents or guardians of the children and consisted of 57 items designed to comprehensively assess the behavior of children with autism across multiple domains. These items were categorized into five subscales: sensory processing, social relationships, use of body and objects, language and communication skills, and social and adaptive skills.

To investigate the differences in brain functional networks and their characteristics between TD children and children with ASD, we first performed independent sample t-tests for preliminary analysis, followed by False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction to adjust for multiple comparisons. Additionally, we conducted a 2

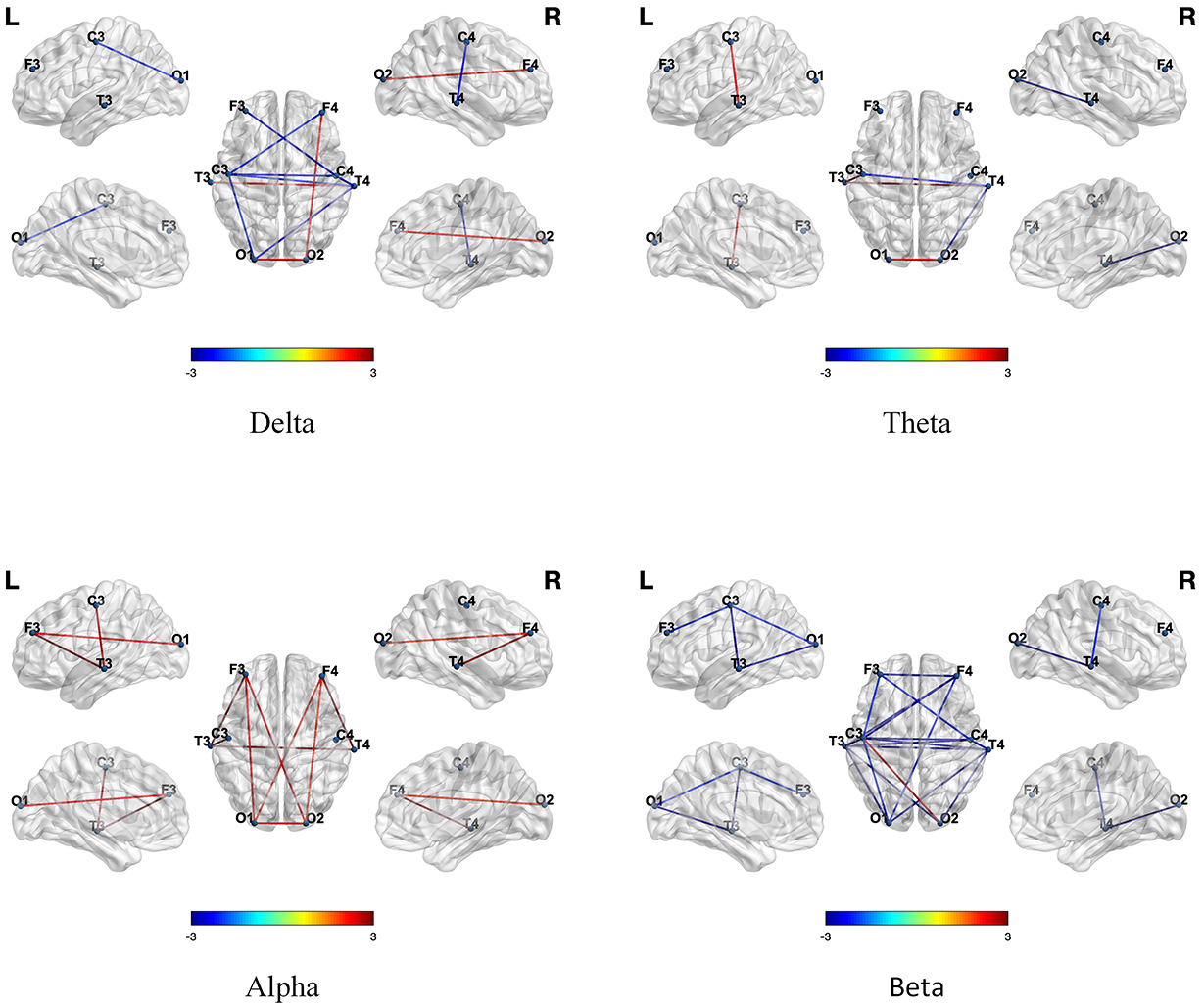

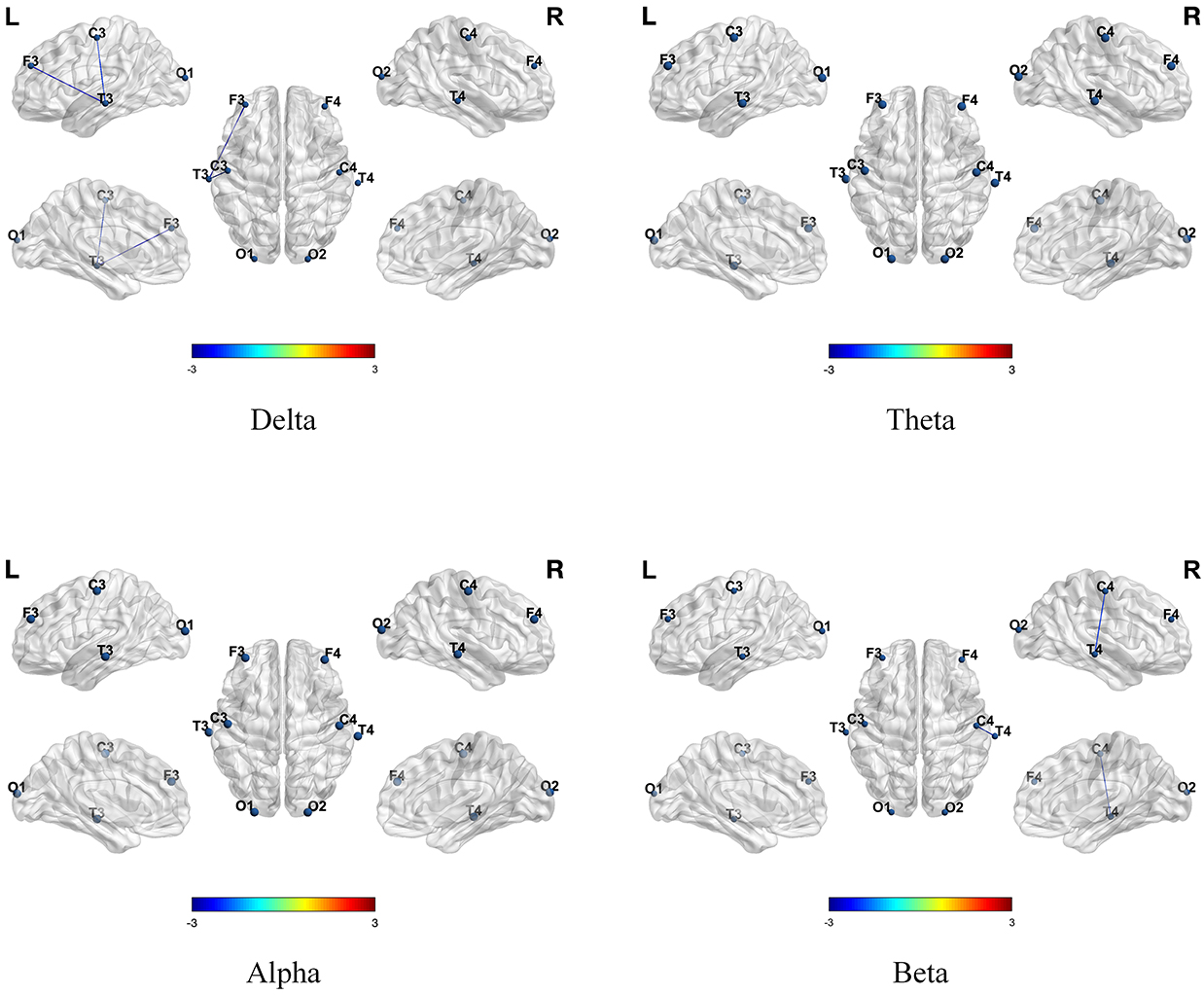

We first constructed the brain networks using the PLV algorithm and examined the differences in functional connectivity between TD children and children with ASD across four different frequency bands. As shown in Fig. 1, there were significant differences in functional connectivity between the two groups, with ASD children exhibiting weaker connectivity in the

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Differences in functional connectivity across four frequency bands between TD and ASD children. A positive value (red line) indicated that functional connectivity was higher in TD children compared to ASD children, while a negative value (blue line) indicated that functional connectivity was lower in TD children compared to ASD children. TD, typically developing; ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

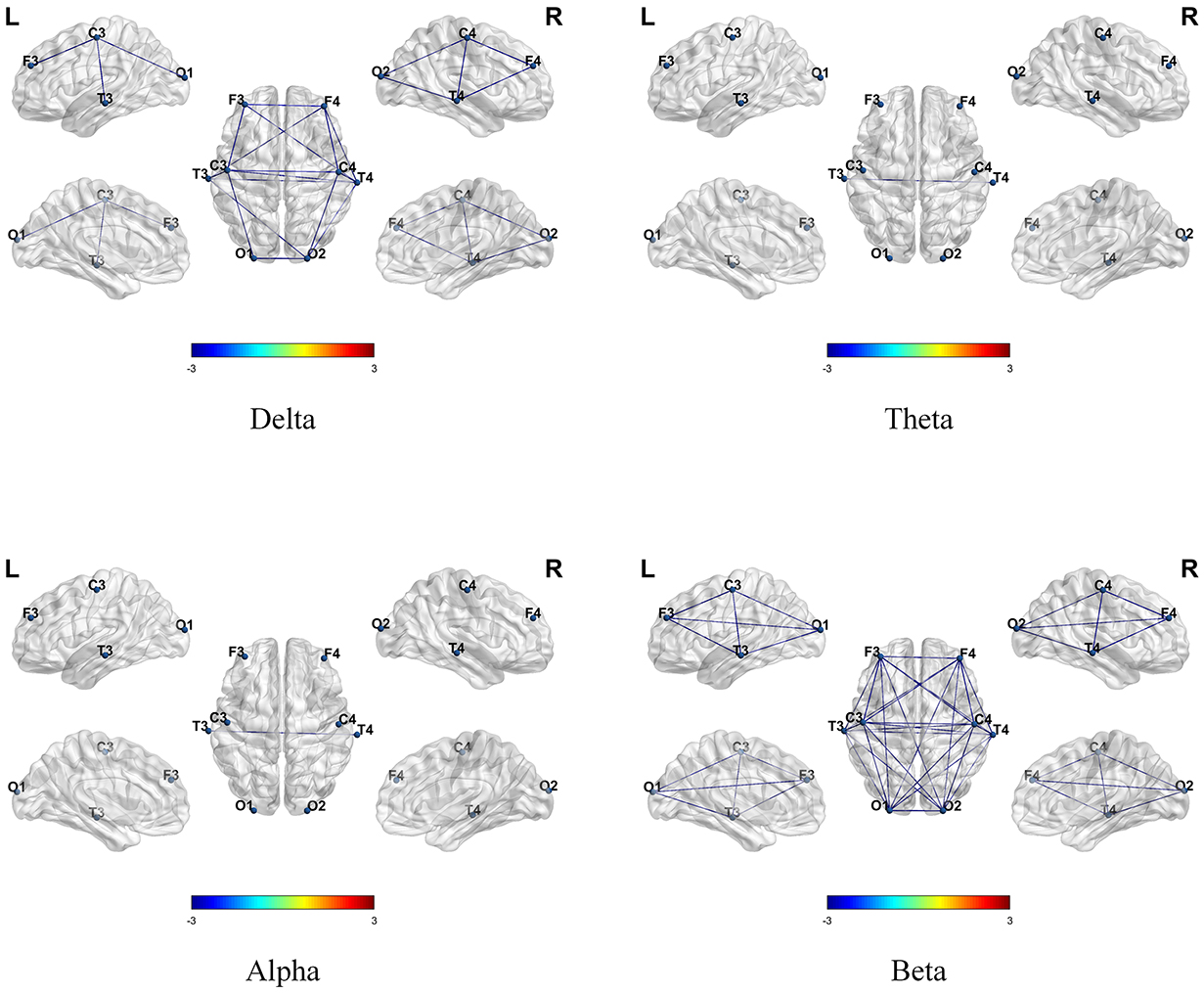

Subsequently, we further investigated the differences in the temporal variability of brain network functional connectivity. As shown in Fig. 2, both groups demonstrated significant differences in temporal variability, with ASD children showing higher temporal variability across all four frequency bands (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Differences in the temporal variability of functional connectivity between TD and ASD children across four frequency bands. A positive value (red line) indicated that temporal variability was higher in TD children compared to ASD children, while a negative value (blue line) indicated that temporal variability was lower in TD children compared to ASD children.

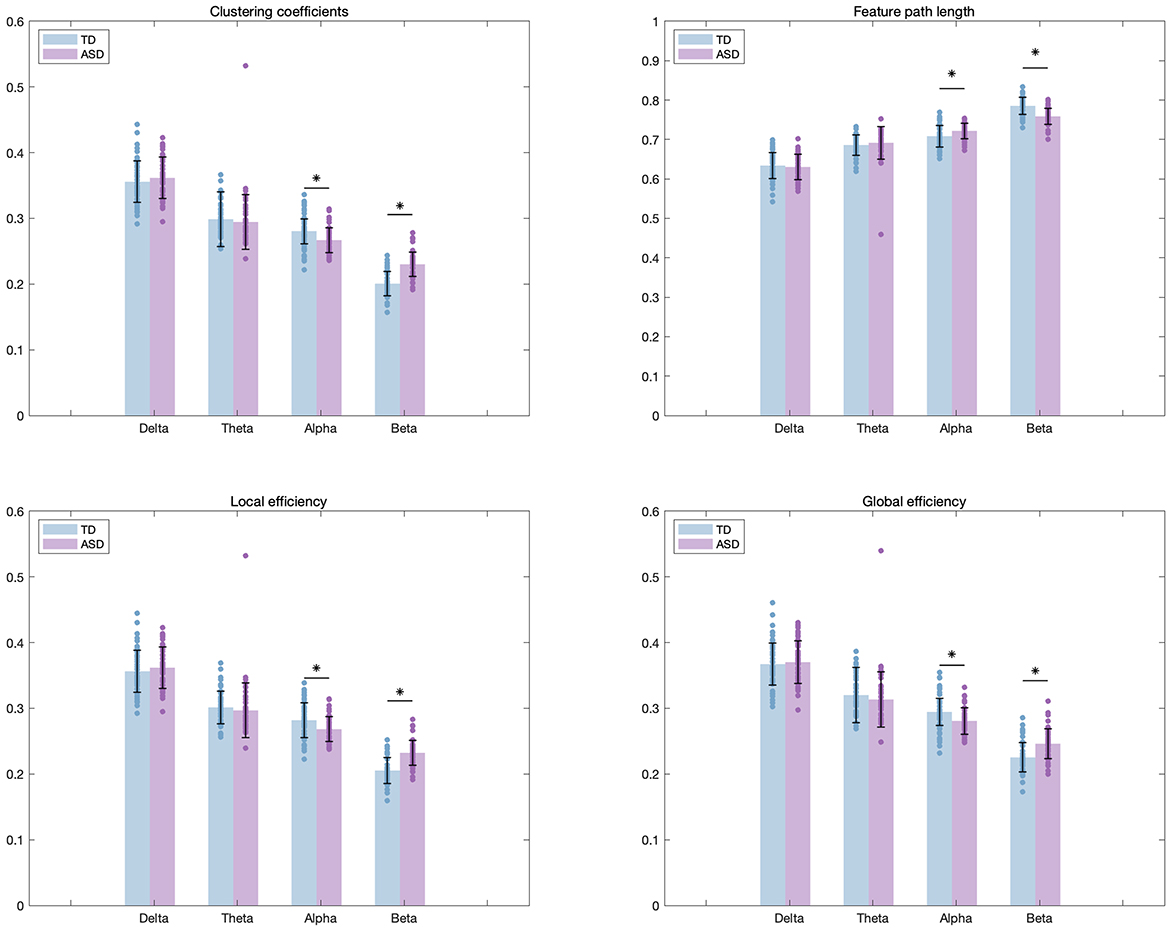

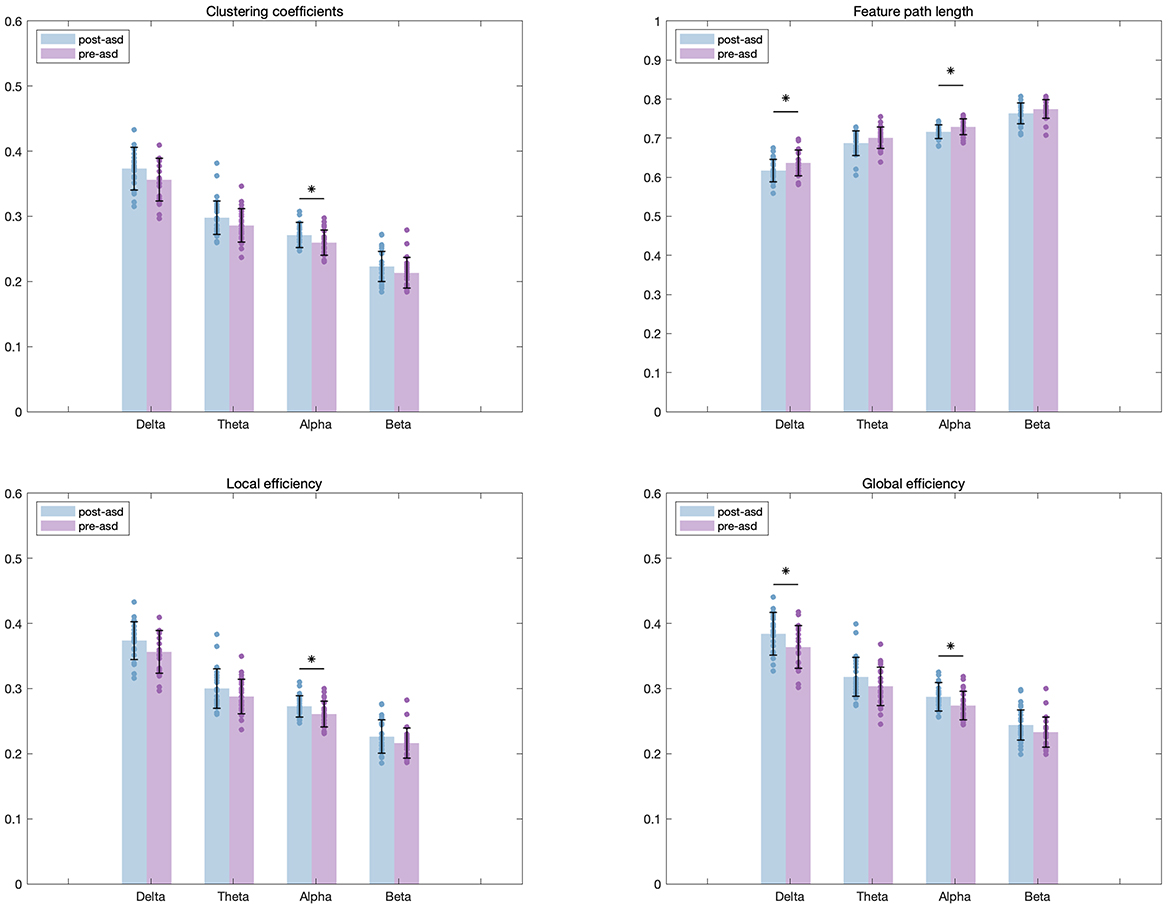

In exploring the network characteristics (see Fig. 3), we found that ASD children had lower CC and LE in the

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Differences in network properties across four frequency bands between TD and ASD children. The comparison included four network characteristics: CC, LE, GE, and CPL in each frequency band. “*” indicated a p-value less than 0.05.

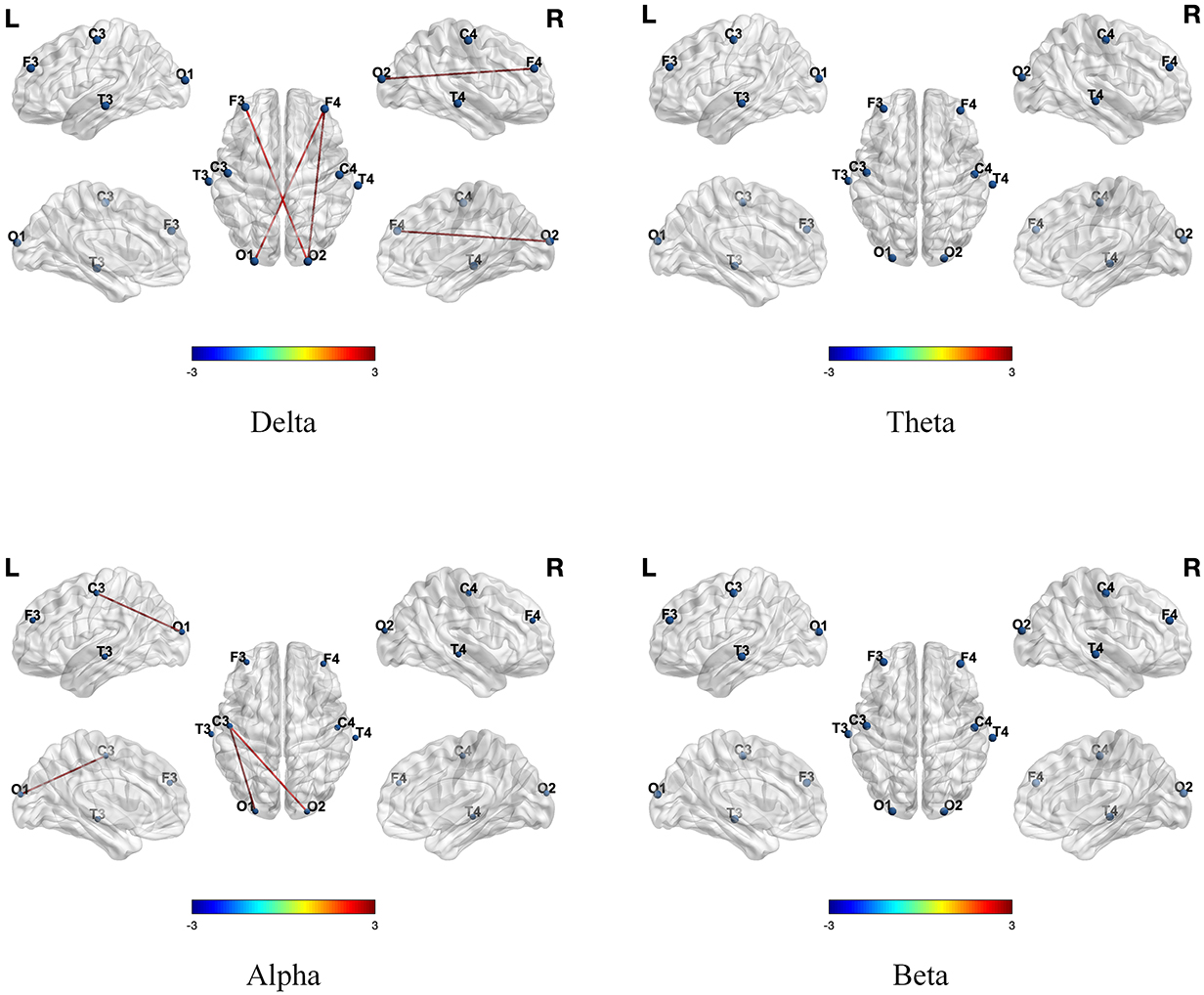

This study aimed to explore the impact of tDCS on brain network functionality in children with ASD. We compared the differences in functional connectivity between the experimental and control groups before and after the tDCS intervention across four different frequency bands. As presented in Table 1, significant interaction effects were observed between the two groups. Further post hoc analyses indicated that, as shown in Fig. 4, the experimental group exhibited enhanced functional connectivity in all four frequency bands following tDCS, while the control group did not show significant differences.

| Frequency band | Channel | Pre-Post*Ture-False (F, p) | |

| Delta | F3-O2 | F = 5.6096 | p* = 0.0280 |

| F4-O1 | F = 4.8879 | p* = 0.0389 | |

| F4-O2 | F = 4.6781 | p* = 0.0428 | |

| C3-T4 | F = 12.2539 | p* = 0.0023 | |

| O1-O2 | F = 4.8993 | p* = 0.0387 | |

| Theta | F3-T4 | F = 5.6705 | p* = 0.0273 |

| Alpha | C3-O1 | F = 17.1586 | p* = 0.0005 |

| C3-O2 | F = 15.5930 | p* = 0.0283 | |

| Beta | C4-O1 | F = 7.4408 | p* = 0.0130 |

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Differences in functional connectivity across four frequency bands before and after tDCS in the experimental group. Positive values indicated that the functional connectivity of children in the experimental group after tDCS was higher than before tDCS, while negative values indicated that the functional connectivity after tDCS was lower than before tDCS. tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

We also investigated the temporal variability of brain network functional connectivity before and after the tDCS intervention. As shown in Table 2, the results indicated that the experimental group showed reduced temporal variability in functional connectivity in the

| Frequency band | Channel | Pre-Post*Ture-False (F, p) | |

| Delta | C3-T4 | F = 5.9278 | p* = 0.0244 |

| O1-O2 | F = 10.8610 | p* = 0.0036 | |

| Beta | C4-O1 | F = 17.9353 | p* = 0.0004 |

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Differences in the temporal variability of functional connectivity across four frequency bands in the experimental group before and after tDCS intervention. Positive values indicated that the temporal variability of functional connectivity in children from the experimental group after tDCS was higher than before tDCS, while negative values indicated that the temporal variability of functional connectivity after tDCS was lower than before tDCS.

Additionally, we conducted a comparative analysis of network characteristics before and after tDCS intervention. Based on the data in Table 3 and Fig. 6, we found that ASD children who received 20 sessions of real tDCS treatment exhibited higher CC and LE in the

| Frequency band | Channel | Pre-Post*Ture-False (F, p) | |

| Delta | CPL | F = 5.3561 | p* = 0.0299 |

| GE | F = 5.8556 | p* = 0.0238 | |

| Alpha | CC | F = 5.9920 | p* = 0.0224 |

| CPL | F = 5.5238 | p* = 0.0277 | |

| GE | F = 5.2633 | p* = 0.0312 | |

| LE | F = 5.8333 | p* = 0.0241 | |

CPL, characteristic path length; GE, global efficiency; CC, clustering coefficient; LE, local efficiency.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Differences in network properties across four frequency bands before and after tDCS for the experimental children. “*” indicated a p-value less than 0.05.

To assess the impact of tDCS intervention on symptom improvement in children with ASD, we conducted repeated measures analysis of variance on ABC scores for both the experimental and control groups before and after tDCS treatment, with the results presented in Table 4. Post hoc analyses were then performed on the scores that showed significant interaction effects, as shown in Table 5. The results revealed that after 20 sessions of real tDCS treatment, the total ABC scores of children in the experimental group showed a significant decrease (p

| ABC scale | Pre-Post*Ture-False (F, p) | |

| Sensory behavior | F = 2.192 | p = 0.147 |

| Social relating | F = 3.205 | p = 0.081 |

| Body and object use | F = 3.143 | p = 0.084 |

| Language and communication | F = 1.821 | p = 0.185 |

| Total score | F = 4.396 | p* = 0.043 |

ABC, Autism Behavior Checklist.

| ABC scale | Pre-tDCS (Mean | Post-tDCS (Mean | p-value | t-value |

| S | 8.81 | 5.76 | ||

| R | 10.62 | 6.52 | ||

| B | 11.90 | 6.38 | ||

| L | 13.05 | 10.86 | ||

| Total score | 55.52 | 37.67 | p* = 0.002 | t = 3.681 |

tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation. “*” indicated a p-value less than 0.05.

This study aimed to investigate the effects of tDCS on brain networks and behaviors in children with ASD. We first compared the brain network differences between ASD children and TD children, and then examined the potential impacts of tDCS on the brain networks and behaviors of children with ASD. The results indicated significant differences in functional connectivity and its temporal variability between ASD and TD children, along with notable differences in network characteristics, aligning with previous studies [20, 34]. The human brain is a highly complex network system, with a close relationship between its network structure and human behavior [35]. Our findings revealed that ASD children exhibited inadequate functional connectivity in the

tDCS is an important non-invasive brain stimulation technique that modulates cortical neuronal activity by applying low-intensity current. This stimulation alters the transmembrane potential of neurons, which in turn affects their excitability and firing rates [37]. In this study, we applied anodal tDCS to children with ASD to explore its effects on brain functional networks and behavioral abilities. After 20 sessions of tDCS intervention, we found significant improvements, including enhanced functional connectivity, reduced temporal variability in functional connectivity, and better behavioral outcomes. The anodal electrode was positioned over the left DLPFC, a key region involved in cognitive functions [38]. The prefrontal cortex, particularly the left DLPFC, was critical for regulating attention and executive functions [39]. Previous functional neuroimaging and brain stimulation study has reported insufficient activation and dysfunction in the prefrontal region in children with ASD [40]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the intervention on the left DLPFC may induce activation in this area, serving as a primary reason for the observed positive effects.

In addition to assessing the potential differences in brain functional networks before and after tDCS intervention, this study also investigated network efficiency. We calculated and compared four key network characteristics: clustering coefficient, global efficiency, local efficiency, and characteristic path length to evaluate potential differences in brain networks. CC reflected the local efficiency or functional segregation of the brain network, GE measured the degree of network integration, LE indicated the network’s ability to transmit local information, and CPL was commonly used to assess functional integration, indicating global information processing capacity. The decrease in CC, GE, and LE, along with the increase in CPL in the

Although this study provided some valuable preliminary findings, there were some limitations. First, the limited number of channels may affect the precision of brain network analysis. In future studies, we plan to use a higher-density EEG acquisition system, depending on the participants’ condition, to obtain more comprehensive dynamic brain network information. Second, considering that the rehabilitation process for children with ASD was typically long-term, the 20-session tDCS treatment protocol used in this study may not fully capture all potential effects on behavioral changes. In future studies, we plan to increase the number of tDCS sessions to 40 or even 60 to assess whether an extended treatment duration leads to greater therapeutic benefits for children with ASD. This will also help determine the optimal duration for tDCS intervention. Additionally, we will explore the effects of tDCS applied to different brain regions to evaluate the therapeutic outcomes of various stimulation sites. Another limitation was that the clinical data collected before and after the tDCS intervention in this study were relatively limited, which restricted our understanding of the full impact of tDCS on children with ASD.

This study demonstrated the potential of tDCS as an effective intervention for modulating brain functional networks and improving behavioral outcomes in children with ASD. By analyzing resting-state EEG data, we found significant differences in brain functional connectivity and temporal variability between children with ASD and TD children, particularly in the alpha and beta frequency bands. ASD children exhibited altered network characteristics, with reduced functional connectivity in the alpha band and increased connectivity in the beta band, as well as higher temporal variability across all frequency bands. Following 20 sessions of tDCS targeting the left DLPFC, children in the experimental group showed enhanced functional connectivity, reduced temporal variability, and improvements in network efficiency, particularly in the alpha and beta bands. These changes were accompanied by a significant reduction in behavioral symptoms, as indicated by the ABC, further supporting the efficacy of tDCS as a potential therapeutic approach for ASD. Our findings suggest that tDCS may serve as a promising non-invasive neuromodulation technique to address brain network dysfunctions in ASD, with the potential to improve both cognitive and behavioral outcomes. However, future studies with higher-density EEG acquisition system, longer treatment durations, and more comprehensive clinical assessments were necessary to fully understand the long-term effects and optimal treatment protocols for tDCS in children with ASD.

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

JK conceptualized the study, designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. WM wrote the manuscript and contributed to the data collection and analysis. JW conducted statistical analysis and drafted parts of the manuscript. XG contributed to the experimental design and revised the manuscript. XL contributed to the data acquisition, supervised the project, funding recipient, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ningbo Rehabilitation Hospital (Approval No. 2023006). Before the experiment, parents or legal guardians were fully briefed on the study procedures and provided written informed consent.

We were grateful to all children and their parents.

This research was funded in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82151304).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.